June 28, 2013

Air Date: June 28, 2013

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Obama’s Grand Climate Plan

View the page for this story

President Obama has laid out a comprehensive and ambitious plan to reduce US carbon dioxide emissions from sources like power plants and expand the use of renewables and natural gas. Host Steve Curwood gets reactions from David Hawkins Director of Climate Programs at NRDC, Sierra Club’s executive director Michael Brune, and a student activist. (15:10)

Solar Powered Ship

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

The world’s largest solar powered boat made history by circumnavigating the globe. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports that the ship’s now busy in the Atlantic serving as an emissions free platform for scientists to collect data about the Gulf Stream. (08:15)

Oberlin Environmental Dashboard

View the page for this story

Technologies for creatively displaying energy and water use have grown quickly over the past decade, but most focus on resource use at the individual or building level. A new website applies this approach to the entire town of out of Oberlin, Ohio. The Oberlin Environmental Dashboard hopes to become a model for community-level resource conservation. Host Steve Curwood speaks with John Petersen, Professor of Environmental Studies at Oberlin and creator of the Oberlin Environmental Dashboard. (06:45)

Science Note- Cicadas Meet Citizen Science

/ Erin WeeksView the page for this story

Seventeen-year cicadas are coming to the end of their season, and a team at North Carolina State University wants citizens to send them cicada corpses. Measuring the dead insects can help show how urbanization is impacting the species. Erin Weeks reports on the citizen science project. (01:50)

"Trash"Animals

View the page for this story

Some species of animals, especially unloved invasive species like pigeons and carp are so reviled they're regarded as trash. Dave Johnson, co-editor of a new book of essays called Trash Animals, an essay anthology, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss how humans treat their co-inhabitors. (09:35)

Chasing Springtails

/ Ari Daniel ShapiroView the page for this story

The tiny creatures called springtails used to be described as insects, but were reclassified as a different order altogether called collembola a dozen years ago. There are 8000 species of springtails, and they're ubiquitous in caves, mountaintops, the tropics and the arctic. But Ari Daniel Shapiro reports that some species of collembola are facing extinction due to climate change and habitat loss. (05:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

Host: Steve Curwood

Guests: David Hawkins, Jon Petersen, Dave Johnson,

Reporters: Bobby Bascomb, Erin Weeks, Ari Daniel Shapiro

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. President Obama outlines bold plans for comprehensive action on climate change and lays down a marker on the Keystone XL pipeline.

OBAMA: Allowing the Keystone pipeline to be built requires a finding that doing so would be in our nation’s interest. And our national interest will be served only if this project does not significantly exacerbate the problem of carbon pollution.

HAWKINS: He has articulated what might be the Obama environmental doctrine, which is that it is against the interests of the United States to pursue activities which will make global warming worse.

CURWOOD: We take a broad look at the energy and climate actions the President is proposing. Also, the search for tiny creatures lurking in leaf litter. That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic smoothies, yogurt, and more.

Obama’s Grand Climate Plan

President Obama speaking about climate change at Georgetown University. (Photo: US Embassy)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, This is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In his fifth year as President, Barack Obama has unveiled a comprehensive and detailed plan to address climate change. On June 25, a hot and sweaty day in Washington, the President promised leadership at home and abroad, despite partisan divisions that block congressional action. Mr. Obama’s vision ranges from controlling power plant emissions to boosting renewables and efficiency, and helping cities and states prepare for the effects of the changing climate. Joining us now is David Hawkins, the Director of Climate Programs for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Welcome to Living on Earth.

HAWKINS: Thank you, Steve. Good to be here

CURWOOD: Well, first off, what did you make of this speech? What this the climate champion many people have been waiting for?

HAWKINS: This was a grand slam home run of a speech. The President articulated why we need to work urgently on the problem of climate disruption, and he identified sensible things that can be done that will not only help us slow the damage from climate change, but will provide a path for economic renaissance for the United States and deliver health benefits to the people in the United States at the same time. So he made a great case. And then, the third element was the content of the action plan where he is making as his centerpiece, going after the largest remaining unregulated carbon polluter in the United States, the dirty power sector. So this was a great speech.

CURWOOD: Alright. Let’s take a listen to the bit from the speech about the regulation of power plants.

OBAMA: So today, for the sake of our children, and the health and safety of all Americans, I’m directing the Environmental Protection Agency to put an end to the limitless dumping of carbon pollution from our power plants, and complete new pollution standards for both new and existing power plants.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: So from your perspective, Dave Hawkins, this is a pretty big deal.

HAWKINS: It’s a huge deal. We’ve been trying at NRDC to get a President of the United States to take this step for 20 years. And Obama is the one who stepped up and committed to do it. It flows from a Supreme Court decision in 2007 that declared that carbon dioxide is a pollutant under the Clean Air Act, despite President George W. Bush’s claim that it was not. And the court clarified that the EPA has full authority under the 40-year-old Clean Air Act to regulate carbon pollution from sources like automobiles, trucks, buses, power plants, refineries and other major polluters.

CURWOOD: Now many people weren’t expecting President Obama to talk about the Keystone XL pipeline proposal in his speech, but he came right out and said he wouldn’t approve the pipeline if it had significant impacts on our climate. Let’s take a listen.

OBAMA: I know there’s been, for example, a lot of controversy surrounding the proposal to build a pipeline, the Keystone pipeline, that would carry oil from Canadian tar sands down to refineries in the Gulf. And the State Department is going through the final stages of evaluating the proposal. That’s how it’s always been done. But I do want to be clear: Allowing the Keystone pipeline to be built requires a finding that doing so would be in our nation’s interest. And our national interest will be served only if this project does not significantly exacerbate the problem of carbon pollution. [APPLAUSE] The net effects of the pipeline’s impact on our climate will be absolutely critical to determining whether this project is allowed to go forward. It’s relevant.

CURWOOD: We’re going to take a listen now, Dave Hawkins, to Michael Brune. He’s the Executive Director of the Sierra Club who got arrested in front of the White House protesting Keystone. He has a pretty strong reaction.

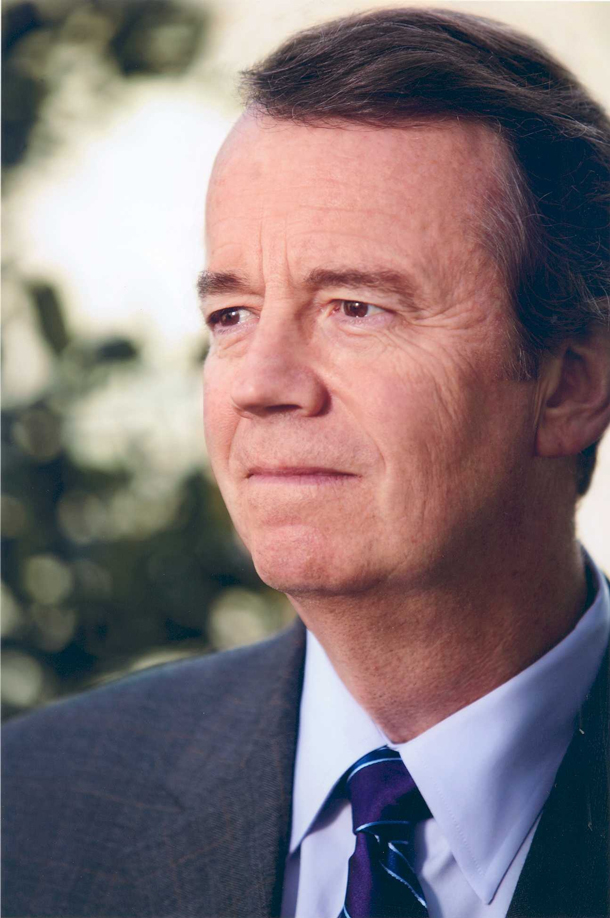

David Hawkins, director of climate programs for the Natural Resource Defense Council (photo: NRDC)

BRUNE: Well, this was another one of the bombshells of the President’s speech, and that he basically said he’s not going to approve the pipeline, because the pipeline won’t be in the country’s interests if it makes climate change much worse. And the reason why the Sierra Club and hundreds of thousands of people across the country have mobilized to stop this pipeline, is because it will do just that. It’s a pipeline taking oil from the dirtiest source of oil on the planet, and right at a time when we’re using less and less oil as a country, it would take our country in the wrong direction. And what the President said in his speech, is that we need to move quickly to invest in clean, zero carbon energy technologies - solar, wind, advanced batteries, green transportation, using conservation and efficiency more effectively. So, we’re more confident than ever this is a pipeline that will actually never be built.

CURWOOD: How much of a pledge to stop Keystone was his remarks? You’ve been down in front of the White House demonstrating. I believe you even got arrested and protested Keystone. Is this enough for you?

BRUNE: No. No, we will not rest in this effort until the pipeline is firmly rejected.

CURWOOD: So Michael Brune says Keystone won’t get built. What do you think Dave Hawkins?

HAWKINS: Well, the President’s Keystone remarks are another big deal. In fact, it’s even bigger than Keystone itself. What the President said is that there’s a new test of what’s in the national interest, and that is whether an activity makes global warming worse. And he has articulated what might be the Obama environmental doctrine which is it’s against the interest of the United States to pursue activities that will make global warming worse. That is a very big deal. As far as the Keystone pipeline itself is concerned, he has set up a test for that pipeline - will it make global warming worse? We think the facts are clear, it will, and it will flunk that test.

CURWOOD: Now, the President asserted his commitment to using natural gas a bridge fuel to a clean economy, but natural gas still has carbon in it. What about the problems with fracking, Dave Hawkins?

HAWKINS: Well, the good news about natural gas is that it has half the carbon pollution of coal. And the bad news about natural gas is that it has half the carbon pollution of coal. We can use some natural gas, but if we use a lot of it, in order to protect the climate, we’re going to have to capture the carbon from that natural gas we use. And we have to pay attention, much better attention, to what’s produced. We have to make sure that the wells that are drilled to produce this gas are built more solidly, are leakproof. We have to make sure that the water waste is handled better than it is. We have to make sure that drilling companies have respect for the interests and wishes of the community, in which they wish to operate.

CURWOOD: Michael Brune also had some things to say about natural gas.

BRUNE: That was the one misstep in the President’s plan. The most significant one. We think natural gas is not a bridge fuel but more a gangplank to a destabilized climate. We need to be able to move beyond fossil fuels, and we have to acknowledge that doesn’t happen overnight. But what we should understand is that as we move off of coal, as we decrease our reliance on dirty oil, we can’t over-rely on natural gas. What we need to do is we need to be leapfrogging over dirty fuels and going all in on clean energy.

Leaders from around the world met in Istanbul, Turkey to organize action to tackle climate change. (Global Power Shift)

CURWOOD: Now some say natural gas has been undercutting the development of renewables because it’s become so cheap. Dave Hawkins, what do you make of that? Does it make sense to be looking to natural gas without, say, a carbon tax? Something to make the carbon in natural gas more expensive over time?

HAWKINS: Well, natural gas is very much a double-edged sword. It will beat out dirty coal, but it will also beat out renewables. So yes, we need a carbon pollution standard, and done right, a carbon pollution standard can help adjust the relationship between the natural gas and the competition so that it continues to beat out coal, but no longer beats out renewables.

CURWOOD: Now the President said he’s pushing hard for more investment in solar, wind, and other renewables. He says he wants 20 percent of power that the federal government uses to come from clean sources by 2020. Dave Hawkins, is this too ambitious? Not ambitious enough?

HAWKINS: It’s a nice target. But again, it points out the difficulty we have when we don’t actually directly value the carbon pollution. Because if we did, then we wouldn’t need a mandate for the federal government to use a certain amount of renewables. There would be a market reason to do it - saving money. Now, we’re spending the money, we’re just not spending it on the power part of our checkbook. We’re spending it on the health part of our checkbook. We’re spending it on the impacts of our kids that are going to suffer as a result of climate disruption. So we do have to value the carbon pollution from the power that we consume. The sooner we do that comprehensively, the better.

CURWOOD: Now President Obama talked about the US leading the world on climate change, Dave Hawkins, and helping poorer countries develop sustainably. Let’s have a listen.

.jpg)

Michael Brune is Executive Director of Sierra Club (Photo: Sierra Club)

OBAMA: Today, I'm calling for an end of public financing for new coal plants overseas [APPLAUSE] unless they deploy carbon-capture technologies, or there's no other viable way for the poorest countries to generate electricity. And I urge other countries to join this effort.

CURWOOD: Dave Hawkins, what do you make of that?

HAWKINS: I think that’s a very important step. The United States has been in the past, a promoter of dirty coal plants overseas. And those dirty coal plants are going to lock us into a climate disruption future so it doesn’t make any sense to do it. Now he made an exception in his statement for coal plants that are equipped with carbon capture and storage, and if it that helps deploy that important technology, that’s a good sensible step to take. And he made an exception for the poorest countries where there isn’t another viable option. And again, it strikes me as a sensible exception. We hope it will be the exception rather than the rule, but that is something that should be judged on the merits and the facts of each case.

CURWOOD: The President gave a lot of credit to old guard Republicans who took climate change seriously, but has no patience for climate skeptics.

OBAMA: Nobody has a monopoly on what is a very hard problem, but I don’t have much patience for anyone who denies that this challenge is real. [APPLAUSE] We don’t have time for a meeting of the Flat Earth Society. [APPLAUSE]

HAWKINS: I think what the President was saying was that people who are denying the reality of climate change are doing a disservice to people alive today and doing a disservice to people who will be born tomorrow. We do not have time to continue to argue about whether this is a problem because every day we continue that argument, we increase the size of that problem. I like to say about carbon pollution, once we’ve emitted, we are committed. Every day that we put a ton of carbon pollution into the air, we add to the damage of climate disruption that our kids are going to have to live with.

CURWOOD: The President spoke at Georgetown University to a mostly student audience, and he called on them to take on climate change, let’s listen to what he said.

OBAMA: [APPLAUSE] Convince those in power to reduce our carbon pollution. Push your own communities to adopt smarter practices. Invest. Divest. [APPLAUSE] Remind folks there's no contradiction between a sound environment and strong economic growth. And remind everyone who represents you at every level of government that sheltering future generations against the ravages of climate change is a prerequisite for your vote. Make yourself heard on this issue. [APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: David Hawkins, what do you think of this, the shout-out on divestment?

HAWKINS: Ah yes, I was at the speech as well. I was surrounded by enthusiastic students. It was a great event. And I think it was quite interesting and quite intentional that the President mentioned divestment. As we know, Bill McKibben has been leading an effort to get universities and colleges especially to divest their investments in fossil fuels. And I think that the President gave an appropriate acknowledgement and shout out and positive acknowledgement for that effort.

CURWOOD: What about putting the weight on fixing this problem with kids? Isn’t it our generation’s problem?

HAWKINS: Well, we’re the responsible adults supposedly, but we elect people to office. And today’s college students vote for those same people. Today’s college students can be a very important source of political pressure on the know-nothings and deniers who are still far too prevalent in our Congress. They have the potential to actually do something to force the adults to start behaving like adults.

CURWOOD: Now we spoke with some college students about the speech, let’s take a listen.

GRADY-BENSON: My name is Jess Grady-Benson and I’m a rising senior at Pitzer College working for the fossil fuel divestment campaign. I think there’s a very prevalent tendency to put the emphasis of the climate movement on young people right now - there are so many incredible youth activists out there all around the world doing amazing work right now. That being said, I think that’s a little bit of a cop out to neglect the responsibility of the generations - the generations that have come before us - and put our globe in the position that it’s in right now and the climate in a very dangerous tipping point.

CURWOOD: Before you go, Jess, tell me, what kind of overall grade would you give President Obama for his speech?

GRADY-BENSON: I have to say I’m a pretty tough grader. I think that he made a lot of very important points, but I have to say, for our national climate movement, for the global climate movement, there’s so much more to be done. So I would have to give him about a C or C-.

CURWOOD: David Hawkins, all in all, what grade would you give the President on his speech?

HAWKINS: The grade for this speech, I would say is an A. Whether the final grade for the course turns out to be an A or an A+ or a B or lower will depend on what is done to follow up in the next three and a half years before he leaves office. He’s got a lot of work to do to carry out the steps that he’s outlined in his speech. We applaud him for the speech. We’ll applaud him even harder when he gets the work done.

CURWOOD: David Hawkins is Director of Climate Programs for the Natural Resources Defense Council. Thanks so much, David.

HAWKINS: You're very welcome Steve. Glad to be with you.

CURWOOD: You can hear the President’s full speech and read his plan on our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

-

- Text of President Obama’s June 25, 2013 speech on climate change

- President Obama’s Plan for Climate Change

- About Dave Hawkins, director of NRDC’s Climate Programs

- NRDC on Obama’s Climate Speech

- About Michael Brune, executive director of the Sierra Club

- Sierra Club on Obama’s Climate Speech

- Global Power Shift

- Heritage Foundation Critique of President Obama’s climate plan by Nicolas Loris

- ConservAmerica call for measured Republican support of Obama Climate Plan

[MUSIC: Bonobo “Don’t Wait” from The North Borders (Ninja Tune records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up, around the world in 584 days with just the power of the sun. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

CUTAWAY MUSIC [Elmo Hope: “Low Tide” from The Final Sessions (Evidence records 1996)

Happy Birthday Elmo Sylvester Hope 06/27/1923 – 05/19/1967]

Solar Powered Ship

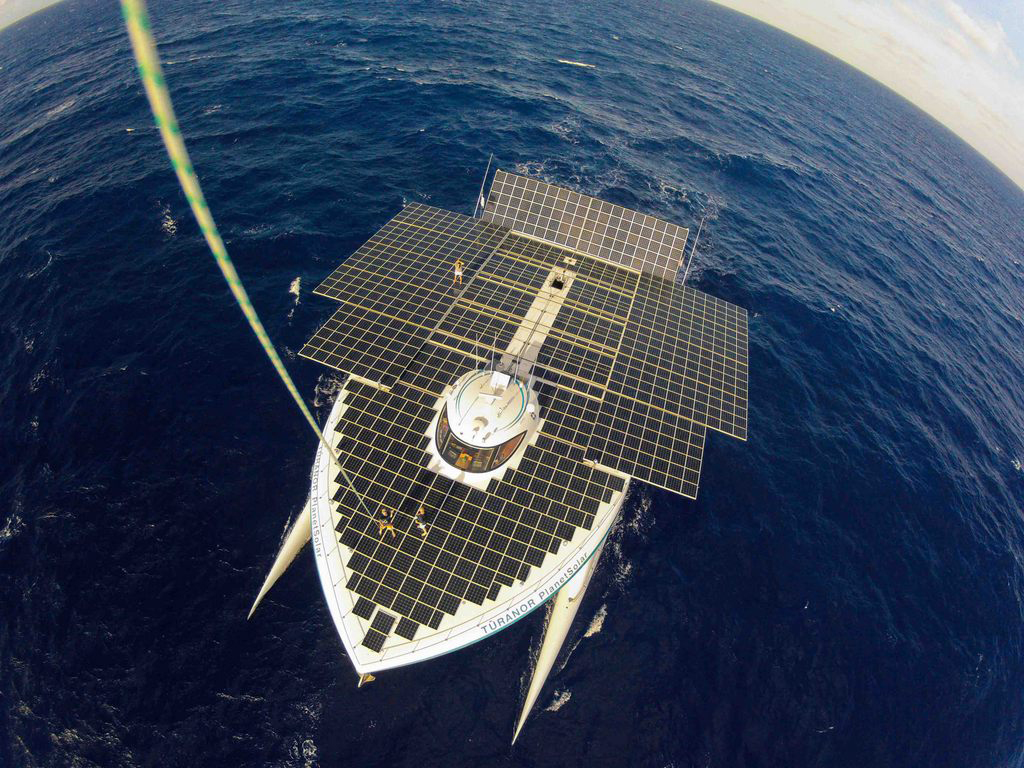

An aerial shot from at sea shows the all of the ship’s solar panels extended and absorbing energy to power the voyage. (Türanor Planet Solar)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. When the price of oil shot up a few years back, the large freighters that ply the oceans found they could save a lot of polluting bunker oil if they slowed down, when there was no hurry to deliver their cargo. So what if slow boats used no fossil fuels at all? One example is currently traveling up the US Atlantic coast - the world’s largest solar powered boat. The experimental ship made history by circumnavigating the globe using only sunpower - though it took a year and a half to make the trip. Now the ship, the Türanor Planet Solar, is not a freighter. It’s more of a science research vessel, and now it’s collecting data on the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean. The Türanor Planet Solar recently put in to Boston Harbor and Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb went aboard.

[WALKING UP STAIRS ONTO THE BOAT]

BROS DE PUECHREDON: Hi Bobby, I’m Rachel. Welcome on board. How are you today?

BASCOMB: Good. Thank you.

Rachel Bros De Puechredon is head of communications for Planet Solar. It’s an exceptionally hot sunny day in Boston Harbor; perfect conditions for showing off the world’s largest solar powered boat. It’s 101 feet long and 49 feet wide. The top deck of the white catamaran is covered with black solar panels. Inside though it looks just like a modern, functional ship.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: We are standing right now in what we call the living room. That’s where everything happens that is social…lunch, events, press conference and all that.

BASCOMB: The MS Türanor Planet Solar, gets part of its name from the Tolkein’s saga Lord of the Rings. Türanor means ‘the power of the sun’. This sun powered ship was designed by an engineer from New Zealand, built in Germany and is now home to five crew and four scientists from Europe.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: And here you go to the very tiny little kitchen. We don’t realize but from Miami to New York it’s 160 meals so our cook has a lot of work to do in here. And the only thing not powered by the sun is the oven. It’s gas. But everything else on this boat is powered by the sun. So what ever you plug on it - hair dryer or computer - it becomes solar.

BASCOMB: Mmm hmm.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: So, we want to go now to the top of the boat. Be careful, it’s a stair.

[WALKING UP THE STAIRS]

BASCOMB: Rachel leads the way up the stairs to the top of the boat. The entire deck is covered in solar panels, 38,000 solar cells in all. When it’s at sea extra panels slide out on each side like wings to a total surface area of more than 5,500 square feet.

The world’s largest solar powered boat enters New York City with its solar “wings” fully deployed. (Türanor Planet Solar)

BROS DE PUECHREDON: Usually you have two tennis courts of solar cells that you don’t see -even though it’s huge now.

BASCOMB: Yes, it really looks huge. It looks very space age, you know.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: It is a space ship, but it’s a space ship with an average speed of five knots. You have the impression it’s going to take off like a plane but it’s like oooh…very smooth and slow and super silent. That’s the great thing when you are on board you don’t realize that the engines are running.

BASCOMB: And the engines keep running around the clock.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: So, during the day we charge the lithium batteries that are on board so we can navigate through the night as well. Actually we can even navigate 72 hours in bad weather if there is no sun.

BASCOMB: So, if there’s no sun you’re still good for three days.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: Yes. Exactly.

BASCOMB: 10 tons of lithium batteries act as ballast to keep the ship stable, half in each of the two pontoons. They can store a megawatt of energy, enough to power a small house for three months.

BROS DE PUECHREDON: A small house, I don’t know, maybe not a US house. [LAUGHS]

The cockpit of the ship. (Poncie Rutsch)

BASCOMB: The cockpit is recessed into the deck and shielded with tinted glass. Navigation instruments and electronic screens surround the captain’s seat.

DABOVILLE: My name is D’Aboville my first name is Gerard. As you can hear I am from France and I am the captain of this strange vessel.

Gerard D’ Aboville, captain of the Türanor Planet Solar, stands on the deck of the ship with the Boston skyline behind him. (Poncie Rutsch)

BASCOMB: Gerard D’Aboville was the first person to row solo across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He says the world’s largest solar powered boat attracts a lot of attention where ever it goes.

D’ ABOVILLE: I’ll tell you a story. We had to stop in Morocco outside of the port because the tide was not good so we had to stay for a few hours and we were in the distance from the shore and it was a bit misty so people could see something but not really what it was. And several called the police and said there was an airplane which has landed onto the water! What should we do? [LAUGHS]

The ships galley is home to the only non-solar powered item on the boat, a gas powered oven. (Poncie Rutsch)

BASCOMB: It is sort of a space age looking thing, it’s all covered in these black panels.

D’ ABOVILLE: It is probably very strange looking. One day in the Mediterranean we passed a ship and the chap called us on the radio it was a Filipino guy and he said, ‘Sir, may I ask you a question?’ and I say, ‘Yes of course’. ‘What is it? Is it a spaceship?’ [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: Captain D’Aboville calls the ship an ambassador for solar energy. It’s also uniquely qualified for research, which is the main purpose of this summer long voyage. Scientists from the University of Geneva in Switzerland are on board to study the Gulf Stream. Because the ship has no emissions scientists can collect data completely untainted by exhaust. Martin Beniston is head of the Institute of Environmental Sciences at the University of Geneva.

Martin Beniston (left) and Bastiaan Ibelings (right) are researchers from the Universtity of Geneva spending the summer on board the Türanor Planet Solar. (Poncie Rutsch)

BENISTON: The overall goal of this expedition using this Planet Solar solar boat is to look at some of the more subtle interactions between the atmosphere and the ocean as we move out into the Gulf Stream and into the colder waters of Newfoundland.

BASCOMB: Beniston describes the Gulf Stream as a huge river of heat that moves north from the Caribbean. He says Europeans are particularly interested in the Gulf Stream because it has a dramatic effect on air temperatures in Europe. The UK for instance, in roughly on the same latitude as northern Canada, but has a mild winter similar to Maryland.

BENISTON: The reason why it’s more temperate in western Europe than here in New England especially in winter is simply because you’ve got this heat from the ocean. The winds that blows off the ocean will transfer this heat to the continent, so keeping the temperatures 20 or 30 degrees milder.

The Swiss flag flies over the solar deck of the ship in Boston Harbor. (Poncie Rutsch)

BASCOMB: But scientists are concerned that melting arctic ice due to climate change could alter the path of the Gulf Stream.

BENISTON: If the Gulf Stream were to change its behavior because of climate change the Gulf Stream could actually slow down to such an extent that cold conditions could come to both sides of the Atlantic in a way. We don’t believe that’s actually going to happen in this century though it is physically plausible.

BASCOMB: Researchers are also collecting data on phytoplankton, the tiny micro organisms that form the base of the food chain and are a critical component for sequestering carbon.

IBELINGS: Phytoplankton in the ocean fix about half of all the carbon on the planet so they buffer climate change.

BASCOMB: Bastiaan Ibelings is a professor of microbial ecology at the University of Geneva.

IBELINGS: Phytoplankton face a challenge in the ocean because they need light for energy and the light is only available in the upper part of the ocean so you need to be close to the surface but phytoplankton also needs nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen and they tend to come from deep down in the ocean in a process known as upwelling. So it’s the mixing, the physical mixing of the ocean that combines the resources that phytoplankton need to grow.

BASCOMB: As the ocean warms at the surface it inhibits the upwelling.

The Turanor Planet Solar docked in Boston Harbor. (Poncie Rutsch)

BELINGS: The nutrients that are still deep down in the ocean are not available to the same extent that they were in the past for phytoplankton growth. So if phytoplankton is unhappy because of what climate change is doing to their life in the ocean it may actually feed up climate change because there will be more CO2 in the air.

BASCOMB: The scientific team on the Türanor Planet Solar is researching all these questions the voyage continues up the east coast to Canada and then Iceland. They’ll finally head back to Europe at the end of the summer. For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb, soaking up the sun in Boston Harbor.

Related link:

Follow the route of the Türanor Planet Solar at their website

[MUSIC: Broadway Project “Solar, Lunar” from In Finite (ODS Recordings 2008)]

Oberlin Environmental Dashboard

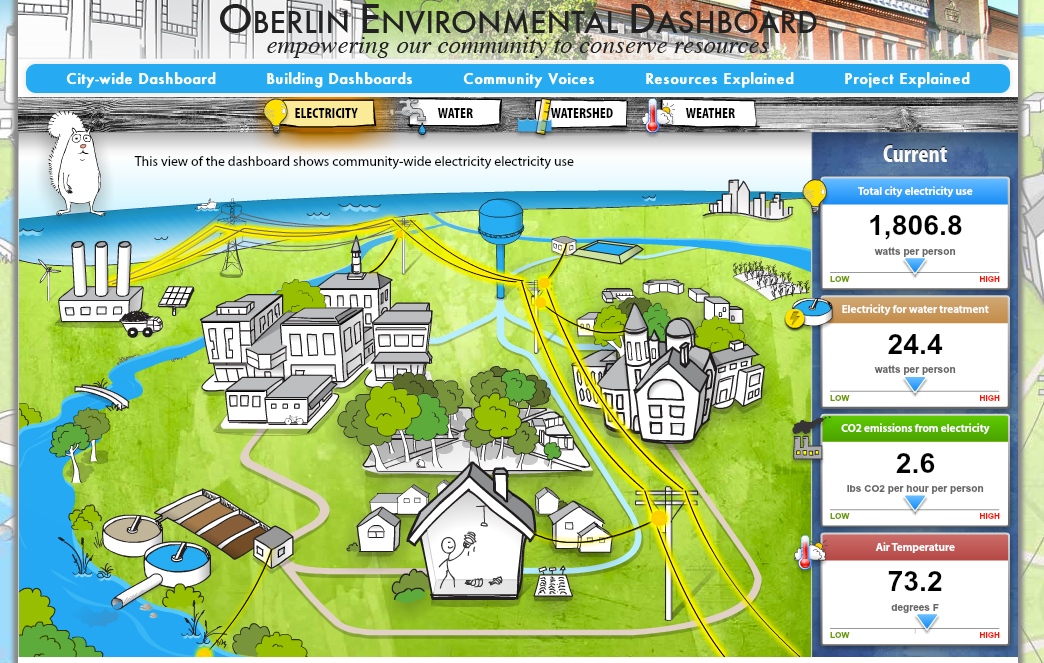

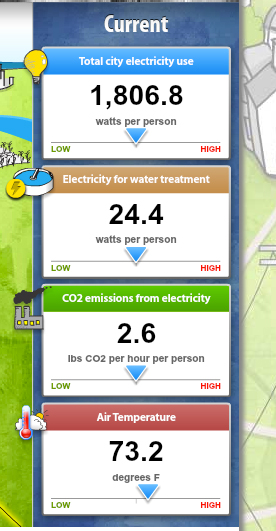

Oberlin City-wide Dashboard (Photo: oberlindashboard.org)

CURWOOD: They say that a picture's worth a thousand words - and the city of Oberlin, Ohio, has taken that to heart. It's pioneering a new website that uses entertaining graphics to show the entire town’s electricity use, water flow, and even water quality - all in real time. The developers call it the Oberlin Environmental Dashboard, and hope it will become a model for motivating community wide energy conservation, not just in Oberlin, but across the region. Jon Petersen teaches Environmental Studies at Oberlin College, and is one of the developers. And I went to see him to find out exactly what an environmental dashboard is.

PETERSEN: Well, an environmental dashboard is basically a technology and an approach taking information about resource flows that take place in the world around us and translating that into a form that’s easily accessible to people who might not be so technical, so that they can understand the ways in which they’re engaging with resource flows and their decision making process.

CURWOOD: In other words, every picture tells a story?

PETERSEN: That’s absolutely right. We’re trying to create these sort of compelling animated graphics that convey to people in a way how their resource consumption is actually affecting the world around them.

Professor John Petersen (Photo: Oberlin College)

CURWOOD: So what’s different about the Oberlin dashboard project that’s different from other visual displays people have tried?

PETERSEN: So a lot of people out there are beginning to develop new technologies to monitor and display energy flows, electricity flows in buildings. And there’s been some really neat developments along that line in the last 10 years. What separates what we’re doing from what other people are doing is that we’re trying to monitor not just resource flows in individual buildings, but resource flows at the whole community scale as well as environmental quality.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s go online and take a look at your site. And if you’re at home listening and you want to do this too - it’s OberlinDashboard.org.

Sidebar showing town’s electricity use (Photo: oberlindashboard.org)

[TYPING ON KEYBOARD]

CURWOOD: OK. Let’s take a cruise through here. So, what are we seeing here, Jon?

PETERSEN: This is the citywide dashboard you’re looking at. Basically, what we’ve tried to do is create an animated cartoon model of a community. So you’re looking at the freshwater treatment plant, the wastewater treatment plant, the electricity production facility, the river that drains our community. And you’re watching electrons flow down power lines; you’re watching water flow down pipes through this model...

Community Voices features local schoolchildren (Photo: oberlindashboard.org)

CURWOOD: And there’s black smoke coming from the power plant.

PETERSEN: [LAUGHS] There is black smoke coming from the power plant. Well, like many communities in the mid-west, we’re still getting a lot of our power from coal fired power plants. But you also, if you look closely you see there spinning wind turbine, and you see a solar panel there, we’re getting our power from those too.

PETERSEN: And let’s go to straight water here. Alright, so now what we’re looking at is how many gallons per person is being used within Oberlin right now. So I’m seeing 2.2. gallons. That’s not a whole lot of water being used per person per hour, but that’s going to change over the course of the day. So if you look at that in the morning, you’re going to see high use because people are taking showers. There are times of day when our little bit of light industry within Oberlin is going to be using more water.

Community Voices (Photo: oberlindashboard.org)

CURWOOD: Let’s look at electricity...total electricity city use watts per person. It’s almost 2,000 watts per person right now.

PETERSEN: Yes, that’s a very large number. You have to consider with a number like that is, that’s including the industry we have in Oberlin. But it does give you a sense of what’s the sort of amount of total energy that’s being used to support the whole community.

CURWOOD: So tell me what are the values we’re seeing on the right hand side?

PETERSEN: We’re looking at water quality right now, for instance. So you’re seeing how deep the water is in the local river, so that’s going to change based on when the last rainstorm was. You’re looking a dissolved oxygen, you’re seeing turbidity - that’s how much cloudiness is in the water. So that’s telling me about how much soil is running off from agricultural fields, and you’re seeing PH, which is also a basic indicator of water health.

CURWOOD: So far, what’s been the response from the Oberlin community to this?

PETERSEN: I think our best response has really been among school-aged children. Part of that is...one of our displays is very prominently located in the hall of Prospect Elementary, which is a three through five public school. And we do actually see children as being central to this process. Not just as recipients of information, but one of the things that we’re most excited about with environmental dashboard, is the community voices section where we’re taking images, and messages drawn from community members and displaying them to the community. So the feedback is not just about telling you how much resources you’re consuming but it’s about asking you, ‘what are you doing, what are you thinking? How you think the world should be in the future?’ And so, when we take the voices of children and images of children, we find that they have a particularly powerful resonance with the rest of the community.

CURWOOD: Alright, let’s click on ‘community voices’. So here’s a kid at Prospect School. What does he say?

PETERSEN: ‘When we went to Plum Creek, we measured dissolved oxygen. There needs to be oxygen so, just like us, fish and other organisms can breathe’.

PETERSEN: You know, that’s probably a kid that’s not spent a whole lot of time at Plum Creek, our little stream, before. He goes down there, he makes this sort of realization about something that’s important to organisms in the world. And then we find a way to put that up on a screen and celebrate that realization.

CURWOOD: Here’s Lillian, fourth grader at the Prospect School.

PETERSEN: ‘I love gardening because you don’t have to go to the store to buy stuff. You just pick it and eat it’.

CURWOOD: I’m with Lillian.

PETERSEN: [LAUGHS] So am I.

CURWOOD: How do you hope people will use the dashboard?

PETERSEN: Well, our goal ultimately is to change people’s thinking and behavior. But when we think about behavior change, we not interested in just people turning off lights, but we’re interested in helping people to understand their decisions in the context of the community. So we’re just as interested in having people think about how they are interacting with other community members, how they’re voting in local elections. We want them to think about all of those things as they relate to resource use. But when people look at the dashboard, immediately what we’re most interested in is engaging them. So we need to engage, educate, motivate and empower them to make decisions in their lives which are consistent with the kinds of changes we need to make to bring about a more sustainable relationship between humans and the rest of the natural world.

CURWOOD: Jon Petersen is Professor of Environmental Studies at Oberlin College. Thanks for taking the time today, Jon.

PETERSEN: It’s been my pleasure. Thank you so much, Steve.

Related link:

Oberlin Environmental Dashboard

[MUSIC: Booker T & The MG’s “Melting Pot” from Melting Pot (Stax Records 1983)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the folks who admire some creatures many love to hate. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Lee Thompson Ska Orchestra: Hot Reggae from The Benevolence Of Sister Mary Ignatius]

Science Note- Cicadas Meet Citizen Science

A live seventeen-year cicada (Photo: Holly Menninger)

CURWOOD: It's Living On Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Just ahead, a race to discover some of the tiniest animals. But first, this note on emerging science from Erin Weeks.

WEEKS: They’ve got blood red eyes, translucent, orange-veined wings, and they’re in frenzied pursuit of mates. Seventeen-year cicadas are buzzing up and down the east coast, and as their season comes to a close, they leave behind billions of large, smelly corpses.

A team of scientists at North Carolina State University is taking advantage of their deaths to test a theory - and they want help. They’ve asked folks in cicada hotspots to collect the dead insects and mail them to their lab in Raleigh.

A collection of dead cicadas (Photo: Holly Menninger)

You see, there’s a lot you can learn about cicadas by measuring the asymmetry, or crookedness, of their bodies. In 1996, still in nymph form, this year’s brood of cicadas burrowed underground beneath trees to begin the long transformation into adulthood.

In the seventeen years since then, some forests have been replaced by roads and buildings, trapping many nymphs in the earth. Others faced stresses such as pollution and extreme temperatures. These conditions can interrupt normal insect development - and cause bugs to grow a little bit off-kilter.

To gauge just how much urbanization impacts cicadas, the NCSU team wants to measure these lopsided quirks in wing, vein, and leg sizes and compare specimens from rural, suburban, and urban locations.

So, if you live in the cicada zone, you too can contribute a few bodies in the name of citizen science. Happy hunting!

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Erin Weeks.

CURWOOD: There's more about the cicada project at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- To learn more about how you can participate, visit http://www.yourwildlife.org/projects/urban-buzz/.

- Radiolab’s Cicada Tracker shows where they’re most abundant

"Trash"Animals

Prairie dogs are considered a threat to livestock in the Midwest because of the holes they dig across pastures. Yet the story that livestock will break their legs falling into prairie dog burrows seems to be largely myth. (Photo: Big Stock Photo).

CURWOOD: So, the seventeen-year cicadas may be leaving behind their smelly corpses like so much trash as they complete their life-cycle, but there are some people who regard whole categories of animals as ‘trash’. Dave Johnson is an instructional designer at the Institute for Learning and Teaching at Colorado State University and he helped edit a book called Trash Animals: Nature’s Filthy, Feral, Invasive and Unwanted Species. He says he became fascinated with these creatures after he started catching one of America’s least desired fish.

Dave Johnson, co-editor of Trash Animals, fishes for much despised carp. Carp are a well-known “trash” fish because of they thrive in polluted waters. (Photo: Dave Johnson)

JOHNSON: I was interested in trash animals, because I had been clerking in a fly shop, and fly fishing is all about trout. And I went out to fly fish for White Bass. And so I hooked probably about a 15-pound carp, which is much bigger than any White Bass that I had ever caught. Wherever I moved, I would always look for places that potentially had carp. And the reactions I got from other anglers - they were either very angry that carp were even in those waters, or they would dismiss it outright as some kind of lunatic activity.

CURWOOD: On catching carp, did you keep them and eat them?

Dave Johnson, co-editor of Trash Animals, holds up his prize carp of the day. Few people eat carp because it takes a long time to prepare properly, and tends to have a muddy flavor. (Photo: Dave Johnson)

JOHNSON: I did once. The one day I caught a nice sized carp, about 22-pounds, just north of Fort Collins here and my daughter was with me. And she said, ‘dad, can we take this fish home and eat it?’ And then I said, ‘well, at this point I sort of feel obligated.’ And so, I have a book that explains step-by-step how to clean them. I worked on one side of the carp and it took me 45 minutes, which is a lot longer than it takes to prepare any other kind of fish. And so I then flipped the carp over because I was impatient and filleted it just as I would any other fish. And we went inside and we cooked the one side that we had prepared properly, and it was fine - it almost tasted like catfish. And we prepared the other side, and it stank up the house for three days.

CURWOOD: [CHUCKLES] Oh my.

JOHNSON: I almost thought about throwing the pan away. And that’s the interesting thing about the history of carp introduction. Just within about 10 or 15 years, people had decided that it was a big mistake because of the flavor of the fish.

CURWOOD: ‘Trash’ is a powerful word in our language. As a verb, it means to be violent. And also you can use it as a perjorative to refer to people. I mean, there’s trailer trash, white trash.

JOHNSON: A trash animal has everything to do with the way humans value other species. So the first mention of a trash animal in print, comes from a document, and it was introduced to parliament in 1749. It was called the Wealth of Great Britain in the Ocean. And one of their assessors noted that the Dutch had three kinds of marked herring, two were valuable, and the last was called ‘trash’. So the way people have been valuing animals, whether it has to do with economics, whether it has to do with aesthetics, whether they just think they’re pretty or desirable, for anglers, whether or not they fight or jump, we tend to make these categories for animals, and one category is a trash animal.

CURWOOD: Of course in nature, there’s no such thing as trash. It’s just a resource that’s being used by whatever is going to use it next. But us humans, we have this concept of trash.

Sea gull is a common term for the 28 species of gull that thrive in North America. By lumping all the species together, Trash Animals argues that we overlook what makes these birds unique. (Photo: Big Stock Photo)

JOHNSON: And it’s largely cultural. My co-editor and I, we use this term, as we say in the book, as a tool for analysis. It’s a way to really think about the way we treat animals. Because if we do have so-called trash animals, then we are not only assigning them value, but we’re also thinking about ways that we’re going to act toward those animals. We’re thinking about ways that policy might be enforced.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about the different animals that made it into your book. Everything from gulls to wolves, prairie dogs and pigeons of course. For example, how did the Canada goose become a trash animal?

The Canada goose, widely considered a “trash” animal, was once used to as a decoy for hunters to lure larger game. This encouraged the animal to become a permanent resident, rather than the migrant it once was. (Photo: Big Stock Photo)

JOHNSON: This is a really interesting story. And Bernie Quetchenbach’s essay in the book is one of my favorite. I mean, it tells a story of a time in the early 20th century when migratory Canada geese, had almost become extinct, probably due to habitat loss because we were draining wetlands at the time, and probably also due to hunting. So there was a massive public relations campaign where any farmer, basically anybody could go and get Canada geese and they could raise them in their backyards, and then release them into the wild. And this was going to save the population. But what happened through this process, is these people who were raising geese and releasing them were actually changing their behavior.

CURWOOD: So, this is a native species here in the United States, the Canada goose, and because people successfully kept it from the brink of extinction we consider it trash.

JOHNSON: Yes, because there are too many. I’ve even heard of Canada geese referred to as sky carp. So we still have migratory Canada geese, but we have to distinguish between those geese, and the geese that visit our golf courses and our city parks - the ones that never really go anywhere. If they do migrate, it’s across town.

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about coyotes and prairie dogs. I mean, those are native to North America, and yet they are in your trash animal anthology as well. Why is that?

JOHNSON: The way that humans have changed the landscape has either been detrimental for prairie dogs or it has helped the coyote. In regards to prairie dogs, there’s a lot of mythology. I grew up in rural Texas, in part of a ranching family. And even though we don’t have prairie dogs in Texas, I’d always heard that prairie dog holes were dangerous because horses or cattle could break their legs on them. Although when I asked my uncle who drives all over the west hauling cattle if he had ever seen this happen, he had to admit to me, no he hadn’t, he had just heard the stories. So in that respect, there’s a story about prairie dogs competing with humans - in that case it’s the raising of livestock or keeping of horses. Coyotes, because we eradicated wolves, we helped increase their range and numbers all over the United States. It’s easy to kill animals that to us have no value. Even those that I knew growing up who would go out and kill as many coyotes as they could, they still had respect for other species. And so, the way humans value animals determines to a large degree how we treat them. And it seems like an obvious statement, but the contradictions are also kind of interesting because on one hand we don’t feel bad at all about killing a bunch of coyotes, but on the other hand if someone were to shoot my mother’s cattle, everyone would be angry about this.

CURWOOD: As a kid growing up, you probably shot a lot of coyotes. How do you feel about that now?

JOHNSON: I feel awfully guilty about it. So at the time we were calling up coyotes with a caller, and shooting them - we were thinking that we were protecting our cattle. When in reality, we weren’t helping ourselves out at all because a female coyote can triple her litter sizes within a generation or two if the pack is threatened. So by killing a few coyotes, we were only making this perceived problem worse.

CURWOOD: You know, I suppose from the perspective of the animals, with seven billion people, there are too many people. Maybe we’re trash.

JOHNSON: A lot of the qualities of the animals that we call trash, have a lot of the qualities that humans have. Humans invade new spaces. We tend to change the landscape, we make the landscape suit us. And that often crowds out other species. We outcompete them. If those species compete with us for resources, we either use what we call management campaigns, or we eradicate them.

CURWOOD: What risks does humanity take on for itself by considering certain other species as trash, stuff to be gotten rid of violently if necessary?

Merely using the word trash to refer to animals suggests that humans want to cast out or throw away these generalized animals. (Photo: Big Stock Photo)

JOHNSON: There is a human perspective involved here that sort of determines your values about some species. So an urban environmentalist, probably white, probably middle class, thinks that reintroducing wolves to Yellowstone and seeing them thrive is a really good idea. There’s a rancher out there who leases property next to Yellowstone, who is thinking this is a threat to my cattle and my way of life. It’s a threat to me personally.

CURWOOD: What do you hope people will take away from this book?

JOHNSON: I really hope they’ll question their own values about animals. Again, the thing about trash animals is that it comes back to this idea that humans are placing value on species. And one of the things we wanted to get at in the collection, was to have people really think about this. You know, where do these values come from? And sometimes knowing a little bit of the history of the animal, how it got here, or where it came from, or whether it’s native or invasive, knowing something about the animal’s biology, you can start to develop an appreciation for the animal, start to see it in a new way. And we thought maybe if people can do that, they can question these values, they can question the whole idea of having a trash animal in the first place.

CURWOOD: David Johnson is an Instructional Designer at the Institute for Learning and Teaching at Colorado State University and co-editor of a book called Trash Animals. Thanks so much for taking the time with us, Dave.

JOHNSON: You’re very welcome. It was a pleasure to be here.

Related link:

Trash Animals

[MUSIC: Cloud Nine “20/20 (Mad Dog Mix) from Millenium (Acid Jazz records 2013)]

Chasing Springtails

(United States Department of Agriculture)

CURWOOD: Like them or not, our whole web of life depends, ultimately, on the broad and amazing variety of organisms on this planet, including many science has yet to identify. And among those unrecorded millions of life forms are some that inhabit a peculiar branch of the evolutionary tree that reporter Ari Daniel Shapiro recently had the chance to encounter.

SHAPIRO: Usually it’s easy for Louis Deharveng to step outside onto the back doorstep of his lab in Paris, and find the tiny creatures he’s dedicated his life to.

DEHARVENG: Yeah, yeah, there are many, many.

[RUSTLING LEAVES]

SHAPIRO: But today, outside his lab at the National Museum of Natural History, after rooting around in a pile of leaves...

DEHARVENG: Hmmm...usually they are here.

SHAPIRO: He can’t find any. It’s no big deal. It’s just too hot and dry. They’ll be back. So we head inside the lab. Deharveng brings me over to his microscope, and he pours the contents of a small container into a glass dish.

DEHARVENG: OK, we can have a look.

SHAPIRO: He brings the specimen into focus. I gaze down the twin barrels of the microscope.

SHAPIRO: Oh, wow. It’s...

DEHARVENG: Yellow, black.

SHAPIRO: Yeah, yellow and black, curved on itself.

SHAPIRO: It’s got six little legs, a pair of antennae, and it looks like a tiny shrimp or insect.

Springtails get their name from the tail like structure that allows them to spring or jump. (Wikimedia Commons)

DEHARVENG: It was an insect until a few years ago.

SHAPIRO: Meaning that it used to be classified as an insect. Then, around 2000, some DNA work was done on these tiny animals, and they were all re-categorized.

DEHARVENG: It’s not an insect, it’s not a crustacea. It’s a collembola.

SHAPIRO: A massive reclassification like this is common for things like bacteria. But for animals – it’s exceedingly rare. The collembola also go by a more common name – springtails – because a lot of them have a tail-like limb that allows them to spring. To jump.

DEHARVENG: Many collembola have the jumping apparatus, and they can jump many times their own size. And they jump!

SHAPIRO: The feature, though, that really makes a collembola a collembola – is something called a ventral tube. A collembola uses its ventral tube to suck up water, and to attach itself to the ground.

Now, Deharveng hasn’t always been a collembola devotee. When he began his studies as a scientist over 30 years ago, he wanted to focus on beetles. But he couldn’t find anyone who’d supervise a beetle project. So instead, he turned to a mentor who happened to have an interest in collembola. And soon, because so little was known about them, he was hooked.

DEHARVENG: It’s the pleasure to find new things outside in your environment.

SHAPIRO: Is it like looking for little treasures?

DEHARVENG: Yes, we expect to find something but we don’t know what we shall find.

SHAPIRO: Over the last several decades, scientists – including Deharveng – have continuously turned up new kinds of collembola. Right now, there are about 8,000 documented species, and there’s no sign of things leveling off. Collembola are everywhere.

DEHARVENG: They are able to adapt to any kind of habitats. They live from the tropics to the coldest place on Earth – they are in the Antarctic. From the deep caves to the canopy of the trees.

SHAPIRO: Deharveng’s traveled the world in search of collembola. He figures he’s named hundreds of species, and a handful of them have been named after him. Tetracanthella Deharvengi, Gnathisotoma Deharveng i, Paleonura louisi.

And over the years, Louis Deharveng’s seen certain types of collembola fall on hard times. His early work focused on a group of species that used to thrive on a permanent patch of snow in the Pyrenees Mountains between Spain and France. But as the temperature’s gotten warmer, the snow now melts in the summer.

DEHARVENG: I was studying something disappearing under our eyes.

SHAPIRO: More recently, he’s investigated collembola species that live on a single limestone hill in Vietnam and nowhere else. Now that hill’s being blown apart to make concrete, and he’s worried these collembola may well be headed to extinction.

Wherever Deharveng travels, collembola are an important part of a tiny food web of insects and spiders. But he admits that most people have no reason to care about them.

DEHARVENG: They are absolutely devoid of any economical interest. It’s like that.

SHAPIRO: There’s gotta be something that, that matters to you. You’re very passionate about them.

DEHARVENG: Yeah. I don’t like places where there is too much competition. I think competition is not a good way of life. The good way of life is solidarity.

SHAPIRO: Deharveng offered to show me what he meant by solidarity – by introducing me to the people he mentors in his lab. His team comes from all over the world – just like his collembola.

JANION: I’m Charline Janion. I’m from South Africa.

POTAPOV: My name is Mikhael in Russian...Potapov.

XIN: My name is Sun Xin, and I come from China.

BEDOS: My name is Anne Bedos. I work together with Louis about collembola also and different project.

SHAPIRO: I came to visit Deharveng’s lab late in the day. And when I left in the early evening, everyone was still there, working away. Not because they had to, but because they wanted to. People intent on understanding something small about our world, gathered together by a man who cares as much about making a family out of his lab here in Paris as he does about the creatures they all study together.

For Living on Earth. I’m Ari Daniel Shapiro.

CURWOOD: Our story on springtails is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Atlantic Public Media with support from the Encyclopedia of Life.

Related link:

One Species at a Time

[MUSIC: Brad Mehldau “Always returning” from Highway Rider (Nonesuch records 2010)]

CURWOOD: On the next Living on Earth, what's happening under the earth in Bayou Corne, Louisiana.

GREGOIRE: Come home to check on the house and see that everything was ok and I noticed there were bubbles in the yard. You could feel the pressure of the bubbles coming out of the ground. It’s nerve-racking.

CURWOOD: The perils of living with a massive sinkhole. That's next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Poncie Rutsch, Erin Weeks, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

You can find us anytime at LOE.org. And check out our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies, and more. Stonyfield, working to produce healthy food for a healthy planet. Stonyfield.com. Support also comes from you our listeners, The Go Forward Fund and the Town Creek Foundation.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth