January 23, 2004

Air Date: January 23, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

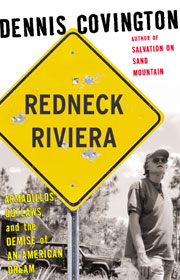

Redneck Riviera

View the page for this story

PART 1: Every summer, Sam Covington would take his family on vacations to the Florida coast. It was the one time when he could leave behind the cares and responsibilities of his Alabama upbringing. Later in life, he decided to buy up a piece of that paradise and wound up investing in River Ranch Acres – a two and a half acre plot of undeveloped land which ultimately turned out to be a real estate scam. He never set foot on his land, and yet it was the one thing he left to his son, Dennis, when he died. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Dennis Covington about his new book, "Redneck Riviera: Armadillos, Outlaws, and the Demise of an American Dream," and about his quest to reclaim his father’s land.

PART 2: Dennis Covington’s story continues, as he explains the lengths he undertook to secure his inheritance. To stake his claim from a band of gun-toting members of the local Hunt Club, he set up camp on River Ranch Acres. Little did he suspect that it would take more than a revolver and born-and-bred Alabama gumption to change the ways of the Florida land. (23:47)

The State of the Environment

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

The environment was conspicuously absent from the President's State of the Union address. But Washington correspondent Jeff Young tells us Congress will address major environmental issues in the coming weeks, from energy and highways to toxic waste cleanup. (05:30)

Emerging Science Note/Rice Roads

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on how rice could become a key ingredient for cutting down road noise. (01:20)

()

The Ritual Uses of Mercury

/ Cynthia GraberView the page for this story

Mercury has been used for thousands of years in medicine. The metal has even been ascribed magical properties. Today, though, it's known for its toxicity. But the use of mercury in ritual has persisted in some communities here in the U.S. Living on Earth's Cynthia Graber reports. (14:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

This Week's Music

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Dennis CovingtonREPORTERS: Jeff Young, Cynthia GraberNOTES: Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR - this is Living on Earth.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. When Dennis Covington was growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, summertime meant heading to Florida to a place the locals fondly called “The Redneck Riviera”. Dennis inherited a piece of Florida from his father, but when it came time to claim his birthright Dennis found he had to wrestle the land away from a group of bellicose squatters.

COVINGTON: At night I would dress in black, and put lampblack under my eyes. And armed with my revolver and my shotgun, I would cut the fence, and make my way into my little canvas house, where I would stand guard all night, waiting for somebody to appear out of the palmetto leaves and beg to be shot.

CURWOOD: The battle for River Ranch Acres - this week on Living on Earth. Also, ritual use of the toxic metal mercury, and a preview of environmental politicking on Capitol Hill. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Redneck Riviera

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, welcome to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

This week, we explore the story of a father’s legacy to his son. Two and a half acres of undeveloped land in Florida’s interior, where even owners with deeds to the land are kept at a distance by a band of gun-toting squatters. It’s a story of a stubborn and unyielding culture, of a son’s determination, and, ultimately, of who will inherit the land.

Dennis Covington is the son who inherits his father’s dream, and goes to reclaim this small patch of paradise. He has written a book about his quest called “Redneck Riviera: Armadillos, Outlaws, and the Demise of an American Dream.” He teaches creative writing at Texas Tech University, and joins me now. Dennis Covington, welcome.

(Photo: Jim Neel) ![]()

CURWOOD: Where exactly is the “Redneck Riviera,” and how did it get its name?

COVINGTON: That’s a ticklish question. I wanted to put a footnote to the title, because I wanted to say in the footnote, this is not a book about the Alabama Gulf Coast. In my part of the country, Redneck Riviera refers to the Alabama Gulf Coast, particularly a stretch between Fort Morgan east to a lounge called the Floribama, which sits on the Florida/Alabama line. The big event at the Floribama is an annual mullet toss on the beach.

CURWOOD: A fish, you mean.

COVINGTON: Yes, a fish toss. The term, I believe, was coined by Kenny Stabler, who was a quarterback for the University of Alabama, later the Oakland Raiders. In retrospect, though, I see that there are a number of Redneck Rivieras. I know people in Florida sometimes refer to the Florida Panhandle as the Redneck Riviera. And that’s how I use the term when I’m reminiscing about the family vacations we had on the Florida Panhandle at Laguna Beach. But I actually believe that there is a new Redneck Riviera that’s not on the coast. And it is in the very center of Florida, along the Kissimmee River in this defunct subdivision called River Ranch Acres.

CURWOOD: I want to get to the River Ranch Acres in just a minute. But first, at the center of this story -- though he’s not physically present for most of it -- is your father? Right, Sam Covington? And for years, he took you to the ocean, but you write that the generations of Covingtons before your father’s had never even seen the ocean. Why do you suppose he was driven to pile you guys into, what, a station wagon, and head down to the ocean year after year?

COVINGTON: For his generation, a Florida vacation was a step up in life, you know. But the book itself, for me, was kind of a probing into the reasons why it had such an effect on him. Because he was not interested in social status, really, at all. I think it had something to do with a sense of openness and spaciousness, and I believe that he sought that out in recognition of his own smallness in the face of the creation, which is immense.

CURWOOD: By the way, how did you travel down to Laguna Beach, where you went in the Florida Panhandle? And how did your folks handle the driving?

COVINGTON: We went down in a normal sedan, a passenger car. Dad bought them used. The first new car he bought was a 1959 Chevy Impala…

CURWOOD: With those fins?

COVINGTON: With those fins that curled down like wings.

CURWOOD: Yeah.

COVINGTON: And it was bright red, fire engine red. My dad was colorblind, and for that reason mother didn’t want him taking my older sister car shopping with him, because she knew that dad would come home with something like that. But going down to Florida– in Birmingham, the red lights were rather conventional: the red light was on the top, the green light was on the bottom. But there were towns in south Alabama where that was reversed. The green was on top and the red was on the bottom. So my dad ran stoplights all the way to Florida.

CURWOOD: Paint the picture for me when your family would pull up to the beach there. What would happen?

COVINGTON: The first thing my dad would always do was to charge down the dunes and dive headlong into the surf. This always terrified my mother. You know, she would scream from the highway “watch out for the undertow,” “you’re going to have a heart attack.” And he would emerge triumphantly and tell us to “come on in, the water was warm and fine.” Of course it was cold, and everything. And late in life, when he and my mother would come with my wife and I down, even though he had emphysema – he was in , you know, declining health – he would still race down the beach like a man possessed and dive into the Gulf of Mexico.

CURWOOD: Eventually, your father decides to look south for a piece of what you call the American dream. And this all starts when he receives an invitation to a dinner and a presentation at the local Holiday Inn. Dennis, I’m just wondering if you could read from the part of your book about his drive home after that dinner?

COVINGTON: Sure, Steve.

|

|||

|

|

“On this drive, I imagined that Dad was in a hopeful, satisfied mood. I have known such times myself when the world, despite the beating it has given you, relents for just a moment while you dream your exotic, defiant dream. Life won’t take all of you, by God. You will salvage something from this mess and call it your own. It will be your private garden, the place where your imagination can play.

In my father’s case, it was two and half acres of this land he had never seen except in photos, but was now tempted to buy from a salesman named Ray Chase after a dinner at a Holiday Inn. Dad had never met Mr. Chase before, but the salesman seemed to understand exactly what Dad wanted. An investment, they would call it. Inwardly, both men must have winked at the word. It would be inappropriate for me to speculate about what Mr. Chase thought of my Dad. Surely, he had met many such men on his journeys back and forth across America. A generation of men who had come of age during the Great Depression, made their leap to the middle class, survived the second great war of the century, raised their children, moved into their final house, and now, in their early fifties, dreamed of possibilities beyond the practical demands of keeping a family afloat. Like Dad, they had played by the rules, stuck with the company, paid their taxes, bought life insurance, burial policies, savings bonds, their first new cars. And now they stood poised at that most powerful and vulnerable time of life when the major financial obligations had been met, but the great journey toward death has not yet fully begun. And the cracks that are beginning to show beneath the feet, the rumors of ill health, the decline of sexual vigor, serve only to propel the dreamer faster and further toward the cry of the one on the far ridge who has seen that elusive and ineluctable something that has until now been missing in life. River Ranch Acres. In retrospect, I think his buying the property at River Ranch was just a logical extension of all those red lights he had run on the way to Florida. Dad was never happier than he had been on our family vacations to Laguna Beach. Maybe he thought he could buy back that happiness for good.” CURWOOD: River Ranch Acres. Now, this little piece of promised paradise was the brainchild of a pair of brothers, Jack and Leonard Rosen, I understand, from Baltimore, Maryland. How did they dream up this scheme? COVINGTON: Jack and Leonard Rosen were former carnival barkers who made their fortune in the cosmetics business by advertising Formula Number Nine on television. The lanolin contained in this concoction was supposed to grow hair. But the cosmetic business was kind of souring on them, and they got word that there was a lot of cheap land in southwest Florida and a lot of money to be made. So they bought some acreage, subdivided it, and promised to build a city there, a city called Cape Coral. They made a lot of initial money on the sales and they ploughed that money back into developing home sites. But then they got the idea that the second time around they might go easier on the development, not develop it so much. They made a huge profit, but all they had were roads into the next development. By the time they got to River Ranch Acres, they had dispensed with the notion of developments at all. They divided the land into one and one quarter acre parcels -- but they had no intention of bringing power in, or sewage, or water, and no intention of putting roads in. In fact, they had a deal with the commissioners of Polk County that they would not bring roads in, because if there were roads then the county would have to maintain them. So the county kind of looked the other way and let them sell this land to unsuspecting, mainly northerners, or people like my father. And they reaped an enormous profit. They bought the land for around 150 dollars an acre. They sold it for 1,000 dollars an acre. And the only improvements they made were to build a showplace kind of lodge and western saloon, so that when people got there they would have a sense that they were in on the beginning of something grand. CURWOOD: Now, your father never set foot on this land, right? COVINGTON: Not on his parcel. CURWOOD: Didn’t have the curiosity to go out and take a look? COVINGTON: Didn’t have the means. Didn’t know where it was. It’s a hard place to find, a little two and a half acres in the middle of essentially nowhere. CURWOOD: So your dad never sees this, you never see it. I mean, this sounds like a lot of problems with this land. But at the end of your father’s life, despite all these problems, he goes over to the courthouse and sets it up so that you can inherit this land. Why do you think that was? COVINGTON: That’s the great mystery of the book, and I have my guesses now, having gone through this experience. Dad was a stickler for details, and also a great admirer of justice. He really believed that dishonesty among men was an aberration. And he had bought this land, he had paid taxes on it every year, and it had been taken over -- along with the rest of the 40 thousand acre development -- by a hunt club, in what my dad thought was an illegal fashion. They posted armed guards at the only gate, they charged people to join their club and enter for the purposes of hunting. And they discouraged, and sometimes forcibly prevented, legitimate owners from entering. I think my dad wanted me to have an adventure in his place. CURWOOD: And you were pretty easy for the bait, I take it, huh? COVINGTON: It had to percolate for a while, you know? And I think what happened was that I started reaching that age that Dad was when he bought the land in the first place. And I started needing that same kind of sense of infinite space and a place of one’s one, you know? What I wanted to do was build a little retreat down there: a little cabin, and have a well, a solar panel. And I’d take my family down for wilderness vacations. But in order to do that sort of thing, I had to wrestle the land away from the hunt club. CURWOOD: We’re talking with Dennis Covington, author of “Redneck Riviera: Armadillos, Outlaws, and the Demise of an American Dream.” He’s been telling us the tale of his quest to reclaim his inheritance in Florida’s wild west territory. We’ll here more from him, and about his run-ins with the local hunt club there, in just a minute. I’m Steve Curwood. Stay tuned to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Dave Matthews Band “#34” UNDER THE TABLE AND DREAMING (BMG Music - 1994)] CURWOOD: Welcome back to Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. We’re back with Dennis Covington, author of “Redneck Riviera: Armadillos, Outlaws, and the Demise of an American Dream.” He’s also written the book “Salvation on Sand Mountain.” But we’re talking about your troubles that you encountered in the course of writing this book. At this point, you take off south to reclaim your inheritance in the middle of River Ranch Acres, which is, well, quite a far cry from the western style retreat that its brochures had promised. What did you find when you got to River Ranch? COVINGTON: River Ranch was a mess. The land had hundreds and hundreds of shacks, trailers, some more elaborate homes, you know, very nice. But all of these structures were erected illegally, on other people’s land, on land like my father’s. When I finally did identify my father’s two and half acres, there was nobody squatting on it; but on much of the other land there was. CURWOOD: I’d like you to read for us about the point when you finally set up camp on your father’s land there on River Ranch Acres. It’s the eve of the hunting season, and you’ve rigged up a small canvas tent. COVINGTON: “I hadn’t anticipated the terror I’d feel, sitting alone in the canvas house. While on the ridge above me a thousand hunters gathered to wait for dawn and the start of the general gun season. Campfires flickered through the trees, and there was an occasional burst of practice rounds followed by whoops of triumph or derision. I imagined I was on some Civil War battleground – Antietam, the night before the sunken road, the cornfield, the piles of corpses, the defeat. Most of that night I sat cross-legged on the bunk with a machete in my lap, waiting for the enemy charge. But at some point I fell into a deep, mind-numbing sleep, and didn’t wake until full light. I was puttering outside the cabin, warming up beany-weanies on my camp stove, and occasionally catching the chatter on my CB radio. I wore an orange deer hunter’s cap and had tied an orange flag to the antenna of the Jeep. If they wanted to shoot me, they couldn’t claim they didn’t know I was there. That afternoon I sat at the writing desk I had made and took some notes. When the light began to fail I turned on my Coleman battery operated lantern. All day there had been shots nearby, but I hadn’t worried much about them until I heard some that sounded much too close for comfort. About 20 yards from the cabin a handful of men were drinking beer and shooting into the palmetto, apparently at nothing in particular. They looked like the kind of men that hung around the Mirees’ campfire. Hog hunters in half-soled rubber boots and grimy work caps. They were chewing tobacco, and the laughter after they spit had something familiar to it, a sharp, malicious edge. They were like my people back in Alabama and maybe that’s what scared me the most. I waited until they finally moved farther on the road, then I took my time cleaning up the place, so they wouldn’t sense my urgency in case they happened to be watching secretly from the palmetto breaks. I zipped up the door of the cabin, but otherwise left it as it was, the Coleman lantern burning at my writing desk. Then I cranked up the Jeep and drove to the nearest motel, the Indian Lake, to spend the night. I’d probably been a fool to spend the night before the opening of hunting season in a canvas cabin with a machete in my lap. I wasn’t going to be twice a fool by staying there over a Saturday night. “ CURWOOD: What happened the next day when you returned to this camp? This camp that was there to claim your inheritance, your dad’s inheritance. He had left you this land. COVINGTON: I got there at first light. I noticed that there were two bullet holes right by the door. One of the bullets had gone through the canvas and exploded the Coleman lantern. The other bullet went through, missed the lantern, but there was a lot of debris in the cabin. I got the distinct impression that somebody was trying to kill me. CURWOOD: So, they shoot up your camp this time. You pack up your bags and split? What do you do? COVINGTON: Well, I did what any other self-respecting Alabama boy would have done. I bought two parcels of land for back taxes on either side of my property, so I would be sure to let them know that I had no intention of going anywhere. And then I bought a gun. I’d never owned a gun before. I didn’t know anything about them. But I’d go out there and I’d target practice. And, you know, they stopped shouting insults at me anyway, and threats. But in my absence it was shot up again. And somebody, whoever had perpetrated this, had left a dead armadillo in the center of the cabin. It was known among the hunt club membership that I had a particular affection for armadillos. CURWOOD: And at this point you’ve had enough now. COVINGTON: Yes, I did. I kind of went crazy. I became a kind of insurgent, I suppose. There was no entry point other than the hunt club gate. At night I would dress in black and put lampblack under my eyes, and, armed with my revolver and my shotgun, I would cut the fence and make my way into my little canvas house where I would stand guard all night, waiting for someone to appear out of the palmetto leaves and beg to be shot. I never saw anybody. But it gave me a sense, at least, of having done something to protect the property. CURWOOD: I mean, it seems like a pretty simple and straightforward idea that if you own land you can claim it. Why was this such an impossible idea on the River Ranch Acres? COVINGTON: One of the problems there was that the power structure within the county was intertwined with the hunt club itself. There were some members of the sheriff’s department that were members of the hunt club. And the attorney for the hunt club was the president of the Florida Bar Association, a close friend of the Governor. So in a way you had a kind of good old boy network. The hunt club saw the legitimate owners of land in River Ranch as being, you know, essentially suckers. And they were characterized as being from up north somewhere and they’d never come down there anyway. So, I believe that it was that protection that a subculture has for its own that prevented outsiders like me from coming in and claiming what was rightfully ours. CURWOOD: What did it take for you to finally put this to rest? COVINGTON: Ultimately, I stopped cutting the fence when I came upon an accident on the way to Lake Wales. Two horses had gotten out of their paddocks, and a car had hit one of them and killed the horse, and injured the driver of the car. And I realized in that instant that there’s a reason for fences, and that it’s wrong to cut them, no matter what the circumstances are. And so I decided that, you know, maybe that’s not what Dad wanted me to do anyway. Maybe he had something different in mind. And I started thinking about his love of the west, his need for open space. So I went out to Idaho and found a parcel of land out there, and bought it. And I brought with me my dad’s workshop that he had built in his back yard 30 years before. I erected it on a hill overlooking a beautiful valley and a view of the mountains. CURWOOD: What is it about the need to own land, do you think? Because, at this point, it seems that you’ve moved beyond just wanting to take back your father’s property. COVINGTON: I’m not sure whether it’s a guy thing or not, but I do believe that the territorial imperative is built into us biologically. Now, having said that, this book, for me, is sort of an exploration of one of the ultimate questions of literature, western literature. And that is, who inherits the land? Finally, I, of course, believe that it belongs to all of us and that the private ownership of land in America is kind of an anomaly, kind of a strange thing that’s happened as a result of the legal system we inherited. Nonetheless, it’s part of us, and wars over land have been with us since antiquity. So, I wanted a piece of land out in Idaho so that I could sit in the middle of the desert and listen to the coyotes. CURWOOD: I have one final question, and that has to do with a point that you bring up in “Redneck Riviera,” which is this: sometimes the good part of a story is not even in the story. Sometimes the good part is what’s been left out. So tell me, looking back on your experience and what brought you there, what is the good part of your story? COVINGTON: The good part of the story that I’ve just told happened at a moment when I had just decided to go claim my father’s land that he had given to me. And I had bought a GPS device, a global positioning system. And I was testing it out and I happened to be in front of my home, my house, in Birmingham. And I could see one of my daughters rehearsing a scene from “Grease” that she and the neighborhood kids were going to put on. At the other window I good see my older daughter at the Internet, at the computer. And then my wife came out of the door to let the cats out and I saw only her hair, which was shining in the sunlight. And I initialed that device by calling that place home. And then I walked inside. CURWOOD: Dennis Covington is author of “Redneck Riviera: Armadillos, Outlaws, and the Demise of an American Dream.” Dennis, thanks so much for speaking with me. COVINGTON: Thank you. Take care. [MUSIC: Ry Cooder “Theme from Southern Comfort” MUSIC BY RY COODER (BMI/Venice Boulevard Music – 1981)] Related link:

The State of the EnvironmentPRES. BUSH: America this evening is a nation called to great responsibilities, and we are rising to meet them. (fades under track) CURWOOD: President Bush delivering his State of the u=Union address as lawmakers returned to the Capitol for the new session of Congress. Our Washington correspondent Jeff Young joins me now to tell us about environmental items to watch. Jeff, welcome. YOUNG: Thank you, Steve. CURWOOD: Now, I was listening to the president for word on the state of our environment and I didn’t hear that much. What about you? YOUNG: Well, we didn’t hear it because, for the most part, it wasn’t there. Bush aides say there just wasn’t room for it in a 55 minute speech. Democrats said, well, you know, he found room to talk about steroids and pro sports, so what gives? Florida Democrat Bob Graham concluded, "If I had Bush’s environmental record I wouldn’t want to talk about it either." The president did make this one brief but meaningful mention of energy policy. PRES. BUSH: [APPLAUSE] Consumers and businesses need reliable supplies of energy to make our economy run. So I urge you to pass legislation to modernize our electricity system, promote conservation, and make America less dependent on foreign sources of energy. [APPLAUSE] YOUNG: Now, the energy bill kind of ran out of steam last year when several conservative Republicans joined a filibuster because of the bill’s cost. And there was some talk that the president’s support might waver. But that line in the speech sent a message the White House is still willing to fight for this bill. CURWOOD: And how is that fight shaping up? The bill’s supporters need what, just two more votes to break that filibuster? What are the odds of that happening? YOUNG: Well, we’ll see. But if it takes too long to get those two votes, what we’ll also see is a lot of pressure to pull this bill apart and move its more popular items separately— say, for example, the tax credits for ethanol. One unpopular item is the energy bill’s biggest stumbling block, and that’s the liability protection for companies that make MTBE—the gasoline additive that contaminates groundwater. The shield against lawsuits is very controversial but Republican House leaders insist on keeping it in there. And taking it out is the only way to get the bill passed, according to the Senate’s leading Democrat, Tom Daschle. DASCHLE: I have said that I am quite positive that I could produce anywhere from four to six additional Democratic votes if they would take those provisions out. So I believe the ball is in their court. I’ve made the offer; there’s nothing else I’m able to do until they take the action. YOUNG: Now, this is of course election year, and the energy bill is a political problem of sorts for Senator Daschle who’s in a tough reelection race. Here in Washington, most of his party hates this energy bill. But in South Dakota, his home state, farmers love it because it doubles the use of ethanol and they grow the corn that makes ethanol. So Daschle’s making sure that if energy fails, he’s not to blame. CURWOOD: If people are surprised by the energy bill’s price tag, Jeff, they might have some real sticker shock when it comes to the transportation bill that’s coming up. I saw that there’s, what, 300 billion dollars proposed to build highways? And I’m thinking, with that much spent on new roads you’ve got to have some environmental impacts. What are the major concerns here? YOUNG: It is expensive. Environmentalists think it’s too much money for roads and not enough for mass transit. The spending ratio is about four to one in favor of highways, and they’d like to see more money spent on things like light rails projects and bus lines. They’re also worried about the bill’s so-called "streamlining" of environmental reviews in highway planning. That would relax some requirements for road builders to account for things like the extra air pollution from traffic. Now to some, that sounds more like steamrolling than streamlining. But the big battle with transportation is going to be that cost, how to pay for it. It’s a big-ticket item, we’re in a time of deficits, and this bill will either mean another nickel a gallon in the gas tax, or more money coming out of general revenues. And either way, this is where some environmentalists might pick up some unexpected allies—conservative Republicans who are very hawkish on the budget and fed up with these bloated spending bills. We saw this with the energy bill when it got costly, and I expect we’ll see it again in the transportation debate: conservatives and conservationists finding some common ground when it comes to money. CURWOOD: Yeah, money, money, money. And look at Superfund. Now that doesn’t seem to have any money. This is the program that supposed to pay for cleaning up toxic waste sites. What’s going to happen there? YOUNG: Well, it’s already falling short. A recent inspector general report found that funding shortfalls last year prevented action on 11 Superfund sites and caused changes in others. And these are some of the most polluted places in the country. Most people expect that the polluting companies should pay for that—that’s something called the “polluter pays” principle. But a Superfund fee from industry has expired, and President Bush shows no interest in bringing it back. Democrats like Barbara Boxer of California want to reestablish that fee and make President Bush pay a political price. BOXER: American taxpayers should not have to carry this burden alone. Superfund Trust Fund is empty today, that is bad news for the people. We have to make sure the American people understand that this administration is the first one – the first one – to actively oppose a “polluter pay” principle. YOUNG: Now, another toxins issue to watch for is an effort to rein in asbestos lawsuits. Asbestos, of course, is a carcinogen. Workers exposed to it have won some massive court settlements. And manufacturing and insurance companies want Congress to kind of bail them out here with a federal trust fund to pay for asbestos victims. Labor doesn’t like it so expect to see a big fight with some big guns here, all of them fighting just as-best-as they can, as I like to say. CURWOOD: [Laughs] Okay, thanks for that update. YOUNG: You’re welcome, Steve. CURWOOD: Jeff Young is Living on Earth’s Washington correspondent.

Emerging Science Note/Rice RoadsCURWOOD: Just ahead, find out how you can join me for an adventure on safari in Africa. First, the Note on Emerging Science from Jennifer Chu. [SCIENCE NOTE THEME] CHU: When the rubber hits the road, highways can get pretty noisy for residents who live near them. Researchers in Japan are working on a way to cut down on road noise. Their solution: just add rice. Or more specifically, rice bran, the brown layer found between the husk and the grain. This layer, combined with grain, is what we call brown rice. Up until now, the bran has been thrown away, or used as cattle feed. Now there’s another option. Scientists have found that mixing and heating the rice bran with resin, then adding it to asphalt, makes for some promising pavement. The rice and resin mixture acts as a light and porous material. During tests, scientists discovered these rice-based roads absorb 25 percent more noise than regular asphalt roads. There’s one more advantage: since the rice mixture is porous and flexible, it can filter through and more easily drain away water. In the long run, this could prevent cracks and potholes from forming. Highway analysts say this method is similar to one employed in the U.S. Instead of rice, states like Arizona, California and Texas use ground-up rubber tires in their asphalt to cut down on road noise. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Jennifer Chu. CURWOOD: And you're listening to Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the World Media Foundation Environmental Information Fund. Major contributors include the Town Creek Foundation and the Wellborn Ecology Fund. Support also comes from NPR member stations and Bob Williams and Meg Caldwell, honoring NPR's coverage of environmental and natural resource issues, and in support of the NPR president's council. And Paul and Marcia Ginsburg, in support of excellence in public radio. [MUSIC: Barnstorm “Normal Guy” BARNSTORM (Weedrocks.com - 2000)]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood and coming up: the use of mercury in cultural rituals. But first, check your calendar and see if you can join me May 1st to go on a safari to some of the wildest places in Africa. Sometimes the wildlife viewing can be sensational. On one recent outing, our ranger took us up to an area where cheetah had been spotted earlier. Cheetah, the king sprinter of predators, are highly endangered, and now number only in the hundreds in the wild. Creeping up through the bush in a Land Rover we couldn’t see any cheetah, but we could see a lone impala making her way ahead of us. Then, low in the grass we spotted one cheetah, then two, then three. A mother out hunting with her adolescent cubs, our ranger explained. The mother started stalking the impala and then broke off. “You do it,” she seemed to nod to one of her youngsters who took up the hunt, inching slowly towards the impala who seemed unaware of the impending danger. I wanted to shout a warning but I knew I shouldn’t interfere. Suddenly, like a shot, the cheetah took off and the impala sprinted away. A few moments later the cheetah had the impala by the neck. It was a harsh reminder that it is nature’s plan to eat and be eaten, and we’re a part of it. I can’t promise that we’ll see a cheetah hunt during our Living on Earth safari to Kruger National Park and the Wild Coast of the Indian Ocean, but I do know that if you come you will see something that you’ll never forget. There are two ways you can be a part of our eco-tour, conducted by Heritage Africa. Win a trip for two or make sure you have a spot by buying a ticket right now. For details go to our website, livingonarth.org. That’s livingonearth.org for a chance at the trip of a lifetime. [MUSIC]

The Ritual Uses of MercuryCURWOOD: Mercury has played a role in human culture for thousands of years. It’s the only metal that’s a liquid at room temperature. People have long attributed medical, or even magical, powers to it. But its ability to harm the human brain has been known for more than a hundred years. Probably the most famous example is the “mad hatter” from Alice in Wonderland – “mad” because he worked with mercury. Scientists and advocates alike have sought to remove mercury from the food we eat and the air we breathe. So health workers in the Boston area were surprised when they found out that the idea of a beneficial mercury has persisted in some communities. Living on Earth’s Cynthia Graber reports. [CHATTER OF ELDERLY VOICES, SPEAKING IN SPANISH] GRABER: Seniors fill a community room in downtown Lawrence, Massachusetts, a former mill town about an hour northwest of Boston that’s now 80 percent Latino, mostly Dominican. Doris Anziani heads up a local environmental health group called Casa de Salud that offer regular “charlas,” or chats, such as the one here today. At one charla last spring, Anziani spoke about the risk of mercury from incinerators and from certain kinds of fish. She mentioned that there’s mercury in thermometers. After she spoke, another Casa leader approached her. ANZIANI: When she thought about that she said, “ooh, I’ve seen something else that looks like the liquid that’s inside the thermometer.” So we were asking her, “what is it?” “It’s in a capsule, and it’s sold at the botanicas. It’s called azogue.” GRABER: Botanicas are stores that sell all sorts of Afro-Caribbean products: rosaries, saints, candles and perfumed water, and herbs. Anziani discovered azogues is another name for mercury.

ANZIANI: Then we came back to the Casa leaders and they were familiar with the mercury. People use it for these purposes. And we’re like, “okay, we need to do more research here. I think we’re not just being contaminated by the incinerator. I think we’re contaminating ourselves by using these products in our homes.” GRABER: Casa de Salud was founded by JSI, a group that does health research and training around the world. After their initial investigation, Anziani and her supervisor at JSI created a questionnaire to find out just how many people were using mercury in their homes. Community members, including teenagers, went around Lawrence, talking to people at home, in botanicas, in beauty salons and barbershops.

|