November 21, 2014

Air Date: November 21, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Keystone XL and the Price of Oil

View the page for this story

Senate proponents of the Keystone XL pipeline expect to try again to force the President’s hand regarding the controversial project when Republicans take over the Senate next year. But in conversation with host Steve Curwood, energy investment strategist Joseph Stanislaw says uncertainties about the pipeline’s economic feasibility, and its climate and other environmental impacts make its future uncertain. (05:55)

The Missing Campus Climate Debate

View the page for this story

Students and faculty from universities across the US have called for endowment divestment from holdings in fossil fuel; mostly to no avail. Legal scholar and commentator Evan Mandery tells host Steve Curwood about the disconnect between trustees and university communities, and the ethics of divestment refusal in the face of climate science. (06:10)

A ‘Charming’ New Particle

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Scientists analyzing data from the Large Hadron Collider have discovered several new particles, including a couple of what are called mesons. Professor Tim Gershon of the UK’s University of Warwick, the lead author of a paper that describes this discovery, told Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer that it could help explain one of the basic forces of the universe.( (07:40)

Modern Gleaning Helps the Hungry

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Gleaning is an ancient tradition. In the Torah and Old Testament farmers are instructed to leave some food in their fields for the poor to collect. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports that modern volunteer gleaners go to farmers’ fields at the end of the season to harvest the last of the bounty and then deliver the produce to food pantries for the food insecure. (10:10)

Plains Bison

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

In Saskatchewan’s Grasslands National Park, writer Mark Seth Lender encounters a bison herd. Though there are now so few of the millions of bison that once grazed the plains, Lender is still impressed by their size, power and indifference to his presence. (03:20)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood how Ohio’s report on “green” energy jobs disappeared, about the expensive divorce settlement of an oil magnate, and the anniversary of scientists’ email hacking known as “Climate-Gate.” (04:30)

Foods for Health

View the page for this story

Food has the power to heal and sustain, providing nutrients for our bodies and when we enjoy them with friends and family it feeds the soul. With this in mind, celebrity chef Barton Seaver co-wrote a new book called “Foods for Health”. He tells host Steve Curwood how we can eat well, sustainably and mindfully. (09:35)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Joe Stanislaw, Evan Mandery, Tim Gershon, Barton Seaver

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Mark Seth Lender, Peter Dykstra, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Students and faculty call on colleges to divest endowments from fossil fuel stocks, but most trustees and administrators resist the demands.

MANDERY: Trustees are disproportionately coming from financial industries. You're getting a lot of investment bankers, a lot of consultants, and I think there's an emotional component to this. I think it feels like a repudiation of what the trustees have done with their lives.

CURWOOD: The climate of disconnect between faculty and campus bosses. Also, a trip to a community farm to help glean the last of the fall harvest to give to hungry people.

NAVARRO: I love the gleaners. They come and bring fresh vegetables from their garden, and I give them out here in the pantry to the community and everybody loves it. It’s real food from Mother Earth, from loving hands that planted it, and it’s going to fall real good in the stomach. [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable, place to live.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Keystone XL and the Price of Oil

Truck hauling 36-inch pipe to build Keystone-Cushing pipeline (phase 2) southeast of Peabody, Kansas. The Keystone-Cushing pipeline phase connected the Keystone pipeline (phase 1) in Steele City, Nebraska south through Kansas to the oil hub and tank farm in Cushing, Oklahoma, a distance of 291 miles. Phase 2 completed February 2011. (Photo: Steve Meirowsky; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The Keystone XL pipeline has now been ‘in the pipeline’ for six years, and though Democrats in the Senate recently blocked a Congressional move to force the hand of President Obama, it may still get the green light.

Republicans say they’ll try again after they take control of both sides of Congress in January. For the Canadian producers of the highly polluting tar sands oil, speed is essential, as the world price of oil has dropped sharply, squeezing profitability and scaring investors. Keystone XL’s fast path to the Gulf coast refineries would get tar sands oil to market cheaper and make increased production more attractive. For insight, we turn to energy investment strategist Joe Stanislaw. Joe, welcome back to Living on Earth.

STANISLAW: Thank you for having me, Steve.

CURWOOD: Considering the prospects for the price of oil, how crucial is Keystone to making it economically viable to use tar sands oil?

STANISLAW: Does it make a difference right now in the short-term? Probably not a whole lot at all. [LAUGHS] Let's be realistic. So far, that oil has not been moving through those pipelines. It's been going east and west through other already existing pipelines. Now, there are other pipelines being built in Canada, one going east, one going west, to the tune of about 2 million barrels a day of oil equivalent flow. So that oil is going to be produced, it's going to be moved. That's a fact. When it is actually produced and moved, there's an issue of pricing and timing, but it's going to happen over the next five or 10 years. If it is delayed 20 years, if there are enough objections to it on the environmental front, they may pull back on that. But with the current situation and potential alternative routes for exporting, in the next five or ten years, it'll happen.

The Democratic-led US Senate defeated XL Pipeline measure, 59-41, on the night of December 14th, but the new Republican majority is expected to try again next year. (Photo: US Congress)

CURWOOD: Now, Joe, I know you're familiar with the argument of this put forth by some that to protect the climate two-thirds at least of present oil and carbon-based fuel reserves need to stay in the ground. How do you reconcile additional infrastructure like Keystone against those kind of concerns?

STANISLAW: In the short-term, we're not going to get off the stuff as they say, and oil will move. There will be that transition period taking place, and it'll begin to slow everything in the mid-20s probably, but equally I think more and more people will recognize that it used to be the fear of peak oil supply. That's now something that's been discredited. The real issue is, people can find new ways not to use the stuff. People will be using it much more efficiently, alternative sources will be found. Peak oil demand is really...should be the factor people are looking at.

CURWOOD: Joe Stanislaw, you're saying that really only in another decade, are we going to be looking for more and more oil. How much sense does it make to install large infrastructure like a Keystone XL pipeline if it's really going to be around for say, a decade or so?

STANISLAW: There will still be a lot of oil being used after a decade from now. These pipelines will last a lot longer without question, but if you can make a good return in 10 years, you're feeling pretty comfortable.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you see a Keystone XL as, well, frankly more of a political lightning rod than something that the oil industry absolutely has to have to operate effectively?

STANISLAW: I would say it is a very political issue, and to use some words that you used before, it's almost a lightning rod. It captures all those features from an environmental point of view that ignites everyone's passions, concerns. It's oil that's moving across national boundaries, it's oil that has a potentially higher environmental footprint and CO2 footprint than other oils, and also it focuses attention on something that does have a very large long-term potential because it is the largest oil resource base in the world, and that maybe now’s the time to try to stop it in its tracks, if one can, to stop it from realizing its long-term potential. So that focuses attention.

CURWOOD: Well, and, of course, this expansion, you talk about economic costs eventually coming down, but the environmental costs for these sources seem to be going up. You go to sensitive areas like tar sands, you go into deep, deep, in the Gulf of Mexico and we saw what happened there, the risks in the Arctic people are very concerned about, and there's a lot of head scratching about what would happen in Brazil if that deep, deep, deep drilling ever took place.

Joseph Stanislaw is a financial adviser on international markets and politics. He is also the co-founder and former president of Cambridge Energy Research Associates, an energy research consultancy that was acquired in 2004 by IHS Energy. (Photo: Courtesy of Joseph Stanislaw)

STANISLAW: I think you raise the right point, Steve. One of the key costs in production is the environmental cost. I will say though, Steve, it is fairly interesting if you look at the environment cost that people identify as "you must meet these"; CO2 is a challenge that has not been met yet, but on most others the costs are high, but over time even those environmental costs come down. With the learning curve, the improvement in technology, how it invigorates new research and development to create technologies at lower cost that can make those environmental costs.

CURWOOD: How long can the oil industry afford to wait on the moving forward with Keystone XL. It's been, what, six years? In other words, how hard are they going to push for action when the new Republican dominated Congress arrives in January to force President Obama's hands to approve this thing?

STANISLAW: The longer it takes to realize investments that you start, the less likely you're going to have any reasonable return on investment, and each additional month at this point, and every six months, you're impacting the economic potential of this project. So Keystone's been going on for a few years, it's been going on for a long, long time. When does the company give up? I just don't know the answer to that.

CURWOOD: Joe Stanislaw is an expert on energy and technology investment strategy and the founder of the JA Stanislaw group. Joe, thank you for taking the time to speak with me today.

STANISLAW: Steve, it's been a pleasure. Thank you very much for the challenge.

Related links:

- TransCanada’s Keystone XL project website

- Harvard Prof. Michael B. McElroy’s analysis in favor of Keystone XL

- The Natural Resources Defense Council’s analysis in opposition to Keystone KL

- About Joe Stanislaw

- LOE’s past coverage of the Keystone XL project

- Joe Stanislaw’s commentary about energy’s role in the Crimean conflict, our story

The Missing Campus Climate Debate

Students and faculty from over 500 universities globally are pushing their administrations and trustees to divest endowments from holdings in fossil fuel companies. So far, only a handful have committed to divestment. (Photo: James Ennis; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Students at Harvard Law School have sued the Harvard University Corporation for failing to divest its endowment from fossil fuels. The complaint charges “mismanagment of charitable funds” and “intentional investment in abnormally dangerous activities” and was filed in state court on behalf of seven students and “future generations.” This comes on the heels of hundreds of Boston-area college faculty calling on their schools to divest. City University of New York law professor Evan Mandery is a graduate of Harvard Law who has written about the resistance of Harvard President Drew Gilpin Faust and hundreds of other college trustees to divestment. Evan Mandery joins us. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MANDERY: Hi. Thanks very much for having me.

CURWOOD: So why aren't more schools doing what many other students are demanding, that is get rid of investments that promote the heavy carbon footprint?

MANDERY: Well, it's tough to answer, right, because university presidents are academics, and academics are overwhelmingly liberals, they're not climate change skeptics so it's hard to figure that out. I have guesses, but they're only guesses.

CURWOOD: Well let's talk about some of the guesses that you've written about. You point out that some university presidents say that endowments exist to support academic missions, such as scholarships and shouldn't be used as ammunition in a struggle for social change.

MANDERY: Right. I think it's pretext. I don't think they actually believe that. Many universities ultimately divested from South Africa, approximately 150 did. Many other universities have divested from tobacco companies, Harvard divested from Chinese companies that did business in the Sudan, so I don't think that that absolute principle is really something they believe, it's just something that they say.

CURWOOD: So if they don't believe it, why do they say it?

MANDERY: I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that it's trustees that are making the decision as opposed to it being a university communitywide decision.

CURWOOD: And why would trustees be opposed to divestment?

MANDERY: The trustees aren't exactly a representative cross-section of the university. Trustees are disproportionately coming from financial industries. You're getting a lot of investment bankers, a lot of consultants, and I think there is an emotional component to this, I think it feels like a repudiation of what the trustees have done with their lives.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, some of the most important research on effects of fossil fuel emissions comes out of universities, places like Harvard, Yale. Why are these institutions opposed to growing their endowment in every way possible that supports not just the finance of that research, but what the research results tell us?

Many Michigan State University students marched on May 2nd, 2013, Divestment Day of Action. (Photo: 350.org; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

MANDERY: First of all, you're made an important point, which is, this isn't what professors are saying. Trustees are just an insulated minority that are making this group independent of students and faculty. I think there are almost 500 university movements to divest, so there’s really a gross disconnect between what these boards of trustees are saying and what the actual university communities are saying.

CURWOOD: Now, let's go back to one part of the money. How much would divestment actually cost?

MANDERY: Listen, there's no simple answer to that question. According to some research, which is actually done by a petroleum think-tank, approximately two percent of endowment assets are invested in fossil fuel related companies. By their estimates, they slightly outperformed other endowment investments during the past 10 years. By some other estimates actually, they slightly underperformed. But either way you're talking about pennies if they rid the endowment of these assets.

CURWOOD: One of the arguments for not divesting is that schools keep a seat at the table in these companies by the power to file or co-sponsor or certainly vote on shareholder resolutions. What do you think of that position?

MANDERY: Right, well that evokes to me President Reagan's position during the 1980s in favor of constructive engagement, it was his argument against American divestment from South Africa. So it would be interesting if some universities were very heavily invested in fossil fuels and actively voting their shares to make those companies more responsible to, say, encourage them to report on climate change or include environmentalists on their corporate boards, but none of the universities are actually doing that, so I don't actually understand why the argument is being raised.

CURWOOD: I wonder if at the end of the day, Evan, you see divestment by universities as an ethical issue?

MANDERY: I see it at the beginning as an ethical issue. I'm an alum of the College. I read the president's letter in which she says that the school has no ethical obligation, that it should maximize its return on endowment resources and use those to support the academic mission, it's not, in President Faust’s words, "it's not an instrument to propel social change", and I'm just shocked by that. We can all easily envision investments that universities can make that no one would tolerate, so if Harvard had money invested in a company that profited by using child labor, there isn't a single person who would think that that was defensible because Harvard was generating a greater return on its endowment or using that money to support financial aid. So it's striking to think that universities wouldn't have any ethical obligation in this context, but the idea that it's not even an issue on the table is extraordinary to me.

Evan Mandery is Professor & Chairperson of the Department of Criminal Justice, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York. (Photo: Courtesy of Evan Mandery)

CURWOOD: What kind of traction do you see the divestment movement gaining?

MANDERY: Of course universities are going to divest! One thread of the negative responses to my argument is from climate change deniers, but that's not what's going on with universities. I don't believe - I've never met President Faust or or any of the other university presidents - I don't believe a single one of them doubts the science on climate change, and many of them in their letters refusing to divest say that they accept the science behind climate change and view it as ethically problematic, they just don't see divestment as a way to address it. But, man, oh man, they so grossly underestimate the symbolic importance that universities play in setting tones for moral debate. The question is whether they'll divest at a point where it'll actually lead to some good happening more quickly than it otherwise would have, or whether it'll just be a purely symbolic statement just because it would be a public relations nightmare if they fail to do so, which by the way is basically how the South African divestment story ended. Maybe if this were 20 years ago and we were still debating the science you can imagine universities being reserved in their approach. There's no such justification now.

CURWOOD: Evan Mandery is a Law Professor at the City University of New York. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANDERY: Thanks so much for having me. I enjoyed it very much.

Related links:

- Evan Mandery’s “The Missing Campus Climate Debate” essay in the New York Times

- More on the debate for endowment divestment on university campuses

- Harvard Students Take Fossil Fuel Divestment Fight to Court

- Cost of divestment on American College and University Endowments, American Petroleum Institute December 2012 report

- American Petroleum Institute October 2014 report: “Who Owns America’s Oil and Natural Gas Companies”

- Harvard President Faust’s letter on divestment

- University and College commitments to fossil fuel divestment

- More about Professor Evan Mandery at John Jay College of Criminal Justice

[MUSIC: Silversun Pickups from “Checkered Floor” from Carnavas]

CURWOOD: Coming up...How some of the tiniest things could help explain the universe. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis from “Flamenco Sketches” from Kind Of Blue (Columbia 1959)]

A ‘Charming’ New Particle

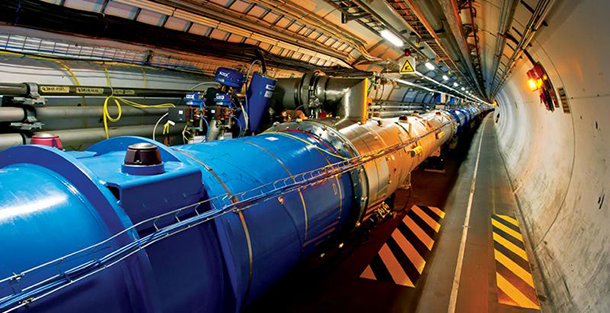

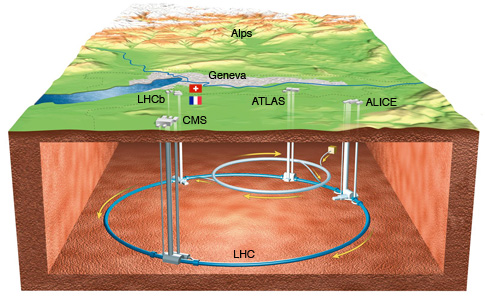

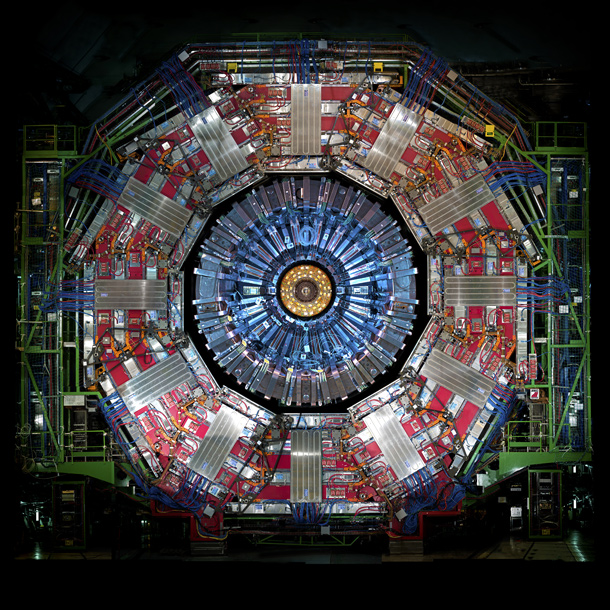

The Large Hadron Collider accelerates beams of protons or ions close to the speed of light in order to produce high-energy collisions. These collisions produce some stable and some unstable particles, which can be seen in the data collected. (Photo: CERN)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Now, we don’t often report on particle physics, but there’s a lot of news in this cosmic field. Recently, the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva found evidence of the Higgs Boson, a subatomic particle predicted years ago to partly explain how energy can become mass. And now researchers using data from the collider have discovered more new particles. Two of them are called mesons, which seem to exist for the briefest of moments as tiny subatomic particles known as quarks come together to make bigger particles like protons and electrons. This finding helps explain a fundamental force of the universe. Tim Gershon of the University of Warwick in the UK is lead author of the study in Physical Review Letters. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

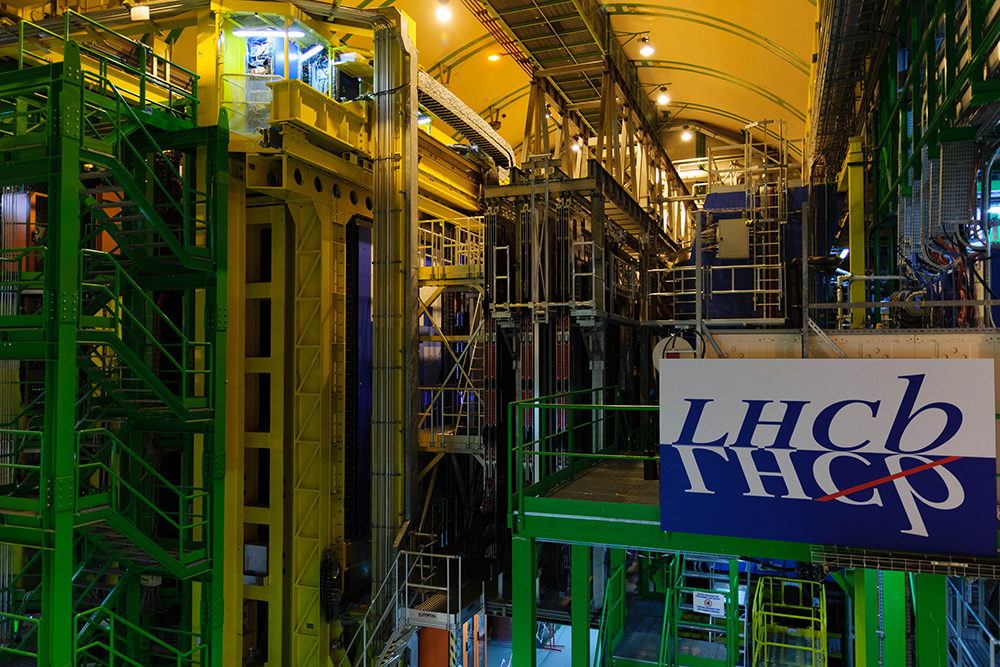

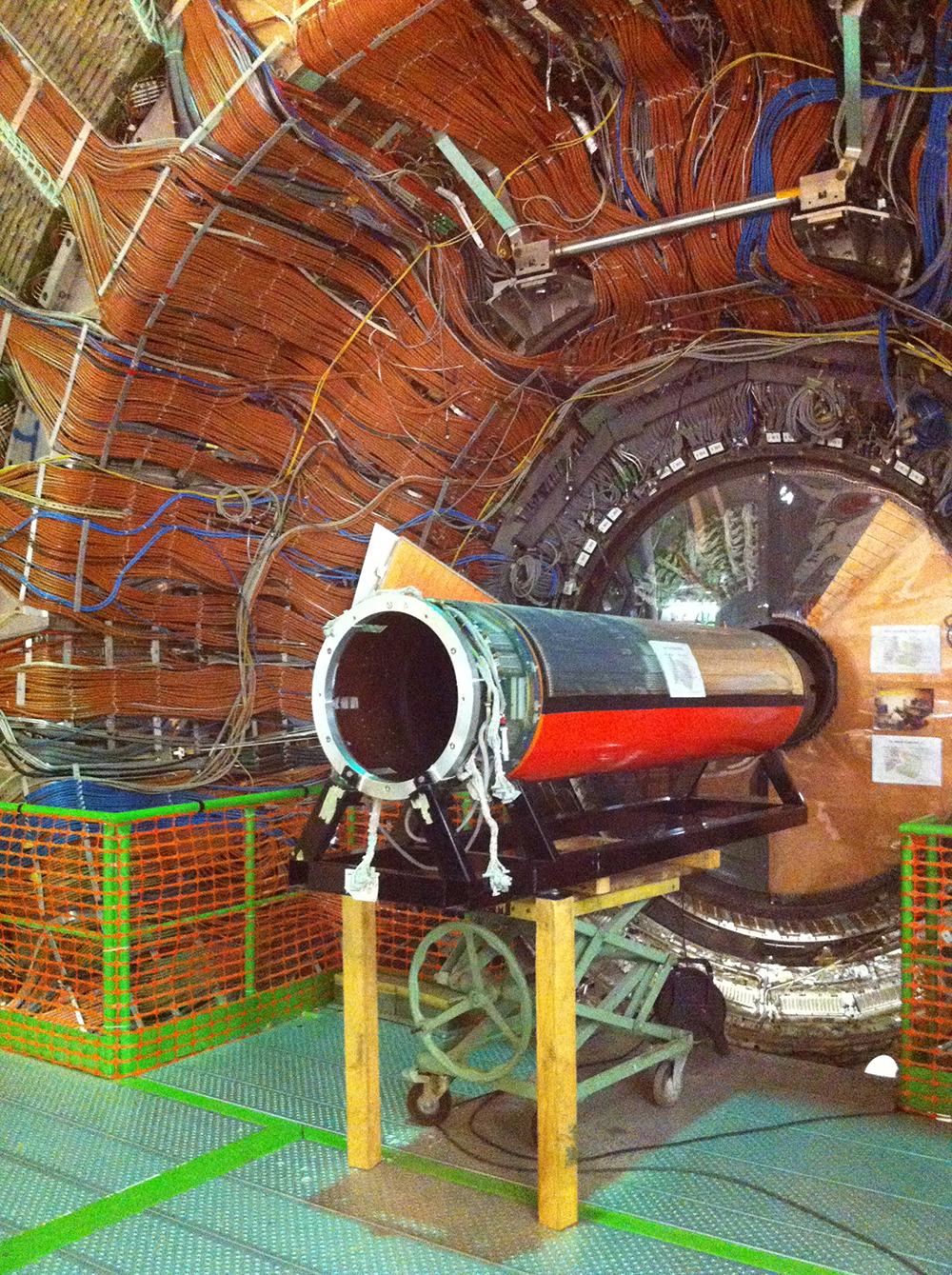

Hundreds of scientists collaborated to discover the new meson particles, analyzing data gathered from the LHCb detector at the Large Hadron Collider. (Photo: Radoslaw Orecki; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

PALMER: So can you describe for our listeners, in layman’s terms if you possibly can, what exactly have you found?

GERSHON: So we have discovered two new particles. These particles are of a class of particles called mesons, which means that they're composed of smaller particles which we call quarks. Quarks are among the fundamental articles of nature, you cannot divide a quark into anything smaller.

So let's imagine if we look at the world around us, and we can see a nice view, we can see trees, and trees, of course, are built of proteins that contain molecules and the molecules are made up of atoms and inside an atom is a nucleus at the center of it, surrounded by electrons. If we go closer still into the nucleus to find that is made up of protons and neutrons held together, but inside the protons and neutrons themselves we find quarks.

The Large Hadron Collider is buried 160 to 570 feet below the Franco-Swiss border, near Geneva, Switzerland. (Photo: CERN)

PALMER: So, basically you've gone as tiny as it is possible for anyone to go to look at what makes up our universe?

GERSHON: That's right. That’s right.

PALMER: So tell me about the quarks that are out there?

The LHCb detector records the decay of particles known as B mesons – b for ‘bottom’ (previously ‘beauty’), which is one of six types of quarks. (Photo: Jeremy Keith; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

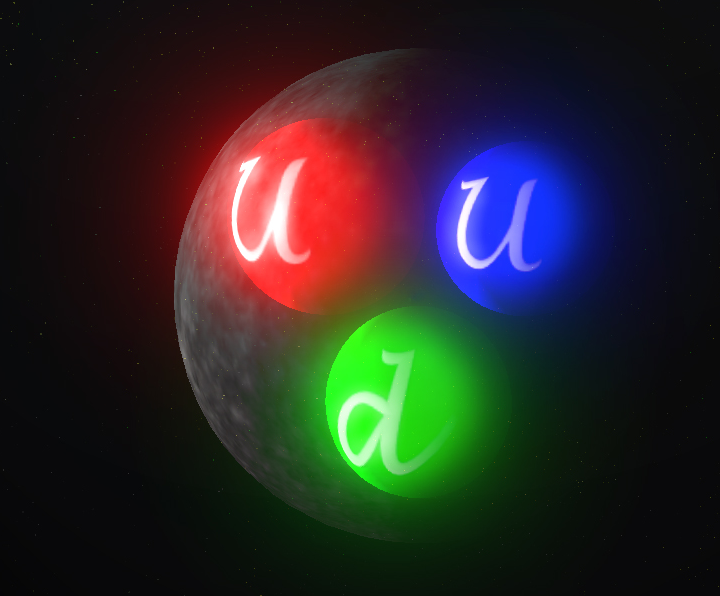

GERSHON: There are six types of quarks that we know about, and they are called up, down, strange, charm, top, and bottom. So the lightest ones are the up and the down, and those make up the protons and the neutrons. But the heavier ones can be produced in particle accelerators. These mesons do not exist as stable particles in nature, but can be produced in particle accelerators. The new particles that we've discovered contain a charm quark as well as another quark. They're mesons so they contain a quark and an anti-quark.

PALMER: So they're subatomic particles, but what exactly did you do to actually create these new particles not known before?

GERSHON: Well, we worked with data from the LHCB experiment at the CERN Large Hadron Collider. The Large Hadron Collider has received a lot of publicity for the discovery of the Higgs Boson. That experiment is called Atlas and CMS and quite rightly so, but there's also other experiments at the LHC and in particular the LHCB experiment is designed not to look for very heavy particles like the Higgs Boson but to understand the properties of lighter particles called B-hadrons. So the "B" here stands for bottom, which is as I mentioned, one of the six quarks. I should say that actually sometimes we call them beauty, which is perhaps a nicer name than bottom.

PALMER: Well, charm and beauty, I mean, come on. [LAUGHS]

The Large Hadron Collider, with a circumference of 17 miles, is the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator. The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) operates and maintains the collider near Geneva, Switzerland. (Photo: Image Editor; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

GERSHON: Indeed. Indeed. But then, Shakesphere had a Bottom, and I suppose he had some beauty as well. Anyway, the beauty quark decays to charm. So by studying the decays of beauty quarks we can see the production of charm quarks and we can study the different types of charm meson that can be produced. Now, the quarks are bound together by the strong interaction. The strong interaction is one of the four fundamental forces of nature, that we know. The others are gravity, the electromagnetic interaction, and the weak interaction. And as the name implies, the strong interaction is very, very strong. So when you get inside a proton or a neutron, if you are able to do so, the strong interaction is the only thing that matters. All the other forces are irrelevant at that scale.

PALMER: So the strong force or strong interaction is a really vital force of nature? I mean, you spoke about the four forces. These are the forces that basically hold everything together in our universe.

A proton is composed of three quarks: two “up” and one “down.” In contrast, the mesons recently discovered each contain one “charm” quark and an anti-quark. (Photo: J.Gabás Esteban; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

GERSHON: That's right. On the cosmological scale, let's say gravity is the most important force, and gravity holds together our planet, and our solar system, and galaxies and things on a large scale like that. When we look at the molecular scale then the electromagnetic interaction is the most important, and that's what keeps electrons orbiting around the nuclei in atoms, but as we go to a smaller scale, it is the strong interaction that is the most important and takes over.

PALMER: So what you have just discovered will help you understand the strong force, which is what holds these mesons together. The weak force holds what together?

GERSHON: The weak force doesn't hold things together. So, the strong interaction holds nuclei together, but the place where people would be most familiar with the weak force is that it's responsible for causing nuclear decays. The weak interaction also has a very crucial role for processes that are going on inside the sun, for example.

PALMER: I realize that you have just added to our knowledge about about particle physics by having discovered two new ones, and it seems a little sort of like, unkind, to say are you going to find more, but are you going to find more? Are you looking for more?

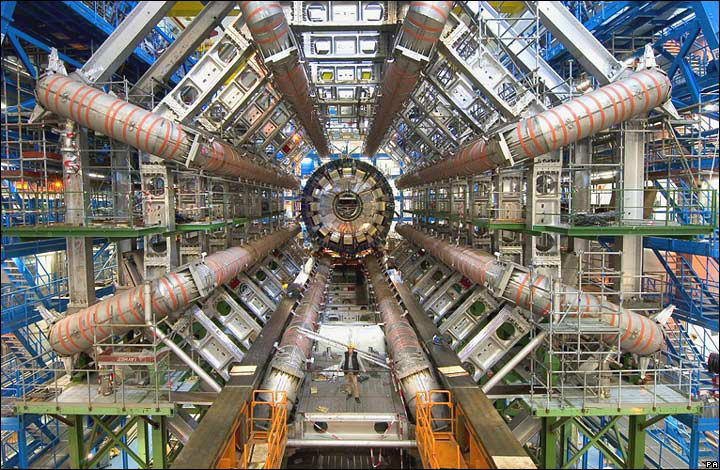

In July 2012, researchers at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN) announced that the Large Hadron Collider’s CMS detector, shown above, had observed the Higgs boson, marking the discovery of a new subatomic particle. (Photo: Phil Plait; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

GERSHON: The development that I'm really excited about is the possibility that we can use the same technique to try and study the weak interaction, and if so, this could be a great way to learn more about one of the greatest puzzles that we have, not only in particle physics, but in all of science: why the universe exists at all.

The universe is believed to have started in a big bang, essentially a ball of energy, and energy will always produce equal amounts of matter and antimatter. So at the start of the universe, there was an equal amount of matter and antimatter. But in the universe that we see around us today, we see only matter no matter how far out in space we look. And this is connected to a phenomenon that particle physicists call CP violation, but this is really just a jargon that means an asymmetry between matter and antimatter.

Dr. Tim Gershon is a professor of particle physics at the University of Warwick and studies B mesons and quarks. (Photo: Courtesy of Tim Gershon)

So we want to be able to study differences between the behavior of matter and antimatter in the laboratory, but we still haven't discovered enough different types of CP violation in order to be able to explain where the asymmetry in the universe comes from. And therefore, we're looking for for more sources, and what I'm very excited about is that we can perhaps use this technique that we've discovered these new particles with to perhaps learn more about this mystery of how the universe evolved.

PALMER: So something of some kind happened very early on that means that what we have is more matter than antimatter or we obviously wouldn't exist because if matter and antimatter basically wipe each other out, annihilate each other, then there would be no matter and there would be no stars and there would be no Earth and there would be no us.

GERSHON: That's exactly right, and what a bleak universe that would be.

CURWOOD: Tim Gershon is a Professor at the University of Warwick in the UK. He spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- The paper on the particle discovery, published in Physical Review Letters

- The Higgs Boson Explained (video)

- LHCb experiment observes two new baryon particles never seen before

Modern Gleaning Helps the Hungry

Gleaning volunteers pick lettuce at Waltham Fields Community Farm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Much of North America is now facing the cold, dark time of year. Close to Thanksgiving, farmers’ markets are piled high with squash for the celebration before they shut down. But that doesn’t always mean that farmer’s fields are empty - in fact, a lot of perfectly good cold-hardy food often remains. Now thanks to the age-old but newly popular custom of gleaning, some of the fresh food that would otherwise go to waste is getting to some people who need it most. Last year, Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb went to check out what the gleaners do. Her report starts in farm fields west of Boston.

CRAWFORD: Thanks for coming out today guys, we’re at Waltham Fields Community Farm. So we are going to harvest some lettuce and maybe some collard greens as well.

Gleaning coordinator, Matt Crawford, demonstrates the best way to harvest lettuce. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Matt Crawford welcomes a group of 5 volunteer in the parking lot of a small farm, 10 miles west of Boston. They’ve come to glean--to collect the last of this year’s greens to donate to a food pantry produce that would otherwise go to waste.

[SFX WALKING ON GRAVEL]

BASCOMB: Matt leads the gleaners out to the long furrowed fields. Most of them are empty now, rows of soil waiting for the spring planting. But 4 rows at the end are covered in a long white gauzy sheet.

[SFX FABRIC PULLING SOUND]

BASCOMB: Matt pulls back the fabric to reveal perfect heads of red and green leaf lettuce. In the summer they would easily fetch two or three dollars apiece at the farmer’s market.

CRAWFORD: I’m sure most of you have harvested lettuce before but I’ll show you the best way to do it. Carefully grab it, pull it back, tilt away from the ground, from the earth. Cut it right at the base so leave any roots in ground. And then you prune off any dirty or dead looking leaves, anything that’s yellow, and we’ll put it right in the bag.

BELL: There’s stuff besides lettuce, we’re just going for the lettuce?

CRAWFORD: Just the lettuce, yeah. All this other stuff is weeds, which are edible but we’re not going to eat them.

BASCOMB: Volunteer Bruce Bell gets to work at the top of the row, crouching down to cut the lettuce with a small sharp knife.

Waltham Fields Community Farm. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BELL: This is a beautiful one, a few dead leaves, some dirt but more or less a beautiful head of lettuce. I’m a gardener also and I wish I could do things as good as this! Come out here and admire everything else that’s so beautiful even at this late season. A few dead leaves here, throw them off, brush them off the dirt and in we go.

BASCOMB: (on tape) So, why do you do it? Why do you like coming out here?

BELL: I like the exercise, I like the fresh air. I like the connection it makes to other people that everyone should eat as well as I do and I think I eat pretty well and this is one way to help that along. You can see how much, I wouldn’t call it waste, but so much in the food chain that could go to waste if we weren’t doing this.

PORTER: I think farmers have big hearts and don’t want to see food go to waste.

BASCOMB: Zana Porter is one of the farmers at Waltham Fields Community Farm. Porter says by this time of year they no longer have a market for the produce left in the fields.

PORTER: At the end of the season we reach a point in the season where staff levels drop off we’ve met most of the demands of our CSA and if it’s been a good season we still have food in the field and that food needs to go somewhere. So we call on the gleaners to come and get the last of what’s in the field so it doesn’t go to waste.

BASCOMB: This community farm is run as a non-profit and giving back to the community is part of their mission. But Porter says there are also practical reasons for getting as much as possible out of the fields.

Gleaning Coordinator Matt Crawford and fellow gleaners remove lettuces and collard greens. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PORTER: Sometimes it’s really important to clean out your fields. It’s important to get anything that might carry disease through the winter out of your fields. There’s a lot of insects that over winter in certain crops. And if you leave that crop to rot there that pest can overwinter, it’s going to be there in the spring. I think there’s probably some motivation in that as well.

BASCOMB: Gleaning is an ancient tradition. It’s referred to in the Torah and the Bible. Leviticus chapter 19 instructs, “When you reap the harvest of your land, do not reap to the very edges of your field or gather the gleanings of your harvest. Do not go over your vineyard a second time or pick up the grapes that have fallen. Leave them for the poor and the alien.” Gleaning continued into the 19th century as a social safety net through much of Europe. Today there are gleaning organizations across much of Europe and the US. Duck Caldwell is Executive Director of the Boston Area Gleaners.

CALDWELL: This year we’re gonna recover over 70,000 pounds. That equals close to, when you convert it to 4 ounce servings 300,000 servings of fruit and vegetable.

BASCOMB: Caldwell says they pick at least 30 varieties of produce…all kinds of greens, eggplant, peaches, carrots, apples, turnips, squash… anything you might find in a farmer’s market can be gleaned when there’s a good harvest.

CALDWELL: We’re going to serve about 25 farms this year with our gleaning. There are well over 1000 in this area. So the potential is huge. We’re doing a good job meeting the demand we’re getting currently from farmers, but demand side where people actually need this food, there’s much more there so there’s a lot of work to be done.

Farmers often have many crops that aren’t aesthetically perfect and likely won’t fetch much at market, but are nutritionally worth harvesting. Gleaners help prevent food waste and get it into the hands of those that would appreciate it. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: After three hours of work the volunteers picked 576 pounds of lettuce. They pack the harvest into banana boxes and load them into a van for delivery. Roughly half of what’s gleaned goes to the non-profit, Food for Free, which distributes to 86 food banks from its headquarters in Cambridge. Sasha Purpura is the Executive Director.

PURPURA: Food for Free is an organization that essentially captures food that would otherwise go to waste, perfectly good healthy food, and then distributes it into the emergency food system where it can reach those in need.

BASCOMB: Food for Free staff makes daily rounds to local grocery stores to collect good food that would be thrown away at the end of the day but she says, what the gleaners supply is special.

PURPURA: By far the gleaners’ food is without question the absolute best food we can get. It's the freshest, it’s local. The people who are receiving it love fresh vegetables as much as anybody else does.

BASCOMB: Purpura says it is relatively rare for food pantries to have access to fresh, local produce.

Farmer Zana Porter (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PURPURA: A lot of food pantries can get food from food banks, but it’s typically shelf-stable canned stuff. It’s hard for small food pantries or other things to carry produce because they don’t have the storage for it. They need it on the day that the pantry is opening, it’s volunteer run. And because the gleaners and Food for Free can deliver day-of it allows them to offer more than canned sodium-enhanced stuff.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: In the basement of the Food for Free office is a food pantry serving Cambridge. Sasha leads the way and introduces me to Aida Navarro, the food pantry manager.

PURPURA: Hi Aida.

AIDA: Hi sweetheart. Are you the radio girl?

BASCOMB: I am. What gave it away? (laughs)

BASCOMB: Aida has a kind face and an affectionate manner.

NAVARRO: I love the gleaners. They come and bring fresh vegetables from their garden. And I give them out here in the pantry to the community and everybody loves it.

BASCOMB: (on tape) Why do you think they love it?

NAVARRO: Because it’s real food from Mother Earth. From loving hands that planted it and it’s going to fall real good in the stomach. (laughs)

BASCOMB: Freddy, the pantry’s food manager, stands amid boxes of produce and offers them to a small frail, elderly woman named Anne.

FREDDY: We have potatoes, onions, we have collard greens.

Volunteers collect 576 pounds of lettuce into plastic bags. (Bobby Bascomb)

ANNE: Greens?

FREDDY: You want collard greens?

ANNE: Yeah. And lettuce? You have lettuce?

FREDDY: We have a spring mix or we have this….

ANNE: Spring mix. Terrific!

FREDDY: Green pepper?

ANNE: Sure! It’s very good things.

BASCOMB: Do you like the fresh produce, ma’am?

ANNE: Absolutely, it’s the best.

BASCOMB: Why is that?

ANNE: Well, it’s very expensive. It’s something hard to get. So, I like it very much.

FREDDY: Eggplant?

ANNE: Sure

The Food for Free van delivers recovered food to food pantries across Cambridge. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: What kind of things do you typically get this time of year?

ANNE: Anything green. It’s beautiful. What they do is so important for us. I get things I couldn’t afford. I get a lot of greens. It fills in spots I would otherwise neglect. And it’s a little gift. So it makes people happy.

BASCOMB: Visitors to the food pantry are young and old. Black, white, Hispanic, Asian and everything in between. Aida greats a familiar face.

AIDA: Come on baby! We know.

BASCOMB: Rudolph West is a tall 63 year old, missing most of his teeth, wearing an oversized trench coat. He says he’s never heard of the gleaners but he loves the idea.

WEST: I think it’s a beautiful thing. It’s charitable, someone’s taking the initiative to try to do something for others.

BASCOMB: West lives at the Y, and says he doesn’t have access to cooking facilities so he can’t use a lot of the vegetables, but he’s touched by the thought of the gleaners collecting food for the less fortunate.

WEST: It’s very helpful, and it’s good to be charitable, you know. Pay your tithes, that’s my motto. I’m a very religious person, which is a personal bond but I hold dearly in my heart and I shed tears over stuff like that. It shows how you can show piety like Jesus had. He was humble and submissive. That’s a good trait, a good characteristic, and I like that.

The food pantry in the basement of the Food for Free basement. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: So a charitable tradition that dates back to before the time of Jesus is alive and well here in Boston thanks to generous farmers and volunteers.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb at the Food for Free pantry in Cambridge.

CURWOOD: The Boston Area Gleaners have grown since Bobby reported this story last November - they’re on track to double their annual harvest and collect 150,000 lbs from about 30 farms. They plan to deliver over 20,000 pounds of greens and roots and squash to pantries for Thanksgiving.

Related links:

- Food for Free

- Boston Area Gleaners

[MUSIC: The Whitest Boy Alive “Golden Cage” from Dreams (Asound/Bubbles 2006)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...health-giving foods for you and the planet. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Miles Davis “Blue in Green” from Kind Of Blue (Columbia 1959) ]

Plains Bison

Bison come. They were 60 million once, but now are so few in number. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood. Part of protecting the heritage of North America has involved restoring the bison to the Great Plains. Wes Olson brought them back to Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan, and he served as Mark Seth Lender’s guide there. On three separate occasions Mark found himself surrounded by the entire bison herd.

Plains Bison, Grasslands National Park, Saskatchewan

© 2014 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

The Grasslands’ last bloom, wheat and burdock blanket the plains. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

[BIRD SONG; DISTANT BISON GRUNTING AND LOWING]

LENDER: Imagine now the retreat of the Ice. The vastness left behind, the ruins of the land all scree and gravel like a riverbed gone dry. 20,000 years of cloud and cold.

Then grass…

The greening of the plains....

Birdsong breaks the silence like a candle. And out of the past, Bison come.

The bulk of their looming shapes, the brown hair curled and coiled by eons of weather none of us could imagine, or endure.

And steady on they come.

Buffalo berries weigh down the branches from which they hang. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

The Grasslands in Fall’s last bloom. The tall seed heads of primitive wheat swaying in the first of the morning. The yellow heliotrope in clusters all along the route of parade and the red rust stalks of burdock like pennants flying. Buffalo berries red as blood spilling over and pulling the branches down. And the grass is sweet as clover.

In the fading afternoon two great bulls, beards barbed, like Zedekiah and Nebuchadnezzar face each other down.

Two bulls bow their heads and clash; a dramatic battle ensues. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

They grunt, like mountains rumbling.

They back and brace and root to the ground.

They turn, their horns bow down, their breath sharp as a blade, eyes wide as the world and blind to any world that is not each other.

The move, that is slow and fast and comes without warning: the hook the tear the head-on rush!

…A breaking apart

…A turning away.

…A great dust bath in the end as if nothing ever happened.

A cow nurses her new calf, the herd’s next generation. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

And the cow beside them only goes on with her grazing; the making of milk; the nursing of her new red calf. And they all move off into the last of the day that once was morning.

Around me now Bison part like a river around an insignificant stone. They seem so many! They are so few: 60 million strong they were! They merge into the blue green of the land and the odor of ice lingers though the day was 100 degrees and the plains all a hazy shimmer under a barren midnight sun of a moon.

Bison low in the distance and the dark.

CURWOOD: You can see Mark Seth Lender‘s photographs of these bison at our website LOE.org.

Bison Dust Bath, Grasslands National Park, Saskatchewan from Mark Seth Lender on Vimeo.

Related links:

- Wes Olson

- Tourism Saskatchewan

- The Crossings Resort

Beyond the Headlines

Over 31,000 clean energy jobs were found in Ohio’s report; that is 25% more than thought to have existed. (Photo: Toyota UK; Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Off to Conyers, Georgia now to find out what’s happening beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter publishes Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org, and he’s on the line. Hi, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Steve. Let’s talk about an apparent clean energy cover-up and a fossil fuel divorce. We’ll start with a tale from the Heartland – Ohio to be exact - where a state agency paid $435,000 for a comprehensive survey of the state of clean energy jobs in the state of Ohio. The report delivered some very strong and promising news on clean energy. They counted over 31,000 clean energy jobs – that’s 25 percent more than even wind and solar supporters had thought were there. The only problem is that the state didn’t want to hear about it, and didn’t deliver the report to anyone.

CURWOOD: Huh, they sat on a good news report? Why?

DYKSTRA: They hid the report for over a year. Wright State University and a national energy research firm, ICF, were chosen to prepare the report in 2012. Governor John Kasich was backing a bill to slow down alternative energy by freezing the state’s renewable energy standards. The report, with its good economic news for wind and solar, was potential ammunition for clean energy advocates and, whoops, the report disappeared for over a year, during which time the bill was passed and signed by the Governor.

CURWOOD: So how did they explain the disappearance, and how did the information eventually come out?

DYKSTRA: Well, I’ll answer the second question first: a reporter named Dan Gearino of the Columbus Dispatch got his hands on the report and filed a story on it last week. A state government spokesman said they buried the report because it had flawed data, but they never really said what the flaws were, and the report sat on a shelf for over a year before Ohio even told the folks who had prepared the report that there was a problem. Lo and behold, the state government released much of its info about the clean energy report on the same day Governor Kasich signed into law the bill that held back clean energy standards.

CURWOOD: So that’s the possible clean energy cover-up, and, hey, you said you’ve also got a tale about a fossil-fueled divorce?

Harold Hamm is one of the 25 wealthiest people in the US. Much of his fortune came from fracking in North Dakota. (Photo: David Shankbone; CC BY 3.0)

DYKSTRA: Right, this past week, a billion-dollar fracking divorce settlement. Harold Hamm is one of the 25 richest people in America, a tycoon who struck it rich in the fracking bonanza in North Dakota, one of the biggest oil booms in decades. But Mr. Hamm’s marriage has gone bust, and a judge has ruled that Sue Ann Hamm will also join the billionaire’s club – she’ll eventually get a billion-dollar divorce settlement, one of the biggest in history.

CURWOOD: Wow, you’d think that a guy shrewd enough to become an oil billionaire would have an army of lawyers building him a bullet-proof prenuptial agreement, huh?

DYKSTRA: Funny thing about that – one of his staff lawyers at Continental Resources at the time of their wedding in 1988 was the soon-to-be-former Mrs. Hamm. She’s already collected $25 million, she’ll get $315 million by the end of the year, and after that, under the ruling by an Oklahoma judge, she’ll have to squeeze by on an additional $7 million a month. And she says, by the way, it’s not enough bacon – she may appeal the tiny judgment, and Mr. Hamm will be worth only $17 billion, maybe a little less, instead of $18 billion, but he’s available.

CURWOOD: So maybe women will be lining up to marry Mr. Hamm.

DYKSTRA: Actually his field of potential suitors just doubled. Thanks to another court ruling last month, Oklahoma now has marriage equality.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] OK. Peter, hey, tell me what’s on the history calendar this week?

Emails stolen from University of East Anglia climate scientists were spun to support climate skeptics’ arguments. (Photo: Blue Square Thing; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, it’s hard to believe it’s been five years since the so-called “ClimateGate” incident. Thousands of email exchanges and other files from climate scientists were stolen from the University of East Anglia computer system, promptly found their way into the hands of columnists and political operatives who deny climate change, and it all really knocked the climate science community for a loop. A few widely publicized items from those thousands of emails were spun to make it sound like climate scientists were engaging in a vast conspiracy to make it all up.

CURWOOD: And as I recall this all happened just before the big Copenhagen Climate Summit, right?

DYKSTRA: Well, correct, and that made it a big story. The police treated the hacking as a crime, but never solved it. Climate deniers treated it as a media bonanza, and they still do five years later. Multiple inquiries in the UK and the US exonerated the scientists, who were at worst maybe guilty of some poorly-chosen words and catty remarks in the emails, you know, just like real people.

CURWOOD: Climate scientists behaving like real people. What will they think of next?

DYKSTRA: I don’t know, Steve.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is publisher of DailyClimate.org and Environmental Health News – that’s EHN.org. Talk to you soon, Peter.

DYKSTRA: OK, Steve, thanks, we'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Read The Columbus Dispatch’s report on Ohio’s “green” energy jobs survey and its disappearance.

- Fracking billionaire Harold Hamm to Pay One of the Biggest Divorce Settlements in History

- “Climate-gate,” how hacked e-mails from scientists were spun for climate science dispute

- The Climatic Research Unit (CRU) is a component of the University of East Anglia and is one of the leading institutions concerned with the study of natural and anthropogenic climate change.

[MUSIC: Frankie Rose “Night Swim” from Interstellar (Slumberland 2012)]

Foods for Health

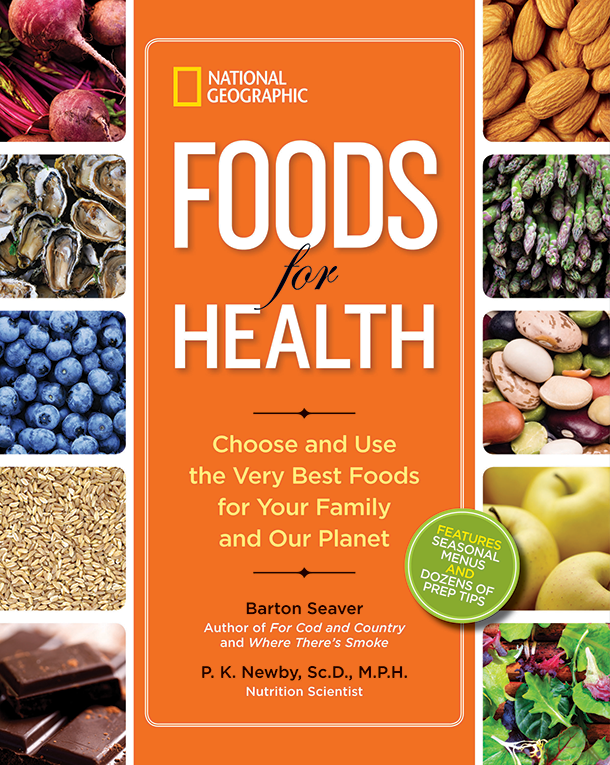

Chef and author Barton Seaver co-wrote Foods for Health—Choose and Use the Very Best Foods for Your Family and Our Planet. (Photo: Courtesy of National Geographic)

CURWOOD: Now is the season here in the US when many of us gather with friends and family around a table piled up with traditional and favorite foods, to celebrate and give thanks. Some of those foods will be delicious, some will be healthy and to highlight those that are both delicious and healthy we turn now to celebrity chef Barton Seaver.

Peel back an orange’s dimpled skin to taste its sweet, fibrous flesh, highly nutritious in its raw form. Chef Seaver uses oranges and fresh herbs for zest and spice in National Geographic’s Foods for Health. (Photo: AnjelikaGr/Shutterstock)

Barton and Harvard nutritionist P.K. Newby have just published a new book called "Foods for Health: Choose and use the very best foods for your family and our planet.” Barton Seaver also directs the Healthy and Sustainable Food Program at the Harvard School of Public Health. Welcome to Living on Earth, Barton.

SEAVER: Hi, Steve, it’s great to be with you. Thanks for having me!

CURWOOD: Foods for health. We think of vegetables, brightly colored things. Am I on the right track here?

SEAVER: Absolutely. Food is the very basis of our health, and I think of the multicolored meals with lots of different vegetables, textures, aromas, tastes, but also it forms the basis of enjoyment. If it's just the same thing over and over again then we are not necessarily on a... destined to be on a path towards health and ultimately food has to be delicious because the only food that is helpful for us is the food that actually makes it into our face. So it's got to be enjoyable too.

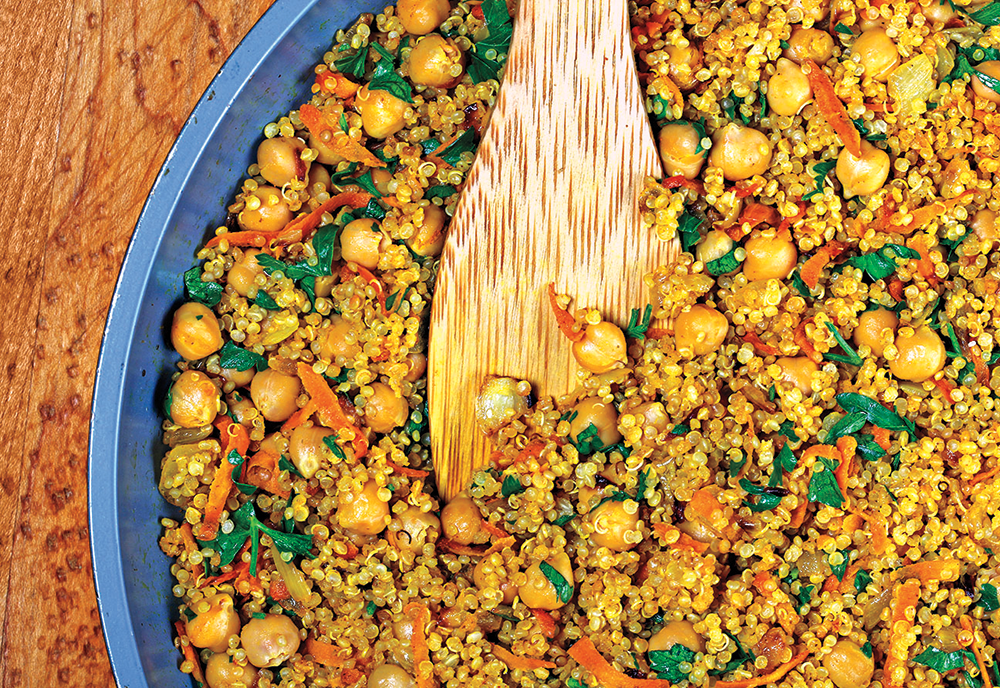

CURWOOD: Now, in your book, Barton, you've listed seasonal menus to highlight sustainable healthy foods and how to prepare them in tasty ways. So as we get towards the end of the fall and many places in America actually seem to have stepped into winter, could you explain what you decided to include in your Autumn Splendor menu and why?

Winter squash plays a large part in autumn and winter menus featured in National Geographic’s Foods for Health. Eating a balanced diet high in vegetables including winter squash can help lower cholesterol, stabilize blood pressure, and support heart and brain health. (Photo: Keith Szafranski/iStockphoto)

SEAVER: Well, Autumn Splendor, I think, it's the most fun time of year to cook by far. It is when you are switching between seasons and you still have just a little bit of summer's bounty left over - those fresh clean flavors that need little adulteration for them to be sexy and exciting - but you're also moving into those deep, rich, robust, soul-warming flavors of squash and this is when food becomes, to me, it's most effective in that we nourish our bodies with far more than calories when we sit down to a meal and especially around the holidays I think we are most acutely aware of that. And that to me is the splendor of autumn.

CURWOOD: Now, you start with spice mulled apple cider.

SEAVER: When people walk into the house they should immediately feel as though they're being welcomed, and filling the house with that sweet slightly bitter warm spice aroma of mulling ciders, you know there's no more generous welcome then that.

CURWOOD: Now what about the salad?

Classic coleslaw recipes tend to drown shredded cabbage in a sea of mayonnaise, which adds a lot of extra calories and dilutes the crunch and flavor cabbage provides. National Geographic’s Foods for Health suggests substituting a smaller amount of nonfat Greek yogurt for the mayo for a change. Sliced cabbage can also be served simply with vinegar and, if left to sit, will quickly pickle for an interesting side dish. (Photo: Siamionau pavel/Shutterstock)

SEAVER: The roasted squash panzanella, and this harkens back to an Italian tradition where you use day-old bread, you mix it in with vinaigrette and moist roasted vegetables and nuts and raisins or something like that. It really provides a hearty filling and yet interesting component to a meal that's a little bit unexpected, and it offers us an opportunity to really introduce vegetables and that allows for a healthier meal all throughout.

CURWOOD: Alright, let's move on now to the entree, and I'm really getting hungry.

SEAVER: Coming into the fall we often think of turkey, roast turkey, roasted chicken, beef stews, but mixing it up a little bit with something I love to do, quinoa cakes. Simply boil the quinoa down until it's nice and soft and mix it with a little bit of breadcrumbs, maybe an egg yolk, and then sauté those up in a little olive oil and butter and then serve those alongside roasted sweet potatoes with the aromatic lovely crunch of a cilantro almond pesto, and then put it on the side with a little bit of sweet bitter component such as the braised broccoli with raisins and almonds. The raisins to add sweetness, balancing out that brassica bitterness and then the almonds adding crunch to the entire dish.

National Geographic’s Foods for Health highlights quinoa. Highly sustainable, quinoa has become immensely popular in recent years, and 2013 was called the International Year of Quinoa by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. This indigenous and sustainable crop includes all of the essential amino acids, making it a “complete” protein. (Photo: alexsvirid/Shutterstock)

CURWOOD: OK. By this time, I guess we would be ready for dessert.

SEAVER: Desserts that I like to serve in the fall are taking advantage of just the wonderful bounty of fruits that we have such as baked apple, cored and then stuffed with a little bit of sweetened Greek yogurt and then topped with a little bit crunchy granola. And this is healthy, this is delicious, and, wow, this is satisfying as well.

CURWOOD: Barton, in your book you mention turkey as a good source of protein. What's a good turkey?

Roast pumpkin seeds yourself or purchase unsalted ones. Seaver points out in this new book National Geographic’s Foods for Health that pumpkin seeds have about as much protein as almonds. (Photo: Ildi Papp/Shutterstock)

SEAVER: Well, a good turkey is one that's raised in a natural way. We eat turkey in America very rarely, but for one occasion, and when that turkey hits the table we have this very Norman Rockwell vision of this incredible round bird, plump breasts, large meaty legs sticking out perfectly trussed with a golden brown crackly skin. Well, that's not what the bird looks like in nature and so the farming techniques that are used typically tend towards creating a product that looks good on the table. And in order to achieve the aesthetic we desire on the table we have to sort of visit a number of abuses on those turkeys, from incredible density in the farming operations which leads to disease vectors, therefore, necessitating antibiotic use, growth hormones to plump those breasts, and so I think the opportunity here is really, as Americans, to shift our expectations of what we expect our food to be. Do we expect it to be aesthetically perfect? Something that doesn't really exist in nature, or do we want to really celebrate what that animal should be?

CURWOOD: So how should we select and prepare turkey?

SEAVER: Well, I think that there is a rising popularity and availability of heritage breed turkeys, Red Bourbon turkeys, various breeds that have been farmed for centuries, and these birds all have intricate nuanced flavors much like heirloom tomatoes, they all taste different. And these birds also have slightly different sort of physical characteristics, small slender breasts, meaty big rich thighs and legs that are actually meant to carry the turkey around. And because that bird is not as meaty and plump and rich as the other birds that you commonly find in the supermarket, well, guess what? That leaves plenty more room for all those delicious vegetables and sides that fill up the table, that to me are the best part of Thanksgiving, and are also the healthiest part.

In National Geographic’s Foods for Health, Seaver notes that each winter squash has a distinct flavor—experiment to find the ones you like best. (Photo: spectrumblue/Shutterstock)

CURWOOD: So whether you live in the city or the country, come the end of the summer harvest season sometimes hopefully there's more than you can eat. How you feel about frozen vegetables?

SEAVER: I grew up on frozen vegetables - that was part of the fluency I learned as a child that allowed me to pursue a career in food. And dinner was 365 nights a year and it was cooked from scratch, and more often than not it was Jolly Green Giant vegetables frozen out of the bag, you know, peas, but my dad understood what a little bit of salt and a tiny pat of butter could do for a vegetable and so if that's the cost structure you're operating on...fabulous. Just eating vegetables is a great start to ameliorating the diets in America that are currently not doing us any favors.

CURWOOD: Tell me, what menus are you planning for the holidays?

Barton Seaver is an executive chef, Director of the Healthy and Sustainable Food Program at the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard School of Public Health, and co-author of National Geographic’s Foods for Health.

SEAVER: Well, we’ve got a farm right down the street the raises heritage turkeys. We got a turkey that’s probably a little too big for the number of people we're serving, but my whole thing is the sides, that mashed sweet potatoes with the little bit of orange juice in there to give it a little aromatic punch topped with a little bit of pecans, and maple syrup, and spicy broccoli, caramelized celery, walnuts and cranberry sauce to go alongside of it, plenty of light bright red wine like a Beaujolais or Pinot Noir, oyster stew, you name it. This is a chance to do exactly what Thanksgiving was designed to do, to give us a moment of reflection, celebration of the bounty we're so fortunate to have. Since I live on the coast of Maine, I'll probably be throwing a lobster or two into my dinner.

CURWOOD: Barton Seaver is a chef and Director of the Healthy and Sustainable Food Program at the Harvard Center of Global Health and the Environment, and his new book is called "Foods for Health" which he wrote with nutritionist P.K. Newby. Thanks so much for your time today, Barton.

CURWOOD: Oh, it's such a pleasure, Steve, thanks for having me on.

Related links:

- More about Barton Seaver’s new book, Foods for Health-Choose the Very Best Foods for Your Family and the Planet.

- Barton Seaver is Director of the Healthy and Sustainable Food Program at the Center for Health and the Global Environment at the Harvard School of Public Health.

- More about nutritionist P.K. Newby

[MUSIC: Lambchop “Betty’s Overture” from Mr. M (Merge 2012)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. And we give thanks to you for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth