Faith and Environmental Justice

Air Date: Week of June 20, 2025

President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act in 2021, making Juneteenth a national holiday. (Photo: The White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond and Host Steve Curwood continue their conversation with a look back to how she first became engaged with environmental justice. Rev. White-Hammond also shares her reflections on the importance of engaging hearts as well as minds on the climate crisis, and how she helps bring eco-theology into faith communities.

Transcript

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

And we’re back now with ecological and social justice leader, the Reverend Mariama White Hammond.

CURWOOD: So Mariama, you grew up in Roxbury, Massachusetts at a time when it was a largely Black community. Tell me about the moment when you realized that your home was what some might call an environmental justice community.

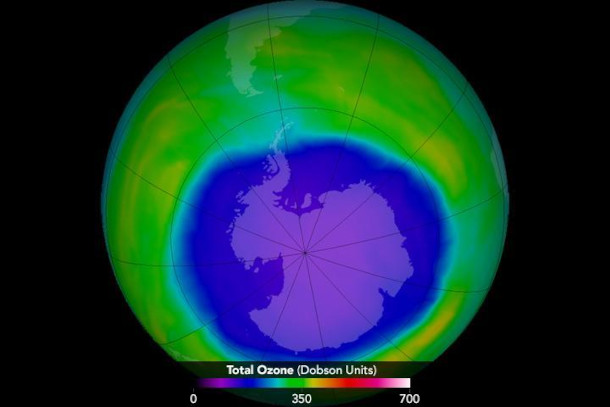

REV. WHITE-HAMMOND: Yeah, so let's see. I grew up in Roxbury. I mean, it was the place that I knew. And I remember in sort of beginning of high school, I got engaged around issues of the ozone layer. And I remember sort of thinking, oh my gosh, I can't believe humans could cause that kind of damage to the planet. It was the first time that I, I knew that we could do better, right? I knew that we have done things to each other that are terrible, but it was the first time I recognized how our actions, or lack thereof, in some instances, was causing damage on a planetary scale. And so I got very involved. And then I went to a meeting of the environmental club at my school, and I remember that they were talking about polar bears and dolphins, which, you know, beautiful creatures, but this was in the 90s, in the height of violence in the city of Boston, and I'm sitting here like, wait a second, how can you be deeply invested in saving creatures that you've never seen, but have no investment in the neighborhoods that were less than two miles from our school, where people were also really struggling? And so I couldn't see myself in that space, and I sort of walked away. I mean, I continued to do, you know, some basic things like recycling and other things like that, but I just decided that that wasn't really a cause that I could engage with. And it wasn't until I went to college, I went to college in the Bay Area, and I was working at a tutoring program with young people, both because I loved working with young people and because I needed a job in order to cover my books. And so, I was working there, and the young people in Palo, in East Palo Alto were organizing because another cement plant was going to come to their community, and they already had quite a bit of pollution in their neighborhood. And so I really got engaged, because the young people that I was tutoring were engaged, and then as I was listening to them, I was like, wait a second, some of the things y'all are talking about, that's the same thing in my community, we had a trash transfer station in our community. We had one of the largest public transportation bus terminals in our community, and that was releasing lots of air pollution. I knew tons of people who had asthma, including people in my family. So I'm starting to say, okay, I'm here in solidarity with you as a college student at this, you know, privileged school, but everything that you're talking about as I really think about it, that's also the things I was experiencing in my own home neighborhood, and so I came back to my neighborhood with a different sense of necessity to also organize around those things at home, that those things that I had grown up with were not okay. They were not natural. Unfortunately, it was a shared experience with many communities of color around the country, and we needed to do something to change it. And so during college and in the years afterwards, I got more engaged around environmental justice issues in my neighborhood, and I wish that the high school that I went to had been framing its environmental work around those same kind of issues, because we didn't have to go to the North Pole in order to find environmental issues to work on. We really could have just gone down the street. But I'm thankful for that experience, and I'm thankful for the leadership of the young people in East Palo Alto that helped me see my own community in a different way.

Reverend Mariama White-Hammond first became involved in environmental activism over the ozone layer when she was in high school. The ozone layer in 2015 is shown above. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yeah, East Palo Alto. It sounds like a fancy address, it is not.

REV. WHITE-HAMMOND: No, it's not. Well, it's gentrifying these days, so it's becoming fancier and fancier. But there, when I was in school at Stanford, there was this stark line, like you would drive down, actually, I would ride my bike down the road through Palo Alto. I mean trees galore. I mean these beautifully manicured lawns, and the houses weren't even that big because they were extremely expensive. But I mean, and then you would hit this overpass over this stream some of the time and ditch some of the time, right? They have rainy season and dry season. So anyway, and it, I mean, the tree canopy could not have been more stark. It was just so obvious where Palo Alto ended and East Palo Alto began. Now, because of gentrification, there's literally a Four Seasons around that neighborhood because they're expanding into East Palo Alto, but I remember how clearly the visual inequities just slapped you in the face. And that continues to be true in that neighborhood and so many, so many others. Sometimes you cross from, you know, Roxbury, towards parts of Brookline, and it changes quickly. So that is, unfortunately the kind of thing in our country that we still need to be working hard to address.

While tutoring in East Palo Alto as a college student, Rev. Mariama White-Hammond realized her hometown of Roxbury, MA faced many of the same environmental challenges. (Photo: Ardenmachro, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: So Mariama, what's missing for you from the environmental justice movement these days, and to what extent might faith and the faith community fill that gap?

REV. WHITE-HAMMOND: Yeah, so I think there has been a lot of work on good policy, and that is important. You know, obviously I spent my time in city hall focused on policy, right? And I do think that needs to happen, but we have some good policies that we can enact if we have the will to do so. And we've got a will problem. We've got a will problem in this country, we've seen people be led to believe that we have to choose between environmental stewardship and human flourishing, and it's absolutely not true. We can have both. In fact, the two can work really well together, but that is a heart issue. And I think for me as a person of faith, what's been funny is I've been surprised by how many scientists, businesspeople, atheists have said to me, we need more of the faith community to get involved. You would think that, like there would be a resistance in some quarters, but I haven't experienced that. I think many people in the environmental movement recognize that, really, we're in a struggle for our lives, right? It is partially about the planet. Absolutely, the planet is being harmed. But the reality is that the planet has survived multiple times, has made a comeback throughout history multiple times. What is at risk is the possibility of human species being able to survive, as we have for generations in this world that it could get a little too hot for us, that it could get to the point where we are flooded out of the places that mean something to us, where we lose our access to fresh water in communities that are facing very, very real drought challenges and a lack of fresh drinkable water. So, the risk actually, yes, we are causing great damage to other species and biodiversity, and that is criminal. That being said, our ability to survive is also tied up in how we treat our non-human siblings, and it is a moment in which humanity really needs to become its best self. We have got to be better than we have been in the past, and definitely better than we are being right now. And that is spiritual work. So yes, we do need good policies. I would, loved crafting policy and working on it. But if humans do not embrace the call of this moment to choose our ecology over our economy as it is currently constructed, we will not get through this moment.

Rev. Mariama White-Hammond described the summer of 2020 as a “moment of deep reflection” for the nation, with the death of George Floyd reigniting the Black Lives Matter movement just weeks before Juneteenth. Above, protestors march in Duluth, Minnesota on June 19, 2020. (Photo: Mollerus, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: My guest is the Reverend Mariama White-Hammond, the former Chief of Environment, Energy, and Open Spaces for the City of Boston, and pastor of the New Roots AME church in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Yet not all of society supports the call for climate and environmental justice.

REV. WHITE-HAMMOND: I do think that what we're seeing right now in the backlash that we're seeing, in the sort of confusion and chaos of this moment is that I think humanity is a little confused about if we can rise to this moment and how we do it. I think we have gotten scared that there's not enough for all of us, and so that we have to, you know, choose some people over others. And from my perspective, all of our faith traditions tell us that that is not the way that God calls us to be. And so I do think this is a moment in which the faith community really has to rise to the occasion to help us do some of the heart work and some of the spiritual work we need to do to face this moment, not with fear and not with scapegoating and not with a sense of scarcity, but to lean in with joy and abundance and deep, deep love and trust that if we choose a path that takes care of us all, we can and will survive. And I'm not trying to pretend like there won't be tough choices. There will be some tough choices. There are some things we have embraced that we're going to have to leave behind. Once again, that's some spiritual work to recognize that we can't do things as we've been doing, that we need to change and we need to transform. But I actually think we could be better on the other side. Right now, everybody, both, sometimes some of the environmental advocates and the folks who are sort of climate deniers are framing this as though we are going to lean into a world that is so terrible and awful, and I'm not saying there won't be some level of sacrifice, but I see a possibility for deep joy. To stop trying to zip all around the world and work every last hour and burn the candle on both ends, but to actually slow down and to be together and to find joy in our kids running around and to make really good, healthy, yummy food together, and to restore communities in some beautiful ways, and turn off the TV and stop playing some of the video games, I'm not saying I'm against them all, but I'm saying the joy of being together in beautiful places and just enjoying each other's company, that is part of the invitation of this moment. And I think sometimes, even in the environmental movement, we have over emphasized the fearful things and under emphasized the joyful possibilities that also are in front of us.

CURWOOD: I've noticed as a journalist looking at the matters of environmental justice, that when I go to a Black gathering, it frequently begins with a prayer, and when I go to a largely white gathering, I almost never hear a prayer. I don't know if you've had a similar experience, because as a reverend, maybe you're always asked to make a prayer. But what do you make of that phenomenon?

REV. WHITE-HAMMOND: Yeah, so I think that it is true that in Black communities and Black cultural traditions, we do recognize that our spiritual foundations are a core part of who we are as a people. And I want to be honest. So there's complications to that, there are certainly Black folks of other spiritual traditions that are not Christian, that have been under appreciated, and there are things we need to do to make space for a diversity of voices, but I do feel there is more recognition that we are more than just workers. We are more than just beings, you know, passing through, that we also come from a tradition that says, we are our ancestors' wildest dreams, and we have a responsibility to the next generation, and that thinking aligns a lot with our Native American Indigenous siblings who come also from that tradition. This is part of what we brought with us over from our time in the continent of Africa, and that we have not lost here in the Americas. And the truth is, you know, our spiritual traditions have changed, that many of us were converted to Christianity, but we created a Christianity that did not lose our deep connection to the land and our sense that God was with us, has been with us, from the beginning. And so, yeah, there, I think there is much more openness and sense of connection in, in Black communities. Where we, many of us, have been trying to do work is to do some more re-establishing of our deep connection to the land, because I think that through the Great Migration and because of the legacy of slavery, there were also ways in which people said, I don't want to be farming anymore. Sometimes they saw that connection to the land as a source of oppression. And so many of us have moved to cities, and we've become urban folk and lost some of our connection to the land, but that has always been a deep part of our spirituality, even before we came to the United States, even before many of us were Christians. So, I think that there is so much possibility to expand our spiritual centers to also include a deep connection to the land, to restore our deep connection to the land. But yeah, I would say there's a lot more openness to spirituality in Black communities, sometimes than there are in white communities, particularly white northern communities. I'd say there's maybe a little bit more openness in the South and the Midwest, but on the coasts, especially the north side of those of the coasts, we there's some work to be done to reignite, there's some work to be done to reignite those spiritual traditions.

Rev. White-Hammond tells the story of her arrest while protesting a gas pipeline.

CURWOOD: So talk to me about some ways that you've seen your own faith community, or others around the country live their faith to protect both people and the environment.

REV. WHITE-HAMMOND: Yeah, so I just feel so blessed… because I've been doing this work. People invite me to come see things. People send me notes, and so it constantly fills my heart with joy, and I think we need to do more. And I'm grateful to be here, and grateful for the work you do to spread the good news, because people need the good news. There are good things happening. So, you know, I think of when we look at, and what I teach in my church and in some of the ministries that I have helped to build, and when I meet with other people who are looking at building faith-based creation ministries, we look at four pillars, the first being ecotheology. There are so much beauty in our texts that celebrate the natural world, the relationship between humans and non-human beings, and so sometimes we've under emphasized those things, but they're all over the text. So a lot of our work is about, how do we reignite that sense of joy and wonder and connection that's there? And so that I try to bring that into the way I preach. I'm invited to preach in other places, and I'll do trainings for other preachers that are trying to bring more eco theology into… into their practice. It's not hard. You just open your scriptures and there you go. It's there. But we've got to exercise that muscle. And also, in the music that we choose, there's some great music that is out there. And so, yeah, that's one, one pillar, the ecotheology.

Links

The Juneteenth National Independence Day Act of 2021

The National Museum of African American History and Culture | “The Historical Legacy of Juneteenth”

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth