October 4, 2019

Air Date: October 4, 2019

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Trump Fights California

View the page for this story

The Trump administration has revoked California’s waiver to set stricter vehicle emissions standards than federal rules require, and that more than a dozen other states have adopted, and California is already fighting back in court. The administration also opened Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil exploration. Vermont Law School Professor Pat Parenteau discusses these developments with host Steve Curwood. (12:44)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood take a trip beyond the headlines this week to look at the MacArthur Fellowships nicknamed ‘genius grants.’ Then they look at two proposed dams near the Grand Canyon. Finally, the two check the history vaults to examine Saturday Night Live's bee characters, who appeared in a controversial skit about Africanized Bees. (04:17)

Success of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

View the page for this story

In 2005, seven Northeast states teamed up to create a market-based carbon reduction plan best known by the acronym RGGI, and since then three more have joined . David Cash, from the University of Massachusetts Boston helped create the plan. He tells host, Steve Curwood, about a new study that finds participating states have dramatically reduced their emissions while at the same time lowering electricity rates for consumers. After the recording of this segment, Governor Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania began taking steps to add the Keystone State to the RGGI plan. (11:41)

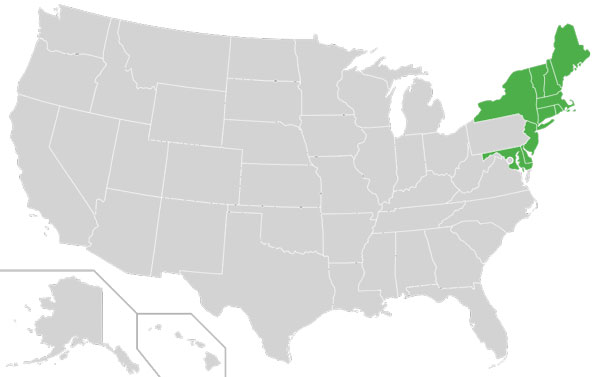

DNA Barcoding for Quick Species ID

View the page for this story

Roughly 1.3 million species have been identified and recorded, but that’s just a fraction of life on our planet. A new advancement known as DNA barcoding samples small but key parts of genomes to ID species. Paul Hebert, lead scientist at the International Barcode of Life Consortium, explains the process and what it could mean for cataloging biodiversity. (08:17)

Bison and Sustainable Land Management

View the page for this story

Bison, which are native to the great plains of North America, have many ecological advantages over their cattle cousins, which were introduced by Europeans. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb reports on ranchers in Mexico who are breeding bison to help the species rebound and manage their land more sustainably. (10:27)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: David Cash, Paul Hebert, Pat Parenteau

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From Public Radio International – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

The White House wants to revoke rules dating back to 1970 that permit California to set its own vehicle emissions standards.

PARENTEAU: It’s sort of the height of hypocrisy, frankly. On the one hand the Trump administration is telling California “you don’t need these stricter standards; you can’t dictate environmental and economic policy to the nation.” And on the other hand the Trump administration is saying, “you’re not doing enough to clean up your air.” It can’t be both.

CURWOOD: Also, ranchers in Mexico are looking away from cattle and toward bison to manage their land more sustainably.

PAULSON: Generally speaking, bison are considered hardier, more adaptable animals. They can withstand heat and cold, better than cattle. And in fact I would say that they are the perfect North American animal if there is one.

CURWOOD: We’ll have those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Trump Fights California

California’s severe vehicle pollution and smog problems has put the state at the forefront of clean air policy. Thirteen other states have adopted California’s stricted tailpipe standards in order to reduce carbon emissions as well as smog. (Photo: Prayitno, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRI and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

The Trump Administration is moving to revoke the permission California was granted nearly fifty years ago to enforce more stringent vehicle pollution standards under the Clean Air Act than the rest of the US. The Los Angeles basin was choking with smog back then, and though air quality has improved it still has concerning levels of air pollution. The 1970 California wavier opened the door for 14 other states, many in the Northeast, to also adopt those tougher vehicle pollution standards. And after the US Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that carbon dioxide is a pollutant the clean air act waiver has been a key tool to fight climate change. The Trump Administration is opposing many measures to address climate disruption, and its bid to hamstring efforts tied to the California Clean Air Act waiver is facing fierce opposition in the courts. We’re joined now by Vermont Law School professor Pat Parenteau to discuss this and other court room battles between the Trump Administration and conservation advocates. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Pat!

PARENTEAU: Thanks Steve, good to be here.

CURWOOD: So, the Trump administration wants to take away the waiver that California has had since what the 1970s to set its own car air pollution standards, what would it take for them to be able to do that?

PARENTEAU: Well, according to California it would take an amendment to the Clean Air Act, because currently there's no language in the Clean Air Act that would authorize the Trump administration to revoke the waiver that's been granted by the Obama administration. In fact, California has had about 50 different waivers granted over the course of the Clean Air Act. So this is the first time any administration has ever proposed to revoke a waiver for California. The Trump administration is arguing that their revocation of this rule prevents California from setting standards for the rest of the nation. That's that's the big argument. One state shouldn't dictate to the rest of the states. But here's the thing. The whole idea of the California waiver was to do exactly that. Congress of the United States gave California this authority, because California had some of the worst air quality in the country and still does. But also Congress said, if other states wish to join California, and agree to implement their standards, they can do so. So the Trump administration's argument is really with Congress not with California.

CURWOOD: Well now what there're 13 states that have adopted the tailpipe standards in California, what would happen to not just the Californians is but the residents of those other states if in fact, somehow the Trump administration is able to unwind the waiver?

California is fighting against the Trump Administration's attempts to revoke California's clean air waiver, which sets strict vehicle emissions standards. (Photo: Cindy Shebley, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

PARENTEAU: Right? Well, you know, the 13 states that have agreed to implement California standards represent 40% of the car market in the United States. So these states are relying on California standards, not simply to help them achieve their own clean air objectives. Remember, air pollution travels across state lines, of course, so some states cannot achieve compliance unless other states comply with these standards, you take those standards away, you're going to interfere with jobs, and economic progress in some of these states. Because these cleaner, more efficient vehicles have been pretty good job producers. We might recall that the automakers were in bankruptcy when President Obama took office, and he had to bail them out with billions of dollars of taxpayers funding. One of the reasons the automakers were in such financial trouble was they were being out competed by more efficient vehicles coming from Asia and other parts of the world. So this is a real setback, in terms of economy as well as environment.

CURWOOD: Now, another thing that the Trump administration wants to do along these lines is to actually get rid of these stiffer car, mileage standards efficiency standards that the Obama administration had implemented.

PARENTEAU: Yes, Obama had targeted average car efficiency standards to be 55 miles per gallon by 2025 fleet of automobiles coming onto the market. And what the Trump administration wants to do is actually freeze standards back to 2020 levels, which is something less than 30 miles per gallon. And this would be a huge setback for fuel efficiency, and obviously, climate mitigation and carbon reduction. It's not justified economically, the Trump administration is claiming their rule will save consumers money but when you look at it from the standpoint of the savings realized over the life of these more efficient vehicles, the average would be $3,000 in savings from the higher fuel efficiency standards. So it's not an economically justified move and it's not an environmentally justified move.

CURWOOD: Why is the Trump administration doing this, then?

PARENTEAU: You know, part of it is the war that the Trump administration is having with California. I mean, just recently, they've issued an ultimatum that California improved the way it's implementing the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, they're claiming that the homeless problem in San Francisco is worse than it is anywhere else in the country, and therefore, they're not meeting their water quality standards. And the odd thing is, or the ironic thing is, automakers didn't ask for this kind of dramatic rollback. They asked for some more flexibility in meeting some of the Obama standards. And four of the major automakers of course, have broken ranks with Trump and agreed to meet the California standards. And in payback for that the Department of Justice has opened an antitrust investigation against those four automakers that's unprecedented. So part of this is just nothing more than political warfare. It really doesn't have a whole lot to do with environmental policy, or economic policy.

CURWOOD: How much does it have to do with oil? It would seem that the large oil companies would benefit. If efficiency standards are lower, they get to sell more gasoline.

PARENTEAU: Well, that's true. California does have zero emission vehicles and electric vehicles as part of their plan. But in the short run, the more that you drive, the more gas you buy. That's certainly true.

CURWOOD: By the way, in the middle of all this, the Trump administration is threatening to remove California's Federal Highway funding saying that it hasn't addressed air pollution properly. Tell me more about this and how it could possibly make sense.

PARENTEAU: Yeah, well, that's sort of the height of hypocrisy, frankly, on the one hand, the Trump administration is telling California you don't need these stricter standards. You can't dictate environmental and economic policy to the nation. And then on the other hand, Trump administration says you're not doing enough to clean up your air, it can't be both. And in fact, California has always been the leader in the United States in innovating clean air technology, the reason we were able to get the lead out of the air, in large part is because of the catalytic converter and that came right out of California. I mean, the threat of taking away highway funds. That's that's actually not happened for as long as I can remember. So some of these bullying tactics may not be seriously followed up, California may be able to go to court and challenge some of the efforts to cut off highway fundings. I don't see that some of these moves or threats by the Trump administration are necessarily going to come to fruition we'll have to see.

California is susceptible to smog accumulation due to a large number of vehicles and the location of major metropolitan areas in basins or valleys that trap air circulation. (Photo: Traveling Otter, Flickr, CC BY SA 2.0

CURWOOD: I want to shift topics here, although it does involve oil. Because in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that was passed by the Trump administration in 2017, not only did it change tax rates, but it opened up part of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge there up in the far north of Alaska to oil and gas exploration. And a recent environmental impact statement by the Bureau of Land Management says that 69 of 157 birds in that coastal plain can go extinct as a result of oil and gas drilling yet seems like the Trump administration is pushing ahead. I don't get it. How is it that a government agency can say that they're going to be a bunch of extinctions, and yet approve oil and gas drilling?

PARENTEAU: Right, so this is the coastal plain of Alaska, it's about 1.6 million acres, it's the last truly untouched part of the American landscape that we have, there literally is no development, no significant human presence, the Gwich'in, people use the Alaska coastal planes very heavily for subsistence hunting, caribou, and other things. But there's no mark of human habitation whatsoever. And so yeah, here comes the Trump administration's proposal now to lease the whole thing. I mean, when they looked at the environmental impacts, they considered a range of development options, and wouldn't you know it, they picked the one to develop the whole 1.5 million acres for oil and gas exploration, that's at least the first step in this process. And it's, again, counter to everything that science is telling us, which is that we need to leave a lot of these fossil fuel reserves in place. Why on earth, would you be going to one of the most sensitive, biologically important parts of America to look for oil, when we still have a glut of oil coming from lots of other places on public lands and offshore? The answer is, on this one, this is what the delegation in Alaska wants. And this is what the delegation has been given from the Trump administration. But the irony here is, you could go out there start building these roads. And these drilling pads start punching holes into the permafrost looking for oil. And if it comes up empty, if it comes up that there really isn't that much commercially recoverable oil, we will have done all this damage to this pristine wilderness for nothing.

CURWOOD: And if there is oil, and it's extracted, there'll be plenty of damage as well, it sounds like.

PARENTEAU: They'll even be more damage. And then of course, the question is how much revenue. This all began, as you pointed out, part of the tax bill, and the claim was that it could be billion dollars’ worth of oil underneath the coastal plane. But other analysts have looked at it and said, there's far less than that. And when you pencil it all out, according to taxpayers united of America, it's only about $20 million worth of net revenue to the government a drop in the bucket, shall we say, in terms of the debt that the country is facing?

CURWOOD: Let's walk quickly through now the legal options here, California I imagine is going to fight this move in court with ferocity there are plenty of lawyers to speak up for them. But in places like the Anwar dispute, how are things shaping up legally here, Pat?

PARENTEAU: Yeah, so I think the Trustees for Alaska is going to be the lead group bringing the lawsuits on behalf of the Gwich'en and other interested parties. Earth justice, of course, has a major office in Alaska, Natural Resources Defense Council is likely to be part of the team. I'm guessing there's going to be a fairly large team of lawyers. Defenders of Wildlife, this particular coastal plane, because of the loss of the pack ice, and sea ice in the Arctic, has become ever more critical for the polar bear survival in denting activities. And of course, we have the porcupine caribou herd, which is the largest caribou herd in the world. And this is their only caving grounds. So you're going to have a combination of wildlife groups, native peoples, and just a lot of people concerned about conservation of America's natural resources, jumping in on this lawsuit. So I think these leases could be tied up in litigation long enough that a new administration will have a chance to reverse direction on this.

CURWOOD: The track record of the Trump administration when it goes to court to try to deal with regulations or deregulating in the area of the environment isn't particularly good. What's their winning average so far?

The Porcupine Caribou herd migration is highly significant to nature and indigenous peoples in the Arctic, and the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve in Northern Alaska is a key part of the migration ecosystem. (Photo: Wally Gobetz,

AMNH: Hall of North American Mammals, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 )

PARENTEAU: Yeah, according to the New York University's Institute for Policy integrity, which tracks every single case, against the administration, they've lost more than 90% the challenges to the roll backs that they've been carrying out across the board on environmental issues. So in many respects, the administration doesn't seem to value very highly, crossing the T's and dotting the I's and making sure that their decisions are bombproof legally. And maybe part of the reason for that is they're out to disrupt government, environmental policy as much as they can. If the courts stop them, they'll turn to their base and say, well, we tried. You see, this is why we need more conservative federal judges, this is why I need a second term to pack the benches more. So regardless of win or lose, this is always a political game. It seems to me.

CURWOOD: Pat Parenteau is a former EPA attorney and professor at Vermont Law School. Thanks Pat.

PARENTEAU: Thanks Steve!

Related links:

- Los Angeles Times Column: Can Trump legally revoke California’s clean air waiver? Probably not

- Bloomberg | “Trump is not Wrong About California’s Smog but he is not Helping”

- Reuters | Trump fight on California auto emissions could outlast presidency

- The Washington Post | “Trump Administration Opens Huge Reserve in Alaska to Drill” The Washington Post | “Trump Administration Opens Huge Reserve in Alaska to Drill”

MUSIC: Joshua Rifkin, “The Ragtime Dance” on Scott Joplin Piano Rags, by Scott Joplin, Nonesuch]

CURWOOD: Coming up – success with a regional deal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Joshua Rifkin, “The Ragtime Dance” on Scott Joplin Piano Rags, by Scott Joplin, Nonesuch]

Beyond the Headlines

Controversy has arisen over a bid by the federal government to raise The Shasta Dam in Northern California by 18 and a half feet. (Photo: Ray Krebs, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's Living on Earth. I'm Steve Curwood.

And joining us on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia is Peter Dykstra. He is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He's going to give us a look beyond the headlines right, Peter?

DYKSTRA: That's right, Steve, and I want to talk about three climate scientists that are among the two dozen or so 2019 MacArthur Genius Grant recipients. $625,000 to artists and scientists. It's distributed over five years to people who have demonstrated genius in their fields, but even more, demonstrate the potential for greater genius.

CURWOOD: You know, funny thing is the MacArthur people these days don't really like people to call them "genius grants". But in fact, the people who've gotten this money in the past, they certainly are geniuses.

DYKSTRA: And the people who got the grants this year are geniuses as well. Let's take a look at a few past grantees. The late sax player, Ornette Coleman. The creator of Hamilton, Lin Manuel Miranda. Those are two examples from the arts. From the sciences, John Holdren, who was Obama's science advisor, or Paul Ehrlich, the famous advocate on population and environment.

This year, there are three climate scientists among the recipients. Harvard's Jerry Mitrovica studies sea level rise. Andrea Dutton of the University of Wisconsin studies how ice sheets melt to create sea level rise. And Stacy Jupiter of the Wildlife Conservation Society studies the human impacts in places like Pacific islands that may be lost to rising seas and more intense storms.

CURWOOD: What else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: We're going to talk about dams. In one instance, there are two dams proposed for within five miles of the Grand Canyon National Park. They would turn the Little Colorado River into a reservoir, not only ruining some scenery and sensitive ecological sites, but also sensitive cultural sites for Native Americans. And I've gotten another dam issue for you.

CURWOOD: And that would be?

DYKSTRA: Remember two years ago, when the Oroville Dam in California was said to be near collapse, threatening cities and towns down river?

CURWOOD: Oh, yeah.

DYKSTRA: Well, there's similar fears for the Shasta Dam in Northern California. Interior Secretary David Bernhard favors the solution that both engineers and ecologists say is wrong: building a higher dam.

CURWOOD: Building a higher dam would somehow be an improvement? I'm confused.

DYKSTRA: Well, here's a few things that could go wrong with that higher dam. Number one, the bigger lake would flood farmland, destroy a world class fly fishing stream, and a stretch of designated wild and scenic river, all while creating an even bigger consequence if that bigger dam should fail.

Two Africanized honey bees, colloquially known as “killer bees”, which were the inspiration for a Saturday Night Live skit featuring the show’s early reoccurring bee characters. (Photo: Jessie Eastland, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, so there must be somebody though, who thinks that this is a good idea? Who is that?

DYKSTRA: Yeah, the farmers downstream in the Central Valley. And you'll never guess who is a lobbyist for one of the biggest water districts in the Central Valley.

CURWOOD: Let me see. No, no, no, no, not the Interior Secretary.

DYKSTRA: That would be Interior Secretary David Bernhardt. Now he's going to regulate on an issue he used to be paid to advocate for.

CURWOOD: Hmm. Well, let's take a look back now in history, and what do you see today?

DYKSTRA: Well, let's go back to October 11, 1975. The very first episode of Saturday Night Live aired. They included the first of the famous bee skits that populated the first few years of the show. The bee characters appeared several more times. Perhaps most famous was the "Killer Bees" skit that appeared in early '76. That one was about an invader bee species, aggressive Africanized Bees that had begun showing up in Texas after crossing the border from Mexico. It was feared back then that the Africanized bees would overwhelm native bee populations. But that never really happened. The skit however, is based on some pretty awful racial stereotypes of Mexicans. And what was funny to a Saturday Night Live audience back in 1976 would never make it on air today.

CURWOOD: Thank heavens. Thank you. Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more of these stories at our website, LOE.org.

Related links:

- Inside Climate News | “Meet the 3 Climate Scientists Named MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’ Fellows”

- The Arizona Republic | “Two New Dams Near the Grand Canyon? Conservation Groups Call the Plan ‘Unconscionable’”

- The Sacramento Bee | “Oroville Dam Spillway Crisis: Here’s What Happened in Visual Detail”

- Berkeley News | “Federal Effort to Raise Shasta Dam by 18.5 Feet Is Getting Some Serious Pushback”

- Click here to see SNL’s Killer Bee sketch

[MUSIC: Eduardo Bartolotti/Pascual Cerezo, “The Bee” by Franz Schubert]

Success of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

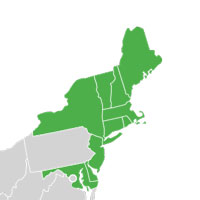

Including Pennsylvania, RGGI is comprised of 10 members states in the Northeast United States. (Photo: MarginalCost, Wikimedia Commons, CC)

CURWOOD: The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative called RGGI, is one of the unsung heroes fighting climate change in the United States. It’s a market-based collaboration among ten states in the Northeast that caps and gradually reduces carbon emissions from electric power plants. Revenue from RGGI is invested in clean energy projects, energy efficiency programs, and green startups. A new report by the Acadia Center tallies up the CO2 reductions, cost savings, and health benefits of the program and found that power plant emissions in RGGI states have fallen by almost half in ten years and that’s 90 percent more than the rest of the country all while making electricity cheaper. David Cash is a former energy and environment commissioner for Massachusetts who helped develop RGGI, and he now leads the McCormack Graduate School at UMass Boston. David Cash, welcome to Living on Earth!

CASH: It's great to be here, Steve.

CURWOOD: So exactly where did the idea for-for RGGI come from? Why the 10 northeast states?

CASH: In the early 2000s, it was becoming more and more apparent that climate change was a significant issue that would have health impacts and ecosystem impacts and damage our coasts. All of the things that we actually see happening now. Increase of wildfires, more hurricanes, and more severe hurricanes, all of those kinds of things were predicted then. And it was also seen more and more, that there were significant economic opportunities that might come with addressing climate change if one did it wisely. There would be opportunities for reduction of energy costs, there would be opportunities for innovation and job growth in the clean energy sector. And at the time, there had been cap and trade programs, for SO2. It was very successful at combating acid rain, with the cost of compliance, much less than anyone had predicted. And the innovation of new technologies, much better than anyone had predicted. We thought this would be a really good opportunity to address this problem in a market, you know, the Northeast is a pretty good market, it's large, we are all on combined electric system. So it would be relatively easy to regulate. And the Northeast has been a mover in environmental issues, historically.

CURWOOD: Now, SO2, sulfur dioxide, you point to that as an example of a cap and trade program that worked really well. Just what exactly was that cap and trade program and how those work anyway?

CASH: Here's a critical parts of cap and trade. The government sets a limit on what the entire industry can emit. Now, I don't remember the exact tons in SO2. I'm gonna say 100 and thats very, very low. But let's say the whole industry, the whole electrical industry can only emit 100 tons. And let's say they're emitting 120 right now, right. So in sometime future, they have to be under that cap. So those power plants that can be really efficient and produce more electricity without emitting so much, they're going to have allowances, they can sell to some of those plants that aren't as efficient. And in the SO2 program, all of those power plants were given their allowances, they call them grandfathered. So if you emitted eight tons last year, or whatever the year was, you know, they have a baseline year, you got your eight tons, and then you could trade those. Now, if you think about it, that means you're given a lot of value to these companies, right.

CURWOOD: Mhm.

CASH: And at that time, with this being the first ever of these kinds of complicated programs, politically or otherwise, it was smart to give those out. Even though the government and the public lost out on the value of those. Okay. By the time we came to doing RGGI, there was a lot of debate within the RGGI states, do we require an auction? Do we require a certain percentage? They're being allowed to pollute. They're being allowed to dirty our air. Now to limits that we think will not damage us too much or the planet that much. But that's quite a privilege, and they should pay for it. And, so, that's how we structured the RGGI program was that they had to buy those allowances. So that was one way states got that money. And in Massachusetts, we plowed it right into energy efficiency. We made it easy for you to get energy efficient stoves, energy efficient furnaces. To winterize your house, to get energy efficient light bulbs. All of these things that might cost a little bit more, we made it easy for you to do that. We plowed that money right back into it. So that's one way. The other way is, remember, the power plants had to buy those allowances. Would wind plants have to buy those allowances? No.

CURWOOD: No.

CASH: No, of course not. Because they're not admitting anything. They don't need an allowance, right? You use the allowance, at the end of the compliance to say I admitted 10 ton here are my 10 allowances that shows, that keeps everybody in compliance. Wind doesn't have to do that. So if you're a wind developer, there's a whole expense you don't have to worry about. So you can compete. Those are the two basic ways that the market really works well in these kind of programs.

CURWOOD: And then what about the factor that if you are taking this money and you're providing it to electricity consumers to buy more efficient. Everything from light bulbs to the furnaces and such, that would lower the demand for energy. And if you lower demand, you tend to lower prices?

CASH: Exactly. That's the third way that I didn't talk about. That you're lowering demand throughout all of this, which means, as you say, basic economics 101 has less demand and the price should go down. So the price goes down. So our models showed that even for customers who would not get new light bulbs and all that kind of stuff, their energy bills would generally be going down.

CURWOOD: Of Course one of the big obstacles for this was, in fact, how the state of Massachusetts was towards the end of these negotiations. Tell me that story?

CASH: Sure. So, Massachusetts had been a very active player from the beginning, shortly after Governor Pataki republican governor of New York had invited the Northeast governors to participate. And I mean, we had thrown lots of resources at this from the highest levels. Lots of staff hours went into this, and a lot of investment went into this. And during the negotiations, this give and take between governors, between states, we worked hard to get Governor Romney the things that were important to him. And at the last moment he pulled out. So, this was in December of 2005, I believe.

CURWOOD: You're telling me that Governor, Mitt Romney, at the very last moment he yanks the rug out from under this project.

CASH: He did, he did. And I never talked to him about it. So I don't know what his motivation was, what his interests were. But that's the path that that he put us on is pulling us out of it.

CURWOOD: I imagined that the big fossil fuel interests weren't so crazy about this. And maybe he was thinking about the White House.

CASH: Uh, that's, that's possible.

CURWOOD: So, then how did RGGI come to being in Massachusetts?

David Cash is a former energy and environment commissioner for the state of Massachusetts and is the current dean of the McCormack Graduate School at UMass Boston. (Photo: Courtesy of UMass Boston)

CASH: So, we continued monitoring the other states after they started. Everybody but us signed an MOU, a memorandum of understanding between the states. Because at this time, the federal government was not stepping up. This was in the George W. Bush years, there wasn't a lot of activity on climate change. And as Governor Pataki noted, in his invitation letter, if you can't do this federally, regionally is much better, right. The larger the region, that market I described, works much better and lowers prices much better. And, uhm, so we waited and waited and, and then Governor Patrick was elected, I was lucky enough to make it through the transition and be bumped up to be Assistant Secretary for Policy in what became the new Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs with the idea that how could you regulate and have policies about energy and not have environment at the table and vice versa, right. And so we fully briefed him on all of the data, all of the models, all of the outputs from the whole RGGI process. And of course, he was interested in emissions, he was interested in health impacts, and he was interested in bill impacts. And we had the data that showed, as I described, with the auctioning and the reinvesting of that, those funds into energy efficiency, where we're going to lower bills. So, on day seven of his administration, he announced that he was joining and in fact, he did it on this campus at UMass Boston. It was quite remarkable.

CURWOOD: Now, David, the RGGI program itself, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, is, well, it's pretty invisible...

CASH: Mm, it is.

CURWOOD: ...to people on the street. Somebody who pays money to electric utility, for example. What does it mean for people, though, in their day to day life?

CASH: It means that they're going to get notices from their utility that they wouldn't have gotten before. A notice that says, hey, do you want a free energy audit of your house? And once we determine what your needs are in your house, do you want free light bulbs. You'd notice that your utility would offer to pay a large percentage of getting your house weatherized. You'd know that you could get a zero percent financed new natural gas furnace, or the newer kinds of electric heating and cooling devices that are way more efficient than air conditioners, and the old baseboard heaters that you remember. Those are all things you'd never see RGGI on it. You'd never see that this is a complicated policy, but you would see 'Oh, I have the opportunity to do this.' Or you would notice that your neighbor is working at a startup in Cambridge, or in Springfield or in Pittsfield. And, why are they in a startup? Because the market incentives are there for a lab researcher to start to try to make the new battery or the new photovoltaic cell or the new kind of electric vehicle. And then you might notice that your neighbor has solar panels on their roof and you go over to them and you say, 'Hey, What's that on your roof? I didn't know you're a Greenie.' And they'll say 'I'm not a Greenie. I just knew that if I put these on my roof, I was gonna not pay electric bills forever!' And then you're like, 'Oh, how do I do that?' That's how you would see it day to day, I'd see these changes happening in our society, and in how we buy energy and use energy in ways that are really profound.

CURWOOD: So, David, looking back to the launch implementation of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, which you participated in. Tell me a story of when you got either really excited or you were really surprised by what was going on? What was that aha moment?

CASH: Well, I think as someone who was, again, part of a team, in some ways, stretching to do something that hadn't really been done before. When the first numbers started coming in, of what revenues the states are getting, and how much it was saving consumers. When those numbers first started coming in. It's like opening up a champagne bottle at the at the end of a of a championship game. You know, like, yeah, we've- this is what we strived for. This is what we worked for. This is what our theory said would happen. But, wow! We made something work that could be a model for other jurisdictions. We made something work that was impacting people's lives in really powerful ways that they might not ever know about. We realize that they were low income families whose electricity budget which is a much bigger part of their family budget than for middle income and high income, that slice of their budget was relieved so they could spend more money on health care, on food. Those kinds of realizations when the when the when the numbers started coming in. That was pretty remarkable. And the fact that this just continued on that trend. I mean, this is- this has staying power.

CURWOOD: David Cash is a former environmental and public utilities commissioner in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He's currently Dean of the McCormick Graduate School Policy and Global Studies at UMass Boston. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today, David.

CASH: It's been a pleasure, Steve.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative

- Inside Climate News | "Pennsylvania, A Major Fossil Fuel State Is Joining RGGI, the Northeast's Carbon Market"

- The Acadia Center report on RGGI

[MUSIC: Dana Robinson, “Crossing the Platte” on National Parks: America’s Best Idea, by Dana Robinson, PBS]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Using key fragments of DNA to quickly identify species. That’s just ahead here on Living on Earth. Stay Tuned!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com. This is PRI, Public Radio International.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dana Robinson, “Crossing the Platte” on National Parks: America’s Best Idea, by Dana Robinson, PBS]

DNA Barcoding for Quick Species ID

Samples of an organism’s genome are obtained in the field, before being brought back to the lab for the barcoding process. (Photo: Natasha de Vere & Col Ford, Barcode Wales, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Modern society has yet to record all the species on our planet but we do know that the 1.3 million we’ve registered so far represent a tiny fraction of the abundant life on Earth. To make it easier to identify species, the International Barcode of Life Consortium is using a technique known as DNA barcoding. It can give a quick readout that tells whether a sampled organism is known to modern science, and if not provides a marker to register it as a newly discovered life form. Paul Hebert is the molecular biologist who developed DNA barcoding. Paul, welcome to Living on Earth.

HEBERT: Yeah, thank you, Steve.

CURWOOD: So, take us through the process of DNA barcoding. You find an organism you want to identify, and then?

A simplified flowchart of the process of DNA barcoding. (Photo: LarissaFruehe, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0))

HEBERT: Well, I mean, you might just touch it, would be the simplest thing, and pick up enough of its DNA. I suspect you wouldn't like me to do something more destructive with you, so, simply touch you and I would pick up enough DNA off your surface, any vertebrate. But in the case of smaller organisms, where we may be prepared to sacrifice them, and where we want to have a voucher specimen in a collection that we can look at, and photograph and analyze in other ways, we might remove a tiny piece of tissue. If it were an insect, six legs, remove one of those legs and extract the DNA from that. That's a fairly simple process. When you do that DNA extraction, of course, you get all of the DNA in the genome, in your case, it would be about 7 billion base pairs. In the case of an insect, it might be 500 million base pairs. And we just want to read 500 of them. And you can think of the whole genome as sort of a book of life. And we want to read just one of those pages. So to do that, we use the polymerase chain reaction, which basically Xerox copies a selected page in that much larger book of life. And that prepares us then, once we've got many copies of it, prepares us for doing the next stage, which is sequencing the DNA. And that delivers the barcode record.

CURWOOD: Now, when somebody identifies a species and generates that barcode using these techniques, where can that information go from there? And what can it do?

HEBERT: Well, I mean, of course, that was the first thing we saw coming, was a very large number of records. So, it was important to develop an informatics platform that's now been adopted by the global community. It's a platform called the Barcode of Life Data System, acronym 'BOLD'. And basically, all of the data from each individual specimen go into that database, together with an image of the specimen and where it was collected, and by whom; all of the details. And so, let's say you begin by sequencing an American Robin, next time you were to encounter a feather on your lawn that happened to derive from that bird species, you would get a connection to that reference sequence in the bar code library, in BOLD. Now, if it came from a bluejay, and there was no reference sequence in the library, you'd be in a bit of problem. But the idea is to build up this reference library, so it has representative sequences for every species on our planet. And that's what we're in the process of doing now.

CURWOOD: Now, of course, this is a very handy approach in academia with nice big laboratories. What about somebody who's in the field? How useful is this?

HEBERT: Well, you can go in the field, as we have recently, in Kruger National Park with the rangers in that park, who normally are involved in suppressing poaching of rhinoceroses, joined in a massive collection program that gathered up about a million specimens from that largest national park in South Africa. So they gathered the specimens, they worked in the field, did all the field work, and then they dispatched them to our core facility. And we then translated those specimens into barcode records and built a DNA barcode reference library for Kruger National Park. So that's one way you can do it. But in the future, it's going to be certain that you're going to be able to take a walk through the woods with your kids or your grandkids, and see an organism, and simply touch it, and from its DNA barcode sequence, gain its identity, and everything else that humanity knows about it. And we're heading there within the next 10 to 20 years for sure.

CURWOOD: What's your biggest surprise now, in this project? What have you found or what have other researchers found using DNA barcoding that we just never would have understood or been many, many years before we could understand?

HEBERT: Well, I think there are a few surprises. I happen to be a bit passionate about insects, the most diverse group of life on our planet. And for a very long time, it has been argued that beetles were the most diverse group of insects, the most diverse order of insects. In fact, the famous British biologist Haldane was, this was one thing we could learn about the mind of God: by studying life on our planet, that he had an inordinate fascination with beetles. But it turns out that's wrong. Barcoding revealed that flies are by far the most diverse group of insects. And more so, that one particular group of flies, gall midges are hugely diverse, more diverse than all of the beetles on our planet. So, this was something that hadn't been observed, despite 260 years of scientific investigation of multicellular life on our planet. But it was revealed quite quickly through barcoding.

Paul D.N. Hebert, is the Canadian biologist who developed the technique of DNA barcoding. (Photo: Courtesy of the International Barcode of Life Consortium)

CURWOOD: By the way, give me some examples of where DNA barcoding has found species in places where you just had no idea they were there.

HEBERT: Well, one of the earliest studies that we did in Costa Rica, involved a beautiful iridescent blue butterfly that for the last 200 years, has been regarded as a single species. Had one thing that was a bit unusual about it, it fed on an inordinate diversity of host plants. And when we barcoded that species, we found that in fact, it was 10 species, not one. There's a lot of hidden diversity, even within the large species that we share on this planet, when you move down to the small stuff, it's massive discovery.

CURWOOD: Now, the International Barcode of Life Consortium has this mission of identifying each and every species on Earth using barcoding. What is the ultimate goal of the project, do you think?

HEBERT: Yeah, well, I think there is this curiosity element. You know, we really do want to understand the diversity of life that... the planet, the organisms we share this planet with. However, that knowledge, creating that reference sequence library for all species on the planet, is going to place us in a position where it's going to be possible for us to set up global bio surveillance system. So we can track what humanity is doing to the other life forms. So, just like in the 19th century, we began to record weather. And we're now... have the information that supports global warming and change and it's leading to shifts in the way we power our society. We're taking adaptive actions to prevent further global warming. I see detailed information on the shifts in biodiversity that are happening on our planet, motivating humanity to take the action needed to do better. And I think the other major contribution will be setting aside all of these DNA extracts, so we can read the books of life at our leisure. Most species, when they go extinct, aren't like the dodo, where you could go and find bones 200 years later, or the mastodons. Most species when they become extinct, are a smudge on the forest floor for a day or two. And that book of life is gone. So I think humanity will be very grateful that we've preserved the books of life for reading, and hopefully have changed human behaviors so the species aren't just in a freezer. They're sharing the planet with us into the future.

CURWOOD: Paul Hebert is a molecular biologist at the University of Guelph in Canada, and science director of the International Barcode of Life Consortium. Thank you so much, Paul, for taking the time with us today.

HEBERT: Cheers. Thank you very much, Steve.

Related links:

- The International Barcode of Life Consortium

- Science Magazine | “$180 Million DNA ‘Barcode’ Project Aims to Discover 2 Million New Species”

[MUSIC: Tom Roush, “Home On The Range” on Silver Threads Among the Gold]

Bison and Sustainable Land Management

Bison tend to graze on a wide variety of plants in open areas and encourage a diversity of grasses on the arid Great Plains. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Ah, home on the range… Two centuries ago the Great Plains of North America from Canada to Mexico teemed with prairie dogs, pronghorn, and bison or buffalo, and inspired that iconic song. Today those herds of bison are few and far between, after massive slaughters and much grassland went under the plow. But from Alberta to Chihuahua, bison are coming back, and Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb visited a ranch in Janos Mexico that’s part of the effort to restore them.

[WIND SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: The great plains of Mexico are dry, mostly tan in color. But a bird’s eye view reveals dark brown squares of tilled land waiting to be planted and bright green circles - irrigated fields of wheat, corn, or alfalfa. But for the spine of the Sierra Madre mountains, northern Chihuahua looks a lot like Kansas.

I’m here to check out the El Uno bison ranch near the town of Janos. Flora Moyer greets me when I arrive.

FLORA: Welcome, welcome!

BASCOMB: Thank you, so windy today!

FLORA: Janos is where the wind was born apparently.

BASCOMB: Really? It feels that way.

FLORA: So they say. So we have been weathering lots of wind these last few days. I’m Flora.

BASCOMB: Flora, I’m Bobby. Nice to meet you.

BASCOMB: Flora is the coordinator of the private lands conservation program for the non-profit Fundo Mexico, the Mexican Fund. Holding her cowboy hat on her head so it doesn’t fly away, she leads the way out of the wind and into the El Uno ranch. Flora says it’s always this windy here.

Bison frequently roll on the ground and create small basins that hold moisture and serve as microhabitats for a variety of plant and animal species. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

MOYER: But what has been increasing are the dust storms. And so you’ll see these sort of these dirt devils all around. Yesterday, you couldn't see the entire mountain range that's on the other side of the valley, which is not that far away, and pretty massive. And it just was completely disappeared behind the dust clouds.

BASCOMB: Those dust clouds are a result of years of cattle grazing and water-intensive agriculture on semi-arid land.

MOYER: These processes of desertification that come from the, mismanagement of the land and the overgrazing that has resulted, so you have all this barren land, but also, because of all of the agriculture that has been brought in has loosened up all the soil that doesn't have vegetation for large periods of time. It's just been more and more that there are these events where the valley is just filled with dust.

BASCOMB: But Flora says Fundo Mexico acquired this property with the hope of addressing the erosion problem and at the same time promoting sustainable ranching.

MOYER: The goal of this property is to create a demonstration site where we set out from the beginning to have a working ranch operation that has conservation goals integrated into its operation. So we really want to be an example that neighboring ranches or other properties in the area, can look at and say, okay, if they can do it, then we can do it.

A group of females and calves at El Uno Ranch in Janos, Mexico. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Like many ranches in the area, El Uno makes money from cattle ranching. But cattle, introduced by Europeans, can degrade land in ways their native cousins, bison, do not. Bison historically ranged from Southern Canada to Northern Mexico. West to the Rocky Mountains and possibly as far east as Florida and New York. Roughly 30 million bison roamed North America before white settlers arrived. By the turn of the century there were fewer than 600. El Uno is hoping to help the species recover while sustainably managing the land and turning a profit.

A tall order, but Pedro Calveron is up to the challenge. He’s the self-described ranch bison whisperer.

CALVERON: If you don’t know how to talk bison it really becomes a problem.

[TRUCK SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Pedro has a short black beard and wears a long sleeve plaid shirt with a brown handkerchief tied around his neck. His official title is ranch manager and I’m tagging along as he drives a pickup truck around the ranch to check on the herd. At more than 45,000 acres, El Uno is three times the size of Manhattan so we drive for a while before we find a large group of females and calves.

CALVERON: The one who is laying has his calf right in front of her. And the other one is nursing their calf.

BASCOMB: We get out of the truck to get a closer look.

[DOOR SOUNDS]

CALVERON: OK, so just be quiet and don’t look the herd to the eyes.

BASCOMB: Any other advice?

CALVERON: No, no just stay with me.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: He pauses to tie his cowboy hat under his chin so it won’t fly off in the wind. We walk through ankle high brittle yellow grass towards the herd of one-ton animals and their babies.

Part of the El Uno Bison herd. (Photo Bobby Bascomb)

CALVERON: Can you see the bunch of newborns here?

BASCOMB: Yeah, they’re tiny. How old are those, you think?

CALVERON: The darker ones, more than a month and the lighter ones around a week.

BASCOMB: Pedro says bison have two advantages over cattle when it comes to managing the land sustainably. First, bison tend to lay down and roll on the ground, which creates bison sized basins on the land, and that keeps more water on the dry landscape.

CALVERON: The moment that you have moisture, or rain, you are able to maintain the moisture in those basins.

BASCOMB: And those moist basins can create microhabitats for a variety of animals including burrowing owls. Some wildflowers and grasses that pronghorn antelope feed on also like bison basins. And Pedro says he’s noticed another advantage that bison have over cattle.

CALVERON: They are less selective than the cattle to eat vegetation so they’re going to graze more this kind of grass more shrubs than the domestic cattle.

BASCOMB: They eat the grass more indiscriminately so I would guess that you would have more different types of grass as opposed to a monoculture growing up.

CALVERON: Yup.

BASCOMB: So, do you think the bison encourage a diversity of grass locally?

CALVERON: Totally.

BASCOMB: Pedro’s observations are backed up by many studies comparing cattle and bison. Laura Paulson is an independent consultant focused on sustainable ranching policies. She used to work at El Uno Ranch and says bison tend to roam more than their cattle cousins.

PAULSON: The bison make very large movements across the land throughout the day for grazing instead of staying in one area like cattle do.

BASCOMB: Cattle tend to congregate near trees and water sources, and can lead to erosion in riparian areas. Bison prefer to graze in open areas and travel far in a day, creating those microhabitats, and leaving their fertilizer behind.

PAULSON: And then, generally speaking, bison are considered hardier, more adaptable animals. They can withstand heat and cold, better than cattle. And in fact I would say that they are the perfect North American animal if there is one.

BASCOMB: Indeed, President Obama declared bison our national mammal in 2016. And Laura says bison have at least one more advantage.

Pedro Calveron is the El Uno Ranch manager and staff “bison whisperer.” (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PAULSON: Research indicates that bison meat is leaner and more nutritious than beef.

BASCOMB: Bison meat is lower in fat and calories than beef and higher in protein. In the US bison are considered livestock. There are a few wild herds, mostly in public lands like Yellowstone and Wind Cave national parks, where roughly 5,500 bison still roam free. But private ranchers graze far more bison as livestock. Ted Turner alone raises more than 50,000 bison, some of which end up on the menu at his restaurant chain, Ted’s Montana Grill.

South of the border, in contrast, bison are managed as wildlife and their sale for consumption is prohibited. It seems counterintuitive but Laura says there is a case to be made for opening up new markets for bison meat in order to save the species.

PAULSON: These are some of the public policy issues that do need to be looked at closely and really figured out how can they be modified in a way that would be a win win for both the conservation authorities in Mexico as well as private landowners who are interested in working with bison?

[WIND AMBI FROM EL UNO RANCH]

BASCOMB: And that’s a question that Pedro at El Uno in Mexico is struggling with. He says the ranch can support up to 800 bison. But they plan to stop breeding them at just half that number and split the ranch evenly between bison and cows. They need to turn a profit to maintain the ranch and demonstrate to other ranchers how that can be done sustainably. But they also want to be leaders in the bison conservation movement.

CALVERON: We are right at the limit of the distribution at the South. So the genetic of the bison here in El Uno is already adapt to this desert ecosystem. So, looking at the big picture between Canada, United States and Mexico, and northern Great Plains and everything. If there is more interest or there is more initiatives to create more conservation herds, we are the ones who has the animals ready to be part of those conservation herds because they already adapt to these conditions on the desert.

BASCOMB: So, you already have some genetic diversity to offer to other ranches.

CALVERON: Yes.

BASCOMB: El is Uno is currently home to 206 bison and they expect have about 230 by the end of the calving season. But unless they can find a market for bison they will have to stop breeding far short of what the ranch could support. Economic necessity demands they continue running cows even though they can be degrading for the land.

For now, Pedro says they’ll continue experimenting with the best ways to manage their herd with the hope of conserving bison and impacting sustainable land management far beyond this one ranch.

For Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb at the El Uno ranch in Chihuahua, Mexico.

NOTE: This story has been updated to reflect that El Uno ranch was donated to Fondo Mexicano by the Nature Conservancy.

Related link:

El Uno Ranch on Facebook

[MUSIC: Mickey Raphael, “Home On The Range (Instrumental)” on Red River Valley, Cumberland Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Don Lyman, Lizz Malloy, Mark Seth Lender, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, iTunes and Google play- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - PRI’s Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy and from Carl and Judy Ferenbach of Boston, Massachusetts.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRI, Public Radio International.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth