August 3, 2012

Air Date: August 3, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math

View the page for this story

Humanity can survive if we can keep the climate from warming less than two degrees Celsius, and emit less than 565 Gigatons of carbon dioxide. The problem: energy companies have 2,795 Gigatons of carbon left to burn. Environmentalist and writer Bill McKibben talks about his recent Rolling Stone article, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math” with host Steve Curwood. (12:40)

Protecting Marine Biodiversity in Brazil

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

The Cagarras Islands archipelago near Rio de Janeiro, Brazil received federal protection in 2010. As Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports, scientists are already seeing successes for marine biodiversity conservation there. (06:20)

Marine Reserves

View the page for this story

Divers flock to spots like the Great Barrier Reef, the Northern Hawaiian Islands, and the Phoenix Islands for their incredible biodiversity and picturesque reefs. Recently, national governments have recognized the importance of preserving these areas by implementing marine protection areas. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Phil Dearden, geography professor at the University of Victoria, about the state of the seas. (06:05)

The Place Where You Live

/ Chaitali BanerjeeView the page for this story

In collaboration with Orion Magazine, Living on Earth continues our feature “The Place Where You Live.” This week, Chaitali Banerjee follows a bird squawk on a bike and hike trail in Niskayuna, New York where she often takes refuge. (03:50)

BirdNote® Gulls of Summer

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

In August, a variety of species of gulls travel to the Pacific and Atlantic coasts after nesting elsewhere. Mary McCann has more. (02:00)

Greening the Playing Field

View the page for this story

More Americans follow sports than science, and that enthusiasm could be put to good use. So says Allen Hershkowitz from the Natural Resources Defense Council. He tells host Steve Curwood how sports teams can encourage the public to become better environmental stewards. (06:20)

The Fastest Car

/ Lisa RaffenspergerView the page for this story

A team in England is taking speed to new levels. No, we’re not talking about Olympic athletes, but instead, the creators of the Bloodhound Supersonic Car. As IEEE Spectrum Radio’s Lisa Raffensperger reports, the Bloodhound is designed to go a thousand miles an hour, making it the fastest car on earth. (08:45)

Earth Ear- Bottlenose Dolphin

View the page for this story

The sounds of Bottlenose Dolphins in Milford Sound, New Zealand. (01:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Bill McKibben, Philip Dearden, Allen Hershkowitz

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Chaitali Banerjee, Mary McCann, Lisa Raffensperger

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. This summer the country has roasted in the worst drought in two generations, heightening concerns about climate disruption.

MCKIBBEN: Nobody can look at our continent this summer with its record wildfires, its record heat waves and not have some deep foreboding about what is happening on this earth.

CURWOOD: Writer Bill McKibben lays out what he calls "terrifying new math" related to our addiction to fossil fuels.

Also – a new engineering feat – but the world's fastest car will hardly save gas, it goes a thousand miles an hour!

GREEN: There’s a tremendous sense of awe about enormous power and enormous quantities of almost anything. Particularly with vehicles for speed.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick Around!

[THEME]

PRI ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math

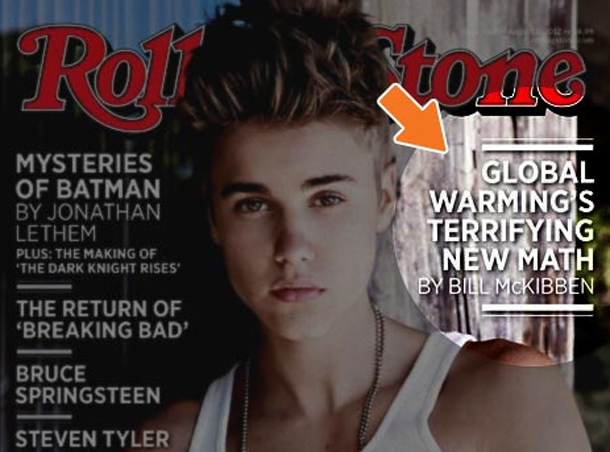

The August 2nd issue of Rolling Stone

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. First there was an early hot spring, and then a broiling summer and now about half of America is sizzling in the grip of drought. Add a rash of tornadoes, early tropical storms, and widespread ice melt, and many observers point to climate disruption.

Bill McKibben is one of the most outspoken American voices on the question of climate. His non-profit group, 350.org, organized the largest global protest in history. Now he's taking his message to the pages of Rolling Stone Magazine with his treatise, “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.” Bill McKibben, welcome!

MCKIBBEN: Hello Steve - how are you?

CURWOOD: I am well! Although your article says that clearly the planet will not be well if we continue on this path.

MCKIBBEN: Yeah, I’m afraid that even to me, these numbers came as something of a shock. They really shouldn’t have, because of course I’ve been doing this for a long time- I wrote my first book about this almost a quarter century ago, “The End of Nature.”

CURWOOD: We can’t be that old that I was in touch with you back in 1989 when…

MCKIBBEN: (Laughs). I can remember - 1989.

CURWOOD: When the “End of Nature” came out and we were getting this program started. You thought that that one book would do it, huh?

MCKIBBEN: Well, I was pretty sure that it would be all it would take. But it turns out that’s not quite how change happens, and in fact, what’s happened over the quarter century is really that we’ve lost more than we’ve won. As you know, the amount of carbon keeps increasing that we pour into the atmosphere and the temperature keeps going up.

What’s new and it’s thanks to some financial analysts and accountant-types in the UK is that we now have a better understanding why – unless we change things very dramatically – this is all but inevitable. And that’s what the math in this piece is about.

CURWOOD: And, by the way, a little bit of math on your own article in Rolling Stone -as we’re speaking, the magazine actually wasn’t on the stand, just online - you’re approaching 100,000 likes, just online.

MCKIBBEN: I feel very well liked, yes. It’s interesting because it’s a kind of long piece, 6,000 words, and it has a lot of numbers in it, and yet people seem very eager to read it and to share it. I think Rolling Stone said it may have gotten the most views of anything they’ve done in a long time.

I think there’s a lot of people looking around at drought, the wildfire, and the heat waves, and are really starting to come to terms with the fact that we’re in trouble and trying to figure out exactly the contours of that trouble.

McKibben in Times Square leading the International Day of Climate Action. (FlickrCC/Mat McDermott)

CURWOOD: Alright, so now as they say, let’s now do the numbers here. The first number that you have in your article here is two degrees Celsius.

MCKIBBEN: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Why is that important?

MCKIBBEN: Well, it’s important mostly because it’s the one thing that world has agreed on, about climate change. All of our dysfunctional governments that haven’t gotten anything done, have nonetheless, time after time, put their names to pieces of paper saying ‘we can’t let the temperature rise more than two degrees Celsius,’ about 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. Now frankly, that number is too high. We’ve raised the temperature about one degree Celsius, and we’ve already melted 40 percent of the sea ice in the summer Arctic. If we were at all sensible, we would do what we could to stop right here.

CURWOOD: And yet, you say, it’s not enough.

MCKIBBEN: Well, here’s the thing. Were we to hope to stay below two degrees, to have a reasonable chance of keeping the world’s temperature below two degrees, the scientists tell us that we can only emit about 565 gigatons more carbon. We’re emitting about 30 gigatons a year, and we’re increasing that by about three percent a year – that’s how much coal and gas and gas we’re burning – so that gives us 16 or 17 years, which is bad news in and of itself.

But the real bad news, and the number that was the really scary one for me in this piece is the amount of carbon that the fossil fuel companies and countries that kind of operate like fossil fuel companies – think Venezuela or Kuwait – the amount that they already have on their books, in their reserves - that’s about 2,800 gigatons, or about five times more than even the most conservative scientists or governments says that we could safely burn.

CURWOOD: So, lets look at the money that’s involved. The researchers you cite here say that there’s five times as much oil, coal and gas, on the books of various energy companies, as climate scientists think is safe to burn. So that we have to keep four out of five of those barrels of oil and tons of coal underground.

MCKIBBEN: And at current market value, that means right off of something like 20 trillion dollars.

CURWOOD: That’s bigger than the United States deficit!

MCKIBBEN: It’s larger, probably, than the bubble that surrounded housing.

CURWOOD: How do you persuade corporations to give up 20 trillion dollars in assets?

MCKIBBEN: Well, it’s possible you can’t. But, the only way you can is - since we’re never going to have as much money as they do - is to build a movement. To work in different currencies: you know, passion and spirit and creativity, and sometimes, at least for a while, it works!

Last year at this time everybody told us that it was absolutely inevitable that the Keystone XL Pipeline would be built, and built this year. We organized the largest civil disobedience action in 30 years in this country, and at least for now, it’s not been built. I’m not guaranteeing victory. And, in fact, if you were forcing me to bet, you know, an honest man - I’d be forced to bet that we’re not going to win. But the stakes are high. The stakes are really nothing less than just about everything.

CURWOOD: Well, Bill, you always keep things a little bit light for us and at one point you have an analogy between carbon and beer in this article.

MCKIBBEN: I’m glad you picked up on that because it’s, well, it’s a subject dear to my heart! We know that the two degrees is about like knowing what the legal drinking limit is. You can blow a 0.8 and you’re off to jail. And we know about how much you can drink and have some hope of staying below that. If you’re a guy my size and if you drink six beers slowly over the course of the evening, you’ll be pretty close to it, but you’ll be right around there. That’s the two degrees and the 565 gigatons. Here’s the problem: the fossil fuel industry has three twelve packs on the table, ready to pour. And that’s the trouble that we’re in. We’re about to go way-way-way over the limit. And nobody, no president, no politburo, no anybody is effectively saying: time to slow down.

CURWOOD: Now, I’m thinking of environmental activists, pretty much as a whole, and I think rather understandably, they really haven’t wanted to take on the fossil fuel industry.

Bill McKibben. (FlickrCC/The Aspen Institute)

MCKIBBEN: No, because it’s awful powerful! And why would you? I mean we’ve kept hoping that they would somehow magically become our allies. And occasionally there were sort of signs that might happen. I remember being with you Steve, maybe 15 years ago, in an MIT conference room listening to the people from BP explain that they were now going to be Beyond Petroleum.

They changed their logo, and they put some solar panels on a few of their gas stations, but they never really made any significant investment in renewable energy, they just kept looking for hydrocarbons, and you know, a couple of years ago, they said: forget even those token investments, we’re going back to our core business, and their core business turned out to be destroying the Gulf of Mexico.

And so the upshot of it is, and what we at 350.org are going to do - is try to take on that political power of those fossil fuel industries. We’re going to go right at them trying to kind of foment a divestment movement that looks a little bit like - say - the anti-apartheid movement only a generation ago.

CURWOOD: Alright. To continue with the South Africa analogy for a moment - you have a system of apartheid, you have a long resistance, a war, and then seemingly things changed. Why?

MCKIBBEN: Well, the two situations are not identical, obviously. The best…the most hopeful part of the analogy for us is that that financial pressure paid off. In this case, of course, it’s hard because all of us are beneficiaries of the fossil fuel system, as well as, you know, its potential victims.

On the other hand, we have as our sad recruiting sergeant, our unfortunate ally, we have Mother Nature, who’s making it abundantly clear now just what’s going on. Nobody can look at our continent, this summer with its record wildfires, its record heat-waves, its incredible, deep drought, its 76 percent of the farms in America now in drought areas, and not have some deep foreboding about what is happening on this earth.

CURWOOD: In South Africa, much of the argument was a moral one. What’s the moral argument you make here?

MCKIBBEN: I think that the climate change argument has often been put as a kind of technical argument, but in fact, at base, it’s a moral argument. What we’re dealing with is the out-of-control greed of a few companies. We know what the future should look like, and we know how to do it. There was one day last month when Germany, one of the few countries on earth that’s actually tried hard to do this stuff - one day when it generated more than half of its power from solar panels within its borders. Now, more than half its electricity from the sun - Munich’s north of Montreal. What does that indicate? That indicates that it’s not technology that limits us, it’s political will. And, one of the ways that we’ll generate that political will is make it clear just what the greed of this industry is doing to the one planet we’ve got.

CURWOOD: So what exactly are you calling for in terms of divestiture of fossil fuels?

MCKIBBEN: I think that college kids need to be sitting down with their boards of trustees and saying, ‘Really? You really want to pay for our education with investments that guarantee we’ll have no planet on which to carry out that education?’

I think that people need to sit down with state and municipal pension funds and say, ‘Really? You’re going to pay for people’s retirement funds with investments that ensure there’s not a planet for them to retire on?’ We’re going to try and put on pressure like that. By itself, it won’t be enough to carry the day, but it’s the kind of thing that sometimes can add up and add up fast. Change people’s understanding of where we are. Introduce a new wild card into this rigged game.

CURWOOD: So, you end your article saying: ‘We’ve met the enemy and it is Shell.’

MCKIBBEN: I was reflecting on the fact that we’ve been told very often that this is a personal problem, a lack of willingness of people to change. And yes, we need to take shorter showers and drive smaller cars and many of us have worked hard on those things.

The real problem is the amount of money that these fossil fuel companies pour into our political system to make sure that their special breaks stay intact, that they alone among industries continue to be able to pour their waste out for free. And that’s why, when you get down to it in any kind of mathematical analysis, with apologies to Walt Kelly, we’ve met the enemy and they is Shell, and Conoco, and Exxon, and all the rest.

CURWOOD: But, Bill, you could say that we’re the enemy too, because we have all of our money in 401Ks, the pension funds, various endowments invested in those companies that you just mentioned - they make a very fine return these days.

MCKIBBEN: And let's hope that we can bring ourselves to part at least with some of that easy return, because the long term return on that investment may not be hell exactly, but it’s got a pretty similar temperature.

CURWOOD: Bill McKibben’s latest article in Rolling Stone is entitled “Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math.” Thanks Bill for taking the time with me today.

MCKIBBEN: Take care Steve!

Related links:

- Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math

- Bill McKibben’s 350.org

[MUSIC: War “The World Is A Ghetto” from The World Is A Ghetto (Far Out Productions 1972).]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – how protected areas of the oceans can help fishermen - stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Jazz Soul 7: “It’s All Right” from Impressions Of Curtis Mayfield (BFM Jazz 2012).]

Protecting Marine Biodiversity in Brazil

Ipanema, in the foreground, is just a 3-mile boat ride from the Cagarras Islands. (Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Brazil is renowned for biodiversity. There’s the Amazon rainforest of course, but the Atlantic Ocean offshore from Brazil is also teeming with diverse life. Now, that marine life is getting more attention from conservation organizations and the Brazilian government. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb visited a recently protected marine ecosystem in the south of Brazil and has our story.

[BOAT ENGINE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: From a motor boat driving parallel to the white sands of Ipanema beach you can see rainforest draped mountains and the iconic statue of Christ with his arms spread wide above the famously beautiful city of Rio de Janeiro.

Christo el Redentor stands over Rio de Janeiro. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

Just three miles south of Ipanema are the picturesque Cagarras Islands, where tourists and locals come to scuba dive and fish. Fernando Moraes is a marine biologist with the national museum of Brazil. He stands on the bow of a motorboat anchored off one of the islands.

MORAES: This is very common this kind of fishing, recreational fishing spending the day here fishing and drinking beer of course. You can see by the shapes of the men.

[MUSIC FROM BOATS]

BASCOMB: Samba music carries across the water as pot-bellied men in tiny Speedos stand on their boats and cast fishing lines into the choppy sea. When the sun gets too hot, people jump in for a swim; if they’re lucky they might just spot a dolphin.

[PEOPLE TALKING BETWEEN BOATS]

BASCOMB: These islands and the water around them are full of rare endemic species, found nowhere else on earth. The ocean here is especially rich in tropical fish, and sponges only recently described by science. Above the water the islands attract birds that come here to nest and breed. Flocks of birds fill the sky - brown boobies with bright blue legs - black and white frigate birds with bulbous red throats that they puff out to attract a mate.

Male frigate birds inflate their red throats to attract a mate. (Photo: US Fish and Wildlife Service)

MORAES: The ones with the big red throat, they are the males of the frigate birds and we are in the middle of the nesting season. Most of them with the red color very brilliant. And that’s a signal for the female that they are the strong ones. They have been successful in catching fish, that they will be able to feed their young.

BASCOMB: The sky is just thick with birds do you have any idea how many there are out here?

MORAES: We have an estimate about five thousand frigate birds nesting on these islands and more; about two thousand brown boobies.

BASCOMB: Those numbers make the Cagarras Islands archipelago the second largest nesting area in Brazil for boobies and frigate birds. In 2010 the six islands became Brazil’s first federally protected natural marine monument. Divers and fishermen can still come and enjoy the water but they are not allowed to catch anything within 30 feet of the islands.

People are not allowed land on the islands anymore either, leaving nesting birds in peace.

Before the islands were protected, fishermen camped here and often left trash behind. Volunteers took more than 175 pounds of garbage from one island in a single clean up day.

[CAR STREET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The biggest concern for the Cagarras islands is pollution from Rio de Janeiro. It’s just three miles away and is home to more than six million people. It’s also one of the largest industrial ports in the country. Fabiana Bicudu is in charge of the Cagarras Island project for the government of Brazil.

BICUDU: We are very near a big city so we have impacts like organic waste. Organic waste that comes from the city, and also the big vessels waiting to enter the city and we have the residual oils in the water because of these activities.

BASCOMB: There’s another potential threat from oil: drilling. On the horizon are a handful of deepwater oil platforms. Petro Bras is the largest oil company in Brazil and also the sole sponsor of this island conservation project. It paid for the nesting bird count and all of the scientific research related to the project. Petro Bras invests in conservation programs like this to offset some of their environmental impacts elsewhere.

Birds fill the sky over the Cagarras Islands. ( (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[SOUND OF CAR DRIVING BY]

BASCOMB: In the two years since the islands gained federal protection Fabiana Bicudu is already counting successes. In the past fishermen used bombs and poison to force fish to the surface, but no longer.

BICUDU: We don’t see these kinds of activities any more on the islands. It is better because divers and visitors feel safety to be there so we have bad users coming out and good users come in.

BASCOMB: And the government wants to encourage good users and sustainability. In the future, it plans to increase the 30 feet no fishing zone but marine biologist Fernando Moraes says even 30 feet is significant.

MORAES: That by itself is very important because you have a place for the fish to reproduce, and birthrates and all that, and a place where nature is allowed to develop itself without any kind of pressure. It’s very important.

BASCOMB: The shallow rocky margins of the islands are nurseries for marine life. The government has been working with local fishermen to educate them about the importance of this area for breeding fish. The message seems to be paying off. Manasi is 23 years old and has been fishing here since he was 12.

MANASI (Speaking Portuguese): My father fished here, my grandfather, my great grandfather, many generations. I think this is a very important area for the fish to reproduce. So if we protect it now, there will be more fish for us to fish in the future.

BASCOMB: That’s the hope, though of course they don’t yet know if it will work. But for fishermen, tourists, and environmentalists, Rio’s first federally protected marine monument is a promising first step. For Living on Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

[SOUND OF WAVES]

CURWOOD: Our story from Brazil was made possible by a fellowship from Earth Journalism Network. For pictures of the islands, sail on over to our website LOE dot org.

Related link:

Earth Journalism Network

Marine Reserves

Reef fish in Hawaii’s Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. (US Fish and Wildlife Service)

CURWOOD: Now there’s a strange juxtaposition between protected islands and the offshore oilrigs that Bobby saw off the coast of Rio in Brazil. Around the globe, multi-national companies are increasingly drilling into the depths, and as the deepwater disaster in the Gulf of Mexico showed, those wells can threaten the environment.

Yet at the same time, the amount of ocean protected by national governments is also increasing. Philip Dearden studies these Marine Protected Areas. He’s Professor and Chair of the Department of Geography at the University of Victoria in British Colombia, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Professor.

DEARDEN: It's a pleasure to be here!

CURWOOD: So tell me about Marine Protected Areas, your area of research - how do they work?

DEARDEN: Well, essentially the same way as National Parks work in the terrestrial environment. We say these areas are set aside to protect environmental processes for the species therein and they take top priority. So, we don’t kill them, we don’t interrupt the processes. So in so doing, we increase the diversity and increase their numbers and we keep healthy ecosystems alive.

CURWOOD: Now you can put a fence around a National Park, but fish can go anywhere. What’s the advantage of having a special marine protected area?

DEARDEN: The advantage is for sedentary species are very clear. For fish that do a lot of movement, then you have to look at - do these fish need protection, and if so, in what particular areas. For example, you might set aside an MPA for them in an area where they would do their spawning aggregation, or something like that.

CURWOOD: So, Marine Protected Areas - especially good to protect the breeding areas for certain kinds of fish.

DEARDEN: That’s right.

CURWOOD: So, Bobby Bascomb did a story about some protected islands off of Brazil, and the limits only go a few feet from shore - I’m wondering - just how big do you have to have a Marine Protected Area in order for it to be effective as a conservation device?

DEARDEN: It’s just like the terrestrial environment. In general, larger areas are much more ecologically effective, so the larger the area, the better that it is. As well, you have a lot of edge effect on these marine protected areas. If you have people fishing around the outside and you’ve only got 30 feet protected, fish don’t have to swim very far to become unprotected.

So, 30 feet would be the smallest that I’ve ever heard of. Generally the science suggests that at least 30 percent of every marine habitat should be in a no-take zone, should be protected.

CURWOOD: So tell me, what’s your favorite Marine Protected Area around the planet?

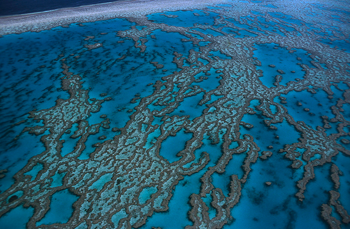

Australia’s Great Barrier Reef (WWF Deutschland)

DEARDEN: Whoa! That’s a tough one. We spend a lot of time working in Thailand, and I’ve been undertaking studies there for almost 30 years. I still love the diving off the reefs there - there’s still wonderful coral to be seen, and quite a big abundance of fish. When I go to areas such as the Great Barrier Reef in Australia I’m also awed by just the scale of them and the efficiency of the protection in those kinds of areas.

CURWOOD: And how effective do you think that the Marine Protected Areas have been there off Thailand, have been off the Great Barrier Reef? How effective is this as a conservation measures?

DEARDEN: Well, the research is very strong that when you do establish a protected area in the ocean that the numbers of fish increases, the diversity increases, the size class of the fish increase. And along with that there are other components of the ecosystem that also increase in their overall abundance. And so they’ve been proven to be extremely effective, and some of the best results on that come again on the Great Barrier Reef and from monitoring that has been undertaken there.

CURWOOD: Professor Dearden, I understand that part of your work focuses on incentive-based conservation, please tell me a bit about that.

DEARDEN: Well, the way that most protected areas are protected is by national legislation and policy. And then we pay park guards to come and enforce those regulations and policies. But the optimal situation is when local people in fact, see it in their own best interest to protect the conservation values.

In terms of fishing, the research clearly shows that over 10-15 years time, generally fishing returns improve because you have a spill-over effect from the MPA into the local fishing areas, so there will be more fish to catch.

Other ones relate to transformation of the economy. We’ve particularly worked with how can you derive more income from ecotourism? And how can those incomes go to local villages and help replace more extractive fishing activities?

A Blue fin Trevally in Hawaii’s Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. (US Fish and Wildlife Service)

CURWOOD: So, if I were to look at the oceans as a whole, what portion of it, what percentage of the oceans are marine areas around the world that are considered to be in protected zones?

DEARDEN: Well, now it's just over one percent of the ocean is considered to be protected. Again, what is protected, not all of those necessarily forbid fishing, for example. So in Canada, every Marine Protected Area is supposed to have a no-take zone. Under the Parks Canada Marine Protected Areas – there is only one established at the moment – and that no-take zone was three percent of the area.

So, only three percent of the entire protected area was actually protected from fishing. And, within that three percent, it still allowed aboriginal fishing. So when you get down to it - there are no areas that are set aside that are totally non-extractive.

CURWOOD: Dr. Phillip Dearden is professor and Chair of the Department of Geography at the University of Victoria, in British Columbia, thank you so much.

DEARDEN: OK, it's been a pleasure, thank you.

Related links:

- Dr. Phil Dearden is a professor and chair of the Department of Geography at the University of Victoria.

- Dr. Dearden works for the Marine Protected Areas Research Group, which is based on Victoria, Canada and conducts research pertaining to marine protected areas.

[MUSIC: Antonio Carlos Jobim “tema Jazz” from Tide (A&M Records 1970).]

CURWOOD: This week we have another installment of the Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” For more than a decade, Orion has invited readers to put their memories of home on a map and submit essays on their website. And now, we’re giving them a voice.

[MUSIC: The PLACE WHERE YOU LIVE THEME]

The Place Where You Live

CURWOOD: The special place that you care about - where you go to be close to nature doesn’t have to be exotic - it doesn’t have to be spectacular - it just has to speak to you.

BANERJEE: I’m Chaitali Banerjee, I’m from Nisayuna, New York. It’s about 18 miles from Albany, the capital of New York. I’m a biomedical scientist and a science writer and I also write essays, travel narratives, short poems, and this is a piece that I wrote about a park that I visit often - it is on the banks of the Mohawk River, which is a tributary of the Hudson River. It’s my place to contemplate, to write and I also do a lot of bird watching there. There are several species of birds - common birds, but I do look at them.

[MUSIC: Vitamin Piano Series “Goodbye Blue Sky” from The Piano tribute To Pink Floyd (Vitamin Music 2005).]

BANERJEE: Chasing A Squawk Across the Mohawk River.

Hot, parched, parking lot eases into cool shading oasis beneath maple and cottonwood trees lining the Mohawk/Hudson hike/bike trail. I settle down on a bench as the air fills with swirling wisps of cotton. Squawk, squawk, loud, deep, guttural throaty. I scan the marshes, no suspect.

Distant cattails undulate in gentle breeze; smack at the center of river, an angler’s boat. Redwing blackbird hops among maple leaves, here I see it, here I don’t. Flycatcher dives into carpet of water chestnuts. Squawk, I gaze up and down the river. Grackle keeps its yellow, bright, inquisitive eyes on me. Iridescent feathers now purple, now the deepest blue. Red-tailed hawk misses a chipmunk.

The Mohawk-Hudson Hike/Bike Trail in Niskayuna, New York. (Photo: Chaitali Banerjee)

Squawk, I walk, eyes peeled to the river, marshland shrubs. Riverbank resplendent with vibrant rose-purple spikes of Purple Loosestrife. Squawk, squawk. A large grey-blue bird rises from the duckweed. Rises its way across the marsh - I am spellbound. As I savor the leisurely, graceful, grey and black flight, the elegant curve of the neck, bill so yellow, sharp and strong.

Slender, long legs. It lands on driftwood, composes itself then starts stalking with deliberation. Stilt-like legs cover stretches of marshland in a blink of an eye. Yellow gimlet eyes intense and focused - the beak dives in and out. My binoculars tremble as I watch a primal struggle unfold. Squawk, Squawk, the Great Blue eron. I stand out at river’s edge…mesmerized.

CURWOOD: Chaitali Banerjee lives in Niskayuna, New York. Tell us about “The Place Where You Live.” You can find out about our collaboration with Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay by visiting our website LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Let us know about “The Place Where You Live.” To post your essay on the Orion magazine website, click here.

- Listen to other Place Where You Live Essays

[MUSIC: Vitamin Piano Series “Goodbye Blue Sky” from The Piano tribute To Pink Floyd (Vitamin Music 2005).]

CURWOOD: Coming up – how our passion for sports is being harnessed to green America. Keep listening to Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Breckinridge Capital Advisors, applying a sustainable approach to fixed income investing, www.breckinridge.com, the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and Gilman Ordway, for conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUT AWAY MUSIC: Koul Funk: “Hot Funk” from Cocktail Hour (Amathus Music 2008).]

BirdNote® Gulls of Summer

Laughing Gull (Photo: © Tom Grey)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood

[BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: You might think that a gull is a gull is a gull - but, as BirdNote®’s Mary McCann reports - it isn’t exactly so.

[CALLS OF GLACOUS-WINGED GULLS]

MCCANN: If you visit the beach as summer wanes, you may notice that gulls with different appearances are showing up. Gull-watching is pretty tame along the coasts most of the summer. Many gull species retreat well north to nest, a few others inland. Along the Atlantic, it’s mostly nesting Herring and Laughing Gulls that stick around through summer. On the Pacific coast, it’s Glaucous-winged and Western.

But by late August, the picture begins to change. Bonaparte’s Gulls begin arriving along both coasts and at the Great Lakes. These small, sleek, black-headed birds begin flocking south in August.

[CALLS OF A FLOCK OF BONAPARTE’S GULLS]

MCCANN: Handsome, pale gray Ring-billed Gulls also return to both coasts in late summer, most having nested inland.

[CALL OF A RING-BILLED GULL]

MCCANN: Both species winter along the coasts:

[CALL OF A RING-BILLED GULL]

MCCANN: And along the Pacific, one very distinctive gull has come just for a summer visit – the Heermann’s Gull.

[CALL OF THE HEERMANN’S GULL]

MCCANN: Watch for a gull with a very dark back, a powder-white head, and – unmistakably – a blood-red beak. Heermann’s Gulls nest along the northwest coast of Mexico, disperse northward for a few months each summer, then return south. I'm Mary McCann

CURWOOD: That's BirdNote®’s Mary McCann. To see some gull-iful photos of some of the gulls mentioned in this BirdNote®, flock over to our website LOE dot org.

Related links:

- Calls of the gulls provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Glaucous-winged recorded by A.A. Allen, & Bonaparte’s by G.A. Keller & by W.W.H. Gunn; call of Ring-billed Gull by L. Macaulay.

- Heermann’s Gulls recorded by Martyn Stewart, Naturesound.org.

- Ambient track recorded by Kessler Productions.

- BirdNote®

[MUSIC: Flock Of Seagulls “I ran (So Far Away) from The Very Best Of Flock Of Seagulls” (Sony Music 2008).]

Greening the Playing Field

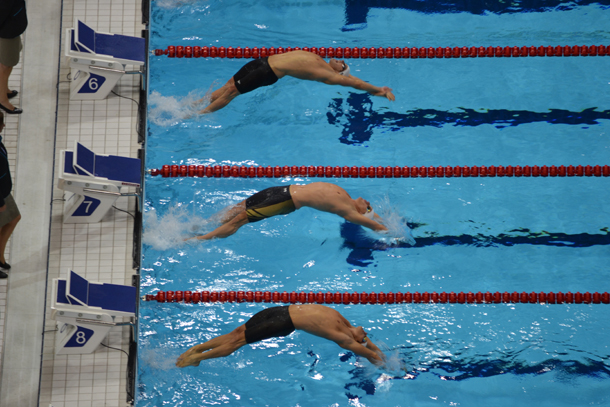

Mens 400 m backstroke event at the London Olympics. (Photo: Government Olympic Communications)

CURWOOD: Now you might have noticed that the Olympic games are currently underway in London. And of course, as ever the Games spark grumbles, heartbreak, and triumph - and debate about the role of sport in national and international life. The London games are selling themselves not only as a way to revitalize a run-down part of the city, but also the greenest Olympics, with plenty of venues designed to be recycled.

But Allen Hershkowitz argues that sports can have a huge influence on environmental attitudes - whether or not it’s an Olympic year. He's a senior scientist at the Natural Resources Defense Council, and directs its sports greening project. Mr. Hershkowitz -- welcome to Living on Earth!

HERSHKOWITZ: Thank you, it's a pleasure to be here!

CURWOOD: Now, you point out that sports are enormously influential culturally, say the sports-boycott on apartheid-era South Africa, or, say, Jessie Owens, who was a spectacular success at the 1936 Olympics in Germany - but tell me, do you think they can change environmental attitudes?

HERSHKOWITZ: Well, it’s interesting. Clearly we need a cultural shift in the way we think about environmental stewardship. Congress, our government, is not leading the way on global climate disruption, on biodiversity loss. Based on past cultural shifts, it’s clear that Congress does not always lead the way - gender equality – it was not Congress that led the way on gender equality.

Olympic Rings unveiled at Heathrow ready to welcome visitors to London 2012 (Photo: Government Olympic Communications)

Civil rights- it was not the government that led the way, it was a cultural shift in the United States toward race relations and that forced Congress to act. So what we’re seeing is cultural shifts are led not by the government but by the people. The sports industry is enormously influential. 13 percent of Americans say they pay attention to science - 61 percent say they pay attention to sport.

The sports industry is non-political. So, if there was ever an industry that could confirm for us the non-partisan mainstream nature of environmental stewardship – the need for better environmental stewardship – the sports industry is a great spokesperson for that cause.

CURWOOD: Which sports in particular do you think have the power to get us to change our environmental attitudes?

HERSHKOWITZ: Well, I think all sports can play a role. Obviously major league baseball, NASCAR, the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the Major League Soccer Association, the U.S. Tennis Association, all of these sports leagues and their teams are now using some form of renewable energy - they have some recycling and composting programs.

They’re all looking at energy efficiency. They’re all looking to use renewable energy. They’re all looking for ways to enhance waste management and also fan engagement. The National Hockey League and the National Basketball Association earlier this year ran two public service announcements in one week that was seen by 45 million people, encouraging people to recycle and think about renewable energy and to think about water conservation.

Dodgers Stadium. (Photo: Flickr CC/Kwong Yee Cheng)

CURWOOD: Now, what evidence do you have, Allen, that the green ideas of sports enterprises - and various officials - that their green ideas are rubbing off on sports fans themselves?

HERSHKOWITZ: Well, people don’t go to sporting events thinking about the environment. But when you show up at the U.S. Open Tennis Championships and you see a public service announcement by Billie Jean King and another one by Venus Williams and another one by the Bryant brothers talking about local food, organic food, recycling, using mass transit…do we know that this is having a transformative effect? - I don’t know.

But I tell you, the fact that these businesses, global businesses, with iconic participants, is encouraging people to think about environmentalism can only help us. And remember, outside the family, the most iconic role models are often athletes and entertainers.

CURWOOD: Well, now, a cynic would say: well, but they’re supposed to do that - it’s sort of like the 55 mile-per-hour sign there on the highway, and they’re there but who pays attention?

HERSHKOWITZ: Well, we can be cynical about it, but to me, the fact that sports is embracing environmental causes represents a watershed in the history of the environmental movement. It’s kind of interesting that the modern environmental movement - which started over 40 years ago - had not collaborated with professional sports, until recently.

Given its cultural significance, it’s such an iconic industry, it’s one of the most culturally influential industries in the world - remember companies pay billions of dollars every year to have their brand name affiliated with professional sports. Coca Cola is one of the official sponsors of the Olympics and has been for 80 years. Clearly, they think that messaging affiliation with professional sports is good for branding. If it’s good for branding for Coca Cola, why is it not good for branding for environmental stewardship?

CURWOOD: Allen Hershkowitz, I’ve gotta ask you about the London Olympics - you were over there - how impressed were you, and how green are they compared to what they had hoped for?

The Cleveland Cavaliers versus the Indiana Pacers. (Photo: Flickr CC/zoonabar)

HERSHKOWITZ: The greening initiatives at the London Olympics are extraordinarily broad and diverse. And it ranges not only from reducing carbon emissions - they’re trying to reduce their carbon emissions by 50 percent - they’re trying to ensure that 20 percent of the energy is used from on-site renewable energy sources. They’re looking to reduce waste by 90 percent, they’re looking to provide 100 percent of the spectators with opportunities to arrive by mass transit or bicycling or walking. They have created the largest new park in Europe in 150 years. The housing is designed with sustainability and energy efficiency in mind.

This Olympics, really, I think, has one of the most ambitious environmental agendas of any sporting event in history. Are they achieving it all? Definitely not, but they’re saying that as well. They produced a report that critiques what they have done wrong and documents what they have done right. So, I have to give the London Olympics very high grades for their ambitions and also for their honesty in the way they are evaluating their accomplishments.

CURWOOD: Allen Hershkowitz directs the sports greening program at the Natural Resources Defense Council, thank you so much.

HERSHKOWITZ: Thank you.

[MUSIC: Monty Alexander “Strawberry Hill” from Yard Movement (Island Records 1996).]

The Fastest Car

The Bloodhound SSC was unveiled at the London Motorsport Show recently. (Photo: Lisa Raffensperger)

CURWOOD: The Olympics showcase the power, speed and skill of the world’s most elite athletes. But not too far from this year's main Olympic venue, a team of engineers is building a car that will also highlight power, skill and especially speed. It’s an automobile that will travel a thousand miles an hour. From the IEEE Spectrum Radio special “Fastest on Earth,” Lisa Raffensperger traveled to London to attend the car’s first public appearance.

[SOUND OF CAR REVVING]

RAFFENSPERGER: They rolled up in Porsches, Jaguars, and Ferraris. Middle-aged men wearing loafers and carrying backpacks piled out of cars. Antique roadsters and pristine Bentleys pulled up onto the grass to park. I, on the other hand, made my grand entrance to the London motorsports festival in slightly humbler fashion…

BUS DRIVER: Bus to Goodwood, ladies and gents. Festival of Speed.

RAFFENSPERGER: …on the free shuttle bus. The Festival of Speed, held outside London every year, is a car lover’s dream.

FESTIVAL ANNOUNCERS: Festival of Speed radio on the way in, in association with The Telegraph, you’ll have heard my colleague Chris Druitt talking to some of the great characters from across the pond.”

RAFFENSPERGER: Vintage Indy 500 cars roared by on the racetrack. Slick Formula One racers stood on pedestals under the summer sun. A crowd began settling into the bleachers. One man poured himself hot tea from a thermos.

But the most stunning car on the fairgrounds that day wouldn’t grace the track. It won’t appear in a showroom. Only one man will ever sit behind its wheel. Tucked away in a tent off to the side was a car unlike any that’s ever been built. A car that will go four times as fast as the fastest car you can imagine. A car that will drive faster than the speed of sound.

[RACE CAR NOISE]

RAFFENSPERGER: Just once in history has a car broken the sound barrier. That was in 1997. The car was the Thrust SSC

—for supersonic car—a slender black needle flanked by huge jet engines. It was built by a team of British engineers led by Richard Noble,

and its driver was Royal Air Force pilot Andy Green. In the Nevada desert, Green piloted the car to a land-speed record: 763 miles per hour, breaking the speed of sound.

Andy Green will pilot the Bloodhound Supersonic Car.

(Courtesy of Curventa and Siemens)

[SONIC BOOM]

RAFFENSPERGER: The shockwave knocked frames off the walls of houses dozens of miles away. Now the team is preparing to smash its own record with the

Bloodhound SSC.. The car has been in the works since 2007. And it’s currently being built in a workshop in Bristol. And when it is raced in the desert of South Africa, the Bloodhound will set a new land-speed record of 1,000 miles per hour.

[RACE CAR NOISE]

RAFFENSPERGER: The first thing you notice about the Bloodhound is its size. It’s very, very big. Shaped like a huge dart, it’s nine feet tall and three times as long as a normal car. But then, not much about the Bloodhound is like a normal car.

For starters, there’s the rocket. Engineer Daniel Jubb has designed the world’s most powerful hybrid rocket to propel the car. It’s similar in size to the rocket powering Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo. And the “hybrid” part comes from its two components, Jubb explains.

JUBB: We use a solid fuel grain, which is very similar to the propellant in a solid propellant rocket, but it won’t burn on its own. It can only burn in the presence of a liquid oxidizer, which is stored in a separate tank. That gives you the ability to turn off the flow of oxidizer and shut the system down. So it’s the ideal candidate for use in a land-speed record car, because you have that element of controllability while retaining simplicity.

(Courtesy of Curventa and Siemens)

RAFFENSPERGER: The rocket’s built into the bottom of the car. And above it, just behind the cockpit, is the car’s other propellant: a fighter-jet engine.

JUBB: What we have with Bloodhound is a really quite elegant solution with the jet engine and the rocket. The jet engine is an EJ200, a proven well-established unit, and it’s very controllable. However, the drag from the air intake, and the size of the engine, meant that we wouldn’t get to 1,000 miles an hour simply by using two jet engines. So we need the brute force of the rocket.

RAFFENSPERGER: Though previous land-speed record cars have used rockets or jet engines, Bloodhound is the first to use both. And finally, the car relies on one additional engine—from a Formula One racer. But it doesn’t power the car. It’s needed just to pump the liquid oxidizer into the rocket, at a flow rate fast enough to fill a bathtub in three seconds. Putting all those components into one vehicle was the job of chief engineer Mark Chapman, and it came with its fair share of headaches.

CHAPMAN: The problem is, the lower altitude you go, the thicker the air becomes. Now, low aircraft do fly at twice the speed of sound. The Typhoon we got the engine from, it flies at twice the speed of sound. It cannot do that at the altitude we’re driving the car at. In fact, nothing has gone that speed at the altitude we’re going at. So we have to be very careful at how we get the flow into that engine.

RAFFENSPERGER: Wheels also do weird things at such extreme speeds.

CHAPMAN: So the way the car steers is like a conventional car: it’s got double wishbone front suspension. Andy’s only got a couple degrees of steering lock. So he’s got a rubbish turning circle, but he hopefully doesn’t need to park or anything like that.

Up to about 400 mph, these work like wheels on your car. They steer by sticking to the ground. And as Andy turns, it digs in and turns the car. Above about 400, they start to work like rudders. More and more, the aerodynamics of the wheel are what’s causing it to do the steering.

GREEN: There’s a tremendous sense of awe about enormous power and enormous quantities of almost anything. Particularly with vehicles for speed…

RAFFENSPERGER: Bloodhound pilot Andy Green .

GREEN: …because it is something you can actually observe—it’s very difficult to observe enormous weight, or indeed, enormous power from an engine. But enormous speed you can actually see something moving incredibly quickly and get a sense of what it’s doing.

RAFFENSPERGER: But if you want to feel what it’s like to drive faster than the speed of sound—not just to observe it—here’s the closest I can offer. A video recording takes us back to 1997. Andy Green is settling himself into the cramped cockpit of the Thrust SSC. All you can see out the windshield is desert, with a white line stretching toward the horizon.

Richard Noble heads a team of British engineer who design supersonic cars. (Courtesy of Curventa and Siemens)

UNIDENTIFIED CREW MEMBER: SSC is ready to roll.

RAFFENSPERGER: The car responds slowly to the throttle but then starts picking up speed.

GREEN: By 200 miles an hour, I’ve got full power on, the equivalent of 100,000 horsepower. It’s now accelerating a 10-ton car at over 20 miles an hour per second, so the car is literally going from 200 to 300 in 5 seconds, and to 400 in another 5 seconds, and to 500, and so on.

RAFFENSPERGER: Five hundred, 600. The car is fishtailing. It veers 50 feet from the line you’re driving.

GREEN: Approaching 700 miles an hour, the airflow starts to go supersonic.

RAFFENSPERGER: You enter the “measured mile,” where you will be timed. And the mile is over.

GREEN: The actual measured mile takes four point seven seconds.

RAFFENSPERGER: Immediately you close the throttle, and all your weight plows forward.

GREEN: And that’s a huge physical change for me, from being pinned back in my seat to being thrown forward into the harness.

RAFFENSPERGER: When you’ve slowed enough, you apply the brakes.

GREEN: Then it all starts to happen in slow motion. By the time you get down to 200 miles an hour, it does actually feel so slow you could just get out and walk.

RAFFENSPERGER: And as you come to a stop, just two minutes after setting off, you’re 13 miles from where you started, and you’re the fastest thing that’s ever crossed the earth’s surface.

I’m Lisa Raffensperger.

CURWOOD: Our story on the Bloodhound car is from the I triple E-Spectrum Magazine special, “Fastest on Earth.” The publication received the 2012 National Magazine Award for general excellence.

Related links:

- Bloodhound SSC website

- IEEE Spectrum Radio Special Report “Fastest on Earth”

[MUSIC: Monty Alexander “Strawberry Hill” from Yard Movement (Island records 1996).]

Earth Ear- Bottlenose Dolphin

CURWOOD: And, now, for a dip in the ocean in the company of bottlenose dolphins.

[CLICKING AND POPPING OF BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS]

CURWOOD: Bottlenose dolphins are found in temperate and tropical oceans worldwide. They use a series of clicks for echolocation to find prey and communicate.

[CLICKING AND POPPING OF BOTTLENOSE DOLPHINS]

CURWOOD: This dolphin pod was recorded in Milford Sound, New Zealand by Dr. Oliver Boisseau for the British Library CD: Sounds of the Deep.

[SOUNDS: Sounds Of The Deep: An Exploration Of Life In Our Seas (British Library Sound Archive 2005)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Kurn, and Ike Sriskandarajah, with help from James Curwood, Meghan Miner, Gabriela Romanow and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Annabelle Ford and Annie Sneed. And we wish a fond farewell to intern Christy Perera, congratulations on your new job. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and check out our Facebook page it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science. And Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at just eat organic dot com. Support also comes from you, our listeners, the Go Forward Fund, the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world's most pressing environmental problems, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Gilman Ordway - for coverage of conservation and environmental change, and Pax World Mutual and Exchange-Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision making. On the web at pax world dot com. Pax world, for tomorrow.

PRI ANNOUNCER: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth