August 24, 2018

Air Date: August 24, 2018

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Thousands of Lead-Poisoned Communities

View the page for this story

Flint, Michigan became a flashpoint for excess blood lead levels in children, putting their brains and social development at risk. Now a data based investigation by Reuters reporters Michael Pell and Joshua Schneyer has found over 3,800 neighborhoods around the country with children with blood levels of the toxic metal double those in Flint. Michael Pell tells host Steve Curwood where and for whom the risk is greatest. (13:52)

Science Note: The Power of Dust

/ Noble IngramView the page for this story

In the Sierra Nevada mountains, heavy runoff and erosion can steal precious soil nutrients from the ecosystem. New research shows replacements come from an unlikely source: dust flying in from far away, as Noble Ingram explains on this week’s Note on Emerging Science. (01:41)

Obesity and House Dust

View the page for this story

Hormones tell our bodies whether or not to create fat cells, and hormone disrupting chemicals can confuse those messages. Such chemicals are found in pesticides, flame retardants, and plastics. They also turn up in house dust, and research from Duke University found that typical amounts of household dust spurred the growth of mouse fat cells in a lab dish. Study author Chris Kassotis and host Steve Curwood talked about the implications for human health, and children’s development, given America’s obesity epidemic and how we might stay healthy in our own homes. (06:56)

Bitcoin, The Energy Hog

View the page for this story

With a net value estimated at some 250 billion dollars, Bitcoin has become the world’s premier virtual currency. But though it exists only online, it runs up huge energy costs in the real world. Data consultant Alex de Vries explains that verifying Bitcoin transactions is so energy intensive, the currency tops 159 individual countries in energy consumption. De Vries and Host Steve Curwood explore Bitcoin’s climate costs. (07:21)

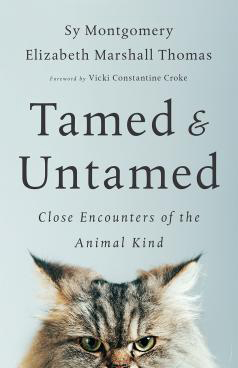

Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind

View the page for this story

The science of animal psychology is still developing and what exactly your family dogs, or wild rabbits are thinking is a fascinating topic for two committed animal observers, Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas. These best-selling writers believe these and all creatures, wild or domesticated, deserve respect. Their collaborative book of essays, Tamed and Untamed, dives into the curious mental and emotional space among creatures and humans, as they explained to Host Steve Curwood, when he visited Sy Montgomery’s New Hampshire farmhouse. (16:43)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Chris Kassotis, Sy Montgomery, Michael Pell, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, Alex de Vries

REPORTERS: Noble Ingram

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRI, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I'm Steve Curwood.

Lead is one of the most dangerous and destructive elements for brain development and kids in nearly 4000 US communities have troubling levels.

PELL: So what we found was that Flint was not the only community that was suffering from this problem but there were hundreds of communities across the country that are suffering with childhood lead exposure. And we found that those county-wide maps not only didn't really show the problem areas, but they actually could provide a false sense of security.

CURWOOD: Also, logic and love aren’t exclusive to humans, says writer and naturalist Sy Montgomery.

MONTGOMERY: The idea that animals don't think is insane. A much worse mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

CURWOOD: Close encounters of the animal kind. That and more this week on Living on Earth, Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Thousands of Lead-Poisoned Communities

St. Joseph, Missouri, has neighborhoods filled with aged homes and high rates of lead poisoning. Here, Kadin Mignery, 2, plays on his front porch. Kadin was diagnosed with lead poisoning, prompting his mother to change his diet and repaint the home’s interior. (Photo: courtesy of REUTERS/Whitney Curtis)

CURWOOD: From PRI, and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The youth of Flint Michigan have become poster children for lead poisoning after the scandal that began back in 2014, but Flint is hardly unusual. We now know there are close to 4000 other places in America where children have blood lead levels more than double those found in Flint, according to an investigation by Reuters. And the public health risk is not just from lead pipes and contaminated water, as in Flint, but also from buildings and soil. Lead poisoning can stunt the brain development of children and increase their vulnerability to school failure, delinquency and crime. Michael Pell is part of the Reuters reporting team, and he joins us now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

PELL: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: How did this investigation get going?

PELL: So, after the Flint issue rose up a couple of years ago now, my reporting partner and I, Joshua Schneyer, started wondering what other communities had problems with childhood lead poisoning. I mean, was Flint the only city left in the United States that had this problem, or were there other communities that were also suffering? So, we set out to identify other Flints across the country.

CURWOOD: So, tell me about what you found. What do you have in this latest data report that you put together for Reuters?

PELL: So, what we found was that Flint was not the only community that was suffering from this problem, but there were hundreds of communities across the country that are suffering with childhood lead exposure. And what we wanted to do was find these neighborhoods that had not enjoyed the same success that other communities had, and to do that we needed to obtain data that would show at a granular level where kids were getting exposed. Previously, the only information available to the public was that these countywide maps that states made to show the percentage of tested kids in the county that had high lead levels. And what we found was that those countywide maps not only didn't really show the problem areas, but they actually could provide a false sense of security. Because if you look at the entire county, OK, sure, there's a small percentage of kids with high lead levels, but if you break that down by a neighborhood level what you could see is that there are some neighborhoods where a lot of kids are still testing very high for lead.

Residents in Orleans, New York, are concerned about high levels of lead in their water. Andy Greene (left) and Stephanie Weiss (right), with their children Sam (2nd left) and Leo outside their home, are among community organizers pushing for clean water. (Photo: courtesy of REUTERS/Chris Wattie)

And so, what we did was obtain data broken down by census tract or zip code from the states to identify these neighborhoods where kids still had high lead levels. And this was inspired by a story we wrote in East Chicago, Indiana. And in East Chicago there was this one housing development that was built on top of an old smelting site, an old industrial site, and the CDC study said there was virtually no chance of children being exposed to lead from that old site, and of course, then a few years later the mayor was evacuating this housing community. And we went back and took a look at the state's data and showed that the CDC's assessment was incorrect. The CDC claimed correctly that while the city as a whole had a low percentage of children testing high for lead, in the census tract where that housing development was located, there was a very high percentage of kids with elevated lead levels.

CURWOOD: So, where did you get your data for this project?

PELL: We obtained the data directly from state health departments and from the CDC. Many states provided the data very quickly, other states really dragged their feet and decided that they didn't want this information out there. States like Ohio, for example. And so what we had to do is go to the CDC and issue FOIA requests to them for the same data because in many cases the states report their blood lead level results to the CDC.

CURWOOD: Now, you were building on some previous data. What are the changes or additions that you saw since you started this project?

PELL: Sure, so what we've done is publish stories as the data comes in, and the most recent data that we obtained was from the CDC for New York City, Georgia, Tennessee, Kansas, and this has brought the total number of neighborhood areas with the percentage of tested children with elevated lead levels to double the level of Flint during the peak of that city's crisis to 3,800.

CURWOOD: Wow. So, in your research, Michael, what did folks tell you are typically the major sources of lead poisoning in children? Flint, we know was water, but what else do they say?

PELL: Well, so even in Flint it's commonly perceived that it's water, but there are kids that had high lead exposure before the problems with the water, and it's a tricky situation because a lot of people, a lot of public health experts don't believe water contributes significantly to a child's lead levels. Although in Flint, in Washington DC, and other communities we have seen that when there are problems with the water system, the number of children with elevated lead levels increases. So, it's extraordinarily difficult to determine what the sources are. What the data tells you is that where the lead ends up, and that's in the blood of children. Typically, experts believe that the major source of lead exposure comes from old, decaying paint, but I think that more and more research is being done to determine exactly where lead exposure is coming from and a lot of people are starting to think that maybe it is a cumulative effect – lead paint still being probably the driving factor, but that old lead plumbing fixtures also contribute, soil in people's yards. When that lead paint comes off their houses, when -- the exhaust that contained lead in the past from car fumes, that gets into the soil and that doesn't go anywhere. And so when you go outside, you play, kids stick their hands in their mouth, you track the dirt back inside your house, they're playing on the ground, that gets into a child's blood system as well.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about demographics here. To what extent do you see these exposures in lower income communities, communities of color, and that sort of thing?

PELL: Yeah, I think if you look at the map that we published you can see that these communities are often low-income neighborhoods, often neighborhoods, predominately people of color. You know places like Cleveland, Baltimore, Philadelphia. High percentages of kids there are testing high. On the other hand, sometimes when you look at the map you find communities that don't fit that profile. In New York, for example, we identified the neighborhood with the highest percentage of tested kids with elevated lead levels in southern Williamsburg, and this is a traditionally Hasidic neighborhood, and so it varies by community.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about the affected areas and what relationships, if any, there are among them.

PELL: Well, typically it's older housing, older housing that's poorly taken care of. And so, back to your question. These are often communities of color, these are often low socio-economic communities that are disproportionately affected by lead, but what we're also seeing is that gentrifying neighborhoods are also being affected. People move into these old houses, these historic homes, homes that have been painted for decades, if not 100 years with lead paint and they come in and they start renovating and that can kick up a lot of this old lead paint. What we also see is the communities that have a long industrial history. One census tract that we identified in Indiana, it doesn't have a tremendous amount of older housing, but what it did have was a lead smelter site in it, and there was a housing development built on top of that.

CURWOOD: So, in the course of this research you must have visited some interesting, and I imagine, alarming places. Give me your top five communities that you think are really in trouble from lead, if you're in a position to do so.

Antonin Bohac, a mechanic at the Brushy Creek Mine, a lead mine, discusses lead exposure with reporter Michael Pell. Mr. Bohac was diagnosed with high lead levels. (Photo: courtesy of REUTERS/Mike Wood)

PELL: Yeah, I mean top five, it would be very subjective here, but Buffalo, New York, has the perfect confluence of events. It's got a lot of poverty, it's got a tremendous amount of old housing, and we saw extremely high percentages of tested children there with elevated lead levels. In South Bend, Indiana, my reporting partner Joshua Schneyer visited that community and immediately found families that were dealing with this problem. They had almost run out of funding to conduct testing in this community, but after we published our report, the University of Notre Dame and the city stepped in to get more funding to test kids, and right now are working to identify lead exposures in homes there. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has a terrible problem. All throughout Pennsylvania, really, there are communities that are suffering with this and we were talking to the leaders of the health department in York, Pennsylvania, and they feel like they're trying their best, but every year their resources seem to dwindle, and it almost feels like they're overwhelmed by this problem, they don't know exactly what they can do to get a handle on this.

CURWOOD: What do you think are the social and economic and political costs of all this lead contamination in our environment?

PELL: Well, I've spent almost two years now talking to epidemiologists, public health experts, people that run nonprofits to provide healthy housing for people, and I think ultimately what we can safely say is that we know lead is a problem. I mean, there's no safe amount of lead in a child's blood system and that there are costs down the road for society as a whole. Lead causes permanent learning disabilities in children, it can cause behavioral problems, so that problem is not going to go away until we focus more attention on it, and we're trying to provide information for organizations like green and healthy housing to identify communities that are in the most need. So, that way they can in the future, instead of having to spend money on behavioral services for children with learning disabilities, they can instead provide additional education resources that take children to the next step.

CURWOOD: Michael, there's been research done by folks in Cincinnati at that university and medical facility; also in Pittsburgh, also in Boston and Harvard, research that shows a link between childhood lead exposure and crime. What do you make of that research and what does all this lead in our environment say in terms of crime and delinquency and public safety?

PELL: There's been a lot of research that has linked lead poisoning to crime. The behavioral problems that I was discussing and the inability to control impulses has been linked directly to lead poisoning. Exactly how much that costs and what the direct link is, is not absolutely perfect, but I think that there's enough smoke there that it suggests that there is a correlation. You know, in Baltimore, Freddie Gray, who was famously killed after an encounter with police, he had childhood lead exposure, and he had a history of run-ins with the police. The lead poisoning was probably one factor, and that's one factor that can be removed, you know, whatever else was going on in his life, it is possible to provide healthy, safe housing for people, and I think that there will continue to be research done showing that lead is a pervasive societal problem, both in terms of learning disabilities, in terms of its link to social unrest and hopefully the way that that's most conclusively proven is as housing becomes safer, as we provide better environments for children, the amount of crime in those neighborhoods will continue to drop, and the success in school will continue to increase.

Michael Pell is a reporter for Reuters who has been covering national childhood blood lead levels for years. (Photo: courtesy of Michael Pell)

CURWOOD: So, what plans are there to release these data widely and how are you going to do that?

PELL: So, after we published our first story we got a tremendous response from researchers, epidemiologists, other reporters who wanted to use this data, and we are now working on making the raw data that we received from states, from the CDC, available in a downloadable form. So you'll be able to go up and download an individual state or download data for every state that we received. And we hope that researchers will use this data to answer some of the tough questions that you asked today that, quite frankly, maybe we're just not smart enough to do. Questions about how does lead poisoning affect communities of color? How should public funding be used to identify children with lead poisoning and to identify where are the communities that need this help the most?

CURWOOD: In what ways has your reporting prompted cities, towns, localities to act?

PELL: That's been one the most gratifying things about this project is that we have seen a tremendous amount of concrete action on the ground. The state of California just last month passed legislation that will hopefully get more children across the state tested for lead poisoning, and the author of that bill cited our reporting as playing a role and prompting him to do this. In South Bend, Indiana, the University of Notre Dame, started a course, a chemistry-in-the-community type course, to go out and actually test children for lead poisoning. We've talked to public health officials in northern California that are trying to pass a law right now that would require more inspections of older housing.

The other thing that we've seen is that by providing this data, by letting people know that it's out there, we've seen other local media start to pick this up as well, and I'd love to see communities that have problems in Pennsylvania and Michigan and Ohio, some of these states, I'd like to see the media there continue to report on this every year, make it kind of an annual story when the local blood lead level data comes out, they do a story on it to keep the pressure on public health officials.

CURWOOD: Michael Pell is a reporter with Reuters. Thank you so much, Michael.

PELL: Thanks for having me, Steve. I really appreciate it.

Related links:

- Reuters: “Reuters finds 3,810 U.S. areas with lead poisoning double Flint’s”

- Reuters: “Special Report: Thousands of U.S. areas afflicted with lead poisoning beyond Flint’s”

- CNN: Timeline of events in Flint, Michigan during the city’s water crisis

[MUSIC: John Zorn, “Bikkurim” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PYYNg8SbdqU]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The dangerous chemicals that can lurk in your dust bunnies.

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth, keep listening!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and from a friend of Sailors for the Sea, working with boaters to restore ocean health.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rick Braun, “Coolsville” Body & amp; Soul 2010 Mesa/Bluemoon Recordings, Inc.]

Science Note: The Power of Dust

Ecosystems with intense erosion, like the Sierra Nevada mountains, can benefit greatly from the minerals in airborne dust. (Photo: Don Graham, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood. In a minute, dangerous house dust –– but first this note on emerging science from Noble Ingram.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

INGRAM: If you’re looking to do some spring cleaning, it can be a big nuisance. But ask any gardener, and you may be surprised to hear that dust is good for more than just collecting in odd corners. A research team from several Western and Midwestern universities has shown that rock dust plays a critical role in feeding the soil of the Sierra Nevada mountains.

Older mountain ranges, like the Sierra Nevadas, experience heavy rainfall and intense erosion, costing them significant soil nutrients in runoff. In California, dust rich in plant-boosting elements like phosphorous, offers the perfect refreshment to these weathered environments.

Air currents collect the nutrient-dense cargo from deserts and dry valleys and carry it vast distances. Researchers found that between 18% and 45% of deposits in the Sierra Nevadas came from Asia, crossing the Pacific Ocean. Some dust was even detected from the Gobi Desert on the border of China and Mongolia, more than 6,000 miles away.

Despite its beneficial effects, this mineral mobility leaves some scientists worried. Bounties of imported nutrients may help a forest thrive, but they can wreak havoc on surrounding rivers and lakes. Dust-fed algae blooms suck up oxygen and threaten to suffocate fish and crustaceans.

With drought spreading as climate change advances, geologists suspect dustier forecasts are ahead. And cleaning up the potential ecological upsets in their wake will require more than a feather duster.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Noble Ingram.

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Related links:

- EurekAlert! press release: “Dust contributes valuable nutrients to Sierra Nevada forest ecosystems”

- The Study in Nature Communications: “Dust outpaces bedrock in nutrient supply to montane forest ecosystems”

Obesity and House Dust

House dust under high magnification. (Photo: NIAID, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

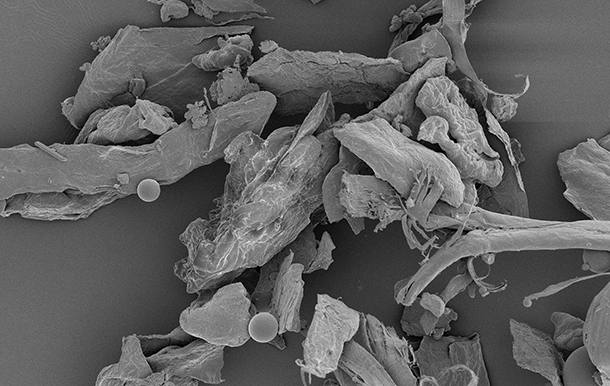

CURWOOD: Those dust bunnies under beds might not worry you that much, but research from Duke University might have you reaching for the vacuum. It turns out dust is not always benign, and ironically, cleaning products can be part of the problem. Chris Kassotis is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Nicholas School for the Environment at Duke. He has discovered household dust contains traces of hormone disrupting chemicals such as triclosan. And that dust spurred the growth of fat cells in a lab dish. Triclosan is among common products including plastics, flame retardants, and pesticides that are known to affect hormones, as well as neurological, reproductive and immune functions. The research is published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, and Chris Kassotis joins us -- welcome to Living on Earth!

KASSOTIS: Hi. Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Chris, I was just amazed to see your study that says, essentially, I could be getting fat because I'm exposed to household dust, and the last time I looked, well, my housekeeping isn't perfect. There is dust there. How did you come to the notion that, wow, household dust could be making people fat?

KASSOTIS: Yes, it's a great question, and it's an important point. So, we definitely are not saying that house dust will make people fat. This is a preliminary step in that pathway. So, first, we're showing that house dust can stimulate the development of fat cells in the lab.

CURWOOD: But, wait a second. Doesn't that raise the specter that, at the end of the day, that therefore it could be making me fat?

KASSOTIS: So, it is testing that mechanism; however, it's a little too early to say that it would act the same way in an animal or ultimately in a human.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me some about the methodology of this study and describe what you did to test how these dust samples, in fact, seemed to simulate fat cells.

KASSOTIS: So, yes, in this study we used a mouse fat cell line. So, these are essentially fat precursor cells. If we think about the development of any differentiated or final cell type, like a bone cell or a fat cell in the body, these are fully developed cells. So, this cell model is cells that are committed to become fat cells at some point in time. They can't develop into any other cell type at this point, but, without some sort of further push, they're going to sit in their early state and not take on the characteristics of what we think of as a mature fat cell.

Adipose tissue containing fat cells. (Photo: RachelHermosillo, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

However, if they get that push, which we can give them by exposing them to some of these environmental contaminants, over the course of two weeks in the lab they then undergo a series of changes. So, they become more spherical in shape, and they start to accumulate lipid into the cell. Ultimately what we do is, we measure the lipid content of these cells, and then we also measure the number of these cells, and we found that these various contaminants can both increase the lipid content, we would think of this is a rough proxy for fat cell size, and they can also increase the number of cells which can create a larger pool for recruiting mature fat cells.

CURWOOD: Larger, rounder...sounds like fat. [LAUGHS] Sounds fatty, anyway. How big a deal is your study? What's the breakthrough here?

KASSOTIS: So, I think the interesting thing for me is that exposure to an environmentally relevant mixture, which is house dust, at very low levels, caused the development of fat cells in the lab. And when I say very low levels, what we're talking about is the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that a child consumes about 50 mg of dust per day, which is a very small amount, but the level of dust that spurred fat cell development in our study is 10,000 times lower than that. So, while there isn't a direct translation from a concentration that we use in this model to a dose that a child eats, the magnitude of that difference is concerning to us.

CURWOOD: Chris, you've got me scared. I mean, if I don't run the HEPA vacuum cleaner at my house, and a very young person comes through, it sounds like I could very well be putting them at risk of a lifetime of obesity. You don't know that yet, but that's the suspicion.

KASSOTIS: So, I will say that there are still a lot of gaps in our understanding of this topic, and there isn't a good understanding at this moment as to what level of exposure to a certain chemical results in a health effect. So, it's far too early to say that, you know, someone visiting your house would receive exposure to a chemical, and that would result in some sort of health effect.

What we normally tell people is, if you're concerned, then there are plenty of steps that can be taken to reduce exposure to these chemicals. So, one of the things that we often tell people is that dusting frequently is a good way to reduce exposure. With that said, we suspect that dry dusting may just actually kick these chemicals back up in the air and make it easier to inhale them. So, it really should be a wet dusting to avoid increasing your exposure to these chemicals.

Chris Kassotis is a researcher at Duke University. (Photo: courtesy of Chris Kassotis)

CURWOOD: So, a fat kid might say, “It's not my fault. It's not the soft drinks I’m drinking or the potato chips. It is the fact that my parents, well, they didn't clean the house as often as they might have.”

KASSOTIS: Well, ultimately we don't know enough to say whether that's going to be a contributory factor in humans, certainly. What I can say is that we do have some compelling studies in animals where they have exposed an animal during gestation -- so, while they're still in the mother -- and then controlled for food intake and controlled for exercise and monitored weight gain. And the animals exposed to the chemical gained more weight than the animals that weren't, suggesting that it's not just about exercise, and it’s not just about the amount of food you eat. The exposure to that chemical may have reprogrammed your metabolism in some way, such that your body handles nutrients and calories differently than other people -- or other animals, because that work has all been done in animals.

CURWOOD: So, what comes next in terms of this research?

KASSOTIS: So, I think two things stand out to me. The first is seeing if rodents -- you know, mice or rats -- exposed to house dust, probably via their diet in some way, show some sort of metabolic risk or disruption, whether that's weight gain or some other outcome that we can measure. The second thing is looking for an association with humans. So, that's going to take a larger study with a lot more house dust, and we commonly talk about children being the most sensitive to exposures of this type, so it may be that we really have to look at young adults or children and their metabolic health to find any sort of connection.

CURWOOD: Chris Kassotis is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Nicholas School for the Environment at Duke University. Chris, thanks so much for taking the time today.

KASSOTIS: Thanks so much for your interest.

Related links:

- Environmental Science & Technology: The study on house dust and fat cell growth

- NBC: More Evidence Chemicals Linked to Obesity and Diabetes

- About Chris Kassotis

Bitcoin, The Energy Hog

Bitcoin is today’s world’s most commonly-traded cryptocurrency. Over the course of 2017, the value of a single Bitcoin increased from around $1,000 in January to over $18,000 in December. As of August 2018, its value is back down to around $6,000. (Photo: Christoph Scholz, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: Bitcoin is perhaps the best known of the new digital currencies and its value can vary widely. You can’t hold Bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies in your hand, as they are created by complicated computer programs. And they require massive amounts of energy.

Here’s why: every transaction related to their creation is verified by a key group of online users called miners, who collect those records into groups known as blocks, and then compete to get their block added to the chain of record. Every 10 minutes or so, one block is randomly selected, winning that miner a prize of new Bitcoins, and the rest are discarded.

DEVRIES: Each miner gets to submit their own numbers and they’re doing that every second of the day. They’re submitting a huge number of numbers.

CURWOOD: That’s data consultant, Alex de Vries, who has calculated Bitcoin’s energy costs, and spoke to us from Amsterdam. According to his Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, submitting all those numbers demands so much computing power that Bitcoin consumes more electricity than 159 individual countries. But Alex De Vries says the high carbon cost is intentional.

DEVRIES: Well, the energy costs are part of the reason why Bitcoin is so secure, because if you want to attack the system, first of all you need the machines and you have to spend a huge amount of money to pay for all the electricity to simply take control over the network. So, in essence, it's really part of what makes Bitcoin secure.

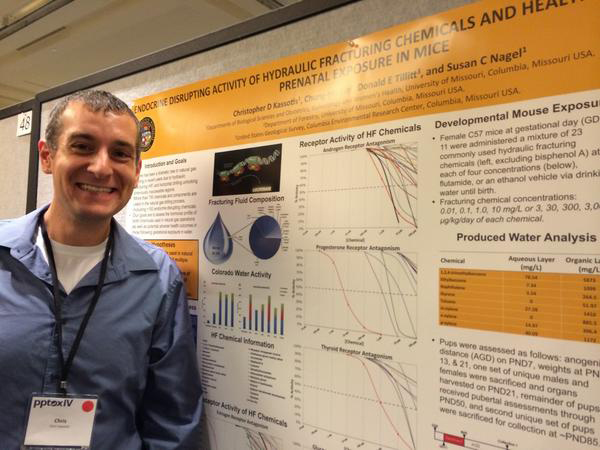

According to the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index that Alex de Vries developed, Bitcoin’s overall energy cost increased nearly fourfold between August 2017 and August 2018. (Photo: Alex de Vries)

CURWOOD: By the way, how many, if any, do you have and if you do have them when did you buy them?

DEVRIES: [LAUGHS] Well, I should have bought a lot, though I actually had some bitcoins back in the day, but I already sold them in 2015, so no, I'm no Bitcoin millionaire. I do know that at some point I learned about the energy consumption because before 2015, I didn't know Bitcoin was consuming such a huge amount of electricity. Because as a user you're never confronted with these costs. The electricity bill ends up at the miners, so you'll never see how much energy is being consumed by the system.

CURWOOD: What about the creation of these Bitcoins? How much energy does it take to create one bitcoin?

DEVRIES: Well, something like fifty thousand kilowatt hours per mined Bitcoin.

CURWOOD: Fifty thousand kilowatt hours. And how much does a kilowatt hour of electricity cost?

DEVRIES: It depends on where you are. In the US, the average residential rate is probably 10 to 12 cents per kilowatt hour. If you're in China, it's a lot cheaper. Then, you're probably paying just four to five cents per kilowatt hour, and in total the whole network is paying an amount of almost $2 billion US dollars per year just to mine Bitcoins.

The Tianjin Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle Power Plant Project in Northeastern China. Coal is a critical energy source in the country and Bitcoin mining is known to capitalize its cheap power. (Photo: Asian Development Bank, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So, where in the world are Bitcoins most commonly mined these days and what kind of energy sources do these mining operations typically employ?

DEVRIES: So, what we see is that most of the miners are actually located in China, which makes the energy consumption problem a whole lot worse because China doesn't have a very clean electricity grid. From several miners, we know that they are located very near to coal-based power plants, so they are drawing a lot of coal-based electricity. That causes the carbon footprint of each Bitcoin transaction to be gigantic as well.

CURWOOD: Now, as I understand it there's a limit to Bitcoins, that there will only ever be some, what, 21 million in circulation, and at that point I would imagine that it might not consume as much energy as they do now -- or maybe I'm wrong there.

DEVRIES: Well, you're indeed right there will never be more than 21 million Bitcoins. They're released slowly over time as a reward to those who are mining Bitcoin. Bitcoin once started with a block reward of 50 Bitcoins, meaning that every one who created a new block for the block chain would get 50 Bitcoins. Nowadays, that is just 12 and a half Bitcoins per block, so it has already halved two times and it will keep on halving every four years and in a few decades all Bitcoins will be mined and there will be no more block reward. Now, you could say that might lower the energy cost simply because if the reward goes down so will the amount miners are spending on electricity, but that's a bit too simple unfortunately because as a user you're also paying transaction fees. And the whole idea is that those transaction fees, which are also claimed by the miners, will end up supporting the Bitcoin infrastructure.

Bitcoin mining demands massive amounts of computational power. Most mining operations are comprised of networks of highly efficient computers working in tandem. (Photo: Nathan 11466, CryptoCurrency 360, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Because this system requires a lot of computer power and computer sophistication, it would seem to be adding to the financial fortunes of the elite as opposed to the general population of our planet. Your view?

DEVRIES: So, the strange thing is that even though we do end up with that result, it's not because of the energy cost because the energy costs, they aren't paid by the user, so that's not a problem. The only problem is that as a user you are paying for something, you are paying for getting priority in getting processed by the Bitcoin network. The whole network can effectively process only three to four transactions every second, so that's a very very small amount and if you want to be processed in a reasonable amount of time, you're going to have to pay a certain fee.

Alex de Vries is a data consultant and the founder of Digiconomist.net. (Photo: Alex de Vries)

In December, we actually saw that the average fee paid by people to simply get priority in being processed was around 26 dollars per transaction. So try to imagine if you are paying for a cup of coffee and you have to pay at least 26 dollars in transaction cost simply to have your transaction processed, that's definitely not something that you're going to be able to afford if you are poor. So, in that way it's actually going to contribute to raising economic inequality over time, or at least that's something that might happen.

CURWOOD: Look ahead at the future of cryptocurrencies. To what extent are these going to replace government issued currencies ... the Dollar, the Pound, the Euro becomes irrelevant?

DEVRIES: Oh boy, you know, I don't know. I don't think it will replace the dollar. I do think that there will always be a niche for Bitcoin. You will always have countries that are facing hyperinflation, monetary systems that are collapsing. Places like that are actually pretty nice places to start a virtual currency. Now, if we're talking about the US, do we distrust our financial institutions that much that we desperately want to get away from them and all dump our money in Bitcoins? Well, you know, I have no problem with my bank. I trust my bank. I'm fine with them doing my financial transactions, so I don't really need Bitcoin.

CURWOOD: Alex de Vries is a data consultant and founder of digiconomist.net. Thanks so much, Alex, thanks for taking the time.

DEVRIES: And thank you very much.

Related links:

- Digiconomist Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index

- Vox: “Bitcoin’s price spike is driving an extraordinary surge in energy use”

- Ars Technica: “Bitcoin’s insane energy consumption, explained”

CURWOOD: Your comments on our program are always welcome. Call our listener line anytime at 617-287-4121. That's 617-287-4121. Our e-mail address is comments at loe dot org. - comments at loe dot org. And visit our web page at loe dot org. That's loe dot org.

[MUSIC: Glen Velez, “Pan Eros” on Pan Eros, CMP Records]

CURWOOD: Just ahead – Rats have a taste for music, and they laugh when tickled! Stay tuned to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at race to nine billion dot com. That’s race to nine billion dot com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Medeski, Martin & Wood. “Chasen vs. Suribachi”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ky5wxd6JPs0]

Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind

The octopus is sometimes depicted as a monster -- Victor Hugo described these deep-sea creatures as horrifying – but writers Sy Montgomery and Liz Thomas say octopuses are far more personable than we realize. (Photo: Scott Ableman, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[DOOR CREAKS OPEN, DOG BARKS]

CURWOOD: Hello?

On a warm afternoon in late summer Thurber, the Border Collie, welcomes me into his home.

[DOG BARKING]

CURWOOD: He shares an old New Hampshire farmhouse with writer Sy Montgomery, and today they are joined by author Elizabeth Marshall Thomas.

Sy is an old friend of Living on Earth who over the years has celebrated pigs, octopuses, sharks, pink dolphins, moon bears, and more with stories from around the globe. Elizabeth Marshall Thomas is noted for writing “The Hidden Life of Dogs”, a groundbreaking book probing dog psychology.

The Stunt Dog Experience is a travelling circus show that takes in abandoned dogs and trains them to perform for a crowd. According to Sy Montgomery, dogs want tasks to occupy their time and enthusiastically take on jobs. (Photo: Branson Convention and Visitors’ Bureau, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

Sy heads outside into her garden.

MONTGOMERY: I will lead the way...

[SOUNDS OF WIND, BIRDS, OUTSIDE THE HOUSE]

CURWOOD: These best-selling authors have teamed up on “Tamed and Untamed, Close Encounters of the Animal Kind”, a book of essays that explores how wild and domesticated creatures and people relate. The essays are adapted from a Boston Globe column they co-wrote that sometimes offered advice that, as Sy admits, raised some eyebrows.

MONTGOMERY: We kind of got in trouble for our first Q and A.

CURWOOD: Uh-oh.

MONTGOMERY: Someone wrote in and they said you know I've got this dog who barks, and I love him so much, and now I have this new boyfriend, and he doesn't want me to keep the dog, which I do. And we said, you know, we normally don't recommend euthanasia, but your boyfriend has got to go! [LAUGHS]

CURWOOD: So, you wrote this book with, with Sy Montgomery, Elizabeth Marshall Thomas but both my producer, Noble, and I, when we were reading the book had a lot of trouble figuring out whose voice was whose. For each story in it, you had the same voice. How did that come about?

THOMAS: Maybe we just had the same voice before we ever met. I bet that's it.

MONTGOMERY: We did think about that, and that's why with each chapter at the top we reveal which one of us is speaking, but I think Liz has been a very big influence on my writing. I think we come from the same heart. I mean, what we're saying in this book, in every single essay, whether it's about hyraxes -- these little groundhog-sized relatives of elephants who live in Africa -- or an octopus at the New England Aquarium or the dog at your feet, these lives are so fascinating, so intricate, so mysterious, so thrilling, and so worthy of our respect and affection and awe. That's what we're saying in every single essay, and that may be why that kind of heart comes through.

CURWOOD: There's a theme throughout your book. It's a finger-wagging theme about people who abandon their animals, who abandon their pets.

THOMAS: Yeah, I have two cats at home who my neighbor found as kittens by the side of a long empty road. Somebody just tossed them out of a car. And she couldn't take them, but I could. She called me and I, of course, came and got them. [LAUGHS] And they're with me now. They're wonderful cats. They were Russian Blues, and if you buy one it's expensive so the person didn't even know that she could have sold them for hundreds of dollars. I mean, but that's not the point. The point is that, how can you do that? How can you do a thing like that?

Another woman released a rabbit in my field, and the rabbit had never been alone before, and he'd never been out in the wild before, so to speak. He had no idea what to do. And also it was in the middle of the field so he could be seen from every direction. He wasn't happy about that, and he saw our house in the distance, and he came to it and he went into the garage.

The woman, I'm sure she was letting him free. She thought that animals are on automatic pilot. When they get in the woods, they’ll know exactly what to do, and he'd be happy, and so it wasn't an evil thing on her part. But it didn't work. The dogs found him before I did, and they killed him. And I think people don't think along those lines.

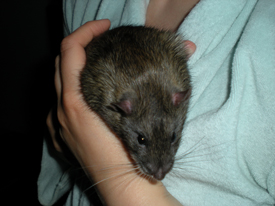

Rats get a bad rap, says Sy Montgomery, but they’re much more like humans than we think. One of our shared characteristics is laughter. (Photo: zemasterdod, Flickr CC BY-SA 2.0)

We're alike in every other way with every other mammal. OK? We have hearts, we have livers, we have kidneys. But the brains aren't the same? Of course they're the same. Why wouldn't an animal feel the same way we do? Of course, they do.

MONTGOMERY: And the idea that animals don't think is insane. I mean they don't think about their shopping lists. They don't think about what they're going to wear tomorrow, but they think. And anthropomorphism is one of those bugbears that we take on also in the book and in our columns and in our other work. The idea that, when you talk about an animal having thoughts and feelings, that this is anthropomorphic, well, that's ridiculous. Of course they have thoughts and feelings. A much worse mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

It's easy to make a mistake and even with a human being attribute your own thoughts and feelings to them. All of us have bought a birthday present for someone that didn't go over. All of us have asked someone out on a date that didn't want to go. And that happens with animals too. One of the essays is about this, in fact, that people can make mistakes like the veterinarian who thought that the Tasmanian Devil was so calm, it was yawning. Well, then it bit her. It was a gape threat, it wasn't a yawn. But you know you can make that mistake, but a much bigger mistake is to think that they don't have thoughts and feelings.

THOMAS: There's a new word in the English language, and it was invented by...He's a famous scientist. He's a biologist and primatologist, Frans de Waal. He invented the word “anthropodenial” which is the opposite of anthropomorphism, and it means presenting an animal as if it did not have human characteristics.

CURWOOD: Now, I think Sy wrote this essay, about going to see a sort of a dog circus.

MONTGOMERY: Oh, yes, we went together. Liz wrote that, but I took her.

THOMAS: Oh, yeah.

MONTGOMERY: That was... what was it? It was some kind of celebration. It was so much fun.

THOMAS: It was fabulous, and what we saw! All the dogs in the show, they did things you've never seen a dog or a person or anything do before.

CURWOOD: Like?

THOMAS: Well, one dog jumped up, a little dog, jumped up on his owner/trainer's hand and stood on her front legs on his hand with her hind legs in the air, and he lifted it up like that, and she -- I reach my arm way up in the sky [LAUGHS] -- He lifted his arm way up and she retained the pose and came down. I mean a person couldn't do that. I mean a person can't do a lot of things. That's no comparison. But they would be trembling with excitement, and then they'd be called to do something, and they would rush off and do it. They loved it.

Like this chicken, Sy Montgomery’s flock of hens roams freely during the day. Though these clucking birds are often considered unintelligent, the writer argues that they are quite smart, and can even develop distinct names for the people and animals around them. (Photo: Grey World, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

All of these dogs were strays or abandoned or from shelters or they found on the street wandering homeless, dogs that somebody else thought was worthless and tossed them, and these dogs were phenomenal, what they were able to do. So, this is what people toss when they get rid of their pets.

MONTGOMERY: Some people think like, “Oh, you know, training a dog is just forcing it to do some horrible thing that…” No, they love having something to do, as do a lot of animals. They'd rather have something to do than nothing to do all day.

THOMAS: And people are the same, so there we are.

MONTGOMERY: And they love our company, and in fact, Thurber, our dog, is taking -- I kind of hate to admit this because I purposely did not have children -- but he's taking dance lessons right now.

THOMAS: [LAUGHS] My dogs are learning not to pee in the house.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Now, so you're teaching your dog to dance. Sy, in this book there's another dance scene with...

MONTGOMERY: Snowball, the Dancing Cockatoo!

CURWOOD: So, describe this for me.

MONTGOMERY: Well, I actually found out about Snowball the Dancing Cockatoo on YouTube. He was an unwanted bird. He was dropped off at this parrot rescue facility in Indiana, and he came with a CD. And when he was dropped off, the fellow told Irena Schulz, you should play that and see what happens. Well, she had a lot of birds to take care of, so she didn't get a chance to do it right away, but when she did, she put it on. It was by the Backstreet Boys, it was one of their really great rockin’ songs.

[BACK STREET BOYS MUSIC. Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

MONTGOMERY: Well, the Cockatoo starts rockin’ out.

[SOUNDS OF COCKATOO CALLING]

MONTGOMERY: His crest is rising. His wings are spreading. His tail feathers spreading. His feet are going up and down, and he's doing it to the beat of the music. He's also calling out.

[MUSIC: Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas co-wrote Tamed and Untamed, a collection of essays adapted from their Boston Globe column by the same name. (Photo: Chelsea Green Publishing)

MONTGOMERY: She makes a video of this, puts it on YouTube. It went viral. Well, turns out, this was the beginning of an important discovery about abilities that parrots have.

MONTGOMERY: They have an ability that was previously thought to belong only to so-called higher minds like ours, and that is called “beat perception and synchronization.” They can anticipate the next beat, even though, for you and me, we unconsciously tap our feet to the beat, but other animals apparently can't do this, but parrots can, and it's probably associated with vocal learning.

So, I, of course, had to see this. I had to write about it, and I spent one of my birthdays with Snowball rocking out to the tunes of my choice.

[MUSIC: Backstreet Boys, “Everybody” on Backstreet’s Back, by Denniz PoP/Max Martin, Jive – Transcontinental Records]

MONTGOMERY: A researcher named Ani Patel did a project on this. He had written a wonderful book on music and the brain, and he also saw this YouTube video and worked with Irena Schulz to produce, actually several papers now. He found that lots of parrots can do this, and some other birds can do it, and it only works with certain tempi.

CURWOOD: You know, correct me if I'm wrong, but I think at some point in your book you say that rats like music.

MONTGOMERY: Yes, rats do like music.

CURWOOD: What kind of music?

MONTGOMERY: Well, you know I don't think this has been as systematically tested, but rats are very like us in many ways. Rats laugh. If you record it and then speed it up or slow it down, you can hear them laughing, and they laugh when they're tickled, just like we do. And these are animals that everybody thinks of as vermin, and yet they are so like us. They enjoy the same kind of stuff that we do.

THOMAS: Well, we use rats, we use mice for experiments that we think will help our bodies, so we may think we're nothing like them, but of course we really are, biologically speaking, just physically speaking.

MONTGOMERY: And we can sometimes get to animals’ thoughts, and rats are one of the species that we can sometimes almost literally see their thoughts. When they run a maze, you can see what their brainwaves are doing as they come to different parts of the maze. And recently there was an experiment looking at what their brainwaves looked like when rats were dreaming. And they could see the brainwaves were exactly the same as when the rats were running the maze. The rats were dreaming about their work, just like we dream about our days and our work.

CURWOOD: In the book, there was, well, kind of this theme of animals with bad reputations among certain humans. How conscious was that decision, do you think?

MONTGOMERY: I think we, we really did want to rehabilitate some of these reputations for animals because, if you remove a bad reputation, you can begin to appreciate the creature for what it is. Rats are one example. Great white sharks. Octopuses even. Octopuses were thought of as these horrible monsters that -- Victor Hugo certainly didn't do them any good in the PR department -- but they're not at all. It's just preconceived notions, and it's fun to knock those down and instead welcome people into the company of these great animals and appreciate them for what they really are.

THOMAS: Yeah, and there are ways of looking at it. I was thinking of, I think, it's in one of the essays. If you see a fly or something like that, you swat it.

CURWOOD: Even as Elizabeth Marshall Thomas makes her point, it’s clear that any stray insect or tick in Sy Montgomery’s expansive yard is likely to be gobbled up by an ever-present flock.

THOMAS: If an eagle, a magnificent eagle, was the size of a fly, you would swat it.

[SOUNDS OF CHICKENS]

CURWOOD: Now, these ladies they’re are two-legged, and they have these red combs. They're chickens. They're coming towards us. Someplace in this book you say that chickens actually name people, or they seem to.

MONTGOMERY: Yeah, this was not my discovery. This was my friend and colleague Melissa Cowie’s discovery. She's the author of a kid's guide to keeping chickens, which is how I met her.

Sy Montgomery (left) and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas (right) pose with Montgomery’s beloved border collie, Thurber. They spoke with Steve Curwood at Montgomery’s New Hampshire farmhouse. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

Well, she was out with her hens one morning, just throwing scratch, and noticed that one of her chickens, a six-year-old named Oyster, was using a different voice than usual, and she knows what her chickens are saying. She's decoded quite a number of different vocalizations, like, “Oh I've just laid an egg”, or “Hi, how are you?”, or “Oh my God, there's a hawk over there!” They have lots of different things that we know what they say. But there was this one vocalization that she'd never heard before, and soon everyone in the coop was using it, and they just used it when Melissa walked into the coop. Well, we figured out that that was the name the chickens had devised for her.

And this happens with a lot of animals. They have specific names for specific events, specific predators, or maybe even specific people, and the fact that a regular person, just paying attention to the chickens in her backyard, made this huge discovery about the intelligence of an animal that so many of us think of as ordinary, just shows us how splendid and exciting this world is, no matter what animal or plant or landscape you set your eyes on. There's just so much out there to be revealed.

In a book like this what you're trying to get across is, “Isn't this Earth splendid? Aren't these animals wonderful? And don't we owe them our affection and respect?”

And, even though this is just a book of essays that we loved writing, it's part of a growing assemblage of writing from people who are really, I think, believing that we can build a more compassionate world. You alter your behavior, once you realize that this chicken loves her life. She doesn't particularly want to have her head chopped off and her flesh eaten, and, you know, the ocean which is full of octopuses and sharks and fish, we can't be dumping pollutants and garbage and plastics into it, if these individual lives are going to suffer. We can't continue to alter the climate of our world if we realize it's full of lives just as wondrous as our own.

CURWOOD: Sy Montgomery and Elizabeth Marshall Thomas are co-authors of "Tamed and Untamed: Close Encounters of the Animal Kind". Thank you both for spending this time with us.

THOMAS: Oh, thank you so much for having us.

MONTGOMERY: We're so glad that you came.

Related links:

- Chelsea Green Publishing webpage on Tamed and Untamed

- More about author Sy Montgomery

- More about author Elizabeth Marshall Thomas

- Boston Globe column on chickens, written by Sy Montgomery

[MUSIC: Earl Oliver’s Jazz Babies “Chick, Chick, Chick, Chick, Chicken (Lay a Little Egg for Me)” 1926 Edison Record https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GHTocMZd__w]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Thurston Briscoe, Savannah Christiansen, Jenni Doering, Anna Gibbs, Don Lyman, Maggie O’Brien, Aynsley O’Neill, Sarah Rappaport, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show, with help from Jeff Wade. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, on iTunes or Google Play music - and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. And we tweet from @livingonearth. I’m Steve Curwood, thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you our listeners and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong clean energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth