October 17, 2003

Air Date: October 17, 2003

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Science And Politics At The EPA

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Debate about the new choice head of the EPA has triggered criticism about how the agency operates within the Bush administration. Critics say the White House is warping science to meet a political agenda, a charge the administration denies. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young reports. (07:00)

Greenpeace And The Law

View the page for this story

The federal government recently brought criminal charges against Greenpeace for an act of civil disobedience carried out by members more than a year ago. Host Steve Curwood discusses the implications of the legal maneuver with George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley. (05:30)

Almanac / Celestial Passings

View the page for this story

This week, we have facts about the first known record of a solar eclipse. More than 4,000 years ago, Chinese astronomers divined the health of their emperor from the activity in the sky. (01:30)

A Brand New Bird

View the page for this story

For years, bird breeders in Europe were fixed on breeding the perfect singing canary. They later shifted to breeding for the most brilliant plumage. And in the late 1920s, two German bird breeders decided to take this goal one step further. Host Steve Curwood talks with author Tim Birkhead about the quest to breed the first red canary. (08:00)

Lewis & Clark Trail

View the page for this story

This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Lewis & Clark expeditions. Producer Barrett Golding bicycled the entire Lewis and Clark trail and sent us this audio postcard from Montana’s Miles City, and the famous Bucking Horse sale. (03:30)

Easy Rider

View the page for this story

Australian Shaun Murphy, also known as the Eco-Trekker, is travelling across the United States. As he tells host Steve Curwood, he’s using non-polluting vehicles powered entirely by renewable fuels. (03:00)

Emerging Science Note / Mitigating C02

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports that ozone may be harming soil's ability to absorb carbon. (01:20)

Ducks Unlimited

/ Will KilburnView the page for this story

Hunters often get a bad rap from folks who consider themselves environmentally conscious. But, as producer Will Kilburn reports today’s modern hunting organizations are also some of the most progressive and aggressive land and wildlife conservationists. He profiles the group Ducks Unlimited. (10:00)

Leaves & Lives

/ Bob CartyView the page for this story

Producer Bob Carty has an audio montage about the joys and hardships that the dropping of leaves brings us each fall. (05:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The White House is coming under fire for allegedly bending the laws of science to fit a political agenda at the EPA.

RUCH: It’s one thing for the political appointees to set overall policy. But it’s another for them to reach down and alter scientific recommendations and conclusions or to suppress those that don’t fit a political agenda.

CURWOOD: But Bush administration officials dismiss the charges as baseless and politically motivated.

CONNAUGHTON: I think it’s actually a myth to suggest interference in the scientific process. We are actually charged with managing that process.

CURWOOD: The soundness of science at the Environmental Protection Agency this week. Also, frolicking in the fall foliage.

FEMALE: He parted some of the leaves away and took my face in his hands and gave me a big kiss.

CURWOOD: Ummm, [SOUND OF KISS] Baby. That and more on Living on Earth, right after this.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from The National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Science And Politics At The EPA

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

After weeks of delays, the nomination of Utah Governor Mike Leavitt to head the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has been reported out of committee to the full Senate. But the controversy about his nomination is far from over. In fact it’s escalating into a barrage of criticism, not so much about Governor Leavitt himself, but about the relationship between the EPA and the White House. Some members of Congress, along with some scientists and advocates, charge that the White House is suppressing or altering science at the EPA to suit a political agenda. From Washington, Living on Earth’s Jeff Young has our story.

YOUNG: New York Democrat Hillary Clinton is among the Senators using Leavitt’s nomination as a platform for complaints about the EPA and how it operates in the Bush administration. Her issue is the agency’s response to air quality questions after the 9-11 terrorist attack in Manhattan.

CLINTON: Now I recognize that EPA and everyone else involved was operating under extraordinarily difficult and unprecedented circumstances. But I just cannot accept that there seems to have been a deliberate effort at the direction of the White House to provide unwarranted reassurances to New Yorkers about whether their air was safe to breathe.

YOUNG: Senator Clinton cited an EPA Inspector General report that found the White House pressured the agency to make statements about air safety which were not supported by data. North Carolina Democrat John Edwards says the agency is slow to examine health effects of changes to the Clean Air Act. And Vermont Independent James Jeffords wants answers about the president’s new rules on coal-fired power plants. Clinton said all these grievances reflect an underlying problem.

CLINTON: It appears that environmental policy in this administration is set at the White House, not at the Environmental Protection Agency.

YOUNG: It’s a complaint echoed by some past EPA administrators, including Russell

Train. Train was involved in the talks 33 years ago that established EPA as an independent agency charged with protecting the nation’s environment. He later led EPA under Presidents Nixon and Ford.

TRAIN: I don’t really ever recall any pressure from the White House when I was at EPA to change a regulatory position. As far as I was concerned, that was unheard of.

YOUNG: These days, Train says, he hears of far too many instances of political pressure guiding EPA decisions.

TRAIN: I think the White House is making a very big mistake to inject itself in that fashion into the regulatory process. Public health will suffer and I think that’s a very bad road down which to go.

YOUNG: Train fears that lack of independence will affect the science the agency conducts and communicates with the public. Bill Hirzy, a senior scientist in EPA’s office of pollution prevention, shares that concern. Hirzy is also vice president of the union local for EPA professional staff. He says staff members worry about things like the recent report on the state of the environment. A draft of the report mentioned the potential health consequences of global climate change. But after an editing session with the White House, that changed.

HIRZY: The reference to global warming just vanished from the report. The scuttlebutt among the staff is that this report does not really comport with the best science. It is simply not supported by the science and that’s a shame.

YOUNG: Critics say actions like those cross a line into science where politics should not interfere. Jeff Ruch leads Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, an advocacy group for workers who want to bring attention to questionable behavior by government agencies.

RUCH: It’s one thing for the political appointees to set overall policy, but its another for them to reach down to try and alter scientific recommendations and conclusions or suppress those that don’t fit a political agenda. You see this either kind of scientific manipulation or pressure across the board of EPA programs. You’ve got scientists who have to make decisions between their conscience and their career. And those are the kind of calls we get at PEER.

YOUNG: Complaints like those sparked a report by Democrats in the House Committee

on Government Reform. The report looked at examples of political pressure on EPA and other agencies and concluded the Bush administration had, quote, "manipulated the scientific process and distorted or suppressed scientific findings," end quote. James Connaughton finds himself on the receiving end of much of this criticism. Connaughton chairs the White House council on environmental quality. He’s the president’s coordinator and top advisor for environmental policy. Connaughton says the White House acts on only a small number of EPA issues and he denies any interference with the agency’s science.

CONNAUGHTON: Well, I think, actually, the point is the politics never interfere with the science. In fact, the administrations are charged with implementing research agendas, managing scientific enterprise, then gleaning from that information important to make policy decisions. So I think it’s actually a myth to suggest interference in the scientific process. We are actually charged with managing that process. And so, it’s not an issue of interference. It’s an issue of how you’re managing the process, what you take from the scientists and how, as a policymaker and as a communicator, you convey your own views as to what that science means to you.

YOUNG: The EPA did not make officials available for comment for this story after repeated requests over the course of a week and a half. But Acting EPA Administrator Marianne Horinko addressed some of the criticism in a recent speech to the American Bar Association. Horinko said it’s the critics, not White House politics, hurting the agency, with what she called, quote,"debate marked by an unusual degree of rancor, stridency, and naked political partisanship," end quote. Russell Train does not consider himself a partisan critic – after all, the two presidents he served were both Republicans. Train says those administrations understood that the EPA’s integrity is at risk when it loses political independence.

TRAIN: That integrity will be progressively impaired and eventually destroyed in the public eye if it becomes simply a political instrument. I think that’s exactly it, and I think that’s what we’re going to see.

YOUNG: It’s an issue we’re sure to see more of in the coming months, especially as

the Senate considers the next EPA administrator. For Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young in Washington.

[MUSIC: Passengers “One Minute Warning” ORIGINAL SOUNDTRACK (Island – 1995)]

Related links:

- Environmental Integrity Project

- Politics and Science, House Committee on Govt. Reform Report

- The Council on Environmental Quality

- PEER

Greenpeace And The Law

CURWOOD: The federal government has filed a criminal indictment against the U.S. Greenpeace organization over an action near Miami a year and half ago. Two Greenpeace activists boarded a ship off the Florida coast to protest what they claimed was importation of illegal mahogany from Brazil. They were later convicted and sentenced to jail. That’s a common outcome for, what some would call, an act of civil disobedience. But, according to Jonathan Turley, legal scholar and law professor at George Washington University, the indictment of the entire Greenpeace organization for the actions of two of its members marks a turn in American politics.

Professor Turley joins me now. First, tell me about this law federal prosecutors are using to charge Greenpeace.

TURLEY: It harkens back to 1872. And it’s a law that is designed to prevent what the courts called “sailor mongers,” or people that would go to ships that were approaching a harbor and try, through alcohol and other devices, to get the sailors to leave with them. There’s actually only two reported cases that we could find where this law was actually cited.

CURWOOD: How unusual is it for the federal government to charge an organization with criminal activities when it’s members are conducting nonviolent protests?

TURLEY: It is not uncommon for organizations to be subject to criminal prosecution for environmental crimes, for anti-trust crimes, and for an assortment of other types of offenses. But usually, throughout our history, when people have engaged in free speech, the government has acknowledged that as the motivation. The government has taken steps to show some degree of balance. While you can, and often protesters are charged with trespass and other types of violations, the government acknowledges, through prosecutorial discretion, that this is an exercise of the first amendment. So, while you can’t escape punishment, it also calls for a measure of restraint from the government.

In this case, two of these protestors, the people who climbed on to the ship, admitted guilt and they accepted misdemeanor convictions and the time served. And that, to most people’s eye’s, satisfied the merits of the case, the demands of the case. Then months later, out of the blue, the government came down with an indictment against Greenpeace. And that took all of our breath away. It was quite remarkable, quite novel, and, in fact, was quite chilling. That if the Justice Department is going to dig up an 1872 law to find a way to proceed against an organization, it sends a very chilling message to other organizations.

CURWOOD: Judging by the letter of the law, Greenpeace could be found guilty. In fact, the organization’s executive director says, “yeah, I authorized this.” What would it mean for the organization?

TURLEY: Well, for the organization it means a couple of things. One is there’s a fine, which the organization could sustain. It’s like ten thousand dollars. But it also means that they would be put on a form of probation which requires them to regularly report to the government. That type of reporting raises some real first amendment issues. To have an organization that has been, perhaps, the most vocal against this administration forced to report to it really does create an obvious problem. And also, it does endanger the organization’s tax exempt status. And for an organization like Greenpeace, if they lose that status it effectively is a death knell for the organization.

CURWOOD: How high up in the Bush administration did the order for this prosecution come, do you think?

TURLEY: I would have to assume that this was approved at the highest level, which would include Attorney General John Ashcroft.

CURWOOD: Civil disobedience has always been illegal. I mean, a sit-in is a form of trespassing, usually, typically. But the government has not chosen to prosecute entire organizations, recognizing that civil disobedience, well, plays a major part in American civic life. And historically, of course, has been crucial as we’ve seen with the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War protests. What does this case say about dissent in the U.S. today?

TURLEY: Well, one can only assume that this case was approved for a reason other than the insular facts. I mean, you don’t attempt to apply such an arcane law to a case of civil disobedience unless it’s part of an overall policy, a change, a shift. And I would expect if they’re successful here, it will be replicated.

CURWOOD: What other groups might be affected by this decision?

TURLEY: Well, you know, part of the problem and part of the danger here is not just that some groups might be affected, but that some may not be. That the government might selectively prosecute organizations. And there is some evidence that might be a possibility. We have not seen the government use these types of laws against anti-abortion groups. We’ve seen them prosecute individuals, but we’ve never seen this turning on an organization with this type of vigor. And so the greatest concern is not just that it’s going to have a chilling effect upon free speech, not that’s it’s going to be targeting organizations engaged in free speech, but that it’s going to selectively target organizations.

CURWOOD: Jonathan Turley teaches law at the George Washington University. Thanks for taking this time with me.

TURLEY: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Wilco “Radio Cure” YANKEE HOTEL FOXTROT (Nonesuch – 2002) ]

Almanac / Celestial Passings

CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: Orb “a huge ever growing pulsating brain that rules from the centre of the ultraworld: live mix mk 10” THE ORB’S ADVENTURES BEYOND THE ULTRAWORLD (Inter-Modo – 1991)

]

CURWOOD: This week in 2136 B.C. a black disc crept across the sun and a veil of darkness spread across China. It was the earliest known record of a total solar eclipse and went down in the logs of Chinese astrologers who were expected to read the future and health of their emperor from signs in the skies. If they didn’t get it right, it was off with their heads.

Today, calculating the appearance of a solar eclipse is a bit less perilous. But forecasters can still have fussy customers, as eclipse chasers can go to great lengths to get to the perfect viewing location – even if the whole experience can be ruined at the last minute by clouds.

One of these chasers is Brenda Culbertson, who traveled from her home in Kansas to Mexico in 1991 to catch her first total eclipse of the sun.

CULBERTSON: It was so black that nothing could describe it. It was like a hole torn in the sky. It was so quiet around there you could hear a pin drop. And then people finally started breathing again, well, because they needed to. It was just that great.

CURWOOD: To view the next total solar eclipse this November 23rd, Brenda Culbertson will need some polar gear. According to the NASA, that one will quickly traverse the Southern part of Antarctica. Or she can wait for March 29th, 2006 for an eclipse that can be seen from Central Africa to Russia. And for this week, that’s the Living on Earth Almanac.

[MUSIC: Miles Davis “Shhh/Peaceful” IN A SILENT WAY (Sony – 1969) ]

A Brand New Bird

CURWOOD: Back in the 1920s, Hans Duncker, an amateur bird breeder was walking down the streets of Bremen, Germany when he heard something that stopped him in his tracks. It was a nightingale song, but it was the wrong place and the wrong season for a nightingale to be singing. Turns out a canary breeder, Carl Reich, was exposing his birds to nightingale songs and eventually, these canaries had started singing like nightingales.

The idea started Herr Duncker thinking, and he set out with Carl Reich to try and alter another aspect of the canary – its color. By hybridizing, or breeding the canary with another species of bird, in this case, the red siskin, they hoped to create the world’s first red canary.

|

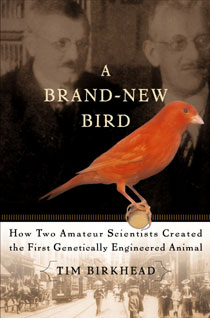

Tim Birkhead has written a book about this quest called “A Brand New Bird: How Two Amateur Scientists Created the First Genetically Engineered Animal.” He joins me now from the University of Sheffield, in England. Tim, welcome.

BIRKHEAD: Hello. CURWOOD: Now, Tim, this is a pretty strong claim that you make in the subtitle of you book. How is it that the red canary is the first genetically engineered animal? BIRKHEAD: A lot of people think that a genetically engineered animal is one that’s been produced since the kind of human genome project. But the red canary was the first genetically engineered animal because it happened a long time ago in the 1920s. The red canary is actually what we would call a transgenic animal. It’s got the genes of another species inside it. Basically, the red canary is a canary with the genes of something called a red siskin, a little South American finch in its genome. CURWOOD: Why did Herr Dunker and Reich decide on a red canary as their goal? BIRKHEAD: There were two strands that, I think, came together to create this. First of all was a story that Karl Reich told, which was a well-known story in canary breeding circles, about an event that happened in Britain in the 1870s. Bird shows, particularly canary shows, were incredibly popular at that time. And at this particular show, a certain Mr. Edward Bemrose turned up with canaries that were the color of marigolds, and he won every prize going. And the secret was simply by feeding your canary on red peppers during the time that it was molting. The color from the red peppers somehow changed the color of the feathers from yellow to orange, but certainly not red. So, that was the first strand. The second strand was when Hans Duncker met a wealthy Bremen businessman, Consul Karl Cremer. And Cremer was somebody who was obsessed by caged birds. And when Duncker went to see him, one of the little birds that Cremer had was something called the red siskin from South America. The Spanish, who had imported the birds to the Canary Islands, regularly hybridized the red siskin with the canary. And as soon as Duncker heard this, he felt that any fool could feed a bird on red peppers. There was no skill in doing that, but he certainly had this vision that if he could capture the genes that would turn a canary red, now that really would be something. And the idea was that they would hybridize the red siskin with ordinary yellow canaries, they would back-cross those to ordinary canaries over several successive generations, whittling away everything that they didn’t want from the red siskin, but retaining the red genes. And they do this buy simply keeping the reddest birds. Of course, hybridization was extremely widespread. People had been doing that for a long time, particularly in the bird breeding world. What makes this project particularly striking is that Duncker wasn’t satisfied with just hybridizing the red siskin with the canary. What he wanted to do was just to get the genes that made the plumage red. And so an explicit part of his project was this business of back-crossing the hybrids with canaries and getting rid of all those unwanted genes. So he had his mind focused very clearly on just those one or two genes that made the red siskin red and getting those into a canary. That’s what makes this a special transgenic animal decades before its time. And Duncker predicted that after maybe four or five generations they would have red canaries. CURWOOD: Now, this story is all taking place in the late 1920s when Germany is having its difficulties. And eventually, in the 30s, Hitler comes into power there with the Third Reich. What impact did Hitler’s regime have on the world of canary breeding? BIRKHEAD: The rise of the Nazis in Germany coincided with the time when Hans Duncker was actually losing interest in the red canary project. He tried breeding his hybrids – he succeeded in producing hybrids – he tried back-crossing them. The trouble was that they weren’t red. Now when he’d done his initial crosses between different colored canaries, green canaries and yellow canaries. What he found was the green color, which is the color of the wild canary, was always dominant over the yellow color which was recessive. And as a result, if he crossed a green canary with a yellow one, invariably the offspring were green. He assumed that exactly the same thing would be true when he crossed the red siskins with ordinary yellow canaries. But it wasn’t. And that was almost certainly because he didn’t realize how complex the genetic mechanism was. So all he could achieve were these bronze, coppery-colored birds, so he started to lose interest by about 1930. And this coincided with the rise of the Nazi regime. Interestingly, because Duncker was a school teacher and because he was an expert in genetics, that made him extremely attractive to the Nazis. And they were very keen to get him on board. And Professor Hubert Walter of the Bremen University had kind of identified Duncker’s Nazi role and singled him out and said he was a disgrace to biology because he had helped to perpetuate some of the Nazi views. And I was extremely disappointed because prior to this I had imagined setting Duncker up as a kind of genetic hero. Nonetheless, I’m sure this colored the way other people saw him and why Duncker’s pioneering work in these genetically modified birds eventually disappeared into obscurity. CURWOOD: You write that there was a crucial turning point in the red canary saga involving our understanding of how genes work. Could you outline this for us please? BIRKHEAD: The turning point happened in North America about 10 or 15 years later. Charles Bennett was a research physiologist, keen bird breeder, and interested in these orangey-colored canaries. And he’d imported some from Germany. Then he was reading a medical journal and came across a very bizarre account of how several women had lived on a diet of carrots for several weeks, and they’d all turned a deep orange color. And this gave him the idea of feeding carrot extract to some of his orange canaries that he’d had from Germany, but also some of his regular yellow canaries. When he gave the carrot extract to the yellow canaries, and waited for them to molt, there was virtually no effect. The feathers re-grew almost exactly the same color. But when he fed the carrot extract to the orange canaries, the new feathers came through an even darker shade of orange. And this was, you know, the eureka moment if you like. Because Bennett realized that what Duncker had tried to do was impossible. It wasn’t just a genetic effect, you also needed this environmental input. CURWOOD: What’s really fascinating here is that Hans Duncker was able to make this link between genetics and the environment back in the 1920s, but for some reason he couldn’t seem to apply it to his work with the search for the red canary. What happened? BIRKHEAD: It’s very interesting that when Duncker was interpreting how Reich had managed to create these nightingale canaries, he recognized that the canaries that Reich had bred had to learn the nightingale song. But what Reich had done was select birds that had the genes for the ability to learn. So Duncker recognized that both genes and the environment were crucial in creating Reich’s nightingale canaries. But he was, again, decades ahead of his time in this respect. And my sneaking suspicion is that because nobody ever patted him on the back for this and said “that’s brilliant,” he kind of flipped back into the genetic, deterministic thinking that was so prevalent at the time. And I’m convinced that had his work been recognized by more professional scientists, it might have changed the way he thought subsequently. CURWOOD: Tim Birkhead is a professor at the University of Sheffield in England and author of “A Brand New Bird: How Two Amateur Scientists Created the First Genetically Engineered Animal.” Thanks for speaking with me today. BIRKHEAD: Thank You.

Lewis & Clark TrailCURWOOD: This year marks the 200th anniversary of the Lewis & Clark expeditions. [WATER SPASHING; SOUND OF CRICKETS AND FROGS] MALE: Paddle. C'mon harder. CURWOOD: We wondered who lives and works along the trail now, from the Northwest Coast to the mouth of the Missouri. [DRUM BEAT, WOMAN YELLING, “ONE, TWO, THREE!; MUSKET SHOT; SOUND OF CRICKETS AND FROGS] CURWOOD: Producer Barrett Golding bicycled the entire Lewis and Clark Trail and sent us a series of audio postcards. [SOUNDS OF AUCTIONEER] CURWOOD: Like this one from eastern Montana along the Yellowstone River where each year the town of Miles City hosts the famous Bucking Horse Sale where broncs and bulls are rode and sold. It's a rodeo, an auction, and, for people like Doug Davis of Hot Springs, Montana, a way of life. DAVIS: Well, yeah, I rodeo, bud. Bronc rider, bull rider. I rode bulls last night and I’m riding two broncs today and just having a good old time. I brought my ten year old son. This is something you’ve got to see now because it may not last. It is such a great time to get on a bucking horse. One that really bucks hard and really goes at you. It’s also a lifestyle that my family’s revolved around. It’s all we do, rodeo. I mean we have to work but we rodeo. That’s our main thing to do. [SOUND OF AUCTIONEER] DAVIS: Just a little while ago I got bucked off right outside of that shoot, not very far, and I just laid on the ground with my head like this, like, hmm, how the hell did that happen? The horse beat me. She beat me out of there, she got ahead of me. She bucked me off and I just laid there on the ground, my head like this, going – pretty nice horse. You know, take your hat off to the horse, a little respect for the animal. They beat you. It’s a game – competitive. [SOUND OF METAL CLANKING, CHEERING] MALE: Come on! Come on! Come on! DAVIS: You got competitors, but you’re friendly with your competitors. You’re partners. I mean, the guy that’s helping you saddle your horse is going to try to beat you. It don’t matter. He’s going to help you get things right. That’s just the way we do it. It’s just a cowboy thing, you know. This is the greatest sport in the world. It originated here in this country. It’s tough, and it’s fun, and it’s a passion. [SOUND OF AUCTIONEER; YELLING; METAL CLANKING] DAVIS: I was 17 when I started riding bulls. I’ll be 34 next month. I got a scar from here to here last Fourth of July, and 42 staples in my belly. A bull stepped underneath my vest and ripped my guts open. Cost me 20 grand. So, you look at that and you think, all right, I’ve got a ten year old boy, I’ve got a wife, a job. Should I quit this? Oh yeah, for about four months I did. Got held up, jumped right back out there and went back at it. It’s just life. Go for it. You know it ain’t that life’s too short; it’s just that you’re dead for so long. So get all of it you can. You’ve got to get it all. [SOUND OF HORSE BRAYING] CURWOOD: Doug Davis of Hot Springs, Montana. Barrett Golding's portraits of “The Lewis & Clark Trail: 200 Years Later” are part of the Hearing Voices series, funded in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. For more audio, images and interviews from the trail, go to our website, livingonearth.org. And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth.

Easy RiderCURWOOD: You won’t hear the words “fill ‘er up” uttered at a gas station anytime soon by Shaun Murphy. The Australian Murphy, who calls himself “The Eco-Trekker,” is traversing the U.S. using vehicles powered only by alternative and renewable resources. He joins me now from the road in Wisconsin. Shaun Murphy, just where are you? MURPHY: I’ve just ran out of charge on one of my electric vehicles in a little town called Brandon in Wisconsin. It’s a pretty cute town. CURWOOD: Now, you’re changing vehicles and using sustainable energy as you travel around the U.S. What are you going to do if you run out of a charge now? MURPHY: Well, what I’m doing is – this leg I’m traveling from Green Bay all the way down to Chicago using only electricity fired by cow manure. So, I’ve got a charge-up about five miles down the road. I’ve got the crew here with another vehicle which is actually a Harley look-alike but it’s got a totally electric motor. CURWOOD: Now, why are you doing this? MURPHY: I’ve had this passion to travel all around the world using only renewable energy and hook up with all these magnificent people who have got these different eco-energies and innovations. So I thought, let’s try to do it in the land of the car. Let’s try to do it in America. So we’ve been on the road for about two months now, trying to hook up with any renewable energy we can get, with any vehicle we can get. And so far, so good.  Shaun Murphy in a solar canoe on the Klamath Lakes,near the borders of Oregon and California. Shaun Murphy in a solar canoe on the Klamath Lakes,near the borders of Oregon and California.

CURWOOD: So, what do you figure is the most unusual fuel that you’re using on this journey? I would nominate the cow poop. MURPHY: Cow poop’s pretty unusual, yeah. But once we hit Florida we’re actually using electricity that’s produced from sugarcane, from the bagasse fiber. After they extract the juice from the sugarcane they then heat and burn the sugar cane itself, the actual bagasse. So, we’re going to fire up from sugar mills up through Florida. That’s pretty cool. And veggie oil across Texas in a diesel motor. That should be a bit of fun. So we’ve got a good little mix. CURWOOD: What do you think of American drivers? MURPHY: You know what? They’re more respectful then Australian drivers, that’s for sure. Australian drivers try to run you off the road. The American’s have actually been really kind. I’m sure that may change when I hit New York, I’m not quite sure…  Shaun Murphy and his dog Sparky ona Vego scooter in Adin, California. Shaun Murphy and his dog Sparky ona Vego scooter in Adin, California.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, where are you off to next? MURPHY: Now, we’re trying to make it just on cow power to Chicago. Once we hit Chicago, hopefully, successfully, just on the cow stuff, we go to Iowa. And I have to travel across Iowa using only fuels derived from grain, so that might be ethanol, switchgrass electricity, anything that’s prairie fuel. CURWOOD: Shaun Murphy, the Eco-Trekker, is heading east on his journey to travel the U.S. using sustainable vehicles. Thanks for joining us. MURPHY: Thanks Steve, nice chatting with you, mate. [MUSIC: Guerrero “Black Sheep Blues” LOOSE GROOVES AND BASTARD BLUES (The Orchard – 1999)] Related link:

Emerging Science Note / Mitigating C02[SCIENCE NOTE THEME] GRABER: The air pollutant ozone is known to harm human health and be toxic to plants. Now, it looks like ozone can also damage soil. Researchers in Michigan conducted an experiment on two groups of forests. One was sprayed with carbon dioxide. The other got a mix of carbon dioxide and ozone. In the stand of trees exposed to both carbon dioxide and ozone, the ozone reduced the ability of the soil to capture and store carbon dioxide by half. That’s significant because some scientists say the increase in carbon dioxide from greenhouse gas emissions can be lessened if absorbed by forests. But according to this new research, plants and soils that live in areas with high levels of ozone may be significantly less able to clean the air of CO2. In the upper atmosphere, ozone protects against ultraviolet radiation. But ground-level ozone forms as the result of a reaction between chemicals from burning fossil fuels and from industrial processes and sunlight and warm temperatures. It’s found at high levels in many parts of the U.S. and around the world. Given the new research, nations may have to re-evaluate their strategies to combat global warming. That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Cynthia Graber. [MUSIC: Mu-Ziq “Brace Yourself Jason” LUNATIC HARNESS (Astralwerks - 1997)]

Ducks UnlimitedCURWOOD: Because hunters need places to go hunting they have become some of the nation’s biggest land and wildlife conservationists. And when these hunters band into organizations their technical expertise and financial and political clout can have a considerable impact on the environment, even if others who identify themselves as environmental advocates prefer to get their meat from the butcher, or don’t eat meat at all. Producer Will Kilburn has this profile of one hunter group called Ducks Unlimited. [WATER SPLASHING; MEN TALKING] KESSLER: If you have an extra set of hands, you can hand me some of those decoys there… Set a couple more blacks up on this side, and leave a hole right in front of us. Put a couple of blacks down in that area. [WATER SPLASHING] CUSHMAN: Duck hunters like to tease one another… [WATER SPLASHING] CUSHMAN: Doesn’t look like he’s ready. [WATER SPLASHING] KESSLER: Put the finishing touches on getting ready here. CUSHMAN: So, where all the birds? KESSLER: Don’t start already. KILBURN: Craig Kessler and John Cushman are setting out wooden decoys in Great South Bay, Long Island, just a few dozen miles east of Manhattan. Both men are in camouflage. Kessler’s boat is covered with bunches of grass. KESSLER: This is the grass that was cut from a different spot. See this taller stuff here? As you get into the upper part of the marsh, there’s this shorter stuff which is called patens, which is this stuff here. Being that I’m the king of camouflage, I want everything to look real natural. KILBURN: The effect is convincing, at least to human eyes. The boat seems to melt into the scenery--in this case, a group of low, grassy islands, on the sheltered side of the barrier beaches which protect the Island’s southern shore from the Atlantic. Kessler lays out the plan for the day. KESSLER: First of all, there’s lots of ways you can hunt ducks. But we’re hunting over decoys today, which is the classic way of doing it. You could walk around the marshes quietly, in the hopes of flushing some up – that’s called jump shooting. You can do that. You can try to get in a flight line where they’re going and do what’s called “pass shooting” which is, hopefully, to get some to fly by you in the right spot. But hunting over decoys is the classic way of hunting ducks. Because what you’re doing is sort of relating to the birds’ behavior in a very direct fashion. KILBURN: Both Kessler and Cushman are experts in duck behavior, but only partly because of their interest in hunting them. Cushman volunteers as the New York state vice chairman for the conservation group Ducks Unlimited, while Kessler works full-time as a biologist for the group – making this, for Kessler at least, a day at the office. KESSLER: So, if everything works absolutely perfectly, which it will not, the ducks would come around, they’d see our decoys, we’d call to ‘em, they’d set their wings, they’d sail down to try to join this flock of resting birds and they’d come right down in front of us. Which would give both John and I a good close shot, a killing shot, and that’s what you’re trying to do. You’re trying to respect the game so you’re not crippling it or shooting it at ranges where it’s beyond the capabilities of the gun and those kinds of activities which do give sportsmen a bad name. KILBURN: Ducks Unlimited was born in at a time when sportsmen, by and large, didn’t have a bad name: 1937, after vast amounts of waterfowl habitat were lost during the drought years of the Dust Bowl. The group now has close 700,000 members and has conserved more than 10 million acres of land from the Arctic to the tropics. Along the way, things changed. Hunting became stigmatized by many, and Kessler says development, not drought, is now the big enemy of waterfowl habitat. KESSLER: There are fewer ducks because there are fewer places for them to go, but even if the ducks were packed in here…the entire shoreline of Long Island was marshland. There were tens of thousands of birds that were living in areas that are just no longer available any more. It was not uncommon to go out and see 5 or 10,000 of those birds moving around they bay, diving down to the bottom, and as the bays have deteriorated in quality, the food resource has gone down.  A Gadwall hen and one of her ducklings.(Photo: © USFWS) A Gadwall hen and one of her ducklings.(Photo: © USFWS)

KILBURN: Part of the problem, the houses which take up almost every inch of this very expensive shoreline. But even the few unbuilt areas are a long way from a truly natural state. The spot where Kessler and Cushman lay out their decoys, for example, is next to a wildlife refuge and several large islands which are scarred by mosquito ditches, damage which Ducks Unlimited and other groups are working to undo. [WALKING THROUGH THE MARSH; RUSTLING] KILBURN: One place that healing process is taking place is here on Plum Island, one of the jewels of the Massachusetts coastline north of Boston. Ducks Unlimited biologist Grace Bottitta explains that the marshes went through not one, but two rounds of ditching. First, by farmers in colonial times so that they could grow salt hay for their livestock, then again during the Depression. BOTTITTA: In the 1930’s, throughout the Atlantic Coast, freshwater and saltwater systems were ditched because they thought that mosquitoes bred in all types of water that sat on the marsh surface. They thought the best way to get rid of the mosquito breeding area was to drain the marsh, and the folks through WPA got paid by the linear foot to ditch the marsh, and as many ditches as you could fit in, that’s what they did. KILBURN: But Bottitta says the mosquitoes didn’t cooperate. BOTTITTA: In the beginning, it worked very well. It drained almost all of the water off the marsh surface. But what it also did is it drained the fish habitat so the fish that used to eat the mosquito larvae are no longer on the marsh surface. So, what you now have is an area that the mosquitoes can still breed in because they only need a couple inches of water for just a couple of days, so you’re giving the mosquitoes a predator-free area. So, they actually do really well now. So after 30, 40 years we’ve realized that that’s not working out, so the technique now is to restore the open water back on the marsh surface. KILBURN: Bringing that saltwater back in, Bottitta says, will not only restore animal diversity, but also bring diversity back to plant life as well…something that Ducks Unlimited and other groups will monitor over the long term. KESSLER: Before each restoration we collect data on the health of the marsh – vegetation, fish use, bird use, invertebrates, soil salinities, dissolved oxygen content of the water, temperatures of existing waters, if there are any there. And then, after the restoration, we do the same type of stuff to make sure we were doing what we thought we were doing to the marsh. Sometimes you can do it for a year or two afterwards, with the intention of doing it every 10 years, 20 years, kind of rechecking on things. KILBURN: So, does this mean that once duck numbers rebound on Plum Island, that duck hunters will be back, as well? No. Hunting isn’t allowed anywhere on the island which is part wildlife refuge and part residential neighborhood. Plum Island is actually typical of the group’s work these days, despite a common misperception that they only preserve areas that can be used for hunting. Group officials say that an increasing number of its members don’t hunt. Just as tellingly, Ducks Unlimited now often works with partners who you might think would shy away from the group’s long association with hunting. JONES: We don’t hunt on our properties, but that wasn’t the issue here. The issue was to create habitat for waterfowl, shorebirds, and also upland species, grassland birds that are dependent on the fields that we were planting, so hunting wasn’t really a concern. KILBURN: Andrea Jones is a bird conservation biologist with the Massachusetts Audobon Society. The group is working with Ducks Unlimited on a coastal restoration project in the southeastern part of the state. She says there wasn’t really any controversy about the collaboration. JONES: I think they’ve done great work and they’ve done more than, perhaps, any other conservation group to protect wetlands. We’ve chosen through the span of our organization, which is about 102 years old, not to allow hunting in our sanctuaries but it doesn’t mean we’re anti-hunting as an organization.  (Photo: © Ducks Unlimited) (Photo: © Ducks Unlimited)

[WATER SPLASHING; KESSLER AND CUSHMAN TALKING] KILBURN: Ducks Unlimited biologist Craig Kessler agrees that hunting and conservation aren’t mutually exclusive, if you think about it. KESSLER: The hunting issue as it relates to wetland habitat preservation is really a very important ingredient because waterfowl, as a group of birds, as a group of animals, has probably been studied, managed, for more than any other animal on the face of the earth. And there’s that hunting interest that has basically driven that. The hunters have been concerned about preserving waterfowl habitat since the 1930’s. People that are out here in kayaks birdwatching now - I’m not necessarily taking anything away from them - but for them to take a negative bent on hunting, and just consider that it’s a bunch of guys out wanting to spit and curse and kill everything that moves is really not an accurate picture at all about what hunting is all about and what it’s meant to the waterfowl resource. KILBURN: At the end of the day, Kessler’s prediction of duck non-cooperation has come true. There’s not a bird in sight. The tide is too high, the sun too bright, and the air-- a brisk 40 degrees or so--too warm for the ducks to leave their sanctuary in search of food. But Kessler’s not disappointed. KESSLER: That’s actually one of the more rewarding – believe it or not – rewarding aspects of duck hunting, as opposed to some of the other hunting, like pheasant hunting, for example. You could walk all day and never shoot a pheasant, or even kick one out, so you don’t even get to see the quarry that you’re after. And with waterfowling, unless you’re in a really bad spot, you’re usually gonna see waterfowl, and it’s that anticipation that, perhaps, they’re gonna come your way, maybe this one’ll come close enough. It gives you some degree of satisfaction even if you don’t actually get ‘em. At least you’re out there, enjoying what’s out here, not only the camaraderie of it but the other sights and sounds. [DUCK CALLS] KILBURN: Ducks Unlimited biologist Craig Kessler, calling in vain to the ducks who chose not to take part in this story. [LOUD SQUAWKING DUCK CALLS] KILBURN: For Living on Earth, I’m Will Kilburn, on Great South Bay, Long Island. [LOUD SQUAWKING DUCK CALLS] Related link:

Leaves & LivesCURWOOD: They’re on their way out, the leaves. Once green and glorious they fall to carpet the earth and then return to it. They are truly leaving and turning – the maple and birch and cherry and oak into red and yellow and gold and brown. They are decidedly deciduous and in places where foliage flourishes, the center of an annual experience. Producer Bob Carty has this sound montage he calls, “Leaves and Lives.” [RUSTLING SOUND OF DRY LEAVES] CHILD 1: …I’m going to do a belly flop. CHILD 2: Me, too. CHILD 1: Do it Mom, make a big one. Mom, here’s some over here! MOTHER: How’s that? CHILD: Good! [JUMPING INTO PILE OF LEAVES; SHOUTING, OHHH!; LAUGHTER] CHILD: When we jump in it’s sort of crumbly. [CHILDREN SHOUTING, SQUEALING] CHILD: There’s only a certain time of the year, one season, October, when they fall. It’s the only time of the year when we get to play with them [CHILDREN SHOUTING, “WOO HOO!”; JUMPING IN LEAVES ] CHILD: I’m getting more leaves on the rake than I am on the pile. MOTHER: It’s pretty big. CHILD: Now, let’s jump in it. CHILD: No, it’s not ready yet, there’s still a lot more to go. We want to have the biggest pile… CHILD: I like burying myself, and then when people come by I can, like, pop out. And then you take a pile and throw it at your sister. [RUSTLING LEAVES] CHILD: Please stand clear of the raking grounds. Please stand clear. [CHLD SCREAMING; LEAVES RUSTLING] FEMALE: My most special part of the day is walking with the kids to school. And this time of the year it’s very special, because we go walking along kicking the leaves. [WALKING THROUGH RUSTLING LEAVES] FEMALE: And lot’s of time during our day, our day is so busy and so full that we don’t have time to really talk to each other. But right now these days we walk along, and kick the leaves, and talk. Walk along, kick the leaves, and talk. [METAL SCRAPING: LEAVES RUSTLING] FEMALE: There’s the compulsive raker who rakes the first leaf and waits for the rest of the leaves to fall and rakes them as fast as possible. Then there’s the fifty leaf at a time guy. He’s the one who leaves the rake on the porch and goes out and rakes little piles and leaves them on the grass so they can blow all over again. Then there’s the guy who waits for it all to dump and rakes it all at once, and puts it in bags to get rained on [LAUGHTER]. And then there’s us [LAUGHTER]. We’re the “if God wanted leaves to be raked he wouldn’t have made them fall from trees.” [LAUGHTER]. [WHIRRING OF LEAF BLOWER MOTOR] FEMALE: One morning I was woken up, woken from a really deep sleep to a monotonous, rrrrrrrrrr. And you’re like – what is that? You go out and there’s some idiot, and they have to be idiots, using one of those leaf blower things. Like, why would you want to do that? FEMALE 2: Too bad, is what we say. We don’t just have the blower that blows them. We have the mulcher. It’s fabulous. I have the largest tomatoes ever – ever – and I think it has a lot to do with that leaf blower mulcher thing. [WHIRRING OF MOTOR] FEMALE 2: How is raking romantic? It’s you and a stick. How is that romantic? [METAL SCRAPING] FEMALE: I remember once I made this huge pile. It seemed huge, anyhow. And I dove into it and ten seconds later this other fellow that I had a huge crush on leapt into the very same pile. And he parted some of the leaves away and took my face in his hands and gave me this big kiss under the leaves. And there were other people on the street but they couldn’t see what was going on under the leaves. So every time the leaves start to turn I remember that kiss from Valerian. We were six. [CHILDREN SHOUTING; LAUGHING; LEAVES RUSTLING] FEMALE: I have always kind of mixed feelings about fall and the colors, because the colors are so absolutely beautiful they always just take my breath away. But also, it’s my birthday around fall, and I’m always aware of the undertow of winter and the passage of time, and the idea of death. And I guess, you know, you can just take it to another level and just say that we all want to go out in one great big flash of great light. But it’s always bittersweet. I’m not afraid of death, but I feel melancholy with the passage of time and how quickly it is going by. [MUSIC: I miss you, most of all, my darling, when autumn leaves start to fall…. [RUSTLING SOUND OF DRY LEAVES] CHILD 1 : …I’m going to do a belly flop. CHILD 2: Me too. CHILD 1: Do it Mom, make a big one. Mom, here’s some over here! MOTHER: How’s that? CHILD: Good! [JUMPING INTO PILE OF LEAVES; SHOUTING, OHHH!; LAUGHTER] [MUSIC: Anne Downey (trad) “Cold Frosty Morning” ] CURWOOD: Our sound portrait: “Leaves and Lives” was produced by Bob Carty. [MUSIC UP AND UNDER] ]

CURWOOD: And for this week - that's Living on Earth. Next week – the story of how community activists from some of California’s most polluted neighborhoods have demanded and won a say in the way the state handles its environmental problems. MALE: So you're seeing these folks working together and you’re drafting a very, very difficult document. That's when I saw things started to change that it wasn't you know, the usual suspects leading the process. CURWOOD: A new voice in California environmental politics – next time, on Living on Earth. And between now and then you can hear us anytime and get the stories behind the news by going to livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth.org. [MUSIC ] [LOW GUTTURAL TRILL OF BIRDS] CURWOOD: We leave you this week with a Petrel duet. [GUTTURAL TRILL STARTING AT LOW PITCH AND RISING UP; INTERMITTENT PEEPS] CURWOOD: Lang Elliot recorded these two sea birds of the North Atlantic as they called to each other on Kent Island in the Bay of Fundy. [GUTTURAL TRILL STARTING AT LOW PITCH AND RISING UP; INTERMITTENT PEEPS] CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. You can find us at livingonearth.org. Our staff includes Carly Ferguson, Liz Lempert, Nathan Marcy, Susan Shepherd, James Curwood and Tom Simon. Al Avery runs our website. Our interns are Rebecca Griffin, Kathy Lutz and Wynne Parry. Special thanks to Ernie Silver. Alison Dean composed our themes. Environmental sound art courtesy of EarthEar. [GUTTURAL TRILL STARTING AT LOW PITCH AND RISING UP; INTERMITENT PEEPS] CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening. ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes form the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and Stonyfield Farm: organic yogurt, cultured soy, and smoothies. Ten percent of their profits are donated to support environmental causes and family farms. Learn more at Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from NPR member stations and the Annenberg Foundation. ANNOUNCER 2: This is NPR, National Public Radio. Living on Earth wants to hear from you!Living on Earth Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth! NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

|