June 20, 2014

Air Date: June 20, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

U.S. To Create World’s Biggest Marine Reserve

View the page for this story

U.S. TO CREATE WORLD’S LARGEST MARINE RESERVE: President Obama has announced plans to expand the size of the Pacific Islands Marine National Monument nine fold, to make it the largest marine reserve on the planet. Jackie Savitz from the environmental organization Oceana tells host Steve Curwood it's a big step for ocean conservation. (08:40)

Sick Sea Stars

/ Ashley AhearnView the page for this story

The sea star population off the Pacific Northwest coast is in trouble. Researchers suspect that warming waters and a pathogen in the food chain could cause this sea star wasting syndrome, as Ashley Ahearn reports. (05:00)

Camp Lejeune Water Pollution Victims Setback

View the page for this story

The Supreme Court recently ruled that a North Carolina state statute supersedes the federal Superfund law in cases of the timeliness of claims of damage by environmental pollution. This ruling appears to block lawsuits filed by military families who blame health problems on polluted water at the Camp Lejeune military base in North Carolina. Mike Magner, author of A Trust Betrayed, The Untold Story of Camp Lejeune, speaks with host Steve Curwood about the implications of this ruling. (07:40)

Nature’s Dividend—Pricing Global Ecosystem Services

View the page for this story

It’s easy for humans to forget that pollinators and trees and the sun work for free — they provide some of the many ecosystem services that benefit human well-being. Paul Sutton, a geography professor at University of Denver, has calculated a dollar price of these services, and explains to Host Steve Curwood how he calculated the value of these services. (07:20)

Adding Up the True (and Tricky) Cost of Carbon Pollution

View the page for this story

New analysis from the London School of Economics argues that the models currently used to calculate carbon pricing and taxes greatly undervalue the true costs and risks of carbon pollution. Host Steve Curwood talks with Charles Komanoff, Director of the Carbon Tax Center in New York City, about problems with current models and what a realistic carbon price might be in the face of global warming. (07:00)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about the NRA teaming up with the oil and gas industries, changes in worldwide coal consumption and a plan that once proposed damming New York Harbor. (05:20)

BirdNote on Burrowing Owls

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Out on the grasslands of the American West, the burrowing owl lives in the ground amidst prairie dogs and rattlesnakes. Michael Stein introduces us to this “priest of the prairie dogs” in this week’s Birdnote®. (01:50)

Digging for Owls

/ Jeff RiceView the page for this story

The rare burrowing owl lives underground and has numerous vocalizations, including a call that mimics rattlesnakes to scare off predators. From southern Idaho, producer Jeff Rice reports on his trip with a biologist to dig for the tiny owls. (04:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jackie Savitz, Mike Magner, Paul Sutton, Charles Komanoff,

REPORTERS: Ashley Ahearn, Michael Stein, Jeff Rice, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. The Obama Administration moves to expand a huge marine reserve in the Pacific and beef up federal programs to protect fish stocks and seafood consumers.

SAVITZ: We can make it so there's one of those codes you see, you can scan it with your phone, and you should be able to find out everything about that fish—what it is, where it was caught, when it was caught, what gear was used to catch it, and how it travelled from the boat through the supply chain to your plate.

CURWOOD: Also, why a biologist is reaching into a hole, even though he hears the sound of a rattlesnake.

[RATTLESNAKE SOUNDS]

BELTHOFF: There's a lot of rattlesnakes in holes and so any potential predator that's coming up on this hole and sneaking down the tunnel would actually think twice, perhaps, if he hears a rattlesnake in there. Certainly, I feel some trepidation when I’m reaching my arm down in there, and I hear those rattles. And I'm hoping it's not a rattlesnake.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

U.S. To Create World’s Biggest Marine Reserve

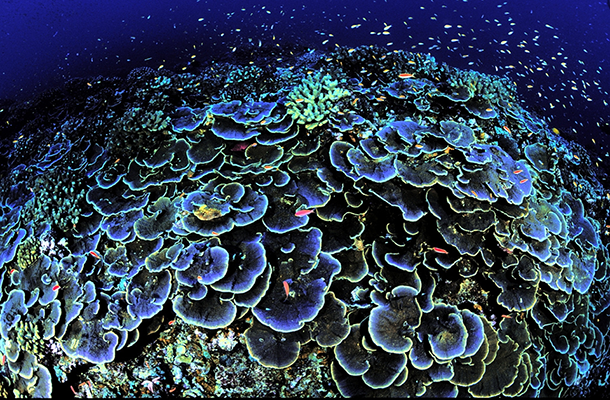

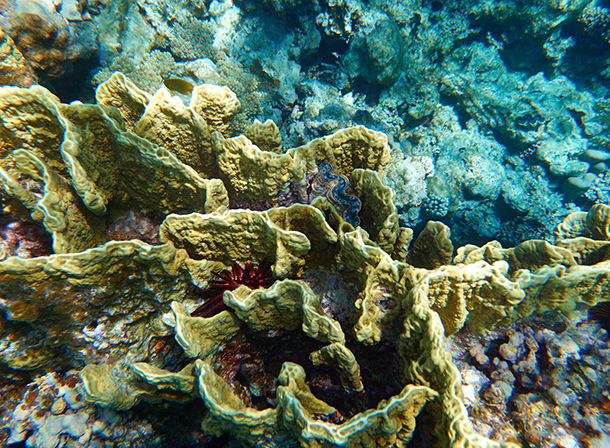

A Coral Reef in the Pacific Islands National Marine Reserve (photo: U.S. Fish and Wildlife, Jim Maragos, Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. President George W. Bush created a huge marine sanctuary in the Pacific Ocean, and now President Barack Obama says he wants to make it the biggest marine reserve in the world. For the President, protecting the ocean is a personal as well as an environmental imperative.

OBAMA: You know, growing up in Hawaii, I learned early to appreciate the beauty and power of the ocean. Of course we also know how fragile our blue planet can be. Rising levels of carbon dioxide are causing our oceans to acidify. Pollution endangers marine life. Overfishing threatens whole species, as well as the people who depend on them for food and their livelihoods.

CURWOOD: President Obama made the announcement as Secretary of State John Kerry convened diplomats, experts and advocates from around the world to work on ocean conservation by addressing marine protected areas, illegal fishing, false-labeling and ocean acidification. Jackie Savitz is the Vice President of U.S. Oceans for the non-profit, Oceana, and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth, Jackie.

SAVITZ: Thanks, Steve. Glad to be here.

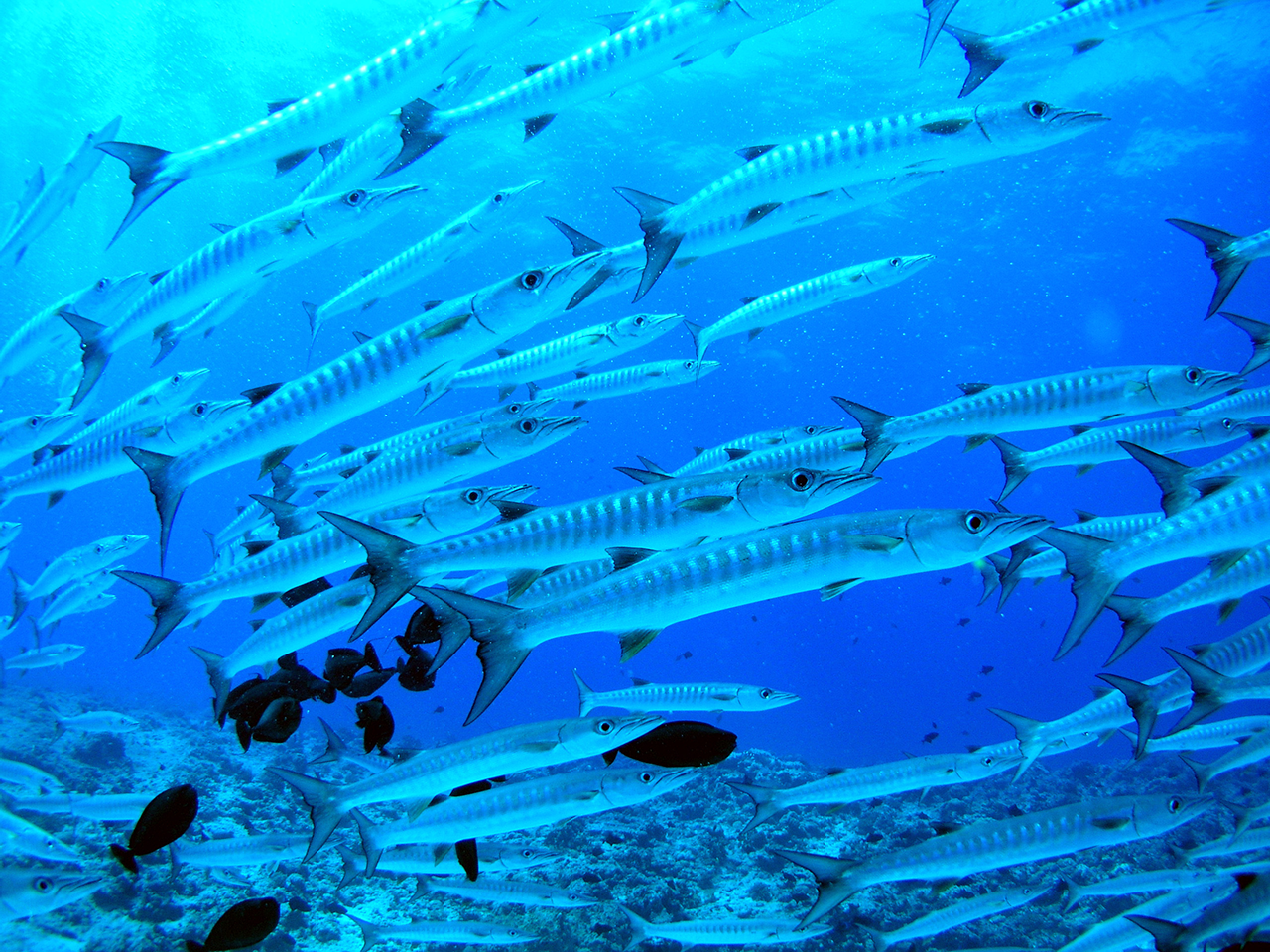

Protecting marine territory is a proven way to conserve fish populations. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

CURWOOD: So, President Obama says he wants to create a new marine reserve. What exactly is he talking about and how big would it be?

SAVITZ: Well, it’s actually a very exciting proposal. He's proposed to expand the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument from about its current size of about 87,000 square miles to nearly 780,000 square miles. It would make the Pacific Remote Islands Monument nine times the size it is today.

CURWOOD: How hard is it going to be for President Obama to make this enormous marine reserve happen? Who might be opposed to something like this, and what could they do to try and stop it?

SAVITZ: Well, we hope it won't be too hard. What he's supposed to do is to use the summer as a public comment period where he'll be able to take input from all of the stakeholders that might be interested, and that would include fishermen, both recreational and commercial fishermen, tourism interests, as well as environmental organizations like Oceana. Typically, what you see is, commercial fishermen are often opponents to this, and so they’ll have to take a look and see whether they feel it is a big imposition on them or not, but we have to keep in mind that these protected areas actually have benefits to fisheries. A lot of fish have larvae that are planktonic, which means that they kind of drift with the tides and the currents, and even sometimes the winds. And so what that means is that larvae that are spawned by fish in a marine protected area can actually end up growing up and living most of their lives far away from that area, and so that’s something that could benefit fishermen in the future.

While relatively small in size, the Dry Tortugas marine area in the Florida Keys has improved fish stocks throughout the region. (Photo: big stock photo)

CURWOOD: How effective is it to protect large tracks of ocean in terms of conserving marine species?

SAVITZ: Well, it’s been shown to be very effective. What they find is that you see an increase in both the number of animals that are in the area and also the diversity—the different types of species that are present—and diversity, of course, leads to a more stable community. A community that can be more resilient to impacts, like the impacts of climate change, for example, but the thing that people don't realize is that the protected areas can actually have impacts much further from the protected area than you might expect. And a really good example of that is, there was a study done in an area called the Dry Tortugas, which is just west of Key West in Florida, which is a marine protected area. And what they found there was that the entire region benefited, so not just the area west of Key West, but also all throughout the Florida Keys and even around to the east of the Keys on the way up to Miami.

CURWOOD: Now, there are a number of marine protected reserves around the world, some of them people say are really just lines on a map and not particularly well enforced; others do better with protecting the species there that they promise to protect. How does the United States enforce a protected area like this way off in the middle of the Pacific?

As much of a third of all fish sold in the United States is labeled as something other then what it is (photo: Oceana)

SAVITZ: That’s a very good question, and a very good point. Once an area’s designated for protection the next challenge becomes enforcement. It’s a big challenge, and people are starting to use things like satellite technology, radar, local knowledge—all kinds of new tools tied to technology. And I actually think in the next couple of years we’re going to see major advances in fisheries enforcement.

CURWOOD: Now, Secretary of State John Kerry invited a number of other countries to talk about conservation. What were the most important voices outside the United States that you heard at the Secretary’s gathering?

SAVITZ: You know, Secretary Kerry really did something unprecedented with this conference. At the very beginning, he opened the conference by saying, “I don't just want to talk. I want to actually get things done.” It led to a very long list of commitments that were made by the U.S. government, by President Obama and also by foreign governments that were here at the conference. A number of countries stood up, especially some of the island nations like Kiribati and the Bahamas, the Cook Islands, Palau, and they talked about the importance of protecting their fisheries, and many of them designated extremely large areas of their exclusive economic zones, in some cases their entire exclusive economic zones as marine protected areas, some of them with very strong restrictions on industrial fishing. And I think when you add them all up, you start to see a really important trend in protecting areas that can lead to great increases in the long run and fishery abundance in our ability to feed people protein from the ocean.

These are definitely salmon, but where did they come from? (Photo: Oceana)

CURWOOD: Now, President Obama has also announced that he wants a new federal program aimed at stopping illegal fishing and also seafood fraud. What would such a program like that do?

SAVITZ: Well this is a really important issue. As you know, what you're purchasing when it comes to fish may not actually be what you're getting, and we know this because Oceana did a study where we looked at 1,300 samples of fish, and only about two thirds of them were what they were marketed to be. And so the President announced that he'll set up a task force to curb illegal fishing and seafood fraud. And that’s something that Oceana is very happy to hear, and something that we've been very concerned about for some time.

CURWOOD: How big a deal is seafood fraud, do you think?

Jackie Savitz (photo: Oceana)

SAVITZ: Well, it depends on how you look at it. From a consumer standpoint, a third of what you order may not actually be what you're getting. That could have health implications, for example, if you're a woman of childbearing age and you try to order a low-mercury fish like grouper, but you’re served a high-mercury fish like tilefish, then it affects your health and potentially you’re baby's health. Similarly if you're a consumer that’s trying to order sustainable seafood and they serve you something that’s not sustainable, then it's taken away your ability to use your consumer power to promote sustainable fishing. The other big concern is that illegal fishing is responsible for as much as a third of the fish that are actually coming in, and that’s a big problem.

Dr. Kimberly Warner, Senior Scientist at Oceana examines a piece of fish (photo: Oceana)

CURWOOD: Defined for us what's an illegal fish?

SAVITZ: Well, if someone is fishing in an area where there's no fishing allowed, like in a marine protected area, or if they're using gear that is not allowed, such as driftnets which are very harmful to marine life and have been banned in a lot of areas, or they could be fishing without a permit, or they can be taking more than their limit. So there's a whole variety of different ways that fish can be caught illegally, and anytime that happens it undermines the management measures that have been put in place on purpose to make sure we take just enough fish so that the populations can continue to produce fish for the future. Now if we set up a traceability system so that all fish that comes into United States can be traced from boat to plate, we can make it so that there’s QR code, which is one of those codes that you see you can scan with your phone, and you can scan it, and you should be able to find out everything about that fish—what it is, where it was caught, when it was caught, what gear was used to catch it, and how it travelled from the boat through the supply chain to your plate. And you can see some of these QR codes at stores like Whole Foods where they actually sell some of these fish that are being voluntarily labeled with all this information, and that shows us it can be done. And it can be done throughout the entire fish market.

CURWOOD: Jackie Savitz is Vice President for U.S. Oceans for Oceana. Thanks so much for taking the time, Jackie.

SAVITZ: Thank you, Steve. It's my pleasure.

Related links:

- Kiribati’s commitment to expand its marine reserves

- Oceana’s website

- Jackie Savitz is the Vice President of U.S. Oceans at Oceana

- Read Oceana’s report on seafood fraud

- Secretary of State John F. Kerry's remarks at the State Department-hosted Oceans Conference

Sick Sea Stars

An ochre star's arm dangles by a thread, one of the signs of sea star wasting syndrome. (Photo: EarthFix/ Katie Campbell)

CURWOOD: Protecting vast areas of the Pacific Ocean round far-distant U.S. possessions may be an important key to conserving ocean species and biodiversity, but right on the Pacific Northwest coast, some beloved ocean-dwellers are in serious trouble. Scientists have been puzzled and alarmed to watch sea stars sickening and dying with a peculiar malady that makes them rip themselves apart. But now, as Ashley Ahearn of the public media collaborative EarthFix reports, science is getting a better handle on what exactly what is going on.

AHEARN: The village of Eastsound on Orcas Island draws thousands of tourists in the summer months. They come to see whales, bald eagles and, for avid beachcombers, sea stars. In fact, the little beach in Eastsound is a sea star hotspot. Thousands of them cluster in the nooks and crannies of this rocky patch of island coast. But that may not be the case for much longer.

HARVELL: Oh, boy. Well I’ll tell you, Ashley, it’s a lot worse than it was last week, which is what we expected but it still doesn’t help to see the future when you see it. Look at all these.

Morgan Eisenlord holds two juvenile starfish, one with abnormal limbs. She's looking for signs of how the next generation of young stars will be impacted by the wasting disease. (Photo: EarthFix/ Katie Campbell)

AHEARN: Drew Harvell has been studying marine disease for decades. She’s a marine epidemiologist with Cornell University and the University of Washington.

The Sea Star Wasting Syndrome has just arrived in the San Juan Islands after decimating populations up and down the west coast. Scientists think the cooler waters and swift currents surrounding these islands may have been protecting the population.

But now, the sun’s out. The water’s warming, and the sea stars are getting sick. Harvell points at a handful of orange and purple stars nestled into the rocks nearby. One’s arm is hanging on by a single gnarled string of flesh.

HARVELL: It kind of just looks dried out, wasted, thin, deflated. Sea stars are not supposed to look like that.

Drew Harvell, a marine epidemiologist, surveys the intertidal zone of Eastsound on Orcas Island, looking for signs of sea star wasting syndrome. (Photo: EarthFix/ Katie Campbell)

AHEARN: Last week when Harvell’s team visited this site they found one out of every ten stars was sick. Now almost half of the sea stars here are showing signs of the wasting syndrome.

HARVELL: Here’s a lesion on this one. Let’s get a picture of that. So that’s, kind of the next stage, is the appearance of lesions. And then, of course the bad part is the arms start to tear off.

AHEARN: Harvell says this is the largest documented marine epidemic in human history. Scientists have confirmed that there is an infectious agent to blame, but they’re not sure if it’s a bacteria or a virus. It appears to be transmitted through the water, or through physical contact.

HARVELL: Most of the stars in our waters probably have already been exposed‚ because if we bring them into the lab, and expose them to temperature stress, they get sick.

Drew Harvell, Cornell University (photo: EarthFix/ Katie Campbell)

AHEARN: Warm water stresses out sea stars, sort of like when you’re fighting a cold and you get overtired, and then the sickness takes hold. So the hypothesis is that warmer waters may not cause the disease, but they can exacerbate it. That hypothesis seems to hold true further down the coast. Carol Blanchette is a research biologist at UC Santa Barbara whose been following the disease outbreak there.

BLANCHETTE: Sea stars across Southern California, at least, have been pretty much wiped out at most sites and the period of time in which the disease has progressed rapidly has been a period of time in which waters have been warmer than usual winter conditions.

AHEARN: But there’s another new hypothesis that Blanchette wants to explore. She thinks there could be a connection to what sea stars are eating. UC Santa Barbara has an aquarium right on the ocean. The tanks are filled with seawater that’s pumped in, and the aquarium’s sea stars got sick at the same time as the nearby wild population did.

But then scientists noticed something interesting. In one tank, sea stars were being fed mussels that were harvested from the shore near the aquarium. In another tank the sea stars were fed frozen squid. The stars that ate the wild mussels got sick; the stars that ate the squid, didn’t.

BLANCHETTE: I don’t want to make too much of this because it’s a very small sample size, but it is interesting that there may be a link to acquiring the disease through the food that they’re eating.

Scientists inspect young starfish for signs of wasting disease. (Photo: EarthFix/ Katie Campbell)

AHEARN: As filter feeders, mussels could be concentrating the pathogen in their flesh, and sea stars eat a lot of mussels. So what happens if all the sea stars die off? They’re an apex predator—a keystone species.

BLANCHETTE: Losing a predator like that to the system is bound to have some pretty serious ecological consequences. And we really don’t know exactly what the system is going to look like in the absence of having these predators around, but we’re quite certain that it’s going to have an impact.

AHEARN: Scientists at Cornell hope to identify the pathogen behind sea star wasting syndrome in the coming weeks. Their findings will be submitted to the journal Science. Sea stars have survived mass wasting syndromes in the past, but no one has ever seen a die off as big as the one taking place on the west coast now.

Eastsound, Washington (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

I'm Ashley Ahearn on Orcas Island.

CURWOOD: Ashley reports for the public media collaborative, EarthFix. There's more at our website LOE dot org.

Related link:

Read more about the Sea Star Wasting Syndrome on EarthFix

[MUSIC: Horace Silver “Senor Blues” from Six Pieces Of Silver (Blue Note Records 2000 Reissue)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: putting a price on what Mother Nature does for us for free. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Horace Silver: “Song For My Father” from Song For My Father (Blue Note Records 1963)]

Camp Lejeune Water Pollution Victims Setback

Marines training at Camp Lejeune (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. If you look back over industrial history, there's no end of examples of dangerous toxic pollution. Some stand out as among the worst – for the U.S., think Love Canal. The military equivalent could well be the Marine Corps’ massive complex at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina. Over the decades marines and their families drank water loaded with toxic chemicals, and the bad water is now blamed for maladies that range from miscarriages to deadly cancers. And earlier this month, the U.S. Supreme Court set a precedent that adds insult to injury for the thousand or more of those victims and their families who have sued for damages. The court ruled that a local state statute takes precedence over the federal Superfund law when it comes to time limits on filing claims. Mike Magner is author of A Trust Betrayed: The Untold Story of Camp Lejeune and joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MAGNER: Oh, thank you. It's a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Mike, what happened at Camp Lejeune? Please set the scene for us.

MAGNER: Well, Camp Lejeune opened in 1941 to train marines for the beach landings that they would be doing during World War II, and it grew to the point where you could have 180,000 people or more on board at any one time. And what they were doing at the base in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s was what industries and military bases all around the country were doing—and that is throwing everything they had in terms of waste on the land: battery acid, used battery acid in pits, putting fuel oil on the roads to keep the dust down. They were spraying down equipment and tanks and vehicles with a highly toxic solvent called trichloroethylene or TCE because it took off all the grease and oil. There was also a dry cleaner at the base that was leaking perchloroethylene, another toxic solvent. And the problem with Camp Lejeune is that it’s right on the coast of North Carolina and the soil is all very sandy. So everything that you put on the land goes right down into the groundwater and they were using the most shallow aquifer for their drinking water at the base.

CURWOOD: So all these chemicals wound up in the drinking water for Camp Lejeune?

Supreme Court Justices of the United States (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

MAGNER: Yes - now not the entire system because they're more than 100 wells being pumped at this big base, but it did, in fact, contaminate about ten of those wells which happen to be in the most populated areas of the base.

CURWOOD: And briefly, what can these chemicals do to people?

MAGNER: There’s a wide range of effects from TCE—everything from liver cancer, leukemia, all kinds of various illnesses that you can't even describe. And, if a mother is drinking this water while she's pregnant, the effects on the fetus are terrible and we have a number of examples where children that were born at the base developed leukemia at an early age and many of them died.

CURWOOD: How many people were affected by this bad water at Camp Lejeune?

MAGNER: So it was a period of several decades and it's estimated that as many as a million people went through the base in that timeframe so there can be that many exposed to it.

CURWOOD: There are so many sad stories coming out of Camp Lejeune. Please tell us one.

MAGNER: One of them is Jerry Ensminger, who was a drill instructor at Camp Lejeune and a marine for almost 25 years, and he got pregnant—or his wife got pregnant at the base in 1975. And when that child was born she seemed quite normal, but at the age of six she was diagnosed with leukemia and she died at the age of nine. And it was not until 1997, when one the government scientific agencies put out a report that said that the contaminated water maybe link to childhood illnesses and Jerry saw that report on TV, and he actually spent the rest of his life campaigning on behalf of victims like him, demanding justice from the military and some kind of compensation.

CURWOOD: So how many people think that they were adversely affected by the bad water in Camp Lejeune?

MAGNER: There have been more than a thousand claims filed against the government demanding compensation for family members. Now, marines themselves are not able to sue the government for any damages that occurred while they were in the service, but veterans who were affected can go to the VA and can insist on disability payments. But these other several-thousand claims have been filed by marines on behalf of family members, like Jerry lost his daughter.

CURWOOD: And how are those people being helped at this point?

MAGNER: At this point they're not getting anything because the government is saying it's going to wait until all of the studies are completed—and the CDC, the federal science agency, is continuing to study links between the water and illnesses. And while those claims are pending, more than a dozen people have already gone to federal court to demand greater compensation and damages.

CURWOOD: Mike, what is the impact of the Supreme Court ruling?

U.S. Navy training exercises at Camp Lejeune (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

MAGNER: Well, the Supreme Court ruling wasn’t directly about Camp Lejeune, but it is about a case in North Carolina that involved similar toxic chemicals, TCE, which a company there dumped on the ground and it ended up affecting groundwater for a number of property owners. The case hinges on whether the Superfund law takes precedence over a state law in North Carolina called the Statute of Repose. Under that state statute, the company that was involved in the case argued that no one can sue them for any kind of environmental violations more than ten years after it occurred. Well, the property owners in that case didn't find out that their water was contaminated until, like, 22 years later. And they filed a federal lawsuit saying that, under the federal Superfund law, once you find out about contamination that affected you, you have two years from that point to file a case. And an appellate court ruled that the Superfund law did take precedence over the state law. And the government went to the Supreme Court on the side of the toxic chemical producer in North Carolina, and the Supreme Court ruled that the state law does take precedence over the Superfund law and that those people who filed claims more than ten years after the contamination are out of luck.

CURWOOD: Now, the Supreme Court ruling is on a different case than Camp Lejeune, but it sets an important precedent. What’s the impact of the ruling on the Camp Lejeune lawsuit?

MAGNER: The impact is that people who believe that they were harmed, or family members were harmed, may not be entitled to any kind of compensation because their cases could be thrown out.

CURWOOD: Now, what is to be done for these folks and their families that were so injured by the bad water at Camp Lejeune?

MAGNER: Well, I think one of the first things that needs to be done is maybe correct that law—that the Superfund law was not worded correctly to supersede the state Statue of Repose. So they could easily fix that if they can convince Congress to pass a law that makes that clear. Then their cases could proceed in federal court.

CURWOOD: And if nothing is done?

MAGNER: If nothing is done, those folks may be out of luck in terms of getting any kind of compensation for what happened, and the military will kind of walk away from many neglient acts without having to really pay for the people that were really harmed by it.

CURWOOD: Mike Magner is the Managing Editor of the National Journal Daily and author of A Trust Betrayed: The Untold Story of Camp Lejeune and the Poisoning of Generations of Marines and their Families. Thanks so much for taking the time today, Mike.

MAGNER: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read more about the water pollution at Camp Lejeune

- The Official site of Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune

- More about the Janey Ensminger Act

- More about the Caring for Camp Lejeune Veterans Act

- Victims of Camp Lejeune pollution: The Few, The Proud, and The Forgotten

[MUSIC: Horace Silver “Enchantment” from Six Pieces Of Silver (Blue Note Records 2000 Reissue)]

Nature’s Dividend—Pricing Global Ecosystem Services

Coral reefs provide homes to potentially millions of species, and they do a great deal to protect shorelines and sequester carbon—but their ability to do these things has been cut in half since 1997. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

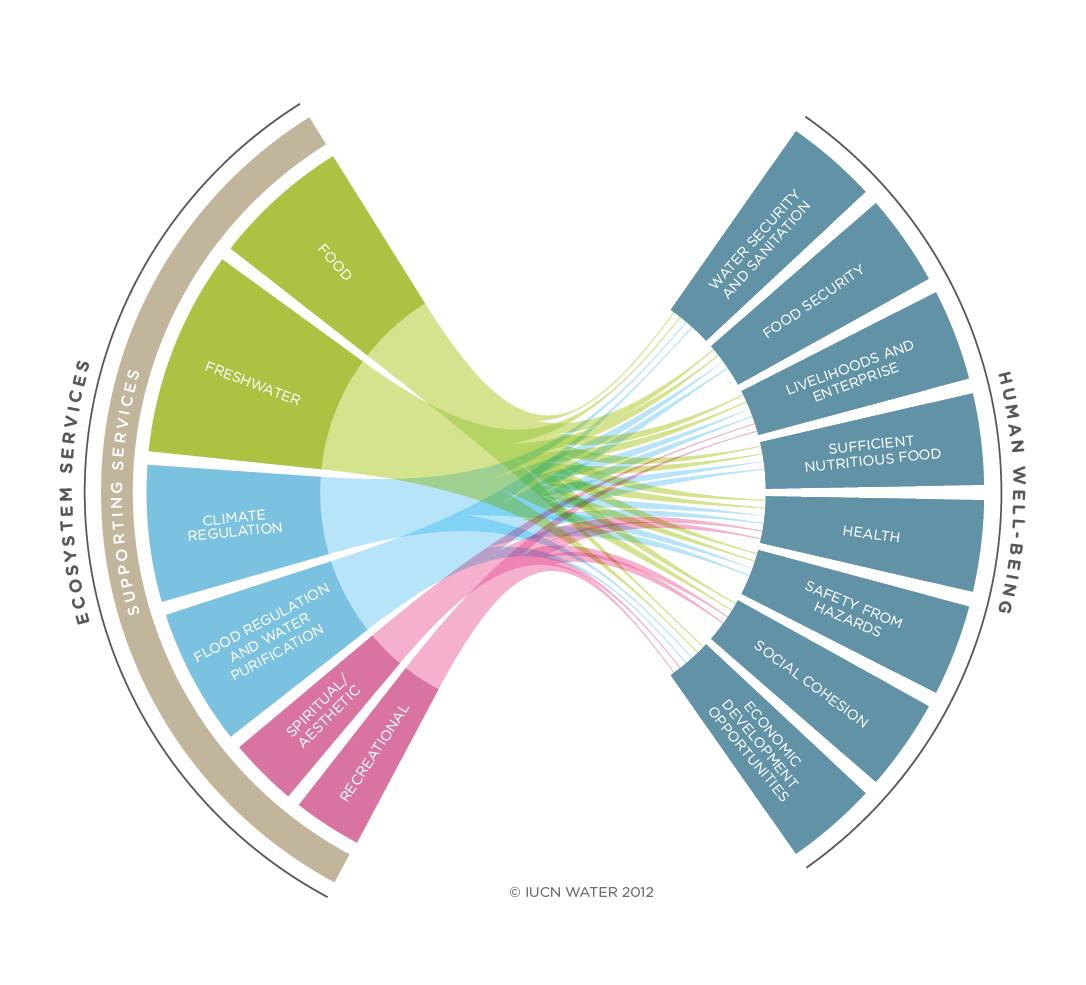

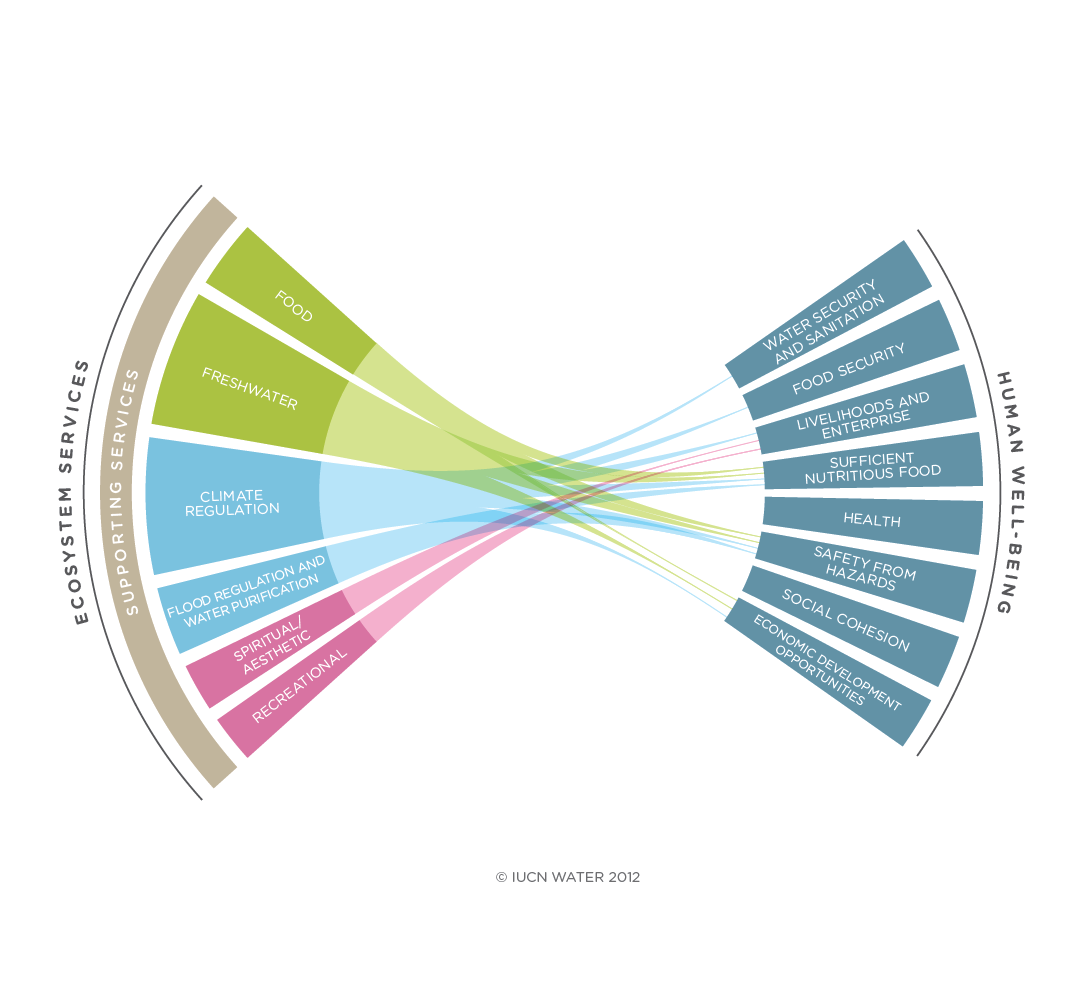

CURWOOD: Earlier in the program we were discussing the plans of the Obama Administration to protect a broad swath of the Pacific Ocean in part to help build up fish stocks. But some would urge us to take ocean preservation a step further, arguing that all fisheries in international waters should be shut down as the ability of the ecosystems of the high seas to store carbon dioxide is more valuable than all the fish caught there. But calculating the value of services provided free by the Earth’s natural resources is tricky, though Paul Sutton, Professor of Geography at the University of Denver, has done just that in a new paper published in Global Environmental Change. Welcome to Living on Earth.

Bees are responsible for pollinating about 80% of pollinated crops, such as apples, strawberries, avocadoes and grapes. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

SUTTON: Thanks, Steve. It’s a pleasure to be here.

CURWOOD: Paul Sutton, tell me, worldwide, what is the value of all the ecosystem services that the natural environment provides us?

SUTTON: Well, Steve, it’s amazing. The global value of all the ecosystem services provided by world is roughly twice as much as the marketed world economy. The sum of the Gross National Product of all the countries of the world is $70 to $75 trillion dollars, but nature is pollinating crops and protecting us from storms and producing fish and purifying water. And, if you price the value of all the things that nature does for us, it’s twice the size of the global marketed economy; it’s roughly $125 trillion dollars.

CURWOOD: You did the first round of your studies back in 1997. What’s really striking to you about your findings today compared to seventeen years ago?

A balanced ecosystem supports human well-being in many ways. (Photo: IUCN Water Programme 2012)

SUTTON: At the updated prices, we’ve lost $20 trillion dollars per year in terms of ecosystem services provided by nature. So that’s bigger than the economy of United States. That’s a huge amount of economic benefit that we are squandering.

CURWOOD: Where’s most of that value being lost?

SUTTON: Primarily, coral reefs, coastal wetlands and tropical rainforests.

A degraded system offers less benefit to humanity. (Photo: IUCN Water Programme 2012)

CURWOOD: And this is every year?

SUTTON: Every year, and this is a common question I get. This value, $125 trillion dollars per year—this is what bees have done for us this year, what wetlands have avoided in terms of storm damages this year. So it’s essentially the interest on natural capital.

CURWOOD: Well, let’s talk about a couple of the ecosystems that you took a look at. What about coastal wetlands and their ability to protect cities like New Orleans or New York from more severe storms that we’re seeing now with the changing climate. What are these wetlands worth?

SUTTON: Just the storm protection services provided by coastal wetlands was $23 billion dollars a year; so now an updated estimate of the value of wetlands was around $25 trillion in 2011.

CURWOOD: Now how do you come up with these figures? I mean, how do you calculate the value of a wetland?

Coastal wetlands reduce the costly damage of storms such as Hurricane Sandy. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

SUTTON: That's a really good question, and so let's talk about a particular ecosystem service provided by coastal wetlands—and an example would be storm protection. When tropical storms like Sandy hit, the damage they would have done is mitigated by the presence of coastal wetlands. And so what you need to do is take data sets like maps of the paths the hurricanes passed and then you need a map of the coastal wetlands. You also need a map of economic activity, and then you get the insurance company data that documents how much damage you really did experience as a result of Katrina and Andrew and Hugo and all those storms. And then you build a statistical model in which there's only two parameters that influence how much damage. There was wind speed—the higher the wind speed the more economic damage is done by the storm, and how much wetlands was in the swath of the storm. The more wetlands that are there, the less damage was done by the storm and when you apply that to all the storms over the course of the years, it works out to an average of about $23 billion dollars per year in reduced damage or avoided costs from hurricanes.

CURWOOD: Now, in many of these cases, I gather that the ecosystem service depends on the place that it’s in—the coastal wetland on a deserted island is not worth as much as something that’s protecting Charleston, South Carolina, for example.

SUTTON: Yes, so basically human wellbeing results from an interaction of human capital, built capital, natural capital, and social capital, and some of these things interact spatially and some of them interact in other ways. I mean, a storm is not going to do a lot of damage if there's nobody there. However, there are other ecosystem services like carbon sequestration where we're just happy to have any part of the planet pull carbon out of the atmosphere to mitigate climate change.

CURWOOD: Now how do you respond to critics who say it’s wrong to put a dollar value on ecosystem services? Mother Nature is here for us—it's our gift from our creator.

All of humanity benefits from ecosystem services, yet policymakers ignore the economic value in protecting nature. (Photo: epsos.de)

SUTTON: [LAUGHS] I think that's a totally legitimate criticism, and one way that criticism is put is, “All you guys have done is underestimated the value of infinity,” and I agree with that. I basically agree that Mother Nature, the natural endowment that we have been given by our Creator perhaps, is infinitely valuable. Water is infinitely valuable to you and you don't pay all of your income for water. So what we're really trying to do is to get the public to appreciate the relative contribution of the natural world to human wellbeing, and these findings are rough. They're probably an underestimate, but we’ve lost $20 trillion dollars in the last decade and a half. That should make someone concerned. We have people that are very concerned about the economy, and they go back and forth between Goldman Sachs and the Federal Reserve and the Securities and Exchange Commission. And they have the authority to print trillions of dollars, but we do not have anybody with that kind of political power to do anything to protect the environment—and the environment is worth more to us than marketed economy.

CURWOOD: So, Paul, now we have all this data. Now what do we do with it? How can we use this knowledge of the value of the environment in economic terms to take better care of it?

The beauty of nature is not measurable, but the services it offers us are. (Photo: bigstockphoto)

SUTTON: We know a lot of the things we need to do. We need to develop renewable resources and alternative energy. We need to provide family-planning to all people that want it. We need to decelerate the rate at which CO2 is increasing in the atmosphere. So all the answers associated with climate change are part of this problem. What we hope to accomplish with this kind of pricing of the planet is to speak in a language that policymakers understand, to help us recognize that we have a market failure that is larger than the size of the global economy. And hopefully we can think about ecosystem services in a way that they're considered as public goods that require new institutions for their maintenance, nurturing and preservation.

CURWOOD: Paul Sutton is a Professor of Geography at the University of Denver. Thanks so much for taking this time with us today.

SUTTON: It’s been my pleasure, Steve. It's always a pleasure to chat with you folks at PRI.

Related links:

- Read the ecosystem appraisal paper

- The 1997 study on valuing ecosystems

- Read the IUCN’s assessment of how ecosystem services contribute to human well-being

[MUSIC: Sutton: Ernest Ranglin “Dancehall Fever” from Memories Of Barber Mack (Island Records 1996)]

CURWOOD: Coming up: Digging holes in the ground in search of…owls? That's ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Horace Silver: “Que Pasa” from Song For My Fatther (Blue Note Records 1963)]

Adding Up the True (and Tricky) Cost of Carbon Pollution

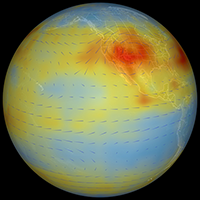

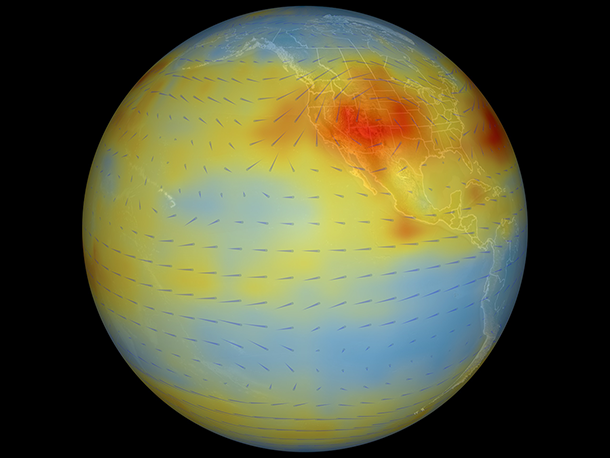

Companies are paying for their carbon emissions, but they may not be paying enough. (Photo: NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center Scientific Visualization Studio, NASA/JPL AIRS Project)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth; I'm Steve Curwood. Well, it's a pencil and paper program this week. From calculating the value of ecosystem services, we now turn to pricing carbon, or more precisely, whether current economic models place a realistic price tag on carbon. The new math comes from the London School of Economics Grantham Research Institute, where Nicholas, Lord Stern and Simon Dietz contend that current models grossly underestimate the actual risks and costs of global warming. If we want to have the market rein in carbon pollution, say Stern and Dietz, there needs to be a much higher price placed globally on carbon pollution. To get a handle on the economic models in play here, we called up Charles Komanoff, Director of the New York-based Carbon Tax Center.

KOMANOFF: There's one economist, a brilliant economist, Bill Nordhaus of Yale, whose work over the past 25 years is the basis of most of the governmental and official estimates of the economic cost of climate damage.

CURWOOD: What’s his method of figuring those costs, in layman’s terms?

KOMANOFF: Well, he’s got a model called the DICE model, and DICE is an acronym for Dynamic Integrated Climate Economy model. But you have to believe that Bill Nordhaus, when he came up with that acronym, had a twinkle in his eye because he knew that humanity was rolling the dice by continuing almost unabated to burn fossil fuels and pump climate disrupting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, but it’s a very nifty and widely used climate model. But as this new report from London is showing us, there are several key dimensions that Bill Nordhaus of Yale did not fully include in his DICE model.

CURWOOD: What’s the problem with this way of calculating those costs?

KOMANOFF: Well, there are three big flaws pointed out in this new report, and I think we should try to knock them out one by one.

CURWOOD: OK. Number one is…?

The dynamic integrated climate-economy (DICE) model bets on certain assumptions—and experts are now rethinking these assumptions. (Photo: Toshiyuki IMAI)

KOMANOFF: That the impact of climate change on economic activity in the DICE model ignored deliberately the impact of climate damage on the ability of economies to increase their technological capital, and the implicit assumption in the DICE model is that regardless of the level of climate disruption, technical progress is going to continue unabated. And when you think about it, climate change doesn’t just disrupt ecosystems, the disruptive effect of climate change is going to affect everything, including the ability of economies and innovators to generate new ways to produce economic growth.

CURWOOD: Alright, Charles, what’s the second shortcoming of the DICE model?

KOMANOFF: Well, the number two problem identified in this new paper, is tipping points. As global temperatures increase, there could be an almost, and are certain to be, some very unwelcome surprises that will act as really pouring more fuel onto the fire of climate change. One example is that as the permafrost in northern ecosystems melts, then methane hydrates—that have been stored for millions of years safely under the soil—will be exposed to the atmosphere, and we all know that gram for gram, methane is an even more potent warming gas than carbon dioxide. So that we could have a sudden and dramatic increase in the rate of warming beyond what a simple linear extrapolation would lead us to expect. And it’s this kind of tipping point that has been ignored in the DICE model such that, and you know, here’s the kind of nonsensical result from the DICE model: that the amount of temperature increase, according to the DICE model, that you would need to expect a halving of global economic activity, would be 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

The DICE model assumes that technology continues to progress at a certain rate, but with dwindling resources, it is possible that progress will slow. (Photo: Sarah Klockars-Clauser)

CURWOOD: That’s just unimaginable, isn’t it?

KOMANOFF: Yeah. I mean if you think about it, Steve, 32-degree average increase in global temperatures would pretty much make our planet uninhabitable, you know, let alone the impact on forests, on agriculture, on ecosystem services that the entire economy and human sustenance depends upon. That’s blatantly absurd.

The melting of permafrost releases carbon into the air, and this is one of many factors excluded from the DICE model. (Photo: Brandt Meixell, US Geological Survey)

KOMANOFF: The third exclusion from the DICE model, pointed out in this new paper , is the issue—we can call it “fat-tails” and it’s the fact that the DICE model is set up to produce only the best guess of what the impact on society and economic activity is going to be from a certain temperature increase. And it rules out “fat-tails” in the damage function to society. You know, you could think of “fat-tails” in terms of insurance. Nobody expects—when you think about what’s going to happen to you or your family in the next year—you don’t expect that your house is going to burn down, yet you have fire insurance. And so this new paper out of London is saying in effect that society needs to have an insurance policy to guard against these “fat-tails” of these unexpected ways in which a given amount of climate change is going to disrupt society.

CURWOOD: So then what does this paper from the London School of Economics propose as a solution to deal with the economic impact of climate disruption?

The DICE model excludes the “fat tail,” possibilities, or outcomes that are less likely but more costly. (Photo: David Hilowitz)

KOMANOFF: Well, you know, the paper is more about a rethinking of this influential DICE model, but they do make it clear that, if we are going to rely on a carbon price as the primary policy tool to change the economic equations and to hasten the de-carbonization of industrial activity so that we can really address climate change, then the carbon price-rate, or the carbon tax rate, is going to have to be at least several times greater than what middle-of-the-road economists and UN economists, what they have been willing to put out. So instead of say, a $20 or $30 dollar per tonne carbon tax as the optimal level, and the only question is: how do we get to that level; how fast? The import of this new paper is that the carbon tax rate is going to be triple digits, and the only question is: How fast do we get to triple digits, and how high up above $100 dollars per tonne do we take it?

CURWOOD: Charles Komanoff is the Director of the Carbon Tax Center in New York City. Thanks for taking the time with us today, Charles.

KOMANOFF: Well, Steve, thanks for the opportunity.

Related links:

- Read more about the paper from Dietz and Stern at the London School of Economics and Political Science:

- You can visit the Carbon Tax Center’s site here

[MUSIC: Horace Silver “Strollin” from Horace-Scope (Blue Note Records 1961)]

Beyond the Headlines

NRA, oil and gas industries team up to promote drilling (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: We check in now with Peter Dykstra, publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org for his take on what's shaking beyond the headlines. He's on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi there, Peter, what have you got for us?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. We're going to talk about big oil, big guns, and not quite so big coal.

CURWOOD: Well, tell me more.

DYKSTRA: The New Kid On the Block in cable news, Al Jazeera America, they’ve been doing some strong reporting on a lot of environmental topics. Most recently this week, there was a series by Jamie Tarabay on some strange environmental bedfellows. That includes a nonprofit whose membership consists of many hunter-conservationists, and the political muscle of Big Oil getting together.

CURWOOD: So you’re telling me big oil firms need bigger guns?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, well, the oil and gas industry is pairing up with the NRA. You got to remember the NRA is historically a hunter and firearms safety group. They’re also pairing big oil with the Safari Club International, and the reason for this, apparently, is to back members of Congress who want to roll back endangered species protections and open up more public lands to oil and gas drilling. There’s a recent report from the Center for American Progress that puts oil and gas contributions to the NRA as high as $5.6 million dollars in this past 2012 election cycle.

CURWOOD: So what’s the common bond between oil drilling and hunting?

DYKSTRA: Well, I’m not sure there is one, beyond a hostility toward protecting public lands and endangered species. Most hunters, of course, hold a very strong ethic about conservation—you can’t hunt wildlife, if there’s nothing wild out there. But there are some big-game hunters who chafe at the notion of regulations, so government intervention becomes a common enemy for big oil and, for some, big guns.

Coal consumption for power is at its highest since 1970 (photo: Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: So the enemy of my enemy is my friend, right? What’s next for us, Peter?

DYKSTRA: We’ve got some news from the front on the War on Coal, if there is, in fact, a War on Coal. Coal’s probably doing pretty well. Coal consumption worldwide rose by three percent last year; its market share of world energy production is at its highest level since 1970—this good news for the coal industry is according to the annual BP Statistical Review, which is considered to be an industry-standard report on energy use.

CURWOOD: So if someone’s concerned about climate change, this can’t be good news. But isn’t coal consumption going down in the U.S.?

DYKSTRA: It is going down in the U.S., but in the biggest economies of the developing world, coal is all the rage: China, India, even Pakistan last week announced a huge commitment to coal-based electricity. It’s even on the rise in Europe.

CURWOOD: So if coal is at thirty-percent worldwide, where does the other seventy-percent come from?

DYKSTRA: Well, oil is still the king. Its market share is dropping though; it’s down to about one-third, 33 percent, of global energy. Natural gas is rising, of course, due to fracking becoming more commonplace. And even though they’re still a small fraction of energy production, wind-farms rose by twenty-one percent this past year; solar jumped by thirty-three percent.

CURWOOD: OK, Peter. Well, take us back now for this week’s environmental history lesson.

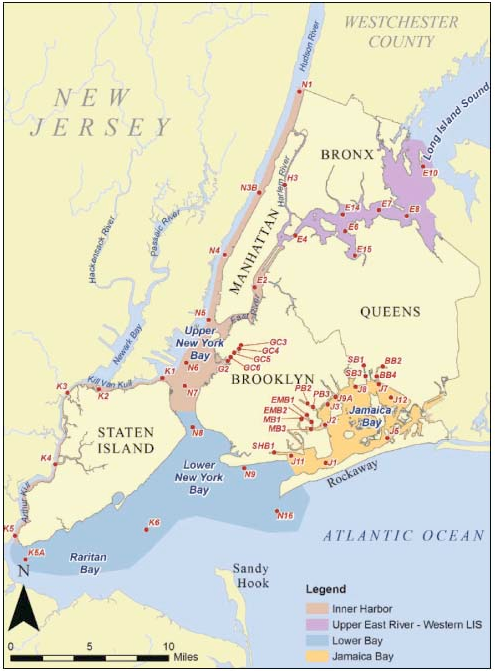

DYKSTRA: We got a little lesson in geoengineering, that’s when humans try to make things better by harnessing nature. A hundred and one years ago this week we learned of a grand, well-intentioned project that never happened, and it’s really a pretty good thing that it didn’t happen. June, 1913, the New York Times ran a great big story about a super-ambitious scheme to completely dam off all the entrances to New York Harbor and create a hydroelectric energy colossus. Those dams would also control floods, build a better seaport, repel invading foreign navies, and of course, they’d get rid of those, “unsightly and insanitary marshes and tide flats,” according to the Times.

CURWOOD: Whoa. Completely dam off New York Harbor and Long Island Sound?

Map of New York’s waterways and harbor (photo: NYC.gov)

DYKSTRA: With controlled access for shipping, but yeah, completely dam off New York Harbor and Long Island Sound. Tides around New York City can run up to about seven feet; they’re theoretically a great source of tidal power. But part of the rationale in this proposal from a century ago is, even then, they were saying we’re going to have to cope with running out of coal someday. And, of course the cost of damming off one of the largest estuaries on the east coast would have turned out to be an ecological nightmare. What they called those, “insanitary marshes”—they’re called wetlands today—they’re a breeding ground for all sorts of marine life. If you built dams all around New York, you’d trap the pollution behind them, and that would have helped make the whole New York metropolitan area, “unsightly and insanitary.”

CURWOOD: Of course, marshes and tidal flats protect against floods, and if there were more of them, New York might have done better when Superstorm Sandy hit, but the devil’s advocate argument here is that those proposed giant dams might have saved New York from Superstorm Sandy and made the whole region less coal-dependent.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, but I’ve got the devil’s advocate argument to your devil’s advocate argument, and that would be that New York Harbor would have turned into a fetid, polluted, managed bathtub that would been a whole lot less worth saving. Either way, this remarkable geoengineering scheme, via the New York Times in June, 1913, is linked from the Living on Earth website.

CURWOOD: That’s LOE.org. Peter Dykstra is Publisher of Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much, Peter, talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, talk to you soon.

Related links:

- Read the Al Jazeera America series about NRA pairing with oil and gas industries to promote drilling

- Coal consumption worldwide rose by three percent last year

- A BP Statistical Review of World Energy

- An old plan to dam off the New York Harbor and Long Island Sound for energy power

[MUSIC: MUX—BirdNote® THEME]

BirdNote on Burrowing Owls

A burrowing owl in flight near an artificial burrow. (Photo: Jim Belthoff)

CURWOOD: One of the pleasures we find in BirdNote® is learning more about some less-familiar feathered friends, and that's the case this week, with an unexpected underground owl.

Here's Michael Stein.

http://birdnote.org/show/burrowing-owl

BirdNote®

A burrowing owl spreads its wings to defend its home. (Photo: Jim Belthoff)

The Burrowing Owl

[SOUNDS OF COW, IRRIGATION IN EASTERN WASHINGTON]

STEIN: It is a warm May afternoon. As you take a leisurely drive through open grassland in the West, suddenly, a remarkable sight catches your eye—atop a fencepost on surprisingly long legs, stands a small, brown owl.

[BURROWING OWL CHATTERING]

Two burrowing owls meet near an artificial burrow. (Photo: Jim Belthoff)

STEIN: You’ve chanced upon a Burrowing Owl, an owl species most active during the day.

[BURROWING OWL COO-COOO VOCALIZATION]

STEIN: The ten-inch-tall owl bobs up and down on its legs, swivels its head, and stares back at you with large, lemon-yellow eyes. Fluttering up from its perch, the Burrowing Owl hovers twenty feet above ground, then drops, catching a large beetle in its talons. It flies to an abandoned marmot burrow, where it nests and avoids the heat of midday. Naturalist Hamilton Tyler noted that the Zuni people call the Burrowing Owl, “the priest of the prairie dogs,” because the owls live on peaceable terms with prairie dogs, rattlesnakes, and horned toads.

[BURROWING OWL CHATTERING]

CA burrowing owl leaves its nest to hunt for insects and rodents. (Photo: Jim Belthoff)

STEIN: The Burrowing Owl is in serious decline in the West, due to intensive agriculture, destruction of ground squirrel colonies and elimination of sage habitats. This charismatic owl, which migrates south for the winter, returns each spring to an ever-more uncertain fate.

[BURROWING OWL COO-COOO]

STEIN: I’m Michael Stein.

Burrowing owls nest with large broods, and are comfortable settling about 100 yards from their neighbors. (Photo: Jim Belthoff)

[BURROWING OWL COO-COOO]

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Calls of the Burrowing Owl provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Recorded by G.A. Keller.

LMS CD 25 T2 & 3 Irrigation ambient recorded by C. Peterson

A burrowing owl leaves its nest to hunt for insects and rodents. (Photo: Jim Belthoff)

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2014 Tune In to Nature.org May 2014 Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/burrowing-owl

CURWOOD: To see some photos of these interesting owls, burrow into our website, LOE.org.

[BURROWING OWL COO-COOO]

Related links:

- Read more about the burrowing owl on the Audubon Society’s page

- To learn more, check out the Burrowing Owl Conservation Network

- Hear more burrowing owl calls at the Macaulay Library

Digging for Owls

How many owls do you see? Two? Look down. (Photo: Ron Knight)

CURWOOD: But before you do, take a listen to a story from Idaho where one biologist has been studying these owls for years. Jeff Rice has our report.

RICE: It's well over a hundred degrees out on the Snake River plain in southern Idaho, and biologist Jim Belthoff is digging for owls.

[SOUND OF DIGGING]

RICE: This is a study site on the Snake River Birds of Prey National Conservation Area, a few dozen miles from Boise. The vast expanse of tan-colored soil and sagebrush has one of the densest populations of nesting raptors in North America. Today, we're hoping to find some rare burrowing owls.

[DIGGING]

BELTHOFF: The owls will be down here in this chamber.

RICE: Western burrowing owls are one of the smallest owl species and live in abandoned ground squirrel or badger holes in wide-open areas like this one.

[PASSING CAR]

RICE: The field is next to a highway and seems barren—mostly clay soil and hardly even any grass—exactly the way the owls like it.

The burrowing owl makes chuckling and cooing calls. (Photo: Neil McIntosh)

BELTHOFF: They like areas with very little vegetation—little or none actually is what they prefer. And the reasoning is that they like no vegetation so that they can see any ground dwelling predators approaching their nest, so they can get out of the way.

RICE: It's a strategy that works.

[OWL CALL]

RICE: A tiny brown and white adult owl, no more than ten inches tall spots us. He rises up on a pair of spindly legs, sounding a warning call.

[SOUND OF CALL, DIGGING]

RICE: The rest of the owls are hunkered down, but we know right where to dig. Belthoff, a professor at Boise State University, has built some artificial plastic burrows. The owls have moved in and he can dig down to the lid and open the den up without too much trouble.

BELTHOFF: Some footprints in front of this one, so we'll probably find some babies in here.

RICE: Belthoff reaches his hand into the den to retrieve a bird and suddenly…

[SOUND OF SNAKE RATTLE]

RICE: The sound is coming from inside the hole.

[RATTLING]

RICE: We know that this area is crowded with rattlesnakes, but Belthoff doesn't jump back. He reaches deeper into the hole, blindly feeling around.

[RATTLING]

RICE: He grabs something, coming out with a burrowing owl fledgling. The bird is about a month old. Its mouth is open, and it is hissing at us.

A juvenile owl, like this one, lives in a brood of 3-12 chicks. (Photo: Jim and Pam Jenkins, Smithsonian's National Zoo)

[RATTLING]

BELTHOFF: Burrowing owls have about seventeen documented types of vocalizations, of which this rattle call or hiss is one of them.

RICE: It's uncanny. Belthoff explains that it's something that only the juvenile owls will do. They haven't developed their ability to fly yet, so they need another way to ward off predators.

BELTHOFF: It's a case of what's called “mimicry” in animals in where, either the site of something or the sound of something sounds like something else and, in this particular case, it's a case of Batesian mimicry where the sound of something that's harmless actually mimics something that's harmful.

[RATTLING]

People hope to preserve this rare species by building safe habitats for them to live in. (photo: Chris Foster)

BELTHOFF: There's a lot of rattlesnakes in holes and so any potential predator that's coming up on this hole and sneaking down the tunnel would actually think twice, perhaps, if he hears a rattlesnake in there. Certainly, I feel some trepidation when I’m reaching my arm down in there and I hear those rattles, and I'm hoping it's not a rattlesnake.

[RATTLING]

RICE: The owl's mimicry is effective against predators like badgers, but it can't protect it from its biggest threat, bulldozers and creeping human sprawl. Burrowing owls are considered threatened or endangered in a number of western states. The owls tend to live on wide-open flat ground, a perfect place for shopping malls and parking lots.

[PASSING CAR]

RICE: That's why Belthoff is monitoring the birds—keeping track of their health and weight, and tagging them to study their migration patterns.

BELTHOFF: We band each one with an aluminum leg band, and then we give them three-color bands. So, then when they sit up on a perch, we can actually read those color-band combinations with a spotting scope. And we can tell whom it is we're dealing with without having to recapture them.

[DIGGING]

RICE: After the young birds are tagged, we cover up the owl den. An adult owl has been watching us from a fence post, probably the whole time. Its call, a bit less fearsome above ground.

[CHIRPING]

RICE: For Living on Earth, I'm Jeff Rice in southern Idaho.

Related links:

- Read more about the burrowing owl here

- Listen to more Burrowing Owl recordings by Jeff Rice on Montana State University's Acoustic Atlas

- Three juvenile owls mimicking rattlesnake sounds. Listen here.

[MUSIC: Horace Silver “The African Queen” from The Cape Verdean Blues (Blue Note Records 1966)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, Abi Nighthill, Jennifer Marquis and Olivia Powers all help to make our show. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page—it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more, www.stonyfield.com. PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth