May 2, 2003

Air Date: May 2, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The High Price of Colombia’s Drug Trade

/ Angela SwaffordView the page for this story

In the second installment of our two-part series on the Colombian environment, we look at how that nation’s 40-year-old Civil War and drug trade have taken its toll on the natural world. Angela Swafford reports from Colombia’s Amazon forest. (11:00)

Environmental Health Note/Chemical Sensitivities

/ Diane ToomeyView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Diane Toomey reports on a new study that looks at the incidence of Multiple Chemical Sensitivity syndrome. (01:15)

Effects of Coca Spraying

View the page for this story

The U.S. funded effort to destroy coca crops comes with some unanswered environmental questions. Host Steve Curwood talks with St. Petersburg Times correspondent David Adams about concerns over an untested chemical mixture being sprayed in Colombia. (10:00)

Letters

View the page for this story

This week, we dip into our mailbag to hear what listeners have to say. ()

The Fish That Changed the World

/ Mark KurlanksyView the page for this story

The Canadian Parliament recently banned all commercial and recreational fishing off the shores of the Atlantic provinces and Quebec. Mark Kurlanksy, author of "Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World," says that life in the fishing town of Newfoundland will be changed forever. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note/Sequencing Sargasso

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports on plans to map the genome of every organism in the Sargasso Sea. (01:15)

Leafy Toxins

View the page for this story

There’s been growing evidence that perchlorate, a main component of rocket fuel, may be concentrating in drinking water and lettuce. Meanwhile, the Bush administration has issued a gag order to keep EPA scientists from talking about their perchlorate research. Host Steve Curwood talks with Wall Street Journal reporter Peter Waldman, who has been following the story. (06:30)

Debate Over Farmed Salmon Grows

/ Don GenovaView the page for this story

Don Genova reports the controversy over salmon raised in ocean pens in British Columbia has grown beyond environmentalists and Native tribes to researchers and, now, consumers. Restaurants are changing their menus and the debate is spreading south into the United States. (09:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: David Adams, Peter WaldmanREPORTERS: Angela Swaford, Don GenovaCOMMENTARIES: Mark KurlanskyNOTES: Diane Toomey, Cynthia Graber

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

In the war against the illegal drug trade, a U.S. funded defoliation campaign is turning the green forest of Colombia brown. This anti-drug program may be yielding results, as coca production is reported to be on the decline. But farmers, and others in the region, say the spraying is taking place without proper safeguards for the environment and public health.

ADAMS: This kind of spraying would be impossible under U.S. legislation if it was being conducted in the United States. Because it's Colombia, the United States doesn't have to worry about its own legislation. That's up to the Colombian government. But, obviously, we all know that the Colombian government is under a good deal of pressure from the United States to adopt these programs, and to make them work.

CURWOOD: Colombia, the environment, and the war on drugs--this week, on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and heritageafrica.com.

The High Price of Colombia’s Drug Trade

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Colombia is a country rich in bio-diversity. No other nation can claim more species of birds and amphibians. And it is abundant with flowering plants. But, 40 years of civil war in Colombia, and the related drug trade, have taken a toll on its natural world. The government says two and a half million acres of forest have been cut down in the last decade alone to make room for coca, and lately, for poppy--the source of heroin.

Add to that the damage done by the chemicals used to grow and process these crops. In the final installment of our series on Colombia and the environment, Angela Swafford traveled deep into rebel-held territory in the Amazonian forest of Colombia.

[AIRPLANES, CHOPPER SOUNDS]

SWAFFORD: The air is moist and warm on this early morning at the airport in Florencia, a small city deep in the southern corner of Colombia. Two military helicopters filled with well-armed soldiers sit on the tarmac, ready for takeoff. I board one of them with Army General Roberto Pizarro.

PIZARRO: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: We're heading to Tres Esquinas in the state of Caqueta, the command post for the joint military forces in the southern region of the country. The southern joint task force is the unit that groups all military and all police forces in the states of Putumayo and Caqueta. They're devoted to combat narco-terrorism, a true evil for the nation.

[PLANE ENGINE TURNS ON, CHOPPER BLADES]

SWAFFORD: We fly over savannas interrupted by milky yellow rivers. The water quickly gives way to a thick carpet of roadless rainforest. This territory is controlled by the leftist rebel group, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, a wealthy guerrilla organization that now runs most of the illegal drug business in Colombia. On this trip, we must fly higher than normal to avoid their fire.

The forest underneath us is probably filled with members of the rebel group. It also teams with other life--ocelots, jaguars, monkeys, giant armadillos. Unfortunately, in Colombia, a map of the most fragile, bio-diverse regions of the country will fit nicely on top of a map of its drug crops.

PIZARRO: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: Look, look at those balding spots here, there, and those two over there. You can see where the soil has been disturbed. Those are coca crops.

[CHOPPER ENGINE SOUNDS]

SWAFFORD: Other areas have just been burnt down, and are ready to be planted, while others still show a bright green blanket of seedling coca plants.

PIZARRO: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: In this region of the country there are over one hundred and eighty-five thousand acres of coca crops planted right now. It's estimated that in order to maintain each planted acre, four more acres of forest need to be cleared. So, the deforestation is, in fact, four times more serious. Here, almost four hundred acres of forest have been destroyed in order to maintain such high numbers of coca crops.

SWAFFORD: I can see what he means. Each planted plot is surrounded by a wider ring of cleared land. The General points to a couple of small, red roofs. These are makeshift labs where coca leaves are processed into paste and powder. I can barely see the wooden huts hidden under the canopy. It's Pizarro's job to destroy these labs through a combination of aerial bombing and raids by ground troops.

PIZARRO: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: We launch offensive strikes against the coca crops and the processing labs on a daily basis. We destroy an average of three labs a day. Last year, we destroyed eight hundred laboratories just like this one.

SWAFFORD: Coca has a four thousand year tradition in South America and holds an important place in Andean indigenous culture. But now, it is the cornerstone of the FARC drug business, helping the guerrilla group pull in more than a billion dollars a year.

[SOLDIERS GREETING THE GENERAL IN UNISON; VOICES OF OFFICERS]

SWAFFORD: Tres Esquinas, or Three Corners military base, sprawls at the confluence of two large rivers. For the soldiers here, this is a small ring of safety surrounded by enemy territory. Its runways are long enough to handle jet fighters, radar planes, and transport aircraft, not to mention the many helicopters donated by the U.S. government.

Washington's latest investment in the drug war protrudes above the jungle like a giant white golf ball on a tee. It is a thirteen million dollar radar station that scans the horizon for small planes ferrying cocaine over the Amazon.

[SOLDIER TALKING INTO MEGAPHONE]

SWAFFORD: I follow the General to a makeshift wooden hut where a soldier on a megaphone will walk me through a VIP demo. Today, I happen to be the sole VIP around, so I get a private primer on how coca leaves are turned into coca paste.

[MOTOR SOUND]

SWAFFORD: First, a soldier chops up coca leaves that have been picked from the base's own coca plants, used for demo purposes only, of course.

[WOOD CRACKING AS MAN “DANCES” ON THE CHOPPED LEAVES]

SWAFFORD: Then, the leaves are mixed by foot with water and cement powder. I can't help but think of a great stomping scene in Tuscany. Eventually, this pulp is mixed with gasoline and sulfuric acid, a combination that disintegrates the leaves and draws out the active ingredient. The past is left to dry under the sun until it's ready to be converted into the infamous white powder. That recipe calls for many more chemicals: acetone, potassium permanganate, ammonia. Entire drums of this leftover broth are dumped into the ground or into rivers.

Add to that the thousands of gallons of pesticides, herbicides, and fertilizers these crops require. Then take that process and multiply it by the five hundred eighty tons of cocaine produced by Colombia every year. It adds up to an environmental disaster.

[VOICES, AIR CONDITIONER HUMMING]

SWAFFORD: The nervous system of this base is located inside an enormous white tent. Once inside, you feel like you are in a midtown Manhattan office. Commander Hugo Acosta runs the day-to-day operations here. And he's also responsible for relations with the local peasant community. These same farmers actually grow the coca for the guerrillas. The commander says these people are caught in a Catch-22. They would like to be able to grow their traditional crops, but these yield very little money compared to what the guerrillas pay for coca.

ACOSTA: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: We're trying to wean these people off coca by finding a way to distribute their traditional crops in other regions of the country. I've even given orders at the base to buy everything they produce--plantains, yucca, fish. I don't care if no one consumes it.

SWAFFORD: And while the peasants are paid for their labors, refusal isn't an option. Peasants have been killed for doing so. And even a side business is not allowed.

ACOSTA: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: But, what happens is that the narco-guerrillas that control the territory don't allow them to sell the very few yuccas or plaintains they grow next to the coca plants because they don't want the peasants having any contacts with the enemy of the outside world. So, the result is that the peasants are forced to grow only coca and sell it to their masters. But anyone seen contacting us is marked as a rival.

SWAFFORD: In addition to destroying coca processing labs, this base is a launching point for a controversial U.S. funded fumigation program. Each month, at least five such missions take off, made up of one small crop duster and a helicopter-riding shotgun. The plane sprays a mixture of the herbicide glyphocate and other chemicals. In the course of a year, over seventy-five thousand acres of coca crops are destroyed in this way throughout the country.

I've been promised a ride-along on one of these missions. But, just moments before I'm to board one of the fumigation helicopters, I get some unsettling news. One of them has just been shot down by the FARC.

PIZARRO: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: Yes, yes, they hit the chopper, and it suffered an emergency. And they had to land there where it was fumigating. We're going to send troops there right now to protect it.

SWAFFORD: Things are very hot now, and the General has decided to evacuate me. I had also been told I could witness the preparation of the herbicide. And there were plans to make contact with some of the peasants in the fields. Now, all that is impossible. I am escorted to a chopper which will take me out of the base area.

PIZARRO: [SPANISH]

VOICEOVER: In a way it's good you had to witness this emergency so you could see for yourself what these terrorists are all about. They're all about protecting their drug business.

[HELICOPTER DOOR OPENS AND CLOSES, ENGINES GET LOUD]

SWAFFORD: The chopper doors are opened, and I am strapped to the back seat. There's nothing to hold onto but the base of a machine gun. As soon as they drop me off, this crew will attempt to rescue their downed comrades.

[HELICOPTER SOUND FADES]

SWAFFORD: That night in Bogota, I learned that before the rescue mission could reach them, the downed crew was murdered by guerrillas. During the following weeks it's impossible for me to get into the region again. Fighting has escalated, and getting out of the main cities to try to talk to peasants growing coca is out of the question. For me, they might as well be on another planet.

For Living on Earth, this is Angela Swafford in Bogota, Colombia.

– For a slideshow of this story, click here.– To read reporter Angela Swafford’s notebook, click here.

Environmental Health Note/Chemical Sensitivities

CURWOOD: Just ahead, more on the environmental impact of Colombia's drug wars. We'll hear about the controversy surrounding the U.S. funded program to eradicate coca by spraying with herbicide. First, this Environmental Health Note from Diane Toomey.

[HEALTH NOTE THEME]

TOOMEY: Not much is known about the syndrome known as Multiple Chemical Sensitivity, or MCS. But it's generally described as a condition in which people have an acute hyper-sensitivity to low levels of chemicals such as cleaning products, pesticides, and even perfume. MCS can produce a wide range of symptoms including difficulty breathing, headaches, and nausea. Estimates of the number of people who suffer from this condition vary widely. But in one recent study, researchers tried to get a handle on the affected population through a random survey in Atlanta. About sixteen hundred people answered a questionnaire. And almost thirteen percent said they had Multiple Chemical Sensitivity.

Of those, almost fourteen percent said they lost a job because of their condition. And thirteen percent said they had to move from a home because living there aggravated their symptoms. Some speculate MCS is linked to other disorders, and this survey found that more than half of those who said they had MCS also said they suffered from other conditions, like allergies to natural substances.

Some also think MCS is linked to mental illness. But in this study, only about two percent of people with MCS reported suffering from depression or anxiety prior to onset of their symptoms. In a related study, researchers asked about nine hundred people in MCS support groups to rate the best treatments. Most highly rated were living in a chemical free house, avoiding chemicals altogether, and prayer.

That's this week's Environmental Health Note. I'm Diane Toomey.

CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Hisham Abbas “Intil Waheeda” Arabic Groove Putumayo (2001)]

Effects of Coca Spraying

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

A few minutes ago, you heard our report on the environmental devastation in Colombia due to coca cultivation and processing. But controversy surrounds one of the main methods used to stamp out the coca trade.

The country’s herbicide spraying program--an effort funded by the U.S.--has been criticized for causing its own environmental problems. Some legitimate farmers say their crops are mistakenly destroyed by the fumigation effort. And some worry about the effects the chemicals may have on people and their livestock.

David Adams is the Latin America correspondent for the St. Petersburg Times. He’s traveled through the region targeted by the government sprayers. David, first, what exactly is being used to defoliate the coca crops?

ADAMS: Well, to be honest, no one is entirely sure. It’s called glyphosate. That is the main chemical ingredient that’s more commonly known to American gardeners as Roundup--the best-sold, most effective weed killer on the market.

But in Colombia it’s mixed with some other products. And that’s what isn’t entirely clear-- is, what are the other substances that are mixed in with it? And also, what kind of concentration the glyphosate is being used at in the Colombian mix.

The other ingredients that are added are known as surfactants. And these are soapy additives that are added to the weed killer to make it stick better to the leaf, and make it more effective in penetrating the plant.

CURWOOD: Has this glyphosate been tested in tropical areas, and with what results?

ADAMS: No. While glyphosate is widely used in the United Stated, that obviously came after it was properly tested. It has not been tested for the way in which it is being applied in Colombia--from the air, aerial spraying on a massive scale. Roundup isn’t used in that fashion in the United States. And that is the reason why it is causing concern, particularly in some of these areas where it is being used in Colombia which are tropical-subtropical regions of rainforest or jungle.

In actual fact, the makers of Roundup, Monsanto, noted that on the bottles of Roundup. It specifically says: “Do not add surfactants.” The reason for that, I believe, is that just as a surfactant makes the herbicide more effective in penetrating the leaf of a plant, it can also have the same effect on skin. It may well be that while glyphosate does not cause skin irritation, when it’s mixed with a surfactant it does.

CURWOOD: Now, Roundup--glyphosate--is used pretty close to the ground in the United States. What happens when this is sprayed from aircraft?

ADAMS: Well, again, that hasn’t been studied properly. In ideal conditions--i.e. no wind, or very light wind on a clear day--the mist of tiny droplets will go straight down and land on the target. Obviously, those conditions are very rarely encountered, and when there’s any kind of wind in the area, the spray is subject to drift.

Now, there’s all kinds of computerized mechanisms that are carried on board the spray planes to take into account the prevailing weather conditions. And so, the officials who run the program claim that it’s highly accurate and very scientific, and every step is taken to ensure that the area targeted is the area hit.

I didn’t realize this at first, but it became increasingly obvious to me--until it was acutely obvious--that while I had spent time visiting these areas, they had not. So the officials administering the program are forced to use, and rely upon, satellite imagery and over-flying the area in small planes or helicopters, which, I think, is a tremendous problem. It does beg questions about whether the government has sufficient knowledge, on-the-ground knowledge, of the area it’s dealing with.

CURWOOD: Well, tell me, you’ve been there, where this material has been used on coca crops. What does an area look like, that’s been sprayed?

ADAMS: Brown. They’ve been using it for almost a decade, and they’ve improved its effectiveness by playing around with the concentration and the mix and the surfactants. So what they have now is a very effective product. When it is sprayed over the target area, it will kill everything it touches, in terms of plant life.

CURWOOD: What happens to the farmer that wants to try to replant?

ADAMS: He can forget about the plants that he’s cultivating. He’ll have to dig them up and replant. And it’ll take a few months for the soil to clean itself of the chemical spray substance. But he can be up and producing again, if he so wishes, within nine months or so.

CURWOOD: I’m sure that the people doing this are just going after coca. But at the end of the day, I suppose, mistakes do happen. An annihilated field of coca is one thing, but a destroyed plot of corn is quite another. How common is it for a law-abiding farmer’s land to be hit?

ADAMS: Well, in my experience, it’s quite common. The Colombian government, and the United States government, would argue that, on the contrary, it’s not very common and that it receives very few complaints. I would, I think, say that these are very remote, rural areas. And so, the idea of somebody actually picking up the telephone, or going around to the local office of the government to complain, is somewhat far-fetched.

But I have spoken to farmers, and I’ve seen from my own eyes where mistakes have been made. I interviewed a man who was running an internationally funded alternative agriculture program, producing hearts of palm. And his small plot had been completely wiped out. We also interviewed an organic coffee grower. His product had been wiped out. And there was no coca or opium poppies in those two areas--unless he’s lying, and you can never be sure about these things. Both those cases were pretty clear-cut, as far as I was concerned.

CURWOOD: Now I know that there have been health complaints by people who’ve been hit by the spraying. What effect do they say the chemicals have on them?

ADAMS: Skin rashes, pink eye, diarrhea, vomiting, intestinal complaints. I would say the most common would be the skin rashes.

Again, the health studies are very superficial, the problem being these are remote, rural areas. Many people don’t actually go to the local clinic or the hospital for treatment because it’s too far away. And most of these illnesses are not long-lasting. They go away. The skin rashes, for instance, disappear in three or four days…likewise, the vomiting.

What people are concerned about is the possible--and I emphasize possible--long-term health effects of being exposed to this kind of spraying. And that’s the main focus, I think, of some of the activists who are involved in this issue. It’s that they feel that this kind of massive spraying shouldn’t take place until really serious environmental and health impacts studies are conducted.

This kind of spraying would be impossible under U.S. legislation if it was being conducted in the United States. Because it’s Colombia, the United States. doesn’t have to worry about its own legislation. That’s up to the Colombian government.

But obviously, we all know that the Colombian government is under a good deal of pressure from the United States to adopt these programs and to make them work.

CURWOOD: So, David, how effective has this spraying been at dealing with the reason that they’re doing the spraying, the coca problem?

ADAMS: Well, I suppose that’s really the $64 million dollar question. And, to be fair, I think probably one should say that it’s too early to tell. While spraying has been going on in Colombia for nearly a decade, it has not been at this level of intensity for very long. That only really has been happening in the last three years.

And the latest figures do appear to indicate, for the first time, a significant drop in coca cultivation--down this last year from 358,000 acres being cultivated to around 250,000 acres. That’s a drop of 29.5 percent, according to the United Nations Drug Program, which monitors the spraying through the use of satellite imagery.

Also, last year we had, apparently, a significant drop in coca production--i.e. the finished product--down from 617 tons in 2001 to 480 tons in 2002.

CURWOOD: If you look at the figures that the government gives us about spraying in the coca areas in Colombia, it looks like it’s working. What’s your opinion?

ADAMS: There is concern that the satellite imagery that is used to estimate--and it really is an estimate--how much coca is being grown, doesn’t have a complete picture. While large areas of the country are covered by the satellite imagery, there are areas that are not. And the drug traffickers are pretty canny. And when areas are being hit, they will move. And so now we are seeing production moving away from the areas that are being intensively targeted in the south of Colombia, like Putamayo, to new areas--like, for instance, Arauca in the northeast of the country. There, production has grown dramatically.

CURWOOD: David Adams is the Latin America correspondent for the St. Petersburg Times. Thanks for taking this time, David.

ADAMS: A pleasure.

CURWOOD: There’s much more to hear from David Adams at our website, livingonearth.org. We also have photos and a reporter’s notebook from Angela Swafford’s experiences in the Colombian Amazon. That’s www.livingonearth.org.

Letters

[LETTERS THEME]

CURWOOD: Time now for comments from you, our listeners.

Ed Lowe, who hears us on KUOW in Seattle, wrote in about our story on the use of depleted uranium munitions by the U.S. in Iraq.

“You got things turned around,” he writes. “You called it ‘enriched,’ when it isn’t, and you called it ‘a coating for projectiles,’ when it is the core of the projectile.”

Thanks for the correction, Mr. Lowe. For the record, depleted uranium is just that-- depleted, not enriched. And it is only 60 percent as radioactive as natural uranium. And “DU” typically forms the core of the tip of a round of ammunition. The 25 mm rounds used in the first Gulf War contained about a third of a pound of DU.

Robin Robinson listens to KPBX in Boise, Idaho. She enjoyed our interview with author Rupert Isaacson, who wrote “The Healing Land: The Bushmen and the Kalahari Desert”.

“For years I’ve read about the Bushmen and their complex language with the clicks,” writes Ms. Robinson. “This is the first time I ever heard what their language sounded like. Thank you very much for putting on the audio clip of the conversation between the Bushmen. Now I have some idea.”

Several listeners heard our recent commentary about the danger at the bird feeder and wrote in with their own methods of out-foxing predatory cats.

This advice from Ann Walker, who listens to Living on Earth on WPSU in University Park, Pennsylvania: “Since nesting season occurs during the spring, summer and early fall, it coincides with the natural feeding season,” she writes. At this time of year, nature supplies songbirds with seeds, berries, and all manner of sustenance. Once the snow stops falling, we need to take down the feeders and allow birds to find their own food. Their natural diet supplies them with appropriate nutrition and keeps them from becoming dependent on a human population.”

We read all your suggestions, kudos, and corrections. Our e-mail address is: letters@loe.org. Once again: letters@loe.org. Or, you can call our listener line anytime at 800-218-9988. That’s 800-218-9988.

[MUSIC: West African Balafon Ensemble “Farfina” The Pulse of Life Ellipsis (1992)]

CURWOOD: “There are times of great beauty on a coffee farm,” writes Isak Dinesen in Out of Africa. “When a plantation flowered in the beginning of the rains, it was a radiant sight--like a cloud of chalk in the mist and drizzling rain over 600 acres of land. When the field reddened with the ripe berries, all the women and children were called out to pick the coffee off the trees, together with the men. Then the wagons and carts brought it down to the factory near the river. That was a picturesque moment, with many hurricane lamps in the huge, dark room of the factory that was hung everywhere with cobwebs and coffee husks.”

Thanks to Heritage Africa, you can travel to Kenya and visit a coffee plantation as picturesque as Dinesen’s. Living on Earth is giving away a 15-day trip for two on the ultimate African safari, with visits to several of the continent’s most spectacular wildlife spots, such as Kruger and the Serengeti.

Please go to our website, livingonearth.org, for more details on how to win this 15-day trip to see some of Africa’s most spectacular sights. That’s livingonearth.org.

[MUSIC]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Town Creek Foundation and the Wellborn Ecology Fund. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through Grade 12. And Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR’s coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR President’s Council.

The Fish That Changed the World

CURWOOD: For centuries, the people of Newfoundland have fished the Atlantic for cod. They built their towns and traditions around the fish and lived off its ample harvest.

But in the last few decades, cod stocks collapsed from over-fishing and pollution. And now the Canadian government has taken the drastic step of banning all commercial cod fishing in the Atlantic.

Writer Mark Kurlansky has these thoughts on this latest chapter in the history of the “fish that changed the world.”

KURLANSKY: Europeans first came to this continent drawn by the thick school of cod in the shoals off Atlantic Canada. First, the Vikings, then the Basques. Then, in 1497, explorer John Cabot reached Newfoundland. There, he and his crew announced to the world endless schools of cod of a size and thickness never before seen. This spurred one of the great migrations in history, as fleets of Europeans rushed to North America to catch its cod.

Those first Europeans, upon reaching the continent, wrote of natural riches in the land, sky, and sea, such as never before recorded in history. Most of that is gone now. As surely as the Sioux were destroyed by the killing of the great buffalo herds, Newfoundland has been destroyed.

Nowhere did cod produce a more unique culture than in the rocky inlets of this northern island. The entire coast of Newfoundland is a series of coves where villages have been built over the water, because the shore is too steep. For 500 years, men have gone to sea, many in small, flat skiffs, in water so cold that a man overboard is almost instantly dead.

Fishing and curing cod were the only work these villagers ever had. These rugged men are no sports fans and are rarely seen throwing a ball or watching a game. As children, instead of playing, they were expected to run home from school to help the women look after the catch. These solidly built, red-cheeked Northerners, with lilting brogues and ancient songs and stories, could be from any century since Cabot’s landing. This was the oldest European civilization in North America.

If the fish had lasted, this life could have continued for centuries more. With the fisheries closed, the villages of Newfoundland will be, in effect, shut down. It is impossible to say in what ways the ecology of the North Atlantic will change with one of its greatest species missing. We are changing the order of nature. Already some fisherman have switched to a profitable species of crab that was never there before. But many others will have to leave.

So, farewell to Newfoundland, the tall-rocked island of Irish songs, Jamaican rum, and little villages on stilts facing a charcoal Northern Sea. We are losing more than we know.

CURWOOD: Mark Kurlansky is author of “Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World.”

Related link:

Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World by Mark Kurlansky

Emerging Science Note/Sequencing Sargasso

CURWOOD: Coming up: Pink is not so pretty, say the critics of farmed salmon.

First, this Note on Emerging Science from Cynthia Graber.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

GRABER: Craig Ventner headed one of the efforts to map the human genome. Now, he’s going to map the genetic structure of an entire ecosystem.

The Sargasso Sea is a body of water in the Atlantic. It lies between the West Indies, Bermuda and the Azores, and it’s ideal for such an ambitious project because it’s relatively devoid of life--and so relatively easy to document.

To sequence all of the genes of all of the life-forms in the Sargasso, Ventner’s team is using tools developed for the human genome. For example, samples of seawater will be filtered and concentrated. Then the DNA of all the microbes in the water will be broken up and analyzed by powerful computers. Ventner expects to sequence the genetic structure of thousands of microbes, most of them unknown to science.

This project is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy and one of its goals is to discover new bacteria that can help in the quest for cleaner emissions and renewable energy. Some bacteria might be able to scrub carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. And still other bacteria might be able to produce hydrogen to power fuel cells.

That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Cynthia Graber.

CURWOOD: And you’re listening to Listening on Earth.

[MUSIC: Manfred Mann “Blinded by the Light” The Best of Manfred Mann Warner Bros. (1996)]

Leafy Toxins

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. There is increasing evidence from government and private studies that the rocket fuel perchlorate may be contaminating lettuce and other food crops. This news follows earlier reports that perchlorate has tainted major sources of drinking water, especially in the west.

The stakes are high for two reasons. One, perchlorate is known to disrupt prenatal thyroid development, which can lead to brain damage. Two, perchlorate is found at hundreds of sites where rockets were built or tested. And the government and its contractors could be held responsible for cleaning up the pollution, as well as any illnesses and damage linked to it.

The Bush administration recently issued a gag order to keep EPA scientists from talking about their perchlorate research. Joining me now is Peter Waldman who’s been tracking this story for The Wall Street Journal. Welcome, Peter.

WALDMAN: Hi.

CURWOOD: Peter, you’ve reported now on two studies that look to see whether perchlorate was being taken up in the leaves of lettuce. One is an EPA study and is near completion. Tell us about these newest studies. What did they find?

WALDMAN: Well, the latest one came out on Monday. And it was performed by a non-profit environmental group called The Environmental Working Group. Basically, it found that a small sample of lettuce bought in supermarkets in the San Francisco Bay Area contained high levels of perchlorate. And these samples were taken from supermarkets in January and February. Nearly 90 percent of winter lettuce throughout the country comes from Arizona and Southern California from the desert regions where it is irrigated with Colorado River water, which we know is contaminated with perchlorate.

CURWOOD: And, what’s in the EPA study that’s not quite released.

WALDMAN: The EPA study, which hasn’t been published, but has been peer reviewed, and is well along that process, was a greenhouse study, essentially an experiment in which they grew lettuce heads in greenhouse conditions, irrigated with water containing perchlorate. And, they found that it took up the perchlorate from the water and actually concentrated it, meaning there was more perchlorate in the leaves per weight than in the water that was irrigating it.

CURWOOD: Now, no one is saying that these studies are conclusive, Peter. But, what do we know about concentrations at these levels?

WALDMAN: The health effects of perchlorate are still being very hotly debated. The EPA, in its reference dose, said that one part per billion of perchlorate is the safe dose for drinking water. And now that’s just a recommendation and is now headed to the National Academy of Sciences for more review.

As far as what the EPA recommendation means, basically, they’re primarily concerned with the developing organisms. What perchlorate does is interfere with the normal production of thyroid hormones, so that babies who rely on the hormonal system to trigger development, and particularly brain development--that’s the primary concern-- would not have ample supply of thyroid to develop properly.

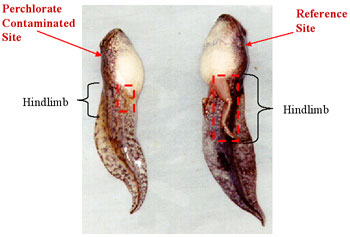

Perchorate effects on hindlimbs of tadpoles

Perchlorate has been found at high levels at many former defense sites. Dr. James Carr collected these tadpoles at a nine parts per million site in East Texas.

(Photo: Texas Tech University)

CURWOOD: Why is it taking so long to get full Federal regulations along these lines?

WALDMAN: In this case, you have a very powerful vested interest on the other side of the EPA here. And that is the Department of Defense. And their contractors, the defense industries, potential liability for perchlorate contamination in the United States ranges into several billion dollars, depending on where the standard is ultimately set. So, they are vying vigorously with the EPA over where that standard comes down.

CURWOOD: The staff of the EPA are saying one part per billion for drinking water. What does the Defense Department say?

WALDMAN: They’re saying that, according to their reading of the studies, the rat studies and a very few epidemiological studies, levels as high as 200 parts per billion would be safe for the human population. They essentially don’t believe that the uncertainty factors that the EPA scientists have applied are necessary.

CURWOOD: Now, the Bush Administration has put this gag order on employees of the Environmental Protection Agency. What do the EPA officials-- what do they tell you? And what have you learned yourself about the reasons behind this gag order on the EPA scientists?

WALDMAN: Well, as one can assume from what I’ve been saying, this is a politically hot topic. A very powerful Senator from Oklahoma, James Inhoff, a Republican who chairs the Environment Committee of the Senate has weighed in on behalf of industry. In Oklahoma, by the way, is Kerr-Magee Corporation which owned, at one time, a very, very large perchlorate factory outside of Las Vegas, which is the main source of the perchlorate that got in the Colorado River.

And, the White House and Office of Management and Budget have said hey, this is so hot between the EPA and Defense Department, we need another arbiter. So, the way they do that, in all cases of scientific dispute like this, is to refer to the National Academy of Sciences. While it’s being reviewed there, which could take as much as another year and a half or so, the EPA has instructed its scientists and regulators not to talk about it anymore, which struck me as something of a surprise because several scientists and regulators at the EPA have openly discussed perchlorate with me, on the record, in our newspaper going back six months.

And, when I called them on Friday to talk about these lettuce studies, they said, sorry, can’t happen anymore. And I called the spokeswoman of the EPA. And she said, yeah, we are not talking about perchlorate pending the National Academy of Sciences study.

CURWOOD: How common is it to have a gag order like this?

WALDMAN: This is pretty unusual. And, indeed, one EPA person did say they hadn’t experienced this in 20 some odd years in the agency.

Residents of Gilroy, CA pack a meeting after perchlorate is found in local wells.

(Photo: Gilroy Dispatch)

CURWOOD: Peter, California has a special law--I think it’s called Proposition 65--that says that all products known to cause reproductive toxicity must be labeled. As I understand it, the Prop 65 authorities may well be speeding up their review of perchlorate since the Colorado River that brings water into the state is known to contain it. Could the water itself be labeled in California, do you think?

WALDMAN: Well, it’s quite possible. The California Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment has begun an expedited review of perchlorate to see if it would fall under the requirements. And, it is possible, after that, bottled water that contains perchlorate will have to be labeled.

CURWOOD: What about lettuce?

WALDMAN: That’s a good question. I would think that, given the broadness of Prop 65, it would also need such labeling. And it’s not just lettuce, by the way. Those are where the early studies are. But, all leafy vegetables that are grown with water contaminated with perchlorate are likely to have some in the leaves. So, a lot of the winter vegetable crop of this country is grown with Colorado River water.

CURWOOD: Peter Waldman is a reporter for The Wall Street Journal. Peter, thanks for speaking with me today.

WALDMAN: Good to be here, Steve.

Debate Over Farmed Salmon Grows

CURWOOD: Much of the fresh salmon at your local seafood counter comes from fish raised in ocean pens. On the one hand, the notion of fish farming is appealing at a time when the ocean’s wild fisheries are in sharp decline. But, critics say salmon farms contaminate the ocean floor and produce a product that may not be as healthy to eat as wild salmon.

In Seattle, recent lawsuits target grocery stores for not disclosing that farmed salmon contain pink dye to make them look more appealing. But it is in British Columbia where tension over farmed salmon are strongest right now in the wake of the government’s recent decision to lift a moratorium on building new fish farms. Don Genova has our report.

GENOVA: British Columbia’s farmed salmon industry has been under attack for more than a decade. After rapid growth in the 1980’s, by the mid-‘90s, the provincial government had slapped a moratorium on additional farms. At issue were concerns the farmed salmon could pass parasites or diseases onto wild salmon, that the salmon pens created a massive untreated sewage on the ocean floor, and that farmed Atlantic salmon would escape, breed and crowd out their Pacific cousins.

The government lifted that moratorium last September. Opponents in turn have ratcheted up their campaign. A few weeks ago, they descended on a salmon farm in BC’s remote Browten Archipelago.

ative Canadians protest salmon farming.

(Photo: ©UBCIC)

[SPEAKING AT A PROTEST]

GENOVA: Chief Bill Cranmer of the Numgis First Nation called on other native bands in the area to support closing the farms and end any involvement they have with salmon agriculture. In December, protestors destroyed part of a farmed salmon hatchery. Suspected vandalism has cost companies thousands of dollars in escaped fish and damaged net pens. Many commercial fishermen have also joined the movement.

Ritchie Shaw made a two-day journey to the Archipelago. He’s trying to protect a pink salmon run he’s fished for years.

SHAW: They’ve got some serious issues with disease, with lice. What they’re doing is they’re lousing up a perfectly good wild stock that we’ve had here forever. And, we don’t know why. Like what’s the reason for it? That’s what we want to know. We’d like them out of here.

GENOVA: Government regulators believe the sea lice infecting the farmed salmon in the Broughton Archipelago may be a threat to migrating wild salmon. So, some of the farms are shutting down for the time being. But they’re not leaving. Dr. Ted Needham speaks for Heritage Aquaculture, one of the companies affected.

NEEDHAM: There’s no question. We’re feeling our way. And if we are doing any harm to wild stocks, there must be appropriate regulation to prevent us doing so. And this is why we have followed a huge area of the Broughton to allow the next lot of out-migrating pinks, we hope, come out without threat.

GENOVA: Needham’s reassurances that the salmon farmers will do the right thing doesn’t impress marine researcher, Alexandra Morton. She’s been studying fish farm habitats for years.

MORTON: I think the farms have over-saturated this area. I think the whole Broughton Archipelago needs to be followed. And then we need to reconsider, once the wild stocks have stabilized, we need to reconsider this industry. They have to abide by some rules. They have to really respect the biology of the situation.

GENOVA: Until recently, most of the protests against farmed salmon targeted the governments regulating the industry. Now, the message is being taken to people who eat the fish.

[SINGING: Salmon swim ten thousand miles a year, John-canack-anacky-too-rye-ay, Oh, they crawl with lice in the fish farms here….(fades)]

GENOVA: It’s Saturday afternoon at a recent environmental forum on ocean ecology in Vancouver.

[SINGING FADES; CROWD NOISE]

GENOVA: Activists at the forum called for a farmed salmon consumer boycott. Kate Dugas speaks for the Living Ocean Society and is part of the Farmed and Dangerous Campaign, developed by a coalition of organizations pushing for aquaculture reform.

DUGAS: Don’t buy farmed salmon. The environmental impacts, I think, of farmed salmon or of the industry are huge. They are really, really dangerous on the marine environment, and really need to be reformed.

GENOVA: Along with the environmental message, Farmed and Dangerous representatives claim farmed salmon isn’t healthy to eat. For example, they say it has 200 percent more saturated fat than wild salmon. But that’s not the whole picture, according to Dr. Charlie Santerre, an environmental toxicologist and food scientist at Purdue University in Indiana.

SANTERRE: It’s true that farmed fish tend to be higher in saturated fat. Although, the part that they’re not telling us is that the amount of saturated fat in the fish is still lower than many other meats, like pork or beef.

GENOVA: Santerre also questions claims by the Farmed and Dangerous campaign about omega-3 fatty acids, which promote cardiovascular health and are essential in late pregnancy for fetal brain development. The campaign says farmed salmon contain fewer beneficial omega-3s.

SANTERRE: Now, that claim is patently wrong. If you go to the U.S. Department of Agricultural website, and where you can check on the fat content of various foods, and we did a comparison between farmed and wild Coho salmon, farmed and wild Atlantic salmon, and farmed and wild rainbow trout. And in each of these cases, the amount of the long chain omega-3 fatty acids, the EPA and DHA was higher in the farmed versus the wild.

GENOVA: Perhaps most disturbing, the Farmed and Dangerous campaign is distributing flyers that claim farmed salmon contain unhealthy levels of PCBs. PCBs accumulate in fatty tissue and are linked to neurological and immune problems in children. Farmed salmon critics cite a preliminary study by geneticist, Michael Easton, published in the journal Chemosphere. Easton looked at the fish pellets fed to farmed salmon. And he also compared farmed salmon to wild.

EASTON: We found considerably higher level of PCBs in the salmon feed and in the farmed salmon than we found in the wild salmon that we examined.

GENOVA: Using PCB limits established by the World Health Organization, which are much stricter than the Food and Drug Administration, Easton found that a lightweight adult should eat no more than two servings of farmed salmon per week.

EASTON: I really think that eating fish high on the food chain can be a serious problem. We have to realize that our oceans are contaminated. We have dumped a lot of stuff in the oceans over the year. It’s got hooked into the food chains, into the marine food chains. We contaminate the natural fish products we eat. And the higher up the food chain you are, the more contaminated they actually are.

GENOVA: But this study had an extremely small sample size. Easton analyzed only four farmed and four wild salmon. He is now seeking funds for a far larger study. His study is also criticized for having been funded by an environmental organization.

Charlie Santerre whose work focused on pregnant and nursing women sharply disagrees with Easton’s food recommendations. He says farmed salmon may, indeed, contain ten times more PCBs than wild. But the amounts are still inconsequential by FDA standards.

SANTERRE: My biggest concern was that they were driving our sensitive populations away from an excellent fish. Farmed salmon is the fish of choice for pregnant, nursing women and children. But by scaring people away from salmon, consumers would go to a more contaminated, less nutritious fish. And that would include swordfish, shark, and king mackerel.

GENOVA: While Santerre tries to set the record straight with his point of view, all the negative messages about farmed salmon are getting through to consumers. And they’re speaking out.

[RESTAURANT SFX]

GENOVA: Milestones is a chain of upscale casual restaurants in BC, Ontario and Washington state. At lunchtime, this Vancouver location is busy. But it’s not farmed salmon on the grill. Cathy Tostenson, marketing director for Milestones, says customer complaints have pushed it off the menu of all 23 restaurants in the chain.

TOSTENSON: We would have our guests ask our servers what type of salmon we would be selling. And, when they found out it was farmed salmon, they would often- times elect to make a different choice. So, there’s no question you can’t open up a newspaper, listen to a radio, or listen to the television without having a discussion taking place on these farmed salmon.

GENOVA: After ten years of serving farmed salmon, Milestones is switching to wild, using frozen product until fresh catches are available later this year. Days after the Milestones announcement, the Spectra Restaurant group made a similar announcement, affecting its 29 Pacific Northwest restaurants. Another major Canadian restaurant chain, The Keg, is considering the same move.

The loss of business will hardly cripple the Canadian aquaculture industry. Demand for affordable salmon is still growing. And Canadian production alone is worth over $300 million dollars a year. For Living on Earth, I’m Don Genova in Vancouver.

Related links:

- BC Salmon Farmers Association

- Farmed and Dangerous Campaign

- Preliminary Study by Michael Easton in Chemosphere

CURWOOD: And for this week, that’s Living on Earth. Next week, we take an in-depth look at cutting edge science on the connection between childhood lead exposure and criminal behavior later in life. The neuro-toxins effect on impulse control and anger may hold the answer about why some young adults are out of control.

LAQUISHA: If I just don’t sit down and just be still and just try to cool down, I just blow up. I just be so mad. But I just can’t help it sometimes.

CURWOOD: It’s “The Secret Life of Lead,” next time on Living on Earth. And remember that between now and then, you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to livingonearth.org. And while you’re there, you can also get a chance to win a safari for two to Africa. That’s livingonearth.org.

[AIRCRAFT ENGINE: Earth Ear “The Song of This Place” Dreams of Gaia Earth Ear Records (1999)]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week gazing up in wonder.

[AIRCRAFT ENGINE]

CURWOOD: From her work, “The Hidden Tune,” this is Berlin sound artist Sabine Breitsameter’s sonic ode to flying machines.

[AIRCRAFT ENGINE]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation in cooperation with Harvard University. You can find us at livingonearth.org. Our staff includes Anna Solomon-Greenbaum, Maggie Villiger and Jennifer Chu, along with Tom Simon, Jessica Penney, Al Avery, Susan Shepherd, Carly Ferguson and Liz Lempert. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. We had help this week from Katherine Lemcke, Jenny Cutraro and Nathan Marcy. Allison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar.

Our technical director is Chris Engles. Ingrid Lobet heads our western bureau. Diane Toomey is our science editor. Eileen Bolinsky is our senior editor. And Chris Ballman is the senior producer of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood, executive producer. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science, and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, supporting the Living on Earth Network, Living on Earth’s expanded internet service. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Annenberg Foundation, and Tom’s of Maine, maker of natural care products and creator of the Rivers Awareness Program to preserve the nation’s waterways. Information at participating stores or tomsofmaine.com.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

This Week's Music

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth