May 30, 2014

Air Date: May 30, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Taking The Lead On Climate Change

View the page for this story

President Obama believes global warming threatens national security and the US must lead to control emissions. Proposed new rules to curb coal-fired power plant pollution are among the most far-reaching executive actions to combat carbon. Europe has strong climate controls, but many newly elected EU lawmakers are wary of regulation. Wendel Trio, director of Climate Action Network, tells host Steve Curwood that as Europe looks to the next UN summit, it hopes the US will be a climate change leader. (05:10)

Protecting Homeowners From Landslide Risk

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

With global warming come more intense rains, floods and landslides. In Washington State, as Ashley Ahearn reports, local government is stepping in to buy out homeowners in danger zones, ignited a debate over managing landslide risk and property owners' rights. (06:50)

Some Banks Stop Funding Mountain Top Removal

View the page for this story

Coal companies have stripped the tops of mountains in Appalachia in search of the fuel. But as Amanda Starbuck tells host Steve Curwood, the Rainforest Action Network has helped convince some of the world’s biggest banks to stop funding companies that practice destructive Mountain Top Removal. (07:00)

Saving Chestnut Trees to Reclaim Mined Mountains

/ Jonna McKoneView the page for this story

Soaring American Chestnut trees once covered the Eastern US but a blight nearly wiped them out. Now botanists are breeding a blight resistant chestnut to help restore American forests and reclaim degraded mountaintop removal coal mine sites in Appalachia. Jonna McKone reports. (12:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood dive into the world of eco-archaeology and remember a dam accident that killed 2200 people and woke America up to the importance of mending infrastructure. (04:30)

The Oldest Living Things in the World

View the page for this story

Brooklyn-based contemporary artist Rachel Sussman speaks with host Steve Curwood about her journey around the globe photographing ancient organisms for her book The Oldest Living Things in the World (11:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Wendel Trio, Amanda Starbuck,

REPORTERS: Jonna McKone, Ashley Ahearn, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Activists pressure banks to stop funding a destructive form of coal mining.

STARBUCK: All of the major US banks and most of the European banks too were lending these mining companies the money they needed to expand mines, so it became clear to us that if we could ask banks not to lend that money we could cut off a really important component that was going into growing mountaintop removal mining.

CURWOOD: Some banks, but not all agree. Also, vast American chestnut forests once provided employment and timber.

HEBARD: The logs provided fencing to keep the cattle out of their gardens and then lumber from cradle to grave. People would be rocked awake in a chestnut cradle, buried in a chestnut coffin.

CURWOOD: A blight wiped out the chestnuts, but they may be coming back. We'll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from Stonyfield Farm. Makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more.

Taking The Lead On Climate Change

President Obama Speaking at West Point May 28, 2014 (Photo: White House)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. New federal rules on global warming emissions from existing coal-fired power-plants could prove one of the most lasting legacies of President Obama. Congressional reluctance to enact carbon-control legislation has caused the president to act through regulation - such as tightened fuel-efficiency standards for vehicles. The Administration's latest National Climate assessment, released on May 6, stresses the urgency of action. Climate change is here, now, and threatens our food, water and National Security. And the President made a point of underlining that security issue to America's elite army graduates at West Point on May 28. He says the nation needs to work through international law, cooperating with allies, to face all threats.

OBAMA: That spirit of cooperation needs to energize the global effort to combat climate change -- a creeping national security crisis that will help shape your time in uniform, as we are called on to respond to refugee flows and natural disasters and conflicts over water and food, which is why next year I intend to make sure America is out front in putting together a global framework to preserve our planet.

CURWOOD: Next year, delegates will meet in Paris for crucial negotiations aimed at strengthening the UN treaty to control carbon emissions. To date, Europe has led the way towards a worldwide agreement, and adopted mandatory limits on global warming gases within its own borders, while the US has dragged its feet and opted out of the Kyoto protocol. But in the recent European Parliament elections, citizens expressed deep frustration with the EU and its institutions, voting in vastly increased numbers for fringe parties often hostile to central control and regulation. This could affect the European approach in the upcoming climate talks, so we called Wendel Trio - he's Director of Climate Action Network in Europe - to see what he thinks.

TRIO: Europe has engaged itself on a process to develop new climate and energy legislation for the period after 2020. That process will continue irrespective of having more Euro skeptics in the European Parliament because the process has been developed...it can't be stopped anymore.

CURWOOD: Now the world will be meeting next year in Paris for the international climate negotiations. What do you expect from the EU at those talks, given the mood that’s been set by this election?

TRIO: In general, the mood in Europe at the moment is not extremely positive. Europe feels in many ways that they are a bit isolated in terms of climate action and that other countries are doing far less than what they are doing. So I think what we actually would need in Europe is kind of a new revival of real ambition because without the European leadership role, it would be very hard to come to a real deal in Paris.

(bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: There are a number of regulations that the Obama administration is working on regarding climate. How important is success in getting those regulations forwarded in the United States to the negotiations in Paris?

TRIO: I think if we can see these new regulations being supported, I think it will show to the rest of the world that President Obama is really serious. I mean, one of those regulations is about setting emission performance standards for power plants - that is something Europe doesn't have, so it would also be setting some kind of an example for Europe. And it might be really a tool that we could use again as European civil society to point to our leaders, “Look, the President of the United States is ready to move forward in the United States and we need to be able to do the same in Europe.”

CURWOOD: What are your feelings now about the prospect for next year in Paris, given the recent elections in Europe, and the other things that we’ve talked about.

TRIO: Well, it’s really a crucial opportunity for the world to do something, but at the moment, the pace of the negotiations and the pace of the preparations of countries to really come with proposals are way too slow. We really need to see more than what is happening now. Unless countries are accelerating their preparations, it might be difficult to get to the right kind of agreement in Paris.

EU member flags outside the European Parliament building in Brussles. (Bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: Wendel Trio is Director of Climate Action Network in Europe. Thanks so much, Wendel.

TRIO: OK, thank you.

CURWOOD: For his part, President Obama seems to be doing his best to galvanize climate action from the United States, and he argues that America must be a true leader.

OBAMA: You see, American influence is always stronger when we lead by example. We can’t exempt ourselves from the rules that apply to everybody else. We can’t call on others to make commitments to combat climate change if a whole lot of our political leaders deny that it’s taking place.

CURWOOD: The June 2 release of proposed EPA rules for existing power plants may convince the Europeans and other major carbon emitters that the US is finally serious about imposing politically unpopular limits on global warming gases.

Related links:

- President Obama’s speech at West Point

- President Obama’s Climate Plan

- Climate Action Network

[MUSIC: Slim Harpo “Buzzin” from The Excello Singles Anthology (UMG Records 2003)]

Protecting Homeowners From Landslide Risk

John Thompson, a geologist and senior planner with Whatcom County, surveys the Jim Creek and Bald Mountain landslides along Canyon Creek. The slides have blocked the creek repeatedly, causing flooding that has destroyed homes downstream. (photo: Ashley Ahearn)

CURWOOD: As global warming advances, basic physics tells us that increasingly torrential rains increase the likelihood of devastating landslides, such as those that recently struck the Balkans and earlier this year wiped out a community in Oso in Washington State. And in mountainous areas prone to landslides it can be tough to strike a balance between the rights of people to live in these beautiful but risky places and their safety. Reporter Ashley Ahearn of the public media collaborative EarthFix visited a wild area in Washington where officials made a controversial move to keep citizens out of harm's way.

AHEARN: In their spare time, Dan McShane and John Thompson like to bushwack through thick forests.

[SOUNDS OF WALKING THROUGH WOODS]

AHEARN: Until they arrive, suddenly, at cliffs...cliffs that are formed when massive amounts of earth slide off mountainsides.

AHEARN (on tape): WHOA!

AHEARN: We step out of the woods and look down the bare face of a landslide. 500 feet or so below us Canyon Creek rushes along on its way to meet the Nooksack River.

These geologists have let me tag along with them, high into the mountains near Mt. Baker, to check out two landslides that have cost Whatcom County millions of dollars, and a lot of headaches.

McShane shimmies out along a log, wedged between two sides of the ravine, to get a better view. My stomach lurches a little bit when he tells me to follow him.

MCSHANE: I have a comfort level though that might be a little warped.

Ashley Ahearn (on tape): I think you're part billy goat.

Dan McShane and John Thompson hike through thick forests above the Jim Creek landslide, which has blocked Canyon Creek in the past, causing flooding downstream. (photo: EarthFix)

MCSHANE: I'm afraid of heights actually.

AHEARN; I clutch my microphone and clamber across after the crazy geologist, rocks skittering away down the cliff below me.

[SLIDING GRAVEL, TALKING]

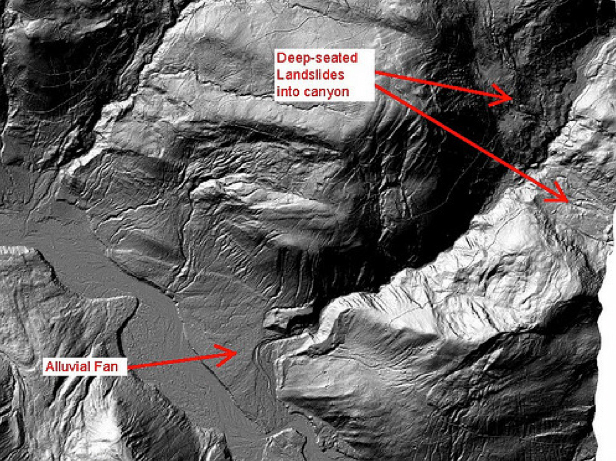

AHEARN: Canyon Creek is a steep, fast-flowing tributary of the Nooksack River; we’re about 30 miles east of Bellingham in the North Cascades. There are actually two active landslides here, one on either side of the creek. McShane and Thompson explain.

MCSHANE: We're on the side of canyon creek on the lower part of the Jim Creek landslide and we're looking across at the Bald Mountain slide. The Bald Mountain slide goes way up.

Dan McShane stands at the top of the Jim Creek

landslide. (photo: Ashley Ahearn)

THOMPSON: That's Bald Mountain in the far distance. This cupped face that we're looking at is where the slide originates, where the head of it is and then the toe reaches all the way down to the stream.

AHEARN (on tape): So we're standing basically on, if you think of the landslides as the gates that close and block the river, we're standing on one gate of this river, right?

MCSHANE: Yeah, that's a good descriptor, pinch points, because they are both coming at each other, towards the river. In a way the worst scenario would be that you have a pretty big movement on one or the other that would cause the river to be dammed.

AHEARN: And that's exactly what happened here in 1989. These landslides blocked Canyon Creek. The water built up behind the debris and then it burst through. It swept away four homes downstream. No one was hurt.

BENSON: Some of the reports that the locals gave was that it got very quiet for hours before. All of a sudden the stream dropped.

AHEARN: Rick Benson's house wasn't harmed by the flooding, but he's lived in the community for more than 15 years and knows people who lost homes. He says they were lucky to realize that the river had almost stopped flowing, a key sign that things were backed up upstream, and that a big flood was coming.

BENSON: And sure enough, 3 or 4 hours later was when the deluge came through and washed everything out.

AHEARN: That landslide - and several others that followed it - got Whatcom county's attention.

First, the county built a levy in 1994 to deal with the flood risk. But it developed structural problems that were going to cost the county more than a million dollars to fix. It was also harmful to the salmon that use the creek.

Flooding, caused by landslides in Canyon Creek, swept away four homes in Glacier Springs in 1989-90. These steps are all that’s left of one of the properties. (photo: Ashley Ahearn)

Whatcom County started looking at other options. The Council concluded that people shouldn't be living in the flood zone below the landslides. So for the past decade or so, Whatcom County has bought out 31 properties along Canyon Creek. It paid for the buy out with some county money, some Federal money from FEMA and some from the Whatcom Land Trust. All told, the buyout cost more than 1.6 million dollars. Rick Benson thinks the county made a good call.

BENSON: I think moving the homes and protecting people and property where they could, I thought it was the right idea. But it all depended on who you talked to. In general I think it was well accepted and the vast majority of owners sold their lots.

AHEARN: One property owner who opposed the buyout, but still took the money, declined to be interviewed for this story. Dan McShane, the geologist you heard from earlier - was actually serving on the county council at the time of the buyout decision. He played a key role in convincing the county council that letting people continue living there was not an option.

MCSHANE: I used terms like 'it would be immoral' because in my mind it was. This isn't property rights any more, this is about life and death. When you get to that level I think people react much differently.

AHEARN: Since the devastating Oso Landslide killed more than 40 people in Snohomish County earlier this spring, conversations about property rights versus government authority have taken on new weight.

For some people, owning land is a symbol of freedom, people should be able to do whatever they want on their property, even if it's in a dangerous area. The question is who is responsible when disaster strikes?

The Bald Mountain and Jim Creek landslides converge on Canyon Creek, blocking the stream. (photo: EarthFix)

Ken Mann serves on the Whatcom County Council now. He says if he'd been in office at the time of the buyout decision, he would have voted against it.

MANN: It's not for me to give out charity on behalf of the people of Whatcom County. We should not be in the business of foolproofing and disaster proofing the world. Let people have their freedom, do what they want on their property and give them the responsibility to deal with the consequences.

AHEARN: Mann believes people need to do their homework before they buy, but the county should help buyers get the best information about the potential risks associated with their property.

MANN: The government should be in the business of sharing information. I know in the world of GIS – Geographic Information Systems -- there is a ton we could be doing and we're limited by the number of staff and resources we have but I'd like to look at that.

AHEARN: The technology is there, but it's expensive, and most counties are just beginning to incorporate it. Right now only 22 percent of Washington State has been mapped using LIDAR technology. LIDAR imagery cuts through the tree layer to show where old landslides have occurred. The Washington congressional delegation is urging federal lawmakers to better fund landslide hazard mapping.

This LIDAR image shows the Jim Creek and Bald Mountain landslides. The community of Glacier Springs is located in the alluvial fan of the creek, roughly three miles downstream of the landslide “pinch point.” (photo: Dan McShane)

It's impossible to know how the residents of Steelhead Drive in Oso would have responded, had they had more information about their landslide risk or been given the option to take a buyout.

In Whatcom County, the buyout wasn't a quick or easy process, but now there are 31 fewer households in harm’s way.

I'm Ashley Ahearn in Glacier, Washington.

CURWOOD: Ashley Ahearn reports for the public media collaborative EarthFix.

Related link:

Listen to this and other stories from the Pacific Northwest on the EarthFix website

[MUSIC: Miles Davis “Yesternow” from Jack Johnson (Columbia Records 1970)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...new hope for the American chestnut and the Appalachian mountaintops devastated by mining. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis: “Ursula” from Man With The Horn (Columbia 1981)]

Some Banks Stop Funding Mountain Top Removal

Mountain Top Removal mining has devastated many of the forests of Appalachia (photo: Paul Corbit Brown, Rainforest Action Network)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. The coal industry is under fire in the US from several directions, ranging from calls to pull investments from fossil fuels to proposed federal regulations to limit global warming emissions from power plants. And now, in the face of pressure from activists, banks have stepped into the fray. Wells Fargo and JP Morgan Chase are among major banks that have pledged to stop lending to finance the ecologically destructive mining technique known as “mountaintop removal”. The activists include the Rainforest Action Network, and as their campaigner Amanda Starbuck explains, mountaintop removal has devastated Appalachia for years.

STARBUCK: Mountaintop removal coal mining is one of the most destructive forms of coal mining that is practiced in the United States, and it mostly takes place in Appalachia, the Southeast US. The general topography in that region is rolling peaks, high mountaintops, steep valleys...you can stand on top of a viewpoint and these go on as far as the eye can see. It’s really quite beautiful but when this type of coal mining takes place the coal company will first of all come along and clearcut all the forests off the top of the mountains. These are the most diverse forests in the United States, so right there there’s a huge ecosystem loss. Next, they will lay explosives and blast away the top of the mountains, and the reason that they do that is to expose these thin narrow seams of coal, and then the coal gets transported for use in coal fired power plants.

Amanda Starbuck (photo: Rainforest Action Network)

CURWOOD: Now what happens next in this process?

STARBUCK: Well, the next bit is in many ways as horrific as the removal of the peaks themselves. All the rubble that's left, so this is rocks that are not coal and that contains things like heavy metals, pretty toxic substances like mercury, this gets swept off the new top of the mountain which can be 200 or 500 feet lower than once was into the neighboring valley. So effectively where you once had high peaks and low valleys, you have a more leveled out surface; instead of beautiful forests and streams it's exposed rubble and waste.

Activists deliver coal waste to PNC bank. PNC is the largest US financier of Mountain Top Removal mining, according to Rainforest Action Network (photo: Rich Clement))

CURWOOD: So Rainforest Action decided to work on this a few years ago. Why did you decide to go after the banks that fund mountaintop removal rather that go after the companies themselves?

STARBUCK: We decided to focus on banks because banks have a lot of options where they invest the money. We’d been tracking where the mountaintop removal mining companies get their financing from and through some fairly straightforward research we discovered that all of the major US banks and most of the major European banks too were lending these mining companies the money they needed to expand mines, buy the machinery and continue to grow this practice. So it became clear to us that if we could ask banks not to lend that money we could cut off a really important component that was going into mountaintop removal mining.

CURWOOD: Now, a number of major banks have agreed to stop funding coal companies that engage in mountaintop removal. Which banks have signed on?

STARBUCK: Most recently, two of the largest US banks, Wells Fargo and J.P. Morgan Chase, have stopped doing business with the biggest mountaintop removal coal mining companies and they've been joined by a couple of the largest European banks, Royal Bank of Scotland and BNP Paribas, a French bank which is also in the states as Bank of the West.

CURWOOD: Who are the big players that are still supporting mountaintop removal?

STARBUCK: So we still have a ways to go. There still a number of US banks continuing to loan to this sectior, in particular, PNC Bank, also Citibank and Morgan Stanley, but Barclays Bank, which is a London-based bank, is the largest financer of mountaintop removal, so we’re calling on Barclays to follow their competitors and stop funding mountaintop removal.

CURWOOD: Now why would banks agree to stop funding mountaintop removal? Um, they see this as a moral issue or good business?

STARBUCK: Over the last 10 years we've noticed that banks are increasingly sensitive to environmental issues and there's a number of reasons. The people that work at banks, they’re just like us, they have families, they care about the impact of their work, what that means future generations. So there’s a part of it to do the right thing there, but at the same time, banks are fundamentally tasked with maximizing profits and making money, and anyone’s that’s taking a hard look at the coal industry right now would be really concerned about their ability to continue to turn profits. We’re burning less coal in the United States, so there’s less business for the industry, but also we’re starting to see that that government is really starting to tighten up on regulating this industry, so the liability risk for the mountaintop removal from coal mining companies - this is looking pretty bad right now.

Residents gather atop Kayford Mountain, West Virginia to show the impact of increased investment in mountaintop removal coal mining as part of a National Day of Action

(photo: Paul Corbit Brown, Rainforest Action Network )

I think one more critically important factor is that there's been a huge upswelling of grassroots power, people power, speaking out about mountaintop removal and saying, “This is immoral. It can't continue.” We’re seeing tens of thousands of people in Appalachia stand up and speak out, rally, draw attention to this issue, and we’ve seen a huge swell of public pressure on the banks to get away from this as well.

CURWOOD: By the way, Rainforest Action, well, from your name we would think you'd be involved in places like Central Africa and the Amazon. Why mountaintop removal?

STARBUCK: That's right...that's such a good question! Rainforest Action Network fundamentally exists to protect forests and forest inhabitants, and for 30 years we've done a lot of work focused on forest protection but about 15 years ago we had the realization that we could protect all the acres of rainforests that were possible to protect, but if we didn't solve climate change ultimately those forests were not going to survive.

So if your concern is rainforests, or really whatever your environmental issue is, addressing climate change is absolutely a core component of winning that fight. And we know that if we’re going to address climate change we need to do two things: one of them is to address the most polluting forms of energy and stop things like mountaintop removal - mining or the buildout of the fossil fuel export infrastructure. And at the same time we need a huge growth in our clean renewable energy sector. So moving forward we’re challenging everyone...that's banks and energy generators to shift to clean renewable energy and we’re very committed to that vision.

CURWOOD: Amanda Starbuck is the Energy and Finance Director for the Rainforest Action Network. Thanks again for taking the time today, Amanda.

STARBUCK: Thank you for inviting me onto the show.

CURWOOD: We called up the banks Miss Starbuck named as the holdouts. Barclays corporate Spokesman Mark Lane wrote, in part, that:

“…we have not provided finance to any entity for the specific purpose of mountaintop removal.”

We've posted Barclays full comments at our website LOE.org.

A spokeswoman for PNC bank said they don't discuss or comment on their actions with third parties, and by our air date, we had had no response from CitiBank, or Morgan Stanley.

Statement from Barclays Bank:

Barclays is aware of the sensitivities around the practice of mountain-top removal. This is specifically highlighted in our guidance to the business with reference to the mining sector and we have not provided finance to any entity for the specific purpose of mountain top removal.

We have environmental lending policies and practices that have been in place for many years in support of our commitment to understanding the environmental and social risks associated with our lending activities. We aim always to take a responsible approach and give careful consideration to such impacts before decisions are approved. When we are asked to finance a specific development project, we apply the Equator Principles – detailed environmental and social criteria applicable to project finance transactions covering issues including local community consultation, the impact on indigenous peoples and cultural heritage sites, relocation of communities and related compensation. This approach to responsible lending applies equally to clients in the coal mining sector as to other industrial sectors.

We have met recently with groups that are critical of mountaintop removal mining so that we can learn more about their concerns.

Related links:

- Rainforest Action Network

- Check out a video RAN produced about MTR

Saving Chestnut Trees to Reclaim Mined Mountains

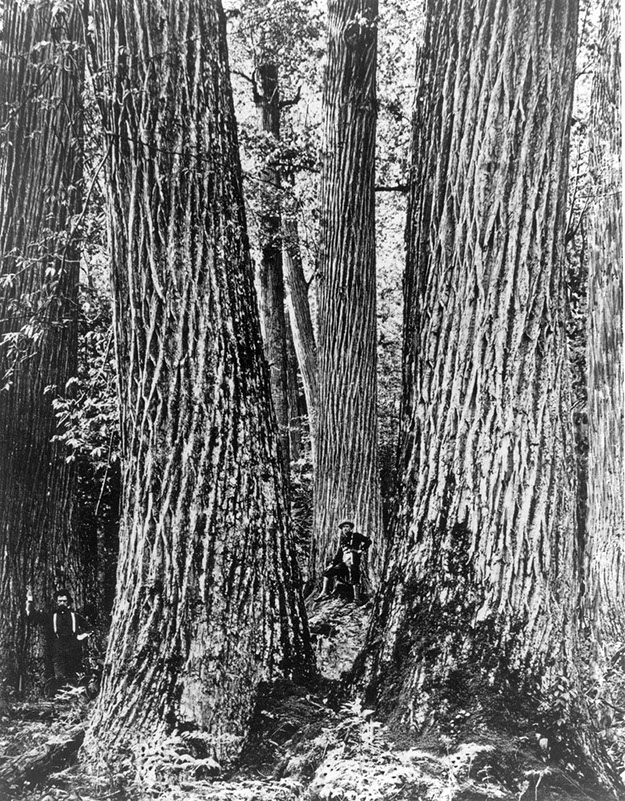

80 foot tall towering American Chestnuts were once a staple of life for people across Appalachia and elsewhere in the Eastern United States. (American Chestnut Foundation)

CURWOOD:

“Under a spreading chestnut tree the village smithy stands;

the smith a mighty man is he with large and sinewy hands.”

CURWOOD: So begins the classic poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1839, but if Longfellow were alive today he would be hard pressed to find any immense chestnut trees in his hometown of Cambridge, Massachusetts. The mighty American chestnuts that once made up nearly a quarter of eastern forests in the U.S. are now all but gone, thanks to a blight inadvertently imported from Asia in the early 1900s. But now botanists are working to bring back the American chestnut by breeding in resistance to the Asian blight. And nowhere is their work more anticipated than in the hills of Appalachia deforested in the quest for coal. Reporter Jonna McKone has our story.

MCKONE: Thick stands of tall, regal chestnut trees, sometimes called the “Redwoods of the East,” once dominated the forests of the eastern United States. Michael French is a forester with the American Chestnut Foundation.

Mountaintop removal coal mining removes all the soil and vegetation off the surface of a mine to get the coal underground. (bigstockphoto.com)

FRENCH: The old-timers used to the say that when the chestnuts were in bloom in June and July it looked like the ridge tops were covered with snow because of all the chestnut flowers.

MCKONE: These days it looks very different. Not only are the chestnuts gone but from where I’m standing on a mountaintop in Dickenson County, Virginia, the rolling green mountains that stretch into the distance also bear the scars of a history of coal mining. And you can hear the next peak over being torn apart for coal.

[DISTANT RUBBLE FALLING]

HALL: We have some active mountaintop removal just on the next ridge over.

MCKONE: Nathan Hall is reforestation coordinator for Green Forests Work, a non-profit that helps restore former coalmines by planting hardwood trees.

HALL: So there’s rock trucks dumping out big loads of what they call overburden . . . that’s it falling down the mountain right there…. [DISTANT RUBBLE SOUNDS] . . that’s a big chunk of mountain sliding down . .

Chestnuts were once an important source of food for communities in Appalachia. (bigstockphoto.com)

MCKONE: Across Central Appalachia nearly ? of a million acres of mountains have been strip mined for coal - that’s an area larger than the state of Rhode Island. Underground mining started here around the industrial revolution – but it wasn’t until the 1930s that surface mining became widespread. That process strips everything off the surface of a mountain using explosives and heavy equipment to access the coal underground. Dave Fisher, from Kentucky, is a farmer and small business owner who’s worked in coal mining for much of his life.

FISHER: Coal has fed my family; coal has fed generations. All my uncles are coalminers, my grandfather was a coal miner, his grandfather was a coalminer. It’s generational. That’s what we do. That’s who we are around here.

MCKONE: He’s seen first-hand the way mining changes the landscape.

FISHER: You would have huge tracts of land that all the dirt and rock and trees and everything removed and it was flattened out. You’re talking a quarter acre wide, a mile or two long of just big open fields . . .

MCKONE: Fisher says what’s not coal is just in the way.

FISHER: Anything over top of your coal they call it spoil. Cuz it spoils your coal.

MCKONE: As environmental awareness grew in the 1970s several key laws were passed including the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act or SMCRA. The law forced coal companies to fund the clean up of abandoned mines and the reclamation of active mine sites. Al Whitehouse, Director of Reclamation at OSM, the Office of Surface Mining, says early efforts didn’t consider restoring the ecosystem.

WHITEHOUSE: OSM and SMCRA had the belief that a surface mine when reclaimed should be smooth as the baby’s bottom as it were and that compacts it and it wasn’t the kind of land that was really the best for forests.

MCKONE: Whitehouse says the science and policy of restoration has improved -- today mountains must be returned to their ‘approximate’ original contour and fit a designated post-mining land use. But it’s up to private landowners to decide how the land is used after it’s mined.

WHITEHOUSE: The state has a role to make sure that the land capability is back but has no role in dictating what kind of economic interest the landowner pursues. That’s private business. If an old guy wants to raise dairy cows and wants a pasture that’s certainly one of the acceptable post-mining land uses. If that’s what he wants that’s what he’ll have.

MCKONE: At the Dickinson County site the post-mining land use was hay and pastureland. Nathan Hall from Green Forest Works looks out at the old mine.

HALL: Nowadays they’re using a better seed mix than they used to, but for years and years they would intentionally seed out what we see on this site which is Chinese Lespediza, European Fescue and various things that don’t belong here. That’s why we have this alien environment on most of these sites. It almost looks like it’s been painted green on those lower areas.

MCKONE: Kentucky business owner Dave Fisher says the coal companies wanted to reclaim the land as quickly and cheaply as possible.

DAVE FISHER: They just wanted the dirt to stay in place for five years so they could say ‘we done our part, there’s a hillside back and it’s yours.’

MCKONE: Restoration efforts didn’t make use of native plants and failed to understand historical land uses and culture of rural residents.

FISHER: When you look at a place that is undisturbed in this area, the plethora of wildlife and the different nut trees and the different essential plants that we have here – at one people made their living collecting ginseng, and yellow root and bloodroot. And none of that is ever put back on the mined land. Very seldom is any of the hardwood put back.

MCKONE: But hardwood plantings are increasing, thanks to the efforts of universities, environmental groups and landowners. Now some are hoping to restore former mines using native species including the American Chestnut. Fred Hebard is chief scientist with the American Chestnut Foundation. He says the chestnut tree was once a staple of life for people across Appalachia.

HEBARD: The logs provided fencing to keep the cattle out of their gardens and then lumber from cradle to grave. People would be rocked awake in a chestnut cradle, buried in a chestnut coffin and live in a chestnut house and shingled with chestnut bark.

MCKONE: Once some four billion Chestnut Trees blanketed the eastern US but by the end of the 20th century the tree was nearly extinct. An Asian fungus was to blame. In the early 1900's gardens full of exotic and ornamental species were all the rage. With imported plants came pests and fungus, including Cryphonectria parasitica, likely brought over on Asian nursery stock. Within 30 years the fungus spread from Maine to Louisiana killing nearly every towering and defenseless American chestnut in its path.

Though some American chestnuts survived for a few years before succumbing to the blight they all but disappeared from their range. As early as the ’30s scientists were working to bring the tree back from the blight but it wasn’t until the 1980s that scientists started backcrossing the American Chestnut with the Chinese chestnut, a tree that coexisted with the blight for millennia. Using the Chinese tree’s resistance to the fungus, they hope to eventually breed an American tree that can survive the blight. Again Fred Hebard.

Traditionally, mine site reclamation involved planting non-native grasses and few native species. (Green Forests Work)

HEBARD: The only thing you want from a Chinese chestnut is the blight resistance whereas you want to retain all the other characteristics of the American chestnut other than its susceptibility to blight. And you essentially want to throw out everything in the Chinese chestnut other than its resistance.

MCKONE: That’s because the Chinese tree is squat like an apple tree rather than towering and straight like the American tree. The backcrossed chestnuts at the American Chestnut Foundation research farm, in Meadowview, Virginia are essentially 15/16 American and 1/16 Chinese. Pathologist Laura Georgi is introducing the fungus to chestnut trees that contain a mix of Chinese and American genes. She wants to determine the most disease resistant individuals.

[SOUNDS OF MARKING THE TREES]

GEORGI: So this is where they were inoculated. We had two different strains that were inoculated of blight fungus. The lower is the more severe, the upper is the less severe strain. The lower site is a lot of dead tissue. The bark is sunken here. There’s orange and that’s the fungus. Up on top here – this is a little bit better looking.

MCKONE: Using trees bred at the farm, scientists are planting what they expect are blight-resistant seeds and saplings on former and active mines. Again, Michael French.

FRENCH: When you look at the range of the coalfields and the range of American chestnut, the two overlap almost perfectly. So if we can establish founder populations throughout the chestnut’s range on surface mines, it may help us to reach forests that we might not otherwise be able to plant in.

[WALKING]

MCKONE: So far tens of thousands of Chinese-American chestnuts have been planted. Back at the Dickinson County mine site, Michael French and Nathan Hall lead the way along a flat, barren-looking ridgeline to check on a recent planting.

FRENCH: Let’s walk up here actually...I’d like to take a look at some of my chestnuts. I want to see how they’re doing now that they’re leafed out.

MCKONE: The men stop to admire a small sapling.

FRENCH: Isn’t it beautiful? It’s almost two feet tall and only three months old. What do you think?

HALL: That’s from seed?

FRENCH: Yea from seed.

HALL: It’s nice.

FRENCH: There’s a good one there too.

MCKONE: They hope the chestnut population becomes self-sustaining.

FRENCH: So by mixing them in with other northern red oak, yellow poplar, sugar maple, all these species – we’ll be able to see: can the American Chestnuts outcompete the other species to where they’re able to flower and produce seed for squirrels, turkey, blue jay, deer? So that natural processes can continue, evolution, spreading the seed to other areas.

MCKONE: Early data suggests that well over 80 percent of the chestnut trees are surviving. In a few years scientists expect the chestnuts will start producing seeds to grow a second generation of trees. Nathan Hall looks at these mountains and sees unrealized potential.

Chestnuts, once known as the “redwoods of the east,” can grow to 80 feet tall. (American Chestnut Foundation)

HALL: As somebody that grew up here, most of my friends still live here, I see everyday the tremendous need for physical work for people to be engaged in, not only for the money aspect, but also to give people something to do and a sense of cultural identity. Because as the coal mining is moving away from this area, moving out west to Montana and Wyoming, we’re left with a big question of what we do. To me there’s a big opportunity to get people back to work doing restoration and remediation of these lands.

MCKONE: That could mean opportunities for jobs in tree planting, eco-tourism, growing nut and fruit orchards and even biofuel crops on old mines.

HALL: You don’t have anywhere near the economic potential for the region, for these areas that are just covered in a blanket of non-native species.

MCKONE: Dave Fisher is looking to the future as well. He recently started an farm and wants to install solar panels on a former mine.

FISHER: It’s a huge burden upon the people that’s left here after the coal is gone. What are we gonna do with this? It’s something that we really need to address.

MCKONE: The struggle over the costs and spoils of coal production is as deeply rooted in the region’s history as its small towns scattered through the lush hillsides. And the chestnut is part of that history. Reforesting former coalmines with native species is a long-term investment that could eventually mean the snowy white flowers of the American chestnut once more carpet the mountains throughout the eastern US. For Living on Earth, I’m Jonna McKone.

Related links:

- American Chestnut Foundation

- Green Forests Work

[MUSIC: T-Bone Walker “Strollin With Bone” from The Complete Imperial Recordings 1950-1954 (EMI Records 1991) Happy Birthday T-Bone Walker (05/28/1910 – 03/16/1975)]

CURWOOD: Coming up. An odyssey to photograph some of the world's oldest organisms. That's right ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis: “Le Petit Bal” from Ascenseur pour l’echafaud (Elevator to the Scaffold) (Fontana 1958)]

Beyond the Headlines

The Buddha statues from the Yungang Grottoes are becoming tarnished by China’s air pollution (photo: bigstockphoto.com)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Time now to dive beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra, publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org who joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. We’re going a little long on archaeology this week. Edward Wong, who reports for the New York Times on China, had a piece on some of the most unlikely victims of China’s awful pollution problems, and those victims are its centuries-old statues. Giant Buddhas, and even the famous Terra Cotta soldiers are being grimed and corroded by industrial smoke, but Chinese authorities have launched a two-pronged attack to save them – both restoring and cleaning the relics, and also limiting the nearby pollution sources that are threatening to destroy them.

CURWOOD: I think I know the answer to this, but just what are those sources?

DYKSTRA: Well, there are three main sources and those would be: coal, coal, and more coal. The coal from nearby mines, factories, power plants; the coal cookstoves still used in many Chinese homes. The burned coal eventually creates sulfuric acid, which can then fall as acid rain. The acid rain and a layer of grime from the air pollution can eat away at the monuments and statues, the majority of which are made of sandstone.

CURWOOD: Easily erodible and soft sandstone. So what else do you have in the way of eco-archaeology?

DYKSTRA: Well, eco-archaeology, try saying that three times fast... We’ve got another story from the wonderful publication High Country News – if you’re not familiar with High Country News, it’s kind of the New Yorker for people who live above the 7,000 foot-line out west. Native American artifacts, gathered for museum collections in the 19th and early 20th century, were routinely coated with very crude and dangerous preservatives and pesticides. High Country News reporter Joaquin Palomino said that in order to protect these relics from rats and other pests, the museums would coat them with stuff like arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and later on, they used gasoline and DDT.

CURWOOD: And of course, there’s the compelling argument that these things belong to the tribes, not to museums in the first place.

DYKSTRA: Well, absolutely, and places like Harvard’s Peabody Museum recognized that fact. They were helped by a little encouragement from a federal law saying that the museums had to return the artifacts. Museums are returning them to the tribes, but they’re returning them with a little poison coating. There are some antiquities experts that say without the toxic treatment long ago, the relics would have crumbled into dust, but it seems we’ve righted the wrong of plundered relics by returning them poisoned ones instead.

CURWOOD: OK. So we're looking back...how about the history calendar. What do you see there this week?

Aftermath of the Johnstown flood (photo: Willis Fletcher Johnson, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Well, I’ve got two historic accidents involving dams. 125 years ago this past week, there was a neglected dam that gave away on a summer resort lake and a wall of water roared down a valley. It leveled several small towns and then entered the city of Johnstown, Pennsylvania; the death toll was 2,200 people.

CURWOOD: And it also provided America with an early and hard lesson in keeping our infrastructure in good shape, huh?

DYKSTRA: Yes, absolutely, and when we see crumbling bridges and crumbling highways and coal-ash impoundment dams about to give away, it’s a lesson we seem to keep learning over and over again with great cost and with great pain. As far as the Johnstown flood goes, historian David McCullough wrote a great book about it several years ago, but it’s one epic American disaster that’s waiting to be made into a Hollywood blockbuster.

CURWOOD: Now you said you had two dam stories?

DYKSTRA: Yes, Sir, and please watch your mouth. In 1905, there were some workers who poked a hole in a retaining wall from an irrigation canal in Southern California bringing water from the Colorado river to new farmland. The water filled a huge depression in the desert floor and that became the Salton Sea, and in turn the Salton Sea became a tourist mecca, it became a stopover for migratory birds, and it is to this day the biggest lake in California.

CURWOOD: So there’s a dam-break story with a happy ending?

DYKSTRA: Not entirely. The Salton Sea’s water is not only very salty from the alkaline desert floor, it’s become polluted with farm runoff, and this man-made lake is the object of a major effort to save it. Not too long ago, there was a Republican congressman who was spearheading that effort, that was the late Sonny Bono.

CURWOOD: I imagine he would "Cher" the credit to that.

DYKSTRA: [groans] Oh, God. Oh no.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of Envrionmental Health News, EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks for taking the time with us today Peter.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Steve. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read about Archaeology’s poisonous past in High Country News

- Read about how China’s pollution problem is impacting ancient artifacts

[MUSIC: Third World “Human Marketplace” from 96 Degrees In The Shade (Island Records 1977)]

The Oldest Living Things in the World

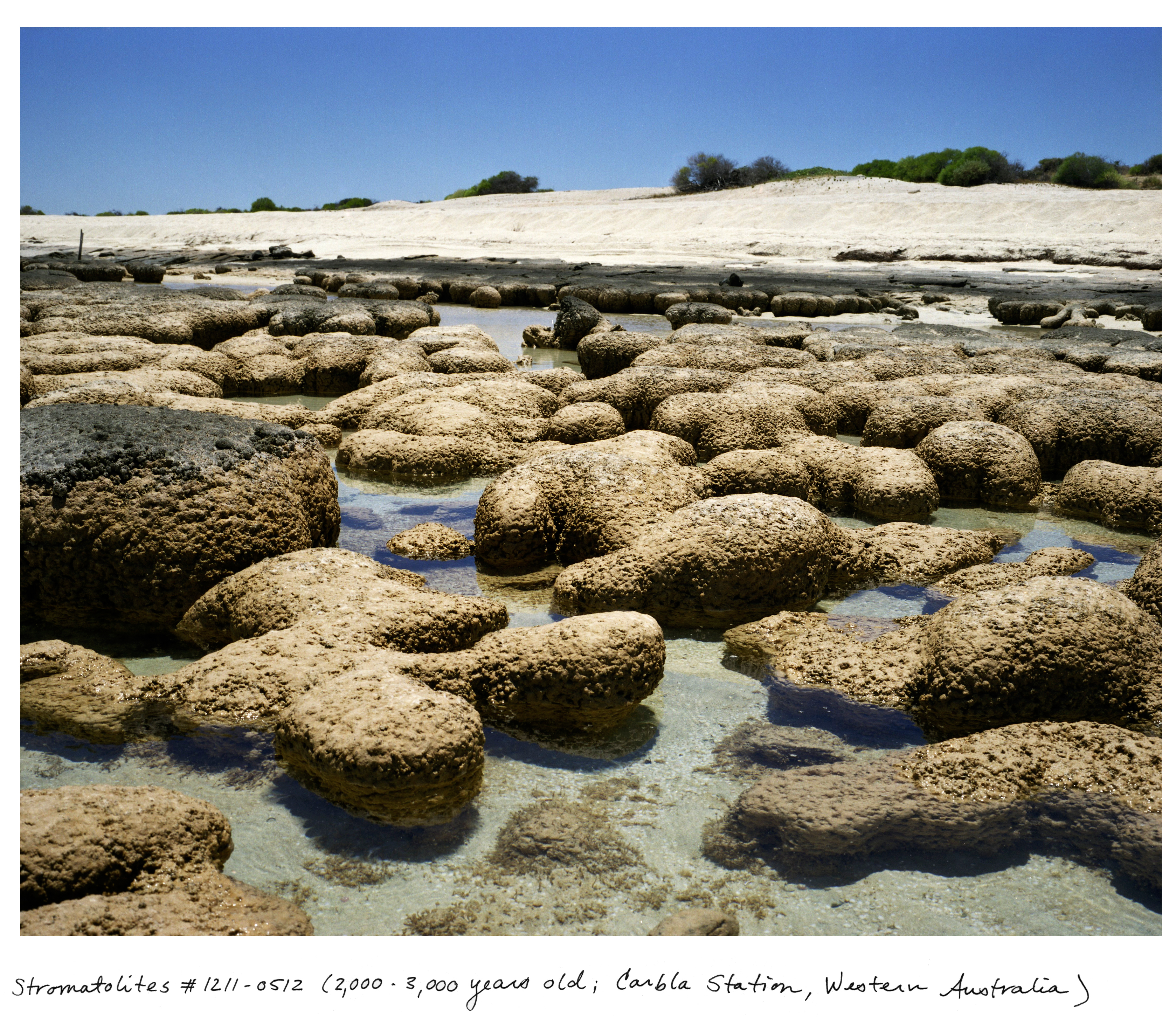

Stromatolites #1211-0512 (2,000 - 3,000 years old; Carbla Station, Western Australia) Straddling the biologic and the geologic, stromatolites are organisms that are tied to the oxygenation of the planet 3.5 billion years ago, and the beginnings of all life on Earth. (Photo: ©Rachel Sussman The Oldest Living Things in the World)

CURWOOD: The oldest person ever certified died in France in 1997 at age 122. The current oldest lives in Japan, she's 116. The maximum human lifespan seems to be around 120 years while the mayfly, an aquatic insect, emerges, breeds and dies within hours. But there are also organisms that can live for thousands of years, and these are the subject of a striking book of photographs by Rachel Sussman. A contemporary artist and photographer based in Brooklyn, Rachel Sussman spent the last 10 years traveling the globe, capturing images of the extremely old organisms. She joins us today to discuss “The Oldest Living Things in the World.” Welcome to the program.

SUSSMAN: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: So what inspired you to find and photograph the world’s oldest living things?

SUSSMAN: It’s really a combination of things. I've been photographing since I was little and always interested in the relationship between humanity and nature, but I was really interested in creating a project that dealt with the sciences as well as some philosophical thinking, this look at deep time and long-term thinking, all with a strong environmental underpinning.

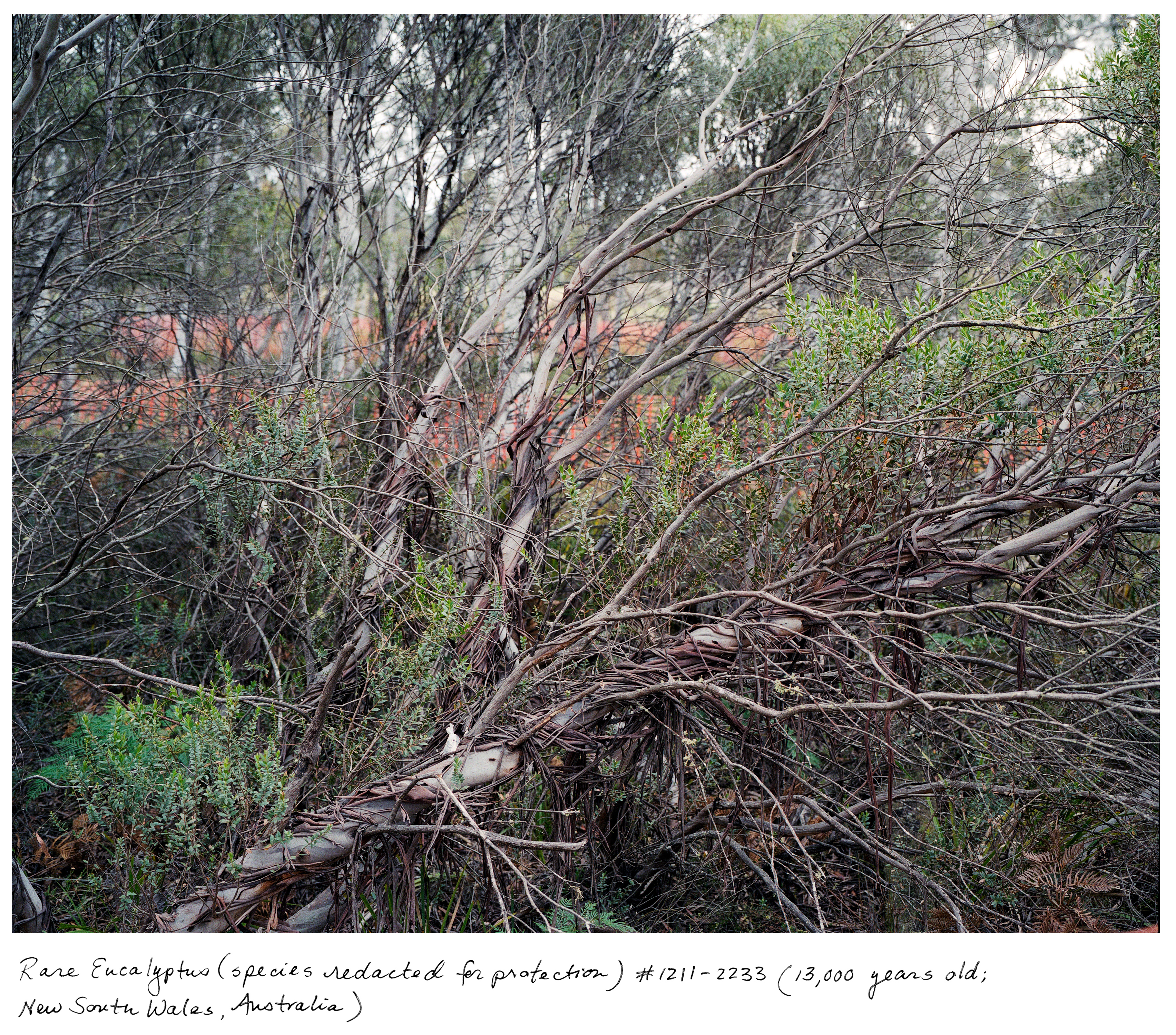

Rare Eucalyptus (species redacted for protection) #1211-2233 (13,000 years old; New South Wales, Australia)

This critically endangered eucalyptus is around 13,000 years old, and one of fewer than five individuals of its kind left on the planet. The species name might hint to heavily at its location, so it has been redacted. (Photo: ©Rachel Sussman The Oldest Living Things in the World)

CURWOOD: So the book is called “The Oldest Living Things in the World”. What kind of things are we talking about?

SUSSMAN: For the most part they are what you'd expect, a lot of plants, a lot of trees but there's also some things you might not expect, for instance, bacteria, fungus, as well as some animals.

CURWOOD: Going through your book, I noticed that you said you actually never found a true longevity expert, so how did you find these different organisms?

SUSSMAN: So very early on I had looked for a scientist that would collaborate with me and be my partner through the project and they very quickly recused themselves, and said, “Oh, no, we’re not expert enough for that because there is no area in the sciences that deals with longevity across species.” So what happened was I ended up working with individual experts.

CURWOOD: How did you determine the age of these organisms? Typically I imagine you used, you looked at different isotopes of carbon.

SUSSMAN: Certainly; well so this is actually a reason why the whole concept of creating an area of study about longevity is quite complicated, and that is, all these different types of organisms are dated in different ways. So the best-case scenario is when you have published scientific research papers that share an exact vetted age of an organism. In some cases there are educated guesses which are ranges and in some cases there's just some hearsay.

CURWOOD: There's two kinds of old in here: one kind refers to a single organism, another refers to things that are cloned. Can you explain the differences for us please?

SUSSMAN: Certainly, so there are these two types generally speaking that we're dealing with, and one is unitary organisms, and that’s something that we’re probably all most familiar with. A single tree is generally a unitary organism. So the more complex organisms are sometimes referred to as clonal or employing vegetative growth or rhizomatic and what that means is that they're self- propagating without the introduction of new outside genetic material, so there's no sexual reproduction happening.

CURWOOD: Most of your book is about plants but the very oldest aren’t. Can you tell me about those?

SUSSMAN: The very oldest known thing on Earth, and I say the oldest known because it doesn't mean that it is absolutely the oldest, is something referred to as the Siberia actinobacteria, and it does in fact live in Siberia and it's between 400,000 and 600,000 years old. This bacteria was discovered by a team of planetary biologists looking for clues to life on other planets by visiting one of the harshest areas on Earth. So what they did was they took a core sample deep into the permafrost and were quite surprised to discover this bacteria because what's special about it is that it's doing DNA repair below freezing so that differentiates it from bacteria found in the Arctic and Antarctic that's been dormant.

CURWOOD: I was intrigued by the photograph you have of these lichens on Greenland. How did you go about finding them?

SUSSMAN: So the researcher who was working with me with the Siberian actinobacteria said, “Oh, you're interested in things over 2,000 years old. I'm going to Greenland next summer, and there are lichens over 2,000 years old” and asked if I wanted to join them. So the lichens are known as the map lichens, Rhizocarpon geographicum. In Greenland they grow one centimeter every hundred years, and that's one of my favorite statistics in the whole project, and that really puts a human lifespan into perspective. I mean, what if you spent your entire life just growing one centimeter?

CURWOOD: There are pictures of the seagrass in Spain that you say is some hundred thousand years old…how did you get those pictures?

Posidonia Oceania Sea Grass #0910-0753 (100,000 years old, Balearic Islands, Spain)

At 100,000 years old, the Posidonia sea grass meadow was first taking root at the same time some of our earliest ancestors were creating the first known “art studio” in South Africa. It lives in the UNESCO-protected waterway between the islands of Ibiza and Formentera. (Photo: ©Rachel Sussman The Oldest Living Things in the World)

SUSSMAN: [LAUGHS] I learned to scuba dive. So that was one of my fears I actually had to face. Scuba diving was not something that ever appealed to me so it was quite fortunate I was able to join them in the field, so I ended up going out with the researchers as they were very carefully counting these plotted areas, counting the number of shoots to look at the health of the meadow.

CURWOOD: Most of these old things are pretty laid back, but you found one that you call predatory. What is that?

SUSSMAN: Yes, I mean, not that anybody should run away in alarm. Armillaria fungus is predatory but it only attacks certain species of trees, so this is also known as the humongous fungus which some people might have heard about living in eastern Oregon. It happens to be the largest organism in the world as well, but it lives almost entirely underground so it's a little bit tricky to photograph as you can imagine but what it does is it invades certain species of trees and essentially strangles them to death. But it's also pretty clever. It doesn't actually do this until the tree has met reproductive age so it ensures that'll be progeny for it to kill later.

CURWOOD: And how old is this humongous fungus?

SUSSMAN: The humongous fungus is 2,400 years old.

CURWOOD: A mere babe compared to the bacteria that goes back more than a half a million.

SUSSMAN: Certainly and it's an interesting thing where you have a number of the younger organisms in my project tend to be the larger ones, and the ones that are the oldest tend to be growing the most slowly.

CURWOOD: So what’s your most memorable event and thing and why?

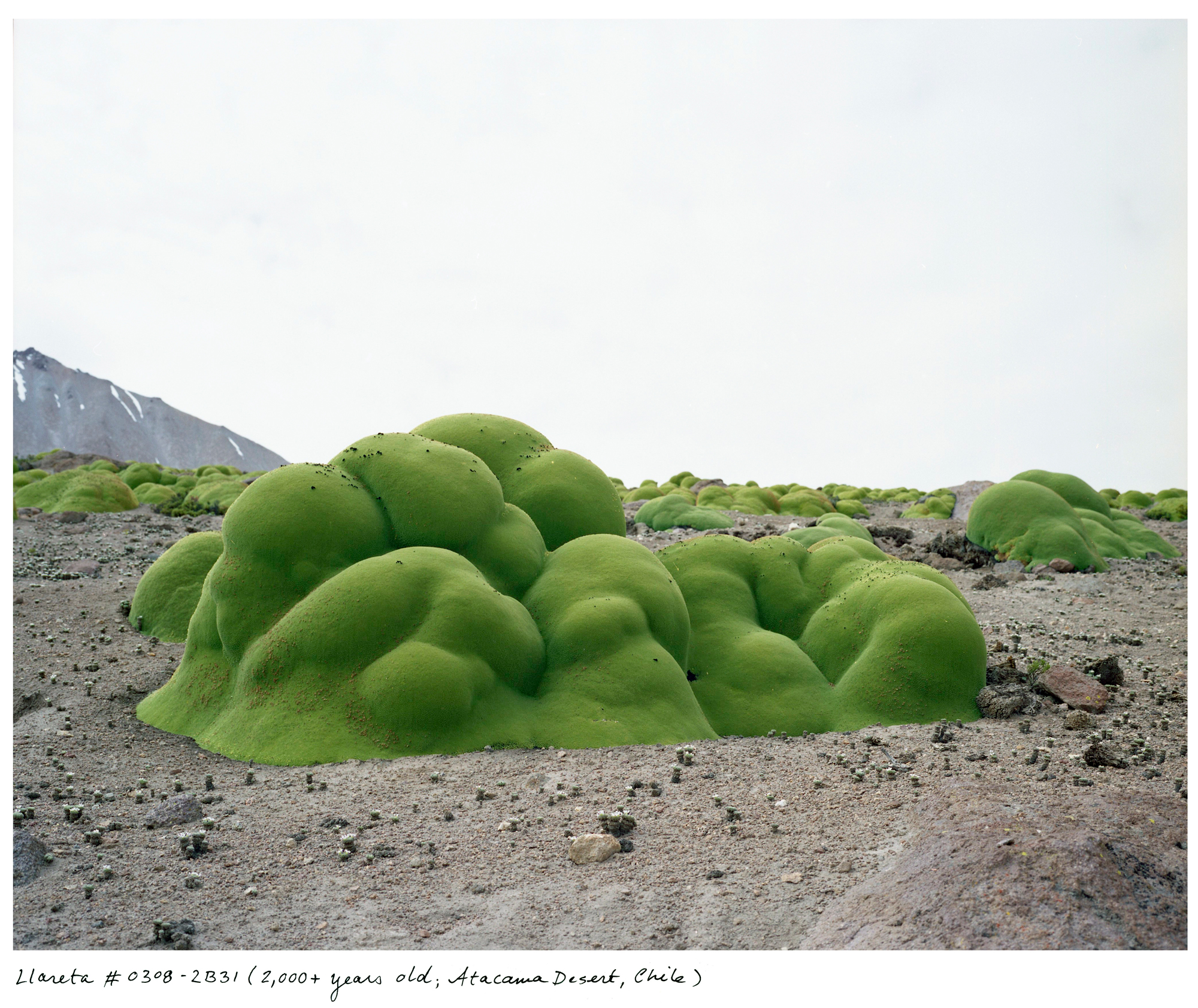

SUSSMAN: So one of my absolute favorite experiences was going to visit a plant called the llareta, in the Atacama desert in Chile. And this is in very high elevations around 15,000 feet and, you know, you’re driving through the Atacama desert, parts of this are absolute desert where there's no recorded rainfall in all of human history and so as you go further up into the mountains you start to get a little bit of green and finally I was with a researcher who took me to this place whether the llaretas were growing, and the llareta looks like moss covering rocks but it's actually a shrub and it's incredibly dense. It also happens to be related to parsley which I found amusing, but it's something that looks completely alien and you're already in this really alien looking landscape because it's so arid. But the llareta is made of thousands of these branches so densely packed together you could actually climb on top of them and at the end of each branch this little cluster of leaves and they also flower there, it’s a flowering shrub, and also became the poster child of the project because it’s something that most people aren't familiar with. I certainly was never familiar with them before beginning this project.

La Llareta #0308-2B31 (2,000+ years old; Atacama Desert, Chile)

What looks like moss covering rocks is actually a very dense, flowering shrub that happens to be a relative of parsley, living in the extremely high elevations of the Atacama Desert. (Photo: ©Rachel Sussman The Oldest Living Things in the World)

CURWOOD: How old is the llareta?

SUSSMAN: There are number of different llaretas that I photographed even, so the one primary image is probably around 3,000 years old, and then there's one that looks even bigger but it's actually two llaretas next to each other, so the estimate on that is around 2,000 years old.

CURWOOD: You went back to some of the sites. What was it like going back to see those organisms again and take more pictures and how did it change your experience of it?

SUSSMAN: Yeah, several of the organisms I did revisit. The most profound I would say was my experience at the Senator tree, and it was 3,500 years old. It’s a bald Cypress tree in Florida. I first visited the senator tree in 2007 and I had made some photographs that I just wasn't crazy about. And I thought, “you know what, I just got to come back. It'll be really easy.” Lo and behold, five years later, the tree was dead. It was killed by some kids who snuck into the park at night and the tree was hollow in the center and they thought it would be fun to duck in there and take some drugs and they burnt it down, but it really reminded me…it jolted me out of this sort of complacency or this feeling of like, “oh, these things are going to be around for so long I am making at sort of time capsule of this moment but they’ll be here for a while,” and in some cases that just isn't true.

CURWOOD: But what went away?

Antarctic Moss #0212-7B33 (5,500 years old; Elephant Island, Antarctica)

This 5,500-year-old moss bank lives right around the corner from where the Shackleton Expedition was marooned 100 years ago on Elephant Island, Antarctica. It was a victory simply being able to locate it. These days it's easier to get to Antarctica from space.

(Photo: ©Rachel Sussman The Oldest Living Things in the World)

SUSSMAN: So two of them we lost and they were both at human hands. So one was the Senator tree, and the other one was something known as a underground forest in Pretoria, South Africa. Now, thankfully it's not the only one of its kind but this was a 13,000-year-old clonal shrub living outside the botanical garden and it got bulldozed right over in order to accommodate a new roadway.

CURWOOD: Tell me, how do these oldest living things behave as "the record in celebration of the past, a call to action in the present, and a barometer of our future,” and I'm quoting you.

Rachel Sussman author of The Oldest Living Things in the World (photo: Laura Holder)

SUSSMAN: Certainly, yes, I mean, I really look at these organisms as something that belong to us all and transcend the things that divide us. They’re symbolic of both a deeper time period and history that is something collective to us living on earth and likewise something that we're responsible for and I find them both to be hopeful in terms of symbolically…their longevity is certainly something that is both surprising and admirable but it's also hanging in the balance. So climate change is a real and present danger and it's something that is in the hands of all of us. So I hope that these organisms will help to serve as something that connects us all and is transcendent of the small things that get in the way on the daily basis.

CURWOOD: Rachel Sussman's new book is called “The Oldest Living Things in the World.” Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

SUSSMAN: Thank you. It’s my pleasure.

Related links:

- Follow Rachel Sussman’s work on her website

- For more information on The Oldest Living Things in the World, visit the University of Chicago Press

[MUSIC: Miles Davis “Blues For Pablo” from Miles Ahead (Columbia Records 1957)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel and Jennifer Marquis all help to make our show. We welcome Jake Lucas and Abi Nighthill to our team this week. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page, it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER 1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment. Supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by a friend of The Nation, where you can read such environmental writers as Wen Stephenson, Bill McKibben, Mark Hertsgaard and others at TheNation.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth