Jimmy Carter's Green Legacy

Air Date: Week of January 10, 2025

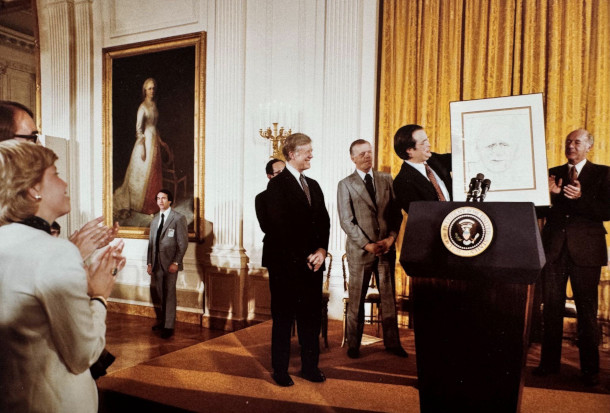

Gus Speth (left) served as a member and then Chairman of the Council on Environmental Quality during President Jimmy Carter’s (right) term from 1977-1981. (Photo: The White House, courtesy of Gus Speth)

The Carter Presidency left a legacy of environmental action, ranging from major habitat protection to trying to address the then largely unrecognized threat of fossil fuels to climate stability. Gus Speth chaired the White House Council on Environmental Quality under Jimmy Carter and sat down with Host Steve Curwood to recall pivotal moments and ponder what might have been if the solar-panel-loving President had won a second term.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

When Jimmy Carter passed away at the age of 100, he left behind a legacy of service and human rights advocacy in his post-presidential years. But his time in the White House also left a legacy of environmental action, ranging from major habitat protection to trying to address the then largely unrecognized threat of fossil fuels to climate stability. Through all of the Carter years, Gus Speth served on the White House Council on Environmental Quality, and he joins us from South Carolina to recall Jimmy Carter and those days. Gus, welcome back to Living on Earth!

SPETH: It's so good to hear you again, Steve, and to know that this great program continues on, strong as ever.

CURWOOD: Thank you. So Gus, you had the opportunity to work directly with the late president, Jimmy Carter, who just passed away at 100 years old. Talk to me about what it was like to be a member and then Chair of the Council on Environmental Quality in that White House.

SPETH: Serving him in the White House, as I did for four years, was such a privilege, because I had this deeper admiration for him as a person, as a man of great integrity and foresight and intelligence then, a man of science. I appreciated those things. And so I started out as a member of the Council on Environmental Quality, and our job for those four years was to help the President develop and implement an environmental program. And it took us in some very interesting directions, because it turned out to be a four years in which energy issues really pushed to the forefront in America. They've stayed there ever since. But we really began and we also became aware of the climate issue during that period.

CURWOOD: Shortly after Jimmy Carter came into office, his science advisor, Frank Press, wrote a memo about climate change. Talk to us about that memo, and what you thought of it and what happened as a result of it.

Gus Speth presents a gift to President Carter in honor of his work on Alaska Lands. (Photo: The White House, courtesy of Gus Speth)

SPETH: Well, I think this was the first time a senior official in the administration wrote directly to the President on the climate issue, to President Carter, and it was pointed, a memo about this need that to begin to incorporate the climate issue into energy policy, and at that time, the country really didn't have an energy policy to put climate into. So Carter didn't take it up right away as a separate issue, but began what turned out to be four intensive years of developing an energy policy which featured, importantly, major programs in energy efficiency and conservation and also in renewable energy, the first programs of that type. Later, our Council on Environmental Quality began to issue its own public reports on the seriousness of the climate problem. And in 1980 he gave a speech in which he, he said very plainly that the climate issue was going to be a preeminent environmental concern, and he would take it up in a second environmental decade.

CURWOOD: Yeah, which did not happen, as we all know. You know, one of the things that Frank Press wrote in that memo was, quote, "The urgency of the problem derives from our inability to shift rapidly to non fossil fuel sources once the climatic effects become evident not long after the year 2000. The situation could grow out of control before alternate energy sources and other remedial actions become effective."

SPETH: The problem with the climate issue has always been that if you wait until the effects become unignorable, you will have waited too long to deal with the problem. So it's always been a question of trusting science to lead us in the right directions, rather than waiting on all the consequences to come forward. And that was the point that Frank Press and we and others were making to the President, and it was an important point, because it's still true today. We are seeing big effects of climate change today, but the biggest effects are those that are projected to happen by science, and we need to trust that science.

CURWOOD: Now, looking back to the 1970s, what was the impact of his establishment of the Solar Energy Research Institute? What difference has that decision made in coming from then to the present time?

President Carter introduced historic energy policies during his term including the National Energy Act of 1978, promoting renewable sources and energy conservation. (Photo: National Archive and Records Administration, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

SPETH: Congress had actually authorized SERI, as it was called, but it was Jimmy Carter who breathed life into it and went out to Colorado and opened it up, so to speak, put a wonderful, aggressive solar energy advocate in charge of it, Dennis Hayes, and at that time, established a national goal of moving to 20% renewable energy by 2000, which is an amazing thing for the President to do at that time. I take some pride in that number because we had just earlier issued a report from the Council on Environmental Quality calling for a dramatic shift to renewable energy, and it urged the President, in this report to move the country in this report to move to a goal of 25% renewable by the year 2000. As we were, we felt like we had done an important thing when he announced 20%. That was close enough to what we had hoped for. So he was attentive to what his environmental advisors said, and I always appreciated that, and I appreciated the decency with which he treated me as the person.

CURWOOD: How did President Carter handle the ridicule that he was subjected to when he famously put on that beige sweater and told us to turn down our thermostats, and the public response was not exactly favorable?

SPETH: Well, he did a lot of things where the public response wasn't exactly favorable, because he had a powerful internal compass, a powerful internal sense of right and wrong. I think it grew out of perhaps some of his upbringing. So when things didn't go exactly as the politics might have preferred, he stuck by his guns and wasn't perturbed that much. There have been a lot of articles recently about his presidency, and one of the things that they have pointed out, with some regularity is that he was not of Washington. He was from another place, and I don't think he ever tried hard to fit in and to become part of the Washington establishment, and it cost him politically, but he was able to keep his path on that compass point.

CURWOOD: Now concern with the climate by Jimmy Carter is juxtaposed with his concern about energy supplies, and the pretty hard push that he made for coal. He started talking about so called syn fuels, related to, to a certain extent, to the technology the South Africans used to have mobile fuel when they were under embargo. What's your understanding of how Jimmy Carter balanced the need to deal with getting rid of fossil fuel and his call out that we take advantage of all the coal that we have in the United States?

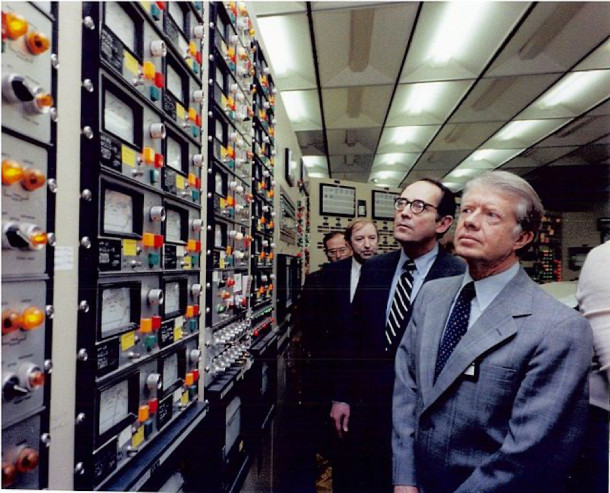

With a background in nuclear engineering from the Navy, President Carter (right) was aware of the risks associated with nuclear energy, and took initiative to slow its growth until the technology was safer. Here he stands at a control room at Three Mile Island with then-governor of Pennsylvania, Dick Thornburgh (center right). (Photo: Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

SPETH: Well, the take advantage business all had to do with the soaring oil imports and our dependence on OPEC and his determination to shift us from this foreign dependence and reliance on uncertain international supplies and shift it towards domestic resources and using our domestic resources. And of course, the United States has always had a lot of coal and it has a lot of other fossil fuels. Today, we are the biggest exporter in the world of fossil fuels. So that was a dilemma that he faced from the very beginning. And I think the way that he put it together was that we had to see domestic fossil fuels as the transition to a different energy future. Because as many times as he talked about shifting to domestic resources, he talked about solar energy and renewable energy as being the long term future for the country, and he expressed that in a way that no president ever had since, that this was the future and developed big solar programs, symbolized by, of course, putting those solar collectors on the White House roof. But there was a lot more to it than that. So I think the answer to your question, Steve, is that he, he saw the fossil fuels as a transitional phase getting us to a world in which we were really relying overwhelmingly on renewable energy resources and a dramatic increase in energy efficiency. Carter did a lot. I mean, he ramped up the fuel standards for automobiles and put in place major conservation programs. And it was a big part of his budget that Reagan killed.

CURWOOD: So Jimmy Carter went to the Naval Academy, goes into the Navy, starts working on nuclear subs before he comes back to planes. I guess the family business changed. But what was his understanding of nuclear energy policy? Because back in that Frank Press memo, there's a call for hey, let's have more nuclear because it's carbon free.

Jimmy Carter helped dramatically expand public lands in places like Alaska. (Photo: Bureau of Land Management, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

SPETH: Carter had always had reservations about nuclear power reactors, and despite his training as a nuclear engineer and his experience with the submarine program. And I think what he saw was the problem of waste accumulating at these reactors and no one knowing what to do with them or where to put it. So he had mentioned in the campaign that we should consider halting the development of new nuclear power plants until we had solved the waste problem. So when I was a youngster in the Council on Environmental Quality, I gave a speech in which I called for halting the development of new power reactors until we had solved the waste problem. And it created quite a consternation in the White House, because I'm afraid I hadn't gone through the process of getting approvals.

CURWOOD: Uh oh.

SPETH: And so Carter forgave me. So he had reservations that go back before he was President, but the big thing that happened in his administration was that, people forget that Nixon had launched what is called the Breeder Reactor program, or was called, and the plan was to build hundreds, literally hundreds of breeder reactors, a new type of power plant, by the year 2000. The problem was that these reactors were more prone to accidents than the current reactors, and also the whole point of producing these new reactors was that they would breed plutonium fuel. And plutonium is not only one of the most deadly radioactive substances, but it also is weapons grade material that can be used for nuclear explosions, but in the end, he basically terminated the program to build breeder reactors and have what's called nuclear fuel processing, which would extract the plutonium. So we're all a lot safer today thanks to the Carter's initiative in that regard.

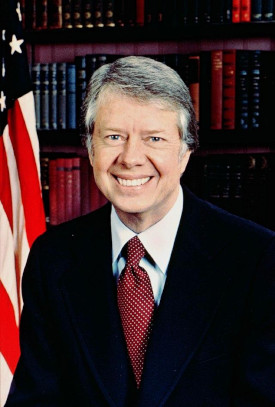

Gus Speth remarks that Jimmy Carter’s administration showed deep appreciation of science and care for the environment. (Photo: The White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: So we've been talking a lot about energy and climate and, in our discussion about Jimmy Carter, but let's turn to his legacy in nature. Talk to me about the public lands that President Carter was involved imposing protections on, and what that means for us today.

SPETH: Well, what it means for us today is that he doubled the size of the national park system, largely in Alaska, but, but not exclusively. And it was one of the great conservation initiatives of, was the greatest conservation initiative in the country since Teddy Roosevelt. It wasn't just land that he protected. He issued executive orders on protection of wetlands and protection of flood plains. We wrote in his administration, got passed the strip-mining legislation, the hazardous waste cleanup program, the super fund, and, of course, the 100 billion acres in Alaska. And what is sometimes forgotten was that Carter's first big initiative in land and water was to go after and try to kill a bunch of really destructive and expensive and ineffectual major water projects. There were huge dams and ditching that was proposed, and in the end, he, he was able to kill about 20 of these, these efforts, but it was politically quite costly for him, because he lost a lot of support in the Congress, but it was a sign of his determination to save the landscape, to make our streams and rivers free flowing, and to protect the wetland areas that are associated with those streams and rivers, rather than flooding them and ditching them.

Gus Speth (right) remembers President Jimmy Carter (left) as a man of integrity and foresight. (Photo: The White House, courtesy of Gus Speth)

CURWOOD: So how did President Jimmy Carter handle the regulatory agencies while he was in office?

SPETH: Well this is a great unsung accomplishment, because, you know, a lot of the fabric of our country is built up on the sort of routine decisions that regulatory agencies make, and Carter put in place the strongest group of regulators that the country has ever seen. He had a man named Douglas Costle, the head of EPA, Carol Tucker-Foreman, the head of Food Safety and Agriculture. Joan Claybrook, the head of Auto Safety. Eula Bingham, the head of Occupational Safety. I mean, these people were determined to pursue the public interest in a way that was unprecedented then and has rarely been matched since. And they got a tremendous amount of good work done protecting the public and the environment for the future.

CURWOOD: What do you think Jimmy Carter would make of where we are now if he were actively engaged in policy around climate?

SPETH: Well, I think he would say that we're in a hell of a pickle right now because we didn't do what we could have done over the past four decades. I don't think he would say I told you so, but I'll say it: he told us so, and we, you know, we had the possibility of pursuing the lead that he gave us on renewables and efficiencies and other climate actions, and we had four decades. It could have been a smooth transition out of fossil fuels, and now we are faced with an emergency transition out of fossil fuels because we didn't act over those four decades with the kind of wisdom and foresight and determination that we could have and should have.

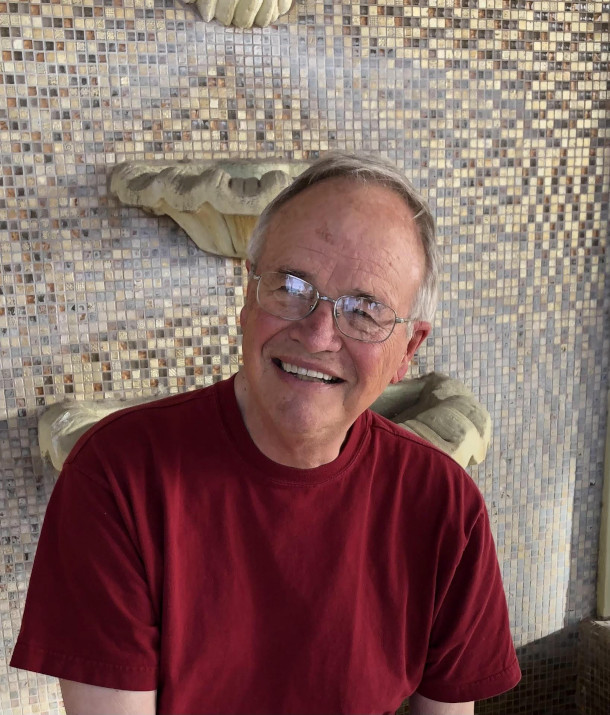

Gus Speth has since retired from his career as an environmental lawyer and advocate and has written five books of poetry. (Photo: Cameron Speth)

CURWOOD: Gus Speth, in your view, how should the world remember Jimmy Carter?

SPETH: Well, I hope they'll remember Jimmy Carter in the way that that I learned to appreciate him and and remember him. You know, he was a determined person with very high standards, a man of great integrity who believed that government could improve the lot of people in our country and indeed around the world, with his famous international work on human rights. He was principled, he was green, he was informed, he appreciated science, and he said, I'll never lie to you. I'll never tell this country a lie. And I think he stuck by that, and it's such a sharp contrast with what we have today.

CURWOOD: Gus Speth, Chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality for President Jimmy Carter. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today to remember President Carter.

SPETH: Well, it was my pleasure. It's good to see you again, Steve.

Links

History of the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (formerly Solar Energy Research Institute)

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth