May 29, 2015

Air Date: May 29, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Rail Finance Off Track

View the page for this story

Several fiery crude oil train accidents and a deadly Amtrak passenger train derailment have sparked demands for national railway upgrades and regulations. But improvements require funding, and Congress has cut rail subsidies. John Olivieri, 21st Century Transportation Campaign Director at U.S. PIRG, explains to host Steve Curwood how improved rail service could cut our carbon footprint, and benefit passenger safety. (06:35)

The True Cost of Fossil Fuels

View the page for this story

Fossil fuels reap profits in modern economies in part because the costs of their environmental and health damage are not included in their price. A new report from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) finds that we're significantly underestimating society's subsidy for fossil fuel use worldwide. The report's co-author, IMF economist David Coady tells host Steve Curwood how they calculated fossil fuels subsidies worldwide annually cost taxpayers and consumers $5.3 trillion. (06:50)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about a coal company's proposed solution to energy poverty, some lesser-known winners and losers from the West Coast drought, and how lessons from actions to defuse the pesticide DDT's effect on Bald Eagles could be applied to America's threatened honeybees. (04:50)

Coal Rising in the West

/ Clay Scott, the Allegheny Front, Mountain West Voices, West Virginia Public Radio, High Plains NewsView the page for this story

Coal no longer provides the majority of US electricity, but strip mining coal is still big business in Montana and Wyoming, where massive machines gouge it out around the clock. Clay Scott of Mountain West Voices explores how western coal generates wealth, jobs and export dollars, but creates some problems for western ranchers. (09:35)

Discovering the Lost World of the Old Ones

/ Helen PalmerView the page for this story

The arid climate in parts of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico helps preserve its fragile history. So when author, climber and explorer David Roberts traveled and traversed into remote parts of the southwest, he found undiscovered evidence of the ancient peoples who lived there over many centuries. And as Roberts tells Living on Earth's Helen Palmer, these civilizations are still mysterious, but the struggle between preserving their buildings, art and artifacts in situ and the pursuit of knowledge is multifaceted. (17:25)

BirdNote: Protecting Our Largest Shorebird

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

In spring, the Long-billed Curlew glides back and forth above North America's western prairies, singing for a mate. But come winter, the large, tawny birds head for warmer southern shores and Mexico. These two drastically different habitats make protecting the rare bird a challenge. Mary McCann reports. (01:55)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: John Olivieri, David Coady, David Roberts

REPORTERS: Clay Scott, Peter Dykstra, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. With federal purse strings tight, there’s a call for cost effective transportation subsidies.

OLIVIERI: We get the best bang for our buck by putting our dollars into increasing rail than building that next highway. Rail is a way of increasing energy efficiency.

CURWOOD: Making the case for rail. Also new analysis pegs the total worldwide subsidies for fossil fuels at over $5 trillion dollars. And coal may a dirty fuel, but miners continue to sacrifice their health and even their lives to light up ours.

SIEH: Because we are willing to go out, and run that equipment, and mine the coal, and bring it out of the earth, and we work holidays, 24/7, through snow, through rain, everybody else has the luxuries of electricity and running water.

CURWOOD: We’ll have that and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

[THEME]

Rail Finance Off Track

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios in Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. America's railroads are in trouble. There have been a series of fiery crude oil accidents on freight lines and a mid-May derailment of a speeding Amtrak passenger train outside Philadelphia killed at least eight people and shut down the popular service between New York and Washington, DC, for days. But perhaps an even bigger problem for Amtrak is money. This year, Congress granted additional temporary funding to keep federal highway construction moving forward, but it chopped Amtrak's subsidy once again. Highways, airports and public transport all receive federal subsidies, but in the view of John Olivieri of the US Public Interest Research Group, passenger rail is woefully underfunded. John, welcome to Living on Earth.

OLIVIERI: Thank you, very happy to be here.

CURWOOD: John, where does the US stand compared to other countries in terms of rail technology, infrastructure and funding?

OLIVIERI: Well, the US is falling way behind when it comes to rail funding and transportation infrastructure and specifically falling way behind when it comes to the development of high-performance rail. Other countries have invested heavily in the development of high-speed rail. Japan has a train that goes 374 miles an hour. The Euro Star travels from London to Paris at 200 hundred miles an hour. These trains have a safety record that is absolutely stellar; yet we here in America are shocked to discover that a train was going 106 miles an hour. That is not a particularly fast speed in many other parts of the world, and we need to get to a point where our transportation system enables trains to be able to travel faster than 106 miles an hour in a safe manner.

Japan’s high-speed “bullet trains” routinely travel 200 miles per hour. A new maglev train in Japan broke the world speed record this April when it reached an astoundingly fast 374 miles per hour. In contrast, Amtrak's Train 188 was traveling at about 100 miles per hour when it rounded a curve and derailed. (Photo: Steinsplitter, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: In the wake of the Philadelphia crash, there's been criticism that despite receiving billions of dollars from Congress over recent years, Amtrak hasn't put this funding into action. How do you respond to this?

OLIVIERI: Well, I think it's an unfair criticism. Amtrak has growing ridership. In the last fiscal year alone, 30.9 million passengers have taken Amtrak, and about 11.6 million passengers have taken Amtrak in the northeast corridor. So Amtrak is providing a product that is clearly in demand, and when we look at the level of subsidies that Amtrak and other rail services are being offered relative forms of transportation like building new roads and highways, what we actually find is that rail is getting a much lower subsidy than driving. So, for example, the intercity rail system receives about a $1.50 in subsidies for each American whether or not they take rail on a daily basis or on a weekly basis. But if you compare that to the subsidies that our highway system receives, our highway system receives about $1,100 dollars a year from each person regardless of whether not they drive a little bit or a lot. In 2013, driving received about $69 billion dollars in subsidies. That's more than Amtrak has received in its entire 40-year history.

CURWOOD: Just a few hours after the crash outside Philadelphia, Congress actually cut funding for Amtrak. What you make of that?

OLIVIERI: Amtrak is not paid for in the way that we pay for other transportation priorities through the Service Transportation Act. Amtrak is authorized yearly in a separate appropriations bill, and that bill is the subject of perennial debate and discussion. There are those in the Congress that feel that we shouldn't be spending any money on public transportation. This annual reauthorization provides ample ground for those critics to go out there and expose those beliefs. I think it's unbelievable that the house would vote to cut Amtrak funding just hours after such a tragedy has occurred.

U.S. highways received $69 billion in federal funding in 2013 – more than Amtrak did in its entire forty-year history. (Photo: SayCheeeeeese, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So how has the Congressional propensity to restrict funding affected Amtrak's ability to allocate money where it's needed?

OLIVIERI: This is really a key point. Because Amtrak is authorized yearly rather than in longer increments as we do with some of our roads and our bridges, it becomes next to impossible for those at Amtrak to sufficiently plan for the transportation system that we're all going to need for the future. When we have discussions about: Wouldn't positive train control have prevented this devastating injury? How can we expect those at Amtrak to be able to fully implement such a complicated system when they don't know where their next dime is coming from, year to year.

CURWOOD: John, how should we upgrade our current rail system to make it safer and more efficient?

OLIVIERI: I start with the proposition that our rail system is experiencing record high ridership and is strongly projected to grow. Ridership has almost doubled since the year 2000 and growth has continued to be projected. So when we look at what investments are going to be needed, what we see is that in the northeast corridor, for example, in order to meet this projected future demand and in order to achieve a state of good repair, Congress is going to need to invest about an estimated $10 billion dollars over the next 15 years, and that's probably a conservative estimate. In 2007, Amtrak issued the northeast corridor infrastructure master plan and that put the total needed for investment closer to $52 billion dollars.

CURWOOD: What's the return on investment in rail infrastructure versus fixing the highways?

OLIVIERI: Well, fixing the highways is a different question from expanding the highways, and unfortunately, all too often we sacrifice dollars at the federal and the state level that are probably best put towards fixing our crumbling bridges and our infrastructure and instead we build new and wider highways. The major return on investment I don't think is necessarily a monetary one, though there are certain economic benefits to being able to move goods efficiently. I think the most important return on the investment from rail really comes for what it can do for our society, right? So rail is a way of increasing energy efficiency and when we compare rail to other forms of transportation such as driving, we see that we get the best bang for our buck by putting our dollars into increasing rail than to building that next highway which may be of questionable value.

John Olivieri, right, is the Transportation Campaign Director for U.S. PIRG. He speaks with host Steve Curwood in the U.S. PIRG office in downtown Boston. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

CURWOOD: So, compare the carbon footprint of passenger rail to the automobile and buses and so on and so forth.

OLIVIERI: So rail is significantly more energy-efficient than other modes of transportation, and it also has significantly lower carbon footprint. What we find when we look at rail is that light rail produces 62 percent less CO2 emissions per mile than a single occupancy vehicle would. Another way of putting this is that the average passenger car in the US produces just under one pound of carbon dioxide per mile, whereas a commuter rail or a light rail transit only produces about a third of a pound per mile. So there are substantial benefits to be had by investing more money in rail and making sure that we as American people opt for that form of transportation when it is available to us.

CURWOOD: John Olivieri is 21st century transportation campaign director for the US Public Interest Research Group. John, thank you so much for taking the time today.

OLIVIERI: Thank you, it's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- “Changing Transportation”: Research from U.S. PIRG

- The Northeast Corridor Infrastructure Master Plan

- Research roundup on Amtrak safety, rail transit and infrastructure issues

- Plans for high-speed rail in the U.S.

The True Cost of Fossil Fuels

CURWOOD: Well, calculating the value of a subsidy is not an exact science. What do you include? There is the cash money handed over or taxes uncollected. But what about benefits and harms? What if you factor in what economists call “externalities,” say increased economic activity or damage to health, or the environment? A new economic analysis from the International Monetary Fund that considers externalities of fossil fuel subsidies has come up with a whopping figure. Around the world, the IMF says, at the end of the day fossil fuels are costing taxpayers and consumers an extra $5.3 trillion dollars - that's with a T. One of the authors of this report is the IMF economist, David Coady. So we called him up to find out exactly how he reached that figure. Welcome to the program, Mr. Coady.

COADY: Thank you very much. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: First of all, tell me about this figure: $5 trillion dollars. That's five followed by how many zeros?

COADY: That's five followed by nine zeros, if I remember correctly.

CURWOOD: Yeah, that really is a number the catches the attention, but what is it actually encompass? I mean, I thought fossil fuels received about $200 billion dollars worth of support worldwide. Why this discrepancy?

COADY: Our main focus here is comparing the cost that people pay for energy, in particular, fossil fuel-based energy, to the cost that they would pay if they faced the true cost of the damage done by their consumption.

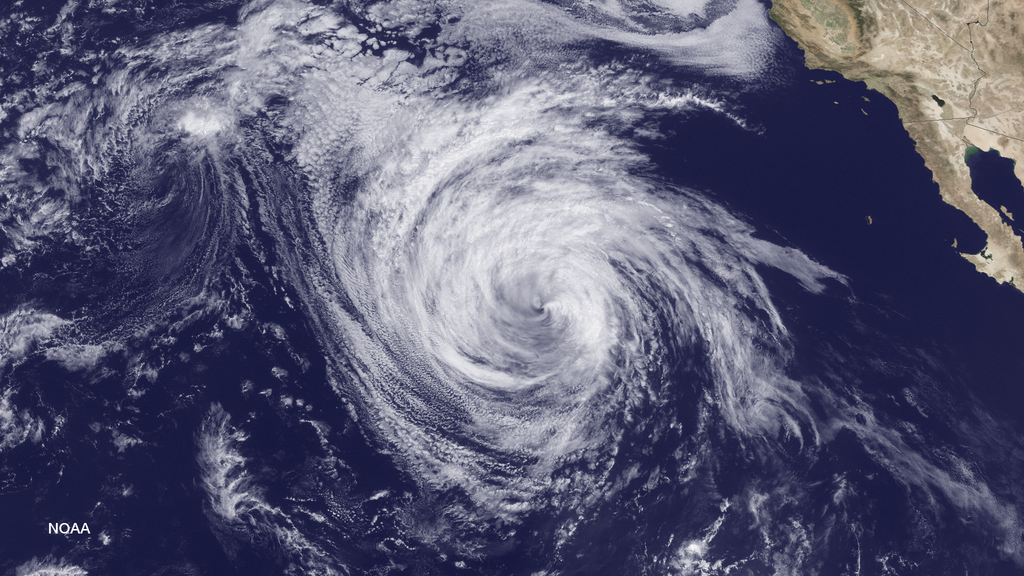

The cost of climate disruption is about one-quarter of the cost of fossil fuel subsidies estimated in the IMF report. (Photo: NOAA, Wikimedia Commons CC government work)

CURWOOD: So what are these collateral damages, if you will, that you're referring to here?

COADY: The local damages related to having particles in the air, breathing problems, health-related problems classified as increasing the mortality rate or just lower quality of life, and when you take these into account they're very substantial.

CURWOOD: How important is climate change in your calculations?

COADY: Climate change is undoubtedly very important. It counts for a quarter of the total of the subsidies, but it's the damage that is done locally that dominates - domestic pollution, domestic environmental damage. And so long before you have to be concerned about the global environment, concern for the local environment will move you towards the outcome that you think is desirable.

CURWOOD: How did you come up with these figures? Can you break them down for me?

COADY: We get a data from a lot of sources. We collect our own data on energy prices in different countries. We then collect information on world prices, the import prices people pay, and then we look at the environmental damage that's caused by this consumption from looking at places like World Health Organization and the valuation of that damage in terms of health damage. So we bring a lot of material together.

CURWOOD: How controversial are these figures to other economists?

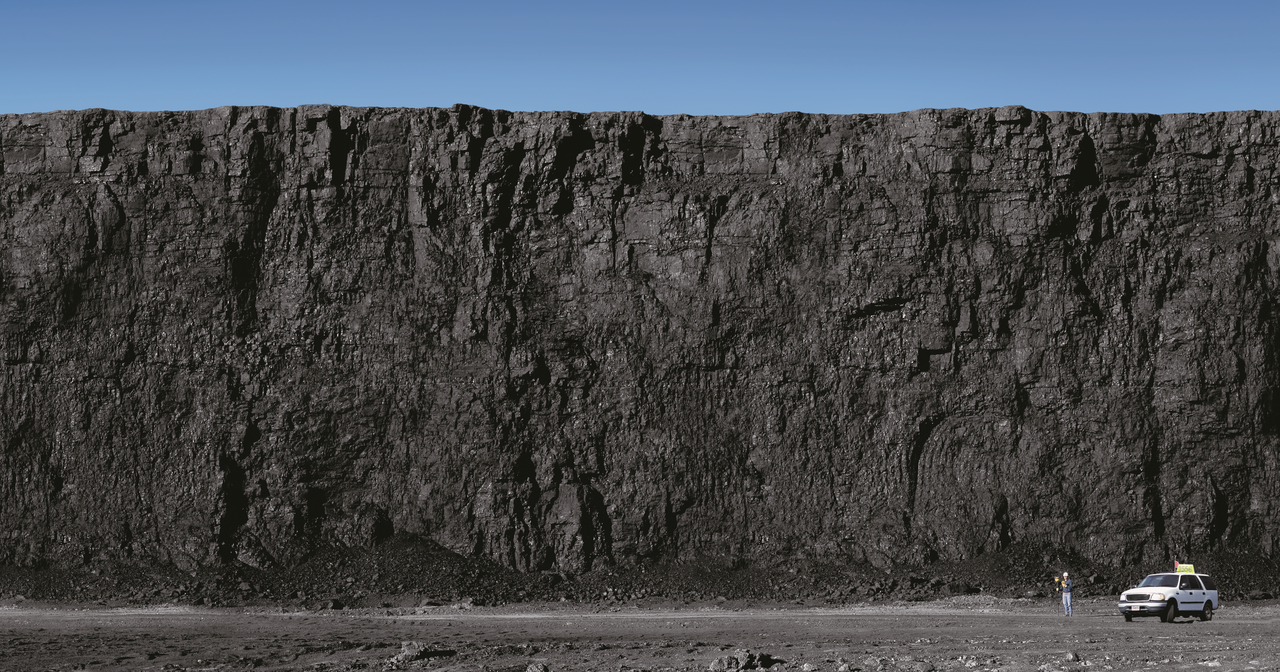

Deriving energy from coal, oil, and gas produces both local consequences, such as pollution and health impacts, and global consequences, including climate disruption.

(Photo: Peabody Energy, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0)

COADY: A number of people will argue maybe we should not add these things up, but from an economic perspective we say conceptually the true cost is the true cost. The reason we don't face the true cost is there's no markets for these damages.

CURWOOD: What about oil and gas companies? I imagine many would dispute your figures and point to the value of the economy that fossil fuels have helped to create. What's your counterargument there?

COADY: Clearly, we rely heavily on energy. The constraints on energy supply are a major constraint for growth in developing countries, for example. But here we're talking predominantly about consumer subsidies. These are subsidies that consumers face. We're saying we should internalize the damage by putting up the price that consumers face for this; so when they consume energy, they will actually take into account the damage it does, or face the cost when they make those decisions.

The local health effects of fossil fuel-based energy, such as asthma, are a major focus of the IMF’s calculations. (Photo: Mendel, Wikimedia Commons)

CURWOOD: So tell me, Mr. Coady, if you calculate the true cost of, say, a gallon of gasoline, what would that compare to today's prices?

COADY: In countries that have low taxes for energy products like gasoline and diesel, of which the US would come into play here compared to say northern Europe, the price increases will be of the order about 50 percent. In other countries, in which there are much lower prices, for example, in the Middle East, they would be multiples of them.

CURWOOD: So when fuels are subsidized, who pays? Where does the money for that come from, from whose pocket?

COADY: It's borne in two ways, either by countries having to raise their revenues, their taxes from other places. So for example it might come from higher labor taxes or higher corporate taxes. Alternatively it might come through just spending to be much lower. So, for example, in a developing country it would be much lower spending on education and health and infrastructure. In a developed country it may cut back on public infrastructure investment or it may just mean you've got higher income taxes. So it really depends on the country, but in the end, households pay. Households pay either because they face higher taxes or lower public services.

CURWOOD: So how big a deal is this $5 trillion dollars a year for fuel subsidies?

COADY: It's huge, which is why we think it's important to it put out there. The gains from reform are huge, as you would expect. And they can come in many forms. They can come in terms of improved health outcomes. But they can also come in terms of much higher revenues coming into the governments which they can then use it to reduce other taxes or to increase spending.

CURWOOD: What do you hope your new working paper and analysis is going to achieve?

COADY: I think the main thing we want is to start a big discussion about this. Already there's a big debate going on about: what is this number; what does it mean? This is the main objective, is to get a debate out there, to put a number out there, which we think is plausible. Many will argue it's conservative, others would argue it's much too high, but also it starts a debate about what's the right policy response to this.

CURWOOD: So I want you to make a forecast. Does the world get this subsidy thing right in your lifetime, do you think?

David Coady is the Division Chief at the Fiscal Affairs Dept. of the International Monetary Fund, and one of the authors of the IMF’s new analysis of fossil fuel subsidies around the world. (Photo: IMF)

COADY: Well, in my lifetime for sure. I think we could see major improvement in a decade. You already see many countries making moves when people thought this was not possible. Just take a country the size of India. India has over the last 5, 6 years really transitioned towards removing itself from the setting of energy prices and regulating them in the market and started to add excise taxes to these consumptions. So already you see in the big consumption of gasoline and diesel, India has made huge inroads over the last five years. China also has moved very much towards improving the framework for setting diesel prices and so on. So many countries are beginning to see and to argue that there are benefits in going down that road.

CURWOOD: David Cody is a Division Chief at the Fiscal Affairs Department of the International Monetary Fund and one of the authors of the new analysis of fossil fuel subsidies around the world.

Thank you so much, Mr. Coady, for taking this time with us today.

COADY: Thank you for having me.

Related links:

- IMF Working Paper: “How Large Are Global Energy Subsidies?”

- “The IMF says we spend $5.3 billion a year on fossil fuel subsidies. How is that possible?”

- “Fossil fuels subsidized by $10m a minute, says IMF”

- About David Coady

[MUSIC: Norah Jones, One Flight Down, Come Away With Me, Blue Note, 2001]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the US electricity market is cutting back on coal, but vast quantities are still being mined in the west, a lot for export. Stay tuned to Living on Earthl

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski, Martin and Wood, Shine It 2, End of the World Party, Blue Note 2001]

Beyond the Headlines

Neonicotinoids are found in popular garden treatment products, but most products don’t contain labels warning that they harm honeybees. Studies show the chemicals might make bees more susceptible to parasites. (Photo: Swallowtail Garden Seeds, Flickr CC BY 1.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Let’s head off to see what’s happening beyond the headlines now. Peter Dykstra of Environmental Health News, EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org acts as our guide, and he joins us on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, Peter, what’s up?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve. Let’s start with a little bit of a facepalm from a coal industry giant, actually a double facepalm. A buzz phrase these days is “energy poverty,” the notion that poor people are poor, in part, because energy is so expensive. Well, the men and women of Peabody Energy would like you to know that the solution to energy poverty is to buy more and more of their coal.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but I think we’ve learned that there are some major side effects from coal burning.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, just a few, but that’s not what gets me about this. Peabody’s a 125 year-old company that built its declining fortune on the backs of coalmining families in the Midwest and Appalachia. They helped create some of America’s poorest communities. So coal as cure for poverty is a bit of a reach. But Steve, Peabody’s not done reaching.

Peabody Energy recently created a video promoting the coal industry as a force to fight energy poverty in developing nations like China. Critics say the company’s push for a humanitarian image is intended to distract from its contributions to climate change. (Photo: Rennett Stowe, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: OK, what else?

DYKSTRA: I’m not making this up, and presumably neither were the folks at the Guardian when they first reported this, but at an industry conference last September, Peabody CEO Greg Boyce suggested that more coal energy could have helped develop and distribute an Ebola vaccine more quickly and possibly could have staved off the Ebola epidemic in West Africa. Steve, coal can do anything.

CURWOOD: Well it is true that many parts of Africa don’t have access to abundant electricity, but there wasn’t a vaccine to distribute so it seems a stretch.

DYKSTRA: It seems a ludicrous stretch, according to health experts – and one final note on all this: Mr. Boyce retired this month as Peabody’s CEO, and he’s reportedly earned over $57 million dollars over an eight year stretch as a coal boss.

CURWOOD: So coal seems to have cured HIS poverty. What’s next?

DYKSTRA: We’ve heard lots about the big losers in the West Coast drought: agriculture, big drinking water systems. Everybody’s hurting, and even when rains do come, like in Texas and Oklahoma recently they can take a big toll in lives and property. But let’s take a quick tour of some of the other less visible things hurt by this epic drought on the West Coast.

Whitewater sports for example. No snowpack in the Sierras, no roaring rivers, and a greatly reduced rafting and kayak season.

Salmon, and salmon fishermen. Steve, if you’re a salmon, and I’m not saying that you are, and your spawning river is too warm and dry, how do you get back to the ocean?

CURWOOD: Well since it’s California, Peter, I’m tempted to say you take the freeway.

DYKSTRA: Of course you do. State and Federal agencies have trucked salmon by the millions downstream to San Francisco Bay since February. A few more things: Millions of trees are dying, in forests and also in cultivated orchards for fruit and almonds. The dying forests usually mean a bad wildfire season.

The whitewater-rafting season is being shortened by decreases in snowpack caused by the West Coast drought. Snow in the mountains feeds into rivers, raising water levels, but without enough snow, the water is too shallow to keep rafting enthusiasts and businesses afloat. (Photo: Jeremy Jannene, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

And California gets nearly 20 percent of its electricity from hydropower in a normal year. Last year, that fell to 8% as less water passed through hydrodams. So toss in a little powerless with your thirsty.

One winner in the drought: Landscaping services, who offer lawn painting. Yes, lawn painting. If there’s no water to green your lawn, a nice dye-job will have to do.

CURWOOD: Oh my! So what’s our history lesson for this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Steve, it’s a lesson from history indeed, but not necessarily one that we’ve actually learned yet. Seventy-five years ago this week, Congress and President Franklin Delano Roosevelt enacted the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.

CURWOOD: Yeah, Congress and a President, working together, I’ve heard about that.

DYKSTRA: Back in the day it happened, Steve. The law was in response to a drop in eagle populations, from habitat loss, from hunting, from people in pursuit of eggs or eagle feathers, and it was hoped that bald eagle populations would stabilize as a result of this new protection. But nobody factored in the rise of DDT; the miracle pesticide had just been invented a year earlier in 1939. So as the law helped stop people from taking Bald Eagle eggs, we learned after over time that DDT made birds’ eggshells thinner, and our National Symbol ended up perched on the Endangered Species list.

CURWOOD: But DDT was banned in the ‘70’s, and the eagles are coming back.

Seventy-five years ago, the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act prohibited people from removing eagles and their eggs from the wild. But it wasn’t until the insecticide DDT was banned in 1972 that populations began to recover. The number of bald eagle nesting pairs skyrocketed from 417 in 1963 to 9,789 in 2007. (Photo: Bill Evans, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Precisely, and that’s the lesson we may or may not learn. President Obama recently announced an ambitious plan to save honeybees. The crucial pollinators have been in a freefall, and the government is taking steps to create and save bee-friendly habitat. But the President’s plan doesn’t pay much attention to the relatively new class of pesticides called neonicotinoids that are widely believed to be a big contributor to the bee crisis. Honeybees may or may not have time for us to play catch-up with these modern pesticides like we did with DDT. And to tie it all together—one of the most honeybee reliant food crops in the U.S? All of those thirsty almond trees out in the California drought.

CURWOOD: So let’s hope there’s a Plan “Bee” for pollinators. Thanks for that, Peter.

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, thanks a lot; we’ll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org and there’s more on these stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Peabody Energy tries to rebrand coal as a cure for poverty

- Peabody energy claims coal could have curbed the spread of Ebola

- The CEO of Peabody made $57 million during his eight years in office

- http://greenpeaceblogs.org/2015/01/27/gregory-boyce-retiring-peabody-ceo-howd/

- Salmon driven to safety from California's drought-plagued shallows

- California drought kills millions of trees

- Lawn painting businesses are booming as the drought drags on

- The 1940 Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act helped eagle populations bounce back from near-extinction

- Pesticides called 'neonicotinoids' pose a major threat to honey bee colonies

[MUSIC: Michael Penn, Coal, Free For All, RCA Records, 1992]

Coal Rising in the West

A coal haul truck on the Eagle Butte Mine in Gillette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

CURWOOD: Last week, we looked at the legacy of coal in Appalachia: how mining employed and fed generations, shaped and helped destroy the landscape. And we looked ahead to ways one-time miners and their families were trying to forge a future in the face of declining domestic consumption of coal. But in Montana and Wyoming, coal is still mined in huge quantities. It’s plentiful there, easier to access, and cleaner burning than West Virginia and Kentucky coal. Western coal is the focus of the last part of this team report from Mountain West Voices, High Plains News, West Virginia Public Radio and the Allegheny Front. Here’s Clay Scott.

[SOUND OF COAL TRAIN]

SCOTT: It’s a familiar sight in much of the country – long, slow trains of 100…120 cars or more. Each piled high with dull, black coal. 70% of all American coal moves by rail, often a thousand miles or more to its destination. Most of the time, that destination is a power plant. But some coal heads to ports for shipping - to meet demand in Asia, and perhaps, more surprising, Europe. The biggest coal ports are New Orleans, Mobile and Houston-Galveston on the Gulf Coast, along with Norfolk and Baltimore in the East.

[SOUND OF COAL TRANSPORT SHIP]

SCOTT: Several proposed coal export docks, especially on the West Coast, met intense public opposition, and they were forced to fold. Many opponents are concerned about carbon emissions into the atmosphere anywhere, and they say: “Leave it in the ground.” Others have a different worry - the coal dust that can blow off uncovered rail cars – up to five hundred pounds per car per five hundred miles. These nixed export terminals would have taken their coal from the Powder River Basin – the region straddling Wyoming and Montana that has long since eclipsed Appalachia as the center of American coal production.

The coal face of the Eagle Butte Mine near Gillette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

Even with a slight recent dip in production, Wyoming alone still produces 40% of the nation’s coal – far more than any other state. And although coal in the Powder River Basin shares a crowded field with many other resources being extracted – oil, gas, uranium – it is the energy-rich black rock that has left the biggest stamp on the people and landscape of this region.

Traveling south of Gillette, Wyoming, through an arid and austere country once home to herds of bison, you pass coal mine after coal mine, for 70 uninterrupted miles, carving deep troughs into the prairie. Seen from a distance, the immensity of the mining activity is striking. But descend into one of these open pit mines for the first time, and it’s hard not to be overwhelmed by the sheer scale of things.

[SOUND OF EXPLOSION]

SCOTT: Blasting teams set explosive charges to loosen the steep sides of what look like gigantic sunken amphitheaters. Colossal digging machines called coal shovels load hundreds of tons at a time into haul trucks three stories high. Huge bulldozers rip away layers of dirt to get at rich coal seams, and clouds of brown and black dust darken the air. Endless trains of railroad cars snake through the mine to be piled high with coal. The scene is at once intimidating, surreal, and impressively efficient.

Bill Ritchie is a retired coal mine manager. (Photo: Clay Scott)

[SOUND OF CLIMBING LADDER]

SCOTT: At the Eagle Butte Mine, near Gillette, J. D. Dietsche showed me the coal shovel he’s operated for Alpha Coal for a decade, seven days on, seven days off. On a frigid day, my hands stick to the metal rungs as we climb into the $50 million dollar machine.

DIETSCHE: You drive your truck to the dirt shovel, get a load of dirt, take it to the dump, come back and do it again and again and again and again, [laughs] for 12 ½ hours. Minus your half hour lunch break. It is very, very repetitious.

SCOTT: It is repetitious work, often dangerous, and the hours are long. But coal is an important part of the economy of this sparsely populated state, and the 7,000 or so jobs it provides are highly sought after. Miners like Carrie Sieh, who’s worked in coal for 30 years, have raised their families with their earnings. But it’s more than just a paycheck.

SIEH: Because we are willing to go out, and run that equipment, and mine the coal, and bring it out of the earth, and we work holidays, 24/7, through snow, through rain, through all kinds of weather, then everybody else has the luxuries of electricity, and running water.

Miner Carrie Sieh in Gilette, Wyoming (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: The coal that’s mined each year in the Powder River Basin – 400 million tons of it - supplies power to millions of people. It’s lower in polluting sulfur than eastern coal, and closer to the surface. But while you might not have to blow the tops off mountains to get at the seams, coal mining here has still impacted the land, and the people who depend on it, in profound and far-reaching ways.

[SOUND OF MAGPIES]

TURNER: From our perspective in here, it really seems that most of the time, we’re the only ones that don’t have the ranch for sale and hoping to sell it to the coal company.

SCOTT: That’s L. J. Turner. His family has ranched in the southern end of the Powder River Basin since 1916.

TURNER: This is home. It’s been home for all of our lives. It’s uh…it’s going to continue to be so.

SCOTT: We’re standing on a low ridge at the eastern edge of L. J.’s ranch, looking out at the North Antelope – Rochelle coalmine. The mine sprawls for miles over pastures where cattle once grazed. Historically, ranchers in this area have depended on public grazing leases to make a living. But those leases are superseded by mineral development, and the Turner family has lost thousands of acres to mining. This is – or it was – a landscape of rolling grassland, punctuated by rugged breaks where mule deer took shelter. But the contours of the land have been altered to get at the coal. By law, the coal companies are bound to “reclaim” the land when they’ve finished mining it.

Alpha Coal's Eagle Butte Mine is close to the city of Gillette, Wyoming. (Photo: Clay Scott)

TURNER: The coal miners over here whenever they first moved in and started taking our pastures, they said: “Oh, you just wait until we’ve reclaimed this land. It’s going to be so good you won’t believe how good it’s going to be,” and that’s been…thirty years ago, maybe? And our cows have never had a mouthful of reclaimed grass in those thirty years.

SCOTT: Of even greater concern, says L. J., is the steady drying up of local water sources, which he attributes to coal mining.

TURNER: Are they going to be able to reclaim these aquifers and the creeks? Because I don’t think they can. They say they can, but all they’re doing is talking theory. And here I’m living the practical thing.

[SOUND OF RIVER]

SCOTT: In western Montana, at his home along the Bitterroot River, I met Bill Ritchie. He’s someone who’s given a lot of thought to the impacts of western coal mining on water. Over more than 20 years he managed several mines in the Powder River Basin.

RITCHIE: There are problems. There are water problems; there are things that are hard to replace, and hard to reclaim. The really complex stuff was the environmental issues: tracking the water, trying to de-water, trying not to pollute streams. Really took a lot of work, a lot of effort, and a lot of money.

J.D. Dietsche works as a coal shovel operator at the Eagle Butte Mine. (Photo: Clay Scott)

SCOTT: When Bill first started working in coal, he says, western mines were being applauded for producing a product that was much cleaner than eastern coal. But toward the end of his career, he told me, he started to reexamine some of his assumptions about coal mining.

RITCHIE: We didn’t understand the impact on the atmosphere, and the greenhouse gases. We didn’t understand mercury as well, or the problems it creates in people’s health just burning it. We worked on clean coal projects from the time I was first starting in the coal business. And they still are working on ‘em. There is no such thing currently as clean coal. But the net result is still polluting the atmosphere.

SCOTT: All coalmines, says Bill Ritchie, including the ones he managed, begin by taking the coal that’s closest to the surface, and easiest and cheapest to get at. As the mine goes longer in its life, the coal will be deeper, and thinner seamed, and more costly to recover.

L.J. Turner overlooks grazing land that he lost to the coal mining industry. (Photo: Clay Scott)

RITCHIE: Hopefully someday they will figure out a technology on a commercial scale that can burn coal cleanly. But what a pity if we’ve mined all the coal, burned it, polluted the hell out of everything, and then when it’s time, when we have the ability to burn it well, we don’t have the resource.

SCOTT: Bill Ritchie says the type of clean coal technology he’s talking about, is not likely to be perfected anytime soon. In the meantime, coal, that powerful and dirty and much debated black rock, is certain to remain a feature of the economy and landscape of the West for many years to come.

In Gillette, Wyoming, I’m Clay Scott.

[MUSIC: Mark Ishan, In Half-Light of the Canyon, A River Runs Through It Soundtrack, Allied Filmmakers, 1992]

CURWOOD: Clay Scott of Mountain West Voices was also the producer of this team report on coal, in association with the Allegheny Front, West Virginia Public Radio and High Plains News.

Related links:

- Breaking Beans: a storytelling project that tells the story of food and farming in east Kentucky

- Ivy Brashear's Renew Appalachia: stories of transition

- Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation

- The Allegheny Front

- West Virginia Public Radio

- High Plains News

- Mountain West Voices

[MUSIC: Mark Ishan, In Half-Light of the Canyon, A River Runs Through It Soundtrack, Allied Filmmakers, 1992]

CURWOOD: Coming up...hiking the cliffs and canyons of the southwest in search of traces of the “Old Ones” who once lived there. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food, and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dick Hyman Group Featuring Howard Alden, I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles,] Sweet and Lowdown, Sony Classic 1999]

Discovering the Lost World of the Old Ones

Ancestral Puebloan granaries high above the Colorado River at Nankoweap Creek, Grand Canyon. (Photo: Drenaline, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: David Roberts is a climber and explorer – and author of books on subjects as varied as Mount Everest, the Mormons and the Apache wars. But one particular book that he wrote twenty years ago caught the public imagination. It was called “In Search of the Old Ones.” It detailed his explorations and discoveries of sites in the southwest of the US, parts of Utah, Arizona, New Mexico and Colorado, where ancient peoples had lived, and built dwellings and storehouses in remote and inaccessible canyons. Well now David Roberts has revisited those areas in a recently published book “The Lost World of the Old Ones,” and Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer visited him.

PALMER: David Roberts, I'd like to start with "The Old Ones"...who were they?

ROBERTS: Archaeologists since the 1930s have broken the southwest into four main groups of old ones: the Anasazi were the most studied, in the central four corners area. North of them: the Fremont. Southwest of them among around Phoenix: the Hohokam, and we know that the Hohokam became today's Tohono o'Odham, and then directly south and into Mexico, through most of New Mexico into Mexico: the Mogollon, and we have no idea what happened to them. The reason for these four distinctions is that the material culture is entirely different, for instance, the Hohokam built canals; the Anasazi didn't. The Hohokam cremated their dead; the Anasazi buried them on their side with their knees flexed up to the chest. Fremont granaries are top loading; Anasazi granaries are frontloading. But they're reasonable distinctions and they worked for 70, 80 years.

PALMER: And their pottery styles are different too.

ROBERTS: Yes, you get different pottery styles not only century by century, but Mogollon and Anasazi pottery don't look anything like each other.

PALMER: I thought that the people who built the rock dwellings in places like Chaco Canyon and Canyon de Chelly and places like that were known as the Anasazi, but you write that's an inappropriate name. Can you explain this?

PALMER: Well, it's a question of political correctness, and unfortunately Anasazi I think is a perfectly good name but certain Puebloans objected to it because it's a Navajo word which means something like “ancient enemies” or “enemies of our ancestors.” And so in the last 15, 20 years, there's been a move to outlaw the word and substitute for it “Ancestral Puebloans.”

Monument Valley in northern Arizona and southern Utah. (Photo: Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

PALMER: But that too is inappropriate because Pueblo is...

ROBERTS: ...Spanish, yeah!

PALMER: And there weren’t any Spanish here at the time they were building these!

ROBERTS: Of course not!

PALMER: So what were these people in this area really called? Or is there a better way to define them?

ROBERTS: We don't know what the Anasazi called themselves. If we did, we'd use it. It's a little bit Eskimo and Inuit, but at least we have living Inuits, who can tell us what they call themselves, but we're at a loss for a good term.

PALMER: We're looking at an area where there were ancient civilizations going back many years BC, in fact.

ROBERTS: Yes.

PALMER: What do we know with the various pre-civilizations who were there as? What are we calling them?

ROBERTS: We divide the pre-history of the Southwest into Paleo Indian, the very oldest, going all the way back to Clovis archaic which begins about 6500 BC and then you get first basketmaker and then you get Puebloan, or Pueblo, although they're all one people. So we can't tell how long the Ancestral Puebloans were in southwest, but as far back as we can trace them, they were there, unlike the much more recent tribes such as Navajo, Apache, Comanche, Ute, who were in the southwest only within the last 1,000 years at most or maybe 500 years only.

PALMER: They weren't the people who displaced the Ancient Puebloans?

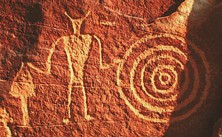

Fremont petroglyph from Dinosaur National Monument (Photo: J. Q. Jacobs, CC BY-SA 2.5)

ROBERTS: No, it's interesting. When the first ethnographers saw the empty cliff dwellings, they assumed that some other people had chased the Anasazi out, fought with them, banished them, but there's no evidence that they overlapped at all. So what seems to have happened, the great abandonment just before 1300 AD was a case of Anasazi on Anasazi violence, raiding, maybe even warfare - caused by really hard times - famine, drought, depletion of big game - all kinds of environmental factors. But the puzzle is that the Anasazi survived worse droughts before that and the climate was basically the same then as it is today, so something happened at the end of the 13th century that did cause this total and massive abandonment. It's not a disappearance; it's an abandonment. We know they went south and east and in some form became today's Puebloans.

PALMER: Now, a lot of your book focuses on discovering some of these very hidden architectural features, a lot you call granaries, but also some of them are places that were obviously spiritual places, dwelling places, tell me a little bit about these kinds of trips to discover these very hidden places.

ROBERTS: My book is not simply a popular archaeology book; it's a quest narrative of some sort because what I have been doing for 25 plus years is hiking into really remote canyons looking for rock art and ruins that almost nobody knows about. The archaeologists don't really get out and do this so much. They dismiss the sites as marginal and unimportant. And also, the Anasazi - if I may use the word again - they were brilliant climbers. So I was immediately drawn to the incredible feats that the old ones did to get to granaries and dwellings way up vertical cliffs that look incredibly difficult to access today.

PALMER: So, I mean, you describe various ways that they did manage get to the granaries, and the granaries they were building because of the drought, because they needed to store corn?

ROBERTS: Most of the really inaccessible granaries date from the 12th and 13th centuries when times are tough, and the idea is that the most precious thing is your food. You've got to keep the food away from other people, so you put the granaries in the hardest to get to places. We've gotten to granaries that, it was everything we can do to get to them and somehow the ancients not only got there, but they hauled up stones and mud to make the granaries. They hauled up their corn and beans and squash to fill the granaries. They climbed back up to retrieve the stuff regularly. It's a profound mystery.

PALMER: Now, you talk about how many of these places have been preserved by a very strange cast of characters, some of which where ornery ranchers. Tell me about Waldo Wilcox.

ROBERTS: Waldo Wilcox is one of the heroes of the book. He owned a spread in Range Creek in central Utah near the Green River for 50 years. He kept everybody out. And unlike almost all other ranchers in the west, he didn't gather up keepsakes when he found them - what he calls “Indian stuff” on the ground. He left it where it was. He had this just instinctive idea that it was not his right to mess with the Indian stuff. And when after 50 years he sold his ranch to state of Utah and the archaeologists had a look at it, they were absolutely dumbfounded because here was the most pristine valley archaeologically speaking in the whole west, maybe in the whole contiguous United States. But that unleashed some really rancorous disputes among the various parties interested in it. The state of Utah Department of Wildlife wanted to turn it into a hunting/fishing preserve. Fortunately the archaeologists won out, but then they started gathering up everything that Waldo had left in place. And to Waldo's great, and my great dismay, they applied sort of 50 year old techniques: scooping everything up and putting in plastic bags and taking it off to Salt Lake City. And you know, I think, if you have artifacts in a museum drawer where nobody ever looks at them, it's not much different from looting them.

The Black Hole of White Canyon in Cedar Mesa, Utah. (Photo: Dave Riggs, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

PALMER: So the area that Waldo protected which was very pristine is now just like everywhere else?

ROBERTS: Range Creek hasn't been severely looted. There has been some looting by outsiders, but the effect of the archeological team has been to strip it of most of at least most of the surface artifacts. They haven't done a lot of digging yet. It's still an incredibly rich place. It's not as denuded as much more vandalized, hammered mesas and buttes and canyons elsewhere in the southwest, but it's sure isn't what it once was—what it was in 2001. It's a tragedy, I think. Range Creek by the way, is not Anasazi but rather Fremont, which is the northern neighbors of the Anasazi, and so much less is known about the Fremont that this is all the more important. But the history of archaeology in the southwest is rife with cases where major excavations over 20 years ended up with a chief archaeologist never writing it up and that is the worst kind of destruction and loss you can have.

PALMER: Now, your first book which was called, "In Search of the Old Ones," it caught the popular imagination, but it earned you a degree of opprobrium among archeological fraternity. Can you explain that?

ROBERTS: Yes, I had no idea. "In Search of the Old Ones" was published in 1996 and I began the book with an account of discovering a pot in a small canyon on Cedar Mesa. And I ended with discovering with my wife Sharon an amazing basket, 1500-year-old basket, in another canyon on Cedar Mesa. But I didn't give any directions or any hints where these things where. I wasn't going to give away their location. It was just about how amazing it was to find them. Well, what I simply failed to anticipate was that my book would be used as a treasure map and people would show up with copies in hand at Kane Gulch ranger station and ask the rangers or demand of the rangers, "How do I get to Roberts' pot?" and this caused a kind of backlash. And even today, I get grief from some of the aficionados, who think that I'm popularizing places like Cedar Mesa and contributing to their ruination.

PALMER: Well, you found exactly the same thing when you went to one of the early places that you'd been to, that you had written about.

Anasazi petroglyphs at Petroglyph Point, Mesa Verde National Park (Photo: Frank Kovalchek, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ROBERTS: Oh, I've seen so many sites that were once rich with artifacts potsherds, lithics that have been stripped completely, but that's inevitable. That's been happening since 1870 in the west in places like Blanding, Utah, they used to go out on Sunday and just dig up ruins for fun, Sunday picnics, even though it's all totally illegal and was even after 1906. But it's really dismaying to go to a site that you once saw that was so rich in things and to find it stripped. That's why I wrote this op-ed piece for the New York Times, arguing that even though I sort of hate the idea of turning Cedar Mesa into a national moment, that may be the only way to save it.

PALMER: Well, why isn't a national monument a good idea? Doesn't this, in fact, preserve places?

ROBERTS: National monuments inevitably bring hoards of people. Right now, Cedar Mesa sees 70,000 visitors a year. It sounds like a lot. Grand Canyon sees four and a half million. Rocky Mountain National Park sees four million. Yosemite: four million. If you make Cedar Mesa a national park it will at least see 500,000, and a lot of them won't know what they're doing. And also there will be all sorts of rules and regulations about what you can do and can't do, but as it stands now under the Bureau of Land Management, there's just no way to protect it. There's two rangers to police 600 square miles of outback. Not possible.

PALMER: And in fact there are movements in Congress and there've been new regulations in the Utah state Congress that do open these places up and want to open these spaces up.

ROBERTS: Three years ago, the Utah Legislature passed a bill demanding that all federal lands in Utah except the national parks, the five national parks, be turned over to the state. The governor signed it and they made a deadline of December 31, 2014. And when that day came and passed and the feds didn't turn over the land, they renewed their efforts; they devoted $2 million to try to bring a lawsuit. And the only thing that may stop this is if some court declares the law unconstitutional, which we all hope, but I was really shocked just this winter, to find that the US Senate voted 51 to 49 in February to encourage the states to do the same thing. I hate to say it, but it's a Republican era, and Republicans don't believe in federally protected land for the most part.

PALMER: Well, they do argue that it is the states rights to have the value and the use of their own lands.

ROBERTS: Gosh, no. Not at all. I'm appalled by the fact that the US is one of the few countries in—maybe the only country in the Western Hemisphere—in which you are allowed to dig anything you want, unless it's a burial, on private land. If you're in Guatemala or Mexico and you discover an ancient tomb or even just a settlement, it belongs to the government. You have no right to dig it up. If you have a dolmen in your backyard on your country estate in England, you have to allow the public access to it. You can't fence it off and put up no trespassing signs. We, Americans, put such sanctity on private property that we allow this kind of what really is looting to go on under the claim that it's private land, and you can do what want with it. You can go on eBay and look up Anasazi pot and you'll find all kinds of beautiful vessels. And everyone will say we have a deed proving this was dug on private land. Well, that's just nonsense. A lot of them were looting from BLM land from state forests, but how do you disprove a fake title?

PALMER: Well, you say that it's not a great idea to make things a national monument because then all the people will come, but is the alternative to do as they've done with many of the prehistoric caves, with cave paintings, say that no one can ever go into them?

ROBERTS: Like Lascaux, yeah. I fear that may be the ultimate solution in the southwest, that places like Betatakin and Keet Seel--some of these great ruins--we simply won't be allowed to visit them anymore. I mean, even now, on Mesa Verde, there are perhaps 400 ruins and you're allowed to visit two or three of them. The other 397 are off-limits to the public.

Together with his wife, Sharon, Roberts found a 1,500-year old basket in Cedar Mesa. (Photo: Helen Palmer)

PALMER: But a problem you point to is that the BLM has insufficient manpower, insufficient funds, and that isn't likely to change at least with the present Congress we've got.

ROBERTS: The present Congress would probably like to do away with the BLM altogether. The big advantage of a national monument is it would mean much greater staffing, much greater money to take care of the place. You do have four and a half million people in the Grand Canyon, but you actually don't have very much looting because of the manpower and the financial resources. You may have overcrowding, but you don't get the kind of desecration that you get on BLM lands all over the place. But the reason I pushed for a monument in my op-ed piece for the [New York] Times was because the president can decree an national monument - and Obama has been doing it - but a national conservation area requires a vote of Congress, and the way Congress is trending, I think there's no chance in hell that they'll make Cedar Mesa a national conservation area, or any other good place.

CURWOOD: That’s David Roberts, author of “The Lost World of the Old Ones” in conversation with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

Well, the questions the book raises are deep, even philosophical and we’d like to know what you think. How should we protect fragile lands and their irreplaceable archaeological heritage?

The US Senate recently passed a resolution stating that public lands not designated as National Parks or Monuments should be managed by the states. But some say that approach would mean opening these historic sites up to mining and other commercial interests. On the other hand, many in those Western states say they know their territory better than the federal government and can do a better job of protecting this heritage.

So please tell us what you think. How should America protect this heritage and who should be in charge?

Please go to our website LOE.org and find the comments section at the bottom of the transcript for this story, where you can see what other listeners have to say - and put in your two cents. Or just send an email to comments@LOE.org – that’s comments@loe.org. Or call our listener line at 800-218-9988. That's 800-218-9988, and be sure to tell us how we can reach you.

Related links:

- Saving What’s Left of Utah’s Lost World

- More about Roberts' "The Lost World of the Old Ones"

- Utah's Bureau of Land Management

- About National Conservation Areas and National Monuments

- Mesa Verde

- Cedar Mesa

- About Ancestral Puebloans

BirdNote: Protecting Our Largest Shorebird

[MUX - BIRDNOTE® THEME]

CURWOOD: We’re staying out west for one of the most evocative of birds – at least, if you listen to its song. And as Mary McCann explains in this BirdNote®, this particular bird is facing a double set of threats.

BirdNote®

MCCANN: Singing over the Grassland

[Display song of Long-billed Curlew]

MCCANN: In spring, the male Long-billed Curlew sings his bubbling song, stitching a zigzag across the sky. Seeing it rise on rapidly beating wings, then glide down, we’re witnessing its mating display. We’re seeing North America’s largest shorebird in its breeding habitat: a western grassland.

[Display song of Long-billed Curlew]

Long-billed Curlews may be the largest, but they’re also among the rarest. Their numbers are declining as arid grasslands disappear.

Come early autumn, the curlews will depart the prairie to spend the winter in rice fields of California and on mudflats of our southern coasts. Some will continue into Mexico.

A male Long-billed Curlew soars across the skies above North America's grasslands. (Photo: Jerry Kirkhart)

[Flight calls of Long-billed Curlew]

As one ornithologist* says, “The beach is a great place to visit, but you wouldn’t want to raise a family there.” So, because curlews depend on very different breeding and wintering environments, changes in either habitat affect them.

The Nature Conservancy and American Bird Conservancy are protecting habitat in the prairies of Montana, and in Mexico, they’re working closely with Pronatura Noreste (pronounced nor-es-tay). The goal is to keep the beautiful song of the curlew in our spring skies…

[Display song of Long-billed Curlew]

…and that long, curved bill on the beach in winter.

[Flight/alarm calls of Long-billed Curlew].

I’m Mary McCann.

###

Written by Dennis Paulson

Sounds of the Long-billed Curlew provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Display call recorded by R.S. Little; flight call by G.A. Keller;

Flight call at beach recorded by Martyn Stewart of naturesound.org

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson / Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org May 2015 Narrator: Mary McCann

* The ornithologist is Dr. Dennis Paulson.

Curlew in flight - Jerry Kirkhart https://www.flickr.com/photos/jkirkhart35/4015923888/

Curlew in grass - Bryant Olsen https://www.flickr.com/photos/bryanto/4518324806

Curlew on the beach - Ken Schneider https://www.flickr.com/photos/zonotrichia/5995659161

http://birdnote.org/show/long-billed-curlew-singing-over-grassland

CURWOOD: You can find pictures if you soar on over to our website, LOE.org.

Long-billed Curlew nest on grasslands, but prefer southern shores in winter. (Photo: Bryant Olsen)

Related links:

- BirdNote

- More about the Long-billed Curlew

- Status Assessment and Conservation Action Plan for the Long-billed Curlew

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck Stomping Grounds, Bela Fleck and the Flektones, Greatest Hits of the 20th Century, Warner Bros Records 1999]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, James Curwood, and Jennifer Marquis. And we’re happy to have a new intern this week – Shannon Kelleher. Our show was engineered by Tom Tiger, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Additional production assistance came from Cottage Recording in Helena, Montana. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. The Kendeda Fund, furthering the values that contribute to a healthy planet, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change. Living on Earth is also supported by Stonyfield Farm, makers of organic yogurt, smoothies and more. www.stonyfield.com.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth