April 10, 2020

Air Date: April 10, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Air Pollution Worsens COVID-19

View the page for this story

The novel coronavirus is deadlier to people who have years of exposure to high air pollution, emerging research finds. Dr. Aaron Bernstein of Harvard’s Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, speaks with Host Steve Curwood about the link between air pollution and severe cases of COVID-19, and also notes people of color are disproportionately exposed to air pollution. Dr Bernstein also discusses the lifesaving health benefits of climate solutions that also clean up polluted air. (14:44)

Beyond the Headlines

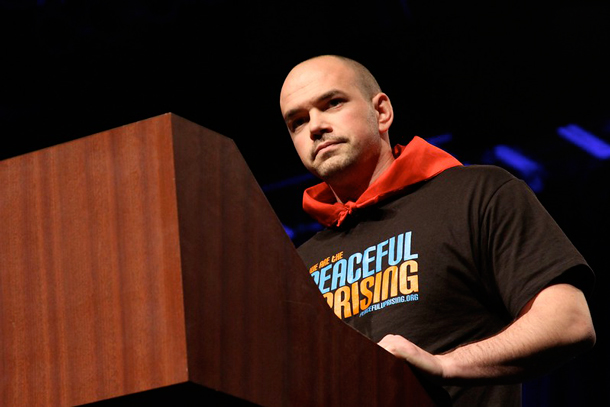

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to take a look at a growing ozone hole in the Arctic. Then the two discuss attempts to build a ferrochrome plant in the US-Canada border town of Sault Ste. Marie, which has already been impacted by polluting industries. In the history vaults this week: the 30-year anniversary of Star-Kist’s announcement it would no longer buy and sell tuna that could harm dolphins. (04:58)

Poetry Month: “One Log Per Visit, Never The Same Log Twice”

/ Susan Edwards RichmondView the page for this story

April is National Poetry Month, and poet Susan Edwards Richmond, a preschool teacher at Mass Audubon’s Drumlin Farm Wildlife Sanctuary, shares a poem about her young students’ wonder at the colorful creepy crawlies they find underneath a backyard log. (02:11)

A Backyard BioBlitz

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Every year, citizen scientists around the world participate in BioBlitzes: brief, intensive surveys of biological diversity over a set area and time. In 2020, social distancing didn't stop over 300 participants in 27 countries from cataloging observations of the world around them a single 24 hours. Living on Earth's Bobby Bascomb, her husband Mark, and daughters Sage and Luna joined inApril 5 and uncovered a multitude of life in their own backyard. (05:18)

Erosion: Essays of Undoing

View the page for this story

Writer Terry Tempest Williams’ latest book, “Erosion: Essays of Undoing”, grapples with the erosion of democracy, science, compassion, and trust, as her beloved Utah red rock landscape faces oil and gas extraction, and the planet faces destructive warming. At a Good Reads on Earth live event, Williams spoke with Host Steve Curwood about how science and Native knowledge alike can guide us on a more sustainable path, and why erosion also creates an opportunity for evolution towards a better future. (19:26)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Aaron Bernstein, Susan Edwards Richmond, Terry Tempest Williams

REPORTERS: Bobby Bascomb, Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood

New research links chronically dirty air with a greater risk of dying from the novel corona virus.

BERNSTEIN: We now have evidence that the death rate increases by 15% for every one microgram per meter cubed of air pollution that people have been exposed to over the long term. You know, people may be much more sensitive to air pollution with disease than we previously understood.

CURWOOD: Also, how to find courage in the face of ecological grief.

WILLIAMS: We're going to be facing some very hard things in the future and I, I hope that we have a consciousness that can rise to this moment. That's the question I have, how do we strengthen one another? How do we find the courage to act? How do we support one another? How do we find the strength to not look away?

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Air Pollution Worsens COVID-19

New York City has been the epicenter of COVID-19 cases in the United States. It is also one of the cities in the United States with the highest levels of air pollution. (Photo: Thomas Hawk, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood at a social distance.

The novel corona virus is more deadly in areas with many years of high air pollution, researchers are now saying. Biostatisticians at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health compared death rates from Covid-19 in 3000 counties with air quality and found that in areas with just a small increase in long term rates of fine particle pollution, 15% more people are likely to be killed by the virus. And researchers at the University of Siena in Northern Italy also suggest there is an association between the region’s long history of high air pollution and the high pandemic death rates. For some perspectives, we turn now to Pediatrician Aaron Bernstein, who is the interim director of the Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment at Harvard, though he did not work on the Harvard study. Since the particulates in air pollution seem to increase the lethality of the corona virus, I asked Dr. Bernstein to start our conversation by explaining just what they are.

BERNSTEIN: Particulate matter air pollution refers to anything that's suspended in the air. So that could be from burning wood, it could be from gravel that's ground up on the ground and put into the air, or even dirt or salt that gets, you know, washed up from the shores into the air or off farms into the air. But it also can come from burning fossil fuels. And it's generally treated by its size. So we say there's particulate matter of 10 microns in diameter, particulate matter of two and a half microns in diameter, and the air rules for the United States, the air quality rules, tend to focus on so-called PM2.5. That's about 1/20th the size of a human hair.

CURWOOD: So why are those particles such a health problem?

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, so lots of research has shown that the more particulate matter people breathe, the more likely they are to die, particularly if you're older. We know that they cause heart attacks and strokes, we know that they cause lung cancer. There's now strong evidence that these particles can also promote the development of type II diabetes, mental health problems, affect the developing fetus, so, may see poorer growth and maybe early birth. And there's increasing evidence that they may be damaging brains: may be a cause of dementia, may be a cause of some disorders in children we see, like autism. But the bottom line is particulate matter's just generically really bad for us. And in many places in the world including the United States, the major source is from burning fossil fuels. In other places, where people are using indoor cookstoves, for instance, and burning wood or dung or other things in their homes, that's a major source. And all told, particulate matter in the world is killing like somewhere between seven and 10 million people every year, mostly in Asia. And it's, you know, in the top 10 causes of death, maybe in the top five by some estimates.

CURWOOD: And what are those numbers here in the United States?

BERNSTEIN: So there's probably on the order of 100,000 to 200,000 people who die every year from particulate matter in the United States. That death toll is not distributed evenly across the United States population. If you're poor, if you're African American, if you're Latino, your odds of getting sick and dying from particular matter are much higher than other folks. And, you know, we know that of course, short of death, there are a lot of bad things that happen to people from air pollution. I as a pediatrician know that air pollution can be a major risk for everything from ear infections to pneumonias. And you know, in people who are older, air pollution, particulate matter air pollution can cause heart attacks and strokes.

CURWOOD: And as a pediatrician, I imagine you see a fair amount of asthma.

BERNSTEIN: Yep, we also know that particulate matter is a major both cause, meaning, it would take a child who wouldn't have had asthma and lead them to have asthma. But also, of course, children who already have asthma are more likely to have trouble breathing. And that's also true for adults, adults who have chronic lung diseases who get exposed to particulate matter are much more likely to have a hard time breathing.

Consumption of red meat has been linked to heart disease, colorectal cancer, and type 2 diabetes. A healthy diet is essential when fighting off respiratory diseases like COVID-19. (Photo: Eser Aygün, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: What's the relationship between particulates and climate disruption, climate change?

BERNSTEIN: Well, it's, you know, sort of the same problem. Around 70% of the carbon emissions in the world come from burning fossil fuels. And as I mentioned before, a huge amount of death is happening because of particulate matter air pollution, that also come from burning fossil fuels. And so you know, you get a win-win there. If you get off fossil fuels, you get rid of huge burdens of disease right now; I think that's critical, which is, you know, we don't wait for months or years when you stop burning coal in a power plant and convert it to renewables. The change in health happens right now, and particularly in the places where that coal plant stops burning coal. And of course, that means there's also less carbon emissions, which protects the climate moving forward.

CURWOOD: Now explain to me why air pollution then is apparently increasing a COVID patient's risk of dying from the disease, as some recent papers have indicated.

BERNSTEIN: Yeah. So had you asked me that question a couple weeks ago, I would have said, well, we have lots of evidence from other even viral infections -- including SARS, which is sort of the first cousin of COVID; it's also a coronavirus, it also came into people from bats -- that particulate pollution, particulate matter air pollution, is a major reason for people to get sick and potentially die from these infections. But in the last week, we've had evidence now specifically on COVID in the United States, showing that very small changes in the amount of air particles that people have been exposed to, over the long term, so these are not the day-to-day fluctuations, but this is over many months. So if you've lived in a place with overall worse air pollution, the death rate increases by 15% for every one microgram per meter cubed of air pollution, particulate matter air pollution. Now, to put that in context, you know, in Boston, the air quality right now, the particulate matter levels are about five micrograms per meters cubed. You know, on a bad day, it gets up 15 to 20. Many places United States are 30. But one microgram per meter cubed difference over the long haul, right, this is over extended periods, leading to a 15% increase in the death rate from COVID. And that's, by the way, doing statistics to try and account for the health status of the people who are affected, so whether you are sicker at baseline or not. They also in this study looked at people's access to health care, so were there hospitals available to you or not? They looked at people's socioeconomic status, so whether you're rich or poor, and a host of other things that of course, should matter to whether someone's likely to die. And even accounting for all those things, they still found that these small differences in air pollution matter to whether or not you're going to die from this disease.

CURWOOD: So we've seen, of course, just horrific death rates so far in places like New York City, Northern New Jersey, seems to be a question of what might be going on in Louisiana and in Michigan. In many of these places it's been tied to ethnicity, it's been tied to the African American community, it's been tied to the Hispanic community. What's going on there, do you think?

New York National Guard soldiers delivered 19,000 pounds of food to families under mandatory quarantine in Albany, New York. (Photo: Senior Master Sgt. William Gizara, Flickr, New York National Guard, CC BY ND 2.0)

BERNSTEIN: So one of the, you know, guesses about what's going on there is that for one thing, many minority communities in this country do not have equal access to health care at baseline, meaning if they have a little bit of heart disease, they might not have the same level of care as other folks. And so it's possible that some of this is reflective of barriers to care, inequality in access to care, and other social determinants of health, that can drive whether or not people might live or die. But, you know, this new evidence, and frankly, in conjunction with the old evidence, is worrisome because we know that African Americans and Latino Americans are disproportionately exposed to air pollution. There have been many studies showing this. And so, you know, we now have the challenge to sort out whether, in fact, this signal that is emerging, which is minority communities, particularly African Americans, potentially Latinos, are at increased risk of dying because of air pollution in their communities. You know, if that turns out to be the case, it would be yet another kick in the pants around why, frankly, climate actions are so important. You know, I've been saying for the past several weeks that climate actions are pandemic prevention actions. And a lot of folks I think, understandably get rankled by that, how can you be talking about climate change when people are dying of an infectious disease right now? And my answer to that is pretty easy, which is, if someone's having a heart attack, and they're getting their, you know, heart reperfused with blood, you know, you're not talking about what they're eating and whether they're smoking and whether they're exercising when they're on the table getting their blood vessel opened. And that's probably because they're asleep, by the way. But the moment they're awake, there's someone in that room saying, you know, we've got to do better to prevent this. And what we know now about COVID, and this is true not just with the air pollution piece, but it has to also do with our diets. We know now that our health, the population health of people in this country, is a huge factor in how we deal with something like COVID. So air pollution may matter, our diets may matter; so there was an op-ed published in the New York Times a week or so ago by colleagues of mine at Boston Children's, saying, you know, we are not healthy enough to go back to work, because of our diets and the rates of obesity in this country and how we know that the rates of mortality from COVID are heavily dependent on pre-existing medical conditions, the lion's share of which are preventable through dietary changes, and we know of course, that eating, for example, more plants, less red meat is enormously helpful for our health right now. And also, of course for the climate.

CURWOOD: What kind of impact on public health do you think the Trump administration's decisions to indefinitely relax the enforcement of certain environmental regulations, including air pollution, what could this have right now in the midst of the coronavirus, do you think?

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, it's hard to know, it's a good question. A lot of people have been really concerned about the EPA decision to essentially allow polluters to not really pay so much attention to their pollution. In light of the research that came out this week, I think there's heightened concern here, because if even small increments in air pollution occur, especially in communities that we know are at risk, that decision now looks a little less wise. You know, I do my best to operate in good faith that the folks who are trying to steer us right now are doing the best job they can. But I think that what we, we, we owe it to everybody to do is to try and use science as best we can to make the case as to why certain decisions might be changed or why certain decisions should stand. And I think this is a very good example, which is, we now have evidence people may be much more sensitive to air pollution with disease than we previously understood. Does that matter to the decision of the EPA? I would say it absolutely does. I should note that for the last three years, air pollution in the United States has gotten worse, for the first time in decades. Not clear why that is, but you know, this is concerning because from a regulatory standpoint, there's no reason for that to happen. So we already have this uptick in air pollution; now we have evidence that air pollution may be more risky; and we potentially have an EPA that's saying, Let's not pay as much attention to air pollution. That would certainly give me pause, particularly for those folks in our communities that are most at risk.

An environmental justice event in Detroit, protesting the high levels of air pollution. Detroit is one of the cities hit the hardest by the coronavirus pandemic. (Photo: Marcus Johnstone, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Ari, before you go, what advice do you have as a physician to people going through this COVID pandemic -- ways beyond the usual things we hear to enhance our own health and that of our children and our elders, people that we care about.

BERNSTEIN: Yeah, it's a great question, Steve. Let me try and answer it in the domain that's closest to my own, which is, you know, what do you tell children, who've been kept out of school and kept away from friends and it may be hard to understand what's going on, in some ways. Because all children sort of get infections, many of them had ear infections, throat infections, and they're sort of, you know, they get over them. And this is just so wildly different. So for children out there, and you know, for their parents and grownups who are listening, you know, I think there's a couple of important things to know. One is that it's important to take care of ourselves right now. That doesn't mean bingeing on french fries. [LAUGHS]

Aaron Bernstein is the Interim Director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, a pediatrician at Boston Children's Hospital, and an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. (Photo: courtesy of Harvard School for Public Health)

What, what it does mean is keeping with the routines as much as we can, that, that happened, you know, before we were asked to stay home. And to the extent we can engage with our friends through computers and the Internet, to the extent that we can continue our schoolwork, to the extent we can maintain those routines, that's great. I also think that, you know, the things that we're being asked to do, washing our hands all the time, keeping our physical distance from others, are good for protecting ourselves and our families. But they're also, of course, done primarily to protect people most at risk, right? So most children are not affected as severely and they may not have symptoms. And so one might reasonably have said, Well, I'm not really protecting myself, if I'm a child. The real reason is we're protecting people who are more at risk. And you know, there aren't a lot of silver linings in this mess. But one of them could be that we cultivate a cohort of children here, who really get that we do things not always for ourselves. That sometimes, the right thing to do, which may not be something that we would do for ourselves otherwise, is important to do because it saves lives. It keeps the people in our communities healthy. That we make decisions that matter beyond ourselves. And there's been no experience in recent memory that has made it clearer than this one, that our health is absolutely tied to the communities we live in and to the living world, and that we simply must move forward on that basis if we want to make sure that our children grow up to have the opportunities and health that so many of us have enjoyed. And so that's the kind of thing I think is really important to talk to our children about these days.

CURWOOD: Aaron Bernstein is the Interim Director of the Center for Climate, Health, and the Global Environment at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a pediatrician at Boston Children's Hospital. Ari, thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

BERNSTEIN: Thanks for having me, Steve.

Related links:

- NYTimes | "New Research Links Air Pollution to Higher Coronavirus Death Rates"

- New England Journal of Medicine | "Exposure to Air Pollution and COVID-19 Mortality in the United States"

- Environmental Pollution | "Can Atmospheric Pollution be Considered a Co-Factor in Extremely High Level of SARS-COV-2 Lethality in Northern Italy?"

- CNN | "Los Angeles Has Notoriously Polluted Air. But Right Now It Has Some of the Cleanest of Any Major City"

- The Atlantic: A new report from the Environmental Protection Agency finds that people of color are much more likely to live near polluters and breathe polluted air—even as the agency seeks to roll back regulations on pollution.

- Harvard Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment (C-CHANGE)

- About Aaron Bernstein, MD

[MUSIC: Orchestra for Amistad, “Cinque’s Memories Of Home” on Amistad – Original Motion Picture Soundtrack, by John Williams, DreamWorks]

CURWOOD: Coming up – Tips for engaging children with the nature right in our own backyards. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Barefoot, “Arica” on Gardens Of Eden, by Barefoot, Putumayo World Music]

Beyond the Headlines

A steel mill in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario has emitted high levels of carcinogenic pollutants on both sides of the Canada-United States border. (Photo: David Wilson, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: It's living on Earth, I'm Steve Curwood.

It's time now to take a look beyond the headlines. And to do that we talk to Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. On the line now from Georgia, Atlanta. Hey there, Peter, what's going on?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Steve, I want to start talking about something that sounds like really bad news. It's not good news, but it's not as bad as we might think.

CURWOOD: Okay, not as bad as we might think, go on.

DYKSTRA: In the journal Nature, scientists have reported that there is an ozone hole over the Arctic. This is only the third time there's been an actual ozone hole since we started measuring. The other two are in 1997 and 2011. By the time this one is done, the scientists think it's going to be the biggest ever.

CURWOOD: So you're saying it's not such horrible news? Because why?

The Boreal Northern Lights in the Arctic Sky. The newly discovered ozone hole in the Arctic was formed by a strong polar vortex, leading to freezing temperatures in parts of the atmosphere. (Photo: Fiona Paton, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Because since the Montreal Protocol, the treaty on ozone depleting chemicals came into effect in the 1980's the ozone hole at the South Pole and ozone conditions at the North Pole have very gradually begun to repair themselves. And one of the reasons that we had this massive international agreement that resulted in environmental improvement is that it was supported by two conservative icons in world politics, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher.

CURWOOD: Well, conservatives can be conservationists as well.

DYKSTRA: If they want to be.

CURWOOD: Hey, what else do you have for us this week, Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, at the EHN page, we have a story from Hilary Beaumont. It's about a pollution problem on the US Canadian border. The town of Sault Ste. Marie, half of Ontario half across the river in Michigan. There's a big polluter on the Canadian side Algoma Steel, there are plans to build what's called a ferrochrome plant to make chromium on the American side. The waste from these plants has included hexavalent chromium, it's a toxic material that's a known cancer causer. And in this case, it's in an area where there is a cancer cluster. And the company says this plant will be cleaner than other hexavalent chromium sites in the past, but residents are concerned.

Picture of Sault Ste. Marie International Bridge which connects two cities by the same name. It has a long history of steel and chromium operations. (Photo: CMH2315FL, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Well, that hexavalent chromium is the carcinogen at the center of the Erin Brockovich movie, right?

DYKSTRA: Well, you're absolutely right. But here's the thing. There aren't that many major Hollywood releases about the environment. And hexavalent chromium is actually at the center of two of them. Erin Brockovich and also a civil action best selling book that became a hit movie. That one is about a tannery site in Woburn, Massachusetts. There's also an old tannery site at the Sault Ste. Marie Superfund area, and in the Canadian and Michigan location. The’re astronomic cancer rates on both sides of the border, including those linked to the steel mill.

CURWOOD: So how do folks feel about this?

DYKSTRA: Well, a lot of folks feel that they've been a sacrificed zone to industry already, there's a lot of mistrust about this new ferrochrome plant coming in. The plant promises to provide 300 jobs if it's built. It's an economically struggling region. A lot of residents are saying they already deal with pollution and cancer. So at what cost are those 300 jobs going to come?

CURWOOD: Excellent question to ask. All right, Peter now's the time that we turned a look back in history and I'm wondering what you're looking at today.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, here's something that I looked at, and it's really hard to believe this is 30 years ago already. But on April 12 1990, StarKist, the tuna company subsidiary of Heinz foods, announced that it would no longer buy and sell tuna that's caught by methods that also cause the deaths of thousands of dolphins in purse seine nets.

CURWOOD: Yes, the birth of the dolphin safe tuna.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, StarKist was a pioneer. The reason that they were a pioneer is that their executives were swayed by video shot by an activist named Sam LaBudde. He crude aboard a tuna sauder as a cook, basically another movie titled sleeping with the enemy almost and he videotaped dozens of dolphin carcasses being hauled in with the tuna catch. It appalled people, it turned the corner for this major tuna processor and Sam LaBuddie's courage won him the Goldman Environmental Prize in 1991.

Purse Seine fishing methods are dangerous for dolphins and often result in their unintended deaths. The 1990 Dolphin Protection Consumer Information Act resulted in the “dolphin-safe” labeling campaign, which requires independent observers aboard tuna fishing boats to ensure dolphins were not being killed during the tuna harvest. While not completely successful, there has been a decrease in dolphin deaths while tuna fishing. (Photo: Ed Dunens, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: And really struck a blow for using a clandestine video but wouldn't you say this was literally at the risk of his own life?

DYKSTRA: It was one of the most courageous individual acts of environmental activism in history. And it also taught a lesson about using video.

CURWOOD: All right, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra, is an editor with Environmental Health News as ehn.org and dailyclimate. org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more about these stories on the living on earth website at loe.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “‘Them Plants are Killing Us’: Inside a Cross Border Battle Against Cancer Pollution”

- Read more about the study on the big rare ozone hole opening in the Arctic

- Read more about Sam LaBudde and his activism

MUSIC: Christian McBride, Nicholas Payton, Mark Whitfield, “Dolphin Dance” on Fingerpainting: The Music Of Herbie Hancock, The Verve Music Group]

Poetry Month: “One Log Per Visit, Never The Same Log Twice”

Rolling over a log in the backyard can be a wonderful way to connect with nature from the safety of your own home. (Photo: Sara, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: April is national poetry month, and for some inspiration during these times when we need to stay close to home, we turn now to outdoor educator and poet, Susan Edwards Richmond. She teaches at a nature-based pre-school west of Boston, and .

here is she is with her poem, “One Log Per Visit, Never the Same Log Twice.”

RICHMOND: So when I met with my preschool classes at Drumlin Farm Wildlife Sanctuary, we often talk about guidelines for respectfully entering places where animals live. And there's this one nature play area where there's a lot of big logs arranged in a campfire circle. And in a previous class, we had talked about what might live under these logs that there were habitats there. So the kids were very excited to start rolling log after log to see what might live underneath. So we sat down and we talked and we came up with some rules for ways to minimize our disturbance of the animals in their homes.

[READING]

"One log per visit, never the same log twice."

In the dark and damp, deep places beneath

the surface of our play, lurks a lesson

in gratification deferred. Shadow

creatures blue as caves and midnight, or red

as blood worms, mud worms meander, spotted

with toxicity. Some days only ants,

a spider hiding a sac. Other days

millipedes curl or centipedes scurry

or ubiquitous sow bugs crawl along

bark and roots and offered arms. But the prize

awe is the vertebrate who at first glance

appears as wet and spineless as a slug,

but on second, unwinds in graceful curves,

spreads tiny frog feet and paddles the earth.

Susan Edwards Richmond teaches at an environmental preschool program at Drumlin Farm, a Massachusetts Audubon wildlife sanctuary in Eastern Massachusetts. (Photo: Courtesy of Susan Edwards Richmond)

CURWOOD: Susan Edwards Richmond reading her poem, “One Log Per Visit, Never the Same Log Twice.” Susan is also the author of the children’s book, Bird Count.

Related links:

- Read more about Susan’s work at her website

- Listen to a previous Living on Earth story with Susan Edwards Richmond

- Susan's poem will be published by Hawk & Whippoorwill Press in the chapbook "Songs for Salamanders"

[MUSIC: Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit, “Only Children”, Single, Southeastern Records]

A Backyard BioBlitz

Mark Fabian holds a bug for his daughters Luna and Sage to examine. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: On April 5th BioBlitz brought together 300 plus participants at a social distance in 27 countries who took photos of plants and animals close to home and used the iNaturalist app to identify and log in those observations for scientists. Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb took part along with her husband, Mark, and daughters Sage and Luna, aged five and two. They got started at a kitchen window with a view of their bird feeders.

LUNA: Can you sit next to me in another chair?

MARK: Yes.

SAGE: Looking for birdies.

BASCOMB: What do we see?

SAGE: A woodpecker.

BASCOMB: How do you know it’s a woodpecker?

SAGE: Because it pecks.

A woodpecker at the Bascomb-Fabian family bird feeder. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: I see another animal under the other bird feeder. What do you see, Luna?

LUNA: I think that’s a squirrel

BASCOMB: Well, let me get a picture of the squirrel so we can share it on the app.

SAGE: So cute

BASCOMB: Now I’m going to hit the green share button. Okay, I loaded a picture of the squirrel and it gives me a few suggestions for what kind of squirrel it could be. But what do you think? Which kind of squirrel do you think it looks like of these pictures here?

SAGE: Let's see. Put it put your phone on the window.

BASCOMB: Oh, you want to hold it closer. Okay. Now what do you think?

SAGE: That one.

BASCOMB: Eastern grey squirrel? Yeah, I think you're right. Why do you think it looks like that one?

SAGE: Because it's in the yard.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's in a yard.

SAGE: And it looks just the same!

BASCOMB: Oh, look, look look. What's that one?

LUNA: I think that’s a red bird!

BASCOMB: A red bird. What kind of birdy is that?

SAGE AND LUNA: A cardinal, cardinal!

SAGE: Is it a boy?

BASCOMB: Yeah, I think it is. Why do you think it’s a boy, Sagey?

SAGE: Because it’s much more prettier.

BASCOMB: The boys are much prettier, are they brighter red?

MARK: We have a bunch of species here. I think there’s a chickadee there. There’s some type of thrush down there. We’re not getting pictures of them, it’s happening too fast.

LUNA: I want to go outside and look for more animals.

Luna holds some worms out for the camera. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Ok, that’s a great idea.

LUNA: Let’s go.

BASCOMB: Alright, let’s get our boots on.

LUNA: I need help getting down.

SAGE: Luna, come on! I got my boots.

BASCOMB: You’re all set.

door opens SFX walking down the steps

SAGE: We should start in our back yard.

BASCOMB: Ok, let’s start in our back yard. That’s a great idea.

[chicken sounds]

SAGE: Hey Luna, here’s the chickens!

[GATE SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: What are they having for treats today?

LUNA: They’re having peanut butter and bugs!

BASCOMB: Peanut butter and bugs?

LUNA: yeah.

BASCOMB: Alright, well these count. Let’s take a picture.

[CHICKEN SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: What should we do next, honey?

SAGE: Follow me

[WALKING SOUNDS]

SAGE: Keep your eyes open, Luna!

BASCOMB: Luna, what do you see?

LUNA: A robin.

BASCOMB: You see a robin?

SAGE: Luna, do you want to look under a log?

Sage investigates a creepy crawler. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

LUNA: Yeah.

SAGE: Let’s do it. Come on.

[LOG ROLLING SOUND]

SAGE: I want to hold it!

LUNA: I want to hold it!

FABIAN: I don’t know if you want to hold that actually it might bite.

SAGE: No, I remember it doesn’t bite.

FABIAN: Here’s a worm for you, Luna.

LUNA: A worm, it’s so cute.

SAGE: Luna, worms are good for our garden because they make more soil.

SAGE: Let’s roll the log back and give the wormies their home.

LUNA: There’s another log over there! I want to turn it.

SAGE: 22:06 A worm!

LUNA: I want to hold it. I want to hold it!

MARK: Oh, there’s a creepy crawly right there.

LUNA: I want to see!

SAGE: Creepy crawly, creepy crawly!

MARK: It’s very creepy crawly, I don’t even want to be holding it myself. They’re not scared by it at all.

BASCOMB: No, they’re not.

SAGE: I love you creep! cutie baby, cutie baby! You tickle too much!

BASCOMB: Does it tickle your hand?

LUNA: I want to hold it, I want to hold it!

BASCOMB: Look girls, what’s that in the tree?

SAGE: What?

Some of the earthworms discovered in the Bascomb-Fabian backyard. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: You see that bluebird there in a tree, it just flew down to a bush.

[BLUE JAY CALLING]

MARK: That’s a Blue Jay calling actually. I can hear it calling. There’s a cardinal in the tree too.

BASCOMB: Ok, what should we do now Sagey?

SAGE: I’m done. Let’s go inside and get a treat!

BASCOMB: And get a treat?

SAGE: Yeah!

BASCOMB: Was this fun?

SAGE: yeah!

LUNA: It was fun giving the mama chickens their treats.

BASCOMB: Well, let’s head back in.

[WALKING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb and her family, Mark, Sage, and Luna, who submitted 17 entries for the bioblitz. For pictures of some of the creepy crawlies they found visit the Living on Earth website LOE dot org.

Related links:

- The iNaturalist Website

- Listen to Living on Earth’s coverage of the 2019 City Nature Challenge, an international bioblitz

[MUSIC: Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, “There Ain't No Bugs On Me” on Not for Kids Only, Acoustic Disc]

CURWOOD: Coming up – how one can still gain while losing. Author Terry Tempest Williams is next on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration. UTC companies such as Otis, Carrier, Pratt and Whitney, and UTC Aerospace systems are helping to move the world forward. You can learn more about United Technologies by tuning into the Race to Nine Billion podcast; listen at racetoninebillion.com.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Tommy Emmanuel, “Windy & Warm” on Endless Road, Favored Nations]

Erosion: Essays of Undoing

Castle Valley, the home of Terry Tempest Williams. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

In these times it may seem the whole world is eroding before our eyes. But grappling with profound loss, uncertainty, and change is nothing new for writer Terry Tempest Williams. Her 1991 memoir Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, set her searing exploration of grief and courage in the arms of nature. Now almost thirty years later Terry has written, Erosion: Essays of Undoing that mourn the erasure of public lands as well as personal losses. As a Writer-in-Residence at the Harvard Divinity School, Terry Tempest Williams divides her time between Cambridge, Massachusetts and Castle Valley, Utah, nearly a mile above sea level on the Colorado Plateau. She joined us at a Good Reads on Earth live event in Cambridge, thankfully before physical distancing made such gatherings impossible.

[APPLAUSE]

CURWOOD: So let's start at Castle Valley, Utah, a place that is so essential to this book. Paint a picture for us, would you, of how it's been shaped by the forces of erosion over these millions of years?

Terry and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood at the “Good Reads on Earth” live event in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in January 2020. (Photo: Jay Feinstein for LOE)

WILLIAMS: Steve, if you and I were having this conversation on our porch, facing south you would see Round Mountain, which is a volcanic plug. It looks like a breast. If you were to see beyond Round Mountain, you would see the La Sals, rising almost 14,000 feet. To the west, is Porcupine Rim. To the north is the Colorado River running red. And to the east with the rising sun is Castleton Tower and a red rock sandstone formation called The Priest and Nuns, created out of erosion. It is a still place; my measure of quiet is to be able to hear the wingbeats of ravens, which we do. And in the spring, certainly the, the songs of the meadowlarks, and at night, coyotes. So it's a wild place. It's also a domesticated place. It's a community of about 250 people, as diverse as you can imagine; but we are known in Moab, Utah, about an hour from us, as the People's Republic of Castle Valley.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

WILLIAMS: And so it's an unpredictable place.

CURWOOD: So, the red rocks are so seductive, aren't they? It's just amazing. Pictures, though, are tough on radio, but I understand you've brought some sound for us, right? It's a sound of the Earth that you can share with us, straight from the desert. Please tell us about what we're about to hear now.

Formations in Arches National Park. Utah’s red rock landscape has been whittled into fantastical shapes over the course of millions of years of weathering and erosion. (Photo: Stephen Walker on Unsplash)

WILLIAMS: Last fall, Jeff Moore, a geologist from the University of Utah, with four graduate students. They've been doing work looking at the porosity of these landforms: buttes, mesas, in particular, arches, hoodoos in the Valley of Gods, and spires. What is their lifespan? What is the process of erosion? How strong are they? They came to Castle Valley, they brought their seismometers; it would be like a stethoscope. They enlisted two climbers, and they put one seismometer at the base of Castleton Tower. Imagine that it is a 400-foot, Wingate Sandstone monolith, one of the largest freestanding spires in the world. The climbers went up that 400 feet, placed a second seismometer on top, and Jeff Moore and his graduate students listened. What they heard, surprised them. Castleton Tower has a pulse.

[SOUND OF CASTLETON TOWER VIBRATIONS]

And it amplifies the energy that flows through them. It can be local: helicopter, traffic, climbers, wind. It can be planetary: the waves of magma, the waves of the Pacific Ocean, earthquake. So with their permission I brought a recording, and see if you can hear the pulse. It's a vibration. It's a resonance. But as you listen, it mirrors our own heartbeat.

[SOUND OF CASTLETON TOWER VIBRATIONS]

The Castleton Tower red rock formation, near Terry Tempest Williams’ home in Castle Valley, Utah. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

Castleton Tower has a pulse. We have a pulse. The earth has a pulse. We took that to Jonah Yellowman, who is the Spiritual Advisor for the Bears Ears Coalition, with Utah Diné Bikéyah, Steve, and I'll never forget him holding that to his ear and just nodding, for three or four minutes. And then he said, "This is what we know." And I think about Western science, geologists; what scientists know, and what native people know. And that we're at this point where those knowledges, those wisdoms, the facts, and the feelings are merging together in a common language. And I think if we could realize that Castleton Tower has a pulse; Bears Ears have a pulse; the ocean, the Atlantic right here, just outside Cambridge has a pulse. Would we treat the earth differently? Would we see ourselves in relationship to the natural world differently?

CURWOOD: I understand you have a passage from your new book, "Erosion: Essays of Undoing" that you'd like to read, Terry; please set this up a bit for us, comes from the very end, I think.

“Erosion: Essays of Undoing” follows in the spirit of other books by Terry Tempest Williams, including “When Women Were Birds: Fifty-four Variations on Voice” (2012), and the environmental classic “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place” (1991). (Image: Courtesy of Sarah Crichton Books)

WILLIAMS: You know, what is erosion? It's a natural process. A scientific definition would be the surface of the Earth, worn down and moved from one place to another, through the force of gravity, and I think movement is the key with erosion. It's different than just weathering in place, of wind, water and time. I have to say, I met a geologist named JoAnn Holloway, who works for the USGS, the United States Geological Survey, and she came up with her own definition, which is "the inevitable process by which rock seeks the ocean." Don't you love that? And then a literary definition: "All souls come here to rub the sharp edges off each other. . . . This isn't suffering, it is erosion." Chuck Palahniuk of Fight Club. So this is the end of the book actually. [READING FROM "EROSION"] "Early in our evolution, we discovered as Homo sapiens through need and necessity that our imaginations can summon power. Fire became a dream ignited that enabled us to feed ourselves and gather round to share stories. Stories are power. Power resides in community. When power is denied and oppresses others, we can resist, and when we resist together, something else can occur, something new emerges. This is the essence of erosion and evolution in human time. In geologic time, transformation can be slow and corrosive, or catastrophic and quick. It may be a cataclysmic moment or it may happen incrementally over time. Deep change requires both. And it is not without its ruptures. It can be associated with devastation or determination. It can also be beautiful. Weathering agents are among us. This is a time of exposure. I dwell in Utah. I am witnessing change. Wind does wear down stone." I think it's that idea, Steve, that we are both evolving and eroding together. Wind does wear down stone. We can resist, we can insist change, together.

CURWOOD: Now a central piece of your theme of erosion in this book is the shrinking of national monuments that the Trump administration undertook at Bears Ears. Now, granted, President Obama waited till the last second in his administration, really, to set aside Bears Ears. But when President Trump came in, the Bears Ears designation shrunk by 85% of its original area. Why did these dramatic changes to these designations affect you so, so deeply? And paint a picture in our minds of what we would see if we were there and of course, the iconic piece that everyone calls Bears Ears.

Bears Ears National Monument has been reduced by 85% of its original designation. (Photo: Bob Wick, BLM, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Bears Ears are two buttes, and they look like bears' ears. They're covered with piñons. They are in the middle of what we refer to as Grand Gulch. It's just outside of Blanding, Utah, very near the Four Corners region, where Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona share a common boundary point. They can also be seen from Monument Valley. They're powerful. I've known them as a child, but I didn't know their history until really, relatively recently. The Diné, Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute, Ouray Ute, many of the Pueblo people. These are sacred lands. Bears Ears is a gathering place for many, many nations. And as Johan Yellowman would say, they're not just protecting Bears Ears for their people, but for all people. President Obama heard their cries, as did Secretary Jewell. It was a handshake across history. It was new trust. And it was this commitment that traditional knowledge would be married with Western science in protecting these very fragile desert lands. Trump came in and gutted it by 85%. And now it's open for business. Uranium mining, oil and gas leases, coal; and Bears Ears isn't the only one affected, and I want to read you the list. Chaco Canyon. Hovenweep. Mesa Verde. Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Canyonlands National Park. Great Sand Dunes. Rocky Mountain National Park. Big Cypress. Grand Teton National Park. Carlsbad Caverns. Dinosaur National Monument. Sequoia National Park. All of these national parks and monuments are being affected by oil and gas leasing, in the parks and outside the parks. This is, 25% of the greenhouse emissions are excavated out of our public lands. If we were to halt oil and gas leases on our public lands, that belong to all of us, and we have to keep in mind before they were public lands, they were native lands, we would stop 450 million tons of climate pollution.

CURWOOD: You point out that there's all this carbon, gets spewed into the atmosphere from the excavation and drilling and extraction from public lands. And tell me about, back in 2016 when you and your husband Brooke decided to take a unique stand against the erosion of public lands and the leasing of public lands for oil and gas development, by purchasing the leasing rights to, what, more than 1100 acres near your home there in Utah, to be developed by the Tempest Exploration Company, LLC. Not for fossil fuels, but apparently for the energy that will fuel the moral imagination, you wrote. What inspired you to do this?

Tim DeChristopher, also known among climate activists as “Bidder #70”, served nearly 2 years in prison for bidding up oil and gas leases on 22,500 acres of public land in Utah’s redrock country, with no intent to pay for them. “Erosion” features a transcribed conversation between DeChristopher and Terry Tempest Williams, about courage, democratic participation, and building a better world. (Photo: Linh Do, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

WILLIAMS: Rage? . . . I think anger goes a long way, and with a name like Tempest, I have to be careful. You know, we belong to a community; eight years prior, a young man, college student at the University of Utah named Tim deChristopher, was part of a protest with the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance, protesting, again, oil and gas leases on fragile desert lands in the Colorado Plateau. It was snowing, he went inside, the lease was going on. He walked in, someone said, "Are you here to bid?" and he said, "Why, yes." Saw these lands that he knew by name, and bid them up to fair market value -- he was an economics student -- as an act of civil disobedience. He served two years in prison for that. Eight years later, Brooke and I were part of a protest with our students at the University of Utah in the Environmental Humanities program, sponsored by many groups in Salt Lake City. We went in to protest. Being an introvert, I went into the shortest line; it ended up not going where the protesters were, but where the oil and gas lease was being held. I found myself sitting next to the CEOs of major oil companies. The protesters disrupted the lease, they were asked to leave; they stayed. They protested again, interrupted, disrupted, and they were asked to leave and they were forced out by the police. I stayed inside. I listened, and watched, the vile language, the misogyny, the racist language. I was appalled. I, too, knew these lands by name in our very county, Grand County in Utah. I also knew that if we waited until after the auction that we could go to the Bureau of Land Management and purchase them on a remnant sale. We went in for the remnant sale, got out the map, saw the key parcels in terms of endangered species and in terms of wilderness value, and we purchased, as you said, 1,120 acres, on our debit card --

Social distancing in the desert. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS]

WILLIAMS: -- hoping to heaven that we had enough to cover it. And it was $1.50 an acre. That, these are our public lands; that's cheaper than a cup of coffee, certainly here in Cambridge. And we immediately formed the Tempest energy company, LLC. The BLM, because we said we would not develop these leases untel science could prove to us that the oil and gas was worth more above ground than below, they took that as an offense, even though many of those men -- and they were men, that I was sitting next to -- had no intention of developing those leases until the price of oil went up; nine months later they revoked our leases. Through the Freedom of Information Act we learned that no leases have been revoked since the 1920 Minerals Leasing Act but ours. We've appealed the decision. It's now before the Board of Land Appeals in the Department of Interior. It's now going on four years. And we're about to put some pressure on, with a very friendly administration right now, as you know.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] So, you repeat over and over again as a mantra, really, as a prayer, the phrase that "we are eroding and evolving all at once," throughout this book, "we are eroding and evolving." Why does that feel so vital, to have a mantra like that?

Terry signs copies of “Erosion” after the “Good Reads on Earth” event. (Photo: Jay Feinstein, Living on Earth)

WILLIAMS: Hope is not a word in my vocabulary, I have to tell you. Faith is. I remember my great grandmother, a Mormon, born in Mexico, said, "faith without works is dead." But in the middle of this erosion of democracy, of decency, of science, all the things that you and I care about, I think back to home. Castleton Tower, The Priest and Nuns, Round Mountain, Porcupine Rim, the Colorado River, Monument Valley, Grand Canyon, Bears Ears. There is beauty in erosion. And that has been evolving over time. So I think it takes us to our essence. It may take us to our knees; our consciousness is evolving. And I think it's not so much about hope as knowing where hope dwells. And I think for me, hope dwells in community. I don't know about you, but there are moments where I wake up and I think I don't know if I can get up today, you know? Despair is very real. But that is the limits of my own imagination. Imaginations shared create collaboration; in collaboration, we create community, and in community, anything is possible.

CURWOOD: So Terry Tempest Williams, we've been asking you a lot of questions tonight. But since you wrote in the preface of, of this book, that it is a book of questions as I recall, I'd like to ask you, what is your question, if you could pick one for this moment?

Terry Tempest Williams at home in Castle Valley. (Photo: courtesy of Terry Tempest Williams)

WILLIAMS: How do we find the strength to face our grief? How do we find the strength to bear our broken hearts, whether it's with what we're facing with a loss of species, with what we're facing with rising tides. We're going to be facing some very hard things in the future. And I, I hope that we have a consciousness that can rise to this moment. That's the question I have: how do we strengthen one another? How do we find the courage to act? How do we support one another? How do we find the strength to not look away? To stay steady? And here's, here's a story. One of the things that Jeff Moore said, Jeff Moore's the geologist that found the pulse with his graduate students. Five of them; they came to our house for a cup of tea. And as we sat there, he said, "Terry, there's something I want to ask you. We have found a piece of information and we don't know what to do with it. We do not have the language to articulate this to where we don't sound soft-headed." Here's what they found, if I understand it. Castleton Tower has gone through millions of years of fractures, shearing, ice, wind, water. There was another tower next to it, it is gone. It has just been whittled and whittled and whittled into this perfect point. What they have found, through algorithms and through their resonance studies, is that it has now achieved a steady state of stability. I mean as a writer, metaphorically that is so exquisite. So if we are in this process of eroding, can we, too, find this steady state of stability, calm, consciousness.

CURWOOD: Terry Tempest Williams is the author of "Erosion: Essays of Undoing"; "Refuge"; and numerous other books, and she's currently a Writer-in-Residence at the Harvard Divinity School. Terry, thank you so much for taking this time.

WILLIAMS: Thank you, Steve.

[AUDIENCE APPLAUSE]

Related links:

- Erosion: Essays of Undoing

- Outside | “This Rock Has a Voice And You Can Listen to It”

- NYTimes op-ed by Terry Tempest Williams | “Keeping My Fossil Fuel in the Ground”

- About Terry Tempest Williams

- About Utah Diné Bikéyah and its advocacy for Bears Ears National Monument

- A coalition of Bears Ears advocates is suing the federal government to restore the national monument

[MUSIC: Hector Hellström, “Charming Spring”, Single]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Thurston Briscoe, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Merlin Haxhiymeri, Candice Siyun Ji, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, and Jolanda Omari.

Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts- and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems. Support also comes from the Energy Foundation, serving the public interest by helping to build a strong, clean, energy economy.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth