January 24, 2014

Air Date: January 24, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Not Enough Rare Earths

View the page for this story

Renewable energy technologies like wind and solar are on the rise around the world, but they depend on a group of metals called rare earths, that are in short supply. Science writer Nicola Jones talks with host Steve Curwood about the scarcity of rare earths and how it could inhibit green energy expansion. (06:30)

Oil Train Danger

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

There are not enough pipelines to carry all the oil being produced in North Dakota to refineries. Much of the oil now travels by train, but carriers aren't required to warn communities that oil trains are traveling through. As Ashley Ahearn reports, recent accidents have lawmakers in the northwest planning to introduce regulations. (03:50)

Explosive Oil Trains

View the page for this story

In the past year a number of explosive oil train derailments, including the deadly accident in Lac-Megantic in Quebec that killed 47 people, have raised important questions about how we transport oil in North America. Canadian journalist Jacquie McNish has written extensively about oil trains, and tells host Steve Curwood how we got here. (14:00)

New Research Probes BP Oil Disaster

/ David LevinView the page for this story

5 million barrels of oil spewed into the Gulf when BP's Macondo well exploded in 2010, and some remained suspended in the water. New research in Hamburg Germany is examining why the oil behaved like this, as David Levin reports. (07:45)

BirdNote

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Above the sun-baked beaches of the Hawaiian islands, glistening white Tropicbirds float, with their long tail feathers streaming out behind them, as Mary McCann reports in today's BirdNote?. (01:55)

Beyond the Headlines – Roadkill Science

View the page for this story

In a trip beyond the headlines today, Peter Dykstra of Dailyclimate.org and Environmental Health News, ehn.org, and host Steve Curwood discuss Citizen Science with road-kill and the anniversary of the dramatic Santa Barbara oil spill that helped spur environmental consciousness in the United States. (05:30)

Mother of Medicine Tree

/ Ari DanielView the page for this story

On the Pacific island of Palau, the modern world rubs shoulders with the traditional, and as the inhabitants eat a more Western diet, they often develop diabetes. But a traditional tree that grows there, known as the mother of medicine tree, promises a treatment, as Ari Daniel reports. (05:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Nicola Jones, Jacquie McNish, Peter Dykstra

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, David Levin, Ari Daniel, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Oil trains are crisscrossing North America, carrying massive amounts of crude from booming areas in North Dakota to refineries. There have been numerous accidents, and people are starting to ask why these trains aren't safer.

MCNISH: They basically created a new pipeline on the rails through the backdoor, and nobody stopped them. Nobody said you can't do this. Nobody said you have to take extra security measures. I mean we all have to look at ourselves and say, how did this happen?

CURWOOD: Now state legislators are pushing bills to force oil and rail companies to tell local residents how much oil is travelling though and when.

FARRELL: It's going to be a really hard bill to push. Whenever we are taking on interest groups, particularly the oil industry, it's really hard to win.

CURWOOD: We'll have that, gliding with tropic birds and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Not Enough Rare Earths

Rare earth minerals (photo: London Commodity Markets, Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. At the recent economic summit in Davos, Switzerland, business leaders and delegates spent a day discussing a pressing issue - the economic costs of climate change. This follows on the leak of the latest UN climate report, which warns that countries have dragged their feet so long to tackle emissions that the costs of containing the damage have escalated dramatically.

Emissions are still rising rapidly, yet the alternative energy industry is also growing both in the United States and around the world. Still, many say the new energy sector is not growing fast enough to make much of a difference, and continuing fossil fuel subsidies and high upfront costs contribute to the delay. But there's another factor: the scarcity of what are called rare earths. Science writer Nicola Jones recently wrote a report for Yale's E360 on the importance of rare earths, and why they're in short supply.

Neodymium is a crucial metal for many batteries used to store energy (photo: TopQuark, Creative Commons 2.0)

JONES: Rare earths is a little bit of a misnomer. They’re not necessarily rare. Basically it’s just a group of elements on the periodic table, and they’re elements that have specific chemical properties that turn out to be very useful in certain renewable energy technologies.

CURWOOD: Why are they so critical?

JONES: For a lot of reasons, but for example, if you want to make really, really strong magnets, one way is to take iron, and then add a little tiny dose of some of these rare earths, and those rare earths help the iron to express their magnetic properties in the best way possible. So you can make much, much, much, much stronger magnets using these rare earths than without them.

CURWOOD: What’s the name of the rare earth that likes to make iron a stronger magnet?

JONES: That particular one is neodymium. They all have quite strange names, you’ve probably never heard of most of them before.

CURWOOD: For example?

JONES: Some of the others are things like scandium, yttrium, lanthanum, europium, ytterbium, erbium.

CURWOOD: OK. Great names, huh?

JONES: [LAUGHS] Great names. It’s at the bottom of the periodic table where you don’t normally get to in your high school classes.

CURWOOD: So what’s going on? Why is there a shortage of these, and they’re largely metals if they end in ium.

The majority of the world’s rare earths are mined in China (photo: US Dept. of the Interior)

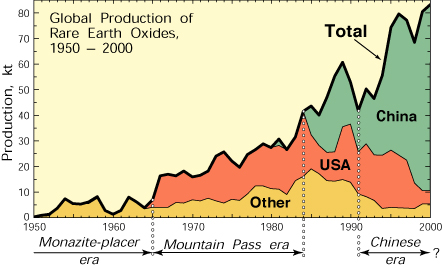

JONES: These are metals, and the problem is both geological and geopolitical. So some of them are physically quite rare. So something like tellerium for example, it makes up only about .000001% of the Earth’s crust, which makes it about three times rarer than gold. Other things, it’s just a supply issue. So, for example, most rare earths, about 97% of them right now are mined in China, and a few years ago China clamped down on trade of these rare earths out to other countries like Japan, and obviously that caused a huge supply issue.

CURWOOD: What impact is the shortage having on the renewables industry?

JONES: Well, I mean, so it makes rare earths very expensive, and that makes some of the renewable things that we’d like to build quite expensive. So, for example, if you’re trying to make a wind turbine, you can make a wind turbine using a gear box, and not using necessarily so many rare earths, and this is an affordable thing to do, and obviously many people make wind turbines. But the gear boxes are quite fragile on these things and often break, so sometimes when you’re driving past a wind farm, you’ll see a couple of them aren’t working, and that’s usually why. So I spoke to someone who said you can make a very good wind turbine without a gear box, but you need a lot of rare earths to do that. That makes a very, very expensive wind turbine, and people just can’t afford to do that right now.

CURWOOD: What does a rare earth do for the wind turbine, by the way?

JONES: Well, again, it’s the neodymium that’s used in the magnets. So things like gear boxes and motors all have magnets in them to help the electricity be converted into mechanical energy.

CURWOOD: I think it’s kind of ironic that all these renewable energy sources depend on mining of these rare earths.

JONES: Sure, everything we make has to come from somewhere. You need stuff to make stuff, and that’s pretty much true for everything regardless of what it is that you’re making. So, mining is a perpetual issue, I think, that will always be true for mankind.

Nicola Jones (photo: Nicola Jones)

CURWOOD: What are the solutions here?

JONES: So there’s a number of different solutions that people are trying to pursue. So, Alex King, for example, he’s the Director of the new Critical Materials Institute in Iowa, and that institute was founded to try to solve some of these problems, not just the rare earths, but other elements that they consider critical for the same sorts of reasons. And they’re pursuing a number of different solutions. One solution is to try and find or encourage different resources. So there’s lots of different places that could be mining things like rare earths in the world, for example. So those mines are being encouraged to come online.

CURWOOD: Yes, we recently heard the possibility of rare earth mining in Greenland.

JONES: So Alex King told me there are about 450 different possible mines around the world that people are looking into. Two of them are very advanced, one is in California, one’s in Australia. They’re actually online producing rare earths now, and they’re helping to pull some of the control away from China. But, yes, Greenland as well. Greenland’s really interesting because Greenland’s losing some of its glacial ice, which means the people there are getting more interested in mining and also forestry.

CURWOOD: Now, what about the prospect of recycling these materials?

JONES: The recycling is obviously a very good idea. Right now, a lot of former electronics, which is where a lot of the stuff is found, is just thrown away, it ends up in landfill. Something like 10 percent of our e-waste is recycled, and less than one percent of the rare earths is actually recycled. The problem is just the economics of it, although there might be more rare earths in your iPhone than there are in a rock somewhere, it’s very difficult to get it out.

CURWOOD: Now, what about just doing without, phasing these out, making technology that doesn’t require this stuff?

JONES: Sure, and people are trying to do that, particularly with magnets. Again, people are trying to make very strong magnets that don’t need rare earths, or at least don’t need the very expensive, very rare of the rare earths, or need less of them. Those efforts, I think, will succeed in small amounts. There are efforts to try and make magnets without any rare earths at all, and I think that’s a very demanding task, I’m not sure that’s going to happen.

CURWOOD: Well, one could cool the magnets down, the colder something is, the better it conducts.

JONES: Sure, but how are you going to cool things? That requires other things, like maybe helium, liquid helium, and helium is running out. You know, there’s lots of things on the planet that are in scarce supply, or expensive for us to get. So it’s always a matter of trying to balance all these different concerns.

CURWOOD: Nicola Jones is a science journalist who writes for Nature and Yale E360. Thanks for joining us, Nicola.

JONES: You're welcome. Thanks for having me.

Related link:

Read Nicola Jones’ story about rare earths at E360

Oil Train Danger

North American Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) Member Robert Sumwalt views damaged rail cars on scene of BNSF train accident in Casselton, N.D. (photo: NTSB)

CURWOOD: Well, one substance that's not in short supply in the American Midwest is oil. The booming Bakken fields of North Dakota have created a glut that's looking for ways to move to refineries. There's not enough pipelines, so that's led in turn to a huge increase in the number of trains carrying oil across North America. And there have been several spectacular oil train accidents since the boom began, including one last July in Quebec that cost the lives of 47 people. These accidents have prompted calls for regulations to improve the safety of oil trains and better protect the communities the trains traverse. From the public media collaborative EarthFix, Ashley Ahearn reports.

AHEARN: The train that exploded in Quebec in July was carrying oil from the Bakken oil fields. So was the train that derailed and exploded in Alabama last November‚ and the train that exploded just before New Year's in North Dakota.

Two Washington refineries are handling Bakken oil, with several more terminals in the permitting process. In Oregon, at least one site is receiving trains of Bakken oil. But state agencies in the Northwest aren't getting the information they need to prepare for an oil train accident. Oil and rail companies aren't required to tell state officials how much oil is on the move and what kind of oil it is. Nor do they have to reveal the details of their emergency response plans.

GILLES: They've got their own geographic response strategies put in place for their rail lines that they haven't shared with the folks here in Oregon.

AHEARN: Bruce Gilles is the spills manager for the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality. He's in the same boat as Dale Jensen, who handles spill response for the Washington Department of Ecology.

JENSEN: There's certainly that concern that we don't know exactly what's in their plan and what their response strategies are.

AHEARN: Jensen says that in Washington, oil refineries have worked with state agencies to prepare for an oil spill on the water, but there's an information gap when it comes to rail. BNSF Railway declined to be interviewed for this story but a spokesperson emailed responses to questions. The spokesperson said the company trains personnel and local officials to respond to spills of hazardous materials. BNSF Railway is investing in new equipment along the Columbia River and in Klamath Falls.

Another issue is the rail cars. Companies don't have to tell state agencies what kinds of rail cars they're using to move the oil. Jensen says he's been told that in Washington oil companies are moving their product in what are called DOT-111A cars.

JENSEN: It's the highest level of safety of the rail cars that are being manufactured right now so that's good news for us here in Washington.

AHEARN: But is it? DOT-111As are the same kind of cars that exploded in Quebec. A federal board sounded the alarm on these cars in a report they released more than 20 years ago. The report found that the DOT-111A rail cars were about twice as likely to be punctured and release their contents as other tank cars tested.

EarthFix reporter, Ashley Ahearn (photo: Ashley Ahearn)

And the design of the DOT-111As has not substantially changed, according to a spokesperson from the National Transportation Safety Board. Federal agencies are in the process of upgrading tank car standards. In the meantime, the DOT-111As are rolling through cities and towns in Washington and Oregon. But politicians are taking note.

FARRELL: Fundamentally communities have a right to know when a substance that potentially is very dangerous is coming through the community.

AHEARN: Jessyn Farrell is a state Representative from Washington's 46th district. She's introducing new legislation this session that will require oil and rail companies to regularly update state agencies about oil train routes and quantities of oil moving through the region. She knows it won't be an easy sell in the state legislature.

FARRELL: It's going to be a really hard bill to push. Whenever we are taking on interest groups, particularly the oil industry, it's really hard to win.

AHEARN: Oregon Congressman Peter DeFazio has called for a hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives about oil train risks.

I'm Ashley Ahearn in Seattle.

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for EarthFix. Anthony Schick contributed to this story.

Related link:

Check out more of Ashley’s story’s on the EarthFix website

[MUSIC: Nas “Life’s a Bitch” from Illmantic (Columbia Records 1994)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how the North American rail oil shipping boom began, and why unless something is done there are more accidents waiting to happen. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Crusaders: “Southern Comfort from Southern Comfort (Verve Music Group 1974)]

Explosive Oil Trains

Oil train making the return trip to North Dakota for more Bakken oil (photo: Roy Luck, Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The US Secretary of Transportation, Anthony Fox, has called for the rail and oil industry to make voluntary changes aimed at preventing accidents. On January 16 Fox said industry executives have agreed to cooperate and will implement changes within the next thirty days, given the epidemic of disastrous accidents that has recently plagued North America. The immediate measures will likely include slowing the trains down and making risk assessments where trains pass through densely populated areas.

The litany of recent oil train disasters is long. Let me remind you of a couple: on December 30, a crude oil train went off the tracks near Casselton, North Dakota, exploding in a ball of flame and spilling 400,000 gallons of crude oil onto the plains. And last July’s catastrophic oil train derailment in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec set off fires visible from space and killed 47 people. Joining us now is Jacquie McNish. She’s a senior writer with the Globe and Mail in Toronto and has been covering the issue throughout the past year.

A fireball from the Lac-Megantic train derailment (photo: Public Herald, Creative Commons 2.0)

MCNISH: This is a story of a boom, a black gold rush in North Dakota of crude oil that had no other place to go. There were no pipelines, they started putting it on trucks, and then in 2009, a couple of folks in North Dakota, a couple of producers and shippers came up with an idea of moving it on the rails. And you will recall all the debate and all the fury that continues today over the pipelines...well, while everyone was focusing on pipelines, this quiet migration of oil shifted to the railways, a century-old infrastructure and cars that were designed for passengers, drygoods and lumber. We went from 4,000 tank cars of oil in 2009 to 400,000 tank cars in November.

CURWOOD: Where is all this Bakken shale oil going?

Lac-Megantic the day after the explosion (photo: Michel Gagnon, Creative Commons 2.0)

MCNISH: Most of it is being refined in the United States. Much of it done in the southern parts of United States. Also in Canada, in a province called New Brunswick on the east coast. One of the largest refineries in Canada owned by Irving Oil actually ships the stuff across the country from North Dakota on the rails and also by ships up the Hudson River to refine it there.

CURWOOD: Am I a customer of this oil here in Boston if I go to an Irving gas station? Am I buying this Bakken shale oil?

MCNISH: That's part of it. We're all using it. It’s blended and transferred into all sorts of...whether it's heating oil, whether it's gasoline oil, whether it's motor oil, it’s being refined everywhere, and it's making its way into the market for broad use.

CURWOOD: Now, to what extent is this heavy traffic causing more derailments?

MCNISH: There’s two things happening here. One, the railways themselves – they’re centuries old. Yes, they’ve upgraded the tracks, and yes, they’ve upgraded the cars, and the axles, but this is such a huge surge that it's...you know, you have to wonder that it’s putting stress on the rails, and the interesting thing about the derailments that we’re seeing now is that most of them are occurring on what we call short lines.

The big class one railways - Burlington Northern or Canadian Pacific or Canadian National here in Canada - they take the oil out of the Bakken region, but to get it to the refineries often they have to use the regional short line railways. Lac-Mégantic, it was Montreal, Maine Railway, a very small troubled rail organization whose tracks were not up to the same levels as the tracks of the class one. In Aliceville, Alabama, they had a derailment of Bakken oil in November, it was a small short line going through a swamp. In Casselton, North Dakota, once again it was a smaller line, feeder line, before it got onto the big line.

CURWOOD: Describe for us the Aliceville, Alabama, accident?

MCNISH: Aliceville, Alabama, happened in November. This was oil from the Bakken region that originated from North Dakota, made its way across the Midwest and was traveling through Alabama in mid- November, and according to the local reports, late in the evening, some of the cars were going over...the entire train was going over a trestle, slightly raised trestle about 10 feet above the swamp... and very open space surrounded by swamp, and a couple of the cars derailed and the next thing you know there are fireballs unleashing into the air, and this train burned for three days. Now the good news about the derailment, it was just a mile or so outside of the small town of Aliceville. It was not an inhabited area, it was in a swampland area, but it's amazing looking at the pictures of the fire and of the trains themselves crumpled like an accordion of burned tankers, very much like Lac-Mégantic.

CURWOOD: How much oil was in the Aliceville derailment?

MCNISH: I don't know the exact number, but I believe it was 12 to 14 cars that derailed, and there was a lot of spillage into the swamp. It's, it's interesting how the railways respond to these things. They say, well, fortunately there was a beaver dam so it protected the oil from getting into other parts of the swamp. [LAUGHS] That was one of my favorite responses to that accident.

CURWOOD: So who are the regulators that are keeping track of the quality of the rail lines that this stuff is being transported on?

MCNISH: Well, that is a good question. You know, what we discovered both in the US and Canada is that no one publicly called for any scrutiny, any new rules, or even a review of the potential dangers posed by the largest increase in hazardous materials ever on the rails.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the oil itself. You know, when you look at some of the pictures of the accident it seems to be pretty explosive.

MCNISH: And that was how we got involved in this story. When Lac-Mégantic occurred, there was a lot of video footage because it happened in the downtown and the residents that survived and were able to run, they all turned on their cell phones and took these images, and it was...it looked like a war zone...mushroom clouds of burning oil. And if you know crude, it doesn't behave like that. You can throw a lit match into a tank of crude oil, because it’s so thick, and the chances are, it will extinguish itself because it just doesn't have a low flammability point.

This stuff exploded immediately on impact, and at first, the theory was that there were propane tanks in the town - that has been discounted. And then the industry responsible by the rail and the petroleum sector was, this was a once-in-a-lifetime accident - there was a hill, the brakes broke loose and the rail cars had nowhere to go, they crashed into each other, and punctured and exploded. So that was the narrative. And then we had Aliceville, Alabama, happen, and if you look at the pictures and you lay them side-by-side, the sort of accordion of burning tank cars, and again, mushroom clouds... Casselton, the same thing. So something is going on here, and initially people would say they're focusing on improving the security and the emergency response of the trains. Now they’re actually looking at the oil itself.

CURWOOD: What about the properties of the oil? Is it somehow more volatile?

MCNISH: I wish I could say I knew a lot about it, but the sad fact is, is that no one’s really taken a hard look at it. We went to Newtown, North Dakota, and you look at this oil and it looks like honey in a mason jar. It's very light, and the light qualities are part of the story here. The other story is what are the other elements? And one of the elements that people started to look at in 2010 at a joint government and industry think tank was hydrogen sulfide. Now hydrogen sulfide does exist in all oils, but in this particular oil - it’s called a sweet light crude and that's why it's prized, easy to refine, not so much sulfide you have to remove, but if you talk to geologists and scientists they say inevitably sulfides do creep into sweet light oil, and so we wonder and we can only wonder because no one’s actually studied this, you know, are we seeing this light sweet oil become contaminated four or five years into this gold rush, has it become a problem? And the reason it's a more of a particular problem for light oil is it if you transport this stuff and if there's heat or if there are disturbances you can start to see the oil actually stratify and begin the refining itself in the tank car, which means you're producing gases that are highly combustible on impact or if they don’t vent properly.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think the chemicals involved in the fracking process of the oil might be part of the problem?

MCNISH: That is at this point only a theory. We do know that that the oil producers in the fracking process use benzene and other chemicals to help remove the oil that’s locked into the shale below the surface. They will tell you that it’s only minute amounts that are used of benzene and other chemicals, so it’s inconceivable to them that it would be a problem. We also know from the first emergency responders at Lac-Mégantic that there was a lot of benzene - pools of benzene, they described - pooling outside the area where the trains derailed after the fire had been doused so that you know it’s hard to understand why there would be so much benzene. Was it a chemical reaction after the fires? Was there an excess amount in those tank cars? These are all good questions. There's no, there's no solid scientific proof or testing to prove it one way or another, and, you know, clearly there is a need to ask that question in a much more thorough scientific manner.

CURWOOD: So it may well be that relatively volatile, indeed, explosive materials were going through all these towns along the rail lines. To what extent are folks informed that this stuff is coming through and what say do they have about it coming through?

A North Dakota oilrig. (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

MCNISH: That’s a very good question, and I find it fascinating as a journalist that everyone is so focused on Keystone and all for legitimate reasons. And people will talk about the corruption of the Boreal forests in western Canada where they are planning to put part of the pipeline, but no one is thinking about these pipelines of oil that are moving to their communities. Railways were built before many towns were built, so as a result the railways travel right through the center of most towns and cities, and people seem to not be focused on the potential dangers. In the wake of these accidents they are paying attention. You're seeing more communities having standoffs with the railways, asking for information. Communities are now talking about getting some sort of 24 hour notice. What the railway will say, and what the government will say is that they're very careful about any information they provide. They’re worried about terrorism and other risks, so there's a lot of push and pull here to get better information and more coordination. We’re not there yet. A lot of the railways, particularly in Canada, constitutionally have more rights than the communities. They get to decide when and how they push the trains through. That's causing a lot of friction. There’s so many trains now in parts of Canada, particularly in the oil districts, where you have to wait 20 minutes to get from one part of town to another. It can be a small town of 400 people, but there’s nothing you can do, the train will go when it wants to go.

CURWOOD: Which of these towns is mounting a fairly active protest?

MCNISH: We have Calgary, Alberta, it’s the largest city in the Midwest of Canada, and they have had a couple of derailments and a couple of standoffs with the Canadian Pacific Railway, one of our largest railways, and they seem to be working out a healthier dialogue right now. There is a conference taking place next month in Calgary, citizens' action group holding a discussion on the safety of oil and other hazardous materials on the rail, so people are starting to think more more of this. And the interesting thing is there is still a lot of inertia...there was a deadly ethanol explosion in Illinois in 2009 that killed some people that were waiting in their cars - the fires immediately killed those people - and as early as 2009, the regulators after investigating this were recommending studier cars.

In the absence of pipelines, trains have become a primary transportation option for North American crude oil. (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

18 of those tankers were punctured in that derailment, unleashing a fiery ethanol explosion, and the industry -- the regulators calling for some time for upgraded double-walled tank cars that have shields on both sides to help prevent puncturing when there is a derailment, and better venting so if there are gases they can get out. And the shippers actually own these tank cars, not the railways. The railways just carry them. The shippers have pushed back on a lot of that, and now we’re seeing in the wake of Lac-Mégantic and these accidents, more initiative, even the Railway Association of the United States has issued a public statement in November saying that they favor conversion to the secure cars.

CURWOOD: So how has the string of oil train accidents had an impact on the pipeline debate, both in Canada and here in the United States?

MCNISH: I think people have ignored this, they have ignored it because they basically created a new pipeline on the rails through the back door and nobody stopped them. Nobody said you can't do this, nobody said you have to take extra security measures, and people just stood there watching these large black trains of oil go by their communities without asking questions. I mean, we all have to look at ourselves and say how did this happen? Why didn't anyone intervene? We didn't do it as citizens and our government certainly didn't raise any questions or increase their scrutiny.

CURWOOD: In view of the danger of these oil train accidents, how do you think that affects the argument of the necessity to get off of fossil fuels?

Jacquie McNish (photo: Globe and Mail)

MCNISH: That's a big question. That’s a big geopolitical question. I think that in this case, in this story, the story of North Dakota oil and all that oil going on the trains, there was a geopolitical economic imperative, that imperative was the United States is dependent on oil, and suddenly this little place called North Dakota is rapidly becoming the largest producer of oil in the United States. It’s now number two behind Texas, and by 2015 the US is destined to be oil independent. What government is going to stand in the way of that? What consumers are going to give up driving their cars to work for the jobs that they need? I mean it’s a very complicated question, our dependency on fossil fuels. I think a more reasonable manageable way of approaching this is, what are we doing to ensure safety? Not enough.

One of the things that was very revealing about the investigation that we did is that the US Federal Transportation Department was doing what they called the Bakken blitz - they were investigating complaints about the corrosive nature of the Bakken oil that was corroding the cars, leading to some puncturing, lots of complaints about something was wrong with this oil. That was two months before the Lac-Mégantic accident. Did they do anything about it? No. They are doing a lot more now because there's been this tragedy and there’s 47 people dead. At a baseline, we could be a lot smarter about how we transport this stuff.

CURWOOD: Jacquie McNish is a senior writer with the Globe and Mail in Toronto. Thanks so much, Jacquie, for taking the time.

MCNISH: Thank you.

Related link:

Read more about oil trains from Jaquie McNish at the Globe and Mail

[MUSIC: Paul Butterfield Blues band “Two Trains Running” from East-West (Elektra Records 1966)]

New Research Probes BP Oil Disaster

USF researchers Steve Murawski (left) and David Hollander (right) stand in front of a high-pressure chamber at the Hamburg University of Technology, where Karen Malone (center) tests oil from the Deepwater Horizon spill. Scientists like Malone are using pressure chambers like this one to recreate the conditions at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico where the spill played out. (photo: Sherryl Gilbert, University of South Florida College of Marine Science.)

CURWOOD: Well, not all the oil we use comes from onshore sources. We still get plenty from deep under the seabed, which can also lead to disasters, such as the catastrophic blowout of BP's Macondo well in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. That well spewed some five million barrels of oil into the Gulf over three months. Some was recovered, but much remained suspended in the water, and scientists have been struggling to understand exactly why the oil behaved this way. One collaboration of chemists, engineers and biologists is called C-IMAGE, which stands for the Center for Integrated Modeling and Analysis of the Gulf Ecosystem. David Levin has been following their work, and his latest report takes him to Germany.

[WATER SLOSHING IN HAMBURG CANAL]

LEVIN: For more than a thousand years, life here in Hamburg, Germany has revolved around water. This riverside city is one of Europe’s biggest ports, and it’s full of canals like this one—a narrow channel tucked behind ornate 16th century buildings.

The sun sets over the Elbe River, a major waterway that runs through downtown Hamburg. The river, which empties into the North Sea about 70 miles northwest of the city, has made Hamburg one of the busiest ports in Europe for more than 1000 years. (photo: Sherryl Gilbert, University of South Florida College of Marine Science.)

The waterfront is a hotspot for tourists, who flock here to take pictures. But in a lab across town, a group of scientists is focused on waters half a world away, in the Gulf of Mexico.

During the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill, five million barrels of oil dumped into the Gulf from a broken well on the ocean floor, more than a mile down. Most scientists thought that oil would float right up—but the strange thing is, not all of it made it to the surface.

MURAWSKI: A substantial fraction of that oil rose up to a certain level in the ocean and stayed there in these large plumes. So we need to understand what factors actually contributed to that.

LEVIN: Steve Murawski is an oceanographer at the University of South Florida. He’s here in Germany to meet with an international team of researchers who are studying the spill.

Murawski says that during the blowout, oil didn’t just drift up from the well—it sprayed out, like an aerosol can. Clouds of oil droplets formed, and they stayed suspended at different depths in the ocean. Those clouds spread toxic chemicals into the water. They killed off plankton and other tiny creatures, which had a big impact on animals all the way up the food chain, from fish to whales.

In this image, one of two high-pressure chambers run by the Hamburg University of Technology undergoes regular maintenance. When fully pressurized, the chamber can simulate conditions at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, more than a mile below the surface. (photo: Sherryl Gilbert, University of South Florida College of Marine Science.)

Exactly how the clouds formed is still unclear. That’s what Michael Schluter is trying to find out. He says the answer may lie in the oil droplets themselves.

SCHLUTER: Exactly. Everything starts with these tiny little droplets. And this initial droplet size affects the whole distribution of oil in the ocean.

LEVIN: Schluter is a researcher at the Hamburg University of Technology. He’s working with Murawski’s team to learn how oil travels through the water during a deep water blowout. At the wellhead, he says, it can shoot out at tremendous speeds…

SCHLUTER: …but after a certain distance, just a few meters, the momentum that pushes the oil and gas out of the well is gone, it's dissipated, and then we have just the bubbles and the droplets that are rising by their buoyancy.

LEVIN: As the oil droplets float upwards, they form a chaotic, swirling column. They break apart. Then glom back together. Chemicals like benzene and gases like methane bubble out and dissolve into the water. As the droplets change in size, some of them slow down, break off from the column, and float away, creating those huge oily clouds underwater. Or so the researchers think.

MURAWSKI: Nobody was able to accurately sample the particle size a mile down, so we don’t actually know what it was.

LEVIN: Again, Steve Murawski.

MURAWSKI: We’re trying to figure out if in fact the physics and chemistry of this oil, coming up at a very high rate of speed, was sufficient to create subsurface plumes of small droplets.

LEVIN: To do that, Murawski says you need to track the individual droplets of oil, and watch what happens to them as they rise. Doing that in the field is nearly impossible. During the Deepwater Horizon spill, just getting down to the well was a big challenge—let alone following tiny bits of oil around. So instead, you have to recreate the spill… inside the lab. That’s where Schluter comes in. He and his team are building a miniature version of the blowout inside a pressure chamber here in Hamburg.

[FOOTSTEPS, CLANKING]

SCHLUTER: Here we are. Let’s take a look inside… careful…

[HISSING]

LEVIN: Schluter leads me into a huge metal shipping container, where a web of hissing pipes run into a four-foot tall cylinder. It’s a tank made of two-inch thick steel, and it’s wrapped in black foam insulation. It looks like the hot water heater in my basement. But inside, Schluter’s recreating the conditions at the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, where the water pressure is more than two thousand pounds per square inch, and temperatures hover just above freezing.

MALONE: So I now set pressure, and I will start the pump.

[PUMP STARTS UP]

LEVIN: PhD student Karen Malone starts pumping water into the tank. When it reaches the right pressure, she’ll ease a steady flow of oil though a narrow tube, to see what happens to the droplets.

Standing next to a tank like this feels like standing next to a bomb—with so much pressure inside, even a minor leak could be catastrophic.

MALONE: Well… [LAUGHS] it looks like a really small cylinder, but there’s very big power inside. If you click the wrong button at the wrong time, then maybe I blow up at least myself, and maybe half the building.

LEVIN: An accident that dramatic is unlikely—there are lots of safety measures in place, and Malone knows the pressure lab well. But there’s still an element of danger. Steve Murawski says those hazards come with the territory. High pressure experiments like this one are the only way to tell what really happens in deepwater blowouts.

MURAWSKI: You know, theoretically, we could let another well blow out and test this, but the world is sick of oil spills, so creating an oil spill in a laboratory is the next best thing.

LEVIN: Schluter and Malone are recording the oil droplets in the tank using a high-speed camera. They’ve measured their size. How they form. How they break apart and join back together. And how their speed changes in the process. They’ve also recorded what happens to the methane gas that bubbles out of the oil.

On some of the droplets, it actually forms an icy crust called a methane hydrate. It looks kind of like snow, and can affect how the oil moves.

SCHLUTER: You can imagine, if you have a hard shell around a flexible surface like a bubble or droplet, then the behavior, and also the rising velocity is totally different than for a bubble or droplet without this hard shell.

LEVIN: In other words, it slows the droplets down, so they take longer to rise. And if they take longer to rise, they’re more likely to be caught in ocean currents before they make it to the surface, and spread throughout the Gulf.

The experiments in Hamburg are still in their early stages, but Schluter is convinced that to understand the big picture, you have to start small.

SCHLUTER: Even if you were going to the largest scales in nature, everything starts at these tiny dimensions. And it's always very important first to know what happens at these tiny dimensions to know how the oil is distributed in the environment.

LEVIN: So what is it like for you to kind of think about something so small that you're studying, affecting something so huge?

SCHLUTER: Uhhh…

LEVIN: Do you ever think about that?

SCHLUTER: No, never. That's nature! [LAUGHS] …

LEVIN: He isn’t philosophical about his work. It’s measurements and data that make Schluter tick—which is good, because in the coming months, Steve Murawski and his team plan to use his measurements to build a computer model of the oil. Once they know what happens as it comes out of a well, they’ll be able to predict where the oil go, and how it’ll move through the ocean.

So here in Hamburg, more than five thousand miles away from the Gulf of Mexico, this simulated blowout could help scientists react to real blowouts—which could happen not just in the Gulf, but in the waters off Brazil, Nigeria, and other countries building deepwater wells.

For Living On Earth, I’m David Levin in Hamburg, Germany.

CURWOOD: David's story was supported by a grant through the C-IMAGE consortium.

Related link:

Listen to more stories about the Gulf oil spill from David Levin

[MUSIC: Radiohead “Jigsaw Falling Into Place” from In Rainbows (Xurbia Xendless Ltd 2007)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...how a tree traditionally used to make tea on the Pacific island of Palau might hold the key to curing a modern medical scourge - diabetes. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[CUTAWAY: Giles Peterson/Gap Mangione: “Boys With Toys” from Gilles Peterson Digs America Vol.2 (Ubiquity Records 2007)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

BirdNote

White-tailed Tropicbird (Photo: Budak)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[BIRD NOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: And now let's head to the sun-soaked beaches of Hawaii for today's BirdNote®.

Here's Mary McCann.

MCCANN: "Tropicbird." The name alone evokes a warm breeze and a place where green islands dot a shimmering blue ocean.

[MUSIC: “Aloha Wau la Oe” by P. Cosma. Performed by the Ho’opi’i Brothers, from “Aloha From Maui”: Mountain Apple Company: 1999]

MCCANN: Picture a streamlined, sparkling white seabird, with a red spear of a bill and luxuriantly long tail-streamers. With the strong, direct flight of a falcon, a tropicbird can catch a flying fish on the wing, or plunge like an arrow into the sea and—with its serrated bill—capture a squid.

Red-tailed Tropicbird in flight (Photo: Matt Knoth)

[RED-TAILED TROPICBIRD VOCALS]

MCCANN: Birds of such elegant natural design seem creatures of myth. And in fact, their scientific name links directly to Greek mythology, as tropicbirds belong to the genus Phaeton. Phaeton, the son of Apollo, hurtled through the sky in the chariot of the sun, only to plunge into the River Eridanus.

Myth, sun, and sea – there’s that warm ocean breeze again.

[MUSIC: “Aloha Wau la Oe” by P. Cosma. Performed by the Ho’opi’i Brothers, from “Aloha From Maui”: Mountain Apple Company: 1999]

Red-tailed Tropicbird (Photo: Scott Henderson)

Maybe it’s time for a trip to Hawaii. Visit the island of Kauai, and you can easily see one of these near-mythical birds, its glistening white form floating in the air just beyond a sea cliff’s edge. Tropicbirds have ranged through most of the tropical latitudes of the world’s oceans for 60 million years.

I’m Mary McCann

CURWOOD: There are photos of these gliding Tropicbirds at our website, LOE.org.

[Written by Bob Sundstrom

Call of the Red-tailed Tropicbird provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by C. Robbins.

“Aloha Wau la Oe” by P. Cosma. Performed by the Ho’opi’i Brothers, from “Aloha From Maui”: Mountain Apple Company: 1999.

Ambient waves by Kessler Productions.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org January 2014 Narrator: Mary McCann]

Related links:

- Check out this episode of BirdNote on their website

- Read more about tropicbirds

[MUSIC CONTINUES]

Beyond the Headlines – Roadkill Science

Dr. Splatt is using roadkill for science (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Back to Earth and reality now. On the line from Conyers, Georgia, and ready to peer beyond headlines, we have Peter Dykstra, who publishes the Daily Climate.org and Environmental Health News, EHN.org.

CURWOOD: Hi there, Peter!

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve.

CURWOOD: So what have you got this week?

DYKSTRA : Let’s take a trip into user-friendly science-land, participatory science, citizen science...start off with Phenology, and when you mention Phenology, you have to start with a disclaimer because it’s different than Phrenology, with an “r” in it, that’s the highly-respected science of telling someone’s fortune by reading the bumps on their head.

CURWOOD: And, of course, you have a very smooth scalp, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, I appreciate that, Steve, but Phenology, without the “r”, is the study of how plants and wildlife are impacted by climate changes and other habitat changes. There’s a recent study from my alma mater, Boston University, they went out to Walden Pond, and they compared the current plant life there to what Henry David Thoreau saw at Walden 150 years ago. They reported that today, plants bloom, on average, 18 days earlier than they did for Thoreau, and the warmer temperatures we have now are helping to bring in non-native species and crowd out the native species that he saw.

CURWOOD: And this affects almost everything. Consider the huge impacts on moose populations.

DYKSTRA: That’s right, there’s a big problem with moose, from coast to coast, as cold climates get a little warmer. Another example is in Vermont. The maple syrup industry there, the climate is going to be too warm for maple trees over the next few decades. The tree-tappers won’t be able to work there. The trees are actually slowly migrating north in to Canada. And one more example, here in Georgia, armadillos...we never used to see armadillos here around the Atlanta area, they were no farther north than the Gulf Coast of Texas. There’s one study that says as the climate warms, the country may be warm enough to sustain armadillo populations as far north as Washington, DC, and Omaha, Nebraska.

CURWOOD: Yes, and what about things such as fire ants and certain ticks?

DYKSTRA: Well, you've got the non-cuddly species too. It’s not all good news, but phenology is a participatory science, and people can join in, they can collecting data on how soon the flowers bloom in the spring, how soon the leaves turn in the fall, and any new wildlife you’re seeing or old wildlife you don’t see anymore. The USA National Phenology Network website keeps track of this, and listeners can tap in there and report their phenology news.

CURWOOD: And you can get a link to the USA Phenology Network at our website, at LOE.org. And you’ve got another example of citizen science, I understand.

DYKSTRA: Yes, this is a guy who’s been a citizen science hero for a couple of decades, who goes by the name of Doctor Splatt. His real name is Brewster Bartlett, a science teacher at Pinkerton Academy in New Hampshire. He’s the sole proprietor of Dr. Splatt’s roadkill project.

Go back to 1993, he was building an online network; science students came in from across the country who reported back to Dr. Splatt on the roadkill that they saw alongside the highway, or maybe under the tires of their school bus. It sounds a little gruesome, but it’s not just a body count, there’s useful data in all of this. The students from Dr. Splatt learned about how warm weather can increase roadkill. Wildlife gets a little bit more active in the springtime, or when warm early. More importantly, it’s been a really successful way to get kids to pay attention to our interactions with wildlife even if these kinds of interactions are pretty messy.

CURWOOD: And online since 1993? I would think that makes him some sort of an online pioneer as well?

DYKSTRA: Absolutely. He was into the internet early, and it’s been a big success. He‘s slowing down a little bit with the project, but Doctor Splatt says he still loves to teach, he still loves to talk about those “road pizzas”, that’s what he calls the road kill they study.

CURWOOD: And Peter, what do you have on the anniversary calendar for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, we’re going to have one of the two catastrophies that helped to bring the American environmental movement together in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. One of them, of course, was when the Cuyahoga River was so polluted that it caught fire and burned. But 45 years ago this week, off of Santa Barbara, California, there was a Union Oil company drilling platform that blew out 35 miles of beach around Santa Barbara. It was covered with oil. Seabirds, seals, dolphins other wildlife covered with oil and it was a disaster that played out on TV news across the nation.

The Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 (photo: USGS, public domain)

CURWOOD: So these weren’t just big environmental accidents, but accidents on view in our living rooms.

DYKSTRA: That’s right, but remember that’s a different era. A lot of us don’t have TVs in the living room that we watch all the time anymore. When the TV’s on, it’s not on the news as often, and when the news is on, it’s not covering the environment as often. The Santa Barbara oil spill was dominant news for several days, it spurred legislative action, it made oil drilling safer, it put certain environmentally-sensitive areas off limits. This was a 200,000 gallon oil spill. But you need to compare that with something else. In 2010, the Deepwater Horizon spill was roughly two hundred million gallons, a thousand times as big.

.jpg)

The platform that blew in the Santa Barbara spill (photo: Doc Searls, Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, thanks for reminding us.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and the DailyClimate.org. And you can get links to all these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Check out the BU study about the ecology around Walden Pond

- Dr. Splatt’s Roadkill project

- Follow Peter Dykstra on Twitter

[MUSIC: Booker T “Austin City Blues from Sound The Alarm (Concord Music Group 2013)]

Mother of Medicine Tree

Dried leaves from the mother of medicine tree (photo: Ari Dan

CURWOOD: Back to the tropics now, to the Pacific archipelago of Palau. Palau is renowned as a destination for diving and snorkeling round its many reefs and wrecks and its people depend on tourism, fishing and subsistence agriculture. But there's potentially a new and exciting development in Palau, and it could be an invaluable medical Godsend. Ari Daniel brings us this report.

DANIEL: This is a story of a dangerous collision between two worlds – in a particular place and inside a particular person. And how, after that collision, those two worlds might just rescue one another.

The place is Palau, a country in the western tropical Pacific, near the Philippines. It’s made up of over 700 little islands. And the person is Christopher Kitalong.

KITALONG: My father’s from Palau. And my mom’s from New Jersey.

DANIEL: Kitalong is athletic and easy to be around. He grew up primarily in Palau, the backdrop for some of his earliest memories.

KITALONG: Most of my free time was spent, like, feeling the mud between your toes while racing through the mangrove forests, or climbing 80-foot trees, and knowing which tree you were jumping on so you knew it wasn’t poisonous.

The fruits of the mother of medicine tree (photo: Christopher Kitalong)

DANIEL: It was Kitalong’s family that helped him discover the details of his natural surroundings.

KITALONG: My father, my grandmother, my uncles showed us, the beauty of what was around us.

DANIEL: This notion of honoring what the land has to give – in terms of food and shelter, it took root in Kitalong...and it’s become more and more important to him as he’s watched this tradition...erode.

KITALONG: It’s a very rapid change from when my father was born to when I was born. People don’t connect as much with nature, it’s become a metropolitan lifestyle. So we’re totally pushed towards this society where it doesn’t stress the value of our identity as people, and what is around us.

DANIEL: This is the concern that’s given Kitalong a mission – to help his fellow Palauans find a way to embrace modern life and their traditional culture at the same time.

It’s no easy task, but Kitalong has an unexpected partner at his side – a plant that goes by the scientific name Phaleria nisidai.

[CABINET OPENS]

KITALONG: We’re looking in the family Thymelaeaceae.

DANIEL: Kitalong pulls a few dried specimens out of a cabinet at the Palau National Museum, stems of elongated leaves glued to pieces of paper. The samples come from trees that are 8 to 10 feet tall – trees that have been planted everywhere in Palau.

KITALONG: It was in our yard.

DANIEL: And in the yards of Kitalong’s relatives, his neighbors and his friends. But nobody eats the plant. Nor is it particularly decorative.

.jpg)

Inspecting the mother of medicine tree in the wild (photo: Christopher Kitalong

KITALONG: You couldn’t climb it either. So as a child, I was like, “Well, what’s the use of this tree?”

DANIEL: It turns out the answer to that question has to do with this plant’s local Palauan name:

KITALONG: Delal a kar. And that means “mother of medicine.” Just like the mother to a child, it took care of the Palauans.

DANIEL: Historically, delal a kar has been used as an energy booster and as the base in a variety of traditional medicines. Even now, as Palauans age, they often drink a tea made from the leaves of the plant. And Kitalong thinks delal a kar may continue to help his people, this time in the face of a modern medical foe – diabetes.

Two worlds – one being Palau and the other being the West, in the form of processed foods and a more sedentary lifestyle – have collided, and the result is a surge in diabetes in this part of the world.

KITALONG: It’s been declared a national emergency. So this is something that is an immediate threat to our lives.

DANIEL: There’s some preliminary evidence, though, that delal a kar – this mother of all medicines – may actually help fight diabetes. And Kitalong, who’s a PhD student at CUNY and the New York Botanical Garden, is currently organizing a clinical trial – a double blind, placebo-controlled Western clinical trial – in Palau to test it.

BALICK: Chris’s work is really path breaking in Palau.

DANIEL: This is Kitalong’s PhD advisor – Michael Balick, an ethnobotanist at the New York Botanical Garden. And he says that by demonstrating the medical importance of a plant like delal a kar, Kitalong is helping rebuild respect among Palauans for their environment.

BALICK: Going back to ancient ways – knowing in this forest what you can eat, how you can heal your wounds – gives a culture a greater sense of self-reliance and pride. And that is the antecedent to conservation.

DANIEL: Christopher Kitalong still has to run his clinical trial. And it’s not clear how responsive Palauans will be to his case of fusing old and new. But when I was in Palau, I saw Kitalong not just in the lab, but out in the community too. He relates easily to people. He speaks two languages – the language of western science and the language of traditional remedy. And he’s using his bilingual ability to reconnect Palauans with their roots.

KITALONG: You know, maybe, maybe taking a step back is the best way to move forward in health, and happiness...by promoting the fact that traditional remedies in Palau are valid. And that our culture and our knowledge from before is important to preserve.

DANIEL: Kitalong is a product of the same two worlds that have collided on Palau. He’s found a way to merge them inside himself, and he’s hoping he can help this tiny island nation do the same.

I’m Ari Daniel.

CURWOOD: Our story on the mother of medicine tree is part of the series, One Species at a Time, produced by Atlantic Public Media, with help from the Encyclopedia of Life.

Related link:

Check out more of Ari Daniel’s stories at his website

[MUSIC: Jimi Hendrix “Pali Gap” from South Saturn Delta (Sony Music 1997)]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, 3D printers could make manufacturing anything we need cheap and easy.

PEARCE: The potential good that it can do is so enormous and overwhelming. We have the potential to get to a society where we push the cost down for everything to be within the range of everybody.

CURWOOD: Not only that, we could recycle plastic and make it greener too. That's next time on Living on Earth.

CURWOOD: We leave you this week deep in a southern swamp.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS, FROGS AND THE OCCASIONAL ALLIGATOR from "Echoes of Nature" LaserLight Digital DDD 12 255 Track 6 Bayou]

CURWOOD: Birds, pig frogs, and the deep growl of an alligator greet the visitor out for a stroll in the morning mist. These digital recordings were assembled for the CD Echoes of Nature.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Clairissa Baker, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Catalina Pire-Scmidt, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stephenson Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth