Hurricanes’ Hidden Toll

Air Date: Week of October 11, 2024

Damage from Hurricane Helene in North Carolina. Overall, initial reports indicate Helene has killed at least 231 people across 6 states, one of the deadliest hurricanes to strike the US mainland in the last 50 years. Ultimate mortality could be 300 times that, the published by Nature research suggests. (Photo: NCDOTcommunications, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

New research published in Nature suggests that initial death tolls only account for a tiny fraction of the mortality that can be linked to hurricanes. On average, each tropical storm or hurricane contributes to 7,000 to 11,000 excess deaths as long as 15 years afterwards. Lead author Rachel Young of UC Berkeley joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain how societal disruptions can bring these long-term effects.

Transcript

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

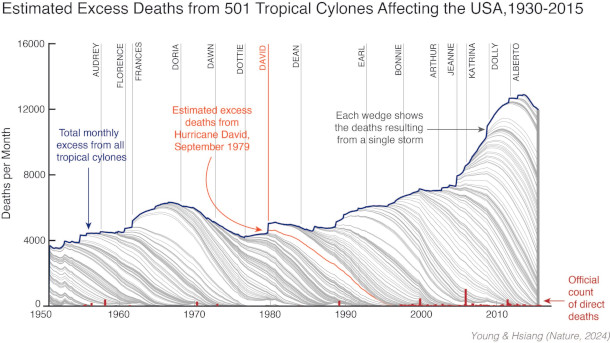

Hurricane Milton spun off deadly tornadoes and cut power to more than 3 million Floridians as it charged across the Florida Peninsula. Tampa dodged the worst-case scenario of massive storm surge, but nearby St. Petersburg experienced over 17 inches of rain. Deaths from Hurricane Milton are still being tallied as we go to air, meanwhile, the official death toll from Hurricane Helene has passed 230. But as devastating as those numbers are, a recent paper published in Nature suggests that these initial death tolls probably account for a fraction of the mortality that can be linked to hurricanes. As many as 3 million excess deaths can be attributed to tropical storms and hurricanes that impacted the US between 1930 and 2015. Lead researcher Rachel Young is an environmental economist and post-doctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and she joined me to explain the findings.

YOUNG: Yeah, in our paper, we studied 500 tropical storms and hurricanes, which we sort of call tropical cyclones that impacted the United States between 1930 and 2015, and we estimate the long run impact those storms have had on mortality at the state level. And we find that there are persistent effects for up to 15 years, there's elevated rates of mortality for up to 15 years, and we find that per storm there's between 7 and 11,000 excess deaths, which is 300 times greater than the official counts of direct deaths. And these results really highlight that hurricanes and tropical storms are a much greater mortality burden than anyone previously thought.

BELTRAN: And why do mortality rates remain so high even after storms hit?

YOUNG: We can't disentangle all of the different ways that hurricanes impact people's lives that could lead to elevated rates of mortality. We do posit a few hypotheses of what could be going on. In the paper, we have five. I'll just talk through a couple, though. The first, and I think is the sort of most prevalent, is that there are just long run economic impacts that hurt people after these storms. You can imagine that your house is partially destroyed or damaged, and folks have to draw down from their retirement accounts or their savings accounts to pay for repairs to those damages, which may, in turn, mean that in the future, if they have a health care incident, or if you know, they need to go to the hospital for any sort of health care related reason, they might not have as much money to pay for the kind of care that they need compared to what kind of money they would have before the storm. Another potential sort of channel is just that there's massive devastation that can occur after these events, huge amounts of damage, and that could drive heightened levels of pollution exposure for individuals. So, a storm comes in, it could destroy a gas station or other kinds of facilities that house a lot of chemicals. We've seen with Helene, some impacts to the sewage systems and massive amounts of raw sewage flowing in the streets. And these kinds of pollution exposures can have long term impacts on people's health outcomes. And then finally, state and local governments have lower budget levels after these storms. You know, they spend a lot of money on repairs for roads and bridges and other kinds of infrastructure, which means that they don't have as much resources to allocate to things, maybe like buying a new wing for a hospital, or other kinds of healthcare related emergency services, which could impact people's healthcare in the long run.

Stacked overlapping excess mortality responses to each storm for all of CONUS (gray lines). Each storm response depicted aggregates state-level responses nationally, accounting for state-level population and adaptation. Official deaths directly resulting from TCs for each month according to NOAA National Hurricane Center and NOAA National Weather Service (red bars). Estimated monthly excess deaths from 501 tropical cyclones (gray lines) and the total (navy blue top line). (Graph: Courtesy of Rachel Marie Young)

BELTRAN: Now, what about age groups? How do death rates differ across age groups?

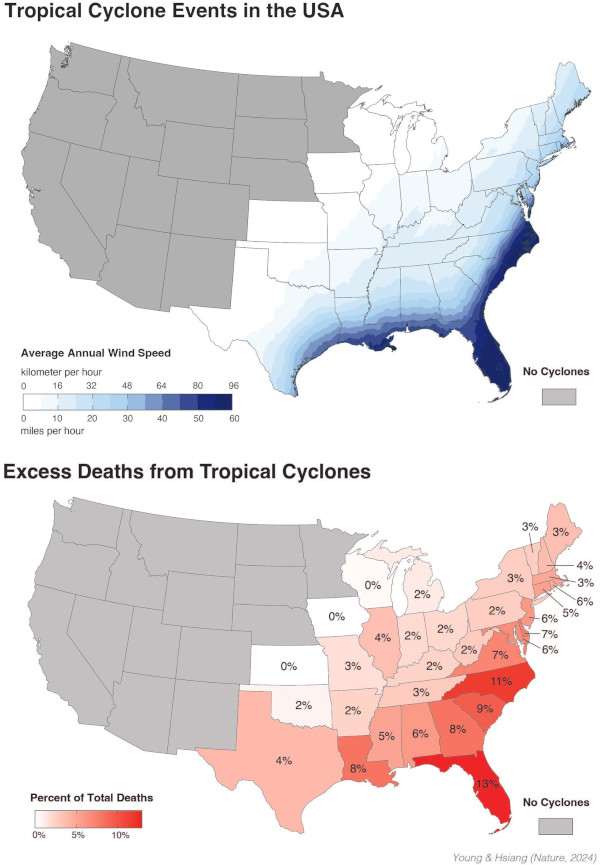

YOUNG: Yeah. So, one thing we thought was really important is to understand if different kinds of folks are at different levels of risk after a storm. And so, we do go, and we look at a couple of different age bins and look at their differential sensitivities after these storms, and we find that infants and the elderly population are particularly vulnerable. After a hurricane, infants have a much greater mortality risk than, say, folks that are aged between 1 and 44. For the infant result, these are infants that are being born many years after the storm, so they did not physically experience the hurricane or tropical storm themselves. The southeast of the United States has elevated rates of mortality compared to the rest of the country, particularly for infants, and we actually find that tropical cyclones are a major driver of those impacts. These are places and states that are getting hit by tropical cyclones many, many times, and that sort of overall climate of being impacted by tropical cyclones is part of the reason why we're seeing higher rates of mortality in the southeastern states.

BELTRAN: So according to this study, infants who weren't even conceived by the time a hurricane hits are still more likely to die because of it?

YOUNG: Yeah, that's exactly what we see. So, 21 months after the storm, these are infants that are dying that were not in utero, they did not physically experience the hurricane or tropical storms themselves. So you can imagine mothers who are giving birth a few years after the storm, maybe they were paying out of their savings account for repairs to their home, replacing their car, other kinds of things that were damaged during the storm, and so they might not have as much access to different kinds of prenatal care, because they just have less money than they would have if they had not had to pay for those repairs. And so, we think this points to maternal health care that needs to be prioritized in order to help reduce some of these infant sensitivities.

Picture taken in Great Carrot Bay, Puerto Rico showing a local man walking through the devastation and what is left of the coast road in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria . (Photo: Joel Rouse, Wikimedia Commons, Fair Use)

BELTRAN: And how did this study account for race?

YOUNG: So, we are able to look at the different risk of mortality amongst the black population compared to white populations, and we find that black populations are much more sensitive after a storm. They have higher rates of mortality compared to their counterparts in white populations. In fact, their mortality risk is about three times greater than white populations. There's a lot of growing literature and a lot of growing discussions around the differences that black populations face with regards to different kinds of environmental events. There's studies that show that they experience heightened rates of air pollution, because of a history of zoning and public housing in the United States. There's a lot of other systemic reasons why black populations have less access to federal resources after disasters, or just other kinds of public services, and we think a lot of that is sort of tied up in why we see elevated rates of mortality risk for those populations.

BELTRAN: Now this study focuses on the continental US but how does it resonate with, for example, Hurricane Maria, where almost 3000 people in Puerto Rico died directly from the hurricane and it caused extensive damage to the island's infrastructure. I mean, some areas of the island are still recovering to this day.

YOUNG: Yeah, Hurricane Maria and then there was a subsequent study that showed that the deaths that were traceable to hurricane Maria were much greater than the official direct death counts, a lot of it driven by power outages that persisted for months after the storm. And that paper actually really was inspiring to us, and helped show that the way that we think about direct deaths and deaths related to hurricanes might not be quite right, and the study that they did really lent credibility to our sort of estimates of the longer-term impact of hurricanes on an individual's mortality. And they do a great job of tracing out some of the ways in which the hurricane impacted infrastructure, which then impacts people's health.

(Top panel): Average annual tropical cyclone maximum wind speed impacting the contiguous US (CONUS), during 1950-2015. (Bottom panel): Estimated average excess mortality traceable to the TC climate by state during 1950–2015. (Graph: Courtesy of Rachel Marie Young)

BELTRAN: You know, Rachel, there are these big hurricanes and tropical storms like Hurricane Katrina, Helene, Maria but what about smaller storms like Hurricane Debbie that hit North Carolina earlier this year?

YOUNG: Yeah, our study, we studied the effects of 500 tropical storms and hurricanes. I expect that most people can't name 500 tropical storms or hurricanes, there are a lot of these storms that are much smaller, that aren't Category 5, that aren't sort of in the news as much. And I think what's important about our findings is that these smaller storms are also impacting communities for a long time. They might not generate as many excess deaths because they have lower wind speeds and lower footprints over the country, but they are also impacting states, and they're driving a lot of those big overall estimates that we find in the study. The 3 million excess deaths is not just from a Katrina or a Sandy it's from the cumulative effects of a lot of small storms and big storms over many, many years.

BELTRAN: Rachel what surprised you most from this study?

YOUNG: The whole study was very surprising to us, like when we initially started this paper, we thought, you know, we knew things about the impact of hurricanes on the economy, and we knew things about how different kinds of environmental events impact long run health, particularly heat waves. We thought that we would see elevated rates of mortality for maybe six months or a year. And when we were doing the analysis, and we saw that the effects were so long, we were really stunned. And we spent many, many years trying to make sure that it wasn't driven by some kind of statistical anomaly. It wasn't an error on our side or an error in the analysis, and we tried every other possible explanation for what could be going on, and ultimately, we found that it was nothing else could explain this elevated mortality rate, except for hurricanes. The whole thing was very, very surprising, and if so, folks are sort of stunned by the magnitude of the effects and the long run impact of these events on human health and mortality, you know, we were there too. We were also very surprised.

Rachel Marie Young is an environmental economist and post-doctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley. (Photo: Courtesy of Rachel Marie Young)

BELTRAN: Now, Hurricane Helene caused severe damage across southeastern states, and hurricane Milton just hit Florida. What can government agencies and government officials learn from this study in order to provide the support communities need for recovery?

YOUNG: State and local and federal governments, and especially first responders are doing really heroic work to help people after these events, to rescue folks, to help get them back on their feet and we don't want their efforts to be in vain. Our study really highlights that communities are being impacted far beyond the immediate aftermath of the storm, that these effects can impact them for many, many years and can lead to impacts on their health. And the individuals that are being impacted by these storms 5, 10, years later, likely themselves, cannot connect their elevated mortality risk in the future back to the original storm. And so, we think that our study really highlights that we can't forget about these communities, and that we need to help them get back on their feet as quickly as possible. We need them to get their insurance payouts in a timely manner and get access to the resources from the federal and state and local governments as fast as they can. And that we can't just forget that this happened, that these folks are going to be impacted for a long time. We need to give them support and resources for longer than we previously thought, and hopefully that will ensure that we see lower mortality rates after hurricanes in the future.

BELTRAN: Rachel Young is an environmental economist and postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley. Thanks for joining us.

YOUNG: Thank you for having me.

Links

Nature | “Mortality Caused by Tropical Cyclones in the United States”

Scientific American | “Hurricanes Kill People for Years after the Initial Disaster”

The Guardian | “Major Storms Contribute to Thousands of Deaths Up to 15 Years Later, Study Finds”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth