August 30, 2019

Air Date: August 30, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Saltwater Beavers Bring Life Back to Estuaries

View the page for this story

Until recently, biologists assumed that beavers occupied freshwater ecosystems only. But scientists are now studying beavers living in brackish water and how they help restore degraded estuaries and provide crucial habitat for salmon, waterfowl, and many other species. Journalist Ben Goldfarb speaks with Bobby Bascomb. (09:42)

Everglades National Park, a “River of Grass”

/ Lizz MalloyView the page for this story

Established as a national park in 1934 and a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1979, Everglades National Park is much more than a mere swamp. Only an hour’s drive west from bustling Miami, the 1.5 million acres of the Everglades provides a place of sanctuary in nature for those looking for peace and quiet, as well as a front-row-seat view of wildlife from anhingas to alligators. Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy went to check out the “River of Grass.” (07:32)

Drilling in the Everglades

View the page for this story

The unprotected parts of the Everglades region are open to development, including oil drilling. The Kanter Real Estate group recently won approval to drill an exploratory well in the Everglades ecosystem after a legal battle that started in 2015. Miami Herald Reporter Samantha Gross joins Bobby Bascomb to talk about the ruling. (05:35)

Fly-fishing Saved From Pollution

/ Julie GrantView the page for this story

The trout in Central Pennsylvania’s waterways face pollution from agriculture and development. But as Allegheny Front Reporter Julie Grant explains, this area still has some great fly-fishing, and passionate, local conservationists are working to keep it that way. (04:38)

Gaza Water Crisis

/ Sandy TolanView the page for this story

In the Mideast’s hotly contested Gaza Strip, where three out of four people are refugees, access to electricity and clean water is severely limited. The unsafe drinking water has led to a worsening health crisis for Gaza’s children, who suffer from diarrhea, kidney disease, stunted growth and impaired IQ. The problems include the lack of electricity to run Gaza’s sewage treatment plant, and the long-running conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. Sandy Tolan reports from the Gaza Strip. (18:36)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Ben Goldfarb, Samantha Gross

REPORTERS: Lizz Malloy, Julie Grant, Sandy Tolan

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRI – this is an encore edition of Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Scientists discover a previously overlooked habitat for the busy beaver.

GOLDFARB: They're not only using saltwater to disperse, they're actually living full-time in these intertidal estuaries, and are actually doing all kinds of really interesting engineering and architecture, and are playing this really important ecological role in saltwater ecosystems.

BASCOMB: Also, a visit to South Florida and the famous River of Grass.

KOMINOSKI: Why people should appreciate and visit the Everglades is because of its size. It's one of the few large open wilderness areas of the east. It is a place of subtle beauty, that I think many of us have forgotten how to appreciate.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, it’s an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb in for Steve Curwood.

Saltwater Beavers Bring Life Back to Estuaries

Because they build dams that shape the very environments in which they live, beavers are a classic example of a “keystone species”. (Photo: Becky Matsubara, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: The eager beaver is an extremely effective engineer of its environment. Beaver dams hold back water that can be a nuisance to homeowners, but they create a complex system of ponds and wetlands that are a haven for numerous plant and animal species.

[SFX WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: On a recent winter morning I went to look for the tell tale signs of the iron toothed rodents at a pond near my home in New Hampshire. I enlisted the help of my 4 year old daughter, Sage, to find, as she calls them, beaver trees.

SAGE: 1,2,3,4,5 a beaver tree.

BASCOMB: A thin layer of ice blankets the network of ponds, streams, and wetlands in the frigid woods.

SAGE: I found a beaver tree!

BASCOMB: How do you know that’s a beaver tree?

SAGE: Because it chewed all the way down. Ok, let’s keep going to see more.

BASCOMB: Well, we found our “beaver trees” right where you might expect: near a freshwater pond. But scientists recently discovered that beavers are also happy to live in the brackish mix of fresh and salt water in coastal areas. And just as they help restore freshwater ecosystems, beavers could also hold the key to restoring damaged coastal wetlands. Journalist Ben Goldfarb wrote about saltwater beavers for Hakai Magazine, and he joins me now. Ben, welcome back to Living on Earth!

David Bailey, a biologist with the Tulalip Tribes, stands next to a beaver dam exposed at low tide on the Snohomish River in Washington State. (Photo: Ben Goldfarb)

GOLDFARB: Thanks for having me again.

BASCOMB: So first, Ben, how surprised were you to find out that there are saltwater beavers? I mean, you're a self described beaver believer. You wear beaver t-shirts, you wrote a book about beavers, I mean, you know a thing or two about beavers. How surprising was this?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, it was definitely surprising. I think that I and, you know, and all beaver biologists knew that beavers occasionally would swim into saltwater, you know, they dispersed from the mainland to islands in some places. Sometimes they'll go out to the mouth of the river, hang a right up the coastline and travel up aways looking for the next river mouth to go up into. But I think it's just really within the last several years, thanks in large part to this guy, Greg Hood, a scientist who works in the Skagit river in Washington, that we've begun to understand that they're not only using saltwater to disperse. They're actually living full-time in these intertidal estuaries and are actually doing all kinds of really interesting engineering and architecture and are playing this really important ecological role in saltwater ecosystems.

BASCOMB: You actually went to visit one of those beaver lodges on this Snohomish river in Puget Sound. Can you describe that? What was it like there?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, it's a really amazing place. So it's basically this kind of vast intertidal estuary and the beavers are building in these kinds of tidal channels. So there are basically, it's kind of this huge salt marsh that's scored with these little freshwater channels that fresh water comes down in. But then when the tide comes up twice a day, those fresh water channels are completely submerged, they're inundated. So it's this really dynamic ecosystem with the tides are just going in and out all the time. And beavers are actually building in there. So they'll build these dams that when the tide comes up, the dams are actually completely submerged under water, you could kayak over the top of one of these dams and have no idea that they were beavers building there. And then when the tide goes out again those dams suddenly reemerge, essentially, and now they're holding back these pools of water in these intertidal channels, so it's almost like the beavers are anticipating these tidal fluctuations and are accounting for them in their construction, and in this really sophisticated way.

BASCOMB: Wow, that is sophisticated. I mean, that's Army Corps of Engineers-level engineering, I think.

GOLDFARB: Totally, except better for the environment than the Army Corps, you might argue [LAUGHS].

BASCOMB: [LAUGHS] Yeah. So you got there and you found this extraordinary feat of engineering, really, by these beavers. And how do their dams in these intertidal areas affect the ecosystem around them? What kind of habitat are they creating?

The sediment-rich waters of the Elwha River flow out into Washington State’s Strait of Juan de Fuca. The removal of two dams on the Elwha River from 2011 to 2014 restored sediment flow in this important salmon-bearing river. (Photo: John Felis, USGS, Public domain)

GOLDFARB: Yeah, that's a great question. So most of what we know about how important these habitats are comes from Greg Hood, who did a lot of intertidal beaver research on the Skagit River, which is another river in Washington where beavers sort of occupy these intertidal areas. And basically what Greg found is that these are enormously important, these beaver construction sites, are hugely important for juvenile salmon, especially. You know when the tide goes out, those fish would get flushed out into these estuaries where they're really at risk of being preyed upon by larger fish, by birds. That's a pretty challenging habitat to be a little finger-length salmon in. But at low tide because beavers are holding back these deep pools of water they're creating these fantastic refuges essentially for juvenile salmon, that are deep enough that birds like great blue herons can't really get in there to prey on the juvenile salmon. So it turns out, Greg discovered, that baby salmon were three times more abundant in these beaver pools than in other habitat. So clearly they're just creating these fantastic salmon refuges, which is something that we knew that beavers did in fresh water. But we didn't realize until Greg's research a few years ago that they were also playing this same role of creating these salmon refuges in the estuaries as well.

BASCOMB: Wow. So, they really serve a critical function. I mean, everybody likes salmon, right? The bears, the whales, people. Everybody likes salmon, and they're in sharp decline; I mean, could beavers be something of a game changer for salmon habitat, for helping the salmon rebound?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, and I think that again, in freshwater streams, you know, beavers are already being considered this crucial keystone species for salmon recovery. There are so many beaver restoration efforts here in the Pacific Northwest where I live aimed at getting beavers back in these streams and basically creating salmon habitat. There are so many scientific studies that have been published basically showing that beavers dramatically help the survival of juvenile salmon. So that sort of pro-beaver work is already happening in much of the Northwest. You know, a lot of it's catalyzed -- we, you know we saw this past year just how badly the Southern Resident killer whales are doing, the orcas in Puget Sound, and they're essentially starving because there's just not enough salmon for them to eat. And there's this renewed focus I think on creating salmon habitat to feed both the whales and of course ourselves, and beavers are a part of that solution and it might turn out that estuary beavers are a part of the solution as well.

BASCOMB: Wow. So help the beavers, help the whales?

GOLDFARB: Exactly, yeah. By helping the salmon.

BASCOMB: By helping the salmon, it's all connected. Now, you write about how beaver ponds can help restore degraded coastal wetlands. And there's clear evidence for that in removal of dams on the Elwha River in Washington State. Can you tell me about that, please?

GOLDFARB: Yeah, so the Elwha is a fascinating story. So the Elwha's a river on the Olympic Peninsula. And these two enormous dams had basically been there since the 20s I think, just trapping enormous amounts of sediment and blocking salmon runs. It was sort of this environmental disaster. And, you know, a few years ago the government actually bought those dams and -- thanks to pressure from native tribes -- and removed the dams, and opened up this huge amount of spawning habitat for salmon, so now salmon are swimming up river, past the former dam sites. But the kind of, the amazing outcome for beavers was that by breaching those dams we essentially unlocked this huge pulse of sediment, that had been trapped in the reservoirs and all this sediment just rushed downstream and basically settled at the mouth of the Elwha River. The river mouth had been starved of sediment for so long that it basically just flowed straight into the ocean. There was no real estuary there. Suddenly there's this huge beach and sandbar complex, about 100 acres of new habitat. And in the course of writing this article, I went out there and walked around on the kind of the Elwha floodplain, essentially, at the mouth of the river. And just everywhere you see cut willow and alder, and cherry; beavers are really going into town in there. And by creating burrows and canals and dams, they're just creating this amazing habitat complexity. They're just opening up lots and lots of little spaces for all kinds of salmon and trout and other fish to live in.

BASCOMB: Now you've written a whole book about how people are increasingly seeing beavers as hydrological saviors in freshwater ecosystems. What do you think it will take for them to gain that same recognition in their coastal contributions?

The mouths of the Elwha, Snohomish, and Skagit Rivers in Washington State provide important saltwater habitat for beavers, salmon, and many other estuarine species. (Photo: Illustration by Mark Garrison)

GOLDFARB: Yeah, that's a good question. I think that part of the issue is that we've lost so much of this coastal habitat here in Washington. These intertidal ecosystems are some of the first places that when colonists arrived, those habitats were essentially drained and converted into farmland, and we've lost about 95% of these kind of intertidal shrub lands where beavers are so important. So I think that the first thing that has to happen is just a broader recognition of the, kind of the historical role of these intertidal ecosystems in producing salmon. And then once we've acknowledged that this habitat is so vital, then we can sort of start talking about how important beavers are there. Most of this research is sort of focused on beavers' role in tidal ecosystems in Western Washington, but are they playing a similar role in salt marshes in New England, or in the Carolinas, where beavers are really abundant, and where there are lots of salt marshes? We've lost so much of this intertidal habitat and we've lost so many beavers that, I think we've really lost a lot of these ecological linkages.

BASCOMB: Ben Goldfarb is author of the book "Eager: The Surprising, Secret Lives of Beavers and Why They Matter." He wrote about saltwater beavers for Hakai Magazine. Thanks for taking the time with me, Ben.

GOLDFARB: Thanks again for having me back.

Related links:

- Ben Goldfarb for Hakai Magazine | “The Gnawing Question of Saltwater Beavers”

- A previous Living on Earth interview about beavers with Ben Goldfarb

MUSIC: Nino Rota/conducted by Franco Ferrarra, “La bella malinconica” on Arrivederci Italy, by Nino Rota, Sony Music

BASCOMB: Coming up, a visit to the river of grass, Florida’s Everglades National Park. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: If you like what you hear on Living on Earth, please join us with a gift of five dollars or more. Just go to loe.org, and click on "Donate" at the top of the page. And thank you.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Rick Braun, “Coolsville” Body & Soul 2010 Mesa/Bluemoon Recordings, Inc.]

BASCOMB: It's Living on Earth. I'm Bobby Bascomb.

Everglades National Park, a “River of Grass”

The Everglades National Park provides visitors with a variety of beautiful vistas. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

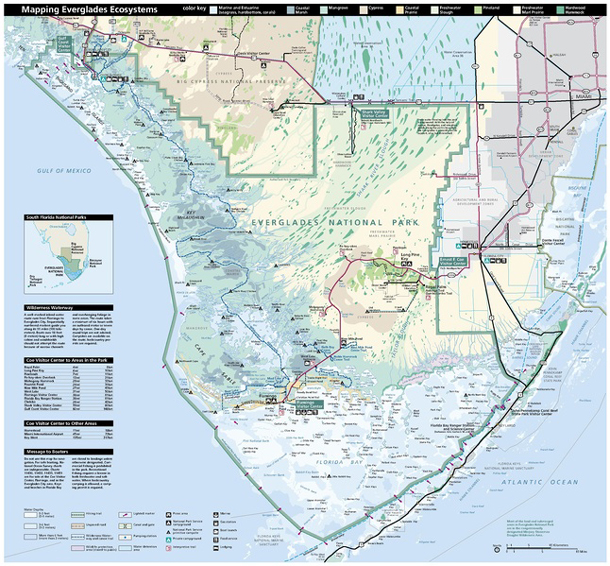

BASCOMB: The Everglades National Park in Florida is the third largest National Park in the lower 48 states and contains 1.5 million acres of protected wilderness. And UNESCO names it a world heritage site that’s in danger. The Everglades is often called the river of grass for its vast system of slow moving bodies of water which spread much further than the National Park boundaries. Over the years attempts to fill in and drain these wetlands to build homes and farms have damaged and polluted the Everglades. And, despite conservation efforts, today the Everglades is only about half its original size. Living on Earth’s Lizz Malloy went to visit Everglades National Park.

[MUSIC: Afro Cuban All Stars, “Amor Verdadero” on A Toda Cuba Le Gusta, World Circuit]

MALLOY: Miami, Florida. It brings some immediate images to mind, often involving beaches, parties, and glamour. From the tourist packed Ocean Drive, the bustling streets of Brickell, to the music filled air of Calle Ocho in Little Havana. Even if you are on vacation, in Miami it seems like there is no time to relax.

[MUSIC: Afro Cuban All Stars, “Amor Verdadero” on A Toda Cuba Le Gusta, World Circuit]

MALLOY: Many looking for a bit of peace and quiet from the never-ending party that is South Beach head south towards the keys.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

MALLOY: But, there is a sanctuary just an hour west of Miami. The vast and peaceful wilderness of Everglades National Park.

The Everglades National Park is only a portion of the natural ecological system that is the Everglades. (Photo: National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons CC)

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

MALLOY: As I drive west towards the national park the electricity of Miami dwindles and the skyscrapers fade away. The air softens as the sounds emerging from the open windows change from beeping horns to birds.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

MALLOY: There is a visitor center not too far into the park where I am going to meet my guide who will introduce me to many of the exciting species of the everglades.

KOMINOSKI: My name is John Kominoski and I'm an associate professor at Florida International University in Miami. I'm an ecosystem ecologist and I've been studying the Everglades for the past seven to eight years.

John Kominoski is an Associate Professor and ecosystem ecologist in the Department of Biological Sciences at Florida International University in Miami. His research focuses on organic matter processing at the interface of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems and is part of the Florida Coastal Everglades Long Term Ecological Research. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

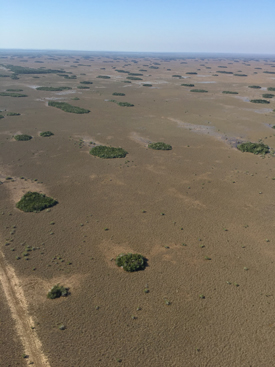

MALLOY: John sports an excited smile and long khaki pants, despite the 82-degree weather. He describes the Everglades as a mosaic of habitats and that nothing like it can be found anywhere else in North America. Soon we embark on a journey to one of John’s recommended trails. Dense carpets of grasses extend toward the sky on either side of the road.

KOMINOSKI: It looks like a prairie. It doesn't look like a typical wetland that people are familiar with. When you're on the ground, you can't really see these open water habitats. And you would probably assume that the whole area was dry.

The Everglades is spotted with tear drop shaped tree islands. (Photo: John Kominoski)

MALLOY: From the mid 1800’s to the mid 1900’s there were constant efforts to develop the Everglades because it was seen as useless land. It wasn’t until Marjory Stoneman Douglas wrote The Everglades: River of Grass in 1947 that people began to recognize the Everglades as the rare ecological jewel that it is.

[BIRD AND WALKING SOUNDS]

KOMINOSKI: Okay! So, here we are at Royal Palm. Also known as Anhinga Trail and Gumbo Limbo Trail.

MALLOY: John heads through the trail entrance past massive banyan trees enveloped by strangler figs that look like they are made of dripping wax.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

KOMINOSKI: There's always water here because it's a canal essentially. So this is a great place for people to come to see alligators to see fish and hear fish, and birds and frogs and all that. So, we've got the double crested cormorant that's resting there on that dead branch. And we've got -- red, the red bark tree is gumbo limbo, as in the gumbo limbo trail. It's also called the tourists tree because it's red and peel-y [LAUGHS].

MALLOY: Along the other side of the trail is a sea of grasses that extends towards the sky, meshing greens, golds, and blues. Speckling the sawgrasses and invasive cattails are a variety of birds that don't seem to mind our company.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

The native Anhinga is not easily bothered by tourists in the park. (Photo: alans1948, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

MALLOY: A native diving bird called the anhinga suns its wings on a railing as a group of visitors look on and angle for photos. Unlike other water birds, such as ducks, anhingas don't have oil on their feathers to keep them dry when dive in the water for their prey. This helps them weigh their bodies down so they can dive deeper, but to dry off it takes a little bit of time and some sunbathing.

KOMINOSKI: Should we walk down to the end of the trail…?

MALLOY: Yeah!

MALLOY: This trail is full of excited visitors pointing and smiling at all the different wildlife that surrounds them.

KOMINOSKI: Okay, so here's our first alligator and whoa! Active!

MALLOY: An alligator, some 6 feet long, jumps in the canal about five feet in front of us behind the trail railing and scoops up a baby alligator in its mouth like a snack.

KOMINOSKI: So, this is definitely a female. And, it's possible that that jump that she made was to protect her baby. Wow. That is really special.

[ALLIGATOR CHIRPS]

The American Alligator is an abundant species in the Everglades. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

KOMINOSKI: Yeah, she's definitely protecting that little one. Beautiful. This is kind of one of the beautiful, unique experiences you get when you're out in the Everglades.

MALLOY: Female alligators are protective mothers, who will sometimes keep their babies in their mouths to protect them from predators, like other alligators or even some birds. When they hear their babies making their distress call…

[ALLIGATOR CHIRPS]

MALLOY: ... the mother alligators go into full defense mode. But, I suppose that we aren't much of a threat because soon she lets her baby swim free from her jaws.

KOMINOSKI: This is the only place in the world where crocodiles and alligators coexist. And, fun fact, the American crocodile is very docile and actually more docile than the American alligator. So the American alligator is more territorial than the American crocodile, but the crocodile look scarier than the alligator to me.

MALLOY: I was inspired by John’s descriptions of the mangroves and megafauna that lie where the Everglades meets the ocean. So, I began my 30-minute drive south to the Flamingo visitor center. Grasslands became cyprus domes and cyprus domes became hardwood hammocks and hardwood hammocks eventually became mangroves as I reached my destination.

A scenic road connects Ernest Coe Visitor Center and Flamingo Visitor Center in the Everglades National Park. (Photo: John Kominoski)

MALLOY: I rent a kayak at the visitor center.

[WATER SOUNDS]

MALLOY: And paddle through the waters that are the lifeblood of the Everglades. Thrilled to be drifting past lumbering manatees and sun-bathing crocodiles. I feel like the star of my own nature documentary.

Where Everglades National Park meets the ocean, visitors can kayak through the mangroves. (Photo: Vincent Lammin, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[WATER SOUNDS]

MALLOY: I can easily see why my guide John Kominoski loves this national park.

KOMINOSKI: You don't have to be a scientist to appreciate and want to protect the everglades. I think you just have to be somebody that wants to connect with yourself and with nature in a place that is experiencing a lot of change and may not be here for as much time as we hope it will be.

MALLOY: And change here means sea level rise, development, and climate change, which all threaten this delicate ecosystem. But, drifting along with the manatees, all that seems a million miles away.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

The Everglades National Park, although only half of its original size, covers 1.5 million acres. (Photo: John Kominoski)

MALLOY: For Living on Earth, I’m Lizz Malloy in the Everglades National Park.

[BIRD SOUNDS]

Related links:

- More information about the Everglades

- Everglades National Park

- About Marjory Stoneman Douglas, author of "River of Grass"

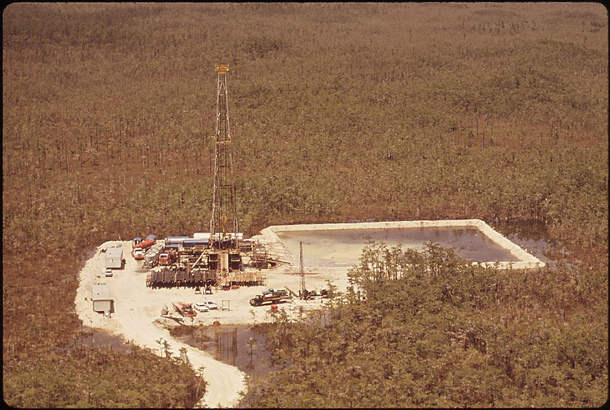

Drilling in the Everglades

The Everglades ecosystem is comprised of a variety of vegetation, such as sawgrass, that coats the expansive waterways that lie underneath. (Photo: Lizz Malloy)

BASCOMB: After years of legal wrangling, a South Florida family recently won the right to drill for oil in a part of the Everglades outside the National Park. I must admit, when I first read the headline "Florida Family Wins the Right to Drill for Oil in the Everglades," I thought it was a joke. But Miami Herald reporter Samantha Gross says it's very real.

GROSS: It's a real case that's been about four years of legal battle for this family who mainly is made its fortune in real estate to have granted permission to drill and exploratory well for oil in the Everglades, just west of the Broward County suburbs near Miramar.

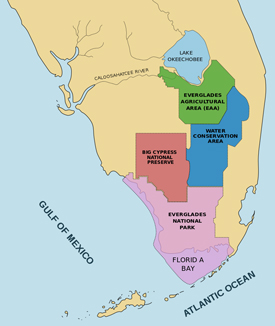

BASCOMB: So, this piece of land is owned by the Kanter family. They own about 20,000 acres in the Everglades. But this isn't actually the Everglades National Park. Can you tell me about this piece of land and where it sits in relation to the park and the whole system?

GROSS: Yeah, so this piece of land and specifically the piece that they want to drill on is part of this 20-mile-wide, hundred 50-mile-long stretch of shale that basically stretches between Miami and Fort Myers. It's called the Sunniland Trend and that western part of the stretch has been tapped for oil before, but the eastern part has not been tapped yet. And so the Kanter family wants to find potential for oil there. This eastern part of the land sits basically in one of the three conservation areas of the South Florida Water Management District, and it's just west of the Broward County suburbs. It's quite close to residential South Florida.

BASCOMB: But it's still technically the Everglades?

The Everglades is composed of much more than the national park. The Everglades reaches up through national preserves and conservation areas all the way up to Lake Okeechobee. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC)

GROSS: Yes.

BASCOMB: Now, from what I understand the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the local municipalities are opposed to the Kanter families plan to drill in the Everglades. But the First District Court of Appeal ruled against them. Tell me what happened there?

GROSS: Yeah. So the First District Court of Appeal did rule against them. From the folks that I spoke with DEP didn't have the right expert testimony. There were some things that I guess, you know, weren't as convincing as it could have been. But, Noah Valenstein, who's the DEP secretary, who was recently re-appointed, said that, you know, DEP hasn't changed its long-standing policy to deny oil and gas permits. And it's something that they, you know, we're going to continue to fight but, it's unlikely the agency is gonna to take it to Supreme Court, some attorneys have told me. So, the DEP put out a statement actually saying it's reviewing options and it wants to help Broward County and the cities in that area fight this plan. So the Department of Environmental Protection has come out saying that they're disappointed but that they're gonna to continue to review their options and work with Broward County and do what they can so.

BASCOMB: So, despite winning the permit to drill for oil and the Everglades, the Kanter family needs zoning approval from Broward County for them to move forward with this project. How likely are they to get that do you think?

Oil rigs in Big Cypress National Preserve have been active since 1943. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons CC)

GROSS: I feel like it's definitely going to be a fight. Broward County has come out and said that they don't support this plan. When the first District Court of Appeal announced this decision in favor, there was a request by the state of Florida, Broward County, and the city of Miramar to rehear the case, which was denied eventually. But, I mean, there's intense opposite in Broward County.

BASCOMB: Now the family they want to drill an exploratory well on five of their 20,000 acres. What will that entail?

GROSS: So, an exploratory oil well basically is just a well operation to see the potential for oil, not necessarily to extract oil. People have said that, if discovered, that well could produce about 180,000 to 10 million barrels at the very most and it would probably be priced at about $50 per barrel. You know, environmentalist say that oil that is extracted from the Florida shale isn't clean oil, it's not part of Florida's economy. It's not something that the state profited off of in the past.

BASCOMB: And, the family argued that the land that they want to explore for oil is already degraded, that this isn't pristine wilderness. So it's not a big deal. How true is that do you think?

GROSS: So, people that I spoke with including this one environmentalist comes to mind, his name's Matthew shorts, and he is the executive director of the South Florida Wildlands Association. He said that that whole argument that the land is environmentally degraded is ludicrous. And he, he kind of pointed out an interesting point, which is that in South Florida, specifically, limestone, which makes up major part of that land, is not going to isolate anything. It's not degraded land, it's extremely porous. And any sort of operation like this would really affect that piece of land just because if there's a washed over oil pad and rain comes through water is going to distribute that all over because the land is so porous, and it's so sensitive to anything really.

BASCOMB: What species do you think would most be impacted by oil drilling there if it does occur?

GROSS: So I think that actually humans would be the species most affected. People are really concerned with the groundwater contamination. Florida, in general has a pretty shallow water table and when something pollutes the groundwater, it spreads fairly quickly. And because the Everglades is a living, breathing, like moving water system, any sort of pollution would spread south and we've seen that before with construction operations and back in the day when they were trying to kind of drain the Everglades and build homes and make this kind of a developed piece of land. That pollution, you know, still affects species to this day, including species that are, you know, no longer there in Everglades.

BASCOMB: Samantha Gross is a reporter from the Miami Herald.

Related links:

- CityLab | "Why Planned Oil Drilling in the Everglades Has Florida Cities Worried"

- WLRN | “Energy Pro: Florida Is Not A Big Oil State. So Why Drill?”

- More information about the Everglades

[MUSIC: 2Cellos, “Cinema Paradiso” on Score, by Ennio Morricone/Andrea Morricone, Portrait/Sony Music Entertainment]

Fly-fishing Saved From Pollution

Matt Kowalchuk, a fly-fishing guide in central Pennsylvania, displays a brown trout he caught at Penns Creek. (Photo: Julie Grant)

BASCOMB: The wilder parts of the American West are famous for fly-fishing, but there are a lot of spots to catch wild trout in the Eastern U.S. including central Pennsylvania.

And that’s despite pollution from agriculture and development. Julie Grant of the Allegheny Front went to meet with some people who are working to keep those premier streams clean.

GRANT: It’s just before sunset, and 27-year-old Matt Kowalchuk is standing in the river, near the bank of Penns Creek in central Pennsylvania, not far from State College. He’s a fly-fishing guide, and chooses a lure meant to catch wild trout.

KOWALCHUK: We’re going to see if we can get one to eat a stonefly, It’s hard to pass up a big meal.

GRANT: Kowalchuk attaches the fly to his line, and walks deeper into the center of the fast-moving creek. He casts upstream. His line doesn’t dance through the air like in A River Runs Through It, but the lure lands lightly on the water, and floats down a ways. He doesn’t get any bites, so he pulls the lure out, and casts upstream, again.

KOWALCHUK: And you do it again, and you do it again, and you do it again, and you do it again, the next thing you know, a bar of gold just rolls up and annihilates your fly. That’s pretty intense. It gets the adrenaline pumping.

GRANT: Kowalchuk considered moving to Montana or Colorado after college, but he loves it here

KOWALCHUK: In the middle of Pennsylvania, mountains all around you, watching the bald eagles chase the osprey for the trout.

GRANT: In high summer, the water is still cool at about 60 degrees. It stays that temperature because it’s fed by cold springs and mountain creeks. Unlike some streams, the state doesn’t stock Penns Creek with trout.

KOWALCHUK: It doesn’t need it, this stream is Class A wild trout water, meaning that it has a naturally sustaining population of fish that does not need us to do anything about. If you come here in October and November, you can walk the stream and find the fish actively spawning, and that is cool to see.

Penns Valley Conservation Association member Lysle Sherwin (left) is looking for ways to stop erosion from contaminating the stream with David Martinec (right). (Photo: Julie Grant)

GRANT: One reason the trout do well here is the abundance of food. When I visited, Kowalchuk was just finishing up with the angling frenzy around the hatch of green drake, an especially large mayfly.

KOWALCHUK: That’s the reason that everyone comes to fish, the green drake, It’s actually pretty insane.

GRANT: Even closer to State College, in nearby Spring Creek, a spill of cyanide at Penn State in the 1950s wiped out the green drake population. The mayflies have never recovered there. There’s usually not one big pollution source anymore, today, it’s more like death by a thousand cuts. Urbanization and growth in State College, like rooftops, roads and parking lots, cause runoff and pollution in Spring Creek. In the more rural Penns Creek watershed, it’s the farms. One-third of the land here is used for agriculture corn, soy and dairy.

MARTINEC: This is a cow pasture, and that was a cow pasture. David Martinec is working with PVCA, a local non-profit, to restore the streambed at his long time family farm. He points to the high bank on the far side of the creek, where a backhoe is moving hemlock logs brought in for a restoration project.

MARTINEC: When we took the cattle off, the non-native invasive species just grew up , and choked everything out.

The PVCA’s Lysle Sherwin who leads many area landowners on projects like this, says the bare soil of the cow pastures left these stream banks without tree roots for structure.

SHERWIN: They’re falling into the stream, massive erosion.

GRANT: You can see silt from the eroding bank filling up the shallow stream here. Sherwin says this limestone bed is the spawning ground for trout, and the sediment literally smothers their eggs.

That’s why they’re building what’s basically a reinforced wall of logs along the stream.

SHERWIN: It simulates an eroded bank that has structure and function to it, but it’s a built bank, it’s a stable bank.

GRANT: Sherwin has worked on 14 improvement projects like this in recent years, and says the more they do, the more landowners want to try it.

SHERWIN: It’s sort of keeping up with the Joneses. ‘Oh wait a minute, they did that stream project, and it worked for them. And they seem happy with it.’

GRANT: Many of these projects get funding through a United States Department of Agriculture program that’s proposed to be cut in the House version of the 2018 Farm Bill.

Sherwin hopes funding doesn’t dry up, because the more stream restoration the better for the wild brown trout in Penns Creek and for the anglers who pour in to catch them.

I’m Julie Grant.

BASCOMB: Julie Grant’s story comes to us courtesy of the Allegheny Front.

Related links:

- Cabela’s guide to great fly fishing in the Eastern US, including Penns Creek

- Listen on the Allegheny Front Website

[MUSIC: Jeff Little, “’A’ Strange Thing” on Piano Man from the Blue Ridge, self-published.]

BASCOMB: Coming up – trying to make do with little fresh water in the Gaza Strip. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Punch Brothers, “Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, Allegro” on Live From the Lower East Side: It’s p-BingoNight!]

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Gaza Water Crisis

Mohammad Nimnim wheels water jugs, to fill at the mosque at Beach refugee camp. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

BASCOMB: Nowhere is the seemingly endless crisis between Israelis and Palestinians more acute than the Gaza strip, a hotly contested piece of land just 25 miles long and roughly 5 miles wide. Thousands of buildings were destroyed and more than 2200 Gazans were killed by Israeli forces in the 2014 war, with 71 deaths on the Israeli side. Twenty-two years ago, we sent reporter Sandy Tolan to Gaza to document the acute shortage of drinking water there, and back then he found that 85 percent of wells were too contaminated for human consumption. He recently returned and now that figure is up to 97 percent. Here’s his report.

TOLAN: The Shati refugee camp stretches for about a mile along Gaza’s Mediterranean coast. Shati means “beach” in Arabic, but it’s hard to find a cool ocean breeze here. The 87 thousand people squeezed into half a square kilometer of cement block dwellings are all refugees and their descendants. Of Gaza’s nearly two million people, three out of four are refugees - families forced to flee their towns and villages during the creation of Israel in 1948.

[WOMAN’S VOICE IN ARABIC]

TOLAN: Fatemah Nimnim was three when her family was driven out of the village of Hamama; she doesn’t remember much besides the refugee camp, where she now lives with three younger generations. They share three small rooms.

NIMNIM: Welcome! We are honored to meet you. May God give you health…

TOLAN: Today the entire family greets us in the front room – nineteen members of the Nimnim family. Most sit on the floor, backs against paint-chipped walls. They introduce themselves.

[NIMNM INTRODUCTIONS]

TOLAN: Today it’s 94 degrees and it’s really humid. It feels, unbearable.

Fifteen members of the Nimnim family, at home in the beach refugee camp. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

NIMNIM: It's hot, suffocating. There isn't enough space to sleep. There's no space at all, can you see.

TOLAN: There’s no fan, because electricity in Gaza comes just four hours a day, says Fatemah’s son, Atef Nimnim.

A. NIMNIM: Water and electricity? Forget about it. There isn’t any.

TOLAN: The water that comes out of the tap is way too salty to drink. That’s because the aquifer below our feet has been over-pumped so badly that seawater is flowing in.

[WHEEL CHAIR SOUNDS]

TOLAN: So, to quench the family’s thirst, 15-year-old Mohammad Nimnim piles plastic jugs into an old wheelchair and rolls it to the mosque, where sputtering taps provide the most basic necessity for life -- courtesy of Hamas.

[WATER SOUNDS]

TOLAN: For most people in Gaza, it’s not quite as dire. Two thirds of Gazans get water delivered by truck. Desalinated water is pumped into rooftop tanks via hoses.

[WATER GOING INTO A TANK]

Children gather under an umbrella in the Shati (beach) refugee camp. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

But when it comes to water in Gaza, better off is only by degree. The desalinated water is unregulated. And because this water has virtually no salt, it’s prone to fecal contamination, says former Palestinian deputy water minister, Rebhi Al Sheikh.

SHEIKH: And when it is a stored at the household water tank for many days more than 10 days then this level of contamination can reach up to 70 per cent.

TOLAN: That’s seven in ten people basically drinking poop, or e. coli if you prefer. And in terms of parts per million, UNICEF’s Gregor von Medeazza says the only really safe level is zero.

MEDEAZZA: So, already the presence of one is too much. Why? Because the moment you have one you actually have a potential for growth depending on how long you've got your water standing or sitting rather in those tanks.

TOLAN: I caught up with Gregor as he rode out to inspect new water projects in southern Gaza.

MEDEAZZA: The longer they are there the more you've got them protozoa you've got all sorts of other then little animals that actually start growing in your water and it just gets worse.

TOLAN: When children drink this water, they start getting the runs.

MEDEAZZA: So if you have repeated diarrhea the end result is actually your child would not grow to its full potential. You actually see children being stunted. What it also means is actually impediment in terms of brain development. You would actually have a measurable impact on the IQ of those children as they grow.

Fatemah Nimnim, family matriarch. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

TOLAN: Late last year a British medical journal found an “alarming magnitude” of stunting among Gaza’s children. And that’s just one effect.

[HOSPITAL SOUNDS, KIDS CRYING]

Gaza pediatrician Mohammad Abu Samia says say there are so many others.

SAMIA: In the summer day the hospital is very very very busy.

TOLAN: Dr. Abu Samia takes us through the children’s ward in Al Nasser hospital in Gaza city. He stretches out his hand, touching a baby girl hooked up to a respirator. Alone in her hospital bed, she looks even tinier. Some of these children have recently had heart surgery. The overwhelmed doctor says he’s seeing a sharp rise in disease and illness in children like gastroenteritis from the dirty water.

SAMIA: Baby suffering from dehydration, from vomiting, from diarrhea, from fever.

TOLAN: And because of the extremely high nitrate levels in the water, the doctor is seeing other effects.

SAMIA: We have children, kidneys not working now.

TOLAN: Before, he tells me, they had 15 or 20 cases at any given time. Now it’s 40.

SAMIA: Every day I have in the hospital ten babies in machine, in hemodialysis because of renal failure. And the number increasing.

TOLAN: And so are cases of something called blue baby syndrome. The high nitrate levels deprive the blood of sufficient oxygen. And so some babies look – blue.

Fishermen in the Gaza harbor. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

SAMIA: bluish lips bluish face bluish skin.

TOLAN: And blood the color of chocolate.

SAMIA: I see one or two kids the last ten years. But now I see five cases in the one year.

TOLAN: So. Sharp rises in Gastroenteritis. Stunted growth. Renal failure and hypertension from those high nitrate levels. Blue baby syndrome. And, Doctor Abu Samia says, he’s seen big increases in pediatric cancer – whether from water, the effects of three wars, he doesn’t know. And beyond the lack of water, he’s seeing the effects of malnutrition, which he blames on Israel’s economic blockade.

SAMIA: Nutrition is very bad. It is affected baby. Before siege, we don't have any patient with no malnutrition. Now we saw baby with marasmus. You know what is marasmus?

TOLAN: Marasmus is severe malnutrition, sometimes in newborn infants. Just skin and bone, the doctor says.

SAMIA: The last years increasing more and more.

TOLAN: Palestinian Health Ministry studies back up Dr. Abu Samia’s observations. They note a doubling of severe cases of diarrhea, especially in children, and “serious increases” in kidney disease, and in food and water borne diseases, including hepatitis A, salmonella, and typhoid fever. The British medical journal Lancet corroborates that shortages of clean, safe water have contributed to sharp rises in diarrhea among young children in the Gaza Strip. Diarrhea is the world’s second biggest killer of children under five.

HASNA: If you really want to change the lives of people you have to solve the water issue first.

TOLAN: Adnan Abu Hasna is a spokesperson for the UN agency for Palestinian refugees, UNRWA.

HASNA: Otherwise that you will see huge collapse of everything in Gaza.

TOLAN: Already Gaza is widely considered the world’s largest open-air prison.

HASNA: You can keep people in prison, surviving and giving them the minimum drops of water. Little of electricity, little of hope. Now I can tell you Gazans reach the level that people are thinking there is no tomorrow in Gaza. The. Kind of the dream you are not allowed to dream because your dreams will never be achieved will never be a reality.

Children drink and fill water jugs at a mosque in Gaza City. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

TOLAN: It may seem that Gaza’s torments are completely contained by layers of fences, locked gates, patrolling Israeli drones, war planes, and international indifference. But that’s not true.

One example: Because Gaza’s power plant runs only four hours a day, its sewage plant is basically useless. So, 110 million liters of raw and poorly treated sewage flow directly into the Mediterranean, every day –here on this beach, long pipes spew brown water into the ocean, just ten miles from Gaza City.

BROOMBERG: They are carried by the currents and north and the response was closing the beaches in Gaza itself.

TOLAN: Gidon Bromberg is director of Ecopeace Middle East, based in Tel Aviv.

BROOMBERG: A young five-year-old boy, unfortunately his family took him and the boy swallowed some water and within ten days he was dead. A virus got to his brain.

TOLAN: The child’s name was Mohammad Al-Sayis and Bromberg says some of the misery in Gaza does go beyond its borders.

BROOMBERG: It's led to the closure of beaches directly on the Israeli side of Sikkim.

TOLAN: Authorities even had to close an Israeli desalination plant for a time – because, who wants to try to desalinate water with poop in it?

Israelis, Bromberg says, need to wake up to the unfolding humanitarian disaster in Gaza.

BROOMBERG: It's a ticking time bomb. We have a situation where two million people no longer or no longer have access to potable groundwater. When people are drinking unhealthy water then disease is a direct consequence Should pandemic disease break out in Gaza people will simply start moving to the fences. and they won't be moving with stones or with rockets they'll be moving with empty buckets desperately calling out for clean water.

[PROTEST SOUNDS]

TOLAN: Assigning blame for the plight of Gazans is not exactly simple. Take the fact that three percent of Gaza’s drinking water wells are actually drinkable. Is that because Gaza’s citrus farmers pumped too much? Or because Israeli agricultural settlers depleted a deep pocket of fresh water before they left Gaza in 2005? Or the simple fact that Gaza’s population quadrupled in a matter of weeks when towns and villages fell to Israel in 1948?

The Gaza harbor. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

And how about the food and water borne diseases? That’s in part because the power is shut off for 20 hours a day. Do we blame Israel and Egypt for withholding fuel deliveries? Or Israel, for bombing water and sewage infrastructure in Gaza during the 2014 war? Or the fight between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, which deprives Gazans of critical medicines?

And what about Israel’s economic blockade of Gaza, which human rights groups say contributes to worsening poverty, skyrocketing unemployment and child malnutrition?

A peace deal could have connected Gaza to the West Bank, where the vast Mountain Aquifer is big enough to end Gaza’s water crisis. As it is, there is no peace. The two Palestinian territories are splintered. And Israel has effective control over of the water.

Critics say Israel could solve the whole problem by simply building big water and power lines into Gaza. But Israeli officials say they are already sending water to Gaza – and to do more would be rewarding Gaza’s bad actors.

SHOR: My name is Ori Shor. I am the spokesperson for the Israeli Water Authority. What's going in Gaza is a real catastrophe. The situation there is unbearable but it's also frustrating at least from our point of view. because it's a bit difficult to help someone that doesn't want to help themselves. The problem in Gaza is really that there Hamas people do not do nothing in order to try even to solve the problem.

The obligation of Israel in this agreement that we have. To provide a certain amount of water to Gaza and certain amount of water to the West Bank. Israel is providing it and they're providing more than twice the amount that we are obliged by our agreement.

That amount is just a fraction of the clean water Gazans need every day. And so, the situation in Gaza continues to deteriorate. Humanitarian groups estimate that Gaza will become uninhabitable by 2020 – barely a year from now. To avoid that international relief agencies, and the Palestinian water authority, are working on a network of big sewage and desalination plants.

MOAMAR: This is the feed water from the storage tank…

TOLAN: This is Kamal Abu Moamar, manager of the South Gaza Desalination plant. It’s a small first step. Eventually there would be a half dozen, along with big sewage plants -- $500 million dollars with, all funded by international donors. But my visit doesn’t inspire confidence. It’s quiet. We can hear the birds chirping in the rafters above the idle plant floor.

Families flock to the beach at dusk, Gaza City. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

TOLAN: So this plant requires a lot of electricity.

MOAMAR: Yeah.

TOLAN: You don't have more than four hours a day these days.

MOAMAR: At this time, we don’t have but we hope. Many of our ministers say that they will solve this problem. But we don't know when. Or how.

TOLAN: Basically, the half billion-dollar plant relies on two things that Gazans haven’t had in a long time: reliable power, and guarantees from Israel that it won’t bomb these plants in the next war.

MOAMAR: The Israeli can do anything she wants.

TOLAN: Mazen Al Binna, of the Hamas government’s water authority.

BINNA: Nobody can tell Israel that you are doing the wrong thing. Even Israel doing everything against international law but nobody can prevent Israel doing everything she wants to do.

TOLAN: It’s true that Israeli war planes have bombed the Gaza power plant repeatedly in recent wars, along with other critical infrastructure. Yet an internal Israeli army document promoting the desalination plan suggests Israel would be on board. But there’s no official word. An Israeli army spokesman would not return more than a dozen calls from Living on Earth. So I put the question to Gregor von Medeazza, the water expert from UNICEF.

TOLAN: Isn't that a risk?

MEDEAZZA: Any infrastructure is a risk in a context like Gaza. But then the question then obviously is what are the other options? Really what is the way forward? If we actually don't plan that would basically say we come to a standstill. And of course we cannot come to a standstill because we have two million people in the Gaza Strip that require and deserve better services.

[SOUNDS OF GAZA PIER]

A family enjoys a respite from the sweltering heat of the beach refugee camp. (Photo: Abdel Kareem Hanna)

TOLAN: On a dusky summer night, on a stony spit of land in the middle of Gaza Harbor, five of those two million people try to enjoy a few minutes of peace. All around Ahmad and Rana Dilly and their three young children, the harbor ripples with life: fishermen hauling up their nets, kids posing for selfies on broken concrete blocks and rebar, remnants of an old bombing raid.

[NIMNIM FAMILY]

Ahmad and Rana invite me to join them under their beach umbrella. We sit in plastic chairs. Rana pours us mango soda; with a smile, Ahmad insists that I sample some chocolate wafers. Their three young children eye me shyly, nibbling on chips.

The Dillys have the same problems as many Gaza families. Ahmad’s a money changer. An Israeli missile destroyed his shop in 2014. He rebuilt it. And, like most Gazans, they have to contend with the salty water from the taps, and the inherent risks of disease from the trucked water they rely on. But these problems mean little to them compared to their wish to feel safe, and to enjoy fleeting moments like this of living as a normal family.

DILLY: I want just to change something for my family and my kids. I want to do something, to get them to see something different. I’m looking for my family just to feel safe.

In the distance, we hear an explosion. Ahmad pauses for a short moment, then ignores it. He says, I come here, just to forget everything…

For Living on Earth, I’m Sandy Tolan in the Gaza Strip.

Related link:

Reporter Sandy Tolan’s Website

BASCOMB: Every week we put together a news letter for you, the listeners to Living on Earth. There you can have an insider’s look at the people and ideas that come together to make this program. And right now you can even give us some advice. When you sign up for the newsletter you’ll be invited to complete a survey to tell what you think about our program. Just go to loe.org to subscribe where it says newsletter.

[MUSIC: Michael Johnathon, “Moon Fire” on Moon Fire-The Banjo Album, Poet Man Records]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Diego Arenas, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at LOE.org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood will be back next week, I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth