September 3, 2004

Air Date: September 3, 2004

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bush on the Environment

View the page for this story

In the waning days of George W. Bush’s first term, Living on Earth takes a look at his administration’s environmental record. The president has said that he hopes to be remembered for his respect towards the natural world, as well as for his material progress. His supporters credit him with many of the environmental achievements he put through as governor of Texas. His critics say this administration has been the worst for the environment in history. (12:45)

Protecting Public Lands

View the page for this story

As the Bush administration nears the final days of its first term, we take a look at how the president has dealt with the country’s public lands. The roadless issue has dominated much of the talk surrounding federal territory, and we first talk with Reed Noss, professor of conservation biology at the University of Central Florida, about the ecological impact of roads in national forests. These areas are battlegrounds for various interests, including environmental groups, timber companies and local economies, and we turn next to Lynn Scarlett, from the Department of Interior, for the administration’s perspective on just how its roadless proposal will play out. We’ll continue the segment with a look at the national parks and the $5 billion dollar maintenance backlog that’s plagued the Park Service for several years. Bill Wade, spokesperson for the Coalition of Concerned National Park Service Retirees, tells host Steve Curwood many of these parks suffer from inadequate staffing, poor facilities, and low visitor turnout. (15:00)

Emerging Science Note/Nature’s Way

/ Jennifer ChuView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Jennifer Chu reports on how playing outdoors may alleviate symptoms of attention deficit disorder. (01:20)

How Green Goes the Sunshine State

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Could green issues decide the presidential race in Florida? Some environmental and Democratic groups think so and are waging major campaigns aimed at conservation-minded voters. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young looks at the issues that have gained political traction, from the plight of the Everglades to the threat of coastal oil drilling. (15:00)

This week's EarthEar selection

listen /

download

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve CurwoodGUESTS: Reed Noss, Lynn Scarlett, Bill WadeREPORTER: Jeff YoungNOTE: Jennifer Chu

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From NPR, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BUSH: We want to be remembered for our material progress, no question about it. But we also want to be remembered for the respect we give to our natural world.

CURWOOD: Going into the final phase of the election, Republicans say voters who care about the natural world should take a close look at the environmental record of George W. Bush.

CONNAUGHTON: Is the air cleaner? Is the water purer? Is the land better protected? Are we doing a better job of managing the taxpayer resources that we spend to achieve environmental protection as we move forward into the next century?

CURWOOD: Supporters of Mr. Bush say you have to answer “yes” to those questions, but the president’s opponents couldn’t disagree more.

KENNEDY: It’s the worst administration in American history without any rival on the environment, and the Reagan administration was really bad.

CURWOOD: The environment, the president and the election - this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NPR NEWSCAST]

Bush on the Environment

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

[THEME MUSIC]

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios in Somerville, Massachusetts, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

As the presidential campaign enters its final phase, we’re taking a look at the record of President George W. Bush on the environment -- and we’ll start with his own words. Mr. Bush didn’t talk a lot about the environment during his recent speech at the Republican convention in New York, but it certainly merited his attention.

|

|

CURWOOD: When President Bush spoke in the Adirondacks on Earth Day in 2002 he was less than half way into his term, but he had already begun to rewrite some of the nation’s leading environmental laws. And here’s how he described his environmental goals: BUSH: We want to be remembered for our material progress, no question about it. But we also want to be remembered for the respect we give to our natural world. CURWOOD: Supporters say the president came into the White House after a number of environmental accomplishments as governor of Texas. During Mr. Bush’s years as chief executive of the Lone Star state, they say he boosted spending on natural resources and cut toxic and power plant pollution. And if there’s one thing that President Bush would like the public to remember about his environmental record, it could easily be what he calls the Healthy Forest Initiative. In the face of devastating wildfires in the West, the Bush administration designed this forest management program to reduce the threat of those wildfires while “upholding environmental standards.” STRASSEL: It comes from many, many years of mismanaging our forests. CURWOOD: Kim Strassel is a senior editorial writer for The Wall Street Journal. STRASSEL: The General Accounting Office estimated not long ago that one-third of our national forests are dead or dying. Healthy forests was bipartisan -- it passed both the Senate and the House with decent majorities. It got a lot of support, especially from Western Democrats, because they recognize the problem out there. And I think in the end it was a very reasoned proposal. CURWOOD: Supporters also give Mr. Bush high marks for a proposed billion dollar hydrogen car research program designed to reduce pollution as well as our dependence on foreign oil. Another addition to this list of accomplishments, according to Los Angeles Times environmental reporter Elizabeth Shogren, is the Bush administration’s move to cut emissions from diesel engines. SHOGREN: That’s a big area where the Bush administration, I think, can take a lot of pride in having a big impact on the air into the future and making it healthier for people everywhere in the country. CURWOOD: The president generally prefers to use a free market approach to environmental protection, rather than strict regulation. Take, for example, his Clear Skies Initiative. This White House says this plan calls for reductions in three major air pollutants by 70 percent, and saves consumers millions of dollars at the same time. BUSH: We will set mandatory limits on air pollution with firm deadlines, while giving companies the flexibility to find the best ways to meet the mandatory limits. CURWOOD: One way to use this approach is to set a cap on overall pollution for an industry and allow businesses to buy and sell their allocations of pollution permits. Letting the market set the agenda also avoids government subsidies and seeks to lower market barriers. Kim Strassel of The Wall Street Journal says this approach has many advantages over standard environmental regulation: STRASSEL: We have thirty years of environmental improvement that came from mandates – that, basically, came from laws that came and said you can’t do this, you can’t do this, you can’t do this…and they have worked to a degree. Now, are there ways to actually improve environmental performance and improve the economy at the same time; is there a new way of thinking about how we can manage the environment? This idea of free market environmentalism is one such approach. CURWOOD: But others say Mr. Bush’s interpretation of the free market approach isn’t working. For example, they claim his Clear Skies Initiative will add another two decades of pollution to the skies before the market incentives start to clear the air. Among the critics is Robert F. Kennedy Jr., author and attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Mr. Kennedy charges that while the Bush administration talks about using the free market, in fact, it does just the opposite. KENNEDY: You show me a polluter, I’ll show you a subsidy, and I’ll show you a fat cat who is using political clout to escape the discipline of the free market and force the public to pay his production costs. CURWOOD: Mr. Kennedy’s new book, “Crimes Against Nature,” is a polemic against the Bush White House which, he says, is dishonest about its environmental agenda. He and other critics say that President Bush is relaxing regulations but not cutting subsidies to industries or making them pay for cleanup. Critics also cite what they call hundreds of environmental rollbacks, claiming that Mr. Bush is using free market environmentalism to eviscerate decades of environmental reform. KENNEDY: It’s the worst administration in American history without any rival on the environment, and the Reagan administration was really bad. CURWOOD: Mr. Kennedy notes the Bush team came into office and quickly established an energy task force under the leadership of Vice President Dick Cheney, the former CEO of Halliburton, a major oil and gas service company. The membership and much of the proceedings of the task force have remained secret, but its recommendations have been put into action. Early on, the White House pulled the U.S. out of the international treaty called the Kyoto Protocol, to cut gases that lead to climate change. The task force then recommended heavy use of coal, one of the most concentrated sources of gases that promote global warming. It also promoted more nuclear power and drilling for oil in the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge. Other policies have drawn criticism as well. SHOGREN: One example that has to do with what the Bush administration is doing to relax protections has to do with mountaintop removal mining. CURWOOD: Again, Elizabeth Shogren of the Los Angeles Times. SHOGREN: And this is the process where they take the tops of mountains off and take the coal out of it. And the Bush administration has made several moves to keep this process going, despite efforts through the courts to reduce this kind of mining and scale it back. CURWOOD: Some of the president’s other controversial moves have to do with pollution from coal-fired power plants, which is linked to thousands of excess deaths each year from tiny particles of ash that people breathe. The White House called for weaker limits on another dangerous pollutant from those power plants: mercury. The administration also relaxed regulations and settled court cases that would have required the oldest, dirtiest power plants to install new pollution control technology. The president plans to replace these regulations with a free market approach that would allow plants to trade pollution credits. But critics say these new initiatives will end up substantially delaying and weakening pollution controls under the Clean Air Act. Critics also say these clean air issues point to a fundamental problem with the administration’s free market approach. And that is -- the free market doesn’t work when industry officials are writing the laws. Again, Robert Kennedy Jr.: KENNEDY: There is no stronger advocate for free market than myself. I believe that the free market is the most efficient and democratic way to distribute the goods of the land, but there is a huge difference between free market capitalism, which democratizes our country, and the kind of corporate crony capitalism, which has been embraced by this administration. CURWOOD: Mr. Kennedy and others say industry has too much sway with regulators, in part because former company officials are now pulling the levers of regulation and enforcement. They cite the case of Jeffrey Holmstead, a former lobbyist and lawyer who, in his old job, fought the EPA over air pollution enforcement. Mr. Holmstead is now a key decision-maker on air pollution enforcement, having been appointed EPA’s Assistant Administrator for Air Policy. Vermont Senator Patrick Leahy has been one of the most outspoken critics on, what he calls, these conflicts of interest. LEAHY: You see how the Bush administration strategically placed industry lawyers in key positions in EPA who spent the last three years helping some of the biggest utility companies in the country getting off the legal hook of putting pollution controls in their plants. They put the fox in to guard the hen house. CURWOOD: But The Wall Street Journal’s Kim Strassel says it doesn’t make sense to keep industry veterans like Jeffrey Holmstead out of the regulatory process. STRASSEL: Environmentalists constantly like to talk about the stake-holder process, about how they want to be involved, and how the administration should be making decisions with them, and I agree with that. But I think if you’re going to have that approach, you have to have everyone involved – you have to have the people on who these regulations are going to be inflicted on too. CURWOOD: Still, some observers say that the sheer number of former industry executives, lobbyists, and lawyers who hold key positions within regulatory agencies is without precedent in modern times. Other names frequently mentioned are J. Steven Griles, now Deputy Secretary of the Interior, and a longtime mining industry lobbyist and official, and Gale Norton, now Secretary of the Department of Interior, who formerly worked with property rights groups, the paper industry’s lobbying group, and represented a leading petroleum company. And there are others with resumes similar to Mr. Holmstead and Griles and Ms. Norton. Again, Elizabeth Shogren of the Los Angeles Times. SHOGREN: A lot of them are lobbyists, a lot of them are lawyers who worked on behalf of industry, directly on behalf of industry, so these people were very aware when they came into office what kind of policies the industry wanted. CURWOOD: And she thinks the extent of this practice is unique to this administration. SHOGREN: The president’s father, the first President George Bush, had a very different sort of cadre of top appointees in the environmental agencies. The people who headed his agencies were like William Riley, who headed the EPA, and he was somebody who was well known as an environmentalist. Critics also say the Bush administration ignored science in the debate about the Clean Air Act and setting standards for mercury. And this criticism has been particularly loud from the hallways of science itself about a whole range of issues, on everything from snowmobiles in national parks, up to the status of science in climate change. Kevin Knobloch is head of the Union of Concerned Scientists, and says many of his members have long government service. KNOBLOCH: Even these seasoned scientists are very upset. They’ve never seen anything on this scale. CONNAUGHTON: This administration has gone to and relied on the National Academy of Sciences more consistently and regularly than any prior administration on the top environment-natural resources issues of our day. CURWOOD: That’s James Connaughton, chairman of the White House Council on Environmental Quality. CONNAUGHTON: On every top line issue we’ve gone to the National Academy of Sciences, and we’ve largely followed their guidance, with rare exception. CURWOOD: But Russell Train disagrees. He’s a former director of the Environmental Protection Agency and chair of the Council on Environmental Quality under Republican presidents Nixon and Ford. TRAIN: I think the White House is making a very big mistake to inject itself in that fashion into the regulatory process. Public health will suffer, and I think that’s a very bad road down which to go. CURWOOD: On November 2nd, for what amounts to a referendum on the Bush administration, how will people respond based on the president’s environmental record? Robert Kennedy Jr. thinks it’s crucial that voters look at that record. KENNEDY: This administration has -- with a concerted, deliberate and clever stealthy effort -- is in the process today of eviscerating 30 years of environmental law. And that’s not an exaggeration, that’s not hyperbole: it is a fact. CURWOOD: But Bush supporters, including Wall Street Journal’s senior editorial writer Kim Strassel, say Mr. Bush has widespread support, and if he would articulate his environmental message better, even more people would respond. STRASSEL: One of the reasons why Healthy Forests was a success story was because Bush actually stood up and said, this is a problem, this is why things need to change, and this is why we Republicans think that this is the right way to go. And I think the Bush administration’s problem is that it’s constantly playing defense on the environmental issue, and they don’t stand up and sort of say we want things to change, we want things to be different from the way it has been going, and here’s why, and we think it will be better if we do it this way. CURWOOD: In the end, James Connaughton says the president’s record will stand on its own. CONNAUGHTON: Is the air cleaner? Is the water purer? Is the land better protected? Are we doing a better job of managing the taxpayer resources that we spend to achieve environmental protection as we move forward into the next century? CURWOOD: Our report today was produced by Susan Shepherd as part of our ongoing series on the environmental records of the presidential candidates. You can hear our profile of Democratic nominee Senator John Kerry on our web site at livingonearth.org. Coming up: to build or not to build? The debate over new roads in some of America’s wildest places is next. Keep listening to Living on Earth. [MUSIC: Adam Wiltzie “Six Million Dollar Sandwich” DEAD TEXAN (Kranky – 2004)] Related links:

Protecting Public LandsCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. As we examine the record of the Bush administration on the environment this week, we turn our attention to the debate about public lands. Part of that debate concerns the future of 58 million acres of national forest that remain largely untouched by humans. The question is whether road-building should be prohibited in these remote areas, or whether roads should be allowed to permit logging and mining So far, the U.S. Forest Service has collected more than one million public comments on the issue – and found that 90 percent of them support the continued preservation of roadless areas. Now the Bush administration is proposing an alternative to the Roadless Rule set up during President Clinton’s last days in office. This new proposal would give individual states more control in deciding whether or not to build new roads in these wild areas. But before we jump into the politics on this issue, Professor Reed Noss joins me to talk about the science of development in roadless areas. Professor Noss teaches conservation biology at the University of Central Florida, and he’s studied the ecological impact of road-building, particularly in the Western states where there are vast forests and strong timber interests. Reed Noss, welcome to Living on Earth. NOSS: Thanks, nice to be here. CURWOOD: Give me a bit of the history here of what’s happened in these national forests where roads are being contemplated, and where some would like to see no roads be built. Traditionally, what’s happened in terms of both timber use and recreational use and roads there? NOSS: Basically, it goes back many decades. But roadless areas were identified as potential wilderness areas by the Forest Service and other federal agencies. And especially during the 1970s, the Forest Service conducted a couple roadless area reviews and evaluations where they identified potential additions to the national wilderness preservation system. Wilderness areas are Congressionally designated, okay, so they’re basically defined by their roadlessness, their remoteness, their wild, pristine qualities. The roadless areas that are not designated, then, have many of these same qualities. And, in fact, they actually represent a broader range of ecosystems; they tend to include more areas of low- to mid-elevation, for example. And they’ve been used for primitive recreation – hiking, backpacking – in many of the same ways that the wilderness areas are. And with this change, then, or this potential change, where roadless areas would be open to more development – they could be logged, they could be used for more motorized recreation. And they could lose many of those pristine qualities that are so important not only to wildlife, but also to humans. CURWOOD: What are the benefits of putting roads in these areas? And what are the costs, do you think? NOSS: Well the benefits – you know, there are some local economic benefits. But I emphasize local. When, for example, the Forest Service builds a road, it’s primarily to access some natural resource. Primarily timber in the national forests, though not exclusively so. So the timber industry -- or the particular timber companies that would bid on these sales and, say, be awarded the sale – would certainly benefit. And there’d be some spin-off benefit to the local economy. However, in general, because these roadless areas tend to be roadless for a very good reason -- they tend to be remote, difficult to get to – road building and subsequent logging in those areas actually costs more to the federal government than they get back in the timber receipts. So it’s basically a subsidized process and the taxpayers foot the bill. CURWOOD: How much do timber companies depend on national forests as a source of the wood that they want to sell? NOSS: Well, nationally, the national forests actually provide very little of the wood harvested in the United States. Most of the production of wood right now are in places like Georgia and northern Florida and Alabama and Mississippi -- where you can grow trees much faster than you can in these western lands, because of the warmer climate, basically, and faster-growing species of trees. And most of that is private land. But, of course, in certain western states there are mill towns that are dependent on wood from federal lands, especially Forest Service lands. So this is really a tremendously variable issue here. But nationwide, timber derived from federal lands is almost trivial. CURWOOD: What are the principle benefits of having these roadless areas? NOSS: Well, I think roadless areas – they really provide something to the science of forestry, and the science of land management, that is critical. Scientists would shudder to think of doing an experiment without a control area. You know, a picture of how healthy land can maintain itself without the help of humans. We’re doing lots of really cool experiments out there with forestry in terms of how to do forestry more gently; how to leave trees, and downed logs, and standing dead trees or snags, and try to better emulate or mimic natural disturbances. But without these roadless areas, these truly wild areas, as references, how are we going to know if we’re succeeding? CURWOOD: Reed Noss is a professor of conservation biology at the University of Central Florida. Thanks for taking this time with me today. NOSS: Thanks very much Steve. CURWOOD: To look at how the Bush administration plans to implement its roadless proposal, and talk about the condition of other public lands, including national parks, we’re joined by Lynn Scarlett, Assistant Secretary for the Department of Interior. Lynn, welcome. SCARLETT: Happy to be with you, Steve. CURWOOD: Now, in the few days before President Clinton left office he signed off on something called the Roadless Rule, which would prohibit road building in remote areas of national forests. This would limit logging, obviously, if there are not roads to pull the logs out on. Now, what was the thinking that led to this decision, do you think? SCARLETT: Well, of course, I can’t speak to the previous administration and their thinking but, clearly, they set forth that rule. They did so in the very waning days -- in fact, it was January, I believe, 2001, just days before this administration came on board. We found ourselves in a challenging situation, because that rule was almost immediately challenged by a number of states. We found ourselves amidst a lot of litigation. And, indeed, in 2003 the courts basically told us, “You’ve got to go back to the drawing board. That rule violates several statutory authorities.” So we’ve had to reexamine the issue and figure out where to go -- leading to a recent decision this year on an interim rule -- and then work to create a final rule. One in which we would cooperate with states to figure out just exactly what areas should be roadless, and what areas should still have access for citizenry and other public purposes. CURWOOD: That’s right, because there’s a concern I hear from the environmental lobbyists -- that they think that if there’s state control, governors will be more responsive to local industry interests, with perhaps less concern for the national conservation goals. SCARLETT: Well, I think we have a very good balance here. First of all, let me suggest there may be some states indeed that want a more aggressive and more stringent roadless rule than other states. But secondly, we do have, of course, the federal agencies involved. And as the ultimate decision-makers, and working with a panel of experts who will be reviewing such things as environmental values, access to private lands, and other considerations that are important in this balancing act. CURWOOD: Let me ask you specifically about a national forest, and that’s the Tongass National Forest in Alaska. It’s our largest. And both the Clinton administration and your administration so far have not really included the Tongass in the Roadless Rules. Yet environmentalists say this is some of the most sensitive and important forestry territory on the planet. How do you see your administration moving forward now with the Tongass, and the extent of logging you’ll permit there? SCARLETT: I will say that the Tongass is a very, very large forest and it is very conceivable that one can have in the Tongass access to some of those timber resources and, at the same time, to have very significant areas of wilderness and environmentally-sensitive and environmentally-protected areas. We in the Department of the Interior manage a significant portion of Alaska through the Bureau of Land Management. And while some of those lands are open to development, there are still millions of acres that in fact are very, very remote and represent some of the best wild places on this planet. CURWOOD: I want to turn now to national parks which, of course, are also a part of the federal land collection. What’s your take on the condition of these parks today? And what do they have in the way of financial resources? SCARLETT: The National Park Service manages some 388 units. And those units range from the two million acres of Yellowstone to individual historic houses like Frederick Douglass’ home. The operating budget for that park system in 2005 will be $1.8 billion – that’s billion with a “b.” By our reckoning that is the most operating funds that the Park Service has had ever, and in fact the most dollars per acre, per visitor, or per employee in the Park’s history. It was estimated that there were some -- well, thousands – of projects and some $4.9 billion in maintenance backlog in the parks. And this president, through his Park’s Legacy Project, committed, by golly, to doing something about that. CURWOOD: What led to the present situation? How did it happen that all this maintenance was deferred? SCARLETT: Well, it’s a very cumulative process, and it has occurred kind of in a creeping fashion over many, many decades. The Park Service gets their budget from Congress and, oftentimes, it’s tempting to spend the money on the things that visitors immediately see. For example, putting up signage or putting up new visitor centers; investing in interpreters who walk people around parks and explain the history and the culture and the natural resources. And if times are tight, it’s often sometimes tempting to set aside those things that are invisible, like that unglamorous wastewater treatment facility or that unglamorous electric utility system, and say, gee, I hope for a better day next year. And so, cumulatively, by the time this president came into office this backlog had gotten to be so large that the president said, “We just have to do something about this.” And that’s what he’s committed to doing, and something I think we’ll continue to focus on from now through the rest of this term. CURWOOD: Lynn Scarlett is Assistant Secretary for Policy Management and Budget for the Department of Interior. Thanks for taking this time with me today. SCARLETT: Very much enjoyed it. CURWOOD: We turn now to Bill Wade, former superintendent of Shenandoah National Park in Virginia. His career in the National Park Service spanned more than 30 years, and he is retired now in Tucson, Arizona. Today, he’s spokesperson for the Coalition of Concerned National Parks Service Retirees, and is working to bring attention to what he calls major problems with our national parks. Bill Wade, thanks for joining me today. WADE: Thank you, I appreciate being here. CURWOOD: Now I’m wondering if you can bring me up to speed on some details of the basic thing that your group is working on, and that seems to be the lack of federal funding for national parks. Map out for me, if you could please, Bill, which parks are most in need of money and why? What do they need this money for? WADE: Well, it’s widespread. The fact is that 85 percent of the parks that have their own discrete budget started out this fiscal year, fiscal year 2004, with less money than they had in 2003. And it’s that part of the budget that they use to hire seasonal employees, that they use to buy supplies and materials. Fewer supplies and materials means that they sometimes have to defer needed maintenance, needed repairs. So simply put, things in parks are taking a downswing right now. CURWOOD: Now the Interior Department tells us that this administration has allotted, and I’m quoting here, “more funding per acre, per employee, and per visitor than ever before into the National Park Service.” WADE: Well, I think that it is true that Congress has given the National Park Service the largest appropriation that it’s ever had this year. But the visitation to the national park system has been declining over the last three years, there are fewer employees now than in past years, and the acreage of the national park system has grown in the last three years by only about ten thousand acres. So it’s very easy to make that statement, and it’s very, very misleading in our judgement. And particularly, the simple fact is that at the park level, there is less money now in almost every parkk. Certainly, very few of them have as much or more money now than they've had in the past. CURWOOD: Bill, describe a particular park, a specific park that’s in disrepair, and perhaps what’s in disrepair is out of view, but obviously not out of function. WADE: Well, let me use Shenandoah National Park as an example. Shenandoah by all accounts ranks number two or number three in terms of severity of air quality of all national parks in the system. There are days where you go up on the Skyline Drive in the summertime and you literally cannot see the valley floor on either side, and that’s three to four miles distance we’re talking about, the haze is so bad. When their air quality specialist position, a significant staff advisor on that critical issue that faces the park, when that position became vacant about eight months ago or so, the park does not have enough money to refill that position. So the superintendent now has to have somebody acting, or a collateral duty advisor for all of the air quality issues that face him in that park. And there are more decisions and more actions, there are more things that I think are inconsistent with the mission of the National Park Service, than we’ve ever seen before. And I’m talking about things like a continued intense attempt to try to continue to allow snowmobiles in Yellowstone. I’m talking about Secretary Norton signing an agreement with the state of Colorado that gives away federal water rights on the Gunnison River as it flows through Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park. So it’s all of these combination of decisions and actions in addition to the budget situation that I believe has threatened or assaulted the values and purposes of national parks more than has ever occurred in the past.

CURWOOD: Given what you’re seeing, what’s going on, that disturbs you so much, what gives you hope? WADE: What gives us hope I think more than anything is that in truth, the resources are fairly resilient, especially the natural resources. So even though they may take a few hits right now, they’ve been known to bounce back, and if this particular trend doesn’t go too far, and if it’s overcome, they’ll be able to bounce back pretty quickly. And I guess that’s what gives us hope, and we’re going to do everything we can to make sure that that sort of thing happens. CURWOOD: Bill Wade is the former superintendent of Shenandoah National Park, and spokesperson for the Coalition of Concerned National Park Service Retirees. Bill, thanks for taking this time with me today. WADE: Thank you, I appreciate the opportunity to be here. [MUSIC: Fontanelle “The Telephone Fade” FONTANELLE (Kranky – 2000)] Related links:

Emerging Science Note/Nature’s WayCURWOOD: Just ahead: concerns about the environment in Florida may cost President Bush some votes in this crucial swing state. First, this Note on Emerging Science from Jennifer Chu. [SCIENCE NOTE THEME] CHU: A new study suggests that a simple walk in the park may be a useful treatment for attention deficit and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign tracked a large pool of children with ADHD to see what influence exposure to nature might have on their behavior. The researchers asked parents to report how their children performed after doing a range of activities – from watching television to reading books to playing group sports. Some activities were held indoors, some at outdoor spots without much greenery, like parking lots, and others at natural outside settings, like backyards and tree-lined streets. The nationwide study included more than 450 five to 18 year-olds. It found that spending time outdoors significantly reduced ADHD symptoms such as inattention and impulsiveness. Scientists are now launching clinical trials to confirm the initial results and recommend treatments. A co-author of the study suggests that ADHD has been on the rise because modern life simply places too many demands on our attention. She adds that a quiet place outdoors can help reduce some of that stress. That’s this week’s Note on Emerging Science. I’m Jennifer Chu. CURWOOD: And you’re listening to NPR’s Living on Earth. ANNOUNCER: Support for NPR comes from NPR stations, and: The Noyce Foundation, dedicated to improving math and science instruction from kindergarten through grade 12; Ford, presenting the Escape Hybrid, whose full hybrid technology allows it to run on gas or electric power. Full hybrid technology details at fordvehicles.com; The Annenberg Fund for excellence in communications and education; and, The Kellogg Foundation, helping people help themselves by investing in individuals, their families, and their communities. On the web at w-k-k-f dot org. This is NPR -- National Public Radio. [MUSIC: Fontanelle “The Telephone Fade” FONTANELLE (Kranky – 2000)]

How Green Goes the Sunshine StateCURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Remember hanging chads? The 36-day recount? How could we forget? Anyone who watched the last presidential election knows how important Florida can be in picking our president. The U.S. Supreme Court ultimately declared George W. Bush the winner with a margin in the neighborhood of 500 votes in Florida, a state in which more than 90,000 votes were cast for Ralph Nader. Arguably, many of those votes for Mr. Nader express dissatisfaction with the environmental positions of the Clinton administration and Democratic nominee Al Gore. This time, voters in this key swing state may take out their frustrations with federal environmental policies on the Republicans. Living on Earth’s Jeff Young has our report. [SURF SOUND UP & UNDER] YOUNG: Floridians love the outdoors. If they’re not enjoying the beaches, lakes or that giant river of grass called the Everglades, they’re making money from visitors who are. Tourism means Florida’s environment is closely tied to its economy and its politics… [SURF SOUND FADES OUT] YOUNG: …which might explain why President Bush visited Florida just after Earth Day this April to promote his wetlands program from the edge of the Everglades. BUSH: For years, our nation has sought to slow the loss of wetlands. Now I believe we must change that goal to one that says we’ll have an overall increase in wetlands every year. Instead of just reducing loss, the goal of this country must be to increase wetlands. [APPLAUSE]

[AIRBOAT STARTING UP, ENGINE UNDER] YOUNG: Gene Duncan guides his airboat through the sawgrass sloughs and hardwood hammocks of part of the Everglades the Miccosukee Indians call home. Duncan is chief of water resources for the Miccosukee tribe and he’s on the lookout for signs of trouble. To the novice eye, trouble seems a world away. Sawgrass sways in our wake and pure white egrets dot the brilliant blue sky and glassy water. [SOUND OF ENGINE CUTTING OFF] YOUNG: But Duncan sees subtle changes in vegetation that hint at much larger problems with water quality. DUNCAN: If you kill off the microorganisms and you kill off the algae, they get replaced with more pollution-tolerant species. And some of those species consume oxygen rather than produce oxygen, so when we start messing around with the stuff at the bottom end you see big changes at the top end. [INSECT SOUNDS] YOUNG: Four years ago, Congress approved a nearly $8 billion project to restore a more natural flow of Everglades water that is now lost to dikes, dams and ditches. Everglades restoration also means reducing water pollution from urban and agricultural areas, especially the high nutrient levels that Duncan monitors. There’s been progress, but Duncan says it’s come slowly and often only after the tribe and environmental groups filed lawsuits. He’s especially frustrated that the government has postponed by up to a decade deadlines for meeting water quality standards. DUNCAN: Actions speak louder than words. Saying you support the Everglades is not doing the right thing. So we’ve got all these people getting elected saying that they support the Everglades, but in reality they turn around and pass laws that push the dates for Everglades compliance back further and further and further. So just saying you’re for the Everglades isn’t good enough. You have to actually do it.

|

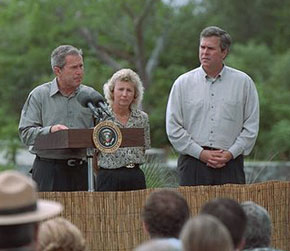

(Photo: White House)

(Photo: White House)  Shenandoah National Park

Shenandoah National Park As his brother, Florida Governor Jeb Bush stands by his side, President George W. Bush speaks at the Royal Palm Visitors Center at Everglades National Park, FL. (Photo: White House photo by Eric Draper)

As his brother, Florida Governor Jeb Bush stands by his side, President George W. Bush speaks at the Royal Palm Visitors Center at Everglades National Park, FL. (Photo: White House photo by Eric Draper)

(Graphic: Bo King, UNC Charlotte Cartography Lab)

(Graphic: Bo King, UNC Charlotte Cartography Lab)