March 21, 2014

Air Date: March 21, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Power Shift - Electric Utilities Fight Rooftop Solar

View the page for this story

Solar power makes up less than one percent of the US energy output but utility companies including Northeast Utilities, a provider of power in Massachusetts, want to scale back a key incentive for homeowners to install the panels. Bryan Miller of The Alliance for Clean Energy tells host Steve Curwood that utilities want to reduce or do away with net metering, by which home owners get credit on utility bills for the electricity their solar panels generate. (06:55)

Power Shift - Big Battery Breakthrough

View the page for this story

A breakthrough in battery technology could make large-scale energy storage practical. Researchers at Harvard University say their organic flow-battery would be affordable and efficient. Professor Michael Aziz tells host Steve Curwood how the technology works and why it could significantly improve the demand for wind and solar power. (7:30) (07:30)

Power Shift- Lessons From Massachusetts Public Transit

View the page for this story

On St Patrick's Day, the smog in Paris was so bad that authorities made public transit free and banned half the cars from the roadway. Former Massachusetts Transportation Secretary Fred Salvucci tells host Steve Curwood public transit is a key way to limit congestion and reduce emissions from cars, though many cities with public transit including Boston aren’t keeping up with growing demand. (09:40)

Small Matters: Emergence

/ Ari DanielView the page for this story

Out of seemingly amorphous chaos comes order and pattern. That's the nature of Emergence, and you can see it in phenomena as diverse as flocks of birds and the structure of crystals. Ari Daniel reports. (05:35)

BirdNote ®: Vernal Equinox

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Though it seemed to many of us in the north and central US that winter would never end, spring has at last truly sprung, as Mary McCann and many birds celebrate in Birdnote®. (02:05)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

Host Steve Curwood digs beyond the news headlines with Peter Dykstra publisher of Environmental Health News, ehn dot org and the Daily Climate, and discovers how some shale developments could be guilty of over half of the deadly sins and which state believes scientific ignorance is truly bliss. (03:55)

The Extreme Life of the Sea

View the page for this story

Life in the ocean is a longstanding mystery to most humans, and even now we can travel deep beneath the waves, we've barely scratched the surface. A new book, The Extreme Life of the Sea, sheds an entertaining and informative light on some of the ocean’s oldest, oddest, fiercest and strangest creatures. Coauthor and biologist Steve Palumbi discusses the work with Steve Curwood. (11:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Bryan Miller, Michael Aziz, Fred Salvucci, Peter Dykstra, Steve Palumbi

REPORTERS: Ari Daniel, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Solar panels are sprouting on thousands of US rooftops, and utilities reward homeowners for the energy they generate. But the power companies don’t like the deal.

MILLER: It's about utilities trying to stop competition and rooftop solar is the first form of true competition that they have ever faced. Their problem with solar is that they don't own it. They don't own the sun.

CURWOOD: Also the extreme life of the sea, where strange creatures down in the dark and deep have novel ways of finding prey - like the stoplight loosejaw.

PALUMBI: It has two search lights that beam out from under its eyes and those search lights are red, and they also change their eyes so that they can see red. So they can prowl around with these search lights on and nobody else can see them, but they can see their prey.

CURWOOD: Weird life deep in the ocean and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Power Shift - Electric Utilities Fight Rooftop Solar

Rooftop solar arrays are a small but fast growing sector of the US energy portfolio. (birgstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The electric grid provides power to everyone who’s connected, and homeowners with rooftop solar can also give some power back to the grid. So when the solar panels are generating more electricity than a grid-connected house can use at that moment, net metering kicks in. The billing meter spins backwards, and homeowners get credit for what they produce. Of course, when the sun isn’t shining or household electric demand is high, the meter spins forward to show what’s owed to the power company. So net metering is a key economic incentive for individuals to invest in solar, along with rebates and tax credits. But Bryan Miller of the Alliance for Solar Choice says utility companies don’t like net metering and are now fighting back.

MILLER: Net Metering is the core policy for rooftop solar in the entire country. It is the most important policy. It ensures that people are properly credited for the power that their solar systems produce.

CURWOOD: So what are the reactions that you see when it comes to net metering?

MILLER: The utility companies don’t like solar, period. And net metering is their preferred way lately of trying to stop solar. There’s no better example of this than the piece of legislation that just died in Washington State, where utilities literally tried to write a law that said they were the only ones legally able to provide solar in the state. So that’s just a very clear example of what the fight’s about. It's about utilities trying to stop competition and rooftop solar is the first form of true competition that they have ever faced.

CURWOOD: Now, the utilities would say, look, if we are providing wires to these devices, we ought to make some money on it...they’re costing us money. What do you say to those arguments?

MILLER: Well, they do make money. Rooftop solar customers continue to pay for power when they buy it, but the utilities’ position seems to be that people should buy power whether they need it or not. Let me just give you an analogy. A lot of homeowners these days are switching to natural gas appliances and natural gas heating because of the low price of natural gas. We don’t hear utilities complaining about that at all, and that’s far more disruptive in terms of the amount of power that’s migrating to a different source right now. Of course, the reason utilities aren’t complaining about that at all is they own the natural gas as well. Their problem with solar is that they don’t own it. They don't own the sun. So that’s what this fight is about and policymakers are going to recognize that the utilities have changes that they have to accommodate all the time, but that’s not an excuse to stop competition.

CURWOOD: Well, tell me about a couple of specific battles that you’re seeing across the country. What’s going on in the northeastern part of the United States about Canadian hydropower?

MILLER: Well, I think what’s going on in the northeastern United States is the utilities are trying to build billions of dollars of transmission through environmentally sensitive lands to import, in this case, foreign hydropower from Canada. And the utilities want to do that because if they get to build those billions of dollars of transmission lines, they’ll make more money. So at the same time they’re trying to build that transmission line, they’re launching an attack against rooftop solar and net metering specifically because they know that rooftop solar helps avoid the cost and undermines the argument for those expensive transmission lines.

CURWOOD: Now, this debate has a life of its own in sunny Arizona. What’s going on there?

MILLER: Arizona’s a very strange story. It has been revealed that the largest utility in the state, APS, or Arizona Public Service, has actually been lobbying to increase property taxes on rooftop solar customers. A senior member of the Republican leadership in the legislature has confirmed that as well as the governor’s office. APS continues to deny that despite the fact that there’s these highly placed Republican officials who are saying that APS has lobbied them for a tax increase on rooftop solar.

CURWOOD: There have even been some presidential campaign-like attack ads airing in Arizona. Let’s have a listen to this one put out by the utility.

[MUSIC AND VOICES FROM AD]

WOMAN: We’ve seen this before.

OBAMA: The true engine of economic growth will always been companies like Solyndra.

WOMAN: Connected companies getting corporate welfare. Now, California’s new Solyndras, Sunrun and SolarCity are getting rich on hardworking Arizonans. Out-of-state billionaires using your hard-earned dollars to subsidize their wealthy customers. It’s not right. We don’t need this California-style corporate welfare in Arizona.

MILLER: Not a word of that ad is true, and the utilities at first actually denied that they funded that ad and many others like it. And after months of denials, eventually were caught funneling money through what we call “dark money organizations” that don’t disclose the source of their donations.

Net metering is the system by which utilities keep track of how much energy is produced by an individual rooftop solar array. It’s crucial to the economic viability of residential solar production. (bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: I suppose anyone opposing solar power would want to use dark money.

MILLER: [LAUGHS] They certainly don’t want to do it in the sunlight. That’s definitely true.

CURWOOD: As solar companies fight back, you have an unexpected advocate. Barry Goldwater, Jr. is on this particular ad I want you to listen to now.

GOLDWATER: Conservatives want no, they demand, freedom of choice, whether it’s healthcare, education, or even energy. We can’t let solar energy be driven aside by monopolies who want to limit that choice. It’s not the American way. It’s not the conservative way.

MILLER: The reason conservatives support solar so much is because it’s competition, and the idea that conservatives should be told that they have to purchase power from a regulated monopoly and not have the option for competition is exceptionally offensive to conservatives. And so that’s why we see rooftop solar just polling far higher in popular support than any other form of energy.

CURWOOD: How large is the percentage of the American electric supply that’s solar at this point?

MILLER: It’s small. It’s less than one percent. And so when utilities launch these really over-the-top attacks like the ones that you have played, it is a very strange situation for them to try to explain why they can’t even tolerate a small amount of competition. It’s small, but on the other hand, it’s growing. It grew about 60 percent last year. The rate of employment growth in the rooftop solar industry was ten times the national average last year. We expect that number to grow rapidly over the coming decade.

CURWOOD: Bryan Miller, come on, you work for a major solar installation company. Obviously you really like this stuff.

MILLER: I do. I actually used to work for the largest utility in the country as well, and I’m certainly proud to be on this side of these issues. There’s no question that people of good faith on both sides have legitimate disagreements, but we should have an open and honest fair conversation. Reasonable people on both sides can agree to disagree on some things, but the utilities should stop the political attacks.

CURWOOD: Bryan Miller is Vice President for Public Policy and Power Markets for Sunrun, a solar solutions company headquartered in San Francisco. Bryan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MILLER: You're welcome. Thank you for having me.

NOTE: A spokesman for Northeast Utilities declined to comment on Bryan Miller's claims that Northeast and other power companies are attacking net metering for consumer-owned solar power arrays.

Related links:

- Alliance for Solar Choice

- Sunrun

- Arizona Public Service

- Northeast Utilities

Power Shift - Big Battery Breakthrough

HARVARD’S FLOW-BATTERY TEAM. Clockwise, from left: Dr. Changwon Suh, Prof. Roy G. Gordon, Dr. Brian Huskinson, Dr. Suleyman Er, Dr. Michael Marshak, Prof. Alán Aspuru-Guzik, Prof. Michael J. Aziz, Michael Gerhardt, and Lauren Hartle. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

CURWOOD: Well, even if your home or business is solar-powered, come the evening you have to buy electricity or use very expensive batteries to keep the lights on. And utilities with large scale solar and wind farms also have to manage these intermittent power sources, and much of power from the always-on nuclear and coal plants goes to waste at night because demand is low and it’s too expensive to store the energy. But now some Harvard researchers have made a major breakthrough in developing cheap batteries that could store massive amounts of electricity. Michael Aziz of Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences is one of the project leaders, and he came into the studio. Professor Aziz, welcome to Living on Earth.

AZIZ: Thank you. It’s a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Now, your team has created what’s called this organic megaflow battery, but before you tell us what that means, first of all, just outline what are the problems for conventional batteries for renewable energy sources.

Professor Michael Aziz in his organic flow-battery laboratory. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

AZIZ: Sure. The two most important measures of the capability of a battery are the amount of energy in can store, and that’s measured in kilowatt-hours. That’s what you pay for in your electric bill, how much energy you’re using. And the rate at which you can deliver that energy out of storage, and that’s the power measured in kilowatts. The ratio of energy to power is very different for different applications, and traditional batteries are very limited in the range of that ratio they can come up with. So, for example, have you ever had a car that wouldn’t start, and you cranked and cranked the starter until the battery died?

CURWOOD: Ummm...it’s that time of year.

AZIZ: Well, the battery lasts maybe ten minutes, 15 minutes, until it’s drained. That ratio of energy to power is the number of hours you can discharge your battery at full power until it’s drained. It turns out for storing wind and solar, you need many hours to days, and there’s no traditional battery that can do that inexpensively.

CURWOOD: In other words, the fundamental problem here, is that you need batteries that can last for a long, long time, and today’s batteries aren’t designed to do that.

AZIZ: That’s right.

Organic mega-flow battery in the Harvard SEAS lab. (Photo by Eliza Grinnell, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

CURWOOD: So, your team has created what’s called organic megaflow batteries. What exactly does that mean? Organic...is that good for you to eat?

AZIZ: Turns out that the molecules we’re using are very, very close to a molecule found in rhubarb. The chemicals are in your green vegetables...you eat them every day. The flow battery is a different concept.

CURWOOD: What is a flow battery?

AZIZ: The flow battery is different from a traditional solid electrode battery because it stores the energy outside the battery container itself in storage tanks full of fluids. It’s a lot like a fuel cell. In a fuel cell you store the energy outside the fuel cell itself, for a fuel cell car it would be hydrogen and air. When you want electricity, you flow those chemicals into the cell past the electrodes where they’re converted to low energy chemicals and they give off the energy in the form of electricity, and you exhaust the low energy product. But for a flow battery, you can’t exhaust the product, you’ve got to contain them so when it’s time to charge up the battery, you flow those product chemicals back into the cell, drive in electricity and convert those chemicals back to the original high energy chemicals that you started with. Now you have a battery.

CURWOOD: So a flow battery...it could be any size that you want. If you store the energy in a tank separate from where the electrodes come together, the bigger the tank, the more energy you could store.

AZIZ: That’s exactly right. You can design the electrodes to give you the power you need, and then you can get arbitrarily large amounts of energy by just bigger and bigger tanks full of chemicals, and that’s potentially a much cheaper way of storing large amounts of energy than stacking up entire banks of solid electrode batteries.

CURWOOD: So there are a few flow batteries already operating out there, large-scale electric plants as I understand it. How correct is that?

AZIZ: That’s right. There’s several different flow battery chemistries that are being developed. The most commercially advanced stores energy in the form of Vanadium ions in an aqueous solution, and the problem with that is Vanadium is a rare and expensive metal.

(Photo: Eliza Grinnell, Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences)

CURWOOD: But you don’t use Vanadium. You use something that, well, you find in food.

AZIZ: As a matter of fact, I noticed that other groups were making progress on designing fuel cells using organics, and so we started looking around for organic molecules that might work well in a flow battery. We noticed this class of molecules in chlorophyll called quinones. When they’re in chlorophyll during photosynthesis, they switch back and forth between oxidized and reduced forms over and over again without any sign of degradation, and that’s exactly the functionality we want in a battery. So we modified them to make them highly soluble in water, and put them in a flow battery, and it works. Performance is terrific. After half a year at this, the performance is rivaling that of Vanadium. We haven’t had a chance to optimize anything yet, so we think that we have a lot of room for improvement ahead of us.

CURWOOD: So, part of your secret sauce is that you’re imitating nature.

AZIZ: That’s right. We find that nature has learned how to do things really well, and in this case going between oxidized and reduced states over and over again without degrading is something nature figured out how to do in order to make photosynthesis work so we’ve adopted that now in a battery.

CURWOOD: So these quinones are really abundant...you can find it in rhubarb, huh?

AZIZ: There’s a quinone in rhubarb that is so, so close to the molecules that we actually have in our first quinone flow battery that some people are calling it a rhubarb battery. Right now what we have comes from crude oil because it’s very cheap and the most important thing is to get storage to be cheap or else it can’t be useful. Ultimately, if we can get it out of rhubarb that would be an extra bonus.

CURWOOD: What would this look like, say, installed in my basement to support home solar cells?

AZIZ: It would be a power conversion unit that would look like an electrical machine, and it would be hooked up to two storage tanks, one for the positive electrolyte and one for the negative electrolyte. Separating the positive and negative that way is a safety feature of flow batteries that you can’t get in solid electrode batteries like lithium ion. There, the positive and negative are all mixed together in the same cell.

CURWOOD: So the two tanks makes it safer?

AZIZ: The two tanks make it safer because the chemicals can’t all mix together at once and give you a catastrophic discharge like you can get in lithium ion batteries for example.

CURWOOD: And these two tanks would be no bigger than, say, a typical oil tank or something?

AZIZ: That’s right. For a typical set of solar panels on your rooftop, you’d have two tanks, the total volume of which would be the size of one home heating oil storage tank in the basement.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you feel your development could really revolutionize our use of solar and wind power?

AZIZ: The way I see it, the biggest problem in us getting most of our electricity from the wind and the sun is their intermittency. We need a battery that can safely and cost-effectively store large amounts of electric energy, and this has a fighting change of being able to do that.

CURWOOD: Michael Aziz is Professor of Materials and Energy Technologies at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Thanks so much for coming by.

AZIZ: My pleasure.

Related links:

- Nature Magazine research paper on Harvard’s flow battery

- Nature magazine news summary about the flow battery

- MIT Technology Review

- Gizmag

[MUSIC: Marcia Ball “Mule Headded Man” from Roadside Attractions (Alligator records 2011) Happy Birthday Marcia Ball]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the new and sometime draconian measures cities are taking to deter private cars from driving downtown. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: James Booker: Medley Tico Tico, Papa Was A Rascal, So Swell When You’re Well” from Classified: Remixed & Expanded (Rounder Records 2013)]

Power Shift- Lessons From Massachusetts Public Transit

Boston’s Orange Line often runs over capacity at rush hour. (Photo: Steve Annear/Boston Magazine)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. On March 17, Saint Patrick’s Day, the air in Paris got so bad that the government finally imposed a driving ban. Three days earlier, officials made public transportation free in an attempt to limit the smog, but as throats and eyes continued to burn, authorities finally banned cars with even numbered license plates from the road. The driving ban was lifted after just one day, but not before the Parisian authorities handed out some 4,000 tickets. Public transit advocate Fred Salvucci is a former Transportation Secretary for Massachusetts who now teaches at MIT. He says the measures Paris took may seem extreme, but they're lenient compared to some rules in Asia - take Singapore.

SALVUCCI: On Singapore, they start by having a very good public transportation system, and it’s a small place, so you can get most any place on public transportation. Secondly, there are very high tolls to use the roadway system. They vary by time of day, designed to not allow congestion to get out of hand. Thirdly, in order to own an automobile, you have to first purchase a certificate of entitlement, and that certificate costs as much as the automobile itself. So the attempt to control the number of automobiles to below the level that will cause congestion problems, that’s a level of intervention into human behavior that is unlikely to be acceptable in Europe, let alone the United States. But they are doing it because they’re dealing with very big problems.

CURWOOD: So, what’s going on here in the US in terms of public transportation policies to address particularly climate and congestion.

Paris skyline (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

SALVUCCI: Well, maybe the place you see it most dramatically is Los Angeles. They’re building a rail system today because they have had consistently the worst air quality in the United States for the past 50 years. And it was largely the consciousness of that air quality that led them first to clean up the car. The reason we have much cleaner cars than we used to is that California responded to the air quality crisis by adopting much stronger regulations, and simultaneously recognized that cleaning the car isn’t enough when you continue to have more and more cars - that you had to both clean the cars you had and provide people with a public transportation alternative. We’re seeing that happen now in Los Angeles. People don’t usually think of Los Angeles as the American leader in public transportation, but if you look at where change is occurring, Los Angeles is the leader. We’re resting on our laurels here in the east. Our grandparents built these systems. We haven’t done all that much ourselves, but they’re really moving in LA.

Now the problem with climate change is that it’s nowhere near as tangible as the particulates that clearly cause cancer, exacerbate asthma problems. The air quality’s so bad in a place like Beijing that it motivates political change to deal with it. The challenge for us, in much of the United States, is that we have the sense to recognize a less visible problem like climate change. I kind of hope that -- Paris is a city that people like. China seems like it’s far away and such a different reality - a dozen cities with ten million or more, it’s just like huge. Paris is something a lot of Americans have been to. They love the city, and maybe the fact that they’re moving as aggressively as they are will kind of wake some people up.

CURWOOD: Why are people, particularly in this country, so resistant to taking public transportation?

SALVUCCI: Well, first of all, public transportation usually doesn’t go where you need to go. We’re relatively lucky here in Boston. People like to complain about the T, but it really does go to a lot of places that have a lot of jobs and a lot of hospitals and a lot of entertainment venues, so it’s much better than the options people have in most cities in the United States. The land use system in the United States has largely been shaped by the automobile. Most houses are built in places that don’t have good public transportation, and most jobs are located in places that don’t have good public transportation so you start off with something like 80 percent of the public really not having options to use public transportation. In cities like Boston, we have choices, and I think we should be using those choices.

Fred Salvucci, lecturer at MIT in Transportation Policy (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: In a city like Boston, there’s a lot of demand for public transportation. But as we see in a city like Boston, the system is struggling so hard to respond. Why do you think that is?

SALVUCCI: Well, we’ve had a long continual crisis at the T. It’s been worse for the past ten years. Governor Patrick tried twice to significantly improve the funding, and on this last effort, he got enough money to take the T out of crisis. So for the first time in at least a decade, the MBTA has an operating budget that is not operating in the red.

CURWOOD: Why do you think there was such reluctance over the past decade to improve public transportation in a city like Boston which, as you say, has a fairly good public transportation system? At least the architecture is pretty good.

The Boston region’s MBTA is extending it’s overnight services, but Frank Salvucci says the transit authority could be doing more to meet the demand for public transportation. (photo: public domain)

SALVUCCI: I really can’t explain it. It made no sense to me at all. Among the conditions for the approval of the Big Dig were a series of agreements that bus service would continually improve, that we would expand the transit system. There was a commitment to replace the vehicles on the Orange line in 1995.

CURWOOD: And the Orange line is?

SALVUCCI: Well, the Orange line is probably the backbone of the system. It runs through the downtown. It serves a primarily minority community to the south of the city and serves a largely blue collar set of communities to the north of the city, extremely high ridership. It’s running full, and the equipment is on its last legs. It was supposed to be replaced in 1995. Last time I checked this is 2014, and the T is now in the process of ordering the equipment, so there was a legally binding agreement to buy new equipment, and they just didn’t do it. It’s really hard to explain the level of irresponsibility. I think one of the problems is, particularly with a rail system, it looks so solid, and in fact, it’s quite robust - that you can get away with not taking care of it for a long period of time before it starts to visibly tell you that it’s time to invest, a prudent person would invest way before it gets to that point, but through the ’90s, and we just didn’t see that kind of priority put on it.

Singapore has some of the tightest traffic regulations in the world, all in an effort to limit urban air pollution (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Now, here in Boston, the MBTA recently announced that they’re going to extend their nighttime services and run until, something like three in the morning. What do you make of that?

SALVUCCI: Well, I think it’s good. I’m happy to see any recognition that improving public transportation is important for people. And there are a lot of...it’s not just kids going to bars. There are a lot of workers whose shifts begin or end when the MTBA does not currently offer service. So I think it is important to fill in that gap, on the other hand, given how bad the service is off-peak, there are lots of other things that the T needs to do as well. But any forward progress, I’m not going to knock. It’s a step in the right direction. We need a lot more steps in the right direction.

There’s increasing demand for urban public transit in the United States. Boston’s Orange Line often runs over capacity at rush hour.(photo: MBTA)

CURWOOD: Outline for me, what you, in your view as an engineer, someone who’s run a state transportation department, sees as what Boston could do better to improve its public transportation system.

Much of the transportation infrastructure in the United States was designed around the car. (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

SALVUCCI: Well, at this point, the most significant single thing would be to buy enough new equipment for the rail system, and modernize the signal system to significantly improve both frequency and capacity, so we’ve got the keys to the Boston metropolitan area economy relying on public transportation, particularly the Red line. And the best it can do is a four-and-a-half minute schedule. It’s operating at that. In London, a very similar line, the Victoria line, is running at two-minute frequencies, more than double the capacity and convenience that we’re offering on the Red line. And you really can’t accommodate a lot of new riders if you don’t get more capacity on the core of the system. That would be the single most important thing to do. Secondly, we’ve got to expand the bus system. The bus system is the foot soldier of public transportation. People don’t think it’s very glamorous, but most people use the bus to get to the train, and right now the buses are operating at or beyond their capacity. You often can’t get onto the bus because it’s too full. And the MBTA is running every piece of equipment it’s got during the peak. For starters, we can improve bus service in the off-peak right now with the existing equipment, so I think that’s a good place to begin.

Fred Salvucci with Steve Curwood (photo: Emmett FitzGerald)

CURWOOD: Fred Salvucci lectures at MIT on civil engineering and public transportation policy. Thanks so much for taking the time.

SALVUCCI: Thanks for having me.

Related link:

Fred Salvucci's page

[MUSIC: Meshell Ndegeocello “Dead End” from Weather (Naïve Records 2011)]

Small Matters: Emergence

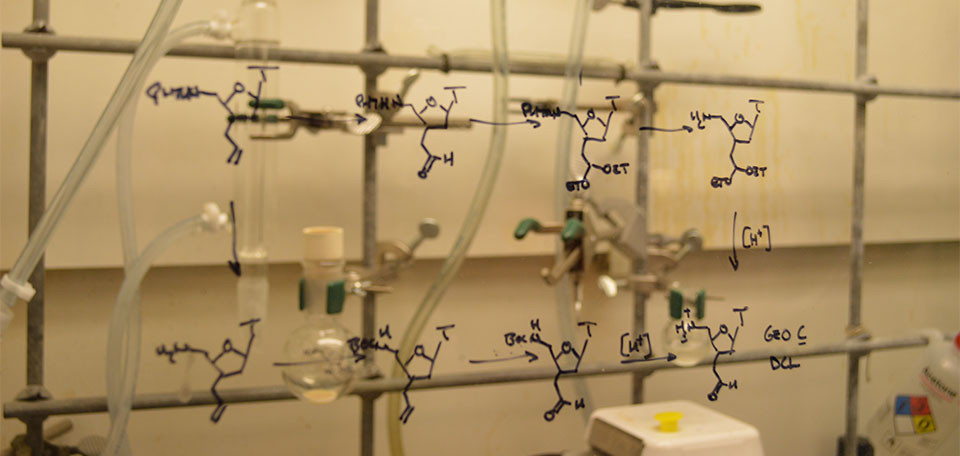

Jay Goodwin’s Chemistry routinely surprises him. (Ari Daniel)

CURWOOD: From traffic patterns to patterns in nature, the universe is full of seemingly random things that somehow manage to organize themselves into complex, even beautiful patterns. Think of crystals, or frost on a window. And it's that emergence of order from chaos that Ari Daniel describes in this week's episode in the occasional series, Small Matters.

DANIEL: Once in a while, if you’re lucky, you catch a glimpse of something that gives away a secret of the universe. It’s like a window – up into the heavens and deep into ourselves. This is a story is about someone who poked his head through just this kind of window, and we find him in Atlanta.

It’s a perfect day here – Jay Goodwin walks over to a bench to sit down. And he can’t help but be reminded about a day just like this one, 5 years ago, in western Michigan where he used to live.

Several years ago a chance encounter in the sky stopped Jay Goodwin in his tracks. (Ari Daniel)

GOODWIN: I was outside – I think I was going for a walk, just to kind of clear my head a little bit. I turned a corner, and I saw this flock of birds and they took off into the sky and they started to form a shape – sort of an amorphous shape. And it was one that was dynamic, and it was changing – but it had a boundary to it, like looking at a blob of oil in water.

DANIEL: It stopped Goodwin in his tracks. Several hundred birds pulsing and dipping and soaring to an invisible beat in the sky.

GOODWIN: It wasn’t clear what they were responding to – there weren’t any predator birds in the sky. And you never got the sense that there was anything that was directing it from within. There was no leader bird that they were all following. But just watching it was, well, it was beautiful.

DANIEL: Goodwin realized he had no way of predicting the flock’s behavior by simply taking lots of individual birds flapping their wings, and adding them up. Rather, it was something that emerged once all these birds threw themselves together. And it’s this notion of emergence – how really complex patterns and properties can arise from combining somewhat simple units – that now defines how Goodwin thinks about his real work. Chemistry.

Goodwin heads into his lab at Emory University. He’s a chemist here. And since seeing that flock, he’s come to appreciate how molecules are a lot like birds. That is – you get to know how the individuals behave and parade on their own, but then, you put them together. And often, something new and astonishing emerges.

GOODWIN: We always want to allow some room for serendipity – and allowing the molecules themselves to show us what they’re capable of doing.

It’s not easy to predict what will happen when you bring molecules together. (Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: Let’s take an example. A glass of water.

GOODWIN: Water molecules in the liquid form are tumbling past each other, and they see each other very dynamically, very quickly, and they move on.

DANIEL: Now cool that water down. The movement of the water molecules begins to slow, and they spend more time kind of looking at each other.

GOODWIN: And they begin to align with each other, and become solid. And they grab more water molecules out of solution as they slow down, and that process begins to propagate and to grow until the whole thing is one big lattice of solid ice.

DANIEL: And the thing about ice – it floats on water. We take that for granted, but most solids sink to the bottom of their liquid form because they’re more dense. Not water. It floats – which is crucial for life.

GOODWIN: Underneath ice in a lake or an ocean or the Arctic is liquid water. That’s one of the unique features of water. That’s an emergent property.

DANIEL: Emergent, because it’s just what happens when you throw a bunch of water molecules together, and cool them down.

Now, Goodwin doesn’t study water. He’s curious about other things, like how, in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, a single misshapen protein can trigger neighboring proteins to buckle and warp, until a tangled plaque has emerged. Like an errant bird reshaping its entire flock. Goodwin also studies what might have happened on the Earth a few billion years ago – trying to learn the rules of how simple molecules might’ve assembled to lead to the emergence of life. Emergence, it turns out, is everywhere.

GOLDBART: There’s no particular reason why emergence should be a property that happens at the scale of atoms and molecules, but not at the scale of let’s say viruses, or even galaxies for that matter.

DANIEL: Paul Goldbart is a physicist at Georgia Tech who studies how the building blocks of matter interact to form the very small, the very big, and everything in between. He says it’s like watching a dance – knowing that the whole isn’t just greater than the sum of the parts – it’s wondrously different.

GOLDBART: We marvel at the way matter organizes. Not only do we get to see beauty and organization and patterns, but also they’re useful to better society and provide services and materials that make our lives safer and more vibrant.

DANIEL: Back in the lab, this is exactly what Jay Goodwin is doing. Harnessing the idea of emergence, by putting molecules together and watching what happens, by creating room for his chemistry to surprise him – and then, turning those insights to use.

GOODWIN: To understanding disease and how to solve disease, and how to develop new therapeutics, and how to diagnose disease and how to create new materials that could be intelligent, that could respond to their environments in different ways – could be self-?? healing, could capture solar energy for instance.

DANIEL: Goodwin’s aim has become one of taking advantage of the rules that determine how molecules behave. Rules that are somewhat mysterious, and can emerge when you take the time to appreciate that they’re there.

For Living on Earth I’m Ari Daniel.

CURWOOD: Our series, Small Matters, is produced by the Center for Chemical Evolution, with support from the National Science Foundation and NASA.

Related links:

- Small Matters

- Small Matters: Emergence

[MUX - BIRD NOTE® THEME]

BirdNote ®: Vernal Equinox

A male Ruby-Crowned Kinglet (© Greg Thompson)

CURWOOD: Well, though winter has seemed truly interminable this year in parts of North America, the calendar tells us it's not so. Indeed, that yearly miracle marked in the heavens - spring - is now truly with us as Mary McCann and some other creatures celebrate in today's BirdNote®.

MCCANN: Ahhh, the first day of spring . . .at last! Let’s step outside and greet the new season. Clearly, the birds know somethin’ is up. Listen to that Bewick’s Wren belt it out.

Bewick’s Wren in full song (© Tome Grey)

[BEWICK’S WREN SONG].

The wren doesn’t know the precise instant of the vernal equinox, of course. It’s the moment when the sun is directly above the equator, and day and night are nearly equal all over the world. Yet the wren senses the growing hours of daylight through a surge of hormones. It’s time to sing!

[BEWICK’S WREN SONG]

Both science and folklore tie Spring to the renewal of nature, as the world awakens from the long cold winter.

[SPOTTED TOWHEE SONG]

Spotted Towhee Singing (© Tom Grey)

A Spotted Towhee shouts out its burry notes.

[SPOTTED TOWHEE SONG WITH MULTIPLE NOTES].

A female Ruby-Crowned Kinglet (© Greg Thompson)

And, wow! There’s a tiny Ruby-crowned Kinglet, flashing its red crown. Listen to its song bubble forth.

[RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET SONG].

Now there’s a comical sound, coming from the marsh. It’s a Virginia Rail, unseen but hardly unheard, ringing in the new season.

[OINKING PHRASE OF VIRGINIA RAIL VOCALIZATION].

Spring has sprung. The birds declare it official.

A Virginia Rail calling (© Greg Thompson)

[RUBY-CROWNED KINGLET SONG]

I’m Mary McCann.

[http://birdnote.org/show/vernal-equinox-west

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Dawn song recorded in Redmond WA by Martyn Stewart, naturesound.org

Other bird audio provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Songs of the Spotted Towhee and Ruby-crowned Kinglet recorded by G.A. Keller. Bewick’s Wren song recorded by M.D. Medler. Call of Virginia Rail recorded by W.L Hershberger.

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature..org Narrator: Mary McCann]

CURWOOD: To see some photos of all the birds singing so joyfully in today's BirdNote®, hop on over to our website LOE.org.

Related link:

BirdNote ®

CURWOOD: Coming up...the lengths and depths some sea creatures go to survive and thrive.

That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

[MUSIC: John Coltrane “Equinox” from Coltrane Sound (Atlantic Records 1959)]

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: “Boubacar” from The Intercontinentals (Nonesuch Records 2003) Happy Birthday Mr. Frisell]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Beyond the Headlines

Wyoming is the largest exporter of coal in the US . State officials don’t want to adopt new science standards which would teach children about climate change. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. We turn now to our guide to the world beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra. He's the publisher of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News - that's EHN.org, and joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve. This week I’m going to get a little Biblical on you.

CURWOOD: Uh-oh.

DYKSTRA: There’s a great climate website, it’s called DeSmogBlog, it’s based in Vancouver, Canada. They had an item last week that really knocked me over. Reporting on Congressional testimony, it was revealed that 36 percent of all the natural gas extracted in North Dakota during the month of December was flared off. That means it was burnt, it was wasted, it was just tossed into the atmosphere.

CURWOOD: That’s not a number to be proud of, but where does the Bible come in?

DYKSTRA: Well, I’m thinking of the Seven Deadly Sins. There are versions of the Seven Deadly Sins in the Old Testament, in the New Testament, and, of course, also in Wikipedia, which is technically considered to not be part of the Bible. I started thinking about how many of the Seven Deadly Sins are covered by wasting 36 percent of the energy that you drill out of the ground.

CURWOOD: And remind us, please, what the Seven Deadly Sins are.

DYKSTRA: The Seven Deadly Sins are: wrath, greed, sloth, pride, lust, envy and gluttony.

CURWOOD: Let’s see. When it comes to natural gas, I think we can take “wrath” off the list, “lust” and “envy”, but...

DYKSTRA: But maybe not the other four. You’ve got greed, sloth, pride and gluttony – tapping into a major energy source that may have huge environmental baggage anyway, and then tossing away a third of it, more than a third, even while the prices for natural gas and propane in this country have shot through the roof this winter. That’s four out of seven deadly sins in one operation. In fairness, though, the US isn’t the worst waster of gas...that honor goes to Russia.

More than a third of all the natural gas collected in North Dakota in December was flared off and wasted. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: OK, Peter. Now, what else do you have for us?

DYKSTRA: We’ll go to the state of Wyoming. The state has taken a very bold stance against the teaching of science. The state legislature and Governor Matt Mead have blocked Wyoming from adopting what’s called the Next Generation Science standards. That’s a series of guidelines that were drawn up by a nationwide team of science educators about a year ago.

CURWOOD: So what’s their beef?

DYKSTRA: Well beef’s big in Wyoming, but coal is much, much bigger. Wyoming is far and away the biggest coal-producing state, with almost 40 percent of the nation’s total output. And the Next Generation Science Standards would teach school kids about climate change, and in Wyoming that would cause some pretty strong political blowback. The Governor and the State School Board chair are big climate skeptics, the key legislator in all this said that, and this is a quote, “There’s all kinds of social implications involved in that and I don’t think it would be good for Wyoming.”

CURWOOD: It sounds like he’s saying that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, he’s saying knowledge is dangerous, and maybe he’s also saying that ignorance is bliss. And of course, that works every time, doesn’t it?

CURWOOD: OK, Peter, before you go, what’s on the calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: Steve, there’s some high-profile environmental disaster anniversaries this week: the Three Mile Island nuclear plant partial meltdown was 35 years ago; the Exxon Valdez oil spill was 25 years ago, but one of the biggest disasters is one that very few people know about.

CURWOOD: And that would be?

DYKSTRA: Well, 58 years ago this week, Congress approved construction of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, a canal for flood relief and a shipping shortcut from New Orleans to the ocean.

CURWOOD: But better known for helping flood New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

DYKSTRA: Yes, that’s right. The Mississippi River Gulf Outlet, MRGO, better known by its adorable little acronym of “Mister Go,” was a shipping shortcut out of New Orleans but it also was a storm surge shortcut into New Orleans. It was closed down a few years after the Katrina disaster.

CURWOOD: Ah yes, a very big barn door closed after a very big horse got in.

DYKSTRA: That’s right.

CURWOOD: Well, there are links to all these stories at our website, LOE.org. Peter Dykstra is the publisher or DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News - EHN.org. Thanks, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks, Steve. Talk to you next week.

Related links:

- The Daily Climate

- Environmental Health News

- Peter Dykstra

The Extreme Life of the Sea

For clownfish, the bigger the better (Photo: Eddie.Welker, Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: They say that a period at the end of a sentence represents how much or how little we know about the world’s oceans. This underwater universe seems alien to most of us, but it represents the essence of life on this planet. In an engaging new book called “The Extreme Life of the Sea”, biologist Steve Palumbi and his novelist son Tony deepen our understanding of how strange sea life has managed to survive against all odds. Joining us is half of the pair of authors, Steve Palumbi, a professor of marine biology at Stanford University. Welcome to Living on Earth.

PALUMBI: Hi Steve. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Why did you write this book. Why now?

PALUMBI: Well, the real reason is that we’re trying an experiment: can you take the narrative style and approach that a novelist would use and combine it with what a scientist would do? And come up with an environmental narrative that is more engaging than we’re used to. It’s all sort of, in a small way, described by a simple phrase: that you don’t really care about the plot until you care about the characters, and so we wanted to write a book that made you care about the characters.

Coauthor and scientist Stephen Palumbi, doing some research on corals (Photo: Dan Griffin, GG Films)

CURWOOD: Now, you write about the extreme life of the sea, the oldest, the hottest, the shallowest, to name a few. Why did you choose this approach?

PALUMBI: Because it was a way of getting people’s attention to the really sort of amazing things that these critters do. Organisms in the sea live in some of the hottest places, they live in some of the coldest places, and how they do that is something marine scientists have paid a lot of attention to. So it was really a way to make it more engaging, more fun, and to let us move credibly between different kinds of organisms all in the same chapter.

CURWOOD: Now, which of these particular extremes did you like and why?

PALUMBI: I was most surprised by all the information we got about the oldest creatures in the sea.

CURWOOD: And the oldest are?

PALUMBI: Well, the oldest by far is that set of deepwater corals off the coast of Hawaii. Black corals, they live in about 1,000 feet of water. It’s dark, it’s steady currents, it’s a very, very, calm and steady environment. And those corals are clocked, the oldest one we know about, at 4,200 years old.

CURWOOD: That’s old.

PALUMBI: That’s old. I mean, these corals we’re alive before some of the pyramids were started.

Anglerfish use bioluminescence to attract their prey in the darkest depths of the ocean (Photo: Masaki Miya et al. Wikimedia Creative Commons)

CURWOOD: Speaking of age, you had one extreme that you called immortal.

PALUMBI: That’s an amazing jellyfish called turritopsis, and it has the remarkable ability to age in reverse. So when the environment is bad, this animal can essentially go from its adult body form back, back, back to its larval form, and then start all over again.

CURWOOD: It’s reborn, huh?

PALUMBI: It’s reborn. It’s called transdifferentiation. It’s the only critter known to be able to do that.

CURWOOD: Hmmm. Wonder if I could package that?

PALUMBI: [LAUGHS] Well, you know, there’s lots of movies about when you all of a sudden wake up and you find you’re back in high school, and so do you really want to do that, Steve?

CURWOOD: Oh, I don’t need to go back there.

PALUMBI: Think about it. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: Tell me about your favorite from the deep, deep, deep.

PALUMBI: One is this amazing critter called the Stoplight Loosejaw. Like typical deep sea fish, it’s got fangs and a huge jaw and amazingly sharp teeth. It can actually eat a fish bigger than itself. The deep sea is extreme in that it’s dark, and there’s also not much food. There’s bioluminescence, flashes of blue and green that are down there, and if you use your light as sort of a search light to find something then everybody else can see you too, and come after you.

So the Stoplight Loosejaw fixes that problem by cheating. It has two searchlights that beam out from under its eyes, and they’re not the typical blue-green of bioluminescence. Those searchlights are red, and they also change their eyes so that they can see red. So the only fish down there that sees red, and then produces red light. So they can prowl around with these search lights on and nobody else can see them, but they can see their prey.

CURWOOD: So a predator with night vision.

PALUMBI: A predator with night vision goggles essentially, yes, so imagine if you’re some laser tagger in an arena and you’re the only one who can actually see anybody else.

CURWOOD: Describe the whale fall and why these are important.

PALUMBI: The whale fall is an amazing exception to the generalization that the deep sea has not got much in the way of food. When a whale dies, it often dies in the middle of the ocean in deep water, and it falls down to the bottom of the sea with a sort of plumph that dumps tons of meat and bones and gristle all at once. It’s an incredible instant oasis of food, and from all around, critters come immediately to start feeding on it, and they disassemble the whole skeleton in just a matter of weeks. But it goes beyond that because a set of predators comes in to eat the critters that are eating the whale, and they slowly all form this community - short-lived community - until most of the whale is gone. And then you have the bones left, scattered around the bottom, but the bones of the whale are actually enormously valuable for food. They’re full of oil. So another set of critters comes and lands on those bones and starts feeding on those. Finally, all you’re left with is just a thin dusting of the remains of an entire whale and all the bones on the bottom of the sea floor.

Coauthor and writer Anthony (Tony) Palumbi (Photo: Dan Griffin, GG Films)

CURWOOD: Now there’s some pretty interesting sex lives. Tell me about these.

PALUMBI: [LAUGHS] It turns out one of the most extreme things about marine critters is their family lives. For example, another deep sea example is the Anglerfish, made popular in the “Finding Nemo” movie, have a remarkable lure that attracts prey to them. And scientists studied them for a century or more, always bemoaning the fact they could only find females. And then a parasitologist was working on them looking at the parasites that these females always seem to have hanging off them and discovered that those were the males. They were parasitic males attached to the females, and living only with them, depending totally on the females for everything. After they bite the female their jaws dissolve, and then their brains dissolve, and then their guts dissolve and then their blood systems mesh with the females, and all they are just at the end is a testes that’s there to fertilize the female’s eggs when she’s ready.

CURWOOD: I thought you weren’t going to talk about human relationships here.

PALUMBI:[LAUGHS] Well, when we give these book talks, the women are usually laughing, the men are somewhat bemused, and then, by the end, the men are all horrified.

CURWOOD: One of the most fascinating parts about your book is how you tell the story of evolution through microbes in the ocean. What made you decide to do that?

PALUMBI: Microbes are the smallest creatures in the ocean, but they are by far the most numerous, and you can’t understand the life of the ocean without including them. They are, in fact, the organisms that determine that the ocean is livable. You might be referring to the evolution part to a sort of scary, shivering, chilling type of process that biologists have called “kill the winner”. And here’s the way it goes. The microbes in the sea, you think the best one would take over...the one that could grow the fastest in the most places, but that doesn’t happen. The microbes in the sea are incredibly diverse, and it boils down probably to the enemies of these microbes, and those are viruses, and any microbe that gets good enough and big enough and abundant enough to maybe take over the ocean is also a target for viruses that evolve to attack them specifically. So the viruses are constantly killing the winner of the competitive race among microbes in the ocean, and by doing that, they’re keeping the ocean in balance and highly diverse.

CURWOOD: Now, how does the human consumption of seafood affect the marine ecosystem and the balance of bacteria?

PALUMBI: You know, Steve, the real problem is that this huge ocean with all these creatures in it is not big enough that is immune to the kinds of changes that we can make in it. In particular, overfishing has the effect of breaking the food chains that the ocean normally has. And you can think of the food chain as taking the smallest little critters, and they’re food for the next larger ones, and they’re food for the next larger ones up. And so the food energy in the ocean - or any ecosystem really - moves from the smallest critters up through the bigger and bigger and bigger ones. But when we fish, especially fish heavily, we break the food chain. We end up, essentially, allowing the food energy to clump up at parts of the food chain that it doesn’t usually. So we get big huge blooms of jellyfish, for example, with the ocean out of balance by us overfishing.

CURWOOD: Talk to us about how climate change is affecting the life of the sea.

PALUMBI: So climate change is a pervasive, growing and huge problem. It’s, of course, making the sea level rise. It’s also making the oceans warmer, it’s making them more acidic and stormier. And all these things mean that how we interact with the ocean is getting harder and harder, and a lot of the organisms that we might depend on to grow barriers, natural living sea walls, for example, around our coast are succumbing to extra heat and the acidification. And these problems are visible now, and they’re projected to grow into the future. If we stopped the process by which climate change is happening, which is, we stop carbon emissions, it’s still going to take 50 years or so for the oceans to absorb what we’ve already put into the atmosphere and begin to get better.

So it’s like you’re booming along in a speeding car, and all of a sudden you see the red brake lights in front of you, and you think, “OK, we’ve got to stop,” but there’s a stopping distance. You can’t stop immediately. You can’t stop a speeding car right on a dime. It takes a while. And that stopping distance for climate change is about 50 years, so the biggest problem is that we’re just now beginning to see the red lights in front of us, and even if we all decided, “OK, we’re going to put the brakes on now,” which we have not yet decided, but if we did, we’d still have 50 years of stopping distance before things got better.

CURWOOD: Steve, what do you hope readers will take away from your book?

PALUMBI: We wrote the book to give readers a sense of guiltless wonder about how wonderful the life of the ocean is, and that these critters out there are not just seafood, they live in all the corners of the ocean, they can live and thrive in amazing places with amazing abilities, and that they add to the wonder of our planet. It’s really a book that’s meant to entertain people, it’s meant to give them the sense of, “Wow, I never knew that.”

CURWOOD: Steve Palumbi is a Marine Biologist at Stanford University and co-author of “The Extreme Life of the Sea”. Thanks so much for taking this time today, Steve.

PALUMBI: Hey, Steve, it’s an absolute pleasure. Thank you.

Related links:

- The Extreme Life of the Sea Tumblr

- Extreme Life--Shark

[MUSIC: Extreme Sea: Ernest Ranglin “Black Disciples” from Below The Bassline (Island Records 1996)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Clairissa Baker, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Catalina Pire-Schmidt, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stephenson Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth