January 3, 2003

Air Date: January 3, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The State of Our Ecosystems

View the page for this story

A new report from the Heinz Center distills environmental data from 150 different organizations, businesses, universities and government agencies. Host Steve Curwood talks with the Heinz Center’s project director Robin O’Malley about what we know and don’t know about the nation’s ecosystems. (06:20)

Conservation Cows

/ Sandy HausmanView the page for this story

California’s native grassland used to be wide and plentiful, but now, only one percent of the land remains. Conservationists are trying to restore the grasslands, and now they have a bovine ally. Sandy Hausman reports. (04:40)

Health Note/Curry Consumption

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a study that shows a common Indian spice might play a role in preventing Alzheimer’s disease. (01:15)

Almanac/Warm Winter Wind

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about a Chinook Wind that swept through a South Dakota town, causing the fastest temperature change in history. (01:30)

Precision Agriculture

/ Jeff HorwichView the page for this story

Instead of kicking back during the winter, many farmers are now keeping busy – at the computer. They’re using global positioning systems to do what’s called “precision agriculture,” which uses satellite coordinates to help map their fields. As Minnesota Public Radio’s Jeff Horwich reports, the use of this technology is helping to make planting crops a precise science. (05:30)

High Tech Booty Hunt

/ Ken ShulmanView the page for this story

When former President Clinton declassified the global positioning system, also known as GPS, it opened the door for citizen use of the satellite navigation network. As Ken Shulman reports, a new sport called geocaching has sent both outdoor enthusiasts and techno-geeks on treasure hunting adventures using handheld GPS devices. (07:00)

Ecological Indicators

/ Terry LinkView the page for this story

Economic indicators are a common part of news broadcasts. Commentator Terry Link argues environmental indicators should air alongside them. (03:00)

Animal Note/Frenzied Ants

/ Maggie VilligerView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Maggie Villiger reports on the chemical weapons a wasp uses to get into an ant nest to lay its eggs inside a caterpillar hiding inside. (01:15)

Oil in the Sea

/ Anna Solomon-GreenbaumView the page for this story

A report from the National Academy of Sciences examines the problem of oil in our oceans. How much is there, where is it from, and what does it do? Anna Solomon-Greenbaum highlights the report’s findings. (03:10)

The Grid & the Village

View the page for this story

In January 1998, a massive ice storm knocked out power in parts of northern New York, New England, and eastern Canada. Host Steve Curwood talks with Steven Doheny-Farina, a resident of Potsdam, New York, and author of the book The Grid and the Village: Losing Electricity, Finding Community, Surviving Disaster. (07:00)

Ode to a Snow Plower

/ Robin WhiteView the page for this story

We sleep while they work. Without them, economic activity would freeze. Who are the night snowplow drivers? Robin White rides with one plowman who's written an ode he reads over the CB radio, by request, to other drivers as they work. (05:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodREPORTERS: Sandy Hausman, Ken Shulman, Anna Solomon-GreenbaumCOMMENTARY: Terry LinkGUESTS: Robin O’Malley, Stephen Doheny-FarinaNOTES: Diane Toomey, Maggie Villiger

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR News - this is Living On Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Five years ago, a massive ice storm shut down power for days all across eastern North America.

DOHENY-FARINA: I woke up, my wife woke up, saying, "Ah, there's no power. Huh. It should be on soon. We'll just have to sit tight here. Let me turn the radio on. Let's hear what the status is." And there are no radio stations. I mean, nothing, not a sound. And this just doesn't happen. And the power always comes back on. Well, it just didn't come back on.

CURWOOD: What happens to a town when electricity is out of the picture? Rethinking what it means to be a community, that’s what. Also, meet the snowplowing poet of Allegheny, California.

BUCKBEE: The snow piles high, but that's all right, because I'll just hit it with all my might, and shove it over to the right.

CURWOOD: Ten-four, good buddy. Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth, coming up right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

The State of Our Ecosystems

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. To start off the new year, we’re taking a look at the state of the nation’s ecosystems. That’s the name of a report recently put out by the Heinz Center for Science, Economics and the Environment. The report catalogues everything we know about the state of our oceans, forests, farmlands and cities. It also points out the many gaps where we need more data. Project director Robin O’Malley joins me now to talk about what we know and don’t know today about the ecological health of America. Welcome sir.

O’MALLEY: Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk first about what we do know. What are the ecological areas where we have the most data?

O’MALLEY: Well, it’s very clear that among the major ecosystem types in the United States we know more about forests than we do about any other kind of system. We’ve had a monitoring and information gathering program in place for forests for a very long time and we can tell you more about the important features of forests than for any other system. It’s also quite obvious that when we look at information about ecosystems we know more about the economically important components of those ecosystems – the food we produce, the timber we produce, the fish that we catch, the water we use – than we do about the ecological condition – how many endangered species there might me and information like that. So there are certain patterns, as I say forests and the commodity and productive aspects of those systems that we know better than we do about the ecological condition.

CURWOOD: Now let’s talk about what we don’t know. What are the ecological areas where we’re very, very thin on the data?

O’MALLEY: Well, there are two that really stand out. The areas that we call grasslands and shrublands, which are primarily large portions of the American west, tundra in Alaska, places like that. And urban and suburban areas are both ones in which we had very little success in pulling together national perspectives on how we’re doing.

CURWOOD: Robin, specifically what data are we missing from the grasslands and the urban areas.

O’MALLEY: Well, in fact there’s more that we don’t know than that we do. We can’t report, for example, the ways the land is used in grassland and shrubland areas. We have large areas of those lands that are used for livestock production and cattle production, but we really can’t tell you how much of those lands are used for that. We have large areas that are used for intensive recreation or that are used for mining or oil and gas production. We can’t give you that kind of information. It’s very important to understand how fragmented these lands are. They’re broken up into little patches of grassland and shrubland or there are large expanses that are basically undivided ecological areas. We can’t tell you how much carbon is stored in the nation’s grasslands and shrublands and with climate change being as important an issue as it is, we should be able to know that information. We can’t tell you about how many non-native species are spreading across the nation’s grasslands and shrublands and with the fact that many non-native species do not serve as good wildlife habitat as native species and in fact don’t serve as good forage for cattle and other livestock a very important fact that we ought to know.

CURWOOD: And what about the cities and suburban areas, what don’t we know there?

O’MALLEY: More than half of the indicators we were not able to report at a national level. These include things like the amount of impervious surface, the amount of paved surfaces and roofs and driveways and sidewalks and this is an indicator that has enormous importance for water quality, for amount of heat that builds up in central city areas, and we simply don’t have that kind of information. Another one that’s in the news very frequently is sprawl, this sort of development pattern at the outer edge of suburbia where it goes from being clearly suburban to being rural and there’s development that happens that kind of breaks that area up and is sprawling outwards. We don’t really have a means of measuring whether sprawl is increasing or decreasing. And many, many private non-governmental organizations have policies and programs to try to prevent sprawl, but we don’t really have a mechanism to understand whether we’re slowing it or stopping it or whether it’s continuing to increase.

CURWOOD: Ok, here’s the big question. Why don’t we have this data?

O’MALLEY: Well, we simply haven’t organized ourselves and set priorities to collect these data. And that’s one of the things this report is intended to do, is from the hundreds or thousands of different kinds of things that one could monitor and report, we need to select a set of important indicators, important bits of information about the way that the natural world is functioning and go about reporting these things. And this is the first time that we’ve been able to set that kind of priority and select from those hundreds and thousands of things and pick just about a hundred things for the entire country.

CURWOOD: Now, a number of the folks who came to the table with you on this have varying political and environmental and social interests. What were some of the more difficult conversations that happened around the table?

O’MALLEY: There were some very difficult discussions over how to measure some contentious and controversial issues. Forest fragmentation is an issue of extreme importance. If forests are broken up into small fragments, they often serve as less useful wildlife habitat. And exactly how to measure that fragmentation is something that the technical community doesn’t agree on, the environmental community doesn’t always agree with the business community. And I think that was the single most controversial issue that we faced and I would say we made important progress on how to measure forest fragmentation but that there’s much more work to be done.

CURWOOD: How can people use the information that you’ve generated in this report? How should they use this information?

O’MALLEY: People in national policy-making positions are asked to vote on things, asked to approve policies or regulatory changes and this provides a grounding in fact. There are lots of claims in a city like Washington of what’s actually going on out there on the ground. Sometimes those claims are correct, sometimes they’re not. This will provide a grounding for policy makers and people who are involved in these decisions to really check those claims against the reality.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking this time. Robin O’Malley is a senior fellow and project director for the Heinz Center report on the state of the nation’s ecosystems. Thanks for speaking with me today.

O’MALLEY: Thank you very much.

Conservation Cows

CURWOOD: A unique experiment is underway just south of San Francisco. Conservationists and cows are teaming up to restore native California grassland, a once common ecosystem that is now found on only about one percent of the land there. Sandy Hausman reports.

[COW CALLS]

HAUSMAN: Rudy Driscoll, Jr. is on the job, driving the steep, rutted roads of his family’s 4,000 acre ranch to check on nearly 600 cows and calves, identifying the animals by colorful tags in their ears.

DRISCOLL: The orange tags are all mothers. The yellow tag in the back is a bull. And the blue tags are steers.

HAUSMAN: The herd roams freely on these rocky green hills. They seem content here. And their owner couldn’t be happier.

DRISCOLL: I often brag that I have the best office in the country because, from the center of my office up here, it’s two and a half miles to the nearest neighbor.

HAUSMAN: Unfortunately, Driscoll says, that situation could change as people move south from San Francisco and north from San Jose. The ranch is midway between those cities, just a few miles from the coast. And the value of the property keeps rising. Rudy and his father wanted to preserve the land. But from a business standpoint, the temptation to sell was strong. Grazing cattle on this prime suburban real estate didn’t make financial sense.

So the two started talking with the Peninsula Open Space Trust, a local group committed to saving the natural beauty of the area. After Rudy Driscoll, Sr. died last year, Rudy, Jr. reached an agreement with the Trust.

DRISCOLL: I wanted to keep the cattle. They wanted to preserve the property. And we thought we had a way of being able to have both goals met.

HAUSMAN: Here’s how the deal will work. Driscoll will sell most of the ranch to the Trust, keeping 300 acres for his family and retaining the right to graze his cattle on the rest of the property. The Trust will then reestablish coastal grasslands, displaced by farming and by non-native plants that do a poor job of holding soil. Paul Ringgold is director of stewardship for the Peninsula Open Space Trust.

RINGGOLD: What we’d like to do is return these to native grasslands that did exist in this area back when the areas were burned by the Native Americans and even prior to that time. Those kinds of grasses are perennial grasses, which exist year-round and form a much more dense root mat that is a soil stabilizer.

HAUSMAN: Restoration of this kind would typically involve burning the existing grass, and sowing the seeds of native plants. But Trust president Audrey Rust says that isn’t practical.

RUST: Today, we are so close to a developed area. And standing right here where we are on the middle of this property, I can see an elementary school. I could look across the valley at some houses. You really can’t use fire in quite the same way. It’s not as practical a tool here.

HAUSMAN: So they’ll put Driscoll’s cows to work, rotating them through a dozen fenced pastures where they’ll nibble the grass down to its roots. Paul Ringgold says that will make way for the seeds of native plants to sprout.

RINGGOLD: Once we have gone in and seeded these areas, the cattle can help, first of all, stamp the seed down into the soil so that it’s not picked off by birds. They can also then keep non-native grasses down long enough for the native grasses to come back in.

HAUSMAN: And finally, the cattle will provide natural fertilizer for the new plants that will, in turn, nourish the cattle. It’s an ironic role for the animals that are often blamed for environmental problems. Overgrazing has decimated land in many parts of the country, turning prairies into deserts, and causing erosion that has killed countless streams and rivers.

In spite of that, Rudy Driscoll feels cattle have gotten a bad rap. He hopes this experiment will show that, if properly managed, cattle ranches can help improve water quality and provide better habitat for native wildlife, something Driscoll has in abundance.

DRISCOLL: Obviously, today we’ve seen deer and there are the coyotes, rabbits, a lot of bobcats. I’ve seen a couple of eagles out here.

HAUSMAN: There are even some endangered species on the ranch, the San Francisco garter snake and the red-legged frog. Their odds for survival will improve once the native grasses begin to attract certain insects.

Conservationists concede this unusual collaboration with a rancher and his cows will have limited impact. But they hope their work on the Driscoll spread will become a model for other ranchers. For Living on Earth, I’m Sandy Hausman, in La Honda, California.

[COWS MOOING]

Health Note/Curry Consumption

CURWOOD: Coming up: precision farmers and treasure hunters alike tap into the Global Positioning System. First, this environmental health note from Diane Toomey.

TOOMEY: There’s evidence to suggest that anti-inflammatories such as ibuprofen may help protect against Alzheimer’s disease since they reduce brain inflammation. But excessive use of these substances can cause intestinal, liver, and kidney damage.

Now a study suggests there might be an alternative. India has one of the lowest rates of Alzheimer’s disease. It also has one of the highest rates of curry consumption. Turmeric is an important ingredient in curry and turmeric contains curcumin, a well-known antioxidant and anti-inflammatory herb.

So using mice specially bred to develop Alzheimer’s, researchers at UCLA fed one group a normal diet. Another group of mice received the same diet, but with a low dose of curcumin added. After six months, brain biopsies showed the curcumin-eating mice had less inflammation compared to mice that didn’t eat the spice. These mice also had less oxidative damage to brain cells and produced smaller amounts of a protein associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

Researchers caution that while the study is promising, there’s no research to suggest that curcumin would have similar effects in humans. That’s this week’s Health Note. I’m Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Chet Atkins, "Windy and Warm" (acoustic)]

Related link:

Journal of Neuroscience abstract

Almanac/Warm Winter Wind

CURWOOD: Welcome Back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Sixty years ago this month, residents of the town of Spearfish, South Dakota woke up to a thermal surprise. In just two minutes the temperature in Spearfish rocketed up 49 degrees. At seven-thirty in the morning of January 22, 1943 it was a bitterly cold minus four degrees. But by 7:32 it had jumped to a relatively balmy 45. The phenomenon is still in the record books as the fastest temperature change ever recorded.

Now for the why. Science points to the Chinook Wind. “Chinook” means “snow eater” in the language of some Native Americans, and this warm, dry wind certainly does eat up snow cover. Chinooks happen when warm air pours down a mountainside. In Spearfish, the dramatic Chinook came up over the Black Hills. Unique air currents caused wind from one side of the hills to heat up drastically as it descended into the cold air mass on the other side.

Despite respite from the cold, Chinook winds can create problems. The hot, dry air has been known to start wild fires and damage plants. Similar winds in the Alps have caused deadly avalanches. And the Chinooks can be cruelly unpredictable.

In Spearfish in 1943, the pleasant weather lasted only an hour, before the temperature dropped back to minus five degrees in less than 30 minutes. Car windshields cracked, and cattle and people alike were stunned, as the season seemed to change from winter to spring and back again, all before lunch. And for this week, that's the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC ENDS]

Precision Agriculture

CURWOOD: There was a time when winter on the farm meant equipment tune-ups, cleaning the house, and spending time with the family. But a growing number of farmers are whiling away winter in front of computer screens, accessing the Global Positioning System. That’s the extensive satellite navigation network that was originally created to help the military track enemy troop and missile movements. Now GPS and something called "precision agriculture" are taking more of the guesswork out of growing some crops. Minnesota Public Radio's Jeff Horwich reports.

HORWICH: Chris Dunsmore is a serious farmer, a serious farmer who spends 20 hours a week playing on the computer.

DUNSMORE: Anything that's got a cord on it, I love. And that's part of the reason I spend a lot of time working here. Because I enjoy doing it. I enjoy working with software and computers. It's a daily challenge.

HORWICH: So, you're kind of a technology junkie, in any case.

DUNSMORE: Pretty much so. Yup.

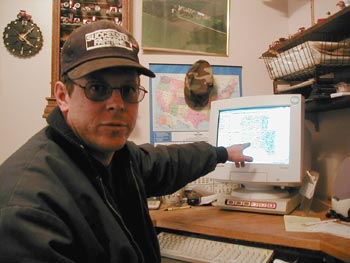

Chris Dunsmore uses his computer, and the global positioning system, to plan how to use his land.

(Photo: Jeff Horwich)

HORWICH: Dunsmore's PC shares a sunny room in the farmhouse with the washer and dryer. On the screen, he pulls up the irregular outlines of a farm field, covered with tiny neon dots.

DUNSMORE: On this field here of about 110 acres, we have 16,000 data points to work with within that one field.

HORWICH: What's a corn farmer doing with 16,000 data points? During the harvest, Dunsmore's combine took a measurement every three seconds of how much corn it was bringing in. An antenna on top of the cab linked up with the Global Positioning System satellite to record the exact position of the combine on earth at each moment. Put it all together, and you get 16,000 readings, fading from red to yellow to blue on a computer screen, telling you how well your corn did at any given spot.

DUNSMORE: You can see here, the lower yielding areas of the field. These here, we already know that there are drainage concerns.

HORWICH: Dunsmore and three other farmers jointly farm 3,500 acres in central Minnesota. Modern farm equipment and GPS readings break their land down for them into hundreds of thousands of smaller units, hence the term "precision farming." Put simply, the patterns revealed by the tiny units lead to much more specific prescriptions. For seeds, for fertilizer, for drainage, it's more efficient and, arguably, better for the planet.

ROBERT: We like to say that we do the right thing, at the right place, the right way.

HORWICH: University of Minnesota professor Pierre Robert was there in 1982 when some local soil sample data was plugged in to one of the first IBM PCs on campus. Robert considers that day, in St. Paul, the world's first glimpse of precision ag.

ROBERT: The Midwest is where the concept started years ago. But it is also the area where the precision agriculture is certainly well adopted. There are areas in specialty crops, like sugar beets in Northwest Minnesota, where we have about 40 percent of the farmers using some aspect of the concept.

HORWICH: Precision ag spread gradually as equipment prices came down and technology allowed farmers and researchers to become more precise. With more mainstream crops like corn and soybeans, Robert guesses ten percent of Minnesota farmers are using it. Individual farmers may be looking at their bottom line. But researchers, like Robert, are also excited about potential environmental benefits. Farmers confronted with computer maps of their fields are finding many places where they can cutback dramatically on fertilizer and other chemicals.

ROBERT: In a previous project, we strongly could show that we are capable of reducing by at least 50 percent the use of herbicides. And of course, that has a strong potential to reduce excess into surface water.

HORWICH: By now, the first wave of enthusiastic, progressive farmers like Chris Dunsmore, have mostly come onboard. But current commodity prices are discouraging the next wave of farmers from making an expensive investment in new technology. It costs around $9,000 for the basic GPS receiver, crop yield monitor, and software it takes to get started in precision farming.

Chris Dunsmore shows his tractor’s GPS system.

(Photo: Jeff Horwich)

[SOUND OF TRACTOR STARTING, BEEPING]

HORWICH: Dunsmore climbs up into his tractor to show off some of his newest equipment. It's a yield monitor for his sugar beet harvester, installed last year. When he fires up the tractor, a screen near the roof of the cab glows a phosphorescent blue. He punches a few buttons on it to walk through some common operations.

At harvest time, it measures how much he's pulling up and how much moisture is in the crops. It's a critical piece of the puzzle that shows what's working, what's not, and where money's being wasted. For years, Dunsmore had been raising varieties of corn and soybeans he thought were doing well. But a detailed look at the numbers showed they just weren't performing in certain fields.

So far, the biggest savings of all have come from cutting back on fertilizer where he doesn't need it. He estimates he's saving five dollars per acre each year because of precision farming. At 3,500 acres, that's more than $17,000 – nothing to sneeze at. Still, Dunsmore says farming in the information age is both a blessing and a curse.

DUNSMORE: We've got just oodles of information. That's one of the biggest problems we have now is we're getting so much information that we're having a hard time breaking it down.

HORWICH: Information overload might be the biggest of Chris Dunsmore's worries. But precision farming may accelerate some much more intractable issues facing American agriculture as a whole. For one thing, economies of scale and the cost of new technologies make precision ag accessible mostly to large farms, which then only increase their competitive advantage. Even Dunsmore teamed up with three neighbors to make it pay off. And some say America's farmers are too efficient already, producing more food than the world is willing to pay for and keeping commodity prices perpetually low. This frustrating paradox of efficiency is one problem precision farming may only make worse. For Living on Earth, I'm Jeff Horwich in central Minnesota.

High Tech Booty Hunt

CURWOOD: When President Bill Clinton declassified the global positioning system people expected folks like farmers, environmental monitors and mapmakers to take advantage of the technology. Yet, none of these applications seem as creative, or delightfully frivolous, as geocaching – a new treasure hunting sport that uses the computer, the World Wide Web, and GPS. As Ken Shulman reports, geocaching is catching on all over.

[SOUND OF HIKING]

XANATOS: We're right on top of it now. It's probably in here some place.

SHULMAN: Here, at the foot of Mt. Tom in central West Massachusetts, the mercury cowers just below the 15 degree Fahrenheit mark. There must be something very valuable, very precious, to lure us out onto the slippery, ice-crusted snow, three miles off the nearest road. The arrow on Dave Xanatos' handheld GPS device points due north. The numbers on the display tell us that we're close.

XANATOS: Wait, wait a second. I found it. I got it, it's right here.

SHULMAN: Found what? Xanatos tugs a green metal ammunition box out of its hiding place and sets in on a rotted birch log. The self-employed web designer undoes the latch and opens it.

XANATOS: Ah, a spine key chain. From Family Chiropractic. Dr. Michael Gleil... Aluminum shafts, no doubt for darts, I guess, or something like that. A yo-yo. A little, some sort of poke the thing game. An AOL disc. That can't really be an AOL disc. Oh how cheap. Someone put an AOL disc in here. That's bad!

[QUIET SOUNDS OF TALKING IN BACKGROUND]

SHULMAN: One week after President Clinton lifted the GPS ban, a GPS enthusiast in Oregon placed a slingshot, a can of beans, and some software in a five gallon plastic bucket, hid the stash, and posted the GPS coordinates on the web. And geocaching was born. There are almost 13,000 caches posted in 107 countries. There are caches on the side of a dormant volcano in southern Russia and others in undersea grottoes. Websites like www.geocaching.com offer listings, along with cache descriptions, photographs, and clues for novice hunters.

XANATOS: I'm going, at this point, to put everything back in.

SHULMAN: Xanatos signs our names in the logbook and takes our photographs with the disposable camera. He takes the spine key chain, and leaves a Hot Wheels race car and some of his business cards as barter. He hasn't gotten any clients this way, he says, but hey, you never know.

[SOUNDS OF PUTTING BOX BACK]

XANATOS: So now, I'm putting it back right where it was and I will camouflage it effectively.

SHULMAN: Then he conscientiously returns the box to its hiding place for future geocachers to find. Geocaching is, in his own words, one of the best things to happen to geeks in a while, because it gets them out into nature.

[SOUND OF HIKING]

XANATOS: I mean look at this, we've been battling the ice and it's cold and we have beautiful trees and sunlight all around us and everything. No computers in sight really to speak of.

SHULMAN: Isn't there one in your pocket?

XANATOS: Yeah, but that doesn't count. It's not on right now. [Laughing]

[SOUND OF CHILDREN]

SHULMAN: Geocaching doesn't just bring out the kid in adults. It also brings out the kids.

[SOUNDS OF CHILDREN]

SHULMAN: These cub scouts, troop 702 from Reading, Massachusetts, are on their first geocache hunt. The terrain is a gentle hill two hundred feet above the parking lot at Hogue Pond in nearby Winchester. It doesn't sound like much of an adventure. Yet there is something magical, says Adena Schutzberg, one of the supervising adults.

SCHUTZBERG: Well I think the best thing for me, I'm trained as a geographer, is it takes me to places I otherwise wouldn't go. Sort of an excuse to get out and find a new place that somebody else has decided is somehow is significant or important to them. So it's a great way to see your local area. I grew up about two miles from here and I've never been here in my life so there you go. That's the perfect example.

CHILD: Oh a calculator, excuse me, excuse me, a beach ball, yeah.

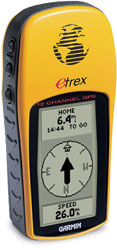

SHULMAN: It appears that most school-age geocachers do it for the trinkets, while most grown up geocachers get their kicks from using their high tech toys, toys that are surprisingly affordable and easy to use.

[SOUND OF CHILDREN]

SHULMAN: A hand held GPS device costs as little as $100 and can be mastered in about five minutes. Bob Hogan is an engineer, and one of the first geocachers in Massachusetts. He's the leader on this cub scout outing. One thing geocachers of all ages have in common, he says, is that they expect, and usually get, a very quick fix.

(Photo: ©Garmin Corp. 2001)

[SOUND OF CHILDREN]

HOGAN: Most of society still requires semi instant gratification. And if you can't get people to a cache, the majority of the people, within forty-five minutes to an hour, chances are they may not want to go out and do it.

CHILD: See we got a calculator. Now daddy has a new one and so do I.

SHULMAN: While geocachers will undoubtedly benefit from even twenty minutes in the woods, there are those who worry about the impact this low key hi-tech odyssey might have on public lands and parks. Tom Casey is head of law enforcement at Minuteman National Park in Concord. The park includes important sites and artifacts from the American Revolution. Casey recently discovered, through an internet search, that at least one geocache has been set in his park. And he's concerned about the consequences.

CASEY: We have rock walls that have been here since 1775 and in some instances they could have been used by the local militia to fire at the Brits, and if someone removes rocks to hide a container inside a rock wall or to build a cairn as a marker for where it might be, all those items could drastically change the complexion of the park..

SHULMAN: At present, geocaching is illegal in national parks. Casey does concede that specific national parks, and specific park superintendents, might eventually issue permits to allow limited supervised geocaching if the demand should grow. And it well may.

[SOUND OF HIKING]

SHULMAN: Geocaching is easy, it's fun, and can be done at all levels of ability and age. Like the worldwide web, it creates a mysterious, benign connection among people who may never meet, but who share in the experience of a special place. And of a special time, a time of memory, when finding a chest that someone has stocked with treasures and hidden for us to seek was all that really mattered in the world.

HOGAN: We're in business, boys.

SHULMAN: For Living on Earth, I'm Ken Shulman, in Winchester, Massachusetts.

HOGAN: There it is. Yeehaw. All righty, let's see what he wrote here. One of those little Chinese checkers type games, some fishing lures, more golf balls. Top Flight...

Related link:

Geocaching site

Ecological Indicators

CURWOOD: You’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. Stock prices, inflation rates and unemployment figures are part and parcel of most daily newscasts, but commentator Terry Link says maybe it's time for similar reports about environmental indicators.

LINK: Some economists like to toss around the saying that you are what you measure, so by that standard, how do we appear? Look at what the media tell us.

[NEWSCAST MUSIC]

NEWSCASTER: The Dow Jones tumbled 170 points on heavy trading of more than….

SECOND NEWSCASTER: Consumer confidence is lagging, dropping 0.2 percent from last….

FIRST NEWSCASTER: Wholesale prices rose 2.3 percent for the month, hinting that demand for products may once again signal….

LINK: You get the picture. Given the standard, then, that you are what you measure, it should be no surprise that we have become, simply, Homo economus. By constantly trying to measure wealth by GNP and stock prices, we tend to idolize consumption while we devalue much of what gives life its true meaning, namely, our connections to each other and with the marvelous and mysterious spinning sphere that provides us with life. So I believe it's way past time to give us equivalent daily reports on the health of our biosphere.

Why not report on the spread or decline of disease in humans, animals, and plants? Or give regular updates on receding glaciers, severity of storms, or increased ridership on mass transit and its effect on reducing pollution. A daily report might sound like this:

[NEWSCAST MUSIC]

NEWSCASTER: Energy consumption was up briskly in December, but the percentage of power generated from renewable resources climbed 25 percent faster than the overall increase. This has resulted in an overall drop in greenhouse gas emissions, despite the rise in overall consumption.

LINK: And how about we start reporting not only raw agricultural statistics but also the implications of those numbers:

NEWSCASTER: Michigan saw its consumption of locally produce lettuce climb by 19 percent from last year. More effective marketing of locally grown food brought a welcome boost to the state economy. Along with the advantage of increased freshness for lettuce consumers, the diminished transportation needs of locally produced food led to a reduction in air pollution, traffic congestion, and noise.

LINK: We must understand that the condition of our air, land and water is just as, if not more, important than fluctuations in our stock portfolios. Making environmental information more prominent and regularly available, as we do with stock prices and economic reports, is a step towards crucial mindfulness. We might even copy a Wall Street business reporting model and highlight a socially and environmentally responsible firm or organization that is developing products, services or processes that help build more sustainable communities.

We need to nourish the entrepreneurial spirit towards community solutions, and we need the mass media to give more of its news hole to report daily on the indicators of total community health, not simply the sterile financial numbers. If we were to give, at least, equal play to our natural world, we might just create a future where we all flourish.

CURWOOD: Terry Link is a librarian at Michigan State University and comes to us via the Great Lakes Radio Consortium.

Animal Note/Frenzied Ants

CURWOOD: Just ahead: Little oil drips add up in the ocean. First, this page from the Animal Notebook with Maggie Villiger.

VILLIGER: There’s more clandestine behavior inside the nest of Myrmica schencki red ants than at a spy convention. The first level of intrigue: Caterpillars of the Maculinea rubeli butterfly emit a pheromone that tricks ants into thinking they are ant larvae. The cuckolded ants cart the larvae home and adopt them as their own.

But the caterpillars aren’t home free. A particular parasitic wasp can only lay its eggs in the caterpillars’ bodies. And it knows how to make it past the ants’ line of defense. Its weapon of choice: chemical warfare.

Scientists have discovered that the wasp is covered in a kind of oily wax made up of six chemicals that cause ant behavior to go haywire. The chemical cocktail attracts ants to investigate the intruder, then repels them and makes them start fighting with each other. The nest starts to look like a barroom, with brawling ants biting each other and pulling on legs.

All this misdirected mayhem allows the wasp to move unnoticed through the nest ‘til she reaches her target, the caterpillar. The wasp lays her eggs, and then sneaks out again while the ants are still distracted.

The researchers suggest that these newly discovered wasp chemicals could eventually lead to a new kind of long-lasting pesticide. That’s this week’s Animal Note. I’m Maggie Villiger.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC]

Oil in the Sea

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Coming up: Neither snow nor sleet keeps our snowplowing poet from his appointed rounds. But first: Think of oil in the oceans these days, and images of shipwrecked tankers like the one off the coast of Spain probably jump to mind. A recent report put out by the National Academy of Sciences says that some 29 million gallons of petroleum enter North American ocean waters every year as a result of human activity. But the sheer volume of oil is only part of the story. Much of the Academy report tells us where the oil comes from, and what happens to it when it gets into the ocean. Living on Earth’s Anna Solomon-Greenbaum has details.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: The results of the Academy’s research may surprise the average person who probably thinks "Exxon Valdez" when the words "oil" and "ocean" are mixed. The report finds tanker spills and pipeline leaks are responsible for less than 10 percent of the oil released by humans into the oceans each year. Most of the oil, 85 percent of it, comes from seemingly minor sources, like your uncle’s outboard motor, the oil that drips from your car, or the fuel that’s dumped by airlines. In the past, the impact of these various sources has been hard to measure, and not nearly as dramatic as blackened shorelines and dead birds left by a major oil spill. Dan Walker, staff scientist on the Academy report, says the little spills are more significant than imagined.

WALKER: We’re talking about a few ounces each year that each one of us accidentally release. But there’s a lot of us, and it tends to accumulate. And what we’re seeing is, is that, in many cases, there seems to be a clear-cut relationship between these low concentrations of some of these toxic compounds, and adverse effects on marine organisms.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Walker says oil companies have dramatically reduced the amount of oil spilled from tankers, wells and pipelines. And the industry says their operations are safer than ever before. But environmental groups warn vigilance is still needed.

SPEER: How much oil is only one part of the equation.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Lisa Speer is a senior policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council. The Academy’s report, she points out, finds even a small spill can have a big impact if it ends up in a sensitive ecosystem. Speer says land runoff is the number one source of coastal pollution in America, and she’s glad to see it getting more attention.

SPEER: But that doesn’t mean that we can ignore the threats posed by offshore oil and gas development and transportation in sensitive areas. We need to do these things together. And we need to keep working towards reducing pollutants that get into our oceans, both through land-based runoff, as well as through major oil spills.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Both land-based runoff and oil spills at sea are dwarfed by a third source of oil in the oceans, natural seeps from the seabed. Their impact is unique, according to Dan Walker, because organisms living near these seeps have, for the most part, adapted to the toxic compounds that petroleum unleashes in their ecosystem. Still, Walker says, natural seeps can make good study sites for scientists trying to understand the slow, subtle effects of oil from land-based runoff.

WALKER: That gives us a little bit of a idea of how the introduction of large amounts of petroleum, a little bit at a time, small dribs and drabs, but everyday, over the course of many, many years, how that can effect an ecosystem.

SOLOMON-GREENBAUM: Policymakers have been exploring ways to control runoff. So far, most of their effort has focused on nutrient runoff from pesticides and waste. The Academy’s report may raise the profile of petroleum runoff as another part of the problem. For Living on Earth, I’m Anna Solomon-Greenbaum in Washington.

[MUSIC]

The Grid & the Village

CURWOOD: For people in northern New England, New York, and eastern Canada, the ice storm of 1998 is still a vivid memory. Pounding rain and frigid temperatures created conditions that cut off communications and shut off electric power for days, in some cases weeks, in many places along the northern tier. One such community was Stephen Doheny-Farina's hometown, Potsdam, New York. Welcome sir!

DOHENY-FARINA: Thank you.

CURWOOD: The cover of your book is certainly something else. Can you tell us about it, please?

DOHENY-FARINA: Well, it's a photo taken at some point during the disaster, the ice storm of 1998. And what we're looking at is, oh, in this picture, three completely crumpled, huge power distribution towers, the kinds of things you see in the distance, hundreds of feet high. And we can see two gentlemen standing in front of a row of crumpled towers. You look at this and you know that something is seriously wrong.

CURWOOD: Suddenly those towers look like a child's erector set, and that somebody has sat on them.

DOHENY-FARINA: Yeah, it's amazing. This was ice that did this, and yet they seem so fragile when you look at the picture. You know, so strong when you look across the horizon and see them, and so fragile when something as simple as ice coated them.

CURWOOD: Okay. So let's go back now to January of 1998. The ice storm was bigger than anyone had expected. But how was it so devastating? What happened?

DOHENY-FARINA: Well, it all happened very slowly, and it just started raining. A huge storm came up the eastern seaboard. But what happened was there was cold air that just wouldn't budge, and it was this large tongue of cold air that cut across eastern Canada and into northern New England and northern New York. And for five days it rained. In the end, I think we're talking about roughly four inches of ice coating everything, a little more in some places.

CURWOOD: What was it like to be in this storm? How did you know that it was more serious than your average winter squall?

DOHENY-FARINA: Well, that was just the thing. No one knew that. I'll tell you the moment. The moment when suddenly something seemed more serious was when I woke up, my wife woke up, saying, "Ah, there's no power. Huh. It should be on soon. We'll just have to sit tight here. Let me turn the radio on. Let's hear what the status is." And there are no radio stations. I mean, nothing, not a sound, up and down the dial. And this just doesn't happen. And the power always comes back on. Well, it just didn't come back on. For, I think, at least a day or two, many of us figured, "Well, the power will just be back on soon," because we were suddenly so isolated. So it was a gradual – but there were moments when suddenly we thought maybe this was bigger than we realized.

CURWOOD: Radio – what was the role of radio in all of this?

DOHENY-FARINA: It was kind of an interesting combination of commercial and public. The commercial stations sort of became more like public stations. They rarely ran any ads, and when they did they just seemed strangely – they would apologize on air. "Sorry, we have to run this ad." But they just seemed totally out of place, and they didn't do much of it.

The public stations, they were doing commercial things. Like, you know, after a few days, you know, "There's a load of kerosene arriving at so and so station," you know. In other words, they were promoting things to buy in the community. And it was this kind of middle ground that had developed. They ended up sort of telling the story, and it was our story. People were calling in and telling what's happening, and that was one of the main sources of news, was people in the community calling the station and reporting. It was intensely local, and in a way that just doesn't happen in any other situation.

CURWOOD: The title of your book is “The Grid and the Village,” and I'm wondering, when did your small town become a village during this disaster, and what's the difference?

DOHENY-FARINA: Well, I have to say that I think if you asked people before the ice storm, you know, "What's the status of the community here," you know? “Are people interdependent?” Well, oh, you know, somewhat. But no more than anywhere else. We can pretty much live without knowing our neighbors. I mean, that's the common status of the nation. But the ice storm really revealed to us a vibrant network of community ties that I think most people had thought maybe had withered away over time. But it was still there. And it was energized as the power grid became de-energized.

CURWOOD: Share with us the image that sticks with you from this ice storm.

DOHENY-FARINA: Well, one indelible image was the night that my family and my neighbors and I, after a number of days, made it to a shelter to eat. And I had this moment, sitting in this large cafeteria-like area, and looking around, and everyone was talking with everyone else, whether you knew them or not. We were all bound by the same absolute necessity, and all pretense of individuality was lost. There was just constant conversation: "How are you doing?" "What do you have?" "How are you surviving?" "Where are you?" "Have you heard anything?" "Do you know anything?" "What's happening out there?" It was a very powerful moment for me.

CURWOOD: Once the storm had passed and the power was back on, one of the women you chronicle in your book, you quote as saying, "I wish I could do it again, because now I've got a dress rehearsal." What do you think she meant by this?

DOHENY-FARINA: Well, you know, that points to the real conflict in this whole thing. I was so unsettled afterwards, you know. At one point, I write about a couple days after I had power. And, you know, now I have to go back to my pre-storm life. And I was tremendously let down by that in a strange way. I didn't want to live without power, but why was I so unsettled? This happened with person after person. The power went out suddenly – and it was only for a brief time – but suddenly I was energized again. You know, "Wow. Let me get a hold of my neighbors again."

People – the woman you referred to and others – they had this tremendous sense of purpose, and they felt tremendously tied to people around them, and now they didn't. And while you don't want to live in a 40 degree house without a bathroom and lights, something was lost when the power came back on that was very powerful during it.

CURWOOD: Stephen Doheny-Farina is a professor at Clarkson University in Potsdam, New York, and author of the book, “The Grid and the Village: Losing Electricity, Finding Community, Surviving Disaster.” Thanks so much for talking with me today.

DOHENY-FARINA: Thank you very much for having me.

Related link:

“The Grid and the Village,” published by Yale Books

Ode to a Snow Plower

CURWOOD: Even normal wintry weather can be a challenge to deal with. And in places where it snows – and piles up – the white stuff can put a real damper on daily life. Which causes us to ask when was the last time you honored your snowplow driver? Robin White visited the town of Allegheny, California and met the man who keeps its 145 residents connected to the outside world.

NEWSCASTER 1: Snow level dropping to around 3,000 feet this afternoon.

NEWSCASTER 2: Chains and snow tires are required this morning on I-80 over Donner Summit, on 50 over Echo Summit--

[SOUND OF DRIVING]

NEWSCASTER 3: A winter storm warning is in effect through tomorrow for much of the Sierra, including the Lake Tahoe region, where forecasters predict more than two feet of new snow could fall.

WHITE: "It's very misty outside. It's like some primordial forest out of a fairy-story." That's me, driving into the town of Allegheny, looking for Jim Buckbee, who's the keeper of the mountain roads here. Allegheny's a little gold-mining town, home of the oldest hard rock gold mine still operating in the United States. It's a ramshackle collection of houses and rusty old cars in a snowy landscape stuck on the side of a deep canyon. The road into town goes over a ridge 5,200 feet high. Jim Buckbee is a man with a belly and a twinkle in his eye, and he's the one who keeps it open.

[SOUNDS OF MACHINERY]

WHITE : That's a mighty fine snowplow you have there. Nice to meet you.

BUCKBEE: Nice to meet you.

WHITE: How are you doing?

BUCKBEE: Good.

WHITE: So hey, here we are. This is fun. Is there a seatbelt there somewhere?

[SNOWPLOW DRIVING OFF]

BUCKBEE: You can look off in the canyon off of the side there, and it's pretty much straight down.

WHITE: You're telling me! Wow.

[LAUGHTER]

BUCKBEE: So when we have a warm spell like this, our berms all get melted away. This is when you really have to be careful. Cause we're plowing right on the edge of the road, and there's only about three feet of good, solid ground before it gets soft, and it can just pull you right on over.

[GETTING OUT OF PLOW, SOUND OF WALKING IN BACKGROUND]

BUCKBEE: Watch your step going down. When you're out there plowing snow there's certain things that you see constantly. And so they just start digging into your soul, you know? And when I wrote the poem, we were discussing all the different counties and how they do their snow removal. And the biggest thing is when you're working a day shift and then you switch to a night shift without any sleep. So the whole thing is geared towards surviving another night, and it just started clicking. I just started writing, and it was like, "Wow. Hey, that sounds pretty good."

[VOICES ON SCANNER RADIO]

BUCKBEE: One night I was just really bored and I was doing a back-to-back shift. It was snowing really hard and so I recited it over a radio. All of a sudden they had all these requests coming in from different areas that had picked it up on their scanners, wanting to know where it came from and if they could get a copy of it. So I started sending these people copies of my poem.

[READ OVER SCANNER RADIO]

"Another night" By Jim Buckbee.

When the snow flakes fly and the wind blows so cold,It's the sound of steel that curls my toes.It's a long night ahead, and that's my foe.As I drop my plow and head down the roadI only pray that my lights will be bright.As the snow flakes danceI strain at the sight,But my chains bite deep into the iceAnd I look for that guiding lightThat makes everything all right.The snow piles high,But that's all right,Because I'll just hit itWith all my mightAnd shove it over to the right.The sky finally lightensAnd I know it's all right,Because I just made it throughAnother night."

BUCKBEE: Just a small little town way up at the end of a road. What an office, huh? [Laughs]

CURWOOD: Our feature on Jim Buckbee, the snowplow guy, was produced by Robin White. Thanks to Duncan Lively and Duncan Howitt at KXJZ in Sacramento.

[MUSIC: Greg Brown, "Rexroth's Daughter," Covenant (Red House Records - 2000)]

[WOLFCALLS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with the haunting sound of wolf calls in the night.

Jonathon Storm got up close to eavesdrop on this wolf pack reclaiming its home turf in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

[EARTHEAR]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at www.loe.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Cynthia Graber, and Jennifer Chu, along with Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson, Jessica Penney and Liz Lempert.

Maggie Villiger produced this week’s program with help from Andrew Strickler and Nicole Giese. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. Alison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor, Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor, and Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth.

I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation for coverage of Western issues, the National Science Foundation supporting environmental education, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth’s expanded internet service, the Educational Foundation of America for coverage of energy and climate change, the Ford Foundation for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, the David and Lucille Packard Foundation for reporting on marine issues, the W. Alton Jones Foundation, supporting efforts to sustain human wellbeing through biological diversity www.wajones.org, the Oak Foundation, the Town Creek Foundation, and the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth