February 9, 2018

Air Date: February 9, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

America’s Toxic Schools

View the page for this story

Air pollution near schools can affect children’s health, intelligence and behavior. University of Utah professor Sara Grineski tells host Steve Curwood that her study published in Environmental Research finds more pollution in areas where poor and minority kids live and study. Among the worst affected school districts is in Camden, New Jersey where Keith Benson is president of the Camden Teachers Association. He tells Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb about the area and the health and cognitive problems he’s seen in his students. (10:21)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and host Steve Curwood examine recent developments in the Trump administration that undermine the regulation of toxic products. Plus, the duo discusses a withdrawn appointment to the Council on Environmental Quality and the USDA’s choice of a corn syrup lobbyist to help craft dietary guidelines. For the history lesson, Peter reminds us of a Clinton-era Executive Order meant to improve environmental justice. (04:07)

China Rejects US Recyclable Plastic

View the page for this story

The Chinese government has announced that it will no longer accept recyclable plastic from the rest of the world. Ann Germain of the National Waste and Recycling Association tells host Steve Curwood that the US needs to play catch up and find alternatives to recycle the masses of plastic waste we create every day. (05:54)

Plastic Trash to Cash

View the page for this story

There are roughly 5 trillion pieces of plastic sloshing around in the world’s oceans, the vast majority coming from the world’s poorest countries where proper disposal or recycling is unavailable. David Katz, founder of the Plastic Bank, tells host Steve Curwood about his company that turns plastic waste collected by poor people into currency they can use to buy goods and services. (06:53)

Children & Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know

View the page for this story

Rates of childhood asthma, learning problems, and cancer have been on the rise for decades -- and toxic chemicals, most of which are never tested for safety before they're sold, appear to be major culprits. In this conversation with host Steve Curwood, pediatrician Philip J. Landrigan connects the dots between exposure to environmental toxins and disease and shares strategies parents and child advocates can use to keep kids safe in a world full of pollution and awash in thousands of chemicals. Philip and his wife Mary Landrigan are co-authors of the new book, Children & Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know. (19:09)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Sara Grineski, Keith Benson, Ann Germain, David Katz, Philip Landrigan

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International, this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood. Children today are suffering a lot of learning difficulties, concentration problems, autism, and asthma and experts point a finger at chemicals.

LANDRIGAN: The government in this country is not doing a good job of protecting children against toxic chemicals. They’re simply given a free pass. They're allowed to come into the market, they go into products, they get out into the environment. And then, sadly, time and time again, we have found out the hard way that these chemicals damage children's health.

CURWOOD: Research finds pollution is hurting the minds and bodies of America’s school children.

BENSON: We might be losing whole generations of kids that had potential in greatness simply because of things that they could not help and people chose not to address like water and air.

CURWOOD: Children at risk and more this week on Living on Earth – stick around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

America’s Toxic Schools

Students’ intelligence and ability to learn is negatively impacted by exposure to air pollution. (Photo: Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

[SOUNDS OF SCHOOL CHILDREN]

CURWOOD: School is supposed to be a safe environment, but a recent study in the journal Environmental Research has found that at many public schools children are being exposed to harmful levels of air pollutants. In fact out of nearly 90,000 public schools studied only 728 had the safest possible score. This study found the five worst polluted areas included New York, Chicago and Pittsburgh as well as Camden and Jersey City, based on air quality measurements of more than a dozen neurotoxins, including lead, mercury, and cyanide compounds. Study lead author Sara Grineski is a professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Utah and joins us --Sara, welcome to Living on Earth.

GRINESKI: Thank you, I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, tell me which chemical pollutants did you look at in your study and what are the sources of that pollution?

GRINESKI: Sure. These would be chemicals like lead, mercury, toluene, manganese, polychlorinated biphenols, things like that, and the sources of these kinds of chemicals are industrial activities, combustion engines, refining, waste incineration and mining.

CURWOOD: So, what are the potential health implications for people? I'm thinking especially of children who are exposed to these chemicals.

GRINESKI: For a long time, researchers were focused on ingestion of these sorts of chemicals in our food or paint chips from the walls in old homes, but there's evidence that when you inhale these types of toxins, the toxins gain entry to the body, and then the body mounts an immune response which causes swelling, and this neuroinflammation in the brain leads to the damage of neural tissues. It's been linked to autism, ADHD, and later in life, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease. All kinds of neurological conditions are starting to be traced back to having, you know, an environmental component to their origins.

CURWOOD: Wow. So, these are issues that can affect kids for the rest of their lives then?

GRINESKI: Yes, exactly. That's why it's so scary. This neurological impact is so subtle and so insidious that it's hard to even know if your child has been affected or is being affected. You know, you wouldn't know if their math score would have been a little higher if they lived in a different neighborhood. I mean it's impossible really to discern this effect in your own children, and so I think it's difficult in that way.

CURWOOD: So, I understand that there's other research that has looked at the brains of healthy kids living with high exposure and found that they look like the brains of Alzheimer's victims. What can you tell me about that research?

GRINESKI: That was the research that's done by Dr Calderon at the University of Montana. So, she has access in Mexico City and also in other parts of Mexico and so she's done autopsies on children who have died in traffic accidents and in the non-polluted areas, in the rural areas, their brains look as one would expect, and in these polluted areas in Mexico City, the brains show signs of early signs of Alzheimer's disease, like the structure of the brain looks similar to people with early stage Alzheimer's.

CURWOOD: So, you looked at the air quality near some 90,000 schools across the United States. What did you find in terms of the best and worst results regarding exposure?

Camden, NJ sits just across the Delaware River from Philadelphia. (Photo: Dough4872, Wikimedia Commons)

GRINESKI: Well, we looked at the percentage of schools in the highest risk group, which we defined as the top 10 percent of all schools in the country for air neurotoxicant risk, and we found the greatest percentage which was actually fully one-third of schools in EPA region two, and EPA region two is New York City and New Jersey.

CURWOOD: We’ll come back to Professor Grineski in a moment. But right now we turn to Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb who reached out to a teacher in Camden, New Jersey right across the river from Philadelphia and where 11 of the 140 worst schools for air are located.

BASCOMB: Yes Steve, I caught up with Keith Benson, a former Social Studies teacher who’s president of the Camden Teachers Association.

BENSON: We have a higher rate of asthma. That’s really attributed to the poor air quality in this area. Also we have situations with students with learning disabilities, behavior disabilities. The outcomes of our state assessments tend to be lower but where before it might just have been attributed to either laziness on behalf of the student, laziness or ineffectiveness on behalf of instructors, the idea is getting more and more introduced that environmental factors like water and lead in the water might have a more pronounced impact on what it is we’ve been seeing for so long.

BASCOMB: Keith Benson describes Camden as a midsized city of 77,000 people surrounded by heavy industry.

BENSON: We have decaying shipping ports. We have cement factories. We have a trash to steam plant where all of the county’s trash and refuse comes to this plant. And that plant is within a stone’s throw of neighborhoods and apartments where a lot of young kids are growing up. And also they’re right near schools so kids are breathing this sort of toxic air essentially all their lives.

BASCOMB: As an educator and a parent himself, Keith Benson says it’s the lost potential of children in his city that troubles him.

BENSON: There’s really no telling actually what our students could have been if they simply would have had a healthy environment. You know, healthier air, healthier water, you know. And then when I start to think about it I’m like, damn, we might be losing whole generations of kids that had potential in greatness simply because of things they could not help and people chose not to address like water and air.

BASCOMB: 80% of the residents of Camden are African American or Hispanic and nearly 40% live below the poverty line. And the poisonous environment makes it even harder for people to get ahead.

BENSON: People live in these areas largely because we can’t really afford to live other places. Like, who would want to live in a place where the air quality is bad and there’s lead in water? You know, so when you see that students are really being put further behind the 8 ball. These families don’t come with a lot of money. You know, race does play a role in the opportunities that are being offered. And when you add another element that environmental racism plays on their development, you realize that a lot of chips are stacked against our children even before they reach adulthood.

BASCOMB: And Steve, it’s clear that the research backs up what Keith Benson says about the school children of Camden. Low income and minority children are disproportionately stuck in schools with poor air quality.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb, thanks! And now back to University of Utah Professor Sara Grineski, lead author of the study…so, how fair is it say this is a matter of environmental justice?

GRINESKI: This issue is clearly an environmental justice issue. Schools that have a higher percentage of black or African-American children, a higher percentage of Hispanic-Latino children, and a higher percentage of Asian children had significantly higher levels of the neurotoxicants in the area surrounding their schools. It's a pretty strong pattern, it's statistically significant, and it's quite notable that students from these racial ethnic minority backgrounds and also students who are poor are facing higher levels of these air toxics at their schools. So, there's clearly an injustice present that has contemporary and historical roots of the problem and is reflective of broader issues related to racial and class discrimination in the country.

A decaying industrial city, roughly 40% of the population of Camden, NJ lives below the poverty line. (Photo: Wikimedia)

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about the siting of schools and how that affected your findings.

GRINESKI: Schools are often located on cheap land, and it just so happens that, you know, cheap land is often land that's not desirable for other land uses. So, it's areas right near major freeways near other hazardous land uses, but only 10 US states actually have a policy in place to prohibit the siting of schools in areas that are known to be environmentally hazardous. The other 40 states and DC don't have a policy at all. And it is the case that schools serving pre-kindergarten students, like early childhood, publicly-funded early childhood centers, had higher levels of pollution than elementary schools.

CURWOOD: Well, wait a second. The youngest kids are the most susceptible to neurotoxicants. How did you feel when you found this research?

GRINESKI: It's quite surprising, it's depressing. We know that children are more vulnerable to air pollution than adults. They have less developed lungs. They spend more time outside. They consume greater quantities of oxygen per body weight, so their exposure is higher and then the consequences are likely greater because they are developing and they are changing and their cells are growing so fast. It's not a happy finding that we have our youngest students facing high levels of exposure.

CURWOOD: I wish I could say this is the first interview I’ve done on the dangers of pollution and exposure of kids to pollution, but we've done a number of them and it just seems to keep happening. What's to be done?

GRINESKI: Well, I mean, I think it's a really serious problem with ideas for solutions at multiple levels. We've been talking some about the need for a federal response, more policies and regulations, and I think that's really important from a top-down perspective, but I think we could drive that top-down change faster if we also push from the bottom up. So, you know more grassroots organizing, environmental justice activism that we could do at the community level, and then I also think in each of our own individual lives, those of us who have you know the economic freedom to make choices can try to drive less, consume less, eat more food that's grown in local areas, like, whatever you can do on your own to reduce air pollution and certainly everyone doesn't have the same opportunities to make those choices, but people that can certainly should do what they can to reduce their own levels of exposure.

CURWOOD: Sarah Grineski is a Professor of Sociology and Environmental studies at the University of Utah. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GRINESKI: You're welcome. It's been a pleasure.

Related links:

- Geographic and social disparities in exposure to air neurotoxicants at U.S. public schools

- LOE – Lead and Violent Crime

[MUSIC: Rokia Traore, “Dounia,” on Tchamanche, Nonesuch Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, a bank that trades in recycled plastic. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Genticorum, “Bonnet D’ane” on Malins Plaisir, composed by Jean-Francois Belanger, Roues et Achets Records/Conseil des Arts du Canada]

Beyond the Headlines

A new EPA plan may undermine toxicity evaluations of pesticides, industrial emissions, and radioactive materials. (Photo: veeterzy, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. Let’s check in with Peter Dykstra beyond the headlines in Atlanta Georgia now. Peter’s with Daily Climate dot org and Environmental Health News, that’s ehn.org and he’s on the line – how’s it going, Peter?

DYKSTRA: I’m doing well, Steve - hi. Let’s travel to Washington, DC, or as President Trump likes to call it, “The Swamp.” You got your boots on?

CURWOOD: Well, we were informed that the swamp might be drained by now, but if it’s not I think we’re going to need more than boots, I think we’ll need something more like waders. I’m ready when you are!

DYKSTRA: Right. First stop, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, where, shall we say, non-native species have taken over in the past year. A tiny EPA office called the Integrated Risk Information System – or IRIS – is under attack, and may disappear or get totally pulled under.

CURWOOD: So what does this Risk Information System, what does this IRIS thing do?

DYKSTRA: IRIS acts as an independent evaluator of how toxic certain products are – pesticides, industrial emissions, radioactive materials – in order to inform regulators at EPA on how to proceed. But the current EPA plan would put IRIS under the control of the regulators – specifically an EPA office now run by a former chemical industry lobbyist.

CURWOOD: Sounds to me like that classic case of the fox guarding the henhouse, Peter.

The USDA waived part of the Ethics Pledge requirements for Kailee Tckaz, who previously lobbied for the corn syrup industry. (Photo: Arshad Pooloo, Unsplash)

DYKSTRA: Or maybe the classic case of nobody guarding anything at all. But on to another development from the Trump Administration.

Kathleen Hartnett White, a top environmental regulator in Texas, withdrew her nomination to be the chair of the White House Council on Environmental Quality. Ms. White’s Texas tenure was marked by a steadfast denial that climate change was a problem, and remarkably, a declaration that fossil fuels were responsible for ending slavery.

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. All right, so remind us what the Council on Environmental Quality, what’s the CEQ supposed to do?

DYKSTRA: Well, the CEQ chair is considered to be the President’s top environmental advisor, and the agency acts, theoretically, as a bridge between other government agencies and departments to make sure that environmental concerns are a priority.

Kathleen Hartnett White’s nomination died once last year, President Trump re-nominated her, but it was clear that virtually all Democrats and quite a few Republicans were having none of it. And one more quick news item from the Swamp.

CURWOOD: Okay, fire away…..

DYKSTRA: If you can’t fully drain the swamp, fill it with delicious, beautiful, clean corn syrup!

CURWOOD: Well, that would be quite a swamp. How do you do that?

DYKSTRA: The White House legal office issued a special waiver to ethics laws to let a former corn syrup lobbyist who just took a job at the Agriculture Department sign on to the USDA’s five-year effort to set national dietary guidelines. Corn syrup is of course the ubiquitous and magical sweetener that’s in our sodas and many other products. It’s been linked to obesity, diabetes, and many other health problems.

CURWOOD: Oh boy, I can’t wait to see those new guidelines. Hey Peter, let’s take a look back now at environmental history, what do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Well on February 11, 1994, President Bill Clinton signed a sweeping Executive Order mandating that all projects using Federal funds take account of environmental justice – the huge and disproportionate impact that polluting projects have on poor and minority communities. Despite the best of intentions, nearly a quarter century later, environmental justice still takes a back seat in public and private projects.

CURWOOD: Yeah I mean, we were just hearing about high levels of pollution in schools in poor and minority areas. I guess the neglect that led to the drinking water crisis in Flint, Michigan demonstrates that as well.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, Flint and literally hundreds of other communities – whether they’re Federal projects or not, we’re still predominantly dumping on America’s poor and minorities.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but don’t hold your breath waiting for a new toxic landfill or diesel truck terminal to be built in, let’s say, Beverly Hills.

An Executive Order signed in 1994 mandates that all projects using Federal funds take into account issues of environmental justice. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Well, wherever they’re built, holding your breath is a good idea.

CURWOOD: Yeah, I guess so. Peter Dykstra is with environmental health news, that’s EHN dot org and Daily Climate dot org – thanks Peter!

DYKSTRA: Alright, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon!

CURWOOD: And if you want to check out these stories, there’s more about them on our website LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Intercept: “EPA division that studies the health risks of toxic chemicals is in a fight for its life – against the EPA”

- The Washington Post: “White House withdraws controversial nominee to head Council on Environmental Quality”

- International Business Times: “Corn syrup lobbyist helping set USDA dietary guidelines”

- Executive Order 12898—Federal Actions To Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations

[MUSIC: Buddy Rich, “Bugle Call Rag” on Buddy Rich: No Funny Hats, composed by Pettis-Meyers-Schoebel, Arr.Bill Holman, Lightyear/Lobitos Creek Ranch Records]

China Rejects US Recyclable Plastic

Workers sort plastic at a recycling plant. (Photo: National Waste and Recycling Association)

CURWOOD: China supplies the United States with everything from cell phones and computers, to TVs and washing machines, usually brought on large container ships.

And more often these days those container ship are taking American corn and other grains back to China, but there is a trade imbalance, and otherwise empty container ships can carry plastic and other recyclable materials to China at low rates. For years China wanted American plastic waste so it could recycle it back into consumer products. But no more. China has recently announced it will no longer accept plastic waste for recycling. Ann Germain of the National Waste and Recycling Association joins us to explain. Welcome to Living on Earth!

GERMAIN: Thanks. I'm happy to be here.

CURWOOD: So, why has China now decided that it no longer wants to recycle the world's plastic?

GERMAIN: So, first of all, China has looked at their environmental footprint, and so one of the things that they've been focused on is they don't want to be the world's dumping ground for everybody's trash, and part of their terminology when they instituted some of their bans reflects this. They refer to the material not as we do, which is as recyclables, but they refer to it as foreign waste. So, that is pretty indicative of how they view it.

CURWOOD: So, how many tons are we talking about? How much of the stuff that we're talking about has been going to China in the past?

GERMAIN: So, the total pounds of plastic bottles collected for recycling in the US was almost three million pounds, and that was for the year 2015. Of the total bottles, about 20 percent, were exported with the vast majority going to China.

Plastic ready for recycling. (Photo: Wikimedia)

CURWOOD: I imagine that China which has been recycling plastic for quite a while has developed some rather sophisticated methods for recycling.

GERMAIN: China has some of the most sophisticated manufacturing facilities in the world. Unfortunately, they also have some of the least sophisticated operations in the world where it's really mom-and-pop operations, family businesses that don't exhibit any environmental controls. As they're taking some of the material apart there might be, like, wrapping that comes around the bottles, other parts that they might end up disposing of and perhaps they're not managing some of that material appropriately and it might end up in the waterways or other pollution could occur as a result. And so we understand China's desire to kind of shut down some of those operations in an effort to improve their environmental outcome, but at the same time, we think given some of the more sophisticated operations that they have, there's no reason that those operations should be punished by banning these materials.

CURWOOD: So, what's China going to do to make up for the plastic that they're no longer importing and recycling. I mean, they have a use for it now. How will they fill the gap between the reduced supply of plastic and their continued demand for it?

GERMAIN: First of all, there is the opportunity to use virgin materials, but they've also targeted recycling domestically, and they're hoping that with their increased middle class, utilizing a lot of the same materials, generating some of the same packaging materials that they might be able to supply their manufacturing sector from domestic sources.

CURWOOD: Hmm. So, China doesn't want this stuff. Why isn't it good business for us to keep it here in America?

GERMAIN: Actually, it is good business for us to keep it here, but our manufacturers do compete with China for that material so it's a commodity and it is offered up for sale at the highest price. And so, some of it stays domestic and some of it does get shipped overseas. Now because of that, one of the things that's happened is we expect that there's going to be market adjustments that are going to be made and that domestic markets will further develop as a result of this ban. Unfortunately, those markets can't develop overnight. Unlike with other sectors where the mining industry can perhaps close down the mines for a little bit of time until the markets catch up, we can't shut off the taps for the recycling. It comes in, week in and week out. So, we need to have a use for that material.

Recycling plastic can be a small family business in China. (Photo: Wikimedia)

CURWOOD: So, what's going to happen with all the plastic that we're dutifully putting in our recycling bins here in the US? I mean, if there's a smaller market for this stuff, sounds like it's going to wind up in the local landfill.

GERMAIN: If that happens, it will be temporary and everybody is working really hard to try and find alternative markets as quickly as we can, so if anything ends up going to landfills, it will only be on a temporary basis and we don't expect that to happen to the really high quality materials.

CURWOOD: So, there's this perception that when we send our plastic water bottles and such to China that it comes back in the form of products, that this is indeed recycling. How real is that perception?

GERMAIN: Most of the material that we send over there kind of comes back, you know, in the form of other goods, not necessarily bottle-to-bottle. So, for example, some of the material end up in crates and buckets, films and sheets, lawn and garden products, other non-food bottles, things like that, lumber and decking. So, there's a wide range of different products that these materials can be made into and it's really...if you've got high quality product there, as long as it's the same plastic, there's no limit to what it can be made into.

CURWOOD: Ann Germain is Vice President of Technical and Regulatory Affairs for the National Waste and Recycling Association. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Ann.

GERMAIN: Thanks, Steve. I really appreciate you talking to me.

Related link:

National Waste and Recycling Association

Plastic Trash to Cash

A Plastic Bank worker picks up plastic bottles for recycling. (Photo: Plastic Bank)

CURWOOD: Well, only about ten percent of plastic waste in the US is recycled, with another 15 percent or so going to incinerators, leaving three quarters of all that plastic for disposal. And in spite of the efforts to burn, bury and recycle the stuff, much of it ends up in waterways and roughly 5 trillion pieces of plastic now litter the oceans, mostly circling in currents as 5 enormous garbage patches. It breaks up into smaller and smaller bits, and tiny flakes of plastic are eventually eaten by fish and birds and make their way up the food chain. People are working to clean up the plastic already in the oceans but some entrepreneurs are working to stop plastic from getting into the ocean in the first place. One solution may be what’s called the Plastic Bank, an anti-poverty financing scheme dreamed up and explained by its founder David Katz.

KATZ: We are now and have built out the largest chain of stores in the world for the ultra, ultra poor where everything in the store is available to be purchased using plastic garbage. Most proudly we offer school tuition, and medical insurance, Wi-Fi, power, sustainable cooking fuel, hi-efficiency stoves, and everything else that the world needs and can't afford.

CURWOOD: How does this work? How does somebody get involved? What do they have to do?

KATZ: They can earn a living by going door-to-door, or through the streets collecting material, and at the end of their collecting day, they can bring it back to one of our locations where it's weighed, checked for quality, and then that value is transferred into an online account. Plastic is money.

Workers bring plastic trash to a Plastic Bank center, where the plastic is weighed and the people get paid for recycling. (Photo: Plastic Bank)

CURWOOD: Where are you working and why did you choose those locations?

KATZ: Haiti is a requirement for the world. In our very back door is a catastrophe that is unfolding. The Philippines has been very profound for us as well, and we're just opening in Brazil. This year will be Ethiopia, and I think our entry into India will be through Delhi. Of the plastic that is entering the ocean, it is not surprising that it comes from those countries with extreme poverty. If you don't have power or food for your children, you have no consideration of recycling. It's not even in your realm of possibility. There is no garbage truck that comes by and picks up your waste. What you have is a stream, a river, a canal and the streets and that is the deposit. Most countries have two seasons. They have a collection season and a purge, the dry season where everything goes into the river bed and the rainy season when it comes in, it's all washed out to shore...out to sea, rather.

CURWOOD: How much plastic have you have been able to collect so far in Haiti, for example?

KATZ: Well, Haiti itself just in the few years we've been there has been a little over eight million pounds of material which equates to around 144 million bottles.

CURWOOD: And what do you call the project there?

KATZ: Ramassant l’argent in French Creole means picking up money, and that's exactly what they do.

CURWOOD: So, just how much do people get per piece of plastic?

KATZ: The value that people can achieve on a daily basis typically in Haiti can triple or quadruple their income. They are typically earning less than a dollar a day in what is predominately environmentally degrading industries, where here with recycling they can go from a dollar to four, and some recyclers are making up to six dollars a day. And it goes by mass, so the more that you collect, the more you make. It's an unlimited income opportunity.

CURWOOD: Talk to me please about a specific person that you work with who is collecting plastic and how the project has worked out for him or her.

Roughly 80% of the plastic that ends up in the world’s oceans comes from the poorest countries. (Photo: Plastic Bank)

KATZ: Well, Lize Nasis, that’s a story that we love to share. Lize has really never left Port au Prince. She as well survived 2010 earthquake that left her a widow, homeless and without an income, and beautifully, as a result of the program, she can afford her two daughters school tuition and uniforms which are very important, and beyond the realm of most people. It's a beautiful inspiring story. I was just in Haiti a few days ago and I saw her as well leading a group of other women in the collection of material. We're inspired by her, and we continue to work for her and other women like her, providing an opportunity for women to have power in the family.

CURWOOD: Where does the money come from to pay people for collecting this trash?

KATZ: We sell that material as a raw material to great companies like Marks and Spencers and German consumer goods company Haenkel and many others that then put that back into their manufacturing. For our customers, it allows them to engage their consumer. Buy a bottle of shampoo and you're directly collecting material from ocean bound waterways and alleviating poverty simultaneously.

CURWOOD: Sounds like you're saying that the companies that are taking plastic are considering this a marketing expense.

KATZ: That's exactly what they do.

David Katz is founder of The Plastic Bank (Photo: Plastic Bank)

CURWOOD: So, companies are willing to pay a bit more for this out of a sense of social responsibility.

KATZ: Yes.

CURWOOD: But you know when budgets get tight, or the CEO or the division head changes, somebody will look at the numbers there and say, “That was a nice thing to do, but we're not going to do it anymore”. How do you work this into the financial DNA of companies so that they see it as something that gives them value for their money?

KATZ: I've not yet found an organization that is not focused on building customers and keeping them, and customers today are voting and every time they buy something they vote for what they want to occur. Now, I'm in London and inspired by what occurs in Europe, and one of our customers, Marks and Spencers, is sharing the story with me that more and more customers are coming into the store, taking things that have excessive plastic at the counter, ripping off all of the plastic and throwing it back in the store. That is what is occurring today. There is a wave of change occurring and if you are listening to this, I'm going to ask you to do something like the same.

Every time you buy something with excessive plastic, every time you buy something with single-use plastic, you are voting for that to continue, and if you have some ambition about changing what is occurring in the ocean, then participate. There is a complete social media department in every one of those manufacturers, and any one of those brands, they're listening. And so, reach out to them, tweet to them, e-mail them, let them know that you don't stand for it and let them know that you want alternative packaging. They listen and they will eventually provide what customers want. That's what they do.

CURWOOD: David Katz is founder of the Plastic Bank. Thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

KATZ: Thank you.

CURWOOD: You can find out more about the plastic bank at our website, loe dot org.

Related link:

Find out more about the Plastic Bank

[MUSIC: Buddy Rich, “Slow Funk” on Buddy Rich: No Funny Hats, composed and arranged by Bob Mintzer, Lightyear/Lobitos Creek Ranch Records]

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121. Our e-mail address is comments at loe dot org. And visit our web page at loe dot org.

[MUSIC: Buddy Rich, “Slow Funk” on Buddy Rich: No Funny Hats, composed and arranged by Bob Mintzer, Lightyear/Lobitos Creek Ranch Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, How parents and communities can protect children from toxins in the environment. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners, and United Technologies - combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt & Whitney and UTC Aerospace Systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning in to the Race to 9 Billion podcast, hosted by UTC’s Chief Sustainability Officer. Listen at raceto9billion.com. That’s raceto9billion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Charles Mingus, “Better Git It In Your Soul,” on Ah Um!, Not Now Music]

Children & Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know

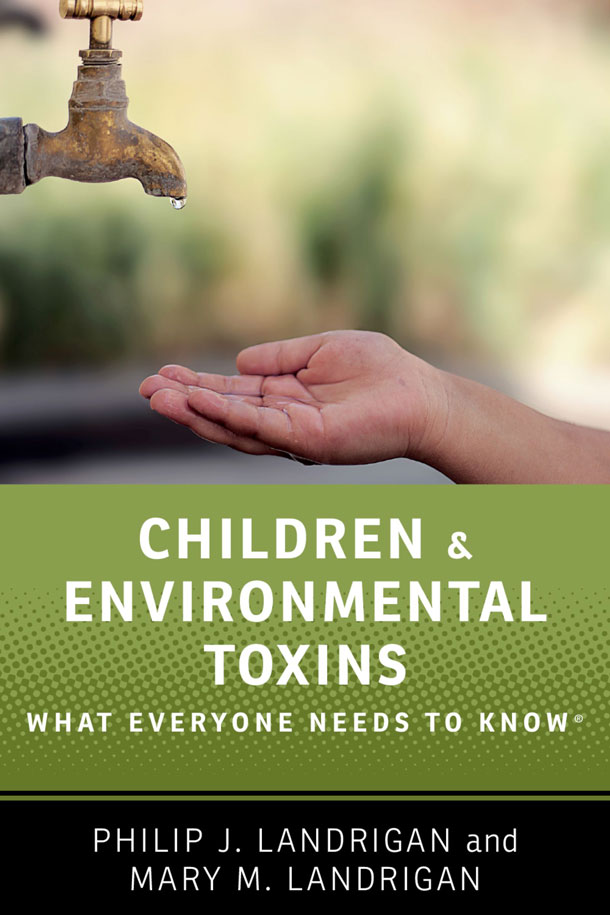

Children & Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know is especially useful for parents who want to know how to protect their children from toxic chemicals. (Photo: courtesy of Oxford University Press)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In their new book Children & Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know, Philip and Mary Landrigan bring together research on the risks chemicals pose to children in the form of a guide for parents, policymakers and the public. Philip Landrigan MD is Dean of Global Health and runs the Children Environmental Health Program at the Icahn Medical School at Mt Sinai Hospital in New York City. He joins me now. Dr. Landrigan, welcome back to Living on Earth!

LANDRIGAN: Steve it's great to be back with you.

CURWOOD: So what has changed about childhood health issues today from generations ago?

LANDRIGAN: Well I think the big change today from twenty five or fifty years ago is the extraordinary number of new manmade chemicals that have come into children's environment. These are chemicals that go into toys and cosmetics and soaps and household products and they're chemicals to which children are exposed to every single day.

CURWOOD: Now why do these chemicals pose such a risk to children's health?

LANDRIGAN: Well the fundamental problem is that the government in this country is not doing a good job of protecting children against toxic chemicals, and what I mean by that is that there is no enforced requirement in the United States that new chemicals be tested for safety or evaluated for toxicity before the chemicals come to market. The chemicals are simply given a free pass, they're allowed to come into the market, they go into products, they get out into the environment. And then, sadly, time and time again we have found out the hard way that these chemicals damage children's health. We really must do a better job in this country of assuring chemical safety and protecting children's health.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the health effects associated with these chemicals.

Dr. Phil Landrigan says avoiding certain particularly toxic cleaning products – oven cleaners and drain cleaners are especially harmful to health – can help reduce children’s exposure to these chemicals. (Photo: kleer001, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

LANDRIGAN: Well of course different chemicals have different health effects. Lead was one of the first toxic chemicals whose effects on children we discovered. And we now know that lead damages children's brains; causes loss of I.Q., shortening of attention span; disruption of behavior. And we've come to learn that those effects happen even at the very lowest levels of lead exposure to children; even a tiny dose of lead can be dangerous to a child's brain. Another class of chemicals are known as endocrine disruptors. These are chemicals that get into a child's body, interfere with the hormonal normal chemical signaling that takes place in the child's body and these disrupters can have very negative effects on a child's development. One class of endocrine disruptors are the phthalates. Phthalates are man made chemicals that are put into rigid plastics to make them flexible. They're known as plasticizers in the trade. Unfortunately the phthalates don't stay in plastics such as P.V.C. They escape; they get into food, and if phthalates get into a baby, especially if they get in by way of the mother, during pregnancy when the baby is still in the womb, these chemicals can mess up the development of the male reproductive organs in a baby boy and increases the risk of reproductive malformations. Phthalates can also damage brain development like lead, cause reduced I.Q. And then a third class of chemicals that have become very common in the modern environment are known as brominated flame retardants. Flame retardants are in couches, in carpets, in computers. The problem is they escape from those products; they get in the house dust and when a young child or a pregnant mom is exposed to them they too can get into the baby and cause brain damage to the baby with reduction in intelligence.

Lead paint still exists in millions of U.S. homes, especially those built before the 1970s. (Photo: Thester11, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: A number of years ago I attended a symposium you gave on the risks of some of these chemicals, and the relationship to learning disabilities; I believe there was a county someplace in North Carolina where you found a rather high incidence. What's the link between learning disabilities and some of these chemicals?

LANDRIGAN: Well, over the past fifteen or twenty years we have learned that a number of manmade chemicals can cause learning disabilities in children. These include lead; mercury; polychlorinated biphenyls, known as P.C.B.s; brominated flame retardants that go into carpets and couches; and a number of pesticides; and lastly a number of the endocrine disruptors such as phthalates and bisphenol A. And what happens is that if these chemicals get into a young child or if they get into a woman while she's pregnant, they get through into the mother's baby, they can cause injury to the brain of the child. And then that injury shows up when the child is two, three, four or five years old as slowed learning, diminished I.Q., short attention span, disrupted behavior; sometimes even attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, A.D.H.D.; and sometimes autism.

CURWOOD: And how common is this now?

LANDRIGAN: Learning disabilities are now calculated to affect one out of every six children born in the United States-- about fifteen percent of all American children. That data comes from the C.D.C. In Atlanta.

CURWOOD: What relationship do these chemicals have to the childhood obesity epidemic we're seeing?

Dr. Phil Landrigan is the Founding Director of the Children’s Environmental Health Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York City. (Photo: courtesy of Phil Landrigan)

LANDRIGAN: Well obesity is a complex story. And it's driven by multiple factors; new foods that are rich in fat and salt are a big problem; lack of exercise is a big problem; but chemicals also make a contribution. And there are some chemicals, actually some of the endocrine disruptors that can alter glucose and fat metabolism in the human body and tilt the scales in the direction of obesity. So if you have a child who's already not getting the right food and already not getting enough exercise and then that child is already exposed to some of these chemicals-- can tilt the balance.

CURWOOD: Childhood cancers seem to be on the rise; what are some of the theories on how might these be linked to chemicals?

LANDRIGAN: Childhood cancer is a good news/bad news story. The good news is that thanks to the heroic pediatricians at places like Boston Children's and St Jude's and other children's hospitals around the country, we save something like seventy five or eighty percent of kids with leukemia, and a very high proportion of kids with brain cancers-- leukemia and brain cancers are the two most common childhood cancers. But the bad news is that the incidence, which is to say the number of new cases per thousand children, has been rising steadily for the past forty years and more. We've seen a more than forty percent cumulative increase in incidence of cancer over this time. We know some of the chemicals that are driving this increase. We know that benzene can cause leukemia. There's a chemical called 1,3-Butadiene which goes into synthetic rubber and shows up in truck tires; there are various solvents that are in drinking water. But I don't think anybody can claim to know totally why rates of childhood cancer are going up; it still remains to be determined.

CURWOOD: Dr. Landrigan, you write that these health impacts can appear in childhood as well as much later in life. Why do some of these impacts take so long to manifest?

LANDRIGAN: Well the understanding has grown in the last fifteen or twenty years that negative exposures that occur to an infant in the womb or to a child in the first couple of years after birth can have negative effects all across the human lifespan. The very first studies that helped illuminate that question are actually studies of babies who were malnourished during pregnancy. And scientists in Great Britain who were studying children who have been malnourished during World War II in Holland found that when these children became fifty and sixty years old they had very greatly increased incidence of hypertension, heart disease, stroke, diabetes. Since that time we've come to understand that what's called fetal programming-- the changes in the expression of the genes in the infant in the womb, fetal programming-- can be caused not only by nutrition but also by toxic chemicals. And scientists are are beginning to explore this question now, map out how it happens. But I think it's becoming increasingly clear that toxic chemical exposures in early life are going to increase risk for a whole range of diseases when kids grow up-- everything from heart disease to cancer to kidney disease.

Phil’s wife and coauthor Mary Landrigan is a health educator who spent 25 years at the Westchester County Department of Health in New York. (Photo: courtesy of Phil Landrigan)

CURWOOD: Explain for me the concept that toxic chemicals can cause health problems without any symptoms, I guess what you folks call subclinical toxicity?

LANDRIGAN: Yes. It was during studies of lead, children exposed to lead that we first came to realize back in the 1970s that even very low levels of exposure to a toxic chemical, levels that are too low to produce any obvious symptoms in a child, could still cause damage to the child. And so when we started doing that work back in the seventies, the theory on lead poisoning was that it either made a child very very sick-- coma, convulsions, even death-- or the child recovered and that was the end of the story. But that seemed a little artificial to some of us, and so we started to look at children with lower levels of lead. Lo and behold we found that these children had loss of I.Q., behavioral problems; and that opened up the whole realization that low dose exposures to toxic chemicals could cause damage in children. And that's now become a very general recognition, almost any chemical you can think about has a range of exposures. Obviously the worst exposures create the most severe disease, but even low dose exposures can cause real damage.

CURWOOD: Now, Dr. Landrigan, we're talking to you about the book that you've written with your wife, Mary Landrigan, which is about children and environmental toxins-- and the subtitle is What Everyone Needs to Know. So it's a handbook, there are a lot of suggestions and comments and such here; we don't have time of course to go over all of them here. But let me ask you some basic questions. Let's start with, how can people protect themselves at home from dangerous chemicals?

LANDRIGAN: I think the very first thing that people have to do to protect their children against toxic chemicals is they have to take a little time to educate themselves, just as you educate yourself before you buy a new car, you buy a new house and you learn the basic operating systems-- you have to read just a little bit about lead, about pesticides, about air pollution, about the other toxic chemicals that can affect your child. And then when a parent is armed with that knowledge they are empowered to protect their children against toxic chemicals. So how can a mom or dad protect their child against toxic chemicals in the home. Start with the big ones: lead paint in older homes, built before 1977, is still a big problem in America. There are still millions of homes that have lead paint, and so a parent needs to follow the directions we give in the book to understand if there's lead paint, and if they find lead paint in a place accessible to a child they have to bring in somebody who knows what they're doing to remove or at least cover up that lead paint.

Severe air pollution in Anyang, China. (Photo: V.T. Polywoda, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The worst thing a parent can do is to try to remove it themselves because that creates a very toxic dust, a lead contaminated dust which can cause severe poisoning. Another thing that parents can do in their home is minimize the amount of pesticides that come into the home. One thing they can do is buy organic. Now I know full well that organic produce costs more than regular produce, but the gap is narrowing; organic is getting cheaper than it used to be. If you shop wisely you can get organic for very little more than conventional. And the gain that results from eating organic is that families who do so have ninety percent less pesticides in their body. And then one last thing that parents can do in their homes is not immediately reach for the can of insecticide or the canister of insecticide that they put on the front lawn. You can control cockroaches and other vermin in the home if you do what's called Integrated past management, which is an approach that minimizes chemicals and relies on cleaning up food and other debris that cockroaches feed on. And when it comes to your front lawn, I always say to people, learn to live with a few dandelions. They're quite beautiful and in fact in the springtime you can make a salad out of them.

Eating organic produce can reduce the amount of pesticides a person ingests by 90 percent. (Photo: Michael Coghlan, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Or tea, for that matter.

LANDRIGAN: Or tea, yes.

CURWOOD: In your book you talk a bit about steps to take to protect reproductive health. What are those?

LANDRIGAN: It's very important that couples who are thinking about having a baby take steps-- ideally before they become pregnant-- but in any case during the pregnancy, take steps to protect the baby in the mother's womb against toxic chemicals. So I think it's become common knowledge that mom shouldn't drink alcohol or take recreational drugs or smoke tobacco during pregnancy. Now we're advising parents to take that kind of advice, go a step further. Be very careful you don't sand down any lead paint when you're pregnant, because it will get into your body and damage your child. Eat fish-- fish are very very important for the baby's brain growth-- but eat the right fish. There are charts available, for example, from N.R.D.C., the Natural Resources Defense Council; from the Monterey Bay Aquarium and other groups which specify which are the safe kinds of fish and which are the dangerous kinds of fish. The dangerous fish have high levels of mercury, high levels of P.C.B. Pregnant mums want to avoid those. And finally avoid pesticides when you're pregnant. Any pesticide that you spray in your house on your lawn in your garden when you're pregnant is going to get into your baby, and that's not good.

Asthma is exacerbated by air pollution, smoking, and chemicals that irritate the airways. (Photo: KristyFaith, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: There seems to be an awful lot of allergy and asthma attacks among children these days. How can parents help their kids avoid those?

LANDRIGAN: Asthma has become a big problem in American children. Rates of asthma have more than tripled in American kids since the 1970s. One of the big drivers of asthma is air pollution. Children who live near highways, children who live in polluted inner city neighborhoods have substantially more asthma than kids who live in clean areas. So there are several things that parents can do. On really bad days when the air pollution outside is bad, keep the house buttoned up. Never never smoke in the home or in the hallway outside the apartment because that smoke is a powerful source of toxic chemicals that can trigger asthma in a child. If you have the freedom to choose to live in a place where the air is better, do so, although I realize in a lot of cases that's simply not possible for economic reasons, job reasons; but still it's advice we always put out there and sometimes people can act upon it.

CURWOOD: Tell me how our governments are doing in protecting children from toxins. Briefly, what are the good points and what needs improvement in your view?

In recent years there has been significant consumer pressure for companies to remove BPA (Bisphenol A), an endocrine disruptor, from plastics like water bottles. (Photo: Hteink.min, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

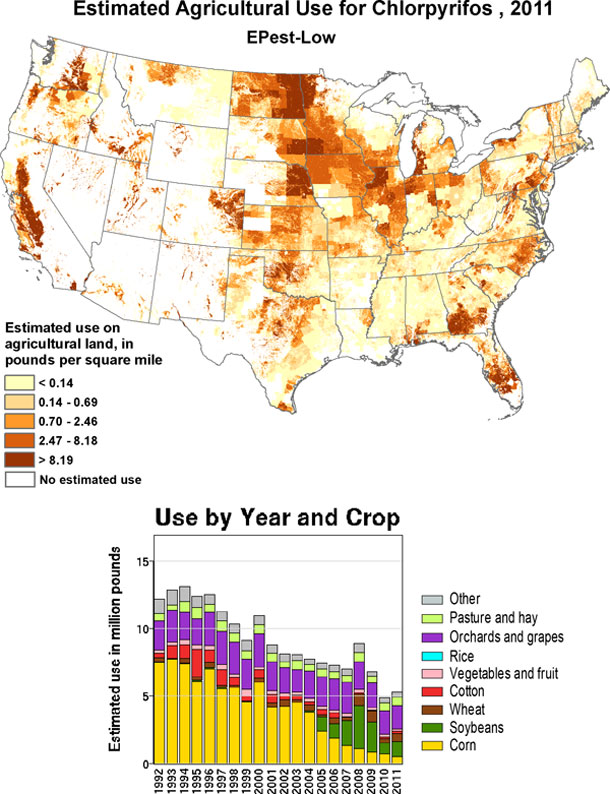

LANDRIGAN: Well over the last fifty years the US federal government has done many many very good things to protect children against toxic chemicals in the environment. One of the biggest actions they ever took was started in 1975, when they removed lead from gasoline, when EPA removed lead from gasoline. That has resulted in a more than ninety percent drop in children's blood lead levels in the United States and an average increase in children's I.Q. Across the country of more than five points. It's the reason our kids are smarter than we are because they're no longer exposed to lead from gasoline. Another really good thing that the federal government has done is clean up air pollution. Since we passed the Clean Air Act in this country in 1970, the six major air pollutants have declined by more than seventy percent. And it's interesting that during that same time that air pollution has declined by seventy percent, the gross domestic product in this country has increased by two hundred fifty percent. So anybody who tells you that cleaning up pollution is going to kill the economy doesn't know what they're talking about. So that's the good news side of the story. The bad news is that right now the federal government is moving in the wrong direction. And they're actively unraveling protections that are designed to safeguard human health. So for example the plan to scrap the Clean Air Act and to allow coal fired power plants to put more pollution into the air is going to result in more cases of asthma, more cases of pneumonia, more cases of premature birth, more stillbirths in American children. The plan to allow certain very toxic pesticides like chlorpyrifos to remain on the market -- chlorpyrifos is a chemical that causes brain damage to unborn children in the womb -- the current U.S. E.P.A. Administrator is allowing this chemical to remain on the market even though scientists within his own agency have urged him to take it off the market to protect kids against brain damage. Actions like that are not good for our kids. So I think the upshot of all that is parents who care about these issues have to act within their homes and act within their communities to protect their children. But they also have to consider getting involved more broadly -- joining the P.T.A., running for office, making their voices heard in the public space, and most of all voting. Ultimately if you want to protect your children, you got to vote and you've got to put people into office who will take action to protect your children. You can't shop your way out of it. Smart shopping helps but you can't shop your way out of dirty air, you need government to help you there.

Graph showing estimated use of the pesticide Chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxin that the EPA declined to ban last year, in the U.S. (Photo: United States Geological Survey, via Wikimedia Commons [Public Domain])

CURWOOD: So what improvements have you seen in getting some of these chemicals off the market, particularly in consumer products?

LANDRIGAN: Well in recent years, despite the recalcitrance of the federal government, we have seen positive actions in protecting children against toxic chemicals. First of all, some of the states have been very proactive -- California for example is in the process of banning various toxic chemicals. And because the market in California is so great, any action that takes place in California has ripple effects that goes across the country. We've also seen market pressure, consumer pressure, make a difference. So for example many many parents in the last two years have refused to buy baby bottles that contain phthalates, and parents have refused to buy water bottles that were made of bisphenol A. And in consequence of those actions markets have moved; manufacturers have taken phthalates, they've taken B.P.A. out of a number of consumer products.

CURWOOD: Philip Landrigan is a pediatrician and founding director of the Children's Environmental Health Program at Mt Sinai's Icahn School of Medicine. And he's co-author of Children and Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know. Dr. Landrigan, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

LANDRIGAN: Steve, it's been a pleasure, thank you.

Related links:

- Children & Environmental Toxins: What Everyone Needs to Know

- Philip Landrigan is a pediatrician and an epidemiologist

[MUSIC: Charles Mingus, “Fables Of Faubus” on Ah Um!, Not Now Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Noble Ingram, Jaime Kaiser, Hannah Loss, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Helen Palmer, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade and Jake Rego. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can find us anytime at LOE.org - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - it’s PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @LivingonEarth. I'm Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER1: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy, from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts and from Solar City, America’s solar power provider. Solar City is dedicated to revolutionizing the way energy is delivered by giving customers a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. Information at 888-997-1703. That’s 888-997-1703.

ANNOUNCER 2: This is PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth