The Greening of Antarctica

Air Date: Week of October 25, 2024

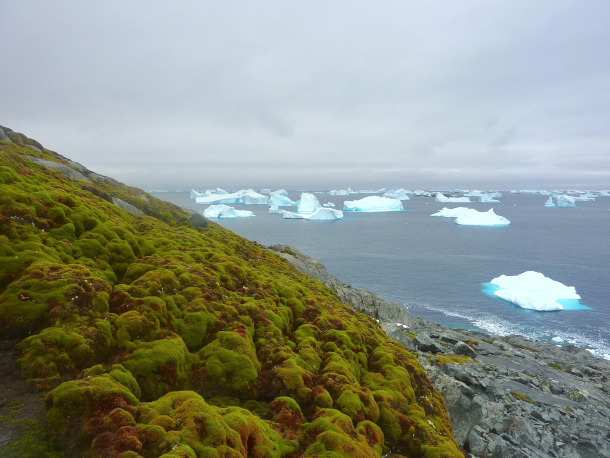

Although you may think of Antarctica as void of green, its peninsula is actually a habitat for moss. (Photo: Matthew Amesbury)

In addition to the retreat and collapse of huge ice shelves, climate change is associated with rapid greening in Antarctica as plants thrive in warmer temperatures. A recent study found that plants have increased more than tenfold on the Antarctic Peninsula in the last few decades. Co-lead author Dr. Olly Bartlett joins Host Jenni Doering to describe the potential ecological consequences of a more verdant Antarctica.

Transcript

DOERING: The impact of climate change in Antarctica can be dramatic, with huge ice shelves breaking up and glaciers collapsing into the sea. But ice isn’t the only thing that’s changing about this frozen world. Earlier this month, a study published in the journal Nature Geoscience revealed that parts of the icy white continent are rapidly greening as plants thrive, potentially because of the significant warming that’s happening at the poles. The researchers analyzed satellite images of the Antarctic Peninsula, that little tentacle reaching towards the tip of South America. Here to discuss the study findings is the co-lead author, Dr. Olly Bartlett, a senior lecturer in remote sensing and geography at the University of Hertfordshire in the UK. Welcome to Living on Earth!

BARTLETT: Thank you very much for having me.

DOERING: So what did you find in this study?

BARTLETT: So the main finding of our study is that vegetation cover on the Antarctic Peninsula has increased over 10 times since 1986, and recently, so from 2016 to 2021, that rate has increased compared to the background rate. So recently, this greening has accelerated. And in terms of football pitches — sorry, I have to lean into my Britishness —

DOERING: Soccer fields.

A new study indicates that the amount of vegetation on the Antarctic Peninsula has increased 10x in the past 40 years. (Photo: Matthew Amesbury)

BARTLETT: Soccer fields. There you go. Yep. So 100 said soccer fields in 1986 so 1515 soccer fields in 2021, and the rates, to throw in a completely different comparison an area. So the rates in the most recent part of the study is well, 54 football pitches a year, if we keep up with that, or one Vatican City.

DOERING: Oh, one Vatican City every single year?

BARTLETT: One Vatican City a year. Yeah.

DOERING: So what do you think is going on there?

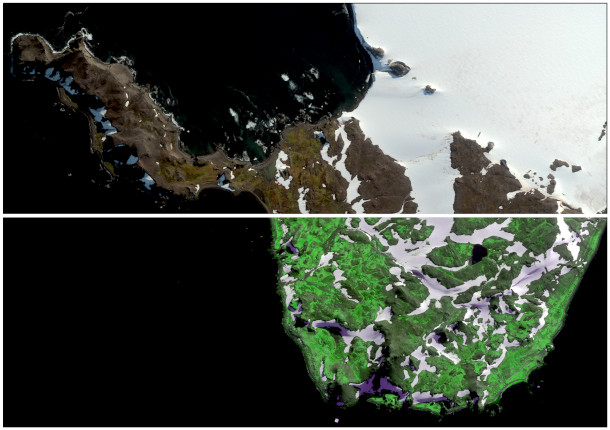

BARTLETT: When we were doing a study, there were multiple times where we didn't believe the numbers, multiple times where we were looking and thinking, nope, this can't be right. Run it again. Run it again, run it again. And so we are confident that these numbers, what we're seeing, is real, and what's happening is we see the mostly moss dominated ecosystems of the peninsula are expanding laterally, so out horizontally. Part of it is also moss that has been there previously but has now grown in health to the extent where it has become so verdant, so green, that it is now identifiable from space when it may not have been in previous years. So, two parts of the signal, one part is this lateral expanse of vegetation, another part vegetation that was there before, but maybe not as green, not as healthy, has increased in its health, in its verdancy, over the study period, and now we're seeing this from space.

DOERING: I have to say that I didn't even realize that Antarctica had green plants on it. We see pictures of penguins, and they're standing there huddled against the freezing Antarctic winters, just surrounded by ice. So tell me more about this amazing ecosystem that exists in Antarctica of moss and other plants.

Dr. Bartlett’s study analyzed red, green, and near infrared bands of light captured by satellites. Plants reflect different amounts of these types of light. In the top half of the photo, you can see what the arial shots look like to the human eye. The bottom half shows the near infrared bands of light usually invisible to us. (Photo: Worldview-2/DigitalGlobe/TheAuthors)

BARTLETT: A lot of the ecosystems we've been measuring are moss, there are lichens, there are liverworts. Now these sorts of plants, they can colonize bare rock surfaces. So when ice moves out of an area, and the conditions are suitable, mosses, lichens. These plants can grow on bare rock. They're colonizer plants. They're the pioneers, if you like, of an ecosystem. There are only two vascular plants, so what we'd think of as a standard flowering plant, if you like, currently across the Antarctic Peninsula, but as more people go to visit the peninsula, that includes scientists like us on the study, but also tourists, there's more chance of bringing seeds and spores from outside and getting them into the ecosystem.

DOERING: Yeah, so that sounds like a real risk for the few native plants that are there.

BARTLETT: Yeah, for sure, and that's one of the main things we're highlighting with our study, is that as this vegetation, as these colonizer plants, these pioneers, as they're growing and getting more comfortable, they're creating the conditions for higher plants and other species to have an easier time of living in one of the harshest places on the planet. So there's real biodiversity implications with this greening rate that we're seeing with this expansion of vegetation across the peninsula.

DOERING: What could we do to prevent the spread of invasive species in Antarctica?

BARTLETT: Yeah, great question. So in terms of the potential for non native species, which can potentially be invasive if they're able to out compete local species. Well, to some extent, Antarctic Peninsula and Antarctica is very windy, nature is going to find a way to get new seeds, new spores, into the continent, into the peninsula, as there are migrating birds as well, that travel from very long distances, from all across the world, down to Antarctica, they're always going to have the potential to bring stuff with them, but in terms of people that are going down there, so scientists and tourists who go to visit on cruises and etc, having really important biosecurity measures, For example, if you go to Australia or New Zealand, they have really tight biosecurity measures in customs, making sure that the kind of kit that you bring that you're going to wear in outdoorsy settings, so like hiking boots, tents, maybe fishing gear that has to be clean. And if you're going down to work in Antarctica, boots, gear, all the stuff that you're going to be wearing that you've bought with you have to be cleaned thoroughly before you're taking them out onto this expanse of lands that may or never have seen the kind of seeds and certain things that you may bring with you.

Dr. Olly Bartlett is a Senior Lecturer in Remote Sensing and Geography at University of Hertfordshire. (Photo: Olly Bartlett)

DOERING: So what exactly is happening there that's allowing this vegetation, these mosses and lichens and liverworts, to spread?

BARTLETT: So Antarctica, much like the Arctic, is at the front line of climate change. As the planet warms, it's well known that the polar regions are warming much more quickly. Now our study, it's really important to say we've seen what we've seen. That's what I do as a remote sensing scientist. I make some observations, I make some measurements, and I report them. W hat we haven't done is attributed any cause to this. Now you can think of some obvious things that are likely to cause this, like increasing temperatures. Most things on this planet do like it a bit warmer than the general conditions that you would get in the poles. Also, moisture availability. So with the reduction in sea ice cover, you're able to free up moisture from the ocean that's sort of locked in by the sea ice underneath it to the atmosphere, where it can move into or onto land and nourish plants that way. So there's two possible causes, both related to a changing climate, then also, with glaciers receding, as is happening across the world, they expose new land which these colonizer plants are able to move into and occupy.

DOERING: Are there any potential impacts on the rate of glacial melting because of these plants growing and spreading there?

BARTLETT: This is often a question that comes up when we see land system change in front of glaciers or in front of ice. When I say land system change, I'm talking about the retention of heat in an area near a glacier. And when we change the color of an area, we change how much heat it directly reflects back that comes in from the sun. So if we were to darken an area, replace snow with vegetation, for example, then we would expect to retain more heat. However, at the scale of our study and where it is and the Antarctic Peninsula is still very much mostly ice and rock, this change in vegetation is very unlikely to retain heat to the extent that it would influence local ice retreat. Might retain heat to the extent where it makes it easier for the ecosystem to develop. That's possible. But in terms of glacial retreat, what's more important in terms of increasing ice melt, is that change from sea ice to ocean on a bigger scale, retaining heat locally to increase the amount of energy available to melt ice, but also on the glaciers themselves, when the surface of the ice gets darker as it melts.

Dr. Bartlett was co-lead author on the study with Dr. Tom Roland. Here they are together in Peru. (Photo: Ellie Fox)

DOERING: Can you project a little bit into the future for us? I know it might be hard to do from this one study, but if this change, this kind of trend line continues, what do you think Antarctica might look like in 50 years or so?

BARTLETT: So we're not expecting Antarctica to be covered in trees or anything like that in 50 years, and to be honest, probably not even shrubs. But what we are potentially going to see is the connectivity between the different bio geographic regions across Antarctica. So not just the peninsula, increasing. So Antarctica is made up of different bio geographical regions which have their own unique biodiversity, their own unique ecosystems. Now if those ecosystems expand and sort of get closer to each other, and it's not so hard for material to move between them. More interconnected, then we could likely see an erosion of biodiversity between these unique biogeographic regions. We would expect to see, as ice goes back, more land becomes available, and we have this increasing greening trend that land to become greener as the ice retreats.

DOERING: What do you hope people take away from your research?

BARTLETT: To some extent, I do hope it causes some kind of surprise or shock to show that even this isolated, remote, last wilderness, really symbolic place on our planet. Okay, the Antarctic has captivated us ever since we've known of its existence, and now it's fundamentally changing across many parts of the system that people see another one and think, okay, if you didn't need waking up before, maybe it's a waking up now. Of we need some real, meaningful change on climate, and those who have the power and the authority to do so are able to start acting to ultimately cutting out greenhouse gas emissions.

DOERING: Dr. Olly Bartlett is a senior lecturer in remote sensing and geography at the University of Hertfordshire in the UK. Thank you so much.

BARTLETT: Thank you so much for having me. It's been a pleasure to talk with you.

Links

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth