February 12, 2021

Air Date: February 12, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

India’s Farm Crisis and the Climate Emergency

View the page for this story

India is experiencing dramatic climate impacts, with both increased flooding and drought. Farmers throughout the country have been struggling to survive, and in September 2020 the Indian government passed legislation that thousands of farmers have gone on strike against, fearing they won’t get a fair price for their crops. Omair Ahmad, the South Asia editor for The Third Pole joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about Indian farmers’ protests and how the climate crisis is changing agriculture in India. (12:44)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's Beyond the Headlines segment, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra and Host Steve Curwood discuss the pervasiveness of microplastics in farmed seafood. Next, they cover an update to the "secret science" rule, the Trump-era rule which would have made it harder for the EPA to use studies that keep confidential health data of participants. Finally, they look back at a moment in the environmental justice movement, and Bill Clinton's formal recognition of environmental justice on February 11, 1994. (04:29)

Angry Birds and the People’s Climate Vote

View the page for this story

Phone gaming apps meet climate policy through the work of the People’s Climate Vote, a survey conducted by the United Nations Development Programme. The survey gathered the responses of more than a million people from 50 countries, asking people how urgent they think the climate crisis is, and what policies they would like to see to tackle it. Cassie Flynn, co-author of the People’s Climate Vote, joins Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering to talk about the unique approach to polling, its limitations and how the survey can help leaders craft climate policy. (10:18)

Bottlenose Whales in the Arctic

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth’s Explorer-in-Residence Mark Seth Lender describes a pod of bottlenose whales as they swim through Hudson Strait above the Arctic Circle, and his impulse to join them. (02:34)

Modernizing Mobility

View the page for this story

In the United States transportation infrastructure has fallen deep into disrepair with $2 trillion of deferred maintenance costs. President Joe Biden is seeking to modernize mobility infrastructure in a way that supports the broader overall goal of net zero carbon emissions by 2050. Henry Cisneros, the former mayor of San Antonio who served in the Clinton Administration as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about what a massive transportation transition means for America's economy, equity and health. (13:08)

BirdNote®: Here Come the Barred Owls

/ Mary McCannView the page for this story

Barred Owls are among the most vocal owls in North America and one of the easiest birds for humans to imitate. BirdNote®’s Mary McCann shares some of the Barred Owl’s signature calls and what could be enabling the bird to expand its range West. (01:54)

In Honor of Black History Month: Harriet Tubman and the Barred Owl

/ Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

As a conductor on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman led some 70 people out of bondage, through woods and wetlands she knew well. Host Steve Curwood describes how Ms. Tubman used local bird calls including that of the Barred Owl to signal an all-clear to freedom seekers without attracting the attentions of slave catchers. (01:40)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210212 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Omair Ahmad, Henry Cisneros, Cassie Flynn

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender, Mary McCann

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

AHMAD: Protests erupt in India as farmers voice their anger over new government farming laws. And for agriculture to survive in India you need to grow climate appropriate crops and you need support by the government to make sure those crops are bought and nothing in these laws actually helps in that transition.

CURWOOD: Also, using mobile gaming apps to poll more than a million people about the climate.

FLYNN: If somebody's playing a game, like Angry Birds, you know, you get those ads that pop up. We replaced that with a poll. And we essentially asked people really two big questions. One was, do you think climate change is a global emergency? And then the second was, how do you want to solve it?

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

India’s Farm Crisis and the Climate Emergency

According to Oxfam India more than 75% of rural women in India who work full time are farmers but less than 13% of them own the land they till. Women have been a powerhouse throughout the protests, holding fort and cooking all in hopes in securing their jobs and land for future generations. (Photo: Niel Palmer, CIAT, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. India is home to more than 1.3 billion people and more than half of them make their living from farming. Massive farmer led protests and strikes erupted in India recently when the government announced new laws that farmers say would add an additional burden to their industry already struggling in the face of widespread droughts and floods.

[PROTEST SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Millions of farmers and their allies have flooded into major cities over the last few months to block roadways in protest. The Indian government has used tear gas to try to break up the demonstrations and at least one person has died. We’ll get into the new controversial laws in a moment but the struggle for Indian farmers started way before these protests. Climate change has dramatically altered the monsoon season that farmers rely on for water, forcing many to abandon farming all together. For more I’m joined now by Omair Ahmad, the South Asia editor for The Third Pole.

Omair welcome to Living on Earth!

AHMAD: Thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: I understand that climate change is taking a toll on farming there, the monsoon rains have changed. They're shorter and more intense followed by months of drought. Can you tell us more about that and how it's affected agriculture in India.

AHMAD: So, floods and droughts are the clearest indicator of climate change, right? And it's as explained by scientist, the hotter the air is, the more water it will hold. As the air heats up, it's takes more water for terrain. And when it rains, it does a lot more in a shorter time span. So that basically means you've got longer periods of dry spells and shorter periods of intense rainfall, the soil gets washed away with the intense rainfall. So you've got flooding, because for 1000s of years, you've been doing agriculture based on these rainfall patterns. And about 80% of rainfall in India comes within the four to five months of the monsoon period. And that is intensely important for agriculture. Now, that pattern is now being disrupted more and more. So you're not getting the long cycles necessary to grow a crop to its full potential. And even when it grows, sometimes what happens is floods come. Soo the untimely rain is hitting crops when they're standing when you've just harvested them, so that ends up causing a lot of loss and damage to ready crops. In areas where you have irrigation, what people do is try to pump up water to compensate for water that doesn't come at the right time. And then you put in a lot more fertilizer, to make sure that the crop grows up in the shorter time period that you have to its full capacity. At the same time, you also dump in more pesticides, because with climate change, you've got a lot more new pests coming in. And you want to make sure that you're defending the crop that you grow. And this has been going on now for the last few decades, this crisis led to climate change.

More than 250 million people across India joined the farmers' protests. Thousands of farmers have set up camp outside India’s “breadbasket”, New Delhi to protest against 3 farm bills that would further imperil farmers' survival. (Photo: Harvinder Chandigarh, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: So how are farmers dealing with it? I mean, it sounds like a really difficult situation for them.

AHMAD: So there's two sets. So there's the farmers without access to irrigation, which is about half of them. And how they're dealing with this is with great difficulty is the answer. Because if the drought hits, and you don't have alternative means of irrigation, there's only a certain amount of water you can pull out of well by yourself and put onto a field. And what that has led to is huge amounts of migration out of these farmlands to people coming to urban areas. Now these are skilled farmers, that's what their skill set is. But in urban areas, all that they have to sell is unskilled labor. So they tend to be incredibly badly exploited in the labor market. And because when droughts happen, so many people are on the labor market, they can negotiate any decent contracts. So right now I am in Delhi, and there are workmen working on a building just across the block. And these are people who earn about 400 rupees a day, that would be about $5 to $6. And the women who working on on these construction sites are earning about 200 rupees a day, that’s $3. And so people would, with an irrigated fields are largely just forced to sell their labor at very low prices. And it's largely male labor that migrates because it's much harder for women to migrate they face much more dangerous.

BASCOMB: This really sounds like a crisis on a lot of levels, a humanitarian crisis of people that can no longer make a living and are moving to the cities and maybe being exploited and also a food security crisis. What do you make of that?

AHMAD: So yeah, food security is a huge issue for India. And this is something like almost a recurring issue in the sense that when India became independent, it didn't grow enough food to support its population and so food aid became a huge part of the Cold War involving India and the US and the Soviet Union. And because India didn't want to be involved in the Cold War, it wanted to be non aligned in the 60s, it boosted what it called its Green Revolution to try to get food secure. The Green Revolution, basically narrowed down the amount of crops that we would grow. But it did it using a lot more water than we used to, and a lot more fertilizer than we used to. So India now grows, actually enough crops to feed itself and more. And when we were able to feed ourselves, we set in the public distribution system. So for people earning less than 70 cents a day, you have a below poverty line card, and you can go to a public distribution shop and get green at lower than market rate. The problem is multifold. One is there's lots of corruption when it comes to people making a bit of a quick buck between how much they're supposed to sell and how they are. Secondly, the public distribution system is very expensive and so you're, you're accruing all of these crops. Thirdly, and most importantly, because the Green Revolution was focused on using lots of water and lots of fertilizer and growing only a certain set of crops, we have been growing in a lot of areas, crops that are not suitable to the climate, using too much water and therefore driving down groundwater and polluting the land with excess fertilizer.

About 70% of rural households in India depend on urban agriculture for sustenance and about 60% of farming depends on rain-fed irrigation. (Photo: Randeep Maddoke, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: And now I understand that Indian farmers are protesting some new laws recently passed by the government. And these are serious protests. 10s of 1000s of farmers at sites across the country are blocking roadways blocking traffic, can you tell me about these new laws? And why are farmers so angry?

AHMAD: So we've got our MSP regime, this is the minimum support price regime. So the government guarantees that it will buy crops at a minimum price, setting a floor to how low a price can be. What they're afraid of is that with all of these laws coming in, that the government as a larger buyer is going to disappear from the market, they will be left in no position to really negotiate with large corporate buyers, and will have to sell at prices that buyers negotiate them too. And worst of all, what they're afraid of is that there won't be a guaranteed sell of their produce. So this has happened, unfortunately, with contract farming in India is that is it already exists. And that large private agro buyers have at times reneged on the contract, right. Or have said, basically, that what you're giving us is not up to our quality, and therefore we won't buy. And so you have a problem with the small farmer who's spent months growing this crop, and he suddenly doesn't have a buyer, right. And often it's women growing the crop, women are at least 50% of the workforce, often an underpaid workforce. But the person selling the owner of the fields will tend to be a man so at the end of the day, it's he selling. But a small farmer spends months growing these crops at the end of the day wants a certain guarantee of a buyer at a decent price. And farmers are now afraid that that's what the government is undermining in a bid to privatized large parts of farming.

BASCOMB: So why would the government want to make these changes? It sounds like they're prioritizing larger, more industrial farmers over the small scale farmers. Why does the government want to make these changes to begin with?

AHMAD: Well, large agro corporations can invest in large infrastructure. They can invest in silos, they can invest in storage facilities, they can invest in cold storage, they can invest in processing plants and all of these may in the end raise the amount of money that you can get from the crop. The challenge is, there is nothing in these laws that tells us that the farmer at the bottom will benefit that you will, may get more money out of these crops, but it's entirely at the mercy of the large corporations whether they will pay farmers more or less than they would earn earlier. And history kind of tells us that trickle down economics doesn't really work that well.

BASCOMB: You know, scientists tell us to expect all of these calamities with climate change, and regular weather patterns and poverty and migration and and all of these things, they always seem still in the future still decades off in the future, but from what you're telling us, it's now in India.

Protesters and reporters in India have been met with tear gas and opposition from the government. To date government leaders have failed to compromise with farmers and the more than 30 farm unions that support them despite months of talks. (Photo: Randeep Maddoke, CCO, Wikimedia Commons)

AHMAD: Yes. And that's something that I think a lot of people don't realize is that the climate crisis is already upon us, we're actually already living through it. If you're buffered from the environment to a certain degree, right? I mean, if you don't depend on rainfall or regular rainfall or regular, irregular patterns of rainfall, then you can kind of ignore it. If the food you buy is what you buy in the supermarket, rather than food you raise, then you don't see the impacts immediately. If you are not dependent on springs in the mountains, to grow your crop or to bring water to your house, it doesn't really matter that those springs are disappearing. But for developing countries especially, you are much more dependent on your environment. You are, in a sense much more connected to your environment so a small failure in your environment doesn't leave you with any backup.

BASCOMB: Omair Ahmad is the South Asia editor for Third Pole. Thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

AHMAD: Thank you for having me, Bobby.

Related links:

- BBC | “India Farmer Protests: How Rural Incomes Have Struggled to Keep Up”

- EcoWatch | “The Ecological Root of India’s Farming Crisis”

- The Wire | “The Climate Crisis Is The Foundation Of The Indian Farmers’ Protest”

- Oxfam India | “Move Over 'Sons of the Soil': Why You Need to Know the Female Farmers That Are Revolutionizing Agriculture in India”

[MUSIC: Sheila Chandra, “From a Whisper…To a Scream,” on Sheila Chandra, by Steve Coe/Martin Smith, Caroline Records/Indipop]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A federal court tosses out the Trump EPA secret science regulation, which would have undermined the use of public health studies.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Oumou Sangare, “Saa Magni” on Africa Fete, by O. Sangare, Mango Records]

Beyond the Headlines

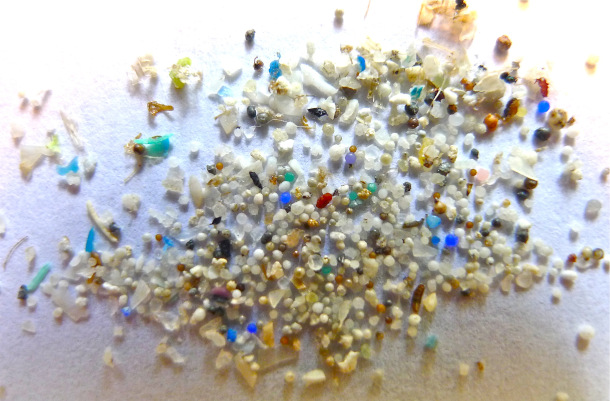

Microplastic poses a growing concern in oceans and aquatic life. (Photo: 5Gyres, Oregon State University, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Let's take a look beyond the headlines now with Peter Dykstra. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. He is on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hello, Steve. We're going to start with a study that was reported by Hannah Seo about fish farming and its plastic problem.

CURWOOD: There's a lot of plastic in the ocean, what's going on with fish farming?

DYKSTRA: There have been a couple studies out recently, notably one in the journal "Aquaculture," where scientists sampled twenty-six fishmeal products from eleven countries on four continents, plus Antarctica. And the only sample that didn't have plastic in it, in these fish and fish meal, was the one from Antarctica.

CURWOOD: And fish meal is what?

DYKSTRA: Fish meal is ground up fish and fish trimmings, sometimes mixed with some grain products that are fed to fish. If there are microplastics in the fish food, there will be microplastics in our seafood.

CURWOOD: So we're eating microplastics?

DYKSTRA: We're eating microplastics. The sort of good news is that the whole fish tends to have more microplastic in it. The muscle part, the part we call fillets has little evidence of serious contamination, although there are microplastics in every part of the fish that we consume. Most of the contamination is in other organs that are generally not eaten in our part of the world.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but there are many societies where people eat the whole fish, especially if it's a little one. All right, what else do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: A decision from a federal judge in Montana turns out to be good news for the Biden administration. A federal judge vacated the Trump administration rule limiting which scientific studies the EPA can use in issuing health-related regulations. What the Trump era EPA called "secret science," a really sinister sounding name, the long held practice that raw data can be used in some studies and be kept confidential, would end.

The “secret science” rule would have made it harder for the EPA to use environmental health studies that rely on the confidential medical data of participants. (Photo: TF3000, Pixabay, CC0)

CURWOOD: And how would you be able to do studies? I mean, a lot of studies have used health data, personal health data, I'm thinking of the one that showed how dangerous particulates from coal-fired power plants and diesel engines are, and also in pesticide evaluation, but people aren't going to agree to be part of a health study if their entire health record could become public.

DYKSTRA: That's absolutely right. And the other side of it is that if scientists insist on keeping that data secret under this Trump rule, they automatically would have invalidated use of the studies in making new rules to protect human health in the environment.

CURWOOD: But thanks to this judge in Montana, you say that so called "secret science" rule is now in the history books. Hey, let's go on to history. Now, at this point in our little chat, we typically will take a dip back into the volumes of history, and have you tell us what you see. And today it is?

DYKSTRA: I want to give you a little history of the environmental justice movement here in the US. It was considered to be born in 1982. There were protests in a rural, mostly African American county, Warren County, North Carolina, which was set to be the site of a PCB dump. The protests were so effective that the governor canceled the dump. The environmental justice movement was born. But February 11, 1994, environmental justice was finally recognized by the federal government, when President Bill Clinton signed an executive order calling for environmental justice to be a factor in any federally funded project. Now, President Biden has promised a renewed focus on environmental justice, but we'll see how that goes because it has been a long time since February 11, 1994, when the federal government first recognized the problem.

Our arrest & protest against environmental racism in Warren County NC in 1982 have evolved into an effective global environmental justice movement #WednesdayWisdom #EnvironmentalJustice #PCB #ToxicWaste #Receipts @EPA @unitedchurch @BlackPressUSA @ministter pic.twitter.com/xtU8fEWfFz

— Dr. Benjamin Chavis (@DrBenChavis) April 3, 2019

CURWOOD: Well, we've been at the racial problem in America since 1619, some folks would say. Thanks Peter! Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. Talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth website. That's loe.org.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Fish Farming Has a Plastic Problem”

- Aquaculture | “Fish Out, Plastic In: Global Pattern of Plastics in Commercial Fishmeal”

- The Washington Post | “Judge Throws Out Trump Rule Limiting What Science EPA Can Use”

- Continue learning about the environmental justice movement

[MUSIC: Simone Dinnerstein, French Suite No.5 in G Major, BWV816:III, Sarabande, by Johann Sebastian Bach on The Berlin Concert, Telarc]

Angry Birds and the People’s Climate Vote

Cassie Flynn, co-author of the UNDP People’s Climate Vote, drew inspiration to use gaming apps to deliver the survey when she saw almost everyone on subways playing on their phones. (Photo: Mussi Katz, Flickr, Public Domain 1.0)

BASCOMB: Now for a story about climate change… and Angry Birds.

[ANGRY BIRDS THEME SONG]

BASCOMB: That’s right, the mobile game Angry Birds. In perhaps the largest opinion poll on climate change to date, the UN used that popular game and others to reach 1.2 million respondents in 50 countries. 64% of them said they think climate change is a global emergency. The United Nations Development Programme ran what they call the “People’s Climate Vote” in high-, middle-, and low-income countries that together represent more than half of the world’s people. Notable exceptions to countries surveyed were China and South Korea. And using smartphone apps to reach respondents created significant barriers for people in lower-income countries with poor internet access. The creators of the survey say that despite its limitations, it yields insights into public opinion on climate change at a key moment when countries around the world are ramping up their pledges under the Paris Climate Agreement.

Cassie Flynn is a co-author of the People's Climate Vote survey and Strategic Advisor on Climate Change for UNDP and she joined Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

DOERING: So how did you come up with this idea to use mobile games like Angry Birds and Words with Friends to poll people all over the world on the issue of climate change?

FLYNN: Well, certainly when when you think about public opinion poll on climate, video games aren't the first thing that that you think of. But it comes from a place of really trying to reach as many people in the world as possible. And you know, in my work, I work with a lot of policymakers and a lot of ministers and heads of state, who are always really wanting to be very connected to the way people are thinking about how to solve the climate crisis. And that's what we really aimed to do with the People's Climate Vote, was to help people to really make their voices heard about how they see this, this being solved. And so it works like this. If somebody's playing a game, like Angry Birds, you know, you get those ads that pop up, and they're about 30 seconds long. And sometimes they're a game within a game and you can you can play it, or you can just wait and cancel it out when when it's time. We replaced that with a poll. And within that 30 seconds, we essentially asked people really two big questions. One was, do you think climate change is a global emergency? And then the second was, how do you want to solve it?

The UK Student Climate Network protesting the government’s lack of action at the Centenary Square, Birmingham, UK. The UNDP People’s Climate Vote collected responses from half a million people under the age of 18, a constituency that is typically unable to vote in regular elections. (Photo: Nick Wood, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: So Cassie, to what extent were there any results from this survey that really surprised you?

FLYNN: I think something that's really important out of this, and as I mentioned, you know, we really asked people just a few questions,. And one was, "Do you think climate change is a global emergency?" And then the other was, we gave people options for how they wanted to solve it. And we gave them essentially three of the biggest, most impactful policies across six different categories. So it was energy, economy, protecting people, transportation, farms and food, and nature. And what was really interesting about this is that people didn't pick just one or two. Like on average, they picked eight policies. And that is really amazing. Because what it tells us is that people aren't seeing, solving climate change as a silver bullet. They're not saying, you know, the one thing we need to do is climate friendly farming. That actually, it's climate friendly farming alongside protecting the ocean, alongside green jobs, alongside cleaner transportation. And this is really, really telling, that people really do see solving the climate crisis as a really broad-based, holistic, every-part-of-our-lives-needs-to-change kind of solution.

DOERING: Wow. I mean, of course, I wonder how much people are connecting the dots to some extent, because, you know, looking at the results, the policy that you had to promote plant based diets got, you know, the support of just 30% of respondents. That's compared to 54% for conserving forests and land. And I would note that conservation at the scale scientists say is really necessary, is really impossible without the world eating a lot less meat and dairy. So what does that disparity tell you about how people are thinking about these climate change solutions?

FLYNN: That's a great question. And we had, you know, two policies came down toward the bottom of the list, and one was insurance, and one was plant based diets. And I think there's a couple of things to think about. I mean, one is, we didn't ask people to vote against anything. And so it could very well be that on insurance or plant based diets, that people were just indifferent. The other thing is that people just may not know about these as being sort of big, big, broad brush things that that we need to do. And I think that there's a real opportunity for for education. There's real opportunity for helping people to understand what the link is. Why insurance matters after a category five storm hits. Why, you know, as you said, you know, we really can't solve this crisis without really thinking about how we eat and and what our diets are. The other part of it is that the way the question was worded was, what do you want your country to do? And so people may also have said, "Hey, a plant based diet is just something that I choose to do, I don't really need my country to do it. I don't really need my government to do it." So there's a lot of unpacking that we can still do that I think could really be useful in in really mapping out a lot of these solutions.

Out of 18 policies presented in the UNDP People’s Climate Vote, conserving forests and land was the most popular, with 54% out of 1.2 million respondents in 50 countries polled for the survey. (Photo: Lukasz Szmigiel, Unsplash)

DOERING: So there were some limitations to the survey, even though it was really pretty large by any standard, you know, 1.2 million respondents. But there were some gaps in representation. For example, Sub-Saharan Africa was barely represented in the data on whether the climate issue is an emergency. Just Nigeria and South Africa were represented there. And overall in the survey, China, which is the world's most populous country was, you know, missing. So why do these gaps exist? And how do you think that impacts the conclusions that we can really draw from the survey?

FLYNN: Yeah, well, you know, what's so interesting about this is that we saw really the digital divide in action. Gaming does reach, it has a reach that is that is so, so massive, but it doesn't have a reach toward communities that don't have an internet connection, or don't have access to a phone — all of the things that that you really needed to be able to participate in this. And and we saw this really vividly in some some communities. We saw this, in a lot of least developed countries, we saw this in a lot of the small island developing states around the world, that they just didn't have the strength of the bandwidth that that was necessary to be able to participate in this. And that's one thing that we're really trying to look at in terms of a phase two is, is how can we make sure that all of the people that are out there that want to participate in this can participate in this and something that we've we've really tried to focus on.

DOERING: So Cassie, how does the People's Climate Vote connect to the other work that your organization, the United Nations Development Programme, or UNDP, is doing on climate change?

FLYNN: So as we know that five years ago, in 2015, the world agreed to these 17 very ambitious goals, to alleviate poverty, to protect land and oceans, to have sustainable production and consumption, and tackle the climate crisis. And the program that I lead is something called UNDP's Climate Promise, which is the largest program in the world to support countries to develop and deliver their pledges underneath the Paris Agreement. Something that we noticed a lot was that they were very often asking for support for really making society feel like they own this pledge. That how do they, how do they include women and young people, indigenous communities, local groups? How do they make sure that they get everyone at the table?

DOERING: So what kind of a reception are you seeing so far from the international community and from governments around the world to this People's Climate Vote?

A policy to promote plant-based diets had the support of only 30% of the survey respondents, the lowest of all the mentioned policies. (Photo: Alexandr Podvalny, Unsplash)

FLYNN: Well, the response has been really overwhelming. I have to say, I woke up, the day that this was published. And I woke up to, you know, Greta had had tweeted about this, along with the G7 president had tweeted about this, along with a really famous guru had tweeted about this, and then it really snowballed from there. And we were so happy to see that this resonated. That this seemed to help coalesce voices around this crisis. And and we're hoping that this adds to this momentum that we need, because the decisions we have to make are massive. And when it comes to climate, doing something like transitioning toward renewable energy, or protecting people from category five storms, these are not small things. These are really really big decisions. And we're so happy to know that being able to coalesce people's voices around this and help deliver them to to world leaders has been very, very welcome. Many, many governments nearly every single government within the report, has really asked for a briefing on their information. We have, our phone is ringing off the hook about, you know, from governments saying, hey, we we saw this. We'd really be interested in knowing where our data came out what that looks like, and how we can incorporate it into into our climate pledges and just climate action in general. So it's been really, really encouraging, I have to say.

BASCOMB: That’s Cassie Flynn, Strategic Advisor on Climate Change for the United Nations Development Programme, speaking with Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- People’s Climate Vote report

- Click here to watch the press conference on People’s Climate Vote

[MUSIC: ANGRY BIRDS THEME SONG]

Bottlenose Whales in the Arctic

A bottlenose whale peeks out. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

CURWOOD: Life on earth likely began in the primordial soup of the ancient ocean. And humans still carry that original home in our bodies. The salinity in the plasma of our blood is remarkably similar to that of the ocean for example. And in a way, Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender says he longs to return.

Conferatur

A Pod of Bottlenose Whales

Hudson Strait

© 2020 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

From the far and the wide, at the fall and the waves’ rise a crescent moon of dorsal fin…

An archipelago of long forms…

Floating islands turning, wide...

The flash of pallid sun in the damp of Arctic Circle light…

Like magic!

They come:

Bottlenose whales in alongside.

One of the whale’s flukes breaches above the water. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Some pass under the keel. And finding none like us, return.

They raise themselves as much as they can to make their deep eyes shallow; to see as much as they can. As long as they can. As we drift. Engines cut. A listing hulk. And they follow looking up and up.

Their desire they cannot escape is my desire I cannot escape, to look, into the eyes, of the Other! This is how we speak, each to the Other. I do not want to leave here.

If I could I would abandon ship, stand on the rail and plunge…

If only my blood would not freeze...

If only I could hold my breath and dive, like them...

If only to quench my thirst I could drink brine....

We came from the sea and are still of it, our beating hearts the rocking of the tide, brought inside, so we could walk away. Having walked, there is no turning back.

An iceberg in the Davis Strait, just outside the Hudson Strait. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Flank speed into the starless dark we rove, the helmsman clinging to the wheel, the wavecrests snapping at our heels. Ice scrapes its nails along the hull, its prying fingers at the watertight doors.

And I am different than I was, Before.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Thanks to Adventure Canada

- Mark Seth Lender's website

- Find the field note for this essay here

[MUSIC: Cal Scott and Kevin Burke, “Evening Prayer Blues” on Across the Black River, by Bill Monroe, Loftus Music]

BASCOMB: Coming up – The little known relationship between the abolitionist Harriet Tubman and…. barred owls. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Black Violin, “Spring” from “The Four Seasons” (single), by Antonio Vivaldi, Universal Music Classics]

Modernizing Mobility

Public transportation is essential for equitable mobility, but according to the American Public Transportation Association, 45% of Americans do not have access to public transportation. (Photo: Jason Lawrence, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

Back in 2007 as the evening rush hour was getting underway in downtown Minneapolis, a bridge carrying highway I-35 over the Mississippi River suddenly collapsed. More a dozen people plunged to their deaths and nearly a hundred and fifty more were injured. That bridge collapse is a prime example of the nearly $2 trillion dollars worth of deferred maintenance and other broken parts of America’s infrastructure that President Biden has pledged to “build back better.” Not only is transportation a major part of infrastructure it is also linked to a quarter of US global warming pollution. So, Mr. Biden seeks to modernize mobility and infrastructure with a policy of getting the US to net zero carbon emissions by 2050, a goal that will take much longer to achieve than a single presidential term. Henry Cisneros is a former mayor of San Antonio who served in the Clinton Administration as secretary of housing and urban development. He is presently a tri chair of Connect SA, a non-profit that advocates for a $1.3 billion mobility infrastructure plan for the San Antonio-Austin Texas region. Mr. Secretary, Welcome to Living on Earth!

CISNEROS: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: So when it comes to transportation projects, I don't know if they're forever, but they certainly live on for generations. And Joe Biden has just proposed a $2 trillion plan to work with infrastructure, address climate, and there's a huge transportation transition he's calling for. How big a deal is this, do you think?

CISNEROS: Well, I think it's a very, very substantial initiative. First of all, the size of the infrastructure package overall, is designed to really make a difference on the $2 trillion shortfall of infrastructure that the American Council on Civil Engineering says, the country suffers. Two trillion dollars of inadequate, unrepaired just needed infrastructure in many, many realms of American life. The transportation piece is always one of the larger, and that's to be expected. A lot of infrastructure is expensive it relates to streets, city streets, and highways, it relates to mass transit, everything from buses, to rail, and increasingly new mediums like mobility on demand and transit for disabled persons. It also is bridges, and tunnels and airports and seaports, all of those are transportation related. So transportation infrastructure is very important and some people might say ell, you know, there are other important things in our lives, like health or education clearly are wages and economics. But I think it's clear that transportation, which we might call more broadly, mobility is as fundamental to the life of a city or people as any of the other things that I've mentioned because it makes all of those possible, the trip to work, the trip to school, the trip to medical care, in all forms. It also has a massive impact on the physical layout, land use policies, transit oriented development in our cities, and communities and it also impacts our climate. We know that if we had more mass transit and fewer cars on the road we would have less emissions and many of our cities that are in non attainment on air quality, would have that problem addressed. So while it's easy to dismiss transportation it really is fundamental.

CURWOOD: Now, the Federal Highway Trust Fund finances most spending on highways and even some transit, but the revenues from the trust fund come from gas and diesel taxes. I think that tax hasn't been updated since what 1993, or something like that. The country's current highway law is about to expire in September, and new transportation legislation is going to be enacted. So what are some of the key points of action, the Biden ministration, should incorporate in this bill in order to work towards an effective transportation transition?

The Biden Administration transportation infrastructure plan calls for 500,000 new EV plugs across the U.S. by the end of this decade. (Photo: Ivan Radic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

CISNEROS: Well, I think there's a number of key points one of them is the adequacy of the system, we have tended in the past, to try to plan transportation from the top down the highway fund or the rail fund, and just abide by the designs created in the silos of the cabinet agencies in Washington instead of really relating to what is needed across the country. It's time to inquire of local officials across America, "What are your needs? Has the pandemic changed those needs? How do they relate to your long term economic development?" So bottom up planning of our infrastructure is one thing that I think we need to do differently than we have in the past. Another is the application of technologies. We're now living with new technologies that were not existing, when much of the present infrastructure came into being. And that means everything from creating sensors in roads to address congested and direct people to less congested routes, for example, computer applications to create mobility on demand in the public sector, which means Uber and Lyft type systems but that arrive at people's doors, and then link them into the public transit system and they pay the same fares as they would in public transit because these are part of an integrated transit system, we're seeing those now being tried. And then just around the corner are autonomous vehicles to be used in mass transit. So let's leave ourselves open to the most advanced technologies. The third, I think, would be that we have to find adequate funding for all of this, as you were suggesting, in your question. So yes, the gas tax is a part of this but there will come a day when the gas tax actually is less reliable as a source of funding because we're moving to electric vehicles, and there'll be less gas guzzlers on the streets. So we'll have to think in terms of new sources that are needed to make these investments in our transportation infrastructure.

CURWOOD: So the President has talked a lot about jobs. And did I say that he's talked about jobs? And has he mentioned jobs? This seems to be the White House mantra these days. So what are some of the biggest jobs that could be created through the transportation transition? Do you think?

CISNEROS: Well, it's not just transportation, but it's other forms of infrastructure as well. It's the power system it's the water system. It's what's called social infrastructure, which is new kinds of social offerings like broadband and communications, the fact that we need to hospitals and clinics. The jobs are first of all, we have to design a lot, to build a lot so there's a lot of jobs to be had, in the anticipation, the lead up the preparation of a massive national infrastructure plan. The second is the actual construction, we need people who can build things. We need people who have the construction, crafts and skills and technological skills, to build things in the new iteration of infrastructure, which involves new technologies like integrating computers and communications into everything from roadways, to power grid, etc. And then thirdly, there's the operations of all of these things for the long run, where we need people who are more computer literate, and can make repairs to these complex systems. So the one thing about infrastructure is the jobs cannot be exported. These are not enterprises that could be sent to China or Latin America. These are jobs right in our backyard for our people in our communities. And the people who have been employed are potentially a new generation of talent. And people who have been on the margins of the economy before who now are brought in because they're provided the skills through training. So there's a lot a lot of benefits on the jobs front and on the income front and on the equity front.

CURWOOD: Mr. Cisneros, you've talked about using a carbon tax as a way to help finance this $2 trillion infrastructure plan. How effective Do you think the carbon tax would be?

CISNEROS: Well, it's obviously a controversial and we haven't actually utilized the carbon tax before. The plus side of a carbon tax is that it serves as a disincentive for the use of traditional carbon, fossil fuel based fuels, that is huge! If people recognize that their future is better served by utilizing electric vehicles and and other sources of renewables that's better for the country. So that's the major plus side. And then the second is revenues that are generated, can be used for advancing purposes in new technologies. Downside is it’s hard to pass, it’s new people are not attuned yet to it and it's natural to oppose anything that has the effect of changing the internal structure of an industry, and so there will be opposition to it. That is the hard part.

Japan’s high-speed trains, otherwise known as shinkansen, run at 199 mp/h (320 km/hr) and connect the largest metropolitan areas throughout the country. The United States has only one federally supported high speed rail in the works, the California High Speed Rail. (Photo: Tokyoform, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: So what are the health benefits of a transportation infrastructure $2 trillion project?

CISNEROS: I saw a graphic the other day that showed a bus on the street and next to it in the next lane, 60 cars. The point was, it would take 60 cars to provide transportation for the people that would otherwise be on that advanced rapid transit bus with multiple cars. So the first health benefit is to our air emissions, our air quality. Many cities are living with attainment issues where literally the air is dangerous for people to breathe because principally of automobile emissions. So one of the major dimensions of using renewables for fuels is they don't pose that health problem of carbon emissions. The second I would say is, to the degree that we can provide more equitable transportation, we can get people to health clinics and health centers, places where they can anticipate diseases that are not yet acute before they get their mothers that can take little children who don't have another means of transportation. So to the degree we create a truly equitable, far reaching, integrated transit mobility system, we create a more equitable society.

CURWOOD: One of the projects that's been mentioned in all of this is that to start to bring more high speed rail to the United States, and we've seen past efforts to do high speed rail, run into changing administrations. I'm thinking of what's been happening in California for example. How do you get a project like high speed rail going and keep it going, even if the administrations change?

Henry Cisneros is the former mayor of San Antonio and was the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in the Clinton Administration. (Photo: Department of Housing and Urban Development, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CISNEROS: Well, first of all, let me just say with respect to high speed rail, I am a big fan. It really brings a country together being able to give people a means of transportation rapidly and safely across the country. The United States effectively has not one single mile of bonafide high speed rail. We have some trains that run a little faster on certain routes for short periods of time. But the northeast corridor is an example that is not high speed rail, not compared to what the Japanese have had since the 1960s. The Shinkansen, which runs 150 miles an hour, and they have 1500 miles of it, or what exists in China, where they have trains running 200 miles an hour, and they have 6000 miles of it. So we're way behind and we suffer from not having it available. If people could take a train like that between New York and Washington just to pick one location. They would take people off the highways, they would decongest the airways between those places, or Los Angeles and San Francisco or Los Angeles and Las Vegas, or Miami and Orlando, Tampa, or the Chicagoland area and other Midwest cities there, north to Milwaukee, East Indianapolis, this would transform the country. So in an era when the precious cargo was grain, and food and petroleum, we had canals, like the St. Lawrence Seaway, like the Erie Canal. Today, when the cargo the precious cargo is human ability to sit down with others, to negotiate, to create, to collaborate, we want to move people.

CURWOOD: Henry Cisneros is the former mayor of San Antonio, Texas and served as Secretary of Housing and Urban Development under President Bill Clinton. Mr. Secretary, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

CISNEROS: Thank you.

Related links:

- Learn More about the Biden-Harris Administration’s transition plans

- CNBC | “Joe Biden’s Business Allies Discuss Ways to Pay for Infrastructure Plan, Including a Carbon Tax”

- NY Post | “Pete Buttigieg to Press for Infrastructure Plan During Senate Confirmation Hearing”

- San Antonio Business Journal | “Cisneros: ConnectSA Ready to Roll with Landmark Mobility Plan”

[BIRDNOTE THEME]

BirdNote®: Here Come the Barred Owls

A pair of Barred Owls in a lush forest (Photo: © Gregg Thompson)

BASCOMB: One of the easiest birds for humans to imitate might very well be the barred owl. BirdNote’s Mary McCann has more.

BirdNote®

Here Come the Barred Owls

[Typical hoot sequence of a pair of Barred Owls] The emphatic hoots of a pair of Barred Owls resonate in the still of a February night.

[Typical hoot sequence of a pair of Barred Owls]

So-called for the stripes on their breast, Barred Owls are among the largest owls in North America. They're also the most vocal. Their signature hooting sequence has been memorably described as “who-cooks-for-you?! who-cooks-for-you-all?!”

[Typical hoot sequence of a pair of Barred Owls] But this is just one of more than a dozen Barred Owl calls, ranging from a “siren call” to a “wail” to a wonderfully entertaining “monkey call.”

Barred Owlet in Seattle. The species is relatively new to the West and is now competing with the northern spotted owl. (Photo: sunrisesoup, Flickr CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

[Barred Owl monkey call] Although the Barred Owl’s calls have long been heard in Eastern forests, it is a relative newcomer to the western US. During the 20th Century, its breeding range has expanded into the North and the West, and down as far as northern California. The exact reasons behind the expansion aren't certain. But new riparian forests, fire suppression, and the planting of shelter-belts in the northern Great Plains are some of the human impacts that have likely played a role. No matter what accounts for the Barred Owl’s dramatic sweep across the continent, the bird – and its extraordinary voice – seem here to stay.

[Barred Owl “monkey call”]

###

###

Written by Bob Sundstrom

Call of the Barred Owl provided by The Macaulay Library of Natural Sounds at the Cornell Lab of Orni-thology, Ithaca, New York. Barred Owl [105433] recorded by G.A. Keller

BirdNote's theme music was composed and played by Nancy Rumbel and John Kessler

Producer: John Kessler

Executive Producer: Dominic Black

© 2015 Tune In to Nature.org February 2017/2019/2021 Narrator: Mary McCann

ID# 022607BADO2 BADO-01b

https://www.birdnote.org/listen/shows/here-come-barred-owls

Related links:

- Find this story and more on the BirdNote® website

- Learn more about the Barred Owl at All About Birds

- More on the Barred Owl at Audubon’s Field Guide to North American Birds

In Honor of Black History Month: Harriet Tubman and the Barred Owl

Underground Railroad conductor Harriet Tubman in the late 1860s. (Photo: Benjamin F. Powelson, Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

CURWOOD: And the barred owl also features in the story of the renown anti-slavery activist and underground railroad conductor, Harriet Tubman, a story we’d like to recall now during Black History month. Born in 1822 or so, Harriet Tubman escaped from slavery near Cambridge on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1849 to the free state of Pennsylvania, just a hundred miles way. She returned some 13 times to guide another 70 or so people out of bondage. Her knowledge of the woods and wetlands near Chesapeake Bay and its creatures was crucial to her success.

Under cover of night, Harriet Tubman would mimic the hoot of a Barred Owl to signal an all-clear to freedom seekers. (Photo: Travis Warren, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

[NATURAL SOUNDS OF THE REGION]

CURWOOD: Famously she used bird calls to alert freedom seekers if it was safe or not to proceed. To signal it was ok to slip away and join her, she would hoot like a Barred Owl.

[BARRED OWLCALL]

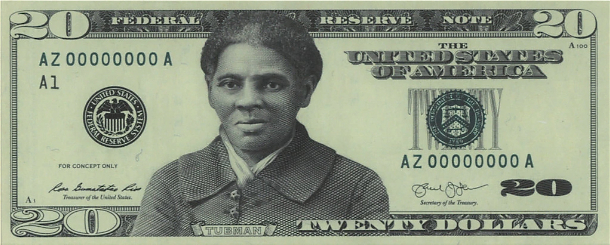

CURWOOD: Barred Owls like to roost in big trees near the water and typically hunt at night, so a person imitating one could blend in with nighttime sounds without raising suspicion. The cover of night and the light of the North Star combined to help Ms. Tubman guide her passengers on the underground railroad, and she fed and cared for them using her knowledge about medicinal and edible plants. Later during the Civil War, in the only such action by a woman that’s recorded, Harriet Tubman led a Union raid up the Combahee River in South Carolina that liberated some 750 slaves. She was also an activist for women’s voting rights and lived to 90 years of age. These days the Biden Administration is working to put Harriet Tubman on the front of the 20 dollar bill and perhaps move a statue of Andrew Jackson to the back.

[BARRED OWL CALL]

And maybe the Treasury Department should also consider having a barred owl join the Federal Reserve eagle.

Official $20 bill prototype featuring Harriet Tubman, prepared by the U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 2016. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Related links:

- Audubon | “Harriet Tubman, an Unsung Naturalist, Used Owl Calls as a Signal on the Underground Railroad”

- National Park Service article about the North Star to Freedom

[MUSIC: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qpW9QWi2Dbk 12-String Guitar Duet]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Paige Greenfield, Leah Jablo, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth