October 6, 2017

Air Date: October 6, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Power to Puerto Rico: Resilient, Renewable Microgrids

View the page for this story

Before Hurricane Maria devastated the island, Puerto Rico relied on an outdated, centralized power grid that burned imported fossil fuels. It will likely take be months or more to restore the system, but Robert Engelman of the environmental think tank Worldwatch Institute says this disaster offers the chance to rebuild Puerto Rico’s power system with more resilience and less carbon. Engelman and host Steve Curwood discuss how renewable energy and distributed microgrids can save costs and be a better solution to extreme weather. (10:16)

Climate Change Farming

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

Wild swings in the weather mean that some farm crops will flourish, while others will struggle. Allegheny Front reporter Julie Grant spoke with vegetable farmers in Pennsylvania about how the changing climate is changing our food and their future. (04:59)

Global Warming Threatens Nutrition

View the page for this story

Research is finding that increased atmospheric carbon is harming staple food crops by decreasing their nutritional value. Host Steve Curwood spoke with Harvard scientist Dr. Sam Myers about new research that suggests declining levels of iron, zinc and protein is putting human health at risk, especially in the developing world. (12:15)

BirdNote: Black-footed Albatrosses

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Seen from land, Black-footed Albatrosses look like tiny dark dots floating above the Pacific Ocean. But, as Birdnote’s Michael Stein explains, these large, graceful, ocean-faring birds are now headed to Hawaii to raise their one huge chick, that looks for all the world like a grey fluffy cousin of Sesame Street’s Big Bird. (01:57)

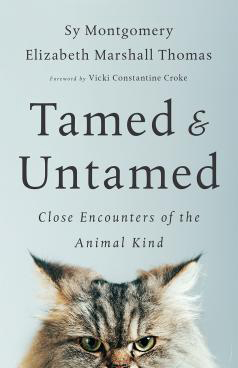

Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind

View the page for this story

The science of animal psychology is still developing and what exactly your family dogs, or wild rabbits are thinking is a fascinating topic for many, including committed animal observers, Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. These best-selling writers believe these and all creatures, wild or domesticated, deserve respect. Their new collaborative book of essays, Tamed and Untamed, dives into the curious mental and emotional space among creatures and humans, as they explained to host Steve Curwood, when he visited Sy Montgomery’s New Hampshire farmhouse. (16:41)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Robert Engelman, Sam Myers, Sy Montgomery, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

REPORTERS: Julie Grant, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Hurricane Maria, the devastating storm that raked the Caribbean, destroyed Puerto Rico’s aging power grid – with one notable exception.

ENGELMAN: Puerto Rico has the largest wind farm in the Caribbean, and we just got news that it survived the hurricane intact. Every one of its, I think, 44 turbines is operating, just as before the hurricane.

CURWOOD: How the island could reimagine its energy mix with micro grids, powered by renewables. Also, problems for farmers coping with global warming.

EGAN: The amount of extreme rainfall we’ve gotten has increased fully 71 percent. That means that Pennsylvania farmers are dealing with this paradox of way too much water at certain points of the year, punctuated by short but often fairly intense drought periods.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth. Stick around.

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Power to Puerto Rico: Resilient, Renewable Microgrids

The Universidad de Puerto Rico showcased its solar-powered house for the U.S. Department of Energy Solar Decathlon on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., October 2009. Puerto Rico’s renewable energy contributed a little over 2 percent of the overall energy mix prior to Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Stefano Paltera/US Dept. of Energy Solar Decathlon, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Puerto Rico was once covered by electric shades of green, lush tropical trees and plants that Hurricane Maria stripped to bare brown twigs. And people there are still stripped of the basic necessities - medical care, food and fresh water—and living mostly without lights in neighborhoods stinky with moldy garbage and broken sewers. The winds ripped Puerto Rico’s electric power grid apart, twisting it into a tangle of more than 30,000 miles of downed power and transmission lines that could take months if not years to restore. Since it all has to be rebuilt anyway, Robert Engelman, a Senior Fellow at Worldwatch Institute says, now is the time to boost renewables and convert the island’s power system to more local mini and micro-grids.

Bob Engelman joins me now. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

ENGELMAN: Thank you, Steve. Good to be back.

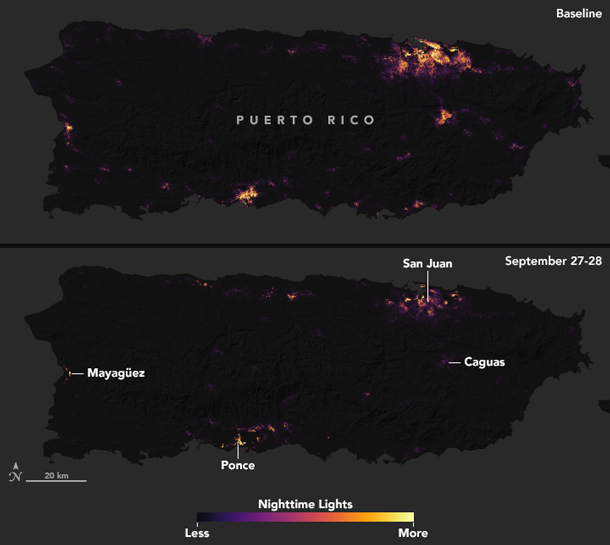

Puerto Rico has largely gone dark in the wake of the disruption to its centralized power grid brought by Hurricane Maria. (Photo: NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data courtesy of Miguel Román, NASA GSFC, and Andrew Molthan, NASA MSFC.)

CURWOOD: Bob, from what you know about energy and renewable energy, how do you think Puerto Rico ought to rebuild its system there?

ENGELMAN: Well, I think it's important to first state that the real priority in Puerto Rico is saving lives and restoring power as quickly as possible, obviously water and other basic services people need. That's the urgent need right now. Second thing is, it has a lot to do with what Puerto Ricans want. It's not something that you and I can decide from Boston or Washington DC, what exactly they should do. They've got to be involved in the process. But the third thing to say is they have an opportunity to start thinking things fresh, and Puerto Rico like the rest of the Caribbean has an enormous renewable energy resources right there on the island.

The sunshine is more than just a draw for tourists. It's actually quite strong. The power of solar irradiance to generate solar electricity is twice as strong as it is in Germany or Denmark which themselves have the bulk of solar power that's installed in the world as a whole, and it's similar for wind. The trade winds that blow across the Caribbean and that brought Christopher Columbus to the Caribbean in 1492, they blow between 10 and 30 miles per hour almost constantly, and these are very, very good wind speeds for wind turbines.

CURWOOD: Bob, you wrote a letter to The New York Times, and you asked why should these islands rely on brittle centralized electric grids and buy imported fossil fuels when electricity could flow through flexible community grids based on locally harvested wind and solar energy. What do you mean by “flexible community grids?”

ENGELMAN: Well, there is a lot more you can do with small grids than with large grids. It's easier to make them smart and responsive to their users. They frequently involve more public participation, community decisions about pricing, fuel mix. Communities might be more enthusiastic, for example, about using renewable energy than importing new fossil fuels, as is the case of almost all the energy production, or 98 percent anyway, of the energy production that's going on in Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico National Guard Soldiers supplied the HIMA San Pablo Hospital with 4,000 gallons of diesel on Sept. 29th to power their generator and keep health services working. (Photo: Sgt. Alexis Velez / The National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And of course, to what extent is it is zero sum game between renewable and fossil fuel? I would think that a distributed energy system could encompass both.

ENGELMAN: Absolutely, the way to think about is a little bit like, is whether meat is the center of your plate or meat is a side dish when people are starting to move toward vegetarianism. You don't have to choose one or the other but you can diminish the dominance of the one that's causing the most problems.

In the case of fossil fuel, it's important frequently in a transition period to use it as a backup, for example. The sun doesn't always shine. The wind doesn't always blow. So, absolutely they can work together, but the goal would be, especially for economic reasons but also for environmental reasons, to move as close to dominance and eventually complete reliance on the renewable energy as possible.

CURWOOD: And, Bob, you're not talking about people being completely off the grid, but being on whatever local or wide area grid there is. How could storage systems help Puerto Rico make the most of its renewable resources?

ENGELMAN: Well, batteries can be integrated with grids of any size. They make renewable energy much more feasible as a really important part of your base load in any size grid, whether it's a small community grid or a centralized grid like Puerto Rico had, and in fact, Tesla - which knows a lot about this and has probably been developing batteries more intensively and rapidly than probably any other company because they need them for their cars - has in fact donated a number of what are called “Powerwall battery packs.” These are home-based sort of small refrigerator size packs that can enable homes to save the power that they get from the sun during the day so they can use it in the night time and other times, cloudy weather, etcetera.

CURWOOD: Bob, how resilient can solar and wind energy infrastructure be in a disaster such as a major hurricane that well, as we know, completely trashed Puerto Rico?

Citizen soldiers of the Puerto Rico Army National Guard, alongside residents of the municipality of Cayey, clear downed power lines and other debris left by Hurricane Maria. (Photo: Staff Sgt. Wilma Orozco Fanfan, 113th MPAD / Puerto Rico Army National Guard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

ENGELMAN: Right, well, here’s the good news. Puerto Rico has the largest wind farm in the Caribbean, and we just got news that it survived the hurricane intact, every one of its, I think, 44 turbines is operating just as before the hurricane. That's amazing, so that's a part of its infrastructure that wasn't destroyed. That said, one of its other, much smaller wind farms did suffer some rotor damage because the rotors didn't close down the way they're supposed to in high winds. Wind turbines these days, the best of them are built to withstand about a Category three hurricane, but, as we know, Puerto Rico got hit by a Category four hurricane when Maria landed. So, there is an issue. It's not to say that it's perfectly resilient. Photovoltaic panels can blow off of roofs. So, this is not a binary situation where renewable is completely resilient and non-renewable is totally vulnerable.

But, I would say that renewable has an big advantages. You don't have to worry about having port facilities to import your fuels. It's going to be an issue for Puerto Rico whether it can import it fossil fuels it needs for a system given its port situations. There are a lot of reasons to think that, in general, renewable energy is likely to be more resilient, again, particularly if you're talking about distributed energy that’s small scale, that communities can control, ideally close to the ground, that doesn't require long distance transmission lines, etcetra. I think, on balance, resilience favors renewable energy well over fossil fuel energy.

CURWOOD: Let's talk about cost now. In some places wind and solar are cheaper than fossil fuel, certainly cheaper than coal. But one thing about renewable energy if you pretty much pay for all that energy up front. You buy the solar cells, buy the wind turbines and after that the costs are pretty cheap.

High-voltage transmission lines are a key part of a centralized grid, but they are susceptible to powerful hurricane winds. (Photo: Indigo Skies Photography, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

ENGELMAN: That's right.

CURWOOD: Puerto Rico has a lot of financial problems. Officially, it's what $75 billion dollars in debt, even before Maria. So, at the end of the day, how feasible do you think it's going to be for Puerto Rico to be investing in renewable energy?

ENGELMAN: I think it will be difficult for Puerto Rico itself to invest in renewable energy, which is a shame because over the long term it would be really helpful to its economy. But there is a federal act that was passed late in the Obama administration, with bipartisan support, I might add, called Promesa, which guarantees a bit of a break from creditors, the holders of Puerto Rico's bonds, and puts together an oversight board to make a plan for how Puerto Rico can handle its debt problems. And I would suggest that we gather this oversight board in San Juan and take a look at Puerto Rico's situation and see if some of its debt could be delayed, for example, and perhaps money could be diverted from what Puerto Rico has to repay, to at least assessing the potential to integrate as much sustainable and renewable energy as possible, as we repair the basic energy infrastructure of Puerto Rico.

I think it's really critical that we make a collective national effort to, I think, look at Puerto Rico as both for the benefits of its own citizens and the benefit of the country as a whole, a kind of a laboratory for how to make renewable energy work, and that's one reason I suggested, in a recent letter to The New York Times, that we consider federal/private partnerships that take on some of these upfront costs, not as a bail-out but as a way of learning from what we can do in one island with 3.4 million Americans, how it can become self-sufficient in energy and resilient in energy and resilient against the kind of super storms that are very likely to be hitting Puerto Rico in the coming decades.

Robert Engelman is a Senior Fellow at the Worldwatch Institute and its former President. (Photo: Worldwatch Institute)

CURWOOD: Some would say that Puerto Ricans have second-class citizenship when they're on the island. They can't vote for president of the United States or the Electoral College or get voting members of Congress, and that this is a considerable obstacle perhaps to this energy revolution that you're calling for for Puerto Rico. How might one deal with that fact? How might America be able to move forward on the status of Puerto Rico, at the same time that it responds to the devastating emergency there?

ENGELMAN: I think one important point is that as Puerto Rico develops, in terms of its energy system and in terms of developing economically and in terms of how they handle the incredible emergency disaster they've had to face, they're going to prove to the mainland American people who've been watching them that they're worthy of full citizenship, and they have a right to be a state. They're more populous than a number of states we have, and it may be that, I wouldn't necessarily call it a silver lining to this incredible disaster emergency they face, but it may be that in their own resilience, in the resilience of the Puerto Rican people in dealing with this emergency and working with the rest of America, the rest of the United States, there will be more opportunity, more chance people will be more sympathetic to the fact that they deserve full citizenship and full political and electoral participation in the United States’ representative democracy.

CURWOOD: So, it's not just electricity when you say "power to the people" of Puerto Rico.

ENGELMAN: [LAUGHS] I'll let you go with that, but that's a good one, power to the people of Puerto Rico. They're certainly connected. There's no question that having a resilient dependable power supply is critical to economic development, and economic development is critical to being fully integrated into the United States.

CURWOOD: Robert Engelman is a senior fellow and former president of the environmental think tank, Worldwatch Institute. Bob, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

ENGELMAN: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- Robert Engelman’s NYTimes Letter to the Editor, Sep. 28th 2017

- Bloomberg: “Puerto Rico to Get Power Relief From German Microgrid Supplier”

- Business Insider: “Tesla is sending hundreds of battery packs to Puerto Rico in the wake of major hurricanes”

- About Worldwatch’s Robert Engelman

[MUSIC: Nello Chiuminato, “Concierto para Charango,” not commercially available in the U.S. Information: http://nellochiuminatto.com/nello/musica.]

CURWOOD: Coming up, how too much CO2 can be bad for nutrition. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Nello Chiuminato, “Concierto para Charango,” not commercially available in the U.S. Information: http://nellochiuminatto.com/nello/musica.]

Climate Change Farming

On Matt Herbruck’s farm, they’ve shifted away from growing leafy greens because of changes in the weather. (Photo: Birdsong Farms)

Hurricane Maria wiped out 80 percent of Puerto Rico’s crops, shredding bananas and plantains and stripping coffee trees. In Florida, three quarters of this year’s orange crop was torn off by Hurricane Irma, and Texas farmers face huge losses from cotton and rice, submerged by Hurricane Harvey. Global warming increases the intensity and duration of these storms, and we can expect the trend to continue. But it’s not only violent storms that disrupt agriculture. Wide-spread droughts and heatwaves make farming increasingly unpredictable.

As Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front reports from Pennsylvania, there can be winners as well as losers.

GRANT: Farmer Matt Herbruck is glad he doesn’t have to focus his vegetable crop on peppers again this year. In 2016, the weather was so hot and dry.

HERBRUCK: Sometime in June, I could clearly see this was going to be one brutal summer.

GRANT: He says temperatures were five to 10 degrees above average, and instead of the usual 12 inches of rain from May through August, they only got two inches all summer.

It wasn’t enough water to grow lettuce and leafy greens.

HERBRUCK: So we went big into peppers and eggplants and things like that. Unfortunately peppers are really not the most lucrative crop, but we had a lot of them so that was nice.

GRANT: After 22 years of farming, Herbruck says it’s undeniable, the climate is changing, and it’s getting more extreme.

HERBRUCK: It’s not unusual at all in this area to go from in the 40s one night to 90, 36 hours later. It happens. And that’s not normal. I think the weather is crazy.

EGAN: I hear a lot about that from our farmers.

GRANT: That’s Franklin Egan, director of Education at PASA, the Pennsylvania Association for Sustainable Agriculture. And he says it’s more than just talk. He points to data from the USDA that show that while the amount annual rainfall in Pennsylvania and the Northeast U.S. has increased only slightly in the past 50 years, the way it’s coming down has changed.

EGAN: We’ve been getting a lot more extreme rainfall events.

GRANT: More than an inch of rain in a day is considered extreme.

EGAN: The amount of extreme rainfall we’ve gotten has increased fully 71 percent.

GRANT: It’s a startling number and a far bigger change than in any other part of the country.

EGAN: And so, if you put that together, you know, about the same annual rainfall, but more intense rainfall, that means that Pennsylvania farmers are dealing with this paradox of way too much water at certain points of the year, punctuated by short, but often fairly intense drought periods.

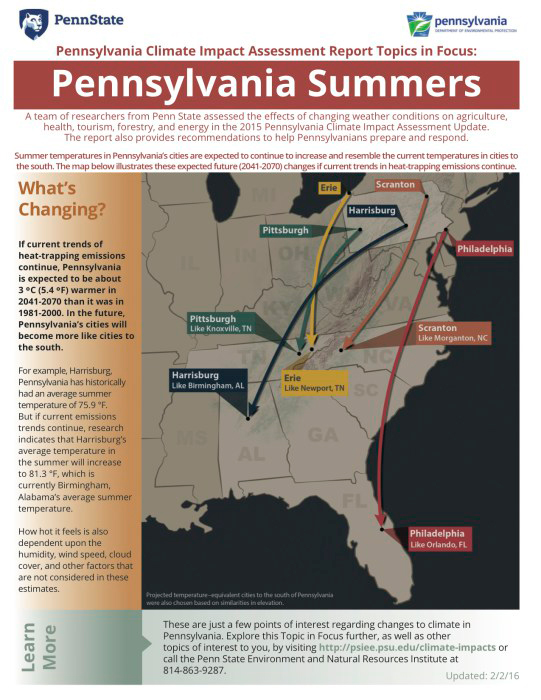

A fact pack from Pennsylvania’s Climate Assessment. (Photo: courtesy of Penn State)

GRANT: And both extreme wet and dry weather can make farming less reliable. And yet, Pennsylvania’s Agriculture Secretary Russell Redding says, climate change isn’t all bad for farms in the region.

REDDING: I would say at this point that it is a mixed bag.

GRANT: According to Pennsylvania’s Climate Assessment, last updated in 2015, those extreme rain events will get worse, and summer heat waves will get more frequent and intense. So places like Harrisburg would feel more like Birmingham, Alabama.

But whether that’s good or bad largely depends on what a farm produces. Dairy, poultry and eggs, corn, vegetables, nuts and fruits are all produced in Pennsylvania.

REDDING: There are going to be winners in this conversation, in terms of their ability to grow extended seasons and different crops, and there’ll be a downside because there’s a lot of production in agriculture that will not be able to tolerate the continued swings of rainfall and temperatures.

GRANT: One example of that mixed bag: fruit. On the upside, Redding says as the climate warms, new varieties of fruit are already being grown here.

REDDING: We have apple varieties that would have been in the Shenandoah Valley, in Virginia, that are now in Pennsylvania. So they’re real.

GRANT: Redding says improved farming practices could also be driving the success of these new varieties. On the downside, the warming conditions are implicated in new, unwanted pests. The Agriculture Department recently issued quarantine in six counties, to prevent the spread of the spotted lanternfly, a black, red and white insect that first appeared in Pennsylvania, and the US, just a few years ago. It could devastate the state’s tree fruit and grapevines.

REDDING: That becomes a major concern for us.

GRANT: For many farmers these unanticipated changes, and all the variability, mean they have to continually adjust their plans to suit the warming weather. Dairies are adding air conditioning to keep cows cool enough to produce milk. In fields, more are adding irrigation systems for dry periods. And more crops are being grown in hoop houses, for better protection from weather and pests.

Vegetable farmer Matt Herbruck says for years now he’s been shifting away from working the fields in July.

HERBRUCK: I just can’t. Stuff doesn’t grow that well, and also I’m not going out there when it’s 95 degrees. Who wants to do that?

GRANT: But he also sees some of the benefits of climate change. Nowadays, October is usually still warm enough for planting, so he’s still selling produce in November and December. I'm Julie Grant.

CURWOOD: Julie reports for the Pennsylvania public radio program, the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Learn more about this story on the Allegheny Front website

- Pennsylvania EPA Climate Assessment

Global Warming Threatens Nutrition

Rice and other staple food crops can lose nutritional value when exposed to elevated levels of carbon dioxide. (Photo: Sandeepa and Chetan Travel Blog (sandeepachetan.com), Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Climate disruption can be tough on agriculture, and now there appears to be another danger to staple crops as carbon dioxide levels rise. Nutrient loss. One expert in this field is physician Sam Myers, who recently published two papers looking at iron and protein levels in plants that get increased amounts of CO2 and how that may impact human health.

Dr. Myers is a Senior Research Scientist at Harvard and a Director at the Planetary Health Alliance. Welcome to Living on Earth.

MYERS: Thanks so much. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: Tell us how you believe this comes about, that increased carbon emissions, and thus more photosynthesis, actually can lead to a decline in nutrients.

MYERS: Well, for starters we're not absolutely sure what it is that's causing the decline in nutrients. So, whether or not it's related to increased photosynthesis, we actually don't know. It may be a direct effect of the carbon on the plants. But what we do know is that when we grow staple food crops at elevated concentrations of carbon dioxide, approximating where the world is going to be in the next 40 years or so, that those staple food crops lose a lot of their nutritional value, and particularly they lose iron, zinc, and protein.

CURWOOD: Give me a sense of just how much nutritional value they lose and why it's significant.

MYERS: So, what we see in a paper we published a couple of years ago in Nature, we showed that staple food crops were losing between five and 10 percent of iron, zinc and protein when grown at 550 parts per million. That sort of leaves a gigantic "So what?" question, which we've been working on for the last two or three years, in which we estimate the diets of the populations of 152 countries, and we model how if they continue to eat the same foods - these reductions of five or 10 percent in these nutrients - how many people would get pushed into risks of nutrient deficiencies which have significant health effects. And what we found were on the order of 150 to 200 hundred million people would be likely to be pushed into those deficiencies, and so that's why I said it’s a significant reduction.

CURWOOD: Yeah, talk to me about how many people around the world are at this point are undernourished or have inappropriate nutrition, in your view, and how your finding compares to that.

MYERS: Well, so there are lots of different kinds of what we call malnutrition. There's too much food, so we obviously have a crisis of obesity, really around the world now. There's too little food which is a caloric problem, and then there are micronutrient deficiencies. And so a lot of the work that we've been doing has been focusing in on those micronutrients, in particular, iron and zinc as well as protein deficiency, and so around the world today there are around two billion people - so, nearly a third of our population - who suffer from micronutrient deficiencies. And so in the studies that we've done we've looked at how many people would become newly deficient, but of course there also are hundreds of millions or billions of people who would have their deficiencies further exacerbated.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the health effects of these nutrient deficiencies - zinc, iron and so forth.

MYERS: So, for zinc, the burdens of disease from zinc deficiency are calculated for children under the age of five, and zinc is an important component of our immune systems, and so what we've found is that children that have adequate zinc levels will die in much lower numbers from common infections like malaria, pneumonia, diarrheal disease. And so when you look at what are called the relative risks, the risks of dying from those diseases, they're much higher in children who are zinc deficient.

For iron deficiency, there's a broader array of health effects. So, pregnant women die in higher numbers giving birth. There's higher neonatal mortality, meaning death of infants at birth or soon after. You get reductions in IQ and intelligence, reductions in work capacity, so there are a variety of effects from inadequate iron intake.

Researchers at the USDA found that Goldenrod, an important source of food for pollinators, has already shown a 30% decline in protein value since the middle of the 19th century, and it’s apparently linked to rising CO2 levels. (Photo: Karen Lewis, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Can you briefly explain for me, how you measure these nutrient levels in different parts of the world? The methodology you used, Sam.

MYERS: So, it's sort of been a two-step process. The first step is very direct, which is to grow staple food crops in open fields at elevated concentrations of carbon dioxide. And so, if you imagine an open field in the middle of the field is a ring of carbon dioxide emitting jets and you grow a specific cultivar of a specific crop, like wheat or rice, and outside the ring you grow the identical cultivar in the same soil, the same conditions, but at ambient, at regular, CO2 levels, and you compare the nutrient content of the crops inside the ring where the CO2 is high versus outside the ring, and that's sort of step one which allows you to estimate how much nutrient is changing as a result specifically of the CO2 effect.

The second step is to estimate how much of these different foods people are eating, and to do that we had to build something called the global expanded nutrient supply database, which is a database of the per capita consumption for 152 different countries of 225 different foods with their nutrient densities which we then use to model the total intake of things like iron and zinc for the populations of each of these 152 countries under today's CO2 conditions and under the CO2 conditions we anticipate by the middle of the century, and then you can look at the difference.

CURWOOD: Sam, where is this going to be the biggest problem? What parts of the world are going to be facing these kind of nutrient deficiencies?

MYERS: Well, so the deficiencies themselves are going to be most severe in South Asia and in Africa. In particular, India appears to be very vulnerable to these changes. We estimate about 50 million people in India alone would become protein deficient as well as the large numbers of people who are already protein deficient, and throughout Africa. And it's really a question of what their underlying diets are. So, people that have very little animal source food in their diet and are relying on crops like wheat and rice for large amounts of their iron, zinc, and protein intake, those are the most vulnerable populations.

CURWOOD: Sam, you're talking about parts of the planet are going to have a lot of trouble from climate disruption, especially with drought or crazy monsoon seasons. We're already seeing in Africa and India problems with growing crops now.

MYERS: There's no question that certain parts of the world are going to be particularly vulnerable, and one of the issues that this kind of work, I think, brings into very sharp contrast is an issue of equity and social justice. Because if you think about where the carbon emissions are going to come from between now and 2050 or so, to get us to 550 parts per million, and then you think about who is going to be vulnerable to those rising CO2 levels and experience nutritional deficiencies as a result, they're almost mirror images of each other. And so it's really the wealthy people in the wealthier parts of the world that are emitting much higher levels of carbon dioxide, and it's the poorer people in the poorer parts of the world that are suffering the consequences. And so, it really does become an issue of social justice, to think about how we take better care of those vulnerable populations.

CURWOOD: Dr. Myers, as you know, we began the present era around 275 parts per million of CO2. We're up to 400 now. Your research looks at 550, but to what extent might we be experiencing this loss in nutrient density even now with an increase in CO2?

MYERS: So, it's a wonderful question. Essentially, if you think about how we would answer that question retrospectively, the easiest thing we could do would be to look for archived samples of grain, for example, that had been grown at an earlier time when carbon dioxide levels were lower. And the problem with that methodologically is that the cultivars that we grow, things like wheat and rice and soybeans, are changing on average every three or four years, and so there isn't a longitudinal series, there isn't a single cultivar that we can track over time that way. And so what we do know is that nutrient contents have been falling in crops for decades, and you know, some of that is probably just that we've been breeding crops to be very high yielding without a lot of concern about their nutrient content. So some of that may just be a result of our breeding program, and some of it may be a result of CO2.

Sam Myers MD is a Senior Research Scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Director of Planetary Health at the Planetary Health Alliance. (Photo: courtesy of Sam Myers)

But there was a wonderful piece of research that was done I think a year or two ago by my colleague Lou Ziske at the U.S. Department of Agriculture in which he did that analysis but not for food crops. Instead he looked at goldenrod, and it turns out that there are herbaria around the country that have been archiving specimens of goldenrod going back to the 1850s. And goldenrod is actually a very important plant for pollinators, particularly bees, because it's late flowering plant flowers in the autumn and gives bees a lot of the pollen that they need over winter. It feeds them before they become dormant. And so he looked at the pollen itself from goldenrod flowers going back to, I think it was 1851 or so, and what he found was that there's been a 30 percent reduction in the protein content of the goldenrod pollen between then and now. He then set about to actually reproduce that data in the laboratory by growing goldenrod at different carbon dioxide levels, and he showed that reproduce it perfectly and it was essentially a linear relationship, that, as CO2 was rising, the protein content in the goldenrod pollen was falling. And so we do have that sort of anecdotal evidence to suggest that there may well be a linear effect and that we may well already be suffering the effects of rising carbon dioxide on the nutrient content of plants.

CURWOOD: What are some of the possible solutions to this crunch that's coming, declining nutrient value with increased CO2 and other effects from climate disruption?

MYERS: Well, I mean, on the first solution is to stop emitting so much carbon dioxide. So, in public health we talk about primary prevention. That would be primary prevention. So, we need to think hard about ways that we can decarbonize our energy economy as quickly as possible.

Secondary prevention would be things like bio-fortification of crops. So, developing crop types that are enriched with respect to these nutrients, like iron and zinc and protein, or breeding crops that are less sensitive to the CO2 effect and there's some reason to believe that might be possible over time.

Many of these vulnerable nations would do well to think about ways that they can increase dietary diversity, so that their populations are consuming a wider variety of foods that give them a stronger nutritional base. So, the first thing is to get countries recognizing that this is a threat developing as we speak and that they need to think about what's most appropriate for their particular populations.

CURWOOD: Physician Sam Myers is a senior research scientist at the Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health and Director of Planetary Health at the Planetary Health Alliance. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Sam.

MYERS: It's a great pleasure to speak with you. Thank you.

Related links:

- Protein deficiency study from Environmental Health Perspectives

- Iron deficiency study from GeoHealth

- Listen to our previous interview with Dr. Sam Myers, “CO2 can reduce food value”

[MUSIC: BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote: Black-footed Albatrosses

The Black-footed Albatross uses wind currents and shifts in air pressure to fly for hours over the Pacific Ocean while barely needing to flap its wings. (Photo: Tom Grey)

CURWOOD: We head out to sea for today’s BirdNote, to catch up with some of the most magnificent of the pelagic creatures off our shores. But as Michael Stein points out, though the adults may be glorious and graceful birds, the infants are, well, downright dumpy.

BirdNote®

Black-footed Albatross, Graceful Giant

[SOUND OF WAVES AND SEA BREEZE AND CALL OF THE BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS]

Just a couple of dozen miles off the Pacific Coast, immense, dark birds with long, saber-shaped wings glide without effort above the wave-tops. These graceful giants are Black-footed Albatrosses, flying by the thousands near the edge of the continental shelf.

[SOUND OF WAVES AND SEA BREEZE AND CALL OF THE BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS]

Albatrosses arc and coast over the ocean for hours with hardly a flap of their wings. Making the most of wind currents and shifts in air pressure, these wondrous seabirds seem to levitate over the water.

[SOUND OF WAVES AND SEA BREEZE AND CALL OF THE BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS]

Black-footed Albatross numbers peak off the coast in summer. Many adults return to the Hawaiian Islands during our winter and spring, to court and nest on sandy islands.

Albatross parents travel hundreds of miles to collect food for their nestlings, which are raised one at a time and grow to be massive. (Photo: Eric VanderWerf, US Fish and Wildlife Service, CC)

In Hawaiian waters, the Black-footed Albatross collects squid and masses of flying-fish eggs with its long, hook-tipped bill. Adult birds may fly hundreds of miles at sea to provide food for the single, goliath nestling, which looks more than a little like a portly, gray, recumbent version of Big Bird.

[BLACK-FOOTED ALBATROSS ADULT WITH BEGGING NESTLING]

I’m Michael Stein.

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Sounds of the Black-footed Albatross provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. Call of the adult and begging call of the young recorded by W.V. Ward.

Ambient track provided by Kessler Productions

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Chris Peterson

© 2005-2017 Tune In to Nature.org October 2017

Narrator: Michael Stein

http://birdnote.org/show/black-footed-albatross-graceful-giant

CURWOOD: Glide on over to our website, loe dot org for some pictures.

Related links:

- The “Black-footed Albatross, Graceful Giant” story on the BirdNote® website

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology: About the Black-footed Albatross

[MUSIC: Jean “Toots” Thielemans, “Theme From Sesame Street,” composed by Joe Raposo, Sesame Workshop]

CURWOOD: Coming up -- talking – and listening – to the animals….That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in the aerospace, food refrigeration and building industries. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Leigh Howard Stevens, “Sonata in b-minor, S.1003” on Leigh Howard Stevens Plays Bach On Marimba, composed by Johann Sebastian Bach, Resonator Records]

Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind

The octopus is sometimes depicted as a monster -- Victor Hugo described these deep-sea creatures as horrifying – but writers Sy Montgomery and Liz Thomas say octopuses are far more personable than we realize. (Photo: Scott Ableman, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[DOOR CREAKS OPEN, DOG BARKS]

On a warm afternoon in late summer Thurber, the Border Collie, welcomes me into his home. He shares an old New Hampshire farmhouse with writer Sy Montgomery, and today they are joined by author Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

Sy is an old friend of Living on Earth who over the years has celebrated pigs, octopuses, sharks, pink dolphins, moon bears, and more with stories from around the globe. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas is noted for writing The Hidden Life of Dogs, a groundbreaking book probing dog psychology.

Sy heads outside into her garden.

MONTGOMERY: I will lead the way...

[SOUNDS OF WIND, BIRDS, OUTSIDE THE HOUSE]

CURWOOD: These best-selling authors have teamed up on Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind, a book of essays that explores how wild and domesticated creatures and people relate. The essays are adapted from a Boston Globe column they co-wrote that sometimes offered advice that, as Sy admits, raised some eyebrows.

MONTGOMERY: We kind of got in trouble for our first Q and A.

CURWOOD: Uh-oh.

MONTGOMERY: Someone wrote in and they said you know I've got this dog who barks, and I love him so much, and now I have this new boyfriend, and he doesn't want me to keep the dog, which I do. And we said, you know, we normally don't recommend euthanasia, but your boyfriend has got to go.

CURWOOD: So, you wrote this book with, with Sy Montgomery, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas but both my producer, Noble, and I, when we were reading the book had a lot of trouble figuring out whose voice was whose. For each story in it, you had the same voice. How did that come about?

THOMAS: Maybe we just had the same voice before we ever met. I bet that's it.

The Stunt Dog Experience is a travelling circus show that takes in abandoned dogs and trains them to perform for a crowd. According to Sy Montgomery, dogs want tasks to occupy their time and enthusiastically take on jobs. (Photo: Branson Convention and Visitors’ Bureau, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

MONTGOMERY: We did think about that, and that's why with each chapter at the top we reveal which one of us is speaking, but I think Liz has been a very big influence on my writing. I think we come from the same heart. I mean, what we're saying in this book and every single essay, whether it's about hyraxes - these little groundhog-sized relatives of elephants who live in Africa - or an octopus at the New England Aquarium or the dog at your feet, these lives are so fascinating, so intricate, so mysterious, so thrilling, and so worthy of our respect and affection and awe. That's what we're saying in every single essay, and that may be why that kind of heart comes through.

CURWOOD: There's a theme throughout your book. It's a finger-wagging theme about people who abandon their animals, who abandon their pets.

THOMAS: Yeah, I have two cats who my neighbor found as kittens by the side of a long empty road. Somebody just tossed them out of a car. And she couldn't take them, but I could. She called me and I, of course, came and got them. [LAUGHS] And they're with me now. They're wonderful cats. They were Russian Blues, and if you buy one it's expensive so the person didn't even know that she could have sold them for hundreds of dollars. I mean, but that's not the point. The point is that, how can you do that? How can you do a thing like that?

Another woman released a rabbit in my field, and the rabbit had never been alone before, and he'd never been out in the wild before, so to speak. He had no idea what to do. And also it was in the middle of the field so he could be seen from every direction. He wasn't happy about that, and he saw our house in the distance, and he came to it and he went into the garage.

The woman, I'm sure she was letting him free. She thought that animals are on automatic pilot. When they get in the woods, they’ll know exactly what to do, and he'd be happy, and so it wasn't an evil thing on her part. But it didn't work. The dogs found him before I did, and they killed him. And I think people don't think along those lines.

Rats get a bad rap, says Sy Montgomery, but they’re much more like humans than we think. One of our shared characteristics is laughter. (Photo: zemasterdod, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

We're alike in every other way with every other mammal. OK? We have hearts, we have livers, we have kidneys. But the brains aren't the same? Of course they're the same. Why wouldn't an animal feel the same way we do? Of course, they do.

MONTGOMERY: And the idea that animals don't think is insane. I mean they don't think about their shopping lists. They don't think about what they're going to wear tomorrow, but they think. And anthropomorphism is one of those bugabears that we take on also in the book and in our columns and in our other work. The idea that, when you talk about an animal having thoughts and feelings, that this is anthropomorphic, well, that's ridiculous. Of course they have thoughts and feelings. A much worse mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

It's easy to make a mistake and even with a human being attribute your own thoughts and feelings to them. All of us have bought a birthday present for someone that didn't go over. All of us have asked someone out on a date that didn't want to go. And that happens with animals too. One of the essays is about this, in fact, that people can make mistakes like the veterinarian who thought that the Tasmanian Devil was so calm, it was yawning. Well, then it bit her. It was a gape threat, it wasn't a yawn. But you know you can make that mistake, but a much bigger mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

THOMAS: There's a new word in the English language, and it was invented by...He's a famous scientist. He's a biologist and primatologist, Frans de Waal. He invented the word “anthropodenial” which is the opposite of anthropomorphism, and it means presenting an animal as if it did not have human characteristics.

CURWOOD: Now, I think Sy wrote this essay, about going to see a sort of a dog circus.

MONTGOMERY: Oh, yes, we went together. Liz wrote that, but I took her.

THOMAS: Oh, yeah.

MONTGOMERY: That was...what was it? It was some kind of celebration. It was so much fun.

THOMAS: It was fabulous, and what we saw! All the dogs in the show, they did things you've never seen a dog or a person or anything do before.

CURWOOD: Like?

THOMAS: Well, one dog jumped up, a little dog, jumped up on his owner/trainer's hand and stood on her front legs on his hand with her hind legs in the air, and he lifted it up like that, and she - I reached my arm way up in the sky -- He lifted his arm way up and she retained the pose and came down. I mean a person couldn't do that. I mean a person can't do a lot of things. That's no comparison. But they would be trembling with excitement, and then they'd be called to do something, and they would rush off and do it, and they loved it.

Like this chicken, Sy Montgomery’s flock of hens roams freely during the day. Though these clucking birds are often considered unintelligent, the writer argues that they are quite smart, and can even develop distinct names for the people and animals around them. (Photo: Grey World, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

All of these dogs were strays or abandoned or from shelters or they found on the street wandering homeless, dogs that somebody else thought was worthless and tossed them, and these dogs were phenomenal what they were able to do. So, this is what people toss when they get rid of their pets.

MONTGOMERY: Some people think like, “Oh, you know, training a dog is just forcing it to do some horrible thing that…” No, they love having something to do, as do a lot of animals. They'd rather have something to do than nothing to do.

THOMAS: And people are the same, so there we are.

MONTGOMERY: And they love our company, and in fact, Thurber, our dog, is taking - I kind of hate to admit this because I purposely did not have children - but he's taking dance lessons right now.

THOMAS: [LAUGHS] My dogs are learning not to pee in the house.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now, so you're teaching your dog to dance. Sy, in this book there's another dance scene with...

MONTGOMERY: Snowball, the Dancing Cockatoo!

CURWOOD: So, describe this for me.

MONTGOMERY: Well, I actually found out about Snowball the Dancing Cockatoo on YouTube. He was an unwanted bird. He was dropped off at this parrot rescue facility in Indiana, and he came with a CD. And when he was dropped off, the fellow told Irena Schulz, you should play that and see what happens. Well, she had a lot of birds to take care of, so she didn't get a chance to do it right away, but when she did, she put it on. It was by the Backstreet Boys, it was one of their really great rockin’ songs.

[BACK STREET BOYS MUSIC. SOUNDS OF COCKATOO CALLING. Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

MONTGOMERY: Well, the Cockatoo starts rockin’ out. His crest is rising. His wings are spreading. His tail feathers spreading. His feet are going up and down, and he's doing it to the beat of the music. He's also calling out.

[MUSIC: Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

MONTGOMERY: She makes a video of this, puts it on YouTube. It went viral. Well, turns out, this was the beginning of an important discovery about abilities that parrots have.

[MUSIC STOPS]

MONTGOMERY: They have an ability that was previously thought to belong only to so-called higher minds like ours, and that is called “beat perception and synchronization.” They can anticipate the next beat, even though, for you and me, we unconsciously tap our feet to the beat, but other animals apparently can't do this, but parrots can, and it's probably associated with vocal learning.

So, I, of course, had to see this. I had to write about it, and I spent one of my birthdays with Snowball rocking out to the tunes of my choice.

[MUSIC: Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas co-wrote Tamed and Untamed, a collection of essays adapted from their Boston Globe column by the same name. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

MONTGOMERY: A researcher named Ani Patel did a project on this. He had written a wonderful book on music and the brain, and he also saw this YouTube video and worked with Irena Schulz to produce, actually several papers now. He found that lots of parrots can do this, and some other birds can do it, and it only works with certain tempi.

CURWOOD: You know, correct me if I'm wrong, but I think at some point in your book you say that rats like music.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, rats do like music.

CURWOOD: What kind of music?

MONTGOMERY: Well, you know I don't think this has been as systematically tested, but rats are very like us in many ways. Rats laugh. If you record it and then speed it up or slow it down, you can hear them laughing, and they laugh when they're tickled, just like we do. And these are animals that everybody thinks of as vermin, and yet they are so like us. They enjoy the same kind of stuff that we do.

THOMAS: Well, we use rats, we use mice for experiments that we think will help our bodies, so we may think we're nothing like them, but of course we really are, biologically speaking, just physically speaking.

MONTGOMERY: And we can sometimes get to animals’ thoughts, and rats are one of the species that we can sometimes almost literally see their thoughts. When they run a maze, you can see what their brainwaves are doing as they come to different parts of the maze. And recently there was an experiment looking at what their brainwaves looked like when rats were dreaming. And they could see the brainwaves were exactly the same as when the rats were running the maze. The rats were dreaming about their work, just like we dream about our days and our work.

CURWOOD: In the book, there was, well, kind of this theme of animals with bad reputations among certain humans. How conscious was that decision, do you think?

MONTGOMERY: I think we, we really did want to rehabilitate some of these reputations for animals because, if you remove a bad reputation, you can begin to appreciate the creature for what it is. Rats are one example. Great white sharks. Octopuses even. Octopuses were thought of as these horrible monsters that Victor Hugo certainly didn't do them any good in the PR department, but they're not at all. It's just preconceived notions, and it's fun to knock those down and instead welcome people into the company of these great animals and appreciate them for what they really are.

THOMAS: Yeah, and there are ways of looking at it. I was thinking of, I think, it's in one of the essays. If you see a fly or something like that, you swat it.

CURWOOD: Even as Elizabeth Marshall Thomas makes her point, it’s clear that any stray insect or tick in Sy Montgomery’s expansive yard is likely to be gobbled up by an ever-present flock.

THOMAS: If an eagle, a magnificent eagle, was the size of a fly, you would swat it.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

CURWOOD: Now, these ladies they’re are two-legged, and they have these red combs. They're chickens. They're coming towards us. Someplace in this book you say that chickens actually name people, or they seem to.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, this was not my discovery. This was my friend and colleague Melissa Cowie’s discovery. She's the author of a kid's guide to keeping chickens, which is how I met her.

Sy Montgomery (left) and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas (right) pose with Montgomery’s beloved border collie, Thurber. They spoke with Steve Curwood at Montgomery’s New Hampshire farmhouse. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Well, she was out with her hens one morning, just throwing scratch, and noticed that one of her chickens, a six-year-old named Oyster was using a different voice than usual, and she knows what her chickens are saying. She's decoded quite a number of different vocalizations, like, “Oh I've just laid an egg”, or “Hi, how are you?”, or “Oh my God, there's a hawk over there!” They have lots of different things that we know what they say. But there was this one vocalization that she'd never heard before, and soon everyone in the coop was using it, and they just used it when Melissa walked into the coop. Well, we figured out that that was the name the chickens had devised for her.

And this happens with a lot of animals. They have specific names for specific events, specific predators, or maybe even specific people, and the fact that a regular person, just paying attention to the chickens in her backyard, made this huge discovery about the intelligence of an animal that so many of us think of as ordinary, just shows us how splendid and exciting this world is, no matter what animal or plant or landscape you set your eyes on. There's just so much out there to be revealed.

In a book like this what you're trying to get across is, “Isn't this Earth splendid? Aren't these animals wonderful? And don't we owe them our affection and respect?”

And, even though this is just a book of essays that we loved writing, it's part of a growing assemblage of writing from people who are really, I think, believing that we can build a more compassionate world. You alter your behavior, once you realize that this chicken loves her life. She doesn't particularly want to have her head chopped off and her flesh eaten, and, you know, the ocean which is full of octopuses and sharks and fish, we can't be dumping pollutants and garbage and plastics into it, if these individual lives are going to suffer. We can't continue to alter the climate of our world if we realize it's full of lives just as wondrous as our own.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas are co-authors of Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind. Thank you both for spending this time with us.

THOMAS: Oh, thank you so much for having us.

MONTGOMERY: We're so glad that you came.

Related links:

- Chelsea Green Publishing webpage on Tamed and Untamed

- More about author Sy Montgomery

- More about author Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

- Boston Globe column on chickens, written by Sy Montgomery

MUSIC: Ted Weems un Sen Orchester, “Chick Chick Chick Chick Chicken,” Charleston, (Holt/McGhee/King, Electrola.]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth, damage to tropical forests is making global warming worse.

BACCINI: The threats are mainly anthropogenic. The first one is deforestation, but for the first time we were able to quantify the losses due also to degradation and disturbance.

CURWOOD: How the tropics went from soaking up carbon to releasing it. That’s next time, on Living on Earth.

[BARKING AND CHUCKLING SOUNDS OF WHITE-TAILED PRAIRIE DOGS IN UTAH]

CURWOOD: We leave you this week with a chuckling bark.

[WHITE-TAILED PRAIRIE DOG SOUND CONTINUES.]

CURWOOD: These white-tailed prairie dogs may be laughing at producer Jeff Rice in DeseretRanch in northern Utah as he’s recording their calls with a large parabolic microphone.

[PRAIRIE DOG SOUNDS CONTINUE]

CURWOOD: But their well-being may not be a laughing matter. These prairie dogs have lost much of their original range, due to drought and expanded grazing, but the Fish and Wildlife Service reckons they are still plentiful enough not to need Endangered Species listing.

[PRAIRIE DOG SOUNDS CONTINUE]

CURWOOD: Jeff Rice recorded these rodents for the University of Utah Marriott Library, westernsoundscape.org.

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Lean On Me” on Spirit, composed by Bill Withers, Jazz Legacy Productions]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Olivia Reardon, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth