Searching for Old Growth Forest

Air Date: Week of February 7, 2025

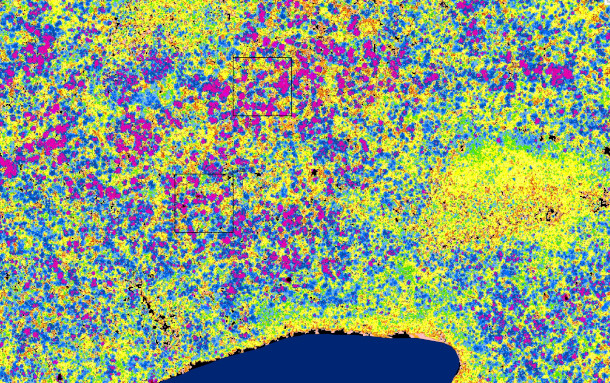

LiDAR is like a “CAT scan” of the forest, our guest Dr. John Hagan says. The blue-magenta signature indicates late-successional/ old growth (LSOG) forest. Above, a LiDAR image of Big Reed Forest Reserve in northern Maine. (Photo: John Hagan)

Finding the last remaining old growth in the vast forests of Maine is like finding a needle in a haystack, but LiDAR technology is helping pinpoint these biodiversity hotspots so they can be protected. Ecologist John Hagan of Our Climate Common joins Host Jenni Doering to discuss how it works and why it’s bringing the timber industry and conservationists together.

Transcript

BELTRAN: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Paloma Beltran.

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering.

In the remote northern half of Maine, forests dominate the landscape. While few people live in what’s known as the “unorganized territory,” timber companies control vast swaths of land there and frequently harvest trees for housing, furniture, paper, and more. But technology is revealing hidden gems in this part of the state. The non-profit Our Climate Common has recently begun using light detection and ranging, or LiDAR, to find patches of biodiverse old growth forest. Dr. John Hagan is President of Our Climate Common and holds a PhD in Ecology and he joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth, John!

HAGAN: Good morning. Nice to talk to you today.

DOERING: So, give us a sense, please, of what the forests in Maine are like for someone who's never been to the state. What kind of natural landscapes would they encounter there?

Dr. John Hagan is President of the non-profit Our Climate Common and holds a PhD in Ecology. (Photo: Courtesy of John Hagan)

HAGAN: Well, it's dominated by Northern hardwoods and boreal spruce fir forest, and it's enormous. It's like 10 million acres of nobody's there, but forest. And it's a really remarkable part of the landscape that in New England we don't really appreciate is there.

DOERING: So, in this vast wilderness, I understand that your organization, Our Climate Common, is using a technology called LiDAR to map these forests. How does this technology work, and what exactly are you trying to illustrate or discover with these maps?

HAGAN: We are using light detection and ranging, the LiDAR, to try to find the old growth forest in the vast 10 million acres. It's like looking for a needle in a haystack. It turns out that LiDAR is kind of like a CAT scan of the forest. If you shoot LiDAR at the forest from an airplane, it gives you a three-dimensional signature of the forest. If you know art history, it's kind of like pointillism. It's just a massive three-dimensional point cloud of the forest. And that turns out, can tell us exactly where the old forest is. About 4% of that 10 million acres is old growth forest. So, in a way, not very much by percentage wise, but a lot, if you let's see, that's about 400,000 acres, that's a lot you didn't know you had, and you don't want to lose.

DOERING: And so how do you identify old growth using these maps? How do you know that what you're looking at is a patch of old growth trees?

About four percent of Maine’s vast northern wilderness is considered late-successional/old-growth forest, which amounts to about 400,000 acres. Dr. John Hagan measures a tall, old white pine in Baxter State Park. (Photo: Ben Shamgochian)

HAGAN: So, we do the fun part, which is we go out on the ground across this 10 million acres, and we go into stands, forests, they're called stands, and we score them based on our ecological knowledge. And then we come back into the lab and say, computer, what did you see? This is what we saw. What did you see? And then we train the computer to find the stuff that we found on the ground. We can't cover 10 million acres on foot. I would love to, but we can't. So, the LiDAR does that for us, and it's incredibly accurate, more than 90% accurate. We didn't know before LiDAR and how we used it to map it, we didn't know where it was. You had to stumble upon it, the old forest, to find it or to know about it. Now we've got a map. And the older stands are blue magenta. Everything this younger is yellows or oranges or light greens. You can color it any way you want, but it's kind of like a neon sign. It's like light up this old growth forest on the map, and LiDAR is, I call it magic. I'm supposed to be a scientist, but to me, LiDAR just seems like magic, what it shows you about the forest.

DOERING: So why is this important to know where these late-stage old growth forests, or I think they're called LSOG, are? Why are they so crucial to protect?

Aerial photo of old-growth forest discovered by the Our Climate Common team using LiDAR. Before employing LiDAR, “We didn’t know where [the old-growth forest] was,” our guest Dr. John Hagan says. (Photo: John Hagan)

HAGAN: It's not surprising that a lot of plant and animal species evolved in an older forest landscape. They evolved to depend on big dead wood. So, when you don't have big trees and big dead wood, you start to lose some of the species that evolve to depend on that. And so, if we don't keep some old forest, we will lose that element of biodiversity. And old forest like LSOG has enormous stocks of carbon today, even if they're not storing any more like as much wood is dying as is growing, and often in an old growth stand, but the stores are like five to 10 times what an average forest would hold in current stocks.

DOERING: Wow.

HAGAN: So, you if you lose it, you lose a lot of carbon per acre with the loss of LSOG stands.

DOERING: That's an incredible amount of carbon storage, five to 10 times?

HAGAN: Right. But the younger stands, you know, a 40 or 30, 40, year old stand is growing fast, so often it will be sequestering carbon much faster than an old stand, but it's got a long, long ways to go to get to the stocks of an old forest.

DOERING: So, from what I understand, the New England Forestry Foundation recently received $4.3 million from the US Forest Service and your maps of Maine's old growth forests are playing a big role in how they plan to use that grant. So how are they making use of the data that you've collected?

Late-successional/old growth trees can hold 5-10 times the amount of carbon as younger trees. PhD student Molly Taylor gets ready to survey a late-successional hemlock stand. (Photo: John Hagan)

HAGAN: Well, most of the remaining LSOG forest is on commercial timberland, private commercial timberlands, people who are in the business of making wood and paper and stuff like that. So, the challenge is, how do you compensate landowners to keep them because they're just losing out financially to let them grow. And it looks like to us, the value of the carbon in these old stands is worth as much and maybe a little more than the timber value. Then it just becomes an economic transaction. Look, I own this land. I would normally cut timber, but if the carbon is worth more, I'll sell you the carbon and keep the stand. So, if the New England Forestry Foundation has all this money to pay landowners, we could say, go here. This is a big stand. It's going to be harvested in the near term. Go there first. So, we've got a road map, literally a map, to say, this is what we should do first.

DOERING: Hm. Gives you a place to start. These are the highest priority stands. So, let's protect that.

HAGAN: That's right. And it could be on public land and already protected. We don't need to worry about that, but if it's on commercial timberland, most likely it's destined to be harvested in the next five to 10 years. So that's why matching the financial opportunity with landowners could prevent loss of these older stands like, right now.

While some old-growth forests in northern Maine are protected, many are on commercial timberland and risk being cut in the near future. Aerial photo of Big Reed Forest Reserve, a 5,000-acre old-growth forest in northern Maine. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: So of course, you know, demand for wood, for furniture, houses and other goods, isn't stopping anytime soon in New England. So, what about these younger forests that would still inevitably be cut down by these large timber companies? Wouldn't they also eventually become old growth, if left alone?

HAGAN: If left alone, they would, but they're not going to be left alone, because that's not the goal of the landowners. But you make an important point that is a fault, or a flaw of some forest offset projects like, well, you protected that stand and that stand and that stand, but they're just going to cut another stand because we need a fixed amount of wood. It's called leakage in the carbon offset marketplace, and it's a problem. Things just move around like pieces on a chessboard, because wood is a globalized product. The atmosphere is a global entity. In our case, and what New England Forestry foundation plans to do, is have landowners and take the proceeds from paying for the old stands and invest in silviculture, forestry practices, on the other acres that would accelerate the growth of those stands so that we don't leak, and we don't just push the carbon off to some other place and it ends up in the atmosphere anyway, and that's why, in the end, we need to be growing more carbon per acre, and that's the way forests can help with getting carbon out of the atmosphere. But it's complex, and if you don't cross all the t's, you end up not making a difference.

With help from a $4.3 million grant from the US Forestry Service, the New England Forestry Foundation hopes to compensate timber companies for keeping old growth stands. Ben Shamgochian (front), forest ecologist with Our Climate Common, and Molly Taylor (back) measure a large, downed log in Big Reed, an old-growth forest in remote northern Maine. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: Why is it important to work across different groups? You know, working with the timber industry, working with conservationists, bringing these different stakeholders together, as opposed to just trying to dig your heels in and say, we're not going to work with you.

HAGAN: My whole career, I've been working collaboratively with people like fishermen and foresters, and I find that they know stuff I do not know. And if I don't know what they know, I can't solve the problem that I'm trying to solve. You know, I got this idea, and they say, well, that's just not going to work, John, the machine can't get there. And so, I didn't know that. So, the traditional ways to do battle, you never really take the opportunity to respect the other person, understand what they know and value what they know. When you do, it just changes the whole problem-solving landscape, and it works. And I think in Maine, especially with this grant, we've got an opportunity to all sit down together and say, what should this look like in the year 2100 and say, okay, we can make it look like that. If we're smart about it and we collaborate, we can do it differently this time, and this grant will help move us that way.

Molly Taylor (left) and Ben Shamgochian (right) examine an old snag in a late-successional forest. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: Do you have a favorite spot in the forest in one of these old growth stands in Maine, and what's it like there?

HAGAN: Well, that's a good question, too. In one of our plots that our stands that lit up in LiDAR, we went in and did our measurements, we core one tree. It doesn't hurt the tree, for anybody who might be worried about that, but it pulls out a core of the tree, and then you count the rings to see how old the tree is. We pulled out a core of this tree, and it was 253 years old, and it was like typical of these old stands we're finding. And then I started thinking about Henry David Thoreau, who walked through Maine in like 1850 something, he could have walked by this tree, literally. I mean, this is kind of silly, but he could have walked by this tree because it would have been 70 years old when he went through Maine. It was a seedling when the first shot was fired at Lexington for the Revolutionary War. So, when you know you're standing beside a tree that old, that's been around that long, it is intangible. It's special. It's just like, wow. It puts you in perspective.

Ben Shamgochian with a 150’ tall white pine in Baxter State Park. (Photo: John Hagan)

DOERING: John Hagan is President of the nonprofit Our Climate Common and holds a PhD in Ecology. Thank you so much, John.

HAGAN: You're welcome. Thank you.

DOERING: By the way, the New England Forestry Foundation does have a signed contract with the US Forest Service regarding that $4.3 million grant. But along with many other federal grants, it has come under threat of freeze by President Trump’s Executive Orders. While the courts have temporarily blocked the freeze, Senior Forester at NEFF Brian Milakovsky says his organization is still waiting on legal clarity about how the executive orders could affect the grant.

Links

Read more about Our Climate Common

Read more about the New England Forestry Foundation

Maine Public |"Digital tool reveals Northern Maine's rare old forest"

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth