September 4, 2020

Air Date: September 4, 2020

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

More Organics, Less Cancer

View the page for this story

A major study published in JAMA’s Internal Medicine Journal finds that among high consumers of organic food, breast cancer rates were reduced 35 percent in older women and lymphomas were reduced more than 70 percent. The observed decrease in cancer risk is associated with organic food’s lack of pesticides, dyes, and other additives, though more research is necessary to confirm these results and understand possible mechanisms. Ken Cook, President of the Environmental Working Group, joins Host Steve Curwood to consider consumer and research choices in light of this news. (07:56)

FaceTime: Bumblebees

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

One of the joys of gardening is getting to know the beneficial visitors in your yard, including the hardworking bumblebee. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender, describes a singular encounter. (03:31)

Toxic Black Hair Products

View the page for this story

Black women in America commonly use hair relaxers and leave-in conditioners to straighten and smooth their textured hair. But many of these products contain hormone-disrupting chemicals, which are associated with such health problems as early menarche, preterm birth, diabetes, and cancer. Dr. Tamarra James-Todd, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, spoke with Host Steve Curwood. (14:53)

Getting Hormones Out of Wastewater

/ Ari DanielView the page for this story

At a wastewater treatment plant, sophisticated filtration and sanitization methods aim to remove pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and chemicals. Human waste also contains various hormones, which can stick around in the environment and harm other creatures. But there are ways to get them out of the water. Ari Daniel reports from a wastewater treatment plant in Salem, Oregon on how this works. (06:11)

HBO's "Ice On Fire" Offers Climate Solutions

View the page for this story

The Earth is warming and changing faster than many climate scientists had predicted, and at times the future looks impossibly grim. Yet practical and accessible solutions to climate change are already at hand. The HBO documentary “Ice on Fire”, produced and narrated by Leonardo DiCaprio, focuses on these solutions and on the scientists who are tackling climate change. Director Leila Conners joined Host Steve Curwood to discuss the making of the documentary and who it aims to reach. (14:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

HOST: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Leila Conners, Ken Cook, Tamarra James-Todd

REPORTERS: Ari Daniel, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

A study shows evidence of a relationship between eating more organic foods and lower cancer rates.

COOK: What this study tells us is that, when it comes to the risks for cancer, an organic diet makes sense. A cleaner set of ingredients, closer to nature, fewer additives, less processing, is probably in general playing a role here.

CURWOOD: Also, African American girls are exposed to a high rate of dangerous chemicals through their hair care products.

JAMES-TODD: Young girls who were using hair oils had a significantly higher risk of starting their periods earlier than girls who had never used hair oils. And each year earlier that a girl starts her period, it’s an increased risk for developing breast cancer.

CURWOOD: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

More Organics, Less Cancer

A massive study in France followed the diets of nearly 69,000 people and found that those who ate the most organic food over the seven years of the study were 25% less likely to develop cancer as compared to those who ate more conventional food. (Photo: Rusty Clark, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is an encore edition of Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

A major study published in a Journal of the American Medical Association has found what many people have long suspected, eating organic food appears to reduce the risk of cancer. Among some 69,000 people tracked by French scientists over several years those whose diets contained more organics had about 25 percent fewer cancers overall, with 35 percent fewer breast cancers in older women and more than 70 percent reduction in lymphomas. This study suggests but does not prove that pesticides and other chemical residues in food cause cancer. But there is no reason to wait for more research when it comes to making food choices, advocates say, including the President of the Environmental Working Group, Ken Cook. Ken, welcome back to Living on Earth.

COOK: Thanks, Steve. It's great to be here.

CURWOOD: So, when this study came out, it showed strong evidence in support of the long held belief that organic food is better for us. How do you feel now that this study is out there?

Diets with high amounts of organic produce may have more than a lack of pesticides to thank for their health benefits – organic food tends to leave out dyes, preservatives and additives found in other conventional foods. (Photo: Philosophographlux, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

COOK: Well, I guess I feel as if we should have been doing studies like this a long time ago. We really do need to be much more careful about the low levels of carcinogens that we still have in our diet. The fact that several cancers here did show a marked decrease to me tells me that organic food is probably targeting the mechanisms that are associated with those cancers. And the other thing that's interesting, while they've spent about pesticides there are other chemicals in non organic food that are not allowed in organic - certain chemical dyes, certain colorings, certain flavorings - that simply are not allowed in organic food manufacture. That, in addition to pesticides may be another reason why there's lower cancer rates amongst these mostly women who are eating more organic food.

CURWOOD: And of course, if a product is made from genetically modified organisms, it's not allowed to be labeled as organic.

COOK: That is true as well, and they're really not very many chemicals that are allowed in organic manufacture packaged food compared to conventional where there are thousands. So, there are lots of questions raised by this study, but to me it goes back to the basic point. A cleaner set of ingredients, closer to nature, fewer additives, less processing, is probably in general playing a role here.

CURWOOD: So, how excited are you by this study and how much of a game changer do you think it might become?

COOK: Well, I find it very encouraging. It's just one study that's often said from time to time, and they're right. One study is just one study. To me, this opens the door to doing more types of analyses like this of big populations and refine even further what we know about the diet of the people that are responding to the questions. What we need to do now, Steve, is we need to scale it up. We're still talking about organic with a very small footprint on the agricultural landscape, and unfortunately still a very small footprint as it were in our diet. But the other thing, I just have to say is, this does not mean that eating conventional fruits and vegetables is a bad thing. We think that's positive. The real problem when we have in our diet is the processed food, the additives, but this study adds that extra twist.

Avocados are one of the foods that made Environmental Working Group’s “Clean Fifteen,” a list of foods that, when tested, show a naturally low level of pesticides. (Photo: Rachel, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: Some people are going to be surprised that you say go ahead eat conventional fruits and vegetables that have pesticides on them because they're less of a risk than other things that we put in our bodies.

COOK: Yeah, that's right but,, if I can give my little boy a conventional apple I'm going to give him that as opposed to a pile of cookies or some chips. And so, I think we want to move the diet lower down in the food chain to plants - a plant-based diet is desirable - but we don't have to choose. We want people to think holistically about their health and their diet, and in order to do that we have to recognize a not everyone can find or afford organic food.

CURWOOD: So, every year you guys publish a list of foods which are kind of [MAKES NOISE] more worried about the pesticides and then the things that you like. Mention some of those items to us now.

COOK: Well, sure. I mean every year we look at the data that comes out of the Department of Agriculture. They test our fruits and vegetables for pesticides, and we look at a couple of things. We look at how many pesticides and what concentration they are in fruits and vegetables. So, we've come up with two lists. One is the dirty dozen. These are the fruits and vegetables that have the most pesticides on them, and if you want to avoid pesticides, you should try and buy organic of those types of foods. Then there's the clean 15, which we started doing some years ago because we were concerned that organic wasn't always available and we also want to incentivize people to get them thinking positively about eating fruits and vegetables. These are things like like bananas, certain types of squash, where the pesticide levels are extraordinarily low, they almost seem as if they're organic.

CURWOOD: The study published in "The Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine" talks about cancer being associated with consumption of non organic food, or the other way around is that the more organic you eat the less likely you are to get cancer. From your research and studies over the years, which of these findings really resonate with what you've been told by other scientists, in particular the types of cancer?

Ken Cook is the President and Cofounder of Environmental Working Group. (Photo: Courtesy of Environmental Working Group)

COOK: These are exactly the kinds of cancers that we would be concerned about with these exposures, and while this study focused on cancer, it also made me wonder the benefits we might see or the understandings we might reach if they did a similarly large study of this sort and looked at other disease outcomes, neurological diseases, ADHD, early onset Alzheimers, any kind of damage to our nervous system. We have a lot of pesticides that are in use and are in the food supply that have that particular health end point associated with them, while with others it is cancer. So, again I think the overarching message here is that when you look at a large population like this and you ask a lot of smart thoughtful questions about eating habits, we emerge with a fresh understanding of the benefits of having a diet that is clean.

CURWOOD: Why haven't we see this kind of study out of the United States, do you think?

COOK: I think we may see interest in doing a study such as this in the United States now, but what I will say is we know that the other side of this debate in the chemical industry has not been eager to have these kinds of studies conducted and simply wants to reassure everyone that whatever is in your food now is safe because the government says so. And that's the backdrop here. We have science that tells us that there are sometimes very subtle, sometimes long-term effects on our health from exposure to pesticides and other toxic chemicals, and because the exposure only manifests itself decades later, it's very difficult to get a handle on those, and because the government often doesn't regulate them, it leaves people thinking well perhaps there's not much to it after all. Studies like this breakthrough and you suddenly realize, ah-ha, all along our hypothesis was probably right. You put chemicals in food that even at trace levels are considered carcinogenic or could mess with our nervous system our hormone system. Over time, it could have an effect but you need a very powerful study to draw out those conclusions. This is one such study and I think there may be more that follow now.

CURWOOD: Ken Cook is the President of the Environmental Working Group. Ken, thanks so much.

COOK: Steve, thank you.

Related links:

- The original article in JAMA’s Journal, Internal Medicine

- Environmental Working Group: Massive Study Finds Eating Organic Slashes Cancer Risk

- The Environmental Working Group’s shopper guide for the ‘Dirty Dozen’ and ‘Clean Fifteen.’

- About Ken Cook, Environmental Working Group President

- CNN | “You Can Cut Your Cancer Risk by Eating Organic, a New Study Says”

- New York Times | “Can Eating Organic Food Lower Your Cancer Risk?”

[MUSIC: Soweto String Quartet, “Writing On the Wall” on Renaissance, by Geissman/Coll, RCA]

FaceTime: Bumblebees

A bumblebee on a milkweed plant. (Photo: (c) Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: One of the joys of gardening is getting to know the beneficial visitors in your yard, including the hardworking bumblebee. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender has more.

Bumble Bees, Long Island Sound

© 2020 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

The hurricane did not amount to much. Not by the standards of New England where we have history, of great storms, that take lives, and sink ships, and tear away the land. This one brought more water than wind. Even so. Here close to the sea it was enough. Surrounded by debris, a single hydrangea, sole survivor among what once were many is in flower and covered with bumblebees. One to every stamen in the dense white array of blooms.

How important to them, this one living plant, the difference between extirpation and continuity. They go about their business at a low contented hum. Like a punctuation mark in her warning colors of black and yellow a guard bee leaves the others, straight up, straight towards me. She stops eight inches from my face. Right between my eyes. Below and behind her the others continue in their work. Not her. She flies out and around me returning to the same place. And again. And again. And does not touch me but only hovers, perfectly balanced, unwavering and too close, her impossibly small bumblebee wings beating to a transparency. I know what she wants.

She behaves as if she knows that I know, or at least that I should. But I wait. To see. What will she do? How long will it take before her patience wanes and she stings me. Five hundred million years of evolution separate us. Her ancient compound eyes are not the eyes by which I see. Her brain is not like mine, nor her form except for the fact of a fundamental symmetry we share, that the left side is the same as the right. And yet perceives what and where

my eyes are and that this is how to get my attention. That I live behind my eyes. Me. I am there. This is where my consciousness abides. That I am a Sentient Being. How can she know? It can only be a projection. One she would not make if she were not conscious of her own Consciousness and its same location. Perhaps this is why rather than harming me, she waits. Until, I take my two steps back - She pauses for a fraction of a beat - Then dives into the flowers where she disappears.

CURWOOD: That’s Mark Seth Lender, Living on Earth’s explorer in residence.

Related link:

Mark Seth Lender's website

[MUSIC: Michala Petri, “Variations brillantes for descant recorder and harpsichord, variation IV” on The Virtuoso Recorder, by Ernst Krahmer, RCA/BMG]

CURWOOD: A look at how we remove hormones and chemicals from water before it goes into the environment or back to homes. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: The Vignola Collective, “Slayer In the Grass” on Gypsy Grass, by Hanneman/King, Dare Records]

Toxic Black Hair Products

Dr. James-Todd says that as society moves away from white standards of beauty, more Black people have come to embrace their natural hair. (Photo: Nina Strehl, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[CLIP FROM HAIR THE MUSICAL https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w_zaSKZks1A]

“Darlin', give me a head with hair, long beautiful hair

Shining, gleaming, steaming, flaxen, waxen”

CURWOOD: Hair: you can style it just about any way you like – if you use enough heat or hair product. And if your hair reflects your African roots but you’d rather keep it straight and smooth, chances are you use a whole bunch of products including leave-in conditioners, root stimulators, and relaxers. But some of these products may be harmful to your health. The Silent Spring Institute measured concentrations of estrogen-mimickers and other chemicals that disrupt the hormone system in hair products marketed to Black women. They tested 18 popular products and detected between 4 and 30 of these chemicals in each one. For more, I’m joined by epidemiologist Tamarra James-Todd from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Tamarra, welcome to Living on Earth!

JAMES-TODD: Thank you so much for having me.

CURWOOD: So, talk to me about how diverse Black women’s hair is. You know, as Black people, we come in all kinds of shades; I imagine, the hair comes all kinds of different ways.

JAMES-TODD: Right. So, there are different textures and different grades of hair from relatively straight hair to very curly, sometimes called “kinky” hair, and they have different requirements. It's really dependent on the shape of the hair shaft, but that can cause people to need to use different types of products.

CURWOOD: And people often don't like the hair they have. If it's straight, they want it curly. If it's curly, they want it straight, huh?

JAMES-TODD: I think that would be universal for most women. [LAUGHS] Definitely. But certainly in the Black community I think that there are some real issues around hair and part of that is kind of social and cultural issues regarding what is seen as beautiful, with straight long hair being kind of the stamp of beauty -- oftentimes in American culture particularly, in Western culture -- and so, people will do different things to try to adhere to that standard of beauty.

CURWOOD: So, what kinds of hair products do Black women typically use?

JAMES-TODD: So, oftentimes when I'm asked this question and when I first started this line of work, the first thing that would come up is, oh, hair relaxers. And so, thinking about things that people use, you know, whether it's every few months or a couple of times a year to straighten their hair. But what I think is often forgotten is things that we use daily such as hair oils, moisturizers, lotions, leave-in conditioners, gels -- kind of, you name it, that's what people are using to get the different styles that they want.

CURWOOD: Or heat... I mean, as an African-American growing up, I saw women with these really hot combs and I have to laugh out loud at Alex Haley's Autobiography of Malcolm X where he has this scene that Malcolm X tries to straighten his hair and his head is on fire so he sticks his head in a toilet to cool it down.

JAMES-TODD: Yes, that scene, I think, many, many women and some men can identify with... pressing, those pressing combs. So, it's not just chemicals, but it's also physical changes that people will try to do or undertake.

CURWOOD: So, what got you first interested in studying the potential health effects of chemicals in Black women's hair?

JAMES-TODD: So, when I was a master’s student at Boston University, there was an interesting study of magazine advertisements advertised to white women versus Black women. And there was a Ladies Home Journal article where it had an ad for white women being marketed to, kind of, anti-aging cream containing hormones. And the other magazine, which was kind of featured in this particular study, was from Essence magazine, a magazine commonly marketed and read by Black women, and it was advertising placenta. And it was something that I remember seeing when I'd walk into, you know, a Black hair supply or hair care store, and seeing placenta and just wondering, what exactly is that for? Why are people using that? And around that same time, an issue of Time magazine had come out, kind of querying why were girls starting their periods earlier and earlier. And somehow that just kind of clicked for me. Is it possible that what is in some of these hair products around hormones and so on… is that part of the reason why we're seeing earlier periods, particularly in Black girls, which at the time there was a very large study that had reported that 60 percent of Black girls had reached their periods by age 12 compared to only 30 percent or so of white girls. So, as a master’s student, that piqued my interest.

A 1917 Advertisement. Madam C. J. Walker, an entrepreneur and activist born in 1867, led the movement to create healthy hair care products designed specifically for Black women. (Photo: Courtesy of Madam Walker Family Archives/A'Lelia Bundles)

CURWOOD: And the answer is?

JAMES-TODD: So, we did, in fact, do a study; as a doctoral student at Columbia University, I did a study called the Greater New York Hair Products Study where we did, in fact, go and we queried what types of hair products people are using. And we found that young girls who were using hair oils for a longer period of time and more frequently had a significantly higher risk of starting their periods earlier than girls who had never used hair oils. And you know, each year earlier that a girl starts her period, it’s an increased risk for developing breast cancer.

CURWOOD: So, I'm thinking that this is linked somehow to chemicals -- fancy name is endocrine disrupters -- hormone disrupters, chemicals that kind of mimic estrogen and other hormones. To what extent is this phenomenon linked to such chemicals, do you think?

JAMES-TODD: So, at the time we started looking at this because of another study that had come out of the small case series of four young African-American girls. They ranged in age from four months old to four years old, and they had all developed breast and pubic hair. So, incredibly young children…

CURWOOD: ...at four months?

JAMES-TODD: At four months old!

CURWOOD: … at four months!

JAMES-TODD: ...and interestingly enough, the pediatric endocrinologist that had seen these young girls asked the moms all sorts of questions about what products they were using, what they had been exposed to in the home. And the common thread he was finding was that all of the moms were using -- these were girls so they were all using hair oils and different types of care products on children. Quite frankly, this is something that happens probably daily in the Black community. But when he sent those products out for independent laboratory testing, he found three different forms of estrogen. And so when we started looking at this, and thinking about, you know, are these endocrine disrupting chemicals? -- I wasn't even there yet -- I was just thinking, maybe we'll find estrogen in these products. He, in fact, did and when he told the moms to stop using these products, the breasts regressed and the pubic hair fell out. So, fascinating case series. And when we sent these products out roughly 10 years later, we did not find those three different forms of estrogen. But we did find parabens, phthalates, and other chemicals that are known to be endocrine disruptors. And so what we know now is that about 50 percent of products advertised to Black women contain these types of chemicals compared to maybe only seven percent that are advertised white women.

CURWOOD: You mentioned earlier periods. What are some of the health problems that have been linked to endocrine-disrupting chemicals?

JAMES-TODD: So, many of these products contain fragrance, which often is synonymous with phthalates. Phthalates are linked to obesity, increased risk of diabetes, as well as an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk, as well as pre-term birth and preeclampsia and gestational diabetes. There's some emerging work around fibroids that are showing some associations with some of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals and certainly there's some associations between some of the endocrine-disrupting chemicals and breast cancer and other cancers. There's a recent study, in fact, that came out looking at hair dyes and found associations with breast cancer incidence.

CURWOOD: So, how commonly do Black women suffer from these various health problems as opposed to the general population?

JAMES-TODD: So, when you're talking about things like diabetes, aside from Native Americans, Black women have the highest prevalence of diabetes in the U.S., for example. They are also more likely to be overweight or obese. They have some of the highest proportion of pre-term birth and a host of other things, fibroids and so on. And so when you're thinking about a lot of these metabolic or reproductive health outcomes, it's really important to consider why that might be occurring and not simply attribute it to, oh, there must be some inherent underlying genetic differences.

CURWOOD: Tamarra, what can consumers do to protect themselves from these potentially harmful chemicals and personal care products?

JAMES-TODD: You know, it's a two-part issue. Part of the problem is that our current laws which haven't changed since the 1930s particularly around personal care products, we don't require companies to disclose information regarding all of the substances they're putting in or chemicals they're putting into products due to trademark agreements.

For many in the Black community, hair care is a process that may involve different products like leave-in conditioners, root stimulators and anti-frizz polishers – but it’s also an important community activity. (Photo: Andrew Ruiz, Unsplash)

CURWOOD: Wait. So, what's in the stuff that's going on one's body is not on the label?

JAMES-TODD: Correct, and so, of concern, of course, is that then we're completely relying on the companies to test for the safety of our products. And it doesn't take a lot of thought, but that seems like a conflict of interest. The company is trying to make a profit. You know, right now, there is some legislation under way and being developed; the Personal Care Product and Safety Act is being developed by Senators Feinstein and Collins to really, kind of, rethink the protocol and the process by which chemicals and ingredients are tested before they make it to our shelves. Because the average consumer thinks that if it's on the shelf, it's safe.

CURWOOD: In the meantime, what's someone to do who says, OMG, this stuff could give me cancer or make me overweight, all kinds of not fun things. How can someone find safe hair care products?

JAMES-TODD: There is a growing amount of information out there around fragrance and considering going fragrance-free. So, that might be a strategy that one takes, maybe reducing the amount of synthetic chemicals that are being used. There's a kind of movement towards “do it yourself,” and then also, I think, you know, it's cultural change. So, we started with this idea of standard of beauty, and it’s, in my opinion, beautiful to see people starting to embrace more natural hair styles which require less chemical exposure. Certainly people are still using some of these other products daily, but the fewer chemicals that one might be using may be helpful.

CURWOOD: How affordable are paraben-free, phthalate-free alternatives to mainstream hair products for Black women?

JAMES-TODD: So, I think the bigger question around that is, are they even on the market? There's very limited selection of those products on the market, and where they do exist they are often not necessarily in kind of traditional stores, and are often more expensive. So, in that case, I think that there needs to be more products introduced on the market, with recognition that these products are important to African-American women and that they do have purchasing power. This is a very large industry.

CURWOOD: We've been talking about women here, but of course, men use these hair care products. What risks do Black men, do men of color, run when it comes to hair care products?

JAMES-TODD: It's funny you should ask that. One of the issues that came up when we were doing the Greater New York Hair Products Study that we did back in the early 2000s was that we were just collecting data on women. And one of our largest catchment areas when we were doing recruitment was at churches, and so we would go in and make our little pitch and I'll never forget, one gentleman and his son stood up and said, "What about us? We use hair products as well!" And I said, “Well, we're not really studying you right now." We were interested in breast cancer at the time which was part of the reason why we weren't studying men -- not that men can't have breast cancer! -- but it was one of those things where it was kind of an “ah-ha” moment and so the reality is that Black men are using these products too. Oftentimes they wear shorter hair styles and so if you think about it, the application of some of these products is that much more close to the scalp and absorbed through the scalp, and, you know, could have some similar health implications for diseases that are linked to some of these endocrine-disrupting chemicals.

CURWOOD: Talk to me about your own hairstyle, Dr. James-Todd, and what you use and what advice based on your own experience -- just anecdotally -- what advice you would make based on that experience.

Epidemiologist Tamara James-Todd spoke with Living on Earth about her research on the harmful effects of hair products on Black women’s health. (Photo: Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

JAMES-TODD: So, I remember when I was probably about eight or nine years old, and my mom took me to that, you know, beauty salon and I very much remember one of my first visits there. And again this is at a time period and an era where straight hair was what was acceptable, and so I had a perm done. And all my hair fell out. [LAUGHS] And I was done. I didn't want to do that anymore, and so I have been natural since the late 80s. And I remember that that was at a time where my grandmother, who was born in Tennessee, did not think that was acceptable at all. And I like my curly hair, and so it's been interesting to watch this transition happen before my eyes. I went to school in the south, too, I went to Vanderbilt University, and I remember many of the other Black women thinking, like, why would she wear her hair like that, or thinking I was from a different country, because if I was American, I would not wear my hair this way. And it's been beautiful to see people embracing their hair. I am fragrance-free. I've been using the same product now for the past 30-plus years. Thank goodness it's still on the market! [LAUGHS] But, you know, I have a daughter as well and I use that same product on her. I think that minimizing -- again, my philosophy is if I can minimize the amount of products and maintain natural hair that's healthy, then that's good enough for me. As far as advocating for other women, I understand that some people don't feel as comfortable, you know, doing that, or they think that it'll affect their job or other issues. But I think as society changes its standards of beauty, it's been nice to see that being embraced.

CURWOOD: Now people can go on our website to see your beautiful hair, but if they can't, it's lustrous, shiny, pulled back in a bun in the back. You must use a fair amount of oil.

JAMES-TODD: So, I do use this, it’s really a leave-in conditioner, and water. [LAUGHS] So, that's about it for me. But I do recognize that that's not what everyone else could do.

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] Dr. Tamarra James-Todd is an epidemiologist with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

JAMES-TODD: Thank you.

Related links:

- The Greater New York Hair Care Products Study

- About the Silent Spring Institute study

- More on Tamarra James-Todd

- More about Change-maker Madame C.J. Walker

[MUSIC: Poncho Sanchez, “Afro-Cuban Fantasy”]

Getting Hormones Out of Wastewater

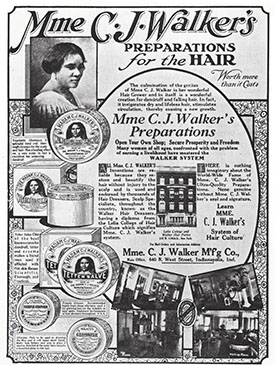

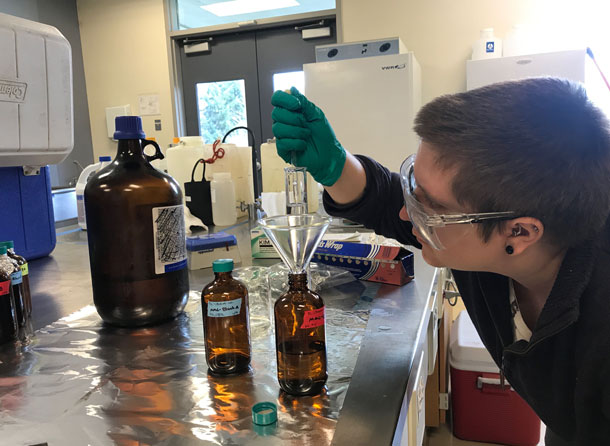

Postdoctoral Researcher Carolyn Hutchinson tests a water sample in the lab. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

CURWOOD: Our modern world simply wouldn’t be the same without wastewater treatment, which keeps much of the yuck we produce out of streams, rivers, lakes and oceans. And it’s a tall order, because people put a lot of stuff down into sewers, including pharmaceuticals, microplastics, and chemicals that standard treatments fail to filter out. And human waste contains various hormones, though there are ways keep them out of the environment. Ari Daniel visited a plant in Salem, Oregon to find out how.

DANIEL: It’s hot out. So you take a shower. Or you fire up the grill. And after eating a burger, you wash your plate off. And then, later, you flush the toilet. All that water — it just… goes away. Gurgles down a drain into the pipes. But that’s hardly the end of the story. That water gets cleaned up so it can tumble back into a river or stream. And it turns out that the process may inadvertently help clear the water of potent hormones.

The big stuff, that’s easy to filter out of the 45 million gallons of water flowing through the Willow Lake Wastewater Treatment plant in Salem, Oregon every day.

EISNER: There’s a lot of little McDonald’s toys that come through, little kids flush down the toilet.

DANIEL: Stephanie Eisner — operations manager here — says they also get a lot of lumber and tires showing up.

DANIEL: That’s getting flushed down the toilet?

EISNER: Well, most likely, somebody pulled a sewer manhole in the road and stuck tires in there.

A series of long, narrow rectangular pools where treated wastewater is disinfected and exposed to sunlight, which can degrade chlorinated estrogens. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: After the toys and tires get screened out, what remains is dirty water.

EISNER: Right now, we’re right by our south digester complex.

DANIEL: We are walking amongst sewage?

EISNER: So there’s pipes below us, yes, that would be having wastewater flowing through it. We try to remove as much of the pollutants that we can.

DANIEL: That removal takes place, in part, in clarifiers — that look like giant circular swimming pools. Solids settle out and can be removed, and greases float to the surface where they can be skimmed off. Separately, bacteria eat away a lot of the gunk in the water. And then, the final step, says Dave Griffith, an environmental chemist at nearby Willamette University —

GRIFFITH: This is the disinfection basin in front of us, and it’s a really important part of wastewater treatment. You kill anything that’s pathogenic.

DANIEL: The plant disinfects the water by chlorinating it. Griffith’s got his eye on this chlorination step… because chlorine is reactive, so dumping it into the water here means creating a raft of new chlorinated compounds.

[WATER SOUNDS]

We stand above a surging spray of water that’s about to leave the plant and enter the Willamette River.

GRIFFITH: Alright, shall we grab a sample?

HUTCHINSON: We should.

DANIEL: Griffith and one of his researchers, Carolyn Hutchinson, lower a pail into the froth below. They’re collecting water samples in search of estrogen.

HUTCHINSON: Estrogen is a very potent steroid hormone.

DANIEL: Everyone — you, me, your neighbor — excretes estrogens, so they find their way into our wastewater.

HUTCHINSON: One big effect is it feminizes fish populations.

DANIEL: That’s right — it feminizes fish. Which means turning all fish in a population — including the males — into females. And that can lead to a collapse of the fish stock.

HUTCHINSON: It also affects amphibians, birds, even mammals.

DANIEL: Estrogens react with chlorine, and Griffith wants to know what happens to the estrogens here after the chlorination step.

GRIFFITH: That basin over there where the chlorination happening is exposed to the sunlight.

From left, Carolyn Hutchinson and Dave Griffith at the Willow Lake Wastewater Treatment Plant in Salem, OR. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: I follow Griffith’s gaze to a long, narrow rectangular pool. It’s uncovered, which isn’t the rule. Due to odor and other reasons, not all treatment facilities expose the water to sunshine. But the UV radiation from sunlight introduces an unexpected — and free — benefit.

GRIFFITH: One intriguing thing that we found is that the chlorinated estrogens degrade much more quickly under sunlight than the regular estrogens. Before they even get to the end of the basin.

DANIEL: In other words, they’ve degraded before the water exits the plant and returns to the river.

EISNER: That’s good news.

DANIEL: Stephanie Eisner again.

EISNER: So it might make some people change the way they do things.

GRIFFITH: Our goal is that we can inform how we treat wastewater in a more cost effective, overall a better way.

[BOAT MOTOR RUNNING]

DANIEL: A couple miles away, a small boat speeds along the Willamette River. Dave Griffith is aboard.

GRIFFITH: So, there it is right over there.

Treated wastewater flows into the Willamette River and gets diluted. (Photo: Ari Daniel)

DANIEL: He points to a spot in the water near the tree-lined shore. It’s where the water from the treatment facility flows into the river and gets diluted.

GRIFFITH: So we’re gonna go just downstream of this point to get a sample of basically river water and wastewater mixed together.

DANIEL: This is where Griffith can measure how many estrogens there are in the real world. Which will tell him just how effective the degradation of these hormones has been.

GRIFFITH: If we understand better the mechanisms here and in the wastewater treatment plant, we can better predict what’s happening in any other river situation where you have a wastewater treatment plant discharging water.

DANIEL: Estrogens are just the beginning. Because Griffith’s curious about the interplay between chemicals and our liquid environment more broadly.

GRIFFITH: There’s not a chemical out there that you make, produce, use that doesn’t end up in the environment in some way or another, whether it’s accidental or intentional.

DANIEL: Griffith pauses, the boat hovers over its waypoint, and the water sampling begins in earnest.

[WATER SOUNDS]

Nearly all the water flowing past the boat today won’t end up in one of Griffith’s glass containers. It’ll snake northwards, connecting with the Columbia River, where it’ll surge west, ultimately flooding out into the Pacific. Until eventually, one day, it may once again find itself inside your home.

CURWOOD: That’s Ari Daniel reporting from Salem, Oregon.

Related links:

- The Willow Lake Wastewater Treatment Plant in Salem, OR

- About environmental chemist Dave Griffith

- About Reporter Ari Daniel

[MUSIC: Dan Sullivan, “Wave” on Cape Cod Magic by Antonio Carlos Jobim, self-published]

CURWOOD: Coming up – The film Ice on Fire and some proven ways to less the chance of runaway climate change. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Entrain, “Cohiba” on Rise Up, by S. Holmstock, Dolphin Safe Records]

HBO's "Ice On Fire" Offers Climate Solutions

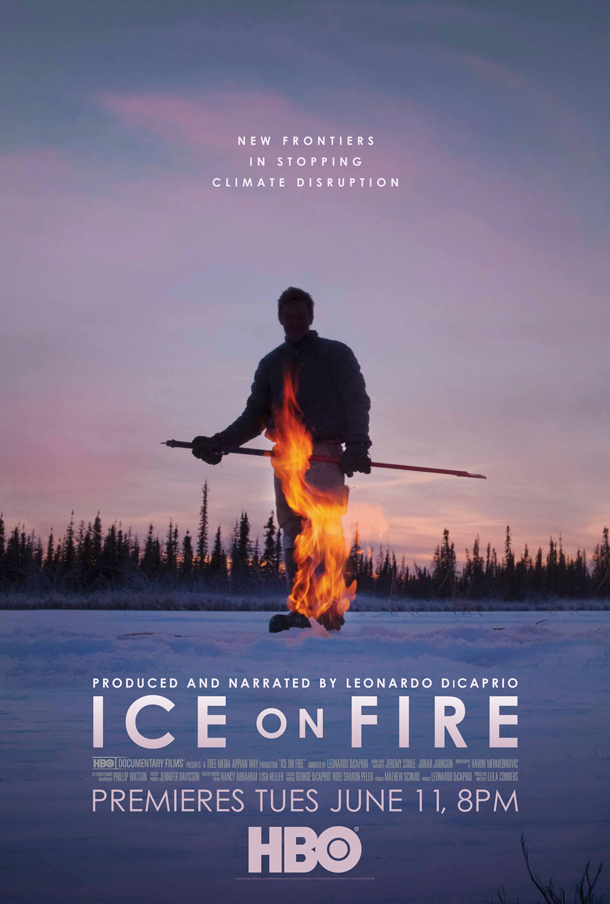

Ice on Fire is available for free through HBO. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[EXPLOSION SOUND]

CURWOOD: You might think you’re hearing a jet engine, but it’s actually methane leaking from the melting tundra in the Siberan Arctic that’s been set on fire. This ominous sign of global warming is also the title of a documentary about climate change, narrated by Hollywood movie star Leonardo DiCaprio. In contrast to many climate documentaries, Ice on Fire not only issues a dire warning, but it also seeks to inspire people to follow proven, safe, and sustainable pathways available right now that can reverse global warming. Leila Conners directed and edited Ice on Fire, and we’ll speak with her shortly, but first here’s a preview of her documentary, which you can watch for free, simply by going to the HBO website.

[FILM MUSIC]

DICAPRIO: Over the last 250 years we have in effect conducted the largest science experiment in history. The melting of the worlds snow and ice has now triggered multiple climate tipping points threatening the very existence of life on earth. Yet this disturbing future need not be set in stone. But the clock is ticking, scientists say we must implement these solutions immediately.

These natural disasters are so common now that people know it is going to happen to their community. It's not a matter of it but when. It is a wakeup call to everyone that climate change is here and that you need to plan for it.

Ice on Fire took two years to make and features scenes taken from around the globe. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

MANN: In short you're looking at a world with less food, less water, and more people. And that's a recipe for a national security disaster.

DICAPRIO: Science tells us that our current climate crisis is a problem we created. But it is also a problem we can fix. Climate change can be recovered if we act now.

BENYUS: Climate change gives us an opportunity to really behave differently on this planet. We see what we can do at our worst, and now the question is, if we were to consciously be a part of the healing it will unleash, I think, our creativity. If we were to see ourselves as helpers and healers who can help the helpers heal the planet, that is so much better than seeing ourselves as disruptive toddlers with matches. You begin to realize that all of us are somehow connected to little bits of the solutions.

HAWKIN: Where do we stand? Is it possible? Is it game over, or is it, in fact, game on? Which is, we have, at hand, the ability, capacity, and solutions, that can reverse global warming...but reverse…

DICAPRIO: We are the first generation to see climate disruption and we are the last to fix it. It is time to end the delay, to listen and implement the solutions at hand time is running out, the ice is melting, decisive action must be taken now. There is no other option. This moment is within our reach, let us grasp it. It is up to us, each one of us, to save this unique blue planet for generations to come.

[FILM MUSIC]

CURWOOD: We just heard excerpts from the documentary Ice on Fire narrated by Leonardo DiCaprio and directed and edited by Leila Conners. Leila joins us now from Santa Monica to talk more about the film, available for free now on HBO. Thanks for joining us, Leila!

CONNERS: Hello, and thanks for having me.

CURWOOD: Describe for us the opening scene, we're looking from a drone and we see?

CONNERS: A snowcat climbing the mountain. And, we're not sure where we're going quite yet, but we see a female driving the snowcat in a blizzard white out. And, the first thing we finally hear is she says, you know, we have to come up here every Tuesday to collect the sample. And, you're thinking, what is that and all of a sudden, she pulls up to the shack in the middle of this mountain. We're at 11,000 feet, there's wind blowing, it's very cold. And, basically, she goes inside, and she pulls gas out of the air and into these canisters. And what she's doing is taking the weekly measurement of the atmosphere. And we find that this is how we've known about the carbon in the atmosphere for the last 50 years. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has been conducting these sample tests for 50 years in the same locations every week. And they also do it in 60 places around the world. For example, in Mongolia, there's a woman that takes these canisters and takes a train ride for 10 hours, and goes up a mountain to take the sample and come back. So, these are dedicated people, everyday people with science backgrounds that helped take the samples, and they're all sent back to NOAA in Boulder, Colorado for measurement. So, the reason why we started the movie like this is that we really wanted to say, look, you know, this is, this is a person that you and I can recognize. A hardworking person. And these are not liars. These are people who are gathering the data gathering the evidence that so that when we say carbons in the atmosphere, this is not a debate. It's like taking your temperature, right? And, we go on to explain later that, you know, the question carbon that they're measuring, is specific to fossil fuel burning. So let's C 13 carbon, natural carbon is C 14. And so they know exactly that it's human caused, it's never been a question.

Fossil fuel burning is one of the leading causes of excess CO2 in our atmosphere. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: And, of course, when you mean by C 13, is a carbon that's been sequestered in the earth for millions of years is no longer radioactive. And, the stuff that's out with us right now does have a little bit of radioactivity.

CONNERS: Precisely.

CURWOOD: Now, you and Leonardo DiCaprio have collaborated in the past, you did the 11th Hour back what in 2007, you are a codirector on that, doc, what inspired you and your team to make this film?

CONNERS: Well, as you know, things have not improved. And, we were very, very concerned about... Leonardo specifically, was concerned about methane, and what was happening in the Arctic and the spike in methane readings in the atmosphere. So, he wanted us to investigate that, and let people know about it, because as you know, it's a tipping point that we don't want to cross. And, alongside that, as you know, there's also innovation coming online, as well as more knowledge about how nature works. So, we just felt that there were a lot of new things that were occurring that we did not see in the general press. So, therefore, we decided to make the film!

Ice on Fire earnestly attempts to persuade its audience that if they take action now then climate change can not only be halted, but reversed. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: Your film is huge. You cover a lot of territory, you cover a lot of things. You yourself personally, were there in the editing booth to make it all come together. At the end of the day. Who are you trying to get to with this movie? Who are you trying to reach?

CONNERS: We're trying to reach people that are ready to step into this transformation. And, we know that could be almost anybody. We also know that there are people that are able to step into creating community gardens, step into planting trees, step into innovating, those were our primary targets. But, we also wanted to reach everyone through the beauty of it. And, that's what we concentrated on. We also had this idea that we wanted to show people the world from a human level. So, a lot of climate docs, and I've done a few, have very distant vantage points, often. Satellites and very high, distant, and we flew the drone, purposely at the level of a human being, at the height of human being. So, it was really bringing people into the world into the spaces where we were. And we felt that if we did that, and if we talked to people that work every day on this, that it would have more connectivity. And we're actually finding that that's actually the case, it is connecting.

Urban farming is a great way to capture CO2 while creating healthy foods for a community. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: So, what I'm hearing you perhaps say is that for folks who have a level of concern, who have some familiarity to this, that this is a shorthand guidebook for them to look at the possibilities, as well as the problems.

CONNERS: That's exactly it. It's sort of the update, it's like, here's where we're at. And, also, here's how the world works. And, this is how you can plug into it. So, what we tried to do is say, look, the carbon cycle is really the problem here. Because what we've done is disrupt the carbon cycle with fossil fuels. And, so, once people understand that, in the film we explain how it works, we understand Oh, okay, well, we can remove carbon from the atmosphere. You know, nature is our first line of defense, and also innovate and find other ways to do it.

Renewable energy, such as wind power, has been in existence for a long time. Ice on Fire urges their audience to further implement these renewables to halt climate change. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: Tell me about the scene where you show these carbon sequestering machines. They're big, shiny things with pipes, and they're making what? Coal, they're making diamonds, what are they doing?

CONNERS: They're making basaly rock in Iceland. So, basically, these carbon sequestering machines are made in shipping containers, just take a shipping container, put these pieces inside. So, it sucks atmospheric carbon out of the air, and then you can use it for stuff. Now, obviously, we need to turn some of it into stone. And, that's what they're doing in Iceland. So that it never comes back up. Again, you can also use the carbon from the sky to turn it into fuel. So, interestingly, direct air capture basically disrupts the fossil fuel industry. So right now, the fossil fuel industry is going around the world digging up stuff, you know, fracking and drilling. And that's just old news, now. You just have this little tiny machine, you can pull it out of the sky. Obviously, that is not reversing the load in the atmosphere, but at least it's not adding to. So, you know, it's something else I've been talking about where you know, people are innovating, people are declaring the climate emergency. And I'm very excited about that movement, and Sunrise Movement and Extinction, Rebellion, all this stuff. I mean, you really feel people are rising to the occasion. And a lot of climate scientist is looking director capture and said this is something very passive, it's reversing something that we've done. So yeah, a lot of climate scientists, as you see in the film actually support it.

CURWOOD: It's very interested in your film, you are quite subtle about making the point that keeping the rise to one and a half degrees centigrade is just the beginning of the long term game for humanity. Because we have to draw carbon back down even further so that we can refreeze the Arctic, and have the ecosystems that people used to live in here on the planet.

CONNERS: Well, yes, and I think what we're coming to understand, and that's why we had Daniel Rothman from MIT in the film, he's been studying carbon cycles over millions of years. And, as he said in the movie, you know, when carbon dramatically spikes in the atmosphere, the web of life collapses. And, so we have the Permian mass extinction, the PTM. And all of those, there's five mass extinctions that they have studied that all have the same signature have a high spike in carbon. So, what we need to do, you know, it draw that carbon down, like we said. 1.5 is the limit, where we are now as little over one, and that is result of the 400 parts per million. And like Jim white says, we're headed to 600 parts per million. That is just an untenable situation. I mean, that melts all the ice in the world. And that's happened in the past, in terms of other ages. I mean, there has been times where there has been no ice on the planet, but humans didn't live at that time.

Ice is melting at record rates, causing sea level rise. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: [LAUGHS] No. So, tell me about one of your most inspiring moments for you, when you were out on location.

CONNERS: The most inspiring thing was consistent across a lot of what we did, which was the earnestness within which these people do their work. And I think that's what comes across. I think that the hope that everyone's searching for, if you want hope, just go talk to the people that are dealing with this problem, because they're actively taking this on every day. And it gives you a sense of purpose and purchase on this. And that, to me is very, very heartwarming and inspiring.

CURWOOD: So, what was one of the most disheartening things that you encountered?

CONNERS: The sound of the dripping of the glacier in Iceland was the most haunting, and I still hear it in my mind. And, basically, when you're standing next to a glacier that's melting, like that, it's the sound of millions of tiny drops. So, it's not this crash and bang and whoosh. And, I'm sure it is that way, in some places. But, on a day to day basis, if you're standing next to a melting glacier, just millions of tiny little drops that are adding up to a little river that adds up to a wider river. And, that's the sound of the end of that glacier. And, that to me is horrifying.

Leila Conners is the editor and director of the documentary film Ice on Fire. (Photo: Courtesy of HBO)

CURWOOD: What some call the tears of the Arctic.

CONNERS: Yeah.

CURWOOD: Leila, how hopeful are you? What are the odds of our civilization, utilizing the solutions that you talked about quickly enough to turn things around before we wind up with the hot house earth?

CONNERS: I think I'm hopeful because we actually have the solutions at hand. It's not a problem that we don't have the answer for. We have the answer. We just have to do it. And, so that's why the denial industry United States is so lethal, because it's slowing us down. We have to move on from fossil fuels and really, you know, mobilize to pull carbon out of the sky and stop putting carbon up into the sky. And I think we can because we have the solutions.

CURWOOD: Leila Connors is the director and editor of the documentary film, Ice on Fire. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today, Leila.

CONNERS: Thank you.

Related links:

- Watch "Ice on Fire" for free here

- Learn more about Leila Conners’ other work here

[MUSIC: Jeremy Soule, The Streets of Whiterun (Skyrim)]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Anne Flaherty, Don Lyman, Isaac Merson, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Kori Suzuki, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth.

we tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood, Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth