May 8, 2015

Air Date: May 8, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Atomic Bomb-making Wastes Threaten Missouri Neighborhood

View the page for this story

The toxic waste disaster at Love Canal, New York, sparked the landmark Superfund legislation to clean up poisonous waste sites. Lois Gibbs, a leader in the effort to organize Love Canal residents is now working with families near a landfill site in St. Louis where radioactive leftovers from the atom bomb program in WW2 are buried. The site is associated with elevated rates of rare cancers. A fire in a nearby landfill fire threatens to spread to the radwaste site, and the community is demanding evacuation. Host Steve Curwood discusses the situation Lois Gibbs. (13:30)

Wolf Song on the Rebound

/ Jennifer JerrettView the page for this story

For years, wolves were missing from Yellowstone National Park, leaving an eerie silence in the air. But now that the wolf population is recovering, the Park’s acoustic landscape is reviving. Reporter-in-Residence Jennifer Jerrett’s audio postcard brings us a harmonious chorus of howling wolves. (02:25)

What A Howling Wolf Howl Says

/ Jennifer JerrettView the page for this story

When a wolf howls in Yellowstone’s snowy landscape, a howling chorus responds. But in the spring, the wolves grow quieter as they raise pups. Now researchers understand how wolf calls change with the seasons, and hope to answer the tougher question of what the howls actually mean. The park’s reporter-in-residence, Jennifer Jerrett, has the story. (06:25)

Wolves on the Brink

View the page for this story

The predator-prey relationship is an ancient tale, and in Isle Royale National Park, on an island far from shore in Lake Superior, scientists have watched wolves hunt moose for over five decades, in the longest such study in the world. But as Michigan Technological University ecologist, Rolf Peterson, the study leader tells host Steve Curwood, the predator population is now tiny, jeopardizing the study. (06:35)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about three instances when poor federal spending decisions have led to expensive environmental problems and lengthy cleanup projects. (04:15)

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

Checking Up on Native Plants

View the page for this story

Spring is the season for the first wild flowers to appear, and despite this year’s severe winter, native wild flowers are starting to bloom at the New England Wild Flower Society’s Garden in the Woods. But climate change, aggressive invasive species and insects are stressing some iconic plants, so a group of experts produced a report on the state of New England’s plants. Host Steve Curwood a takes a walk in the woods with the Wild Flower Society’s senior research ecologist Elizabeth Farnsworth to find out what’s going on. (13:25)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Lois Gibbs, Rolf Peterson, Elizabeth Farnsworth

REPORTERS: Jennifer Jerrett, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: Tracking a superfund site in Greater St. Louis where local people are desperately want to get relocated, because of environmental hazards and worsening health problems.

GIBBS: It’s very frustrating because this is worse than Love Canal, it's worse than any site I've been, and it's because it’s radioactive waste, it’s a garbage landfill, it’s a fire, and that's just terrifying.

CURWOOD: Who’s trying to help. Also, wolf researchers are working to figure out why wolves howl, and what they might be saying.

SMITH: When you sit and you listen to that lone wolf howl, almost moaning, it just doesn’t sound, it sounds so emotional, and we’re trying to really figure out what does that wolf howl really mean.

CURWOOD: We’ll have howling wolves and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Atomic Bomb-making Wastes Threaten Missouri Neighborhood

Protest sign in the area around the West Lake landfill in St. Louis (Photo: Center for Health, Environment and Justice)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. In suburban St Louis, people are waking up to a toxic waste catastrophe, and the trouble is treble. First, murky records indicate that the West Lake Landfill in the small City of Bridgeton, Missouri is loaded with high-level radioactive waste, possibly including decay products from weapons grade uranium. A Washington University report says the rad-waste has migrated into groundwater linked to the floodplain of the Missouri River. Second, a neighboring waste dump in Bridgeton is on fire underground, about 1000 feet from the West Lake site’s underground radioactive plume. And third, in this area the rates of rare childhood cancers are high. Lois Gibbs, the environmental activist who famously organized parents to protect the health of families at Love Canal, is working with St Louis families who live near the waste sites, and she joins us now to discuss the situation. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

GIBBS: Thank you. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So first of all how did radioactive waste wind up at the Westlake landfill there in St. Louis?

GIBBS: It ended up there because it's part of the Manhattan Project. St. Louis was big in doing the Manhattan Project many, many years ago, and so the waste was deposited all around the St. Louis area and then they started to clean it up; when they cleaned it up they put it in the Westlake landfill not realizing that it was as much of a danger as it has now become.

A family living near the West Lake Landfill (Photo: Center for Health, Environment and Justice)

CURWOOD: How did the government go through the process of approving the dumping of this waste in the Westlake neighborhood there?

GIBBS: Well, that's a real good question. Nobody seems to be able answer to that. They were supposed to clean up the radioactive waste from different parts throughout the region there - Bridgeton, Westlake - and what they ended up doing was putting it in this dumpsite. They believed that it was low-level waste so they didn't have to worry about it but as it turns out it was very high-level waste. And it's an unlined landfill, which used to be a quarry so when you think about quarries, just think about how deep they are. It was disposed of in there and then covered up and essentially sold to Republic Services afterwards.

CURWOOD: So we're talking about uranium? What kind of stuff is there?

GIBBS: Uranium is definitely there, it's very high-level radioactive material, the stuff that people keep talking about wanting to put in Yucca Mountain or another secure location far, far away from both groundwater and human health. And it's very, very, very, very dangerous.

CURWOOD: Which government body did this originally and who's responsible for it now in your view?

GIBBS: Right now it's the responsibility of the federal government. The Environmental Protection Agency actually took the two landfills and declared them one Superfund site. They're trying to figure out what to do with this waste. The local community is asking him to dig it up and take it out into a secure place. EPA is saying no, maybe we can just leave it on site, but it's so hazardous.

The other thing that's really interesting about this case that makes it I think especially dangerous is next to the Westlake landfill where all the radioactive material is very high-level radioactive material is a garbage dump. This is the Bridgeton site. And this too was once a quarry, so it's quite deep, and this quarry has caught on fire and has been burning for four years. The scary part is that the fire is moving towards the neck of the radioactive material in Westlake. I mean, literally, these two dumpsites are only 1,000 feet apart. When fire reaches the radioactive site, no one knows what is going to happen. It's just so frightening and around the community is people - moms and dads and families and dogs and cats and schools and they're all panicked.

A child who lives near the West Lake landfill. Researches found an increased rate of brain cancer in the area around the landfill, and residents say their children have experienced hair-loss and respiratory problems, which they think are caused by the nuclear waste and/or the landfill fire. (Photo: Center for Health, Environment and Justice)

CURWOOD: So the fire sounds like it's a ticking time bomb there. What have you been told could happen if the fire does reach the radioactive waste?

GIBBS: If the fire reaches the radioactive dump there will be ‘an event.’ Now the emergency services guys came out to the community and told them if there is an event what you need to do is shelter in place. All the families need to shelter in place and you need to shelter in place for probably a week because what we need to do is go around with a testing equipment like a Geiger counter and we have to test every car, every swing set, every backyard, every front yard, and so you cannot exit your home until after we done that testing. A funny story is when one gentleman stood up when an emergency guy was telling the story and said, "What am I supposed to do with my dog, train him with kitty litter? I have to take my dog out." You're gonna have to shelter in place for two weeks until we test every single piece of property to know whether or not it's radioactive to a level that's unhealthy? That's insane.

CURWOOD: So what's being done to prevent that from happening? What's being done to stop that fire from reaching the radioactive material.

GIBBS: So they're talking about putting a barrier between the two dumps, sort of a barrier wall if you will. But the problem with that is that's two years down the line and before they even get this study out and the proposal and then of course it has to go to public comment. The fire could reach there much faster, it just depends on how much oxygen gets into the dirt and some people are saying that if they dig that ditch to put that wall there it could introduce oxygen to the site and the oxygen will cause it to move quicker over to the radioactive site and then we don't know what's going to happen, ‘an event’ will happen.

CURWOOD: Now, how has the contamination there affected people's health? What’s the public health situation around this radioactive material?

Smoke from the Bridgeton landfill fire. (Photo: Center for Health, Environment and Justice)

GIBBS: Well, there's been a number of studies and what they're finding in the studies is that there is a 300 percent increase in the last few years of brain cancer in young children and this is really frightening. We have a number of the leaders of the local community whose children have died from brain cancer, immune system problems, leukemia, I mean, it just goes on and on and on. And these are not wealthy people. These are community people who are a working class community, they don't have a lot of money, they're trapped in their houses and they're just watching their children get sicker and sicker.

CURWOOD: How sure are they that the cancers are being caused by the radioactivity, do you think?

GIBBS: Well like most studies they're saying that there is a cluster there. They believe it is related to the radioactivity and or the smoke but nobody ever puts one and one together. We've been through this before with Woburn, Massachusetts, Love Canal and the other sites but you know there is a cluster and the only thing these folks have in common is the radioactive material and the smoke from the burning landfill.

CURWOOD: The smell from the burning landfill so I guess, well, doesn't smell very nice. You've been there. What does it smell like?

GIBBS: It smells like rotten eggs. There was a journalist who was there a couple weeks ago when the cover of the burning landfill - they have like a canvas cover on top of it - when it ripped open because it was pillowing up and he just took one whiff and started vomiting on the side of the road. This is what people have to live with every single day. The attorney general has filed notices of violation almost every quarter. It's above standards, air standards, and people are living with this every single day and they literally cannot go outside.

One of the moms tells an interesting story it’s that when she puts her children outside she puts a timer on her oven for 15 minutes and when the timer pings she goes out to smell the air to make sure that is not full of smoke and chemicals because you can actually smell the stuff. You can't smell the radon, you can't smell the radioactive material, of course, but you can certainly smell the smoke and the toxics that are burning next door, and so she'll go out, smell the air and if it doesn't smell too bad then she'll go back in the house and set the timer for 15 minutes again and keep on checking. This is how people have to live there because it's radioactive material and it's smoke and it's toxic and is going literally into their homes into their yards and there's no escape.

Radiation detectors used at the West Lake landfill. (Photo: US EPA Region 7)

CURWOOD: It sounds like a nightmare.

GIBBS: It is a nightmare and you know the federal government is responsible because it's a Superfund site. They've mismanaged the site for years. There's nobody paying attention to this, nobody dealing with this, and the community is so frustrated that they been picketing EPA, they been writing letters, they've gotten their Senator MacCastle and their Senator Blunt to do a letter to EPA and we still haven't gotten any action. There's nobody there who knows about this site, nobody there who’s taking care of the site and Gina McCarthy the administrator just refuses to meet with us and what the community is looking for is the evacuation of their families. They really need to get out and Gina McCarthy does have the authority under Superfund to evacuate the community.

CURWOOD: Now when you confronted the government about the situation at Love Canal one of the things that happened down the road was the creation of the whole Superfund process, the designation of sites and such. How do you feel that Superfund doesn't seem to be working to help these people?

GIBBS: No, it doesn't. I'm not sure if Superfund...Superfund has a provision in it that says if you can't stop exposure in a timely manner then you can move the people. So they have authorization to do that and we made sure that was in there when we put Superfund together years ago. I don't understand why there is resistance to doing this; I've been involved in 16 relocations across the country - Pensacola Florida and Times Beach and so forth - and I don't understand it because the state is supporting relocation, the state is supporting doing something by EPA. It's EPA who's holding strong and it just doesn't make any sense. But I don't think it’s Superfund, I think it's the administration of Superfund that's creating the problem.

CURWOOD: Lois, what about the company that owns this, Republic Services Incorporated? I understand they bought it from Browning-Ferris Industries but it's theirs now. How are they responding and how are you reaching out to them.

Contractors scanned for radiation at the West Lake site. (Photo: U.S. EPA Region 7)

GIBBS: Well, one of the things we're doing with them is that we're going after Bill Gates. Bill Gates is a significant shareholder of Republic Services. Republic Services is saying we're not responsible. We didn't know when we bought it. But Bill Gates really cares about health and children's health. He just divested from McDonald's, for example, to keep children healthy, so we are asking him to use his position as a shareholder to really ask them to evacuate these people.

CURWOOD: Republic Services says well, they didn't know, they didn't have anything to do with this. but the Superfund law says, hey, if you own it you have to own all the problems of the past.

GIBBS: That's right. They should've done due diligence. My understanding is they just bought BFI, and as a result of that they took the good and the bad, but you're because they didn't know doesn't make them innocent.

CURWOOD: That how the Superfund law works, right?

GIBBS: That's how the Superfund law works, that Superfund says you are joint and severally responsible, meaning that the Republic services is responsible for Westlake and Bridgeton they are responsible not only for the remedy of cleanup but they're also responsible to care for the human health and the environment around that site and do it right, using the St. Louis Corps of Engineers to take that radioactive waste out of that site and put it in a secure location somewhere.

Residents march to put pressure on the EPA and the company who owns the site, of which Bill Gates is a shareholder, to evacuate the residents. (Photo: Center for Health, Environment, and Justice)

CURWOOD: Lois, before you leave, what do you hope happens with this situation? What are your aspirations for these people?

GIBBS: What I'm hoping will happen is that EPA would agree to evacuate all those who wish to leave within that two mile radius and would agree to dig up that high-level radioactive waste and put it in a safe place not in the middle of the community and do something about the fire. They can't put it out but there must be another way to stop the air pollution that is coming from it. But it's very frustrating because this is worse than Love Canal, it's worse than any site I've been and its because it's radioactive waste, it's a garbage landfill, it's a fire and that's just terrifying - it's absolutely terrifying and I just, my heart goes out to these folks and I spend more time on this site than any other ones because of the situation.

CURWOOD: Lois Gibbs is Executive Director of the Center for Health, Environment and Justice. Thanks so much for taking the time today.

GIBBS: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: We contacted the EPA and Republic Services for comment. A spokesman for Republic Services told us there are no health risks to the community from the two sites, the company does not believe the radioactive waste will catch fire and the EPA is in charge. The EPA statement reads in part:

“The conditions at the site currently do not present the kind of threat to human health that would require relocation of nearby residents. This agency will continue working toward a final remedy to ensure that the site remains that way.”

The full statements and more information are on our website LOE.org.

Just Moms St. Louis is a non-profit activism group against the radioactive Superfund site left over from the Manhattan Project in their Community. (Photo: Center for Health, Environment and Justice)

Comments from Republic Services, the owner of the West Lake site:

1. What are the health risks from the contamination at West Lake to people in the surrounding community?

None. And, that is after 30-plus years with no remedy. Please check with the EPA. They have been consistent on this for years.

2. What if anything is Republic Services doing to mitigate those risks or evacuate vulnerable residents?

The site, along with the adjacent Bridgeton Landfill, is arguably one of the most closely monitored sites in the country. The EPA has authority over West Lake. At Bridgeton, which is a site we also acquired in 2008 as part of a much larger transaction, the Landfill has invested in highly sophisticated systems and operations to control odor and manage a subsurface reaction. It is among the most advanced civil engineering projects recently completed in the State, and the work was paid for by the Landfill.

3. How concerned is Republic about the fire at the Bridgeton site, and what are they doing to prevent the fire from reaching the West Lake contamination?

We do not believe it will happen. The subsurface reaction continues to be isolated to one portion of the South Quarry. It would have to reverse direction, defy a few laws of physics by climbing up and moving several hundred feet in the opposite direction, then pass through an area of soil where there is no trash (fuel for the reaction), and still keep going before it reached the radiologically impacted materials in the adjacent West Lake Landfill. The EPA has been clear that, at most, this would result in a release of radon, which safely, quickly and naturally dissipates in air.

4. Who does Republic Services feel should be responsible for the contamination?

I would characterize it as drive-by reporting. Al Jazeera ignored wider concerns associated with the notion of excavation and transportation held by community leaders in St. Louis and citizens throughout the central and western portions of the State.

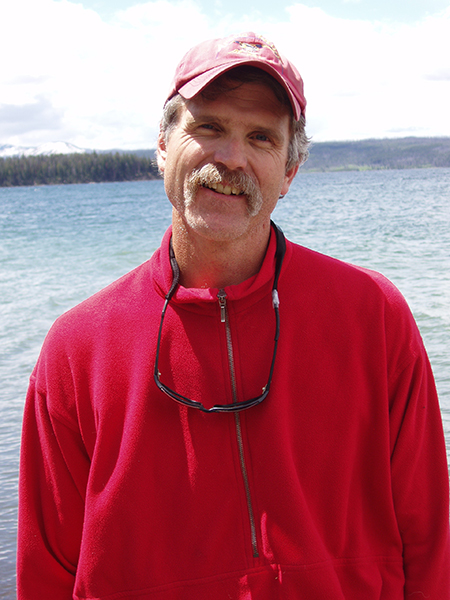

Activist Lois Gibbs (Photo: yoopernewsman, Wikimedia CC BY 3.0)

Full Statement from EPA:

EPA Region 7 is committed to ensuring the public is protected from the radioactive contaminants at the West Lake Landfill Superfund Site. EPA bases its decisions on valid, scientific data, which this agency shares with the community. Based on the body of evidence available EPA Region 7 has concluded that the conditions at the site currently do not present the kind of threat to human health that would require relocation of nearby residents. This agency will continue working toward a final remedy to ensure that the site remains that way.

EPA Region 7 is leading a comprehensive multi-agency effort, including the U.S. Corps of Engineers, and the U.S. Geological Survey, to establish a final remedy for the site. EPA is also supporting the Missouri Department of Natural Resources’ and Missouri Attorney General’s work to protect public health from the subsurface smoldering event in the adjacent Bridgeton Landfill.

Related links:

- Read more about the situation at the West Lake landfill in Al Jazeera

- More about the radioactive West Lake landfill

- Center for Health, Environment, and Justice

[MUSIC: R.E.M. Wolves Lower, Chrinuc Town, IRS Records, 1982]

CURWOOD: Coming up...trying to find out what wolves are saying when they howl. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: medeski, scholifels, martin and wood, North London, Juice, Indirecto Records, 2014]

Wolf Song on the Rebound

A pack of gray wolves howling in their habitat (Photo: F.Svehla, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. A while back Jennifer Jerrett, reporter-in-residence at Yellowstone National Park, sent us this evocative audio postcard.

MCINTYRE: I’m Rick McIntyre. I work for the park service in Yellowstone National Park, and my title is Biological Technician.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

The beautiful howling is a reflection of his beautiful pose (Photo: Retron, Wikimedia Commons)

MCINTYRE: One of things that I often think about when we hear wolves howling is...I’m sure you know the story...that it was the last of the original Yellowstone wolves that were killed in 1926 about a half a mile from where we’re standing. And so for any visitor that had come to Yellowstone from 1926 to 1995 when wolves were brought back and re-introduced and re-established...I’m sure they had a great experience visiting the world’s first national park and would have seen a lot of great stuff, but there’s one thing they missed out on. There would have been an unnatural silence here. But luckily we realized what a big mistake that was and figured out how to rectify it. So we’re experiencing that right now. That silence is over.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

CURWOOD: That's biologist Rick McIntyre...and friends. Reporter Jennifer Jerrett brought us that audio postcard from Yellowstone National Park.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

Related link:

How Wolves Change Rivers

What A Howling Wolf Howl Says

A wolf from Yellowstone's Druid Pack mid-howl (Photo: NPS Photo)

CURWOOD: Well, Jennifer Jerrett is still following the wolves of Yellowstone, and she says that they literally change their tune come spring. And there’s new research on the nature and meaning of how and what the wolves are communicating. Here’s her story.

JERRETT: There is nothing like springtime in Yellowstone. After the long, snowy, hush of winter, the spring season around here seems to erupt in layers and layers of sound.

[SPRING BIRDSONG

JERRETT: But unlike most of the other animals in the park, wolves tend to become a little quieter in the spring.

[BIRDS; WOLVES HOWLING]

JERRETT: Researchers in the park recently discovered that there is a seasonal cycle to those howls.

[HOWLING FADES]

JERRETT: Biologist Doug Smith is the project leader for all of the wolf research that takes place in Yellowstone National Park. He says that if you’re a wolf in Yellowstone, you still howl in the spring…

SMITH: … but you howl less, you only howl when you need to and you’re only howling to your pack mates. As the summer grows old, you start howling more and more and so now you start howling to your neighbors, your enemies, and it increases through the fall and winter. That’s the seasonal cycle.

Wolf pups in spring (Photo: NPS Photo)

JERRETT: The seasonal cycle peaks in February which tracks right along with the breeding season in Yellowstone. And there’s a lot of howling back and forth between neighboring or rival wolf packs.

SMITH: Wolves are ferociously territorial, and so they howl to others to say ‘Hey I’m here, stay out.’

JERRETT: But in the spring, when wolves start establishing den sites to raise pups, everything changes.

SMITH: So what appears to be happening during the denning season is that howling for territorial purposes goes away. You stop communicating to your neighbors. So what we’ve noticed--what doesn’t go away--is howling to your pack mates, to your family members.

JERRETT: So while there’s less howling overall in the spring and summer, the call-and-response that does go on is almost entirely within pack. Doug has been studying wolves for 35 years. He explains what might be happening.

SMITH: In the winter the pack’s all together and they travel widely, they go everywhere. When they have those pups, wham! An anchor gets thrown in, they become your ball and chain. And wolves need to carry out their business, but they also need to care for their pups. So they leave the pups at the den and they split up. Well that presents a problem of how you coordinate activities, how do you communicate, how do you find each other. Well, you howl.

[WOLVES HOWLING]

SMITH: So what’s so important about that story is that was a previously unknown story. Now enter Yellowstone.

JERRETT: The only way that the research team working in Yellowstone was able to tease apart this seasonality – more howling that tends to be territorial in the fall & winter, less howling that’s more family-focused during spring & summer -- is because when it comes to wolf research, Yellowstone’s landscape is unique. There’s a lot of open country in the park. So you can see the wolves – see what they do when they howl and this is what provides the context for understanding howling.

You never forget your first wolf in the wild. (Photo: NPS Photo)

SMITH: Through this breakthrough of being able to see and hear and determine the context --

that’s how John and Mary Theberge -- that’s the couple that’s doing this research – and they were able to quantify this is a howl for the away game and this is a howl for the home game. And that has been leaps and bounds of progress in terms of understanding why wolves howl.

JERRETT: To dig in to a scientific answer, I called John Theberge at his home, way up in the mountains of British Colombia. I talked with him about this aspect of his work in Yellowstone that is just getting underway: What do the howls mean?

THEBERGE: And that’s the really slippery slope. (laughs) It’s a complex topic because wolves are complex. The theories of animal communication are complex. The mind of the wolf is complex and one of the most perplexing things is that however we try to interpret another animal’s behavior we do so through our minds

JERRETT: Which makes it tricky—even for researchers—to figure out whether there’s any real meaning or intention behind different howls.

SMITH: When you sit and you listen to that lone wolf howl, almost moaning, it just doesn’t sound, …it seems to mean so much more to the individual wolf: You know, this animal is sad, it’s lonely. And we’re trying to really figure out what does that wolf howl really mean.

[MOURNFUL WOLF HOWLING]

JERRETT: Even if we don’t yet know what it means, the call of the wolf is an iconic and unforgettable sound that can send chills up the spine. There’s a saying around Yellowstone that you never forget your first wolf in the wild and that’s certainly true for Doug Smith.

Doug Smith is a wolf biologist and the project leader for wolf restoration program in Yellowstone National Park. (Photo: NPS Photo)

SMITH: The first time in the wild I heard a wolf howl was on Isle Royal. It was the middle of the night, I was standing outside the tent in my underpants - the bugs weren’t too bad - and the moon was shining. Then way off in the darkness of the night a wolf howled.

[DISTANT WOLF HOWL]

It came from oh gee a mile or two out, and right at the end when I swear, it came in so close I could hear the sticks snapping, the howls were booming in -- it was like in the palm of your hands -- and that wolf never stepped in to the light of the moon and I never saw it.

[WOLF HOWLS NEARBY]

That was nature at its best.

JERRETT: There are a lot of people like Doug in this park. People come from all over the world to see and hear wild wolves in Yellowstone. And this latest research into wolf ecology, communication, and behavior, offers an opportunity to move further, beyond seeing and hearing, to take another tiny step closer toward understanding the mind of the wolf.

For Living on Earth, I’m Jennifer Jerrett in Yellowstone National Park.

CURWOOD: Jennifer’s story was made in conjunction with the Montana State University Library’s Acoustic Atlas project. Thanks also to the Yellowstone Association and the Yellowstone Park Foundation.

Related links:

- More on the wolves in Yellowstone via National Park Services

- Montana State University Library's Acoustic Atlas

- Yellowstone Association

- The Yellowstone Park Foundation

Wolves on the Brink

At its heyday, the Isle Royale wolf population had as many as 50 wolves. The current population has just three individuals and is virtually guaranteed to die out, barring human intervention. (Photo: L. David Mech/USFWS, Wikimedia CC)

CURWOOD: Now Doug Smith was telling Jennifer that his first close encounter with a wolf was on Isle Royale, an isolated island in Lake Superior, where wolves have been closely studied. Indeed, scientists have followed the wolves and the moose they prey on at Isle Royale National Park for over five decades, the longest study of its kind in the world. But now the study is threatened by the dwindling number of predators, and the wolves could be gone as early as next year. One of the study leaders, Rolf Peterson, is an ecologist at Michigan Technological University, and he joins us to explain what is happening. Welcome back to Living on Earth!

PETERSON: Thank you.

CURWOOD: Isle Royale is an island, so how do wolves and moose get there?

PETERSON: The present moose population became established over 100 years ago, probably by an individual swimming from the mainland 15 to 20 miles away. Lake Superior is so cold that only a very large animal like a moose could survive the cold water. Wolves came about 50 years later, in probably the late 1940s and they would've come across the ice in the winter.

CURWOOD: Now, Rolf, you been observing this interaction between the wolf and the moose for decades now. What did the wolf-moose relationship look like back when the project started?

The wolves of Isle Royale first arrived on the Lake Superior island in the late 1940s by crossing an ice bridge. (Photo: Glenn Research Center, Wikimedia CC)

PETERSON: Well in 1958 when the project began, no one had any idea what was going happen at Isle Royale. Some people thought quite seriously that the wolves would kill off all the moose and then start in on people, and what initially seemed to be the case was that there was some sort of static balance between wolves and moose. But after 15 years or more it's quite clear that the wolf-moose system, the predator-prey relationship, is very dynamic and these populations are in motion all the time. Actually now we realize that the whole system is driven by fairly rare events that are relatively unpredictable, for example, new genetic renewal.

CURWOOD: A wolf makes it over from the mainland and changes the genetic pool?

PETERSON: Yeah, a wolf wanders over from mainland and becomes a breeding individual on the island and we have one very good example of that that began in 1997. His genes quickly went through the whole population and fundamentally changed the wolf-moose vegetation dynamics. The wolf population was rejuvenated rather spectacularly and then amazingly the wolves killed moose at a higher rate than we've ever seen before, and they were just better at preying on moose. And that led to an extended number of years when moose were at a low level and that resulted in a major release of vegetation that the moose typically eat. So it was a three-level response.

Moose arrived on Isle Royale much earlier than the island’s wolf population, probably by swimming. Unlike wolves, moose are big enough to survive Lake Superior’s frigid temperatures. (Photo: Ray Dumas, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, what other factors can change that balance between the wolf and the moose.

PETERSON: Well, we've seen certainly that new disease in the wolf fundamentally changes everything. In 1981, a mutant virus called Canine Parvovirus got to Isle Royale and the wolf population crashed and then the immigrant in 1997 resolved that. You sort have to look at the system as a historian would look at it and realize it's just one big event after another.

CURWOOD: But how did you track this predator-prey interaction over the years and its effects on the rest of the Isle Royale ecosystem?

Isle Royale is over 45 miles in length and 9 miles wide– making it the largest island in the largest freshwater lake (Lake Superior) in the world. (Photo: Ray Dumas, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

PETERSON: Each winter since 1959 there's been a small airplane at Isle Royale for up to seven weeks and all the wolves are counted. The moose are sampled and censused counting about 15 to 20 percent of the island. That gives us basically moose-wolf numbers every year. Vegetation has been a harder thing to track. Actually we've had some luck tracking back in time looking at tree rings. And wolves, although they feed primarily on moose, there's a secondary prey species, the beaver, and the beavers are a great animal engineer who totally renovates habitats by flooding them and creating lakes so as wolves prey on beaver, so goes the beaver activities.

CURWOOD: Now, tell me, today about how many moose and how many wolves are on the island and what does the interaction look like right now?

PETERSON: Well, in 2015 we just wrapped up our studies a few weeks ago and there were three wolves, which is the lowest we've ever seen it and the moose are increasing pretty quickly. They stand at 1,250 animals right now and have doubled in the last four years.

CURWOOD: And what's been the high of the wolf population there?

PETERSON: Oh, we've had as many as 50 wolves in 1980 and the average is 20 to 30, roughly two dozen wolves.

CURWOOD: So why are there so few wolves there?

Aided by reintroduction programs and changing public attitudes, wolves are making a comeback in the rural American West. On Isle Royale, however, they’re in a steep decline and unlikely to recover. Warmer winters mean that ice bridges rarely form between the island and the mainland, so a new pack of wolves is unlikely to colonize Isle Royale unless transplanted by humans. (Photo: Caninest, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

PETERSON: That's a product of close inbreeding. After the arrival of this new wolf in 1997 while things were really good for a while, eventually his genes were so successful that everybody was finally a descendent of his.

CURWOOD: So how does the current population show its inbreeding?

PETERSON: The most obvious sign of inbreeding is the fact that they have spinal abnormalities. That means extra vertebrae or asymmetrical vertebrae. It started off low, a few percentage in 1994 that has risen to the point were 100 percent of the wolves had spinal abnormalities.

CURWOOD: With a warmer world, less often there's an ice bridge, so less often as a chance for some fresh wolf DNA to make it on an ice bridge over there. How accurate is that picture do you think?

PETERSON: That's pretty accurate. Back in the ’60s, when observations were first being made of wolves and moose, ice would be the typical situation in winter. You'd have an ice bridge four years out of five. Now it's more like one year out of 10.

The wolf population on Isle Royale is in a death spiral – the result of what geneticists call inbreeding depression. In order to survive, small populations depend upon the arrival of new breeding individuals that introduce new genes into the population. (Photo: Viewminder, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, at just three wolves, how sustainable is this population, do you think?

PETERSON: Well, given the genetic makeup of the current three that are left, I wouldn't give it a chance at all of survival. Without new genetic material, I'd say it's a doomed population. I'd recommended the last four years to do a genetic rescue, in other words, drop a couple wolves off from the mainland that would breed with the resident wolves. That should lead to a masking of deleterious or ‘bad’ genes, we could call them. At this point now in 2015 with only three wolves left the opportunities to do a genetic rescue are mostly gone.

CURWOOD: So what's the future of this longest predator-prey study in the world right now?

PETERSON: Well, the predator-prey study could become just a prey study and that loses a lot of its significance.

CURWOOD: Rolf Peterson is an Ecologist at Michigan Technological University and one of the wolf-moose project leaders at Isle Royal. Thank you so much, Rolf.

PETERSON: Thanks, Steve, it's been great to talk with you again.

Related links:

- About the Wolves & Moose of Isle Royale Project

- Understanding Inbreeding Depression

- Opinion: Save the Wolves of Isle Royale National Park

[MUSIC: Lambchop, A Day without Glasses, Damaged, Merge, 2006]

CURWOOD: Coming up...heading out to the woods in search of nature’s spontaneous display of spring flowers. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems, provides building technologies and supplies, container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTWAY MUSIC: Doug Martsch, Instrumental, Now You Know, Warner Bros, 2001]

Beyond the Headlines

The Hanford Site, which produced plutonium for the Manhattan Project and throughout the Cold War, is now the focus of one of the largest environmental cleanup projects in the U.S. The site contains over 130 million cubic yards of contaminated soil and debris. (Photo: EcologyWA, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. Time to check on the world beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. He's on the line now from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter, what have you found?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, you know, I’ve been working up a righteous anger about the environment and taxes. So let’s embark on the first of three stops where bad money decisions have led to bad policy.

CURWOOD: Okay, who’s on first?

DYKSTRA: The Department of Energy’s Hanford Site, where Cold War pressures built a mess and a money hole in the high desert of Washington State. At Hanford and other nuclear weapons production sites, armies of factory workers churned out nuclear bombs and their components, and a whole lot of toxic and radioactive waste, for decades, with oversight of the waste problems pretty much an afterthought. As the Cold War wound down in the ’80s and ’90s, Americans woke up to a huge environmental mess.

CURWOOD: And the cities and towns that built up around it were looking at, well, shall we say, an uncertain future.

DYKSTRA: Or so they thought. But for the three small cities near the Hanford plant – one of the biggest concentrations of Ph.D.’s in America by the way – the business of building the bomb turned into the even bigger business of cleaning up after the bomb. The cleanup tab for the Hanford site runs into the billions of dollars every year, and the conventional wisdom is that the cleanup wouldn’t wrap up for another fifty years from now. But officials from DOE and from the State of Washington say they’re about 25 years behind schedule on the cleanup, and over time, the price tag may balloon by tens of billions of dollars more.

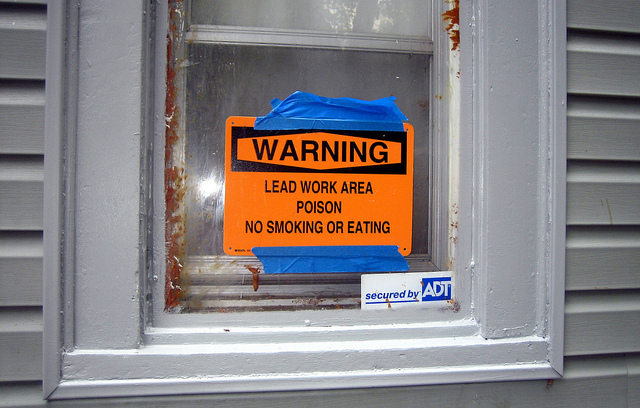

Lead-based paint in old homes is a common source of lead poisoning in kids. Funding for lead cleanup programs was recently cut, even as the Centers for Disease Control tightened standards for lead levels in kids. (Photo: Clint JCL, Flickr CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Whoa, that’s some serious coins – it’s like the Cold War has a hundred-year, adjustable rate mortgage that’s going up.

DYKSTRA: Indeed. And let’s move on to some smart government spending that’s been largely abandoned: In the aftermath of the unrest in Baltimore and other cities a few weeks ago, there was a focus on the role of deep cuts in Federal funding to help fix longstanding lead poisoning issues that impact inner city kids. Over the past few years, federal grants to local governments for lead poisoning work have largely dried up, and cash-strapped cities are in no shape to fill the breach. In Chicago, for example, spending on programs to remove old lead paint from homes and other risks, has been cut in half, even as blood-lead levels are still rising in some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods.

CURWOOD: Yeah, we’ve reported on the links between lead poisoning and violence among young people before, so this sounds like a squandered opportunity for environmental justice.

DYKSTRA: And it’s being repeated in cities across the U.S. Detroit has had a widely praised lead poisoning program that’s under threat as well. The strange irony here is that while the bean counters in Congress were cutting funding for lead poisoning, the Centers for Disease Control had tightened standards for lead levels in kids.

CURWOOD: Hmm, so that makes strike two. Where are we going on the magical history tour this week?

The General Mining Law of 1872 set the price-per-acre for hard rock mining at five dollars. One hundred forty-three years later, the price still hasn’t been raised. (Photo: GaryColet, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Back to 1872, when Men were Men and western land was there for taking.

CURWOOD: You mean taking it from Native Americans.

DYKSTRA: And giving much of it away again on the cheap, so that makes for an environmental funding trifecta. One hundred forty-three years ago this week, the General Mining Law of 1872 decreed that mineral rights on federal land would be given away for a price-per-acre that’ll get you a large bag of Doritos today – about five bucks per acre for hard rock mining throughout the West. Little has changed, including the price, and critics say it’s not only one of the oldest government giveaways, but one of the biggest as well.

CURWOOD: Well, with all the rhetoric about keeping government small and not wasting government resources, you’d think it’s about time to fix this.

DYKSTRA: No such luck, Steve. There have been periodic efforts to revise or abolish the 1872 Mining Law, but in this current Congress, there’s little chance of that. Mining companies have a very loud voice in western politics, and this is a remarkably sweet deal for them: A billion dollars a year in gold and other metals taken from federal land at five bucks an acre, no royalty payments. And taxpayers get stuck with the tab for cleaning up abandoned mines—and that adds up to more than two billion dollars in federal cleanup spending since the start of the 21st century, all thanks to a 19th century law.

CURWOOD: So there you have it: Some dicey environmental spending choices from the Nineteenth Century, heading towards the 22nd century. Nothing like a bit of depressing news, huh? Peter Dykstra is with EHN, that's EHN.org and The DailyClimate.org. And, well, thank you Peter.

DYKSTRA: All right Steve, thanks, we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And you can find more details on these stories at LOE.org.

Related links:

- State recommends Hanford budget strategy as cleanup falls 25 years behind

- Lead paint poisons poor Chicago kids as city spends millions less on cleanup

- Good news for Detroit: Lead poisoning of kids drops 70 percent since 2004

- The Pew Charitable Trust’s Campaign for Responsible Mining

[MUSIC: Federico Aberle, Maria Jose, Panamericana, ESL, 2007]

Checking Up on Native Plants

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

The Curtis Woodland Garden, Garden in the Woods in Framingham, Massachusetts. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

CURWOOD: May 4 started National Wildflower Week in the US, devoted to celebrating the wealth and beauty that carpet woods and meadows for free. So with spring so late here in Boston, for a glimpse of some blooms we headed out to a nearby suburb for a walk in the Garden of the Woods, the showcase and laboratory for the New England Wildflower Society.

There are some 3,500 species and subspecies of native plants in the region that are used to tough winters, though they are under stress from climate change, development and invasive species. We arranged to meet Elizabeth Farnsworth, the Senior Research Ecologist for the Wild Flower Society at its 30-acre woodland garden. She’s the lead author of this year’s “State of the Plants Report”, the most comprehensive assessment of native plants and plant communities ever assembled in the region.

[WALKING OUTDOORS, BIRDS CHIRPING]

Hi there, I’m Steve Curwood. And you are Elizabeth Farnsworth?

The alpine region is one of the habitats described in the New England State of the Plants report. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: Yes, indeed.

CURWOOD: We're here at the Garden in the Woods. So what's here?

FARNSWORTH: So what we have here is one of the most beautiful naturalistic gardens, one of the oldest in eastern North America. It has a wonderful selection of plants that, of course, you can use in your own garden, but also that broadly represents habitats of New England. So we've tried to really re-create the diversity of the different habitats, we have bogs, we have a beautiful pond here, we have a sand plain habitat that we just installed, so a whole range of different types of plantings.

CURWOOD: Now why do native plants matter here? There are wonderful plants like the daffodils and tulips that come from elsewhere that grace gardens. So why are native plants important?

The New England Wild Flower Society's Garden in the Woods in full bloom. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: Native plants evolved here. They evolved in these climates in the peculiar habitats of New England and all of the organisms that depend on them co-evolved with these plants. And so if you look at the tulips in your garden or the daffodils in your garden, how many bees are actually visiting those, how many butterflies are coming in to actually pollinate those plants versus if you look at some native plants all around you you'll notice that diversity is really attractive to them.

CURWOOD: So you recently completed a study of the region's plant life, how well it's doing, native, non-native, invasive, all that sort of thing. In brief, how are native plants doing in this region?

FARNSWORTH: So about 22 percent of our native flora are regarded as rare, that is endangered, threatened, special concern or even historic in one or more new England state. So close to 100 species, about 96 species, are now no longer known to New England. They may exist elsewhere somewhat precariously, but they're no longer here and that's a pretty substantial number of the majority of our flora is affected, about 30 percent have been brought from elsewhere introduced purposefully or mistakenly, that's about on par with other regions of the country. But about 10 percent of that set of non-native species are regarded as invasive. So that's 111 species.

CURWOOD: Invasive means trouble?

Northern hardwoods (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: Invasive means that these are plants that can grow quite aggressively. They can overtake native plants, they can outcompete them. They can come to dominate a particular habitat, so it becomes very impoverished in terms of plant diversity and often animal diversity.

CURWOOD: So let's talk about the big ones, what about trees, how they doing in this region?

FARNSWORTH: Well, trees are facing a number stresses and it's actually a good example right here at the garden. We have had to remove a number of Hemlock trees. These Hemlock trees have been attacked by these tiny white insects, the Hemlock woolly adelgid, which is spreading across New England. It's beginning to be seen further north. We have the Ash trees, which are being affected by the Emerald ash borer, which is on our doorstep, moving into western portions of New England. We have Sugar Maples that are showing some signs of being stressed by warmer temperatures, not necessarily pests or pathogens yet, but a lot of the climate models do predict a northward sort of contraction of the range of Sugar Maples, and that's, of course, an iconic tree for New England but also very important to our economy.

A riparian zone is a wetland area, often the adjacent to rivers and streams. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

CURWOOD: As I look around, I see some big trees here. There's this big Red Oak. How are these trees doing?

FARNSWORTH: Red Oaks are holding their own so far. We're worried about Sudden Oak Death which, of course, is the scourge of oaks in California with people transporting wood and potentially transporting disease, Red Oaks, of course, and we may remember that certain caterpillars really ravaged them, particularly in the 60s, Gipsy Moth caterpillars. I can recall from my childhood just listening to the rain of Caterpillar frass and complete defoliation of these trees. But they're pretty resilient. These guys have been here for probably 150 years and some are doing OK. Many of the climate models suggest as the temperatures warm that Oaks and Hickories will become much more dominant on the landscape. Trees which now tend you know to be dominant further south are likely to be moving into our area even as some of our more northern adapted species begin to contract north.

CURWOOD: So tell me more about climate change what did you find when you did this valuation of the plants, the flora as you scientists call it, in this region? How is climate affecting things?

New England salt marsh (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: We're already seeing the effects of shorter winters and warmer springs, drier summers. Plants on average are flowering many of them two weeks earlier in the spring. So, we're already picking up the signal but certain plants are responding very strongly to climate change and, in fact, some of our invasive species are responding more strongly than some of our native species. So, there's certainly winners and losers in terms of how flexibly plants can actually adapt to climate change. So we understand that's going to contribute to shifting in our natural communities. It also, the flowering behavior, of course, is really important to pollinators and so if there is an off-site between early flowering plants and the emergence of their pollinators, both parties are going to be unhappy.

CURWOOD: What has flowered early in the Garden in the Woods that you think you might attribute to climate disruption?

FARNSWORTH: Well, we are starting to see the emergence of these beautiful plants call Bloodroot that are members of the poppy family. When those flowers pop out, there's going to be a very big and white….

CURWOOD: Are they early this year?

Sand plains cover a good deal of New England habitat, some of which is thanks to development in the region. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

FARNSWORTH: I think they're actually a bit late this year. Climate change is a long-term phenomenon with a lot of very ability between years. As we've seen, the garden is relatively recently free of snow, but if you compare this to two years ago when we had a very mild winter, many of these plants would've been fully in flower or even finished flowering or even close to in fruit by this time, so these plants are highly sensitive to the temperatures.

CURWOOD: So, let's take a look around this pond here. How are ponds, size of rivers, wet areas, doing in terms of native plants here in the region?

FARNSWORTH: Well, it kind of depends on what type of wet area you're talking about. So for example, ponds are doing moderately well, although acid rain has changed the chemistry particularly of our northern ponds so they are much more acidic. They can't really support a lot of the plants that used to live alongside the pond or even in the pond, so they are pretty species poor. Some ponds are beginning to recover which is good news. Other wet areas, one of which that we covered in a report, are riverside areas, floodplains, sandbars--those very changeable habitats that occupy river systems. And they're extremely productive, they're very, very, rich and they of course do help with flood control.

[WALKING]

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

Sarracenia purpurea is a purple pitcher plant found around bogs. It's carnivorous and feeds on small insects. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

Now for something completely different this is a sand plain community. It is extremely dry habitat, think of Cape Cod, think of Martha's Vineyard, think of much of southern New England where the glaciers kind of dumped their sandy load. You'll see the plants that are growing on this landscape are kind of low and scraggly, Pitch Pine here. We have some nitrogen-fixing plants here like Bayberry so they're some of the first pioneers they can come into these really, really nutrient poor habitats, very dry habitats and survive.

CURWOOD: So in your study how are these plants doing? How is this biome doing?

FARNSWORTH: So sand plant habitats are really great for building things like cities and airports and suburbs because, of course, sandy soils perk, they tend to be nice and flat. So we've lost about 60 percent of the sand plains that were known from New England when the colonial settlers came in.

CURWOOD: So, this looks like cactus.

FARNSWORTH: Believe it or not we have a native cactus species in New England, and it is considered one of our rarest species. This is an Opuntia; it's a Prickly Pear cactus. And it grows in these tremendously dry, sand plain kinds of environments, sand dunes, other areas along the coast, and it's only known from a few populations. So one of the reasons that we feature these habitat gardens is to give people an idea of what kinds of native plants could grow in their own particular growing conditions. They'll grow up a lot better and that non-native Barberry that you're trying to get started.

NewEnglandWildFlowerSociety2015.png)

Garden in the Woods reproduced a sand plain habitat showcasing different varieties of native plants that grow in dry, sandy conditions. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

CURWOOD: Now, we're here in New England which is its own special place, but somebody listening to us in, say, New Mexico or California or Colorado...what would you suggest to them?

FARNSWORTH: I would suggest much of the same thing that we're doing here in New England and, in fact, by writing the report, we really wanted to begin a national conversation. You know, each of the different states are sort of doing their own thing, some states working harder than others to really maintain their native flora. Some states have more resources than others. Perhaps we can collaborate. California has its share of floodplain habitats that are being impacted. New Mexico has its share of sand plain habitats they're being impacted. So there are important lessons that really cross state boundaries.

Fall in Framingham, Massachusetts' Garden in the Woods. Several varieties of trees surround their lily pond. (Photo: Elizabeth Farnsworth, New England Wild Flower Society)

CURWOOD: So, what's the risk of not knowing about plants around us?

FARNSWORTH: When you don't know the plants around you, you won't know what you've lost when they're actually gone due to habitat destruction or disease or climate change, any of these threats. So it's really important that we understand that the plants are the foundation and when you start losing important species and this diversity of species then pretty soon Rachel Carson, and we get into many, many years ago, you won't hear the birds, you won't start to encounter the many animals, you won't see the butterflies, and then you make it any point of just how impoverished the natural community around you has become.

CURWOOD: What do you folks doing terms of seed saving if you're concerned about a species going away?

FARNSWORTH: So we do have a very active seed collection program. We are the largest seed bank for rare plants in the region, and we have both volunteers and staff who go out and collect seed very prudently from rare plant populations. We never collect from more than 10 percent of the plants, but we do maintain them in seed banks. They are something of a bet-hedging strategy, and we actually successfully recovered a species that was on the federally endangered species list.

Living on Earth's host Steve Curwood speaks with Elizabeth Farnsworth with producer Lauren Hinkel. (Photo: Jennifer Stevens-Curwood)

CURWOOD: And that was?

FARNSWORTH: That was Robin's cinquefoil. It's a very diminutive little member of the Rose family found only from a few populations on Mount Washington. So in the Alpine, the main population was being completely destroyed by trampling.

CURWOOD: Hikers.

FARNSWORTH: Hikers, and we actually restored many, many plants in the population and actually started a new one close by, so the plant was delisted. It's the only one in the US that's ever been taken off the endangered species list. So the report spells out all of a lot of the hazards for New England's rare plants in particular, but there's also some good news in there. Plants are really very resilient and there are actually things that we can do individually and collectively to celebrate flora and to make it resilient for the future.

CURWOOD: Elizabeth Farnsworth is a Senior Research Ecologist at the New England Wildflower Society. Thank you for taking the time with us today.

FARNSWORTH: Thank you so much. It was delightful talking with you.

Related links:

- New England State of the Plants Report

- New England Wild Flower Society

[MUSIC: Jpey Ryan and Ken Patingale, Laredo, Retrospective, Milk Carton Record, 2011]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, the hidden dangers lurking in talcum powder.

LEVIN: What could be seemingly less ominous than talc? We put it on babies' bottoms...You just sort of have no idea that there might be a risk here.

CURWOOD: Why women might want to think twice before they sprinkle on the powder. That’s next time on Living on Earth. That's next time on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Nat King Cole: Just You, Just Me, After Midnight, The Complete Session, Capitol 1956]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more; www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth