November 28, 2014

Air Date: November 28, 2014

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

The Best and Worst Cities Preparing For Climate Change

View the page for this story

Global warming presents cities around the world with challenges that range from drought to storms to rising sea levels. Jeff Turrentine of OnEarth magazine tells Steve Curwood which cities are doing the most to prepare climate change, and which cities have yet to plan ahead. (06:15)

Car-Free To Become Carefree In Helsinki

View the page for this story

Finland’s capital of Helsinki is growing fast and the city’s current transportation system is overstretched and short of money. Helsinki’s Director of Transport and Traffic Planning Ville Lehmuskoski tells host Steve Curwood about the city’s novel “mobility as a service” model and how investing in shared modes of transit based on needs will save money, reduce traffic congestion, and improve travel comfort and convenience. (06:25)

Danish Green Roofs

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark, was named Europe’s greenest capital in 2014. It’s partly due to the ubiquitous bike paths and the ambitious renewable energy goals, but as Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer reports, also due to the many green roofs the city is installing to soak up excess rain and cool the capital. (08:55)

Urban Acupuncture To Cure City Ills

View the page for this story

Curitiba in Brazil has been called “the best planned city in the world.” Host Steve Curwood speaks to Jaime Lerner, the former mayor who revolutionized Curitiba’s public transit system, cleaned up waste and the streets, about the kinds of public engagement that can make cities vibrant again. All it takes, says Lerner, is a pinprick. (10:25)

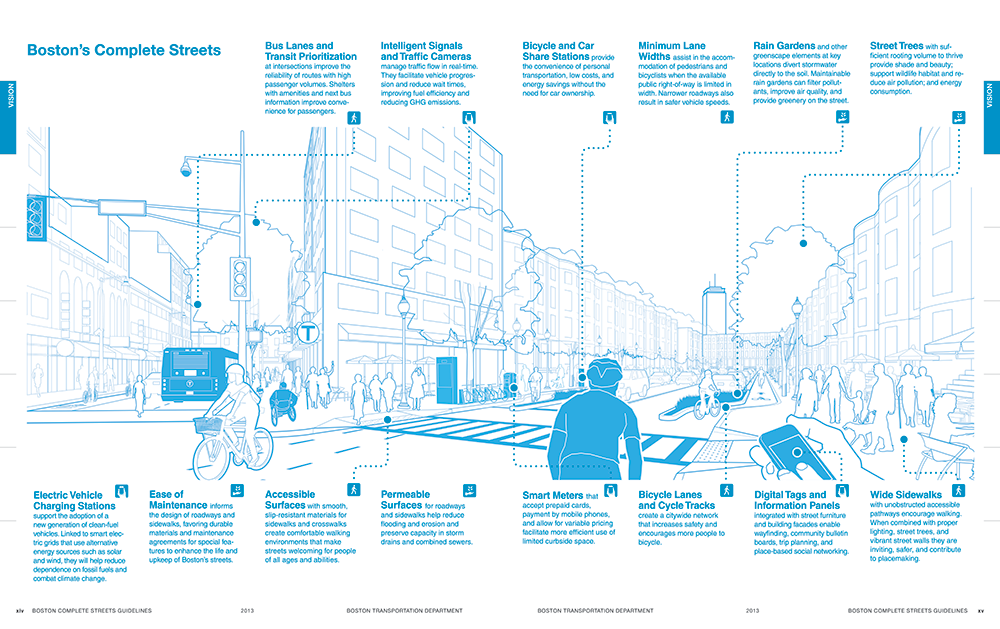

Building Complete Streets

/ Jake LucasView the page for this story

After the Second World War, planners built roads with wide lanes and high speed limits to accommodate trucks carrying goods. But these wide fast roads were unfriendly to pedestrians and cyclists in towns and cities, and as Living on Earth’s Jake Lucas reports, cities are redesigning streets with people in mind. The concept of “Complete Streets” is taking hold all over, including Boston’s Allston neighborhood. (06:00)

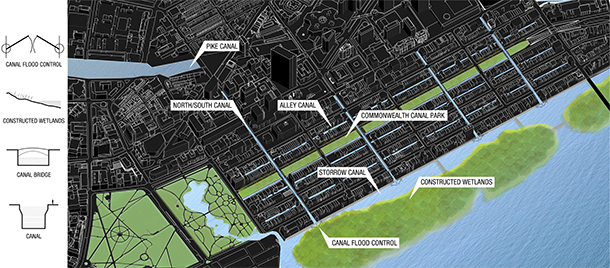

Canals in Boston?

View the page for this story

Boston is one of the most vulnerable cities in the world to sea level rise. Now urban planners are looking at ways the city can adapt its infrastructure to accommodate storm surges and rising tides. Dennis Carlberg of the Urban Land Institute speaks with host Steve Curwood about an ambitious plan to save Boston's historic Back Bay neighborhood from the ravages of rising waters. (09:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Jeff Turrentine, Ville Lehmuskoski, Jaime Lerner, Dennis Carlberg

REPORTERS: Jake Lucas, Helen Palmer

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Today we look at cities preparing, planning and building defenses against global warming and its effects. In Copenhagen – they’re installing gardens on their rooftops.

RØMØ: In the future due to the climate change, we will have more intensive rains, and we know that green roofs can absorb, and delay the rainwater.

CURWOOD: How green roofs work in practice. Also, in Boston with a key part of downtown built on a filled in bay – a radical rethink of how to cope with rising sea level.

CARLBERG: What does it look to live with water in an urban environment? So our group came up with a number of ideas and the one that really floated to the top, sorry the pun, was bringing canals into the Back Bay.

CURWOOD: Cities, climate change, urban planning and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

The Best and Worst Cities Preparing For Climate Change

As a consequence of rising demand and shrinking supply, Lake Mead has dropped 130 feet in the last fourteen years, and Las Vegas, which depends upon the artificial reservoir for 90 percent of its water, faces severe water shortages. (Photo: Kyoba; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Dkaha, the capital of Bangladesh, is home to millions of climate refugees forced out of their homes elsewhere in the country. But the city itself lies just twelve feet above sea level, and flooding is an ever-increasing occurrence, earning this city a spot on Turrentine’s list of those “headed for big trouble.” (Photo: Sumaiya Ahmed; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Today we are taking a special look at cities, where already more than half of us around the world live, and more and more of us are moving in. While the urban footprint covers only four percent of the land, cities consume three quarters of all energy, and generate 70 percent of the global warming gases from humans. When Hurricane Sandy brought floodwaters onto the streets of New York in 2012 it underscored how vulnerable our cities are, and that to adapt to rising seas, increased drought, more frequent storms, and slow global warming, we must start with cities. Jeff Turrentine is a writer and editor with OnEarth magazine who has identified some of the cities that are doing the most and the least to prepare for climate change. He says among those who aren’t looking ahead are two sprawling cities in the dry American Southwest: Phoenix and Las Vegas.

TURRENTINE: You know, 60 years ago, nighttime temperatures in Phoenix never crept above 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Now, nights in the 90s are commonplace. Their water table has dropped by 400 feet over the last 50 years, which corresponds to the amazing population growth and urban sprawl that you characterize with a city. We're talking about a city that's probably going to have temperatures in the 130s by the end of the century and they're just not prepared in terms of water and resources.

CURWOOD: And Vegas?

TURRENTINE: Las Vegas is in a similar boat. Las Vegas is a city that gets about four inches of water annually, 90 percent of which comes from Lake Mead—that's drying out. Seventy percent of the water that Las Vegas gets goes toward the watering of lawns, golf courses and parks. So they're using their water in what some might say is a profligate way, and Lake Mead's water level in the meantime has dropped 130 feet in the last 14 years.

Rotterdam’s Floating Pavilion prototype visually signifies its seriousness about climate change. Less visible, but of immense importance, is Rotterdam Climate Proof, the city’s robust climate adaptation plan. (Photo: Rick Ligthelm; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, where else in the US?

TURRENTINE: Well, in the US, the one city that is really in an unfortunate state is Miami Beach, Florida, for just the opposite reason. It's not going to dry up; it's going to flood. Already, floods are pretty routine in Miami Beach. Every autumn it floods and the drainage system in the city is reversed so that sea water and sewage start to come up through storm drains. There's one researcher at the University of Miami who believes that Miami Beach really can't survive until the end of the century. It's average elevation is about four-and-a-half feet above sea level. That's 18 inches below what is considered to be the upper range estimate of sea level rise for South Florida by the end of the century. It would turn the city into a bathtub, basically.

Wetland restoration may become one part of New York City’s overall strategy for guarding against future hurricanes, laid out in a $19.5 billion plan entitled “A Stronger, More Resilient New York.” (Photo: Kelly Fike /U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

CURWOOD: OK. It may be too late to save Miami Beach, but what cities around the world, in your view, are doing a good job to prepare for climate change?

TURRENTINE: Well, sort of the flip side of Miami Beach is the city Rotterdam in the Netherlands. It's Europe's biggest port, and even though it's not a city that a lot of American tourist may know, it's a very big deal indeed to the European Union. So they have put all of their effort and energy and quite a bit of money into making sure that Rotterdam stays above water. One of the things they've done is create this incredible plan called Rotterdam Climate Proof, which really focuses on sea level rise in making sure that the city doesn't get flooded. One of the most amazing things about Rotterdam is that they’ve created what might arguably be called climate change's first tourist attraction. In the bay there, there are these three giant floating jellyfish-like contraptions that people love to go and visit. What they really are, are kind of models of how cities might need to start creating floating infrastructure in the future if they want to deal with rising sea levels.

Johannesburg’s new bus rapid-transit system, used by 50,000 people daily, helped earn the city a spot on a list of five cities that are preparing for climate change. (Photo: Jeppestown; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Hmm. So if you're a hospitality business, go for the cruise ship rather than the hotel?

TURRENTINE: [LAUGHS] Maybe. Maybe.

CURWOOD: So what other cities around the world are taking climate change seriously?

TURRENTINE: Well, in United States certainly I don't think you could understate the degree to which Hurricane Sandy made a believer out of New York City. When that occurred in 2012 and dozens of people were killed and it led to $20 billions worth of damage, Mayor Bloomberg another city officials responded vigorously with a package of more than 250 different initiatives that were going to be implemented over the years, pretty much all of which were designed to minimize the city's vulnerability to coastal flooding and storm surge.

Mexico City used to be infamous for its choking smog, photographed here in 1981. Since then, the city has significantly reduced its air pollution: its all-time record low of 8 “good air days” in 1992 became a remarkable 248 days in 2012. (Photo: George Lamson; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

TURRENTINE: It's a 438-page document and the plan is about $20 billion dollars of money going to these different mitigation measures. Three-fourths of that is going to be about rebuilding infrastructure, but interestingly $5 billion or so is reserved for exploring new technologies and kind of playing around with new ideas to see if there might be some better technique or technology out there—the talk of seawalls and armored levies and green infrastructure like wetlands and swamplands and sand dunes and things like that.

CURWOOD: And where are the other cities in North America on the list?

TURRENTINE: Well, one city that doesn't have to deal so much with flooding, but has had incredible air pollution issues, of course, is Mexico City. In 1992, the United Nations declared Mexico City to be the world's most polluted city. There was one report around that same time that speculated that as many as 100,000 children in the metropolitan area could be dying as a direct result of air pollution. Breathing in the city was just a dangerous thing to do and as global temperatures rise and air pollution increases and ozone increases, the people in that city would've been disproportionately feeling that global burden. The government got serious about it; they created a plan that was going to curb emissions of greenhouse gases and pollutants in Mexico City by 7.7 million metric tons between 2008 and 2012.

Flooding in Miami Beach. Experts worry that the city could be underwater by the end of the century. (Photo: Nathan Forget; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

TURRENTINE: To the surprise of the entire world they surpassed that goal by 10 percent and suddenly cities all around the world that were dealing with air pollution were looking at Mexico City as a model of inspiration rather than a model of peril and danger.

CURWOOD: Jeff Turrentine is an editor and writer with OnEarth magazine. Thanks for taking the time today, Jeff.

TURRENTINE: Thank you very much.

Despite cutting its water use by a third since 2002, Las Vegas, which receives only four inches of rain annually, still uses approximately 220 gallons per capita per day (GPCD). That’s more than twice California’s statewide average water consumption. (Photo: Zach Dischner; Flickr CC BY 2.0)

Related links:

- Read Jeff Turrentine’s article about cities preparing for climate change

- More on cities in the latest addition of OnEarth magazine

Car-Free To Become Carefree In Helsinki

A tram in the Helsinki winter. City Planners predict that current roadways and subways will not be able to support Helsinki’s growing population unless a smart phone-based mobility service is implemented to make better use of resources. (Photo: Niklas Sjöblom/City of Helsinki Tourist & Convention Bureau)

CURWOOD: Helsinki is growing fast, and city planners trying to prepare for that growth, realized they needed a better way for people to move around. The public transit system in Finland’s capital city is already overcrowded, and there isn’t the money to keep investing in new roads and highways. So, they turned to the novel idea of treating mobility as a service, and using a mix of all modes of transport that would take the job of figuring out how to get from point A to point B out of users’ hands. Ville Lehmuskoski is the Director of Transport and Traffic Planning for Helsinki, and he joins us now from a park bench in the city to talk about the plans. Welcome to Living on Earth.

LEHMUSKOSKI: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about this idea of mobility as a service. What does it mean at the end of the day?

LEHMUSKOSKI: The basic idea is you have a transportation operator that takes care of arranging your transport. So you have an interface provided by this transport operator and in the interface you test the points, A and point B, and then get the options and the prices for different options, for example, local public transport or long distance public transport, carsharing, city bike system, automobile rental system, or you have a mixture of all these.

Helsinki has a range of transport modes: train, bus, bicycle and walking. “Mobility as a Service” would build upon this, allowing people to use bikes, cars and public transport on a need basis. (Photo: Aapo Haapanen; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: So paint a picture for me would you please? If I'm a resident of a future Helsinki where this newly redesigned transportation system is in place, how do I get from point A to point B?

LEHMUSKOSKI: In the current mobility system, people own their cars. They just have their car or two cars that the family has. But in your life you have a several kind of different situations and, if you use mobility as a service, for every trip you get just the kind of car that you need, that you want. For example, at some point you need your Toyota Corolla, at some point you would like to have a van, at some point you would like to have some sport car, Ferrari or something like that, and you also have the possibility to take public transport, take bikes, take also different kind of bikes. You see you can always take the best option. And also important is that you don't have to invest. The investment cost is very big when we talk about cars. In Finland, a car as in America, it costs several thousand Euros and if you use it as a service, you don't have that investment cost. You just pay by use.

CURWOOD: So how does this work? I pick up the phone and call my service provider or do I go online? How would I engage?

LEHMUSKOSKI: Well, of course, that depends on your mobility operator, but in my imagination I see that it's a mobile phone application or computer application.

CURWOOD: Who will these mobility managers be?

LEHMUSKOSKI: Maybe they are the companies that are our mobile phone operators today, or maybe they are just totally new companies or built up around today's public transport companies or maybe a mixture of all these.

CURWOOD: Now, just how far along are you there in Helsinki in the process of adopting this system?

LEHMUSKOSKI: We have already some small pilots, but I would say that traffic as a service in the way that I described to you will take a least a few years, maybe five years to be reality.

A view of Helsinki from the air. (Photo: Suomen Ilmakuva Oy/Visit Helsinki)

CURWOOD: To what extent is a core goal of this plan to make owning a car basically unnecessary in Helsinki?

LEHMUSKOSKI: Well on our streets there is no place for expanding car traffic but we don't have any fixed numbers for how many cars we want away by using this system. But, I'm very sure that when you have all these options and you pay per use, not as an investment then a big number of citizens will use sustainable modes instead of car. I would say that the change will be dramatic.

CURWOOD: What about the cost of all this? How much is it going to cost to really build out and maintain a system like this, compared to the present?

LEHMUSKOSKI: Hmm, the back of the system actually needs not any rugged science software, so it will not be a big cost. But when we talk about economical efficiency of public transit system we need to remember that, at least in Finland, that passenger cars are not in use 96 or 97 percent of the time. And all the time anyway, the capital is tied up to the car, and that's a very ineffective use of capital. That's lazy money, I would say. When there's not that big a need for capital in cars, it makes the system as a whole much more effective in terms of efficiency of both public money and private money.

CURWOOD: So your expectation then that this is going to be cheaper for everyone once it's working.

LEHMUSKOSKI: Yes, this is going to be cheaper for the private person, the person that uses the system, and it will also be cheaper for the society.

Ville Lehmuskoski is Helsinki’s Director of Transport and Traffic Planning. (Photo: Courtesy of Ville Lehmuskoski)

CURWOOD: Let's fast forward, say, a decade. What do you imagine the streets of Helsinki would look like, and how much parking would be available?

LEHMUSKOSKI: In the future, there's a lot of parking available because the cars are moving. Those cars that are needed, they take one passenger to place A to place B, then they continue, so the amount of cars is maybe half of today or even less. So there's much space in the city; there are much more cyclists, much more public transport users. And there are happy car users.

CURWOOD: Ville Lehmuskoski is the Director of Transport and Traffic Planning for the city of Helsinki, Finland. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

LEHMUSKOSKI: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- “Mobility as a Service” Thesis

- The Helsinki Times’ story on the future of Helsinki transport

- Plans to implement “Mobility as a Service”

- Intelligent Transportation Systems Finland, an organization that promotes smarter transportation technology and planning

[MUSIC: Phoenix from “Congratulations” from Alphabetical (Source 2004)]

CURWOOD: Coming up...we stay up in Scandinavia for another take on creating a green, livable city. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTWAY MUSIC: Gene Ammons from “I’m Glad there is you” from The Gene Ammons Story: Gentle Jug (Prestige 1992)]

Danish Green Roofs

Dorthe Rømø, a biologist and Project Manager of Green Roofs Copenhagen stands with Per Malmos is the Director of Responsible Sales with Malmos, a company that specializes in creating green spaces. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. About 550 miles southwest from Helsinki lies Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. It's a prosperous, urbane city of just over half a million; a city of high prices, high taxes and extraordinary attention to the environment. Copenhagen earned the official European seal of approval in 2014, as the EU officially anointed it as EU's greenest city. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer went there and found it, well, green.

[CITY SOUNDS, TRAFFIC, TALKING]

Strawberries grow in raised garden beds on the roof of the National Archives. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: The windy port of Copenhagen is truly the greenest of green cities. Beyond the busy harbor, and the statue of the Little Mermaid, massive windmills in the ocean and on the industrial island of Christianshaven spin in the brisk wind.

A brand new bike path loops and sweeps at third floor level between banks and businesses, to link the inner harbor through a series of parks and gardens on the rooftops to the railway station. After all, it's a city where just about everybody rides bicycles.

Dorthe Rømø, a consultant to the city's Department of Planning and Climate Adaptation, has a pretty good idea why the city keeps winning green awards.

Flower beds, 3 feet wide, run along the building’s edge and soak up the rain in place of gutters. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

RØMØ: I think it's a matter of many different aspects – it's due to our focus on renewable energy. It's a focus on sustainable traffic. You know that the city of Copenhagen is doing many things for bicycles in the city, and then we also have a tremendous focus on greening the city. A part of that is to install more green roofs, and have focus on wherever there’s space to green the area, transform the grey to the green.

PALMER: Urban planners tout the benefits of installing plants on rooftops as insulation and as an antidote to urban heat islands - not a problem you'd expect for a place that's on roughly the same latitude as Moscow and Goose Bay. But green roofs have been mandatory on suitable new buildings in Copenhagen since 2010, and Dorthe Rømø says you could be wrong about what the city needs to plan for.

RØMØ: In the future due to the climate change, we will expect there will come higher temperatures in our city – but that's only one aspect of the initiatives about green roofs in the city because another very important aspect is that we know and we are aware that we will have more intensive rains and more rain in general and, due to that we know that green roofs and green area can absorb, infiltrate, evaporate and delay the rainwater.

[BIRDS CHIRP]

Gardens blanket the roofs of shops in Copenhagen with distant windmills. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: Now, we’re standing here actually on one of your green roofs. Describe where we are and what exactly we’re seeing around us.

RØMØ: Yeah. We are pretty close to the inner harbor and we are in the middle of a green botanical corridor. We are on the new Danish National Archive, and the unique about this is that it's one amongst other green roofs that's connected and accessible for the public to walk from one area in the city to another area in the city, and you can in fact also take a bicycle and cycle from one area to another area.

PALMER: So it's a basically like a system of parks as it were on top of roofs?

Rooftop gardens provide additional habitat for birds and pollinators. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

RØMØ: Exactly, and this green roof which is one of my favorite here in Copenhagen, it's an option for you to sit on benches surrounded with strawberry beds which is designed to create silent gardens alongside the whole project.

PALMER: The rooftop of the National Archives is about the size of a football field but it looks for all the world like a meadow; there's vetch and thyme and thrift and nodding grasses interspersed with those strawberry beds and benches bordered by trellises clad in purple clematis and Travellers Joy. The studied artlessness of the garden is due to complicated planning and very careful construction, says Per Malmos, whose company installed the roof.

MALMOS: First of all you have to make sure that you don't make leaks—you don't disturb the membrane when you install it. You have to be sure that the waterproofing protecting against the roots growing inside the membrane.

Rooftop gardens overlook the harbor. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: Ah, so it's got to be totally impervious to water but also tough enough so the roots don't make holes through it.

MALMOS: Yes.

PALMER: Malmos had brought along samples of the materials layered underneath the plants on the roof to protect the building below from leaks, and collect the rainwater so the garden needs no irrigation.

MALMOS: Then you take care of the membrane, and on top of it you place a drainage layer, so you can be sure when it will rain very heavily the water can still running away because if not, it will flood and be muddy and you couldn't walk on it.

PALMER: Right. So what you've got here is a layer of something that looks like felt and on top of this is—it looks for all the world like what we make egg cartons out of.

The famous Little Mermaid statue overlooks the harbor, windmills in the distance. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

MALMOS: Yeah, it's a sandwich layer underneath, and then you have a layer of substrate. And it's not normal top soil; it's a top soil which is light. It sucks the water, so it's full of water.

PALMER: It's a system that's been developed over years to work really well, and now the meadow and flowerbeds are thriving. Dorthe Rømø says they provide other benefits.

RØMØ: It create the opportunity to create habitats, to support biodiversity.

PALMER: So biodiversity, you mean, like rabbits in the middle of Copenhagen?

RØMØ: [LAUGHS] Not exactly, but butterflies and bees and birds, and invertebrates like that but also diversity of plants.

Hille Løvig works in a jewelry shop below this rooftop garden. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[BIRDSONG, DISTANT SOUNDS OF THE CITY]

PALMER: It's peaceful walking on the roof. In one corner, there's a group of office workers having a barbecue. Further along, the ramps that lead down to street level are a magnet for local skateboaders.

[SOUNDS OF SKATEBOARDERS]

PALMER: Copenhagen intends to have half its citizens getting to work or school or running errands by bicycle by 2015, and to generate all its power from renewable sources by 2040. Dorthe reckons the city's on track to meet those goals; already 40 percent of its energy is green. It's too soon to know what impact the green roofs have on the carbon balance, but she's sure they affect the citizen's balance and their well-being.

RØMØ: We like to have the view of some beautiful areas, but in fact you can also create these beautiful areas. And I, in fact, have also heard from people they are surprised of being in a silent area even though that you are in the middle of a city.

PALMER: And there are these oases of green not only on houses, hotels and city buildings, but also on parking garages and even on bicycle and storage sheds.

Tourists Bridget Whiting and Trevor Dutt visit from London and stop by Copenhagen’s beautiful rooftop gardens. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

[SOUNDS OF WAVES LAPPING, AND BIRDSONG]

RØMØ: Right at the harbor, the roof of a development of shops and cafes is covered with flowerbeds, benches and walkways but no gutters, because a three-foot-wide bed of stonecrop and sedum along the edge takes up all the rain. I met Hille Løvig up there with her bicycle, taking pictures.

LØVIG: Oh, I think it’s nice; it’s absolutely nice. I’m working just under this roof, so I enjoy it here and I enjoy the water of course. And it's important to have flowers around us. I think I am one of the luckiest [LAUGHS] here in Copenhagen to work in a place like this.

PALMER: Walk further along the harbor and you come across the statue that commemorates Hans Christian Andersen's story, the Little Mermaid. Cruise ships stop here and tourists like to stroll, people like Bridget Whiting from London.

Tammy Chen is a student, originally from Hong Kong, living in Seattle, Washington came to visit the gardens. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

WHITING: Yes, just brilliant, all the bees! And of course we have this problem of the bees, and I'm just so delighted to see them. Isn't it fantastic?

PALMER: Well that's actually part of their thinking, that it provides habitat for insects and everything.

WHITING: Yes, and you can see it’s working. I just love all this; I really do.

PALMER: Still the green roof didn't much impress Tammy Chen. She's originally from Hong Kong, but now lives in Seattle.

CHEN: I think it's not a new idea, definitely you know Tokyo, Japan, like they've been doing it for years. And a lot of Asian cities, they started doing the same thing, and I'm glad you know Copenhagen is doing it as well, you know.

PALMER: Do you think it has an affect on how people feel?

CHEN: Well definitely green is a good color. You know, it brings positive messages, and it's great contrast with the industrial area just right across the canal obviously. So, you know, I think it’s a really nice change.

[BIRDS CHIRPING]

PALMER: And in the end, maybe that's the message: a green city with green roofs can blunt some effects of global warming by soaking up excess rain and sucking up excess carbon and certainly by cheering up the people who live there and visit.

For Living on Earth, I'm Helen Palmer in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Related links:

- Dorthe Rømø assists with Green Roofs Copenhagen, which offers many urban benefits.

- Per Malmos’ company helps to install green landscapes and facilities around Copenhagen.

- World Green Roof Congress Copenhagen 2012

[MUSIC: Pink Floyd “What Do You Want From Me” from The Division Bell (Columbia 1994)]

Urban Acupuncture To Cure City Ills

Curitiba is famous for their rapid bus transit system, which moves people like a train at a fraction of the cost. (Photo: mariordo59; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some say the best-planned city in the world is Curitiba, the eighth largest metropolis in Brazil and the capital of the state of Paraná. And much of the credit goes to the the charismatic architect and urban planner Jaime Lerner, who was mayor of Curitiba three times and twice the governor of Paraná. The path to sustainable success he says is often found in doing simple things quickly that enhance the life of a city. Now in his eighth decade and retired from politics, Jaime Lerner has traveled the world and documented some ways various cities create pleasant and sustainable atmospheres in a book called Urban Acupuncture. And, if you want to improve your city, here’s some of his advice.

Curitiba has almost 600 square feet of green space per resident. (Photo: Guilherme Scholz Portela; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

LERNER: Begin by drawing your city. Are you a regular customer of the stores and services facing along the street? Congratulations! You are now a citizen.

CURWOOD: Now your book isn’t so much a manual about how to make your city sustainable, more sustainable. It’s more an ode to those little things that make a city vibrant—pinpricks you call them. So why did you choose to write a book that focuses on these tiny, little details?

LERNER: I didn’t want to write a manual, because I wanted to provide the people the sense of what makes a city. I love a sign that I saw in Mexico City in a small square: “Better the grace of imperfection than the perfection without grace.” People, they have so many ideas and there’s so many things that can make people happier. I give an example. In my city we had a dentist. At the end of the week, Friday afternoon, he went to his window. He was good clarinet player, and he played a concert.

The bus stops in Curitiba look like little subway stations. (Photo: Thomas Hobbs; Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

[CLARINET: MICHEL MORAES WITH THE MADEIRA DE VENTO QUINTET.]

LERNER: And people, they knew that every Friday afternoon this guy is giving a concert of clarinet. It’s not about works; it’s about feelings, feeling a city.

[CLARINET CONTINUES PLAYING]

LERNER: Sometimes to make a change in a city takes time. The process of planning takes a lot of time. Sometimes it has to take time, but you can through local interventions, pinpricks, you can start to give a new energy to a city, and you can do it very fast. In my city, when we realized that 75% of carbon emissions are related to the cities, and the half of the problem is the car, we made a big change on public transport. It was said at that time that every city that should approach one million should have a subway. We didn’t have the money for a subway and we started to think “What is really a subway?” It is a system of transport that has to have speed, less stops and good frequency. You shouldn’t wait more than one minute or two minutes. So we started to understand: “Why not on surface?” And in 1974 we started, one line, 50,000 passengers a day.

CURWOOD: That’s a lot of people.

Double-accordion bus at a bus stop in Curitiba, Brazil. (Photo: tortipede; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

LERNER: Yeah and now we are transporting two million and 600,000 passengers per day, and the subway in London, three million people. And the cost: fifty times less per kilometer. We don't have to wait for money; too much money interferes. You can do it immediately and benefit people immediately.

[SOUNDS OF THE SUBWAY IN CURITIBA]

CURWOOD: Today in Curitiba, there are different buses including giant ones that can carry 270 people on the exclusive roadways where cars aren’t allowed. Passengers pay their fares as they enter a tubular shelter so when the bus comes, it doesn’t have to wait while someone fumbles for change. The Curitiba “speedy bus” is celebrated around the world as a model system for cities trying to do more with less to create attractive and rapid public transit. And to face both congestion and climate change, Jaime Lerner says we have to deal with our addiction to the car.

A plaza in Curitiba (Photo: Radamés Manosso; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

LERNER: I wrote a book twenty years ago for teenagers, trying to explain the city, and there was a character Otto, the Automobile. So I wrote: “Otto is a very egotist guy, a guy who comes to a party. And he only transports one or two or three people, and he came to a party, never wants to leave. And he drinks a lot and is sometimes very demanding person because every time more freeways, more freeways.” But the car is become the cigarette of the future.

CURWOOD: The cigarette of the future?

LERNER: Yes, because you know, when it started all over the world to forbid to smoke, nobody expected that reaction. I’m not saying you are not having a car. We still have cars for trips, for leisure, but for daily routine itinerary there’s only one way – public transport.

[BRAZILIAN GUITAR MUSIC; A COMPILATION VIDEO OF SONGS BY LUIZ BONFA]

CURWOOD: What does a city need to do in order to have a rich life, to be environmentally responsible, socially fun, politically functional? What does a city need to do to get it right?

A Curitiba Bus stop. (Photo: whl.travel; Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

LERNER: I think a city has to give opportunity to everything, music, poetry. In my state it’s 399 municipalities. We didn't have money, for instance, for a small city of 4,000 people to have a theater. So what we did, we organized a cultural convoy with 10 buses, recycled buses. One bus was recycled for theater, the other for dance, the other for music, the other for opera, and they travelled all around the state during 5 years. We had an average of 1,500 spectators every night. Or another example, when I was governor we wanted to clean our bays – it’s very costly. What was our solution? It’s a question of co-responsibility. We made an agreement with the fishermen. If the fisherman catches the fish, it belongs to him. If he catches garbage, we buy the garbage. If the day was not good for fishing, they went to catch garbage, and the more garbage they catched, the cleaner the bay become. And the cleaner the bay is, the more fish they have. I’m sure that every city has such smart solutions.

[GUITAR MUSIC: LUIZ BONFA]

CURWOOD: I asked Jaime Lerner to read a passage from his new book.

Jaime Lerner, former mayor of Curitiba and author of the book Urban Acupuncture. (Photo: Daniel Katz)

LERNER: The great city must have a silhouette. The color of the sea seen from the terrace of Amanda’s bar in San Juan, the dignity of Via dei Casaoli in Florence, the hazy mornings of my great Curitiba. I think of the Art Nouveau marquee of a building in Paris, in London, the grace of small scale, in New York, where you always have the feeling that you’re just starting out, an athletic blender of ideas where you’re alone in the company of everyone else. In short, every city should have a personality or a melody that flows, because the city that I think of now will be with me forever.

CURWOOD: Jaime Lerner thank you so much. Your new book is called Urban Acupuncture, Celebrating Pinpricks of Change that Enrich City Life. Thank you so much!

LERNER: Thank you, thank you.

Related link:

Jaime Lerner’s book “Urban Acupuncture” is available here

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTWAY MUSIC: Gene Ammons from “But Beautiful” from The Gene Ammons Story: Gentle Jug (Prestige 1992)]

Building Complete Streets

Harry Mattison and residents of Boston’s Allston neighborhood march at the Rally for a Safer Cambridge Street on July 28, 2014. (Photo: Jake Lucas)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Across the country, in big cities and rural towns alike, many places are making streets friendlier for the people who use them. The policies behind those changes are new, but the problems and complaints they’re addressing are often as old as the roads they aim to fix. That’s the case in Boston, where one particularly troublesome road is getting a makeover. Living on Earth’s Jake Lucas has our report.

[TRAFFIC SOUNDS]

LUCAS: On a bright Tuesday morning, in Boston’s western neighborhood of Allston, a small group of locals with picket signs crowds onto a little wedge of concrete. They’re standing on Cambridge Street, right where a highway on-ramp splits off from the fiercely busy six-lane road that has been a sore point for years.

MATTISON: Cambridge Street is a street that’s a crucial link in our neighborhood, and it’s also an incredibly unsafe, dangerous street.

LUCAS: That’s Harry Mattison, a 31-year-old software developer who’s a longtime advocate for pedestrian and cyclist rights in the area. Since Cambridge Street was last redesigned 50 years ago, it’s been high on the list of residents’ complaints, and with good reason.

Two pedestrians were killed here in the last two years. And one of those accidents happened just a few weeks before this rally, when a car hit a man as he tried to cross from the on-ramp to where the protesters are standing now.

They’re holding signs with messages like “My kids walk here,” and they’re demanding a safer Cambridge Street. Mattison has three kids, and laments not feeling safe on a street that cuts through the heart of his own neighborhood.

MATTISON: I want to be able to walk with my kids, to bike with my kids, to drive safely in the neighborhood where I live, and we just can’t do that today because this street is so poorly designed and so unsafe.

LUCAS: The city is already working on a short-term fix to make Cambridge Street safer. But in the long term, the transportation department has bigger plans. It’s going to bring the street into the modern day and transform it using the principles of what’s called a “complete street.” Complete streets look different in different places, but the idea’s simple - make transportation systems about people, so there’s equal access for all forms of travel and all people.

Boston’s Transportation Department has its own complete street guidelines. The head of policy and planning, Vineet Gupta, says that in Boston, every street redesign will include a handful of features from a menu of possibilities.

The “menu” of different options that could be included in a street redesign in Boston. (Photo: Courtesy of the Boston Transportation Department)

GUPTA: Any street that’s going through a redesign process will have some elements of complete streets in it based on its size, based on what the community wants and based on where it’s located.

LUCAS: In some places that’s as simple as narrowing the road by adding a bike lane. Projects with more room and better funding, like Cambridge Street, might also allow for things like new bike sharing stations, more trees along the street or smart parking meters that direct drivers to open spaces. The final design will be tailored toward the wants and needs of the people who use it. Here’s Vineet Gupta again.

GUPTA: There may be some streets, for example, where wide sidewalks are really important because restaurant owners want to see cafes opening onto those wide sidewalks. That might mean that the bicycle facility is not a cycle track, but just a bicycle lane. There are some streets that see more bus traffic than others, and maybe that’s a street where exclusive bus lanes are most important, at the expense of a bike lane.

LUCAS: Designing streets according to how people use them makes sense, but that marks a major change in the way we think about how we get around. When Cambridge Street was built, highway engineers had one aim in mind. Here’s Stefanie Seskin, the deputy director of the National Complete Streets Coalition.

SESKIN: Post World War II, we embarked in the United States and in many other countries, on a massive infrastructure investment to move goods really across the country. And that had a lot of really important and good changes to the way that we built our roads in terms of safety, when you’re travelling at high speeds, when you’re thinking about trucks and how they move.

LUCAS: But Seskin says while wide lanes make highways and other high-speed roads safer for traffic using them, they were never meant for cities and town centers. And yet city streets were built the same way as those high-speed roads. Vineet Gupta of Boston’s Transportation Department says that post-war engineering mentality explains why Cambridge Street is so bad for pedestrians today.

GUPTA: In those days, all they cared about was moving traffic and making traffic flow more efficient, and really not focusing on what cities really are, and what makes them livable.

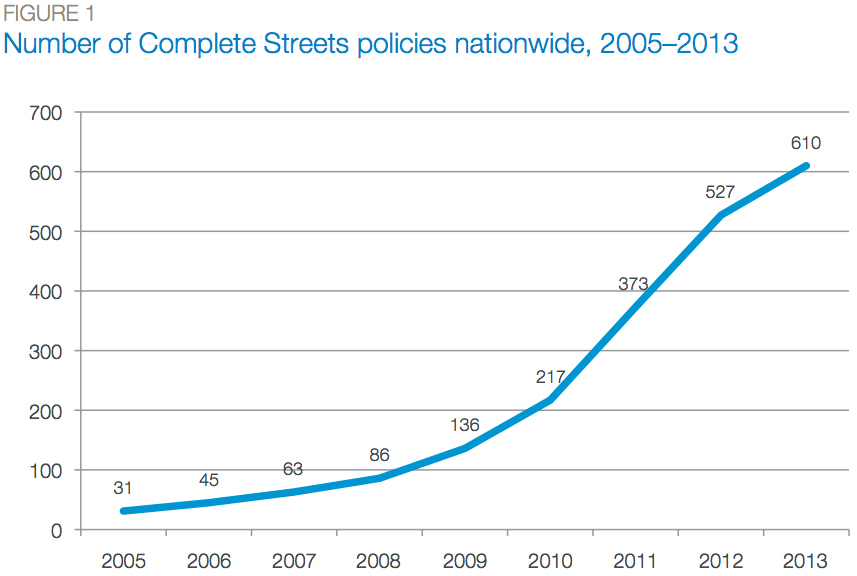

LUCAS: That’s where people-oriented complete streets are different, and the idea has been gaining traction around the country. The National Complete Streets Coalition says that the number of places with complete street policies leaped from 86 in 2008 to 610 last year. Stephanie Seskin has noticed.

The “Complete Street” movement is gaining national traction and the number of complete street policies over the past few years has shot up. (Photo: Courtesy of the National Complete Streets Coalition)

SESKIN: The last five years have definitely been an explosion of interest in this, from all sectors.

LUCAS: And now there’s a federal complete streets policy in the works. The Safe Streets Act is under consideration in both the House and the Senate. The act would require all federally-funded transportation projects to comply with complete street principles that Seskin calls pretty close to ideal. The idea of cites and streets planned around people isn’t new. Vineet Gupta points out that many areas of Boston, like the Rose F. Kennedy Greenway and the North End, are already pedestrian-friendly. But in other cities, Stephanie Seskin says the name “complete streets” has helped those ideas catch on.

SESKIN: The complete streets movement really got a lot of traction because it put a nice name on this more abstract idea that lots of people had for what they wanted in their communities. You know that, “We don’t want to have to drive everywhere. We do want choices, and we want it to be safe. And we want our kids to have the opportunity to ride their bikes in our neighborhood without the parents worrying about it.”

LUCAS: That sounds just like what Harry Mattison and other Allston residents are asking of the city. Their signs demand a street where they can bike and walk safely with their kids. And half a decade after the last redesign of Cambridge Street, the City of Boston is giving them one. Though it may not be until the end of the decade that a complete Cambridge Street is actually completed. For Living on Earth, I’m Jake Lucas in Boston.

Related links:

- Boston Complete Streets—Projects to make Boston transportation multimodal, green and smart

- Rally for a Safer Cambridge Street! Event

- The National Complete Streets Coalition, a program of Smart Growth America

- Smart Growth America’s best complete streets policies of 2013

- Boston taking steps to make Cambridge Street safer ahead of its complete redesign

- The project to redesign Cambridge Street is part of a larger state highway redesign

Canals in Boston?

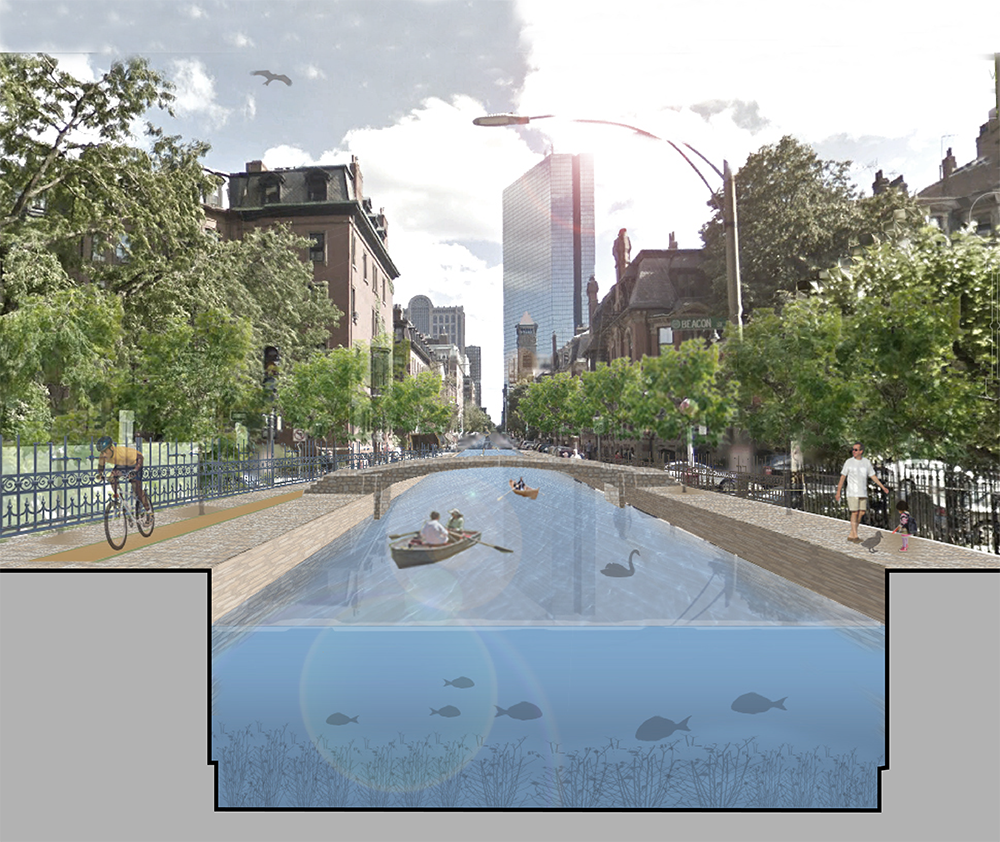

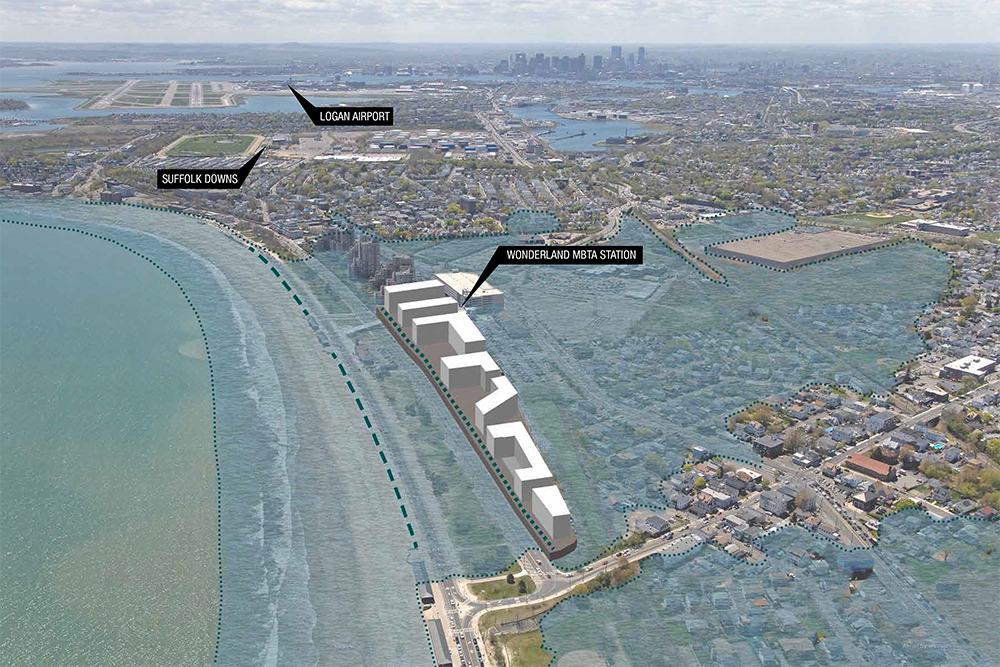

“The Back Bay holds some of Boston’s most valuable real estate. Without changes to current infrastructure the neighborhood is vulnerable to flooding from both Fort Point Channel and the Charles River Dam.” –The Urban Implications of Living with Water report (Photo: Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: Well, Living on Earth is based in Boston and with its historic harbor – think tea – and the curves of the wide Charles River, it’s a tourist destination and an attractive place to live and work. But Boston is also among the most vulnerable cities in the world to sea level rise, so now urban planners in Beantown are looking at ways it can adapt its infrastructure to accommodate rising tides. Dennis Carlberg co-chairs the Sustainability Council at the Urban Land Institute, and we walked along Commonwealth Avenue and talked about an ambitious plan to save Boston's historic Back Bay neighborhood from the sea.

CARLBERG: We’re in, I think, the most beautiful part of the city, especially on a nice sunny day like today. This is Boston’s Back Bay. We’re on Commonwealth Avenue, which is a broad boulevard that runs east and west and it’s absolutely a gorgeous place.

CURWOOD: It’s a beautiful part of the city, but in 1840 it wasn’t here, right?

The John Hancock Tower and the Prudential Center stand amongst Victorian brownstones in Boston’s upscale Back Bay neighborhood. (Photo: Thomas Hawk; Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CARLBERG: Correct. We would be standing in marshland, tidal marsh, where it was mucky and muddy. Over the years we’ve filled in much of Boston, about 30 percent of it is on fill, which by its nature is low-lying, and if we have sea level rise, this area we’re standing in would be flooded.

CURWOOD: So how vulnerable is the city of Boston in particular to sea level rise?

CARLBERG: Boston is quite at risk. It’s considered the 8th most at risk in the world and the World Bank suggests that Boston is the 4th at risk when you look at the property values because so much of it is low-lying, as I mentioned 30 percent of it is on fill. Soon after the end of the century, at the upper end of the projections, 30 percent of the city could be flooded; or in the mid-century with a strong surge, plus sea level rise, we could see 6 to 7 feet of water in our city, which would be flooding 30 percent of our city.

CURWOOD: Now what happened in Boston when Hurricane Sandy came through?

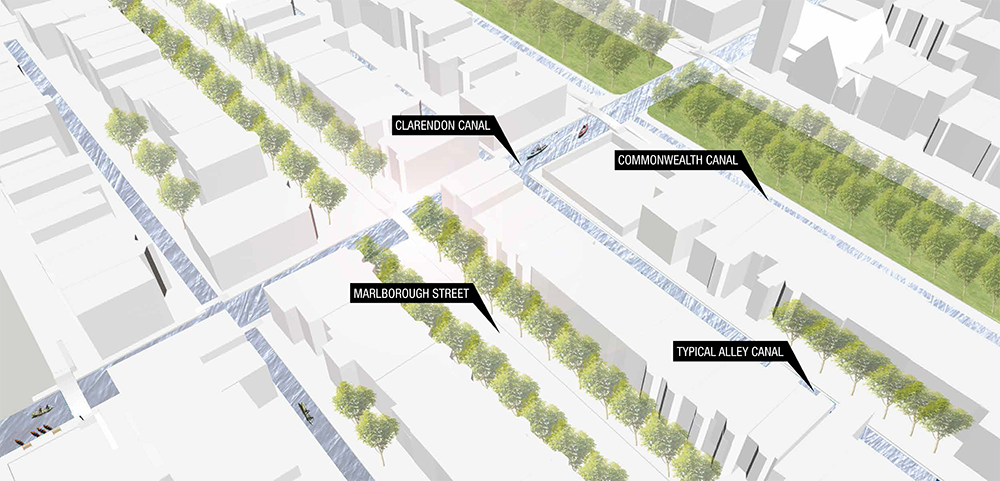

In light of climate change and sea level rise, urban planners at the Urban Land Institute want to incorporate waterways into the infrastructure: alternating north/south streets and east/west alleys would become canals like those in Venice and Amsterdam. (Photo: Urban Land Institute)

CARLBERG: During Hurricane Sandy we had a near miss. Had Hurricane Sandy hit at our high tide, it actually hit just about at our low tide, we would have probably 6 to 7 percent of the city flooded from the storm surge. We’ve had 4 near misses since Sandy, which could have had significant flooding in the city. We’ve been very fortunate so far and I think we can learn from New York. And if we can make infrastructure improvements before the next Sandy hits, that would be a really good scenario.

CURWOOD: So you and your colleagues at the Urban Land Institute, I understand, were tasked with finding a solution to the prospect of this lovely neighborhood, the Back Bay neighborhood in Boston going under water. So what did you come up with?

CARLBERG: Well we took the tack of – well, let’s welcome it in; what does it look like to live with water in an urban environment? So our group came up with a number of ideas and the one that really floated to the top – sorry the pun – was bringing canals into the Back Bay and what would that look like.

This image is a representative view of the quandrangle and shows Fawcett Street as it exists today. The projected flood elevation illustrates the potential impact of climate change on the current street realm and building vulnerability. (Photo: Activitas, Hanaa Rohan, City of Cambridge; Courtesy of Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: Canals in the Back Bay of Boston? You want to turn this into – what Amsterdam? Venice?

CARLBERG: Those are very good references and actually that was part of the conversation. I mean, those are wonderful cities. They’re integrated with water and what would it look to integrate the Back Bay with water.

CURWOOD: How does this work? We think a lot about sea-walls to repel rising tides. Wouldn’t canals just bring more water into the city?

CARLBERG: Well, the water has to go somewhere, so bringing the water into the city in a planned way as opposed to an unplanned way is the strategy we were looking at, and there are sort of two things we need to be concerned about: One is the nearer term, the storm surge and the sea level rise, and one is the longer term, the twice daily high tide. A hundred and twenty years from now, 110 years from now, or a hundred years depending upon how much carbon we put in the atmosphere, we’re going to have a twice daily high tide in the Back Bay. And the other part of that issue is we have a ten-foot tide swing, roughly, in Boston, so what do those canals look like at low tide.

The Back Bay Canal/Street System. The Clarendon Canal shows a typical north/south canal alternating with streets. (Photo: Arlen/Stawasz; Courtesy of the Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: How do you deal with that kind of differential in a tide? If you’ve got ten feet more or less water, either you have very, very deep canals or - what do you do?

CARLBERG: Well, I think you have tide gates. So you let the water in and then you let the water out, so it can circulate but you control it, so that the water level is more stable. It fluctuates some, but it doesn’t do the whole 10-foot fluctuation.

CURWOOD: So here we are on Comm. Ave, these homes are at, well they’re at street level, in fact they have basements. If there’s canals here, what keeps the basements from getting all wet?

CARLERG: Well the big issue is: you’re going to have a lot of water here. And the basements are going to get flooded, and that value is going to disappear. You’re going to lose that space. One concern we had was, if each property is doing its own defenses against sea level rise, we’re going to have a city of walls which is going to kill the value of the city. What makes the city vibrant today is our ability to move in and out of buildings and along our streets, and if we lose that because we have all these walls, what is that going to do? So to get to the question of what happens to that lower level, this is a historic district, but I think we have to think outside the box a little bit. And maybe there’s a zoning that allows for an additional floor or something to take the displaced space. We looked at raising the grade – you’d raise the grade between 4 and 8 feet, to get up higher - maybe not all the way up to first floor because these stoops are really quite beautiful, and then you’d build in the canals to let the water in.

The flood zone based on a FEMA Flood Map for Revere Beach Boulevard (Photo: Arrowstreet; Courtesy of the Urban Land Institute)

CURWOOD: This is right in the heart of the, well, most exclusive part of Boston. I’m thinking, are there actually going to be gondolas and stuff that people can use?

CARLBERG: [LAUGHS] That’s actually what people are talking about. And you know, kayaks and I can’t really quite imagine Venice, but certainly we’re talking about boat transportation as well as bicycle and foot traffic too.

CURWOOD: And then you’re telling me when winter comes you’ll be able to skate?

CARLBERG: That would be great! I'd love to see some skaters on our canals. The challenge is: will it be cold enough to have ice on canals – that’s the real question.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I hear all kinds of expensive construction infrastructure projects required to achieve this. Who’s going to pay for it?

CARLBERG: That is a great question. The Urban Land Institute is now embarking on

an exercise to figure out how mechanisms can be developed to finance this stuff, because this is coming whether we like it or not.

CURWOOD: What sense of the economic loss would we be looking at in the city of Boston if nothing were done to halt the advance of the rising waters?

Commonwealth Avenue in Boston would be the site of one of the canals in the Back Bay (photo: Richard Ricciardi; Flickr CC 2.0)

CARLBERG: Well, that is a critical question. What is the cost of doing nothing, and that against the cost of doing something is really kind of the core of our next effort with the Urban Land Institute. If you look at FEMA, they have a 4 to 1 ratio of investment, before it costs one fourth of the investment after an event. That’s only one metric and I think we really need to dig deep to understand what really is at stake here, as well as what the opportunities are. And I think a fundamental thing the Urban Land Institute was looking at when we were doing this study was: how do we preserve the financial value and the human value in our communities in the face of climate change and sea level rise.

CURWOOD: So what are the odds of this happening? How much are people embracing this and how much are people kind of, you know, laughing behind their hands?

CARLBERG: [LAUGHS] I think what this has done is this has raised awareness and added another option to look at the broad spectrum of strategies to deal with this problem. The city of Boston, I think, understands the concept but whether this really would happen…I think there’s an incredible amount of investment that would have to happen in a broad way. A fundamental challenge we have here is, we have jurisdictional boundaries and we have property line boundaries, and those are all very important boundaries that work very well and have worked very well over time as we’ve developed. But in the face of sea level rise, particularly, water knows no boundaries.

Director of Sustainability at Boston University, Dennis Carlberg draws on a map of Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood. (Photo: Steve Lipofsky)

CURWOOD: The city of Boston’s almost 400 years old. Science says the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere is, at the end of the day, is likely to give us almost 20 meters – that about 60 feet of sea level rise. How do we wrap our heads around what’s coming in terms of sea level rise?

CARLBERG: I think the question is really about our carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. That's the core issue. I think all the ideas we’re talking about here are going to look rather quaint if we don't start reducing our carbon footprint substantially, starting right now. That’s what we have to do; that’s the fundamental challenge here.

CURWOOD: Dennis Carlberg directs Sustainability for Boston University and is co-chair of the Sea Level Rise subcommittee of the Urban Land Institute in Boston. Thanks for coming by Dennis!

CARLBERG: It’s been great; thank you very much for talking about this important issue.

Related links:

- The Urban Implications of Living with Water Report prepared by the Urban Land Institute

- Urban Land Institute

- Dennis Carlberg is an architect, Boston University Sustainability Director and co-chair of the Sustainability Council at the Urban Land Institute.

[MUSIC: John Coltrane “Central Park West” from Giant Steps (Columbia 1959)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, Lauren Hinkel, Jake Lucas, and Jennifer Marquis are all part of our team. Our show was engineered by James Curwood, with help from Noel Flatt. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org and like us please on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth