Loading the Hurricane Dice

Air Date: Week of October 11, 2024

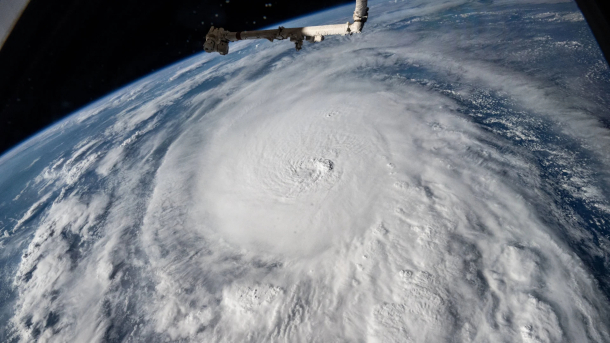

Hurricane Milton as seen from the International Space Station on October 8th. (Photo: Satellite photo, NASA, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Unusually warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico helped fuel the rapid intensification of Hurricanes Helene and Milton. Meteorologist Sean Sublette explains to Host Jenni Doering that as humans continue to pump climate-warming greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, we are loading the dice for stronger storms.

Transcript

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

Hurricanes Milton and Helene underwent rapid intensification thanks in part to very warm waters in the Gulf of Mexico. During each storm temps were in the mid to high 80s Fahrenheit, well above the 79 degrees required to feed a hurricane. Warmer waters in the Gulf means there’s more energy to power a storm. And an analysis published by the World Weather Attribution network of scientists pinpointed climate disruption as a key driver of the warm waters that made Helene so catastrophic with intense rainfall and wind. Sean Sublette is a meteorologist who writes for our media partner, Inside Climate News. And he joins me now from Richmond, Virginia to talk about the conditions that led to this one-two punch of storms. Welcome to Living on Earth, Sean.

SUBLETTE: Thank you very much for having me. I appreciate the invitation.

DOERING: So, how unusual is a situation like this for this time of year, two massive hurricanes nearly back-to-back at this point in the fall season?

SUBLETTE: It's unusual, but it's not without precedent. The core of the hurricane season is from mid-August to mid-October, and we're just starting to get toward mid-October now. If we're having this conversation around Halloween, it's probably a little bit different. But in the Gulf of Mexico, the water temperatures are typically in the 80s this time of year, even well before the climate started to warm things. So, to have hurricanes in the Gulf of Mexico is not unusual in and of itself. One of the things I think that most meteorologists kind of gasped at wasn't the fact that we had two of them, but we had two that underwent rapid intensification. And that's something that sounds colloquial, but it has a very strict definition, meaning that the sustained wind speeds, the maximum sustained wind speeds, have to increase by 35 miles per hour in 24 hours. And those thresholds were easily met for both Helene and Milton.

DOERING: Yeah, I saw that hurricane Milton did indeed rapidly intensify. Do you have those numbers?

SUBLETTE: Yeah, from about lunchtime here on the sixth of October to the same time on the seventh, it increased from 80 miles per hour to 175 miles per hour. The numbers can kind of wash over you after a while. They're so, so immense. But yeah, 95, 95.

Post-Helene destruction in Asheville, North Carolina. (Photo: Bill McMannis, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DOERING: So, tell me a little bit more about this intensity of hurricane Milton. You know, as I understand it, the category of hurricane has a lot to do with its wind speed, but this doesn't always directly link to how much of an impact a storm can have.

SUBLETTE: Yeah, that's one of the things that meteorologists kind of poke back and forth with each other about. There's the classical Saffir–Simpson scale, one to five, five being the strongest of the storms. But you also have to think, well, when it comes ashore, what's at the shore for it to impact? Right? What is the shape of the coastline? How much property is built there, so the impacts are always a little bit different. One of the things that we really try to caution folks about is the storm surge. You know, that wall of water that comes on shore as the center of the hurricane approaches is not very well correlated to the category. I mean, if we think back to 2012 and Sandy, that was a category one storm that was losing its tropical characteristics. I mean, that's meteorological minutiae, as Jim Cantore said on the air the other day. But it was a large storm in scope and size, and when you drag that much water into a coastline, even if it's not 150 mile an hour winds, you're still pushing a phenomenal amount of water onto a coastline. The other thing about the center, and we caution people that don't, don't focus too much on the center, but the center's still important, like we saw with Milton making landfall, the center came in down near Sarasota. So, for a while, the wind in Tampa Bay was offshore, meaning going from the land to the ocean. And for a stretch, there was actually a big drop in water in Tampa Bay. So, the eye and the center, they're all very important for that storm surge flooding. The strongest winds are always around the eye, called the eye wall. But well out ahead of that, there's a lot of big impacts, heavy rain, we saw the tornado outbreak in South Florida well before the center made landfall. In fact, there was a little debate amongst us about, should we just stop saying landfall, since the impacts are six and 12 hours before the center makes landfall. Is that just a passe definition from yesteryear that we should stop using?

????️????BREAKING: Two large tornadoes from Hurricane Milton crossed Interstate 75 in the Florida Everglades around 10 a.m. EDT, moving north between the towns of Miles City and Andytown.

— AccuWeather (@accuweather) October 9, 2024

The tornado shown here was east of the first tornado and closer to Andytown. pic.twitter.com/M65dpsvgWV

DOERING: Well, tell me more about these tornadoes. Why was Hurricane Milton able to spawn multiple tornadoes, some of them deadly, as it moved across the Florida peninsula?

SUBLETTE: It is common in the outer bands of a hurricane as it's making landfall to produce tornadoes. That, in and of itself, is not uncommon. I would argue that a lot of us in the meteorological community were surprised at how many formed. That's gonna take a little more analysis as to precisely why. Just off the top of my head, we were seeing some colder air, drier air, pushing down into the Gulf off of the continent, and that was beginning to force the storm to transition, so it wasn't a purely tropical storm. And I suspect when we go back and look at the analysis, that transition will have played a role into creating an environment conducive for tornadoes in South Florida.

DOERING: We've seen something like 1.3 degrees Celsius so far in terms of average warming since the Industrial Revolution. How does the power of these storms connect back to that warming?

Floridians evacuate the Gulf Coast on October 7th, with the eastbound I-4 highway’s left shoulder opened for emergency use. (Photo: Andrew Heneen, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

SUBLETTE: Yeah, so 1.3C, which is roughly two degrees Fahrenheit, it's basically more energy into the system. Most of that energy from planetary warming is actually going into the oceans. I think that's also lost a lot. About 90% of it is actually going into the oceans, raising ocean temperatures. And it takes a lot more energy to raise the temperature of water than it does to raise the temperature of air. So, it's a phenomenal amount of energy that's going into the oceans, and you get a tropical cyclone, hurricane, over warmer water, two to three degrees warmer than it had been 60 or 70 years ago at this time. You are setting yourself for more rapid intensification and stronger storms. Most of the studies have indicated that the percentage of storms that are stronger, these Cat. threes, fours and five as a percentage of total storms, is going up. The data does not suggest that there's suddenly going to be 30 storms every year, the number of storms may be about the same, but in terms of the percentage of total storms that are more intense, that is expected to go up, and we're beginning to see that data emerge, or that signal emerge from the noise.

DOERING: Which means, of course, more need for people to prepare and heed the warnings. Now, these massive hurricanes pose a huge risk to those in their path. How well do you think that that's being communicated to local people, especially in this era of climate disinformation?

SUBLETTE: I think, having followed this for 20 years, now that it's getting better. We have issues, I think, right now, just in the communications infrastructure globally, but I think that people are starting to understand, the general populace is starting to understand what's going on. The last one to two years in particular, the oceans have been warmer than they've ever been on record, and it was like a quantum jump. When a lot of the climate science community looks at this go, what has suddenly happened? We're still trying to understand why there's this kind of quantum jump about 18 or 24 months ago in ocean temperatures. But we do know, as atmospheric scientists, things don't go up smoothly. They always kind of go up a little bit in fits and starts. They'll go up suddenly, then pause, maybe down a tiny bit, then go back up suddenly, and then pause and down a little. It's kind of a step, right? It's not smooth and linear. There's little steps, fits and starts.

Sean Sublette is a meteorologist with Sublette Weather and Consulting. (Photo: Courtesy of Sean Sublette)

And I think that's kind of what, what has happened over the last one to two years, and we're in a situation that, you know, we're not going back to the climate that your grandparents had, depending on how old you are, in the 50s and 60s, 1950s and 60s, that climate is kind of gone. I try to tell people about it this way. If you have a classical set of six-sided dice, one through six on each cube, and you just roll it, you get numbers between two and 12. Most of the time it's six, seven and eight. If you were to take that same pair of dice, remove the one on each face and put a seven there instead, and then start rolling them. Now, all your rolls are between four and 14, you still get a lot of six and sevens and eights, but now you get a 13 and a 14. What's that about? And you never roll a two or a three again, because those numbers are gone. So, the whole system is kind of shifted in that direction. You know, 80 to 90% of the time you might not notice that much of a difference, but when that outward 10% happens, it happens in a big, bad way.

DOERING: Sean Sublette is a meteorologist with Sublette Weather and Consulting. Thanks so much for joining us today.

SUBLETTE: Thank you so much for the invitation. I appreciate it.

Links

InsideClimateNews | “How Climate Change Intensified Helene and the Appalachian Floods”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth