March 29, 2019

Air Date: March 29, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Brazil To Grab Indigenous Lands

View the page for this story

A constitutional crisis looms in Brazil as its new president, Jair Bolsonaro, seeks to open the Amazon tropical rainforest to more development. The country’s native tribes have a constitutional right to reject any development on their territory, but President Bolsonaro recently said he will allow mining on indigenous land without their consent. Sue Branford writes for Mongabay and joined host Bobby Bascomb to discuss the threats mining poses to indigenous culture and the environment. (09:49)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week in beyond the headlines, Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss how kale is now on the “Dirty Dozen” list of produce with high levels of pesticides, according to the Environmental Working Group. In other pesticide news, they talk about how glyphosate is now a hot commodity for lawyers. Glyphosate is also being found in Canadian honey samples. And from the history vaults, they take a look back an early study of plastic pollution in the oceans and note a whale recently washed up in the Philippines with 88 pounds of plastic in its belly. (04:01)

Losing Ground: Midwest Floods Rip Away Topsoil

View the page for this story

Record flooding along the Missouri and Mississippi River basins is wreaking havoc on Midwestern farmers. Much of the soil where staple crops are grown has been washed away, threatening the livelihoods of farmers in the corn belt of the United States. Brian Kahn, senior reporter for Earther, joins host Steve Curwood to discuss the link between climate disruption and misfortune for Midwestern farmers. (09:39)

BirdNote®: The Rainwater Basin of Nebraska

/ Michael SteinView the page for this story

Spring rains bring out the green and help water crops. And in south-central Nebraska, they provide watering grounds for migrating birds including the Sandhill Cranes. BirdNote®’s Michael Stein has more. (02:25)

The Place Where You Live: Chadron, Nebraska

/ Abigail McFeeView the page for this story

Living on Earth gives voice to Orion Magazine’s longtime feature where readers write about their favorite places. In this week’s edition, Abigail McFee takes us back to her childhood in a small town in Nebraska and describes how the place echoes with history in every corner. (06:06)

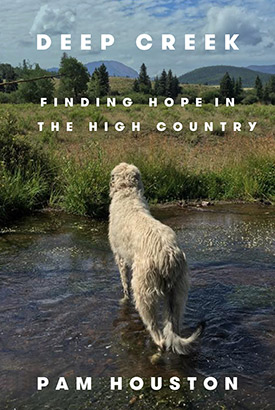

Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country

View the page for this story

In her new memoir, “Deep Creek,” writer Pam Houston describes finding refuge in a 120-acre ranch high in the Colorado Rockies. As she cares for her Irish wolfhounds, horses, donkeys, and Icelandic sheep through gorgeous summer days and frigid 35-below winters, and marvels at the local wildlife, the ranch serves as her sanctuary after a childhood of abuse and neglect. Pam Houston speaks with Host Bobby Bascomb about how, even as the changing climate threatens to destroy her beloved ranch with wildfire, she aims to “love the damaged world and do what I can to help it thrive.” (14:28)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Sue Branford, Pam Houston, Brian Kahn

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Abigail McFee, Michael Stein

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Brazil’s new president, Jair Bolsonaro challenges the constitution to open Indigenous land in the Amazon for mining.

BRANFORD: It is very much this thinking that Brazil has all this mineral wealth that should be exploited by Brazil, they shouldn't not be used just because what they see as a handful of Indians want to conserve it. But, this is widely seen in Brazil as a backward way of thinking.

Also, record flooding in the Upper Midwest has depleted the region’s deep fertile soil.

KAHN: So, you had this really saturated soil, this thick layer of snow, and then you had all of a sudden this huge influx of rain a few weeks ago. And that's how we ended up with a massive amount of water basically scouring these fields. So, instead of depositing nutrients, it basically ripped the nutrients out of the soil.

That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Brazil To Grab Indigenous Lands

The Amazon rainforest is threatened by mining interests, but under the Brazilian Constitution, indigenous tribes within Brazil have been able to reject development. (Photo: Amauri Aguiar, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

A constitutional crisis looms in Brazil as its controversial new president, Jair Bolsonaro, seeks to open the Amazon to more development. Before the 1950s the interior of the Brazilian Amazon was solely occupied by the indigenous tribes who'd been living there for millennia. But starting in the 50s and 60s the Brazilian government began a program to encourage people to settle the Amazon and make it productive.

[PORTUGUESE ANNOUNCER WITH VOICEOVER: It is not enough to build roads. We must colonize for agriculture or for cattle. The land is good. There are green pastures in the forest made of milk and honey. MUSIC FADES]

BASCOMB: The government built a new capital city, Brasilia, at the edge of the rainforest and moved full steam ahead on exploiting the land with little thought for the native tribes living there. Then following the collapse of the military dictatorship, a new constitution was written in 1988, which for the first time gave native tribes legal ownership of their land and the constitutional right to reject any development on their territory. The new president of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro, recently announced plans to reverse those rights and allow mining on indigenous land, despite protests from native tribes. President Bolsonaro came to power promising to clean up the government after two former presidents wound up in prison for corruption and money laundering. Sue Branford writes about the Amazon for Mongabay and joins me now. Sue, welcome to Living on Earth!

BRANFORD: Nice to be here again.

BASCOMB: So, Brazil's constitution is pretty clear about the land rights of indigenous people. It says that they have an inalienable right to a veto for projects like this. So how exactly does the Bolsonaro administration think that it can go against the constitution?

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro (Photo: Palácio do Planalto, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRANFORD: Well we're not absolutely clear. I mean, there are various way forwards, it will probably be quite difficult for them to take the correct route, which is really a constitutional amendment, which would have to go through Congress. It's more likely that Bolsonaro will decide on a presidential decree, which will at least allow him some time to overrule the Constitution. I mean, he has got a big majority in Congress, and the agriculture and the mining lobbies in Congress are very strong. So I don't actually think he will have any really long term problem. I think what he's going to confront is a lot of opposition from environmentalists, from campaigners, from the Indians themselves. Because for the Indians to win these rights over their land was a big conquest in the 1988 constitution. It was what seemed to be a sea change, that for the first time, Brazil was recognizing that these original inhabitants had the right to their land and had the right to decide what they were going to do with it.

BASCOMB: What are they planning to mine for and what are the potential environmental impacts of that?

A youth from the Yanomami peoples of the Amazon. President Jair Bolsonaro says he will continue advancing mining interests without the consent of indigenous tribes such as the Yanomami. (Photo: Sam Valadi, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BRANFORD: Well, the Amazon has an awful lot of minerals. It's got big gold reserves, probably the largest in the world. It's got silver, it's got bauxite. There is a lot of mining wealth under indigenous land. And so it is very much this thinking that Brazil has all this mineral wealth that should be exploited by Brazil, they shouldn't not be used just because what they see as a handful of Indians want to conserve it. But this is widely seen in Brazil as a backward way of thinking. That particularly now when we're getting more and more concerned about global warming, there's a growing number of Brazilians who feel that the forest, the Amazon forest, should be conserved, that if we go on, if Brazil goes on cutting down the forest, that Brazil is going to reach a turning point. Because scientists have been saying for many years now that once about 25% of the forest is felled, then you're very likely to spark off a whole process by which the rich tropical forest is transformed into a savannah. And they now say about 21-22% of the forest is felled; so we're very close to the tipping point.

BASCOMB: You know to build a mine, of course, it's not an isolated structure; they will need roads to get to the mines, and that of course means opening up the forest to other activities. There's the famous "fish bone" effect, you know, so if you look from above, and you look down, there's the main road that's been built, maybe it's paved. And then off of that there's all these tributaries of informal roads that farmers, agriculturalists, other miners and things will use. How big of a concern is that do you think?

BRANFORD: That's a very big concern. I remember when they were building the BR-163 Highway, which went from Cuiabá to Santarém, a port on the Amazon, they promised that they would control the influx of population, that there would be none of these lateral roads built off the main highway. And they made a series of projections about what they thought the environmental damage would be. And 10 years later, the damage was off the scale, it was much worse than their worst projection made at the time. It is very difficult to control influx of population once you've got some kind of road, whether that be a highway to join up two cities or whether it be an access road for a big mine. People do move in and there is land hunger still in Brazil, because quite a lot of land is in the hands of the big farmers. There's thousands of landless peasants who see the only way forward, the only way to earn their living, is by occupying a plot of land, so they move in whenever they can, and one can understand why they do it. And this is likely to be more serious now, it's already getting more serious in the Amazon, because Bolsonaro is not controlling the influx of population. He has dismantled FUNAI, the indigenous agency; he's in the process of dismantling IBAMA, the environmental agency. So loggers and small-time miners, they can all move into indigenous land, and the Indians are very much on their own; there's really no institutional forces they can turn to have these invaders evicted from their lands, and so there's been a considerable increase of violence in these areas now.

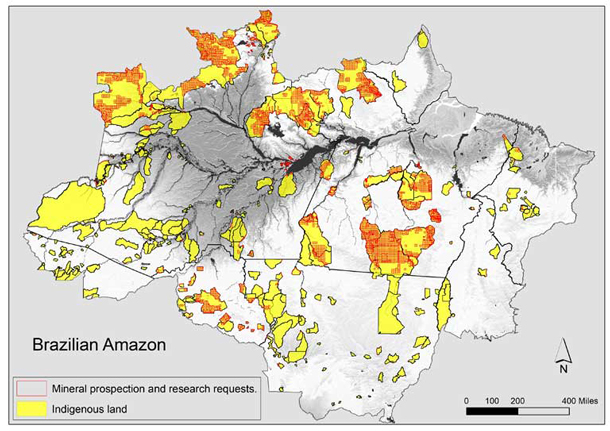

Mining industry and individual prospecting requests on indigenous land as filed with the federal government. (Map by Mauricio Torres with Mongabay, using data provided by the Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral.)

BASCOMB: Can you give me an example, maybe from the bad old days during the military dictatorship, and how mining or this type of development on indigenous lands impacted indigenous people? So, what are these indigenous tribes looking at from their own past to inform them today about making decisions about how to move forward?

BRANFORD: Well I think the project that the Indians talk about most is the big Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River, which is the second largest hydroelectric power station in the world. And the government made a lot of promises to the Indians whose lives have been seriously disrupted by this dam, that they would give them land, they would give them money, they would make sure their lives weren't disrupted. And the government has in fact, given the Indians some money, but a lot of delegations of indigenous people have visited Belo Monte and have come back horrified at what's happening to indigenous culture. Because these people, a lot of their land has been taken away, they haven't got enough space to hunt or even to cultivate crops. So they're basically sitting in villages, getting handouts, food baskets, from the authorities, and their culture is being decimated. And I've heard a lot of Indians say that they can scarcely believe it, the Indians in these villages now have high levels of diabetes, they have strokes, they have all these diseases of the Western world, which many people think come from the food we eat, and that Indians have never had in the past. And it's made them feel they should not really believe the government if the authorities come with promises about the money they will get and all the advantages that will come from these big mining projects. And I think there's nothing like going to an area and seeing the impact of a project to make communities aware of just what could happen to them, what the risk is for them.

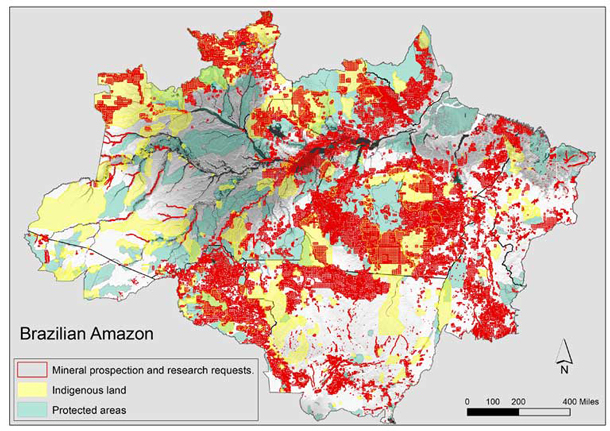

The mining industry has not only made prospecting requests (red) within indigenous reserves (yellow), but also on other conserved lands (green). (Map by Mauricio Torres with Mongabay, using data provided by the Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral.)

BASCOMB: Now, this will have to go through the courts, I believe; what should we be looking for there? How likely is this to get the green light in the courts in Brazil?

BRANFORD: Well, this is an interesting development because the judges, the judicial system in Brazil, which is widely regarded as reactionary, conservative, is actually taking the forefront now in organizing opposition to Bolsonaro. So we've got the General Prosecutor Raquel Dodge, who is the most powerful prosecutor in the country saying, hang on Bolsonaro, we're going to fight this in the courts, we're not going to let you ride roughshod over our Constitution. And there's also the Public Federal Ministry, which is a sort of special bit of the judiciary, which not many countries have, which is not actually part of the official judiciary. It's a kind of independent group of lawyers and they are now saying that they're going to be supporting the Indians and doing everything they can to stop mining happening on their land. So we will see opposition and it will come rather surprisingly, I think, mainly from the judicial system who is not at all intimidated by Bolsonaro.

To begin strip mining, it is necessary to remove all forest and topsoil on site. (Photo: Norsk Hydro ASA, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Sue Branford is a freelance journalist based in London who writes for Mongabay. Sue, thanks for taking this time with me.

BRANFORD: Thank you.

Related links:

- Mongabay | “Brazil to open indigenous reserves to mining without indigenous consent”

- English translation of the Brazilian Constitution

[MUSIC: Arrabona Strings (Balázs Szabó & Péter Kapitár), “The Whistle” by Balázs Szabó, Music&video edited by Gábor Fülöp & Péter Kapitár]

Beyond the Headlines

Kale is a new arrival on the “Dirty Dozen” list of produce with high pesticide levels compiled by the Environmental Working Group. (Photo: Dwight Sipler, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter’s an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and daily climate.org. And he's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia, at least I think so. Hey, Peter, are you there?

DYKSTRA: How you doing, Steve? We're going to talk a little bit about the Environmental Working Groups annual dirty dozen list of produce that has some pesticide risk. They have usual suspects on the list each year like strawberries and apples and spinach, but there's a new extremely trendy newcomer that's in there; kale.

CURWOOD: Oh, Peter say it's not so! I just had a kale bowl.

DYKSTRA: At least you didn't have a kale burger. I don't know if that exists yet. But kale is often grown with use of chemical called DCPA. It's also known as Dacthal. Dacthal was in 2009 prohibited from all uses in the European Union as early as 1995. The US EPA identified Dacthal as a possible carcinogen, and it's still used on a number of food crops, not just kale! But, broccoli, sweet potatoes, eggplant, and something I tend to avoid; turnips.

CURWOOD: Hmm, so what's to be done?

DYKSTRA: Rinse your kale well. Rinse the other vegetables in the list well. And I want to apologize because I know somewhere out there among the Living on Earth listenership somebody just had a sip of a kale smoothie, and it probably didn't go down very well.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: You know, those whiplash, lawyer TV ads that look for victims of car wrecks or defective consumer products?

CURWOOD: Oh, yeah.

DYKSTRA: At EHN we found the piece last week on a Canadian study that found traces of glyphosate in 98% of the samples of Canadian honey. Glyphosate is another whiplash lawyer specialty lately; those commercials are starting to show up. There was a second study that found glyphosate residue and 27% of the honey in Hawaiian hives say that quick three times honey in Hawaiian hives.

Glyphosate was found in 98% of Canadian Honey in a recent study (Photo: Photo: Unsplash, Courtesy of Danika Perkinson)

CURWOOD: So, why are lawyers so interested in this?

DYKSTRA: There are a number of cases in litigation right now and they're inspired by an immense award by a jury to a man who said he was a victim of glyphosate. He was a groundskeeper who regularly used the herbicide in his landscaping work. The jury found that that was a cause of his Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. The initial award was about a quarter of a billion dollars- the court later reduced that to a mere 10s of millions of dollars but still that's catnip to trial lawyers.

CURWOOD: Indeed, hey what do you have from the history of vaults for us?

DYKSTRA: 30 years ago, some NOAA scientists presented on plastics in the ocean. It reported on growing amounts of plastic waste in the Pacific, something we now know 30 years later as the great pacific garbage patch.

CURWOOD: Hmm. So, it seems to be more and more of the stuff. What's to be done?

DYKSTRA: Well, that first report dealt with plastic waste in the Pacific. Today, we call it the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. There are a lot of one-off efforts underway to ban single use plastics, or grocery bags, or straws. But the problem is immense. We're finding plastics not just in the Pacific, but in every ocean of the world, including the Arctic, freshwater rivers and streams, including the Great Lakes. And here's a kind of a tragic Guinness Book of World Records type of thing that I read this past week. In the Philippines, there was a carcass of a beaked whale. A beaked whale is kind of a large size dolphin. It was found on a Philippines beach, they did a necropsy, they cut the beaked whale open, and they found 88 pounds of plastic, mostly plastic bags.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org, and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories at our website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Working Group | “EWG’s 2019 Shopper’s Guide to Pesticides in Produce”

- Environmental Health News | “Weed Killer Residues Found in 98 Percent of Canadian Honey Samples”

- “The Quantitative Distribution and Characteristics of Neuston Plastic in the North Pacific Ocean”

- Live Science | "Dead Whale Washes Ashore with Shocking 88 lbs. of Plastic in Its Stomach”

[MUSIC: Simon & Garfunkel, “Mrs. Robinson” on The Best Of Simon & Garfunkel, Columbia / Legacy]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A Nebraska native looks back at her childhood home. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth. Stay Tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Elaine LaZizza Cronin, “The Water Is Wide,” Folk Salad, Traditional American, Off the Record Recordings]

Losing Ground: Midwest Floods Rip Away Topsoil

The Nebraska National Guard airdrop bales of hay to cattle who have been isolated by the floods across the Midwest. (Photo: Spc. Lisa Crawford, Nebraska National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

The Midwest remains in a state of emergency with record flooding along the Missouri and Mississippi River basins. And for folks in Eastern Nebraska and other parts of the Corn Belt, the road to recovery will be especially hard. Climate disruption will continue to boost extreme weather events and much of the very soil that crops depend on has been swept away. The deep rich soils of the Great Plains helped make this land the breadbasket of the world. Now so much soil has been washed away in the floods that it could take years in some places before farmers can harvest those fields again even with the help of expensive fertilizers. And as if that weren’t enough growers have already lost income in the trade war with China, and flooding contaminated the grain some farmer had stored from last year, waiting for better market prices. Brian Kahn is a senior reporter for the Gizmodo website Earther and wrote about the lasting impact these floods will have on Midwestern farmers. Brian, welcome to Living on Earth!

KAHN: Thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: So what's going on?

KAHN: Well, these floods were a little bit different than the positive floods you can have, in part because they were so severe and extreme. When you have these smaller floods, sometimes they can wash that sediment in; it can be really helpful and beneficial for the soil. But what happened with these floods was something that was extremely different than that, for a number of factors. You gotta sort of go back a few months to actually understand what really happened, which is that it was an incredibly wet, cold winter in Nebraska. They had piles and piles of snow that had already actually fallen on top of tons and tons of rain that fell in the fall. So you had this really saturated soil, this thick layer of snow, and then you had, all of a sudden, this huge influx of rain a few weeks ago. When you get that rain falling on the snow, it melted it all off, and the soil was too saturated, so there was nowhere for it to go. And that's how we ended up with a massive amount of water basically scouring these fields. So instead of depositing nutrients, it basically ripped the nutrients out of the soil.

The Platte, Missouri, and Elkhorn are just some of the rivers that have been flooded in American Midwest after intense winter storms. The image on the right shows the affected area in March 2018, the image on the left shows the affected area in March 2019. (Photo: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And so of course there's a levee system now, so once the soil in the water, instead of getting spread out further downstream it gets channeled in these levees, huh?

KAHN: Yeah, I can get channeled in levees; you know, many of those levees also weren't even able to hold back the river. So you're having these big influxes of water actually be released from dams and levees that actually end up washing away more soil.

CURWOOD: By the way, Brian, remind us, just what is soil, as opposed to dirt.

KAHN: So soil is basically -- I mean, it's the building block of life. There's a reason the Midwest is the spot where we grow everything, it's because it's this incredibly dense, nutrient rich soil that allows all sorts of things that we rely on to eat, to grow. So that's why the Midwest is really this breadbasket of not just the U.S., but the world, because it has this soil that goes feet deep. And that is super dense in nutrients, and that allows plants to grow.

CURWOOD: So what are the options for flooded out farmers once the water recedes?

KAHN: I mean, frankly, none of the options are good. The first is to, you know, wait for the waters to recede, and see what that damage looks like. For fields that have been hit with just, you know, a little bit of flooding, and maybe a little bit of sediment and sandy soil, that can be churned up; it can be turned into, you know, farmable terrain, and they can grow something on that. May not be as big of a crop as last year, but it's something they can do. Another option is to think about soil remediation. So in some cases, we may be looking at sand that's, you know, a foot, two feet thick; this heavy sediment with no real nutrient value, or very little anyways. And in that case, what you're looking at is potentially years of remediation, so planting cover crops, doing things to help restore the structure of the soil that basically lets it hold nutrients again. And those kinds of processes are not short term. I mean, that's a multi-year process in a lot of cases, where you may have fields that just aren't producing anything to eat, or anything of you know, real value for years on end.

CURWOOD: To what extent did farmers lose stored crops that they were hoping to sell later on?

KAHN: I mean, that's happening all over the place; when your silos get filled with water, even the bottom bit, that can you create rot and all sorts of issues. And that's why, you know, when we're talking about what does this flood -- you know, what are the damages, what's the total going to cost? It's why we're not talking about, you know, hundreds of millions of dollars, we're talking about billions of dollars in losses within the agriculture sector, from not being able to plant; from having, you know, stored grain rot out; from having livestock die. I mean, you know, it's gonna reshape people's livelihoods, and it's going to reshape their considerations going forward.

CURWOOD: Now, in the aftermath of these floods, to what extent are some of these farmers going to be out of business?

KAHN: It's very possible that someone could very well declare bankruptcy or just want to walk away, because it comes to the point where their land is not worth the price it takes to grow things and input things, or those years of remediation just aren't worth it to them. And that speaks to a much bigger picture of what's happening, which is that, you know, farm production in certain areas has been declining for years; the tariffs that were recently implemented in the trade war with China by President Trump have also created a situation where you're looking at losses from agriculture. Some of those losses have been sort of met with state programs and with federal programs to help cut some of farmers' losses. But the reality is that those tariffs have, you know, sapped a billion dollars out of the agriculture industry in the Midwest. And so these farmers are already in a tight spot. And now they've been put in a much tighter spot, thanks to these floods.

The Nebraska National Guards airdrops sandbags in an effort to stem the flow of water after a diversion dam breach. (Photo: Army Staff Sgt. Koan Nissen, Nebraska National Guard, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Sounds like the proverbial perfect storm. First, you have, well, fairly expensive fertilizers that you have to deal with, then you have this trade war with China and farmers not being able to sell their crops over the last year or so. And then you have this series of floods that just really wrecks everything from cutting this year's crop to nothing. I wonder if some of the farmers you talk to, if they're feeling like they're facing a plague or something?

KAHN: I mean, in a lot of ways it does, you know, sort of take on that biblical idea of a plague. I mean, it's just; it's wave after wave of things that are hitting them. To me, at least, as a climate reporter, it speaks in a lot of ways to the how climate change is kind of this idea of threat multiplier. You already have these people living in the Midwest that were dealing with, you know, pretty extreme impacts from the federal government pushing down on them; efforts to squeeze more out of their field, the use of fertilizer; I mean, all these different things kind of tugging and pulling at them. And then you have this, you know, final wave of this potentially climate change-induced storm and flood event happening. And that really pushes them over the edge. And so you know, this is a perfect example of, unfortunately, what we might see more as the world warms.

CURWOOD: Yeah, so you write that there certainly is probably a climate aspect to these floods there. So just how does climate change translate into worsening floods along these rivers and in this farmland?

KAHN: So one of the big things about climate change is that it's increasing both the commonness of extreme precipitation and the extremeness of that precipitation. And you know, this is also a basic physics thing at the end of the day, a warmer atmosphere holds more water; eventually, that water is going to fall out of the atmosphere. And so that's why we're seeing this increase in extreme precipitation around the US. And it certainly speaks to, you know, this storm in particular, you think about, sure it was cold in Nebraska, we're still gonna have cold winters. But we also are seeing this increase in rain falling during the winter, all across the country, including a 74% uptick in Nebraska, in terms of, if you look at weather stations around the state, 74% of them are recording more rain than they did even 50 years ago. And so, you know, this is what climate change looks like.

CURWOOD: So as climate driven catastrophes keep happening more and more frequently, people are talking about how important it is to be resilient. So what does resiliency mean for farmers at risk of continually losing their top soil, their stored grain and their livestock to floods?

KAHN: You know, I'd say that resiliency really sort of starts at the top. I mean what we're seeing here is, you know, a river control system that was designed for certain types of floods. And this flood was an outlier, it was extreme. It's kind of like, you look at what happened to New York during Hurricane Sandy. Or you look at what happened in California during the drought. I mean, these are outlier events that become more common. So we don't just need individual farmers to think about resiliency, we need to think about, how does the system itself become resilient? Frankly, there are no easy answers for what that looks like. Do you build more flood control dams? Do you build more levees? Or do you choose more natural solutions, to say, this area is now, you know, a floodplain that we're just going to not, not let anyone build? There are a lot of open questions on that. In terms of farmers and thinking about, you know, what can they do, there's a lot of talk about using cover crops to kind of keep soil locked in place even during the offseason; there are ideas around no-till agriculture, so farmers spend less time actually turning up their soil, and that will help the structure of the soil stay in place, should these heavy rain events occur. But yeah, really, this is like a whole system change that we need to talk about.

CURWOOD: Okay, Brian, I'm sitting down. So you can tell me... how much worse is this year's flood season projected to be like, do you think?

Brian Kahn is a science writer for Earther from Gizmodo Media and lectures at Columbia University. (Photo: Courtesy of Brian Kahn)

KAHN: Well, the damage right now in the upper Midwest alone is looking to be in the billions of dollars; early estimates have it pegged around $3 billion. That number is likely to rise. And there's also the reality that this flood season is not anywhere close to over. Even as the waters are receding in Nebraska and Iowa and that part of the upper Midwest, they're actually still surging downstream towards the Gulf of Mexico. And so you have a situation of flood forecasts for the coming few months through May that shows that there could be up to 200 million Americans at risk of facing floods. So the damages that we're seeing in the Midwest are actually unfortunately the tip of the iceberg of what we may see over the coming months.

CURWOOD: Journalist Brian Kahn lectures in the Climate and Society program at Columbia University. Brian, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

KAHN: Oh, thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Earther | “Farmers in the Midwest Face Decades of Recovery as Flooding Strips Away Crucial Soil”

- Fortune | “Massive Flooding Has Destroyed Midwest U.S. Farms. Here’s What You Should Know”

- CNN | “The Midwest Flooding Has Killed Livestock, Ruined Harvests and Has Farmers Worried for Their Future”

- Visit Brian Kahn’s Website

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: The Rainwater Basin of Nebraska

A hybrid mallard/pintail. (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

BASCOMB: About 200 miles west of the devastating flooding in Nebraska is the Rainwater Basin wetland. It’s 6200 square miles of depressions left by retreating glaciers that fill with rain and snowmelt each spring. As BirdNote’s Michael Stein explains it’s a crucial habitat for migratory waterfowl making their way north this time of year.

[NORTHERN PINTAILS SPLASHING IN WATER]

An adult snow goose (Photo: Gregg Thompson)

STEIN: For 20,000 years, spring rains and melting snow have filled the playas of the Rainwater Basin of south-central Nebraska. Carved by glacial winds at the end of the last Ice Age, the playas are shallow depressions the warmth of spring fills with abundant life.

[RED-WINGED BLACKBIRDS]

STEIN: As winter ends, ten million waterfowl rest and feed here before continuing north.

[CALLS OF NORTHERN PINTAILS, BLUE-WINGED TEAL WITH MALLARDS AND MARSH SOUNDS]

STEIN: The seasonal wetlands of the Rainwater Basin form a 150-mile-wide funnel for water birds migrating from the Gulf Coast and points south to northern breeding grounds. The basin is the narrowest neck of the great migratory route we call the Central Flyway.

[CALLS OF SNOW GEESE]

STEIN: In recent years, the number of Snow Geese stopping in the region during spring has risen dramatically to more than three million birds. A third of North America’s Northern Pintails rely on the food-rich habitat here.

[CALLS OF NORTHERN PINTAILS]

STEIN: Shorebirds of 27 species use the wetlands. So do half a million Sandhill Cranes.

A sandhill crane and her chick (Photo: Larry Crovo, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

[CALLS OF SANDHILL CRANES]

STEIN: The importance of the region’s wetlands for waterfowl cannot be overstated. Fat reserves acquired during their stay here can mean the difference between success and failure in nesting. No other stopover between wintering and nesting grounds can replace the combination of wetlands and grain fields found in the Rainwater Basin.

[CALLS OF SANDHILL CRANES]

STEIN: I’m Michael Stein.

BASCOMB: For photos of the Rainwater Basin’s migrating birds splash on over to our website, LOE dot ORG.

Related links:

- Bird sounds provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York.

- This show on the BirdNote® Website

[MUSIC: Dapp theory “Bird Calls” from Layers Of Choice (Oblique Sound records 2008)]

The Place Where You Live: Chadron, Nebraska

Chadron’s Main Street. The block shown is part of the Chadron Commercial Historic District, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. (Photo: Ammodramus, Wikimedia Commons CC)

CURWOOD: We are going to stay in Nebraska now, for another installment in the occasional Living on Earth/Orion Magazine series “The Place Where You Live.” Orion invites readers to submit essays to the magazine’s website, to put their homes on the map and we give them a voice.

[MUSIC: Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes “Home” from Edward Sharpe and The Magnetic Zeroes, Rough Trade Records, 2009]

CURWOOD: Thoughts of a childhood home inspired today’s essay.

[MUSIC: Gillian Welch, “Revelator,” on Time (The Revelator), composed by David Rawlings/Gillian Welch, Acony Records, 2001]

MCFEE: I think when people normally think of Nebraska they imagine flat fields of corn and dirt roads between them. And Chadron is really close to the border of South Dakota and we have a state park right outside of it, so there were hills and bluffs and pine trees. But everywhere you went you could still see the entire sky above you.

Treed hills near Chadron, Nebraska (Photo: Ben Schmitt, Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0)

I’m Abigail McFee and this is my essay about Chadron, Nebraska.

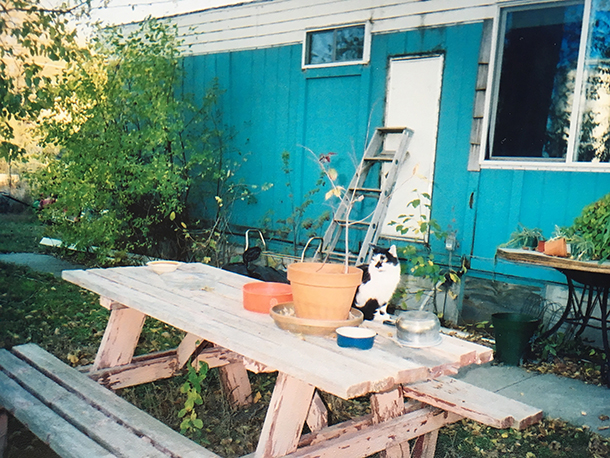

Picture a blue trailer built in the 1970s, with a wide yard on three sides and green linoleum in the kitchen. Place it at the end of a street lined with locust trees. Imagine a square window at the end of the trailer, no more than a foot wide. The curtain is pulled to the side, and at night the warm glow of the kitchen light is always visible through this window.

We moved to the trailer when I was six years old, after my parents separated. When the last of the summer thunderstorms struck, my sister and I lay awake in awe at the sound of rain pounding the thin walls. There was a feeling of confinement to the trailer and also a sense of expansiveness, as if we were closer to the world outside of it.

The town we now lived in had been a trading post on a creek in 1841, managed by French-Indian fur trader Louis Chartran. The creek took his name, which later tongues murmured into “Shattron,” which evolved again before it became recognizable.

Chadron, Nebraska: Part prairie grassland, part forested hills, part sidewalk that pierced my heel with a locust thorn, part trails we wandered at age ten pretending to be lost explorers, part tree near those trails where a math professor was found burned and bound, part steady hum of the wind.

After the trailer was painted tan with white trim, after my mom and sister moved to New Mexico, after my childhood bus driver retired, after forest fires charred 40 square miles of trees and got us onto CNN, I moved into a basement apartment on the corner of 2nd and Bordeaux, named for another French fur trader. That winter, I managed to get three flat tires. That spring, I graduated as high school valedictorian. That summer, a local author published a book about the math professor, who had lived, he wrote, in the basement of a white house on the corner of 2nd and Bordeaux.

I had moved to Boston for school, but the place was still inside me.

[MUSIC: Gillian Welch, “Revelator,” on Time (The Revelator), composed by David Rawlings/Gillian Welch, Acony Records, 2001]

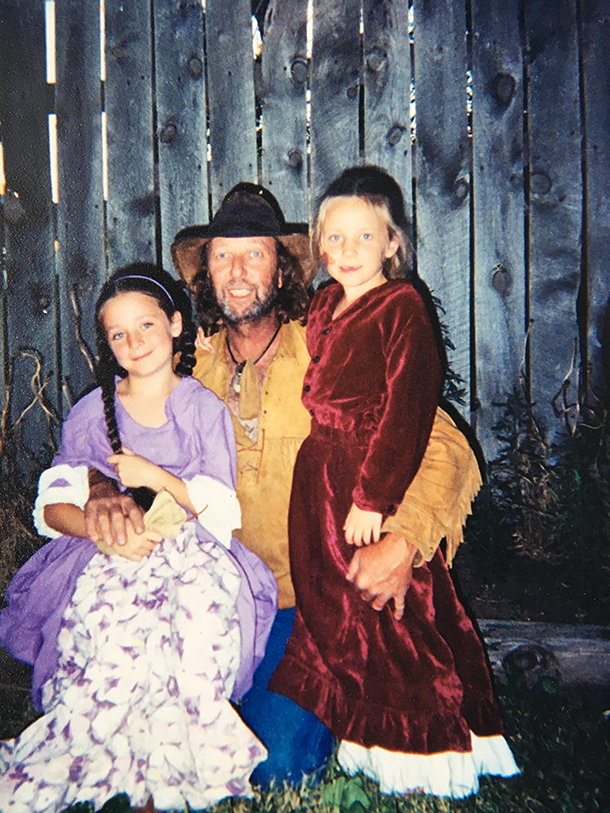

I think Chadron, Nebraska, was my childhood in a sense. It was this place that really got inside of me, where I knew all of the people around me, all of the kids I grew up with. And I had all of these landmarks of memory, which I think is something that is true of almost any childhood. But the interesting thing about living there was that it was rooted in such history. So every summer in the second weekend of July we have a celebration called Fur Trade Days in Chadron and people will dress up in costumes and there’s a buffalo chip throwing contest and everyone eats fried bread. My dad especially would come and visit that weekend. That was his favorite because he was fascinated by the history of the fur trappers, and so he would dress up like a fur trapper and compete in the costume contest. And, you know, I had that, and I had the whispers of Louis Chartran who had been the reason that our town got its name, even though it was through this very warped history. So they were just these people who kind of populated our lives even though they were no longer alive, just as much as the people who we would run into at the grocery store.

The blue trailer where Abigail grew up with her mom and sister (Photo: Abigail McFee)

[MUSIC: Gillian Welch, “Revelator,” on Time (The Revelator), composed by David Rawlings/Gillian Welch, Acony Records, 2001]

And I think I lived there at exactly the right time, where it spoke to all of the questions that I had about the world. It kind of fostered this wildness inside of me that ironically made me want to go elsewhere. But I think a lot about the unobstructed horizon, because it’s not something that I experience as much now that I’m living right outside of a city. But you had the sense that the natural world was really spreading out around you in an endless way. And I do, when I think about it, just have this feeling of warmth because, you know, there was a sense of never really having to hurry. I think most of my memories, it’s like they go on and on, just hours and hours spent in the backyard, playing or running around on trails in the state park.

[MUSIC: Gillian Welch, “Revelator,” on Time (The Revelator), composed by David Rawlings/Gillian Welch, Acony Records, 2001]

When I go back to Chadron, everything about the landscape feels exactly the same to me. A lot of the landmarks that I point to were things that I would’ve taken for granted without having some distance from the town. Even just driving by the turn off on familiar roads or, you know, passing the supermarket that everyone shops in, all of those things seem much more precious when you don’t see them before... it’s almost as if I forgot they could exist without me, but then when I return to this other place where they’ve always existed, it seems completely normal to me and natural that everything would be, you know, so similar to how it was when I left it. And it's almost as if I could just re-enter that world.

Abigail, her sister and their father dressed in costume for Fur Trade Days (Photo: Abigail McFee)

[MUSIC: Gillian Welch, “Revelator,” on Time (The Revelator), composed by David Rawlings/Gillian Welch, Acony Records, 2001]

CURWOOD: That’s Abigail McFee and her essay about Chadron, Nebraska. You can find pictures and details about Orion Magazine and how to submit your essay, if you want to tell us about the place where you live at our website, LOE.org.

Related link:

Abigail McFee's “Chadron, Nebraska” essay on the Orion website

[MUSIC: Snarky Puppy, “Flood” on Tell Your Friends, Ropeadope]

BASCOMB: Coming up- How a 120-acre ranch in the Colorado mountains helped a woman heal from childhood trauma. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: David Grisman Quintet, “Desert Dawg” on Dawgnation, by David Grisman, Acoustic Disc]

Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country

Winters at 9,000 feet in the Colorado Rockies can bring low temperatures of 35 below zero. (Photo: Pam Houston)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Writers have often sought refuge in nature and wilderness. In a vast desert or forest, or looking down at the landscape from a mountain peak, trauma and heartbreak can seem so much more distant, and the burdens of the past easier to carry. For writer Pam Houston salvation came in the form of a 120-acre ranch high in the mountains of Colorado. In her 2019 book “Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country” she chronicles 25 years of winters that bring temperatures as low as 35 below, and smoky summers that threatened her ranch with wildfire. Pam has lived through a lot with the land. And she writes about how the place has gradually helped her heal from childhood sexual abuse she experienced at the hands of her father. Pam Houston joins me now. Welcome to Living on Earth!

HOUSTON: Thank you very much!

BASCOMB: So Pam, first of all, tell me about the ranch that's the focus of your memoir, Deep Creek. How did you find the place nearly 25 years ago, and why did you decide to call that home?

“Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country” is Pam Houston’s first memoir. (Photo: W.W. Norton)

HOUSTON: Well, the ranch is 120 acres in a high mountain meadow at 9000 feet. It's got 13,000-foot mountains on all sides of it; fur and spruce forest and aspen. And I went looking for a place to begin with, because I sold a book of short stories, my first book, when I was still in graduate school, and when I got the check for $21,000, my agent said, Don't spend it all on hiking boots. And that seemed like good solid parenting advice. And so I went driving all over the West looking for a place and I got to Creede, Colorado, which was just the next place on the list. A writer friend of mine, Robert Boswell, had said, check out Creede, I heard it's cool. I got there and looked around at some houses and finally got taken out to this ranch, this 120-acre ranch. And it was the third week of September, and if you can't fall in love with Colorado in the third week of September, you can't fall in love. Because the aspens are changing in giant, undulating swaths of Tequila Sunrise colors all over the hillsides, and the sky is blue and the air is crisp. And here was this place, with this hundred-year-old barn with a big beautiful mountain behind it. And my $21,000 represented 5% down on that place. And the realtor said, You know, I think the widow Blair -- who was selling it -- I think the widow Blair is going to like the idea of you. And if you give me your 5% down and a signed hardcover of Cowboys Are My Weakness, I'll see what I can do.

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Now, the third week in September sounds stunning. But then winter comes --

HOUSTON: [LAUGHS] Right?

BASCOMB: -- and winter at 9000 feet is not for the faint of heart, the way you describe it in your book. You describe a scene where you have a really legitimate concern that you might actually get lost in a blizzard between your house and your barn. Tell me what it's like to live there in the winter, and, you know, how you overcame that?

HOUSTON: Well, it is possible; we can get as much as four inches of snow an hour, the record is 76 inches in 24 hours. There are days when the winds are so high and the snow is so thick that I can shovel my way to the barn and get everybody fed, get everybody hay, get everybody water, get everybody their grain. And sometimes my path to the barn is obliterated by the time I do 25 minutes of chores.

A 100-year-old barn lends character to the ranch and keeps the horses, donkeys, and Icelandic sheep warm. (Photo: Pam Houston)

BASCOMB: Wow. So what does it entail to own a ranch at 9000 feet in the Rocky Mountains? I mean, this sounds like really hard work.

HOUSTON: Well, um, kind of the biggest thing is the weather. We have drought, we have fire, we have flood, we have blizzard. And then we have so many days that are just so spectacularly beautiful, they make your heart sing. It's a lot about protecting everything from the UV rays, which at 9000 feet are super intense. So if I don't put UV protector all over everything-- house, barn, shop, cabin -- once a year, the sun literally eats the logs away. It's about having backup plans; you know, when the power goes out, I have a good wood stove so I can keep the house warm, even if we lose power and my furnace goes out. It's about having water on hand in case the power goes out, because then the pump fails. You know, it was an amazing learning curve. Because when I came out West and bought the place, I mean, I didn't even know hot water didn't come out of the wall, you know, when you turn the tap on. So it was a lot of learning, a lot of listening to my neighbors, a lot of asking for and accepting help. When I got there, I said, my tasks fell into two categories: the things I didn't know how to do, and the things I didn't even know I didn't know how to do. But somebody would come by and say, when was the last time you protected your logs with that UV protector? And I'd be like, okay, [LAUGHS] UV protector. When was the last time you swept your chimney? So I bought brushes to sweep my chimney. It was 25 years and counting of learning.

BASCOMB: Now, your memoir is really focused on how much the ranch helped you to heal from the traumas of your childhood -- emotional abuse from your mother and sexual abuse from your father. In what ways has your ranch and nature helped you to heal, and why, do you think?

A “spirited troupe” of horses, donkeys, Icelandic sheep, Irish wolfhounds, a cat, and chickens keep Houston busy on the ranch. (Photo: Pam Houston)

HOUSTON: Well, I was born to two people who, who didn't want to be parents. And I think for some of my life, I thought that was really sad. [LAUGHS] And because I've been a writing teacher for 20 years, I have come to understand that there are many, many things that are sadder than that. But as I wrote the book, and as I talked about my relationship with the ranch and thought about it, and did the kind of deep emotional work one has to do to write a memoir, I really came to understand that my parents' lack of parenting turned me to nature, to look for sustenance and healing and succor, basically. I grew up in an alcoholic home, I grew up in a violent home, my father broke my femur when I was four years old. And I thought he would kill me, most of my life -- most of my young life. But what I did is I went and walked the railroad tracks, or I went and played horses in the woods -- which, meaning, I was the horse, [LAUGHS] running through the woods, and leaping over logs, and hitting myself with my own little crop [LAUGHS] that I broke off a tree branch. And, you know, from the very, very beginning, nature was the place I went to feel better. And when I got into the relationship with the ranch 25 years ago, my idea was to protect it, to save it, to take care of it the way it had taken care of me all my young life. And then, of course, it turned out that learning how to make that commitment and learning how to be responsible to something over a quarter of a century and learning its foibles, and its fragilities, you know, as well as its strengths and its power, gave as much to me as I gave to it. You know, in the end, yeah, I didn't have that kind of nurturing or support as a kid. But I found a way to get in relationship with something else, which at first was just the natural world around me in the places I grew up, but in my later life has become this big, long love affair with this 120 acres.

Pam Houston fell in love with the 120-acre property in 1993 and purchased it with just 5% down – all of the $21,000 advance she received for her first book. (Photo: Pam Houston)

BASCOMB: Now, what kinds of climate change impacts are you seeing on your ranch these days, if any?

HOUSTON: A lot. I'm seeing a lot of impacts. I know that probably the records would disagree with me, would say that this is an exaggeration, but it feels to me like it's about 10 degrees hotter all the time. It's, in the summertime we never used to hit 80. And now we have weeks of 86, 87. In the winter time, we would always see 35 below, that was always the mark that you'd gotten to the coldest point of the winter, you know, sometimes it would be 38 below zero, this is. Now, the coldest temperatures are like 25 below and --

BASCOMB: It's a heat wave! [LAUGHS]

HOUSTON: [LAUGHS] That might not sound like a big difference. And it might even sound like a like a good thing. But it's hard on the ecosystem. The beetles that are eating the trees in the West are related to the fact that we don't get that severe, severe cold anymore. And of course that's related to fire. Obviously, we're seeing fires all over the West, but also at the ranch, that are fires on steroids. Because the beetle kill has killed so many trees, the temperatures are hotter, we're seeing less moisture. And that all combines to make these giant fires. And we had a fire in 2013, the West Fork Fire, which burned within a half a mile of the ranch, it burned 110,000 acres and burned for weeks and weeks.

Beetle-killed forest in Colorado. Spruce bark beetles and drought have contributed to an increase in wildfires in the state in recent decades. (Photo: Hustvedt, Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 3.0)

BASCOMB: Yeah, you describe the fire in just painstaking detail in your book, but your ranch ultimately was spared. Why do you think that is?

HOUSTON: Well, all of our ranches were spared because we had the most amazing firefighters imaginable. At one point, the firefighters in our county outnumbered the residents by 3 to 1.

BASCOMB: Wow.

HOUSTON: We had literally thousands of firefighters saving our properties. My ranch was never evacuated, unlike many, many, many of my neighbors. And one thing I learned during that fire is that meadows really stop fires, and I was never evacuated because, I believe, the firefighters felt that I have a big meadow protecting me. And then I also have a stand of aspen at the back of my property, which is where the fire would have come from. And those aspen trees hold a lot of water in their trunks, and aspen trees will turn a fire as long as there are firefighters there to help them, you know, to help them turn it. So, I actually learned over the course of this terrifying weeks of seeing 200-foot flames shooting from the trees out my bedroom window, that I'm actually a little safer on my very ranch than some other people. Also, now that we've burned -- the forest burned in a literal horseshoe around my property. So, you know, we're probably okay now. But that sounds like a very selfish thing to say, as I hear it to my ears. I mean, the West is going to be dealing with fire as far forward as we can see, because of continuous drying, warmer temperatures and the beetle kill, which are all either directly or tangentially related to climate change.

BASCOMB: Your book's subtitle is Finding Hope in the High Country. For me and I suspect a lot of regular listeners to Living on Earth, hope may be hard to come by when each week we talked about the unfolding environmental disasters all around us. How do you personally continue to find hope?

Pam Houston writes about an incredible experience in the Arctic of stumbling upon the migration of about 800 narwhal, small whales that have a long tooth sticking out the front of their head like a unicorn horn. (Photo: Dr. Kristin Laidre, Polar Science Center, UW NOAA/OAR/OER, Wikimedia Commons)

HOUSTON: Well, I think the challenge right now, isn't about looking for any kind of hope that would fall into the naive category, I think we're in trouble and we know it and that's the reality. But I also think that probably being an adult means being able to hold the hope and hold the sadness and the sorrow about this climate catastrophe together. I was up in the eastern Canadian Arctic and two days in a row just showed me this so clearly. The first day, we completely against all odds, once in 10 lifetimes experience, we got into the annual narwhal migration in our boat. So, we're in a boat and we're running with 800 narwhals you know, which most people never get to see in their lifetime.

BASCOMB: Wow, that must have been amazing. I mean, narwhal, for people that are not familiar, they're a whale with a giant spike off their head, sort of like a unicorn or something, that they use to poke through the ice. Is that right?

HOUSTON: That's right. It's actually a tooth. But yes, it looks like a spike. And it's a tooth that grows forward out of their mouth and out into the front of them, like a unicorn horn. They believe they're the original unicorn myth. And it was the most staggeringly amazing thing, you know, in a life of amazing outdoor experiences, it might be number one for me. But at the same time watching those narwhals was the knowledge that probably even more than the polar bear the narwhal are threatened by the melting sea ice because they need the sea ice to hunt. And then the very next day a little further down the coast of Baffin Island, we saw this blue thing out in the distance. And you know, we're like, what is that? Is that an island? Where are we? And it turned out to be a five mile by five-mile chunk of ice. And it was staggeringly beautiful, it was made of crystal blue glass, and it had giant rivers pouring off of it in these sort of porcelain white blue pour-overs. And, you know, it was bigger than we could see around from our boat, and just this gleaming thing in the sun. And of course, it was the piece of the Greenland ice shelf that had fallen off in 2012, and it was still floating out there. So, you know, never was there a more beautiful object, and never was there more evidence of the trouble we're in. There it was, you know, all together. And, and I see, I see versions of that every single day. And, you know, I think one of our troubles right now in this country, is it like, is it this or this? Are they with us or against us? Is it us or them, you know. And it seems like, you know, "and" is the operative conjunction. Like, yeah, it's, it's magnificent, the earth is magnificent -- and it's in dire trouble because of us. And that's a hard truth. But I don't think we can lose either of those. I don't think we can lose the joy at the wild things we still get to experience, so that we might fight for its life.

Pam Houston and her horse, Roany. (Photo: Mike Blakeman)

BASCOMB: Pam Houston is author of Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country. Pam, thanks for taking this time with me.

HOUSTON: Oh, you're welcome. It was my pleasure.

Related links:

- “Deep Creek: Finding Hope in the High Country”

- About author Pam Houston

- Outside Online | “Pam Houston’s ‘Deep Creek’ Is (Of Course) Fantastic”

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Peace” on Spirit, by Horace Parlan, Jazz Legacy Productions]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Delilah Bethel, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Adelaide Chen, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes.

Our Executive Producer is Steve Curwood. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth