May 16, 2014

Air Date: May 16, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Reducing the Risk of Breast Cancer

View the page for this story

A recent study from the Silent Spring Institute catalogued common pollutants and chemicals that increase breast cancer risk. The Institute’s Executive Director, Dr. Julia Brody, tells host Steve Curwood how to minimize exposure to these carcinogens and so reduce the risk. (07:05)

Oil Boom And Worker Deaths

View the page for this story

North Dakota is now the most dangerous state in the US for worker safety. Journalist Tim McDonnell tells host Steve Curwood that a dramatic rise in workplace deaths since 2007 has coincided with the Bakken Shale’s boom in oil and gas drilling and fracking. (06:00)

The (So Far) Elusive Dream of Carbon Capture And Storage

View the page for this story

Concerns about rising carbon dioxide levels mean that coal must capture and sequester its CO2 emissions to have a future. But Reid Frazier reports that despite years of experiments there is still not a cost-effective way to employ carbon capture technology at coal fired power plants. (07:40)

Deep Seabed Mining

View the page for this story

It sounds futuristic, but a Canadian company has struck a deal with Papua New Guinea to mine gold and other metals from deep beneath the sea. Greenpeace campaigner Richard Page tells host Steve Curwood the project raises concerns about the impact on life in the deep ocean. (06:30)

Gold Mining & Child Labor

View the page for this story

In the Philippines children as young as 5 help with a particularly dangerous form of shallow water gold mining, called compressor mining. Center For Investigative Reporting journalist Richard Paddock tells host Steve Curwood that exposure to mercury used in the gold mining operations is particularly dangerous for children. (05:45)

CO2 Can Reduce Food Value

View the page for this story

A study in the journal Nature finds key agricultural crops grown in an elevated carbon dioxide environment can contain less zinc, iron and protein. Lead author Sam Myers tells host Steve Curwood that atmospheric CO2 levels are expected to reach 550 parts per million by mid-century, which would be adverse for staple crops that support human nutrition. (06:35)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

Peter Dykstra peaks beyond the news headlines with host Steve Curwood, and finds that though Donald Trump may not believe in climate change, he is building three sea walls to protect his Irish golf resort from sea level rise. Also India—not China—has the most cities with devastating air pollution. (04:30)

The Mysterious Sound Of Snipe

View the page for this story

In springtime a weird sound echoes above the flooded meadows and marshes of Yellowstone National Park as dusk gathers. In this audio postcard producer Jennifer Jerrett investigates the mysterious reverberations from a bird called Wilson's snipe. (03:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Julia Brody, Tim McDonnell, Richard Page, Richard Paddock, Samuel Myers

REPORTERS: Reid Frazier, Jennifer Jerrett, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Breast cancer rates are rising, and common chemicals are a big risk.

BRODY: We have been surprised at the range of chemicals that have been found to cause mammary gland tumors in rodents and how very common they are in our everyday lives.

CURWOOD: Also, amounts of atmospheric CO2 are now higher than they've been in perhaps millions of years, changing the climate and reducing nutrition in major food crops.

MYERS: Rising concentrations of carbon dioxide really threaten global human nutrition, significantly reducing the levels of important nutrients for human health. We lose about 63 million life years annually from nutrient deficiencies today.

CURWOOD: Those stories and [WILSONS’S SNIPE WINNOWING SOUNDS] the sound of snipe this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Reducing the Risk of Breast Cancer

Pumping gas can increase exposure to breast cancer-causing chemicals. (Photo: Big Stock)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Here's a sobering fact - breast cancer is the leading cause of death among US women between the late 30s and early 50s, and rates are rising. And though obesity and genetics account for some of the risks, much of the danger comes from repeated exposure to certain chemicals in our homes, air and water. Research just published in Environmental Health Perspectives identifies the most frequently encountered breast carcinogens and suggests ways people can reduce their exposure. Julia Brody is Executive Director of the Silent Spring Institute in Newton, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the paper. She joins me now to explain how the research was done.

BRODY: We assembled a list of all the chemicals that have been shown in animal studies to increase mammary gland tumors, and there are about 216 of those chemicals. Then we narrowed it down to the ones that women are most commonly exposed to, and set a priority on 100 chemicals that are very common, and women are exposed to every day.

CURWOOD: So what kinds of chemicals are you talking about here?

BRODY: We’re talking about chemicals that are in air pollution, diesel exhaust, gasoline, perfluorinated compounds - those are in non-stick and stain resistant surfaces - some flame retardants and a variety of chemicals that are in consumer products and workplaces.

Pumping gas can expose people to carcinogens linked to breast cancer (Photo: Big Stock)

CURWOOD: Out of your study, you developed seven tips to reduce exposure to likely breast carcinogens. First thing you mention is to lessen exposure to fumes from things like gasoline.

BRODY: I will say that I think it’s very important for people to understand that air pollution is actually a breast cancer issue. One of the most important areas we found was the number of breast carcinogens in gasoline and in auto exhaust and diesel exhaust. We can each reduce our exposure to these by reducing use of gasoline, for example by getting an electric lawn mower or high-efficiency vehicle. And we can also take action at the community level. For example, you often see buses or cars idling in front of a school, and if those engines are turned off, then the kids and the parents who are picking them up are not exposed so much to these breast carcinogens, these chemicals in gasoline and vehicle exhaust include benzene and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These are priorities on our list of breast carcinogens.

CURWOOD: Now, what about at the cook stove?

BRODY: There are two things you can do. One is to turn on the ventilation fan so you’re exhausting the PAHs and the smoke out of your house. The other thing is to cook at a lower temperature so you’re not creating char on your food, delicious as it may be, it does contain breast carcinogens, and if you just cook at a lower temperature, or marinate before you cook, that will reduce your exposure.

CURWOOD: You say there are risks with dry cleaning. What should one do?

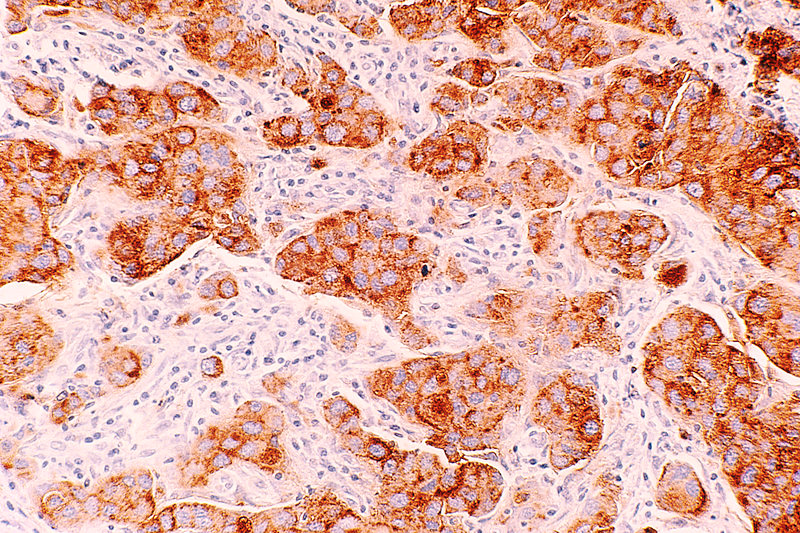

Breast Cancer Cells (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

BRODY: Nowadays it’s not too hard to find a drycleaner who will do what’s called “wet-cleaning”, so ask your drycleaner if they have a method that doesn’t use PERC, perchloroethylene, or other solvents.

CURWOOD: What about drinking water?

BRODY: Well, of course, we want our drinking water to be free of any pathogens that might cause sickness. But in the process of disinfecting water, we’re inadvertently sometimes creating carcinogens and we found that, for example, MX is created from the process of chlorinating drinking water. A solid carbon block filter will remove that so you can reduce exposure in your home by installing a solid carbon filter.

CURWOOD: You have some advice about furniture and rugs and that sort of thing. What is that?

BRODY: Some of the chemicals that are used in non-stick and stain resistant surfaces and also flame retardants in polyurethane foams are on our breast carcinogens list. We really need manufacturers to figure out a better way to make things - we don’t need these chemicals in our products, and meanwhile you can avoid stain resistant furniture and fabrics and avoid polyurethane foam or now you can ask for foam that doesn’t have these flame retardants in it.

CURWOOD: And you have some advice around housecleaning.

BRODY: Yes, many of these chemicals that are in consumer products end up in house dust, and we inadvertently end up eating it. Kids, of course, are especially exposed to house dust, because they’re crawling around on the floor and putting their hands in their mouth. But even adults are actually consuming a fair amount of house dust, so one way to reduce your exposure to toxic chemicals is to keep dust levels low by wiping with a wet rag or wet mop or using a vacuum with a HEPA filter. And you can keep the carcinogens that are outside out of your house by putting in a rug just inside your doorway and taking off your shoes when you come house.

Julia G. Brody, PhD, Executive Director at the Silent Spring Institute is a co-author of the research paper on breast carcinogen exposures published in Environmental Health Perspectives (Photo: Silent Spring Institute website)

CURWOOD: Now most of these chemicals are chemicals that have been suspect for a good while. Just wondering if you had any surprises when doing this research.

BRODY: I would say we’ve been surprised at the range of chemicals that have been found to cause mammary gland tumors in rodents, and how very common they are in our everyday lives. And we have seen an increase in breast cancer incidents since the beginning of the chemical era, and perhaps we could roll some of that back by reducing exposures.

CURWOOD: These are things that individuals can do. As a society, what should we be doing to minimize exposure to these chemicals linked to breast cancer?

BRODY: Well, there are two big areas where we could be doing a lot better. One is air pollution controls and fuel efficiency. The other is rules for chemicals in consumer products. Many people don’t realize in the US you can put chemicals into products without any health or safety testing to check whether they might cause breast cancer. We have an “innocent until proven guilty rule” for chemicals in consumer products, and there’s an effort at the national level to switch to a “better safe than sorry strategy” that would require manufacturers to test chemicals and provide some evidence that there safe before they go on the store shelves. Those are some important changes that we need to enact.

CURWOOD: There’s been an effort on Capitol Hill to re-write what’s known as the Toxic Substances Control Act. What do you think of those efforts?

BRODY: We desperately need reform of the Toxic Substances Control Act, but we need to make sure that what we do next is better than what we have now. Right now there’s some proposals on Capitol Hill that will not solve the problem. We need new legislation that will actually protect health, that will require safety testing of chemicals before they’re put into use in consumer products that we all use every day.

CURWOOD: Well, I want to thank you for taking the time with us today. Julia Brody is executive director of the Silent Spring Institute and one of the authors of the paper recently published in Environmental Health Perspectives. Thank you so much.

BRODY: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Read the Silent Spring Institute’s research published in Environmental Health Perspectives on common means of exposure to chemicals associated with breast cancer

- Seven simple steps suggested by the Silent Spring Institute to avoid pollution and chemicals linked to increased risk of breast cancer.

- Brief discussion of the research conducted by the Silent Spring Institute on common exposure to breast carcinogens.

Oil Boom And Worker Deaths

Oilrigs dot the landscape in parts of North Dakota. (David Porchlife)

CURWOOD: In just a few short years North Dakota has surged to become the second largest producer of oil in the US after Texas. People are flocking to the Bakken Shale region for high-paying jobs in the oil boom. Truck drivers can earn as much as $90,000 a year, but that prosperity comes at a price. North Dakota now has the highest rate of workplace fatalities in the US. Tim McDonnell of ClimateDesk.org says there is a direct connection between the oil boom and the epidemic of workplace deaths.

MCDONNELL: So if you go back to 2007 in North Dakota they were producing just a little bit under five million barrels per month. Now, as of February ’14, it was just under 30 million barrels per month. So it’s gone up several times, and really it’s right around 2009, 2010, is when you really start seeing that big uptick. That was the beginning of the boom in North Dakota really. And that’s really the same year right around 2010 when you start to see this uptick in workplace injuries and fatalities.

Temporary housing for oilrig workers in Watford City, North Dakota. (Don Barrett)

CURWOOD: So, just how dangerous is it to work in North Dakota?

MCDONNELL: So what’s reported in this new compilation of federal data that’s just been put out by the AFL-CIO is 2012 statistics that are new, the rate was just over 17 deaths per 100,000 workers, which is by far the highest out of any other state. The national average is just over three. And what’s particularly interesting about North Dakota is not just how high the number is, but how quickly it’s come up to be that number. It’s more than doubled from where it was in 2007, so just in the last five years it’s been on this incredible uptick.

An oilrig worker on the job. (Lindsey Gira)

CURWOOD: Tim, where specifically in the workplace are these fatalities happening?

MCDONNELL: Most of these deaths are taking place in transport-related activities. This could be related to any number of different industries, but that’s this sort of activity that people tend to be doing. Now, as far as which industries tend to be the most accident-prone, construction and mining, which includes oil and gas extraction, those are the two big ones.

CURWOOD: Now, transportation, that seems a bit surprising. Why is it so dangerous to drive in North Dakota?

A North Dakota oil truck passes in front of a gas flare. (Tim Evanson)

MCDONNELL: So one reason for that is really just the pace, the sheer speed at which this boom is taking place. There’s huge amount of truck traffic, thousands and thousands of trucks that are bringing in water and chemicals and sand for the fracking operations, and then bringing out oil which is all mostly done by trucks. Also, these are on poorly maintained or brand new roads, and you have drivers working in trucks who have to work long 12-hour shifts on poor quality roads, and there’s kind of no incentive to stop working.

CURWOOD: Now, this oil and gas boom is relatively new to North Dakota. How well trained are the people who are working there?

MCDONNELL: Yeah, what’s interesting here is that there’s so many job openings, and many of them pay quite well, that you have people coming from all over the country to take these things, and in a lot of cases, they’re coming into the industry for the first time. And so, compared to a place with an established industry like Texas or Alaska, you have a lot of people coming in who are quite inexperienced. They’re not trained, and then you combine that with the fact that you have a lot of companies that are growing quite quickly who don’t have the resources or their own experience to be able to train people, so it’s kind of this combination of those things that can contribute to making this kind of unsafe atmosphere.

CURWOOD: How much of the death rate do you think is attributable to the frontier mentality that’s there...it’s a macho thing...gotta go for that gold right now?

MCDONNELL: I think that’s absolutely a big part of it, and I’ve heard that from people that I’ve spoken to over there. I mean, it has the feel of a gold rush, you know, the Klondike, Alaska, or California gold rush, it’s very much that same type of attitude that most of the people who are working there taking these jobs are men, they’re away from their families, you’re living in a camp with 100 other guys, so there is very much a macho attitude. Nobody wants to admit that they are exhausted or that even that they have injured themselves and don’t want to report it because they don’t want that to reflect poorly on them or their company.

CURWOOD: Now the data for these workplace safety records comes from the union group AFL-CIO, and according to their research, the states with the most workplace deaths are: North Dakota, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and West Virginia. And I notice that all of these states have a lot of extractive industries. Coincidence?

MCDONNELL: I think it’s probably safe to say it’s not a coincidence. If you look kind of broadly across all states, you find that mining, which includes coal mining like you said in West Virginia, it also includes oil and gas drilling, is the second highest number of fatalities, or the second highest rate of fatalities for all industries. Actually, agriculture and forestry tend to be higher. I think people working with farming equipment is also quite dangerous. So I think the data is quite clear between workplace safety and states that have a large robust oil industry. It’s obviously, relative to other industries, is quite a dangerous one to be in.

CURWOOD: So, if a worker is five times more likely to die in North Dakota than in the rest of America, what should be done to make North Dakota safer for workers?

MCDONNELL: Every time I ask this question, whether it’s to someone at the AFL-CIO or truck drivers themselves in North Dakota that I’ve spoken to, everyone basically agrees that the main thing here is that it’s all just happening too fast. People need to slow down, and you need to have protections in place so that truck drivers, for example, which clearly is one of the most dangerous things you can be doing out there, are working shorter shifts, making sure they have a place to stay so they can get a good night’s rest and be refreshed and ready to go back on the job the next day, and not driving when they’re exhausted and tired. It’s almost kind of basic stuff like that, but when you have a boom kind of context like in North Dakota, I think those are the things that get glossed over quite easily and could be kind of the easiest types of things to do to make the place a lot safety.

CURWOOD: Tim McDonnell is an Associate Producer at ClimateDesk.org. Thanks so much for taking the time, Tim.

MCDONNELL: Thanks very much, Steve, appreciate it.

Related link:

Climate Desk

[MUSIC: Robbie Robertson “The Code Of handsome Lake” from Contact From The Underworld Of redboy (Capitol records 1998)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the allure of gold and other minerals on the deep ocean floor and the renewed race to retrieve them. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Red Garland: “Your Red Wagon” from Red In Bluesville (Prestige Records 1959)]

The (So Far) Elusive Dream of Carbon Capture And Storage

Tom Crooks, of the R.G. Johnson Co., at his company's new workshop in Waynesburg, Pa. The coal mining construction company has about 35 laid-off employees. Photo: Reid R. Frazier

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Mining and burning coal goes back in the ages. China used coal as early as 3400 BC, and of course it fueled the Industrial Revolution beginning more than two centuries ago. Today it's a fuel under fire as a driver of pollution and global warming. And while coal still leads electricity generation in the US, the industry has been put on notice that it must adopt a low-carbon diet to survive. Carbon capture technology could be the answer, but as Reid Frazier of the public radio program the Allegheny Front reports from western Pennsylvania, even after two decades of research that technology is still not ready for prime time.

FRAZIER: Tom Crooks walks through a brand new industrial building in Waynesburg in the southwest corner of the state. This is Pennsylvania’s coal-mining country. Some of the biggest mines in the state are right down the road. There are stacks of supplies and machinery in tidy bundles scattered throughout the floor.

CROOKS: You see some drill steel, you see hoses, these are for spraying concrete.

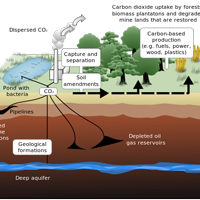

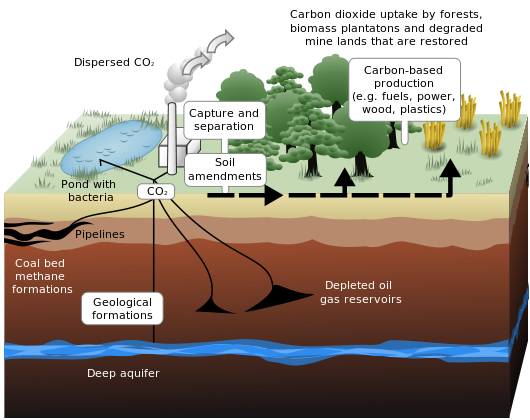

A diagram of carbon capture and storage. (Wikipedia Commons)

FRAZIER: Crooks is a vice president of the RG Johnson company, which helps build coal mines in Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

CROOKS: We spray concrete on the ceiling to help hold up the mine roof. A lot of what we do is concrete construction in the mines for the big infrastructure materials. A concrete floor like you see here that we’re standing on—in the coal mine we have concrete floors.

FRAZIER: The company just built this new workshop. Crooks says it’s a sign that the company thinks coal is here to stay. But there are signs the industry’s prospects are tenuous. RG Johnson has 150 employees, but not everyone is working right now.

CROOKS: So we have about 35 people laid off. That’s not what we want. We want to have 150 people working, full-time, all the time.

FRAZIER: Crooks says federal carbon regulations are partly to blame. A recent UN climate report found the world will need to drastically cut CO2 emissions to stave off runaway global warming. To cut emissions in the U.S. the EPA recently proposed requirements that NEW coal plants use carbon capture and sequestration. This is a technology that takes CO2 produced from coal combustion and pumps it underground. And the EPA is in the process of writing regulations for existing plants, that could also require carbon capture.

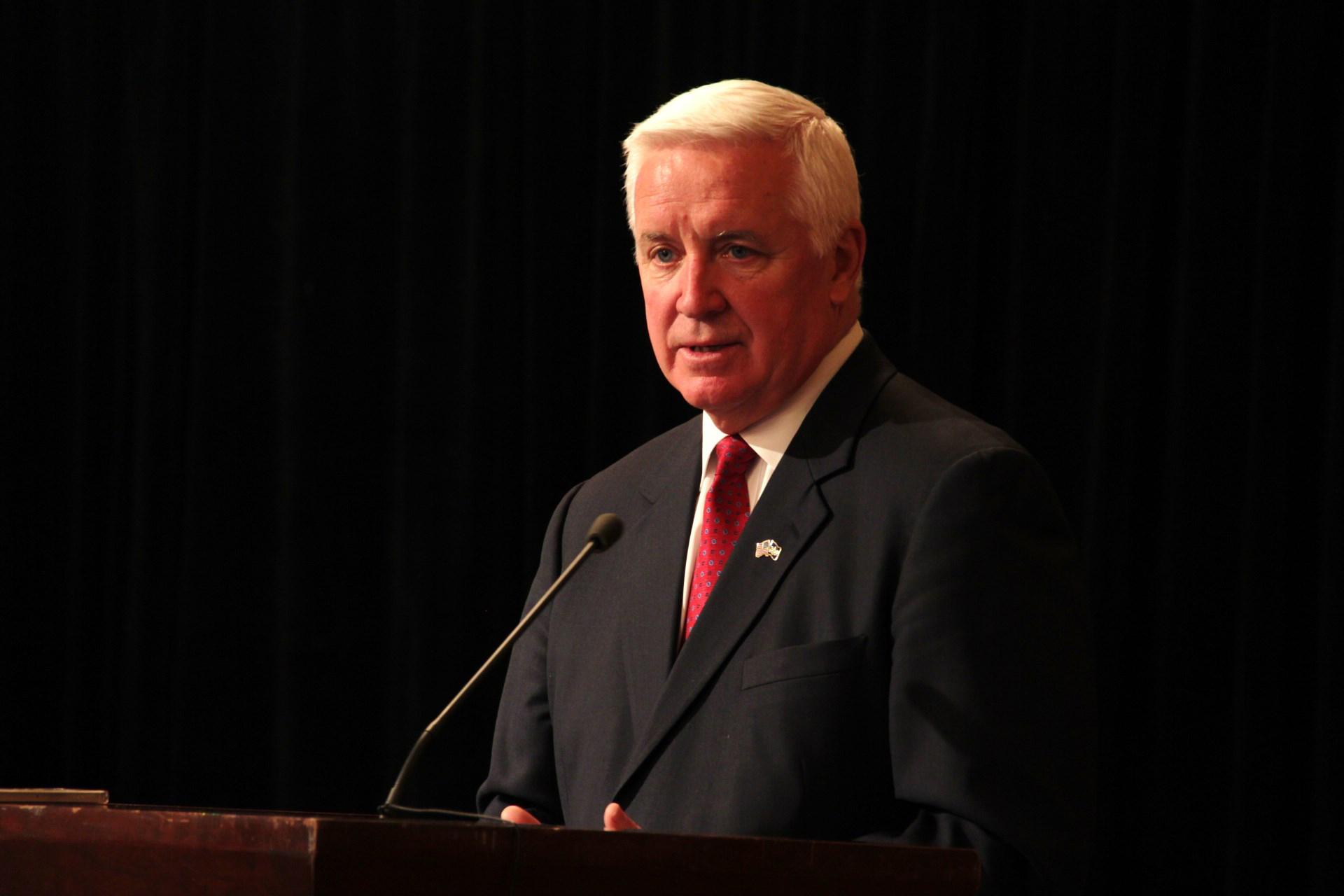

Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett at a coal conference April 22. Corbett says the EPA's carbon regulations will hurt the coal industry. Photo: Reid R. Frazier

This has the coal industry worried. Carbon capture is expensive, and still in its developmental stage. Last summer, FirstEnergy closed two coal-fired power plants in Pennsylvania, saying compliance with current and future environmental regulations would simply cost too much to keep them open. Crooks sees this as part of a trend.

FRAZIER: The reality of it is, this industry would be much more healthy if there weren’t the potential of the regulations.

FRAZIER: This has politicians from coal states—like Pennsylvania Governor Tom Corbett—on the offensive. At a recent coal industry conference, Corbett lashed out against the EPA’s carbon regulations.

CORBETT: We need to work with the industry, and not in opposition to the industry. Simply regulating coal out of existence doesn’t solve anything.

FRAZIER: Corbett told the industry executives in the crowd that he’s confident new technology can reduce coal’s carbon footprint. He invoked the space program, which has developed an international space station and landed a Mars Rover.

CORBETT: If we can do that, you can’t tell me that it’s not possible, given the time and given the right approach and given help from Washington, that we can’t come up with a solution, of cleaner air and getting rid of greenhouse emissions.

FRAZIER: Carbon capture has been around for a while, but there are only a handful of full-scale projects implementing the technology right now. The first carbon capture coal plant in the U.S. is under construction in Mississippi. But that plant is billions over-budget and behind schedule. Carbon capture is energy intensive, and requires multiple steps to get the carbon out of flue gas and into a compressed form that can be pumped underground.

Michael Matuszewski of the Department of Energy’s National Energy and Technology Lab near Pittsburgh, says part of the difficulty with developing the technology is CO2’s chemical makeup--it doesn’t make it very easy to work with.

MATUSZEWSKI: CO2 is a lazy molecule, it doesn’t really want to do a lot chemically, so it’s difficult to manipulate, in that sense.

FRAZIER: All of this would make coal fired-electricity about 40 percent more expensive to produce.

Howard Herzog, an engineer at MIT, says the problem with carbon capture isn’t technology. It’s policy. Without a price on carbon emissions—either through a cap and trade system or a carbon tax, carbon capture isn’t price competitive.

HERZOG: If you do something like put a market price on it—then I think coal has a fighting chance with this technology.

FRAZIER: But putting a price on carbon has been tough in the U.S. A plan in 2010 to pass a cap-and-trade system died in the Senate, and won’t be taken up again anytime soon. Without a price on carbon, the Obama administration has used EPA regulation to try to address climate change. Herzog said he thinks the coal industry could thrive under a carbon tax or cap-and-trade system.

HERZOG: I think coal will do better under a carbon price than it will under the path we’re going down now. Because the path we’re going down now is coal’s in everyone’s target. They’re basically trying to get coal out of the marketplace in any way they can.

FRAZIER: At a conference in Pittsburgh, a few hundred geologists and engineers gathered to compare notes on carbon capture projects all over the world. Philip Jagucki, of Schlumberger Carbon Services, says his company is already pumping compressed carbon dioxide into sandstone at a demonstration project in Illinois.

JAGUCKI: The goal of the project was to inject a million tons of CO2. Right now we’re at 800,000. The project is expected to finish in November, of 2014.

FRAZIER: He thinks the progress at his and other projects means that carbon sequestration isn’t too far off.

JAGUCKI: It’s definitely not far in the future because we’re doing it right now—I mean we know how to do it.

FRAZIER: Jagucki says there are technical aspects that still need to be improved —like pulling CO2 out of the smokestack. Solving these problems is a critical step to help combat climate change, says John Thompson of the Clean Air Task Force.

THOMPSON: Coal is so abundant, it is so inexpensive, it is so energy-dense, that someone is going to use it. The issue isn’t whether we’re going to have coal or not. The issue is whether we’re going to continue to use it in a way that kills the planet. And we have a choice.

FRAZIER: Back in Waynesburg, Tom Crooks says his biggest fear is the transition period it’ll take to fully incorporate carbon capture. He’s afraid the new EPA mandates will give electric generators a reason to stay away from coal.

CROOKS: When we put this what’s really going to amount to is at least a several year pause in power generators trying to figure out what they should do - they’re not going to sit still, they’re going to go ahead and build a gas plant, or they’re going to go ahead and do something else. But whatever it is, it won’t be coal.

CURWOOD: Coal mining engineer Tom Crooks ending that report from Reid Frazier of the public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related link:

Allegheny Front

[MUSIC: Carbon capture: Jenny Scheinman “Bent Nail” from The Littlest Prisoner (Sony Music 2014)]

Deep Seabed Mining

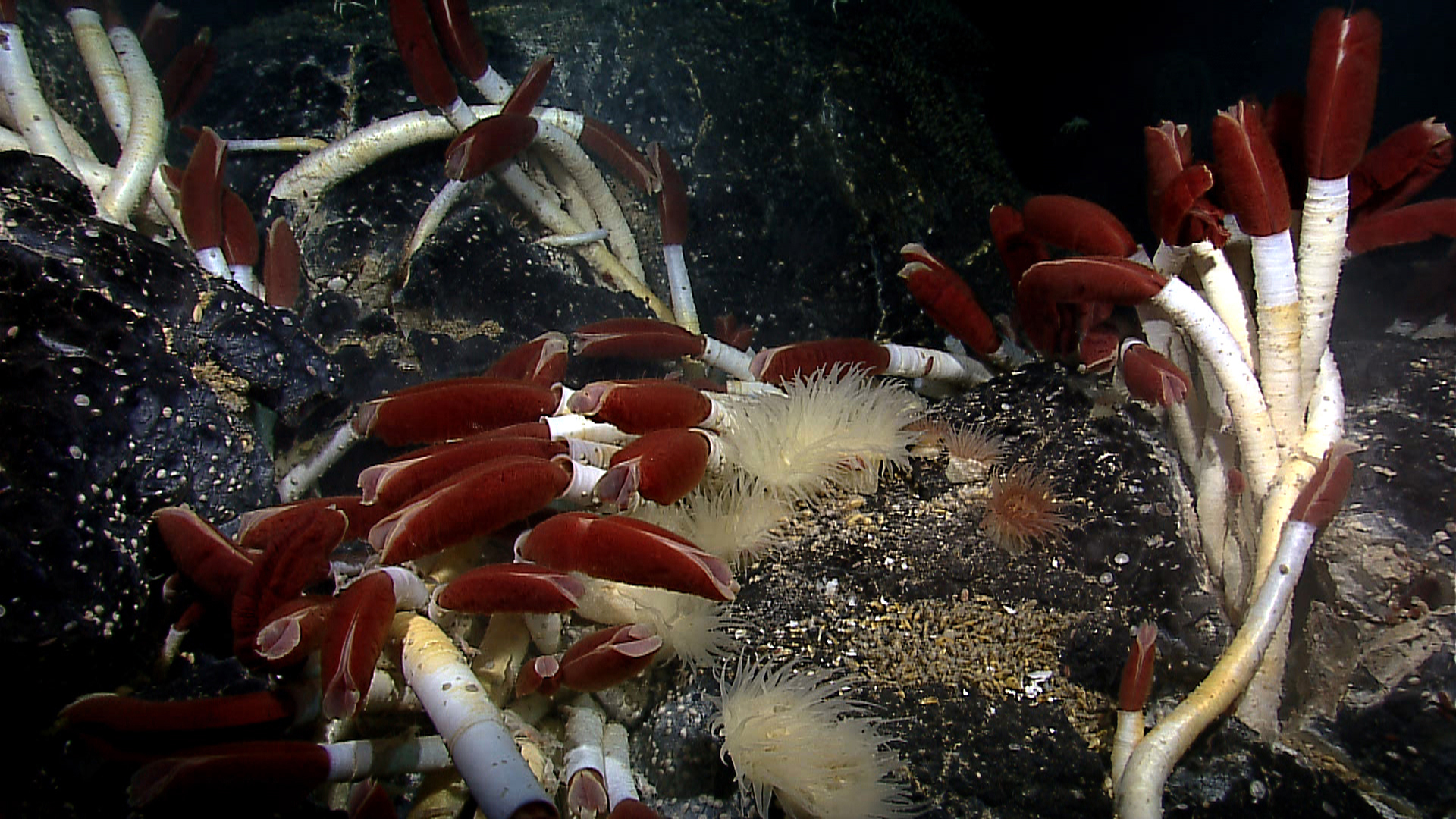

The mineral deposits off Papua New Guinea are located around ocean vents where all sorts of mysterious species flourish, like these tubeworms. (Photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Well, if mining coal from under the earth has ancient roots, mining gold from the deep ocean floor may seem like science fiction. But a Canadian mining company has reached an agreement with Papua New Guinea to do just that. The company, Nautilus Minerals, plans to extract copper, gold, and other valuable metals from the seabed, nearly a mile from the surface.

Many worry that this could be devastating to deep ocean ecosystems, and among them is Richard Page, an oceans' campaigner for Greenpeace. He says miners see a treasure trove at the bottom of the ocean.

PAGE: There are sort of three different kinds of mineral deposits in the deep ocean that industry is getting interested in. There are manganese nodules which are found on the abyssal plain of the deep ocean, there are cobalt crusts - mineral rich crusts - on a lot of the underwater mountains or sea mounts spread throughout the ocean, and then you also get these deep sea vents where there are deposits of metals as well. So, sort of three different deep sea environments that could possibly be exploited in the future.

CURWOOD: And where are some of these largest mineral deposits?

PAGE: A lot of them in the Pacific, but there are other areas in the Atlantic that Russia, for instance, is looking at, and also the Indian Ocean too. So they’re pretty well spread around the world’s oceans.

CURWOOD: Now, why Papua New Guinea?

PAGE: Why Papua New Guinea? Well, because it’s a Pacific island-nation that has a large exclusive economic zone surrounded by water, and has an interesting deep sea geology which has these large deposits of metals around vents, and relatively speaking, these would be technologically feasible to exploit and mine these minerals.

A “dandelion” siphonophore lives around ocean vents (photo: NOAA)

CURWOOD: Now, why would Papua New Guinea agree to something like this?

PAGE: Well, obviously Papua New Guinea is a developing nation and wants to develop economically and this is an opportunity for them. However, it’s also a nation highly dependent on the ocean and so a venture like seabed mining isn’t necessarily supported by all the population in Papua New Guinea, and in fact, there are a lot of community groups who are very worried about the agreement made by the government.

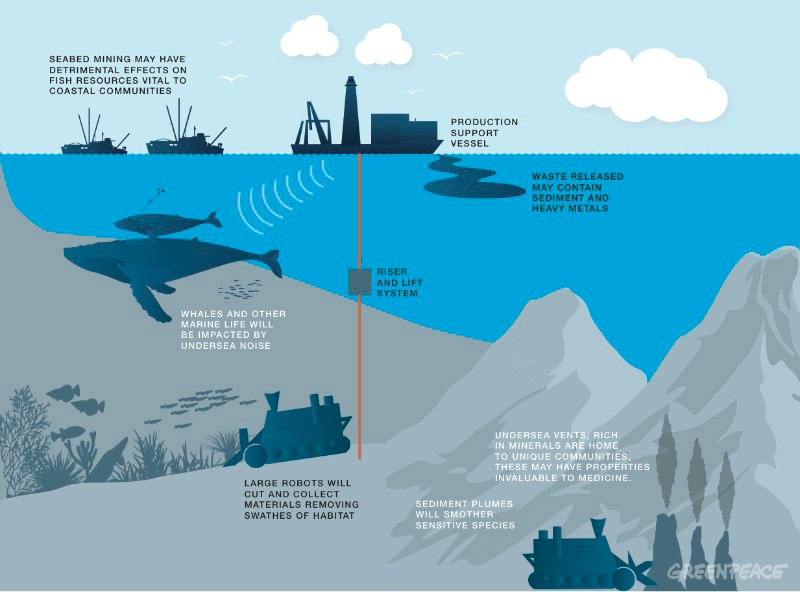

Seabed Mining (Graphic: Greenpeace)

CURWOOD: Now, back in the ’80s and ’90s there was a lot of talk about going for the minerals under the sea. Why is this now back on the table?

PAGE: Yes, so I remember as a boy reading Look and Learn magazine or something similar in saying in the future it would be possible to mine metals and other deep sea minerals. But the technology wasn’t there, and the technology now exists, largely developed from the deep sea oil drilling industry and also the sort of economic conditions are such that there’s a huge demand for precious metals and rare earth metals that are used in all our electronic gear, and so market prices are high, and it’s this combination of demand and the technology, means that there are now companies and countries looking to exploit these minerals.

CURWOOD: Richard, what would the environmental impact of this sort of mining be, do you think?

PAGE: Well, there are lots of potential impacts from deep sea mining. We all know that mining on land has all sorts of environmental impacts. It’s very difficult to contain mine tailings even on land. In the ocean, which, of course, is a fluid environment with all these currents, we can expect widespread pollution, and all sorts of different impacts, everything from smothering of deep sea creatures with sediment, even light pollution in the deep sea will have an impact on all those creatures who have evolved to live in dark environments. So, we’re not sure of the exact impacts, and we may even be destroying or impacting ecosystems that we know very little about. I mean, we know less about the deep sea than we know about the surface of the moon. So it is a big experiment, and quite what those impacts will be we don’t know, which is why Greenpeace is calling for protection measures to be put in place before you ever start an experiment of this kind.

Richard Page (photo: Greenpeace)

CURWOOD: What kind of protection measures would you like to see?

PAGE: Well, our oceans are massively under-protected. Less than three percent of the world’s oceans are either marine protected areas or ocean sanctuaries, and if we’re looking at waters beyond national boundaries then it’s less than one percent. And scientists and governments have all agreed we need to put a global network of ocean sanctuaries in place, they made agreements under the Convention on Biological Diversity and World Summit on Sustainable Development, but they actually haven’t taken the action. What we’re saying is we need to get those kind of measures in place before we start adding to the stresses being put on ocean ecosystems.

CURWOOD: As I understand it, the International Seabed Authority is in charge of allowing people to explore for minerals in the bottom of the ocean. How effective this that organization, do you think?

PAGE: Well, the International Seabed Authority was formed some time ago, before the industry was really technologically possible, and at a time when we knew far less about the oceans than we do now. And so I would say it isn’t really fit for purpose. There are rules it has set which will apply to seabed mining operations in international waters, but those rules don’t take into account what is happening in the water column and other activities. And what we really need is a UN agreement that ties all these different elements together, so we start managing the oceans in a holistic way, so we don’t consider fisheries separate of seabed mining. These impacts may be cumulative. They may be synergistic. We need an overarching framework, if you’d like, to manage our activities under the sea.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think this deal between Nautilus Minerals and Papua New Guinea could be the start of a trend?

PAGE: It’s absolutely the start of a trend. There are lots of places around the world in the deep ocean where such deposits exist, and if this venture is successful then we can expect to see an explosion of deep sea mining. We’ve got something like 19 licenses, I believe, in international waters, and there are other countries and companies looking to do it within the economic zone of very specific islands at the moment. So the Papua New Guinea venture is really the tip of the iceberg, I think.

CURWOOD: Richard Page is an ocean campaigner for Greenpeace. Thanks so much for joining us today.

PAGE: Many thanks.

Related links:

- Read about deep sea mining on the Greenpeace website

- Nautilus Minerals explains its seabed mining goals and techniques

Gold Mining & Child Labor

In the small farming village of Tawig, Philippines, an extended family group of 16 miners has set up operations in a grove of nipa palms. The mining tunnels look like mud puddles but are as much as 40 feet deep. (Photo: Larry C. Price/ Center for Investigative Journalism)

CURWOOD: If mining the deep sea for valuable metals is at the cutting edge of underwater mining technology, then some gold mining in the Philippines could demonstrate one of the worst examples of homegrown, unsafe and unregulated methods. Children as young as five years old are working in a particularly dangerous form of shallow water gold mining called compressor mining. Richard Paddock wrote about compressor mining as a Contributing Editor for the Center for Investigative Reporting, and he joins me on the line now to explain what it's all about. Welcome to the program.

PADDOCK: Thanks very much.

CURWOOD: Rick, first of all describe for me, how does this compressor mining thing work?

PADDOCK: So, in order to find gold that is underground, these miners will dig a hole into a rice paddy or into the bottom of a waterway such as a shallow bay, and they’ll dig a hole straight down and start passing up buckets of mud to a partner above.

CURWOOD: Why do you call it a compressor?

A miner sinks below the muddy water of Mambulao Bay to begin a dive for ore that can last for hours. Breathing air supplied through a tube from a simple air compressor, the miner’s job is to fill bucket after bucket with soil for a fellow miner to haul to the surface. (Photo: Larry C. Price/ Center for Investigative Journalism)

PADDOCK: In order to be underground and underwater for long periods of time, perhaps three or four hours, they’ll breathe through a tube that is connected to a small compressor often made out of a beer keg. That compressor is connected to a small motor, diesel motor that powers the compressor. So they’ll go into the hole where they cannot see a thing - it’s just muddy water - and dig down as much as 40 or 60 feet. And when they get to a layer of soil where they believe there’s gold in the sediment, they’ll start digging sideways. Meanwhile, a partner up on top is hauling up bucket after bucket of this soil, and dumping it out for others to work with and extract the gold.

CURWOOD: And now, once they get the flecks of gold what happens then?

Jonathon Ramorez, 12, uses a wide wooden pan to separate gold from sediment in the Philippines’ Mambulao Bay. A plastic bag holds a small lump of mercury and gold, the product of the mining crew’s work for the day. (Photo: Larry C. Price/ Center for Investigative Journalism)

PADDOCK: They’ll take that, and they’ll combine it with mercury. Gold binds to mercury. And they’ll take that and process it a number of times until they’ve got as much gold and mercury together as they can. Then they will squeeze that out - it’s still sort of a liquid form - they’ll squeeze it out and try to solidify it into a lump that’s sometimes known as an amalgam. Then they’ll take that and burn it using a blowtorch. When they heat it up, the mercury is vaporized, leaving just the gold. Mercury vapors are very hazardous, and that’s one of the big problems with this form of mining.

CURWOOD: It sounds like really dangerous work, Rick.

PADDOCK: There are a number of dangerous hazards. The one they fear most is the collapse of the soil while they’re in the hole. Other dangers include bacteria that’s in the water. It can be leptospirosis or various parasites that they can pick up. They can also get nitrogen bubbles in their lungs, sometimes the compressor hose itself has pollutants - oil or carbon dioxide - and that in some cases can be fatal. The burning of the mercury is one of the biggest hazards because mercury is a toxin known to cause brain damage or reproductive harm. These hazards are especially great for children whose bodies are still developing. Some children as young as 13 are participating in this diving, and it takes a real toll on them as they’re growing.

CURWOOD: So, you say a lot of people doing this work are children...how exactly do they get involved?

PADDOCK: Well, a lot of these are family operations, an extended family might find that their best way of making a living is to work in a rice paddy, for example, and the whole family participates. It may be that the older men start out as the divers, the divers make more. So for boys and young men, this can be an appealing way to make a living. I should say that living is not great, they might make $5 a day, or perhaps even more than $20 on a great day, but there are also a lot of days when they make nothing. These people are fairly desperate to find some way to earn money and they subject themselves to great risk in doing so.

CURWOOD: How young are the children involved in this operation?

PADDOCK: I saw a five-year-old who was helping out his family by fetching water and moving dirt around, but the serious work is done by boys and girls 13 and above.

CURWOOD: Girls?

PADDOCK: I saw one girl who was panning for hours at Mamburao Bay. I don’t think she was the only one.

CURWOOD: Now, when you talk to the miners in the Philippines, how concerned were they about the possible health effects of mercury exposure?

PADDOCK: Well, I talked to one boy who was 16 who was burning mercury. He’s the one who told me he had started at eight years old. He said that no one had told him before that mercury vapors were hazardous, and he was a little reluctant to believe me when I outlined some of the dangers. The more pressing problem for them is how they’re going to buy food, how they’re going to eat. They’re not really thinking in a very long term way.

CURWOOD: So, how many folks do you think are involved in this enterprise?

PADDOCK: It’s a good question. One location we saw about 40 rafts on a bay, and each raft had more than 10 workers, so there’s at least 400 right there, probably a few thousand scattered around that province and other parts of the Philippines.

CURWOOD: So, let’s say as a consumer, someone’s on the market for a gold ring, what way if any is there to know if a potential purchase is coming from this type of gold mine?

PADDOCK: I think it’s really impossible to know. Much of the gold from the Philippines is sold to brokers and it eventually ends up in China. If it enters the worldwide gold supply, it could easily come to the United States, there could be a small percentage of gold in the United States that comes from the Philippines but there’s no way to trace it because once it enters the world gold supply it’s unidentifiable.

CURWOOD: Richard Paddock is a Contributing Editor for the Center for Investigative Reporting. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today, Rick.

PADDOCK: Thank you very much.

Related link:

Center for Investigative Journalism

[MUSIC: Gil Evans “La Nevada” from Out Of The Cool (Impulse Records 1961)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...nature’s ingenuity and the mystery of a bird called Wilson’s snipe.

That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for the coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Gil Evans “Up From The Skies” from Plays The Music Of Jimi Hendrix (RCA Records 1976)]

CO2 Can Reduce Food Value

Wheat crops are less nutritious when grown in a high carbon dioxide environment. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. A study published in the journal Nature finds that staple foods can lose key nutrients when they're grown in air increasingly rich in carbon dioxide. Researchers cultivated 41 different varieties of these crops on three continents to discover how they might be affected by the expected increase of CO2 in coming decades. Samuel Myers is a physician and research scientist in the Department of Environmental Health at Harvard University. He led the study, and joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MYERS: Thanks so much. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: So what crops did you look at for this study, and why did you choose them?

MYERS: Well, we looked at a fairly wide variety of crops that included rice, wheat, soybeans, maize or corn, field peas, and sorghum. And we chose them because they represent a fairly broad slice of different plant functional groups that are central to human nutrition around the world.

CURWOOD: It’s what a lot of people eat, in other words.

MYERS: Yes.

Soy is one of the key agricultural crops researchers tested for nutrition content when grown in a high carbon dioxide environment. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: Now, you grew these study crops in an environment that had elevated levels of CO2, carbon dioxide. How much CO2 are we talking about, and how did you do this?

MYERS: Well, so the levels we’re talking about are 550 parts per million. And that’s essentially where the world is going to be by about 2050, there’s very little debate about that. The way we did it is by using what’s called FACE methodology which stands for Free Air Carbon Dioxide Enrichment. Essentially, what you have is open-field conditions where it looks like any other agricultural field except there’s a ring of carbon-dioxide emitting jets, and in the center of the ring is a sensor which tells you the wind direction as well as the carbon dioxide concentration, and when the CO2 falls below your prescribed level the upwind emitters release some additional carbon dioxide.

CURWOOD: So, what were your findings? How did these food crops stack up when they were grown in this high carbon-dioxide environment?

MYERS: So what we found is that rising concentrations of carbon dioxide really threaten global human nutrition by significantly reducing the levels of important nutrients for human health in all of these crops. In particular we found significant reductions in zinc, iron, and protein in C3 crops which are grains like rice and wheat, and we found significant reductions in zinc and iron but smaller reductions in protein in the C3 legumes like soybeans and field peas.

CURWOOD: How significant is that reduction in zinc, iron and protein?

MYERS: Statistically it was very highly significant, and in public health terms, I think it’s also very significant. We know that there are roughly two billion people around the world who are suffering from zinc and iron deficiencies today. Without adequate zinc, our immune systems don’t function appropriately. and so we get an increase in really in child mortality from diseases like pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria, measles, and other infectious diseases. For iron deficiency it’s more complex, so we experience iron deficiency as anemia. The risk of maternal mortality rises quite sharply, and there are also impacts on things like IQ and work productivity. When you combine all of those different kinds of effects for both iron and zinc deficiencies together, it’s estimated that we lose about 63 million life years annually from those nutrient deficiencies today.

CURWOOD: How about different cultivars that might be able to do better in a high-carbon dioxide environment?

Sorghum is a key agricultural crop around the world. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

MYERS: We did actually look at 18 different rice cultivars, and we found that in fact there were some rice cultivars that were more impacted by rising CO2 than others and it may be possible to breed rice cultivars for reduced sensitivity to carbon dioxide, and conceivably other crops as well.

CURWOOD: Now, what about the discussions that carbon dioxide acts something like a fertilizer for plants, causing them to grow bigger, stronger, faster. What does your research say about those views?

MYERS: There is data that suggests that there’s a small fertilization effect of carbon dioxide that can increase yields although in the context of adequate irrigation, there’s really not that much of a CO2 fertilization effect. I guess what I would say is that over the next 40 years, we need to double global food production in order to keep up with demand, so simply saying we’re going to increase intake is somewhat optimistic given the challenges of even maintaining caloric intake over the next 40 years. The other thing I would say is that if you and I were to simply start increasing our intake of food by five or ten percent in order to offset the reductions in nutrients, we would both be morbidly obese in a matter of months, and so we can’t simply eat more food in order to maintain the same nutrient intake.

CURWOOD: So, it would seem that we’re set to have the 550 parts per million of CO2 over the next 40 years, at the same time we’re expected to see world population go up from our seven billion to nine billion, and the warmer planet likely to have less arable land. How much does this confluence of rather difficult things concern you?

MYERS: Well, I think it’s obviously deeply concerning. We are essentially transforming all the natural systems on the planet in a way that is both pervasive and accelerated. And that transformation will lead to a host of surprises, and it’s very difficult to anticipate how these environmental changes will sort of ripple through ecological systems and ultimately impact our own health and well-being and all we can really say with certainty is that we’ll be surprised many times in the future. To me, this research is an example of one of those surprises.

CURWOOD: Sam Myers is a Physician and Research scientist in the Department of Environmental Health at the Harvard School of Public Health. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Dr. Myers.

MYERS: Thanks so much for your interest.

Related link:

Increasing CO2 Threatens Nutrition

[MUSIC: Rory Gallagher “On The Boards” from On The Boards (Polydor Records 1971)]

Beyond the Headlines

Donald Trump’s golf course in County Clare is at risk from sea level rise (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It’s time once again to head beyond the headlines for some curious and unexpected news in the company of Peter Dykstra. He's the publisher of Environmental Health News, EHN.org and DailyClimate org, and he's on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Well, you’ve heard a bit from Donald Trump, when he shares his views on climate change, right?

CURWOOD: Yes, in his typically restrained and modest way, Mr. Trump has let the world know climate change isn’t real.

DYKSTRA: Exactly. He made the talk show rounds this winter, saying that the snow that fell on Manhattan’s Trump Tower was evidence enough that the world is not warming, but even in the charmed life of the Donald, there’s a fly in the ointment: something’s been causing his seaside golf resort in County Clare, Ireland, to start to tumble into the sea. The Trump Doonbeg golf course – you know, everything’s got to have the name “Trump” in it…

CURWOOD: Of course…

DYKSTRA: ….it suffered about two million dollars in winter storm damage, and they’re looking to build three seawalls to make sure this doesn’t happen again. Now the Donald isn’t blaming anyone or anything for this, certainly not climate change and certainly not increasingly extreme weather.

CURWOOD: And he had a big battle against a proposed windfarm off the coast of his Scottish Golf Resort, too, right?

DYKSTRA: Yes, and he lost his most recent legal appeal on that one, but with this Irish case, he’s broken new ground.

CURWOOD: What would that be?

DYKSTRA: There’s a story in the current Golf Digest about climate change and Donald Trump and golf courses. I’m feeling we’re soon going to see a remake of “Caddyshack” with Donald Trump and a climate change theme.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I want to see that one. Hey, what else do you have this week?

Donald Trump (photo: David Shankbone, Creative Commons 3.0)

DYKSTRA: If you asked most folks which world city has the dirtiest air, they might say Beijing, right?

CURWOOD: Yeah.

DYKSTRA: I probably would have, too, but for a new assessment of urban air pollution from the World Health Organization. Not only does Beijing not show up among the top 20 cities for air pollution, but if Beijing were a city in India, it would be in 27th place in India alone.

CURWOOD: Whoa, there are 26 cities with worse air pollution than Beijing, just in India?

DYKSTRA: Yes. The study focused on particulate matter, soot, produced by factories, vehicle exhausts, cook-stoves and other sources. The particulates are the reason that you see many pictures from western media of people walking the streets in gas masks.

CURWOOD: And I suspect that’s why we’re always hearing about Beijing, because that’s where the western media tend to be based.

DYKSTRA: Yes, the western media live and breathe in places like Beijing, but breathing’s just not like it used to be back home. So Beijing is an also-ran on this list, behind some cities in China as well as many in India and Karachi, Pakistan. Delhi, India, is number one though.

CURWOOD: And what about US cities?

DYKSTRA: They’re off the charts completely. But in this case, “off the charts”, if you’re talking about the world’s most air-polluted cities is a good thing. There are air pollution problems here, obviously, but nothing like in the booming economies of India and China, with a huge influx of car traffic, factory smoke, coal-based electric power as well as coal cookstoves that are used in homes.

CURWOOD: And on that happy note, what’s on the calendar this week?

DYKSTRA: You know, last week we mentioned the oil sands pipeline company whose pitch said that pipeline spills are good for the local economy? Well, here’s an example of how that kind of thing can be outrageous but can be true at the same time. It was 25 years ago this week, the federal EPA, the energy department and the state of Washington launched the largest environmental cleanup in history at the Hanford nuclear weapons production site. It’s been going on for a quarter century, and is still projected to last another half century and cost another $100 billion.

CURWOOD: So a huge contamination, and hundreds of billions of dollars to clean it up. What’s the plus side of this again, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s a plus side if you live and work in the Tri-Cities in the High Desert region of Washington State. That area was a sleepy ranching and farming area along the Columbia River until the Manhattan Project and then the Cold War came along. After that, the cities of Pasco, Kennewick, and Richland exploded – no pun intended – and they thought the end of the Cold War years might be their end too, but the Tri-Cities are going to thrive by cleaning up the plutonium mess from their first 50 years, at least two billion a year in Federal funds until I’m in my mid one hundred and tens.

CURWOOD: I’ll check back with you then, Peter! Peter Dykstra is Publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Donald Trump builds a sea wall

- Indian pollution crisis

- Cost of Hanford cleanup tops 100 billion

[MUSIC: Various Artists/Najee “Black Man” from Blue Note Plays Stevie Wonder (Blue Note Records 2004)]

The Mysterious Sound Of Snipe

CURWOOD: In the spring, many Americans long to head out to the wild country, maybe to one of America’s glorious National parks. Anyone lucky enough to get to Yellowstone in spring will find its grassy meadows flooded and marshy. And as the dusk falls, a peculiar sound rises out of the gathering dark. What makes this sound is surprising enough, but how it's produced is truly extraordinary, as producer Jennifer Jerrett discovered when a park birding expert revealed the mystery.

DUFFY: I'm Katy Duffy. I'm the Interpretive Planner for Yellowstone National Park. I've been hooked on birds, obsessed with them, for 40 years [LAUGHS]. I'm an addicted birder.

[THE STACCATO, RISING-PITCH SOUNDS OF A WILSON'S SNIPE'S WINNOWING FLIGHT]

DUFFY: So it's not really a vocalization. It's not a call. What you heard is a Wilson's snipe doing it's territorial sound, but it's made with its wings and its tail.

[MORE WINNOWING FLIGHT SOUNDS]

DUFFY: What male Wilson's snipe do this time of the year - in the spring - they do this flight - these winnowing flights is what they're called. So each time they flap their wings it pushes air through the stiff outer tail feathers and it makes that "woo woo woo woo woo" kind of sound.

[WINNOWING SOUNDS]

DUFFY: They make that sound to establish their nesting territory and attract a female. It's a courtship sound.

[WINNOWING SOUNDS]

DUFFY: I've had people describe it to me in various ways. They sometimes think it's an owl. They're not sure what it is. Some people think it's a motor noise...

[WINNOWING SOUNDS]

DUFFY: …It's a metallic sound. It's going on over your head so it's really hard to pinpoint where the bird is. Plus the bird's tiny. It's about the size of a robin. They're actually very delicately beautiful when you get to see them up close. It's a really neat bird. It's a bizarre little bird.

[WINNOWING SOUND; SOUNDS OF DUCKS IN THE BACKGROUND]

DUFFY: It's eerie. It's strange because it's often happening at dusk or at night, so it's coming out of the darkness. That's what's fascinating is that it happens at a time that's sort of magical. I always think of dusk as magical because almost anything can happen. Your imagination kind of goes wild and when you hear sounds out of this, oh, semi-darkness, they seem ethereal... otherworldly... wild... and they are. And it's neat. We use other senses. I love when we use more than just our eyes.

[WINNOWING SOUNDS]

Yellowstone Interpretative Planner, Katy Duffy. The notice board announces the time of the next eruption of Old Faithful. (Yellowstone National Park)

CURWOOD: Jennifer Jerrett produced this audio postcard from Yellowstone National Park.

[MUSIC: Sun Ra “Fate In A Pleasant Mood” from Fate In A Pleasant Mood (Savoy Records 1961)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. We welcome Lauren Hinkel to the team this week, and bid a grateful farewell to our hard-working interns Clairissa Baker and Catalina Pire-Schmidt. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stephenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth