August 10, 2012

Air Date: August 10, 2012

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

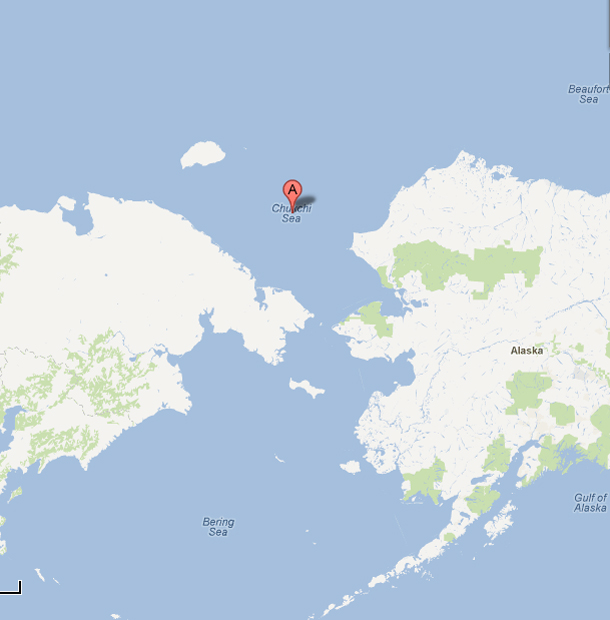

Shell Oil to Drill in Alaska

/ Alex DeMarbanView the page for this story

Shell is ready to start drilling for oil in Alaska’s Chukchi Sea. But environmental concerns have chilled the oil company’s plans. Host Steve Curwood speaks with Alaska Dispatch reporter, Alex DeMarban. (06:15)

Caffeine in Ocean Water

View the page for this story

Researchers are finding caffeine in the ocean and streams of the Pacific Northwest. Portland State University Professor Elise Granek tells host Steve Curwood that scientists are concerned that caffeine can stress aquatic organisms and may be an indicator of additional pollutants in the water. (05:35)

Science Note: Aerographite

/ Annabelle FordView the page for this story

Scientists have developed a new material six times lighter than air that can support something 40,000 times its own weight. Researchers hope to exploit these properties to make light-weight batteries for electric cars. Annabelle Ford reports. (02:00)

Greenland Sharks: The Apex Predator

/ Greg SkomalView the page for this story

Marine biologist Greg Skomal dives deep into the ice cold Arctic waters to find out more about the behavior of Greenland sharks. (05:40)

Speaking of Sharks

/ Ike SriskandarajahView the page for this story

Sharks hold a special, dark corner in the English language. We’ve maligned this apex predator into all sorts of monstrous metaphors, but what do the sharks in water have in common with the sharks in speech? Living on Earth’s Ike Sriskandarajah compares the shark science with the sayings. (06:30)

The Place Where You Live

View the page for this story

This week, the Living on Earth, Orion Magazine collaboration travels to Winfred, South Dakota. Cassie Potter and her horse, Hero, wander through the rugged grasslands. (02:45)

The Seed Underground

View the page for this story

More than ninety percent of U.S. seed varieties available in the early 1900s have disappeared. Janisse Ray trekked through the backyards of gardeners and farmers who are trying to keep the rest of our seeds from going to pot. Host Steve Curwood talks to Janisse Ray, author of the book "The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food." (06:35)

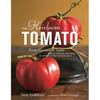

Hand-Me-Down Tomatoes

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

They're beautiful, delicious, all sizes, shapes and colors, and celebrated in the book "The Heirloom Tomato: From Garden to Table." Living on Earth's Helen Palmer visits the garden of author Amy Goldman who not only grows heirloom tomatoes but is passionate about saving their seeds. (10:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Alex DeMarban, Elise Granek, Janisse Ray

REPORTERS: Ari Daniel Shapiro, Ike Sriskandarajah, Helen Palmer

ESSAY: Cassie Potter

NOTE: Annabelle Ford

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International - this is Living on Earth.

[MUSIC UP AND UNDER]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

In the face of protests and regulatory delay, Shell Oil finally sends its drilling ships into the Arctic seas off Alaska. The crew may encounter polar bears and whales, but not the Greenland sharks that scientists are studying in icy waters much further east.

SKOMAL: It's an incredibly eerie world to be in because there's no sound. You're in gin-clear water; it's like being in a giant martini. And there before me is an eight, nine or ten foot Greenland shark.

CURWOOD: Underwater with Greenland sharks. And, in the heat of August, we savor the fruits of summer.

GOLDMAN: There's the Radiator Charlie's Mortgage lifter, there's the Nebraska wedding tomato. . . You know, the heirloom tomato is the people's tomato. It's of, by and for the people.

CURWOOD: Take your pick of these stories, and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around!

[THEME]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation and Stonyfield Farm.

Shell Oil to Drill in Alaska

Researchers on sea ice in the Chukchi Sea. (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

Shell Oil drilling ships are standing by at sea, waiting to sink

exploratory wells into Arctic Alaskan waters. The oil giant bought permits to drill in the Beaufort and Chukchi Sea over five years ago. Since then, Shell has faced hurdle after hurdle with regulators, lawsuits, and a federal moratorium on offshore Arctic drilling after the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

Even with their ships up in the Arctic, Shell is still struggling to get final approval to drill. Alex DeMarban is a reporter for Alaska Dispatch. He says Shell has

already reduced the number of wells they plan to drill this year.

DeMARBAN: Yeah, they cut down on the number because of problems with sea ice. It's lingering longer than usual. It's still, at this point, blocking access to their Beaufort Sea site so they still have not yet even begun to send up ships yet to the Beaufort Sea. And they're still having regulatory issues, as well.

Researchers on sea ice in the Chukchi Sea. (NASA Goddard Space Flight Center)

The two key ones are that they don't have approval for a containment barge which is instrumental in the event of an oil spill to capture the oil and clean it. They need to have that before they can get their permits. And then they also don't have approval yet from Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, or their well permits. They need approval for each well they plan to drill.

CURWOOD: So, there have been a lot of objections from environmental and Alaska native groups over oil exploration in the Beaufort and Chukchi. What do they say?

DeMARBAN: Well, they're worried, of course, largely about a spill. They believe that there's not enough resources up there to respond to it - a spill. We don't even have a deepwater port within hundreds of miles of where Shell will be drilling. There's no Coast Guard station the closest one is 900 miles away. So assistance for Shell in the event of a spill could be a long time coming. So that's the primary concern of environmental groups.

And of course, if there's a spill that could damage... could kill whales, the bowhead whale, as well as other iconic animals such as the polar bear that are already considered to be threatened because of climate change, then that could severely damage the subsistence cultures that exist on Alaska's coast that rely on primarily on the bowhead, but also on Beluga whales.

And when we say that it could destroy their culture, I don't believe that's an overstatement because their entire year is based around the effort to go whaling in the fall and spring.

CURWOOD: How much oil exploration has Shell already happened in these Alaskan waters?

DeMARBAN: There's been about 30 wells drilled and I believe Shell drilled most of them back in the 1980s and 1990s. Apparently they have a pretty good sense that they're sitting on something huge.

CURWOOD: Well, how much oil does Shell expect to get from these sites?

DeMARBAN: Well, from these particular sites, I'm not sure. But the overall Arctic potential oil is considered to be at least 25 billion barrels of oil. It is a lot. But when you consider the vast U.S. consumption, it would go rather quickly if it provided all of that U.S. consumption. . . two years or less is my understanding.

So, they need at least one billion barrels of oil to make it economically feasible...is one rule of thumb. So the economic hurdles are going to be huge because they've still got to figure out how to get the oil to market and, given that there's nothing up there, the cost for that is going to be tremendous.

The Chukchi Sea (A) separates Alaska from Russia north of the Bering Strait.

CURWOOD: What do you mean that there's nothing up there?

DeMARBAN: Well, there's no pipeline. For example, offshore, they're going to have to build pipes under the ocean 70 miles in the case of the Chukchi to bring it onto shore in Alaska. And then they've still got many, many miles across Alaska to carry that pipeline to get to our single conduit that runs across the state.

In order to get the oil to a location from where it can be shipped, hundreds of miles of pipeline would still have to be built in a very complicated region with numerous threats including the underwater ice floes that can slash through pipes, so there's great costs and great concerns going well into the future here.

CURWOOD: Shell Oil is the first comer in this particular round of exploration in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas. What does this mean for the future of oil and natural gas exploration in Arctic waters, in general? Anyone else looking to start drilling?

DeMARBAN: Yeah, I think some of the companies on deck are Conoco Phillips and Stat Oil. They're watching Shell closely to see what's discovered. If there's a large discovery, that's going to compel them to move more quickly. They're hoping to begin development in the next couple of years at some sites in the Beaufort and Chukchi Sea, as well. And, certainly, if Shell finds something huge, there's expected that there'll be a sort of oil rush to the Arctic.

DeMARBAN: Alex DeMarban, you've been following this story of Shell attempting to drill there in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas there in the Arctic. How likely is it, do you think, that Shell will end up putting in these test wells before things freeze up this year?

DeMARBAN: Well, I think that there's a very good chance that they are going to get one done in the Chukchi, and they do have an opportunity to request an extension, so that may happen. There's a very good chance that that may happen. It may not be for long. The other thing is that they can also do preparatory work for next year by beginning to drill. They can't go down too deep, but they can go down a bit to prepare for next year. So they can still meet their original goal of drilling up to ten wells in two years as long as they can get enough preparatory work in this summer.

Scientists worry that drilling for oil in the arctic will disturb wildlife and add to climate change which already threatens animals like polar bears. (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Scott Schliebe)

CURWOOD: Alex DeMarban is a reporter for the Alaska Dispatch in Anchorage. Thank you so much, sir.

DeMARBAN: Thanks, Steve. Appreciate the time.

Related link:

Alex DeMarban’s Shell Article in the Alaska Dispatch

[MUSIC: Patricia Barber "Hunger" from Mythologies (Blue Note Records 2006).]

Caffeine in Ocean Water

More research needs to be done to see what effect caffeine might have on fish. (Photo by Fiona Henderson)

CURWOOD: For coffee drinkers, the Pacific Northwest is holy ground. It's where companies like Seattle's Best Coffee and Starbucks got their start. But researchers recently discovered some surprising information in the land of coffee: caffeine in the ocean, lakes and rivers. And the likely source is the toilet.

Elise Granek is an assistant professor of environmental science at Portland State University in Oregon and is co-author of the new report finding caffeine in waters of the Pacific Northwest.

Professor Granek, welcome to Living on Earth.

GRANEK: Thank you for having me.

More research needs to be done to see what effect caffeine might have on fish. (Photo by Fiona Henderson)

CURWOOD: So how does caffeine get into the water?

GRANEK: Well, in the temperate zone in the northwest where we live, there is no known natural sources of caffeine. So, when we see caffeine in rivers or lakes or the ocean, our understanding is that the source is human waste. And that human waste may be from coffee, it may be from energy drinks, from pharmaceuticals, etc.

CURWOOD: Now, where exactly did you find this caffeine...in the ocean, in freshwater?

GRANEK: Our findings were actually quite surprising. Our design was set up to look at high pollution threat areas and low pollution threat areas, and our high pollution threat areas were areas of the Oregon coast with the highest human population densities where there was a wastewater treatment plant in the vicinity and there was a river flowing into that ocean area.

The Oregon coast. (Photo: Daniel Powell)

Low pollution threat areas were sites far from population centers with no wastewater treatment plant for at least five miles and no river flowing into the ocean for at least a mile. And, surprisingly, our highest levels were at our low pollution threat areas, much to our surprise.

CURWOOD: Why do you suppose that is?

GRANEK: So, in high human population density areas, there's wastewater treatment plants that are treating human waste. Although wastewater treatment plants in the U.S. are reported to only have about a 60-70 percent efficiency rate at removing caffeine, that's probably enough to remove most of the caffeine and the remainder is diluted out.

Whereas at sites where there's low human population densities, those communities are usually not on a centralized wastewater treatment plant. So, instead, each household or business has its own on-site disposal system, and on-site disposal systems have fewer regulations and monitoring requirements. When we're talking about on-site disposal systems, most of those systems are septic tanks.

CURWOOD: Now, why are you studying this? I mean, you're not concerned that the fish are having trouble sleeping, are you?

GRANEK: No, we actually haven't looked at the effects on fish. We've done some research looking at the effects on inter-tidal mussels.

CURWOOD: And the results there?

GRANEK: In terms of a general understanding of amounts, it's a very small amount. What we found, the maximum we found in the ocean was 45 nanograms per liter. And the maximum we found in an adjacent river was just over 150 nanograms per liter. So we're talking about a very small amount.

However, in our lab study on effects of caffeine, 50 nanograms was the lowest dose we looked at in terms of effects on mussels. And, that was enough of a dose to cause mussels to generate stress proteins. There have been some reports that caffeine may affect reproduction. When organisms are stressed, they produce stress proteins to protect their cells. And, if an organism is under prolonged stress, then that organism may have to shift energy they would normally spend on growth and reproduction, on continuously making those stress proteins. So, that's one piece of it.

Elise Granek’s team found evidence of caffeine in mussels they tested near the Oregon coast. (Photo: John Ash)

The other piece is that caffeine may be a marker, is likely a marker of other contaminants that accompany it in wastewater. So when we see caffeine, we expect it to be an indicator of wastewater, and in wastewater we have not only caffeine, but pharmaceuticals, we have household cleaners, we have a suite of contaminants which have the potential to impact these marine organisms, as well.

CURWOOD: So, how much of a human health risk is all of this caffeine in the water?

GRANEK: You know, some chemicals bioaccumulate in tissues. We don't expect that caffeine bioaccumulates in tissues but, again, it may be an indicator of other contaminants and other chemicals that are able to bioaccumulate in tissues. And so, people that are eating intertidal mussels, for example, if there's high levels of caffeine at those sites, we are interested in finding out what other contaminants may be accompanying that caffeine at those sites, and whether any of them are contaminants of concern for human health.

CURWOOD: Now, your research is based in the Pacific Northwest but I understand that researchers have found caffeine in water all over the country, including my backyard of Boston Harbor.

GRANEK: Correct, yes.

CURWOOD: And so how prevalent is this?

GRANEK: At least in the U.S., there are published numbers for Kauai in Hawaii, for Miami River and Biscayne Bay in Florida, for Boston Harbor, Sarasota Bay, Florida, and Jamaica Bay, New York and at least one site in Canada.

CURWOOD: So, Professor Granek, what needs to be done next?

GRANEK: I think, first of all, we need to identify the sources. Once we identify the sources of these contaminants, if they are indeed on-site septic systems, our ultimate goal is to provide information that will inform management and policymaking to reduce the level of contaminants that are entering marine systems.

CURWOOD: Elise Granek is assistant professor of environmental science at Portland State in Oregon. Thank you so much for taking this time.

GRANEK: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

[MUSIC: Duke Pearson "Black Coffee" from Profile & Tender Feelin's (Fresh Sound Reissue 2012).]

CURWOOD: Just ahead - it's a shark's life. Stay tuned to Living on Earth!

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Lee Ritenour "Space Glise" from Captain Fingers (Sony Music 1977)]

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

Coming up: Riding in South Dakota with a hero. But first this Note on Emerging Science from Annabelle Ford.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Science Note: Aerographite

Aerographite is comprised of 99.99% air. (Photo: TUHH)

FORD: Imagine a material six times lighter than air and 75 times lighter than Styrofoam. It exists. Scientists at Kiel University and Hamburg University Technology have created it, and call it aerographite. Aerographite is the newest, lightest material on earth. It weighs only 0.2 milligrams (CORRECTED-editor) per cubic centimeter, which is four times lighter than the previous record holder.

The key to its composition is a web of tiny carbon tubes but, surprisingly, that only makes up .01 percent of the material. The other 99.9 percent is air. And it turns out that there is a lot of potential for this surprisingly strong material which is electrically conductive and can withstand both compression and tension.

Not only can aerographite be compressed 95 percent, but it can be pulled back to its original form without any damage. This lightweight champion can also hold up something 40,000 times its own weight. Scientists are thinking about applying these properties to green transport technology- more specifically, vehicle batteries.

Because aerographite is both lightweight and electrically conductive, it could be used to create micro-batteries that are much lighter than any battery that currently exists now. This, in turn, would allow electric cars and e-bikes to function more efficiently because of their reduced weight.

The researchers see other potential for aerographite in water filtration and air purification for incubators. And factories that produce plastic can easily produce aerographite in their current facilities, since it's simple to create. It seems that there are a lot of ways to make this lightweight material have a heavy impact. That's this week's Note on Emerging Science. I'm Annabelle Ford.

Aerographite is comprised of 99.99% air. (Photo: TUHH)

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME ENDS ]

Greenland Sharks: The Apex Predator

Scientists are trying to figure out how Greenland shark behave in the cold, Arctic waters. (Photo: Jeffrey Gallant, GEERG)

CURWOOD: Science research often takes place at the edge, along a frontier. For some researchers, like shark expert Greg Skomal, that edge is the very boundary between their own life and death. Producer Ari Daniel Shapiro reports on Skomal's search for one shark living in an extreme environment.

SHAPIRO: Greg Skomal is a thrill seeker.

SKOMAL: There's a lot of things that drive human beings to do what they do. But for me, you know, it's that anxiety, that edge, that mix of emotions, the clashing of human logic with human heart. Like two currents smashing together. Until one wins, it's a roller coaster ride.

SHAPIRO: And there's one kind of creature that does this for Skomal that gets him on that roller coaster ride again and again.

SKOMAL: Sharks.

SHAPIRO: Skomal is a biologist with the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. He's in the water with sharks every chance he gets. Case in point: the Greenland shark, or Somniosus microcephalus.

SKOMAL: The Greenland shark basically looks like a cigar - short fins, big nose. Not the most attractive shark I've really ever been in the water with. Due to the fact that this shark lives under six feet of Arctic ice for most of the year, we just don't know a lot about it. So our goal was to get up there in the Canadian Arctic and try to figure out how this animal behaves under the ice.

SHAPIRO: And why were you interested in this question kind of in the large picture?

SKOMAL: We live on a changing Earth where ice is breaking up, where global climate change is occurring. And we want to know what the implications are for the ecosystem in the Arctic region, and part of that ecosystem is the Greenland shark.

SHAPIRO: Greenland sharks are apex predators. Nothing eats them, but they eat ringed seals. And Skomal wanted to figure out how the sharks hunt down these seals. Because, from his perspective, there are two big obstacles for the sharks. First:

SKOMAL: It has a parasite that bores into its eyeball that renders it virtually blind. We think the eyeball operates more like a light sensor.

SHAPIRO: So the sharks can't see the seals very well. The second obstacle has to do with the water temperature. It's bitterly cold. The salt allows the water to plunge a few degrees below freezing without turning it to ice.

Scientists are trying to figure out how Greenland shark behave in the cold, Arctic waters. (Photo: Jeffrey Gallant, GEERG)

SKOMAL: Life in cold water, it tends to have very low metabolic rates. So these sharks reflect that - they're very sluggish, very slow.

SHAPIRO: Too slow, it seemed, to catch a fast-moving seal.

SKOMAL: This shark's taking half a minute to move its tail just from one side to the other. You know, you look at a dog, you get something, you look at even a snake - you get something - it looks at you, its tongue moves, something happens. You look at a Greenland shark and all you get is this sense of: I'm a completely lifeless individual that's gonna live my life the way I wanna live it, and I'm not betraying anything to you.

SHAPIRO: But Skomal wanted answers. He wanted to figure out whether these sharks ate only dead seals, or if they could hunt live seals. So he set out to spy on the sharks, to see if they hung out where the seals were living, in the thick ice layer.

SKOMAL: We used something called passive acoustic telemetry, which basically means you put a pinger on the shark, you let it go, and you set up listening stations around the area to find out what the shark does.

SHAPIRO: That is, where it moves underwater. To attach the pingers, he and his team dug holes in the ice, cast baited fishing lines into the water, and brought the sharks to the surface, one at a time. Which is when Skomal, wearing his scuba gear and dry suit, would descend down through the hole and into the icy water below.

SKOMAL: It's an incredibly eerie world to be in because there's no sound. You're in gin-clear water - it's like being in a giant martini. And there before me is an eight, nine or ten-foot Greenland shark. You can keep them from swimming away because they're so cold in this environment. And believe me, being in that water does slow you down as well. I was comfortable for roughly about 15 minutes. Once your body core cools down, you need to get out of the water. You're working in water that is deep so if you have buoyancy issues, you sink to the bottom, you're dead. If you can't find your ice hole, you get disoriented, you're dead. So there's always that gnawing at the back of your brain.

SHAPIRO: On numerous dives, Skomal did manage to stay focused and attach pingers to the dorsal fins of six Greenland sharks. And later, when he got the data back, he reconstructed their 3D paths.

Marine biologist Greg Skomal goes to the Arctic whenever he can to find out more about Greenland sharks. (Photo: Clarita Berger)

SKOMAL: We thought, well, perhaps it will spend all its time on the bottom, just snarfing up like a vacuum seals that die. And, certainly, a couple of the sharks did that. But remarkably, a couple of the sharks ventured close to the ice-bound surface in areas where there were seals.

SHAPIRO: Skomal thinks the sharks may use their big noses to follow a seal's scent trail to the surface, and their eyes to discern the bright hole in the ice ceiling where the seal would be living, and finally -

SKOMAL: These sharks have an amazing mouth. They have an ability to latch onto something, literally suck onto it, and feed on it. Unsuspecting, the seal may drown as the shark drags it under. We think that might be the mode that this shark is using. Never observed, but derived indirectly from our technology.

SHAPIRO: This research almost doubled what was known about the Greenland shark, and that pleases Skomal a great deal. But the fieldwork, the diving beneath the ice also brought him to that edge he so adores - the place where logic and emotion face off.

SKOMAL: When you reflect back on it, you say, "Wow, that was incredible!" Not only being in probably the most inhospitable environment I've ever been in, but getting to see a species that very few people on Earth have ever seen. Underwater with a live Greenland shark. That, in and of itself, just drives me forward to want to keep doing these things.

SHAPIRO: For Living on Earth, I'm Ari Daniel Shapiro.

Related links:

- Read Greg Skomal’s bio

- One Species at a Time

- The Canadian organization GEERG - Greenland Shark and Elasmobranch Education and Research Group

[MUSIC: Tom Verlaine "Avanti" from Warm And Cool (Thrill Jockey Records).]

CURWOOD: Ari's story on Greenland sharks comes to us from the series One Species at a Time. It's produced by Atlantic Public Media and the Encyclopedia of Life. Learn more at our website, loe.org.

[MUSIC UP AND FADES UNDER]

Speaking of Sharks

(Photo: FlickrCC/Carl N San Diego)

CURWOOD: Every year, around this time, we're reminded... to stay out of the water:

[SHARK WEEK AD CLIP: Shark, shark shark.... No, sorry, shark week, shark week!]

CURWOOD: For the past 25 years, the Discovery Channel has paid homage to that most fearsome of apex aquatic predators: the shark. But for centuries, sharks have captured our imagination... and our language.

Perhaps more than any other animal, we use sharks in common expressions and metaphors. Living on Earth's Ike Sriskandarajah separates the sayings from the science of sharks.

Shark Week has become something of a national holiday.

SRISKANDARAJAH: We use animals as metaphors all the time. Lambs are gentle, bees are busy and sharks... well, sharks mean a lot of things.

MCKEAN: Obviously, we wouldn't have nearly 25 years of Shark Week if they weren't so gripping and hard to tear your eyes away from.

The great white. (Photo: Wikimedia)

SRISKANDARAJAH: Erin McKean is here to help us understand how we use sharks in language. She's the founder of Wordnik, a large online dictionary and is a language expert.

MCKEAN: Lexicographer is the generic term.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And to tell us if our sayings have anything to do with the real life kings of the ocean, is a man who lives every week like it's shark week.

GRUBER: Yes, and I must tell you that I was on the very first one. They sent a group down to our research vessel and did the first shark week interview with us.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Samuel Gruber, better known as Doc, was on the cutting edge of shark research back then. He now runs the shark lab at the University of Miami. We gave a list of shark inspired phrases to our two experts. First up: "sharkskin." A shiny fabric that mimics the gray sheen reflecting off a shark, used to make suits.

MCKEAN: When they first came out, of course, they were very fancy and because they were very fancy and then because they were very fancy they got knocked off in cheap materials extremely quickly.

SRISKANDARAJAH: A sharkskin suit became associated with a man who's dressed a little too slick to be trusted.

Sharks’ need for constant motion has drawn much comparison, but is a misconception. Many sharks can remain motionless.

MCKEAN: A low rent mobster in a sharkskin suit. Unless you're extremely odd, the fabric itself is not real sharkskin.

GRUBER: The first thing about sharkskin is it's an amazing structure. It's an armor plating of tiny little teeth.

SRISKANDARAJAH: "Dermal denticles"--- these tiny teeth let sharks swim faster and quieter. Though few people are cloaking themselves in real sharkskin, the material has been used all over the world.

GRUBER: They used to make gloves out of them. They would use the gloves as sandpaper to make fine furniture, and they also used the gloves to make billiard balls round.

“Card sharks” prey on rich flounders.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Which brings us to our next phrases.

[SOUND OF POOL BALLS BREAKING]

SRISKANDARAJAH: The pool shark, the loan shark, and the card shark.

MOVIE CLIP ROUNDERS: The game in question is no limit Texas hold'em, the stakes attract rich flounders, and they in turn attract the sharks.

MCKEAN: Part of it is being helpless in the face of a stronger power. The loan shark has all the power because they have the money. The card shark has all the power because they have skill that you don't have.

SRISKANDARAJAH: But while the human sharks exploit power, Doc Gruber says, the real sharks use time.

The shark feeding frenzy has been used to describe the financial industry.

GRUBER: We call them the lords of time, because of their ancient evolutionary history and their survival for half a billion years, so they're playing the game in a way that most things can't because most things aren't that highly evolved.

SRISKANDARAJAH: A group of sharks is called a shiver. And if there's "blood in the water," that shiver might go into what's known as a "feeding frenzy."

TV: About 50 sharks were counted in this feeding frenzy.

SRISKANDARAJAH: This turbulent behavior, according to Erin McKean, has become a metaphor.

MCKEAN: And these metaphors, ff they're really successful, they take on lives of their own.

BANKER ON TV: Wow, it's like one of those Jacques Cousteau films where the sharks are in a feeding frenzy, except this time it's a bunch of bankers.

SRISKANDARAJAH: . . . in unrestrained financial competition.

BANKER ON TV: There's allegedly a feeding frenzy that could happen on Wall Street.

GRUBER: If you look at the so-called feeding frenzy, if you analyze that, you find that there's a lovely ballet and that the sharks are not frenzied at all. They're very careful in where their mouths go so that they don't bite one another. They're very cautious when they do this apparent frenzy.

“Jump the shark” means running out of ideas and resorting to cheap gimmicks.

SRISKANDARAJAH: And our final phrase doesn't have anything to do with money or power. "Jump the shark." an expression originally derived from a landmark episode of the popular 70s TV show, Happy Days.

[HAPPY DAYS: SUSPENSE MUSIC]

SRISKANDARAJAH: Lexicographer Erin McKean.

MCKEAN: There was this scene in Happy Days where Fonzie water skis and jumps over a shark to prove that he really is the coolest person in the universe.

[HAPPY DAYS: He's ready to make the jump... There he goes!]

MCKEAN: But of course, it was so contrived. So jumping the shark means to do something in a story that is so over the top that everything after it just seems dumb.

[HAPPY DAYS: Cheering]

GRUBER: Ho, ho, ho, happy days.

SRISKANDARAJAH: So the obvious question for shark expert Doc Sam Gruber: In this preposterous storyline, how high would the Fonz have to jump... if the shark jumped, too?

GRUBER: I love that question because I always say to people, 'alright, this is your chance to ask the shark doc about sharks. For instance, how high can a shark jump? Some sharks just can't jump but there are sharks that can jump 25, 30, 35 feet out of the water.

SRISKANDARAJAH: That could be a pretty risky stunt if it all lined up.

GRUBER: It would have to line up in a really weird way.

SRISKANDARAJAH: The Fonz made it but in doing so, it gave us another phrase that in some way shades sharks as big fish who've run out of good ideas. On top of being power-hungry, out of control, cheats.

GRUBER: You know, we love our monsters, we love to hate our monsters, so we make sharks into monsters for humans that emulate this nasty creature. It's just a myth but it works.

SRISKANDARAJAH: Maybe one reason why it works, is because maybe we're not so different after all. For Living on Earth, I'm Ike Sriskandarajah.

Related links:

- Erin McKean’s Wordnik defines sharks as 1) marine carnivorous fish and 2) a ruthless person

- “Doc” Sam Gruber runs the Bimini shark lab at the Univeristy of Miami

[MUSIC: Morphine "Sharks" from Yes (Rykodisc 1995)]

The Place Where You Live

CURWOOD: And now for another trip to the Place Where You Live. Living on Earth's collaboration with Orion Magazine is giving voice to their long running feature that puts the favorite places of people on the map.

[Edward Sharpe "Home" from Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

POTTER: I'm Cassie Potter. I'm a freshman in college and I'm from Winfred, South Dakota.

Cassie Potter’s horse, Hero. (Photo: Cassie Potter)

CURWOOD: In this rugged part of the midwest, farming communities have a special relationship with animals, with the livestock they keep, the wildlife on the prairie, and the horses they ride. Cassie Potter has her own Hero.

POTTER: Hero, omigosh. I don't even know where to start with him. He was probably my best friend through, like, high school. I first got him in high school when I was rodeoing. He was a barrel horse. In rodeo, barrel racing, it's where there's three barrels set up in an arena and you race around in a pattern and whoever has the best time wins. In South Dakota, we get belt buckles when we win. I rode him every single day in high school, rain or shine, and he just had a huge influence on my life.

Winfred, South Dakota. (Photo: Cassie Potter)

MUSIC BRIDGE: [Bill Frisell "Shenandoah (For Johnny Smith) from Good Dog, happy Man (Nonesuch Records 2009)]

POTTER: On a late warm evening, I ride Hero, my high-spirited quarter horse, through one of my family's livestock grazing pastures. Our relationship is strong. As we journey together through the pasture, it is as if we are one in spirit.

Gentle breezes whisper in my ears and softly touch my skin, raising the tiny hairs on my arms. Blades of Kentucky bluegrass bristle against us as we stride through them. The grasshopper sparrows squeak and wrestle in the air as they snatch field crickets and meadow grasshoppers while crossing the rosy pink sunset.

In the distance, a small pond is alive with American coots swimming through the thick cattails. Mallard ducks quack and fly off in silhouettes. Leopard frogs croak loudly alongside the pond. Hero effortlessly crosses a shallow creek that runs peacefully through the pasture where my family and I have found small arrowheads left behind by the Plains Indians crossing the land years ago.

Black Angus cattle graze in the rolling grasslands of Winfred, South Dakota. (Photo: Cassie Potter)

The loud cackles of ring-neck pheasant echo across the rolling plains and our Black Angus cattle bed down for the night. Hero snorts abruptly as a small cottontail rabbit scurries into the pasture brush. Pesky mosquitoes remind me that it's time to head home. I drop my reins and Hero makes his way back. He knows his way by heart. As the world goes to sleep, I think how grateful I am for the place where I live.

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

CURWOOD: Cassie Potter lives in Winfred, South Dakota. She no longer rides Hero, who is now lame, but he continues to hold a strong place in her heart.

Tell us about "The Place Where You Live." You can find out about our collaboration with Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay by visiting our website loe.org.

Related link:

Let us know about “The Place Where You Live.” To post your essay on the Orion magazine website, click here.

CURWOOD: Coming up: the summer delight of heirloom tomatoes. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Breckinridge Capital Advisors, applying a sustainable approach to fixed income investing. www.breckindridge.com. The Grantham Foundation, for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world's most pressing environmental problems. The Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and Gilman Ordway, for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is Living on Earth on PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Azymuth: Last Summer In Rio" from Telecommunication (Milestone Records 1982)]

The Seed Underground

First Seeds Planted. (Photo: Flickr CC/Pictoscribe - Home again)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth - I'm Steve Curwood. A seed is a small thing, but it's wrapped up in huge issues - food, politics, history. Janisse Ray, author, gardener, and activist, trekked through farms and backyards in search of seeds and the stories connected to them.

Cover for Janisse Ray’s new book, The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food. (Photo: Janisse Ray

)

She's here on the line with us from her farm in Southern Georgia to talk about her new book, "The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food." Hello, there!

RAY: Hi, Steve, thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Why did you go searching for seeds?

RAY: I've been a gardener since I was a little girl. My grandmother gave me my first seeds, and I think it's just natural for me being a gardener and a seed saver to want people to understand what's happening to our seed supply, that our seeds are in jeopardy. We need to all be turning our head to look at seeds. Every morsel of food we put in our mouths is dependant on a seed.

CURWOOD: Now, in your book, you say that 94 percent of seed varieties that were available in the United States in the year 1902 are now gone. What happened to all those seeds?

RAY: What happened was genetic erosion due to a number of things. Fewer of us live in rural areas. You know, 80 percent of us are now urban. Fewer of us farm. In 1900, 41 percent, now less than two percent.

But I think the real reason is the industrialization of agriculture, which came about in the so-called 'green revolution' which ushered in chemical fertilizers, standardization, mechanization. I remember when my grandfather got a tractor, for example, and stopped working with mules.

CURWOOD: What do you think is the most important reason to be concerned about this loss in seed diversity?

Janisse Ray, behind her: Green Glaze collards, Running Conch cowpeas, Old-fashioned Running butterbeans, Moon & Stars watermelon, & Long County Longhorn okra. (Photo: Janisse Ray

)

RAY: Well, the more biodiverse any system is, the greater its chance for survival. And, we see what happened with the potato famine in Ireland. Ninety percent of Irish families grew a potato called the Lumper, but it began to suffer from late blight. That led to widespread famine and the Diaspora.

That would be our major concern but also, Steve, we're missing out on these myriad tastes; the beauty of our tables is diminished as we have fewer and fewer varieties to choose from. You and I can go into the grocery store and choose from a Granny Smith, or a Red Delicious, Yellow Delicious apple, but 100 years ago we had 7,000 apple varieties in this country.

CURWOOD: Now, by the way, the subtitle of your book is "Growing Revolution to Save Food." What is this revolution?

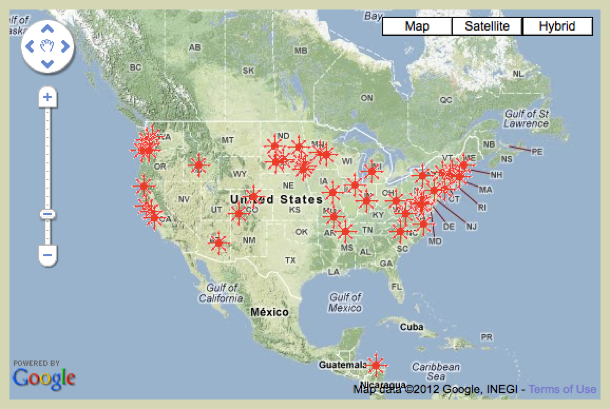

RAY: This revolution is happening in gardens across the country. I call these gardeners 'quiet revolutionaries' who've been on the margins, keeping alive these very interesting heirloom, place-adapted, vintage seeds.

CURWOOD: Lets talk about some of the seed savers in your book. Tell me about Will Bonsall in Maine.

RAY: Will is a very famous seed saver. He's been connected with the Seed Savers Exchange almost since its inception. Will has hundreds and hundreds of varieties that he's curating. . .a very dedicated man who's really committed his life to keeping alive old varieties.

He said to me that, you know, it would be a huge loss to humanity if his house happened to burn down. He has deep freezers that serve as seed banks. And he's right. I walked his gardens with him and there are just all kinds of amazing varieties growing there.

CURWOOD: In your book, you talk about Randy Gardener. He worked at a publicly funded plant-breeding program in North Carolina. Tell me about his operation and what happened to the seeds that he developed?

RAY: Randy works at a public institution near Asheville, North Carolina. He was a plant breeder there, so a government hired scientist. What he's doing there is developing tomatoes that are specifically adapted to the mountain south.

Over time, Randy was no longer able to support his work very well with government funding. And, what happened is that they developed some new variety, like this little new grape tomato that we are now seeing in grocery stores, and he would basically auction it off to seed companies. Basically, he would sell them the recipe for the seeds.

This brings us the question, Steve, of how should we be breeding our crops now? We need to still be breeding seeds to extend seasons, to adapt to lower inputs, to adapt to climate variability as we move deeper into climate change. And, do we want to have our government breeders simply be breeding for corporations, or do we want them to be breeding with the future of humanity in mind?

CURWOOD: Now, who owns seeds? And, what rights do farmers have to their seeds?

RAY: Seeds, I believe should be... they are part of the great commons of human history, like water and like air and like fire. Nobody can own fire. And I understand that we're favoring biotech companies and we're patenting life itself, but I believe those seeds belong to all of us.

CURWOOD: In your view, of course, it's important to save the genetic information that's contained in seeds, but you also talk about the culture associated with them. Why do you say that seeds have cultural information wrapped up in them, and why is it important to save that?

RAY: Most every heirloom seed, or open pollinated seed I know has a story. We are made of stories, stories are our culture, stories help explain who we are, why we're alive right now, what we're meant to be doing. The stories are enough for us to protect every variety of heirloom seed that is available, that is found. Seeds are only a small part of life on earth. But I think, in this case, they represent every thing else.

CURWOOD: Janisse Ray's new book is called "The Seed Underground: A Growing Revolution to Save Food." Thank you so much.

RAY: Thank you so much. I very much enjoyed it.

Related link:

Janisse Ray’s webpage

[MUSIC: John Ellis "Okra and Tomatoes" from Puppet Mischief (Obilquesound 2010).]

Hand-Me-Down Tomatoes

Tomatoes of all colors from Amy Goldman’s garden (Photo: Joanna Rifkin)

CURWOOD: And when it comes to heirloom plants, perhaps none are as diverse and tasty as tomatoes, although when we asked Living on Earth's Helen Palmer to check into heirloom tomatoes, as an Englishwoman she prefers to say:

PALMER: Tom-ah-to.

CURWOOD: Well, anyway, Amy Goldman wrote a gloriously illustrated book about tomatoes called "The Heirloom Tomato." And a few summers ago we sent Helen off for the fields of Rhinebeck, New York where Amy Goldman writes and tends her garden. Not only does Amy grow heirloom tomatoes, she's also a seed saver extraordinaire, fulfilling the mission of what we just heard Janisse Ray talking about.

[SOUND OF CRICKETS]

Amy Goldman in her tomato acre, where she grows 500 tomato plants. (Photo: Joanna Rifkin)

GOLDMAN: Tomatoes and I go way back. I started growing them when I was seventeen years old, and ever since then I've had my hands in the soil.

PALMER: Amy Goldman grows peaches and blueberries, melons and squash. She keeps ducks and chickens, and, of course, she grows tomatoes. Today she wears a long sleeved shirt and broad brimmed straw hat against the brilliant late summer sun as she shows off her crops.

[SOUND OF WALKING ON STRAW]

GOLDMAN: We're in the middle of Amy's Folly. This is an acre filled with 500 tomato plants, 250 different sorts, two of each.

Tomatoes of all colors from Amy Goldman’s garden (Photo: Joanna Rifkin)

PALMER: And unlike the tomato plants most of us buy from the supermarket, those four-packs of reliable hybrid varieties like Early Girl or Big Boy or Sweet 100, Goldman grows heirloom tomatoes.

GOLDMAN: The term "heirloom" - it means a tomato of value, capable of reproducing itself true to type, from seed that can be handed down to next generation.

PALMER: My backyard's a thicket of tomato plants. Goldman's heirlooms are arranged in neat rows. The six-foot tall cages are all clearly labeled, widely spaced, surrounded by straw.

GOLDMAN: The biggest mistake gardeners make is crowding them. I plant my tomatoes five feet apart in the rows and seven feet between rows. They need - first of all, they need full sun. They need air circulation and that reduces the incidence of disease, and allows the plants enough room to grow and prosper.

[SOUND OF WALKING]

PALMER: Goldman heads down the row to a tomato plant with tentacle-like branches sprawling out over the straw.

GOLDMAN: In this most horrible of tomato years this plant is going gangbusters. I mean it's moving across the garden at an alarming rate and, in fact, probably spreading out about eight to ten feet in diameter.

PALMER: This tomato's leaves are bright green, and it's laden with sprays of tiny currant-like fruits.

Amy Goldman, reporter Helen Palmer and a Sterling Old Norway heirloom tomato. (Photo: Joanna Rifkin)

GOLDMAN: Alberto Shatters. It's a very primitive plant. It shatters, it drops its fruit when the fruit is ripe. The tomato quality is superb. In fact, it's high in acid, high in sugar, very crunchy, and just wonderful. It's probably, if not the smallest, one of the smallest tomatoes in the world, weighing in at about a gram. You know, you can't even weigh it in ounces. It's about a gram and the size of a garden pea.

PALMER: They taste good and you think they're...?

GOLDMAN: Well, try it for yourself.

PALMER: I guess I'll have to. Let's see if I can find a ripe one.

GOLDMAN: Just give it a shake and they'll fall off.

Amy Goldman’s tomato field. (Photo: Joanna Rifkin)

PALMER: These pea-sized tomatoes pack a powerful flavor punch, but that's not their only value for Goldman.

GOLDMAN: Not only are they flavorful and historic and beautiful garden plants, but it's been found that plants' wild relatives contain genes that, bred into modern tomatoes, can confer disease resistance and other fine traits.

PALMER: That's one of the important lessons Goldman wants her heirloom tomato book to teach. She says the earliest wild tomatoes from South America's coastal highlands were small ones like these Alberto Shatters. The plant was domesticated in Mexico and gradually bred and selected to create all the varieties we know today. Goldman points to a huge plant in the next row, bending with the weight of bunches of egg-shaped tomatoes.

GOLDMAN: Now, I've got a tomato right down here called King Humbert, or Re Umberto. It's the forerunner of the San Marzano tomato, which is arguably the most important industrial tomato of the twentieth century.

PALMER: Let's go look at it.

[WALKING]

GOLDMAN: There's Re Umberto genes in every one of the plum tomatoes we know today. This was named in honor of Umberto I, King of Italy about 1878.

PALMER: One thing I'm noticing about it as I look at it is, it seems to be suffering less from the blight and the browning leaves than the others, and it's very, very heavily cropping. There are lots and lots and lots of tomatoes on it.

GOLDMAN: This is the value of this variety because it's low input. Generations of Italian peasant farmers have grown it because it doesn't require staking, it doesn't require watering or any attention whatsoever.

PALMER: Those generations of Italians - like peasant farmers across the globe - recognized the value of this crop, so saved some of the seeds to plant the next year. They passed them on to their children - and their grandchildren - that's the paradigm Goldman wants the rest of us to follow. Under many of her plants lie abandoned tomatoes, apparently rotting.

GOLMAN: I couldn't possibly eat all of the varieties that I grow and I joke I'm running a private CSA for my friends and family. But I'm a seed saver and advocate for biodiversity and those very ripe tomatoes, are destined for seed saving. That's next year's crop sitting there.

PALMER: Goldman's a board member of The Seed Savers Exchange, an Iowa based non-profit that's gathered over 25,000 varieties of heirloom vegetables in the last thirty-three years.

GOLDMAN: The mission is to stop the extinction of our food crops. We have developed a network of people who are dedicated to collecting, conserving and sharing heirloom seeds and plants, while educating the general public about the virtues of genetic and cultural diversity.

PALMER: Goldman wants to spread this knowledge. She says one to two percent of heirloom varieties disappear every year as hybrids take over, and we might need that genetic diversity for our food crops in the future. Her book also traces the history of some 200 luscious tomatoes. It includes taste tests and recipes, and celebrates their evocative names.

GOLDMAN: There's the Radiator Charlie's Mortgage Lifter, there's the Nebraska wedding tomato. You know, the heirloom tomato is the people's tomato. It's of, by and for the people. You know there's a tomato called "My Owna" because it's my own.

PALMER: And there's Black Prince, White Beauty, Silvery Fir Tree, Green Doctors, Plum Lemon, Purple Calabash, Sun and Snow. All shapes for all uses - cup-shaped ones perfect for stuffing, tiny cherries to pop like candy, mammoth meaty beefsteaks for sandwiches - and all sizes and all colors.

GOLDMAN: This tomato over here is the yellow peach tomato.

PALMER: It's not shiny.

GOLDMAN: It's not at all shiny - in fact, it's fuzzy like a peach. The yellow peach tomato. This is strictly garden to table - this is a rare treat that can only be grown by the home gardener. They're so fragile, but so wonderful. And I make a wonderful galette with the peach tomato and white peaches.

PALMER: So that's a kind of pie?

GOLDMAN: It's a kind of pie.

PALMER: Which goes to remind us that the chief joy of "to-mah-toes" - or "to-may-toes" - however you pronounce them - is to eat them. And though we nibbled our way up and down the rows, it's lunchtime.

[STARTING UP AN ENGINE]

PALMER: Goldman starts up the little garden cart she uses round the farm, to take us from the tomato field back to the farmhouse.

[BRAKING SOUNDS, BIRDS, CRICKETS]

PALMER: The smell of garlic and basil wafts out through the open kitchen door. Inside a dozen bronze casts of huge, perfect tomatoes and squash line the kitchen counter. A restaurant-size fridge and freezer hum and on the table are baskets of multicolored tomatoes.

GOLDMAN: We're making Spanish tomato bread. We toasted the bread with a little brush of olive oil - then scraped some garlic on it -- and what could be simpler? Put a little bit of tomato on top, maybe some salt, basil and you've got a treat that you'll live for all year. There's nothing in the world like a homegrown tomato. And heirlooms - my 35 years of experience as a grower, plus considerable book learning, have taught me that heirloom tomatoes ripened on the vine in full sun are the most delicious tomatoes of all.

Amy Goldman’s book, The Heirloom Tomato: From Garden to Table.

PALMER: And the tomatoes Goldman offered, and we ate, were indeed delicious. Goldman sent me home with a huge basket of assorted heirlooms, and I saved lots of the seeds for next year. For Living on Earth, I'm Helen Palmer.

Related link:

Amy Goldman's recipe for galette of white peaches and tomatoes

[MUSIC: Heirloom Tomatoes: John Denver "Homegrown Tomatoes" from Higher Ground (Windsatr Records 2005)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth: A young entrepreneur turns compost into a company, collecting food city folk throw away.

BROOKS: Exemplary contents here, you know, for someone's food scraps. It looks like there's some kale here, and some sort of gourd or something--I don't even know what that is...

CURWOOD: Reducing trash and making cash by recycling food waste, next time on Living on Earth.

[CRICKET SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with the sounds of summer.

[SFX - Lang Elliott and Will Hershberger, Songs of Insects Track 5 - Carolina Ground Cricket.]

CURWOOD: This is the trill of one of the most common crickets, the Carolina Ground Cricket. It's small, about a third of an inch long, and cold-hardy, and you'd find it hard to confuse its song with the two part trills of this one.....

[SFX - Track 5 - Carolina Ground Cricket segues to Track 9 - Confused Ground Cricket]

CURWOOD: The Confused Ground Cricket is found in woodlands in the eastern and midwestern U.S. But it isn't the cricket that's confused, it was the botanist Willis Blatchley who found it in leaf litter, and mistook it for the more widespread Carolina cricket. Lang Elliott and Will Hershberger recorded these trills for their CD The Songs of Insects.

[CONFUSED CRICKET SOUNDS CONTINUE]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Bobby Bascomb, Eileen Bolinsky, Bruce Gellerman, Helen Palmer, Jessica Ilyse Kurn, Ike Sriskandarajah, and Jeff Young, with help from James Curwood, Gabriela Romanow and Sammy Sousa. Our interns are Annabelle Ford and Annie Sneed.

Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at L-O-E dot org - and check out our Facebook page it's PRI's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the National Science Foundation, supporting coverage of emerging science, and Stonyfield Farm, organic yogurt and smoothies. Stonyfield invites you to just eat organic for a day. Details at justeatorganic.com. Support also comes from you, our listeners, the Go Forward Fund, and Pax World Mutual and Exchange Traded Funds, integrating environmental, social, and governance factors into investment analysis and decision-making. On the web at paxworld.com. Pax World for tomorrow.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth