SKULASON: Well we're down at the Reykjavik harbor, this is of course one of the biggest harbors in Iceland. And one of the biggest users of fossil fuels in Iceland is the fishing fleet.

SKULASON: Well we're down at the Reykjavik harbor, this is of course one of the biggest harbors in Iceland. And one of the biggest users of fossil fuels in Iceland is the fishing fleet.

GRABER: Skulason stands by a row of trawlers docked in the harbor. They range in size from a small blue vessel that might go to sea for a few days, to 300-ton trawlers that stay for weeks.

Iceland's seafood is known the world-over. The nation exports around two million tons a year, accounting for about 70 percent of its gross domestic product. But this fishing fleet runs on imported and expensive diesel fuel, and is responsible for a third of the island’s greenhouse gas emissions.

SKULASON: Fish is, of course, has been the groundwork for the economy of Iceland for a very long time. And that's one of the locations where we think we can apply hydrogen if we want to become a hydrogen society is to have the fishing fleet running on clean energy carrier like hydrogen.

GRABER: Iceland was the first country to discuss the need for converting its fishing fleet to running off hydrogen. Soon after, number of maritime nations joined the effort. But it won’t be easy. Skulason says hydrogen fuel cells for trawlers will have to overcome a whole new set of problems.

SKULASON: There’s a lot of salt in the atmosphere, which is not very good for fuel cells. Boats don't come into harbor every day. And like buses and cars and vehicles and so on, they can go to the same refueling station everyday. But ships are out at sea for a few days or many many weeks.

GRABER: Once again, the hydrogen problem comes down to storage. Storage in metal could work on big trawlers that can carry the load. Another option is to use large and powerful fuel cells – the kind used now at stationary locations. These operate at very high temperatures but the extra heat could provide steam to power a ship’s frozen fish storage. There’s also talk of storing natural gas on trawlers and reforming it into hydrogen on board.

[CLANKING ON TRAWLER]

GRABER: Skulason hopes to have at least some of these solutions worked out so that in a few years he can put a hydrogen demonstration project on a trawler. He says Iceland is the perfect place for this research.

SKULASON: We don't built cars in Iceland, we don't build car engines or anything. But we build ships in Iceland, and we have a lot of knowledge about shipping and construction of ships. So we are quite convinced that Icelandic know-how can be applied in the maritime applications for hydrogen. And therefore that could be a technological development, even create jobs and know-how in Iceland, which could be valuable to other countries. But financing projects currently and overcoming technical obstacles is a challenge, which we are tackling at the moment.

[PEOPLE SHOUTING, MAN SPEAKING INTO MICROPHONE AT ANTI IRAQ WAR DEMONSTRATION]

GRABER: A few blocks from the harbor, the office of Iceland’s Prime Minister is the site of a protest against the war in Iraq. Eighty percent of Iceland’s citizens oppose the war, so their government’s decision to back the U.S. is unpopular here.

Another unpopular government decision involves its plans to build a huge dam in the middle of a pristine wilderness. The dam would power a new aluminum smelter. Iceland’s metal industry emits a third of the nation’s greenhouse gases. And because of its smelters Iceland was granted an exemption to actually increase emissions over 1990 levels in exchange for its signature on the Kyoto Protocol.

One vocal opponent of the smelter is the Iceland Nature Conservation Association. The group is also critical of the government’s hydrogen project. Spokesperson Arni Finnsson calls it a diversion, a greenwashing tactic to make the government look like it’s doing something about emissions from cars, boats and smelters when it’s not encouraging the purchase of efficient vehicles, which could reduce emissions now. Finnsson says hydrogen cars are a good idea but too far off.

FINNSSON: We're talking of 20 years maybe, 15-20 years. And look, your administration, we can't put off, you know, actions to stop climate change by ten, fifteen, twenty years under the pretext that we're doing research and have good plans for hydrogen. That's impossible.

GRABER: This criticism does not surprise President Ólafur Ragnar Grimsson. He doesn’t respond to the question of how his government might promote cleaner forms of transportation now. Instead, he looks ahead to the promise that hydrogen holds.

GRIMSSON: And I would ask the question, does, or can the world afford to have the hydrogen project far into the future? Isn't it of great need, even pressing need, for the total global environment, to have the hydrogen project as a viable option here and now, as quickly as possible?

GRABER: President Grímsson admits he may not live to see this project completed. It could take fifty years, and it won’t be a simple task. As we’ve heard throughout this story, even if it’s possible to build a hydrogen economy here in a country where it seems a natural fit, it will be a long and costly venture.

But Hjelmar Arnason, a member of parliament who’s played a major role in pushing the government to back the hydrogen project, tells me that Icelanders have a knack for overcoming technical challenges. They did it once before, weaning themselves off coal and tapping hydro and geothermal power to heat and light their homes and businesses. In the process, Iceland went from one of the poorest to one of the richest nations in the world.

Even though, Arnason says, some sacrifices had to be made along the way – like not disturbing the elves, ghosts and other spirits that according to Icelandic lore lurk on the landscape.

ARNASON: There are roads, even here in the neighborhood of Reykjavik. Comes in a straight line. Then all of a sudden it takes a U-turn around a small stone, I mean a big stone. Because the experience was when the constructors went there with all the big bulldozers and machines they broke down, repeatedly. So the conclusion was we have to respect the elves living in there.

So that's - I love this, it's part of our culture, our history and heritage. We believed. Before, we had light and electricity. You need to know that here in the north, nine months we have very dark months. So light from electricity is very important to us. But before we had that, it was this darkness. And in the darkness all this creativity of imagination came and we had all kinds of ghosts, elves and other creatures.

GRABER: In Iceland imagination can make roads curve, and it may help an entire nation say goodbye to oil and gas and find a way to fulfill the promise of hydrogen. Arnason says Iceland will show the world - in particular the United States - what is possible.

A clear day in downtown Reykjavik (Photo: Chris Ballman) A clear day in downtown Reykjavik (Photo: Chris Ballman)

ARNASON: Two-thirds of our emissions here in Iceland is from transportation and fishing. So that's where our sins are basically. So that's why we want to attack those sins and implement this new technology in transportation and the fishing fleet, and by that, reduce our emission down two-thirds. So that's a lot. And we will be the leading nation, as you in the states are in other fields. We will be in that. But you can come up and follow up, be our guest.

GRABER: For Living on Earth, I’m Cynthia Graber in Reykjavik, Iceland.

[MUSIC]

CURWOOD: Our special, “The Promise of Hydrogen” continues in just a minute with a look at how hydrogen could meet energy needs here in the United States. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and The Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12; The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, making grants to improve the health and health care of all Americans. On the web at r-w-j-f dot o-r-g; The Annenberg Foundation; and, The Kellogg Foundation, helping people help themselves by investing in individuals, their families, and their communities. On the web at w-k-k-f dot org. This is NPR -- National Public Radio.

[MUSIC]

Related links:

- University of Iceland

- National Hydrogen Association Back to top

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. And our topic this week is the Promise of Hydrogen.

Now, so far in our program we’ve heard how the tiny nation of Iceland is positioning itself as a leader in the science, technology and politics of making the switch from a fossil fuel to a hydrogen economy. But there are projects here in the U.S., too, that are ushering a revolution in energy use.

Small fleets of hydrogen cars are already cruising the streets of Washington D.C., Los Angeles and San Francisco as test models. And the state of California is preparing a string of fueling stations for hydrogen vehicles. American companies are also manufacturing fuel cells to power not just vehicles, but commercial buildings and homes – even laptops and cell phones.

President George W. Bush has noted this coming Hydrogen Age, saying it could mean cleaner air, fewer greenhouse gases and less reliance on foreign oil.

BUSH: We import over half of our crude oil stocks from abroad. And sometimes we import that oil from countries that don't particularly like us. It jeopardizes our national security. If we develop hydrogen power to its full potential, we can reduce our demand for oil by over 11 million barrels per day by the year 2040.

CURWOOD: Joining me to talk about what role hydrogen may play in the nation’s energy future is Amory Lovins, who heads the Rocky Mountain Institute, an energy think-tank based near Aspen, Colorado.

Now tell me, what are the relevant differences, if any, between the United States and Iceland?

LOVINS: (LAUGHS) Just about everything is different. Iceland is a small country with a fairly homogenous and ancient culture. It has very rich geothermal and hydroelectric resources. Not much energy use. But the United States is equally rich in renewable energy resources, even though it’s a big, diverse, young country.

Certainly we have plenty of opportunity to run all renewable and all hydrogen if we want. Just the attractive wind-power resources in North and South Dakota could make as much hydrogen as the world makes now – that’s about 50 million tons a year. And if our highway vehicles were feasibly and profitably efficient that would be enough to run all our highway vehicles.

CURWOOD: That’s a big if, of course.

LOVINS: Well, it’s not all that difficult. Cars and light trucks and even heavy trucks have been designed already with spectacularly greater efficiency. The round number is that you can save a factor of five or six on your light vehicles, and about a factor two on your heavy vehicles – both very profitably compared to present wholesale gasoline prices.

CURWOOD: So you’re saying it’s pretty easy to get a car that’s five or six times as efficient as what people are driving today?

LOVINS: Yeah. And the key is not just to mess with the engine – that only gives you a factor two or so – but to start by making the car half the weight, giving it lower aerodynamic drag and rolling resistance, which is the energy that goes into heating the tires and road. So you reduce by three-fold the power needed to run the car.

Of course, when you make the car three times more efficient by working on its physics, then whatever you’re propelling it with gets three times smaller. This means, for example, that you have a three-times-smaller fuel cell, if you’re going to hydrogen, so you can afford to pay three times as much per kilowatt. So you can adopt fuel cells many years earlier before the prices come down.

Moreover, your storage tanks for the hydrogen get three times smaller, so they fit conveniently and leave plenty of room for people and cargo. Therefore you don’t need any breakthroughs in storage – the tanks on the market will do the job.

CURWOOD: Well if ordinary processes can get to such high efficiencies, why should we be thinking about hydrogen at all?

LOVINS: Because it’s very versatile. You can make it from any hydrocarbon or carbohydrate, or any other source of energy. Nuclear electricity, renewable electricity, whatever. Generally, making it out of electricity is quite expensive, and we don’t do it that way – 96 percent of our hydrogen is made from natural gas. And that will go on, I think, being the cheap method for a long time.

But it’s possible, for example, that it may be very cheaply make-able from coal -- using coal basically to pull hydrogen out of water and then take the resulting carbon dioxide and keep it from going in the air. Some serious analysts think that will also be profitable -- which would mean a long climate-safe future for the coal industry, and they would like that idea.

CURWOOD: Indeed.

LOVINS: Then, hydrogen of course releases nothing bad when you use it. You can burn it in an engine or turbine very efficiently. Companies like Boeing and Airbus have looked seriously at liquid hydrogen powered airplanes, cryoplanes, because liquid hydrogen is incredibly light – that’s why they use it in rockets. It has about the density of medium styrofoam. And they concluded that actually such planes would be feasible, and would be safer than today’s aircraft in a crash.

The use in buildings would be typically through fuel cells, which are about twice as efficient as engines. And generally, whether it’s in a building or a car, a well-designed system for using hydrogen will be two or three times as efficient as using a hydrocarbon fuel to do the same job by normal means. That’s why it’s worth paying a lot more per unit of energy for hydrogen than for fossil fuels, because you can get more work out of it.

That means, in turn, that the hydrogen in our hydrocarbons is probably worth more without the carbon than with the carbon – even if nobody will pay us for keeping the carbon out of the air. So this is actually an attractive future for oil and gas companies as well.

CURWOOD: This is I think a point of contention, though. Other folks say, hey, if you use natural gas, oil or coal to generate hydrogen, in fact you’ve got to do something with this carbon. And the technology is not there yet to keep the carbon out of the environment.

LOVINS: That last part is true. There are a number of ways being developed for keeping the carbon out of the air. Some of them are being tested; I wouldn’t say any of them is yet proven.

But if you, for example, pipe natural gas through the existing pipes to a gasoline filling station where you’ve installed a new gizmo, called a “miniature reformer,” that will turn it into hydrogen -- half extracted from the natural gas, half from steam – and then pump the hydrogen into the tanks of fuel cell cars; even if you release all that CO2 into the air, it’ll be two to six times less CO2 per mile than you’re releasing right now in your gasoline car.

So it’s, I think, a very reasonable stop on the way to the hydrogen economy. And it’s a lot more climatically responsible than what we’re doing. It will also reduce your fuel cost per mile from roughly five cents to something around three cents.

CURWOOD: So, let me see if I understand your vision then of the United States. We’re going to create hydrogen from fossil fuels…

LOVINS: Typically natural gas, and directly not through electricity.

CURWOOD: … and that this will have less of a burden on such issues as climate change and ground level pollution than the present system. Even, say, going with very efficient hybrids?

LOVINS: Yes.

CURWOOD: Now tell me, looking ahead to this hydrogen economy, how do we move it around? How do we move the hydrogen from one place to another?

LOVINS: Typically, we will be producing the hydrogen at the filling station. Filling stations serving about 90 percent of our cars have natural gas piped to them right now. If they can get very cheap electricity, which they also can get through the grid, it’s conceivable that in some situations they might be able to make competitive electricity that way. But I think that’s a lot less likely. Electricity is an awfully expensive way to make hydrogen. So I think natural gas will continue to rule.

This, by the way, will not use more natural gas. It may sound like, gee, we’re already short of natural gas. How can we also make it into hydrogen without running out faster? Well, the reason is that, meanwhile, you would be saving natural gas at power plants displaced by the electricity made by fuel cells; at refineries, where you’re using it to make gasoline and diesel fuel displaced by fuel cell vehicles; and in buildings, where you’re using it in furnaces and boilers displaced by waste-heat recovered by fuel cells in the building.

So when you work out all the balance, it turns out the hydrogen transition doesn’t use more natural gas, and may well use less.

CURWOOD: Okay, let’s say for a moment that we adopted this plan. You say we need ultra-efficient cars, and this is a way that the U.S. gets going with the hydrogen economy. What will be the infrastructure costs here to do this, say, over the next 35 years you suggest we could do this?

LOVINS: Oh, probably a few tens of billions of dollars. The hundreds of billions you commonly hear is clearly exaggerated. It’s based on making hydrogen centrally and building a complete new pipeline infrastructure to pipe it everywhere. I don’t think there’s any reason to do that, it doesn’t make sense.

You also need to net out the investment you’re not making in sustaining the oil-fueling infrastructure. And it turns out that oil is more capital-intensive upstream than gas is, and that the miniature reformers are probably cheaper and more efficient than centralized ones, which was a bit of a surprise.

So when you work all this out, you find you’re probably saving hundreds of dollars per car on the whole infrastructure for creating and delivering the fuel into your tank if you choose hydrogen rather than gasoline, and do an apples-to-apples comparison of investments required on both sides.

CURWOOD: Now, some people who work in the energy field don’t think that future cars will all run off hydrogen. They say, look, what about getting fuel from biomass, agricultural byproducts, or even crops specifically grown to produce fuel.

LOVINS: Mm-hmm.

CURWOOD: How do you see that fitting into our future energy needs?

LOVINS: These are all competitors. And in fact, in our study “Winning the Oil Endgame”, we’re looking at how they all interplay, and which ones have how much of the market in the long run. And I think the answer is going to be that they’ll all be active. We are already seeing a lot of biodiesel and other bio-fuels emerging in the market.

Those processes are getting steadily better. What they will tend to do, just like what hydrogen will tend to do, is squeeze out oil. Because these alternatives -- whether in saving oil or substituting for it -- tend to have rising reserves and falling costs, whereas oil tends to have falling reserves and rising costs. And the curves are starting to cross.

You know, I’ve been looking at the history of the American whaling industry. And before Drake struck oil in Pennsylvania in 1859, whaling had peaked two years before that and was already headed down. Not because there weren’t more people wanting to light their houses, but because the whale oil price had been high enough for long enough to elicit fatal competitors. In this case, kerosene and town gas, both made mainly from coal.

Basically, the whalers ran out of markets before they ran out of whales. And the remaining whales were saved by technological innovators and profit-maximizing capitalists, who came up with better, cheaper ways to light your house. Now this came as a great surprise to the whaling industry because apparently nobody had added this stuff up – saying here’s what’s on the market, here’s what’s in the lab, and then there’s that guy over there Thomas Edison who’s working on electric light. And if you kind of look at that whole picture, the future for whale oil doesn’t look very good.

I think we’re at that stage now for oil. The things we do with it, we’re now realizing we can do better and cheaper without it. These hadn’t been added up before. But I think when you do, investors will start reallocating their assets, hedging their bets, and realizing they can make more profit at less risk following an impeccable business case for getting off oil.

CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit about the politics of the promise of hydrogen. President Bush mentioned it in a State of the Union address. Some people said that he was saying this to avoid dealing with other parts of the question of climate change. What’s your analysis of the interest of the government and hydrogen?

LOVINS: It’s impossible to tell from the outside whether the intention of the federal hydrogen program is sincere. And I expect that would depend on which people you’re referring to in the program and in its senior guidance. The trouble is the administration has this self-inflicted wound of having done its best to block any significant improvement in light vehicle efficiency, and meanwhile held out the long-term vision of hydrogen.

So I think environmental groups have gotten suspicious of the program for several reasons. One is, who’s in favor of it is not their traditional allies. And second, I’m afraid that the administration’s opposition to short-term gains in fleet efficiency creates the suspicion, worthy or unworthy, that hydrogen is meant as a distraction or a stall rather than a compliment to short-term fleet efficiency.

A sensible policy would of course go for both. We would make fleets dramatically more efficient by accelerating the turnover of the capital stock. We would reward people for buying efficient vehicles and scrapping inefficient ones. And there are ways to do that that are revenue-neutral, and very good for the industry. They get to sell more cars and they’ll make more money.

CURWOOD: Umm —

LOVINS: But that isn’t how we’ve approached it. You know, we’ve had instead the assumption that efficient cars will be unattractive to the buyer because they’ll have trade-offs and compromises. So you need government intervention via either mandatory standards or fuel taxes to get people to buy these undesirable vehicles. And we’ve been gridlocked over twenty years on which of those two instruments to choose.

CURWOOD: Thinking back to where we started, which was looking at the Icelandic experience, what’s your grand vision for the U.S. energy economy thirty, forty, fifty years from now?

LOVINS: If we led always to save or produce energy, compete fairly at honest prices --regardless of whether they’re on the supply or demand side, what kind they are, how big they are, and who owns them – we will end up with a very efficient, diverse, dispersed, renewable energy system. And I suspect that hydrogen may well emerge as the dominant energy carrier over the coming decades.

CURWOOD: Amory Lovins is the CEO of the Rocky Mountain Institute. Thanks so much for taking this time with me.

LOVINS: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Gus Gus “Anthem” GUS GUS VS. T-WORLD (4AD Records – 2000)]

Related links:

- Fuel Cells 2000

- U.S. Deptartment of Energy: Hydrogen, Fuel Cells & Infrastructure technologies Program

- Rocky Mountain Institute Back to top

CURWOOD: And for this week – that’s Living on Earth. You can learn more about the move towards hydrogen and see pictures of Iceland on our web site. The address is livingonearth.org. That’s livingonearth dot o-r-g. You can reach us at comments@loe.org. Once again, that’s comments@loe.org. Our postal address is 20 Holland Street, Somerville, MA, 02144. And you can call our listener line anytime at (800) 218-9988. That’s (800) 218-9988.

[HONKING GEESE, RUSTLING FEATHERS, SPLASHING WATER]

CURWOOD: And for this week – that’s Living on Earth.

Before we go, one last stop on the island of fire and ice. In the center of Iceland’s capital, Reykjavik, there’s a pond where each day young and old alike come to feed the geese, ducks and assorted fowl that inhabit the waterway. Here’s what it all sounds like on a typical morning.

[BIRD CALLS, WATER SOUNDS UP AND UNDER]

CURWOOD: Our special, The Promise of Hydrogen, was produced by Cynthia Graber with help from Chris Ballman. Our engineers are Paul Wabreck and Nal Terro. Special thanks to Ernie Silver and Carl Lindermann. Al Avery runs our web site. Alison Dean composed our themes. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science; and Stonyfield Farm – organic yogurt, cultured soy, and smoothies. Ten percent of their profits are donated to support environmental causes and family farms. Learn more at Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from NPR member stations, the Ford Foundation, for reporting on U.S. environment and development issues, and the Oak Foundation, for coverage of marine issues.

ANNOUNCER: This is NPR, National Public Radio.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea. Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment. The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs. Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

|

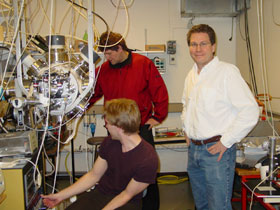

Iceland’s President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson with reporter Cynthia Graber and producer Chris Ballman

Iceland’s President Olafur Ragnar Grimsson with reporter Cynthia Graber and producer Chris Ballman  Bragi “Professor Hydrogen” Arnason in his lab at the University of Iceland in Rekjavik with reporter Cynthia Graber (Photo: Chris Ballman)

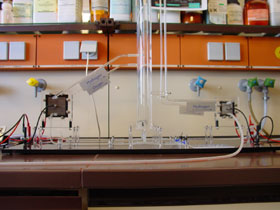

Bragi “Professor Hydrogen” Arnason in his lab at the University of Iceland in Rekjavik with reporter Cynthia Graber (Photo: Chris Ballman)  Professor Arnason’s hydrogen fuel cell demonstration model (Photo: Chris Ballman)

Professor Arnason’s hydrogen fuel cell demonstration model (Photo: Chris Ballman)  One of Iceland’s Hydrogen buses receives its weekly maintenance checkup. (Photo: Chris Ballman)

One of Iceland’s Hydrogen buses receives its weekly maintenance checkup. (Photo: Chris Ballman)

The fishing fleet at Reykjavik harbor (Photo: Chris Ballman)

The fishing fleet at Reykjavik harbor (Photo: Chris Ballman)  A clear day in downtown Reykjavik (Photo: Chris Ballman)

A clear day in downtown Reykjavik (Photo: Chris Ballman)