January 31, 2014

Air Date: January 31, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Environmental State of the Union

View the page for this story

In the 2014 State of the Union address President Obama said climate change is real and a threat that must be dealt with. But he also pledged to continue his commitment to use multiple energy sources with a strong focus on natural gas. Host Steve Curwood discusses the President’s contradictory goals and his environmental agenda with UCLA environmental law professor Ann Carlson. (11:30)

Russia Cracks Down on Critics of Olympic Site Construction

View the page for this story

Environmental activists in Sochi, Russia have been raising serious concerns about the impact of Olympic developments on the delicate ecosystems in the North Caucasus. Journalist Alice Speri tells host Steve Curwood that the Russia government is cracking down on the protestors. (08:05)

Remembering An Afternoon WIth Pete Seeger

View the page for this story

Iconic musician and activist Pete Seeger has died at the age of 94. Living on Earth spent an afternoon with the folk music legend in 1998. Seeger told host Steve Curwood that Rachel Carson's book “Silent Spring” inspired him to environmental activism. One of Seeger’s goals was to clean up New York’s Hudson River and he helped get the sloop “Clearwater” built to spread the message about pollution. Steve Curwood met Pete Seeger at the Sloop Club on the banks of the Hudson in Beacon, New York and has this profile. (28:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Ann Carlson, Alice Speri, Pete Seeger

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: In his State of the Union address, President Obama vows to act on climate change.

OBAMA: Climate change is a fact, and when our children’s children look us in the eye and ask if we did all we could to leave them a safer, more stable world, with new sources of energy, I want us to be able to say yes, we did. [APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: Also, celebrating Pete Seeger. Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring awoke the environmental activist in him.

SEEGER: I read it in the New Yorker, in installments. Up to then, I'd thought the main job to do was help the meek inherit the earth, and still that job has got to be done, but I realized if we didn't do something soon what the meek would inherit would be a pretty poisonous place to live.

CURWOOD: Pete Seeger’s life and music and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

The Environmental State of the Union

President Obama delivering the 2014 State of Union Address. (photo: The White House)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The US Constitution requires the President from time to time to give Congress “information of the state of the union,” and until the terms of Franklin D. Roosevelt this was most often in the form of a written report. These days presidents seem to prefer speeches, and this year Mr. Obama took time to address job creation, the environment and energy.

OBAMA: Now, one of the biggest factors in bringing more jobs back is our commitment to American energy. The all-of-the-above energy strategy I announced a few years ago is working, and today, America is closer to energy independence than we have been in decades.

One of the reasons why is natural gas - if extracted safely, it’s the bridge fuel that can power our economy with less of the carbon pollution that causes climate change. Businesses plan to invest almost $100 billion in new factories that use natural gas. I’ll cut red tape to help states get those factories built, and put folks to work. And this Congress can help by putting people to work building fueling stations that shift more cars and trucks from foreign oil to American natural gas. Meanwhile my administration will keep working with the industry to sustain production and job growth while strengthening protection of our air, our water, our communities. And while we’re at it, I’ll use my authority to protect more of our pristine federal lands for future generations.

[APPLAUSE]

It’s not just oil and natural gas production that’s booming; we’re becoming a global leader in solar, too. Every four minutes, another American home or business goes solar; every panel pounded into place by a worker whose job can’t be outsourced. Let’s continue that progress with a smarter tax policy that stops giving $4 billion a year to fossil fuel industries that don’t need it, so that we can invest more in fuels of the future that do.

President Obama delivering the 2014 State of Union Address.(Photo: The White House)

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: We're listening to the environment and energy portion of President Obama's 2014 State of the Union address.

OBAMA: And even as we’ve increased energy production, we’ve partnered with businesses, builders, and local communities to reduce the energy we consume. When we rescued our automakers, for example, we worked with them to set higher fuel efficiency standards for our cars. In the coming months, I’ll build on that success by setting new standards for our trucks, so we can keep driving down oil imports and what we pay at the pump.

Taken together, our energy policy is creating jobs and leading to a cleaner, safer planet. Over the past eight years, the United States has reduced our total carbon pollution more than any other nation on Earth. But we have to act with more urgency because a changing climate is already harming western communities struggling with drought, and coastal cities dealing with floods.

That’s why I directed my administration to work with states, utilities, and others to set new standards on the amount of carbon pollution our power plants are allowed to dump into the air. The shift to a cleaner energy economy won’t happen overnight, and it will require some tough choices along the way. But the debate is settled. Climate change is a fact. And when our children’s children look us in the eye and ask if we did all we could to leave them a safer, more stable world, with new sources of energy, I want us to be able to say, yes, we did.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: President Barack Obama, delivering his 2014 State of the Union address. And here to help us unpack the President's words is Ann Carlson, Professor of Environmental Law at UCLA’s School of Law.

CARLSON: I guess two things struck me. One was the forceful way in which he made clear that climate change is no longer a controversial question scientifically. His commitment to try and do something to leave the planet in good shape for future generations struck me as a bold and very welcome statement.

On the other hand, I was also struck by his continued commitment to an all-of-the-above energy strategy, embracing natural gas and fracking actually rather clearly - he didn’t say anything about fracking but that’s the way in which natural gas is coming up out of the ground these days - so I was struck at sort of the “having it both ways” quality of the speech.

CURWOOD: You know, the President’s comments on natural gas drew a fair amount of fire from environmental activists, folks who’ve supported him a lot in the past. Let me read you a quote from an email I got from Michael Brune, who’s the Executive Director of the Sierra Club. Michael says, “Make no mistake, natural gas is a bridge to nowhere. If we are truly serious about fighting the climate crisis, we must look beyond an all-of-the-above energy policy and replace dirty fuels with clean energy.” How do you respond to that statement?

President Obama responds to applause for a wounded veteran during the 2014 State of Union Address.(photo: The White House)

CARLSON: Well, I think the President is in a bit of a bind on this question about natural gas. On the one hand, there’s no question that burning natural gas, as opposed to burning coal, is significantly less greenhouse gas intensive. On the other hand, getting the natural gas out of the ground through fracking produces greenhouse gas emissions, and there’s a big debate about whether those emissions that we’re getting through the fracking process offset the reductions that we get from burning natural gas in place of coal.

CURWOOD: Now the President actually suggested that we start converting the American auto fleet to run on natural gas, embedding natural gas into the economy deeper. What do you make of that?

CARLSON: I found that statement curious, and I was wondering whether what he really was focused on was the conversion of trucks to natural gas. There is a big move to convert trucks. A lot of companies have found that natural gas price declines are making it more cost effective to shift to natural gas engines, but so far the American auto fleet hasn’t followed suit.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, natural gas is one of the reasons that the US is seeing a drop in our total greenhouse gas emissions. And according to the President, he said the US has reduced carbon emissions more than any country in the world over the last eight years. Does that surprise you, and how do you think he got to that number?

CARLSON: Well, that doesn’t surprise me for a couple of reasons. First of all, remember that we are second to China in the total tonnage of greenhouse gas emissions that we emit. That means that in absolute numbers, reductions from the United States are likely to be larger than reductions from other countries. China is still engaged in a path and a policy of strong economic growth, so its emissions are growing, not shrinking. Other countries have seen larger percentage reductions, but the United States, again, in absolute terms has reduced its greenhouse gas emissions more than other countries.

CURWOOD: Obama did say he wants to cut subsidies for fossil fuel companies, and redirect that federal money into renewable energy sources, but I don’t know how many times I’ve heard him say that before. I mean, what kind of traction do you think the idea of cutting fossil fuel subsidies actually has in Washington DC?

CARLSON: I think it has zero traction in Washington DC. I think it’s popular politically. It’s a good sound bite to say, “We’re going to cut fossil fuel subsidies from big oil and put it into renewable energy sources”, but as you say, he’s been saying this for years. It has gone absolutely nowhere in Washington, DC.

CURWOOD: Well, now, there are some things the President can do without the cooperation from the Congress. One of them is moving forward with new, low-carbon regulations for power plants. What does that entail, and what’s the timetable for it?

CARLSON: So the Obama administration has already issued proposed rules for new power plants that will cut their greenhouse gas emissions. Those are very likely to be challenged, but those rules are in draft form right now and have been issued. The bigger thing that the Obama administration can do is to issue rules for existing power plants to cut their greenhouse gas emissions. Now those rules could be very aggressive or they could actually be pretty tepid, and we don’t know yet what they will look like, but we’ll see. He’s likely to issue those rules sometime in early summer of this year.

President Obama delivering the 2014 State of Union Address.(photo: The White House)

CURWOOD: The President said he’s going to use his executive powers for conservation on federal lands. How might he do that?

CARLSON: Well, there’s an act called the 1906 Antiquities Act that has been interpreted to give presidents very broad power to take federal lands and restrict their uses and turn them into national monuments and so forth, and virtually every president has used this power. Lots of presidents have tended to use it at the end of their terms. So President Bill Clinton established the Grand Escalante National Monument, President George W. Bush declared a very large area a national marine sanctuary, so I think we’re likely to see President Obama use that power and use it as extensively as he can.

Ann Carlson is a professor of environmental law at UCLA. (Photo: University of California at Los Angeles)

CURWOOD: The President closed this portion of his speech with some very strong words about climate change, not only noting that it’s real, but we’re going to be judged by our children and grandchildren. Ann Carlson, what do you think will be this President’s environmental legacy?

CARLSON: I think this President’s environmental legacy will be a mixed one. I think he has taken serious executive action to try to address greenhouse gas emissions, but I think it’s also fair to say it has not been his central legislative priority, and that he probably could have done more. I think it remains to be seen whether some of the actions that he can still take will burnish his legacy on climate or will limit it.

CURWOOD: Ann Carlson is a Professor of Environmental Law at UCLA’s School of Law. Thanks so much, Professor.

CARLSON: You're welcome. Nice to be with you.

[MUSIC: Daft Punk “Giorgio By Moroder” from Random Access Memories (Columbia Records 2013)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...with the Winter Olympic Games about to kick off in Sochi, Russia, troubling questions about their environmental impact, and the impacts of the authorities on environmental activists. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: King Curtis: “Big Dipper” from Soul Serenade (Synergy Records 2007 Reissue)]

Russia Cracks Down on Critics of Olympic Site Construction

Environmental activist and geologist Evgeny Vitishko (photo: Environmental Watch of the North Caucasus)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

[MUSIC: NBC OLYMPIC THEME “THE BUGLER'S DREAM”]

CURWOOD: Yes, it's that time again. The Winter Olympic Games begin on February 7 in Sochi, Russia, and they're reportedly the most expensive ever, at $51 billion. That staggering impact on the Russian treasury has sparked a lot of controversy, and there have also been protests about the environmental impact of the games. Those demonstrations have led to a harsh crackdown and the arrests of green activists. Freelance journalist Alice Speri has been covering the controversy from Russia and she explains what happened.

SPERI: So last December, just as the Russian government released members of the punk band Pussy Riot and Greenpeace activists that had been arrested, they also sentenced an environmental activist in the Sochi region to three years to a penal colony. That sentence is currently pending an appeal, so it’s not quite set yet, but the activist in question, Evgeny Vitishko is a geologist and a very active and outspoken member of the Environmental Watch of the North Caucasus, which is an activist environmentalist group in the Sochi region that’s been really critical of the games. But this is just the latest example of a long string of intimidation and harassment of activists in the area.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it, the Russian governments say that these Olympics are the greenest ever. What steps in fact have they taken?

SPERI: So Sochi organizers are really keen on projecting a green image, and they’ve detailed a long list of conservation measures they’ve taken to limit damage. For instance, they said that they have attempted to reforest some of the areas that have been destroyed in the course of Olympic construction. They brought in new plants, and they relocated a number of rare species of animals. They also pledged to compensate for their carbon footprint, and for the carbon footprint of all the athletes, and all the members of the media that will be attending Sochi. That’s quite unprecedented for an Olympic. So there have definitely been some efforts to mitigate the environmental damage, but at the same time, we have independent consultants, environmental experts, that have worked on a number of Olympics before that said that the level of environmental damage we’ve seen at Sochi is completely unprecedented.

CURWOOD: Specifically, what are some of the criticisms that the local environmental activists are making about the development that’s going on in Sochi?

SPERI: The primary concern of many activists is that in order to construct Olympic venues, the Russian government changed legislation protecting the environment in the area. So there’s a number of levels of protection, if you will, one of these is a national park, which is similar to our national parks here, in which you can only carry out very limited construction. The Russian government changed the legislation in order to be able to bring venues and roads into national parks. Most of the competitions will take place in what is the Sochi national park.

Olympic construction dumping in the area around Akhshtyr (credit: Environmental Watch of the North Caucasus)

The Russian government originally planned to construct Olympic venues in what is a UNESCO heritage site. There was a lot of international pressure and a lot of opposition to that, so they moved most venues to the nearby national park, the Sochi national park. So really the main concern of a lot of environmentalists is that this is setting a very dangerous precedent in Russia, and that because environmental concerns are not a priority when most construction takes place, the fact that this legislation has been changed will be used again in the future.

CURWOOD: Alice, describe for me the ecosystem there. What’s it like, and how is it being impacted by the Olympic development?

SPERI: Sochi was a very interesting choice for a winter Olympics venue. It is the only place in Russia that has subtropical climate, so really not quite a winter destination, and, you know, Russia has plenty of mountains and plenty of snow elsewhere. But what people were saying is that what the local authorities and Russian authorities wanted was to have ski resorts and slopes close to the coast where a lot of elites have their summer homes. The problem with that is this is an extremely unique ecosystem for Russia and a lot of that ecosystem has been destroyed in the course of Olympic construction. One of the areas that was particularly damaged is the Mzynta River Valley in the mountains. This was a completely pristine, physically untouched river valley and forest that was home to very rare animal and plant species, and some 5,000 acres of this land was completely destroyed to make room for Olympic venues. The government has promised to compensate for the damage by bringing in reforestation projects, by relocating some of the animals, but really this was an untouched environment, a unique environment that has been lost.

CURWOOD: What about the people living in the region? What’s the impact that the Olympic development is having on them?

SPERI: People in the region have been impacted in a number of ways, by Olympic construction - and this goes from huge traffic that has sort of halted the city for years - to the environmental damage itself. This has been particularly difficult for the villagers around Sochi. There is a particular one village, Akhshtyr where residents were completely cut off from transportation for five years as this large railway and road were being built to connect Olympic venues on the coast to Olympic venues in the mountains. This village was also cut off from water supplies, so a lot of people in Sochi and around Sochi have really seen not only their environment transform, but their daily lives.

More Olympic construction-related dumping in the area around Akhshtyr (photo: Human Rights Watch)

CURWOOD: How have Russia and the International Olympic Committee responded to these criticisms?

SPERI: Russian authorities do not respond very well to criticism. Early on, the Russian authorities involved, or attempted to involve, members of civil society and environmental experts in the planning process. They worked with members of the Environmental Watch of the North Caucasus, they worked with members of Greenpeace Russia, but a lot of these people ended up leaving the process disillusioned when they felt that the recommendations they made were not being implemented at all, and a lot of these people felt they were being used as part of the authorities’ attempt to greenwash the Olympics.

The International Olympic Committee has responded to criticism. They have said they are aware of the concerns in Sochi, and that they have attempted to work with Sochi organizers to make the Olympics more green. They have suggested alternatives and more sustainable options, for instance, the choice of Olympic venues. However, a lot of groups said the Olympic Committee has not done enough to uphold and protect the commitment to environmentalism that is at the heart of the Olympic charter.

CURWOOD: When you talk to the environmental activists and ask them why did they think this all happened, what do they tell you?

Olympic construction waste blamed landslides in villages around Sochi (credit: Vladimir Kimaev)

SPERI: I think a lot of people feel this is somewhat in line with the way things are going with Russia in general. A lot of people point to Putin’s latest term as President, and they say that since his return to power in 2012 there’s really been a crackdown on any critical voice. And environmentalists happen to be a particularly outspoken and particularly combative group, if you will, but they’re not the only ones. So a lot of them feel that really there just really isn’t any space for critical voices in Russia at this point for anybody that’s crossing business interests that are very much linked with political interests.

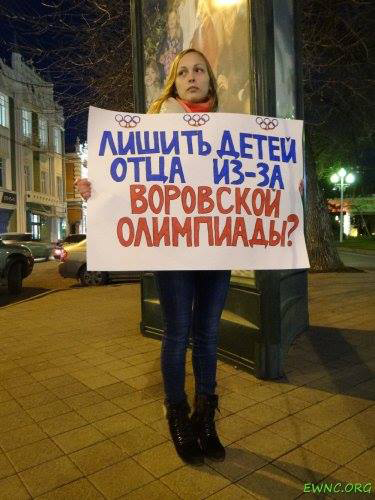

An activist protesting the sentencing of Evgeny Vitishko. Translation: "Robbing children of a father because of a corrupt Olympics?" (photo: Environmental Watch of the North Caucasus)

There is a lot of sadness actually, when you talk to these activists - a lot of them got into this line of work because they love the places they grew up in, they love the region around Sochi, and they’ve really seen it destroyed over the last few years. There isn’t a whole lot of hope, and I think there’s also a certain level of disillusionment with the way which the community, the international community, has watched this Olympics. I mean, we’ve seen critical reports, we’ve seen some investigations, but overall the spotlight on Sochi has not brought any substantial changes on the ground, and people are really worried that things will just get worse when the Olympics are over.

Alice Speri (photo: Rachel Barth)

CURWOOD: Alice Speri is a freelance journalist whose been covering the Sochi Olympic development. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

SPERI: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Check out Alice Speri's Piece in Al Jazeera

- Read more about EWNC at their Facebook page

[MUSIC: Bill Frisell “Wildwood Flower/Poem For Eva” from Solos: The Jazz Sessions (Original Spin Music 2012)]

Remembering An Afternoon WIth Pete Seeger

CURWOOD: Last week, we promised that this week we'd bring you a story about 3D printing, and its potential to turn any of us into custom manufacturers of green products. But that was before we learned of the death of one of the real heroes of the progressive environmental movement, Pete Seeger. He was the voice of a generation, a campaigner to clean up the Hudson River - and the tireless banjo-picking troubadour who championed workers and civil rights and peace.

I first met Pete Seeger when I was 7, when he inspired me to pick up the banjo and, eventually, even perform as a folk singer, as so many did. And his passionate concern to protect our planet was one of the driving forces that led me to found this radio program. Back in 1998 we heard he had an electric truck, and when we asked him about it he invited us to visit him in Beacon, New York. So today as our tribute and farewell to this extraordinary man, we present An Afternoon with Pete Seeger, the program we broadcast back then.

[RECORDED MUSIC of Pete Seeger: All music is from the original 1998 broadcast. Check transcript for selections]

[AUDIENCE CLAPPING]

SEEGER: [SINGING] I've lived all my life in this country.

I love every flower and tree.

I expect to live here till I'm 90.

It's the nukes that must go and not me.

AUDIENCE: [SINGING] It's the nukes that must go and not me.

The nukes that must go and not me.

I expect to live here till I'm 90.

It's the nukes that must go and not me.

CURWOOD: That's Pete Seeger leading a crowd in an anti-nuclear song at a Harvard University gathering back in 1980. For some in the audience, this may be the apex of their protest days. For Pete Seeger, it's another night on the town as the nation's troubadour of conscience. America's tuning fork, some call him. For more than half a century, Pete Seeger has been leading people throughout the world in song, and in the process he's become a walking history of folk music and social activism. In the 1930s and '40s, you'd find him and his famous banjo on the union picket line.

SEEGER: [STRUMMING BANJO] Now you want higher wages, let me tell you what to do.

Got to talk to the workers in the shop with you.

You got to build you a union, got to make it strong.

But if you all stick together, boys, 'twon't be long.

You get shorter hours. Better working conditions.

Vacations with pay, take the kids to the seashore...

CURWOOD: Singing songs with outspoken political views led Pete Seeger in 1955 to the House Un-American Activities Committee. Congress wanted him to testify about alleged Communist affiliations. Name names, it was called. Mr. Seeger refused, was ordered to jail, and blacklisted. An appeals court blocked his prison term, and Pete Seeger kept on singing. In the 1960s it was songs for civil rights and against the war in Vietnam.

SEEGER: [SINGING] The sergeant said, "Sir, are you sure this is the best way back to the base?" "Sergeant go on, I fought at this river about a mile above this place.

It'll be a little soggy but just keep sloggin', we'll soon be on dry ground.

We were waist deep in the big muddy, the big fool says to push on...

CURWOOD: And ever since then it's been the environment. In 1969, with the help of other musicians and activists, Pete Seeger built a sloop he christened the Clearwater, because that was his intention: to clear the waters of the Hudson River of pollution and garbage.

Pete Seeger lives on the Hudson, in a small quiet town called Beacon, about an hour north of New York City, and just 30 miles from where he was born. For decades, he and his neighbors have met on the river's banks at the Sloop Club to socialize and organize over potluck suppers. He's asked us to meet him there, where it's his turn to set up for this month's gathering.

A bright red pickup truck loaded with logs and plywood pulls up. A tall, wiry man with a white beard and glasses jumps out.

[DOOR SHUTTING]

SEEGER: Hope you haven't been waiting too long.

CURWOOD: Nope, how are you?

Pete Seeger has lived eight decades, but he moves with the ease and energy of someone who still has a lot to do.

[TO SEEGER] Mr. Seeger, you got here a Ford Ranger, except it didn't make much noise when you pulled up.

SEEGER: I bought it for $8,000. A schoolteacher who teaches electricity wanted to learn more about electric cars, so he made his own electric car. And he put into it a 28-horsepower electric motor, and 20 6-volt batteries.

CURWOOD: Can I see under the hood?

SEEGER: Sure.

[HOOD OPENS]

SEEGER: Not much here.

CURWOOD: Nope. Except a sign that says, "Caution, wear rubber gloves. You could be electrocuted." [LAUGHS]

SEEGER: Right. There's like 400 amps. For me it's perfect. I live on a very steep mountainside and I'm always carrying rocks and logs, and with a low range and 4-wheel drive I can inch up the steepest kind of slope with a ton of logs. It can go a foot a minute if I want to go that slowly, because I just feed in more or less power with the accelerator. I'd be burning out the clutch if I was using a regular gasoline car.

CURWOOD: Let's go over here by the...your dock’s here out of the water and we can chat a bit. What a place for a sunset, huh?

[WATER LAPPING ON SHORE]

SEEGER: This waterfront was a tangle of weeds, and the river was like an open sewer 30 years ago when the Clearwater started. And little by little it's gotten better. That park over there was our big victory. We petitioned and petitioned and people laughed at us, but, by gosh, the petitions finally had an effect. And a little city money and a lot of federal and state money - a million dollars to make a park out of seven and a half acres of garbage.

CURWOOD: Aha. Pete Seeger, how'd you get involved in environmental concerns?

SEEGER: It was Rachel Carson's famous book "Silent Spring." I read it in The New Yorker, in installments. Up to then, I'd thought the main job to do is help the meek inherit the Earth. And I still, that's a job that's got to be done. But I realized if we didn't do something soon, what the meek would inherit would be a pretty poisonous place to live. And so I made almost a 180-degree turn, started reading books like "The Population Bomb" by Paul Ehrlich, or "The Poverty of Power" by Barry Commoner. I'm a readaholic. And I was reading a book about the sailboats that sailed here, oh, all during the 19th century. Alexander Hamilton wrote one of the Federalist Papers on his way to Poughkeepsie in a sloop, where they were arguing whether or not to sign the Constitution idea and agree to it.

Well, I write a letter to my friend: wouldn't it be great to build a replica of one of these? Probably cost $100,000. Nobody we know has that money, but if we got 1,000 people together we could all chip in. Maybe we could hire a skilled captain to see it's run safely and the rest of us could volunteer. And three years later the sloop Clearwater was built up in Maine, and I helped sail it down with Don McLean and a batch of other singers. And now it takes school kids out. It's not a rich man's cruise boat. Two or three times a day it takes groups of 50 school kids out, teaches them what makes rivers dirty and what's got to be done to clean them up. Of course, people say what can a sailboat do? It can't do much except bring people together. But when people come together, that's when miracles happen, right?

CURWOOD: What do you think it's done for the river?

SEEGER: It drew attention to it in such a friendly way that people couldn't help getting attracted. In the little town of Cold Spring south of here, there were some very conservative people who thought it was a communist, treasonous project, because I was involved with it.

Steve & Pete share a laugh.

SEEGER: I told people at age seven I became a communist when I read about American Indians. And anthropologists, that's the term they use for the way our ancestors lived anywhere in the world. The men hunted, the women gathered berries and dug for roots and carried babies on their back. And somebody killed something to eat, the meat was shared. That's communism. I admit, it seems romantic to want to go back to that, but I really do believe that if there is a world here, if there's a human race here in 100 years, we will have learned how to share again.

CURWOOD: Indeed.

SEEGER: Well, down in this little town, a man came down to see the Clearwater, and he beckoned to me. He said, "Seeger, can I talk to you a minute?" I said, "Sure." He said, "I don't want you to think I agree with you, not one-tenth of one percent, but that sure is a beautiful boat." He couldn't take his eyes off it. [CURWOOD LAUGHS] 160-foot tall the mast goes up. I call it a symphony of curves. There are hardly any straight lines on a sailboat and very few right angles. Curves, curves.

[SINGING WHILE PLAYING GUITAR]

Sailing down my golden river.

Sun and water all my own.

Yet I was never alone.

Sun and water are all life givers.

I'll have them where'er I roam.

And I was not far from home.

SEEGER: That was the first Hudson River song I wrote. The Clearwater had not been built. I hadn’t even thought of the idea. I was sailing a little plastic boat and there I looked at the water beneath me. There was lumps of this and that floating by with the toilet paper. And the phrase of John Kenneth Galbraith came to mind. “Private affluence, public squalor.”

I had money to buy this little plastic boat. We had money to go to the moon. But we didn’t have money to keep the rivers clean. And later on, I was sailing by myself and I saw the sun go down and the sky turned from yellow, to pink, to purple, to midnight blue, and I had [SINGING] sailing down my golden river, sun and water all my own, but I was never alone.

[GUITAR STRUMMING]

CURWOOD: We’ll be back with more music and conversation from Pete Seeger in just a minute or so. So keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Pete Seeger: “One Percent Phospherous Banjo Riff” from 89 (Appleseed Entertainment 2008)]

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Back now to our Afternoon with Pete Seeger, recorded in 1988.

[GUITAR STRUMMING]

CURWOOD: Let's talk about some other songs. Garbage.

The Beacon Sloop Club has a tree growing through the roof.

In Mr. Thompson's factory they're making plastic Christmas trees.

Complete with silver tinsel and a geodesic stand.

The plastic's mixed in giant vats from some conglomeration

That's been piped from deep within the Earth or strip-mined from the land.

Well, then he went on to say and so the water gets dirty in Long Island Sound, but I changed the words: [SINGS]

And if you question anything they say why don't you see?

It's absolutely needed for the economy.

Garbage, garbage, garbage,

Their stocks and their bonds, all garbage.

What will they do when their system goes to smash?

There's no value to their cash.

There's no money to be made.

But there's a world to be repaid.

Their kids will read in history books

About financiers and other crooks,

And feudalism and slavery and nukes and all their knavery.

To history's dustbin they're consigned along with many other kinds of garbage, garbage, garbage...

You know, I drew blood with that verse? I sang it on “The Today Show” once, and Fortune magazine says, "Esso was sponsoring that program. Do they know what songs are being sung with their money?" [CURWOOD LAUGHS] And they quoted the verse I'd sung. I don't necessarily like to draw blood. I'd rather persuade people to laugh and eventually agree that maybe I've got a little right on this side.

Incidentally, the only way I got it on “The Today Show” was by -- I have to confess -- a little bit of devious preparation. I knew that NBC wouldn't be happy about me singing it. I come in at 6:30 in the morning; they say, "Pete, what are you going to sing?" I said, "Well, I've got a cheerful little banjo tune; I've got something else a little more serious." "Well, let's hear them." Played the banjo tune. "Fine, what's the other?" I sang “Garbage.” They say, "Well, Pete, it's a little early in the morning. You got something else?" I was prepared. I sang [SINGS}: Walking down death row...

They say, "Pete, you got something else?"

[SINGS] If a revolution comes to my country...

Dusk on the Hudson River, off the shores of Beacon, N.Y.

[SINGS]: Mr. Thompson starts his Cadillac,

Winds it down the freeway track,

Leaving friends and neighbors in a hydrocarbon haze.

He's joined by lots of smaller cars all sending gases to the stars,

There to form a seething cloud that hangs for 30 days.

And the sun blinks down into it with an ultraviolet tongue,

Turns it into smog, then it settles in our lungs.

Oh! Garbage, garbage garbage...

We're filling up the sky with garbage.

What will we do when there's nothing left to breathe but garbage?...

CURWOOD: You've spent a lot of time with Woody Guthrie. I'm thinking of Woody Guthrie's song “Roll On Columbia” in which he speaks in such glowing terms of the dams that are there.

SEEGER: Yeah. I think if Woody was around now, he would find some funny song. He was wonderful at combining tragedy and humor, all in one song. He did have a funny verse: Them salmon fish are pretty shrewd. They've got politicians, too. Run every four years. [CURWOOD LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: What's the most important thing when it comes to the environment?

SEEGER: I tell people, work in your local community. The world's going to be saved by people who fight for their homes. Now, there may be glamorous places to go to, far across the oceans on, but really the world's going to be saved by people who fight for their homes.

CURWOOD: Is there a song that you'd like to talk about in connection with, you know, working in your own community, working in your town, to make the environment better?

SEEGER: Well, a lot of songs are about it. [SINGS]

Inch by inch, row by row,

Gonna make this garden grow.

It's “The Garden Song,” written by a fellow up in the state of Maine, and Arlo Guthrie and I and lots of others have recorded it. I've also written a little song I sing on the general subject of praying, because I think church people and non-church people should find ways to get together. It was just about a year ago, a little over a year ago, I was out getting wood to start the morning fire. We heat our house with wood. And I look up and see the sun poking itself up over the mountain. [SINGS] Early in the morning, I first see the sun,

I'll say a little prayer for the world.

Hope all the little children live a long, long time.

Every little boy and little girl.

Hope they'll learn to laugh at the way some precious old words seem to change,

'cause that's what life is all about: to arrange and rearrange and rearrange.

And I have a little chorus: [SINGS]

Oh, whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

You get the audience singing it.

CURWOOD: Come on, you guys. [LAUGHS]

SEEGER: You'll have to help me out, next time. It's like a zipper song; anything nice that happens you can have a new verse. For me, it was ten and a half years ago, one A.M. our son-in-law Shabazz knocks on the door: "The baby's coming!" I said ‘have you called the midwife?’ "Yes, yes, she's bringing two friends."

Well, so we called up a couple friends. It was a party for three and a half hours. Our daughter beamed like she was in heaven, and on occasion she'd let out a shriek and then beam some more. And after three and a half hours her firstborn, who was six years old at the time, says, "I see the head! I see the head!" [SINGS]

Heard the first yowl of a brand new baby,

And I said a little prayer for the world.

Hope all the little children live a long, long time,

Yes every little boy and little girl. [CLAPS]

Hope they'll learn to laugh at the way some precious old words do seem to change.

'Cause that's what life is all about: to arrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Sing it with me.

BOTH: [SINGING] Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

SEEGER: [SINGS]

Well, sometimes I wake in the middle of the night

And rub my achin' old eyes.

Is that a voice from inside my head,

Or does it come down from the skies?

There's a time to laugh but there's a time to weep,

A time to make a big change: wake up, ya bum!

The time has come to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Sing it again!

BOTH: [SINGING] Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

Oh whee, oh why, to rearrange and rearrange and rearrange.

[LAUGHS]

SEEGER: I've tried to write lots of songs, but I have to admit that it's one thing to try and write a song and another thing to write one good enough for people to want to remember and sing. Woody Guthrie wrote 1,000 songs and there's maybe a dozen which will be widely sung. And a friend of mine had started a small record company, and he says, "Pete, would you be able to put out a record of some of your own songs?" I said, "My voice is gone, it's too wobbly, too raggedy.” When I stand on a stage mainly what I do is get the audience singing; I accompany them. I line out the hymn, as they say in church. But he says, "What if I get other people to sing them?" I said, "Fine, if you can find them." Well, by gosh, he got some awful well-known singers: Bruce Springsteen and Bonnie Raitt and Billy Bragg and Judy Collins and a whole lot of others, put out 2 CDs, mainly of songs that I wrote. And other songs like “We Shall Overcome.” All I did was make an arrangement of them.

SPRINGSTEEN: [SINGS] Hey, we shall overcome.

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome some day.

Darlin', here in my heart, yeah I do believe

We shall overcome some day.

Well, we'll walk hand in hand.

We'll walk hand in hand...

Pete tunes his banjo.

Well, 300 women were on strike in 1946. It was in winter and I guess on the picket line they probably had a barrel with a little fire in it, and people were warming their hands and singing old gospel songs to keep their courage up. And one woman, Lucille Simmons by name, loved this song, but she sang it, what they call long meter style. And she changed one word. "I'll" became now "we." And she sang, [SINGS SLOWLY] "We will overcome."

Now church people know how to harmonize, and the basses get the low notes and the sopranos get the high notes, and you weave in and out. And a group of people can make beautiful music just improvising with each other. It became one of their favorite strike songs: we will overcome some day.

Well, a white woman, a union organizer, Zilphia Horton by name, she learned it from the strikers, it became her favorite song. Anyway, I spread the song around the country, but I didn't have a good voice like that, those two women, so I gave it a banjo accompaniment: omm, chinka oom, chinka oom chinka omm, chinka oom, chinka oom... I got audiences in town hall and others singing it, but it didn't really spread -- until 1960, a young friend of mine, Guy Carawan by name, had a workshop called “Singing in the Movement.” And some 70 young people from Texas to Florida to Virginia gathered at that little Highlander School and swapped songs for a weekend and made up new verses and so on. And when Guy taught them this song, they said, "Oh, Guy, you got a song here!" And Guy had started giving it a kind of rhythm, which now everybody knows. It's...musicians call it 12/8 time, that is, four beats, but each four beat is divided up in three little beats...one two three, one two three, one two three, one, two, three, four...

SEEGER [CLAPPING AND SINGING WITH AN AUDIENCE]:

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome.

We shall overcome some day.

Oh, deep in my heart, I know that I do believe,

Oh we shall overcome, someday.

We shall live in peace!

We shall live in peace.

We shall live in peace.

We shall live in peace some day.

Ohhh, deep in my heart I do believe we shall overcome someday.

The whole wide world around!...

[TO CURWOOD]: Saving the world is not going to be easy. It's going to require huge arguments. People who call themselves environmentalists don't always agree. One says, "Don't have any dams," but along comes a man and says, "If you have a lot of small dams they won't do any damage, or not enough, and saves burning fossil fuels." Who knows what's going to happen?

All I know is I wish I could live another 30 or 40 years, because some of the most exciting things are going to happen. When I meet people who say, "Oh, there's no hope, Peter, look at the things that are going wrong, and those stupid people in Bosnia, there are going to be things like that all around the world, where power-hungry people says 'I know how to handle this, just give me the bomb.' There's no hope."

But I say to them, I said, "Did you think that our great Watergate president would leave office the way he did?" "No, I guess I didn't think that." I said, "Did you think that the Berlin Wall would come down so peacefully?" "No, I didn't think that would happen, yeah." I said, "Did you think Mandela would be president of South Africa?" "No, I didn't predict that." "Well, if you couldn't predict those three things, then don't be so confident that there's no hope." And I give them a bumper sticker. It says, "There's No Hope, But I May Be Wrong."

[CURWOOD LAUGHS]

[SEEGER STRUMS GUITAR]

CURWOOD: Pete Seeger, thanks so much for taking this time with us on Living on Earth today.

SEEGER: Thank you for inviting me.

CURWOOD: What's it say on your banjo here? It says...

SEEGER: "This machine surrounds hate and forces it to surrender." I hope.

[STRUMS GUITAR AND SINGS]: Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well may the world go when I'm far away.

Well may the skiers turn, the swimmers churn, the lovers burn.

Peace may the generals learn when I'm far away. [SINGS WITH OTHERS]

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[BANJO MUSIC]

Sweet may the fiddle sound, the banjo play, the old hoe-down,

Dancers swing round and round when I’m far away.

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[BANJO BRIDGE]

Fresh may the breezes blow, clear may the streams flow,

Blue above and green below when I’m far away.

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

[BANJO BRIDGE]

CURWOOD: Pete Seeger, sadly now very far away - but if the world goes well, it's at least partly thanks to his banjo, his optimism and his hard work. We bid him a very fond farewell. Thanks for everything, Pete.

SEEGER: Yes - well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

Well may the world go, the world go, the world go.

Well, may the world go when I'm far away…

Related links:

- Pete Seeger sings during 1963 Australia tour

- Pete Seeger hosts Johnny Cash & June Carter

[APPLAUSE]

[SFX RIVER FLOWING]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week on Pete Seeger's beloved Hudson River..

[SFX RIVER FLOWING]

CURWOOD: On its path to the sea, the Hudson passes Iona Island, a bird sanctuary that's part of Bear Mountain State park at Stony Point, New York. It's a popular nesting spot for bald eagles.

[SFX RIVER FLOWING]

CURWOOD: This recoding was made by Annea Lockwood for the Hudson River Museum CD, “A Sound Map of the Hudson River”.

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our afternoon with Pete Seeger was produced by Eileen Bolinsky and Jesse Wegman. Eileen also recorded and mixed the session. Naomi Arenberg, Clairissa Baker, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Catalina Pire-Schmidt, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Jennifer Marquis and Gabriela Romanow all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth