May 21, 2021

Air Date: May 21, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

EPA Updates Signs of Climate Change

View the page for this story

The US Environmental Protection Agency recently unveiled an updated set of climate change indicators after a four-year gap under the Trump administration. These data, collected by other government agencies and compiled on the EPA’s website, range from coastal flooding and wildfires, to longer allergy seasons. Senior climate scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists Kristina Dahl joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss what this climate resource means for policymakers and local communities alike. (07:48)

Beyond the Headlines

View the page for this story

For this week's trip beyond the headlines, Host Bobby Bascomb and Environmental Health News editor Peter Dykstra discuss a successful attempt to raise an endangered starfish in captivity. Then, the two look at Canada's choice to officially declare all plastics as toxic. Finally, looking back on a massive waterway project to the Gulf of Mexico that never paid off. (05:00)

Rescuing the Planet

View the page for this story

Climate change is placing stress on plants and animals to rapidly adapt but without intact habitat, that could become impossible for many. Tony Hiss is an award-winning author and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about his book Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth, which looks at several places across North America where communities are already working to protect habitat and biodiversity. (11:23)

“Fight Card”: Elk at Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

A big bull elk can grow to more than 5 feet tall at the shoulders. Add in another 4 feet for antlers and the thousand-pound animals can be an intimidating sight, especially for the younger male elk looking to replace them. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender has more. (03:38)

Brood X Emerges!

View the page for this story

Brood X is here at last: trillions of cicadas, underground for the last 17 years, are burrowing up through the soil and emerging in numerous Eastern and Midwestern states to transform, sing, and mate. Professor Gene Kritsky of Mount St. Joseph University joins Host Bobby Bascomb to explain the music of cicadas and the ecological benefits they bring. (11:06)

Cicada Cuisine

View the page for this story

Eating cicadas isn’t just for the birds: they’re also perfectly edible for humans. In fact, insects are rich in proteins and nutrients while having a much smaller carbon footprint than meat. Joseph Yoon is a chef and founder of Brooklyn Bugs, which specializes in insect cuisine. He joins Host Bobby Bascomb to show how to cook a Forbidden Rice Bowl that features seasonal spring produce and, of course, cicadas. (08:41)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210521 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Kristina Dahl, Tony Hiss, Gene Kritsky, Joseph Yoon

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

BASCOMB: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb.

After seventeen long years, brood 10 cicadas are emerging and giving a boost to wildlife. KRITSKY: It’s an opportunistic food pulse that’s just amazing. Raccoons, squirrels, birds, of all kinds, thoroughly enjoy periodical cicadas. And some people might not think that having more rodents would be a good thing, but in natural areas, more rodents mean more food for owls and raptors.

BASCOMB: Also, eating cicadas isn’t just for the birds.

YOON: Right now is the nymph season and when you open them, they’ve been gorging on tree and plant sap for 17 years so they’re just full of fat and muscle tissue so it’s really a delicacy and I’m happy to be preparing these for you today.

BASCOMB: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

EPA Updates Signs of Climate Change

Firefighters battle the Valley Fire in California, 2015. Wildfires are one of the 54 metrics tracked in the EPA climate data. (Photo: Jeff Head, Flickr, Public Domain)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The Environmental Protection Agency recently unveiled a newly updated database of climate change indicators after a four-year gap under the Trump administration. These indicators, collected by other agencies and compiled on the EPA’s website, range from coastal flooding and wildfires, to longer allergy seasons. They paint a picture of a rapidly warming climate that is already impacting American lives. For more, I’m joined now by Kristina Dahl, a senior climate scientist with the Union of Concerned Scientists. Kristina, welcome to Living on Earth.

DAHL: Thank you so much for having me.

BASCOMB: Now, this dataset includes many indicators of the climate crisis. How many were there? And can you briefly give us an idea of some of the things that were studied here?

DAHL: Sure. So, there are about 54 indicators of climate change that the EPA is tracking. EPA has maintained this website since about 2010 or so, with a notable break during the Trump administration. About a dozen of the indicators that they're now tracking are new, and they cover a whole range of different things. So you can see how things like US greenhouse gas emissions have been changing over time, how the temperature has been changing over time. And so there's the sort of basic climate change things to track. But then there's some really interesting ones, like the number of heat related deaths in the country, or residential energy use. And all of those are different views into how climate change is altering the earth system, but also our day to day lives. And, you know, the weather we come to rely on.

BASCOMB: You know, many of the indicators highlighted in this dataset really kind of explained some of the changes that we're already seeing. To what degree do you think this information sort of validates our lived experiences?

The East Pierhead Lighthouse in Michigan city stands surrounded by ice. Great Lakes ice cover is amongst the dozen new indicators included in the updated climate data. (Photo: Tom Gill, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DAHL: I think over the last decade or so people have begun to really notice the changes in the climate around them. For example, people living on the coasts and in particular, on the eastern seaboard of the US, have noticed an increase in the number of coastal floods each year. And these floods can happen even just during a sunny day when there's an extra high tide. And the data that is presented here really makes it clear that those changes are real, they're happening, and they're the result of sea level rise. I think that the data that's presented here really do show this picture, that brings data to what people are already experiencing and noticing. And hopefully, this data starts to connect the dots so that people say, Oh, this isn't just a strange thing that I've noticed over the last few years, no, this is the result of climate change.

BASCOMB: And was there anything in here that really struck you in particular?

DAHL: So for people who have been following the data on climate change, and who monitor headlines, there may not be anything here that's terribly surprising. But what's really impactful here, I think, is seeing it all together in one place. Usually, when scientists compile all of the information about climate change, it'll come out in a really wonky assessment, very technical, it's very dense. And it's not necessarily geared toward the average reader. What this EPA site is a place that compiles all that data in a really user friendly way. So each of their indicators has a nice accessible chart that goes along with it that's clear and relatively easy to read. So it's really a valuable clearing house that anyone can access for this kind of information.

BASCOMB: Was there any data that was missing here, in your opinion, or something that they should be looking at that they're not at this point?

Ragweed is a common allergen, and climate change is extending the length of the ragweed pollen season. Graphs and maps illustrating this phenomenon are available on the EPA climate indicators website. (Photo: Dendroica cerulea, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DAHL: I know that the EPA is hoping to add indicators over time. So hopefully, this isn't, you know, a set that we will see unchanging for the next few years. But I do think that there are things that they could add that would additionally speak to the changes, people are noticing. You know, one in particular that strikes me is related to hurricanes or tropical cyclones, we know that there are some really fascinating and destructive trends happening with hurricanes. And that's relatively recent data. But we now know, for example, that there's been an increase in the number of category four and five storms in the Atlantic Ocean. We also know that climate change is causing more of those storms to intensify rapidly. And that's important because as communities are trying to prepare for landfall for a hurricane like that, they need to know what kind of storm they're dealing with. I think that EPA would be a great place to compile some of that latest research and to present it back to the public so that they could see and understand that those changes that they're seeing in hurricanes, for example, are related to climate change.

BASCOMB: So this type of information was not made publicly available by the previous administration. Was it still being collected, though? I mean, did scientists still have access to this type of data?

DAHL: Yes, so most of the data that you will see on the EPA climate change indicators website is actually collected by other government agencies. So those agencies continued to collect the data. And if you had wanted to dig around on NOAA's website, or CDC 's website, you'd be able to find it somewhere. But EPA has really always been the clearing house for this information. And so it is playing that important role of putting it all in one place.

BASCOMB: And why do you think it's important to have it all in one place?

DAHL: So EPA has been tasked with regulating carbon dioxide as a pollutant. So it's important that EPA collect this data because we can't monitor or regulate something that we can't measure. So it is important for EPA to have this information collected, make sure it's a central part of the agency's work, so that it can do its broader work of trying to regulate CO2 as a pollutant.

BASCOMB: And for the public, I mean, what can they do with this information now that it is available in a more user friendly way?

The population of Black Guillemots in Alaska is one of the local datasets included in the EPA data. These birds depend on rapidly shrinking arctic sea ice. (Photo: Brian Gratwicke, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DAHL: There's a lot that communities could do here. And especially if you're living in a community where there's maybe not a lot of local support for collecting climate data, or you know, local energy around trying to push for climate action, anyone can access this data, you can look and see how something like temperature in your area has been changing over time, or how coastal flooding has been changing over time. And that may be useful information if you are trying to get your town to act on climate change. And this will help to show why, right? We're having these changes happening. They're affecting everybody's lives. And by having access to this data, people in any community can show the consequences of climate change. I think there are also some really interesting case studies here that could be inspiring to other communities. For example, there's indicators and stories around Great Lakes ice cover, or looking at a particular species of bird on Cooper Island in Alaska. And so looking at these kind of community level indicators, it could be inspiring to people who are saying, well, let's catalogue what's going on in our town, or we may have some source of data locally that's not widely available that would be interesting to incorporate into this website. So, I think there are a lot of opportunities for people to kind of connect with this data and hopefully use it for greater good.

BASCOMB: Kristina Dahl is a senior scientist for the Union of Concerned Scientists. Kristina, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

DAHL: Thank you so much for having me. It's been lovely

Related links:

- Climate Change Indicators in the United States at the Environmental Protection Agency

- The New York Times | “Climate Change Is Making Big Problems Bigger”

- Bloomberg | “U.S. EPA Issues First Climate Data Update Since 2016”

[MUSIC: The 442s, “Shibuya” on The 442s, by Adam Maness in collaboration with The 442s, self-published]

Beyond the Headlines

A sunflower sea star, Pycnopodia helianthoides, in a tide pool in northern California. (Photo: Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

BASCOMB: Well, it's time for a trip now beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Hey there, Peter, what do you have for us today?

DYKSTRA: Hi, Bobby, something that's a promise of a little good news in what's been an ecological disaster for the sunflower sea stars. They used to exist in the billions along the west coast, from Alaska down to Mexico, there's a wasting disease that has nearly wiped them out, maybe 90% or more of their population. These are beautiful little animals that instead of our normal image of a starfish, they might have 20 arms, and that makes them look like a sunflower in the Kansas prairie rather than an animal along the Pacific coast.

BASCOMB: Yeah, I was looking at some pictures of them. They come in all different colors, and they're really beautiful. What are researchers doing now to try to help them?

DYKSTRA: Well, they're trying to make sure they're beautiful for a long time, rather than the current pathway to potential extinction. Sunflower sea stars for the first time have been bred and raised in captivity. And they're hoping to eventually repopulate critical areas. This is happening in Washington State and the lab in the San Juan Islands. And it's some hope for a species that some people had begun to think may be gone forever.

BASCOMB: Here's hoping they can get somewhere with this research and, you know, help them bounce back. What else do you have for us this week?

Canada has declared plastic a toxic substance in order to implement a proposed ban on some single-use plastics. (Photo: Guda Oly, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Some interesting news on the regulatory front, not in the United States, but in Canada. Canada has declared that plastics are toxic, all plastics, and that may pave the way for restrictions. Some are hoping that it might under CEPA, which is the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, lead to a ban on single-use plastic bags from coast to coast.

BASCOMB: Wow, that seems like a really big deal. How are they defining it as toxic? How do they make that determination?

DYKSTRA: Well, we've heard so much and talked on this show about microplastics. And the fact that plastics last for all intents and purposes for ever, but they can break down in the environment to tiny levels that are consumed by fish, possibly consumed by land animals, including human beings. And a recent study concluded that humans ingest an estimated one credit card a week of plastics in our normal diet.

BASCOMB: Isn't that shocking? And of course, plastics come from oil and gas, which is pretty toxic itself in the environment.

DYKSTRA: And that's the climate change angle as well.

BASCOMB: For sure. Well, what do you have for us from the history books this week?

DYKSTRA: A 50th anniversary, May 25, 1971. The Tenn-Tom Waterway, the Tennessee-Tombigbee River Waterway was authorized by President Nixon, providing a huge shortcut for barge traffic from the Tennessee River to the Gulf of Mexico. The project ended up costing 2 billion by the time it was completed in 1985. In 2021 dollars, it's actually about 13 billion. So we're talking about an expensive project that has never paid off, because traffic on the Tenn-Tom Waterway from Tennessee through Mississippi and Alabama to the Gulf has been minimal. It's a commercial failure that we all paid for.

Construction crews work to excavate part of the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway in Mississippi in 1978. (Photo: US Army Corps of Engineers Nashville District, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Hmm, well, what happened there? Surely they should have looked at what they expected to get for traffic, and it just fell far short of that? I mean, what's the deal?

DYKSTRA: Well, rather than looking at reasonable expectations for traffic, instead, they were listening to lobbyists and members of Congress, representatives and senators along the route that saw it as a possible revival for some of the poor towns in Mississippi and Alabama, that could use the barge traffic and port possibilities as a way to lift up out of poverty. And who knows where else the money would have gone.

BASCOMB: I see. So it wasn't really the infrastructure project that it was billed as so much as just a economy booster.

DYKSTRA: A pork project, a boondoggle, but we're stuck with it now. They're only getting a tiny fraction of the traffic that goes up and down the Mississippi River each year. The Tenn-Tom was set up to compete with the Mississippi. It's been no competition at all.

BASCOMB: Well, let's hope we can learn from our mistakes there, I suppose.

DYKSTRA: As far as learning from mistakes, I gotta work on that myself as well.

BASCOMB: Don't we all? Alright, Peter. Well, thanks for those stories. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: Thanks a lot, Bobby. We'll talk to you soon.

BASCOMB: For more on these stories, including pictures of some of those sunflower sea stars, head over to the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “A Starfish Is Born: Hope for Key Species Hit by Gruesome Disease”

- Mother Jones | “Canada Declares Plastics Toxic, Paving the Way for Restrictions”

- WTVA | “$2B Tenn-Tom Waterway Yet to Yield Promised Boom”

[MUSIC: Steve Schuch, “The Hole In the Orange” on Crossing the Waters, by Steve Schuch, Night Heron Music]

BASCOMB: Coming up – We’ll take a look ways people are working towards the goal of protecting 30 percent of the earth by 2030.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailors for the sea dot org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Thelonius Monk Quintet, “Four In One” on Monk, Thelonious: Let's Cool One by Thelonius Monk, Blue Note]

Rescuing the Planet

The Boreal Forest is the world’s largest intact forest ecosystem and is a carbon sink. It’s estimated that if global warming exceeds the 3-5 degree Celsius heat stress and water scarcity could trigger extensive forest death and a dangerous release of the stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. (Photo: Kevin Owen, Flickr, CC BY NC ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

During his first few days in office President Biden announced the goal of protecting 30 percent of US land and water by the year 2030 with a long term goal of 50 percent by 2050. It’s an ambitious goal but one that scientists say is necessary if we are to avoid a mass planetary extinction. According to a UN report, roughly 1 million plant and animal species are already threatened with extinction including 40 percent of amphibians and a third of all marine mammals. Climate change is placing stress on plants and animals to rapidly adapt but without intact habitat, that could become impossible for many. So, in addition to slowing the trend of climate change, our best bet for preserving biodiversity is to protect habitat. And that is the focus of a new book by Tony Hiss titled, Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth. In it Tony takes a close look at several places across North America where people are already working to protect habitat and biodiversity. And he joins me now, welcome to Living on Earth Tony!

HISS: Thank you, Bobby. It's quite a pleasure to be with you.

BASCOMB: One focus of your book is the Boreal Forest in Canada and Alaska. Can you first please describe the Boreal for somebody who's never been there and give us a sense of the scale of the place and its importance.

HISS: You know, it's hard for a city boy like me to wrap my mind around a place like the Boreal even though I've now been there. It is perhaps the largest and most intact wildness left on planet Earth. It's way up at the top of Canada stretches into Alaska, it's 3,700 miles long, it's 1,000 miles from top to bottom. Extraordinary landscape, less cut over than the Amazon less cut over than the Siberian rainforest. And you get the kind of astonishment that we think people like Marquette and Jolliet sailing down the canoes down the Mississippi in 1673, found, or the Lewis and Clark found as they went West for Jefferson in the early 19th century. It's there, it's intact.

Longleaf pines once covered 90 million acres from Virginia to east Texas but today only about 5 percent of historic range remains intact. Marion Clifton Davis was a modern conservationist who bought tens of thousands of acres in the Florida sandhills and turned them into a private reserve, a project aimed at restoring back the Longleaf pine forest. (Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife, Flickr, CC BY ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: And you write in your book that, you know, the boreal forest is this massive, intact wilderness, which is so important for the biodiversity of the region of the world. But it's also sitting on a carbon bomb potentially, if things go wrong in terms of climate change. Can you tell us more about that?

HISS: Oh, absolutely. It's a place that seems to have two nicknames. One is North America's bird nursery because something like 3 billion songbirds and shorebirds fly up there every year to raise the next generation. But its second nickname is the Fort Knox of carbon, because there is so much carbon locked up in the trees in the soil in the peat under the soil that if it were all released into the air at once, it would be the equivalent of something like 37 years worth of fossil fuel emissions bursting into the atmosphere at the same moment.

BASCOMB: So it's obviously very important to protect for a lot of reasons. And I understand that the Canadian government is looking to indigenous people that have been living there for millennia to help with that, can you tell us more about how that's working?

HISS: These are landscapes that have been continuously inhabited by native populations for let's say, 10,000 years. No one knows these landscapes like they do. And suddenly their expertise is being called upon, because the Canadian government with their participation is now setting up these enormous reserves called indigenous protected areas. And they're actually asking these First Nations people to be the rangers of these parks, to be what they're calling the mukluks on the ground. So far, it's going very well and there are plans for enormous additions, sort of almost California's worth of additions over the next 10 years or more. The Canadians, meaning the white Canadians were not kind to their first American populations first. But they've been in continuous occupation in these lands so they're ready and willing to take on the role of becoming the new guardians and official protectors and rangers of these vast, vast, vast new reserves.

BASCOMB: Well, there are several sort of unsung heroes in your book. There's a man named M.C. Davis, who made his wealth through gambling and then turned to conservation. Thanks to him thousands of acres in the Florida sand hills have been preserved. Could you tell us a bit more about him and his efforts, please?

Image of Mark Anderson, the advocate for "resilient" landscape conservation and the Nature Conservancy’s Director of Science for the Eastern U.S. (left) and author Tony Hiss (right) on a visit to Sanderson Brook in the Berkshires in the wilds of western Massachusetts. (Photo by Andy Finton)

HISS: He was one of the most wonderful people I got to meet wandering around the continent for this book. M.C. as you said, was a self made multimillionaire from the Florida Panhandle and he always referred to himself as a dirt road panhandle kind of guy. And one day, he was stuck in a traffic jam in Florida on his way home, furious fuming looked around and saw a sign on a high school billboard that said, "black bear seminar" and he thought, well it can't be worse than this. So he peeled off the road went inside. He said there were a couple of old drunks, few Canadian tourists who'd gotten lost number hoping for some free donuts. And up on the stage, these two amazing women talking about Florida black bears, which is a subspecies of black bear and how they were threatened. He was hooked, he was fascinated. And the next day he sent them enough money for their work for the next two years. Which he said sort of scared them. Who is this guy? Where was he coming from? What did he want? Well, what he wanted he told him was a list of the 100 most important environmental books so he could get up to speed and he spent a year reading those books and then he said, now I know what I can do. The great habitat for these bears is what was once the signature ecosystem of the southeast, the longleaf pine forest, which had almost entirely disappeared because after the Civil War in order to raise money they started chopping down these magnificent forests. That's probably the reason why Scarlett O'Hara said I'll never go hungry again. And M.C. on the cheap bought up 51,000 acres of played out peanut farms and scrub forests and began replanting longleaf pine seeds half a million a year. By the time I met him, he was in year 13 of his project still looked a bit scruffy, I had to tell him and he said, that's okay we're in year 13 of a 300 year project.

BASCOMB: Wow.

HISS: M.C. unfortunately has since passed on, but he'd left enough money to endow that work for the next 300 years. So there it is the Nokuse Plantation, a wonderful place.

BASCOMB: That's amazing. I mean, gosh, if everybody could turn a traffic jam into something as positive as that imagine where we'd be?

HISS: Yeah well, we got enough traffic jams to get started on.

BASCOMB: [LAUGH] That’s the truth. Now, you say in your book that several people in the past have proposed this kind of ambitious conservation effort, you know, we could’ve had 50% of the earth by 1950 had it been taken more seriously. But to what extent do you think things feel different now? I mean, in one of his early executive orders, President Biden committed to 30 by 30, which is an incremental step to 50 by 50. Does that feel different? I mean, do you think we can actually work towards this goal now in a meaningful way?

HISS: Well, that's a great question Bobby, because this feels to me like an issue that's been catching up with us and it's suddenly accelerating. About 10 years ago, when I started working on this book, I had a chance to meet with Edward O. Wilson, the great Harvard conservationist and biologist who's been pushing biodiversity he's a great champion of biodiversity for years and years. In talking with him I actually came up with the phrase Half Earth which he then has been running with. And even then he was thinking, well, half Earth is a way of waking people up. It's what he was calling a BHAG a big, hairy, audacious goal. And he said, sometimes you have to just sound the trumpet, and see what happens. Well, as you just said, The Biden administration has now embraced protecting 30% of the US by the year 2030 and 56 other countries have signed on to this as a goal for themselves. There's going to be a meeting in Kunming, China in October, at which 196 nations are expected to embrace this 30 by 30 goal. So suddenly talking about 50 by 50 which 10 years ago, seemed outlandish, preposterous, nutty, seems almost commonplace.

Tony Hiss, an author, lecturer, and consultant on restoring America's cities and landscapes. He is the author of thirteen books, including Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth. (Photo by Michael Lionstar)

BASCOMB: So how does this goal of, you know half Earth and preserving wildlife and biodiversity fit in with the notion of preserving, you know, the biosphere more broadly?

HISS: Well, one of the most remarkable people that I ran across working on my book, a rather fierce eyed looking Russian biologist named Vladimir Yovanovitch Vernadsky. And he wrote a book in 1926, called Biosfera was the first really close look at the biosphere. And it's thanks to him that we sort of can now see that the biosphere has three essential properties. One is it's very ancient, 3.8 billion years old or older. It's immense when you look around the world, it's this layer of life circumscribes the world. But the third thing is its third dimension, its height, or rather, its lack of height. Almost all of life is contained within this small band, from the bottom of the ocean up to the top of Mount Everest, that's 12 and a half miles. If it was stretched out horizontally, it's a distance you could drive in 20 minutes, you could drive from one end of life to the other in 20 minutes. So this place that is home to all of us by its very nature, it's vulnerable, it's tissue thin. The few people who have managed to get beyond the earth in rockets and look back at it have all been struck by the fact that it's gorgeous, amazing and vulnerable. And this has been sometimes called the overview effect. I think now what we're being called on when what's emerging in us is, is seeing the same thing from down below more of an inner view effect. So it's within that context that all our decisions are made. And it's what's telling us to love what's here but also to be careful about any of the changes we make.

BASCOMB: Tony Hiss is the author of Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth. Tony, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

HISS: Thank you so much.

Related links:

- Click here to purchase Tony Hiss’ latest book Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth (Affiliate link donates to LOE and supports indie bookstores)

- NRDC | “'Indigenous Communities Lead the Way to Boreal Forest Protection”

- Tampa Bay Times | “'Epilogue: M.C. Davis Ducked the Limelight While Saving as Much Nature as He Could”

- Learn more about E. O. Wilson’s Biophilia Center located in the Nokuse Plantation that M.C. Davis purchased for conservation.

[MUSIC: Ed Mann & Brian Hand, “Bell Garden” on Global Warming, by Ed Mann & Brian Hand, Interworld Music]

“Fight Card”: Elk at Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada

A pair of young male elk locked in battle at Jasper National Park in Alberta, Canada. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

BASCOMB: A big bull elk can grow to more than 5 feet tall at the shoulders, add in another 4 feet for antlers and the thousand pound animals can be an intimidating sight, especially for the younger male elk looking to replace them. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender has more.

LENDER: Like a couple of boys blowing off some steam, a pair of young elk have decided to be sparing partners for the afternoon. Antlers are their fists, their hooves gripping a mat of winter grass the way Patterson and Mohammed Ali gripped that canvas deck. Balance is the basics. The hook and jab the bee. The butterfly the lockup, a well-articulated symmetry.

The “Champion of the World” bull elk bugles a warning. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

It starts out in mock anger like a friendly game of dice. Then someone rubs someone else the wrong way and the boys stop making “nice.” Eyes wide and bloodshot, they grunt deep in the throat and give it what they’ve got. It’s getting out of hand as a friendly exhibition fight turns into a grudge match.

So I get down in a pocket below the hill, like a referee looking low across the ring for an elbow an illegal punch a roll of quarters in that bony mitt, now that the velvet’s off the glove. The one losing ground, the one who’s on the ropes, he starts to whine. It’s looking bad. Probably not what they had in mind when they started this. Now there’s no choice.

Just before someone lands one but good and the other kid leaves with broken ribs, something drops it down a notch and they back off a little bit. All parts intact. Not jammed up in an unbreakable clinch the way it sometimes ends, out here.

Instead, they just… stand there. Trying to catch their breath, looking, out across that field over there where the Champion of the World is pretty much ignoring all of this. He’s the one who started it, prancing for his harem of an audience, reminding the boys of a whole wide world in which they haven’t got a chance. Eight, nine hundred pounds of bull elk, they stare at those muscles rippling as he walks, the confidence, the elegance! Both of them thinking more or less the same thought:

Access to females is what elk fights are all about. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Will you look at the rack on that guy? Man, he’d make a mess out of us…

But they just can’t help themselves.

They saunter over just to, you know -

And that big old bull raises his head and calls the way elk do, a whistling ringing of the bell by which he means, “Sonny boys, I’ve had enough of you.” And down the aisle he comes, a Flame of Pure Fire. And those two boys? They beat it past the cheap seats towards the woods, before that fire puts them out.

But then the bravest of the pair takes a last long look at the closest female of the bunch - a look you can read from way over here - thinking about the Contender that he wished he could have been, tonight!

BASCOMB: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Visit Mark Seth Lender’s website

- Special thanks to Destination Wildlife

- Read Mark's Field Note for this essay

[MUSIC: Alex de Grassi, “The Alligator Walks Sideways On Sunday” on The Revenge of Blind Joe Death: The John Fahey Tribute, by Alex de Grassi, Takoma Records]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Trillions of brood 10 cicadas are emerging across the Eastern US. We’ll have the details, and some recipes, just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Majid Bekkas, “Daymallah” on Reves D’Oasis: Desert Blues 2, by Majid Bekkas, Network Records (Network Medien GMBH)]

Brood X Emerges!

Brood X is emerging in May 2021 after 17 years underground. (Photo: Gene Kritsky, Mount St. Joseph University)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

[CICADA SYMPHONY SFX]

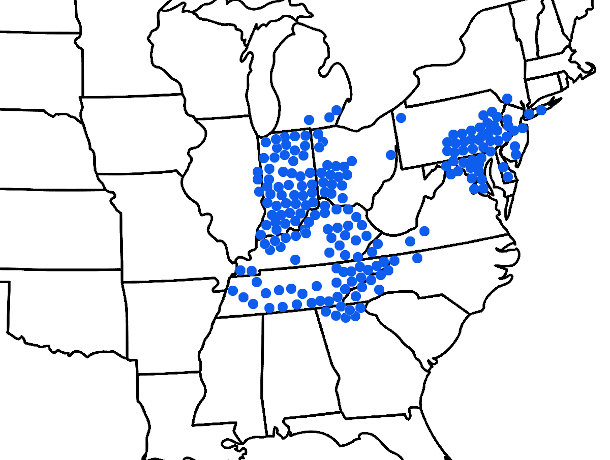

BASCOMB: Brood 10 is here at last! Trillions of cicadas, underground for the last 17 years, are burrowing up through the soil and emerging in numerous Eastern and Midwestern states. They’ll shed their nymphal skins, sing their deafening songs and mate. Then, they’ll die and it’s all over until 2038 when the next generation emerges from the ground. To learn more we called up cicada expert, Gene Kritsky. He’s the dean of Behavioral and Natural Sciences and a Professor of Biology at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati, Ohio. Gene, welcome to Living on Earth!

KRITSKY: Glad to be here.

BASCOMB: So, you're joining us from Ohio, which is ground zero for this explosion in cicadas. What exactly does it look and feel like to be part of that?

A cicada emerges from its nymphal skin. The adult cicada is initially ghostly white with tiny compacted wings, but soon turns black as its exoskeleton hardens. (Photo: Gene Kritsky, Mount St. Joseph University)

KRITSKY: Well, it starts with they start emerging in mass numbers. And you're waiting for that, you're taking soil temperatures, or you're looking at models. And that evening, when they start coming out, that's when the soil temperature is 64 degrees Fahrenheit; usually a day where you have a nice soaking rain, that really softens things up in the soil, and they come out. And you go out after dark. And you're hearing this crunching as they're falling from the trees onto dry leaves, for example. And you look at the trees, you watch these things climb up the tree, locking their legs into that vertical surface of the tree trunk, or a brick wall or fence, or what have you. And then the back of the cicada nymph splits. And you see this white space appear, and eventually it gets a little wider, and then the head capsule splits on the top. And then the whole adult pulls itself out of the old nymphal skin, wriggles is abdomen free. And there you have it, it's a separate adult now. It's got shriveled up little wings, it's creamy white with red eyes and two black patches behind the head. And then for the next half hour, 40 minutes, it starts expanding the wings by pumping fluid through it, and the wings get bigger and bigger and bigger. And then finally they look like, they're all held in place, tent-like over the back of the abdomen, just like a cicada should, except they're creamy white, with red eyes and black patches. And then it takes another hour and a half for them to actually turn dark and get the orange color to their wing veins, membranous veins, and turn into the typical adult cicada.

BASCOMB: Wow, so interesting. You know, but at the same time, it kind of seems like something out of a horror movie! I mean, all of these creatures just coming out of the ground at the same time. It's intriguing, but also kind of creepy in a way.

KRITSKY: Yeah, I can, I can see why you'd say that! I actually observed this in a cemetery one night. And all of a sudden, you're, here with all the, all the headstones or whatever. All of a sudden, you see that the ground is moving with these things. And they're actually climbing up the headstones and transforming into the adults off of the headstones. Yeah! [LAUGHS]

BASCOMB: So the cicadas are just about to hatch out now. What next? Tell us, please, about the full life cycle of cicadas once they emerge.

An adult periodical cicada. (Photo: Katja Schulz, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

KRITSKY: Sure, after they've transformed into the adult, they're going to climb to the top of the trees for about five days. It's really strange because for the few days after they first started coming out, you don't hear any calling. That doesn't start till about five days later after they've completed the hardening of their exoskeleton, and they're ready to fly and sing. Males gather in large numbers in trees, we call it a chorusing center, where all these males gather and start singing. Females fly into the, into the tree. A male sings; she responds by flicking her wings. If he hears that, he'll walk closer and call again. She'll flick her wings, he'll walk closer; and then eventually mating ensues. Mating can last several hours. And then after that is completed, the female will start laying her eggs within the next couple of days. She'll lay 500 eggs in the terminal growth of tree branches. And then she and the male die. Those eggs will be in the trees just under the bark. And six to ten weeks later, they'll start hatching. And the nymph wiggles its way free from the egg nest, and then just drops to the ground and they're gone. And it's almost instantaneous. And they'll feed on grassroots or other herbaceous roots for a few weeks. And then on New Year's Day, they'll be eight to ten, twelve inches below the surface, sucking on a tree root. And that's where they'll be for the next 17 years. While they're under there, they're not hibernating, they're not sleeping, they're not dormant. They're sucking on tree roots, they're growing. They molt four times during that period, they will probably, don't move no more than about a meter from where they first went into the ground. But they will tunnel around looking for tree roots and what have you. And then by year 13, they're in there, they've already molted now to their last immature stage. And so, for 17-year cicadas, they won't molt again, until they emerge and form the adult that'll occur in May of the year. And so that's the life cycle. Doesn't sound very exciting, but it's obviously been successful.

A map showing Brood X locations. (Image: Gene Kritsky, Mount St. Joseph University)

BASCOMB: So aside from the sheer number of them that come out, the other really distinguishing feature is the sound that they make. How do they make that sound, and do different species make the same sound? Or can you actually tell the difference from hearing them?

KRITSKY: Well, there are three different species of 17-year cicadas, and they can be differentiated by the color pattern of their abdomen, on the underside of the abdomen, but also by their calls. The chorusing and the individual calls are made with a structure called the tymbal. And this is a membranous structure that's ribbed, found just under the wings of the first abdominal segment. Inside the cicada male's body, there are muscles that are attached to that. And when they contract, they cause those ribs to buckle, which makes a sound. A good analogy: take a bendy straw, and pull it out and push it back in, and hear that little "zzzz". But do that now 250 times a second! The male abdomen is mostly hollow, it's mostly just an airspace to help resonate that as well. So that's the making of the sound. Females don't have a tymbal, so she is silent except for flicking of her wings, that's how she responds. Get them all together into one large group, and --

[CICADA SOUNDS]

KRITSKY: it's almost like a surreal experience. The largest species of cicada, Magicicada septendecim, it's the one that has the call, that's sometimes is referred to as sounding like the word -- "Pharoah"...

[MAGICICADA SEPTENDECIM CALLS]

Brood X cicadas mating in 2004: the generation that spawned the 2021 cicadas. (Photo: superbatfish, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

KRITSKY: To me, it's what a Foley artist would have used for the flying saucers in a 1950s science fiction movie. Now, Magicicada Cassinii, this has a series of buzz and clicks.

[MAGICICADA CASSINII CALLS]

KRITSKY: But when they're together in a large chorus, it sounds like, like -- "shhhhhh". So you have this high-pitched, sort of hollow sound with the flying saucers call, and then "shhh" below that. And you can hear those two tones very readily in chorusing centers. The third species, decula, is the rarest of all: five, maybe ten percent in some locations. And to me it sounds like a rotary sprinkler head, it's buzz and clicks, but it's --

[MAGICICADA SEPTENDECULA CALLS]

KRITSKY: And so if you're lucky to get all three, you could have, just blend them together. And that's what your full-fledged chorus would be. And then to get, to add a little more spice to it, make it about 96 decibels, which is on par with a rock concert.

[CICADA CHORUS]

KRITSKY: That's the music of a cicada symphony.

A grackle with a cicada snack. Periodical cicadas are so numerous when they emerge that they provide a huge feast for birds, squirrels, raccoons, snakes, moles and more. (Photo: Jen Goellnitz, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: So there are literally trillions of these insects that are emerging right now in the Eastern part of the United States. What kind of ecological role do cicadas play when they come out? I mean, it's a sudden influx of a species that hasn't been there for 17 years. How does that affect the ecosystem?

KRITSKY: Well, that's the neat thing about periodical cicadas. They are uniquely adapted to life in the Eastern deciduous forest. And if we were able to sort of wipe out all the periodical cicadas, I think the forest would still be here. But when they do emerge, and during the life cycle, they do some considerable good for the ecosystem. Unlike beavers, for example, they may not alter the ecosystem, but they're good for its survival. For example, when the cicadas are underground during those 17 years, they are turning over soil, and they're tunneling. When they emerge, they come out of these holes about the side and diameter of your little pinky, your little finger.

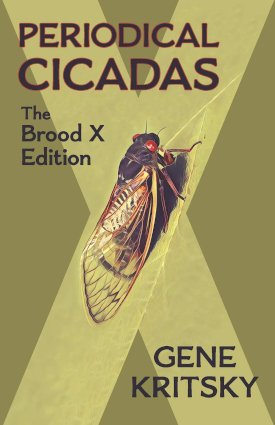

Gene Kritsky is the author of Periodical Cicadas: The Brood X Edition. (Image: Courtesy of Gene Kritsky)

And these holes persist, they don't all disappear right away. And that's like a natural aeration for the soil, and in the warm summer months, if you have a very heavy rain, in most cases, you have these heavy drenching downpours, and a lot of that water runs off into the creeks and the Ohio River eventually. But a lot of that water gets down those holes, it helps water those trees. So that's, that's beneficial as well. When the periodical cicadas come out and transform into adults, and even at the nymphal stage, they'll be providing food for animals. It's an opportunistic food pulse that's just amazing. Raccoons, squirrels, birds, of all kind, thoroughly enjoy periodical cicadas. And some people might not think that having more rodents would be a good thing. But in natural areas, more rodents mean more food for owls and raptors. And so it can help those populations increase for this year, which may help more offspring to go into the future. Then, all these cicadas die. And these carcasses collect at the base of trees. You get a nice morning dew from a cool summer night, the next morning, or a nice summer rain, get them wet; add some 90 degree temperatures, and these things rot. And they really stink to high heaven! And as they decay, the nutrients from those rotting cicadas go into the soil around the trees, helping the trees but also helping the cicadas that are feeding on those trees.

BASCOMB: What do you think people should do if they want to learn more about cicadas? How can people get involved?

KRITSKY: Well, the first thing to do is to download the app Cicada Safari. It was an app that I developed with the Center for IT Engagement at the university. What this app does is it asks you to help us map out where Brood X is. You go out, you get the app, and then got out on your own cicada safari. And go looking for where the maps tell us that it is, but also it's important to go looking for it where it once was or where, might be adjacent counties. Already we've had cicadas emerge this year from areas where we did not expect them. Go out there, find a cicada, you photograph it from your, your app and submit it. The value of Cicada Safari is it is a citizen science project where there's verification. We're tickled with this, we're expecting now 90,000 to 100,000 photographs this year.

Professor Kritsky takes a look at some adult periodical cicadas. (Photo: Courtesy of Gene Kritsky)

BASCOMB: Gene Krinsky is Dean of the Behavioral and Natural Sciences and a Professor of Biology at Mount St. Joseph University. Thank you so much for joining me today, Gene.

KRITSKY: It was a pleasure, thank you.

Related links:

- Learn more and become a citizen scientist with the Cicada Safari app

- Listen to Gene Kritsky’s Living on Earth interview about beekeeping in ancient Egypt

- Find Gene Kritsky’s book, Periodical Cicadas: The Brood X Edition

Cicada Cuisine

This is a forbidden rice bowl filled with wild rice at the bottom, fresh seasonal vegetables, cricket ramp kimchi and nymph brood X cicadas at the top. (Photo: Brooklyn Bugs)

BASCOMB: Well, eating cicadas isn’t just for the birds. They are also perfectly edible for humans. With a soft body and thin exoskeleton they are actually quite similar to shrimp, so similar in fact that people with shrimp allergies are often allergic to cicadas as well. To get some ideas for how to cook cicadas we called up edible insect advocate Joseph Yoon. He says pound for pound most insects offer more protein and nutrients than meat. They require far less food and water than raising livestock and they produce a tiny fraction of the amount of greenhouse gas emissions. Joseph is a chef and founder of Brooklyn Bugs, which specializes in insect cuisine. And since cicadas are plentiful now he’s cooking some up for us in his home kitchen.

YOON: Right now is the nymph season. And these guys are just a delicacy. When you open them, they've been gorging on tree and plant sap for 17 years. So they're just full of fat and muscle tissue. So a lot of people think that, oh, insects are all crunchy and stuff, but these are actually really juicy with a very thin layer of exoskeleton. So it's really a delicacy and I think that one of the things with the idea of eating insects is that people don't know what it tastes like and so they automatically think it's going to taste gross. And so I just really try to encourage people to keep an open mind because some insects are really just so neutral in flavor and will absorb so much of the flavor that you cook it in. So if you were to cook with aromatics, and add onions and garlic and ginger and peppers a lot of times that's what's gonna taste like with the little umami, earthy nuttiness that the insects will have as well. And you know, it's so wild because there are over 2,000 types of edible insects with wildly different flavors, different textures, and also just different functionality in the kitchen. So there's just, it's like wow! So many incredible ingredients and things to work with.

The ingredients for the forbidden rice bowl: (starting from top left, half an onion, cicada nymphs, carrots, garlic, asparagus, cricket ramp kimchi, chili pepper, gochu pepper, chrysanthemum, kennip and minari. (Photo: Brooklyn Bugs)

BASCOMB: Well, I understand that you are going to cook something for us today. What do you have planned?

YOON: Well, because the cicadas are such a spring specialty that only happens once in 17 years I thought it would be really awesome to create a forbidden rice bowl with brood X cicada nymphs. So we want to build a lot of flavor and so what we have is half an onion, some carrots and garlic, asparagus, red peppers, and so these will be fried up along with the cicada nymphs and bring a ton of flavor to it. This is a specialty from the summertime or for the springtime and this is cricket ramp kimchi that I made. I have a chili pepper and also a Korean gochu pepper, perilla leaves, minari and also some chrysanthemum.

BASCOMB: Wow.

YOON: So with the forbidden rice, the beautiful thing about this sort of black rice is that it has a lot more nutrients and it has this like incredible, nutty and fruity flavor to it and notes to it. It's just really so beautiful, the flavor that that it packs in there.

BASCOMB: Yeah, you can't go wrong there.

YOON: Alright, I'm just gonna start by cutting an onion here. [CHOPPING] I already chopped the asparagus and the carrots and now I'm going to chop up some of these peppers. This is a Korean gochu pepper. [CHOPPING] Now that we have everything all chopped up, we're going to get our pan hot at about a medium high. And we're going to add some vegetable oil and then start adding a lot of the aromatics and start building some flavor.

BASCOMB: Alright, so what do you need to add first?

YOON: We’re gonna start with some onions. [SIZZLING] All right, sounds good. Next, we're gonna add the carrots and garlic. You guys want all the peppers are only some of them.

BASCOMB: Yeah, let's do all of them. Why not? [SIZZLING]

YOON: All of them! So we're letting the onions caramelize little bit we're not getting caramelized onions but we just want to get some caramelization and bring out the natural sugars. The carrots are also sweating down. The peppers are adding this like, the smell of it is just intoxicating for me, I just absolutely love it. So let me just mix it around and let's go ahead and add the asparagus and red peppers. Salt and pepper. Alright, so let's go ahead and add the cicadas. I'm going to create a little pocket here add a little oil so we could get some good sizzle sounds for the cicadas. [SIZZLING]

BASCOMB: Alright in they go then.

YOON: So with the ramp kimchi, because it's like these long strands of ramp that I have here. I'm going to just cut them up into bite sizes so that they will work well. I'm just gonna go ahead and use a scissor. It's a very Korean thing. There's no Korean mom that I know that does not use use a pair of scissors in the kitchen. I'm not a Korean Mom. [LAUGH]

BASCOMB: But you probably learned from a Korean mom.

YOON: I sure did, yeah. I credit my mom for the best qualities that I have and for any ones that may not be as good, I blame myself for not not listening to her. Really, she's the best.

BASCOMB: Aww.

YOON: Okay, so let's get ready to plate up. What I'm going to do now I'm going to just start layering the chrysanthemum greens on like a third of the bowl. I'm going to put the minari on like another third of the bowl, and the perilla leaves on another third of the bowl. So I like the idea that we're also like hiding the forbidden rice, and it like lies underneath. And I'm going to surround this all with the cricket ramp kimchi. So I use cricket powder to thicken the kimchi paste instead of using a glutinous rice flour.

BASCOMB: Nice.

YOON: And so it adds both flavor and serves a wonderful function. Let's give it a taste test and make sure this is up to snuff here.

BASCOMB: Sounds great.

YOON: I’m gonna get some of the greens looks like I got two cicadas in here. Some of the veggies some of the kimchi a little bit of everything. Bug appétit guys!

BASCOMB: Mm hmm. What's the verdict?

YOON: It’s just so beautiful. Everything is so harmoniously balanced. It's a very special dish. And I'm so grateful to be able to share it with you guys.

BASCOMB: What I love about this too, is it's it's not only using cicadas which is maybe an unusual ingredient but something that's so abundant right now just this one specific time it's so abundant they're everywhere if you're in the right place, but it's also using, you know, asparagus which is in season this time of year and all of these unique greens which you could presumably forage for, you know, find them in specialty markets and that sort of thing. It's really you know, a celebration of the season and celebration of life in a way.

Chef Joseph Yoon is an entrepreneur, edible insect advocate and founder of Brooklyn Bugs. (Photo: Courtesy of Build Series New York City)

YOON: Yeah and it really is a celebration and I hold such a great value to the cicadas lives, the sanctity of their lives. So it's not something that I do flippantly in collecting them for some novelty, but we are really trying to find solutions for how we can reinterpret reimagine reunderstand insect protein. And so this presents like a wonderful opportunity for me and so I am just so grateful for me to be able to share this with your audience. Thank you so much.

BASCOMB: Joseph Yoon is an edible insect advocate and founder of Brooklyn Bugs. And by the way, if you find yourself inundated with cicadas about now but fresh out of cricket kimchi, Joseph says you can start by simply adding cicadas to any dish you already enjoy like pasta sauce, cook them up in a stir fry, or add them to a casserole.

Related links:

- Learn More about Brood 10

- Thrillist | “What to Know About Cooking Cicadas Before Brood X Emerges in Your Backyard”

- Learn more about Brooklyn Bugs

- Follow Brooklyn bugs social media accounts

- The Conversation | “Eating Insects Is Good for You and the Planet!”

[MUSIC: Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, “Sinister Minister” on Bela Fleck and the Flecktones, by Bela Fleck, Warner Bros]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Grace Callahan, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Natalie Seo, and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth