August 1, 2014

Air Date: August 1, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Antibiotic Resistance and Livestock

View the page for this story

Antibiotic resistant bacteria sicken millions of people worldwide and some environmental organizations say part of the problem is indiscriminate antibiotic use in agriculture, and sued the FDA to require it to rein in this practice. A trial win was recently reversed by an appeals court. Meanwhile industry and the FDA crafted a voluntary agreement on antibiotics on antibiotic use in animal feed and water. NRDC attorney Avinash Kar, and Penn State Veterinarian Dave Wolfgang discuss the issue with host Steve Curwood. (08:50)

The Burden of Beef

View the page for this story

Beef may be what's for dinner but a National Academy of sciences report finds that beef is on average ten times worse for the environment than other meats. Food systems expert Anna Lappé discusses the beef burden and how to eat healthily with host Steve Curwood. (06:40)

Science Note: Reducing Bovine Belches and Global Warming Gases

/ Jake LucasView the page for this story

Researchers from Holland and around the world are developing a feed additive that reduces methane emissions from cows. Jake Lucas reports that the additive prevents microbes in bovine gut from making so much of the potent global warming gas. (01:40)

A Green Building Blooms in the Bronx

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Few think of affordable housing as a haven for nature in one of the toughest neighborhoods of New York City. But Via Verde, an energy efficient, garden-filled building in the South Bronx developed by the Jonathan Rose Companies and Phipps Houses, provides just that. Host Steve Curwood went to check it out. (11:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about a proposed coal mine in Australia, why kudzu is creeping North, and how Japan bounced back from war with whaling. (03:40)

American Catch

View the page for this story

Though commercial fishing is a multi-billion dollar business in America, much of the best US seafood heads overseas, while at home we consume cheap imported fish and shrimp. Author Paul Greenberg's new book, American Catch, describes what's gone wrong with our seafood supply and how it might be fixed. He discusses salmon, oysters and shrimp and the unraveling of America’s seafood industry with host Steve Curwood. (15:15)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Avinash Kar, David Wolfgang, Anna Lappé, Jonathan Rose, Paul Greenberg

REPORTERS: Jake Lucas, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Beef may be what’s for dinner, but if you count the environmental costs perhaps we should think twice before we slap that steak on the grill.

LAPPÉ: When I think about beef, I sort of picture it as like the Hummer on our dinner plate. Worldwide, about three-fifths of all agricultural land is used for pasture or for feed, but we’re only getting about five percent of the world’s protein from beef even though we’re using up all that land.

CURWOOD: The beef about beef. Also, why tenants are enthusiastic about their new homes in an affordable green housing complex in the South Bronx.

SANCHEZ: You know public housing. The devastation there is horrible; the drug dealing was to die. And three months before they sent me my letter of acceptance, somebody got shot right in front of my door.

CURWOOD: Green homes in the ghetto and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Antibiotic Resistance and Livestock

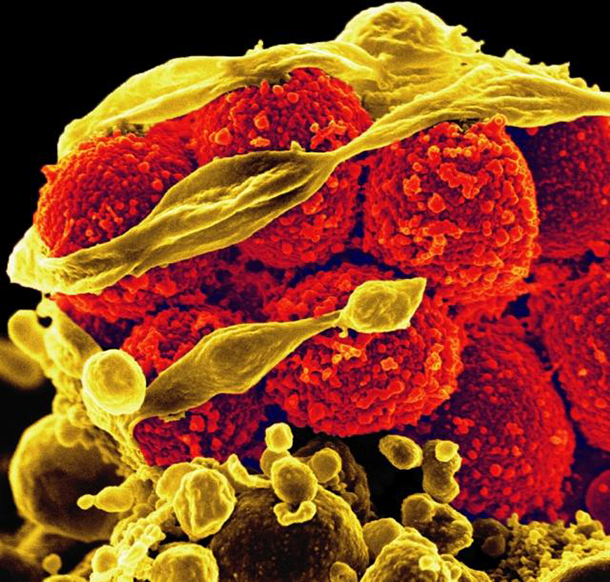

Scanning electron micrograph of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria (yellow, round items) killing and escaping from a human white cell. (Photo: NIAID)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Antibiotic-resistance is a global problem that can make it tough to fight bacterial infections. Superbugs like MRSA and some strains of E. coli and salmonella are now resistant to virtually all our drugs. Overuse and misuse by humans accounts for much of the problem, but back in 1977 the Food and Drug Administration began the process to regulate the vast amounts of antibiotics that were being given indiscriminately to farm animals to prevent disease and promote growth. Avinash Kar is an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council.

KAR: The fact is that 80 percent of the use of antibiotics in this country is in the animal sector. The CDC came out with a report last year that acknowledged that there’s strong evidence that the use of antibiotics in animals contributes to adverse health effects in humans: resistant infections account for at least 23,000 deaths a year and more than two million illnesses each year in the U.S.

CURWOOD: But the FDA delayed for decades issuing mandatory rules, so in 2011 groups including the Center for Science in the Public Interest, the Union of Concerned Scientists and the NRDC sued the FDA to force it to issue rules and won in federal district court. The FDA then decided to appeal, and in the meantime worked with farming and pharmaceutical interests to reach voluntary agreements on antibiotic use in animals. Now in a 2-to-1 decision, a federal appeals court has reversed the lower court orders. Again, attorney Avi Kar.

KAR: Well, the court did not dispute the scientific evidence that use of antibiotics in animal feed poses a risk for human health and FDA’s findings to that effect. What it did decide was that having concluded that there are risks to human health for such use, FDA need not take further steps to stop the problematic use and can move ahead with voluntary approaches or no action at all if it so wishes. And, you know, the dissent pointed this out in strong terms. It said that, “Today’s decision allows the FDA to openly declare that a particular animal drug is unsafe, but then refuse to withdraw approval of that drug. It also gives the agency discretion to effectively ignore a public petition asking it to withdraw approval from an unsafe drug.” That is essentially the effect of that decision.

Over 80% of antibiotics are used in the animal industry. The practice is cause for concern with respect to antibiotic resistance to bacteria that can infect humans. (Photo: stanzebla; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: What broader issues does this appeals court decision raise? You say that the court has said, “Look, FDA found a problem, but doesn’t need to do anything about it.” What kind of precedent has this kind of ruling set?

KAR: Well, for FDA, it means they can continue with their current approach, which is highly problematic. They’ve elected to follow a voluntary approach, and to ask drug manufacturers to voluntarily discontinue the use of antibiotics for speeding up animal growth. But there are a number of problems with that. One, it’s voluntary; so even though the companies have currently agreed to go along with FDA’s approach, they could back out at any time, and perhaps more importantly, the program is unlikely to lead to a reduction in the use of antibiotics. And antibiotics can continue to be used to compensate for conditions, and it involves the use of small doses of antibiotics in feed of large numbers of animals day after day. And it leads to the same kinds of consequences in terms of antibiotic resistance. Essentially, the same uses can continue under a different name.

CURWOOD: What does that tell you about protecting the public health of consumers?

Farmers often put low doses of antibiotics in their livestock feed to help with growth and the prevention of disease, but new policies on antibiotic are reining in indiscriminate use . (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture; Flickr Government Work)

KAR: What’s important to note here is that FDA can recognize that there’s a problem here. Even FDA’s current approach is based on the premise that the use of antibiotics in animal feed poses a risk to human health. And it’s just disappointing that the response to that problem has been inadequate to the task before them. Much more needs to be done. We need to take action to end the use of antibiotics in animals that are not sick. You know, we don’t add antibiotics to the cereal of children every morning to make sure they don’t get sick in daycare. We treat them when they get sick, and we should be doing that in the animal sector. We shouldn’t be adding antibiotics to the feed of animals day after day. We should be improving the conditions and then using them only when animals are sick. We need to preserve these medicines and preserve their effectiveness for when we really need them.

CURWOOD: Avi Kar is a lawyer with the NRDC. For a different view, we turn now to David Wolfgang, a veterinarian who teaches at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences. Dr. Wolfgang says the FDA has in fact been moving forward on this issue.

It was common practice for farmers add antibiotics to poultry feed and water. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture; Flickr Government Work)

WOLFGANG: In 2012, the FDA passed a guidance for the industry, which laid out a rather ambitious agenda and put more oversight into antibiotic use in our agricultural species. The next guidance for the industry issued by the FDA stated that the use of growth promotion from antibiotics would no longer be allowed in the United States. Antibiotic use will be overseen by veterinarians. There will have to be a diagnosis, or at least a tentative diagnosis of the condition in the animals that requires the use of antibiotics. And so this current ruling is allowing that change by the FDA to continue.

CURWOOD: One of the concerns that those petitioners raised about what the FDA is doing is it’s voluntary, that any day of the week a livestock producer could say, “Well, you know, I don’t like those rules. I just want to do my own thing.”

WOLFGANG: Well, again, “…do your own thing,” that was what we did in the past. The current regulations supported by the FDA does not allow producers to do their own thing; the old days of a farmer saying, “I don’t think my animals are doing quite right. I think a little antibiotics might help.” The current FDA ruling will eliminate that. Conversely, the new ruling will be, the producer will have to contact his veterinarian. The veterinarian would have to make a tentative diagnosis: “I believe your cattle are likely to become sick with pneumonia from disease X, and I think we can prevent that or control that by the addition of a product like tetracycline in the feed or water, and that, all those data—records, and careful supervision for residue and violations—all that will have to be maintained by both the veterinarian and the producer for up to three years after the animals leave the farm.

CURWOOD: So in your view, it doesn’t make sense to compel the FDA at this point to take stricter measures.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) oversees the country’s food safety procedures and policy, including antibiotic use in livestock. (Photo: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Flickr Government Work)

WOLFGANG: Correct. The Centers for Disease Control, a number of agencies within the United States have said that the major driver for antibiotic resistance in people is not in animal agriculture. There’s been very, very few direct links associated with the use of antibiotics in animals and use and development of resistance in people. Conversely, there’s been lots of resistance issues associated with excessive use in people, where people—products—cause resistance in people, then people share that. I believe that if you check the data, most of the driver in human medicine is driven by the use of antibiotics, often not even in the United States, in third world countries where people can buy lots of different antibiotics, use them for two, three or four days; two, three or four weeks. Now we have antibiotic resistance in people with bacteria that are adapted to people. If you look at the antibiotic use in the United States, most of the resistance issues are associated with people with chronic conditions—nursing homes, ICUs, places like that where very, very, very sick people get some really nasty bacteria that have some significant resistance. We don’t see those types of bacteria in our animals.

CURWOOD: David Wolfgang is a veterinarian who directs field studies and teaches at Penn State’s College of Agricultural Sciences. Well, if you’re confused, you’re not alone. This is an issue where there are divergent views about what the FDA is or is not actually doing to protect public health from the overuse of antibiotics in livestock. So far the NRDC has declined to say whether or not it would file further appeals, and run the risk of further adverse precedent. There’s also speculation of attempts to work out a settlement behind closed doors. For now, the public can only wait and watch. We’ll keep you posted.

Related links:

- The CDC’s Threat Report 2103 on Antibiotic/ Antimicrobial Resistance

- The Natural Resources Defense Council’s (NRDC) press release concerning this ruling

- Read the July 24, 2014 decision regarding NRDC v. FDA as well as the majority and dissenting opinions of the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

The Burden of Beef

CURWOOD: Well, however it’s raised, many Americans find a juicy sizzling steak hard to resist. But a study published in the Journal of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences shows that producing beef places a greater burden on the environment than, say, chicken or pork. Beef cattle require 28 times more land, and produce five times more greenhouse gases than other livestock. This is an issue that Anna Lappé, author of “Diet for a Hot Planet” feels strongly about.

LAPPÉ: When I think about beef, I sort of picture it as like the Hummer on our dinner plate; that’s a really inefficient way to get food from an animal. It takes about 30 calories of feed to produce just one calorie of beef, and so, when you think about that conversion ratio, it gets you thinking about how many resources are going in to produce beef. Worldwide, about three-fifths of all agricultural land is used for pasture or for feed, but we’re only getting about five percent of the world’s protein from beef. And beef is just an incredibly energy and resource intensive food production system.

Many, if not most American beef cattle are fattened up in feedlots on a diet of corn and soy before slaughter. (Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture; Flickr Government Work)

CURWOOD: Let’s talk about the resources that go into raising beef. What sort of things are used?

LAPPÉ: One of the reasons why beef cattle in particular has such a huge impact is because we are raising cattle today in feedlots, and so a big environmental impact is that corn and soy production—it's the water used to grow the corn; it’s the nitrogen runoff from those cornfields. So that's one of the main sources of impacts.

CURWOOD: Now how does beef compare to other meat production: chicken, pigs, and to the vegetarian options?

LAPPÉ: So when you're looking on average, comparing beef to other forms of meat that Americans typically eat, beef cattle uses about 11 times more irrigated water and produces five times more greenhouse gas emissions, and six times more nitrogen. Also, producing a pound of beef uses almost 50 times more water than growing a pound of vegetables, and about 40 times more than growing potatoes and other root crops, and about nine times more than grains.

Beef production requires much more land, energy, and water compared port and poultry production, according to a study published by the National Academy of Sciences. (Photo: theglobalpanorama; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: What proportion of crops such as corn and soy are grown to feed beef as opposed to people directly?

LAPPÉ: Less than one percent of the corn planted today actually is corn like you and I think of it, on the cob, we slather with butter and salt. About 50 percent of it’s going to feedlots, and a little bit less than 50 percent to corn-based ethanol. One of the elements of a feedlot is that you're concentrating all that livestock, which means you’re concentrating their waste—and I don't want it upsetting anyone’s appetite here—but when you concentrate that waste, there's going to be not just noxious fumes, but also you can actually see the bubbles popping on the top of these manure lagoons, releasing methane gas—a really intensive greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere. And corn and soy are incredibly hard for cows to digest because they weren't evolved to eat that diet.

CURWOOD: So why not just feed them grass instead of all that soy and corn?

Manure from feedlots is often is collected into lagoons that can emit methane, a powerful global warming gas. (Photo: Socially Responsible Agriculture; Creative Commons 2.0)

LAPPÉ: There’s a big movement to raise the alarm and say, “Let's bring cattle back to the land. Let's feed them what they are designed to eat, which is grass.” But we have to have a conversation about reducing consumption. We simply cannot produce 26 billion pounds of beef, which is how much we produce every year, at a sustainable level. So we need to reduce consumption, and we need to re-think how we are raising cattle, to integrate them into really thriving sustainable farms and that means feeding them grass, exactly, getting back on the land.

CURWOOD: And you're talking about America here?

LAPPÉ: Yes, so the United States is the world's single largest producer of feedlot beef. We export some of that but we consume a lot of that.

CURWOOD: So, Anna, you’ve given us the math about cow products having such a huge environmental cost, but at the store, relatively inexpensive, certainly compared to seafood, for example.

Cows belch methane, a heat-trapping gas, into the air. (Photo: Andy Muir; Creative Commons 2.0)

LAPPÉ: Economists like to call it the externalities, and I like to call it “the things that the producers aren’t having to pay for”. So that manure running off into our waterways or the nitrogen running off from cornfields and causing dead zones in the Gulf of Mexico—all of those environmental impacts are being paid for by us, the taxpayers, by cleanup dollars, by federal programs from the Environmental Protection Agency and so on. So there’s incredible costs of production that just aren't being born by the companies, and therefore, we don't see it on the price tag of beef at the supermarket.

CURWOOD: American culture likes beef. It's a big and important meal. “Bring on the steak,” many folks say. How do you make a cultural change to align with the things you're talking about it?

Anna Lappé is author of Diet for a Hot Planet, and co-founder of the Real Food Media Project and the Small Planet Institute. (Photo: Courtesy of Anna Lappé)

LAPPÉ: You know, I think the point isn't that were saying, it’s abstinence. We’re not saying, we all have to never eat beef again. It doesn't mean taking meat completely out of your diet or off your plate, but really thinking of beef as maybe a treat you give yourself sometimes, but not something you eat very frequently; and thinking about how to center your meals around plant-based foods; how to find incredibly rich protein sources from plant foods as opposed to meat. But the other thing that I like to remind people is that there are other things we can do to reduce our climate footprint of our meals, and that’s doing things like reducing the food that we waste, reducing the amount of food we eat that have been grown with fossil fuel intensive production systems. So we can also think about reducing the processed foods we’re eating. There’s a lot of ingredients in processed foods that also have a really big climate impact. It's really kind of the principles of good healthy eating that eating a healthy diet: means eating plant foods, vegetables and fruits, trying to eat foods in season, trying to cook your own food and to reduce the amount of beef on your plate as well. So these are choices that are really good for bodies and they’re also good for the planet.

CURWOOD: Anna Lappé is author of “Diet for a Hot Planet” and co-founder of the Real Food Media Project. Thanks so much, Anna, for taking the time today.

LAPPÉ: Thank you.

Related links:

- Read the National Academy of Sciences study that added up the beefy burden on the environment.

- Anna Lappé co-founded the Small Planet Institute with her mother, author and activist Frances Moore Lappé

- Check out our 1995 interview with Frances Moore Lappé

[MUSIC: – Beef: Captain Beefheart from Ice Cream for Crow]

CURWOOD: Coming up: A new affordable housing complex focuses on gardens and health to transform a tough neighborhood in New York City. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Kenny Burrell: Delilah” from The Artist Selects (Blue Note Records 2005)]

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Coming up: greening the South Bronx, but first we stick with beef for this note on emerging science from Jake Lucas.

Science Note: Reducing Bovine Belches and Global Warming Gases

Cows’ burps produce significant amounts of methane every year to the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Bigstockphoto)

LUCAS: If cows were more polite, we’d have one less pollution problem to worry about. Whenever cows let loose a little gas—particularly when they burp—they emit methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. In fact, the EPA estimates that burping cattle accounted for roughly two and a half percent of the total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2012.

It turns out, those potent burps come from interactions within a complex community of microorganisms in the cow’s gut. Some of those microbes break down cellulose, otherwise indigestible fibers that make up plants’ cell walls. That process produces hydrogen. Then, simple, primitive organisms called Archaea use that hydrogen and produce methane.

Petra Simic, the scientist leading DSM’s project. (Photo: Courtesy of DSM’s promotional video for the project)

Now, researchers led by Dutch scientists are developing a feed additive that inhibits some of those Archaea, to reduce methane emissions from cows. So far, the team has reduced methane as much as 60%, depending on which stage of milk production the cows are in, and this new process doesn’t interfere with the cows’ digestion or how much they eat.

The next step is to make sure the additive is safe for cows, workers who deal with it, and people who drink the milk. All they need now is to work on the cows’ manners.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Jake Lucas.

Related links:

- Read the EPA’s analysis of greenhouse gas emissions attributable to animal agriculture

- The website of DSM, the Dutch life science company leading the development of the additive

- A video from DSM on their methane project

A Green Building Blooms in the Bronx

Via Verde’s roof houses garden beds for its residents. (Photo: David Sunberg; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

CURWOOD: Much of the South Bronx in New York City was burned out during the 1970’s and in this birthplace of hip-hop music there is still a lot of poverty and a lot of crime, especially in terms of assaults and thefts. So you might think it would be the last place an idealistic, sustainable housing developer would plunk down a LEED certified $100 million housing complex, but that’s exactly what Jonathan Rose did in 2012. Phipps Houses and the Jonathan Rose Companies won a design competition to create Via Verde, an affordable, energy-efficient, mixed-use housing development in the South Bronx, close to public transportation. We met Jonathan in his office in Manhattan.

ROSE: The design is fantastic. It enhances the neighborhood. It’s a very, very green design. The building is tall on the north side and steps down as it goes further south. We did that on purpose to bring in as much southern sunlight as we could into the building. We really tried to weave this fabric of green and nature and communal activity throughout the whole building. One of the things we did is we brought in Montifiore Hospital as a tenant, and partner really. And so they have created a community health center at the ground floor of the building. The building is very green, but it also has a theme of health that weaves through its entire being.

The energy-efficient affordable housing complex, Via Verde, uses solar power and gardens on its rooftop help owners and renters save money and live healthily. (Photo: David Sunberg; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

CURWOOD: Via Verde means green way in Spanish, and that’s what strikes you when you walk in. There is grass and trees in a lush courtyard framed by a high-rise and a lower stepped building, where Living on Earth began its tour with architect Paul Freitag.

FREITAG: What I think the green way really is, if we want to start walking up a little bit, was this concept of recapturing the site that we’d be building the building upon, by actually creating a whole series of green roofs. As you visited these green roofs you’d actually be walking up through each of the gardens, and eventually you’ll end up all the way up on the seventh floor with a garden that’s right outside a fitness center.

CURWOOD: We’ve just come up the stairs -- to Christmas trees!

The South Bronx might be a rough area, but living in a space like Via Verde can help its residents rebuild a safer community. (Photo: David Sunberg; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

FREITAG: Right, so the stairs we actually came up on aren’t stairs, that’s an amphitheater. And so at the base we actually have a children’s garden and then there’s this amphitheater that looks out over the garden. The amphitheater’s been used for movie nights, for concerts, for different community events within the building. But then you come up on the amphitheater. We’re now on top of the second floor and here, we have our Christmas Tree garden, and this is actually the site of events that the building sponsors in December, where the residents come and they actually make decorations and decorate the trees, and they sing carols.

CURWOOD: So now we’re headed up another level.

FREITAG: Right, so this next garden is our orchard, and what we have up here is actually 12 apple trees, and these trees all bear fruit. If we were to be here in September, October, you would see them filled with apples and they will bloom, and they will be beautiful. So all the planters are actually benches, and so you can sit under the trees. And this is just a wonderful, sort of space in which you enjoy the trees and also see the fruit that they produce.

[SOUNDS OF CLIMBING STAIRS]

FREITAG: So we head from here up to the roof of now the fourth level. It’s really the signature garden for the project. This is what we refer to as the “community garden.” And what we have up here, you’ll see are a whole series of planting beds that are planted by the Garden Club of Via Verde.

CURWOOD: A garden club in the South Bronx.

FREITAG: Yes, it’s a wonderful organization. One of the real goals here was to create an opportunity, for particularly children, to see food grow, take pride in growing fine fruits and vegetables, and really understand the alternatives for healthy eating in comparison to, you know, fast food and other options which unfortunately are often more available here in the South Bronx.

CURWOOD: So how many folks live here?

FREITAG: Well altogether it’s 222 units. I would guess that that translates to roughly between 400 and 500 people actually living here in Via Verde.

A façade of solar panels helps to capture the sun’s energy and power the Via Verde complex. (Photo: David Sunberg; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

[WALKING UP STEPS]

FREITAG: So here we have our compost bins. And then here we also have our rainwater harvesting tanks. And as we walk up the next series of steps you’ll see how all of the south-facing walls of Via Verde actually have PV panels on them. At the entrance we actually have a readout panel that shows how much energy the building is generating at any point through its solar panels.

[FREITAG ENTERS CODE TO GET INTO STAIRWELL]

CURWOOD: So you have a sign here, by your stairs.

FREITAG: Right, so this is actually referred to as a stair prompt, these are generated by the New York City Department of Health. And it shows a sort of generic figure, I guess, very happily walking up the stairs and it says, “Burn calories, not electricity; take the stairs. Walking up the stairs for just two minutes a day helps prevent weight gain; it also helps the environment.” I think this sign in a very simple way shows the different strategies that you can use to have the building itself really promote the health of the residents.

CURWOOD: Penthouses are usually kept private for rich tenants, but the top floor of Via Verde is common space for anything from garden club meetings to receptions and birthday parties.

FREITAG: So here we are on the 20th floor and the views are spectacular.

CURWOOD: Whoa, look at this! You can see all the way over to the George Washington Bridge and downtown. Even the Empire State building sticks its head up and the new Trade Center building, is that possible to see? Yes it is, even, in the distance!

Many of the amenities on the outside of the building provide a service to Via Verde’s residents. (Photo: David Sunberg; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

[SOUNDS OF DESCENDING STAIRS]

CURWOOD: We head back down stairs to meet one of the tenants.

FREITAG: Hi, Ms. Sanchez?

SANCHEZ: Yes.

FREITAG: Hi, I’m Paul Freitag from Jonathan Rose Companies.

SANCHEZ: Nice to meet you.

CURWOOD: Hi, I’m Steve Curwood, from Living on Earth, public radio program.

SANCHEZ: Have a seat!

CURWOOD AND FREITAG: Thank you.

CURWOOD: So, can I ask your name?

SANCHEZ: Dalia Sanchez

CURWOOD: And how long have you lived here?

SANCHEZ: I think I was one of the first ones to move in.

CURWOOD: Why did you pick this place?

SANCHEZ: I have lived in housing for more than 20 years and, you know public housing. The devastation there is horrible; the drug dealing was to die. And three months before they sent me my letter of acceptance, somebody got shot right in front of my door. So I said, “I think you need to go.” And here I am, two years later.

CURWOOD: So, what’s it like?

SANCHEZ: Wonderful. I have no complaints because every time I call, somebody comes around and takes care of it. You give them a complaint and they come. So it’s pretty good.

CURWOOD: So tell me about your unit, you have one bedroom here?

SANCHEZ: It’s a one bedroom; it’s huge and comfortable. I was taken aback, you know; one-bedroom apartments usually are tiny. My bedroom is huge! I got plenty of space. The bathroom is comfortable.

CURWOOD: Now, there’s got to be something that’s a problem here.

Via Verde overlooks the city of New York. (Photo: David Sunberg; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

SANCHEZ: My only issue is that they came, and they took my Easter decorations last year. I was so angry. Then they come and take my Christmas decorations! But other than that, not a problem.

CURWOOD: Alright, well thank you very much. Very generous of you to open up your house like this.

SANCHEZ: Nice to meet you guys.

[ELEVATOR CHIMES]

CURWOOD: Back at the main entrance we meet a cheerful burly man who is busy accepting packages and checking to see that anyone who comes into the complex should be there.

ACEVEDO: My name is Julius Acevedo.

CURWOOD: How long have you worked here?

ACEVEDO: I’ve worked here for about a year. I’m the lead concierge.

CURWOOD: So what’s it like being concierge in the South Bronx?

ACEVEDO: Well, here it’s wonderful. The tenants here are terrific. The neighborhood is what it is, but we feel like we’re in a little bit of an oasis here, in the middle of the Bronx. This building is unique. We have owners and renters here, within the same facility. We’re all our own little community here; it’s phenomenal. The people love it, and I love working here. It’s just something different.

Inside a Via Verde apartment (Photo: Ruggero Vanni; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

CURWOOD: Worst thing about it?

ACEVEDO: I haven’t found it! [LAUGHS] If there was a downside, I wish there were more units available for the community. I have an inordinate number of people coming in here every day wanting to rent or buy. And it’s just, we’re full; it’s 100 percent occupied.

CURWOOD: Thank you very much.

ACEVEDO: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: Back at Jonathan Rose’s office in downtown Manhattan, he explains why he chose to develop a Via Verde in the South Bronx, famous for urban blight.

ROSE: The competition we won that led to Via Verde was led by Shaun Donovan, now the Secretary of HUD of the United States, then the Secretary of Housing of New York City. And he really wanted to see what was the best that could be done to advance community design, and to advance the greenness of design of affordable housing.

CURWOOD: How can green building help people of low and moderate income?

Via Verde’s apartments are designed with a theme of health and wellness in mind. (Photo: Ruggero Vanni; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

ROSE: Energy savings of both location and energy efficiency have enormous economic benefits to our low-income and working class families. Much affordable housing is of poor quality. That’s one of the reasons why it’s affordable. And many of the tenants are responsible for paying the utilities. What we’ve learned is if you can create a green building that’s really well insulated, that’s caulked and weather-stripped, the utility costs can be cut in half or two-thirds. That has enormous impact to their bottom lines. That may be the difference between whether they can afford to send their kid to an after-school program or not, whether they can sign up for healthcare or not.

CURWOOD: What does the location in community, the space a building occupies, have to do with its environmental friendliness and public health profile?

Apartments in New York are often small and cramped, but the one-bedroom units in Via Verde are spacious. (Photo: Ruggero Vanni; Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

ROSE: Locating buildings in denser communities with more services around them—such as schools nearby that kids can walk to, having mass transit that gives people easy and affordable access to jobs, to job training, to continuous education, to arts and culture—those have enormous social, communal, educational, and economic benefits. If a family lives in a city next to a subway line or a light rail line, or a bus line, it’s not only better for the environment but they personally are saving often $6,000, $7,000 or $8,000 a year. So one of the things that we’ve learned in creating great cities is how important social networks are. The people who now live there, they’re the ones who are gardening the building, creating events in the amphitheater. They’re the ones who have taken Via Verde and made it a real community. And so the building itself was just a well-conceived platform upon which they can then create the fulfillment of their lives.

CURWOOD: This is a time of great concern, whether it’s climate disruption, chemical exposure, unsafe streets. What can you in this world of green design do to respond to this rather deep anxiety in our society?

Via Verde was designed by Jonathan F.P. Rose (right) and Paul Freitag. (Photo: Courtesy of Jonathan Rose Companies)

ROSE: To questions like that I say, “The answer is urban.” If you go back to the very beginning of history and the reason why cities first emerged all over the world, they all emerged with a mission to actually create harmony between heaven and earth. They all grew up initially around a temple. A temple was always the first building in these very early cities, and the role was always somehow to harmonize these forces. And the role of their leaders was to harmonize these forces. Our cities again need to become the places that harmonize the forces of humans and nature to create happiness.

CURWOOD: Now the skeptics will say, “You can’t do that with steel and concrete.” And you would say?

ROSE: We have done it with steel and concrete! And we will continue, and we can only get better at it.

CURWOOD: Jonathan Rose is the Principal of the Jonathan Rose Companies. Thanks so much for taking this time.

ROSE: Thank you Steve, it’s a great pleasure talking with you.

Related links:

- Visit the Via Verde project’s website.

- Check out Jonathan Rose Companies’ website to see what else they have in store

- Check out the Phipps Houses website

[MUSIC: Robert Glasper “Why Do We Try” from Black Radio (Blue Note Records 2013)]

Beyond the Headlines

CURWOOD: Time now for our regular check-in with Peter Dykstra, the publisher of Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter, tell me, what’s lurking beyond the headlines today?

DYKSTRA: Well, hi, Steve. Let’s say you’re a major industrialized nation, and you just want to make a bold statement to the entire world that you’re totally flipping off climate change. What better way than to approve what could be the world’s largest coalmine?

CURWOOD: And what nation are we talking about?

DYKSTRA: Australia. This, on the heels of their abandoning their carbon tax. The Feds there just signed off on the Carmichael Coalmine and Rail project in Queensland, the state in the northeast part of the country. Sixty million tons of coal a year from just this one mine—and they’ve got maybe eight other projects backed up behind it—mostly or almost entirely for export to coal-hungry nations like India. The government sees it as a huge jobs project, but many others see it as a disaster on multiple levels. It’s your classic environmental conflict.

CURWOOD: So obviously, sixty million tons of coal a year leaves a bit of a footprint, but I gather it there are other objections to this project?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, one report says that mining in Queensland with this project in the lead will add as much carbon to the atmosphere as Australia’s climate plan claims it hopes to reduce. It’s a partly open-pit mine that will chew up immense amounts of land and groundwater. Exporting the coal means building a railroad to a coal terminal and then to shipping lanes, and that means dredging and dumping near the already-imperiled Great Barrier reef. It’s kind of a negative environmental Grand Slam down under. But, I’ll tell you what, let’s move on to a story that can unite me all, here in Georgia, with you all, up in Massachusetts.

CURWOOD: Well, it’s 150 years past the Civil War, so it’s about time, right?

DYKSTRA: Yeah. One of the things, Steve, we have plenty of in the south—and you’re beginning to see more of in the north—is kudzu, the fast-growing vine you see along roadsides and at the edges of forests everywhere in the south. Kudzu likes hot weather; we all know that. But as things warm up, kudzu is advancing north like the avenging ghost of Stonewall Jackson.

CURWOOD: So how far north has kudzu made it, and how much farther do scientists think it can spread, Peter?

DYKSTRA: It’s actually jumped the border; there’s an acre-large patch having jumped from Ohio, across Lake Erie, to Leamington, Ontario. It’s been reported in Nova Scotia, as well. It’s found in all five boroughs of New York City, but get this: Kudzu survives in areas of Korea where winter temperatures can reach well below zero. So get ready for it.

Japanese whale meat (Photo: JD; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, thanks, but no thanks, Peter. What about this week’s environmental history lesson?

DYKSTRA: Well, with all the human suffering and tragedy in World War II, it’s not really a surprise that this one got lost in history, and it actually happened on the one-year anniversary of Hiroshima. On August 6, 1946, General Douglas MacArthur, who was overseeing the occupation of Japan, authorized the creation of two factory-ship fleets for large-scale commercial whaling. The intention was to help re-build the Japanese economy, which was of course in shambles after the war.

CURWOOD: Which led to its own war on the biggest animals on the planet.

DYKSTRA: Yup. For the next several decades, Japan became the undisputed whaling king. But actually, there was a huge slaughter in the decade before World War II in the 1930s, but that postwar period and MacArthur’s order, intended to provide jobs in Japanese seaports, enabled one of the biggest wildlife disasters in the 20th century.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is the publisher of EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks so much, Peter. Talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve. Thanks a lot.

Related links:

- Read more about the kudzu in Bloomberg News.

- Read more about the Carmichael coalmine in the Brisbane Courier-Mail.

[MUSIC: Michael Bloomfield: “Albert’s Shuffle” from From His Head To His Heart To His Hands (Columbia Legacy 2014)]

CURWOOD: Maybe what’s for dinner should be fish, but there are problems there as well. That's ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Michael Bloomfield: “Albert’s Shuffle” from From His Head To His Heart To His Hands (Columbia Legacy 2014)]

American Catch

Shrimpers use fine-meshed nets, which can trap large amounts of bycatch. (Photo: Billy Metcalf Photography; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Something strange is going on in the U.S. seafood industry. Paul Greenberg, seafood expert and enthusiast, says Americans are eating less and less from their own oceans, and more imported fish. His new book, American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood dives into the contradictions behind the industry and explains what can be done to restore America’s catch to American mouths. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Paul.

GREENBURG: Hey, thanks, Steve. Great to be back.

CURWOOD: Both Four Fish and American Catch, your latest book, explored the seafood industry. What sparked your interest in the subject?

GREENBURG: Well, originally I grew up in coastal Connecticut, and I actually got a boat when I was a really little kid back in the day—you know, something that you would never dream of doing with a young child. My dad would take me fishing on the weekends we would spend with him, and I think he took me fishing, not because he knew how to fish, because he didn't. He took me fishing because he kind of had this thought that that's what dads should do with their kids. So I kind of taught him, as he taught me when it came to fishing.

CURWOOD: Maybe that's why he went fishing with you.

GREENBURG: I think so. It was a real bonding experience. It was really about exploring something together.

Alaska sockeye salmon. (Photo: Chris Pike; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now this latest book uncovers—well, I think it’s a contradiction, really—it’s a rather strange contradiction in America's food industry. What's going on?

GREENBURG: The United States owns more ocean, or controls more ocean than any country on Earth, 2.8 billion acres, but yet more than 85 percent of our seafood is imported. That's really strange, but it's even stranger, because we're also exporting a third of what we catch, like three billion pounds a year. So it just made me feel like the whole thing was a little out of whack.

CURWOOD: Well this seems counterintuitive: I mean, why export so much fish?

GREENBURG: Right, why export so much fish when you seem to have some kind of deficit? Well the answer is: What we're kind of doing is low-grading our seafood supply. We are getting top-dollar for our very well-managed, wild American seafood, a lot of which goes to Asia, and in the other direction, you know, one fisherman said to me, “Americans just really aren’t hip to fish.” And as result, they're willing to pay bottom-dollar for things like tilapia or shrimp, because they’re not so interested in flavor, they're really just interested in a neutral piece of meat that they can put on a bun or deep-fry.

CURWOOD: In your book, you point to the huge export that we do of Sockeye salmon, the run that's up in Alaska and Bristol Bay. Talk to me about Bristol Bay Sockeye salmon.

GREENBURG: Bristol Bay is home to the largest Sockeye salmon run remaining in the world, and Sockeye salmon are really delicious, very nutritious fish. But what makes this area particularly worthy of an investigation is that, not only is it the site of one of the great last salmon runs on Earth, it's also the site of a proposed mine that would involve the digging out of about 10 billion tons of earth and ore that would be processed on-site, which is not a great thing for those kinds of fish. They really need pristine environments, and so having this threat of the super-large mine next to this super-large sockeye run is a problem.

Paul Greenberg (left) fished for sockeye salmon in Alaska’s Bristol Bay. (Photo: courtesy of Paul Greenberg)

CURWOOD: Now, I gather that the Pebble Mine proposal is kind of on hold at this point. A lot of the backers have pulled out.

GREENBURG: Yes, one of the major partners in the Pebble partnership, Anglo-American, did pull out earlier last year, and the U.S. EPA has also started what's called a 404(c) action under the Clean Water Act, which would enable them to very severely restrict the kinds of industrial development that could happen in the bay. But it’s still a work in progress, and it's possible that a new administration could look the other way on all of this.

CURWOOD: What are the risks remaining for Sockeye salmon, and why don’t we get them in the lower 48 states?

GREENBURG: We do get them here in the United States, in the lower 48, though a lot of them are exported. Eighty percent of the Alaska salmon harvest is exported to other countries, and then of course there’s this weird wrinkle—that a portion of the Alaskan salmon harvest we catch at sea; we freeze it. We send it to China; it’s defrosted, filleted, boned, refrozen and then sent back to us twice frozen.

CURWOOD: Huh?

GREENBURG: Yeah, it's bizarre. The other day, actually, in Berkeley, I was having a coffee with Michael Pollan, you know, he's kind of like this turf to my surf, I suppose, and I said, “Michael, why is it that everybody is so obsessed with this story about the fish that we double freeze and send to China?” And very wisely, he said, “Well, it is a symptom of something much bigger which you’ve put your finger on, which is that there's something really weird with the seafood system.”

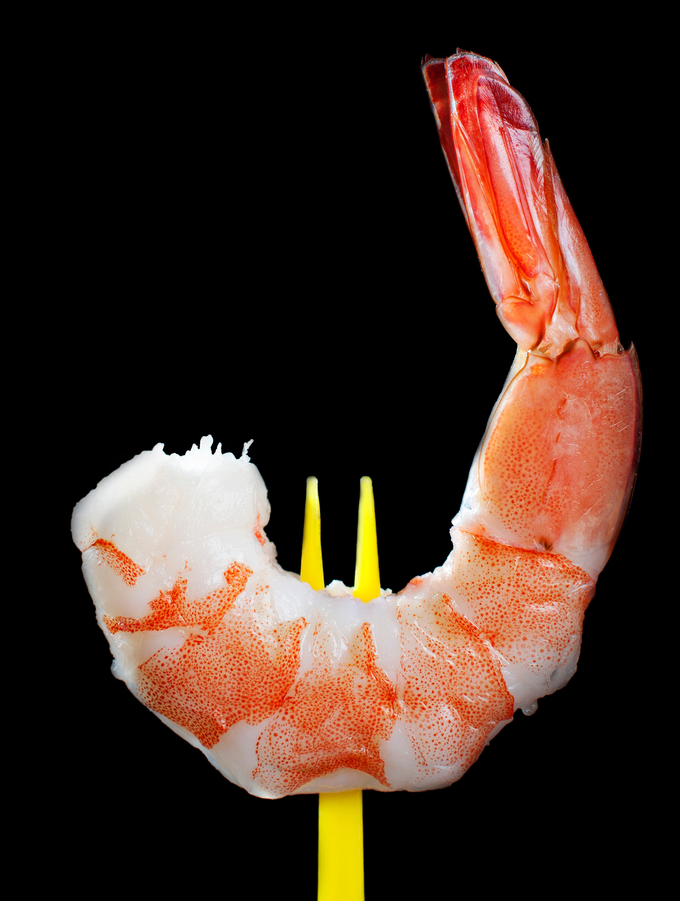

CURWOOD: In your book, American Catch, you highlight New York oysters, the Sockeye salmon from Alaska and Louisiana brown shrimp. And I want you talk about the shrimp because I was so surprised to learn that this is the most popular seafood here in the United States.

Shrimp has become America’s most popular seafood. (Photo: BillyBy; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

GREENBURG: Yes, shrimp, in general, we just go gaga for. We eat almost more than the next two most popular seafoods combined: that would be salmon and tuna.

CURWOOD: So why are we so obsessed with shrimp?

GREENBURG: It's the seafood that's the least like fish. Americans have gotten used to the mouth feel of meat and shrimp flesh is the way it is because it's kind of the precursor cells to the hard-shell, so they're harder and more resistant to tooth pressure, then say a flaky fillet of fish, but it also, and in its farmed form, it's not particularly flavorful. And you would think, “Oh, this would make it bad for consumers. They want something with flavor,” but it turns out that Americans actually don't really want a lot of flavor. They like kind of flavor-neutral things that they can deep-fry and put a lot of sauce on.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the shrimp we import. Where do they come from?

GREENBURG: About half of the shrimp that we import is wild, and about half of it is farmed. And a lot of it is farmed in Asia. The first shrimp to be to domesticated was way back in the ’40s and ’50s. There was a scientist named Dr. Fujinaga from Japan, and he domesticated a kind of shrimp called the Kuruma Prawn. This was a creature that they used in a dish called “dancing shrimp”—and it was a shrimp that you peeled the carapace off while it was still alive, dipped it in sake and popped it in your mouth and let wriggle around in there. And that was that was its last dance so to speak.

CURWOOD: Oh, my.

GREENBURG: Yeah, but it was very popular amongst the Japanese aristocracy, and it was very expensive; it was the equivalent of about $100 dollars a pound. Now, Fujinaga, he didn't want to just grow shrimp for lots of rich people; he actually had this vision that shrimp could feed a lot of poor people. And the same time, he realized he should start with a high-value creature like the Kuruma and then expand outward from there. He had a lot of foreign graduate students. And they fanned out over many countries, and they started this sort of domestication wave where they domesticated several different species. And now probably 85 to 90 percent of the shrimp that we eat are one of two species. Most of it is White Lake Pacific Shrimp the other is a Tiger Prawn.

Oysters, once ubiquitous in New York Harbor, can now scarcely be found. (Photo: Farrukh; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Talk to me a bit about American shrimp. What about the Florida pink shrimp?

GREENBURG: That’s a pretty good tasting shrimp. I haven't done a huge amount of research into it, but I’ve certainly eaten it. And then, also in addition to Louisiana brown shrimp, there's a white shrimp that's caught in the gulf. And then we have the Pacific Spot prawn out in the west coast; there’s Oregon pink shrimp, which is quite good. There’re actually over 2,000 species of shrimp in the world. It’s just to sort of fate and choice that we’ve ended up eating mostly just two from the farm.

CURWOOD: Now, what's going on with the shrimp market in Louisiana?

GREENBURG: When I first started to write American Catch, the Deepwater Horizon BP spill had just happened. What I found when I talked to shrimpers and people down there was that, “Yeah, the oil spill was a disaster”. It was crazy, but what was really on their minds was the way that foreign shrimp was severely, severely depressing the price of their wild product.

CURWOOD: How does Louisiana shrimp taste compared to the stuff that gets sent from overseas?

GREENBURG: I think that Louisiana shrimp, well, particularly the brown shrimp that I had, have a distinct taste. Some people find it a little bit iodine-y. It's a little briny. It's just a broader spectrum of flavors. Somebody was asking me the other day to compare, say, wild Sockeye to farmed Atlantic salmon. The best I can come up with is that the melody was the same, but there were more notes—there is just more accents and highs and lows, and that's true of wild shrimp in comparison to farmed shrimp.

CURWOOD: A while back, Paul, we talked to you about the prospect of using oyster reefs to protect New York harbor. What happened to the oysters in New York to began with?

GREENBURG: New York used to have literally trillions and trillions of oysters. A single oyster can filter about 50 gallons of water a day, so you had the situation where you had this amazing living breakwaters that would turn over the entire water column of New York City regularly every few weeks or so. What first happened is that we ate them. The Dutch settlers, and then the English after them loved, loved, loved the oysters, and instead of throwing shells back in the water, we kept the shells in shore: ground them down, burned them down for lime, and basically mined out the ecological infrastructure of the harbor. After that, there was a very long period where there was an oyster farming industry, but then once we started dumping something like six million gallons of sewage a day into the water, that pretty much put an end to the oyster farming industry by the 1920s. So there are still some wild oysters left in the harbor, but they’re a fraction of their former selves, that is up until the last few years, which is kind of the story of the first chapter of the book.

CURWOOD: Well, when I was coming up as a kid, I was told to be very careful of oysters if you ate them, you know you could get very sick or you might even die.

GREENBURG: My father's generation grew up with a real fear of shellfish, and I remember my dad telling me when he was a medical resident at Bellevue one of the worst things that could happen would be somebody came in with oyster shellfish poisoning. But since the Clean Water Act came along in 1972, our waters have really gotten progressively cleaner and cleaner to the point where there's now enough dissolved oxygen in New York harbor to support oyster life and in the course of my research, I did find several places where oysters were growing again. But it'll be many, many years, if not forever, until you can eat a New York City oyster again.

Oyster specials are again becoming commonplace. (Photo: Thomas Hawk; Flickr Creative Commons 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hey, Paul, I noticed over the past couple years you walk into almost any restaurant that thinks that it’s got some kind of snap, there will be a buck an oyster.

GREENBURG: I know, isn’t it great?

CURWOOD: Yeah.

GREENBURG: Do you eat oysters again now?

CURWOOD: Well, I certainly started eating them at a buck apiece.

GREENBURG: [LAUGHS] Right, what have you got to lose? It used to be, they would have amazing specials in New York, like there was this thing called the Canal Street plan where you could get all the oysters you could eat for sixpence and they were so big I think it was Swift, who said something like, that eating an American oyster was like eating a baby. But, of course in my childhood, oysters got really expensive, and you could see $3, $4, $5 dollar apiece oysters. In the last few years producers are finding there is both an appetite for oysters again, and there's also the good water for oysters again. We’re still not there—we’re only 14 percent of the circle capacity of oysters, but I think we could get to 100. And I personally would like to see a 25-cent oyster special sometime.

CURWOOD: So exactly how big were those oysters that Jonathan Swift the writer was talking about?

GREENBURG: Well they said it was big as a dinner plate. Most of the oysters that you and I eat in oyster bar are going to be like three years old, but what Swift was eating was oysters that would've been eight, 10, 15, 20 years old. Those are really, really old granddaddy oysters we just don't see anymore.

CURWOOD: What do you think is the most innovative idea that you came across in your research to fix some of the problems we had with our seafood?

GREENBURG: Well, I quite liked the work of Kate Orff and her idea called oyster-tecture, which was using breakwaters constructed out of oysters that would grow and create habitat as they created storm protection. The presence of an oyster reef has been found to potentially double the seafood carrying capacity of the near-shore. You know, other opportunities out there are things like, in order to relocalize the seafood that we do have, there’s a whole bunch of these things called community supported fisheries starting to arise. CSFs, they’re abbreviated, and what CSFs do is it's an opportunity for you to buy a share in a local fishery at the beginning of the season directly from the fisherman, so there are no middlemen involved, and then you get a delivery or you have a pickup scheduled of fish throughout fishing season, so it’s sort of a win-win. You get fish that you know where they're coming from; your fisherman gets money at the beginning of the season that supports the work that he's doing when he doesn't have cash on hand to start his business normally.

Paul Greenberg is the author of American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood.

(Photo: courtesy of Paul Greenberg)

CURWOOD: Despite all the challenges you outline, your book really has this ring of optimism about it. So what’s your hope for the future of American seafood?

GREENBURG: American fisheries have been improving. Since the 1996 Sustainable Fisheries Act, we actually have seen the rebuilding of over 30 different stocks of fish. And I think we can positively continue in that direction. The next big things that we’re going to have to confront are infrastructure issues like, for example, restoring salt marsh—70 percent of which we’ve lost—restoring oyster reef—80 percent of which we’ve lost. But I think these are things we can do if we decide that seafood should be a larger part of the American dietary portfolio.

CURWOOD: Why restore salt marsh, aside from restoring fisheries? What other benefits might there be?

GREENBURG: Having marsh around cities, towns, is a really good way to start doing some natural storm protection. Salt marsh can absorb up to a foot of storm surge, and salt marshes are the best at sequestering carbon of any ecosystem on the planet. They sequester more carbon than an Amazon rainforest. So it’s kind of incredible actually—A: that we’ve destroyed so much and that, B: we’re so slow to realize what a key thing salt marsh restoration would do for our climate, for our seafood supply, and for our general environment.

CURWOOD: Now, what’s your advice for concerned consumers who would like to support sustainable American seafood?

GREENBURG: If possible, always try to ask if your seafood is American. Secondly, try to get yourself familiar with the kinds of fish you should find in American markets: sockeye salmon is an excellent example, the same thing with oysters, and I think lowering our shrimp consumption a little bit. From a farming perspective, shrimp stress the environment because you need to dig all these shrimp ponds in your coastal areas that cause the destruction of mangrove forests and they cause the erosion of coastal ecosystems. On a wild perspective, shrimp, because they’re, well, shrimpy, you need to use a very fine mesh net to seine them up and you’re likely to catch a lot of accidental fish and other creatures, which is collectively called bycatch. I’m not saying give up shrimp entirely, but, you know, you might even think about eating the bycatch, and there’s actually an operation out of Louisiana called Total Catch. You can purchase the bycatch that is caught by a shrimp vessel.

CURWOOD: What’s your next adventure, Paul?

GREENBURG: My next adventure is something I’m calling the “Omega principle.” I want to track the omega-3 fatty acid around the world, looking at both sort of how the supplement could change our bodies, but also how coming to an understanding of things like algae and phytoplankton could change the way we’re dealing with climate change.

CURWOOD: Really?

GREENBURG: Yes. To be continued.

CURWOOD: Alright. Stay tuned. Paul Greenberg’s latest book is called, American Catch: The Fight for Our Local Seafood. Paul, thanks so much for taking the time today.

GREENBURG: Thank you so much, Steve.

Related link:

Learn more about the author of American Catch, Paul Greenberg, on his website

[MUSIC: John Zorn “The Sicilian Clan” from Naked City (Elektra Records 1990)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, James Curwood, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, Abi Nighthill, Jennifer Marquis and Olivia Powers all help to make our show. We also had help this week from Rosa Curson-Smith. Jeff Turton is our technical director. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org, and like us on our Facebook page—it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth