December 29, 2017

Air Date: December 29, 2017

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Nesting Turtles at Home in Suburbia

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Habitat loss, speeding cars and other hazards have reduced the population of the locally threatened Blanding’s turtle in the Northeast. Grassroots Wildlife Conservation has teamed up with local residents to safeguard the nests that the turtles make in their neighborhoods. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering tagged along with GWC’s Bryan Windmiller and his team in Concord, Massachusetts to follow a mother turtle as she lays her eggs. (14:30)

Turtles Hatch!

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

Blanding’s turtles are considered a threatened species in Massachusetts, so Grassroots Wildlife Conservation is working to protect newly hatched turtles, as mortality is high in the first year. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman returns to the nest we observed in early summer with the biologists to find out how many eggs hatched, and help prepare the young turtles for their next adventure in local classrooms. (08:40)

Tiny Turtles at School

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

The tiny Blanding’s turtles that struggled out of the nest in summer are now getting a head start in life, fed and protected in school classrooms. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman visits the fifth-graders at the Carlisle (Massachusetts) School, and the two turtles they’re caring for, Tsunami and Squirtle. (05:30)

Wee Turtles Graduate

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

After raising Blanding’s turtle hatchlings all year, it’s time for a class of fifth-graders to send their charges back to the wild to make it on their own. Their care has given these threatened Blanding’s turtles a head start in life, and Living on Earth’s Don Lyman follows the children and the hatchlings to the Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, MA. (07:45)

Painted Turtles and Climate Change

View the page for this story

Climate change is impacting various animal species around the world, but painted turtles may face a particularly strange and formidable challenge. Host Steve Curwood talks turtles with Iowa State biologist Rory Telemeco. (06:30)

Snapping Turtle: Mark Seth Lender

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender sometimes explores his own corner of Connecticut. Walking on the bank of the Waterhouse Brook, he happened by the nest of a Snapping Turtle, just as the hatchlings were scrambling out of the soft soil to face the perils and opportunities of life. (03:20)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS:

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, it’s a special edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Threatened turtles face many dangers from predators, weather and traffic -- but they have many guardians.

WINDMILLER: Biologists assume that people are always the problem. And yet, here, the turtles are nesting in people’s front yards; they’re looking out for the turtles, they’re looking out for the nests; we have several thousand schoolkids in Massachusetts who raise young turtles for us, so people are in all kinds of ways directly helping out.

CURWOOD: Following their life story - from egg to hatchling to classroom – until the schoolkids that raise them all year send their charges off on their own.

OWEN: I mean I’m happy that they can go but I’m sad that we can’t take care of them anymore, ‘cause they’re so cute. So it’s like melancholy. I want them to get really large and die naturally, not from a predator – even though that is kind of naturally.

CURWOOD: How a head start program gives these baby turtles a leg up. That and more, this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Nesting Turtles at Home in Suburbia

The bright yellow throat of the Blanding’s turtle can help biologists recognize one from a distance (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is a special edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood. The turn of a year is a time for reflection, a time for looking ahead with hope and resolve and assessing the year gone by. These past twelve months have been eventful and full of drama, triumph, failure and achievement. But we’re not looking at politics today, we’re taking a close look at the struggles and successes of a species with an ancient lineage.

Over the past year or so, Living on Earth reporters Don Lyman and Jenni Doering have been following the life story of one of our native New England creatures, the Blanding’s turtle. And as Jenni reported from Concord Mass, the life story of the Blanding’s Turtle begins in high summer.

[SOUNDS OF BIRDS]

DOERING: On a summer evening at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, you’re surrounded by tall reeds, lilypads on shallow ponds, and turtles. And if you’re really lucky, you’ll spot the dark, high-domed shell and bright yellow throat of a Blanding’s turtle basking on a log. The turtles are right at home here, but Massachusetts lists them as a threatened species. That’s partly because young Blanding’s turtles face many dangers.

WINDMILLER: They’d have maybe a 1 in 80, 1 in 100 chance of living to be adults.

Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge covers more than 3,800 acres (Photo: Stephanie Liszewski / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

DOERING: That’s Bryan Windmiller, the Executive Director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation. The nonprofit is working to shift those odds and give baby Blanding’s turtles a better start in life – appropriately, by sending these youngsters to school so young humans can care for them and raise them for a year.

WINDMILLER: And we call that head starting -- you know, from like the human Head Start program – we give the little turtles a head start in life. We give them at least a forty-fold increase in their chances of surviving to adulthood.

DOERING: The head start cycle begins each summer during turtle nesting season, when Bryan and his team search for the mother Blanding’s nests to protect them. The headstart program is crucial because Blanding’s turtle hatchlings are an easy snack for predators. Their tiny half-dollar-sized shells are actually folded inside the egg and Bryan Windmiller says they’re still soft for months after they hatch.

WINDMILLER: So we take them when they’re at that real vulnerable stage and we give them to schools, and they raise the turtles for nine months, take care of them all winter, keep them warm, feed the turtles as much as they want. And in that environment, they grow super quick, so when we let them go, they’re on average about 12 times, sometimes 15 or 20 times heavier; they’ve got a much bigger shell, really strong shell; they don’t have to worry about chipmunks, they don’t have to worry about bullfrogs, they don’t have to worry about blue jays, and garter snakes.

DOERING: But natural predators aren’t the only hazards that threaten the turtle hatchlings.

WINDMILLER: Sometimes they’d be destroyed completely unintentionally by people, because sometimes they nest in farm fields that would get plowed, or they nest in people’s perennial beds that might get turned over and stuff like that.

DOERING: Bryan says that because of these threats -- from both natural predators and human development -- the Blanding’s turtle population here has been declining for decades.

WINDMILLER: There are only about 50 adult Blanding’s turtles here at Great Meadows, spread among a bunch of wetlands. And that’s down from probably 150 in the early 1970s. So our overall goal here is to help restore this population.

DOERING: And despite having just a few dozen adult Blanding’s turtles, the population at Great Meadows is actually the third largest in Massachusetts, and the fifth largest in the Northeast. So boosting numbers here could give the species a significant leg up locally.

WINDMILLER: We’re gonna start on our main business for the evening, which is looking for the moms. So we’ll start by going up in the tower and we’re gonna check with a radio tracking receiver, we’re gonna check on the signals of the moms that haven’t nested yet around here. And we’ll get a sense of where they are, and then we’re gonna go look for some of them.

[STEPS ON TOWER]

DOERING: The metal, twenty-foot-high tower overlooks most of Great Meadows and is a good high point for radio tracking. We meet up with Lea Kablik, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist who helps with the tracking. Lea turns on the receiver and holds the antenna over her head, pointing it in different directions.

[RADIO TRACKING SOUNDS]

Lea Kablik, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist, uses radio tracking equipment to try to find the nesting turtle (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: The beeping sound clues Lea in to where the turtle could be. It’s faint right now because this turtle’s not close.

[MORE RADIO TRACKING SOUNDS]

DOERING: Do they all sound the same?

KABLIK: Yeah, each beep sounds the same as all the others, it’s just knowing what frequency that you have programmed into the receiver.

WINDMILLER: The turtle has a radio station. And it’s just like all the turtle radio stations, the different radio turtle stations, are playing exactly the same tune – but you can listen to all the different ones that sound exactly the same just by dialing in your particular channel. So this year, altogether we’re tracking eleven females here at Great Meadows, one of whom we’re just not picking up a signal from; two have nested; and so with the one that’s not working, I guess that leaves us eight to run after right now. We should go start off looking for 2028.

DOERING: We drive to a quiet neighborhood just a short distance away. The lawns are well-kept, the backyards have big shade trees, and we see several residents hanging out on their porches on this fine June evening.

‘Why did the turtle cross the road?’ Perhaps to make her nest in a Concord neighborhood. (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

WINDMILLER: Yeah, well, we’re over at the side of this house, and this is where Chris and Stephanie and Lea last night tracked turtle number 2028, and they put a little thread bobbin on her just as a visual way of tracking her in case she decided to nest late at night. Blanding’s turtles almost always nest as it’s getting dark, and usually they’re done by 11 or so, but some of them like to stay really late, and we don’t, so if people need to leave, then sometimes we put these thread bobbins. So as the turtle walks, the thread just spools out until it runs out, and the turtle just walks away; they don’t detain the turtle, but unfortunately in this case, the thread broke, so now we’ll go find the turtle with her radio.

DOERING: Actually, it turns out a well-meaning neighbor thought the turtle was trapped, and the good Samaritan cut the thread. But on the whole, Bryan says, having the neighborhood involved is a great boon for turtle conservation.

WINDMILLER: If you do it right, if you involve the people to the extent that you can – the local human population can be an asset for conservation, instead of a problem. Because that’s the tendency – biologists assume that people are always the problem. And yet, here, the turtles are nesting in people’s front yards; people are on – you know, they tell us, they call us when they see turtles, they’re looking out for the turtles, they’re looking out for the nests; we have several thousand schoolkids in Massachusetts who raise young turtles for us as part of this conservation program, so people are in all kinds of ways directly helping out.

[RADIO TRACKING NOISES]

DOERING: Lea starts moving around with the radio tracking equipment. Getting an accurate signal is proving difficult because the radiowaves bounce off of the flat sides of the houses. I ask Bryan where the turtle we’re looking for, number 2028, would most likely be nesting.

WINDMILLER: Well, if she’s going to be nesting, she’s going to be nesting in an open, relatively sunny place. There’s a good chance the turtle right now is just continuing to kind of hide in some of the shrubs and plantings near the house. Blanding’s turtles take a long time. The moms are really meticulous about finding a good spot to nest, and they almost never nest the first night that they come out of the water. They’ll often spend a few days, a week, sometimes, on land; sometimes they’ll walk around, we’re just like chasing them around these neighborhoods; and they dig a few holes there, don’t like it, dig a few holes there; and check out an area and sometimes they’ll go all the way back to the wetlands of Great Meadows, and they’ll hang out in the water and then come back a few days later and finally nest.

[RADIO TRACKING BEEPS]

DOERING: We keep searching for 2028, but she’s proving elusive. A resident comes up to Lea to say she’d seen the turtle not long before.

A Blanding’s turtle lays eggs in a nest at Borderland State Park in Massachusetts (Photo: Emilie Schuler / Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

NEIGHBOR: Okay, she was like right up on the pavement – and just wanted to let you know, that was the last time I saw her… maybe 45 minutes ago?

KABLIK: Oh really! Okay.

NEIGHBOR: Yeah, yeah. So it wasn’t that long.

KABLIK: Okay, Thank you.

NEIGHBOR: And I’m not sure how fast they move!

KABLIK: Surprisingly fast.

NEIGHBOR: It had the antenna and it had duct tape on it. She was basically where that watering can is. Right at that corner.

WINDMILLER: By far the loudest spot is still in the ivy here.

[BEEPING AND RUSTLING SOUNDS]

DOERING: Finally, Bryan locates the turtle in the front yard of the house next door.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, she’s in the mulch.

HICKLING: Looks like she’s digging right now. You can see the pile of mulch just behind her that she’s kicked out of the way right there, on the edge.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, she’s definitely working, she’s certainly trying to do something over there.

DOERING: We need to be really quiet and keep our distance to make sure we don’t disturb her.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, I mean you never know, the turtles are funny. Turtles who nest over here are obviously used to seeing people, and this turtle – we’ve caught this turtle – this is 2028 – I think we first caught this turtle ten years ago as a juvenile, it’s a pretty young mom. So she’s used to people. But just instinctively, Blanding’s turtles, all turtles are very wary when they’re first starting to commit to laying their eggs. Once they start laying their eggs, it’s like they go in a trance, and it doesn’t matter what’s going on around them, they’re going to try and finish. But before she actually starts laying her eggs and commits herself to her nesting spot, the best thing is to leave her be right now.

DOERING: While we wait, Bryan explains that the ponds at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge aren’t actually natural. People created them as duck ponds for hunting, and many of the turtles still living at Great Meadows were here first.

WINDMILLER: They predate Great Meadows. Those ponds were created in the 1950s. So a lot of the older turtles at least were alive before those ponds were created. So they’re used to, or at least were born into, a radically different environment. Henry David Thoreau caught a Blanding’s turtle at Great Meadows in 1854. He killed it because a buddy of his, Louis Agassiz, had started the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard and really wanted a Blanding’s turtle for his collection. So Thoreau gave him a Blanding’s turtle and then wrote in his journal about how guilty he felt over killing the Balnding’s turtle. And you can still see the Blanding’s turtle, it’s on display at the MCZ at Harvard. And so the turtles were here, but the environment was totally different. I mean you imagine, it was called Great Meadows because a lot of it was the wetlands, were kinda shallow, much more open but not ponds.

DOERING: An hour or so later we return to the nest site – and turtle 2028 is gone. Bryan gently digs in the mulch to uncover her nest.

Bryan gently digs in the mulch in front of a Concord home to uncover the first few eggs in turtle 2028’s nest. (Photo: Don Lyman)

WINDMILLER: There we go.

DOERING: That’s pretty cool.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, so we can just expose the top three eggs of her nest – actually you can see at least four. They’re about four inches deep. We’re very glad, she started about 7:30, it’s now about 11:30, looks like she pretty recently finished, so this is awesome. And this is really a typical kind of place for the Blanding’s turtles to nest here, she’s kind of near their stone paved walkway over to the front entrance of the house. And right in their mulch bed by their little perennial border about ten feet off the side of the house, a very nice spot for her nest. So now we’ll just cover it back up with dirt, like she did, like Mom did, and put a screen over it so raccoons and skunks can’t get it.

The first few eggs in the nest dug by turtle 2028 (Photo: Don Lyman)

DOERING: Bryan goes to the car to get the protective metal screen and stakes.

[METAL CLANKING SOUNDS; CAR DOOR SLAM]

WINDMILLER: So here in the suburbs it’s mostly skunks and raccoons. Foxes dig up turtle nests sometimes too. In this neighborhood in particular, there are a lot of skunks around here, and they’re very good at finding turtle eggs.

[METALLIC SOUNDS]

DOERING: Bryan thinks nesting Blanding’s turtles may intentionally find refuge in housing developments.

WINDMILLER: The great majority of them nest in places just like this, right by people’s houses. And at least I like to believe that the turtles have sort of figured it out that this is actually in many ways a better place for them to nest. First, they’re able to find these warmer little microhabitats, next to asphalt driveways, and little bits of landscape rock, and in mulched areas, where also the mulch will absorb some of the sun’s radiation. But in addition I think the turtles may have learned that when they nest in a place like this right up against somebody’s house, it’s really rare for raccoons and skunks to bother them.

[MORE METALLIC SOUNDS]

DOERING: He lays a square of chicken-wire mesh on the spot where the nest is buried and pushes metal stakes firmly into the mulch to hold it down.

Covering the nest with a mesh screen protects it from predators like skunks and raccoons (Photo: Don Lyman)

[METAL SOUNDS]

DOERING: With the screen in place, turtle 2028’s nest is protected, and for tonight, the work of Bryan Windmiller, Chris Hickling, Lea Kablik, and Grassroots Wildlife Conservation is done.

WINDMILLER: And then we just wait, and we put the temperature loggers down by the eggs to monitor the nest temperature so we can try and guess whether they’re gonna be boys or girls. And just wait until late August or September, when the babies come out.

CURWOOD: That’s Bryan Windmiller ending that report from Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation has joined Zoo New England

- 2014 report on GWC’s Blanding’s turtle project

- More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

- About Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

- Blanding’s turtle specimen caught by Henry David Thoreau for Louis Agassiz

- Watch a Blanding's turtle laying eggs

[MUSIC: Vusi Mahlasela, “Say Africa,” Say Africa, Dave Goldblum, ATO Records]

https://soundcloud.com/ato_records/vusi-mahlasela-say-africa

CURWOOD: Coming up – the next step in the life story of baby turtles’– That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth -- stay tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Punch Brothers, "Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, Allegro" on Live From the Lower East Side: It's p-Bingo Night! written by Johann Sebastian Bach, Nonesuch]

Turtles Hatch!

A baby Blanding’s turtle takes its first swim (Photo: Don Lyman)

CURWOOD: It’s a special Living on Earth today, and I’m Steve Curwood, revisiting the threatened Blanding’s turtles that go to school. In midsummer, our reporters went out with a team of biologists monitoring the Blanding’s’ turtles as they laid their eggs. A few months later, as the days grew shorter, Bryan Windmiller returned to Great Meadows in Concord Massachusetts to check on the nests with a couple of young assistants.

MARCO: I’m Marco. I am twelve.

ANA GRACIA: I’m Ana Gracia. And I’m ten.

WINDMILLER: It’s now – today’s, this is September 11th, right? So this is starting to get well into the period where the turtles are often hatching.

CURWOOD: Bryan is the executive director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, and he’s concerned about what effect the drought might have had on the nest of Turtle number 2028. That’s the mother we encountered when she laid her eggs back in June and this time, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman went along with Bryan as well.

A sponge helped keep Turtle 2028’s nest damp during the dry summer (Photo: Don Lyman)

WINDMILLER: Right now, just to make sure that things are okay we’re gonna just scratch down and take a look just at the topmost couple of eggs, and just see if those eggs look okay.

LYMAN: Bryan opens the wire mesh cage that surrounds the nest to protect it from predators like skunks and raccoons. There’s a large, yellow sponge on top of the soil -- to keep the soil moist, says Bryan.

WINDMILLER: We water the sponge, and we usually overwater it so we’re actually watering the nest a little bit, too -- the soil’s been so dry so just to make sure that the eggs aren’t dehydrating. The only thing is we didn’t start doing that until into August, and it was incredibly dry before then, too. So our concern is that maybe some of the embryos might have perished back in July, when it was really hot and dry as well. So, Ana Gracia and Marco, you guys can take some turns.

LYMAN: Marco and Anna Gracia carefully dig into the nest with their hands. And pretty soon…

ANA GRACIA: It’s a turtle!

MARCO: It’s alive.

ANA GRACIA: Ooh, let me see him!

WINDMILLER: That, I was going to say, is the other thing that we sometimes find is you dig down and you find that the turtles have hatched already.

Marco, 12, looks on while his ten-year-old sister Ana Gracia carefully digs in the dirt of Turtle 2028’s nest. (Photo: Don Lyman)

ANA GRACIA: He’s okay, he’s so cute!

WINDMILLER: Looks wonderful. I’ll go turn the hose on.

ANA GRACIA: He’s teeny!

MARCO: He does weigh as much as a quarter.

ANA GRACIA: He weighs less than a quarter.

[WATER SOUNDS]

WINDMILLER: Yeah, you can soak it for a second and we’ll also soak the nest.

LYMAN: Ana Gracia rinses the little Blanding’s turtle off with a garden hose and puts it in a plastic tub with some water.

ANA GRACIA: He’s swimming. I was kinda surprised that they could swim, like, the second they got out.

WINDMILLER: …moisten the sponge. That one looks really good!

Ana Gracia rinses off the little turtle hatchling she found in the nest (Photo: Don Lyman)

LYMAN: Bryan thinks it’s best to leave the nest alone at this point, so the rest of the hatchlings can dig their own way out. When they do, these hatchlings will go to school – literally. Bryan entrusts them to school kids like Marco and Ana Gracia, who care for them in their classrooms and give them a head start in life.

A couple of weeks later, we’re back at the nest with Bryan Windmiller and program coordinator Emilie Schuler. Bryan says no baby turtles have emerged since Marco and Ana Gracia found that first one nearly two weeks ago.

WINDMILLER: Typically, we don’t see more than a week or so that goes by between when one hatchling emerges and when everybody else does. And we’ve found that rain often seems to motivate the hatchlings to come out of the ground, and we actually had one fairly decent rain just about three days ago, four days ago.

LYMAN: And time is running out, Bryan says, for the cold-blooded turtle hatchlings.

WINDMILLER: At this point, because the weather’s cooling down, it becomes harder and harder for the hatchlings that are underground to have the energy to dig themselves out.

LYMAN: Bryan and Emilie take off the mesh cage that’s been protecting the nest.

WINDMILLER: Okay, you gonna go for it, Emilie?

SCHULER: Okay.

[DIGGING SOUNDS]

SCHULER: Oh, what’s this – Oh, that’s the—

WINDMILLER: --Temperature logger.

Grassroots Wildlife Conservation Program Director Emilie Schuler gently digs into the nest in search of any remaining hatchlings. (Photo: Don Lyman)

SCHULER: Temperature logger. Okay, well, we’ve got that.

WINDMILLER: So this records the temperature every hour. It will allow us to predict with reasonable accuracy whether the hatchlings are boys or girls.

[DIGGING SOUNDS]

SCHULER: So I think I’m seeing our first little friend here. There’s a something, some egg and some movement.

WINDMILLER: Oh! That’s looking good.

SCHULER: There’s movement. There he is.

WINDMILLER: It’s a little one.

SCHULER: Awww.

WINDMILLER: Yeah, wonderful! Looks like that one, too, has been hatched for a little bit, just been sitting there.

LYMAN: Emilie digs down further into the nest.

WINDMILLER: So Emilie just dug up – here’s an egg, that -- you can feel, it’s got a-- a formed embryo inside of it. But I’m suspecting that, uh—

LYMAN: It might not be alive?

WINDMILLER: Yeah, that it’s not viable anymore. This also, this nest may be pretty small because this was a first-time mom, and first-time moms often lay pretty few eggs compared to the normal average of about ten.

Turtle 2028’s first clutch of eggs yielded two live hatchlings, an eggshell without an embryo, an egg containing an embryo that never developed into a turtle, and a tiny hummingbird-sized infertile egg. (Photo: Don Lyman)

LYMAN: Oh, looks like some more eggs there.

WINDMILLER: Mm-hmm.

SCHULER: Yep, but, again –

WINDMILLER: So this one doesn’t have an embryo in it.

LYMAN: How can you tell?

WINDMILLER: You feel it’s really light, it’s all dried up.

LYMAN: Oh yeah.

WINDMILLER: And that may be pretty much the nest, right?

SCHULER: There’s something else down here.

WINDMILLER: Ah, is there? Oh, yep--

SCHULER: Oh!

WINDMILLER: Oh, I’ve seen that before.

SCHULER: Look at that! A tiny egg!

LYMAN: So tiny. Why is it so tiny?

WINDMILLER: So that’s also something that we saw once before with a first-time mother, right across the street from here, who -- you know, you could tell she was sitting there working, laying, and then very carefully burying things. And we always, when we put the screen over the nest we dig down just to make sure that she actually laid eggs, and we were quite sure that she’d done something, but I dug down, and I didn’t see anything, and I kept digging down, and I just had one little tiny egg – you know, this is the size of a parakeet egg.

LYMAN: Or maybe a hummingbird egg.

The tiny turtle hatchling Emilie excavated was only a bit bigger than a quarter. (Photo: Don Lyman)

[LAUGHING]

WINDMILLER: Or maybe a hummingbird egg, this is not the size of a Blanding’s turtle egg! I think it’s just something physiological about first-time moms.

LYMAN: Bryan says he’ll dissect the egg that has an embryo inside, but not yet, because—

WINDMILLER: My wife, who is a wildlife veterinarian, always reminds me – when you work with reptiles, their metabolisms are so slow, it’s not always easy to tell when they’re dead or not!

LYMAN: Oh!

[LAUGHING]

WINDMILLER: So, so I will take that egg, actually. And I’m gonna take a little bit of the soil over here, and just in case, you know, I’m wrong, I’m just gonna put it in a container for a little bit, just to see if anybody does hatch from it before I break the shell open.

LYMAN: All in all, Turtle 2028 laid four eggs in her nest.

WINDMILLER: That’s less than half the size of a typical Blanding’s turtle clutch. And two out of the four survived, which is also low.

LYMAN: Normally about eighty percent of the eggs produce hatchlings. The low survival rate of the eggs of these threatened turtles seems to be a trend this year in New England.

WINDMILLER: We did hear from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, they’re monitoring the only relatively large population of Blanding’s turtles left in Massachusetts, and I believe they had 59 nests that they monitored this year. And their average hatching success was just over 5 hatchlings per nest, and that’s very low. And I would put up drought as my first guess as to why that’s been the case.

Bryan Windmiller founded Grassroots Wildlife Conservation (now part of Zoo New England) and is now Director of Zoo New England's Conservation department. (Photo: Grassroots Wildlife Conservation)

LYMAN: Since as many as 80% of Blanding’s turtles don’t make it through their first winter, Grassroots Wildlife Conservation steps in. The turtles grow much faster when cared for by humans than in the wild, Bryan Windmiller says.

WINDMILLER: By the time we let them go they’re usually the size of, say, a wild four-year old. The first year their survival rate is really high, it’s around 85, 87%. And by the second year after we let them go it’s around 96%.

LYMAN: The tiny Blanding’s turtle that Emilie unearthed from the nest of turtle 2028 may have come from a small clutch, but the nine months of boarding school that awaits it gives this little guy – or gal -- a good shot at living a long and productive life.

WINDMILLER: The good news is we’ve got a baby who looks healthy. And this is the second one from this nest. And we have a lot of fourth graders in Concord who are really looking forward to meeting their turtles.

Related links:

- Watch a Blanding's turtle laying eggs

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation has joined Zoo New England

- 2014 report on GWC’s Blanding’s turtle project

- More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

- About Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge

[MUSIC: Manasse/Nakamatsu, Three Preludes “Allegro ben rimato e deciso,” American Music For Clarinet & Piano, George Gershwin/arr.James Cohn, Harmondia Mundi USA]

Tiny Turtles at School

One of the hatchlings that Chris Denaro’s class cared for at the Carlisle School during the 2016-2017 academic year. (Photo: Don Lyman)

CURWOOD: When we last paid a visit to the baby Blanding’s turtles, it was early October. They’d just hatched from the nest of Turtle 2028, and were ready to be sent to classrooms to be raised by Massachusetts’ schoolkids for a year. And in deep winter, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman took a trip to an elementary school doing just that, a few miles outside Boston.

[SOUND OF KIDS CHATTERING IN HALLWAY]

LYMAN: On a clear but cold February day, snow from a recent storm blanketed the outdoor basketball courts at the Carlisle School. But inside the tank where two young turtles lived, it was a balmy 80 degrees or so, and the classroom itself teemed with excitement.

[TEACHER CLAPS FOR ATTENTION]

LYMAN: I found myself among perhaps the only people with more questions than journalists: fifth graders.

SCHULER: You guys have so much curiosity about turtles! This is amazing. Yes.

LYMAN: Chris Denaro’s students grilled Emilie Schuler, the Director of Programs and Operations at Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, about everything from how many turtles are left in the world, to potential hazards the littlest ones face.

STUDENT: Do people step on those turtles?

SCHULER: They might. Yeah I’m sure and a small turtle like this it probably could get crushed by a person stepping on it.

LYMAN: The kids were in the midst of a yearlong project to take care of two baby turtles, to give the hatchlings a head start in life, so they’d have a much better chance of surviving to adulthood and boosting the threatened species’ numbers when they’re released in the spring. One of those babies was from Turtle 2028, the mother we followed starting in July 2016. By now the kids were pros at feeding the turtles, giving them fresh water and weighing them, but they still had lots to learn about some amazing things the hatchlings – which they’d named Tsunami and Squirtle -- could do.

SCHULER: Okay, so today we’re gonna be learning all about your turtles and some really cool superpowers that your turtles have. Some things that turtles can do that humans can’t do. Did you guys know that turtles have superpowers?

STUDENTS: No…? Yes…?

LYMAN: During the harsh New England winters, those superpowers are essential for survival. Tsunami and Squirtle had it easy in their warm and artificially-sunny tank, but the kids who cared for them always had to bundle up during recess. We humans have to keep our bodies near a toasty 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit. If a human’s body temperature drops below that by even a few degrees, we can quickly succumb to hypothermia. But Blanding’s turtles can chill to just above freezing.

SCHULER: Can a turtle’s body – is it okay for a turtle, for its body to be 33 degrees?

STUDENTS: Yeah…? No…?

SCHULER: Yeah! Right, that’s the really cool thing. It’s like kind of a superpower of turtles and of reptiles that they can have their body so, so cold. They can drop their body temperature like that and still be fine.

LYMAN: In order to still be okay with such a low body temperature, Blanding’s turtles have to slow down. Waaay down.

SCHULER: They’ve measured turtles that are this cold, and their heart was beating only one time every ten minutes.

STUDENTS: Whoa!!!!!

LYMAN: It sounds incredible, but that’s normal for turtles in winter, part of a nifty adaptation that allows them to slow their metabolism way down. And when that happens, they need a lot less oxygen. They still need some – and can absorb small amounts through their skin. And they have another trick up their shell.

SCHULER: So turtles have the ability to hold their breath for a really, really, really long time.

LYMAN: Like – for months.

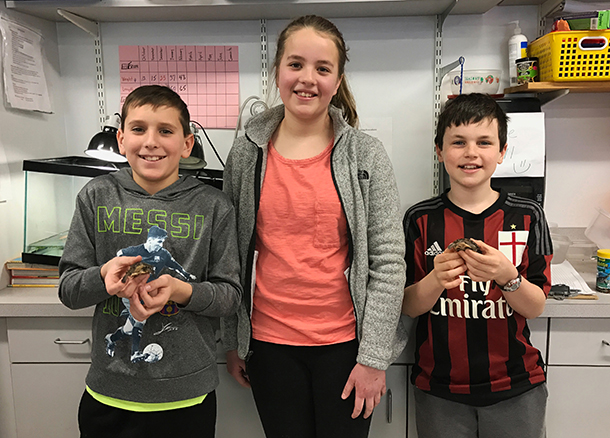

Carlisle fifth graders Ian, Sienna, and Owen with their class’s two Blanding’s turtle hatchlings. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

SCHULER: Scientists have even done studies where they’ve purposely, they’ve put turtles in water where they’ve bubbled out all the oxygen. Those turtles stayed under the water super-chilled for five months.

STUDENTS: What?!!?... Oh my!

SCHULER: So those turtles were holding their breath for five months. Is that a cool superpower or what?!

STUDENT: That’s cool.

LYMAN: But a metabolism that’s barely detectable is not so great for growing up big and strong.

SCHULER: So. Your Blanding’s turtle cousins that are outside, right – Tsunami’s cousins that are not lucky enough to be in classrooms today – are outside. Maybe, right, in the swamps of Great Meadows, under the ice right now. And they’re gonna be surviving over the winter. Pretty cool stuff that they can do that. But. Those cousins that are out in the winter right now— are they gonna be growing like Tsunami?

STUDENTS: No.

SCHULER: No. So even if they were the same age as Tsunami, come April or May, when it starts getting warmer and they come out – what’s the size difference gonna be between Tsunami and their cousins?

LYMAN: The answer: around 7 or 8 times the weight! That’s the main reason why the headstart program is proving so valuable for boosting Blanding’s turtle population numbers. In just eight months, the kids make the baby turtles look like four-year olds. So they’re less attractive to predators like raccoons, herons, and bullfrogs, and much more likely to make it out in the wild.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Don Lyman, at the Carlisle School outside Boston checking in on the 5th graders, and Tsunami and Squirtle – the two tiny Blanding’s turtles they’re raising in their classroom to give them a leg up in life.

Related links:

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation has joined Zoo New England

- More about the Blanding’s turtle from the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife

[MUSIC: Childsplay, “Bob’s Child” on Twelve-Gated City, Matt Glaser, self-released by Childsplay]

CURWOOD: Coming up – it’s turtle graduation day! That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth! Don’t hide in your shell!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski, Martin & Wood “North London”, Juice Indirecto Records 2014]

Wee Turtles Graduate

Benji Miranda checks a turtle trap at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge on a field trip (Photo: Don Lyman)

CURWOOD: It’s a special edition of Living on Earth, all about turtles. I’m Steve Curwood. We’ve followed the progress of some threatened Blanding’s turtles from the time the eggs were laid near Great Meadows in Concord Massachusetts, through their hatching, and their stay in a school classroom. There, the kids named them Tsunami and Squirtle, fed them, cared for them and learned all about them, until it was time to return the turtles to their wild home. So on a bright June morning, Living on Earth’s Don Lyman headed back to Concord.

[SCHOOL BUS BRAKING]

DENARO: Hi, how are you? Nice to see you again.

[CLASS CHATTERING OUTSIDE AMBI]

DENARO: Listen up!

LYMAN: We meet up with the Carlisle School fifth graders at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge in Concord, Massachusetts, where Bryan Windmiller, the Executive Director of Grassroots Wildlife Conservation, is back in his waders, with an assistant.

WINDMILLER: Good morning, guys.

STUDENTS: Good morning.

WINDMILLER: So, I’ve met you guys – I’m Bryan Windmiller, this is Benji Miranda, who works with me. We’ve got a beautiful morning to go out and check out the habitat where your turtles are going to be living.

[CALL OF RED-WINGED BLACKBIRD]

LYMAN: The class starts down the tree-lined path that leads to the ponds at Great Meadows. It’s a pleasant spot; beyond the trees, cattails wave in a light breeze over the deep-blue ponds. Butterflies and red-winged blackbirds flit through the air, and occasionally you might see a Great Blue Heron take to the sky. Yet while it looks natural – it’s very much not.

WINDMILLER: All around here – we have a real mix of plants and animals that are both from here – that started out here so they’re native – and there are also lots of species that got here only recently, because people – whether on purpose or not – have brought them. These beautiful smelling roses – I’m getting all the perfume from these guys – this is an Asian rose, it’s called multiflora rose. So it’s only here because people brought it here. They thought it looked good, the blossoms smell really good – and now it’s all over the place.

Students walk along the path dividing the man-made ponds at Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge before releasing their turtles into the ponds. (Photo: Jenni Doering)

LYMAN: Invasive species like purple loosestrife, Asian water chestnut, American lotus, and European carp have affected the makeup of flora and fauna here. And even the ponds themselves are not natural.

WINDMILLER: This whole place – as we walk along, you’ll see there are 2 big ponds that extend on either side. And this place is called Great Meadows, right? It’s not called Great Ponds. 80 years ago these were kind of scrubby meadows where people earlier in history from Concord used to graze their cows.

LYMAN: Then a man named Samuel Hoar, who owned 250 acres of land known as “Great Meadows”, decided to build low earthen dams, or dikes, to hold water within the meadows -- so that he could hunt the waterfowl that would be attracted to the ponds. But the change wrought by a private landowner who wanted to hunt ended up having a positive impact for some species.

WINDMILLER: We all know about all different ways in which people can affect the environment in ways that makes it harder for wild animals to live there. But in all kinds of ways, too, people can change the environment to help different kinds of wild animals. Whether it’s on purpose – Samuel wanted there to be more ducks so he could hunt them – but Samuel also made this better Blanding’s turtle habitat.

LYMAN: The turtles were here before the artificial ponds, and their population got a nice boost from the extra habitat. Then, as residential developments went up near Great Meadows in the latter half of the 20th century, and the turtles lost nesting habitat and fell victim to automobile traffic, their numbers dropped again. They’re now a threatened species in Massachusetts, so Grassroots Wildlife Conservation is working to get the adult population back to 200 from the 50 or so Blanding’s Turtles that live at Great Meadows now.

[GRAVEL CRUNCHING]

LYMAN: On the straight-as-an-arrow dike that divides the two man-made ponds, the group stops a couple times to check turtle traps Bryan and Benji had set earlier that morning.

MIRANDA: So these big ones are the ones we usually try and find the adult Blanding’s turtles in.

[SPLASHING SOUNDS]

LYMAN: Neither trap has any Blanding’s turtles – but there are several pretty Painted Turtles.

WINDMILLER: Anybody wanna hold this guy? So if you hold this guy, just remember, right? He’s a wild turtle. So – if you put your finger right in front of his face, what might he do?

STUDENTS: Bite it!

WINDMILLER: Bite you on the finger. So don’t put any part of your anatomy right in front of his face.

LYMAN: Soon it’s time to head back down the path to the parking lot. There’s a big metal observation tower at one end, where birders and other nature enthusiasts can peer down across the ponds to spot the many wildlife species that call this place home. Bryan gathers the group at its base to record some final data points about Tsunami and Squirtle before they’re released, and to deepen the notches in their shells that will help identify them when they’re recaptured, perhaps years later.

WINDMILLER: All right, what have we got?

STUDENT: 74…

WINDMILLER: 74 point zero. Thank you Squirtle. Okay, so, who’s got the data sheet? Awesome. So he’s now, right, 7 times heavier than he was when you got him, and when he hatched he would have probably been even a little less than that. So probably 8 times heavier now. Right? Which is a huge difference. And when they get to be fully adult, right, in their late teens or early twenties, they get to be -- a big Blanding’s turtle around here will be about 1,800 grams. So you guys need to get back; and Tsunami and Squirtle need to get going. So if you want to go up on the tower – and you can array yourselves, some of you on the top, some of you on the stairs.

[FOOTSTEPS ON TOWER STAIRS]

LYMAN: From the tower they watch as Bryan and Benji wade between cattails, to a nice shallow spot in the ponds.

STUDENTS CHORUS: Nooooo they’re leaving! Guys, the turtles are leaving… They’re going away!... It’s their first time in the water other than their tank.

Bryan Windmiller and Benji Miranda wade between cattails at Great Meadows to release “Tsunami” and “Squirtle”. (Photo: Don Lyman)

WINDMILLER: So, first we’ll let Squirtle go. Do you guys wanna say goodbye to Squirtle?

STUDENTS: Bye Squirtle!...

WINDMILLER: So now we’ll let Tsunami go. You guys can say goodbye to Tsunami.

STUDENTS: Bye Tsunami!

LYMAN: One kid, Owen, isn’t quite sure how to feel about saying goodbye.

OWEN: I liked watching them grow, it just made me happy to see them getting bigger and that they’d be released. I mean I’m happy that they can go but sad we can’t take care of them anymore because they’re so cute. So it’s like melancholy.

LYMAN: What do you wish for the turtles?

OWEN: I want them to get really large and die naturally, not from a predator. Even though that is kind of naturally. But still.

LYMAN: Judging by the high survival rates of turtles that have gone through the headstart program in years past – Owen may very well get his wish.

WINDMILLER: What’s really cool is we just found a turtle who is from 2028, who was released last year; the previous class found him right about here, walking across the path.

LYMAN: And a few days later, as night fell -- exactly a year and one day after number 2028 laid the eggs that would include Tsunami -- Bryan reported that she was just finishing up her nest in someone’s front yard, across the street from where she laid her eggs last year.

The eggs looked normal – there were 8 of them – and since Turtle 2028 had chosen a recently-delivered mulch pile for her nest, Bryan and his team gently moved them to a safer spot in the earth a few feet away. All summer long they’ll incubate in the warmth of the nest. And then, one day in autumn, these young Blanding’s turtles will poke through their shells, crawl up through the earth, and go to school. For Living on Earth, I’m Don Lyman in Concord, Massachusetts.

Related links:

- Grassroots Wildlife Conservation has joined Zoo New England

- Watch a Blanding's turtle laying eggs

[MUSIC: Mandala Octet, “The Last Elephant, Pt. 2” on The Last Elephant, Accurate Records]

Painted Turtles and Climate Change

Baby painted turtles heading back to the water (Photo: Rory Telemeco)

CURWOOD: Predators and careless humans aren’t the only dangers that turtles face – there are some more existential dangers, including global warming. Researchers from Iowa State University say there’s a danger climate change will warp the sex ratio of Painted turtles. Biologist Rory Telemeco says that’s because of the way the sex of turtles is determined.

TELEMECO: Painted turtles, along with many other reptiles, and some fishes and a few other things, have a different form of sex determination than what we generally think of in mammals. Mammals have their genotypes, their chromosomes determine whether or not you are male or female. We have XYs produce males, XX produces females. However in many of these reptiles, such as these turtles, the temperature during development, during a fairly short window of about a month, during the middle third of development, determines whether or not the offspring will be male or female with cool nests producing males and warm nests producing females.

CURWOOD: So what you’re saying is that warmer temperatures could mean more females?

TELEMECO: Potentially, though there are a number of ways that turtles could potentially buffer themselves from changing climate. We know these turtles have been around for a very long time. As a group, turtles have been on earth for 200 million years. The earth's changed a lot over that period. So they have to have some potential to respond to environmental changes. The question is, what avenues might work, and what avenues might not.

CURWOOD: So what did you do to determine the impact that climate change could have on the Painted turtles sex ratio?

TELEMECO: Well, the primary thing we were trying to get at, we wanted to know, will nesting earlier in the year be a mechanism that could buffer these populations from climate change? We know that shifts in the onset of reproductive events, really any major event in the life of an animal - these are called phenological changes - are changing really, really rapidly. That's basically what we see when we go out and we try to measure how is climate change affecting organisms. We see flowers blooming earlier. We see leaves bursting earlier on trees. Birds and butterflies are migrating earlier. Frogs are singing earlier, and things like turtles and lizards are nesting earlier in the year. It’s a really common response. And this leads to the question, well, are these organisms buffering themselves from climate change by nesting and doing their things earlier in the year when it’s a little cooler? We really wanted to know whether or not that was going to work. And so, we looked at these turtles, we have 25 years of research on a single population of Painted turtles in the Mississippi River. We took all of that information. We put it into a mathematical model, and what we actually found is that nesting earlier in the year by itself does very, very little good. If that’s the only thing that the turtles had at their disposal, to try to sort of protect themselves from climate change, it would only buffer them to about a degree increase in temperature. Any more than that, it would have no buffering effect. We’d expect to see complete 100 percent female sex ratios in these populations, and potentially even really high mortality in the nests of these populations as well.

A nesting painted turtle (Photo: F.J. Janzen)

CURWOOD: So you’re talking about one degree Centigrade?

TELEMECO: Yeah. We’re actually expecting four or more degrees Centigrade increases in the midwest over the next century. So this mechanism by itself really seems like it’s going to be ineffective.

CURWOOD: And why is that?

TELEMECO: Well, if you think about how temperature changes over the course of a year -- it gets warmer in the spring and then levels off in the summer and gets cooler in the fall. You can think of a week in spring, temperature changes pretty rapidly, from Monday to Friday, you might have a major difference in temperature. In mid-July, from Monday to Friday, it might be pretty much exactly the same, it’s much more stable in mid-summer. So if say a female turtle, lays her eggs in the ground, at say, June 1st is the historic nesting date for our Painted turtles, she really wants that temperature to be predicting the temperature throughout the nest, especially when the eggs are actually sensitive to temperature as far as determining their sex, and that generally is the middle third of development. For our turtles historically, that would be July. If they advance their nesting date, so say they’re advancing a week or two – maybe now they’re nesting in mid-May. The nest’s temperatures are warming a lot more rapidly. While they might plant the eggs in the nest at the exact same temperature, on June 1 and May 15, because of climate change, the actual temperature the eggs experience by that middle-third of development, which is now mid-to-late June, is actually quite a bit higher than they historically were in July. What it basically means is that the females might be nesting at the exact same temperature year after year while nesting earlier, but because of this more rapid increase in temperature in early spring, later in development, the nests are actually warmer than they were before climate change, even with these fairly massive shifts in female nesting behavior.

CURWOOD: Because no one has told the turtles that, “by the way, maybe your eggs are going to be a lot hotter in the middle of July, so maybe you ought to lay them even earlier.”

TELEMECO: That’s correct.

CURWOOD: What about evolution here? Turtles have been around for over 200 million years surely there must be a way they could adapt.

Rory Telemeco with a Southern Alligator Lizard (Photo: M.S.C. Telemeco)

TELEMECO: There are many ways turtles could evolve and adapt to changing environments. The challenge is going to be that climate change is occurring so very rapidly. We’re expecting changes of four to eight degrees C within 100 years. And these turtles are fairly long lived. It takes them five years to be reproductive, and then they can continue to survive and be reproducing every year, for another 20 to 25 years, and that rate of generation time really slows the ability of populations to evolve. It means that you would need dramatic evolutionary changes within just a few generations for them to be able to cope with the types of environmental change we’re predicting over the next century.

CURWOOD: Rory, what if anything, can we do to prevent this?

TELEMECO: Ideally, we would cut back emissions, and do all the things that numerous political activist groups are trying to get done. We’re not going to be able to completely stop climate change, but pull it back and keep the climate from changing so much. Short of that, the things we can do to help support these organisms, or keep them from going extinct at least, are the same sorts of things we would do under any other circumstances. But it’s going to be really difficult and, sadly, I really don’t think we’re going to be able to save all of them.

CURWOOD: Rory Telemeco is a biologist at Iowa State University. Thanks for taking the time.

TELEMECO: Thank you very much for having me.

Related links:

- Rory Telemeco’s page at Iowa State

- The paper in The American Naturalist journal

[MUSIC: Josh Roseman “Purple Turtles” from New Constellations Live In Vienna (Enja Records 2007)]

Snapping Turtle: Mark Seth Lender

Baby snapping turtles push towards Waterhouse Brook. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: We stick with turtles – but a different species this time, observed by our resident explorer Mark Seth Lender. He often explores the river bank near his home in Connecticut where a snapping turtle has nested.

Snapping Turtle

© 2017 Mark Seth Lender

When the eggs were buried here above the stream, a milk snake came, black and agile and nosing into the earth that was softened by the digging out and hiding in. And took one. And then another one. And went away. Whether replete, or because his meal was disturbed, by being seen, impossible to determine.

Now, you would never know any of this. Or that anything lies there under the ground, waiting.

A snapping turtle explores the edge of the nest. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

It all looks the same across to the other bank. Or downstream. Or upstream. There remains no marker of where the snapping turtle climbed up, laborious and slow, undeterred by the angle of ascent, up between the rocks, the wet dirt spangled in vines and weeds. It was too long ago. Weeks, months in fact. The signs washed away in the rain. She scraped out her nest, the ancient claws working, working, the soft opalescent ovals dropped in a pattern one by one. Not too close. Each the right way up so the life inside, sleeping, eyes closed, would not drown in the long waiting to be born. She covered them and slipped and slid her way back to the stream that seemed then as now, much too shallow for the armored bulk of her shell, the flattened head, the toothless jaw like a bolt cutter and just as strong as that though made of blood and bone. She never came back. The Earth alone will be mother to what comes next:

The rotten branches and the leaf litter ground small by season and time are shivering.

The once and future place is trembling and rising and sinking.

Heaving.

Its surface breaking: Out of the ground that is quaking and roiling an army moves into the day light.

Forest adheres to the nascent shells, the hatchlings wet from birthing, their nostrils plugged with soil driven in by the force of climbing out. They come one on another fast, out of fear. But the only watcher will not harm them except to lift one into the palm of a hand for the sake of seeing what is seen never, or seldom:

A baby snapping turtle in a human hand for scale. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

- The dark of the eye.

- Iris with its bright rim.

- Sharp claws, the tiny limbs.

A rough place, the navel on the underside of the carapace, the only mark that tells, “We like you were nourished before we were born in a tiny replica of ocean, that Ocean From Which All Life Comes.”

CURWOOD: That’s our explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender – and there are pictures at our website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender’s Photography and Writings

[MUSIC: Ruben Gonzalez, “Date una vueltecita” on Momentos, Escondida/Cuban Essentials]

CURWOOD: Next time on Living on Earth: Dams in Africa generate power and help control floods – but at a cost to some communities.

PEARCE: So a whole series of livelihoods based around fish and farming and cattle herding have been seriously damaged, because the flooding simply doesn't happen anymore.

CURWOOD: How dams in sub-saharan Africa are feeding the refugee crisis. That’s next time, on Living on Earth.

[MUSIC: Ruben Gonzalez, “Date una vueltecita” on Momentos, Escondida/Cuban Essentials]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Don Lyman, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from John Jessoe and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening.

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes you, our listeners, and

from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its

School for the Environment, developing the next generation of

environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the

protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and

collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental

problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the

public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy,

from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from

SolarCity, America’s solar power provider. SolarCity is dedicated to

revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a

renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703.

That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER2: PRI. Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth