February 3, 2017

Air Date: February 3, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

How Green is Judge Gorsuch?

View the page for this story

Appellate Judge Neil Gorsuch, President Trump's nominee for the US Supreme Court, has not presided over many environmental cases, but his well-written and very conservative court opinions provide insight into what his appointment could mean for law in this area. Vermont Law School Professor Patrick Parenteau tells host Steve Curwood how Gorsuch's narrow interpretations of agency powers, as well as his time spent in the outdoors, could inform his findings if he is confirmed. (11:00)

Standing Down at Standing Rock

/ Sandy TolanView the page for this story

Donald Trump's new executive order makes completing the Dakota Access Pipeline and building the Keystone XL pipeline more likely. Standing Rock Sioux leadership now wants DAPL protestors to go home. But many who opposed DAPL with the Native Americans in North Dakota for months are not ready to accept defeat. Reporter Sandy Tolan returned to the Standing Rock Camp to listen to the small band of “water protectors’ still braving the winter elements there and discusses the attitudes and developments with host Steve Curwood. (10:40)

Canada’s Choice: Tar Sands or the Climate

View the page for this story

On January 24, the White House called for the building of the Keystone XL pipeline to carry Canada’s tar sands to Gulf coast refineries, creating a dilemma for Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. And other pipelines he’s approved already may make it almost impossible to meet pledges under the Paris Climate Agreement, says a new report from advocacy and research group Oil Change International. Living on Earth host Steve Curwood spoke with the report’s co-author Adam Scott. (08:50)

Beyond The Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood dive into California waterways, where heavy rain and snow has ended severe drought in much of the region. They also examine the findings of a new report that paints a business-friendly picture of state environmental regulation, and consider a case of government overreach in climate research ten years ago. (04:25)

Golden Gobi Grizzlies

View the page for this story

Just a few dozen grizzly bears with bright yellow coats live in the forbidding Gobi Desert in Mongolia. Living On Earth Host Steve Curwood spoke with writer and wildlife biologist Douglas Chadwick -- who has returned to the Gobi desert season after season to track these astonishing bears -- about how they survive and what can be done to better protect them. (12:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Pat Parenteau, Adam Scott, Douglas Chadwick

REPORTERS: Sandy Tolan, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Some environmental advocates praise the character of US Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch, though they say his record suggests he would rule against Obama’s Clean Power Plan.

PARENTEAU: It's probably fair to say that Judge Gorsuch would be very skeptical of EPA's assertion of broad authority under a narrow provision of the Clean Air Act. But he's probably the best we could have hoped for in terms of a pick for the Supreme Court at this point.

CURWOOD: Also, the White House push for the Dakota Access Pipeline may mean the battle is over, but maybe not the war.

LOCKE: What I want people to know about Standing Rock is that we the people, we stood up against a multibillion dollar industry, and we took dog attacks. We took bullets. And we stood up for 10 million people’s drinking water.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

How Green is Judge Gorsuch?

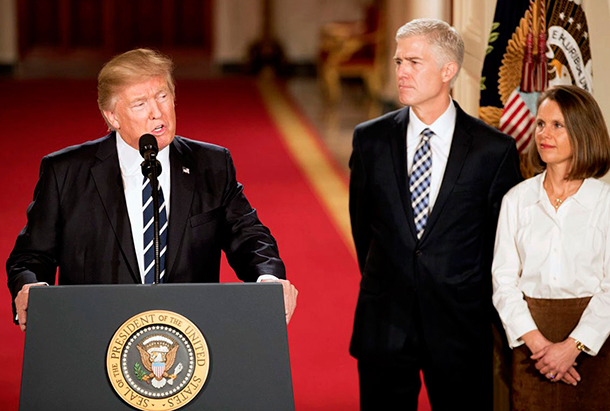

President Trump announces his nomination of Judge Neil Gorsuch to the US Supreme Court as the judge and his wife, Louise, look on. (Photo: Official White House photo, public domain)

CURWOOD: From the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston and PRI, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

In these first days of the Trump White House, there has been plenty of chaos and questionable decisions and appointments. But, thanks to the guidance of the conservative Federalist Society, whose board includes establishment legal lions, the Trump Administration has nominated a top-ranked appellate judge for the US Supreme Court. Judge Neil Gorsuch of the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals is seen as a strong legal scholar who shares many of the views, but not the temperament, of the irascible Justice Antonin Scalia, whose death last year created the vacancy.

Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau joins us to talk about how this conservative judge might approach environmental cases. Pat, great to talk with you again.

PARENTEAU: Nice to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, tell me first, who is Neil Gorsuch as a judge and lawyer? Talk to me about his corporate practice before he went on the bench. And it seems like a lot of Democrats as well as Republicans seem to like him. What do you make of all that?

PARENTEAU: Yes. Well, everybody agrees he's very smart, he's well-qualified to be a Supreme Court Justice. He did do a stint in private practice, but he was also actually with the environmental division of the Department of Justice where he did win praise and respect from his colleagues there. He is generally in the mold of the late Justice Scalia, but I wouldn't call him a Scalia clone. In fact, I think he’s probably a step to the left of Justice Scalia, but also probably more a step to the right of Merrick Garland who was, of course, Obama's nominee.

CURWOOD: So, what do you think about his nomination? Should he be confirmed, what do you think it would mean for environmental laws and regulations?

PARENTEAU: It's hard to read him because he has not written that many major environmental cases. He is most known for his opposition to what we call the Chevron doctrine, which, of course, is the doctrine that defers to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes. This is the issue that’s at the forefront in the Clean Power Plan litigation, and it's probably fair to say that Judge Gorsuch such would be very skeptical, like Justice Scalia was, of EPA's assertion of broad authority under a narrow provision of the Clean Air Act. So in cases where there's a major rule with major economic consequences, Judge Gorsuch is certainly going to lean towards the business side of the argument.

The US Supreme Court will likely make a ruling on the constitutionality of former President Obama’s Clean Power Plan in the next few years, assuming it is not withdrawn by the Trump Administration. Above, the Navajo Generating Station in Arizona is the largest single source of greenhouse gas emissions in the American West. (Photo: Alex Proimos, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The irony, of course, is that if anybody needs the Chevron doctrine to do what he wants to do, it’s Trump's choice to head the EPA, Scott Pruitt. If Mr. Pruitt wants to repeal Obama's environmental rules, he's going to need the Chevron doctrine to do that, and Judge Gorsuch sounds like he's not inclined to give a lot of weight to the agency's reinterpretation of statutory language. So, this doctrine cuts both ways; it may actually end up impeding the Trump administration's attempts to roll back environmental rules.

CURWOOD: What about that the Clean Power Plan? It's still, what, in front of the DC circuit court of appeals?

PARENTEAU: It is.

CURWOOD: Now, perhaps the Trump administration will it say doesn't want that to go forward. What do you think would happen?

PARENTEAU: Yes, they could move to voluntarily remand the rule, take it back, but my view is that the DC circuit, which heard arguments last year, by this point in time I think the court is probably fairly close to issuing a decision, and I doubt very much that they're going to appreciate having the Trump administration say, “Never mind, give us the rule back, we plan to repeal it”. I think the DC circuit is going to issue a decision, and there's a fair chance, not a certainty, that they may actually uphold the plan.

CURWOOD: So, what would happen in that case? I imagine that the incoming administration would appeal to the Supreme Court.

PARENTEAU: They would appeal to the Supreme Court. They might simultaneously seek to initiate a new rulemaking to repeal the rule. They can't just do it with the stroke of the pen. They've got to go through the full, what we call “notice and comment” rulemaking process, to repeal it. Or perhaps Congress will step in in the meantime and repeal the rule and maybe even amend the Clean Air Act to limit EPA's authority to promulgate rules like the Clean Power Plan, but there will definitely be a petition for review to the Supreme Court, regardless, frankly, of what the DC circuit does.

CURWOOD: So, let's go back to Judge Gorsuch. Some have called Neil Gorsuch a friend of fossil fuel companies and big business. How fair is that characterization of the judge, do you think?

PARENTEAU: You can discern a business friendly approach to questions, where environmental regulations impact industry. He is also known as quite an outdoorsman. He comes from Colorado. He's a fly fisherman. He's a skier and, in fact, he learned of Justice Scalia's death while he was skiing. So, he's a mixed bag, I think. He's definitely the kind of judge who looks to the text of the statute and doesn't try to read too much into it, but on the other hand, from the opinions I've seen he tends to follow precedent. He tends to think about the issues, and he writes very well. He tends to listen to opposing points of view. So, under the circumstances, given who's in the White House, he's probably the best we could've hoped for in terms of a pick for the Supreme Court at this point.

Judge Neil Gorsuch of the 10th Circuit Court. (Photo: United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit, public domain)

CURWOOD: And tell me about this renewable energy case that he ruled on that some environmental advocates say shows that this fellow has some plusses as well as minuses from their perspective.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, I think that he upheld Colorado's renewable portfolio standards from a challenge from an industry group that claimed that they were unconstitutional under what we call the Dormant Commerce clause, and the case involves some interesting facts. You can't extrapolate too much from his decision upholding the Colorado law, but the one thing that's clear from his description of this Dormant Commerce clause doctrine is that he thinks it can go too far in striking down state laws, regardless of whether they're for renewable energy or anything else. So, he tends to side with the states, which is consistent with his conservative sort of philosophy. Sometimes that will work to the benefit of the environment, as it does for renewable energy, and sometimes probably works the other way, but he does seem to, very much like Justice Kennedy, for example, look at the way law affects the rights of states and their sovereignty.

CURWOOD: Given that there's going to be a lot of conflict between the Democrats on the hill in the Senate and the Trump administration as well as the Republican majorities in both houses, from your perspective, how smart would it be for Democrats to fight the appointment of Gorsuch, given your view that is fairly moderate?

PARENTEAU: Well, they would certainly have to question him very closely on his views on a wide range of issues, of course, civil rights, social justice, and environment, and I think the Democrats have to show some backbone in this process. They're getting rolled pretty regularly with these nominations. Whether they want to invoke the filibuster and sort of go to the mat on this particular nomination, I'm not so sure. I would probably counsel against that. My biggest concern is that his appointment to the Supreme Court may well trigger Justice Kennedy's resignation. Kennedy is 80 years old. I think he would not resign if Trump got a really strongly right-wing judge, something like William Pryor who was being considered from the 11th circuit, who called Roe v. Wade “an abomination of constitutional law”. I don't think Kennedy would have resigned if some judge like that got appointed, but with his own clerk - Gorsuch was his clerk - he may well think the time has come for him to resign. That appointment will set the stage for a huge constitutional showdown over the Supreme Court.

Republicans in Congress have introduced bills to dismantle some of the regulations that the Obama administration issued in the last months of his term, including one that would cancel the “stream protection rule”, which sought to minimize coal mining pollution. Above, a stream downhill from a mountaintop removal mine runs orange with heavy metals even after attempted remediation. (Photo: iLoveMountains.org, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Pat, of course, children aren't responsible for their parents, but Judge Gorsuch had a very famous mother. Ann Gorsuch was the first woman to head the EPA. That was during the Regan administration. When she got in there, she moved to slash the budget by almost half, and then she was forced to resign in less than two years after conflict of interest questions were raised involving a toxic waste matter. How fair is it to assume that Judge Gorsuch's mother has no bearing on his judicial temperament?

PARENTEAU: Right. I was in Washington, D.C. during those early years of the Reagan administration with Gorsuch and with James Watt and fought them tooth and nail frankly. Of course, Neil Gorsuch doesn't get to pick his mother so we can't blame him for that. I suspect, though, in his upbringing he probably heard a lot of conservative rhetoric in the household around the dinner table, and he seems to reflect a lot of that. But I actually take some solace in the fact that he's an avid fly fisherman which means he spends a lot of time outdoors. He understands the habitats that’s necessary to produce high-quality trout habitat, so that's a good sign. That he's connected in some way with the natural world probably means he's more open to arguments when rules are designed to protect those kinds of resources that he himself loves. That should be a good thing.

CURWOOD: Pat, before you go, the House is some place, as we speak, in the process of canceling the Obama administration Stream Protection and Methane Waste rules using a congressional review act. Just take a moment to remind us what those rules attempt to accomplish and why Congress should be able to get rid of them.

PARENTEAU: Yes, the Stream rule under the surface mining protection act deals with coal mining in Appalachia, this process of blowing the tops off of mountains to get at the narrow coal seams and filling the valleys in the streams with the rubble and the waste. It is a very, very damaging process, of course, and this rule took eight years to be developed through two terms of the Obama administration, so, you know, it's a rule that has gone through an enormous amount of review and analysis with the states and with scientific bodies. So, for the Congress to simply come along and just wipe it off the books - which they can do, they have the authority to do that - probably means continuing damage to the mountains and the ecosystems of Appalachia. The one piece of good news there is that the coal market generally is down, way down, and many of the coal companies have already left Appalachia and gone to the west, to the Powder River basin.

Pat Parenteau is a professor at the Vermont Law School, where he teaches on environmental litigation. (Photo: Vermont Law School)

With the Methane rule, it's another rule that took a long time for the Bureau of Land Management to develop. It seems terribly wasteful, of course, to be just flaring off methane which is a valuable commodity. It’s 80 percent natural gas, but that's what has been happening and that's what the Congress appears poised to say can continue without regulation on public lands.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is an environmental law professor at Vermont Law School. Pat, that's for taking the time with us today.

PARENTEAU: Pleasure being with you, Steve.

Related links:

- LegalPlanet: “Predicting How Neil Gorsuch Would Rule on Environmental Issues”

- NYTimes: “In Judge Neil Gorsuch, an Echo of Scalia in Philosophy and Style”

- Heavy: “Neil Gorsuch & Environmentalism: What Are His Views on Clean Energy Laws?”

- Patrick Parenteau teaches environmental law at the Vermont Law School

[MUSIC: Carol Sloane (Don Abney, piano), “Angel Eyes” on As Time Goes By, Matt Dennis/Earl Brent, Four Star Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up...the challenge for Canada...tar sands versus the climate. Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Ensemble Anonymous, “Danse en rond” on Llibre Vemell, El Llibre Vermell, Analekta Fleur de Lys]

Standing Down at Standing Rock

Though many are making plans to leave, others have vowed to remain at the Standing Rock Sioux Campground even as President Trump’s Executive order makes halting the pipeline construction more difficult. (Photo: Joe Brusky CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Among the first actions of the Trump White House was an Executive Order to greenlight the building of the Keystone XL and Dakota Access oil pipelines. TransCanada has already filed a new application to get Keystone XL approved, but the final links of the Dakota Access pipeline, DAPL, are held up by an Environmental Impact Assessment required by the Army Corps of Engineers at the request of President Obama. For months, thousands of Native Americans and supporters stood shoulder to shoulder to protest plans to route this pipeline across lands held sacred and under a water source serving millions.

Now, reporter Sandy Tolan has returned to the Standing Rock camp to gauge reaction to the new developments with DAPL. Sandy, welcome. It can be rather cold on the northern plains. What’s the weather like at camp?

The flags lining Crazy Horse Avenue were still flying as of December when this photo was taken. (Photo: Jacqueline Keeler)

TOLAN: Yeah, it was very cold, although there was a thaw later in the week while I was there, but, Steve, pipeline supporters in Washington and in North Dakota are delighted that the Army Corps is about to give its approval to complete the pipeline by building the nearly last stretch under the Missouri River. As you remember it’s a nearly $4 billion project. It runs almost 1200 miles and would carry half a million barrels of crude oil a day from the Bakken oil patch in northwest North Dakota to a terminal in Illinois. After that it’ll go on toward the Gulf of Mexico. On Jan 31, North Dakota Rep. Kevin Cramer tweeted, “Start your engines. #DAPL #Approved,” and in a statement he said, “Got word from the White House today” that DAPL “has its final green light."

CURWOOD: So Sandy, how fair is it to say that the project, well is definitely going through?

TOLAN: It’s not necessarily the case, Steve. The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, which along with tens of thousands of so-called “water protectors” have been battling this pipeline for months, issued a statement disparaging supporters statements as “premature”. It said the Army Corps lacks statutory authority to stop the Environmental Impact Statement, and the Tribe believes abandoning EIS would amount to what it called an “arbitrary change based on the President’s personal views and, potentially, his personal investments.” Chairman David Archambault added, basically, “See you in court.”

CURWOOD: And what about the protestors, the so-called water protectors? How many are still there, and how to they feel about it?

TOLAN: Well, the numbers are down, Steve, partly because of the winter holidays but also because it’s been so darn cold. There was a high of 10,000 people last summer. By some estimates, it’s down to less than a thousand now. They are hunkered down in teepees, yurts, military tents. On some nights it’s gotten to 18 below without the wind chill.

But the people I’ve talked to recently remain determined to stand against the pipeline. In recent days with the lower numbers, with President Trump’s attempts to fast track the process, it’s all added up to a lot of uncertainty and disagreement about how to stop the pipeline or even whether it can still be done. There’s a lot of worry about that. But there does remain a strong conviction to continue the fight, including from Linda Black Elk, she’s an ethnobotanist and professor at Sitting Bull College, and a camp medic.

By some estimates, the numbers at camp are down from nearly 10,000 to less than 1,000 now. (Photo: Jacqueline Keeler)

BLACK ELK: I'm just a mom, you know, and I am a mom and a teacher. And I never thought that I would have to say I might have to put my freedom or my life on the line to protect my

children's legacy, right? What I leave them, whether that is the water, the land, treaty rights, sacred sites, but I'm willing to do it.

TOLAN: I should add, Steve, that many of the water protectors now see the fight moving beyond Standing Rock, as a part of the broader struggle against President Trump. And yet there remains tension between some of the protestors and the Standing Rock tribe.

CURWOOD: Sandy, why is there tension at the point? What’s going on?

TOLAN: Well, despite the recent executive memo from President Trump, the Standing Rock Sioux tribe has asked the water protectors, those who aren’t from Standing Rock, which is the strong majority of them, to go home. This has brought a lot of tension and hurt feelings too. A lot of people have sacrificed a lot to come here, given up work, family, at the request of the tribe, and now only to be asked to leave at this critical moment.

From the tribe’s perspective, they’re the people who know this land the best. The main camp is in a flood plain, and within weeks the Missouri River will inundate the land. They know this from, you know, really, thousands of years. Crews are on location now to start the massive job of breaking down and cleaning up the camp, even as other groups try to mobilize folks to come back and fight the pipeline. So it’s a very confusing time, and things are really breaking down in the camp physically. I mean structures are coming down, all the while that people are talking about bringing others back. Some in the meantime say they’re going to head home. Others say, “No,” they don’t care, they’ll just head to higher ground, including this fellow, Joseph Hock, who’s a military veteran and a native man from Michigan.

HOCK: I don't plan on leaving. When the grandmothers and the matriarchs of the Standing Rock Nation ask me to leave, then I’ll leave. I’m staying. I’m here indefinitely.

CURWOOD: Well, given that kind of reasoning, what are the other reasons, if any, the Standing Rock Tribal Council wants to shut the camp down?

TOLAN: Well, in addition to the cold and the coming floods, there are other physical dangers of staying. The aggressive militarized police response from North Dakota’s one of them, which, by the way, has led by the way to a visit from the United Nations at Standing Rock recently, hearing testimony on the police violence. And Morton County North Dakota is now facing a class action civil rights lawsuit. As part of that, in a sworn statement, the former police commissioner of Baltimore, Thomas Frazier, called the police tactics “contrary to modern law enforcement standards for use of force,” and he called the North Dakota police claims of “riotious behavior” to be “overstated and inaccurate.” The authorities, for their part, in court papers insist that is it protestors who have been the more violent ones.

But another reason, Steve, that the tribe wants the water protectors to leave is that the dynamics of the camp have changed. It’s close to majority white, and in recent weeks there has, in fact, been a much more verbally aggressive attitude toward the police among protestors on the front lines. And this is disturbing to a lot of the long-time water protectors. Yet when I spoke most recently with Linda Black Elk, Steve, she said that she believed that in their premature announcement about the easement, North Dakota authorities were trying to provoke activists into taking actions that would put their movement in a bad light. And she said, that’s not gonna happen.

CURWOOD: Well Sandy, the spirit of prayer and peace that the movement has become famous for, has that totally disappeared?

Activists who oppose the Dakota Access Pipeline call into question the City of Seattle’s banking relationship with Wells Fargo, one of the financers of DAPL.(Photo: Seattle City Council, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

TOLAN: No, no it definitely hasn't, Steve, but you have to remember, you know, some of these folks are really angry. They’re frustrated, they’re exhausted. They’ve been there for months, many of them politically uncompromising to the “Nth” degree. But it should also be pointed out that some of those more aggressive protestors are by all indications infiltrators, so called “agents provocateurs,” sent in by police and/or Energy Transfer Partners, the pipeline company, to stir up people. There’s strong photographic and video evidence, and along with the history of movement politics to back that conclusion. How many infiltrators, of course, it’s impossible to say.

CURWOOD: Meanwhile, as I understand it, many of the about 700 people arrested since August on charges such as engaging in a riot are due to come to court. What’s going on there?

TOLAN: Well, 76 people police called “rogue protestors” were arrested recently when they tried to establish a new camp on a hilltop above the old camp in the flood plain. Dozens of police and National Guard troops locked down the area, sealing roads during the police action. Some of the water protectors are worried that the police action was a distraction for a possible resumption of drilling at the river by the pipeline company. Most of those charged, meanwhile, face misdemeanor trials, but a couple face felony charges and could spend years in prison, and these cases could be winding through the courts for many months.

CURWOOD: Sandy what kind of confidence do the water protesters have that this fight still has a chance of succeeding, despite these recent developments? What do you think is likely to happen next?

TOLAN: It really depends on who you ask. One young man, a Native Hawaiian, told me, “Our original purpose in being here was taking part in those actions. It was a really cool thing to be part of. And now, with the Trump order, he said, “Nothing short of a miracle is going to stop that pipeline.”

I also spoke to a lot of people who remain convinced that the pipeline can be stopped in place, here. One young guy was telling me he believes 100,000 people will come out, but there’s little evidence for that, and anyway, where would they stay? Others say the pipeline can be stopped by actions in US cities, divestment in banks like Wells Fargo and Bank of America, and by pressure at other points along the pipeline. One activist vowed that the movement would block streets and highways, in addition to the pipeline route at various points, bringing economic ruin to North Dakota, he said. He told me, he sees this as part of a battle for the soul of America.

For some, though, I think there’s a slow realization that the forces of Trump, big oil and North Dakota authorities may end up prevailing. But they say this is a battle, this is one battle, not a war. That may sound optimistic until you listen to someone like Waniya Locke, one of the many extremely committed young people who have dedicated the last nine months to fighting the Dakota Access pipeline.

DAPL protestors who choose to stay through the winter risk seasonal flooding and sub-freezing conditions. (Photo: Jacqueline Keeler)

LOCKE: What I want people to know about Standing Rock is that we the people, including me, we stood up against a multibillion dollar industry and we took dog attacks, we took bullets, we took beanbags, we took water cannons. We withstood five blizzards, and we held on for nine months. This is the longest standing nonviolent occupation that has ever endured this long. And we stood up for 10 million people’s drinking water.

CURWOOD: Well, Sandy, sounds like she is suggesting the pipeline will, in fact, be completed, but surely, there are legal roadblocks to this project going forward, aren’t there?

TOLAN: That’s for sure, Steve. The coming days will determine whether the Army Corps follows the orders of the Trump administration or the prescribed, legal process determined by the EIS process. And given what’s happening across the new administration, and in the Congress, it’s anybody’s guess. But I sense a renewed battle coming on, in the courts and in the streets, and along the route of the pipeline.

CURWOOD: Thanks, Sandy. Sandy Tolan has just returned from the Standing Rock camp.

TOLAN: Good talking to you again, Steve.

Related links:

- Sandy Tolan’s latest story about Standing Rock for The LA Times

- Sandy Tolan’s website

- Presidential Order about the Dakota Access Pipeline -- Full Text

- The Standing Rock Tribe’s reaction to Trump’s order

[MUSIC: Ensemble Anonymous, “Cuncti simus concanentes” on Llibre Vemell, El Llibre Vermell, Analekta Fleur de Lys]

Canada’s Choice: Tar Sands or the Climate

An aerial view of an oil sands operation in Alberta, Canada. (Photo: Dru Oja Jay, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: With the Trump White House breathing new life into the Keystone XL pipeline, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau finds himself walking a tightrope. The Obama administration in November 2015 rejected Keystone XL, which would transport carbon-heavy tar sands oil from Alberta to refineries on the Gulf of Mexico. Prime Minister Trudeau recently approved the expansion of two other pipeline projects within Canada, saying the country could support jobs and still honor global warming cuts pledged for the Paris Climate Agreement. But a new report from Adam Scott of the research and advocacy organization Oil Change International claims any new pipeline blows through those climate targets. Adam Scott joins me now from Toronto. Welcome to Living on Earth.

SCOTT: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So, we learned that, perhaps about two months ago, Prime Minister Trudeau had approved the expansion of the pipeline to the west and the Enbridge line 3 pipeline to the east in Canada, and you recently published a report which looks into the effects of these pipelines on Canada's carbon emissions. What did you find?

SCOTT: Well, we really found that the combination of all these different pipeline projects would make it impossible for Canada to meet its obligations under the Paris Agreement, which went into force last year. But we also found that it would contribute so much carbon to the global pool of fossil fuels being produced that it would prevent global action on climate as well, so it would actually make it difficult for other countries outside of Canada to ultimately meet their goals. If you add Keystone to the other pipeline projects and assume that all of those pipelines get filled with new tar sands oil, it's a huge increase in greenhouse gas pollution.

It's important to understand why tar sands are such a huge target for people who really care about climate change. And it is because, unlike conventional oil wells where you drill a well and the oil well just produces for couple years and then declines, tar sands projects are designed to produce for 40 or 50 or 60 years, and so over the lifetime of these projects the total cumulative amount of emissions is gigantic, and that's what we really care about from a climate change perspective.

CURWOOD: So, tell me how economically feasible are these oil sands pipeline projects currently given that the oil is, what, around $50, $52 a barrel right now.

Public opposition to the two recently approved Canadian pipelines has been long-standing. Above, in 2014 women held a demonstration in Vancouver in solidarity with the People’s Climate March in New York City (Photo: Chris Yakimov, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

SCOTT: Yeah, at the moment there's not a lot of argument to build them. Conditions have really changed over the last two years. The price of oil, we used to see $110 a barrel, upwards of $150 a barrel over the last five or so years ago. But two years ago we saw a crash in the price, bringing it down are as low as $30 something dollars a barrel, and that's just not high enough to sustain tar sands projects which are amongst the most expensive types of oil projects on the planet. And so, you know, if oil prices stay very low, and many expect that they will in the near term at least, pipeline projects make no sense.

CURWOOD: So, Adam, what do you think the price of oil would have to get to for tar sands oil extraction to be economically feasible?

SCOTT: In order to move forward with new investments on tar sands projects, we need to see an oil price of between $75 and $100 a barrel, and that price has to be sustained over a long period of time, as well as having access to pipelines. So, that's what's required and there's not a lot of evidence at the moment that prices will stay that high.

CURWOOD: Now, let's talk about the Keystone XL pipeline that President Obama rejected, and Donald Trump is willing to give it a green light. How would the economics work right now for Keystone XL?

SCOTT: Well, right now the project would've been entirely dependent on companies looking to export their product down into the Gulf Coast of the US. And, you know, at the moment, there's already enough pipeline capacity to ship everything that Canada is producing. So, the pipeline project was largely about future projects. So a huge number of major tar sands projects were scheduled to come online in the future that would eventually fill the pipeline and make it profitable. When the oil price crashed, a number of tar sands producers, oil companies, decided to pull out their investments, and at the moment, we haven't seen any new investment in a tar sands project of any size over the last two years. So, if conditions continue, Keystone makes no economic sense.

CURWOOD: Answer me this. If oil is only at $50 or $55 a barrel, to what extent are the tar sands oil producers actually losing money?

SCOTT: Well, it's an interesting thing. The way a tar sands project works is you spend all your money upfront. So, it can cost billions of dollars to produce, say, a large tar sands mine, and it can take years to get into production. It takes 10 or 20 years to pay back one of these projects, and so the producers, even if they’re losing money on every barrel will have to keep producing. And that's what is so scary. Once the projects are built, it is very hard to turn them off, which causes huge problems as we try to transition the world off fossil fuels.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will need to balance his promises made at the Paris Climate Agreement with those he made to the oil sands industry in Alberta. (Photo: Laurel L. Russwurm, Flickr public domain)

CURWOOD: So, you're telling me that if there were to be a Keystone XL, the first 10 or 15 years would be just making the money back before it would even "make money"?

SCOTT: That's right. It could even be longer than that depending on how much the project costs, and so you can see that we’d be in a position where we can't turn these things off. If we're still in a position where we have large fossil fuel producers still operating and pipelines still running in 2040 or beyond, we're in deep trouble because by 2050 we really have to be looking at bringing our use of fossil fuels down to as close to zero as we can. That is what is required by the climate scientists to stay safe.

CURWOOD: How likely is it for TransCanada go forward with the Keystone at this point?

SCOTT: It's hard to say. We know that TransCanada actually, when they lost the approval, when Obama rejected Keystone about a year and a half ago, decided instead to pack up and take its cash and to spend it elsewhere. And they went out and purchased another pipeline company based out of Texas which has a whole pipeline system in the US and natural gas interest there. So, they spent, I believe, around $10 billion acquiring a different company. In addition, the project today would be far more expensive than originally proposed, billions of dollars more than the cost than it was originally proposed for, so it may not be profitable for them to go after the project.

CURWOOD: Tell me, why does Justin Trudeau in theory favor a Keystone XL when he also favors the Paris climate agreement?

SCOTT: Prime Minister Trudeau has put a lot of political capital and effort into saying he cares about climate change and that he understands what is required. And he's gone internationally to a number of different places and promised that Canada would be a leader globally on climate change. So, it really makes no sense that he's come out in support of pipelines.

Really, this has nothing to do with the pipelines themselves in Canada. This is about signaling to the oil industry that he's going to support them, and so it's largely about regional politics in Canada where politicians are keen to show, in particular voters in Alberta, where the tar sands are located, in the west, that they're going to do something to help them. His father was also the Prime Minister and PR Elliott Trudeau implemented a policy called the national energy program which was seen as taking money directly from the oil industry. And so, many folks out in Canada's western oil patch still hold a grudge about that. So, very early on in his administration, Trudeau went out and promised that he would not be like his father. And so he is very sensitive to try to at least appear like he's doing everything he can to support the oil industry. The crash in the oil industry over the last couple of years has laid off tens of thousands of workers operating in the tar sands, and it has had nothing to do these pipelines, but it is a way for politicians to show that they care and they’re trying to do something about it.

Adam Scott is a Senior Campaigner at Oil Change International and is based in Toronto, Canada. (Photo: Adam Scott)

CURWOOD: Well, so what are the options now, then, for the Canadian government in terms of saving face with environmental activists as well as industry?

SCOTT: Well, I think the big thing is that the Canadian government just rolled out its first ever serious climate policy, just a few months ago. And that climate policy has they have lots of great things in it: Reducing emissions from buildings and vehicles, and there's going to be a carbon tax in Canada. But the thing it didn't do was, address how are they’re going to address emissions from the oil industry. It's this huge blind spot. A credible climate policy would basically say, no new development of fossil fuel projects going forward.

CURWOOD: In the broader Canadian society, just how much do Canadians care about Mr. Trudeau's position on the climate and what he's doing to address it?

SCOTT: Climate change is an issue that rates very highly in Canada. A lot of Canadians care quite a bit, and there are very strong opinions across the country on both sides of this debate, but we've seen every year the concern sort of rising. And Canadians were very, very proud when Trudeau went to Paris and promised that we’d meet the goals of the Paris agreement, that we would do our fair share, and more than our fair share, on this issue. So it's a real problem that Canada's going to fail on this if it doesn't do something extra.

CURWOOD: Adam Scott is based in Toronto as a Senior Campaigner for Oil Change International. Adam, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

SCOTT: It's been great speaking with you.

Related links:

- NYTimes: “For Justin Trudeau, Canada’s Leader, Revival of Keystone XL Upsets a Balancing Act”

- Yale e360: “Canada’s Trudeau is Under Fire for his Record on Green Issues”

- Washington Post: “Canada accelerates plan to phase out coal power, targets 2030”

[MUSIC: Fleetwood Mac, “Say You Love Me” on The Dance, Christine McVie/Fleetwood Mac, Reprise Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, camels are common in deserts, but the Gobi Desert of Mongolia has camels and Grizzly bears. That’s ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward.

This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Mongo Santamaria (ensemble), “Summertime” on Brazilian Sunset, George and Ira Gershwin, Candid Productions Limited]

Beyond The Headlines

An unusually rainy winter has broken a years-long drought through much of California. Agriculture across the state, including this farm in Yolo County, is expecting a bump in production. (Photo: US Department of Agriculture, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Let’s join Peter Dykstra and the world beyond the headlines now. Peter’s with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org, and DailyClimate.org and is on the line. Hi, there, Peter. How’s the weather down there in Conyers, Georgia?

DKYSTRA: Hi, Steve, well, as we record, it’s 70 degrees here in Georgia, the daffodils have been out for a week and, yeah, it’s a little unusually early even for the south.

CURWOOD: Well I’ll trade with you. This morning in New Hampshire, it was 13 degrees. It’s supposed to snow, and actually we still have some drought.

DKYSTRA: Well speaking of drought, I’ve got some good news about California. A year ago, the experts told us it would take an outlandish amount of rain and snow to end California’s epic drought.

CURWOOD: I remember.

DKYSTRA: Well, it’s not “game over” for the drought just yet, but the state has bounced back from crisis. Just about half of the state is out of even mild drought conditions. A year ago, virtually the entire state was in drought, along with much of the Southwest, and two-thirds of California was in “extreme” drought. Today, only two percent of the state is in the extreme category, an area just north and east of Los Angeles.

CURWOOD: That is a big comeback. What kind of ideas do people have of whether or not it will stick?

DKYSTRA: Well, with a changing climate come more weather anomalies and more extreme swings, so all bets are off. But even after the rainy season ends in the spring, the Sierra Nevada snowpack is also above average for the first time in years, so the state’s enormous agriculture industry will at least get a break this year. And according to the US Drought Monitor, only a few other small patches of the country are still in extreme drought, in Oklahoma and Arkansas, Alabama and Georgia, and not too far from you in New England.

CURWOOD: OK, I like good news. You have any more for us?

DKYSTRA: You may have to settle for some mixed, counterintuitive news. The Trump Administration has made it crystal clear that it believes environmental regulation is bad for businesses, large and small, and they’ve grafted the words “job killing” onto just about every effort to protect the environment.

A new study from the University of Montana challenges that. Two Montana researchers surveyed 1,200 state-level environmental regulators. They generally had concerns about being overworked, and felt their departments were understaffed and underfunded. But only four percent of the respondents felt they had an adversarial relationship with the businesses they were in charge of regulating. 75 percent of the regulators thought their businesses were making an honest effort to comply with environmental rules.

A study conducted by the University of Montana has shed light on the relationship between state environmental regulators and businesses. Counter to complaints of “job-killing” regulations, the findings show that 84% of businesses reported a positive relationship with their state regulators. (Photo: Frank DiBona, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, those numbers do suggest that there’s not much in the way of conflicts between business and government at the state level.

DKYSTRA: Yeah, the researchers also did a smaller survey of the businesses to find out their feelings about environmental regulators. 84 percent said they had a positive relationship with their regulators. Two-thirds of the businesses said they strongly disagreed that their dealings with state regulators were “adversarial”.

CURWOOD: I think you hear more complaints about federal regulators, don’t you?

Hey, well, it’s time now to turn to our environmental history files. What do you have for us?

DKYSTRA: Ten years ago this past week, the House Government Oversight Committee held hearings on allegations of political interference in the work of government climate scientists. This, of course, was at a time when the Democrats controlled Congressional committees and a Republican, George W. Bush, sat in the White House.

Back then, a report by the Union of Concerned Scientists said that nearly half of all government climate scientists surveyed reported what they described as high-level meddling in their work.

CURWOOD: Give me an example of some high-level meddling.

DKYSTRA: Well, here’s one. In 2003, Phil Cooney, who was Chief of Staff for the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, ordered a re-write of a White House report on climate change to cast more doubt on human links to climate change.

CURWOOD: So what happened to Mr. Cooney when he got caught doing this?

Under George W. Bush, the President’s Council on Environmental Quality ordered a re-write of a White House report on climate change to cast more doubt on human activity as a cause. To the Union of Concerned Scientists, this represented high-level meddling in their work. (Photo: The U.S. Army, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DKYSTRA: Well, he left government, and he took a job with ExxonMobil.

CURWOOD: And of course Congress is still interested in interference with climate scientists, as I understand it.

DKYSTRA: Yeah, they’re so interested in fact that these days they’ve taken the lead in the interfering. For the past few years with a Democrat in the White House and Republicans in control of Congress, the House Science Committee has been a veritable inquisition chamber for government scientists and the agencies, like NOAA, who employ them. But now, there’s a chance that President Trump could fix this back-and-forth once and for all.

CURWOOD: Oh, really? How?

DKYSTRA: Well we might not have any government climate science at all. Good times!

CURWOOD: I wish you were joking, Peter. Peter Dykstra is with Environmental Health News, that’s EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Talk to you again soon, Peter.

DKYSTRA: Thank you, Steve. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: There’s more on these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- KQED Science: “About Half of California Now Out of Drought”

- U.S. Drought Monitor from the National Drought Mitigation Center

- The Conversation: “Research challenges the view that environmental regulators are anti-business”

- Climate Science Watch: “Investigation documents political interference with climate science communication”

- NYTimes: “Bush Aide Softened Greenhouse Gas Links to Global Warming”

Golden Gobi Grizzlies

A Gobi Grizzly negotiates a dry rocky slope (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: Grizzly bears can be huge and fearsome beasts, not to be messed with when you're out in wild country. Their range extends across western North America and through much of Asia. There’s even a tiny population of grizzly bears that roams the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, notable for their shocking coats of bright gold fur.

Wildlife biologist and writer Douglas Chadwick spent many seasons with a team traveling in the Gobi, to photograph and learn more about these creatures that seem to defy all odds. His new book is "Tracking Gobi Grizzlies", and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth.

CHADWICK: Thank you. Glad to be here.

CURWOOD: Hey, tell me about your fascination with grizzly bears. In your book you explain that your interest in Grizzlies began way before you arrived in the Gobi. What sparked that fascination?

CHADWICK: Well, I was like most people, Steve. I knew of the stories. I knew the “There I Was” movies, the little pioneer girl getting chased by the big bear. I carried a big .44 Magnum on my hip and worried a lot when I first started hiking in bear country. And one day I watched three bears. It was a mother sliding down a snow bank in the summer. It was a hot afternoon. I had been doing the same thing. And then she went back up to the top of the snowbank and put her two cubs on her lap and slid down on her back with them, and then they went up and did it again. And this went on for about 20 minutes and by the end of that I said, "I like these people. I want to know more about them. I don't think the stories and everything I've been told has given me any kind of reasonable picture of one of the master mammals out here with me.”

Douglas Chadwick chronicles his desert adventures in his new book, “Tracking Gobi Grizzlies: Surviving Beyond the Back of Beyond.” (Photo: Elena Meredith)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now, how did you learn that there was a population of grizzly bears living in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia? I mean, this is, you know, a lot of rocks and expansive deserts, not a place that I think of grizzlies.

CHADWICK: Not a place I would have thought of grizzlies. And I was thinking about bears while I was hiking in northwestern Mongolia in the mountains in a place that looked a lot like Montana with forests and glaciers up above on the border of Russia and Kazakhstan. And I was tracking Snow leopards on a story for National Geographic. And my translator, who’s a woman working for the Snow Leopard Trust, told me while we weren't seeing any brown bears, which are the same as grizzly bears, and I had expected we might because we were hot on the trail of snow leopards. There were ibex watching us from the cliffs as it was just that kind of place, but the bears had been pretty much shut out. And she happened to mention, "Well, we also got these other grizzly bears in Mongolia.” And I said, "Where?" And she said, "In the Gobi Desert." And I said, "We've got a communication problem. I thought you just told me there were grizzly bears living in the Gobi Desert." And she said, "My father happens to be the director of the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area, and he has studied them for 30 years.” And I said, "OK. Next question is, how many of these kinds of bears are there in Mongolia?" And she said, "About 30." I said, "Now that's in Mongolia. How many are there?" and she said "They're all in Mongolia and nowhere else. There are 30 Gobi grizzly bears left in the world."

CURWOOD: So, then you had to go. So, describe to me the first time you actually got to sight a Gobi grizzly in the wild, and how did you react?

The front claws of a Gobi bear that move across that same rock terrain month after month. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CHADWICK: Well, it's small and lean compared to our North American grizzly bears. It has wildly mussed up - I call it bed hair - sticking out all over the place and is very much a grizzly. We would catch them in a box trap in order to place satellite radio collars on them. And yet even a tranquilized Gobi grizzly, it was clear to me the power of the bear is the same as the ones we live with here, and certainly, as it came out of the drug, it started smashing up the trap and then proceeded to chase off a large van full of Mongolians and a couple of Americans that was five times its size. I said, "Yes, that's a grizzly."

But it smelled sweet. It smelled like dust. It smelled like plants that it had been digging. Its breath was warm. It had these stubby claws that said at a glance, “I have been walking on rocks all my life, and I have been digging through gravel to find roots, and I am a beat-up, thirsty, dusty bear on the outer edge of possibility, but I'm here”.

CURWOOD: So, why were you in the Gobi at that time, by the way?

CHADWICK: I had been invited to come down and join a research team of Americans and Mongolians, small group. I joined in 2011. I intended to just go over and learn about these bears and write about them based on one season. And the season is after they wake up in the spring and before June arrives because by then it's getting to be close to 100 [degrees] in the day, and any animal captured in a trap is the subject to heat stress. So we’d quit, and we’d go home. The project leader and others go back again to the Gobi in the fall and just simply track the animals. But I went over for five springs in a row and spent a month there camped out, not sure where I was half the time, but camped out somewhere, where we could access three or four oases, set up traps there and then spend the day tracking them through the countryside, observing other wildlife, finding out these little details, like Gobi bears often drink from pools that have been dug by the wild asses with their sharp hoofs. So if you're not saving wild asses you may not be able to save Gobi bears.

CURWOOD: You mentioned that they're small. Why are they so small?

CHADWICK: It's pretty hard to get big on a diet of wild rhubarb, wild onions, lizards, beetles, occasionally scavenging the carcass of a larger animal, but everything is few and far between, both plants and animals. And that number I gave you, 30, is probably an underestimate. It looks as though there are three to possibly four dozen, and it also looks as though they have been increasing very slightly since the study started in 2005.

Gobi Bear Project leader Harry Reynolds (left) and Michael Proctor check the mouth of a captured male. Tooth pattern and sharpness are good indicators of a grizzly’s age, but in the Gobi, estimates are adjusted to account for wear and tear from gravel and sand when foraging for roots, insects, and burrowing rodents. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the harsh environment, the outdoor environment there in the Gobi. It’s so dissimilar from the ones where nearly every other grizzly population is located. In the warm time of year, it could be, what, 120 degrees? And in the winter, it can be, what, minus 40, huh?

CHADWICK: It can be minus 40 with a heck of a wind coming off the Gobi Altai Mountains, and the bears do hibernate there, and their cycle is a lot like the one you’d find here with the bears in Montana in Glacier Park.

CURWOOD: So, Doug, there are just perhaps as many as three dozen, maybe four dozen of these bears. That's not many bears. Originally, how many would there have been there, and what happened?

CHADWICK: You know, it's a little like asking how many bison or how many grizzlies used to be in North America. Nobody knows because we blew through them so quickly. And there are estimates, and that's all you can have. And look, Gobi bears were not discovered or proven to exist until 1943, and that's simply a tribute to the size of the Gobi and the difficulty of living there and the fact that it was still just barely beginning to be explored around the early 1900s, and the Gobi bear was a myth. It was like Bigfoot or Sasquatch or something. There was something big and hairy roaming around out there that occasionally walked on two legs. And so I can't give you the number of how many would've been around. I doubt it was in the thousands, but it might have been.

Harry Reynolds sedates a captured bear. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: I understand that the pilot conservation project helps the bears by feeding. How exactly do you feed a grizzly?

CHADWICK: Well, first of all I spend a lot of time in Montana working with biologists and state and federal agency people going around telling people, “Please do not feed the bears.” And a fed bear is a dead bear because it learns to get food near humans and that's not a good strategy for staying alive. And suddenly I find myself not only in the back-of-beyond, riding around in a Russian-made van with a small herd of Mongols wondering what I'm doing, but we're going out to feed grizzly bears.

What you do is dump sacks of livestock chowder, or chow, into a big bin with a trough on the bottom and put it near the oasis. They don't depend on it, but there's a lot of drought years, and it's not getting any better in a warming, drying climate.

CURWOOD: Doug, how is the Mongolian government responding to these conservation efforts for the Gobi grizzlies?

CHADWICK: The Mongolian government...The best way to say this is, in 2013, the Mongolian declared that the year of the Gobi bear, which they call Mazaalai. And there were, there's even a Mazaalai vodka you can buy, and there's Mazaalai bread. And they know about the golden grizzlies of the Gobi Desert, and they want to preserve them. It's just that nobody had any... OK, we all want to save them. How? What do they need? What can be done? They've improved some of the water sources. They've got some solar-powered pumps that work. They've even tried cloud-seeding in the area. We work with University scientists from Mongolia. We've had the Minister of the Environment come down and join the team. They're more than willing to help.

Douglas Chadwick is a wildlife biologist and author with a love for grizzly bears. (Photo: Joe Riis)

CURWOOD: So, how well are these efforts going?

CHADWICK: Um, how it's going is the story I really wanted to tell, and that was the main incentive for the book. It’ss on the upswing, and some of the happiest moments of my life have been standing out even in a duststorm and bitter cold winds, but checking the images on the automatic camera set up near the feede. And as you scroll through them, all of a sudden there are two baby bears with their mom, so they are reproducing.

We're also finding more bears. The way you count them is...Obviously you're not going to cover an area five times the size of Yellowstone Park…but you can collect hair, and that count is going up by the year. So, it's very encouraging. And recently the Mongolian government just set aside a large reserve. It links this great Gobi Strictly Protected Area, where all the last bears are, through this new reserve to Gobi Gurvan Saikhan, which means Three Jewels National Park. And that is a bit wetter. It's got more vegetation, and it is a former range of the bears. And if they can connect through there, back into that former range, I think they'll do well.

Really, this story isn't just about, how do you save a Gobi bear? It's, how could you turn your back once you know they're there? You have to help somehow. That's how I felt. But more importantly, it's, like, if we can pull this off, it says something about all those big animals out there, so many of which are at risk around the world.

CURWOOD: Douglas Chadwick is a wildlife biologist and author of "Tracking Gobi Grizzlies". Doug, that's so much for taking the time with us today.

CHADWICK: Well, thank you so much for the time, and I don't know how else Gobi bears are ever going to be heard about or known by the rest of the world, and I'm glad for the opportunity. Thank you.

Related links:

- Tracking Gobi Grizzlies book website

- Douglas Chadwick for National Geographic: “Can World’s Rarest Bear Be Saved?”

- IUCN lists Grizzly bears as a whole as “Least Concern”, though some local populations are declining

- Douglas Chadwick’s National Geographic profile

[MUSIC: Childsplay, “Bob’s Child” on Twelve-Gated City, Matt Glaser, self-released by Childsplay]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Alex Metzger, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingOnEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Gilman Ordway, and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth