August 17, 2018

Air Date: August 17, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Flying Insects Crash

View the page for this story

The disappearance of bees and butterflies has concerned scientists and the public for years, but a study from Germany confirms that the abundance of all flying insects has dropped over 75% since 1989. Dave Goulson, Professor of Biology at the University of Sussex in the UK, discusses the probable causes with host Steve Curwood, and says the problem is so serious, loss of insects could lead to an “ecological Armageddon.” (11:15)

Emerging Science Note: Brazilian Peppertree

/ Don LymanView the page for this story

The Brazilian Pepper Tree is considered an invasive nuisance in the American South, but Emory University researchers have isolated a compound from the tree’s berries that appears to fight the superbug MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports that the extract seems to suppress the dangerous bacterium’s ability to secrete toxins. (01:30)

Trees On the Move

View the page for this story

The big old oak in your backyard might be solidly planted in place – but its acorns can travel. And research finds that, as the planet warms, seeds of many tree species in the Eastern U.S. are heading both North and West of their historical species range. Changes in temperature and precipitation are a major cause, Professor Songlin Fei of Purdue University tells host Steve Curwood, and the shifting species ranges could change forest communities considerably. (07:20)

The Early Bird Breeds Fast

/ Kara HolsoppleView the page for this story

The early bird, they say, catches the worm. But research from the Carnegie Museum of Natural History suggests that for many migrating birds in Western Pennsylvania, the changing climate means that they are arriving and breeding earlier so they don’t miss the insects their nestlings need. And as the Allegheny Front’s Kara Holsopple reports, some birds are adapting well and thriving while others produce fewer chicks. (04:00)

Baby Tern Goes Exploring

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

On Falkner Island off the coast of Connecticut, new tern parents can raise their offspring in peace, thanks to the protection of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But as Living on Earth’s Resident Explorer Mark Seth Lender describes, one adventurous baby tern gives his anxious parents a fright as he sets out to dip his little feet into the ocean. (02:30)

The Hidden Life of Trees

View the page for this story

Forests contain much, much more than meets the eye, writes Peter Wohlleben in his groundbreaking book The Hidden Life of Trees. Within the roots of trees are active brain-like processes, and trees are capable of communication and learning. A forester himself, Peter Wohlleben tells host Steve Curwood about the unseen and unsung connections between trees, and how humans can better care for them. (14:00)

The Place Where You Live: Bear Creek, WI and St. Paul, MN

/ Regina FlanaganView the page for this story

Living on Earth gives a voice to Orion magazine’s longtime feature, The Place Where You live. This week, photographer and landscape architect Regina Flanagan celebrates the special trees that humans have chosen to keep and care for in both town and country. A single white oak in a hayfield on her family’s farm in whose shade they ate lunch inspired her childhood adventures and her photography. (05:30)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Songlin Fei, Regina Flanagan, Dave Goulson, Peter Wohlleben

REPORTERS: Kara Holsopple, Don Lyman, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Three-quarters of the insects that used to buzz around the European countryside 25 years ago have disappeared.

GOULSON: Flying insects, most insects, they make up the bulk of life on earth. They pollinate more than 80% of all the plant species, they help to keep pests under control, they recycle dung, and they’re food for the majority of other creatures...essentially take away the insects and everything else is going to collapse.

CURWOOD: Also, climate disruption is pushing trees in the Eastern US to migrate to the wetter west and milder north.

FEI: These trees have shifted close to 50 kilometers during a 30-year period. And we are seeing a big change that only nature taking its course might take several thousand years.

CURWOOD: That and more, this week on Living on Earth, Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Flying Insects Crash

The abundance of flying insects has dropped by over 75% in the past 25 years based on data from nature reserves across Germany. (Photo: Michael Mueller, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Insects can be annoying or even dangerous disease vectors of course, such as mosquitoes that spread West Nile and malaria. But scientists are calling the crash in insect populations “Ecological Armageddon,” as these six-legged creatures support key ecosystems. They feed birds, bats and frogs, and they pollinate many plants, including food crops key to human civilization. But now civilization is destroying them. The journal PLOS One reports that amateur entomologists in Germany have discovered that since 1989, some three-quarters of flying insects there have vanished from nature preserves.

Study team member Dave Goulson teaches Biology at the University of Sussex in the UK, and I asked him why this is such a perilous development.

GOULSON: So, flying insects, most insects, they make of the bulk of life on Earth. About two-thirds of all species we know are insects. They pollinate more than 80 percent of all the plant species on Earth, so if we lose the flying insects we will lose all the flowers on Earth, literally all of them. Flowers evolved to attract insects, that's why we have them. Three quarters of our crops need pollinating by flying insects. So, we’d have a world without most fruit and vegetables. They do other things too. They help to keep pests under control. They recycle dung and so on, and they're food for the majority of other creatures. So, even if you hate insects and many people do, but most people think birds are rather attractive and like to see them in the garden or whatever. Well, most birds -- at some stage of their life -- cycle eat insects. Almost all reptiles, amphibians, aquatic fish, bats, lots of small mammals, all depend on insects. So, essentially take away the insects and everything else is going to collapse.

CURWOOD: You've convinced me that we're in lot of trouble without them. Talk to me about the data that you have looked at here. What is it and how did it come together?

GOULSON: So, a group of German entomologists back in the 1980s took it upon themselves to start insect trapping our nature reserves scattered all over Germany. They used things called malaise traps which look a bit like a small tent which catch flying insects, bump into them and fall into a pot basically, and they've been doing it ever since from their own kind of interest. I got involved relatively recently, a couple of years ago, when this data kind of finally came to light and we realized what a kind of treasure trove of information it could be. And when we started looking at it we couldn't quite believe what it showed, which was just this wholesale disappearance of insects. The daily catch of insects has fallen by three-quarters, a little over three-quarters in 26 years which suggests a scale of insect decline that was just...we knew things weren't going well, we knew that butterflies are in decline and so on but there was very little other monitoring of insects going on and so we had no idea just how dramatic it had been until we saw these numbers.

CURWOOD: What do you suspect is behind this decline? As we were getting ready to talk to you, we raised the question of the neonicotinoid insecticides, which started being used in the 80s about the time this decline begins. How much of a suspect are the neonicotinoid insecticides?

Amateur entomologists used malaise traps, similar to the one above, to capture and measure the weight of flying insects in nature reserves across Germany, starting in 1989. (Photo: ap2il, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

GOULSON: I think it's very likely they are playing a role. Whether they're the main driver or not is hard to say. The broad picture I think is that essentially the way we grow food these days makes the environment completely hostile to more or less all forms of life. It isn't just neonicotinoids. We grow these huge monocultures of crops, great big fields, which typically in Europe get about 20 different pesticides applied to them, each crop cycle including maybe four or five different insecticides, whole bunch of fungicides, things to kill slugs, herbicides to control the weeds. So, there's just no scope for anything to survive there apart from the crop and if we cover the landscape in fields like that, then we probably shouldn't be surprised when we see wildlife disappearing. These neonicotinoids have got a lot of attention because they are particularly toxic to insects like bees and it takes just three billionths of a gram of one of those things to kill a honeybee and we're applying hundreds of thousands of kilos of them to the landscape every year, so it's undoubtedly contributing to it, to the loss of our insects. But they are just part of the whole system of farming which is entirely dependent on one type of pesticide or another and that's what we need to look at I think.

CURWOOD: Just another detail on neonicotinoids. I gather that they're not exactly being sprayed on the insects that are being lost, but they're in the ecosystem. How does that work?

GOULSON: So neonicotinoids are usually used as seed dressings. The farmer buys seed pre-coated with a layer of insecticide and he sows the seed in the ground and they're water-soluble. They dissolve in the damp soil and they're supposed to be sucked up by the crop plant and they spread to all of its tissues which sounds like a kind of neat system if you're a farmer. It protects the plant against insect pests. The trouble is if it's a flowering crop they go into the pollen and the nectar and then when the bee comes to pollinate the crop, something like oil seed rape, canola, sunflowers, the bee gets a dose of neurotoxin. But there's more to it than that, because it also turns out that the bulk of the insecticide doesn't get taken up by the crop at all, it's just going into the soil and accumulating in the soil, leaching into streams or being taken up by the roots of wildflowers or hedgerow plants growing near the crops.

So, we're finding these chemicals turning up in places we didn't expect them including the pollen and nectar of wildflowers. So, there was a recent study showing that 75 percent of honey samples taken from all over the world contain neonicotinoids, showing just kind of the scale, the ubiquity of these chemicals, that basically if you're a bee anywhere in the world, the chances are your food contains neurotoxins that will kill you at really tiny doses, and that surely can't be a good thing.

CURWOOD: Now, aside from the neonicotinoids, you point out that there are a whole bunch of other chemicals that might be implicated in this dramatic decline. What kind of chemicals are we talking about?

GOULSON: So, there are other insecticides. Things like pyrethroids and organophosphates. Probably the listeners out there, these things don't mean very much, but organophosphates are pretty horrible. They were actually developed in Germany in the Second World War with the aim of killing people. Most of them have been banned but there are still some that are used in farming. There are lots of fungicides. The fungicides, you think well they're not going to harm insects, but actually some of them have this strange effect... of they knock out the detoxification mechanism of the bee. So although the fungicide itself isn't poisonous…if an insect is simultaneously exposed to a fungicide and an insecticide, the insecticide is effectively much more potent. It can be up to a thousand times more toxic, and then the herbicides just get rid of the weeds so there are no flowers apart from the crop if that flowers. So, although they may or may not be poisonous to the – to the bees directly, if they get rid of their food then that's just as bad, so it's this kind of cocktail, the poor bees, you know, they're going out there, they're struggling to find food and when they do find food it's got a mixture of pesticides in it. And so, you know, we shouldn't really be surprised that bees and other flying insects aren't doing so well.

CURWOOD: So, this is data that was gathered in Germany. I've noticed in the US, for example, where I live, that I don't see lightning bugs anymore, and black flies seem to have a much shorter season in Maine and so forth, but what about the tropics? Is there a similar sort of decline there?

GOULSON: The tropics are different in many ways that there's still more natural habitat left generally not in all but in most places like the UK and Germany. Essentially everything is managed land. You have some wilderness left in the United States and in Germany in the UK we have none. It's all farmland or cities and little tiny nature reserves scattered amongst them. So, there's no reason to really believe that it wouldn't be similar in most of Europe, in the developed world, but in the tropics we don't know. Clearly there's massive habitat loss going on right now in tropical countries, that we still seeing these devastating loss of tropical forests that for all my life, we've been talking about how we really need to stop cutting down the trees. That these rainforests are teeming with life, that they're vital for regulating the climate and all sorts of other things, and yet sadly, you know, we're still hacking them down to create oil palm plantations and to grow soybean in Brazil and so on. So, my guess is insects are declining there too but I couldn't tell you whether the pace of change is the same or different.

Dave Goulson is a Professor of Biology at the University of Sussex and was part of the team investigating the precipitous insect decline. (Photo: courtesy of Dave Goulson)

CURWOOD: So E.O. Wilson, the biologist at Harvard University, famously once said and I think this is a paraphrase, that if we lost the ants, just losing the ants, we would lose humanity. What do you think this huge loss of insects means for humanity?

GOULSON: If we lose insects we're doomed, I know this sounds overly dramatic but we absolutely are. Life on Earth would be utterly changed. We wouldn't be able to grow our crops. Dung would build up in the fields. Life on Earth would essentially cease, so we absolutely have to take this really seriously, and it's something that I find enormously frustrating that we seem to live in a world where people are very detached from the environment. They don't know where their food comes from, they – they seem to not realize that actually even if you live in a city, we are part of the environment, we depend upon the health of ecosystems to provide us with places to grow our food, to provide clean air and clean water and so on. And that a healthy environment should be our number one priority. Forget the economy, forget the health service, forget the rest of it. None of those things will matter if we don't have a healthy environment because everything else will collapse, and I find it really – it drives me nuts that politicians on the whole don't often talk about the environment. It gets very little attention and we're always worried about short-term economics and so on, but actually we need to think slightly longer-term and look after the planet.

CURWOOD: Professor, what could be done to slow this trend, this rapid loss of insects?

GOULSON: I'd love to see a major rethink of how we produce food. This idea that we need these great big fields full of monocultures of crops. There are other ways of growing food. I'd love to see it move towards small-scale production, get more people back onto the land and small farms producing food for local consumption. We should really tackle food waste because we grow all this food at huge cost to the environment and then we throw away about a third of it, which is absolutely insane. We eat too much meat. If we could convince people not to eat so much beef in particular then that could massively reduce our footprint on the planet, so there are things we could do but they all require buy in from significant numbers of people, you know, one or two environmentalists like me banging on isn't going to do anything. We need the majority of people on Earth to change their ways and that's a pretty difficult thing to achieve.

CURWOOD: Entomologist Dave Goulson is a professor and biologist at the University of Sussex in the UK. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

GOULSON: My pleasure.

Related links:

- PLOS ONE: “More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas”

- The Guardian: “Warning of ‘ecological Armageddon’ after dramatic plunge in insect numbers”

CURWOOD: You can hear our program anytime on our website, or get an audio download. The address is LOE dot org. That's LOE dot O-R-G. There you’ll also find pictures and more information about our stories. And we’d like to hear from you:

You can reach us at comments @ l-o-e dot org. Once again, comments @ l-o-e dot O-R-G. Our postal address is PO Box 990007, Boston, Massachusetts, 02199. You can call our listener line, at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121.

[MUSIC The Punch Brothers, Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, Allegro, on Live From the Lower East Side: p-Bingo Night! written by Johann Sebastian Bach, Nonesuch]

CURWOOD: Coming up, why trees are on the move even though they can’t walk. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth – Stay Tuned!

CURWOOD: If you like what you hear on Living on Earth, please join us with a gift of five dollars or more. Just go to l-o-e dot O-R-G, and click donate at the top of the page. And thank you!

[MUSIC: Mulatu Astatke: “Mulatu’s Mood” from Mulatu Steps Ahead (Strut Records 2010)]

Emerging Science Note: Brazilian Peppertree

The red berries of the Brazilian Peppertree. (Photo: Javier Alejandro, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In a minute, trees that travel, but first this note on emerging science from Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

LYMAN: The Brazilian peppertree is a weedy, invasive species native to South America. Although considered a nuisance in Florida, where it grows in dense thickets and crowds out native plants, scientists at Emory University say traditional healers in the Amazon have treated wounds and skin infections with its bark and berries for hundreds of years.

Now, the Emory researchers have isolated a compound from the berries that appears to prevent skin lesions in mice infected with MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium that can cause serious infections, and is resistant to penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotics.

The scientists say that the compound doesn’t kill the bacteria, but represses a gene that allows them to communicate. This essentially disarms the MRSA bacteria and prevents them from excreting toxins that damage tissues.

Antibiotic-resistant infections are a widespread and growing problem that cause about two million illnesses and 23,000 deaths in the United States each year. The researchers say the Brazilian pepper tree extract could not only provide new ways to treat and prevent these infections, but do so without boosting the bacteria’s ability to resist our antibiotics. That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- Press release: “Brazilian peppertree packs power to knock out antibiotic resistance”

- Nature article in Scientific Reports: “Virulence Inhibitors from Brazilian Peppertree Block Quorum Sensing and Abate Dermonecrosis in Skin Infection Models”

- National Invasive Species Information Center: The Brazilian Peppertree

[MUSIC: Lord of The Rings, The Complete Recordings “March of the Ents” Howard Shore https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42uhK1k47eg]

Trees On the Move

White pine forest in Pennsylvania. Conifer species including the white pine, Pinus strobus, tend to be moving north as the Eastern U.S. warms. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Yes, we have another tale of trees, trees that are moving, though not as dramatically as the Ents in the Lord of the Rings epic. Now trees can’t walk, but their seeds can fly and some species are migrating. A recent study confirms that 86 tree species of the Eastern US are moving as the planet warms. But not just North. Some are heading West. Songlin Fei of Purdue University is the lead author of the study and came on the line. Professor Fei, welcome to Living on Earth!

FEI: Well, thank you, it’s very nice to be here.

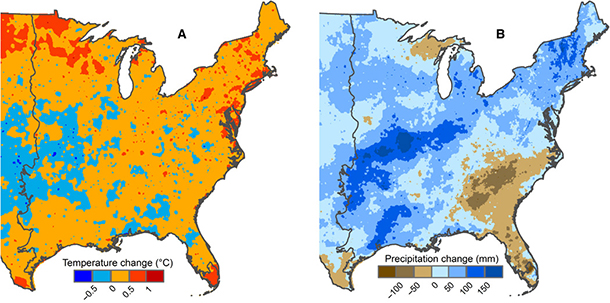

CURWOOD: So, tell me what's going on here? The Northward shift is not so surprising, since that's mostly having to do with temperature and climate change certainly is warming things up, but why are trees also moving West?

FEI: Well, this is a very fascinating phenomenon. When we first looked at it, we have the exact same question that you do: Why the trees are moving westward? So, for climate change it means two things, often we think about temperatures warming up.

A Pennsylvania forest dominated by mixed broad-leafed trees. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Right.

FEI: But on the other aspect is that climate change is also causing precipitation pattern changes. In our study area in the Southeastern US like in Georgia, in the Carolinas and part of Florida even, they have a significant drought. On the other hand in the Western portion of the study area -- primarily we’re talking about the midwestern areas such as Missouri, Illinois. Rhey have more water or precipitation overall compared to historically what they have. So, the main driving factor that we are seeing that trees move Westward is due to the responding to the changing of moisture availability.

CURWOOD: So, the way that the trees move, of course, is that trees don't pick up and walk on their roots. Their seeds go in one direction or another, and the saplings have more success then in a particular direction or another.

FEI: Yes, so we are not only talking about addition of the new seedlings, but we are also talking about mortality that is happening for the big trees, especially given the drought that we have in the Southeast. And so, you think about this as an example, say, a line of people lining from Indianapolis to Atlanta. Every individual in that line has not moved in a single inch, but there are more people joining the line, say in Indianapolis or in Lexington, and there are people dropping out of the line in Atlanta, and then what's going to happen is the center of this line seems like, shifted.

CURWOOD: What kinds of trees are experiencing these shifts?

This figure from Songlin Fei’s paper shows changes in temperature, left, and precipitation, right, across the eastern United States, between the recent past (1951–1980) and the study period (1981–2014).

(Photo: Songlin Fei)

FEI: Well, so if we look at the groups that belong to certain families, what we find is that trees, which are those flowering plants, broad-leafed plants, they are moving westward. So those are the oaks, maples, or the hickory species. But if you're looking at the specifically evergreen tree group which are the pines and spruce and firs, majority of these evergreen trees are moving northward.

CURWOOD: So, what's the difference then, between the pines and plants like them versus the broadleaf trees like the oaks and maples that causes this difference in movement? I gather one is more sensitive to water and moisture. Which one would that be?

FEI: Well, so in our analysis, we followed up by looking at the traits of the individual species. We looked at over a dozen of traits, and for those westward moving trees in general they are more tolerant to drought. They also have some unique ability in terms of the seeds.

CURWOOD: So, why did the broadleaf trees, the oaks and the maples, if they have more drought tolerance, why are they moving west? It seems that there is more water to the west?

FEI: OK, well so we need to put into context even though we say there is more drought in southeast and getting wetter in the midwest, in reality Georgia and Florida they still get way more precipitation than in say, Missouri or Illinois. But compared to the historic average, you started getting more moisture and these other trees are able to take the advantages of more moisture availability in a relatively dry area.

Forests in the Eastern U.S. are typically made up of diverse tree species, including both evergreen and deciduous trees. But the unnaturally rapid pace of tree species heading north and west could fragment these unique communities. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, in other words, they can pioneer to places that were previously too dry for them, but now with just a little more moisture, they can go there. So, to what extent have tree species shifted their range in the past?

FEI: Trees are shifting its range all the time because of glaciation, or retreat of the glacier, and so there are studies in the New England area looking at how trees are tracing the changing temperature in the precipitation in the last several thousand years. But the differences among our study and what we're seeing is that we are talking about a 30-year period, that we track trees shift between 1980 to 2015, and we are seeing a big change that if only nature taking its course might take several thousand years that is happening.

CURWOOD: And how far over these three decades do these trees move? How far can they go?

FEI: So, on average, these trees have shifted about 15 kilometers per decade, so it's roughly about 10 miles per decade, close to 50 kilometers during the study period.

CURWOOD: Songlin, if the maples, if the oaks, if the hickory are moving to the west, and yet the pines and the spruce and the firs and moving to the north, this will change the whole ecological balance in a forest system. How are forest ecosystems coping with this divergent change?

Songlin Fei is an Associate Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. (Photo: Purdue University)

FEI: Yes, this is really a great question, and we don't really know yet because the current study we are looking at individual trees, but when we look at a forest this is really a composition of multiple species, which in ecological terms we call a community. And so, we don't know whether the community is currently vulnerable for break down because of the different direction of this shift by individual species. So, we are interesting in looking at how these communities are responding as a group. Are there certain community groups that are more vulnerable than the others? And so, this is really what we are interested to look at next.

CURWOOD: Songlin Fei is an Associate Professor in the Department of Forestry and Natural Resources at Purdue University. Thanks, Professor, for taking the time with us.

FEI: Well, thank you, it's nice to be on the program.

Related links:

- Science Magazine: ScienceAdvances: “Divergence of species responses to climate change”

- Nature: “Trees in eastern US head west as climate changes”

- About Songlin Fei’s research

[MUSIC: Lord of The Rings. The Complete Recordings “March of the Ents” Howard Shore https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=42uhK1k47eg]

The Early Bird Breeds Fast

Avian research coordinator, Luke Degroote, examines a Northern Flicker at the Powdermill Nature Reserve. The Flicker and other local birds have been breeding earlier in the year and producing fewer chicks.

(Photo: The Allegheny Front)

CURWOOD: Our disrupted climate is affecting many species, and migrating birds are especially sensitive. As the time of spring shifts birds may get out of step with the food sources they rely on to nest and raise their chicks. The Allegheny Front’s Kara Holsopple reports.

HOLSOPPLE: Luke DeGroote is the avian research coordinator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. And he runs the bird-banding program at their Powdermill Nature Reserve in Westmoreland County. Right now he’s in the thick of spring migration.

DEGROOTE: It’s sort of a bit like fishing, in a way. We put our nets to see what we catch.

HOLSOPPLE: From early in the morning, until about noon, he and a handful of volunteers patrol a series of nets -- kind of like volleyball nets -- that are set up around the property.

DEGROOTE: This is a red-winged blackbird ... I’m going to grab him by the body, and very carefully pull the netting off the tip of the wing.

HOLSOPPLE: Birds like this little guy, with the distinctive red patch on its wing, get caught up in the fine netting, and drop down into a pocket where they’re scooped up by researchers.

DEGROOTE: The red-winged blackbirds tend to hold on tight.

HOLSOPPLE: He’s really clinging on. When it’s finally freed, DeGroote gingerly places the bird into a bag, like a small pillow case, and loops its string to a red carabiner around his neck … Red indicates which size metal band to place on the blackbird’s leg so it can be tracked.

DEGROOTE: I’m heading to three -- if anyone wants to check the edge of the ponds that’d be great.

[BLEEPING SOUND]

Mammoth Lake in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. Birds here have been breeding sooner in the spring in order to keep pace with earlier warmer temperatures. (Photo: Jon Dawson, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

HOLSOPPLE: All the birds they capture this morning -- and every morning -- are taken back to a small lab where they’re banded with a unique number and weighed. Researchers also examine their feathers to determine age, and if the birds are getting ready to breed.

DEGROOTE: The females -- when they’re in breeding condition -- will lose the feathers on the breast and then insert some fluid to create really, like, a hot water bottle for the eggs.

HOLSOPPLE: They’ve been collecting these data here at Powdermill, consistently, for over 50 years. That’s how they know -- from previous studies -- that birds are migrating here a little earlier in the spring than they used to, and breeding sooner. And that got DeGroote and his research partner Molly McDermott thinking.

DEGROOTE: All right, if they're migrating early and breeding early, are they breeding earlier because they're migrating early or are they breeding more quickly after they arrive?

HOLSOPPLE: So what did you find?

DEGROOTE: YEAH, they're basically getting busier earlier after arrival.

HOLSOPPLE: That’s true for the majority of the 17 common bird species they studied. In their recent paper, published in the journal Plos One, they connect early breeding to warmer springs and climate change. Because while birds are arriving here day earlier for every one degree Celsius that the temperature has warmed over the last few decades, spring buds are opening three days earlier. Those plants and the insects birds rely on for food, for the survival of their young, are now sort of mismatched with the timing of spring migration. So these birds are responding the only way they can.

DEGROOTE: They're having to catch up because they're not able to catch up during migration -- they're not able to sort of advance that as much as the plants -- they have to begin breeding soon after arrival if they want to breed at a time period that's sort of what they're used to.

A meadow blooms in Lehigh, PA. Researcher Luke Degroote says while birds arrive a day earlier for every one degree Celsius the temperature has warmed over recent decades, spring buds are opening three days earlier. (Photo: Nicholas A. Tonelli, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

HOLSOPPLE: When the tender plants and insects they eat are at their peak. A quarter of the species which bred earlier in this study -- like black-capped chickadees -- had more babies in these warmer years. But another 25 percent -- including hooded warblers -- didn’t. Their productivity declined.

DeGroote says you can look at the results of this study two ways. On the glass-half-full side, it shows some bird species are flexible, and capable of adapting to climate change. But while weather isn’t climate -- a few years ago there was a hard winter and later spring, this year is warmer -- he says the overall trend for birds is worrying.

DEGROOTE: If it continues to warm that window which they have to be adaptable is shrinking.

HOLSOPPLE: This most recent study just looks at the timing of bird breeding, but DeGroote says it’s easy to see the implications for the ecosystem. If some species are less successful because of climate change, there might be fewer birds to pick off insects or spread seeds from the fruits they eat. I’m Kara Holsopple.

CURWOOD: Kara Holsopple reports for the Pensylvania public radio program, The Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Allegheny Front story

- Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Powdermill Nature Reserve

[MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “Fire and Rain” on Afro-Classic, composed by James Taylor, CTI Records]

Baby Tern Goes Exploring

A fluffy tern chick goes exploring at the water’s edge. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: We head to the seashore now with our explorer in residence, Mark Seth Lender. Falkner Island off the Connecticut shore is only four and a half acres in size, but has one of largest roseate and common tern colonies in the East. Officials go to great lengths to protect the terns, by keeping people, pets, and predators away, but Mark got permission to visit with his camera. And there he saw the anxieties of parenting that can be common to many species.

Baby Has New Shoes

Common Tern, Falkner Island © 2016 Mark Seth Lender All Rights Reserved

A flustered tern parent appears to chide its offspring. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

LENDER: Like baby in his baby shoes, Tern is going for a walk. The way some kids do without holding onto a hand, without looking back.

But there are no shoes! His little feet are webbed like his Mom and Pops (bright orange-red and not quite steady as he walks). He is heading out all by himself. And does not pause and will not stop. The stubs that will be wings wheel and shy like little arms. He hops, over the flotsam of green seaweed. He drops, into the jangle of dried reeds, and crosses the tideline.

Tern egg among dried seaweed and stones. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

All dandelion fluff round as a puffball soft as fleece, small enough to fit in the pocket of your blouse -- there he goes! Along the reach of rustling pebbles and slipper shells, off to dip his new toes in the little waves that wash up on the beach.

Meanwhile, Mom and Pops don’t like any of this. They leave the nest and close upon his unsteady heels, flapping and whistling and calling him back, “Wait up, kid, you’re gonna hurt yourself! You’re not ship-shape, your tail’s out of trim. You can’t get out if you fall in!”

Mom lands on a rock that towers over him.

Pop cries out from the shore: “Whatcha thinkya doin out there!”

Threats and entreaties Kid Tern ignores as he touches, and tastes, where the ocean gently roars. We’ve all been there. That time of life. We knew better than anyone; anyone put there to tell us no. Our yes was so much stronger than that. We were sure, we had no fear.

[SOUNDS OF TERNS CALLING]

An adult tern flies off with a fish. (Photo: Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Mark Seth Lender recorded these terns at Falkner Island, and for pictures, wing on over to our website, LOE.org.

[SOUNDS OF TERNS CALLING]

Related links:

- To learn more about Falkner Island and the work of the USFWS, visit Mark’s website

- USFWS Stewart B. McKinney Wildlife Reserve

[MUSIC: Hubert Laws, “Moonlight Sonata” on My Time Will Come, composed by Beethoven/arr.Laws, MusicMasters Jazz]

CURWOOD: Coming up, why some scientists say trees have societies and can feel pain. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth, stay tuned.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[MUSIC: John Barry and His Orchestra, “Theme From Goldfinger,” live at the Royal Albert Hall, Bricusse/Newley/Barry, also available on EMI Records]

The Hidden Life of Trees

A 4,000-year-old beech forest in Peter Wohlleben’s forest district in Hümmel. (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. According to Greek mythology, the trees in a certain grove could talk, with the gift of prophecy. And there are many other fables of talking trees, from the Disney film about Pocahontas to the Lord of the Rings. Well now a German forester says trees can talk -- at least to each other. Peter Wohlleben also believes forests are social networks where individual trees not only communicate with each other and warn each other of impending dangers, they also care for their sick and elderly and live shorter lives if they can’t connect with each other.

Peter Wohlleben’s book is called The Hidden Life of Trees and he joins me from Germany. Welcome to Living on Earth!

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, hi. Hello.

CURWOOD: Now, where is your forest there in Germany?

WOHLLEBEN: My forest is in the western parts of Germany just a little distance to the Belgian border in the Eifel Mountains. We have beautiful forests there.

The old moss-covered stump, which Peter Wohlleben first thought was a stone (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

CURWOOD: So, I want to warn our listeners to strap on their seat belts because we're going to go to some heights of thinking about trees that people usually don't go. We'll talk about trees maybe having brains, having societies, having some sort of a memory. Peter, you began your book with the chapter called, “Friendships” that describes how you stumbled upon a rather remarkable set of mossy green, might I say, stones? What did those stones turn out to be?

WOHLLEBEN: They turned out to be a century-old stump. The tree I think was felled 500 or 400 years ago, and when I stumbled upon it and researched it, I found out that it was still living without any green leaf, and that seemed to be impossible because a tree is a living being which burns sugar in its cells, like we do. And after 400 years every molecule of sugar should have been gone, and the only explanation was that this old stump was supported by its neighbors.

CURWOOD: Supported by its neighbors? Why do some trees feed a nearby stump?

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, that sounds incredible because we all learned in school that within evolution each being is struggling against each other so that just the fittest survive, but in the forest we have a social society which fights for each other, so the whole forest will survive. Every tree is interested to keep its neighbors because together they create a special climate, which is cool, which is humid, and where every tree feels comfortable.

CURWOOD: By the way, what kind of tree was this stump?

Tree roots are believed to contain a great deal of a tree’s accumulated ‘knowledge’ (Photo: Tim Green, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WOHLLEBEN: The stump is an old Beech tree. Beeches were common to all Germany, to all Central Europe into the eastern part of the United States and to some parts of Canada. Nowadays we have most of those areas changed into plantations of Spruce and Pine and so on.

CURWOOD: So, if this stump was some 400 years old, how old were the trees that were taking care of it?

WOHLLEBEN: We don't know because these trees weren't planted, so just can guess how they are. I think they are about 200 years old. We don't have any very old trees in Germany because each tree, when it gets a certain age, will be felled. So, the timber industry, that's a very sad chapter, and without very old forests you can't detect what's going on.

By necessity, the roots must be cut when the tree is planted; but this practice, among other factors, shortens the life of urban trees. (Photo: DeepRoot, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: In your book you imply that there must be some relationship between that stump and the trees that are feeding it. Maybe family?

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, that's really possible. Susan Simard from the University of British Columbia found out that, for example, mother trees are able to detect their childs from other young trees, and that they are also have favorite childs which they feed more than other childs, which sounds incredible and perhaps even not so nice, but that's something which even trees have, yeah.

CURWOOD: What do you think the odds are that the trees around it were daughters or sons of this mother or father, that they were taking care of their parent?

WOHLLEBEN: That's possible because trees, they have in their root tips, brain-like structures. The University of Bonn found that brain-like processes are going on so that the trees can manage to find out, is it a neighbor, is it a different species, are that are my own roots or is a beloved child or grandfather or whatsoever?

CURWOOD: OK, wait a second. You're talking about brains in trees. How could a tree have a brain?

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, that's really something special because it's not a brain like we have, and that makes it a little bit complicated to understand because we really don't know exactly where the brain of the tree is. We know that the root tips have brain-like structures, but that doesn't mean that the brain is there. We don't know where a tree stores its memories, for example. Some memories are stored in the branches. We know that, for example, in spring trees can count the days above 20-degrees Celsius because when it's getting warm in March that doesn't mean that the spring is really there. There may be some days after, for example, in April where deep frosts can destroy the new leaves, so the trees have to wait until the spring is really there, and therefore they count the days, the warm days and just when a certain amount is counted, then the new leaves appear, and that means that a tree do not just count but also has a memory. Trees can also remember, for example, heavy droughts.

A branch from a little beech tree. Each knot on the bark represents one year of growth and shows how slowly the young tree is growing. (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

In the year 2003, we had in Germany a very heavy drought during the summertime, and trees, which were not used to dry summers, they suffered very hard. The wood cracked, and that hurt them, and afterwards those trees changed their strategy of water consumption. They know that they don't have to use too much water in spring because they had to save some water for the next maybe dry summer. So, a tree can remember what has been going on in the past and after that change its strategies to a new way of water consumption, and that was something very surprising.

CURWOOD: So you're saying that trees are capable of learning, and you wrote that in your book. What do you mean?

Beech seedlings (Photo: Mark Robinson, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, trees are also able to learn from other trees. For example, this case of this heavy drought. It concerns at first trees, which are standing on dry earth. They are the first ones to suffer from a drought, and, when they recognize that the water is running out, then they give information to other trees through their roots and through a family network and those other trees learn that there is something going on with a drought or with an insect attack, and then they can prepare and reduce their water consumption, or, when an insect attack is going on, they may bring poison into their bark and they store this memory, and the next situation like this they may react much faster.

CURWOOD: How do trees communicate? How fast does that communication go?

WOHLLEBEN: Trees are very slow. For example, electrical signals in their tissue needs perhaps one or two second per inch. Therefore, they may react within minutes or hours or even days. Because this electrical signal will use maybe several minutes from the upper tree down to the roots, there's a second way to communicate with chemical signals, which are sent out from the leaves, and the trees around may smell it, and therefore smell, “Ah, this is a special beetle which is attacking the neighbor tree.” And they may prepare much faster than being informed through the roots.

CURWOOD: So electrical impulses travel through the trees very slowly, but rather the way nerves transmit things, and they can warn each other of danger. Peter, why is it useful for forest managers to understand trees as social beings?

WOHLLEBEN: Because healthier forests will also produce more timber. But for me the main thing is foresters should be treekeepers, and the first aim should be to keep a healthy forest for the next generations. The forest is much more than timber, for example, this old Beech forest which I'm responsible for contains more than 10,000 animal species, and when you clear-cut it and replace it, for example, with a Douglas Fir or a Spruce, then most of those species will be run out and replaced by species which are not common to our region.

Even selective logging (as opposed to clear cutting) harms forests, according to Wohlleben. (Photo: barnimages.com, Flickr public domain)

CURWOOD: Peter, what is lost when old growth is cut? How does that change the behavior in the social network of trees?

WOHLLEBEN: Even when you make a thinning and just cutting one of the other trees and leave, for example, 50-percent of the trees untouched, this social network is destroyed. When you do it like this, you make a tree changing from a social being to single. Those trees suffer. They don't get very old. For example, a Beech may grow as old as 400 years and when you make a thinning in such a forest, this Beech will die at around 200 years, nearly half the age which is natural.

CURWOOD: Peter, how are urban trees very different from the trees that have grown up in a forest?

WOHLLEBEN: Urban trees are a special thing. Urban trees are like street kids without parents. They can grow as they want to grow, and in a metro forest, in a primeval forest, those old mother trees didn’t rely down to three percent, so the little ones may produce just as much sugar that they don't die, but not more. They are not allowed to grow in the first 200 or 300 years. In the street, they get from the first day on light as much as they want. They can grow, they can produce sugar as much as they want and they grow in a very unhealthy way, very, very fast. That's what we want to have in our streets. We want to have, in a short time, big trees because they look so nice, but those trees can’t become very old. They will die earlier.

There is another problem. When you let the street light burn the whole night, then trees can't sleep, and they will die earlier that trees which may sleep at night without any light.

CURWOOD: So, in Boston, where we have our studios, up and down the streets there are not a lot of very old trees even through the streets are very old. What would've happened to those trees to prevent them from getting to be old? After all, they're protected in the city. No one is likely to cut them down, unless there's a storm or something.

A 200-year-old mother beech tree with its 150-year-old child (Photo: Peter Wohlleben)

WOHLLEBEN: Yeah, but they are without their social network. Those trees are all singles. They are all on their own like Robinson Crusoe on an island. We think we have, for example, in the street a row of trees which should be connected but in reality the distances are too far. The roots are destroyed. The root tips, they have been cut, because otherwise the roots were too big to plant. And with those cutted roots, the trees are not able to connect anymore.

CURWOOD: When did you realize that individual trees can communicate with each other, care for their sick, warn each other of impending dangers?

WOHLLEBEN: I think, the first time, I knew about trees as much as a butcher about animal feelings. But afterwards, to rescue the old Beech forest, we made part of them into a burial ground. People may buy an old Beech tree instead of a gravestone and be buried in form of an urn, and together with those people I learned to look new at trees. As a forester, you see a tree and every tree planks or you see paper or whatsoever. Then, when I began to look more and more, I discovered more which makes it nowadays a little heavy to cut any trees which I have to do.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] I imagine. Peter, how are people reacting to your research?

WOHLLEBEN: Most people are reacting friendly because I just write things which they always thought might be true, but really, bad critics are coming from foresters, and think, I believe it's because I disturb their jobs, their profits, because when people register the trees have feelings then we can't treat them like we do nowadays, with cheap methods, for example, by harvesting those trees with big machines, destroying with those heavy machines the storage possibilities of the soil by compressing the soil and so that no water may be stored from the Winter. So it's true that most bad critics are coming from colleagues from me, and applause is coming from, let's say, normal people which always thought there has to be more than just timber within trees.

CURWOOD: Overall, how well are we doing managing the forests on our planet here on Earth?

Peter Wohlleben is the author of Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate – Discoveries from a Secret World (Photo: Tobias Wohlleben)

WOHLLEBEN: I think we are treating them very bad in the moment. For example, those clear-cuts are not just destroying those social systems, but also the factories for wood. When you cut a forest complete down, you have nothing to produce timber. We have changed here in this little village where I'm living, the forest methods, and afterwards we have created more jobs, we have earned much more money, and the forest is healthier. So, we have ways to use timber without disturbing the forest too much. Trees, which can get very old store carbon at the same time, that's clear. But in the moment, all I see is the fast profits. There's no thoughts about the future and the next generations.

CURWOOD: Peter Wohlleben is a forester and author who cares for an environmentally friendly woodland for the village of Hummel in Germany. His new book is called, "The Hidden Life of Trees." Thank you so much.

WOHLLEBEN: Thank you very much.

Related links:

- Peter Wohlleben’s website

- About Peter Wohlleben’s work as a forester in Hümmel, Germany

- The Hidden Life of Trees book

- The Ancient Beech Forests of Germany comprise a UNESCO World Natural Heritage site

[MUSIC: Giovanni De Chiaro, “The Weeping Willow” on Scott Joplin on Guitar, Scott Joplin, Centaur Records]

The Place Where You Live: Bear Creek, WI and St. Paul, MN

Regina Flanagan took the photo of the Lunch Tree that inspired her essay in August 2005, at her family’s dairy farm in Bear Creek, Wisconsin. (Photo: Regina Flanagan)

CURWOOD: We take a trip now to St Paul, Minnesota and Bear Creek, Wisconsin, for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth / Orion Magazine series, “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to put their homes on the map and submit essays to the magazine’s website and we give them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes (Rough Trade Records 2009)]

CURWOOD: A single white oak in a field near a childhood home is the inspiration for today’s essay.

FLANAGAN: I’m Regina Flanagan, and this is my essay entitled, “Lunch Tree.”

Nature is a frequent subject of Regina’s photography. She took this photo of a riverbed and tree roots at the Embarrass River in Haymans Falls County Park, Wisconsin. (Photo: Regina Flanagan)

I learned much later, after my brothers had taken over the family dairy farm, that my dad called the solitary white oak in the middle of the field near the creek “The Lunch Tree.”

[MUSIC: “Unfamiliar Wind,” Brian Eno, Ambient 4, EG Records 1982]

Before I became a teenager and felt confined by the isolation of the farm

[COWS LOWING]

and thought that somehow it was keeping me from participating in the wide world outside, this landscape was my world, as it was for my dad. While I played in the hedgerows between the fields, discovering remnant patches of wildflowers, and ventured down the lane next to the woods until that exciting moment when our house was out of sight. My dad was sowing crops for the cows, corn or alfalfa hay in the broad fields.

Long before my dad farmed the land, someone had chosen to retain that solitary oak tree.

[INSECTS BUZZING]

It became the place where, at high noon in its shade, Dad would take a break from work, and we would eat our sandwiches and sip water from a red and white insulated cooler jug.

Kids explore the Red River near Gresham, Wisconsin in this August 2013 photo by Regina. (Photo: Regina Flanagan)

Now I live in a city where I find stimulation, and where I work as an artist in a neighborhood that is leafy and green and more wooded than the place where I grew up. When my siblings, nieces, and nephews from the farm visit, they are amazed by all the trees. Such diversity! Lining my street are maples, swamp white oaks, river birches, hackberries, and even a few elms. Neighbors up and down our block chip in to inoculate them against Dutch elm disease every few years, to retain their majestic canopy.

The trees along my street are here because humans decided to plant and care for them. The Lunch Tree was retained by a settler, clearing land for farming over one hundred years ago. They are all chosen trees. They endure because of human choice and care.

A 2006 photo by Regina, taken in a red oak grove near Bear Creek, Wisconsin, echoes the exploring she used to do there as a young girl growing up in the 1950s and 60s. (Photo: Regina Flanagan)

[MUSIC: “A Clearing,” Brian Eno, Ambient 4, EG Records 1982]

So, the next time you notice a solitary tree in the countryside, in an open field or along the road, you’re seeing not only a survivor of the original landscape, but the expression of a choice made long ago by people like my dad, who felt a deep affection for that place.

[MUSIC AND FARM ANIMAL SOUNDS]

The farm remains a working dairy farm in my family to this day, outside the village of Bear Creek, which is west and south of Green Bay. I’m a landscape architect and photographer, and I presently live in St. Paul, Minnesota. My essay is about one of my photographs, an image of a white oak, standing alone in a field of shorn alfalfa on a clear, cloudless morning. My brothers’ barns and silos are visible in the distance.

My photography is kind of the thread that connects all the pieces of my life. There are stories that a photograph can tell, but there’s also things that are not visible in the photograph and that are really about its history. The oak tree is actually a remnant of a landscape that only exists in small pieces still on the farm. That includes a small woodlot that was never logged, also an area near the creek which is where I played as a child.

Regina Flanagan is a photographer and landscape architect who lives in St. Paul, Minnesota. (Photo: courtesy of Regina Flanagan)

In the late 1950s and early 1960s we were sent outdoors to play, and we were often out all day. Sometimes my mom would pack me a hobo lunch, and I’d take off to have an adventure.

[INSECTS BUZZING, MUSIC, WATER SOUNDS]

My favorite destination was the creek down the lane, which is a cow path, really, that connected the farm fields. It was bounded by the woods on one side and on the other side by a barbed wire fence and then the fields where the cows were pastured. The woods were magical. I’d pore over the plants on the ground and the details of the leaves, their forms and shapes and occasional flowers, and I’d often wonder about the plants. What were their names and how they got there. They were the landmarks, especially the oak trees.

The sensations are still very vivid. The changes of light and shadow, the tangy smell of decaying plants in the wet meadow, and especially the trill of redwing blackbirds.

[RED-WINGED BACKBIRD SONG]

[MUSIC: “Home,” (orig. performed by Philip Philipps) [Piano Karaoke Version], arr. Sing2Piano 2012]

CURWOOD: That’s Regina Flanagan, and the Lunch Tree. There are pictures at our website, loe dot org – and there you’ll also find details about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay, if you want to tell us about the place where you live.

[MUSIC: “Home,” (orig. performed by Philip Philipps) [Piano Karaoke Version], arr. Sing2Piano 2012]

Related links:

- See more of Regina Flanagan’s photography

- Find more The Place Where You Live essays featured on Orion Magazine’s website

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Anna Gibbs, Don Lyman, Maggie O’Brien, Aynsley O’Neill, Sarah Rappaport, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, on iTunes or Google Play music and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood, thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth