August 21, 2020

Air Date: August 21, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Democratic National Convention

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

The 2020 Democratic National Convention featured voices from all across the country, some of whom highlighted climate change as a key concern for this election. But among the hours devoted to the convention’s main events, climate change on the whole appeared to take a backseat to other issues facing the country. Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss how climate change factored into the 2020 Democratic National Convention and the final party platform. (10:05)

"Hadestown" Brings Climate Change To Broadway

View the page for this story

Tony Award-winning musical "Hadestown" retells the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice with a Great Depression-inspired industrial post-apocalyptic setting. The show infuses themes like isolationism, exploitation of workers, and even climate change with New Orleans jazz, folk, and pop music. Director Rachel Chavkin joins Living on Earth’s Bobby Bascomb to discuss the show’s environmental themes. (08:19)

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Many nature writers turn our eyes skyward, towards majestic mountains, open valleys, and wild rivers. But there’s a whole other world beneath our feet, in the dark and hidden places below the Earth’s surface—a place that the British author Robert Macfarlane calls the "Underland.” For nearly a decade, Macfarlane has been venturing into ice caves, exploring underwater rivers, and crawling through catacombs to discover this underworld. He captures these travels in his latest book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey. Robert Macfarlane tells Living on Earth's Jenni Doering what drives him to explore the “deep time” that runs down below. (14:22)

Water Ranching in Mexico

/ Bobby BascombView the page for this story

Bobby Bascomb visits acclaimed land preservationist Valer Clark at her ranch, Cahone Bonito, in Agua Prieta, Mexico. Valer has been a steward of dried up lands in Mexico and the southwestern US since she purchased this property in the 1970’s, and she’s dedicated herself to finding ways to restore and maintain it. Alongside Valer and other experts, Bobby explores this ecosystem, its history, and the simple techniques used to bring it back to life. (13:10)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Rachel Chavkin, Robert MacFarlane

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX this is Living on Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb. A ranch owner in Mexico uses simple techniques to bring water back to the desert.

CLARK: When I got here and started seeing the lack of water the hills were bare, and there was no grass. And I thought I wonder if there's something you can do about this. And I started doing it. And I realized you can, and I guess I got hooked.

BASCOMB: Also, the Tony award winning musical “Hadestown” a retelling of ancient Greek myth and a parable about climate change.

CHAVKIN: The metaphors of industry and there being this terrible imbalance between how an industry consumes the natural world and what the natural world is able to sustain and give on its own, are all through the piece.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

Democratic National Convention

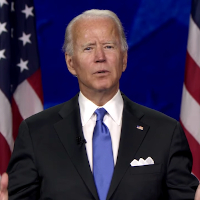

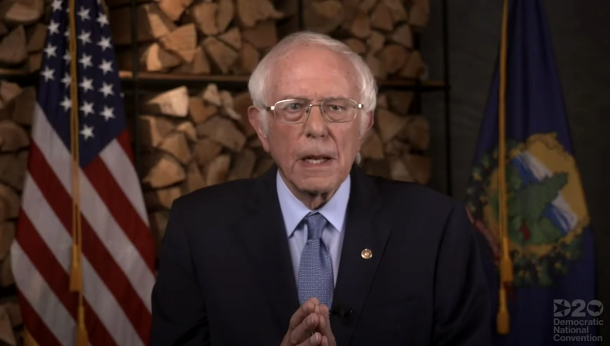

In his nomination acceptance speech on August 20, 2020, Democratic Presidential Nominee Joe Biden named climate change as one of the four major crises facing America at this time. (Photo: screenshot of 2020 Democratic National Convention)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb, in for Steve Curwood.

The Republican and Democratic national conventions every four years are typically a spectacle of political speeches, balloon drops, and delegates decked out in red white and blue from head to toe.

But this year, amid the coronavirus pandemic, the conventions have moved from the stage to our screens with virtual side events and socially distanced political speeches that and aired in a 2 hour prime time address each night.

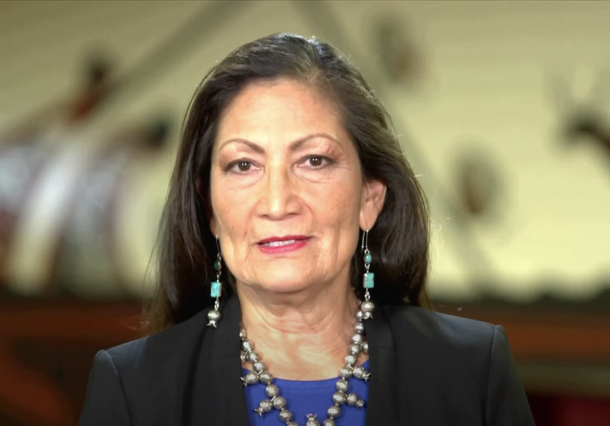

In one such speech, Vermont Senator and former Democratic primary candidate Bernie Sanders shared words of praise for Joe Biden’s clean energy plan and urged his progressive supporters to vote for the more moderate Democratic nominee.

SANDERS: Joe will rebuild our crumbling infrastructure and fight the threat of climate change by transitioning us to 100% clean electricity over the next 15 years. These initiatives will create millions of good paying jobs all across our country.

The control room of the virtual 2020 Democratic National Convention, the backbone of the coast-to-coast production of the week's proceedings. (Photo: Alex Hanel/DNCC)

BASCOMB: Washington State Governor Jay Inslee was also in the early running for the Democratic nomination.

The focus of his campaign was climate change and his plan to address it was arguably the most ambitious of any of the candidates.

In an untelevised virtual side event Governor Inslee shared his support for Mr. Biden’s climate action plan.

INSLEE: The scale of their plan of $2 trillion, is both enormous and adequate. And the fact that they're thinking in these terms with the scale of this is just thrilling to me, and I'll tell you why these are going to be good union paying jobs. Right? These are not just physicists and rocket scientists. These are electricians and carpenters and steel workers and sheet metal workers, and iron workers.

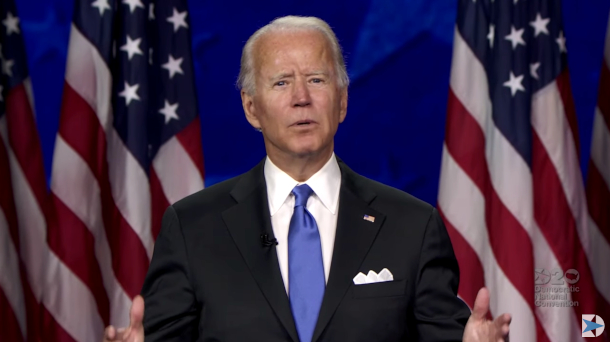

BASCOMB: At a virtual meeting of the Native American caucus, New Mexico Representative Deb Haaland spoke her support for Mr. Biden and disdain for President Trump’s gutting protections for land sacred to native peoples.

Democratic Rep. Deb Haaland of New Mexico, a member of the Laguna Pueblo people, condemned President Trump’s move to shrink Bears Ears National Monument and said that she believes a President Biden would give Native Americans a seat at the table in decisions that affect lands sacred to them. (Photo: screenshot of 2020 Democratic National Convention)

HAALAND: This administration, you know, cutting out big swaths of Bears Ears and grand staircase Escalante, this administration, blasting tribal, sacred burial ground so they can build the wall on the southern border. these are these are things where tribal leaders must have a say in where we are moving forward. And that's those are two very good reasons why I am going to do everything I can to get Joe Biden elected because I know he absolutely would never, never appoint a coal lobbyist or a gas in our lobbyists to any of these positions.

BASCOMB: On the last day of the convention Joe Biden officially accepted his party’s nomination and spoke about the coronavirus, racial injustice and tackling climate change.

BIDEN: One most powerful voices we hear in the country today is from our young people. They're speaking to the inequity and injustice that has grown up in America. economic injustice, racial injustice, environmental injustice. I hear their voices if you listen, you can hear them too. And whether there's existential, existential threat posed by climate change, the daily fear of being gunned down in school, or the inability to get started, your first job, will be the work of the next president to restore the promise of America to everyone.

BASCOMB: In advance of this year’s Democratic National Convention the moderate and progressive wings of the party worked together to create several unity task forces aimed at finding common ground for the party platform.

One of those task forces was focused on the environment and climate change.

For more on the convention and the official Democratic party platform I’m joined now by Peter Dykstra.

Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News that’s ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. Hey Peter!

So, what were your take homes from the convention?

Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, who had also sought the Democratic nomination for President, shared words of praise for Joe Biden’s clean energy plan and urged his progressive supporters to help elect the former Vice President. (Photo: screenshot of 2020 Democratic National Convention)

DYKSTRA: Well, in order to do a diligent job here at living on Earth. I watched four nights worth of convention coverage. One of the things I didn't hear a whole lot on is climate change. Vice President Biden identified it as one of the four crises that a new president or Donald Trump would face. The other three, of course, are race relations coronavirus, and the economic plunge caused by coronavirus. They all get talked about a lot in primetime climate change really didn't.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I watched a lot of it as well and it seemed every time climate change was mentioned, it was always sort of in a laundry list of other problems and never really seemed to get the attention that an existential threat of this magnitude would deserve, one would think.

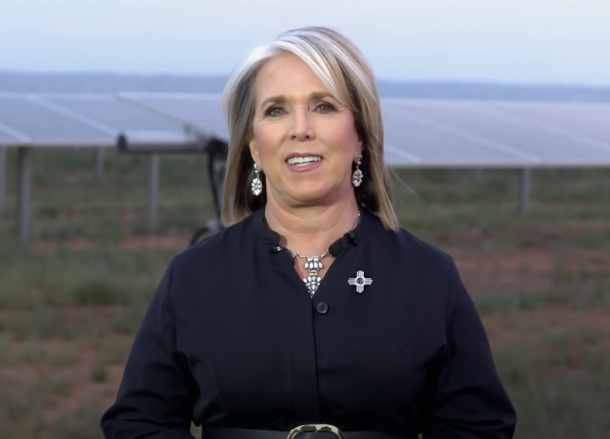

DYKSTRA: There were a couple near exceptions in some of the more minor speeches. California Governor Gavin Newsom did a live shot from a wildfire in his state which of course is head disastrous problems with wildfire. He linked them to climate change, New Mexico governor Michelle Lujan Grisham talked for several minutes about clean energy in five minutes segment that featured a lot of activists, like a 15 year old named Alexandria Villaseñor from New York City, who's kind of being positioned as the American answer to the young climate activist Greta Thunberg.

Joe Biden and his wife Jill Biden wave to Kamala Harris and her husband Doug Emhoff following Joe Biden’s Democratic Presidential Nomination acceptance speech. (Photo: screenshot of 2020 Democratic National Convention)

BASCOMB: Yeah, but noticeable from its absence was, um, Al Gore. Where was he in all this?

DYKSTRA: Well, here you go. You had three former presidents, ex vice presidents, John Kerry, who was Secretary of State pushed through the United States involvement in the Paris Climate accord. You had all sorts of prominent members of Congress, entertainment figures, and the one who was missing in all of this is the guy who has been pushing on climate change for 40 years Al Gore. He won a portion of the Nobel Peace Prize. He won an Oscar for his climate slideshow an Inconvenient Truth but somehow the biggest opportunity to vindicate him to give him credit for an I told you so and to lay out a path toward action on climate change in my opinion the Democrats blew it. They should have had Al Gore front and center to talk about climate change on a par with those other issues that are deemed existential crises.

BASCOMB: So very little was said about climate change in primetime. But there are all of these virtual side events and caucuses and of course, the party platform. What did you see there?

DYKSTRA: Well, there's side events. So what it means is much of America didn't see them. They didn't get a message that they're really important. Almost every speaker, as you suggested, made a passing mention of climate change things that get passing mentions in primetime the suggestion is they're not going to be an immediate focus for the Democrats should they win the White House or control of the Senate, any of the things that may be up for grabs in the selection, it left me with a feeling that climate change will kind of be pushed to the back, particularly if the economy is still hurting in future years, as the experts tell us it will be.

New Mexico Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham addressed viewers of the 2020 Democratic National Convention from a solar energy facility in the state. (Photo: screenshot of 2020 Democratic National Convention)

BASCOMB: So I read the party platform, and they have a very ambitious goal of being carbon neutral by 2050. And they lay out, you know, creating green jobs and doing that, you know, solar installation and the like, which all is exactly what the Green New Deal was advocating for, a way to lift people out of poverty and also really address the climate emergency. But they never actually said the phrase Green New Deal in all of the environmental information in the party platform. Why is that do you think?

DYKSTRA: Well, I think because they're terrified of the Republicans using the phrase Green New Deal and holding up its most visible advocate Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez as negatives as a threat to the American way of life. The Democrats embrace a lot of the Green New Deal I don't think they're ever going to say it per se, even with a President Biden, or the Democrats in the majority in the Senate if that happens because the Republicans are relentless, and not always principled in the way they attack. And the Green New Deal, could be a new version of the Red Scare as we get down to the last 11 weeks of the campaign.

Democratic Presidential Nominee Joe Biden and Jill Biden walk through a hallway of state flags after his nomination acceptance speech. (Photo: screenshot of 2020 Democratic National Convention)

BASCOMB: Well, another thing on the party platform, they state their continued support to ban oil and gas drilling on public lands, but there was no mention of removing tax breaks and subsidies for fossil fuel companies. That was on the party platform in 2016. And really not controversial. It's something that Mr. Biden and Senator Harris both campaigned on. yet. It's not there on the 2020 platform. But Stef Feldman, who's a policy director for the campaign recently said that Joe Biden is still committed to ending fossil fuel subsidies. So what gives Peter?

DYKSTRA: Well, I'd say one thing, and that's, that's why journalism is so important to look at the fine print that's gone away in a party platform, even though party platform is not nearly as important as what the Democrats commit themselves to in primetime when so much more of America is watching, paying attention, and presumably holding both parties accountable to what they say, and how their lips move when they're speaking in front of the entire nation.

BASCOMB: All right, Peter. Well, thanks for following this for us. And we'll talk to you again next week when the Republicans take the stage or the virtual stage as it is.

DYKSTRA: Well, I'm looking forward to watching more hours and hours and hours of TV on the Republican convention. But I'm sure we'll both have plenty to talk about next week. I'll see you then.

BASCOMB: Okay, sounds good. Thanks a lot, Peter, Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. You can find more on the Democratic National Convention in the environment on the living on earth website, loe.org.

Related links:

- Watch the 2020 Democratic National Convention

- The DNC Council on Environment and Climate Crisis held a 2-hour virtual event as part of the 2020 Democratic National Convention

- InsideClimate News | “After Two Nights of Speeches, Activists Ask: Hey, What About Climate Change?”

- HEATED newsletter | “The Democrats’ climate betrayal”

BASCOMB: Coming up – A look at the diverse, and often frightening, world beneath our feet. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Issi Rosen, “Mediterranean Samba” on Homeland Blues, by Issi Rosen, Brownstone Records]

"Hadestown" Brings Climate Change To Broadway

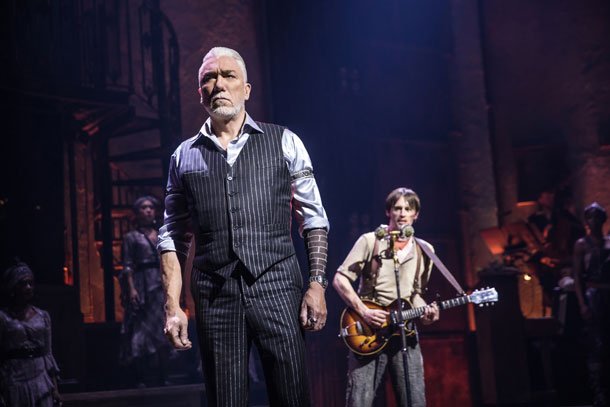

Hadestown garnered 14 Tony Nominations and won eight Tony Awards including Best Musical. Pictured, Amber Gray plays Persephone. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

According to ancient Greek myth, Hades, ruler of the underworld, kidnaps the Goddess Persephone and brings about the first winter on earth. For writer Anaïs Mitchell, that sudden change in the climate is the perfect backdrop for the story of her Tony Award-winning Broadway musical “Hadestown”. The show infuses the theme of climate change with New Orleans jazz, folk, and pop music. Here to tell us more is the director of “Hadestown,” Rachel Chavkin. Rachel, welcome to Living on Earth.

CHAVKIN: Thanks very much.

BASCOMB: So for someone that hasn't seen the show or listened to the music yet, can you give me a quick summary of what it's about?

The musical tells the Greek Mythological tale of Orpheus and Eurydice in a Great Depression-era-inspired, post-apocalyptic setting. Reeve Carney and Eva Noblezada play the characters on stage. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

CHAVKIN: Yeah. So “Hadestown” is a retelling of an ancient story, for those who know their Greek mythology, which is the Orpheus and Eurydice story, as it intersects with the myth of Hades and Persephone. Eurydice says -- I think these lyrics are no longer exactly in it, but -- "flood will get you if the fire don’t”. So there's a sense that the above world is a dangerous place. But you hear about this mythic place, which is Hadestown, and Hadestown is a land of plenty and a land where you sort of aren't ever worried about where your next meal is going to come from. And so during Act One Eurydice chooses to go down to Hadestown, and the audience along with Eurydice discover that Hadestown is actually basically this proto-fascist state. And you hear about a wall that is getting built, and the wall will never be done. And Orpheus comes down to Hadestown to try to get the love of his life back.

BASCOMB: So here at Living on Earth, we tend to look at everything through the lens of the environment. But it seems pretty clear to me that there's some clear allusions to climate change. Can you tell me about that?

CHAVKIN: Yeah. So the image of the climate being out of whack has been a core one for Anaïs since she started writing the show. And so as we thought more and more about shaping the world that Eurydice and Orpheus are living in, a world caused by, in Greek mythological terms, the decay of this ancient marriage between Hades and Persephone, a world that is out of balance, where it is either freezing or it’s blazing hot, and that food becomes a really, you know, a scarcer substance and the idea of stability becomes harder to imagine, and that Eurydice is, is a character who has spent her life running. All of those are things that kind of crystallized while we were making the show.

BASCOMB: Well, let's play a song from the show. I want to play a clip of “Any Way the Wind Blows”. But before we do, can you set it up for me? What's happening at this point in the storyline?

CHAVKIN: Yeah, so “Any Way the Wind Blows” is really right at the top of the story. It's really where you hear her, this kind of tough chick who is this survivor, walk into this bar, that is Hermes' bar where she will eventually, right after this song, meet Orpheus, the love of her life. And she talks about how screwed up the weather is.

Hadestown is an underground factory that serves as refuge from the weather above. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

[MUSIC: Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording), “Any Way the Wind Blows”, By Anaïs Mitchell]

Weather ain't the way it was before.

Ain't no spring or fall at all anymore.

It's either blazing hot, or freezing cold. Any way the wind blows.

And there ain't a thing that

you can do when the weather takes a turn on

you, 'Cept for hurry up and

hit the road. Any way the wind blows…

BASCOMB: So that song seems a little post-apocalyptic, but in keeping with what scientists tell us to expect with climate change, you know, shifting seasons, droughts and floods. Was that the idea here?

CHAVKIN: Definitely Anaïs was profoundly impacted by the news that was happening. I mean, every day while we were making this, while we were making this work. During the last fire season when California seemed to be you know, totally, totally a flame. And, and then meanwhile, on the East, you had these tremendous floods that now we're seeing in the Midwest. Yeah, all of that, all of that news impacted the lyrics and imagery of the, of the show.

André De Shields plays Hermes, the show’s narrator. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

[MUSIC: Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording), “Any Way the Wind Blows”, By Anaïs Mitchell]

When your body aches, to lay it down.

When you're hungry and there ain't enough to go round.

Ain't no length to which a girl won’t go

any way the wind blows.

BASCOMB: You could probably make the argument that Eurydice is considered an environmental refugee. I mean, she leaves her cold home in seeking something that's safe and warm in Hadestown. To what degree do you think that that's true?

CHAVKIN: I would say that is very fair to how we discussed it. You know, I think that there is the idea that Eurydice, has many, many things, many demons chasing her; the weather is one of them. The weather is of course, also a metaphor for economic injustice. She makes the choice to go to Hadestown, you know, she's choosing between the love of her life and the ability to have food, and know that she has a place to sleep and a bed to lie down in, and a job to go to, so that the environment is part of what she's running from is exactly right.

BASCOMB: Now, Hadestown is actually an underground factory, and maybe indirectly, the source of the problems above ground, you know, the changes in weather and so; that also seems pretty clear commentary on the toll that industry is taking on our environment.

Patrick Page plays Hades, an industrial CEO of the Hadestown factory. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

CHAVKIN: Definitely, the metaphors of industry and there being this terrible imbalance between how an industry consumes the natural world, and what the natural world is able to sustain and give on its own, are all through the piece. Ultimately, we think about the marriage of Hades and Persephone, and this marriage between industry and nature, as being one that it's not to say, industry is bad, it's to say that industry is totally out of balance. And as we understand it, that Hades was always a builder, but that at a certain point, when he began to be afraid that Persephone wouldn't come back to him. And he began to be jealous of her time away -- you know, the mythological six months that she had above ground -- that he began to over produce and consume. And there's this image of his jealousy, sort of almost spreading like an oil slick across the land. And Hadestown is the product of that. So it's almost like industry on steroids.

BASCOMB: Well, at the end of the day, what do you hope that people will take away from watching “Hadestown”, from experiencing the music and the show?

CHAVKIN: Hadestown is about many things. But for me the final image and the image that I hope that people leave with happens during “Road to Hell II”. It's the final song in the show proper that Hermes sings. And there's this image of, yes, it's a sad song. It's an old song. But we sing this song, we sing the story of Orpheus and Eurydice anyway, because there is hope in the simple act of retelling the tale. There is hope in the community that gets gathered to hear the tale and that essentially with each generation, the needle moves a little bit, whether we see change in our lifetime or not.

Eva Noblezada as Eurydice. (Photo: Matthew Murphy)

BASCOMB: Rachel Chavkin is the Tony Award-winning director of “Hadestown”. Rachel, thank you so much for taking this time with me.

CHAVKIN: It's a pleasure.

[MUSIC: Hadestown (Original Broadway Cast Recording), “Road to Hell (Reprise)” By Anaïs Mitchell]

See, Orpheus was a poor boy.

(Anybody got a match?)

But he had a gift to give.

(Give me that.)

He could make you see how the world could be

In spite of the way that it is.

Can you see it?

Can you hear it?

Can you feel it?...

Related links:

- Learn more about the show

- See Hadestown’s collaboration with the Natural Resources Defense Council

Underland: A Deep Time Journey

“Darkness is an illumination down there, as well.” – Robert Macfarlane (Photo: Joshua Sortino on Unsplash)

BASCOMB: Many nature writers look skyward, towards majestic mountains, open valleys, and wild rivers. But there’s a whole other world beneath our feet, in the dark and hidden places below the Earth’s surface. This is the place that the British author Robert Macfarlane calls the "Underland.” For nearly a decade, he has been venturing into ice caves, exploring underwater rivers, and crawling through catacombs to discover this hidden world that can be both beautiful and macabre. His latest book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey, documents these travels and explores the human relationship with the "deep time" of down below. Living on Earth's Jenni Doering spoke with Robert Macfarlane.

DOERING: So, let's start off with a big question. What is the underland?

MACFARLANE: Yes, that is a very good question. And I guess there's a 500-page answer to that. But the short version of that would be all that, all that lies beneath us, and particularly, that which lies below the surface of the land. And it's a place that we have shunned and been frightened by, but also been drawn to for as long as we have been anatomically modern humans and indeed longer than that. So, I wrote a book about mountains a very long time ago, which tried to work out why people go high; this, this is an attempt to answer the question of why people go low, and what they find when they do.

DOERING: You say that we tend to shun the underland. Why is that?

MACFARLANE: It's dark, it's dirty, it's hard to get anywhere. It's associated with death, with mortality, with confinement, exploitative labor practices, incarceration. It has a pretty bad rap, but it is also teeming with wonder and secrets. And those are its two sides. Darkness is an illumination down there as well.

DOERING: It's amazing what's just underneath the surface.

Underland: A Deep Time Journey explores the little-known world beneath our feet. (Photo: courtesy of W. W. Norton)

MACFARLANE: Yeah, that's it. I, I say really early on in the book, look up and you can see literally trillions of miles on a clear night. You look down, and your sight stops at the ground. And yeah, and that's why we know so little, because we are so kind of optically charged in our knowledge.

DOERING: I mean, it seems to hold this incredible power for you as you’re journeying through, as you're going through the catacombs in France and this underground river running through Italy.

MACFARLANE: Yeah.

DOERING: I mean, reading your book, it almost felt like you were traveling to Hades and back.

MACFARLANE: [LAUGHS] Well, someone just introduced me to this great musical of yours, Hadestown, which just cleaned up at the Tonys. So, I have some of the songs from Hadestown going through my mind, but I think there is a great playlist to be made from the underworld songs, the jams going underground... Anyway, so it goes. But yeah, it's it's a zone of myth. Hades is one of those; classical myth is filled with what they call the katabasis, that journey down into the underworld often to retrieve something of value, a loved one; or to consult with somebody, the dead about the future. And I guess that that it did come to have that, that pull for me. But I was always guided, okay. The book is filled with these mycologists and glaciologists and all people who have intense relationships with what lies beneath imaginative, or, or otherwise. And they cast the light, they held the light for me.

DOERING: The subtitle of your book is " A Deep Time Journey". Can you explain what deep time means to you?

MACFARLANE: Yeah, deep time is, is a phrase actually, that John McPhee, that great nonfiction writer comes up with, New Yorker writer. But it's an old concept, as old as geology. But basically, it is Earth history in its full units of age and ancientness -- the epoch, the Eon, the era -- not the minute, the second, the week, the year. Deep time crushes our units to a wafer, really, to an irrelevance, it seems. But so deep time means Earth historical time. But I think what's striking to me about the Anthropocene, arguably, is that we have accelerated, we have shallowed, deep time; or we've scrambled deep time and suddenly all these things -- we burn Carboniferous-era fossil fuels to melt Pleistocene-era ice to determine Anthropocene future climates. And suddenly, deep time is no longer sequential and orderly, if it ever was, and it's, it's muddled. And that's an unsettlement for us.

Entrance to an underground river in Slovenia, part of the “starless river” system Macfarlane describes in his book. (Photo: Martijn Booister, Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0)

DOERING: How did you choose the places that you wanted to visit for this book?

MACFARLANE: They chose themselves. I -- this may be a post-op rationalization, but it did feel afterwards as though I was uncovering a kind of buried structure that already existed. I knew I wanted to write about deep time, I knew I couldn't only do that in my own body and my own voice, because I am a shallow time human being. [LAUGHS] And so there are parts of the book that are told, not by me, but just they move around within the deep time history of the underworld and around the geography of the globe, as well as in Gaza, or they're in the Cretaceous, or they're in America where nuclear waste storage facilities are being constructed in Yucca Mountain and so forth. But the main parts of the book occur in Britain, then in central and Eastern Europe, and then in the north, and the Arctic. And that that's just the way it fell out.

DOERING: There's a lot of nature in this book, of course, but there's also man-made structures, like I'm thinking of the catacombs under Paris, France. And so, you traveled down there. What was it like to be down there in the catacombs of Paris, France?

MACFARLANE: The first thing to say is I was down there for two and a half days, which is the longest I've ever gone -- which isn't very long, but is longer, I suspect than most people have gone without seeing the sky or the sun or the surface or anything. And I went down with an amazing person called Lina, who was generous and bold and brave and rather different underground than she was above ground. She was gentle in both places, but she was quite quiet above ground, but had to be quite decisive. And she had this amazing navigational ability down there. She really didn’t consult a map. She’s been down there lots and lots, and she could just map it in her brain. It was like she had GPS for the catacombs. [LAUGHS] So, we yeah, we spent time down there sleeping in the dark, and you do lose track of time. And you also realize you're in limestone, which is, which is a rock made of, of death, basically of accumulated bodies of marine microorganisms, and also filled with the dead of Paris.

Deep time: the Grand Canyon reveals rock layers laid down over hundreds of millions of years. (Photo: morais on Unsplash)

DOERING: The Underland seems like such a place that evokes extremes of emotion -- wonder, as well as fear. How did these emotions manifest for you, in your explorations of the Underland?

MACFARLANE: That's a great question. And I was a conduit in a way; I mean, we have mined from it meaning as well as resource. So, I'm just one of, you know, a billion billion meaning makers. But there was one point in Norway where I, I just wept. When I, when I got into this deep sea cave, where cave art had been made about two and a half thousand years previously by really marginal, what we would call Bronze Age, and together is Peri-Arctic, peripatetic people. And then they painted these figures, the red dancers, out of iron oxide on the cave wall, deep inside this Granite Mountain, in a brutally wild place. So, and when I finally got there, after a really hard winter journey on my own, I was overcome.

DOERING: You worked for nearly a decade on writing this book. How did your relationship with the underland evolve over time?

MACFARLANE: Well, yeah, you're right that the idea first came in about 2010. And that was the year of the Deepwater Horizon blow-out, of the Icelandic volcano eruption, of the Chilean miners trapped underground. It was a real underworld year. I really started working in 2012. I think I -- a couple of things. One is I began to understand deep time as running forwards as well as backwards. And the second was just the age of the time we have spent being drawn into darkness. I wrote this book about mountains and, and why we're drawn to mountain tops. But that is so young, that is just punk-ishly young, that cultural impulse [LAUGHS], not even 300 years old. But we have been going into the darkness as a species, leaving those prints on the cave wall, those handprints on the cave wall that we've all seen the images of, for tens and tens and tens of thousands of years. So, something is at work there. And that is inexhaustibly fascinating to me.

Neolithic burial mounds at Knowth, Ireland. In Underland Robert Macfarlane explores the ancient human practice of burying our dead. (Photo: 1sock, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: As you've alluded to, humans have used the underland for -- I guess, as long as we've been around, almost? What are the different ways that we've found it useful to us?

MACFARLANE: Well, I say early on, but it took me a long time to work this out, that I think I call the three great tasks of the Underland. And they are to shelter, to yield and to dispose. So, to shelter is -- you know, where we put the bodies of our loved ones in a way to keep them safe, so we can go back and meet them again. It's where the Germans are putting all of their state documents and microfiche, or at the Svalbard Seed Vault, we're putting all of the, as much of seed biodiversity as we can in storage. So, that's this sheltering. And then yield -- obviously, we're a mining species, we're a burrowing species, we've drilled 50 million kilometers of oil borehole alone. We've mined so much wealth out of the earth. So, we go, we go to take knowledge, we go to take matter. And then dispose is where we put the stuff we don't want. Our nuclear waste, our sewage. The Cloaca Maxima in Rome was the -- yeah, the great, basically the great sewer at the heart of Rome, that Rome would just chuck all its stuff into. So, the underworld is our sump, is our shelter and is a treasure chest.

DOERING: In your book, you're thinking about the past, you're also thinking about the future. And you asked this really interesting, unique question: are we being good ancestors? What do you think the answer is to that?

MACFARLANE: No, no, no, we're not. And I think we're being asked to think more and harder about ancestry now in but in the sense, not of backwards in time, but forwards in time. And for me, that is, that is the deep time of this book, is actually not just the stuff which falls away behind us for billions of years, but what we're leaving.

Robert Macfarlane and two companions spent days wandering the labyrinthine catacombs underneath Paris, France, where ossuaries such as this one hold the remains of more than six million people. (Photo: Dave Shea, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

DOERING: Do you think there's anything we can do to do a better job of leaving a good future for those who come after us?

MACFARLANE: Yeah, I do. There are countless things we can do. I mean, if we think just in terms of Anthropocene future fossils, like what, in a very literal way, what will be our future fossils? It doesn't look great. We're going to leave lots of sheep, cow and pig bones behind. We're going to leave an absence of surface soil; we're going to leave an absence of biodiversity. We're going to leave a massive spike of nitrogen. We're going to leave radionuclides from our testings, we're going to leave fly ash and lead. It's a pretty good ugly record, particularly those extinctions and the habitat loss; that might be our script. So, I would love us to exit the Anthropocene and turn up in a -cene called something like the symbioscene, or the mutualcene, or the sustainability-cene, but it's -- we've got to, we've got to actually, for so many reasons.

DOERING: Robert, is there a passage that you'd like to read for us from your book?

MACFARLANE: Well, thinking about what we've been talking about, about the Anthropocene about things surfacing about time running fast, as well as slow, I'll read you a bit about a section from an extraordinary event, a calving event at a glacier, way up the remote east coast of Greenland in 2016. And I mention the year because that was a year of intense melt. Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, was at 22 degrees C, which is not what Greenland's capital should be feeling in that the ice cap was melting, the glaciers were running and calving fast, and we saw this extraordinary event.

In forests such as Epping Forest outside London, trees are linked via roots and fungi in an intricate underground network known as the “wood wide web.” (Photo: M W Pinsent, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

"'There!' shouts Bill, but we're all already looking there, where the first block fell, for it seems that a white freight train is driving fast out of the calving face of the glacier, thundering laterally through space before toppling down towards the water. And then the white train is suddenly somehow pulling white wagons behind it from within the glacier, like an impossible magician's trick. And then the white wagons are followed by a cathedral, a blue cathedral of ice complete with towers, and buttresses all of them joined together into a single unnatural sideways collapsing edifice. And then a whole city of white and blue follows the cathedral. As we shout and step backwards in voluntarily at the force of the event, even though it's occurring a mile away from us. And we call out to each other in the silence before the roar reaches us, even though we are only a few yards from each other. And then all of the hundreds of thousands of tons of that ice city, collapse into the water off the fjord, creating an impact way 40 or 50 feet high.”

DOERING: And you go on to write about how you are filled with this sense of dread.

MACFARLANE: Yeah, it was a dreadful event. Something else happened later, which is that a huge calving event happened from underneath the water. So obviously glaciers have a mass below the waterline and what I was describing there was a huge calving event that was coming from the above water face, pulling and pulling this ice out of itself. But also, what was happening under the water is a massive calving was happening under the water. Because ice is more buoyant in water it comes up and up came this huge, dark blue black pyramid of ancient ice. And for me, this was something out of an early 20th century horror novella. But what it was, was time itself rising up out of sequence, and of course glaciers do this, this is what they do. They're rivers of ice. But, but we are accelerating them as we are accelerating time in all sorts of ways. And, and for me that emblematic moment was an Anthropocene moment.

BASCOMB: Underland author, Robert Macfarlane, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Towards the end of his Underland journey, Robert Macfarlane descended into a moulin, a chasm carved into glacial ice by meltwater. (Photo: Destination Arctic Circle, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Related links:

- Underland: A Deep Time Journey

- The Atlantic | “What Lies Beneath”

- About Robert Macfarlane

[MUSIC: Izzi Rozen, “Shir Hanoded” on Homeland Blues, traditional, arr. Izzi Rozen, Brownstone Recordings]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A rancher in Mexico uses simple technology to bring water back to the desert. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Dick Hyman Group Featuring Howard Alden, I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles Music from the Motion Picture Sweet & Lowdon 1999 Sony]

Water Ranching in Mexico

Valer Clark next to a riparian forest, which serves as a bridge between the water and the land (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Today the lands of the Southwestern US and Northern Mexico are considered desert or semi-arid. But for a couple months each year the region is awash with water from the seasonal monsoons. The normally dry river beds fill with flood water and swell to create habitat for all manner of water birds and amphibians. The watery paradise is short lived though, and most of those streams dry up in a matter of weeks. But that wasn’t always the case. A network of streams, rivers and wetlands once crisscrossed the landscape. In fact, more than 150 years ago, around the time of the Civil War, people in the region struggled with malaria, a mosquito-born illness typically associated with tropical wet climates. Last year, I went to Mexico and I found a ranch owner that’s working on ways to keep some of that water on the land longer.

[FOOTSTEPS AND VOICES IN ECHOEY HALL]

Dry grass vs. healthy green grass. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

My journey starts at the Gadsden Hotel in Douglas, Arizona. It’s a grand building with walls the color of gold and marble pillars holding up an ornately painted ceiling. A step in the gray marble staircase bears a chip legend says was left by the Mexican Revolutionary Pancho Villa when he rode his horse up these stairs. Today it’s a popular spot for weddings and it’s here that I met Valer Clark.

CLARK: Good morning, so, this is a piece of history.

BASCOMB: The opulence of the hotel hints at an earlier time of prosperity and wealth. Valer says the whole region, north and south of the border, was made rich more than 100 years ago by the same things.

CLARK: This was copper, cotton, and cattle. The three Cs, you know, all in the early 1900s.

BASCOMB: Those three Cs made a lot of money but heavily degraded the land. Before the arrival of settlers the region didn’t have much water but there were some dense grasslands. Forests grew alongside rivers that meandered across the open landscape. And wetlands popped up every 20 or 30 miles along those rivers. But when Valer first visited back in the 70s, decades of mining and agriculture left the arid soil dry and cracked, few trees remained and the river beds were deeply eroded.

Valer came from a wealthy family in New York City. She and her husband at the time were travelling in Mexico and fell in love with the austere land. The wildness of the open parched landscape drew them in.

CLARK: We just came across this ranch, by accident. And he said, Well, why don't we bid on it, and I bid so low, I didn't think we'd ever get it. So I was thinking in terms of this being a summer place or something like that.

A beaver dam. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: That whim of a purchase of a summer place eventually ballooned into her life’s work.

CLARK: When I got here and started seeing the lack of water and seeing the situation, what it looked like, and the hills were bare, and there was no grass. And I thought I wonder if you could make a change. I wonder if there's something you can do about this. And I started doing it. And I realized you can, and I guess I got hooked.

BASCOMB: Valer eventually bought and rehabilitated some 150,000 acres of land in northern Mexico and the Southwest US. That’s more than 10 times the size of Manhattan. And her work here has been transformative, says Ron Pulliam.

PULLIUM: There are four great geological forces: there's volcanism, plate tectonics, there's erosion. And there's Valer. And Valer is one of the forces that has created the landscape around us here.

Wetland greenery. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Ron is an ecologist, formerly with the US Department of Interior, and founder of the nonprofit Borderlands Restoration Network.

[CAR DOOR SOUNDS, DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: I pile into a pickup truck with Ron. Valer, in her own truck, leads the way out of Douglas, Arizona and across the border to Agua Prieta, Mexico.

[DRIVING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We leave behind the maquiladora factories in the duty-free trade zone of Agua Prieta and drive an hour southeast to Valer’s ranch. Pavement and two-story buildings give way to dusty soil and brittle pale green grass. To me, as a New Englander, the landscape looks rather inhospitable, but Ron says this is prime cattle grazing territory.

PULLIAM: Generally speaking now, the stocking ratios are on the order of one cow to one hundred or two hundred acres in this area. And then think of around the turn of the century, 100 times that number of cows.

BASCOMB: And all those cows led to disaster for this delicate landscape.

PULLIAM: And so if you put hundreds of cows out on a small area here you basically reduce all the ground cover. So, when the rain comes it just runs off the land rather than being caught up in the vegetation.

BASCOMB: And keeping that rainwater on the land is the fundamental key to what Valer is doing to rehabilitate her property. More water will mean more grass and trees, habitat for the wildlife that was once common here. It’s sort of a build it and they will come philosophy.

Abundant reeds in the wetlands. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

[FOOTSTEPS ON GRAVEL]

BASCOMB: We arrive at Valer’s Cajon Bonito Ranch and she takes me on a walk around her property. She wears a cowboy hat over thick gray hair, jeans, and a white button-down shirt. She is tiny, so petite one might think her fragile, but she is shockingly strong and sets a fast pace over the rugged terrain.

In a similar way, Valer’s solution to rehabilitating the degraded land is equally small but powerful.

CLARK: This is what we call a gabion, which is a wire basket that is filled with rocks.

BASCOMB: That’s it, a wire basket full of rocks. They’re about 3 feet tall, some just 5 or 6 feet wide, others more than a hundred feet across. Valer and her crew have built more than 20,000 of them on her property. They all sit in riverbeds which are dry most of the year until the monsoon rains come. That’s when the gabions get to work. They slow down the water rushing through the river bed so silt can accumulate behind them, like a sponge.

CLARK: And that sponge holds the water. And so the water, instead of just whipping through fast, when it rains, 30% of it’s held back and goes into the ground. And so it filters down very slowly. And this is somewhere near the bottom. So you see pools of water.

[WATER SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Those pools of water are home to insects, birds, rare frogs, and endangered fish species.

CLARK: And trees, all these trees coming up, they’re a result of having water here.

BASCOMB: So how old are these trees? I mean, these are 30, 40 feet high. So how old are they?

CLARK: Not old at all, these grow very fast, these grow very fast, these trees. Some of them grow 10 feet a year.

During monsoon season, rivers in the area fill briefly and bring green before quickly drying back out. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Nearly all these trees have sprouted up since Valer began keeping more water on the land. Near the stream, a canopy of cottonwood trees towers over us and a lush green understory creates the feeling of a jungle that follows the narrow band of water. We continue our walk on the edge of the forest, which she says is a vital corridor for wildlife in the region.

CLARK: We’ve seen ocelot, we've seen bobcats and lions and bears and coatimundis and javelinas, ring tailed cats. . . .

BASCOMB: Have you seen a jaguar?

CLARK: We didn’t but a jaguar was photographed right coming….

BASCOMB: [screams] my goodness! What is that?

CLARK: That is a gila monster!

BASCOMB: You’re kidding.

CLARK: They’re very rare, I mean they’re very very… yes.

BASCOMB: I almost stepped on it.

CLARK: Take a picture, take a picture! Quickly. That’s a find. You found, that was very exciting.

BASCOMB: After being startled by the venomous lizard Valer and I head back to her ranch house. We meet up with Ron Pullium to see some more of Valer’s work.

[DRIVING SOUND]

BASCOMB: We drive past parched bare earth cracked into the shape of a hexagon and stop at a different ecosystem all together.

[WETLANDS SOUNDS, RUNNING WATER, BIRDS]

BASCOMB: Instead of a riparian forest this is a wetland teeming with life. Reeds and cat tails poke up through the water. At least a dozen different species of brightly colored birds dart about, butterflies sun themselves, and bright blue dragon flies copulate in mid-air. Ron Pullium says this region is a hotbed for insect diversity, including some 450 different species of bees and….

Gabions are baskets of rocks that Valer Clark places in stream beds to slow the water as it rushes through. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

PULLIUM: Very strangely, the desert area through here has exceptionally high dragon fly diversity. And that's one of the signs of the past extent of wetlands in this area.

BASCOMB: Indeed, historical records from the Spanish settlers suggest this region was once a patchwork of wetlands just like this. Gary Paul Nabhan is a desert ecologist with the University of Arizona. He says the word Sonora, as in, the desert here, actually means spring-fed wetland in a native language.

NABHAN: In an area the size of Connecticut, you might have 20, maybe 30 of these, but they were so important to human life and to wildlife that every one of them was named. And probably one in 10 is left, probably more like one in 20 or one in 30.

BASCOMB: How important are these types of habitat for the whole region, for the ecosystems?

NABHAN: Well, incredibly so, -- and look at the Vermilion flycatcher, I'm sorry, they’re showstoppers. They are just so beautiful.

BASCOMB: Oh, they're bright red, and they're beautiful. Yeah, yeah.

NABHAN: First of all, in a historical ecological sense. These were the seed beds for all the, the vegetation. But secondly, they were the hubs of human habitation because this is where all the ecosystem services happen. And so they were as important as the oases were in the Sahara Desert, you would travel 30 miles out of your way to reach a place like this.

BASCOMB: And important for migrating wildlife too. These were wet stepping stones between central Mexico and Canada.

[WETLAND SOUND]

BASCOMB: Bright and early the next morning I meet up with Ron Pullium to go birding near another wildlife corridor, which it turns out was a highway of a different sort not so long ago.

BASCOMB: Morning!

PULLIUM: We’re up for a late morning walk.

BASCOMB: Late morning? It’s 5:30.

PULLIUM: [LAUGHS]

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: We walk alongside a small creek, craning our necks up, hoping to spot some birds.

PULLIUM: This creek is interesting just in itself it was protected by Valer because it was identified as the most intact fish stream in northern Mexico, and perhaps the most intact in all of Mexico. And it had several species, five or six species, of rare and endangered species. And this also used to be the bus route. And it looks like a pristine natural stream now. But in the 1950s there was a biologist that camped on the shore right over here. And he, in the night, he counted five buses driving up the stream. This was the road between Sonora and Chihuahua.

Valer Clark perches on a gabion. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Somehow those endangered fish species managed to survive living in a bus route and are now on the rebound. Even beavers have re-colonized the river. At one-point Valer Clark introduced a few beaver pairs to one stream on this river. But now several more have been drawn to the water that is once again running free and the broad tailed volunteers are getting to the business of building dams for her.

For all her ecological work, Valer is still mindful of serving as a model for other ranches in the region that depend on raising cattle for their livelihood. She removed most of the cows from her ranch when she bought the place. But she did keep a small herd and is very deliberate about where and when they graze. And it’s paid off. Her ranch manager recruited members of his family to enter three novio steers in a large cattle exposition.

Bobby narrowly avoided stepping on this gila monster while out with Valer (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CLARK: All the people in Sonora bring their animals to this big thing, this big do. And so his daughter, Sarah, won first prize among novios. And she won the grand champion, the overall prize. And then when the animal was slaughtered, we won overall, the prize of having the best cut up meat too. So we couldn't, we couldn't get any better than that.

BASCOMB: The hope is that public win will encourage other ranchers in the area to explore the sustainable ranching that results in award-winning beef. And Valer’s biggest hope is that they will see the advantage of rehabilitating their own degraded land.

CLARK: I think the next thing is having people come and see the benefits of what we've done, that it is possible to turn land around, I think it's important, the next step would really be to reach out to other people, and let them know that it's possible to heal really sick land.

BASCOMB: In fact, Valer’s work is already spreading across the region, literally. The water she retains with her gabions does not stay on her land alone. It seeps into the water table and flows downstream, hydrating degraded lands for miles around. And in a region where water is wealth, Valer is already sharing in the profits of restoration.

Related link:

The Cuenca Los Ojos foundation, which supports preservation and biodiversity in Mexico and the United States

[MUSIC: Simon Wynberg, “Mariah’s Watermill” on Guitar Works, Narada Lotus]

[Rhinoceros Auklets]

BASCOMB: We leave you this week – in the company of some extraordinary creatures and their babies.

[Rhinoceros Auklets]

BASCOMB: These are several rhinoceros auklets with their chicks – recorded at Protection Island National Wildlife Refuge in the Strait of Juan de Fuca off the Pacific Coast. Rhinoceros Auklets are relatives of puffins; medium sized dark grey duck-like birds that spend their days at sea, and then return at night with fish for their single chick hiding deep in a burrow.

[Rhinoceros Auklets]

BASCOMB: Jeff Rice recorded these birds with support from Acoustic Atlas at Montana State University.

[Rhinoceros Auklets]

[MUSIC: The RH Factor, “Listen Here” on Strength, Verve]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

we tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer, I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth