February 26, 2010

Air Date: February 26, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trawling for a Fishing Solution

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Thousands of fishermen rally at the nation’s capitol demanding changes in fishery law. They say tight catch limits could sink their businesses even as fish stocks are rebounding. But scientists warn against a return to policy that brought about the collapse of many fish populations. Host Jeff Young explores ways to chart the right course for our fragile fisheries. (06:15)

The World’s Largest Water Park

View the page for this story

British Prime Minister Gordon Brown is considering setting aside a pristine patch of the Indian Ocean as the world's largest marine sanctuary. Rachel Jones, a researcher at the London Zoological Society Aquarium, has been an advocate for establishing the park. Host Jeff Young speaks with her about the tuna boats, military base and Chagosian people that would be affected by the proposed sanctuary. (05:45)

Cool Fix for a Hot Planet

View the page for this story

Millions of tennis balls end up in the trash every year, sometimes after just hours of actual playtime. When a ball loses air pressure, it’s out of the game – until now. Living on Earth’s Bridget Macdonald reports on a company that is giving old tennis balls a second shot on the court. (01:50)

Waste Not, Want Not

/ Bruce GellermanView the page for this story

President Obama’s decision to cut federal funds for the Yucca Nuclear Waste Repository leaves operators of the nation’s reactors holding more than 120 million pounds of high level waste. Federal officials say that the waste is safe, but critics say spent fuel pools are vulnerable targets for terrorists. Several State Attorneys General are suing to change that. Senior Correspondent Bruce Gellerman investigates the Pilgrim reactor in Plymouth, Massachusetts. (10:15)

Solving Nuclear Waste

View the page for this story

Now that the Yucca Mountain repository is all but shut down, where does the high level waste go? Host Jeff Young talks with Dr. John Garrick, chairman of the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, to find out what other nations are doing with their radioactive spent fuel. (05:50)

Here Comes the Sound

View the page for this story

Bark beetles have eaten their way through millions of acres of forest in the West. Host Jeff Young talks to audio engineer David Dunn and researchers Richard Hofstetter and Reagan McGuire about using sound to combat the infestation. (12:20)

Big Blue

View the page for this story

On the shallow edge of the marsh, the Great Blue Heron stands. Salt Marsh Diary writer Mark Seth Lender watches, transfixed by the majesty of the large wading bird. (03:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young

GUESTS: Rachel Jones, John Garrick, David Dunn, Richard Hofstetter, Reagan McGuire

REPORTERS: Bruce Gellerman

ESSAY: Seth Lender

COOL FIX: Bridget Macdonald

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. The President wants a new generation of nuclear plants – but problems persist about old nuclear waste.

TARANTINO: All the fuel that we’ve ever used resides in that spent fuel pool. It was never intended to be the permanent repository for that, so the now the fuel needs to be stored somewhere.

YOUNG: The dangers of decades of radioactive rubbish. Also fishermen want off-the-hook on overfishing. They say many fish stocks that collapsed have now recovered.

MARCIANO: I have a son who loves to come on the boat. I would love to see more fish in the ocean for him than there was for me. And I believe we’ve achieved that. We’ve been rebuilding stocks.

YOUNG: Setting the right course for our fragile fisheries. And contemplating the king of the salt marsh. Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth. Stay with us!

[THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Trawling for a Fishing Solution

Fishermen object to the Maguson Act that limits catch to rebuild stocks. (Courtesy of United We Fish)

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts - this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Thousands of fishermen from the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts left their boats for a day Wednesday to travel to Washington. They’re hoping to catch a break from the law’s limits on over fishing. At a Capitol lawn rally called United We Fish, New York Democratic Senator Chuck Schumer said the law that’s helping to bring fish stocks back from collapse should change.

SCHUMER: Now, rebuilding our fisheries is important – we know that, we agree. But we need to start caring as much about our fishermen as we do about our fish!

[CHEERS AND APPLAUSE FROM CROWD]

YOUNG: Schumer wants a change to the landmark Magnuson-Stevens Act, which uses science to set limits on what types and what numbers of fish can be caught. He thinks it should take economics into account and delay some deadlines for rebuilding fisheries. It’s the latest round in an increasingly bitter dispute over how to bring fisheries back.

[SOUNDS OF WATERFRONT]

YOUNG: Gloucester, Massachusetts, like many fishing communities, has weathered many changes in the industry. In the 70s giant foreign-owned vessels depleted fisheries from just beyond U.S. waters. Then, government loans encouraged a new wave of local boat owners in the 80s. That was followed by over fishing, collapse of many important stocks, and a painful contraction of the fleet. Key parts of the Magnuson Stevens Act aimed at ending over fishing kick in this year. Gloucester Mayor Carolyn Kirk worries that could mean tighter catch limits and even fewer boats in an already stormy economy.

KIRK: Gloucester is the oldest seaport in America we’ve been fishing for over 400 years and I think that the future of Gloucester as a seaport is very much in jeopardy.

YOUNG: Kirk met with fishermen from the region to plan their rally in Washington. Government resentment and distrust run deep here. In the parking lot, a truck’s bumper sticker reads: “National Marine Fisheries Service – destroying fishing families since 1976.” That’s Tina Jackson’s ride. She fishes and traps lobsters out of Point Judith, Rhode Island. Jackson says fishermen sacrificed to help rebuild stocks only to face further restrictions.JACKSON: Fishermen have been told time and time again that they will be rewarded, they will be given days at sea, they will have more fish to fish on. We are supposed to be fishing on 170 thousand metric tons of fish along the East coast every year. Last year they gave us 43 thousand.

YOUNG: Atop Jackson’s list of complaints is the government’s shifting rulings on whether a fish stock has recovered or is still over fished. She says just as a fish stock appears to be recovered, the government’s numbers change. David Marciano agrees. He’s a 30-year Gloucester fisherman who worries he might not be in business much longer.

MARCIANO: We’ve been rebuilding stocks. We’re at the ten-yard line and they’re moving us to another stadium. Know what I mean? It’s completely arbitrary and unfair. Never mind moving the goalposts, they’re taking it right to another stadium and leaving us here.

YOUNG: But I guess if I were looking at this from the conservationist’s perspective, I might say we have to be vigilant, if we let up now we’re going to fall back into patterns that got us into trouble with declining stocks in the first place.

MARCIANO: We’re not saying we’re not about preserving stocks; I have a son who loves to come on the boat. I would love to see more fish in the ocean for him than there was for me. And I believe we’ve achieved that. That’s why I think it’s a shame to be forced out of business by agenda-driven politics.

YOUNG: Marciano says he knows some fish stocks are still struggling but others are more numerous than he’s ever seen. Why should one weak stock prevent his fishing the other? Steve Murawski has heard a lot of these complaints. He directs scientific programs for fisheries at NOAA the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which sets fishing regulations. Murawski’s sympathetic to the fishermen’s frustrations. But says those changes in targets for rebuilding fish stocks were necessary as science improved.

MURAWSKI: It’s a very dynamic thing because our knowledge of the oceans is dynamic. So what we have is an entire fishery in transition where the most productive ones, where we’ve been able to control over fishing, are responding well. But the law requires that we rebuild the complex. And that includes being sensitive to the stocks that grow slower and are perhaps even more vulnerable to over fishing.

YOUNG: That explains part of what fishermen like David Marciano see out on the water. This time of year Marciano’s fishing haddock and cod. Murawski says the fast growing haddock of George’s Bank are doing great – the highest numbers ever. But cod? Still not so good. And remember, Murawski says, the law calls for restoring all stocks, not just a few.

(Courtesy of United We Fish)

YOUNG: The rallying fishermen and politicians like Senator Schumer say the best fix for that is to change the law to add flexibility. But conservation groups say that’s a dangerous course. Pew Environment Group fishery policy director Lee Crockett says Schumer’s proposal would put economics ahead of conservation.

CROCKETT: And we feel that is a shortsighted strategy. It was the way we used to do things and we had stock collapses in New England and the Gulf of Mexico so we know what’s going to happen if we allow that and we just don’t want to go back to that failed model.

YOUNG: Crockett says a better way is to change fishing to be more fish specific. A NOAA program called cooperative research finds ways to do that – it might be different bait for hook lines, or better timing of fishing to target plentiful stocks and not the scarce ones. That program, however, could be gutted. The president’s budget would scale back its funding. There’s much more on fisheries at our website l-o-e dot org.

[MUSIC: Marc Ribot “Todo El Mundo Es Kitsch” from Ceramic Dog (Koch records 2008)]

Related links:

- The United We Fish rally organizers

- National Marine Fisheries Service on sustainable fishing

- Pew Environment Group on Overfishing

The World’s Largest Water Park

Middle Brother Island is one of the more than 50 islands that make up the Chagos archipeligo. (Photo: Anne & Charles Sheppard)

YOUNG: Now we go a bit farther out to sea. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown will soon decide on what could be the world’s largest marine sanctuary – 210 thousand square miles around the Chagos islands. The 60-some British-owned Chagos Islands lie about a thousand miles southwest of India – they include the U.S. naval base of Diego Garcia. They also include some of the planet’s most pristine reef waters – and Rachel Jones, a researcher at London Zoo’s aquarium – has been there.

Advocates say restricting fishing in the Chagos marine sanctuary will increase fishable populations around the preserve. (Photo: Anne & Charles Sheppard)

So when you jump off a boat in the Chagos, you see these enormous fish coupled with the fact that the fish are not nearly as scared of you as they should be by rights, and then as you drop down and swim over the reef you see an incredible biodiversity. It’s an ecosystem that is pretty much intact, and that’s unusual so it’s very much like going back in time, jumping off a boat 50 years ago when reefs were really, really in good shape.

YOUNG: Well, if the area’s already healthy and in good shape, why is a special protection important?

JONES: The Chagos at the moment has a degree of de-facto protection from the British government, but there is also some exploitation. There are two tuna fisheries that operate in the area, and for about a month of the year they’re in the waters around the Chagos Islands catching tuna. And along with the tuna that they mean to catch there’s a huge number of fish that they also take as by-catch, and they’re usually things like billfish and lots and lots of sharks.

(Photo: Alasdair Harris, Blue Ventures Conservation)

JONES: There’s a fair bit of good evidence that marine protected areas have an impact. In the relatively short term we can start to see some populations of fish bounce back within a few years, certainly within five to ten years we’re seeing very much increased populations of fish. And this has a knock-on effect for people fishing around a marine protected areas, so even though the area within which they’re free to fish may be reduced, their catches may actually go up, which is slightly counterintuitive.

The benthic animals like corals, the ones that are attached to the bottom, take a little bit longer, and when you start to see the reef-forming corals building back up again you’re really talking about the trees in the forest – these are the animals that make the reef, itself, they make the habitat that all the other animals – fish and other invertebrates – rely on.

YOUNG: It seems to me that most people who’ve been to this place have probably been there as part of the military because of the base on Diego Garcia. How does that effect the decision that your prime minister faces here – the fact that there is this important military base there?

JONES: That’s right, there’s certainly the suggestion that you could effectively ring fence Diego Garcia and have that off to one side. I’m certainly not in a position to comment on that whether that would happen politically or militarily, but yes, there is a long-term commitment to keep Diego Garcia going as a military base. In fact, on Diego Garcia there are large areas of the island which are again de-facto and in some cases statutory protection as various nature reserves and restricted areas.

Diego Garcia, once home to the Chagosian people, now hosts about 1,700 US military personnel and 1,500 civilian contractors. (Photo: Google Maps)

YOUNG: Now the history of the military base is interesting in that the people who once lived on Diego Garcia were essentially evicted, moved to other islands to make way for the military base. What about those people? I mean don’t they have some say in that island and what should become of it as part of a potential marine sanctuary?

JONES: Yes, and what the network I represent said very clearly is the environmental protection of these fantastic areas really is in everybody’s best interest, whatever the future may hold – in terms of the Chagosian people and their possible resettlement, they’ve got a case with the European courts at the moment, which is pending and who can say what the outcome will be? But I very much believe that the case we’re making now for environmental protection is very much without prejudice to the case they’re making for resettlement.

YOUNG: Now, here in the U.S. president Bush made a pretty big splash, pardon the pun, in the last months of his presidency by declaring what at the time was the world’s largest marine sanctuary, but as I understand it, this one – if prime minister Brown decides to make this a sanctuary – it would be bigger, right?

JONES: That’s right, it would. It would be the world’s biggest. But, Bush’s rather last minute declaration of that sanctuary was incredibly impressive. I think it surprised a few people over here, but it was actually quite inspirational. If Gordon Brown were to follow the idea of declaring the entire area protected, it would increase the percentage of a strictly protected area in the world’s oceans by 20 percent. And he could literally do that overnight – it’s an incredible, exciting opportunity.

YOUNG: So, Mr. Brown could look pretty green by protecting a big patch of blue? Do I understand that correctly?

JONES: [Laughs] Yes, something along those lines!

YOUNG: Rachel Jones is with the London Zoological Society Aquarium. She’s been telling us about the Chagos Islands. Thanks very much.

JONES: Thank you.

[MUSIC: David Byrne/Brian Eno “Strange Overtones” from Everything That Happens Will Happen Today (Todomundo Records 2009)]

YOUNG: Just ahead – how to handle some of the most dangerous waste on the planet – keep listening to Living on Earth!

Related link:

Learn more about the push to protect Chagos.

Cool Fix for a Hot Planet

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. Vancouver’s Winter Olympic Games won some green credibility with unique medals – the gold, silver and bronze are all salvaged from electronic waste. We have another idea for reuse of old sports goods and it’s this week’s Cool Fix for a Hot Planet from Bridget Macdonald.

[SOUNDS OF TENNIS COURT]

Reduce, reuse, recycle, and now, rebounce. There’s a new way to score points for the planet – on the tennis court.

[COOL FIX THEME]

More than 300 million tennis balls are made every year worldwide. But a ball’s life lasts only as long as its bounce. Even if it still looks brand-new, when a ball starts to lose air pressure, it’s “OUT” – off the court, and eventually, into a landfill.

Recycling centers won’t take tennis balls because of the high cost of separating the felt from the rubber. So tossed out balls make up nearly 20,000 tons of solid waste each year. That’s the weight of 500 18-wheelers.

But now an Arkansas-based company called Rebounces has found a way to put old balls back into play. The company re-pressurizes balls that have little wear and tear, extending their lives on the practice court by up to three weeks.

Rebounces is also developing a way to grind up worn-out balls for making court surfaces, or even garden mulch. For now, Rebounces finds good homes for retired balls. They’re donated to hospitals and nursing homes, where they’re placed on furniture legs and walkers to keep them from scuffing the floors.

Not every ball is destined for a Grand Slam, but they can all be environmental champions. That’s this weeks Cool Fix for a Hot Planet. I’m Bridget Macdonald.

YOUNG: And if you have a Cool Fix for a Hot Planet, we'd like to know it. If we use your idea on the air, we'll send you a shiny electric blue Living on Earth tire gauge. Keeping your tires properly inflated can save hundreds of dollars a year in fuel. So email us at coolfix—that's one word— coolfix at l-o-e dot org.

[END COOL FIX THEME]

Waste Not, Want Not

YOUNG: Vermont just said no to nukes. Vermont’s State Senate blocked a license extension for the aging – and leaking – Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant. That comes just days after President Obama announced billions of federal dollars to build reactors. The president wants a new generation of nuclear plants, but as the Vermont vote shows, old problems still plague the industry. One of the biggest problems is what to do with nuclear waste.

The Obama administration’s budget would eliminate funding for Yucca Mountain. That Nevada site for high-level nuclear waste was supposed to start taking spent fuel from commercial reactors in 1998. But Yucca never opened and very likely never will. Which means, for the indefinite future the radioactive waste from nuclear plants will have to be stored on site. Critics say that generates a whole host of concerns. Living on Earth’s senior correspondent Bruce Gellerman reports.

GELLERMAN: The Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant is 40 miles south of Boston just down the coast from Plymouth Rock. It’s one of the 104 commercial reactors operating in the United States and virtually identical to the Vermont Yankee plant.

[ENVIRONMENT AMBIENCE AROUND PLANT]

GELLERMAN: As you might expect security here is tight. There are concrete barriers and surveillance cameras. Security measures seen and unseen. Guards at the entrance wear combat fatigues, carry guns and extra clips for their automatic weapons and masks to filter radiation just in case.

TARANTINO: Security is a major factor in our lives here.

GELLERMAN: Dave Tarantino is head of public affairs at Pilgrim.

[SOUND OF CAR DOOR CLOSING]

GELLERMAN: We meet at the front gate of the power plant, get into Tarantino’s company truck, and talk about Pilgrim.

[SOUND OF CAR DOOR CLOSING]

GELLERMAN: The plant is owned by Entergy, the second largest generator of nuclear power in the United States, and Pilgrim is the sixth largest reactor in the nation.

TARANTINO: Interestingly right now we’re in the middle of a 20 million dollar upgrade and a new ring of security.

GELLERMAN: Tarantino doesn’t go into details – they’re classified. Behind the fence and barricades the Pilgrim nuclear reactor has been generating electricity since 1972 – enough energy to replace 10 million barrels of oil a year.

TARANTINO: Unlike most power generation – where does their waste go? If we’re looking at coal, gas – where does it go? It goes into the air doesn’t it? Ours isn’t in the air. Ours is not in the environment. Ours is safely stored. We don’t contribute to greenhouse gases. So there’s a lot of positives and it’s a very small amount of waste for all the electricity we’ve generated.

David Tarantino, head of public affairs at Pilgrim. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

LAMPERT: When we moved here a few people said to me, you know there is a nuclear plant there. And I thought: there is?

GELLERMAN: Since 1986, Lampert and her husband have lived in a rambling colonial home 6 miles upwind across the bay from the nuclear plant. But it wasn’t operating back then. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission shut Pilgrim down for safety violations. Three years and half a billion dollars of improvements later, the NRC allowed Pilgrim to re-open.

[LAMPERT WALKING UP STEPS]

GELLERMAN: That’s when Mary Lampert began to take notice…

LAMPERT: When I had a life this used to be a closet.

[GELLERMAN LAUGHS]

GELLERMAN: Today, this former closet is the office for Pilgrim Watch, an organization Lampert founded 10 years ago.

LAMPERT: This is where I work.

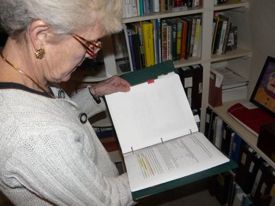

GELLERMAN: 68-year-old Mary Lampert volunteers 50 hours a week watching Pilgrim, which you can see just over the top of her computer monitor.

Mary Lampert, founder of PilgrimWatch.org. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

GELLERMAN: Over the years Lampert has gotten the town to put in emergency evacuation signs and stock potassium iodide pills against radiation, and her thinking about Pilgrim has evolved:

GELLERMAN: So you’re not saying “no nukes” at this point?

LAMPERT: If I had my preference I know there are safer and cheaper ways to turn the lights on. I know that. But I know that’s not doable in this environment. So my goal is simply: what can be done to make it safer?

GELLERMAN: Lampert’s number one concern: the spent fuel. The intensely hot and high-level radioactive waste produced by Pilgrim’s reactor.

TARANTINO: All of the spent fuel that we’ve used since 1972 currently resides in the spent fuel pool.

GELLERMAN: Spokesman Dave Tarantino says Pilgrim, like all nuclear plants in the United States, uses a pool to cool down used fuel assembly rods when they come out of the reactor. When Pilgrim was built four decades ago spent fuel was supposed to stay in the pool for about a year then get reprocessed into new fuel. But the U.S halted reprocessing in 1977, so nuclear plants have had to pack and re-rack the radioactive rods closer and closer together. Pilgrim’s pool now contains five times as many spent fuel assemblies than it was originally designed to hold: 38 years worth of high-level radioactive waste.

TARANTINO: It was never intended to be the permanent repository for that, so now the fuel just needs to be stored somewhere.

GELLERMAN: In the future Pilgrim plans to move some of the spent fuel into dry casks – huge cement coffins – and store the casks on site. But waste rods will continue to remain in the densely packed pool. Pilgrim’s pool is 40 feet deep, 30 feet long and 20 feet wide. It’s lined with stainless steel and thick reinforced concrete walls. Most nuclear plants have below ground pools. But at Pilgrim and Vermont Yankee – along with more than 30 other plants in the United States that were designed in the 1960’s – the spent fuel pools are located above the reactor, outside of the primary containment shell.

TARANTINO: And the spent fuel pool is inside secondary containment surrounded by five feet of reinforced concrete with a steel liner.

GELLERMAN: So there is five feet of containment around the entire pool area.

TARANTINO: Except for the top – the top is open.

LAMPERT: The roof is about as sturdy as the roof over our high school gym.

GELLERMAN: Mary Lampert of Pilgrim Watch.

LAMPERT: The amount of radioactivity in that swimming pool on that attic of Pilgrim is about eight times than what’s in the core, in the reactor. What is there to prevent a terrorist from attacking? In a very small private plane, loaded with explosives could target it and that would be the ball game.

Mary Lampert reads an NRC document. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

NEWSCASTER: We are following breaking news out of Austin, Texas where the pilot of a small plane slammed into a seven-story building. That building houses offices for the Internal Revenue Services and the CIA.

GELLERMAN: F16 jets scrambled to the scene. It’s a scenario independent nuclear analyst Gordon Thompson has warned could happen at plants with above ground waste pools.

THOMPSON: These facilities are obvious targets. And I’ve described them as radiological weapons awaiting activation by an enemy.

GELLERMAN: Gordon Thompson is executive director of the Institute for Resources and Security Studies. He says if a plane hit a densely packed spent nuclear fuel pool, like the one at Pilgrim, with its roof unprotected, water could drain from the waste pool, and the exposed assembly rods could ignite into an unstoppable fire, sending enormous amounts of radioactivity into the atmosphere.

Gordon Thompson, executive director of the Institute for Resources and Security Studies. (Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

THOMPSON: And this argument has been made at proceedings before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and they have consistently rejected this argument.

MCINTYRE: Oh, of course the NRC has looked at this in great detail in the immediate aftermath of the 9-11 attacks.

GELLERMAN: David McIntyre is a spokesperson for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The NRC licenses and regulates U.S. commercial reactors. McIntyre says there are redundant safety systems and security at each plant has been studied:

MCINTYRE: We believe because the modeling that we did, and the very intensive and of course classified security analyses we did of these facilities that the risk of any fire caused by an accident or a terrorist attack is very low. We believe the high-density storage is safe and there’s no over riding need to change that.

(Photo: Bruce Gellerman)

GELLERMAN: Mary Lampert of Pilgrim Watch.

LAMPERT: And I’m sorry, that’s not what we’re going to do.

GELLERMAN: What Lampert is doing – and so are the Attorneys General from Connecticut, California, Massachusetts and New York – is suing the NRC over the waste pool issue. They seek a review of the classified information the NRC used in its calculations and they want the spent waste pools to be considered when a nuclear plant applies to renew its operating license.

About half the nation’s reactors have already been relicensed, all that have applied to the NRC have been granted 20-year extensions beyond their original 40-year permits to operate. Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant is one of about a dozen that is seeking renewal, but as the NRC regulations now stand the security of the plant and waste pool cannot be challenged. Again, David McIntyre of the NRC:

MCINTYRE: We look at security 24/7 so we’re not really looking at security during the relicensing because that’s not the appropriate venue for looking at security. We’re looking at security every day for every one of these plants.

GELLERMAN: Today, there is more radioactive waste being stored in spent fuel pools at the nation’s 104 reactors than the Yucca Mountain federal repository was designed to hold.

[SOUND OF CLOCK TICKING]

GELLERMAN: And a clock on the Pilgrim Watch web page ticks off the time to 2012 when that the Pilgrim nuclear power plant’s 40-year operating license is up and space in it’s spent fuel pool is maxed out. For Living on Earth I’m Bruce Gellerman.

[CLOCK SOUNDS CONTINUE]

Related links:

- Pilgrim Nuclear Power Plant

- PilgrimWatch.org

Solving Nuclear Waste

YOUNG: Time is a major factor when it comes to nuclear waste. Some radioactive materials produced in reactors can last thousands – millions – of years. With Yucca Mountain’s apparent demise President Obama has asked a bipartisan panel of experts to recommend waste solutions. Another expert panel’s work gives us some strong hints about what those solutions might be. The U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board – an independent body – recently surveyed 13 other nuclear nations to see how those countries handle the waste. Physicist and engineer Dr. John Garrick chairs the review board.

GARRICK: There’s unanimous agreement, almost, that the best approach to the disposal of high level radioactive waste and spent nuclear fuel is deep geologic disposal. So, that’s a major finding of the survey, and frankly a major accomplishment of the international nuclear energy program that there is good consensus on what might be a reasonable solution.

YOUNG: And is anyone actually doing that yet or close to doing it?

GARRICK: Well, France, Sweden and Finland – they have established target dates to begin repository operations. Finland’s target date is the nearest and that’s 2020; Sweden, 2023; and France’s target date for beginning of operation of their repository is 2025. There is one other country, Germany, that has announced that it has lifted the ban on studying a site in Gorleben for possible development of a deep geologic repository. So, you have Germany, France, Sweden, Finland, and U.S. that are pretty much on a track towards sighting something with a bump in the road with respect to the U.S.

YOUNG: Bump in the road? That’s how you characterize what’s going on with Yucca Mountain?

GARRICK: Yeah, that’s – well, we know that for the time being at least that Yucca Mountain has been shelved. We don’t know whether it will be considered in the mix of options to be studied and perhaps reconsidered. That will all depend upon the outcome of a blue ribbon commission that has been established by president Obama.

YOUNG: So, if all of these other countries are looking at deep geological storage, is that really the only option here? What about reprocessing spent nuclear fuel?

GARRICK: Yes, there are countries that use reprocessing. Japan is one certainly. France is one. Others are planning to reprocess. The United Kingdom has been reprocessing. But the issue of reprocessing is a very dubious one at this point because of economic considerations, because of the value received is not quite to the extent that it was envisioned as a waste management option. No matter how much reprocessing we do, there will always be a certain amount of waste that we’ll have to contend with by some method of disposal.

YOUNG: So Finland is probably closest to actually putting waste in the ground. And curiously, it seems there that people are fairly receptive. In fact, I read that one community’s competing with another, even suing another, to win the right to be the disposal area. That’s a difference that we have kind of a hard time relating to here after the experience with Yucca Mountain, isn’t it?

GARRICK: Well, I think the one thing you have to take into consideration is that Finland has four nuclear power plants. Finland has a population of – what? – five to six million people, and the political and technical decision making process is just ever so much more simple.

YOUNG: Well, you know, that raises a point. I know technical is the middle name of your organization, but is this really at the end of it all a technical problem?

GARRICK: Well, to a lot of technical people, it is not. It has some technical issue associated with it, but most of the problems associated with sighting are problems of the type of finding a community or a region that would be willing to host – be the host location for a repository. And this is complicated by the baggage that anything nuclear tends to carry with it. It’s just a very difficult situation to sell. It’s more of a political problem than a technical problem.

John Garrick

GARRICK: We need to get the message out that there is a solution to the nuclear waste problem. And I think as long as we continue to consider alternatives that are temporary, interim, and storage is in that category. We leave the question open as to whether or not there is really a solution. I think one of the real problems with the whole nuclear program is that we have not as a result of our leadership developed a national will to support it and let sound science and public acceptance be the principle drivers for our decision making. And I think if we did this it would go a long ways to solving the problems.

YOUNG: Well, Dr. John Garrick, thank you very much.

GARRICK: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Nuke Waste Q&A: Thunderball “Angela’s Lament” from Scorpio Rising (ESL Music 2001)]

YOUNG: John Garrick is chairman of the U.S. Nuclear Technical Review Board. And next week we follow the Yucca Mountain money. Consumers paid billions to dig that hole in the ground and could pay even more.

KRAFT: If things continue the way they are, the rate payer will continue to pay and get no services because they’re shutting down the Yucca Mountain project which was the only thing that program was currently paying for.

YOUNG: A nuclear money meltdown. That’s next week.

[MUSIC: Nuke Waste Q&A: Thunderball “Angela’s Lament” from Scorpio Rising (ESL Music 2001)]

YOUNG: Coming up: A sound idea to tackle the bark beetles chewing up western forests – that’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for the environmental health desk at Living on Earth comes from The Cedar Tree Foundation. Support also comes from the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund for coverage of population and the environment. And from Gilman Ordway for coverage of environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI – Public Radio International.

Related links:

- Click here for the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board’s report to Congress on nuclear waste.

- Read IEEE’s feature on Scandinavian waste solutions.

Here Comes the Sound

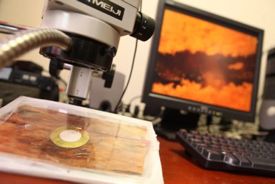

Blasting beetle sounds into tree pieces. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. Across the American West, millions of acres of forests are dead because of beetles about the size of a grain of rice – the pine bark beetles. The beetles’ range is expanding due, in part, to climate change. Warmer winters mean the beetles survive farther north and higher up. And drought weakens a tree’s resistance.

Forestry experts call it the largest insect infestation in North American history and warn some 20 million acres could be lost in the next decade or so. Now an unusual trio of researchers – a sound artist, a scientist, and a student – might have a powerful new way to control the beetles. And they found it by listening. We’ll hear from all three them and their remarkable little subjects, starting with David Dunn. Mr. Dunn’s an audio engineer and musician in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where the bark beetle has devastated some forests.

Audio engineer David Dunn in the recording studio. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

YOUNG: That sounds like some pretty tight working quarters. How do you get recording equipment inside there?

DUNN: Well, you have to get some kind of microphone into that layer of the tree and that was the first challenge, and I spent oh, two, three weeks thinking about the problem and came up with a very simple solution, which is just to take what we call peazobenders (sp?), little, flat discs that are the output transducers inside of green cards and marry that to some kind of meat thermometer.

And these two things were glued together with a couple other little pieces of apparatus. When the beetles invade they leave little entry holes where they’ve bored into the tree a kind of sawdust comes out, and you can just push this device right through the outer bark into that layer.

YOUNG: So what did you hear when you first knew you had success?

DUNN: The first sounds I heard was just sort of a stirring, crackling noise that turned out to be the beetles moving.

[SOUNDS OF CRACKLING WOOD]

DUNN: After listening for a few minutes, suddenly I began to hear these little chirping and clicking noises, which are the distinctive sounds that they make.

[SOUNDS OF INSECT’S HOLLOW CHIRPS AND CLICKS]

DUNN: It’s very much like if you’d rub your fingernail across the surface of a phonograph or an LP and it’s a similar kind of sound.

YOUNG: David Dunn thought these recordings might be of use to entomologists. So he put out a CD of the beetle sounds in hopes that scientists would find it. And they did. Professor Richard Hofstetter and his research assistant Reagan McGuire study bark beetles at Northern Arizona University. And they’ve been working with Dunn ever since coming across that CD. Hofstetter and McGuire were already exploring ways to use sound to deter beetles, with mixed results – which is a pretty interesting story in itself. And they’re here now to tell us about that. Gentlemen, hello!

HOFSTETTER: Hello, this is Richard Hofstetter.

MCGUIRE: Hello, this is Reagan McGuire.

YOUNG: Where did this idea first come from to use sound to fight beetles?

MCGUIRE: Well, before I met Richard about five years ago I had read an article in the local paper that bark beetles had killed 74 million trees in Arizona and New Mexico in the last five year, and it got me to thinking about this is a problem that needs to be dealt with. All the sudden, I had the idea: why not use military control technology where they use acoustics to control crowds or Somali pirates to push them off.

Research Assistant Reagan McGuire. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

MCGUIRE: Ha, I thought about what are the two sounds or the type of music that really annoyed me, and for me it was Rush Limbaugh and heavy metal. It turned out I had to play Rush Limbaugh backwards because I had to sit in the lab and monitor this all day long and he just drove me nuts – he was irritating.

[ALL LAUGH]

HOFSTETTER: Yeah, we quickly realized that any sound wouldn’t work, and after five or ten minutes, beetles made it sort of like a background noise where they eventually would ignore it.

YOUNG: Did you think of using The Beatles?

MCGUIRE: [Laughs] No, I happen to like The Beatles.

YOUNG: So playing music, talk show hosts, this didn’t work. You needed a different approach, what did you try then?

HOFSTETTER: You know, after we tried just any sort of noise, we thought we should be doing something that’s relevant to the insect. And the easiest approach right there was just let’s play back calls from insects to see if we can get a response. And we got a pretty strong response. For instance, we could play the call that the male would make when he meets a female, and we call it an attractant chirp or call, and he kind of sounds like a chu-chu-chu chu-chu-chu:

[MALE BEETLE’S ATTRACTANT CHIRP]

HOFSTETTER: And we’d make that recording, play it back and we’d see the female respond to this call:

[FEMALE BEETLE’S HOLLOW CHIRP RESPONSE]

HOFSTETTER: And so once we realized we could change behaviors we thought we were on to something pretty big.

YOUNG: So, what do beetles do when they hear these sounds?

HOFSTETTER: Uh, it depends, and it depends on the call being made and what behavior you’re trying to influence. For instance, they may start to tone in circles because of the input of the sound, they may block off the tunnel entry because of the sounds we put in.

Professor Rich Hofstetter with phloem, a tree layer inside the bark, and beetles. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

MCGUIRE: And maybe one of the most striking things is why I’ve been able to watch a male mate with a female two or three times and then all of the sudden turn on that female and kill her – it will chew her to pieces. You know, you don’t see that in nature, that’s not natural. We’ve had a bark beetle actually chew through the Plexiglas to escape. Just remarkable behaviors, they kind of amaze us as we watch.

YOUNG: You’ve kind of become the voice on the workplace PA system telling them all what to do.

HOFSTETTER: In a way, that’s kind of what’s happening and that’s sort of our approach is that if we can change what they do we can stop them from killing a tree.

YOUNG: This is just astounding that you’re able to dictate their behavior so specifically in some cases here. I mean, it sounds to me like you’re really learning a lot more about pretty basic beetle biology and behavior here.

HOFSTETTER: Yeah, it’s definitely true and we have a strong interest in using this to reduce tree morality, but also we’re interested in the basic science here. We’re also very interested in how insects hear. We don’t actually know what frequencies they’re able to hear, we don’t know what body part is listening. For instance, is it on the feet, the abdomen, the antennae, we actually don’t know. We have several other colleagues that are pursuing these questions, as well.

YOUNG: I had no idea there were such gaps in basic understanding of how beetles even hear – we don’t know where their ears are?

MCGUIRE: No, and you have to understand that there’s a forty percent of the insects on the planet are beetles and there is no history, no understanding of their communications, at all.

The pine beetle. (Photo: Richard Hofstetter, Northern Arizona University)

YOUNG: Minor correction there, I would call it ear opening, but that’s just my bias in radio.

[HOFSTETTER LAUGHS]

YOUNG: Well, the laboratory part of this so far sounds just fascinating, but I’m still really puzzled, how do you actually do this out there in the field?

HOFSTETTER: I think out approach right now is inputting the sounds for individual trees and so we use a type of speaker device that has our recordings that we play into a single tree and this would couple or screw into a tree…

MCGUIRE: But also, we’re looking at being able to broadcast at some point and protect whole stands of trees and that is on the drawing board.

YOUNG: Beetle radio, you’re talking about?

[ALL LAUGH]

MCGUIRE: Yes, actually.

YOUNG: What do you think about how practical this might end up being – it sounds to me like it’s going to be a tad expensive to try to do this on a large scale?

HOFSTETTER: On a large scale, I think it may not be practical, but you know for high value trees on private property, campgrounds, roadsides, you know I think about the cost to spray a tree is in the hundreds of dollars if you’re going to use pesticides. And so this device actually would be quite a bit cheaper than that. And you think if you’ve got to spray every time it rains or every year, here’s a device that would be – I can’t say the cost, but maybe 50 dollars, roughly. But you’d only need that once and it would last for as long as you needed.

YOUNG: What’s your inclination here – will this work?

HOFSTETTER: [Laughs] Well, it works in the lab and it’s worked on logs and it’s worked in sections of trees. So we have a pretty strong idea that this will work.

YOUNG: But you’re fighting against some pretty powerful biology. I mean, will the beetles figure this out?

HOFSTETTER: I don’t think so, it’s possible that there are some beetles that wouldn’t be affected by the sound, and they may get into a tree and reproduce, but if we can reduce the fitness or fecundity of beetles by even a fraction, it will be helpful.

YOUNG: It sounds to me like you don’t have a deep animosity toward the beetle despite what it’s doing to your beloved woodlands.

HOFSTETTER: I don’t, you know, it’s given me a career! [Laughs] I can’t complain too much.

YOUNG: [Laughs] That beetle’s putting food on the table!

HOFSTETTER: They’re beautiful organisms. No, they’re actually not that pretty. They’re just black or brown and kind of look like a beetle, but they’re very complex in a sense of they sort of are keystone species, and so in that sense they’re very interesting to study because they actually create environments for many other organisms.

YOUNG: Richard Hofstetter and Reagan McGuire of Northern Arizona University. They say patents are pending on some of those sound recordings. And beetle audio device is being field-tested. Now, it’s tempting at this point to say something like – “new weapon in battle against beetles”. But, as Professor Hofstetter says, the beetles aren’t the enemy; they aren’t even really a problem under normal conditions. Conditions, however, are not normal – that’s the problem.

A warming world is a weird world where beetles spread due to climate change and maybe even contribute to climate change. If the beetle-killed trees burn, it pumps more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere in a feedback loop with scary consequences. David Dunn gave all this a lot of thought while he was listening in on those insects ravaging the woods around his home.

DUNN: They are extraordinary little rich societies of creatures that have a purpose within the ecology of the forest, unfortunately things are changing so quickly in forests conditions that the behavior has gotten out of bounds and how this becomes its own condition that contributes to the change of climate. The problem is how we effect and how we participate within these natural cycles, and to what extent are we responsible for this or are we in the same position as the bark beetles? We’re going about doing our thing and this is largely an unconscious process.YOUNG: You really are listening to these beetles? I mean, not just sounds they’re making, you’re listening?

DUNN: It becomes a very important role to just simple do that, to listen carefully and purposefully to the conditions of the earth at this point, historically, it really is this is a very extraordinary historical moment that we’re living through. And we’re just obviously beginning to see this sort of passing through the eye of the environmental needle in a way that paying attention to these sensory conditions of our world is really a valuable task.

YOUNG: Audio engineer David Dunn talking with us about recording bark beetles. Thanks very much.

DUNN: You’re very welcome, glad to talk with you.

[BEETLES SQUEAKING, CRACKLING, CHIRPING]

YOUNG: Hear more of the beetles and learn more about the work by David

Dunn, Rich Hofstetter and Reagan McGuire at our website l-o-e dot org.

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “Mother Nature’s Son” from Largo (Warner Bros. 2002)]

Big Blue

(Photo:© Salt Marsh Diary)

YOUNG: From a tiny beetle – to a huge bird. Writer Mark Seth Lender often sees the Great Blue Heron in the salt marsh near his home – the bird’s a regular presence there. Despite this, and the heron’s unmistakable form and great size – Great Blue’s appearance is always a regal and welcome surprise.

(Photo:© Salt Marsh Diary)

Big Blue stilting thinks he has rendered himself invisible. He remains frozen in place the way rabbits freeze on the road as if plain absence of motion will protect him. Or is it watchful waiting, and me the Olympian Eagle whose talons are merely folded out of sight? Or do I give myself more credit than I deserve and Heron only ignores me.

(Photo:© Salt Marsh Diary)

Of all his kind, he alone braves the snow, wind, the ice, and often pays the price. There comes a time when the deep of February arrives and the mercury turns crystalline, dull and misted in the glass, that most of the noble court of Heron pass.

Those that do survive range to deeper cover. I’ve never discovered exactly where they go. I know there are times when they live in the woods, hunting cat-like for mice and voles when they can find them and for whatever else when they cannot. But among the flooded marshlands it is mostly fishes, and when that flood hardens over and fish cannot be found, cannot be had if they are found, what then does Heron do?

A flash a flare a wind of great wings, Heron’s equally Significant Other flushes from the dry spartina leaping, a cool gray fire.

(Photo:© Salt Marsh Diary)

The Mystery of Great Blue Heron and his mate is not solved by science or by sovereignty. They appear, they vanish, they reappear. If the feel of the marsh is emptiness and even the air is still that is the time for patience. Do not hurry. Make no sound. Walking, use stealth. Watching, do not move. When Stillness pursues what is Still, all things are revealed.

[MUSIC: Clare Connors “Flight of The Heron” from Heartlight (Heartlight Creations 2005)]

YOUNG: Mark Seth Lender writes a syndicated column called "Salt Marsh Diary." He watches – and photographs – Great Blue Herons and other assorted wildlife near his home on the Connecticut shoreline.

[MUSIC: Clare Connors “Flight of The Heron” from Heartlight (Heartlight Creations 2005)]

Related link:

Salt Marsh Diary

YOUNG: On the next Living on Earth –

[SOUND OF CUTTING BAMBOO]

YOUNG: Cutting up bamboo to make bicycles.

MURRAY: When you actually take the raw materials and put them together in such a way and make them into something so useful as a bicycle, it’s something that will then color the way that you look – not just at bicycles – but at every product.

YOUNG: Pedaling a new way to use an old resource – next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Clare Connors “Flight of The Heron” from Heartlight (Heartlight Creations 2005)]

YOUNG: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, Marilyn Govoni and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Emily Guerin and Bridget Macdonald. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. You can find us anytime at l-o-e dot org. I’m Jeff Young. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation, supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, dedicated to the idea that all people deserve a chance to lead a healthy, productive life. Information at Gates Foundation dot org. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making, on the Web at Pax World dot com. Pax World – for tomorrow.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth