May 23, 2014

Air Date: May 23, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Flooding In The Balkans

View the page for this story

A storm system recently inundated the Eastern European states of Bosnia, Serbia, and Croatia with three months worth of rain in just three days. Journalist Sanja Jovanovic tells host Steve Curwood that the rain caused unprecedented floods and landslides, and unearthed landmines left behind from war in the 1990s. (05:35)

The Wetland that Saved Highway 101

View the page for this story

Every winter on Oregon’s north coast heavy rains cause the Necanicum River to flood part of Highway 101. But as Earthfix reporter Cassandra Profita explains, a local land conservancy has restored a field to a wetland to keep the highway dry. (05:25)

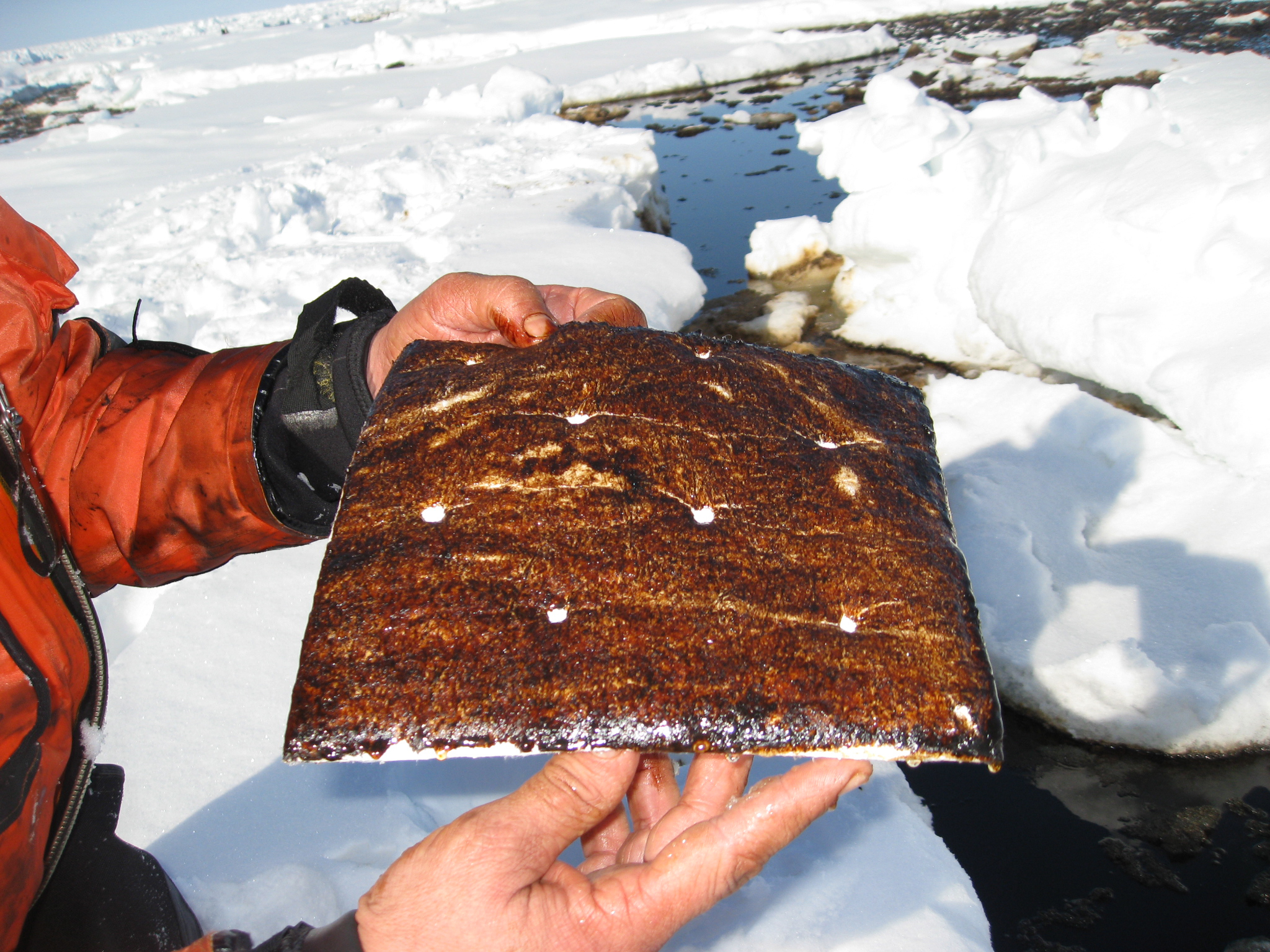

Unprepared for Arctic Oil

View the page for this story

As sea ice melts, the arctic is increasingly a target for oil exploration. But as scientist Mark Reed of the Norwegian Research Center SINTEF tells host Steve Curwood, there's a lack of infrastructure in place to clean up an oil spill in the fragile arctic ecosystem. (05:50)

Arctic Explorers

/ Emily CorwinView the page for this story

Few navigators have dared to travel the treacherous waters of Northern Canada that marooned Henry Hudson some 400 years ago. But as Mind Open Media’s Emily Corwin reports, a storyteller and a climate scientist have both taken on Arctic exploration as an interest and a challenge. (11:30)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

In this week’s voyage beyond the headlines Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about game show hosts curious pattern of denying climate change, and remembers a venerable and important piece of environmental legislation, the Lacey Act. (04:45)

Springtime Birding With David Sibley

View the page for this story

As they head north, migratory birds search out pit-stops on their trip, and local birds are eager to breed. Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord Massachusetts is perfect for both, and a perfect plact for host Steve Curwood to meet up with David Sibley. They listen to birds and discuss the second edition of Sibley’s popular and erudite Guide to Birds. (15:00)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Sanja Jovanovic, Mark Reed, David Sibley

REPORTER: Cassandra Profita, Emily Corwin, Peter Dykstra,

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Extreme weather means three months worth of rain falls in three days to inundate the Balkans.

JOVANOVIC: It looks like hell. I saw it on TV in other countries before but I never imagined it's going to happen in my country. Imagine seeing a building and you can only see from the fifth floor to the top. Rescuers are out there in their boats literally cruising between the roofs.

CURWOOD: Trying to cope with historic floods. Also, heading out to the meadows as the sun rises with a top birder to celebrate the chorus of new arrivals.

SIBLEY: These migrants, they're near their breeding grounds here. They're heading north, they're just about to enter this phase of life where they'll find a mate, they'll set up a territory, raise young, and they just can't control themselves. They sing at dawn.

CURWOOD: Bird song and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Flooding In The Balkans

Flooding in Bosnia (Ian Bancroft)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The heaviest rainfall and worst flooding in memory still has Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia reeling, with dozens of people dead and hundreds of thousands displaced from their homes. It’s the latest extreme weather event in an extreme weather year; according to NASA last month was the second warmest April ever recorded worldwide. To get a sense of what’s happening on the ground in the Balkans, we called up Sanja Jovanovic, a journalist based in Novi Sad, Serbia, who's been volunteering to help the flood victims.

JOVANOVIC: It looks like hell. I’ve never seen anything like it before. I saw it on TV in other countries before, but I never imagined it’s going to happen in my country. Officials claim the size of the disaster hasn’t been seen since the records begun. A huge low pressure cloud system hovered over the region, and it said it shed three months worth of rainfall in all of three days. We’re so shocked. Imagine seeing a building, and you can only see from the fifth floor to the top. Rescuers are out there in their boats literally cruising between the roofs. Some say they are stranded on car roofs. People are being evacuated constantly. According to the latest information coming from the Ministry of Internal Affairs, around 31,000 people have been evacuated from the flooded areas in Serbia, cities like Obrenovac and Paracin suffered most and were completely submerged in water.

CURWOOD: What kind of warning did people get that there was going to be serious flooding?

JOVANOVIC: Well, on the 15th of May the government declared an emergency situation. People were told they were going to be evacuated. At this point, there was a political problem, bearing in mind some politicians asked the people not to leave their homes, then in the last minute they were told they were going to be evacuated. So, basically, yep, that’s it when it comes to that.

Roads in Serbia are littered with debris moved by floodwaters. (Photo: Sanja Javanovic)

CURWOOD: In order words it was chaos.

JOVANOVIC: Exactly.

CURWOOD: What’s happened to the livestock, the animals? A lot of farming in that area.

JOVANOVIC: Well, when it comes to farming, some animals were left dead and we’ve got carcasses floating around, so we still don’t know what’s going to happen with that one once the situation stabilizes, but there are people in the field collecting the carcasses, and people are said to unleash their dogs and just let them float around.

Flooding in Bosnia (photo: Ian Bancroft)

CURWOOD: Wow. Now I read that the torrential rain caused upwards of 3,000 landslides in the region, 1,000 in Serbia, 2,000 in Bosnia. What’s going on? Is it just erosion? Or were the mountains previously deforested and more susceptible to landslides?

JOVANOVIC: Mmm hmm. I wouldn’t say it’s only a matter of deforestation as we’ve got landslides in the mountains, which are well forested as well. I would assume that deforestation is partially to blame, but I think that landslides are happening mostly due to the huge amount of water that has fallen in such a short space of time, which has triggered the landslides regardless of the level of deforestation in the given area. In addition, we’ve got landslides in cities where the land is susceptible to erosion.

CURWOOD: When you talk to the average person about all of this rain and flooding, what do they think might be behind it? What do they mention in terms of climate change perhaps influencing the weather?

JOVANOVIC: I shall say the average person is influenced by various media and what the church says, which is not actually connected to the climate change which the majority of the population does not even think about. I really hope that people after this will think more on climate change, and focus on dealing with that problem.

CURWOOD: So how much in terms of chemical manufacturing industry is there which would have led to chemicals being released?

JOVANOVIC: Well, it is a problem, but they are still trying to protect some of the factories that are dealing with the chemicals but it’s not just the factories, it is also the fact that Serbia doesn’t have a proper way of keeping medical waste. I guess it’s all in the water and in the soil at this point. And also, many people have a lot of chemicals in their homes and a lot of medicines and it’s all now in the soil and in the water. In addition, the weather forecasts says it’s going to be really sunny the following days, and we are concerned, as in after a major disaster this may lead to epidemics.

CURWOOD: So, much of the Balkans was a war zone not so long ago, early ’90s, and from what I understand, some of the legacies to that war are literally being unearthed by the water. Can you tell me about that?

JOVANOVIC: Well, we have the problem with the landmines so far. The story about the landmines dates from the ’90s. At this point, sadly, I don’t think anyone knows where the mines might be. Even the signs pointing where the mines are are now gone. The water took that. I guess the officials are waiting for the water levels to go down and then they will try to locate them.

CURWOOD: But wait, that means that people move about after the floods...they could be stepping on landmines?

JOVANOVIC: It is true. Sadly, yes, that is true.

CURWOOD: It’s getting on to two decades now that the war has been over. What kind of help are people giving across borders? Are Bosnians helping Serbs? Are Serbs helping Croatians? How are things working along those lines?

JOVANOVIC: People are people. People who know that there are other people who are in need, they are helping. We are also helping Bosnia, we’re helping other affected countries. There are no borders now. Everyone is there to help.

CURWOOD: Sanja Jovanovic is a journalist based in Novi Sad, Serbia. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JOVANOVIC: Thank you for having me.

Related link:

Al Jazeera has more photos of the devastating floods

The Wetland that Saved Highway 101

CURWOOD: The Balkans aren't the only part of Europe that's been drowned under unprecedented rains. Earlier this year record floods in parts of the UK inundated villages and farmland for weeks. The atmosphere can hold more water vapor as it warms, and what goes up, must eventually come down, often in the form of torrential rains that don't let up. Climate change is changing the business of flood control.

In Holland, where masterful engineering has protected low-lying land for centuries, planners are now looking to give some areas back to the sea. And the idea seems to be catching on in places in the US. On Oregon's north coast, there’s an infamous stretch of Highway 101 where every winter, during heavy rains, the Necanicum River spills out over its banks and swallows the road just south of Seaside. This happens at least once and up to seven times a year. But this year, as Cassandra Profita of the public radio collaborative EarthFix explains, highway officials have teamed up with a local landowner to use a nearby wetland as a natural sponge for floodwater.

Casey Corkrey plants willow trees in the pasture. (Photo: Cassandra Profita)

[VOICE ON VIDEO: “HERE WE GO, THROUGH THE WATER!”]

PROFITA: You can see the extent of the Highway 101 flooding in YouTube videos made by people driving through it. In this one, the car radio plays a local commercial while a woman in the front passenger seat films the view from the dashboard. It’s all water.

[VOICE ON VIDEO: “OH, MY GOD. UM. THIS IS A LOT WORSE THAN I THOUGHT IT WAS GOING TO BE.”]

PROFITA: At one point, she turns the camera to the right. The water level is almost as high as the passenger window.

[VOICE ON VIDEO: “WE ARE IN A LAKE.”]

PROFITA: Larry McKinley is the regional manager for the Oregon Department of Transportation. He says sometimes crossing the lake is actually too dangerous. His agency is in charge of closing the highway to cars that aren't big enough to make it across. Otherwise, they could float away when flood waters reach a foot or higher.

A restoration project last year allowed this wetland to flood while an infamous stretch of Highway 101 stayed dry this winter. (Credit: Courtesy of North Coast Land Conservancy)

MCKINLEY: When you get that flowing water – and it would move very quickly across there – it would actually pick them up off their wheels and they’d start moving onto the other side. And there’s a very deep ditch on the other side.

PROFITA: Studies identified two culprits for the flooding problem. One: the highway was built in the Necanicum River floodplain. And two: the rest of the floodplain was walled off by a berm – a four-foot mound of dirt that trapped the river against the highway for about a mile.

Engineers presented three solutions. Two of them involved raising the highway above the floodwater. The third, much cheaper option, was to remove the berm and let the flood water spread out over 100 acres of pasture land on the other side.

A restoration project last year allowed this wetland to flood while an infamous stretch of Highway 101 stayed dry this winter. (Photo: North Coast Land Conservanc7)

The best part of that plan? The owner of the pasture actually wanted it to flood.

VOELKE: We said bring it on. We’ll take as many flood waters as you want to give us.

PROFITA: That’s Katie Voelke. She’s the director of the North Coast Land Conservancy. The group manages 3,000 acres of habitat in the region – including 300 acres along Highway 101. Turns out, she was dying to turn that pasture back into what it used to be.

VOELKE: Way back when, what it used to look like was a forest. It was a forested wetland swamp. Out here on the coast a forested wetland was very common as a historic habitat.

PROFITA: As transportation officials weighed their options for fixing the highway, she assured them that, yes, really, they could – and should – flood her property.

VOELKE: I was like, ‘Don’t be afraid. I know you never do this, but we want you to.'

PROFITA: For Voelke, floodwater is like a habitat delivery service. It carries nutrients that feed native plants and nurture the base of the food chain.

VOELKE: It's like augmenting the soils. Bringing the compost to the garden.

PROFITA: To turn a cow pasture back into a natural wetland, Voelke says, her land needs those nutrients. But taking out a mile-long berm was too big a job for her land trust. A plan snapped into place when ODOT realized it could use Voelke’s flooded property as a wetland mitigation bank. That’s a place where the agency gets credit for restoring wetland habitat. Later, it can cash in that credit to offset damage to wetlands from roadwork in the area.

Allowing the Necanicum River to flood this pasture kept Highway 101 dry this winter. (Photo: Cassandra Profita)

McKinley says one day he got a call from one of ODOT's wetland mitigation specialists.

MCKINLEY: They had money to do wetland mitigation banking. At that point the light went on. I said, 'We've got a site out here.'

PROFITA: So, last summer, ODOT paid to remove almost a mile of berm along the highway and start turning the pasture into a wetland. And this winter, everyone’s been watching to see whether the river’s floodwater would now flow into the pasture instead of covering the highway.

McKinley says that’s exactly what’s happened.

MCKINLEY: This year we’ve had two flood events. The last one, in February, was a very major high water event, and in the area of Circle Creek Campground where it’s always flooded before, it didn’t flood this time.

PROFITA: Voelke compares the solution with allowing the river to fill a bathtub instead of a sink during high water.

VOELKE: So, it’s the same amount of water, the same power, but you have a bigger bathtub. That’s what our floodplain is.

PROFITA: Mike Morgan is the mayor of Cannon Beach, the next town south of Seaside on the coast. During heavy rains in February, he drove up and watched as the pasture flooded while the highway stayed dry. He says for him it drives home the idea that people could let nature handle flood control more often.

MORGAN: I think the lesson in the long run for engineers who like to bury pipes and install pumps is that natural engineering really works.

PROFITA: As part of the project, workers have planted thousands of trees in the pasture this spring. When they grow up, Voelke says, they’ll make the wetland even more valuable to highway drivers through what she calls vertical water storage. I’m Cassandra Profita reporting.

CURWOOD: Cassandra Profita reports for the public media collaborative EarthFix.

Related link:

Listen to this and other stories from the Pacific Northwest on the EarthFix website

[MUSIC: Marc Ribot “Fuego” from Party Intellectuals (Pi Records 2008)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the most rugged conditions on Earth and the relentless quest for oil. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Sun Ra: “Reflections In Blue” from Visits Planet Earth/Interstellar Low Ways (Evidence Records 1992) Happy 100th Anniversary of the Arrival Day]

Unprepared for Arctic Oil

Research Icebreaker

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. As the Arctic regions warm with the changing climate, the oil industry has sought to drill offshore in the northernmost seas. But even though the Arctic Ocean has less summer ice these days, the National Research Council recently warned that the region is still so dangerous and isolated that we don’t have the proper gear or personnel to clean up a potential oil spill. Shell's plans to drill in the Chukchi Sea last year were delayed by equipment and weather problems, and the company has put off drilling this year too.

Joining us to discuss the state of engineering readiness to handle an offshore spill is Mark Reed, he's a Senior Scientist at the Norwegian research foundation SINTEF, and a member of the NRC committee that authored the report. Welcome to Living on Earth.

REED: Thank you.

.jpg)

Arctic sea ice (photo: NASA Ice, creative commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what is about the Arctic that makes coping with an oil spill more difficult than - say - cleaning up oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico or other temperate waters?

REED: Well, the first thing to note is that we’re not very good at cleaning up oil anywhere, but yes, in general, there are a lot of negative aspects to a spill in the Arctic versus in temperate regions. If it’s in the winter, of course, you have to deal with both darkness and cold temperatures. This makes the work a lot more challenging, and of course, the equipment that you’re using has to be made to function in freezing weather. The ice makes access to oil more difficult, on the other hand, the presence of sea ice can serve to contain a spill such that it doesn’t spread over large areas, so there are some pluses and minuses to a response action in the Arctic.

Indigo Bunting Passerina

CURWOOD: Some of the concerns that have been raised over proposed drilling in the Bering Sea involve long distances for any kind of rescue or recovery machinery to get to a potential spill. In the areas of the United States that are looking at drilling in the Arctic, what kind of infrastructure is there to respond to a spill?

REED: Well, one of the major problems is that the infrastructure is very limited. In our report, we point out this is probably one of the major issues that needs to be addressed.

CURWOOD: What needs to be done?

Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

REED: Well, one thing is communication. You need to be able to get information to the spill responders and from the spill responders in essentially real time, and things like cell phones are not useful up there at this point. There’s also a problem with airplane overflights that give you information on where the oil is and where should you send your equipment now or tomorrow. Flying airplanes in the Arctic is more challenging than in more temperate less turbulent areas. You also have to think about, to mount a large response action requires a lot of people and a lot of equipment. So you need housing for people and maintenance for equipment and these capabilities are just not in place.

CURWOOD: What organizations or nations should be responsible for setting up the information systems and getting a spill response infrastucture in place?

REED: Well, this is a circumpolar problem, and all of the countries that border on Arctic waters need to be involved here. This is a situation where it would really be useful to have some international cooperation if we can ignore the problems among what I can call the “Arctic bordering countries”.

CURWOOD: I’m wondering if you’re referring to the tensions between the US and Russia?

REED: Right now, that’s of course the major one I think, but China also has its hand in here. Those are maybe the...

CURWOOD: Wait. The last time I looked, China doesn’t border the Arctic.

PAGE: No, they don’t. [LAUGHS] But that doesn’t stop them from being interested and putting their hand in the pot. But if we could eliminate some of those problems and deal with this in a cooperative fashion, I think that we could share the costs and the benefits of oil exploration in the Arctic, and reduce the risks significantly.

CURWOOD: What do you make of Shell Oil company putting off its plans to drill in the Chukchi Sea given the challenges of the Arctic?

REED: Well, I think it’s probably a wise and conservative move for them to make to give them a little bit of time to reconsider how we’re going to do this. Regardless of how well we plan, things won’t work out exactly the way we want them to so we have to have some redundancy. Most of us on the committee agree that we need to be more prepared than we are today before we venture too far north. It’s probably too much to ask for one company to put all this together, and the rest of us sit around and watch. I think it has to be a, not just multi-industry but multi-national effort, to do this well.

CURWOOD: So given all the challenges in the Arctic and given the issues around climate change and the burning of fossil fuels, how much sense does it make to be trying to extract hydrocarbons in an environment like the Arctic?

REED: Well, again, that’s a question that has a lot of different angles. I will say that in my personal opinion that the problem with oil spills is relatively minor compared to the effect that global warming is having on the Arctic. If you’re worried about polar bears or other marine mammals, climate change is a much, much bigger issue.

CURWOOD: Mark Reed is a Senior Scientist for SINTEF in Norway, and a member of the National Research Council’s committee on responding to oil spills in the Arctic. Thanks so much, Mark, for taking the time.

REED: Yes, thank you for having me, and good to talk to you, Steve.

Related links:

- Read the report here

- SINTEF website

Arctic Explorers

Arctic Sea Ice. (Courtesy of Fiamma Straneo)

CURWOOD: The Arctic Ocean may be opening up now as its ice retreats, but for centuries it has kept even the most daring explorers at bay. And among the most daring and determined was Henry Hudson, who set sail some four hundred years ago from England in search of an Arctic route to the riches of Asia. It was an ill fated journey that ended in disaster for Captain Hudson and his son, and they never did discover the fabled Northwest Passage. Even today, despite satellite maps and GPS, much of that same region in Northern Canada remains an unexplored mystery. But there are still those who dare to venture, and challenge the unforgiving place just as Henry Hudson did four centuries ago. Emily Corwin of Mind Open Media has their story.

MILLMAN: My name is Lawrence Millman, and I'm an Arctic explorer, and I have an abiding interest in other Arctic explorers who disappeared off the face of the earth.

[MUSIC: EXILIO]

CORWIN: On a modern-day expedition to the Hudson Bay, Larry Millman overheard an unusual story about the first white man to live among that region’s native Cree. The story had been passed down among the Cree for generations, and the white man was known as Firebeard.

MILLMAN: With very little research I determined that in all probability Firebeard was Henry Hudson, who was perhaps the best recognized navigator of his day.

CORWIN: There are only a few things we know about Henry Hudson’s personal life.

MILLMAN: Here’s one of the things we know about Henry Hudson, that he had a great affection for bangles. Like jewelry, and males in those days wore lots of jewelry and he liked golden wristbands, and rings. We know that and there's one source that mentions that he really enjoyed big meals.

CORWIN: Back in the early 1600s, navigators were tired of sailing down around South America, all the way across the pacific to Asia. So a British trading company hired Henry Hudson to find a shorter route.

MILLMAN: He sets out from England in 1610…

[MUSIC: MEKUBOLIM]

…touches Iceland, gets some supplies and heads into the “Furious Overfall” otherwise known as Hudson Strait -- they thought, because of all these heavy currents, that it was close to the Pacific, it had to be a great ocean because of the currents. No, it wasn't a great ocean, it was a long narrow strait.

CORWIN: This so-called Furious Overfall with its counter-clockwise swirling chunks of ice was much, much colder than the guys on Hudson’s crew ever expected. Pretty soon their ship got stuck – it was mired in the ice.

MILLMAN: There's a feeling of complete and utter paralysis. You might like to go somewhere but you can’t go anywhere, you can't get your boat to move a bloody inch.

CORWIN: Hudson’s crew wanted to turn around. They said...

MILLMAN: ‘As soon as we get out of this ice, Captain Hudson, we're heading home’. There was an interesting democracy among crews of that day. If the crew wanted to head home and the captain didn't, the crew got their way. He said ‘Well look’, he brought out a map, he showed his crew the map, ‘we're a hundred miles farther west than any other known expedition. And you want to turn around.’

[MUSIC: MEKUBOLIM]

Well they couldn't turn around and he was using that possibly as part of his ammunition.

[MALE VOICE: We stand now on the edge of discovery. This great bay must open somewhere and yield a passage. Let’s thrust westward in the common triumph of raising the Indies!]

CORWIN: That’s from the 1964 film “The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson.” Come November, it was too cold and icy to go on. Hudson and his crew would spend the winter camped on the shore of the frigid James Bay.

MILLMAN: It was just an absolute miracle that they survived the winter.

CORWIN: The crew was starving and it was freezing cold. Scurvy made their gums bleed and their teeth loose. When the ship could finally sail again, Hudson told his crew they would return to England. But there was a problem.

MILLMAN: Hudson wasn't going in the right direction for England. He was heading West, but he should have been heading North, the same way they came in. And when one of the members of the crew noticed that certain individuals had cheese, and had more food than they themselves had, that was the spark that inspired the mutiny.

[MALE VOICE: ‘Arrh now that you’re free of us Master Hudson, you may sail westward for all you are worth!’ HUDSON: ‘Mr. Green – it is not too late. Reconsider!’]

CORWIN: The crew threw Hudson and his son on a sailboat, and headed right back to England. Did Hudson go by “Firebeard” and live among the Cree, or did he freeze to death alone in the bay? We don’t know. 400 years later, another adventurous Arctic Explorer wanted her turn. The legend of Henry Hudson loomed.

STRANEO: Every time I brought up Hudson Strait everybody shook their head, it had a reputation for being a really tough place where to work.

CORWIN: That’s Fiamma Straneo. She’s an Ocean Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Three years in a row Straneo has returned to the same place where Henry Hudson disappeared. She’s not looking for riches or spices or any of that. And none of her crews have ever threatened mutiny. See, Straneo is on a new kind of mission. She wants to understand climate change in the Arctic.

[MUSIC: EXILIO]

STRANEO: And so if we think of Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait as a small microcosm in the climate system, then if I can understand how they work, if I know what goes in and I know what comes out, then I can put this in a bigger model that has the entire planet, the entire atmosphere, and it’s going to help predict future change.

CORWIN: As the planet heats up, moisture evaporates from warm places like the tropics. And then wind pulls that moist air over the Arctic, where it rains and snows into the ocean. That fresh rainwater is lighter than the saltwater, so it sits like a blanket on top of the entire ocean, getting in the way of the ocean’s usual temperature regulation and circulation patterns. Straneo is monitoring the water in the Hudson Strait, a bottleneck that connects the Hudson Bay to the Atlantic Ocean. This is the straight that Henry Hudson may have called the Furious Overfall - with its massive 30-foot tides and swirling currents.

STRANEO: When you’re close to land you just see the entire landscape change. Your entire ship just goes up and down. You look and you thought ‘oh there was an island there’ and well it’s gone. Because there are these super strong tides, the other thing that you see are these really fast currents, which switch every six hours or so; there’s so much mixing and turbulence the water literally boils.

CORWIN: Here is Straneo, in the same treacherous strait that brought about Henry Hudson’s demise 400 years ago.

FIAMMA: And so if you read the old books and the old maps, Hudson Strait is actually indicated with a waterfall -- like the currents were so strong the ships had a really hard time navigating it.

MILLMAN: There are a couple maps that actually show Hudson Bay long before Europeans ever went there. ‘Here Be Dragons’, ‘Here Be Monsters’, or you fall off the edge at this point.

CORWIN: The legends of monsters that tormented Henry Hudson’s crew boded ill for Straneo’s expedition. Yet Straneo forged ahead. For her research, she put three chains of instruments down into the water. These chains – called moorings - are so big they have to be lowered in with a crane. What looks like a massive red fishing bobber sits at the top, while the instruments sink down, measuring water salinity, velocity, and temperature.

STRANEO: I think the most exciting moment was putting everything in the water the first time. Just seeing everything disappear, it feels silly because that's it! You've just chucked thousands - 100s of thousands of dollars in the water, don't know what they're doing, but just putting everything in and know that if everything goes as planned you can come back and there will be data, and there's something magical about letting go of all the instruments and just sort of walking away and trusting.

CORWIN: Straneo’s reward for taking on this challenge is getting to be the first.

STRANEO: One of the reasons to work in the Arctic is that it's an incredibly important place in the circulation of the ocean and the climate system and yet we know so little about it, so you can go to so many places in the Arctic and be the first person ever making measurements there, and so when you pull up this instrument that's been in the water for an hour, or a year, and you look at these data, you think WOW, nobody's ever seen what goes on under the surface of the ocean here, you're sort of, hearing a story for the first time.

CORWIN: Kind of like when Larry Millman heard the story of Firebeard for the first time. For Millman, being in a place like Hudson Bay gave him something else, too – a new kind of sensory experience.

MILLMAN: When you're in a place that you know, each wrong step will land you, umm, in if not trouble, then deep doodoo, bear, caribou, or otherwise then you're very cautious and careful, then you're aware of the world around you. So I enjoy that all my senses are on the alert when I’m in the Arctic.

[MUSIC: SEAFARING SONG]

CORWIN: Larry Millman left the Arctic with a new kind of awareness and a story about Henry Hudson. Henry Hudson’s mutinous crew left Henry in the middle of the Hudson strait. And Straneo left the Hudson Strait with the data she needed to build a predictive model of climate change in the Arctic. All of them did something that had never been done before, in a place no one, except for, perhaps, the native Cree – was meant to survive.

For Living on Earth, I'm Emily Corwin.

CURWOOD: Our archive story about Arctic explorers comes to us from Mind Open Media, where researchers tell stories about their science and their lives. To learn more, head to our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Mind Open Media

- Watch “The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson” (28 min.)

- Lawrence Millman’s website

- Fiamma Straneo’s Research Group

CURWOOD: Coming up...the magic of spring in the great meadows revealed to our ears. That's right ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Fats Waller: I Ain’t Got Nobody” from Breakin The Ice: The Early Years 1934 – 1935 (RCA Bluebird Records 1995) Happy Birthday Fats Waller. ]

Beyond the Headlines

Pat Sajak’s been the host of Wheel of Fortune since 1983 (photo: Thomas Hawk, creative commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamed of in your philosophy, and there are more stories lurking beyond the headlines than most of us ever encounter. And that's why we turn to Peter Dykstra, publisher of Environmental Health News, EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He joins us on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Hi Steve, you know, the boundaries of climate science are also expanding every day, and as we know more, it’s certainly not getting any prettier. But we’re learning more and more about how climate impacts touch every realm of scholarly pursuit, and this week, we saw a breakthough.

CURWOOD: Ah, academics. Tell us about it, Professor.

DYKSTRA: Climate science and policy have finally reached the lofty realms of game-show hosting. Pat Sajak, who’s hosted “Wheel of Fortune” since 1981, sent out a bomb of a tweet in which he said that people who are concerned about climate change are “unpatriotic racists.”

CURWOOD: Whoa. Unpatriotic racists? How did he explain that one?

DYKSTRA: Well, one of the beauties of having 140 character limits on tweets is that you never have to explain yourself, but it went viral, and within 48 hours, Pat Sajak tweeted that this was all intended as parody and a joke, because as we know, calling people unpatriotic racists for taking climate science seriously is as totally hilarious as climate change itself. Pat tweets a lot of politically provocative stuff, but he’s not the only game show legend who does: Chuck Woollery, who hosted “The Love Connection” and preceded Pat Sajak on Wheel of Fortune, is also a vocal climate denier in social media.

CURWOOD: Peter, I have to ask you if Vanna White has weighed in on this topic. I mean, are the vowels turning any earlier due to climate change?

DYKSTRA: No, Vanna doesn’t have much to say, just like on the show, but here’s one more game-show-hosting icon: Bob Barker, now 90 years old. A few years ago he gave a boatload of money to the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, they named one of their boats after him. But this year, Bob went to bat and did a TV ad endorsing David Jolly, who won a Florida Congressional seat in a special election in March. David Jolly has a mostly Tea Party platform that’s anti-regulatory. He's also spoken out in favor of oil drilling in the Gulf of Mexico, in spite the 2010 oil spill.

CURWOOD: OK, Peter, what’s behind door number two this week?

DYKSTRA: Well, remember a few years ago when the North Carolina legislature outlawed the use of sea level rise data in coastal protection?

CURWOOD: Sure, I think it's called the King Canute law...command the seas to recede?

DYKSTRA: Whatever. Well, there’s a new law in the works, It passed through North Carolina’s Senate Commerce Committee. It would make it a class one felony to disclose the toxic chemicals used in fracking operations, and violators would potentially face fines and a couple of months in prison. That bill would also prevent local bans on fracking, and it would limit water testing in potential fracking zones.

CURWOOD: All told, it sounds like it could become a lot harder to oppose fracking in North Carolina.

DYKSTRA: Yes, and here’s what the new potential law is called: it’s the Energy Modernization Act. The state actually does have a moratorium in place on all fracking until it can sort out its regulatory process, but some people are worried that this is one more sign that regulation won’t be much of a factor when it comes to fracking in North Carolina.

CURWOOD: Now, what do you have on the calendar for us this week?

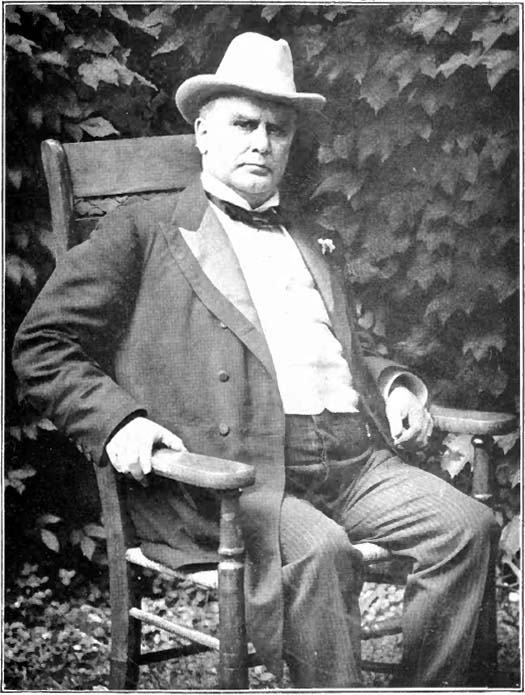

DYKSTRA: Well, we have one of those things that probably many folks haven’t heard of before, but it impacts your lives every day. This week it's the 114th birthday of the Lacey Act, signed into law in the year 1900 by President McKinley, and this spry old law is the granddaddy of the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

The Lacey Act was passed in 1900 and signed by President William McKinley (photo: Pach Bros, public domain)

CURWOOD: And before that there was pretty much a free-for-all on commercially valuable wildlife, huh.

DYKSTRA: Well, yes, but truth be told, it was still pretty much a free-for-all after the Lacey Act came into effect, but it helped a lot, and it was a building block - still is - for preventing widespread hunting and trafficking of fish and wildlife, trafficking of rare wild plants, everything from birds whose feathers were desperately needed for those ginormous ladies’ hats in the year 1900 to timber that’s taken from protected forests.

CURWOOD: And the Lacey Act is still around today, right?

DYKSTRA: It’s around and still used but it’s under criticism and it’s under attack. You may remember a few years ago when Gibson Guitars paid a $300,000 fine for using illegal wood, - they had imported rosewood and ebony from India and Madagascar. When they paid that fine there was a backlash from opponents of environmental laws, but whole case was based on the Lacey Act.

CURWOOD:Ah, which increases the value of antique guitars.

DYKSTRA: There you go.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is Publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and Daily Climate.org. Thanks so much, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thank you, Steve. We’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

[MUSIC: Dykstra: Sun Ra “lights On A Satellite” from Out There A Minute (Restless Records 1989)]

[SFX BIRD CALLS]

Springtime Birding With David Sibley

David Sibley’s hand painted portrait of a Mute Swan and cygnets. (© David Sibley)

CURWOOD: It's five o'clock on a clear May morning at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, Massachusetts.

[BIRD CALLS]

CURWOOD: At this time of year, in spring, these marshes, lakes and woodlands are pit stops for migrating birds heading north and a home for local birds looking to find a mate. It's the perfect place to meet up with David Sibley. He's the author of the landmark Sibley Guide to Birds and he recently released a second edition of his wildly popular and widely used bird guide. And as sunlight starts to flood the sky, the birds open their throats in a chorus that brings a gentle smile to David Sibley’s face.

[BIRD CALLS]

CURWOOD: So, who are we listening to here?

SIBLEY: Ahhh, we're hearing Northern Cardinal, Blue-grey Gnatcatcher, Warbling Vireo, Red-winged Blackbird, Swamp Sparrow, Yellow Warbler, Common Grackle, Catbird, Common Yellowthroat, Canada Goose.

CURWOOD: Gee, I think that you probably just doubled my life list for around here. [LAUGHS]

SIBLEY: I’m hearing a Northern Waterthrush singing in the bushes right there. That chirping sound descending in pitch.

[CALLS OF NORTHERN WATERTHRUSH]

CURWOOD: A Northern Waterthrush. Let’s look in your book. Where are we to find a Northern Waterthrush?

SIBLEY: It’s one of the warblers. So it’ll be...

CURWOOD:...in the warbler section back here.

[FLIPS THE PAGE]

SIBLEY: Right here.

CURWOOD: You’ve added something I didn’t see before in your other works which is a description of what the bird sounds like. Can you read that?

SIBLEY: A song of loud of emphatic clear chirping notes generally falling in pitch and accelerating loosely paired or tripled with little variation; called a loud hard sprik rising with strong K sound; flight call a buzzy high slightly rising zip.

CURWOOD: Your descriptions are almost the way people describe wine, with a little bit of this flavor and a hint of that and all that.

SIBLEY: Yes, we do. It’s so difficult to describe in words what a bird sounds like. You end up using words like mellow and rich and liquid and sharp and it does just sound like the descriptions of taste. [LAUGHS] If the words are used consistently and used repeatedly you kind of get a sense of what each one means and you’ll learn that yes, that thrushes tend to have a liquid sound, and orioles and robins, their voices have a rich sound. It’s fun to try to come up with words to describe all these sounds.

CURWOOD: So your first book, really, so many folks see that as a gold standard for a birding guide. So why do another?

SIBLEY: As soon as the first book went to the printer back in 2000, I started taking notes and gathering information about things I wanted to change, or new things I had learned. I look at those paintings and think I could do this or that a little bit better, or add details, or add new illustrations to show different things.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s take a step out into the meadow.

SIBLEY: Alright. Let’s head down this path through the marsh here.

[FOOTSTEPS ON DIRT PATH, BIRD SONG]

SIBLEY: So I’m hearing a Common Yellowthroat, Yellow Warbler, Grey Catbird, Red-winged Blackbird singing.

[SONG OF INDIGO BUNTING]

Up above us there’s an Indigo Bunting singing up in the Maple right there, that high pitched sound, and every note is repeated, every phrase is repeated. The Indigo Bunting is a migrant. They don’t normally nest right here. So we can be confident that that bird probably just arrived last night. It probably flew up from the south last night, dropped in here sometime early this morning, and now it’s checking things out, gets up to the top of the tree and sings a little bit to see if anyone answers, and it’s kind of assessing the area to figure out if this is a good place to stay for the summer, and I think the answer’s going to be no. It’s too wet for Indigo Buntings. They don’t nest here, so it’ll move on. Maybe it’s already moved on. I don’t hear it anymore.

This time of year, all the birds are singing, and it’s so much easier to walk through an area listening and hear what’s around, and it’s possible to identify every species, essentially every sound can be identified.

[GEESE HONKING]

SIBLEY: One of the things about birdsongs is their ears work a lot faster than ours. Their ears and their brain processing of sounds works a lot faster than we do, so they’re hearing an incredible amount of information more than we do. If you take a bird sound and slow it down to about a quarter speed, then you start to hear the kind of detail they’re hearing.

CURWOOD: So why is it that birds are, well, singing the loudest in the morning?

SIBLEY: I think the song in the morning is mostly kind of a checking in with the neighbors. Male birds sing to kind of defend their territory, to mark the edges of their territory. So they’ll circle around to perches at the edge of their territory and sing from those spots and their neighbors, they’ll recognize the sounds of their neighbors. They recognize each other. So the morning song is kind of just an announcement that, “I’m still here. Are you still here? Yes. OK. Territorial boundaries still enforced? Yes. OK.”

CURWOOD: And what about the migrants?

SIBLEY: Migrants, they might be singing to sort of test the area, to see if they get a response, to see if there’s a female nearby that might respond to the song. But mostly, it’s probably just hormones. It kind of goes back to the old poetic thing about birdsong just being an outpouring of joy, the uncontrollable urge to sing with the dawn of the spring morn, and these migrants, they’re near their breeding grounds here, they’re heading north, they’re just about to enter this phase of life where they’ll find a mate, they’ll set up a territory, raise young, and they just can’t control themselves. They sing at dawn.

CURWOOD: One of the things that has certainly changed about birding is our awareness that the climate is shifting, and that means that birds are shifting. How do you account for that when you do a habitat range in your books?

SIBLEY: In the 40 plus years since I’ve been birding, starting in Connecticut in the 1970s and now in Massachusetts, I see really big changes in birds. Some species have increased tremendously like Canada goose, Wild turkey, Red-bellied Woodpecker. Some of those species are southern birds that are moving north, and some of that’s probably due to climate change, but there are all kinds of other things going on in bird populations, and a lot of species have declined. But it’s about equal numbers of sort of winners and losers in the last 40 years, so over that span of time, 40 years, the maps and the bird guide would have changed a lot for probably 10 percent of the species.

CURWOOD: 10 percent of the species in different places 40 years ago. What accounts for that, do you think?

SIBLEY: Mostly it’s changes in habitat. The big change here in the northeast is that, well, 100 years ago it was almost all farmland, there was very little forest. And 40 years ago, we were just coming out of that, and now, a lot of farms have been left to grow up to forest and all the suburbs that were built in the ‘50s and ‘60s with trees planted then, the trees are now 60 years old and big enough to support a lot of forest birds, the ones that can coexist with people like robins and bluejays and grackles and Wild turkey and even birds like Pileated woodpecker. It was incredibly rare in Connecticut when I was a kid in the ’70s, and now they’re pretty widespread and found in the suburbs.

CURWOOD: Indeed, and hungry in the suburbs too.

SIBLEY: Yes, sometimes unpopular when they look for food in the siding your house, but they can do a lot of damage. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: So you’re an ornithologist, you’re a writer and an artist. And you hand-paint every one of these bird pictures in your guide yourself. Tell me about the process and why you do it.

SIBLEY: When I’m in the field, I’m watching birds, I’m studying shape and posture and doing pencil sketches and then, so I have years and years, thousands and thousands of pencil sketches from the field. When I’m back in the studio I get all of my pencil sketches and I use photographs as reference to get all the details right, and I work on paintings in the studio. For me, and we’re really lucky in this time now, and it’s really in the last 15 years that photographs have become so numerous, to have so many photographers doing such good work and everything’s available on the internet that for the work that I do, I can find hundreds of photographs of every species. Illustrators like Peterson had to use specimens for their reference material.

CURWOOD: Yes, I guess Audubon famously shot everything he drew.

SIBLEY: Yes, he did, and he was traveling through the woods with nothing but a shotgun and his painting supplies. He didn’t have binoculars, he didn’t have cameras, nobody had a camera. There weren’t even books he could carry with him to help identify the birds. It was just him and his paintings.

[SOUNDS OF SWANS FLYING]

SIBLEY: A pair of mute swans flying by.

CURWOOD: Not so mute.

SIBLEY:[LAUGHS] Yeah, that sound is their wings. They do make vocal sounds also. They’re not entirely mute, but that sound is produced by their wing feathers. Just sort of humming through the air with each wing stroke.

CURWOOD: So, I have to ask you, what got you hooked on birding?

SIBLEY: I have always been interested in birding. My father’s an ornithologist so I’m sure that had something to do with it.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I guess so.

SIBLEY: But, yeah, birding was a part of what our family did, I just really enjoyed it, the birding and I was always drawing birds also.

CURWOOD: So when did you realize that, well, this would be the work part of your life?

SIBLEY: As a young teenager in Connecticut, I was going out on the weekends with people from the New Haven bird club and watching birds, identifying birds, learning about them. People were supportive of my interest in birds and my drawing, very encouraging. And Roger Tory Peterson who had illustrated the most popular field guide at the time lived about 20 miles away. I met him a few times when I was a kid, and to have him flip through a few pages of my sketchbook and look at it and say, “Oh, these are very nice. Keep it up.” And I think I grew up with the idea that writing a field guide was a perfectly viable career choice. I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in birds.

CURWOOD: Well, that’s a better way to grow up birding than being dragged out at five in the morning to stand in the cold.

SIBLEY: [LAUGHS] We did plenty of that too.

CURWOOD: There’s something about birding, which even if you don’t want to, it kind of grabs you.

SIBLEY: Yes, and the popularity of birding has increased so much in the last 40 years. When I started out in the ’70s, it was rare to see another birdwatcher, and now, you go to a place like Great Meadows here, the parking lot at times will be filled with cars of birdwatchers. I think it’s just a desire to connect with nature, and birdwatching is just a way, it’s an excuse to set the alarm for 4:30 in the morning and go out even if it’s raining or windy, and get outdoors and just experience that. And it’s not so much about the birds, the birds are kind of the hook, the pull that gets us out there, but to a birdwatcher, it’s as much just the experience of being outdoors and feeling the change in weather and seeing the seasons change and being aware of those patterns. I think that's the real draw.

CURWOOD: David Sibley, thank you so much.

SIBLEY: Thanks, it's been a pleasure. What a great morning.

CURWOOD: David Sibley’s new book is called The Sibley Guide to Birds, Second Edition.

Related links:

- Sibley Guide Books

- Info about the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

[MUSIC: Gary Burton/Chick Corea “What Game Shall We Play Today” from Crystal Silence (ECM Records 1973)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. We had help this week from Qainat Khan.

Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of Red Tomato, supplier of righteous fruits and vegetables from northeast family farms. www.redtomato.org. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth