"Climate Whiplash" Between Extreme Wet and Dry

Air Date: Week of February 14, 2025

The January 2025 LA wildfires were in part exacerbated by a climate whiplash event, from extreme wet to extreme dry conditions. (Photo: timatymusic, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Global warming is increasing the frequency and severity of “climate whiplash” events, which are rapid transitions between very wet and very dry conditions. One such event set the stage for the devastating L.A. wildfires in January 2025. Dr. Daniel Swain is a climate scientist with the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources and joins Host Paloma Beltran to explain how climate whiplash works and what societies need to do to prepare.

Transcript

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

BELTRAN: And I’m Paloma Beltran.

In the last few years we’ve seen increased rates of catastrophic flooding and droughts. And as we continue to crank up the global thermostat, Earth’s water cycle is changing. In a new paper published in Nature Reviews Earth and Environment, scientists analyzed hundreds of previous studies on how global warming is affecting the water cycle. The authors focused on “hydroclimate volatility,” or climate whiplash, the rapid transition between very wet and very dry conditions, or vice versa. They found that global warming is increasing the frequency and severity of climate whiplash events around the world. And if we pass the threshold of three degrees Centigrade of warming, these events will likely more than double across all kinds of climate zones. Dr. Daniel Swain is a climate scientist with the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources and lead author on the paper. Welcome to Living on Earth, Daniel!

SWAIN: Thanks for having me.

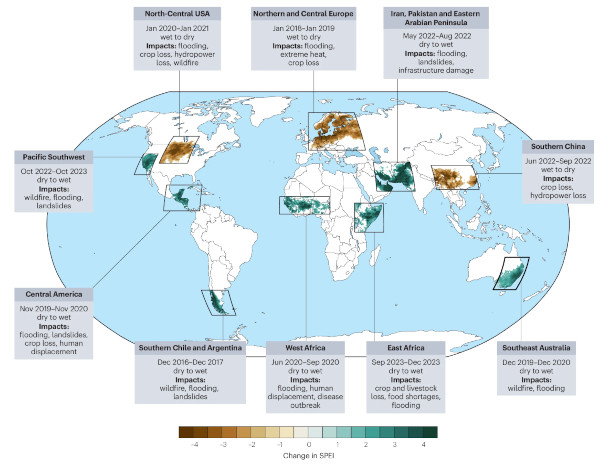

BELTRAN: So what does climate whiplash look like around the world? You know, give us a sense, please, of how this is playing out in real time?

SWAIN: We've, in this paper, identified a number of globally consequential events that have unfolded just in the past decade, and this isn't even a comprehensive list. One of the more recent ones that actually had occurred immediately before the paper was published, coincidentally, was the much discussed wet to dry whiplash event in Southern California that immediately preceded the catastrophic wildfires in Los Angeles in January of this year. And this wet to dry whiplash event was really important in this context, because the wet part of it allowed a lot of extra growth of grass and brush, which is the main kind of vegetation that was burning in the LA fires, and then the exceptional to record breaking dry period that followed allowed all of that extra biomass to become essentially record dry at the time of year when we get these strong, dry wind storms in the LA area. So that's in some ways the worst possible combination for wildfire in this part of the world. And I think this is a good example of why the whiplash events are in some ways greater than the sum of their parts, in the sense that the fire risk was actually potentially worse in LA this January than it would have been if it had just been dry the whole time. But that particular sequence from wet to dry, with the vegetation growth then desiccation cycle, is what set the stage for the fire disasters to unfold as they did.

With each degree of warming, the frequency of climate “whiplash” events, or rapid swings between wet and dry conditions, will increase across the globe. (Photo: Swain et al. 2025)

BELTRAN: How exactly are climate change and rising temperatures impacting hydroclimate volatility? You know, what mechanisms are at play here?

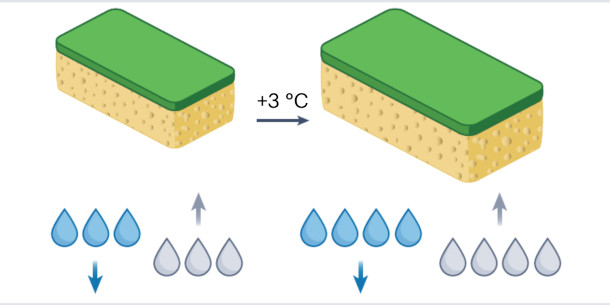

SWAIN: Well, most of what's going on actually goes back to the somewhat fundamental thermodynamics of the atmosphere, science that was actually understood beginning in the mid 1800s, so some of our citations in this paper are from the better part of two centuries ago, believe it or not, long before we had climate models. But the basic idea is this: as air temperature rises, the capacity of that air to hold water vapor increases rapidly by about 7% per degree centigrade, or 3 or 4% per degree Fahrenheit of warming. So we essentially encompass all of this in an analogy that we call the expanding atmospheric sponge effect, which is something we coined in this recent paper. You can demonstrate this by taking a small sponge and then a much larger one, and then trying to absorb some water from a container. So the smaller sponge, of course, will absorb a small amount of water. You can wring it out, it yields a certain amount of water. And then the larger sponge, if you put it in a larger container of water, it will absorb more of the water, and then if you wring it out, will yield more water. That's analogous to the increasingly extreme downpours that we see. But it's also the case that that really big sponge still has the capacity to absorb a lot more water, even if there's no water in the container to absorb. And so it retains that thirstiness, that sponginess, if you will, and that is what drives a lot of the effects on the dry side, so worsening droughts and drought related phenomena like wildfires, for example.

BELTRAN: So from what I understand here, hydroclimate volatility doesn't always mean that if I'm in a dry place, it'll get drier, or if I'm in a wet place, it'll get wetter. What framework would you suggest using to make sense of this?

In a warming climate, the atmosphere acts like the larger sponge pictured above. A “thirsty” atmosphere is able to absorb and release more moisture, driving both extreme wet and extreme dry conditions. The authors of the paper call this the “expanding atmospheric sponge effect.” (Photo: Swain et al. 2025)

SWAIN: That's right. You know, what we find is that some places on earth in a warming climate, on average, will get wetter and other places will get drier on average. It really does depend where you are. And you know, in this context, I think it makes sense to think about potentially, that the wet times wherever you are getting wetter and the dry times getting drier. Increasingly, when it does rain, it pours, and when it's very dry, it becomes even drier.

BELTRAN: So how is agriculture going to be impacted by these extreme swings in climate conditions?

SWAIN: Well, you know, agriculture as a largely successful practice for much of modern human civilization, and partly, I think we can credit the success of modern civilization to the success and the advances in agriculture is predicated on a certain level of stability. And where we see periods of instability, whether it's in the climate or the weather or anything else, that tends to be where bad things happen, where people don't have enough to eat, where we see famines occur historically, or food insecurity more commonly today, and what we find is that both kinds of whiplash -- wet to dry and dry to wet -- have both historically been associated with major food security emergencies. Because you can imagine that if you're trying to grow food staple crops, it can be really disruptive to have any kind of sudden change. If you go from wet to dry, your crops may run out of water and bake under the hot sun. But if you go from dry to wet, you might wash your crops away or contaminate the fields potentially. So really, the challenge here is that some of the adverse impacts from these events occur precisely because the transition has been rapid. It's not just that you have a drought, it's not just that you have a flood. In some cases, those might be more manageable on their own, independently, but in other cases, it's the sudden swings, the transition period that just catch people, systems and ecosystems off guard.

Agriculture, which relies on stability, will be disrupted by increasingly frequent climate whiplash events. (Photo: NightThree, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

BELTRAN: How can government officials and urban planners better prepare for increased instances of climate whiplash? I mean, how do you simultaneously prepare for both extremely wet and extremely dry conditions?

SWAIN: Well, the first step is to acknowledge the reality of increasing projected hydroclimate whiplash in the first place, and to realize that just because your region has recently experienced a lot of drought on the one hand or a lot of flooding on the other does not mean you won't face extremes on the other end of the spectrum. This has been a conversation even in the US and in California, where I work extensively, where there has been a lot of focus on drought and wildfire in recent years, for understandable reasons, but the risk of major flooding does loom large in the background, and I think is a little bit less front of mind. We really need to be thinking about co-managing risks at opposite ends of the hydroclimate spectrum. This can be using co-management tactics like flood managed aquifer recharge, so taking some of the water that you might otherwise have in reservoirs used for a combination of flood protection and water storage during the dry years, moving some of that water to a place, either through restoring flood plains or building recharge basins, and essentially allowing it to percolate back down into widely overdrafted aquifers. So, essentially storing some of that water underground rather than keeping it behind dams. And the reason why that's a good intervention in a lot of cases, is because it is both drought and flood and whiplash aware. So by having less water stored behind the dam, you have more flood buffering capacity, you've essentially given yourself a wider safety margin. But you haven't essentially moved that water somewhere else. You've actually still stored it for use during the drought that might follow. So there are some sorts of interventions like this. That's one example at a large scale. There's also the notion of sponge cities, for example, how cities have a lot of impervious or water impenetrable surfaces, pavement, concrete, things like that, but allowing for more locations within cities for rainwater to percolate downward into the soil is mutually beneficial for, again, reasons that span the spectrum of wet and dry. So during extreme rain events, the more water that can soak directly into the soil, the better flood buffering capacity you have, but also the more water you've put into the soil for when the next dry spell comes. So again, keeping in mind both ends of the spectrum and the transition risks involved, and co-managing those potential risks, I think is really the way to be thinking about this.

“Sponge cities” seek to decrease impermeable surfaces in urban areas, allowing for water to percolate down into the soil and protect against flood risk. (Photo: Pixabay, Pexels)

BELTRAN: Dr. Swain, what do you hope people will take away from your work on climate whiplash?

SWAIN: So I think one of the key takeaways is that increasing hydro climate whiplash, even if it hasn't emerged yet locally in your backyard, it probably will, sooner rather than later, with continued warming. This really is going to be, in all likelihood, a near universal experience over global land areas, nearly as much so as the warming temperatures themselves. And that tells us something about what the world is going to look like, and perhaps partly explains why we've experienced a lot of the things that we have recently. So there's been all this conversation in the wider world about how it feels like global warming has suddenly gotten worse in the last five or ten years, and I think increases in hydroclimate whiplash globally are potentially part of the reason why it feels like things are accelerating – it’s because they are. Hydroclimate whiplash increases at a faster rate than temperatures. So it probably should feel like we're seeing increased cycling between extreme wet events and extreme dry events, and the kind of associated transition risks like wildfires, because that is, in fact, what the climate models tell us the world should look like at this point and will continue to look more like moving forward. And so I think it does help us understand what we're seeing all around us today, on the one hand, and also hopefully gives us a clearer sense of what the future will look like, which is to say that we are going to see not just drier drys, not just wetter wets, but both, and often in the very same places.

Dr. Daniel Swain is a climate scientist at the California Institute of Water Resources within the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources & Institute of the Environment and Sustainability at UCLA. He is also a lead author on the paper. (Photo: Jilmarie Stephens)

BELTRAN: Dr. Daniel Swain is a climate scientist at the University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources. Thanks so much for joining us.

SWAIN: Thanks again for having me today.

Links

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment | “Hydroclimate Volatility on a Warming Earth”

The Guardian | “Climate ‘Whiplash’ Events Increasing Exponentially Around World”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth