November 27, 2015

Air Date: November 27, 2015

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Almost Out of Time

View the page for this story

Back in the 1970s, NASA scientist James Hansen was one of the first to recognize the dangerous impacts that rising levels of greenhouse gas emissions could have on the earth’s climate. Now this climate scientist has become an activist in the climate movement, lending his scientific voice to calls for urgent action. On the eve of the UN’s Paris climate summit, he tells host Steve Curwood that emissions reductions need to be much steeper than those being discussed. (12:00)

Paving the Path to Paris with Gold

View the page for this story

Around the world, both public and private sources are promising to fund action on climate change, and help vulnerable nations adapt to and mitigate the effects of global warming. An important source of support is the World Bank. Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer spoke with Rachel Kyte, the Bank’s Special Envoy for Climate Change, about the sources and aims of the available finance. (07:55)

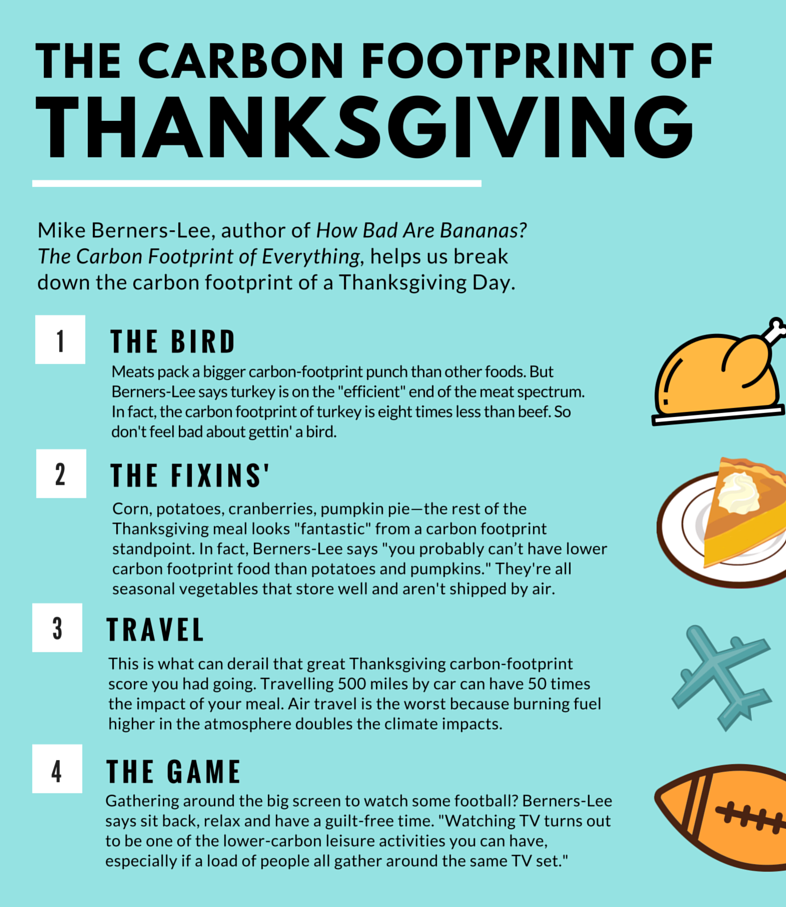

What is the Carbon Footprint of a Typical Thanksgiving?

/ Lou BlouinView the page for this story

Each year, Americans travel across the country to share feasts with family and friends, and all of this consumption comes at a cost to the climate. The Allegheny Front's Lou Blouin investigates the carbon footprint of Thanksgiving. (04:15)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week’s trip beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra tells host Steve Curwood about some of the things he’s thankful for: US parks and the 35th anniversary of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, the destruction of chemical weapons, and the Freedom of Information Act, which has helped improve government transparency over climate and environmental issues. (04:15)

What We’re Fighting For Now Is Each Other

View the page for this story

Wen Stephenson was a moderate liberal and a journalist with NPR before an epiphany about global warming changed everything. Wen speaks with host Steve Curwood about his journey into the climate movement, and his new book about activists on the frontlines of the fight for climate justice. (16:05)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: James Hansen, Rachel Kyte, Wen Stephenson

REPORTERS: Lou Blouin, Peter Dykstra

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. As negotiators and heads of state and government converge on Paris for the crucial UN Climate summit, a warning from one of the first scientists to raise the alarm on greenhouse gases – former NASA researcher James Hansen.

HANSEN: We don't know whether we've passed a point where we're going to lose, for example, the west Antarctic ice sheet. If we do, that means sea level rise of several meters.

CURWOOD: How Paris could counter the threat. Also, counting up the carbon footprint of the Thanksgiving feast, and that plate piled high with stuffing, roast potatoes and pumpkin.

BERNERS-LEE: So, they’re seasonal vegetables, and they keep well. And you don’t have to do anything crazy like put them on an airplane, so they’re fantastic. In fact you probably can’t have lower carbon footprint food than potatoes and pumpkins.

CURWOOD: Food, climate and more this week, on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In a Beautiful Place Out in the Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies – innovating to make the world a better, more sustainable place to live.

Almost Out of Time

Hansen was arrested in front of the White House in 2011. (Photo: chesapeakeclimate, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. Paris is the host for the UN climate summit starting November 30th. Diplomats are determined to put the failure of the last major session six years ago in Copenhagen behind them. Christiana Figueres, the Executive Secretary of the UN climate convention, says thanks to hard work, virtually all the world leaders have gotten aboard.

FIGUERES: This time it is 194 governments, all of whom, consistently—for the past four years since they decided that they would come to an agreement—have actually been marching down the path. Consistently, slowly, yes because this is not an easy process, but consistently down the path toward an agreement, and we are actually on track or in fact they’re even ahead of schedule with the milestones they had imposed upon themselves.

CURWOOD: So much is likely to be achieved in Paris, but some scientists point out that even more will have to done to keep the planet from sliding into climate chaos. To get some perspective, I spoke with one of the first scientists to sound the alarm about the dangers of rising levels of atmospheric CO2, James Hansen of Columbia University, who worked for NASA.

HANSEN: Well, back in the 1970s if you remember that was the time of the chlorofluorocarbons and the ozone problem where it was realized that humans were changing the atmosphere, and what was a concern then was the fact that loss of ozone could mean more skin cancer. But my interest was, well, what about the effect of that on climate? So I proposed to NASA that we would look at that question, we would need to build a climate model, and at that time I was actually principal investigator on an experiment that was being built to go to the planet Venus to study the clouds of Venus. But my proposal was accepted, and I began to work on building a climate model. And that became so engrossing that I resigned as the PI on the Venus experiment and began to devote 100 percent of my time to climate. And, of course, it wasn't just ozone, it’s carbon dioxide and methane and nitrous oxide. Humans are changing a number of gases in the Earth's atmosphere, and that becomes a really big issue. And it became clear way back then.

James Hansen testifying before Congress back in the 1980s. (Photo: NASA, public domain)

CURWOOD: How did you feel when you realized that, OK, us humans we actually could change the climate on this planet?

HANSEN: Yeah, well that was why I switched from Venus to Earth, because there are people living on this planet so it makes a difference. I remember remarking to my friend Andy Lacis, "Gee, this is really going to be interesting before our scientific careers are over, we should actually see the climate change because that's what we computed in our models." And it was pretty straightforward that the signal should rise out of the noise within the next few decades, and by the early parts of the 21st century even the public should begin to notice. But of course the real issue is what's going to happen from now on because so far the climate change is relatively modest. We're beginning to see effects. The frequency of extreme events is increasing, but the potential for what will happen several decades in the future during the lifetime of young people is much greater. It's possible that we could push the system beyond tipping points so that young people cannot control the outcome several decades downstream.

CURWOOD: How close to the edge are we now, do you think?

HANSEN: Well that's the $64 question. We don't know whether we've passed a point where we're going to lose, for example, the west Antarctic ice sheet. If we do, that means sea level rise of several meters. We know that we're getting very close if we're not there yet, and that's why it's crucial that we begin to phase down fossil fuel emissions rapidly or we surely will pass that tipping point.

CURWOOD: How quickly could things change? How abrupt might climate disruption arrive?

HANSEN: That depends on what climate disruption you're talking about, but the one that I am most concerned about is disintegration of the ice sheets and sea level rise. And there, I would argue that we could very well get large changes by the second half of the present century, which would mean just 35 years from now, and 35 to 85 years from now. Because if we look at Greenland and Antarctica, we see that they are beginning to shed mass and shedding it at a faster and faster rate, and I argue that it is likely to be a very nonlinear process. That's the big issue now. We don't have models for ice sheets that we can trust to give us an accurate prediction for how soon we can get multi-meter sea level rise, but if we look at the Earth's history we know that there've been numerous times when sea level went up several meters in the century—and that's what we can't let happen—because that would mean all of the history associated with all of our coastal cities would be lost. But it's more than that, it's the economic implications of that are practically incalculable. We've got more than half of the large cities of the world located on a coastline, so we just can't let that happen.

An iceberg off West Antarctica. Hansen says the melting West Antarctic Ice Sheet could mark a tipping point from which the climate cannot recover. (Photo: NASA CC BY-ND-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: By the middle of December, negotiators in Paris are excited to come up with a international binding deal to address climate disruption. They say the stated target is two degrees Centigrade increase or about three and a half degrees Fahrenheit. What you think of that target?

HANSEN: Well, we know that that's not a sensible target because if we look at the Earth's history, the last time it was two degrees warmer than preindustrial [times]...two degrees Celsius warmer was the Eemian [period]. Sea level was then six to eight meters higher than it is now, so why would we set that as a target? That doesn't make sense. It was picked out of a hat simply because people thought, well, that's probably the best we can hope for because we've already got almost one degree of warming. And we know there's more in the pipeline, and it's very difficult to move off of our present largest energy source, which is fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: So what you're saying is that the two degrees Celsius target essentially lines us up for—round numbers—about 20 feet more sea level?

HANSEN: Yeah, the Earth's history tells us that two degrees Celsius warming over preindustrial [times] would end up eventually with the sea level 6 to 8 meters higher. We can't say exactly how fast that would occur, but we know that it would occur. We just don't know which generation is going to be feeling the full effects, but if we look at the ice sheets now and see how rapidly they're beginning to change, it looks to me like it's going to be our children and grandchildren, not some tenth generation in the future.

CURWOOD: So what's the solution? What would you do if you were in charge?

HANSEN: You know, it's really simple. We just have to make the price of fossil fuels honest. We should add a fee to oil, gas, coal. You collect the fee from the fossil fuel company at the source: the domestic mine or the port of entry, and 100 percent of that money should be given to the public. It should not be taken by the government to make the government bigger. Instead, give an equal amount to every legal resident of the country. That way, the person who does better-than-average in limiting their fossil fuel use will actually make money. With the present distribution of energy use among the public, two-thirds of the people would actually come out ahead. Very wealthy people who have big houses and fly around the world would pay more in their increased prices than they get in the dividend, but they can afford that. So that's the way you would...and you do this gradually; you don't suddenly add a big fee. You add something each year; increase it each year. That gives the public a chance to make changes. The next time they get a vehicle, they can consider getting a more efficient one. Economic studies show that that would work, and it would make the United States more competitive with other countries. If we're an early adapter of this type of policy, we would begin to move our industry and begin to take advantage of our entrepreneurs developing low carbon energy sources. So it actually makes sense, but the only problem is that our capitals all around the world are heavily under the influence of the fossil fuel industry. We have well-oiled, coal-fired senators and representatives who continue to vote for the industry over the interests of the public.

USGS scientists track glacial melting in Alaska. (Photo: USGS, public domain)

CURWOOD: You've been part of the climate activism movement now for a while. What comes next for that?

HANSEN: What activists need to understand is the same thing that we're trying to get the public to understand, and that is that you can't solve the problem just by protesting against the bad things. We have to actually make it clear that there is a solution that makes economic sense, and which will actually make the public better off. We have to put pressure on the governments to actually do something significant at Paris. Right now, it doesn't look like they are planning to do that; it looks like they're planning to clap each other on the back and say, "Oh, we all have agreed that we're going to do better." Well, that's not going to do it. What we actually need is an agreement to have a rising carbon fee, and frankly you're not going to get that at a table where you have 180, 190 countries sitting around the table. It is going to require an agreement between two or three of the major players, and the major players are United States, China and the European Union. It looks unlikely that the European Union is going to propose anything sensible. They still have this idea of this half-baked cap-and-trade with offsets—the Kyoto Protocol approach, which was totally ineffectual. What we actually need is a simple honest rising carbon fee, and I think that it's very possible that China would be willing to come to such an agreement because they have a huge problem with air pollution and with climate change, and they know climate change is real. And they have more than 300 million people living near sea level, so they will want to solve this problem. And the best way for them to phase down their dirty emissions is to begin to move to clean energies, and the best way to do that is by making the market help move away from fossil fuels onto clean energies.

CURWOOD: James Hansen is a pioneering climate scientist formally with NASA now Columbia University. Thank you so much.

HANSEN: Well thank you.

Related links:

- James Hansen is a professor at Columbia University

- A paper Hansen co-authored on the dangers of the 2 degree Celsius goal

- James Hansen’s new climate study is terrifying, but he still has hope

[MUSIC: Youssou N’Dour “This Dream”, Joko (The Link), Nonesuch]

CURWOOD: Just ahead...the changing focus of the World Bank in a warming world. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Phoenix “Honeymoon”, United 2000, Source/Parlophone]

Paving the Path to Paris with Gold

Climate change threatens to put as many as 100 million people back into poverty by 2030, according to a recent World Bank estimate. (Photo: Curt Carnemark / World Bank, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. The World Bank finances major infrastructure for developing countries with a primary focus on reducing poverty. And in recent years the World Bank has recognized the need to address climate change and has stopped lending money for coal-fired power plants. Rachel Kyte is now the World Bank’s special envoy for climate change, and she recently spoke with Living on Earth’s Helen Palmer.

PALMER: Rachel Kyte, you're the vice president and special envoy for climate at the World Bank. Tell me first of all, we're just about to go into Paris, where we at in terms of getting the kind of agreement we need?

KYTE: Well, I think we're in a quite interesting position because there is an extraordinary momentum around climate action from initiatives being announced on almost a daily basis from the private sector to different initiatives of governments; civil societies mobilized—there are people walking from every corner of the Earth towards Paris. And then there's the negotiation process, which is always inextricably difficult and which some people have deep concerns that there's far too much text, which is still undecided. But we have to at this point rely upon the diligence and the craft of the French as hosts of the COP in terms of shepherding the diplomacy forward, but at the same time, the decision to bring heads of state at the beginning rather than at the end is an extraordinary signal that the political space for negotiators to not focus on an ambitious text has been removed.

PALMER: So, that's what they're doing right in Paris, bringing people in the beginning? They've also got some pre-agreements that seem very strong.

KYTE: Yes, so the heads of state will be in Paris on the opening day, and I would expect to see some very strongly-worded, declarative statements from the heads of state with a clear signal that these are leaders that are prepared to lead. And in the run-up, we have a G-20; we have a commonwealth heads of government meeting as well. We have bilateral diplomacy with the French and others traveling the world. It's an extraordinary diplomatic effort of the like of which we haven't seen before.

PALMER: So, do you think we all going to end up with a strong actual agreement at the end of Paris?

KYTE: So we're going to end up with a package deal, and the package deal will include a negotiated text and I hope that that's a strong and ambitious text but it's too early to tell. There will be some kind of critical declaration, which I believe will speak clearly to the rest of the world and to the global markets—in terms of, this is the direction of travel and this is where you should be thinking about investing for the future. We will be see remarkable commitments to action from a number of working coalitions of public and private sectors working together on specific issues as part of an action plan, and there will be a financial package. Underpinning all of that is what they call these intended nationally determined contributions, which is a bottom-up—as opposed to a top-down—process where every country has filed with the UN basically a first generation investment prospectus for low carbon growth.

PALMER: The working parties...these are about what kind of issues?

KYTE: So these coalitions of the working, as we call them, coalitions of the willing—having different connotations—are really where a number of governments and companies from across different sectors of industry and civil society got together and said, "look, this is an issue that really needs to move forward. We need to act on this, and we're not going to or can't wait for an emerging consensus to come." So whether it's on short-lived climate pollutants, black carbon, methane, hydrofluorocarbons and the clean air coalition that grew up around that...forestry, tropical forest alliance, all kinds of companies with extended supply chains saying, “We are going to end deforestation in the supply chain no matter what the REDD and REDD plus agreement says in the convention, sustainable energy for all. More than 80 countries and thousands of other groups and companies coming together and saying, “We're going to deliver clean energy. We're going to increase the amounts renewables in the mix, and we're going to have a revolution in energy efficiency.” So there are across a spectrum of issues often outside of the convention these remarkable working coalitions now formed and making very substantial pledges.

By 2020, the World Bank expects to channel $29 billion into climate finance every year, funding renewable energy projects, adaptation, and more. (Photo: World Bank, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

PALMER: What's the role of the World Bank in all this?

KYTE: We're very pleased to be a partner in many of these coalitions. We see how climate change is threatening our underlying mission to end poverty and build prosperity. And so responding to our clients needs—developing countries and private sector—we've had to completely rethink the way we do our business. At the same time, we are a very important channel of climate finance and recently agreed to increase by 40 percent our financing, so that we, by 2020, expect to channel $29 billion worth of public finance every year. This is actually a separate channel from the Green Climate Fund. So if you look at what's flowing today, the OECD has estimated that's $62 billion dollars flowing every year. Probably half of that comes through different multinational development banks including the World Bank group, and then there's the $10 billion in the Green Climate Fund, but not all of that is flowing yet. So the Green Climate Fund like any financial situation is slowly getting off the mark and has just last week making its first commitments of financings, different projects. I think what we need is climate finance to flow. We need development finance to be climate smart, and we need of all that to leverage private co-financing.

PALMER: It still leaves out the adaptation part. Do you expect there will be a robust agreement on adaptation at Paris?

KYTE: I think that from the financial perspective, the minority of that $62 billion dollars is going into adaptation, and so I think there are two immediate issues: One is how to make sure that more climate finance goes into adaption, and then remember that everything we're negotiating in Paris is for 2020 on. This is 2015. We have an immediate need to boost financing into resilience and adaptation now over the next five years because we know that the climate impacts are going to become more and more profound every year. We are going to lose lives, and we're going to lose enormous amounts of GDP growth. And so every investment that we can make in resilience will save us funding in relief and reconstruction but it will save us lives too.

Rachel Kyte is World Bank Group Vice President and Special Envoy for Climate Change. (Photo: World Bank Group)

PALMER: The World Bank very recently released a report that said it expected another hundred million people in severe poverty by 2030 as a result of climate change. Do you think this is something that can be diverted?

KYTE: We're in the business of solutions working with our clients, and so we believe that the kind of aggressive action to mitigate climate change and concentrated investment in adaptation can make those numbers a distant threat rather than a reality. This means that countries have to do the things that are not rocket science and the need to do them soon and need to do them well. So, we want to see carbon prices in all economies. We want to see the harmful subsidies removed in both fossil fuels and agriculture. We want to see smart economic management with long-term consistent signals that will allow the private sector and public procurement to move into lower carbon solutions. It's not easy. No country has ever walked this path before, but a lot of the tools that are needed are available to government already, and it requires political will to use them.

CURWOOD: Rachel Kyte, World Bank's special envoy for climate change speaking with Living on Earth's Helen Palmer.

Related links:

- World Bank on climate finance

- Intended Nationally Determined Contributions

- Green Climate Fund

- World Bank warns climate change could add 100 million poor by 2030

- The Climate Financing Senate Republicans Have Pledged To Block Is Key To The Paris Climate Talks

- OECD on financing climate change action

- About Rachel Kyte with the World Bank

[MUSIC: J.S. Bach, “Var. 5 A 1 Overro 2 Clav.,” performed by Simone Dinnerstein on Bach: Goldberg Variations (Telarc 2007)]

What is the Carbon Footprint of a Typical Thanksgiving?

The traditional Thanksgiving Day meal might be a belt-buster, but it won't bust your carbon footprint score. (Photo: Jack Amick, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: By now, many of us are contemplating that Thanksgiving turkey in the rear view mirror; maybe we’ve even finished the leftovers. And perhaps we vow we won’t indulge quite as much next year. Well, that plate piled high with turkey and trimmings doesn’t only come at the expense of our waistline; it also has somewhat of a carbon footprint, as does the trip back home by car or air. So reporter Lou Blouin of the Allegheny Front has been investigating what exactly is the carbon cost of that Thanksgiving feast.

BLOUIN: Turns out the guy who may know the most about the carbon footprint of an American Thanksgiving, hasn't ever experienced one himself.

BERNERS-LEE: I haven't actually. Although it doesn't look all that dissimilar from our Christmas dinner in the UK.

BLOUIN: This is Mike Berners-Lee, and he's considered one of the world's leading experts on carbon footprint of, well, everything. In fact, he wrote a book subtitled, the "Carbon Footprint of Everything". So earlier this week, I phoned him at his office in the UK to talk a little turkey.

BERNERS-LEE: Yeah, Sure, Ok. Well, turkey is a meat, and most of the time the thing to say about meats is that they’re quite inefficient way of having nutrition. But having said that, chickens and turkeys are very much at the efficient end of the meat spectrum.

BLOUIN: That’s because a Thanksgiving turkey can go from egg to a bird that’s 20 pounds or more in just 14 weeks. So they’re not really on the planet long enough to make that big an impact. And it turns out it doesn't even matter all that much if you go with a local bird, which only has to ship from the farmer down the road.

BERNERS-LEE: Well, it matters a bit, but it would still be fairly small compared to the actual footprint of growing the animal in the first place.

BLOUIN: In fact, Berners-Lee says transportation might only account for about 25 percent of the turkey’s total carbon footprint, assuming it’s not shipping by air. But bottom line—having a turkey on your Thanksgiving table is not all that bad. And the same goes for corn, potatoes, cranberries, pumpkins and a lot of the other foods that end up on your plate.

BERNERS-LEE: So, they’re seasonal vegetables, and they keep well. And you don’t have to do anything crazy like put them on an airplane. So they’re fantastic. In fact you probably can’t have lower carbon footprint food than potatoes and pumpkins.

BLOUIN: So all in all, the Thanksgiving dinner looks pretty good from a carbon footprint standpoint. That is, if you go traditional.

KRAUSS: Yeah, so, okay. This year is a little bit different. Little bit of a curveball. But there is no turkey.

BLOUIN: This WESA reporter Margaret Krauss. She agreed to let us dissect the carbon footprint of her Thanksgiving plans, which are still kind of coming together.

KRAUSS: There is a meat that will be grilled outside: maybe we’re doing bratwurst. Maybe we’re doing chicken. Maybe we’re doing steak?

BLOUIN: Whatever she decides to cook, it sounds like it’s going to be a bit of a fire drill. The plan is to get on a plane, and on Wednesday night, hit the supermarket to pick up some supplies when she lands.

KRAUSS: So check this: I’m getting on a bus that will take me to the airport that will take me to Minneapolis that will take to Salt Lake City, and then driving from Salt Lake City to Provo, Utah.

BLOUIN: So all in all a pretty big trip, and that—along with the alternative menu—could get Margaret into trouble according to Mike Berners-Lee.

BERNERS-LEE: Well yeah, red meats are a quite a lot less efficient. The carbon footprint of beef would be about 24 kilos of carbon dioxide equivalent per kilo of beef, whereas for turkey, it’d be nearer three.

BLOUIN: And the air travel is a real killer.

BERNERS-LEE: So a Boeing 747 will get through—I can’t remember the exact number off the top of my head—but it’s 100 and something tons of fuel per trip. So you end up with an enormous carbon footprint shared out between the passengers. And your friend has to take a few tons of it on the chin.

BLOUIN: Even worse, Berners-Lee says the fact that the fuel is burning higher up in the atmosphere doubles the climate impacts. So drive if you can, better yet, take a train. But how does the carbon footprint of Thanksgiving travel stack up against Thanksgiving meal? Well, Berners-Lee did a quick calculation on my 500-mile trip back to Michigan by car.

BERNERS-LEE: So you’re going through about 50 liters of gas, so that would be the same carbon footprint of turning up and finding your way through 50 kilos of turkey, which would be quite an achievement.

BLOUIN: Yeah; no way that’s happening, even with leftovers. And at my house, my mom has a pretty energy-efficient way for storing those. When the fridge fills up, as long as the Michigan fall weather is cooperating, she puts the turkey in her car too keep it cold. Pretty sure that method is keeping the planet safe from harm. Not sure I can say the same for us. I’m Lou Blouin.

CURWOOD: Lou Blouin reports for the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- More about food and the environment on The Allegheny Front

- How Bad Are Bananas?: The Carbon Footprint of Everything

- Beef environment cost 10 times that of other livestock

- The tricky truth about food miles

- Food Waste Is Becoming Serious Economic and Environmental Issue, Report Says

[MUSIC: Tennessee Mafia Jug Band “Turkey In The Straw, Music City Roots live from the Loveless Café on 5.11.2011]

Beyond the Headlines

Denali, formerly Mount McKinley, is the highest mountain peak in North America. It’s part of the Denali National Park and Preserve, which is part a wider system of state and national parks. (Photo: Nic McPhee, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time to discover what’s going on beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra of the DailyClimate dot org and ehn dot org, Environmental Health News. We check in with him most every week, and he’s on the line from Conyers, Georgia. Hi, there Peter.

DYKSTRA: Well, hi Steve. You know, I love the discussions we have each week, but one of the pitfalls of environmental news is that so often, it’s just bleak news. So since it’s Thanksgiving time, I’m going to focus on three things to be thankful for that reach back into history and also have great meaning for our present and our future.

CURWOOD: Sounds like a plan. There’s always room at the table for positive things.

DYKSTRA: OK, we’ll start with parks. From wilderness areas to pocket parks in urban neighborhoods, they’re a real salvation. And this week marks the 35th anniversary of one of the biggest developments in U.S. Park history: the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, which pretty much doubled the protected acreage in the U.S. thanks to Congress and a stroke of Jimmy Carter’s presidential pen.

CURWOOD: Well now that’s an anniversary to be thankful for, but I’m not sure the current Congress is really getting with the program on the value of nature.

Aerial View Johnston Island as seen from northeast, approaching runway. Western part of Sand Island can be seen on the right side. (Photo: Gerald Ludwig, USFWS, public domain)

DYKSTRA: Fair enough, but right now the action to protect wild places is focused on the ocean. The U.S., U.K., New Zealand and Chile have all taken major steps to create marine protected areas recently. Thanks to everyone who makes parks special from the vast preserves of ocean and wilderness to the little parks in our neighborhoods. And now, a word of thanks regarding chemical weapons.

CURWOOD: Well, wait, I’m not exactly sure I want to thank chemical weapons, Peter. Please explain.

DYKSTRA: Well I’m thankful for the progress that’s been made getting rid of them. It was fifteen years ago this week that destruction of the huge U.S. chemical weapons stockpile at Johnston Atoll in the Pacific wrapped up: nerve gas, sarin, mustard gas, and other barbaric weapons of war incinerated to comply with the international and congressional agreements. There was some concern that even the act of destroying chemical weapons would pose a big risk, but though they haven’t always stuck to their commitments, most of the world’s nations have foresworn their use, manufacture and storage.

CURWOOD: And Johnston Atoll was a particularly bad place to store them with the advancing threat of sea level rise.

DYKSTRA: Right and here’s something else that’s thankfully cool: After decades of intensive military use and chemical weapons storage, Johnston Atoll is now part of one of those marine sanctuaries.

CURWOOD: So are we about to go three for three on thankfulness? What’s next?

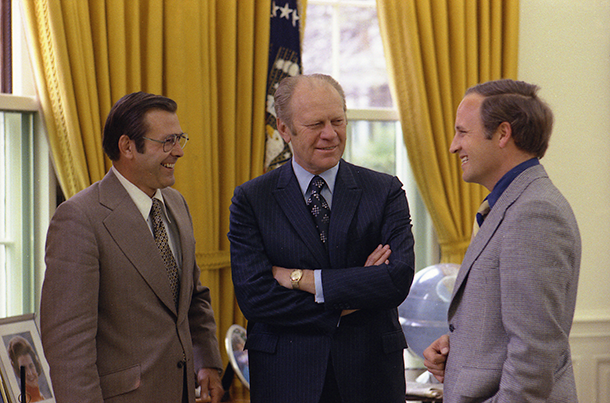

DYKSTRA: I want to tell you a little story about FOIA: The U.S. Freedom of Information Act. The original act was passed in 1966, pretty much a weaker version of today’s law, and one of its most enthusiastic sponsors was a young Republican Congressman from Illinois named Donald Rumsfeld. He was eager for a way to keep the Democrats in Lyndon Johnson’s administration accountable. But soon federal agencies found ways to thwart public information requests or keep them on hold for months. By 1974 in the wake of the Watergate scandal, Congress improved and strengthened the Freedom of Information Act, but President Ford vetoed the bill, egged on by his chief of staff who was Donald Rumsfeld.

Chief of Staff Rumsfeld (left) and Deputy-Chief of Staff Dick Cheney (right) meet with President Ford, April 1975 (Photo: David Hume Kennerly, Wikimedia Commons public domain)

CURWOOD: So he was for FOIA before he was against it, right?

DYKSTRA: That’s right. And Congress overrode the Presidential veto, and FOIA became the law that allowed a reporter named Karen Dorn Steele to uncover the massive pollution at U.S. nuclear weapons plants in the 1980s, and activists at the Climate Investigations Center to discover some eyebrow-raising financial conflicts in the funding of a researcher, Willie Soon, whose work casts doubt on mainstream climate science earlier this year.

CURWOOD: But FOIA’s far from a perfect transparency weapon.

DYKSTRA: Very far from it. Those embarrassing revelations about Willie Soon took more than five years to produce, and federally-funded climate scientists say that political operatives have learned how to exploit the law to harass them, filing enormous requests that cause climate research to stop while scientists collate tens of thousands of pages of documents. And it’s still not too difficult for government agencies to sandbag even the most appropriate FOIA requests. So let’s be thankful for a potent but imperfect good government law like the Freedom of Information Act as a citizen’s tool to try to keep the government honest.

CURWOOD: Well, ‘tis the season to be thankful – so thanks Peter – Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and the DailyClimate.org. We’ll talk again when we get back from the climate conference in Paris.

DYKSTRA: Alright. Thanks a lot, Steve. Have fun in Paris.

CURWOOD: And there’s more on these stories at our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980

- Johnston Atoll is part of a US marine national monument

- Freedom of Information Act 1966

- Veto battle over strengthening the Freedom of Information Act

[MUSIC: Bing Crosby “I’ve Got Plenty to be Thankful For”, Holiday Inn, 1962, UMG recordings]

CURWOOD: Coming up...channeling Henry David Thoreau in the quest for climate justice. That's just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from United Technologies, a provider to the aerospace and building systems industries worldwide. UTC Building & Industrial Systems provides building technologies and supplies container refrigeration systems that transport and preserve food and medicine with brands such as Otis, Carrier, Chubb, Edwards and Kidde. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Vince Guaraldi “Little Bird” From Charlie Brown Thanksgiving (1973), From Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, 2008, D&D Records]

What We’re Fighting For Now Is Each Other

What We're Fighting for Now Is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice (Photo: Beacon Press)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood. As we noted earlier, at the moment all roads lead to Paris for many passionate about climate protection, including writer Wen Stephenson.

STEPHENSON: I'm a father of two young children, a 15-year-old son and a now 11-year-old daughter, and when I thought about this situation and the world that they are growing up into, and what this planet may be like within their lifetime, it really lit a fire under me.

CURWOOD: But the concerns of Wen Stephenson go beyond his own children. He also sees climate disruption through the lens of the billions who didn’t create the global warming problem but who are on the front lines of suffering. A former journalist, he has turned into a climate activist, and published a book called What We’re Fighting for Now is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice.

STEPHENSON: There wasn't any one moment I don't think, when I realized I needed to take this leap into activism anymore than there's sort of a single moment when night turns to day. But in late 2009, we the UN negotiations in Copenhagen fail, and a lot of people felt that this was a make or break moment for the planet. And I was watching that very closely. And then in the spring of 2010, it became clear that even very weak bipartisan climate legislation in the U.S. senate was going to fail as well. And this was at a moment in my own life when I had recently left my last job, which was as the Senior Producer of NPR's On Point, and in that spring as I was looking for what to do next—I wanted to start writing again—and it was at that moment in that spring of 2010, that I had my kind of holy crap moment on climate change and realized that look we're not dealing with this. And I decided that I couldn't imagine getting up in the morning and working on anything else, especially someone in my position with my privilege, I had the ability at that moment to decide how to spend the rest of my life. I decided this is was the thing.

Wen Stephenson says that religion has played an important role in the rise of a stronger, more confrontational climate movement. (Photo: Mat McDermott, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: The preface of your book and let me quote, "This book represents no more or no less than my own search for the moral and spiritual wellsprings of that kind of courage and commitment and my search for that the very idea of climate justice."

STEPHENSON: Yeah.

CURWOOD: And in your book your search for courage and commitment on the climate movement starts with personal reflection and a meditation on Henry David Thoreau. Henry David Thoreau, of course famous for writing Walden, famous for living out there, probably little less well-known—as you point out in your book—for being really active as an abolitionist. What of Thoreau's story inspired you?

STEPHENSON: So what I realized, around this time in my life, I had started taking walks around some really beautiful conservation land around near where I live. I live in Wayland, Mass., which is west of Boston and just down the road from Walden Pond really. My house is about five or six miles south of Walden Pond, and that was one of the places that I occasionally would walk. In fact, one time I decided to get up early on a Saturday morning and walk to Walden Pond. But it really didn't have much to do with Henry David Thoreau at that point. It was just for the sake of walking, but when I had my climate freak out moment in the spring of 2010, I decided to go back to Thoreau. And the thing I realized as I went back and reread Walden, read his great essays, is that not only is Henry David Thoreau really a deeply spiritual writer—something I never really thought about before. On top of that, Henry Thoreau, who is sort of this icon of the American environmental movement, was not an “environmentalist”, you know, quote unquote. That word would've meant nothing to him, but what he was, unquestionably, was a radical abolitionist. He was a human rights activist. He was deeply involved in the underground railroad along with his mother and his sisters. He personally sheltered runaway slaves defying the fugitive slave law there in the early 1850s. At one point, he even spirited an accomplice of John Brown's Harpers Ferry raid. And this is at no small risk personally to Thoreau. This man, he was smuggling out of Concord had a price on his head. And so the way I think of it, the way I articulate this in the book is that Thoreau's very spiritual awakening in nature really led him back to society and to a very radical political engagement on behalf of his fellow human beings. And so as I like to think of it, as I put it, for Henry Thoreau to live in harmony with nature, so to speak, really is to act in solidarity with one's fellow human beings because the two can't really be separated.

Earlier this year, kayaktivists protested Shell’s oil and gas exploration in the Arctic, in an effort to keep fossil fuels in the ground. Since then, Shell has abandoned their plans. (Photo: Backbone Campaign, CC BY-2.0)

CURWOOD: Wen, tell me, what's the difference between climate justice to you now and, say, environmentalism?

STEPHENSON: Right. Right. Well, there shouldn't really be any difference, honestly. For someone like Henry Thoreau as I was just saying there really wasn't; there wouldn't be any difference. He would see them as all the same. But there are those even in the climate movement—certainly plenty of policy experts and people working on this at a political level in Washington—who don't really like to talk about justice. I mean, they don't really want to talk about race or inequality. They don't want talk about the distribution of wealth, whether at the national level or much less at the global level where Pope Francis has reminded us [that] we owe the developing world—the majority of the world's people—an enormous debt, a sort of climate debt or ecological debt. They don't really want to talk about these things because they're politically inconvenient, and I don't really want to talk about these things either because it's hard to talk about structural forms of oppression that are at the root of this crisis and that prevent us from really honestly addressing it. But, you know, if I'm serious about this, if I'm serious about justice, if I'm serious about climate, morally serious about it, then I have to face these things. And I think we do as a country.

CURWOOD: Your book is structured both with your own personal epiphany and how you've dealt with that, but then you go ahead to tell the story of climate activists and you compare them to the abolitionists, the folks who struck out in such a radical way to fight slavery. In what way do you consider climate justice activists the new abolitionists?

STEPHENSON: Right. Well, I think first it's a really important for me to say, as I try to make crystal clear in the book, that I'm not comparing climate change to slavery, which would be perverse. What I am doing is drawing inspiration from the abolitionists and from the abolitionist movement. I'm saying that our situation calls for a movement that’s every bit as radical and resolute morally and even spiritually as that movement and other radical human rights movements, you know, in our history. The narrative arc of my personal story is really that of going from a kind of self absorption, I guess, to engagement, and it's sort of about the radicalization of a privileged, white, mainstream center-left liberal, ok? And there's an analogy in that narrative to what needs to happen socially and politically here in this country, because what has happen is a kind of radicalization of the mainstream. And when I say “radical” I mean that at this hour, at this late hour, to be serious about climate is to be radical, because it's really a radical situation, you know, and it requires us to go to the root, the root of the systems that have created this. That's not going to happen until enough people really come to terms with and face up to the really radical nature of the situation. And historically—so to take it back to the abolitionists—I mean, historically this is the only way that really deep revolutionary changes have happened in this country is when ideas and principles and demands that were once considered radical and extreme: the freedom of African-Americans for example. When these became mainstream because radicals went out and forced the issue, right, whether it was on abolition or women's rights or labor rights or civil rights, gay liberation, marriage equality, all of these human rights struggles. Radicals have forced them into the mainstream consciousness and brought about a kind of moral reckoning in our society.

CURWOOD: You profile a number of people in your book who have gone through that process. Let's talk about some here. Perhaps we could begin with Tim DeChristopher.

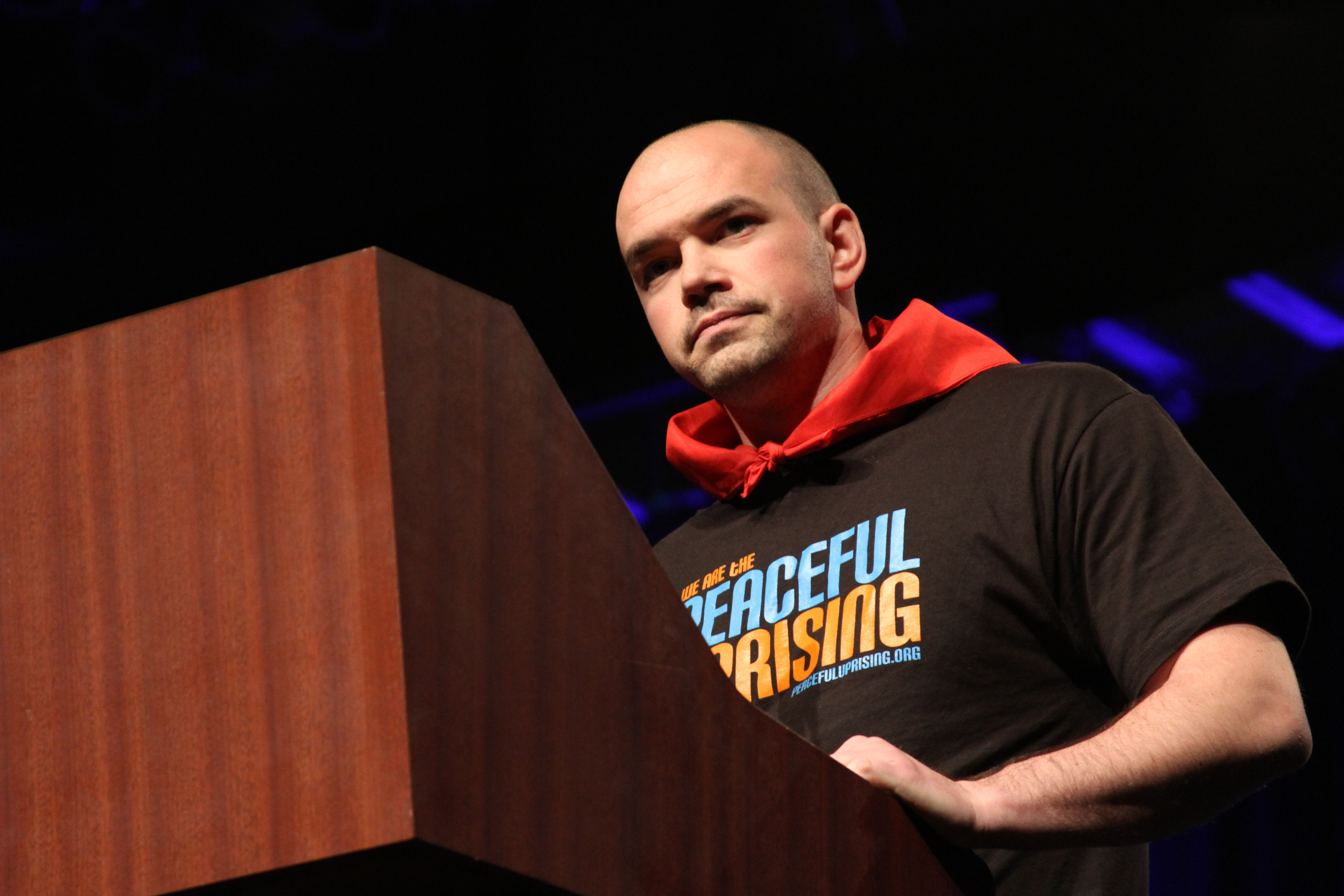

Climate activist Tim DeChristopher bid on oil and gas leases on public lands in the West in an act of civil disobedience that sent him to jail and helped galvanize the climate activism movement. (Photo: Linh Do, Flickr CC BY-2.0)

STEPHENSON: Absolutely. In 2008, Tim was an economics student at the University of Utah. He had had his own very profound kind of awakening to the climate crisis, and Tim found out about a Bureau of Land Management auction that was going to take place in Salt Lake City in which leases to drill for oil and gas on public land in southern Utah were going to be auctioned off. And so he decided to go to this auction and join a protest outside because this issue of drilling leases on public land is certainly a big environmental issue. And went down there, and he had been preparing himself for a while to take some kind of bolder, more confrontational action. And he gets down there, and there is this little protest going on outside, people walking around holding signs, and it was very tame. He decided to try to get inside the auction and they asked him as he walks up, "Sir, are you here for the auction?" He says, "Yes. Yes, I am." And then he goes over to this table and they ask him, "So are you here to be a bidder?" And he says, "Yes. Yes, I am." And they register him as bidder number 70, and he goes into the auction, and he's sitting there watching these parcels of public land being auctioned off at bargain basement prices basically given away to oil and gas companies, and he decides to take action. He starts raising his paddle, and he starts actually winning bids for parcels of land until finally he's won bids for thousands of acres worth about almost $2 million dollars that he of course has no way of paying. And so he's arrested. He goes to trial and he's ultimately sentenced to two years in federal prison for what he did. His trial became quite an event in 2011, and really helped galvanize the climate movement, the climate justice movement, and helped make the climate movement more confrontational and more open to civil disobedience and direct action. He was released in April 2013, and he came to Harvard Divinity School. He's someone else, kind of like Thoreau who was a very spiritual person, but who has been led back to a radical political engagement. And we sat down, and we've had some very long, very honest conversations about all of this and that forms a big part of the book. The last chapter of my book is largely my profile of Tim.

CURWOOD: Bill McKibben and others were really highly effective at rallying people to oppose Keystone, and I'm wondering if the climate activism movement has turned its sights on public lands. Recently there was a demonstration at the White House demanding that Obama use his powers to stop leasing public lands and onshore and offshore for the extraction of fossil fuels. What you make of that development? How important do you think it might be?

STEPHENSON: Oh, I think it's hugely important. It may very well be the next front in the climate movement. Studies show that, you know, there's enough carbon in the ground in deposits on public lands in this country to more than cancel out the benefits of President Obama's climate policies. In fact, if we were to get it all out of the ground it would certainly wreck the climate. There would be no hope of ever getting climate change under control. So, yeah I think this fight is hugely significant, and I think it's where—certainly one of the directions—the climate movement is going right now is this focus on extraction on public lands, absolutely.

CURWOOD: You're very careful not to prescribe any actions in your book. You say the leadership is spread out over many groups worldwide. What's your view of what we should do next? You call this a long haul kind of calling. How so?

STEPHENSON: Hmm. I don't think that the climate movement needs to get deeply engaged in the nitty-gritty details of the current policies that are being proposed because most of them, really all of them, don't really address the situation at the scale and urgency that's required. And it's kind of pointless to get bogged down in a sort of gridlocked partisan debate over non-solutions. So, what we need to be doing is really forcing the issue and telling the truth, however extreme it may sound, which is that we're still along way from where we need to be on this.

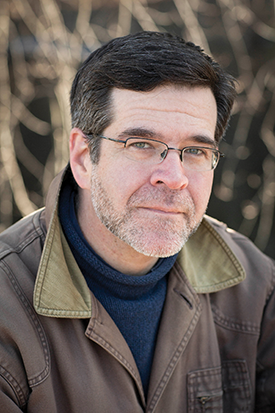

Wen Stephenson is an independent journalist and climate activist. (Photo: Gretjen Helene)

CURWOOD: So the negotiations around the UN Paris climate summit indicate that there will be some kind of the deal, although scientists who have reviewed the present commitments say that it would lead us to a more than six degrees Fahrenheit warming by the end of the century. How relevant do you think the UN climate process is?

STEPHENSON: So, think about what you just said: three and a half degrees Celsius. In 2012, the World Bank came out with a very influential report prepared by Germany's Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research—one of the foremost, if not the foremost climate science outfit in the world—saying that we're on track for four degrees, and that a warming of four degrees is most likely beyond our civilization's ability to adapt and so therefore quote "must be avoided", which were not doing. We're not avoiding it. I want an honest national conversation about what we're really facing: the science says we're really facing, what it would really take to address it, and what the consequences of our failure to address it are likely to be. When it comes to that conversation, when it comes to telling the truth or failing to tell the truth about climate change, there are, I like to think of it as sins of commission and sins of omission. Alright? Climate science deniers are guilty of sins of commission, right, they're telling outright lies. They're purposely misleading people ultimately for-profit, for political power. People like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, certainly not doing that, but they're guilty of sins of omission. They're not telling the whole truth, in fact they are leaving the most important parts out. So they talk about what a serious threat climate change is, but they don't bother to mention that we've all that run out of time to address it in a meaningful way, and they don't tell us what's really necessary to address it—the actual depth and speed of the emissions cuts required. But no one in American politics is really talking about how large the gap is, the so-called ambition gap, between we know what we say is politically possible and what scientists say is physically necessary, right? And we're certainly not spelling out for the American people what the likely consequences of our failures are likely to be. So I would love to hear Hillary Clinton, for example, or Bernie Sanders for that matter, really explain to American people, really spell it out for us, just how far we are from addressing this, and how they envision the United States leading the world in closing the gap. This is an emergency situation, and we need to start acting like it, so what do they propose that we do?

CURWOOD: Wen Stephenson's new book is called, What We’re Fighting for Now is Each Other: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Climate Justice. Wen, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

STEPHENSON: You’re very welcome, Steve. Thanks.

Related links:

- Wen’s book What We’re Fighting For Now Is Each Other

- More from Wen Stephenson in The Nation

- Stephenson regularly tweets on environment and climate-related issues

[MUSIC: Johnny Cunningham, et al., “Ding Dong Merrilly/St. Anne’s Reel”, The Spirit Of Christmas, North Star Records]

CURWOOD: And now a word about the next assignment for the crew at Living on Earth—COP 21 – the 21st Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change runs from November 30th to December 11th in Paris. This summit is being hailed as a critical chance for the nations of the world to work together to stave off catastrophic climate disruption. And we will be there to help keep you informed. Of course, this comes at a difficult time: the recent ISIS attacks have not only shaken the French capital but much of the Western world, and security concerns have led to cancellations of some major civil society demonstrations. But Paris has a long history full of dramatic events from the revolution and the reign of terror to its fall to the Nazis in 1940.

[MUSIC: Noel Coward, “The Last Time I Saw Paris,” music and lyrics by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II, Mad About the Boy (Castle Pulse 2005)]

CURWOOD: So please stay tuned as we work to bring coverage of what could become a turning point in world history. And if you hear of something we should report, please send us an email at comments@loe.org.

[SFX]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week, not in Paris, but in the southeast of France near Bresse.

[SFX]

It’s early morning, and the birds are starting to sing in the hedgerows and fields.

[SFX]

You can spot a blackbird singing loudly to wake up the world, and a church bell tolling.

[SFX]

The area round Bresse is famous for its chickens – they raise over one and a quarter million of them – and its blue cheese, Bleu de Bresse.

[SFX]

This soundscape comes from the CD "Dawns of the World” recorded by Jean Roche.

[MUSIC: 101 Strings Orchestra, “The Last Time I Saw Paris”, Music for a French Dinner Party, Countdown Media]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation and brought to you from the campus of the University of Massachusetts Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Emmett Fitzgerald, Lauren Hinkel, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, Jenni Doering, John Duff, Amber Rodriguez, and Jennifer Marquis. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jake Rego, Noel Flatt and Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living On Earth comes from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communication and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Kendeda Fund and Trinity University Press, publisher of Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril, 80 visionaries who agree with Pope Francis. Climate change is a moral issue for each of us. TU Press.org, and Gilman Ordway for coverage of conservation and environmental change.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth