June 4, 2010

Air Date: June 4, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Slick Technology

View the page for this story

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's ship, the Thomas Jefferson, recently left on a nine-day mission to study subsurface oil in the Gulf of Mexico. Host Jeff Young talks with the ship’s commanding officer Shepard Smith about the high-tech advanced gear that the boat is outfitted with in order to track oil plumes on the move. (02:10)

Eureka, they found it, unfortunately

View the page for this story

Eureka - they found it, unfortunately. Scientists, using an underwater robot, located one of the giant plumes of BP oil looming under the Gulf of Mexico. Host Jeff Young talks with ocean scientist James Cowan of Louisiana State University about their probe’s journey through the subsurface oil. (05:00)

The Gulf’s Other Deep Sea Wealth

View the page for this story

Researchers, trying to make sure deepwater oil rigs in the Gulf Of Mexico don't hit anything under the sea, made a surprising discovery not far from the BP disaster. Host Jeff Young talks with scientist Erik Cordes of Temple University about what he found. (04:50)

A Clean Energy Wake-up Call from the Gulf

View the page for this story

Environmentalist Bill McKibben has long called Americans’ use of fossil fuels a dangerous addiction, and he says the disaster in the Gulf is just a reminder of the damage we do to the planet every day. With oil continuing to gush into the Gulf of Mexico, McKibben tells host Jeff Young it’s time the Obama administration seize the moment as a rallying point for public support of clean energy. (06:20)

Cooperative Videobots

/ Lisa RaffenspergerView the page for this story

Robots have been instrumental in helping scientists tackle the BP Gulf oil spill. They're not only used to monitor oil and chemicals in the water, but they've been important tools in the physical efforts to cap the gushing oil. Using robots to help in emergencies is an emerging field. As part of IEEE Spectrum Magazine and the National Science Foundation's series "Engineers of the New Millennium," Lisa Raffensperger reports on a lab in Minnesota that creates search and rescue robots, including the rough and ready Scout. (04:45)

Emerging Science Note/Voodoo Wasps

/ Bridget MacdonaldView the page for this story

With an ability to paralyze much larger insects, voodoo wasps seem to have magic powers. Living on Earth’s Bridget Macdonald reports on how scientists want to use these parasitic wasps as weapons against agricultural pests. (01:10)

Reversing Desertification

View the page for this story

The winner of this year’s Buckminster Fuller Challenge is an initiative that helps transform packed dry grasslands and savannahs into water-rich pastures. Operation Hope promotes managed cattle grazing, a technique that contradicts conventional beliefs on the effects of animals and soil preservation. Host Jeff Young talks with Allan Savory, founder of the Africa Centre for Holistic Management and the Savory Institute and Professor Zakhe Mpofu, special advisor to the Zimbabwe project. (05:45)

Begrudging the Grid

View the page for this story

Infrastructure in the United States is under-funded and woefully outdated. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood hears two different views on how to reform our ailing grid. Nick Rosen, author of “Off the Grid,” suggests decentralizing utilities, while Scott Huler, who wrote “On the Grid,” wants to stay plugged in and work to improve the system. (16:45)

Gulf Update: Dispersant Nondisclosure

View the page for this story

()

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Jeff Young

GUESTS: Shep Smith, James Cowan, Erik Cordes, Bill McKibben, Zakhe Mpofu, Allan Savory, Scott Huler, Nick Rosen

REPORTER: Lisa Raffensperger

SCIENCE NOTE: Bridget Macdonald

[THEME]

YOUNG: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

YOUNG: I’m Jeff Young. The oil coming ashore on the Gulf Coast isn’t the only problem. We’ll hear from scientists plumbing the depths to learn more about plumes of oil, some thousands of feet beneath the waves.

COWAN: And underwater it looked like spherical globules the size of a marble drifting in the water column.

YOUNG: The damage the oil might do to an undersea world we’re just

discovering.

YOUNG: Also, President Obama renews his push for clean energy. Author and activist Bill McKibben says the oil disaster is a turning point in America’s energy debate.

MCKIBBEN: More than anything else, the thing not to waste here is the chance to explain to Americans why all fossil fuel is dirty. Oil and coal and gas themselves are the problem.

YOUNG: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth - Stick around!

Slick Technology

The Thomas Jefferson, a NOAA research vessel. (Photo: NOAA)

YOUNG: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Somerville, Massachusetts - this is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. The oil washing ashore and moving in sheens in the Gulf is a sickening sight. But it’s only part of the picture. Underwater plumes of oil have been detected, some of them tens of miles long and thousands of feet down. But there is little information on that oil’s chemical makeup, how it’s behaving and how it might affect marine life.

One of NOAA’s top research vessels, the Thomas Jefferson, is on a nine-day mission to help answer some of those questions. We talked with Commander Shep Smith just after the Thomas Jefferson set sail from New Orleans. Smith says the Thomas Jefferson has been equipped to seek out underwater oil.

SMITH: We have deployed a crude oil sensor on what’s called a moving vessel profiler. This is a really clever device that we deploy off the stern of the ship that can take a cast while we’re under way.

So, normally, in order to get physical properties of the water column you would have to stop the ship and lower an instrument down through the water column taking measurements with onboard sensors. This device will allow us to essentially free-fall those same sensors through the water column without stopping the ship, which will allow us to cover a much greater area in the same amount of time.

YOUNG: It sounds to me like you’re actually going to be able to, sort of, track these plumes- not just stopping and dropping place to place, but following it where it goes.

The Thomas Jefferson, a NOAA research vessel. (Photo: NOAA)

SMITH: Clearly, if there is a submerged plume it’s not a stable feature and we would want to continue to monitor and measure the progress of it and the size of it over time.

You know, where we have the highest confidence in a water sample with laboratory analysis, to say that what we’re observing truly is oil and it’s related to the spill, but on the other side we can cover much greater territory with much higher resolution with the sonar systems and the moving vessel profiler.

YOUNG: I mean, it sounds very exciting, it’s like sea hunt for oil, but on the other hand, it’s gotta be a little depressing, knowing that what you’re measuring is signs of possibly great damage to a great resource in the Gulf of Mexico.

SMITH: Well, I think you put it very well, and it’s very sobering. This is actually our second trip out here. When we passed by the spill site on our way in to New Orleans last week we were excited, as you said, getting all this gear ready, we were finally getting to the spill site and when we finally got there it got very quiet and everybody was really quite sober about what we were seeing.

YOUNG: Commander Shep Smith aboard the NOAA research ship, the Thomas Jefferson. Well, so far, three independent research teams have reported finding oil travelling in underwater plumes. Louisiana State University oceanography Professor James Cowan led one of those teams. The LSU’s submersible robot found oil deep off the Louisiana Coast.

Related link:

Find out more about the research vessel Thomas Jefferson

Eureka, they found it, unfortunately

Mid shelf reef in the northern Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: Dr. James Cowan)

COWAN: We went off the mouth of the Mississippi River and were able to detect what appeared to be dispersed oil down to depths ranging from 250-350 feet below the surface and we brought it to the surface and it was clearly dispersed oil. And underwater it looked like spherical globules about the size of a marble drifting in the water column.

YOUNG: So, what do you think is going on about what is keeping the oil beneath the surface rather than coming to the surface?

COWAN: The use of dispersants at depth obviously was a novel idea. I think it was probably a mistake because some of these dispersed oils are getting to a point where they are mutually buoyant in the water column and remaining there without rising.

YOUNG: So, did I hear you correctly? You think the use of dispersants, deep-sea, was a mistake?

COWAN: I absolutely do.

YOUNG: Why’s that?

COWAN: Well, first of all, the dispersants are quite toxic, but at the surface they break down very quickly. At depth we don’t know anything about how long the toxicity remains. We don’t know how quickly the dispersants break down and whether it seems that dispersing the oil has changed, in some way has changed, its specific gravity and might be part of the reason why it’s staying at depth.

Coral and the fish it attracts in the northern Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: Dr. James Cowan)

YOUNG: Now, BP’s chief executive Tony Hayward has weighed in on this notion of oil beneath the surface. He essentially says there is no evidence there are these deep-water plumes. And he says essentially look, oil is lighter than water, it will come to the top. That’s what it wants to do. What would you tell Mr. Hayward about what you’re finding?

COWAN: I would suggest he read an NRC report that was done in 2003 called “Oil in the Sea,” and it shows clearly in there the physics of how oil can be suspended in the water column. And I can understand why he’s saying what he’s saying, but I don’t think the evidence supports it. And certainly there is plenty of evidence in the literature that suggests oil can be suspended in layers and even on the bottom.

YOUNG: And is there any way of mitigating the damage down there? Do we have any way to deal with oil in the deep water?

COWAN: Not to my knowledge. I think that’s going to be something we’re just going to have to see weather in place and degrade over time. I’m afraid that the toxicity of the oil, the fact that it’s mixed with dispersants probably makes the problem more difficult.

Oil in and of itself is a hydrocarbon and there are communities that can consume it, microbial communities in particular. But we don’t know very much about the toxicity of the dispersants, so there’s so many unknowns it’s very difficult to say how this could play out in the long term.

Mid shelf reef in the northern Gulf of Mexico. (Photo: Dr. James Cowan)

YOUNG: Now this area that we’re talking about in the Northern Gulf near the mouth of the Mississippi, this is a place where we have this so-called “dead zone” of low oxygen. How might the oil, especially oil deep in the water, affect the oxygen that’s available to marine life in the water?

COWAN: Well, actually, the dead zone is confined to a much shallower region on the shelf. But the important point is that oil is a hydrocarbon and it’s broken down by the consumption by bacteria and bacteria consume oxygen in the process. If there’s oil added to the mix that’s another serious concern because it could, in fact, increase the decline in oxygen levels in the hypoxic zone.

YOUNG: So what happens if the oil contributes to even lower levels of oxygen?

COWAN: Well, I just think there are more unknowns than knowns right now. And I think that’s because of the novelty of the situation, and where the material is actually going, and what it is when it gets there. So I think we’re all kind of flying by the seat of our pants.

YOUNG: Professor James Cowan of Louisiana State University talking to us about the oil we can’t see beneath the surface of the Gulf. Thanks very much.

COWAN: Thank you.

Related links:

- Professor Cowan’s Gulf Research Database

- NOAA on possible links between the oil and the dead zone of low oxygen in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Gulf’s Other Deep Sea Wealth

Temple University biologist Erik Cordes explores the Gulf of Mexico in search of new, deep coral formations. (Photo: Peter Batson, Deep Ocean Photography)

YOUNG: Just about nine months ago another deep-sea expedition was underway, just 20 miles north from what is now the epicenter of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. And what they found gives us a sense of what’s at risk in the Gulf’s depths. Temple University biology professor Erik Cordes and his team made a remarkable discovery on the ocean floor under nearly 1200 feet of water.

CORDES: We were actually surprised. We’d never been to that site before, and we expected to find something slightly different. What it turned out to be was what we think is the second largest coral reef in the Gulf of Mexico, in deep water.

YOUNG: Wow. And what is a reef like at that depth?

CORDES: They look similar to what you would see in shallow waters. There’s a very large hard coral species that lives down there that’s creating a reef structure that is about 800 feet across in diameter, it’s roughly an oval, it supports a very diverse community.

There are a lot of shrimp that live around there, there are a lot of different fish species that you would find hiding in some of the structure created by the reef, there are a lot of soft corals, as you would see in a shallow water reef, and then there are a lot of species that are very different. There’s something that is called a squat lobster, which, doesn’t have a whole lot of shallow water relatives, something like a cross between a lobster and a crab. There are a lot of other specialized fishes that live in deep water that you wouldn’t normally see in shallow water reefs.

YOUNG: And are these things that are new to science?

CORDES: A lot of them are new to science. Any time you go to a new site in the deep sea you anticipate discovering a number of new species. It’s been less than a year since we brought back our collections from there and so there are only a few things that are definitely new to science but we anticipate that there will be a number of additional new species.

YOUNG: What was the purpose of your research mission? Why were you out there looking for these reefs in the Gulf?

CORDES: It’s an ongoing study that’s funded by the U.S. Minerals Management Service and NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration. And our over-arching goal is to come up with a way to predict where these communities might be.

As the oil drilling moves into deeper and deeper waters we need to understand where there are these high-density biological communities on the sea floor so the Minerals Management Service can actually set up mitigation areas around these communities and prevent the oil rigs from directly impacting them.

YOUNG: So the purpose of this mission was to protect areas like this from off-shore drilling.

CORDES: That’s right. We’re out there in advance of some of these areas being leased to oil companies and we’re trying to locate these areas so that oil rigs aren’t placed directly on top of them.

YOUNG: I guess I don’t need to point out the irony in this situation, where less than a year after discovering this reef you’re talking about oil drilling perhaps negatively affecting it.

CORDES: That’s right. And it’s a major concern for us. But if we hadn’t been out there and if we hadn’t established some of our long-term study sites in this area we would have no way to gauge the impact of an event like this on the deep sea communities.

Temple University biologist Erik Cordes explores the Gulf of Mexico in search of new, deep coral formations. (Photo: Peter Batson, Deep Ocean Photography)

YOUNG: Well, now that we’re hearing about oil in that area not just at the surface, but, for some reason, staying deep in the water, what do you think might happen to these deep water reefs?

CORDES: That’s one of our biggest concerns. There are a number things we could imagine. If you would blanket a reef in oil that would obviously be a catastrophic event. We don’t know that that’s what would actually happen in deep water, we think that it’s more likely that these plumes are dispersed oil and if the oil or some combination of the oil and dispersants are hitting that site, there could be some serious damage to these coral reefs. We’ve seen how fragile these ecosystems are from a lot of the shallow water impacts and we’re really just hoping we don’t find something like that.

YOUNG: This strikes me as an amazing example of how little we know about the floor of the ocean. Even in the Gulf, where I guess we know it pretty well.

CORDES: Yeah, the Gulf is probably one of the best-studied deep-water basins in the world simply because there’s been so much human activity with off-shore oil drilling that’s been ongoing there for a really long time.

But even in the Gulf of Mexico, we’ve seen barely a fraction of the sea floor. We’re really at the early stages of our understanding of the deep sea in general, and in particular some of these coral communities, which are only recently being discovered.

YOUNG: Dr. Erik Cordes at Temple University, thank you very much.

CORDES: Thank you.

Related link:

Cordes Laboratory for Deep Sea Ecology

YOUNG: Just ahead - Bill McKibben on how the oil disaster might change the nation’s political landscape. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Steely Dan “Gaslighting Abbie” from Two Against Nature (Giant Records 2000)]

A Clean Energy Wake-up Call from the Gulf

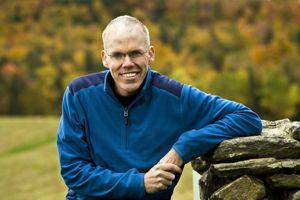

Environmental activist Bill McKibben has been a prominent voice on the dangers of fossil fuels. He says the gulf catastrophe is a reminder of our daily damage to the planet. (Photo: Nancy Battaglia)

YOUNG: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. After more than a month of taking hits from the BP Gulf oil disaster, the Obama administration is taking a tougher stand. Attorney General Eric Holder announced a criminal investigation into BP’s behavior leading up to the April 20th explosion.

And, in a speech in Pittsburgh, President Obama proposed rolling back tax breaks for oil companies. And he pledged a renewed push for the clean energy and climate change legislation that has stalled in the Senate.

OBAMA: The votes may not be there right now, but I intend to find them in the coming months. I will continue to make the case for a clean energy future wherever and whenever I can…

[CLAPPING]

OBAMA:…I will work with anyone to get this done. And we will get it done.

YOUNG: Author and activist Bill McKibben is, so far, not impressed. McKibben has been an influential voice in the environmental movement for decades. Two years ago he had hopes that the Obama administration would act on climate change. But McKibben says the president has not yet risen to the challenge.

MCKIBBEN: He’s making a start. But the sense of urgency isn’t there yet, and we need it from him, in part because he’s been much too willing to cuddle up to industry. Remember it was only two weeks before Deepwater Horizon exploded beneath the Gulf that the President himself said, ‘no worries, this stuff is safe now’. Well it’s not safe. It’s not safe in the Gulf and it’s not safe in the atmosphere.

And we need him to be leading this charge, rhetorically, legislatively. We need him to put into use that great army of people that he assembled for his election, the millions of people who gave money, who knocked on doors, who formed the biggest Democratic vanguard that we’ve really seen in this country. We need them out on the hustings working for change in energy.

YOUNG: Rahm Emanuel, member of the president’s cabinet, is fond of saying that a crisis is a terrible thing to waste- that you have to strike when the iron is hot. Do you see them doing that?

MCKIBBEN: So far, at best the president has said, well, we’ll use this as a way to remind ourselves that we need to take action like the sort of bill before the congress right now, the Kerry-Lieberman bill. That’s a very, very small start on the very big job we need to do.

And more than anything else, the thing not to waste here is the chance to explain to Americans why all fossil fuel is dirty. Oil and coal and gas themselves are the problem. Why, if that oil had made its way up to the surface and through a pipeline to Louisiana and been turned into gasoline in a refinery and put into the tank of your car, why the damage it would do spewing out of the tailpipe is every bit as bad as the damage that it’s doing now unleashed in the Gulf.

YOUNG: Many of the main-stream environmental groups, especially those very active inside the beltway in Washington, they seem pretty much tied in to this American Power Act, the Kerry-Lieberman bill that’s in the Senate now. The core of that is built around this compromise that there would be some expansion of off-shore drilling in exchange for some kind of a cap on greenhouse gasses. Here’s Dan Lashoff with NRDC explaining their position on that.

LASHOFF: We think that incentives for states to expand off-shore drilling have no place in this bill. But what makes this bill important is its fundamental limits on carbon pollution. You know, obviously deeper reductions faster would be better, but it’s a good start on what we need to do.

Environmental activist Bill McKibben has been a prominent voice on the dangers of fossil fuels. He says the gulf catastrophe is a reminder of our daily damage to the planet. (Photo: Nancy Battaglia)

YOUNG: So, Mr. Lashoff there making the point, he’s like, ‘yeah we don’t like off-shore drilling, but we gotta get some kind of action on climate change,’- is that the route to go?

MCKIBBEN: I think at this point any bill that includes more off-shore drilling is a non-starter. People like Dan are terrific lobbyists—we need to give them something to lobby with. The reason we’re not getting further in Washington, the reason that we’re making bad compromises with industry on these bills is because there’s not enough public outrage, and not enough public action.

And when we have it, we’ll be able really to let science dictate the terms of what needs to happen. Because at bottom, this is not a negotiation between the energy industry and environmentalists, or between Democrats and Republicans, or anything else- it’s a negotiation between human beings on the one hand, and chemistry and physics on the other. We see a mile down beneath the surface of the Gulf, what happens when you try to override physics and chemistry.

It’s not a pretty picture there, and it’s not a pretty picture up in the atmosphere. So, as tough as the political reality is, we’ve got to pay some attention finally to what the real-world is telling us, not the sort of set of fantasies we’d like to believe.

YOUNG: So what should those in the environmental movement be doing now if they wish to build a platform of public support for action on clean energy?

MCKIBBEN: We’ve got to organize, organize, organize. We’ve got to keep reminding people that there’s no problem more pressing than what’s going on in the atmosphere. If all we perceive is the horror that’s going on the Gulf, well that’s horrible enough, but the outcome will be that we’ll spend a lot of time worrying about what exactly type of technology to put on the bottom of oil wells, what kind of blowout preventers we need, how much BP should be punished for its very egregious sins, on and on and on. All important questions but nowhere near important as taking that horrible site and using it to get into our imaginations the invisible slick spreading across the atmosphere.

YOUNG: Bill McKibben, thank you very much for your time.

MCKIBBEN: Thank you so much.

YOUNG: Bill McKibben is scholar in residence at Middlebury College in Vermont. His new book is Eaarth: Making A Life On a Tough New Planet.

Related links:

- More from Bill McKibben

- President’s recent remarks on energy at Carnegie Mellon

Cooperative Videobots

Researcher Duc Fehr holds a remote and a very tiny, very tough robot. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

YOUNG: No person can work where the oil is spewing into the Gulf a mile beneath the sea. Engineers are relying on robots to stop the spill. Robots also come to the rescue on the surface - helping search teams burrow through rubble to locate survivors after a disaster. In a Minneapolis lab designers built a tough robots that can even be thrown through a window. Plymouth Minnesota SWAT team Sgt. Chris Kuklok says it helps police do their jobs.

[MUSIC: Tommy McCook: “Way Down South” from Blazing Horns: Tenor In roots (Blood And Fire 2003)]

KUKLOK: Patrol officers were called to a residence where a male was staying, possible suicidal. Patrol officers showed up there and smelled a really strong odor of propane coming from the house and they decided to back off. They used the robot to make entry basically in the first floor. They used it and drove it down to the basement area and cleared that as well, where they found he had set up some propane tanks to explode, and so the robot was pretty integral in just helping them clear as much as possible inside the structure without having to send bodies in harms way unnecessarily.

YOUNG: As Lisa Raffensperger reports for the IEEE Spectrum Magazine and the National Science Foundation series "Engineers of the New Millennium,” and has the story.

[OBJECT BOUNCING ON THE FLOOR, DRILLING NOISES]

RAFFENSPERGER: Duc Fehr is a PhD researcher in the Center for Distributed Robotics at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities—the lab that invented the Scout robot.

FEHR: This is the Scout robot, it’s probably the most important robot in our lab, it’s basically the one that kind of made the lab. It is a very tough robot, you can toss it around like this--

[ROBOT CLUNKING AGAINST FLOOR]

--and it still works.

RAFFENSPERGER: About the size of a Coke can, the remote-controlled bot carries a video camera between its rubber wheels. It was designed as a rugged reconnaissance tool for military, police, and rescue agencies—over 100 of which are already using it worldwide, including the U.S. military in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Plymouth, Minnesota, SWAT team also uses a Scout, and Sergeant Chris Kuklok says it has given his team a first set of eyes on dangerous situations.

[METAL DOOR CLOSING, LOCK OPENING, DOOR SLAMMING]

Researcher Duc Fehr holds a remote and a very tiny, very tough robot. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

KUKLOK: You don’t eliminate all the risk you just try to minimize it.

RAFFENSPERGER: The Scout is just one of the robots that has been, or is being, developed at the Center for Distributed Robotics.

PAPANIKOLOPOULOS: This is the place where we’re building the robots, we’re testing them, we modify them—it’s where all the action is. Where the magic happens.

RAFFENSPERGER: Nikos Papanikolopoulos is director of the center. The Scout has been his biggest success, spawning its own company, but its celebrity belies the real emphasis of the lab—creating robots of diverse shapes, sizes, and specialties that work together in a single team. Those diverse robots, at the moment, include an amphibious robot, a transforming helicopter bot, and a big robot that can climb stairs and deploy smaller bots.

Finally, there’s the Adelopod. It’s unique, in that it tumbles- like a crab might move, if it had only two legs.

[MECHANICAL WHINING]

PAPANIKOLOPOULOS: We try to build better systems. And I will argue that we can build robots which are extremely good—we can build robots that could fly, robots that can move on the ground. How are we going to have tons of them working together being integrated with the human? I have no answer.

RAFFENSPERGER: No answer—yet. But it’s a problem the lab is hard at work on. One solution they’re exploring is programming the robots to follow one another, using only their video cameras. Because of their size, small robots may lack the equipment to communicate with each other, explains PhD student Hyeun Min.

MIN: You know, small robots have very limited resources, so if they can follow a big robot which has much resources, many resources, then it would be easier to deliver them.

RAFFENSPERGER: And there are strengths of heterogeneous robotic teams. Each robot can specialize on one or two tasks, and rely on other robots to help with the rest. It’s teamwork—a lot like the teamwork behind the scenes to create these robots, says grad student Andrew Carlson.

CARLSON: We had kind of lab meetings, different things, where we’d brainstorm different wild ideas for robots, anything and everything we could come up with.

PAPANIKOLOPOULOS: So it’s a playground, it’s a robotics playground.

RAFFENSPERGER: And the schoolyard lesson, for these robots, is playing well with others. They’re learning. For Living on Earth, I’m Lisa Raffensperger in Minneapolis.

[MUSIC: Darcy James Argue “Redeye” from Infernal Machines (New Amsterdam records 2009)]

YOUNG: Lisa Raffensperger originally reported this story for the series "Engineers of the New Millennium: Robots for Real", a co-production of IEEE Spectrum magazine and the Directorate of Engineering for the National Science Foundation.

Related links:

- Center for Distributed Robotics at the University of Minnesota

- IEEE Spectrum and National Science Foundation “Engineers of the New Millennium: Robots for Real” series

[MUSIC: Darcy James Argue “Redeye” from Infernal Machines (New Amsterdam records 2009)]

Emerging Science Note/Voodoo Wasps

YOUNG: Coming up – how grazing in the grass can restore degraded African landscapes. But first, this note on emerging science from Bridget Macdonald.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

MACDONALD: Not everyone believes in Voodoo, but voodoo wasps really do cast a spell. Their venom can turn other insects into zombies, and a group of scientists wants to harness their powers.

[THEME]

MACDONALD: They’re one of the tiniest insects on the planet, but there’s more to voodoo wasps than meets the eye: with a single sting, they can paralyze insects that are giants by comparison.

Now a team led by the University of Rochester has decoded the DNA of three species of parasitic wasps.

The scientists have identified which genes tell the wasps to attack a particular insect, in hopes of recruiting them to fight agricultural pests. The army of wasps would be a natural alternative to chemical pesticides.

And scientists think they could provide other health benefits as well. If the wasps were trained to target insects that carry deadly bacteria, they could help stop the spread of diseases like malaria. Our future flying aces could be swarms of parasitic wasps. That’s this weeks Note on Emerging Science, I’m Bridget Macdonald.

[THEME]

Related link:

Read the paper: Functional and Evolutionary Insights from the Genomes of Three Parasitoid Nasonia Species

Reversing Desertification

No cattle grazed the plot on the left. On the right, hooves broke up the soil and animal waste provided fertilizer. (Photo: Africa Centre for Holistic Management)

YOUNG: Conventional wisdom has it that cattle are bad for the land. They pack soil so hard that plants can't grow. But sometimes what we think we know, isn’t necessarily so.

A non-profit working in Zimbabwe is using livestock to bring dry, denuded, desertified land back to life. The Africa Center for Holistic Management just won the Buckminster Fuller competition. It rewards those who apply Fuller’s famously unconventional thinking to environmental problems. Professor Zakhe Mpofu and wildlife biologist Allan Savory developed the Center’s livestock land remedy. Welcome to Living on Earth!

MPOFU AND SAVORY: Thank you.

YOUNG: So isn’t desertification driven by over-grazing? How can cattle be part of a solution when we’ve been thinking they’re the problem?

SAVORY: Yes it’s in the public media and the myths and so on, livestock cause desertification and they have historically. And I used to condemn them totally until I found from my own research that I was wrong. Now I defend a completely different position. Livestock are the only tool available to science with which to reverse desertification. It depends how you manage them, how you run them.

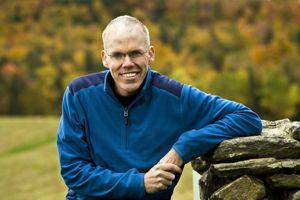

Wildlife biologist and farmer Allan Savory developed the idea of brief cattle grazing to mimic wild grazers on the savannah. (Photo: Savory Institute)

YOUNG: Professor, help us understand a little more how this actually works. How do you keep the animals where you want them?

MPOFU: We keep the animals by having the herders keeping them where we actually want them, following the plan that has been devised. Because we planned two times a year, right at the beginning of the growing season. We planned for the growing season and we planned for the dry season. So that the herders then follow the plan that has been drawn.

SAVORY: When we realized we had to mimic the animals we also realized we had to have some planning process that could treat each situation as unique. So we actually train people very simply to get the livestock in the right place for the right time for the right reason and to keep them bunched, in their bunching behaviors, though predators were around.

And our cattle, if you can picture this, are over night in lion-proof, predator-proof corrals. Because we are predator friendly in what we are doing, we want the predators. And then during the day they are herded to a plan and the herders just herd them very, very calmly in a bunched manner. And that plan leads to no plants or soil on our land being exposed to the animals for more than 3 days—ever—and then not re-exposed for 6-9 months.

YOUNG: But what’s different about the use of land by cattle who are bunched together versus those who roam more broadly?

Professor Ntombizakhe Mpofu directs research at the Africa Centre in Zimbabwe. (Photo: Savory Institute)

MPOFU: The animals that are bunched together, what they do is they are bunched together, they chip the land, the soil becomes loose. It allows air to get into the soil. It allows rain to soak in as when the rain comes. So what we have done now is to turn almost desert lands into thriving grasslands.

SAVORY: The Dimbangombe Ranch that Zakhe and the others are managing and running is a microcosm of the biggest problems in the world: poverty, violence, droughts and floods-almost perennial now. Now, what we’ve done there is to return it to animal-maintained rather than rest and fire grasslands and savannah.

So we’ve increased the livestock four times and because of that we now have an abundance of grass, even in a dry year we’re not worried at all about drought and forage production. And we now have open water with water lilies, fish a mile above where we’ve ever known water historically in the river system, right through the dry season.

YOUNG: It kind of makes you wonder why people haven’t been doing it this way before. Why do you think it took so long to discover this way of doing something as elemental as herding cattle?

MPOFU: My background, personally, is in animal science- I’ve trained in animal science. And I looked at it and said to myself, ‘it looks too simple to be true’.

YOUNG: Uh huh.

MPOFU: And that’s what it is. And, that’s why I think most people have been skeptical and said even said, ‘Prove it- whatever it is you are saying works, let’s see you proving it’.

No cattle grazed the plot on the left. On the right, hooves broke up the soil and animal waste provided fertilizer. (Photo: Africa Centre for Holistic Management)

YOUNG: What has participating in this meant for you?

MPOFU: It has meant quite a lot for me because I have seen how communities can be changed. Their lives can be changed because if you look at this, in this issue, there is the productivity of the land, there is the productivity in terms of livestock production, but there is also environmental issues as well as economic and social issues. In this program what fascinates me about it a lot is it also has social aspects which most people don’t consider. You look at communities these women and children who are affected by this program, one the main outputs of it is the improvement in water.

YOUNG: In water?

MPOFU: Yes. As the rain comes, because the ground is covered, more water soaks into the ground. As it soaks into the ground, the water level goes up. And water is a big issue in the rural communities. Women walk distances with their children to go and fetch water.

Cattle spend only three days on a patch of desertified soil. (Photo: Africa Centre for Holistic Management)

As the land improves more water becomes available, and then the labor of fetching water from long distances becomes not an issue anymore. So it’s not only about land, it’s about land and people. So you have an issue of increasing crop productivity. You have water. And this is all in terms of contributes in terms of reducing poverty. So it looks like we have an answer for Zimbabwe and for the world, really.

[MUSIC: Hugh Masakela “Grazin In The Grass” from Live At The Market Theater (Four Quarters Records 2007)]

YOUNG: Professor Zakhe Mpofu is a special advisor to the Africa Center for Holistic Management. Allan Savory founded the Savory Institute for Holistic Management. There’s more on their project at our website, loe.org

Related links:

- The Savory Institute

- Africa Centre for Holistic Management

- 2010 Buckminster Fuller Challenge

YOUNG: Coming up: two writers tackle our infrastructure system from inside and out: the grid, the bad and the ugly. Just ahead on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Al Kooper/Shuggie Otis: “Double Or Nothing” from Kooper Session: Al Kooper Introduces Shuggie Otis (Sony Music 1969)

Begrudging the Grid

On the Grid by Scott Huler

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jeff Young. A water main breaks, a storm downs a power line, and suddenly we are without. These temporary inconveniences are the few times we really appreciate the grid we take for granted--and consider the vulnerability of our water and power systems. Two new books examine the infrastructure of the United States – they are, “On the Grid,” by Scott Huler, and Nick Rosen’s “Off the Grid.”

As you might guess from those titles, the authors have some very different ideas. So we invited them onto the program to grapple with the grid. Living on Earth’s Steve Curwood refereed our discussion with Scott Huler and Nick Rosen.

ROSEN: Hi.

HULER: Hi, it’s good to be here.

CURWOOD: So I’m looking at your book Nick Rosen, yes the title is, “Off The Grid,” but also it says, “Inside the Movement for More Space, Less Governance and True Independence in Modern America.” In brief, what is your book about?

ROSEN: Well literally, “off-grid” means living without utilities, but also has a metaphorical meaning, which is living kind of outside the system, or half-in and half-out of the system, and so going off the grid is something that more and more people are doing because it’s getting easier.

The technology is allowing it—the low energy fridges, the more efficient solar panels, and the fact that it’s becoming more acceptable and you’re allowed to “tele-work,” you know, be on the internet in the boonies, and so people are exercising this freedom, some of them are.

Author Nick Rosen. (Photo: Dafydd Jones)

CURWOOD: And Scott Huler your book is called “On the Grid: A Plot of Land, an Average Neighborhood and the Systems that Make Our World Work.” Tell me in brief, what is your book about?

HULER: My book is about all of the systems that the people in Nick’s book want to do without. My book starts from my house and looks up and says, ‘look at all these things sticking out of my house, these wires, these tubes and these pipes, where do they go and how do they work,’ and it asks questions like, okay we had a drought here in Raleigh, a drought of biblical proportions where it just stopped raining for months and in the middle, at the worst part of that drought, when we were almost out of water, you could turn on your tap and brush your teeth for 20 minutes, with the water running while you were humming Mozart and you would never run out of water.

And it asks questions like, ‘how on earth is that possible? How could it be that that happens and you flush your toilet and you never have to think for five minutes about what happens to that stuff, and how can that be,’ and is that a good thing or a bad thing, and above all just how does it work and how did we get to this place and what next.

On the Grid by Scott Huler

CURWOOD: Well it seems both of you would agree that for 99.9 percent of us, we all would be looking for electricity and water in our lives. You two don’t disagree on that, do you?

HULER: Oh not a bit.

ROSEN: I have a small quibble with that. Living off-grid doesn’t mean doing without electricity and water--it means providing your own electricity and water. And a lot of people would say, well why on earth would I want to do that? But there are quite a few people who think they can answer that question. They say they want to do that because of the ever-increasing price of electricity, or because they don’t trust the system to deliver them electricity and clean water and the other things that we traditionally rely upon the state to provide.

And they’ve come to distrust the state and authority and the financial system and they just want to provide for themselves. It’s not so much self-sufficiency, although for many that is a factor, it’s self-reliance.

CURWOOD: So Scott Huler what about this. In fact, within the last, say six weeks, right where we are at the studios of Living on Earth, we’ve had to boil our water because the water main system failed, we’ve had power outages, and of course almost everyday we have traffic jams. So these folks who are looking to get off the grid; how much a bad thing do you think that is?

HULER: I am in favor of all kinds of, sort of, adjunct technology and technology that frees you from paying companies who you don’t trust or anything like that. If you want to generate your own power I’m in favor of that. If you want to clean your own water rather than using municipal water I’m in favor of that too.

But no matter how easy the systems get and how great the systems get, I think it’s still going to be a lot more trouble for each person to do it than to do it as a group. And yes as you pointed out, Steve, in Boston you had that shocking water main break. The collar they put on that water main was seven years old! It’s unspeakable that something like that should be breaking.

And that demonstrates how bad we are getting at paying the taxes to take care of these systems that take care of us. But I much more strongly trust a municipal water system and the people who run it and who have degrees in running that, then I would trust my neighbors to take good enough care of their sewage so that my water, if it was coming from a well wasn’t fouled and---

ROSEN: Well you say that—

HULER: Go ahead.

ROSEN: Well you say you trust the municipal water authorities but the fact is, as I describe in my book, Associated Press did a survey of most of the major municipal water systems and they found that the water was polluted with all sorts of drugs that have passed through the human body and then not been taken out by the filters. So actually I think that trust is a bit misplaced. And I’m not saying we should all stop drinking the tap water immediately, but what I am saying is that I can completely understand somebody who wants to provide their own water.

CURWOOD: And let me be sure I understand what you’re saying, Scott. Many suburban areas just a little beyond the reach of, say, a main sewer system, they use septic tanks and leach fields and they have wells. What kind of risk do you think these people are at?

HULER: I don’t think they’re at an enormous risk. When you have septic systems and you have, as you say, wells, and you have government people coming out to manage that and make sure they’re installed properly, I’m in favor of all of that. I’m just saying that living in Raleigh, N.C., in my quarter-acre lot, I don’t care to get off the sewer system and I don’t care to get off the municipal water system and I’ve just spent two years hanging around with the people who manage and run those systems and I couldn’t have come away more deeply impressed with the work they do under very difficult circumstances with never enough money.

And, though, I certainly see Nick’s point that there are more and more dangerous substances showing up in those systems, and we’re always running behind to catch up with a new thing that we found, that’s always been the case. I don’t think that that indicates some sort of malfeasance on their part and I don’t think that it indicates they’re not doing well enough. I think that it indicates there’s something new and especially when you look at these personal care products or pharmaceuticals, that’s us putting that stuff in the water, that’s not the treatment people throwing it in the water, it’s us putting it in the water. We could solve that problem by using less of those products quicker, than we could by waiting for them to find a way to pull out what we’re dumping.

ROSEN: I don’t really buy that argument that we have got to be a bit careful about where we urinate after we’ve take a contraceptive pill, for example, because we know that that’s not going to be filtered out by the water system. I think it’s an all or nothing case. If you’re a big water company you either say you can do the job or you get out of town. You can’t be selective and say, ‘well we can do it, but just not that bit.’ You know, I have also got respect for the kind of middle-ranking engineers who keep the system going. But the fact is that the history of the electricity business and the water business is a history of corruption and devious business practices, which are aimed entirely at maximizing the profit of the businesses and really are not specifically designed to be in the interest of the public.

CURWOOD: Woah, woah, woah, okay Nick, wait a second. That’s a very broad brush to tar an industry. So please explain, at least give us an example here.

ROSEN: Enron is an example of what happens when we just let the utility companies get completely out of control. But Enron is just indicative of the state of the overall electricity industry because at the moment the industry is not sufficiently regulated and spends as much time trading electricity with itself as it does supplying the electricity it produces to ordinary members of the public.

HULER: I couldn’t agree more with that. That something like Enron is a great example of un-regulated industry gone wild. And your examples of what’s wrong with industry, to me, that’s human history. There’s a shock for you that when you look at people who amass power and amass control they suddenly stop acting in the public interest and start lining their pockets. This is not a stop the presses moment. This is reality; this is how humans beings act.

And so I’m totally in favor of enormous regulation and enormous public control but I’m still not convinced that the way to move forward is to disassemble the grid. There’s an enormous part of the world that would hear you saying ‘I think that sewage treatment or municipal water supply is a huge scam,’ people would weep to hear you --who have it-- talking about, ‘I want to do without it,’ whereas a billion and more people in this world would give an arm to have their children, give their children access to the water than any Western European or American could get by doing nothing more complicated than turning on the tap.

ROSEN: Well that’s a very interesting point, because if you’re talking about the couple billion people in the world who are not on any grids, then I would say of them, that in places where the grid does not yet exist, there is no longer any need to invent it. The grid, as it exists in America, the electricity, the water, the roads, is an extraordinary technological achievement, but it may turn out to have been of its time, and that time may be about to pass. We have found that in fact we can do a much more efficient job by creating energy locally, much closer to where it’s used. I’m not talking about in each individual building here, I’m talking about something called micro-grids, but it is very much literally a case of returning the power to the people, rather than allowing it to be centralized in the hands of a few producers.

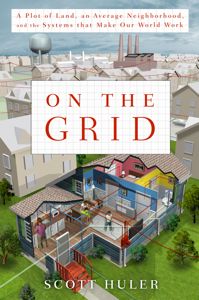

Author Scott Huler. (Photo: www.scotthuler.com)

CURWOOD: After studying the grid you both came to the conclusion that it is tremendously vulnerable. Knowing this, what should we do? And what have you done with this knowledge? Let me start with you Scott.

HULER: The most important thing that I think we can do is take a seriously look at our tax structure. I think we need to start paying taxes and taking care of these things. I guess I’m going to be labeled as a “tax and spend liberal” but I’d love to see us pay more taxes and take more care of it through government oversight.

CURWOOD: Let me ask you the same question Nick Rosen. After studying the grid you say it’s tremendously vulnerable, so what should we do, and what have you done with this knowledge yourself?

ROSEN: So what I would say is what we should do is be aware that it’s an option, that living off the grid is an option that you don’t need to be scared of. That it really is quite doable. I quite agree with Scott, you really wouldn’t want to do it all yourself. But I wouldn’t mind being part of a community which supplied its own power and water and where one or two members of that community were more involved in maintaining those systems than the rest of us.

CURWOOD: And what would be the advantage of that?

ROSEN: There are many different reasons that people give you for living off-grid. One of them is a fear of peak oil, or a fear that the system is going to collapse in some way. There’s an argument that says, ‘I don’t really want to spend my life maintaining my mortgage and paying the utility bills when I could live somewhere a bit smaller and a bit less expensive without any utility bills, and then I don’t have to work so hard.’ So there’s an element of freeing yourself from the cares of society.

CURWOOD: Scott Huler, you write that, “you can’t go off the grid anymore, we’re all on the grid.” Can you explain what you mean by that?

HULER: Yeah, I think that in a larger sense I think it’s almost impossible to go off the grid and I would make “air quotes” if you could see me because all these people who are off the grid have their satellite internet technology, and of course the internet is powered entirely by grid power, and they drive on paved roads when it’s time for them to go into town and get their groceries, the groceries they don’t grow themselves, so I question whether you really even can get off the grid anymore.

Off the Grid by Nick Rosen

CURWOOD: Nick Rosen, as we were getting ready for this interview, the thought came up that off-the-griders are seen as extremists, you know, these are people who are really pretty upset with society and want to check out as best they can. How accurate is that?

ROSEN: Some of them are. For some people that is completely accurate, and I met some very angry and very paranoid people, intelligent, but yet frightening in their mistrust of the system, and in their belief that, for example, that 9-11 was a George Bush conspiracy, and that was given to me twice as the reason why certain individuals that I interviewed in the book are living off grid.

And I find that sad and worrying. But equally the majority of people who live off the grid, the ones I met anyway, are doing so for different reasons and they’re not doing it in a solipsistic or hermit like way, they’re doing it as part of a group, part of a society of other people living off the grid. I don’t mean necessarily that they’re living in a commune, but they might well be living in an off-grid community where hundreds of others like them are also living that way.

CURWOOD: It seems to me both of you are saying we need to be aware of how and where we get our power, our water, how we travel, the resources. If I listen carefully, you’re both saying the same thing. You can’t really get completely off the grid and yet you can’t simply mindlessly be on the grid and not pay attention to the consequences of our actions.

ROSEN: The one area where I disagree with Scott, although I do admire his focused examination of the grid, I think he goes a little bit too far in kind of championing the grid, and I think that Scott is a bit of a cheerleader for the grid. Whereas when he charts its shortcomings I’m very much in agreement with him. But when he holds it out as something worth spending two trillion dollars to preserve I’m not so sure I’m him there.

CURWOOD: Scott?

HULER: Well I think Nick’s exactly correct. I am nothing short of a cheerleader for the grid. I spent two years looking at this stuff and saying, ‘oh my God how did this happen and what an amazing accomplishment it is.’ Where it’s going in the future I can’t be sure of. Neither were the people who I spent all this time with. They’re not sure. But they all believe that they can manage it and they can keep it working and keep it working well. I think that Nick.

ROSEN: They can, they can keep it working Scott, but at what cost? Can you imagine all the different ways that that money could be spent in order to set up local systems for dealing with water and waste disposal, in order to set up small-scale electricity production. You could run the entire country in a completely different way.

HULER: You could...I’m not convinced that that would be better or cheaper. It might be, and it’s well worth studying. I think that when you can build—I just saw Raleigh open up a 90 million dollar water treatment plant and what they can do there, at the 15-20 million gallons per day rate, they can do enormously wonderful things. I’m not sure that you can do that if you’re going to do it all small scale. Maybe you can, I’m willing to be convinced, but I haven’t seen that. Nor have I seen the structure by which you would put in 50 sewer plants to replace our one sewage treatment plant and that leaves me basically trusting the fertilizer that they produce, the soil treatments they produce.

These resource issues are the questions we’re going to be asking every day of our lives, and so I wrote On the Grid so that you would be aware where does my electricity come from, where does my water come from, where does my sewage go, where does my trash go, who paves my roads and how and why. If you have a basic understanding of how it works at least you’ll be prepared to be an enlightened citizen, and an informed citizen in the debates that will come, that will make the small disagreements that Nick and I have had here look like playing patty cake when people really start talking about spending real money.

CURWOOD: Scott Huler’s new book is called “On the Grid: A Plot of Land, an Average Neighborhood and the Systems that Make Our World Work.” And Nick Rosen, your book is called “Off the Grid: Inside the Movement for More Space, Less Government and True Independence in Modern America.” Well I want to thank you both for taking this time with me today.

HULER: It was a pleasure to be here.

ROSEN: Thanks very much.

Related links:

- Learn more about off-the-grid living on Nick Rosen’s website

- Check out other works by author Scott Huler

- Nick Rosen's website

[MUSIC: Off The Grid: Thievery Corporation “Scene At The Open Air Market” from Sounds From the Thievery Hi-Fi (ESL Music 1997)]

Gulf Update: Dispersant Nondisclosure

A plane sprays chemical dispersants over the oil slick created by the Deepwater Horizon explosion. (Courtesy of Flickr Creative Commons)

YOUNG: Next time on Living on Earth, our Sister Show, Planet Harmony, explores a city playground with a big mission.

CHRISTIAN: And so what we tried to do was develop something that was beautiful, green. I call it an oasis in the middle of the city- an experience that urban children don't usually have.

YOUNG: You can hear more about the environmental issues facing minority communities, and join the discussion yourself at Myplanetharmony.com– and listen to the report next week on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Off The Grid: Thievery Corporation “Scene At The Open Air Market” from Sounds From the Thievery Hi-Fi (ESL Music 1997)]

YOUNG: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Ingrid Lobet, Bridget Macdonald, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Smith, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Mitra Taj, with help from Sarah Calkins, and Sammy Sousa. This week we welcome our new interns, Amanda Martinez and Meghan Miner. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Steve Curwood is our executive producer. You can find us anytime at LOE dot org – and check out our new Facebook page – PRI’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young. Thanks for listening.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth