August 27, 2010

Air Date: August 27, 2010

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bye-Bye Bayou

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Katrina took their homes. BP’s spill took their jobs. And coastal erosion is taking the very land their ancestors called home for centuries. But the tiny, Native American community of Grand Bayou Village is determined to hang on. Host Jeff Young returns to Louisiana’s Plaquemines Parish to find out how the people of Grand Bayou he met in the wake of Hurricane Katrina are doing five years after the storm. (11:45)

The Bayou Ballot Box

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

The third congressional district of Louisiana stretches over most of the state's coastline. Storm protection, the role of the offshore oil industry, and the rapidly-disappearing coastline are bread and butter topics for voters there, and host Steve Curwood checks in with the volunteers of political campaigns to understand how the district's problems are turning into hope at the bayou ballot box. (10:20)

Long Term Gulf Restoration

View the page for this story

The Gulf region faces a laundry list of environmental problems, from coastal erosion to oil cleanup. President Obama recently selected the Secretary of the Navy, Ray Mabus, to come up with a long-term Gulf restoration plan. Host Jeff Young sat down with Secretary Mabus who says this administration's commitment to the Gulf will be judged by results. (05:40)

Where Are They Now: Bob Rue

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

Bob Rue put up hilarious signs to ward off robbers and guard his store against looting after Hurricane Katrina. Host Jeff Young meets up with Rue to hear how his business is faring now and what’s changed for him since 2005. (02:00)

Still Seeking Environmental Justice in New Orleans

View the page for this story

If Hurricane Katrina exposed racial biases in public policy, environmental justice advocate Beverly Wright says post-Katrina rebuilding has shown not much has changed. The Dillard University professor says the whiter and richer communities in New Orleans have better access to grocery stores and hospitals and have gotten better levee protection from the Army Corps of Engineers than communities of color. Host Steve Curwood talks with Wright about her personal and professional experiences in the five years since the hurricane hit her home in New Orleans East. (07:00)

Green Living in New Orleans

/ Jeff YoungView the page for this story

The Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans was destroyed during Hurricane Katrina. Now, with the help of the Brad Pitt-backed organization Make It Right, some residents are trickling back into their old neighborhoods to live in newly built houses. Robert Greene shows host Jeff Young his new environmentally friendly house that was built right where his old house used to stand. (03:00)

Trumpeting New Orleans' Rebirth

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Trumpeter preacher Hack Bartholomew lost a church but strengthened his faith after surviving Hurricane Katrina. Host Steve Curwood listens to his jazz gospel tunes and talks with him about New Orleans' rebirth. (07:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood & Jeff Young

GUESTS: Raymond Reyes, Nicholas Bartholomew, Rosina Philippe, Matt Bethel, Ray Mabus, Bob Rue, Beverly Wright, Robert Green Sr., Hack Bartholomew

REPORTERS: Jeff Young, Steve Curwood

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

YOUNG: And, I’m Jeff Young. Five years after Hurricane Katrina we look at the recovery, and restoration of the Gulf Coast. We visit the tiny community of Grand Bayou – despite the storm and the oil, it’s still hanging on – barely –

PHILIPPE : This is our place in the universe, this is where the creator set us down. In spite of all the impacts that have come at us both natural and human induced, we’re still here. This is where we belong.

CURWOOD: Also - finding the silver lining to the dark clouds -

BARTHOLOMEW: That storm, at the time it was happening, it didn’t look too good. But in the end it was very good. Everybody was like, putting their shoulders together and doing this thing, helping this city to come back.

CURWOOD: Katrina and Rita plus five - this week on Living on Earth! Stick around.

[MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Bye-Bye Bayou

“This is our place in the universe.” Rosina Philippe can see her ancestors’ burial mounds from her kitchen window. But rising seas and sinking land could put them under water in a generation. (Photo: Jeff Young)

YOUNG: This is Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood, and we’re reporting from New Orleans. Five years have passed since the storms that flooded this city, reshaped the region and left indelible images in our minds. The long climb back from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita became even harder this April when BP’s doomed rig let loose a torrent of oil. Today we revisit some of the people and places we reported on in the wake of Katrina. We’ll hear who’s made it back and how the Gulf Coast might recover from the storms, the spill and the grinding, constant threat of coastal erosion.

Shrimping, oyster fishing and crabbing are more than jobs, they’re vital cultural links. Lingering concerns about oil contamination threaten the activities at the community’s heart. (Photo: Jeff Young)

YOUNG: About eight months after the storm I was reporting from Plaquemines Parish, that’s where the Mississippi Delta branches into a bird’s foot and the land melts into the Gulf. Towns like Venice, Port Sulphur and Empire were just beginning to rebuild. I got curious about the small gravel roads that climbed up and over the levee, and the people that lived beyond that protective wall of earth.

So I picked one at random and drove it to the end, through the treeless marsh to a boat landing. That’s where I met Raymond Reyes and Nicholas Bartholomew, both fishermen in their 60s and both still struggling to come back from Katrina.

REYES: This is grand bayou village they call this… all this around here is called Grand Bayou Village and we all live right here and uh, the only thing we do is trawl and catch oysters all we do all our lives, that’s all we do, you know. And we’re just hoping to get back in business.

BARTHOLEMEW: We didn’t make a lot of money but we made a livin,’ we made a livin’ that was the main thing. But Katrina came and took that away from us. And we can’t get no help from nobody.

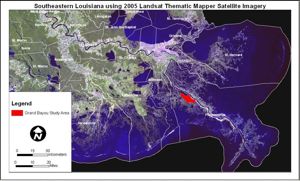

The Grand Bayou is represented in red in this map of Southern Louisiana. (University of New Orleans)

YOUNG: Mr. Bartholomew said he couldn’t get assistance to fix his heavily damaged boat. Mr. Reyes said most of the village’s 25 or so homes, on stilts above the water at the bayou’s edge, were still uninhabitable. Some people were living in FEMA trailers in nearby towns. They showed me where Mr. Reyes and some others were living: in the 10 by 12 foot cabins of their shrimp trawlers.

BARTHOLOMEW: They lived on there for six months during the storm. Six months they lived on this boat right here.

[WALKING INTO CABIN]

REYES: There was 4 or 5 of them.

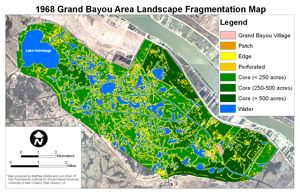

Grand Bayou in 1968. Water is represented in blue and land is green. (University of New Orleans)

BARTHOLOMEW: Four or five people living in this little cabin.

REYES: They had 2 bunks, the stove, a little bathroom, you know and fit five persons in here. Kinda crowded, you know.

[WALKING OUT OF CABIN, ALONG GANGPLANK ]

YOUNG: What do you think is going to happen here, is this community going to come back the way it was?

REYES: Oh I’m gonna tell you right now, them people here is die hard. They gonna come back. They gonna come back. Unless they find a better place to live they will come back but I don’t think they will find a better place than this, this is like heaven, you know. Everybody was together, it was a big old family, you know. So I don’t believe they gonna split up.

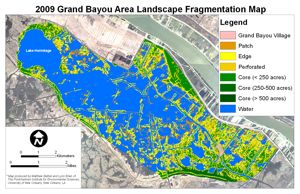

Grand Bayou in 2009. More than half the area is now covered with water. (University of New Orleans)

BARTHOLOMEW : It was like a big old family When they cook everybody eat. How many dinners they give in this here? People come and eat. Grand Bayou, the home of the free.

REYES: Don’t know when, but they will be back.

BARTHOLOMEW: Oh yeah definitely…they will be back. I might not see it cause I’m getting older but this place will bloom again.

YOUNG: That was Spring 2006. This summer I went back to that same boat landing to see if people had come back to Grand Bayou.

[BOAT ARRIVING AT LANDING]

YOUNG I recognized Raymond Reyes as soon as his boat pulled up. His hair might be a bit whiter now, but it’s a full head of hair that shines against his deeply tanned skin. He looks fit, and happy. In December he finally moved into his house after living on his trawler, the Uncle Norris, a lot longer than he had planned.

REYES: Four and a half years!

YOUNG: Wow!

REYES: Last time you saw us we was living on the uncle Norris, little bitty boat. Now we got a house, so we’re living in a house. We got everything we need, we got hot water, yeah we doing good. We happy. Way better than the boat! (laughs) Yep.

YOUNG: But shortly after Mr. Reyes got into a house he was out of work. The BP oil spill closed the shrimp and oyster beds. He’s been getting by with oil clean-up work.

REYES : I got my son here helping me working on the oil spill. So we doing good we happy now. Not what we want to do. But like I say we doing something we paying the bills. So, we’ll be alright, you know? We survived Katrina, this, we can survive this too. Like I said only thing to do is put our trust in the good lord and things will be fine.

YOUNG: Why was it so important to you to stay in Grand Bayou Village?

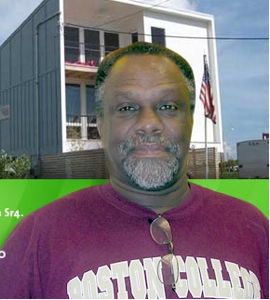

“We survived Katrina, we can survive this, too.” After 4 years living on his shrimp trawler, Raymond Reyes, 66, is finally back in a house. But the spill put him out of work. (Photo: Jeff Young)

REYES: Well I want to tell you something. My mom married my stepdad when I was two yrs old and I been here ever since. I’m 66 yrs old why would I change now? That’s my livelihood so I’m gonna stay here. Yep that’s all. We got the burial grounds right here, so why move? Everything is here you know? Everything we need is here- our livelihood is here and all my family is here so where can I go, you know?

YOUNG: Catching up with Mr. Reyes years after we first met, I finally started to understand his strong sense of place and community. made me realize just how special his community is. Grand Bayou is a native American village. They are the Atakapa-Ishak people. So when Mr. Reyes talks about the burial grounds- that’s not just a cemetery. It’s a burial mound. History for Grand Bayou stretches back centuries before the first western settlers arrived. And, for all that time, they have made a living from the bayou. Now there’s deep concern about whether that way-of-life can continue.

[BOAT STARTS]

YOUNG: Rosina Philippe meets me at the landing in a small boat. It’s the only way to get around in Grand Bayou Village, where Main Street is a waterway. Ms. Philippe is 54, she has a long black braid and a steady gaze. She’s Grand Bayou’s unofficial historian.

PHILIPPE: We’re in Grand Bayou right now. You can see some of the remnants of the homes.

YOUNG: Of the people who were displaced by Katrina, how many do you think have come back?

A house one Grand Bayou resident hopes to return to some day. Only 9 of 23 families have come back after Katrina. (Photo: Jeff Young)

PHILIPPE: Well, we only have managed to return nine families.

YOUNG: Out of how many that were here?

PHILIPPE: Out of 23

YOUNG: Nine out of 23.

PHILIPPE: Well, we’re still in recovery from Katrina with rebuilding the homes, returning people back to the village to reclaim their lives- it’s an ongoing process. And it seems that other things crop up to kind of bleed our energies and our attentions from that focus, like with the oil disaster in the Gulf.

YOUNG The bayou’s waters still teem with life, shrimp crabs and oysters.

PHILIPPE: Porpoises in the water!

YOUNG: Oh my gosh, there they are! Coming right at us.

PHILIPPE: Yes. They’re wonderful to watch.

YOUNG: When BP’s oil hit the nearby bay, it struck at the very core of Grand Bayou’s existence.

PHILIPPE: It’s one of the most serious impacts we’ve ever felt. We’ve been here in this region more than 1,000 years. We’re the first peoples in this region. We’ve had losses from natural hazards, some from human-induced impacts. But even at the worst of times in these other occurrences we were still able to feed ourselves, and to provide, at least, food for our families. Now that’s threatened. And we do not know the long-term impacts.

YOUNG: The backdrop to all this is that the land itself is disappearing. South Louisiana is eroding at an alarming rate—as much as a football field is lost every 40 minutes. It started with river levees cutting off the sediment-rich floodwaters that nourished the marsh. Natural subsidence of the soft delta soil accelerated. Then came the oil wells and miles of canals for pipelines and platforms that carved up the delicate wetlands.

PHILIPPE: They came in and manipulated nature and they took and took and took. They cut canals and allowed the saltwater to intrude, a lot of the trees and vegetation died off. You know we’ve seen all these things take place. And now that we know better, I do believe there are things that can be done. And there are some things being done, but it’s not aggressive enough. Because, you know, it’s almost you’re like giving a critical patient an aspirin when they have cancer.

[BOAT ENGINE FADES]

YOUNG: People from Grand Bayou are now helping coastal researchers better understand land loss in a partnership between science and traditional ecological knowledge.

BETHEL: Oh, it’s invaluable. I don’t know that we could have done this study without having that knowledge.

YOUNG: That’s Matt Bethel, at the University of New Orleans. Bethel’s project pairs up satellite and aerial images of the shrinking coast with the intimate knowledge that fishermen and trappers have of the local land.

BETHEL: They were able to fill in the blanks between image shots that we had and tell us, okay, what was going on here, what did you observe here while you were out fishing and trapping that would explain some of the things that we were seeing in the satellite images.

YOUNG: That level of detail could help guide restoration projects to save the marsh.

Bethel clicks through decades of aerial images of Grand Bayou. Narrow channels of oil pipeline canals widen into rivers over time. Small ponds become lakes and acres of land turn to open water. At this rate of loss, Grand Bayou could soon be swallowed by the Gulf of Mexico.

BETHEL: There are maps produced that show that this whole area will be gone by 2050. And, the Grand Bayou people have seen those maps…they know that. If they all move off and they scatter, they’ll tell you, they’re not the same people. They’re tied to the land, and without that, they don’t have anything.

[BOAT ENGINE]

YOUNG: The coastal erosion has national implications, as does the oil spill, as did Katrina. But the tiny community of Grand Bayou is on the frontline of all three; a microcosm of major challenges. Rosina Philippe says her people have learned to live in a changing environment. But now the changes come so quickly, it’s harder to adapt.

PHILIPPE: I’ve been asked this… well why do you put up with this? Why do you stay, why fight to return? I can only say that if you were here in Grand Bayou and you could know the peace and see what I see and you know, this is our place in the universe. This is where the creator set us down. In spite of all the impacts that have come at us both natural and human induced, we’re still here. This is where we belong.

[ENGINE DIES, OAR STIRS WATER]

YOUNG: She kills the engine and we sit and listen a moment to the marsh .

PHILIPPE: We have our sacred places still. We are a mounds culture, mounds builders. And they’re suffering from erosion and that’s the original site, you know, of our people here. Many, many, many generations.

YOUNG: What would it mean if burial mounds went underwater?

“This is our place in the universe.” Rosina Philippe can see her ancestors’ burial mounds from her kitchen window. But rising seas and sinking land could put them under water in a generation. (Photo: Jeff Young)

PHILIPPE: They have. There used to be twelve. We have three now. It’s a loss, I can’t even tell you the loss. I can’t even translate that into words, and to see the erosion and see the trees falling over because land has eroded away. I just wonder about the future generations – they’ll just have our history and our story, but they won’t have the place.

YOUNG: See photos of Grand Bayou and its people, and maps showing coastal land-loss at our website LOE dot org.

[MUSIC: Buckwheat Zydeco “Tee Nah Nah” from Zydeco Party (Rounder Records 2001)]

CURWOOD: In a moment, we’ll look at what the people of the Gulf Coast want their government to do to rebuild their lives and livelihood. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[MUSIC: Donald Harrison: “Indian Blues” from Indian Blues (Candid Records 1992)]

Related links:

- About the Atakapa-ishak

- Pontchartrain Institute for Environmental Sciences at U. of New Orleans

The Bayou Ballot Box

(Photo: Mitra Taj)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth – I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood, down in the bayous of Louisiana.

[SOUND OF CICADAS SINGING IN TREES, DOGS BARKING IN BACKGROUND]

CURWOOD: When you go down the Bayous from New Orleans towards the ocean, you head into Louisiana’s third congressional district. And this year as candidates vie for an open congressional seat in Bayou country, we asked some active citizens how they want their elected officials to serve them in these perilous times of storms, oil spills and coastal erosion. We begin at Ellender Farm, a 3200-acre sugar plantation.

[ELLENDER OUT BACK: You can hear the wind in the cane. See how tall it is? That’s ready to harvest. Hey, Yvonne!]

CURWOOD: Theresa-Marie Ellender walks past her neighbor’s house and toward fields of tall, green stalks of sugar cane. Her husband’s family has owned and farmed much of this land for more than 150 years. Her house faces Highway-55 in the small town of Bourg in a parish called Terrebonne, which is Cajun French for “good earth” or “good land.”

Theresa Marie Ellender is campaigning for a conservative candidate in the GOP primary. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

ELLENDER: They used take…to have donkeys and a barge and they would pull the barge. Down at Montague they used to have a sugar mill. And they would load up the barge full of sugarcane and follow the bayou all the way down to the mill. And so that’s why the road is here and follows the bayou and why it’s so close to the bayou.

CURWOOD: Passing cars and trucks would find it hard to miss the big sign planted in front of her house: Jeff Landry, Conservative for Congress. Jeff Landry is a lawyer and part owner of an environmental services company, and one of three men running for Congress in this district’s Republican primary. Here’s Mr. Landry announcing his run…

LANDRY: Our country is in peril because our government is out of control, caused by a President and Congress where free spending and liberal vales reign, where the size of our government is growing as fast as our coast is eroding.

[ESPRESSO MACHINE NOISES]

CURWOOD: Inside the Ellender home, Teresa Marie switches on an espresso machine and pours frothy steamed milk into a glass.

[SOUND OF POURING]

ELLENDER: For you.

STEVE: Soy latte.

ELLENDER: Soy latte. That’s one cup, you wanna take a sip there, real quick there, cause it’s gonna…. Now if you want some sweetener, let me know.

Ellender's sugar cane farm. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[SIPPPING SOUNDS]

STEVE: Right here in the bayou, huh?

ELLENDER: [Laughs.] Right here in the BAYOU!

CURWOOD: And right here in the bayou, canals dredged by oil and gas companies have helped destroy the wetlands, leaving coastal residents more vulnerable to storms and flooding. And, how important is this to Theresa Marie Ellender?

ELLENDER: Coastal erosions are definitely a real thing. I mean, it’s really happening. Big ‘ol chunks of land are just falling off. That’s real important around here, because there’s not going to be here—

CURWOOD: (laughs) And, right here, I mean, really you’re in the sea. This house, this is elevated, you don’t have any kind of basement, I’m sure because….

ELLENDER: Oh, there’s no basement. But we’re high…. We are 8 feet above sea level. How bout that? Yeah, we’re pretty high, we’re kinda like the high point in the parish.

STEVE: But still… it must feel kind of tough being here. How many storms in how many years and now this oil spill?

ELLENDER: 5 years and 7 storms, it was pretty intense. And then…the oil spill, I mean, it’s been bad… it’s not clean and everything, but it’s not to the degree that it’s made out to be. I think that there’s a whole lot of environmentalist exaggeration going on. You know, if you start looking at some of the warm water catastrophes in oil, things clear up pretty quickly and pretty nicely.

CURWOOD: So, yeah, lets talk about this. We’ve had all these storms, this oil spill, what should- what could or can’t government do about this?

ELLENDER: The federal government needs just to kind of pull their hands off and allow the state just handle it. But people have got to learn to stop turning to the government, we’ve got to become self-reliant. And, with the moratorium, that thing has got to be completely overturned. Completely. Because, it’s hindering them, the oil companies, from doing their job. And I feel like I’m singing the praises of the oil companies, but you’ve got to understand…oil is the blood that runs through the whole country and without it there’s nothing. Makeup, oil. Everything, oil. Wish I had some on my property. (laughs).

CURWOOD: So, um. End of the day, how do you feel our democracy is working?

ELLENDER: Well, we have a Republic instead of a Democracy. And I don’t really feel like our republic is really working well. I don’t feel like the people in Washington are representing the people here. We need to get people of integrity, like Jeff Landry… up there.

CURWOOD: All three Republicans, and the lone Democrat, oppose President Obama’s moratorium on deep water drilling, but there’s still plenty to fight about. Republican oilfield manager Kristian Magar is polling in the single digits and is unlikely to survive past the first primary round on August 28th, which is open only to Republicans. It may take a runoff to settle the Republican contest and it’s already become a showdown about who’s the true conservative - Jeff Landry or former Louisiana House speaker and retired National Guard major general Hunt Downer.

[WALKING INTO DOWNER HEADQUARTERS, DOOR OPENS, BELL RINGS]

CURWOOD: Hunt Downers’s volunteers call themselves “Hunt’s Army,” and they work out of a bare-bones office building in downtown Houma, Louisiana.

[VOLUNTEERS MAKING NOISES, COPY MACHINE NOISES]

Republican candidate Major General Hunt Downer. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Huntington “Hunt” Downer served, not just in the first Gulf War, but also in Katrina and Rita, as the number two man in charge of the Louisiana National Guard’s rescue and rebuilding efforts, riding out Katrina at National Guard headquarters.

DOWNER: I actually saw my own vehicle float, go underwater, and then it just went from there, did search and rescue, spent the first week on a roof of the building, as we operated out of there for search and rescue in the new Orleans area, so I’m going up there as a general, to give them a little direction with some common sense and some practical knowledge learned at the hands of a hurricane, at the hands of a storm, having seeing coastal erosion…

CURWOOD: So you go to Capitol Hill—what would you change about the federal government that takes care of places like Louisiana that have a high flood danger?

DOWNER: The first thing I would do is reorganize the corps of engineers, get the bureaucrats out of it, get the bureaucracy out of it, and do like we do in the military…like you should… you make a decision and move forward. We don’t have time to study and study and study, I’m just tired of that. We need help down here. Look at the millions and billions we spent to save the Florida everglades, and that’s inland, we’re on the coast—save us! It’s a culture, it’s a way of life, it’s our oil and gas industry.

A volunteer at work at Hunt Downer headquarters in Houma, Louisiana. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Hunt Downer was a Democrat until about seven years ago when he switched parties. And like him, Democratic volunteer Carol Leblanc thinks the rest of the country needs to recognize southern Louisiana’s contributions, and vulnerabilities.

LEBLANC: What should government do? Money. Number one, foremost. If we get the proper resources, if we can get the proper monies down here we can build the proper levees, because we don’t have the proper levees, most places don’t. And if you don’t have the proper levees it’s just hopeless you know—what happened in New Orleans, you know. And I read of some of these senators and reps that don’t vote for funds for us and I’m like, I don’t understand that.

CURWOOD: This year Carol Leblanc’s fighting for Ravi Sangisetty, the sole Democratic candidate for the third district seat. Mr. Sangisetty also gets a helping hand from Craig Stewart, an attorney based in Houma, who has a different economic concern.

Houma attorney Craig Stewart supports Ravi Sangisetty. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

STEWART: Specifically Louisiana has been known or has historically been a community where the big companies would come in and pretty much have their way. So they’d come in waving the flag of we’ll bring 200, 3,000 jobs and then everyone would roll out the red carpet, forget the regulations, we’ll give you tax incentives to bring those jobs into our communities and we’ll turn our head when we have the environmental concerns. But you know with Ravi in there and a couple other individuals, maybe we can have a stronger voice at the table, a voice of reason that can put the checks and balances in place.

[RESTAURANT NOISES]

CURWOOD: Ravi Sangisetty is campaigning tonight at a local restaurant in the small town of Larose.

SANGISETTY: Thanks for coming out, how you doing, nice to meet you…

CURWOOD: About a dozen people get settled in plastic chairs at long tables, eyeing the candidate and the buffet of jambalaya spread out in the corner of the room.

[PEOPLE TALKING, LAUGHING]

CURWOOD: Ravi Sangisetty’s a Princeton-educated attorney who wrote his senior thesis on how to save a local estuary. At just 27, he’s a lot younger than people he stands up to address. He also stands out for another reason here in Cajun country—his parents were born in India.

Democrat Ravi Sangisetty introduces himself to potential voters in Larose, Louisiana. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

SANGISETTY: Hey ya’ll thank you so much for coming, My name is Ravi Sangisetty. I was raised right here in south Louisiana, and as I’m sure I’ll challenged on that fact I’ll be sure to carry my birth certificate with me as I hit the trail (laughter).

We’re well acquainted with federal government dysfunction here in south Louisiana. Well it’s time for south Louisiana to take a stand! We produce energy, seafood, agricultural goods like sugar cane, and we build ships for the rest of the country. And we do this despite the fact that we’re washing away, that we’re losing our coast, that we lack adequate hurricane protection.

Carol Leblanc, born and raised in the bayou, helps connect her candidate, Democrat Ravi Sangisetty with the community and potential voters. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: Ravi Sangisetti is there to talk—and listen. And before he can secure votes, he has to win some credibility.

Man: Why should we believe you?! But that’s the attitude I have though… I know what you talking about, in other words what you saying is you need to get in there to change it—but will you change it?

SANGISETTY: Absolutely

MAN: We been cheated so much, so many lies, and everything…the way things going right now, in other words I’m frustrated and I had enough of it, now I feel sorry for my grandkids, I feel sorry for my kids, I been a fisherman for almost all my life, it’s a way of life and everything else, that’s how I was raised with my daddy. We lost it—our freedom is gone.

CURWOOD: In November Ravi Sangisetty will face the Republican who eventually gets more than 51 percent of the GOP vote. Perhaps then the Bayou country electorate will make it clear what the majority wants in addition to integrity: less government or more federal money. Our piece on Louisiana politics was produced by Mitra Taj.

UPDATE: After the votes in the Republican Primary of August 28 were counted Hunt Downer received 7,570 votes or 36.1%, Jeff Landry 10,396 votes or 49.6%, and Kristian Magar 2,987 votes or 14.3 % out of a total of 20,953 ballots tallied. Jeff Landry and Hunt Downer, the top two vote getters ,will face off in another voting round on Oct 2, the same day as municipal elections in the area and voter turnout is expected to be higher. Had Mr. Landy received just 81 more votes on August 28, he would have had an outright majority and won the Republican nomination for Louisiana’s third district Congressional seat.

Related links:

- Hunt Downer's website

- Click here to learn more about Jeff Landry.

- Christian Magar's website.

- Ravi Sangisetty's website

Long Term Gulf Restoration

President Obama speaking about clean up efforts on the Gulf Coast with Ray Mabus, Secretary of the Navy and Obama’s choice to head up Gulf restoration efforts. (U.S. Navy)

YOUNG: The man in charge of the federal government’s plan for restoring the Gulf brings a varied resume to the job. Ray Mabus is the 75th Secretary of the Navy. He was governor of Mississippi in the late 80s, and was President Clinton’s ambassador to Saudi Arabia. I spoke with Secretary Mabus in his Pentagon office. He told me what he’s been hearing in his town hall meetings on Gulf restoration.

MABUS: When the cameras go off, once the well was capped, not to forget the Gulf. Second, that whatever plans come forward, ought to come from the Gulf, up. People of the Gulf, the people who live there, raise their families there, ought to be the ones that are the primary drivers. Third, a lot of work has already been done on how to restore the Gulf environmentally, for example. Not to try to re-invent the wheel but simply use these sorts of things going forward. Finally, that the Gulf is so important to the rest of the country that while this was a Gulf crisis; it’s a national issue. This is America’s Gulf and this should be a national response to this.

Living on Earth host Jeff Young interviews Ray Mabus at the Pentagon. (U.S. Navy)

YOUNG: And how big a piece of the puzzle is the restoration of the land itself- saving the wetlands?

MABUS: Ecosystem restoration has got to be our top priority. Louisiana loses a football field of land every 38 minutes. Some of the issues in the Gulf, environmentally, have been well known for a long time now- the erosion of wetland, the erosion of barrier islands. And, the fact that, as wetlands erode, as barrier islands erode, you make hurricane protection less viable. Those things have been there before - the oil spill made them worse…clearly made them worse. So I think that while you are restoring the damage that the oil spill has done, it may give you an opportunity to work on some of these longer-term things, because you’re going to be there anyway.

YOUNG: Do you see BP paying for this?

President Obama recently appointed Ray Mabus the task of coming up with a long-term Gulf Coast restoration plan. (U.S. Department of Defense)

MABUS: Well I think BP is clearly the responsible party for the oil spill. For things that have been there for a long time you may look to different sources.

YOUNG: You know, when I have been to the Gulf recently, I hear great deal of frustration and some skepticism from people about claims that help is on the way. Did you pick up on that at all? And, if so, what do you…how do you overcome that?

MABUS: The main assurance I have is that the President of the United States from the Oval office promised the people of the Gulf and the people of America, and I think that that is the ultimate guarantor.

YOUNG: Of course, it’s not the first time a president has pledged to help the gulf coast:

BUSH: We will do what it takes. We will stay as long as it takes to help citizens rebuild their communities and their lives.

YOUNG: That was president George W. Bush in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Forty years earlier, President Lyndon Johnson made this pledge after Hurricane Betsy.

President Lyndon B. Johnson looks at the aftermath of Hurricane Betsy in New Orleans, 1965. (oldneworleans.com)

JOHNSON: The national government will be at Louisiana's side to help it every step of the way in every way that we can.

YOUNG: Why should Gulf residents think this time is going to be different?

MABUS: Well, for one thing, the response has been… it’s been a huge federal response to the spill itself. Look at what’s been done already. But, second is…judge by results. If you want to build trust be trustworthy. I hope that the report I give to the president and the actions that are taken in the wake of that will help build that trust and particularly the actions day in day out month in month year in year out will continue to build that trust over time.

YOUNG: So, if you expect people in the Gulf to judge you by results, what should they be looking for…what would that first result look like?

MABUS: That we had listened to the people of the Gulf, that we don’t try and reinvent the wheel, that it is an ongoing process. That we’re not going to forget the gulf, that we’re not going to leave now that the well is capped. This report and this commitment is ongoing.

YOUNG: Secretary Ray Mabus thank you for your time.

MABUS: Thank you.

Related links:

- Gulf Restoration recommendations from environmental and social justice groups

- The White House gulf recovery effort

- Click here to hear an extended interview with Secretary Mabus

Where Are They Now: Bob Rue

Bob Rue scrawled these messages on the front of his Oriental Rug shop on St Charles Ave. Rue never left New Orleans during the storm but fears many of his fellow citizens will never return. (Photo: Jeff Young)

YOUNG: Well, time now to catch up with someone we interviewed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina.

RUE: My name’s Bob Rue, I’m an old fart. I’ve been here since 1964. I was brought here as an indentured servant and I’ve been here ever since.

Bob Rue’s sign is now housed at the Newseum in Washington, DC. (Newseum/Maria Bryk)

YOUNG: Bob Rue never left New Orleans, not even when the storm hit. He stayed to guard his business, Sarouk Shop, Oriental Rugs on St Charles Avenue. When I first spoke with him in 2005, he was enjoying a brief moment of fame. Newspapers carried pictures of a sign Rue had scrawled on his boarded-up windows: a warning to would be looters.

RUE: It said 'Don't even try, I'm sleepin' inside with a big dog, an ugly woman, two shotguns, and a claw hammer.'

YOUNG: I won't ask who the ugly woman is.

RUE: Well, we have some discretion here.

[STREET CAR RUMBLES BY]

YOUNG: Well, today the streetcars and tourists are back on St Charles Avenue. And Rue tells me his famous plywood sign has found a new home.

RUE: Well, now it belongs to the state of Louisiana. They’re gonna have the fifth anniversary at the Presbytere. And my sign is going to be in the entry.

YOUNG: So it’s kind of like an artifact?

RUE: Yeah. You know I went down there, and I had all five pieces of plywood I found in the street and painted up as the signs on plywood in the bottom of my truck I was just kind of throwing them on the ground and these museum people were out there with little white gloves picking them up and fondling them, you know. Right now one of ‘em’s on display in Washington DC at something called the ‘News Museum’.

YOUNG: Ah, the Newseum.

RUE: The Newseum, yeah. And the girl called me for weeks trying to get my picture of me with Tim Russert standing out front. But, I can’t find it, it’s lost in the ménage. I got married since then and moved everything I don’t know where all my pictures are from the storm.

YOUNG: Wait…you got married?

RUE: Yeah. There’s still women in New Orleans with no taste. She’s wonderful - she’s half French, half Sicilian. Her family grew up here in New Orleans, and she’s an incredible cook, pretty damn funny, and overlooks a lot of flaws.

YOUNG: Well you seem to be doing well.

RUE: Uh…there’s no business. The banks aren’t loaning any money for mortgages so nobody’s buying houses so they’re not decorating so they’re not buying rugs. I’m having to depend on rug cleaning and repair, which is...thank god for dogs, because they pee everywhere. We got these little black voodoo candles in the shape of a dog. When things are slow, we light ‘em up and all over town dogs go crazy start biting rugs pissing everywhere – basically we’re making it on rug cleaning.

Bob Rue scrawled these messages on the front of his Oriental Rug shop on St Charles Ave. Rue never left New Orleans during the storm but fears many of his fellow citizens will never return. (Photo: Jeff Young)

[MUSIC: Dr. John “Scald Dog/I Can’t Go On Medley” from Goin’ Back to New Orleans (Warner Bros 1992)]

YOUNG: And sure enough, in walked a customer with a pet-stained rug. See pictures of Bob Rue’s famous signs at our website LOE dot ORG.

CURWOOD: In just a minute – the Gospel jazz trumpeter who says Hurricane Katrina baptized the city of New Orleans- stay with us at Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Dr. John: “Fess Up” from Goin’ Back To New Orleans (Warner Bros. 1992)]

Related link:

The museum exhibit at the Louisiana State Museum, in the Presbytere

Still Seeking Environmental Justice in New Orleans

Environmental justice activist Beverly Wright has worked to clean up contaminated soil and improve levee protection since Hurricane Katrina. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

YOUNG: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood in New Orleans.

[STREET AMBIENCE]

CURWOOD: Five years after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, areas of downtown New Orleans and some neighborhoods look pretty good and function well. But not everywhere. I stopped by the house of environmental justice expert and Dillard University Professor Beverly Wright. She came back to rebuild her home in the black middle class neighborhood of New Orleans east.

CURWOOD: What happened in this house?

WRIGHT: Well, this house is very interesting it had 6-8 feet of water in it- completely destroyed. There was an alligator in the pool in the back. And, the whole house had to be gutted.

CURWOOD: It’s beautiful now. I mean I couldn’t tell walking in there that anything had ever happened.

WRIGHT: No, you really cant. That’s the beauty of this whole thing. There’s no reason for us not to come back because it can be rebuilt.

CURWOOD: So here it is 5 years on from Katrina, how are things here?

WRIGHT: Well, if I had to grade the city, I would say we’re about at a 5 on a scale from 1 to 10. But there are some areas of the city that are at a 9. So, really, how you’re doing depends on who you are and where you live. And it’s not necessarily connected to income. It is connected to skin color. And African Americans, who made up 80% of the people affected by Katrina, are not doing as well as white people who make up 80% of the persons who have come back home.

In New Orleans east for example, we have one supermarket. I went to the supermarket yesterday. I could get no lettuce, you know, no fruit…all the fruit gone. It was just amazing. 70,000 people, one supermarket in New Orleans east. That’s it. And I have to tell you, I’ve not been a big McDonald’s fan, but after Katrina, if it weren’t for McDonald’s we wouldn’t have had anything to eat. It was like people just forgot about us.

CURWOOD: So, how would you explain what happened to New Orleans in environmental justice terms.

WRIGHT: Well, the environmental injustice occurs in a number of ways. The fact that, first of all, when you look at the federal level they never addressed soil contamination that exists all over the city.

CURWOOD: What are the contaminants that are in the soil here?

WRIGHT: We have extremely high arsenic levels, and PCBs, cause where we live we use a lot of pesticides; we have a lot of pests. From rat poisoning, to pesticides for roaches and mosquitoes, you already have all of that, right, and then you add to that the big mixture that came in all the water from all over, even from the bottom of Lake Pontchartrain, then you add to that human feces and everything from the sewage treatment plants. That water was extremely filthy. And very dangerous. And then it settled. There was a light dust that covered everything when we came back home. And what is just amazing about this is that it was an easy fix.

And the army corps of engineers had, in the first few weeks after the storm, come up with a remedy. They were literally going to scrape dirt off the whole city. New Orleans would have been the cleanest urban area in the country. Well, some politicians decided that if they did they they’d never get the city back…it would have the reputation for being a superfund site. My thing was, if you’re not going to protect the citizens at least tell them what they need to do to protect themselves.

Professor Wright in her home in New Orleans East, which was flooded by 11 feet of water during Hurricane Katrina. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

So we started the Safeway Back Home campaign, where people remediated their own properties and planted new grass, and so on. And the block that we worked on, there was one lady who didn’t have much grass. So she decided when she saw the mounds of dirt that she didn’t want to be bothered with that. So she went outside sweeping up her patio, she broke out with a rash from her head to her toe.

CURWOOD: So, how far has the self-remediation program gone?

WRIGHT: I would say not far enough. We’ve been concerned because New Orleans has a history of backyard gardening. So when I was a kid everybody had a garden. If you didn’t have one, you ended up with one because the vines would start to grow across the fence and so you’d end up with tomatoes and what we call meliton, which is a Japanese plum. You’d have okra just showing up in your yard. So I grew up with things growing in my yard that we ate. And, so it’s an old tradition and it’s been difficult for us to try to get the word out to people, do not eat the vegetables that are growing in your yard unless you’ve had your yard tested or use raised gardens.

CURWOOD: So, what are the other environmental justice issues that come out of the Katrina experience?

WRIGHT: Well, levy protection for one, was one the biggest ones. And we’re still dealing with that. I mean, even after all the money that was put in place, wealthy and white got better protection than the rest of us. So I went to the army corps of engineers meetings to find out, what is this process and how is this happening? And this is what we were told: that rich white folks were in the plan for better protection some 15, 20 years ago. And so their projects were already in the hopper. So when things get fast-tracked, what’s in the hopper comes out first. So they ended up ahead of us again. So it was a lesson for us, you know, try and understand how does this work?

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about the oil disaster and the environmental justice aspects of that. Even as far north from the Gulf as here in New Orleans.

WRIGHT: You know it’s amazing to me that whenever they talk about fishermen and they don’t show black fisherman, it’s a HUGE crew. And think about it now. If we were not allowed to go to school, we had to make a living some way. If it wasn’t on a plantation, what would black people do to earn a living in Louisiana? They’d become fishermen and oystermen and stuff. And they’re 10,000 deep in some of the parishes, in Plaquemines Parrish and so on. But they were invisible.

I think that certain cultures that have made Louisiana distinct could disappear. When certain lifestyles disappear, then a certain part of that culture that has been maintained can also disappear. So we’re about—we could lose our difference. My hope is for the future with young people. I would say that young people are not NEARLY as racist as what we used to be. And I think they see a completely different world and I’m so happy that that is the case.

CURWOOD: Professor Beverly Wright directs the Deep South Center on environmental justice at Dillard University in New Orleans.

[MUSIC: Eddie Bo: Mardi Gras In The Boileroom” from New Orleans Solo Piano (Night Train International 2006)]

Related links:

- Learn more about the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice.

- Click here to read a Washington Post on the uneven recovery.

- Click here to listen to an extended interview with Beverly Wright

Green Living in New Orleans

Robert Lynn Green Sr. in front of his new house in the Lower 9th Ward of New Orleans. (www.makeitrightnola.org)

[CRUNCHING WALKING SOUNDS]

YOUNG: A few weeks after Katrina I walked through the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans. Dried mud cracked underfoot amid the wreckage of homes. One of those homes belonged to Robert Green Sr. Now, thanks to his tenacity and the generosity of a Hollywood star; Mr. Green has a new house on high stilts in the lower nine. He shows me the high ceilings.

GREENE: “HELLOOOoo… an echo. (Laughs). There’s an echo in the house, and a lot of people actually think that this is a two-storey house. But where we are standing in this house was underwater during Katrina. Even though we elevated off the ground.

Construction of Robert Greene’s new environmentally friendly and storm safe house. (www.makeitrightnola.org)

YOUNG: We are way high above the street here.

GREENE: yeah, we were under water. So that loft is actually an escape feature cause when we were here during Katrina and the house lifted off its foundations and floated two blocks up the street. We were actually stuck in the attic about this high. And we thought we were safe, and the water was going over our heads.

About 3,000 houses were washed away on that day. And on that day we lost our house, we lost our mother Joyce Green who was 73 years old. We lost my granddaughter Shenaye Green, who was 3 years old, but we also lost all of our neighbors. We lost Mr. Gaskin, we lost Ms. Broomfield, we lost the Legers, we lost the Fletchers. We lost so many families that day after a barge bust a hole in the levee wall and made this a spill way; it washed away this neighborhood.

YOUNG: This is part of actor Brad Pitt’s “Make it Right” project—a tract of affordable, storm-proof green houses. Mr. Green watched his being built while he toughed it out in a FEMA trailer.

GREENE: I lived in that FEMA trailer for three years.

YOUNG: But now you’re back and you’re in an amazing home.

GREENE: Uh-huh. And the idea of building these houses, to build a house that’s better, that’s stronger, that’s environmentally friendly, that uses as many recycled materials that uses materials that have low VOC levels. We also have solar panels so that we can get away from the use of fossil fuels. And it’s actually a LEED Platinum certified house.

YOUNG: Do you think houses like this are the future of the 9th ward? Or is this out of reach for so many people?

GREENE: I think it’s the future of the world to be perfectly honest, because one of the things that we have to do, we have to build better, build wiser, and build stronger. If every house built were built on that same premise, then in the long run we’re going to benefit environmentally, we won’t use as much fossil fuels, we won’t contaminate our own environment that we have to live in. So if we look at the benefits, they out-weigh the costs.

YOUNG: How is it to live in? I mean it’s really striking to look at, but does it feel like a home?

Robert Greene’s new house in New Orleans. (www.makeitrightnola.org)

GREENE: Oh it’s a joy and a pleasure to be back in the same location of the house that was destroyed in Hurricane Katrina. It actually allowed us to bring life back to this neighborhood. So it's basically a wonderful house to live in.

YOUNG: This is one house that’s truly a Green home.

Related link:

Visit the Make it Right project

Trumpeting New Orleans' Rebirth

Hack Bartholomew was the Minister of Music at the Neville Brothers' family church in New Orleans. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[STREET NOISE AND STREET PERFORMANCE]

CURWOOD: In New Orleans a little bit of French goes a long ways—like beignet for donut. And where else to get these amazingly tasty morsels—but Café Dumonde at the edge of the French Quarter. Depending on the morning, along with your beignets you may get to hear street musician Hack Bartholomew.

[TRUMPET MUSIC]

CURWOOD: A trumpeter and vocalist who’s played with the greats, including the Neville Brothers, George Benson and Keith Richards, Hack Bartholomew left New York after 14 years to come back home to New Orleans and jazz gospel. Hack performs five days a week at Café DuMonde. When he’s not busy producing recordings, he’s the trumpeter for the Greater Saint Stephen Full Gospel Baptist Church.

[MUSIC: “Lifting Jesus Up In New Orleans” from Lifting Jesus Up In New Orleans (Hack Bartholomew 2003)]

[CICADAS BUZZING]

Hack Bartholomew (Photo: Steve Curwood)

CURWOOD: As the cicadas buzzed on a hot August afternoon, Hack Bartholomew sat down on his front porch to tell me his story of how he survived Hurricane Katrina.

BARTHOLOMEW: I would say I got a revelation from God to just get out. So my wife and I and our kids, grandchildren, we all just left, fortunately my wife had a cousin in Houston and we were able to stay over at her house. When the storm hit we was sitting in Houston we were watching everything on television and praying and hoping that everything would be alright for the city. But it was not. But fortunately where we lived up here up here in Carrolton, the Carrolton black pearl section is a pretty high point of the city. As you can see my home is just like I left it. When I got back a lot of my neighbors had wind damage. The neighbor over here, his roof blew off, the neighbor over here, door and windows blew out. Just about everybody had wind damage. Except us.

[MUSIC: “Angels Keep Watching Over Me” From Lifting Up Jesus (Hack Bartholomew 2003)]

BARTHOLOMEW: But our church in New Orleans east on Reed Road, it was totally flooded. Fourteen feet of water in the church. But our uptown location was spared. And I think we were one of the first few congregations that were back after the flood.

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

One of Hack Bartholomew's regular gig's is playing for tourists at Cafe Du Monde. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

BARTHOLOMEW: When we were in Houston we looked at the television. We saw the whole city underwater, just about, 80 percent of the city under water, and I said, you know what, God is baptizing New Orleans. You know when you baptize a person you submerge them down. It signifies one being buried and when you bring ‘em up, they are rising up again, to that new man who is coming up, that’s rising from the water.

…New Orleans was really going off the deep end there with all kinds of things going on, with the crime and corruption, and what have you. And it kinda made people think. It made the politicians think, it made the people of New Orleans think about doing something positive, about having integrity, about being accountable, to your brothers and sisters who you see every day. That storm, at the time it was happening, it didn’t look too good. But in the end, it was very good because we had all of the love and compassion of people, the help of the people who came down to help us, all black white, Chinese, Asians, Indians, you name it, I think they might have had some purple people here, but I aint seen ‘em though. Everybody was like, putting their shoulders together and doing this thing, helping this city to come back.

Hack performs for Living on Earth in his backyard. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[MUSIC: “Down By The Riverside” from Lifting Jesus Up In New Orleans (Hack Bartholomew 2003)]

CURWOOD: you like play the tune down by the riverside, what is the war you’re talking about that we shouldn’t study anymore?

BARTHOLOMEW: The war that I’m talking about is not Iraq or Afghanistan or Vietnam or any of that. The war I’m talking about is the battlefield of your mind. The people that makes us want to hurt another person, take from them is that your mind, your heart, your soul.

[MUSIC: DOWN BY THE RIVERSIDE]

CURWOOD: Hack Bartholomew: Lifting Jesus up, down in New Orleans.

YOUNG: There’s more of our coverage of Hurricane Katrina and its 5th anniversary at our website, loe-dot-org.

Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation from the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios. I'm Jeff Young.

CURWOOD: And from New Orleans. I'm Steve Curwood, thanks for listening.

Related link:

Click here to learn more about Hack Bartholomew

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield pays its farmers not to use artificial growth hormones on their cows. Details at Stonyfield dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners. The Ford Foundation, The Town Creek Foundation, The Oak Foundation—supporting coverage of climate change and marine issues. The Bill and Melinda Gates foundation, dedicated to the idea that all people deserve the chance at a healthy and productive life. Information at Gates foundation dot org. And Pax World Mutual Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at Pax world dot com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI – Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth