July 30, 2021

Air Date: July 30, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Eco-Justice40

View the page for this story

With yet another deadly chemical plant accident in a low-income neighborhood to underscore the issues, this time in Houston on July 27, the Biden administration has now rolled out details of its environmental justice plan called Justice40. The program aims to share at least 40% of benefits from federal climate and infrastructure spending with disadvantaged communities. Heather McTeer Toney served as the EPA'S Southeast Regional Administrator under President Obama and is now an environmental justice liaison for the Environmental Defense Fund. She joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the Justice40 Initiative. (09:22)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

For this week's trip beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about G20 nations providing more than $3 trillion in subsidies for fossil fuels despite their pledges to reduce emissions under the Paris Accord. Then, the two turn to the Great Salt Lake, which is becoming an environmental hazard as it continues to dry up. Finally, the two look at the 100th anniversary of the first crop dusting by airplanes and the birth of Delta Airlines. (04:37)

The Climate Emergency Warning from Extreme Weather

View the page for this story

As a slew of extreme weather events hits the headlines, the evidence of climate disruption is undeniable. Michael Mann, professor of atmospheric science at Penn State University and author of The New Climate War warns we are headed for dangerous thresholds of climate disruptions beyond the reach of adaptation to cope. He joins host Steve Curwood to talk about the links between extreme weather and human-forced climate change, why sea level rise could be counted in the dozens of feet by 2100, and how an unchecked climate emergency imperils human civilization. (18:52)

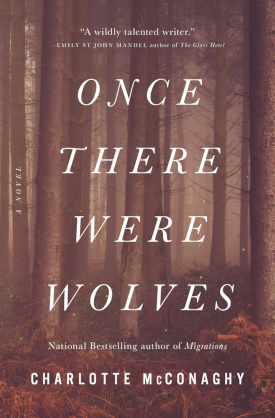

Imagining Wolves Returning to Scotland

View the page for this story

Charlotte McConaghy is the author of last year’s best-selling novel Migrations. She joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about her newest book Once There Were Wolves, a mysterious tale of a woman-led team working to re-introduce wolves to the Scottish Highlands, the people who confront them and the deadly toll of domestic abuse. (14:42)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

210730 Transcript

HOSTS: Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Michael Mann, Charlotte McConaghy, Heather McTeer Toney

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

Why extreme weather events from flooding in Eurasia to drought and wildfires in North America are becoming more and more common with the climate crisis.

MANN: Dangerous climate change has now arrived. The entire jet stream, that circles the entire hemisphere, has been impacted by climate change in a way that leads to more intense and more persistent extreme weather events on both sides of the spectrum.

CURWOOD: Also, a novel about rewilding the highlands of Scotland, starting with wolves.

MCCONAGHY: One of the things that I kind of found so fascinating was this ability they have to conjure these extreme feelings in people. They sort of generate a lot of fear. They also generate a lot of love.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Eco-Justice40

Industry and petrochemical plants in the region along the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans colloquially known as ‘cancer alley.' This image was taken by Heather McTeer Toney during a Moms Clean Air Force visit to the region. (Photo: Heather McTeer Toney)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

Around 7:30 pm on July 27th in the Laporte area of Houston, employees at the LyondellBasell chemical plant suddenly had to flee for their lives:

ABC 13 NEWS REPORTER: Here is what we know right now. About 100,000 pounds of acetic acid was released in the leak Tuesday night. Leaving 2 people dead, more than 40 people were injured there on scene. 30 workers were taken to the hospital following the leak.

CURWOOD: The LyondellBlassell incident was over so quickly there was no need to evacuate residents. But less than a week earlier residents within a half mile of a Dow chemical plant in the same area had to evacuate their homes after a chemical leak posed a risk of an explosion. Fortunately, no one was killed in the Dow chemical release incident. But according to Harris County officials, the closest neighborhoods to these incidents are low-income neighborhoods with white, brown, and black residents suffering a regular onslaught of potential chemical exposures. Polluting industries are routinely cited in low income, environmental justice, communities. Dealing with the risks of industrial chemical pollution in underserved communities is part of the Biden Administration’s plans to address environmental justice in part through infrastructure resources that are in the legislative mix now in Washington. The White House program is called Justice40 because it intends to ensure that at least 40% of the benefits from federal energy and environmental spending reach disadvantaged communities. The administration has named 21 federal programs that will be part of Justice 40 including clean transportation, affordable and sustainable housing, clean energy, and water management. Joining us now for details is Heather McTeer Toney; she served as the EPA's Southeast regional administrator under President Obama and is now an environmental justice liaison for the Environmental Defense Fund. Welcome to Living on Earth Heather!

MCTEER: Thanks so much. It's wonderful to be here with you Steve

Plastic nurdles are tiny pieces of plastic mostly manufactured from ethane cracker plants which are mostly located along low income black and brown communities. (Photo: Mark Dixon, Flickr, CC 0 1.0 Universal)

CURWOOD: So what would the 40% look like? And how is this going to be accounted for do you think?

MCTEER: So that's a great question and I think it's one of the things that the initial guidance is beginning to show us what is the roadmap and what is the outline. The White House engaged a panel of experts, and they're called the White House Environmental Justice Advisory Council or the WHEJAC and these are environmental justice leaders from all walks of life, all parts of the country that represent a very good segment of the American population concerned about environmental and climate justice. And through their advice, we now have an implementation guidance for how we're going to go about seeing the Justice40 implemented. Now I have to stress this is not just for one part of the federal government. This is to ensure that every single agency within the federal government is utilizing benefits to help disadvantaged communities and really sort of spur economic development. So while the federal government is giving us a roadmap it's still incumbent upon us in the communities that's mayors, city council members, state legislators, churches, schools, it's incumbent upon all of us to actually follow the roadmap. So there's some partnership here that is required. And this initial guidance is showing us a number of pilot areas that could potentially be used to start spurring both economic green development, but also really looking at how we can leverage these investments, reduce pollution in communities, and at the same time, think of it as a catalyst for both clean energy jobs, energy efficiency, and moving communities into what you know, we think of now in terms of a green future.

CURWOOD: So you've been the mayor of a town, of a city of Greenville, Mississippi. So talk to me about some of the key areas that this initiative is going to focus on that local government will want to engage with.

Justice40 includes a Flood Mitigation Assistance program, which is a competitive assistance program that provides funding for states, local communities, Federally recognized tribes and territories. The funds can be used to reduce the risk of repetitive flood damage. (Photo: Michael Land, Chesapeake Bay Program, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

MCTEER: A great example is the sections on training and workforce development combined with remediation and reduction of legacy pollution. There are communities across this country that have dealt with historic pollution, I mean, generational where they have, quite frankly, lived under a cloud of pollution. And so legacy pollution is something where we're talking about reducing these impacts. Well, this Justice40 initiative has funding that is specifically targeted to reducing legacy pollution through things that we know like Brownfields redevelopment or superfund sites, but also things like, you know, reducing farmworkers exposure to pesticides, or reclaiming abandoned mines, and capping orphan wells, which is very important in terms of reducing overall carbon emissions in our country and benefiting our planet. At the same time as a city leader, I would love to be able to take that money and funding and leverage it with training workforce development because while these are good things to do, you still have to educate people in the community on how to do it, and train people in smart technologies and new jobs that can come in and replace some of the things that were the cause of legacy pollution. And so that's where the training and workforce development dollars come in, to increase training for good paying jobs around energy and efficiency. This is something that goes to benefit not only people who are looking for a job, but also employers as a way to give them benefits. And it includes participation of some of the key parts of our community, which include youth or formerly incarcerated individuals. And I love the fact that this Justice40 plan actually identifies in a circular way parts of our communities that can work together.

CURWOOD: So some polluters are very powerful. And I'm thinking of a little further south on the Mississippi River from where you're talking there, a place that's colloquially known as cancer alley. There are more than 100 petrochemical plants along there where people in fenceline communities, often people of color, and with very high cancer rates and other health issues, have for years been looking for justice. This is where they settled and where they want to raise their families and the industry pollution has made it very tough. How do you think President Biden's Justicefor40 initiative will deal with problems of, let's talk directly about cancer alley?

The Justice40 initiative includes a Rural Energy for America Program for the Department of Agriculture, which provides guaranteed loan financing and grant funding to agricultural producers and rural small businesses for renewable energy systems or to make energy efficiency improvements. (Photo: Daxis, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

MCTEER: You know, I was there for Juneteenth. I and a few other members from Moms Clean Air Force, we were walking up and down the neighborhoods to have conversations with folks--identify not only how we could be of help, but also you know, what were some of the concerns straight from people as they're experiencing it every day. And the things that I heard were not only a need for reducing the pollution and finding ways to put a moratorium on new permits and new facilities concerns around air pollution. But future focus concerns around what are my kids gonna do? What will my grandchildren have as a replacement for jobs, as we are shifting the focus to more things that are pollution free, and less and fewer plastics? I think you said it, right. You're talking about some major major polluters, big companies and industry that are located not just in cancer alley but across the globe. And so it's a true David and Goliath story. And if you've ever been down a cancer alley, you know it's almost breathtaking when you go across the bridge and you just see all of these facilities, you can literally see the change in the air. Well, it's incumbent upon all of us to protect the rights of all people where they are as they exist and ensuring that they have access to clean air, clean land and clean water. And this does that in part by making sure that folks do have the resources that they need to help to reduce that impact.

CURWOOD: So as we're speaking, there have been discussions on Capitol Hill about an infrastructure bill. And what do you see as the intersections when it comes to addressing climate justice and advancing infrastructure legislation?

Heather McTeer Toney is former Mayor of Greenville, MS and Southeast EPA Regional Administrator during the Obama Administration. She currently leads the field program for Moms Clean Air Force. (Photo: Courtesy of Moms Clean Air Force)

MCTEER: I think it has to be a priority for all of us, because the infrastructure is tied to not only our win on climate and really reducing overall global emissions, but also job creation, economy and the future of our country and our children. This infrastructure bill, what it does is it sets us up for a solid future and it is necessary. The Biden administration put forth a plan that is not just bold but is necessary. So I want to definitely see a strong bill come out. But I also recognize that we have to continue working to push and make sure we have investment that's coming from not only all sectors of government, but even our private businesses, philanthropy and our communities. It's going to take all of us.

CURWOOD: Heather McTeer Toney is a former mayor of Greenville, Mississippi Regional Administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency, and now serves as environmental justice liaison for the Environmental Defense Fund. Thank you so much for taking the time with us today.

MCTEER: Thanks so much.

Related links:

- Learn more about Justice 40

- Scientific American | “How Biden’s Environmental Justice Order Might Work”

- E&E News | “Exclusive: White House Details Environmental Justice Plans”

- Learn more about Heather McTeer Toney

- The Guardian | “Chemical Leak in Houston Facility Leaves Two Dead and 30 People Hospitalized”

- AP News | “New Infrastructure Bill Must Focus on Climate Activists Say”

- The New York Times | “The Infrastructure Plan: What’s In and What’s Out”

- ABC 13 | "2 dead, 30 hospitalized in chemical leak at LyondellBasell chemical plant in La Porte"

[MUSIC: Sam Ross Trio, “City Stroll” on Live at the Mira Room, by Sam Ross, self-published]

Beyond the Headlines

The Carmichael Coal Mine in Queensland, Australia. (Photo: Cameron Laird, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

CURWOOD: Time now to take a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. He is on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Peter, what's going on? What do you have for us today? And how are you?

DYKSTRA: I'm doing fine, Steve. And I've got some news from the G20. The 20 most affluent, most influential nations in the world. There's a report from Bloomberg New Energy Finance, it's a little think tank that's become an influential voice in tracking clean energy and climate change related issues. Bloomberg NEF says that the G20 nations are engaging in reckless subsidies for fossil fuels, oil, coal gas, despite their pledges to address climate change. $3.3 trillion in subsidies in the last five years.

CURWOOD: Since Paris, in other words, having pledged to cut back at Paris. Nonetheless, they spent over $3 trillion on subsidizing fossil fuels. Who were the bad boys here?

DYKSTRA: In terms of percentages, the nation that's done the worst is Australia. Their subsidies, mostly for the coal industry, have grown by 48%. Australia is making a healthy living these days exporting coal to India and China. But number two on the list, getting the silver metal is the United States of America. We'll give a little gold star to the UK because they've actually reduced their subsidies for fossil fuels.

CURWOOD: Well, thank you, UK! And no surprise about the US since most of the last five, six years since the Paris Agreement was struck, we were out of it. What else do you have for us today?

Shorebirds fly over the Great Salt Lake in Utah. (Photo: I.M. Stile, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

DYKSTRA: Here's something that's shrinking. And that's the Great Salt Lake. That beautiful, picturesque body of salty water in northern Utah in the middle of the desert has reached its record low levels ever. That concerned scientists. Number one, the Great Salt Lake is a very important stopover for migratory birds. But also when the lake bed dries up, there are toxic metals and other substances that blow around as dust that are unhealthy for humans, migratory birds and every other form of wildlife.

CURWOOD: And to what extent is the Great Salt Lake a source of salt? That is, the sodium chloride, the stuff that people can put on their food, and elements like magnesium?

DYKSTRA: Magnesium, other elements, there's actually a market for brine shrimp. One of the things that migratory birds eat, but also there's a market for them out there among humans. The Great Salt Lake also impacts weather in the region. Much like the Great Lakes, it can create lake-effect snowfall, which is something that the ski resorts of Utah depend upon.

CURWOOD; Let's turn now to the history books and if you flip open one, tell me what you see.

DYKSTRA: An august 100th anniversary, August 3rd, 1921 to be specific. The first crop dusting aircraft is flown by Lieutenant John Macready, who dusts a field of catalpa trees near Troy, Ohio, using lead arsenic, what can possibly go wrong, to kill caterpillars?

Lieutenant John Macready (right) and Etienne Dormoy (left) stand in front of the first aircraft used for crop dusting on August 3rd of 1921. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

CURWOOD: Yeah, I guess if the lead didn't get them, the arsenic certainly did.

DYKSTRA: Yeah, one of the biggest operators in the south, where crop dusting really caught on due to the boll weevil infestation, started in 1925 in Macon, Georgia, not too far from here. Huff Daland Dusters Incorporated did a booming business, not just in Georgia, but in the Mississippi Delta. There they started a passenger and air mail service, Delta Air Service in 1928. They pretty soon after got out of the crop dusting business. So you're airborne pesticides don't have to change planes in Atlanta for one of the world's largest airlines.

CURWOOD: All right. Well, thanks, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News, that's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. We'll talk to you again later this summer.

DYKSTRA: All right, Steve, thanks a lot. We'll talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on these stories on the Living on Earth web page. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Guardian | “‘Reckless’: G20 States Subsidised Fossil Fuels By $3tn Since 2015, Says Report”

- Fox: Salt Lake City | “Great Salt Lake Hits All-Time Historic Low”

- Learn more about the first cropdusting airplanes and John Macready here

[MUSIC: John Kirby, “From A Flat to C” on 52nd Street Swing: New York In the ‘30s, by Billy Kyle, Decca Jazz/MCA Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up, why extreme weather events are becoming more common with the climate crisis. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at SailorsForTheSea.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Edgar Meyer, “Roundabout” on Edgar Meyer, by Edgar Meyer, Sony Classical]

The Climate Emergency Warning from Extreme Weather

Early climate models may have underestimated the timing of the emergence of extreme weather events like heat waves and floods. This summer’s severe flooding events in parts of Europe, China, and the United States are a wake-up call as policy makers, scientists, and citizens consider the urgent need for climate adaptation and mitigation. (Photo: Ryan Johnson, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

Extreme, record breaking, weather is happening around the world. Thousand-year floods are drowning Europe and Asia. And exceptional drought and unprecedented heat has been broiling western North America, sparking wildfires and degrading air quality for thousands of miles. Climate disruption is making such events much more likely. That according to new research published in Nature Climate Change that calculates heat waves that shatter temperature records by 10 degrees Fahrenheit are up to seven times more likely over the next three decades, and even more likely in the years beyond. That’s under a scenario in which too little is done to curb emissions. And as the world prepares for the UN climate summit in Glasgow Scotland in November, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, or IPCC, is finishing up its latest report on climate science, impacts, and ways to respond. Michael Mann is an atmospheric science professor at Penn State University who has worked on similar studies and has contributed to IPCC reports. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Michael!

MANN: Thanks, Steve, it's great to be with you.

CURWOOD: Now, you and others have recently published studies saying that we are in for some record-shattering heat becoming far more frequent, why and how?

MANN: Well, you know, at some level, it's pretty basic: you warm up the planet, you're going to get more frequent and intense heat waves. And that's what we've seen. Now, this latest study uses climate models to try to estimate just how frequent these sort of record-breaking heat extremes, like we've seen recently, how frequent they're likely to become. And one of the things that they show is that when you have a period of rapid warming, then you're more likely to see records broken by very large amounts. Again, it's perhaps somewhat intuitive, but they have nonetheless demonstrated this rigorously using climate model simulations.

CURWOOD: Well, yeah, so tell me, I mean, about this extreme weather we're seeing right now. I mean, we have of course, the record heat in the Northwest. Oh, but maybe it is raging drought in the West? Or is it raging fires in the West? Or is it thousand-year floods in, in Europe and China? In essence, what's going on? Why suddenly, does Mother Nature seem to be really focusing on this climate disruption thing?

MANN: Yeah, well, you know, what's happening -- you know, it feels like it's all accelerating. But in fact, what's really happening here is that the signal now is becoming large enough that we can see it play out in real time. You know, a decade ago or more, we sort of had to tease out of the data, the impacts of climate change, you sort of really had to squint to see them in the data; today, you no longer have to do that. The impacts have become, again, so profound, that we can see that these weather events, these extreme weather events that are playing out right now across the Northern Hemisphere this summer, have no precedent as far back as we have records. Now, this study, this recent study that, you know, argues that we're likely to see even more and more record shattering weather extremes. Ironically, that study makes use of climate models that don't completely capture some of the dynamics in the real world that are responsible for some of the events that we are seeing. This Pacific Northwest heat dome, for example; part of what was going on is that the jet stream has slowed down, something that's predicted to happen as we warm the planet. And weather systems tend to get stuck in place, and they grow in amplitude, and they grow in magnitude. And this is actually an effect that my co authors and I have been studying over the past few years. And it has to do with one of the subtle impacts about climate change and how it changes the behavior of the jet stream. And this particular impact is not well captured in current generation climate models. It involves processes that aren't very well captured by the models. So the models, if anything, are actually underestimating the impact that climate change is already having on these extreme weather events. And the reason that we see, you know, huge floods in one place, wildfires and heat waves in another, is because the entire jet stream that circles the entire hemisphere has been impacted by climate change, in a way that leads to more intense and more persistent extreme weather events on both sides of the spectrum.

CURWOOD: Michael, sometimes people point out that nature tends to move in quantum leaps. You know, one day you have a caterpillar, another you have a moth; if you're talking physics, you know, an electron's on a p level, another day, it's on an s. So how much does this affect what's going on, what we're seeing in terms of climate disruption, because, as humans, we think of things, you know, gradually changing rather than having quantum leaps. Which are we headed for, do you think?

The upcoming sixth IPCC report will include updated projections and commentary on extreme weather events and sea level rise. When it comes to IPCC reports, premature leaks are common, but cherry-picking the data before the reports are finalized can warp the public perception of the climate crisis. (Photo: Yves Nevens, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MANN: Yeah, well, it's, you know, an interesting choice of words to bring quantum mechanics into the conversation. And of course, my background originally was in theoretical physics, and I once studied quantum mechanics. But ironically, this behavior that I'm describing about the jet stream where it gets locked into place, and these wiggles become larger, and so the high and low pressure centers that are associated with these extreme weather events become deeper. It turns out that, to actually solve the physics of that problem, you end up using the same mathematics that was developed in the early 20th century to solve certain problems in quantum mechanics. So it turns out, the mathematics of waves that describes the behavior of matter at the smallest scale, is relevant to extreme weather events that are happening at the planetary scale. But you know, you've underscored something else which is very important here, which is our perception. Our perception does have thresholds, and impacts have thresholds. You know, at a certain point a flood is so bad that it breaks the dams, it rises over the levees. And so there are these thresholds, where when an event becomes extreme enough, it becomes so hot, for example, that human beings simply can't be outside without suffering severe health impacts. As these events become more extreme, we start to exceed some of these sort of societal and sort of behavioral thresholds. And so all of a sudden, we're talking not just about an extreme heat wave, but a deadly heat wave. All of a sudden, we're not just talking about a terrible flooding event, but the worst flooding event that China has ever seen. And it feels like we've gone through some sort of threshold in the way climate change is proceeding. But it turns out, even if climate change proceeds smoothly, the impacts and the responses to it can go through these abrupt thresholds. And that's one of the things that we fear, because there are potential climate tipping points that we worry about, like when the ice sheets give way, and the collapse of the Greenland or West Antarctic ice sheet becomes unstoppable. That's a threshold, and then, you know, we are subject to meters of sea level rise, and there's nothing we can do about it anymore. There are these potential tipping points that we are nearing. But there are also tipping points in our ability to adapt to the changes that we're witnessing, in our adaptive capacity and in our resilience, and that's something that we really have to worry about.

CURWOOD: Folks sometimes like to point out that the human impact on the climate and understanding it is an experiment that's never been done before, and we're gathering the data in real time. So we are facing surprises, surely, right, Michael?

MANN: Yeah, and unfortunately, they're not going to be welcome surprises. The surprises that are in store are some of the extreme weather events we've seen this summer, where some of the scientists who have been studying this stuff for years, say, "I never actually thought I would see anything like this, you know, I studied this on paper, I studied this in climate model simulations." But all of a sudden, we are witnessing the profound impacts of the warming of the planet. There is, you know, no question that we are dealing with a whole new level of threat. And you know, it's, it's right when people call the climate change problem a crisis or an emergency; well, it's reached that level. And it's reached that level, in part, because what we've never seen before, is, you know, a population of nearly 8 billion people on the face of the planet, competing for this diminishing food and water and space. And so the impacts of climate change really test our capacity as a civilization to continue to operate, when the conditions upon which our societal infrastructure have been built, and are based on suddenly no longer apply. If we allow the warming to proceed, then we will exceed our adaptive capacity as a civilization. So that is a potential future, societal collapse is a potential future. But it is not yet guaranteed as our future, there is still time to make sure that that isn't our future. But we have to decarbonize our economy now, rapidly. We've got to bring global carbon emissions down by 50% within the decade, if we are to have any chance of averting that one and a half degrees Celsius, nearly three degree Fahrenheit danger level.

CURWOOD: You outline what we should consider in terms of mitigation, that is reducing emissions. But what's to be done, what can be done in terms of adaptation? What do we already need to do?

MANN; Yeah, so we need to be careful that adaptation isn't used as a crutch for, you know, downplaying the importance of mitigation, of reducing carbon emissions. And there are some politicians who love to talk about resilience and adaptation, and hate to talk about mitigation. Because the fossil fuel industry doesn't want to hear about mitigation. They don't want to hear about decarbonization. They would rather say, look, we just have to adapt to the changes that are coming. And look, there is a certain amount of climate change that's already baked in. We're seeing it. We're already there. Dangerous climate change has now arrived. In the very best scenario, we're dealing with a new normal, where we have to fundamentally adapt our infrastructure to deal with these heightened threats. And we're seeing that right now. And especially those, you know, who have the least resources, the poor, folks in low income communities have the least resilience, the least resources, they're the ones who are seeing the greatest impacts. And so when we put it all onto adaptation, we're putting it on the poorest and those with the least resources. So yes, we need to provide resources, especially to those frontline communities, so that they can deal with the impacts that we are already dealing with. And likely things will get somewhat worse, but we can prevent the worst impacts from playing out. And that means there has to really be an emphasis on mitigation, because no amount of adaptation is going to allow us to flourish as a civilization in the face of an additional half a degree, one degree Celsius warming of the planet. Dangerous climate change has arrived. If we continue down this road, it will become not just dangerous, but truly catastrophic and disastrous to human civilization. That's one future; that's, that doesn't have to be our future. That's why we need to be so focused on action right now going into this major climate conference later this year, where there's a real opportunity now to act before it's too late.

Michael Mann and Living on Earth Host Steve Curwood in 2019. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

CURWOOD: Over the years, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the science panel, has been criticized because it's tended to underestimate, its projections have not been borne out by the data, that generally we've, we're moving faster in the direction of disrupting the climate. So why has that happened so many times with the IPCC process, in your view? And what do you think will happen with this one?

MANN: I think there are a couple different things going on at the same time. And sometimes we conflate them, but they're distinct. One of them is what my friend and colleague Naomi Orekes of Harvard University describes as "the path of least drama." Scientists just intrinsically, don't want to be out ahead of the data, when they are targets by climate change deniers, and conservative politicians, and right wing media outlets that will go after scientists who make audacious and bold claims, and alert the public to the dangers of continued fossil fuel burning. That's very inconvenient to the fossil fuel interests. And so, you know, as I found out myself when we published the hockey stick more than two decades ago, if you do work and you communicate findings that are a threat to the fossil fuel industry, there's a target on your back. In addition to that is the simple fact that our models are imperfect. Our ice sheet models, we've learned over the last decade or so that there's some important processes that we see playing out in Mother Nature: cracks forming at the surface of the ice sheets, allowing water, meltwater to penetrate to the bottom of the ice and lubricate it so it can slide more quickly into the ocean. Or, the ice shelves disintegrate, and when they do, that inland ice now starts to flow faster. So these are very dynamic processes that we've only really started to really understand and appreciate. And so they weren't in the models a decade or so ago. And now when we put them into the models, lo and behold, we find that the ice sheets can collapse faster, that sea level can rise faster. I think we're seeing something similar with extreme weather events as we start to put more realism into our atmospheric models. And so this isn't in any way sort of a conscious effort on the part of scientists to downplay the impacts. The very act of scientific consensus itself is a conservative process, because you're looking for sort of the lowest common denominator of what a very large number of scientists can all agree upon. And I think we see all of that playing out here. And we should be cognizant of that, because it impacts our ability to assess the risk from what we're hearing.

CURWOOD: Speaking of sea level, by the way, from what you understand from the models that are out there, and maybe some projections of how they might be tweaked. What are we looking at in terms of sea level, say, by 2050 and by 2100, with what we know today?

MANN: Yeah, so let's talk about 2100: three IPCC reports, we were talking about feet, a foot, maybe two feet. Two IPCC reports, we were talking about a meter, three feet. One IPCC report, we're talking about two meters, six to eight feet. Those numbers are trending up, and they're trending up in a disturbing way. And so increasingly, we are coming to the conclusion that large parts of the West Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet could become unstable, given even modest additional warming. And that puts us now in the domain not just of feet or meters, but tens of meters: 10 meters, possibly, by the end of this century.

CURWOOD: You're talking about a 30 foot rise in sea level by 2100, possible?

MANN: Yeah, you're talking about not just New York City having to worry about storm surges with storms like Superstorm Sandy, you're starting to worry about permanent immersion of New York City. You're no longer talking about adaptation, about levees, about dams. You're talking about managed retreat. Moving huge population centers of millions and millions of people away from the coastline, where we're now competing for less and less space, because our coastlines are becoming inundated, major cities have to retreat inward, and larger and larger parts of the tropics are becoming unlivably hot. That's a prescription for all sorts of conflict and national security concerns. It's why some of our leading national security experts have said that climate change constitutes the greatest security threat we face in the years ahead, because all of a sudden now a rising global population is competing for less food and space and water. And so this is a very real concern. And again, in a worst case scenario, we're looking at the potential collapse of civilization as we know it. In the best case scenario, we're looking at a livable planet, for us and for future generations. So let's focus on that scenario, because it's one that's still within our grasp. But it demands that we act now, and that we hold our politicians accountable for acting now, because we can't wait.

CURWOOD: Okay, and so that as much as 10 meter rise in sea level is baked into the system now, or we have a shot by slowing, getting rid of carbon and related type emissions, of never getting to that 10 meter, that 30 foot rise in sea level?

MANN: So, we don't know, with confidence, just how much sea level rise we're committed to at this point, just how much of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheet are likely to go at this point. What is certainly true is if we ramp down our carbon emissions, surface temperatures stabilize pretty quickly, and so we begin the healing. But we may not be able to stop the collapse of large parts of the ice sheets, we may be able to slow that down. And if we can slow that down, even by decades, it gives us far more time to adapt our infrastructure, move our population centers, but we can't rule out 20 or more feet of sea level rise already being baked in at this point. The hope is that if it is baked in, it unfolds over timescales of a century or two, and most of the models indicate that scenario. But as I've said, increasingly, as we put more realism into the models, we find that these things can happen faster than we thought.

CURWOOD: Michael Mann is a Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Sciences at Penn State University. His new book is called The New Climate War. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MANN: Thanks, Steve, always great to be talking with you.

Related links:

- Check out Michael Mann’s book, The New Climate War

- The Guardian | ‘Record-shattering’ heat becoming much more likely, says climate study

- The Guardian | How many years until we must act on climate? Zero, say these climate thinkers

- NPR | How Climate Change Is Responsible For More Extreme Weather Events Worldwide

- Living on Earth's interview with Michael Mann about The New Climate War

[MUSIC: Gary Burton’s “Prelude For Vibes”]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A novel that imagines rewilding the Highlands of Scotland, starting with wolves. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Roy Hargrove “Ev’rybody Wants To Be A Cat” on Disney Jazz Volume I: Everybody Wants To Be A Cat, Walt Disney Records]

Imagining Wolves Returning to Scotland

Once There Were Wolves is a novel about a woman working to reintroduce wolves to the Scottish Highlands. (Photo: Mark Kent, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

[WOLF CALLS SFX]

CURWOOD: Wolves have captured our collective imaginations for thousands of years.

[WOLF CALLS SFX]

CURWOOD: The founding of Rome, for example, starts the legend that two brothers, Romulus and Remus, were raised by wolves. Once common throughout North America and Eurasia, today wolves live on just a fraction of their former territory. And that inspired Charlotte McConaghy, author of the international bestselling novel Migrations, to spin a captivating yarn about a woman working to reintroduce wolves to the Scottish Highlands. The novel is called Once There Were Wolves. Charlotte joins me now from Sydney, Australia. Welcome back to Living on Earth.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much.

CURWOOD: So, the main character of your novel, her name is Inti Flynn, has the task of reintroducing wolves to the Scottish Highlands. And she says, or rather I should say you have her say, that she's always loved wolves without reason. But Charlotte McConaghy, if you had to give a reason, what inspired you to write about wolves?

MCCONAGHY: Well, I didn't know a great deal about wolves before I started this project. My knowledge kind of came from fairy tales as a child, which kind of vilifies them. So I always thought they were magical and beautiful and scary, I suppose. But I started to learn more about them when I first read an article about Pando, the trembling giant, which is the oldest and largest living organism in the world. It's a forest of quaking aspen trees in Utah, which are all connected to the one enormous root system under the ground. And this beautiful kind of ancient thing that's been here, some scientists think it could be almost a million years, is starting to die because of human impact. And at the bottom of this article, it says the perfect solution to saving this organism would be to reintroduce wolves back into the area, because they have incredible power over their environment. But that also, this would never happen because of the local farming and hunting community. And I kind of instantly had this story in my mind, it came to me very quickly in a huge rush, that I wanted to write the story of the woman who was trying to bring these creatures back in order to save a forest, much to the kind of horror of the local community. And so I started to look into wolves and discovered that they're the most extraordinary creatures.

Once There Were Wolves is Charlotte McConaghy’s sophomore novel, following last year’s Migrations (Image Courtesy of Charlotte McConaghy)

CURWOOD: Reintroducing wolves would protect these ancient trees, and they are quite glorious, as you say, these quaking aspens. And you have rather extensive but very accessible ecology lessons in this novel. So just explained to us, to someone who might not say instinctively, why would wolves help protect trees or a whole environment? What's going on there?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, so I think in simple terms, ecosystems need predators, because the predators keep the herbivore populations in check. You know, there's problems all over the world with way too many deer just running rampant, and eating all the little shoots and plants and stopping anything from growing. So when you get wolves back into an environment where they should be, they get the deer moving, which allows the plant life to grow. And it encourages all kinds of other mammals and insects and birds to return to a space. I mean, it changes water tables. They can actually, that's why we say that wolves have the power to change rivers.

CURWOOD: That's just so fascinating. The power to change rivers.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah.

CURWOOD: So you place this in Scotland, which, if I have my history right, I mean, they got rid of wolves in England, and then in Scotland, I don't know, 500 years ago. I mean, they've been gone for a long, long time.

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, that's right. Yeah. Like anywhere in the world. They set out to destroy the creatures they thought were dangerous. But in fact, they're not. I mean, not to humans.

CURWOOD: You say, wait, wolves aren't dangerous to humans?

MCCONAGHY: No, I think I know, I think it's, we all tend to think of them this way. But that was one of the kind of amazing things that I learned during my research is, in fact, they're incredibly shy, family oriented creatures who are terrified of humans, and they will go out of their way to avoid all human contact. The instances of wolves, attacking or killing humans are so minuscule, it's sort of, it's not even really worth talking about. I mean, deer kill more humans.

Wolves' society is matriarchal, with breeding females holding the most power in wolf packs. (Photo: Ralph, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: You mean running in front of their cars?

MCCONAGHY: That's right.

CURWOOD: Yeah, but the Scottish community that you place your story in, is like many others, they're not so inspired by wolves in your book. They're afraid of them. How does the wolf inspire so many and scare others?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, it's interesting. That is one of the things that I kind of found so fascinating was this ability they have to, I guess, conjure these extreme feelings in people. You have both ends of the spectrum. They sort of generate a lot of fear. They also generate a lot of love. And people are very passionate about wolves. And I think maybe it's because they sort of reflect our ideas of the purest sense of wildness in a way. I mean, Barry Lopez, who was an amazing nature writer, wrote that wolves, we've projected onto the wolf the qualities we most despise and fear in ourselves. And I think that's very true. You know, and I sort of wanted to explore that idea in this book. And, and I guess, maybe flip the idea that the wolves are the monsters and kind of say that it's us. We're the monsters.

CURWOOD: Of course your book isn't just about wolves. It's about people, inspiring parts of people. And then the dark side, there's a fair amount of domestic violence in this story. Charlotte, what does this theme mean for your book?

MCCONAGHY: I mean, this was one of the things I was grappling with. Initially, I was feeling very angry about the slaughter of wolves. But I was also feeling very angry at, we've got a domestic violence emergency going on, I know, in my country, and I think all around the world. A woman a week is murdered by her romantic partner in Australia. And that's not including all the women who are not, you know, survive their ongoing abuse. I was writing this novel from a very angry place. And so Inti, in a sense, kind of became the mouthpiece for that fury about the way that humans treat, not just the natural world, but each other as well. She becomes someone who's very kind of acutely aware of the damage that people can do to each other sort of part of the way she comes to see the world. She's lost all faith in people. And the book is kind of about a journey, I suppose from about laying that anger down or finding a way to move on from it, rather than letting it kind of poison you.

CURWOOD: By the way, did that work for you? By dealing with it in such intense and intimate and, frankly, graphic ways? Has it helped you?

Despite appearing threatening, wolves are relatively harmless to humans. In fact death by deer, Charlotte McConaghy says, is far more common than death by wolf. (Photo: Tambako, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

MCCONAGHY: Well, it's still an issue that really, I'm very passionate about. And it's very upsetting still, because we haven't solved this issue. And I don't think this is a book about forgiveness, a lot of things shouldn't be forgiven. And this is one of them. But I suppose, yeah, rising Inti into a place of healing was, it was healing for me as well, in a way.

CURWOOD: Talk to me more about wolves. What is it that you came to really appreciate and understand, and I don't know, if you've got to the point of even revering wolves, some might say that this book certainly holds them way up there. And then what maybe did you discover you didn't like so much?

MCCONAGHY: Okay, um, I think what I was most surprised and fascinated by when I was doing my research was the incredible uniqueness of their personalities. They have extraordinary kind of distinct, mysterious behavior, that is very hard for us to as humans to perceive and understand. In a way, they're sort of really human in their behavior. But in another way, they're kind of really unknowable. And so I think I just fell in love with this uniqueness. You know, each of them have their own kind of lives and adventures and stories and personalities. And, you know, you only just have to follow one to fall in love with it and kind of see that they have this amazing sort of sense of loyalty to each other, courage. I mean, there's a part in the novel, which I kind of took inspiration from a real wolf in Yellowstone, when she loses her mate she howls for him endlessly, which is her method of mourning. And that just felt so kind of, so human in a way, but also so animal. And I think there's something that we can really learn from wolves about the way they love.

CURWOOD: I mean, you right towards the end of your story, there was a quote, when you open your heart to rewilding a landscape, the truth is, you're opening your heart to rewilding yourself, what's happening here?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, I think it's like I've said it's the idea of reconnecting, rebalancing, finding a sense of harmony with wild spaces and places and with the wildness that exists within us, instead of, I guess, separating ourselves to the detriment of everything.

CURWOOD: What do you make of the general understanding now that a wolf pack wolf society is matriarchal, that the alpha alpha wolf is the female wolf, the Mother Superior, whatever you want to call her for the pack? And the strongest male, the alpha male, you know, comes in and out but doesn't run things the way she does?

MCCONAGHY: Yeah, well, I guess it comes down, we call them, they're called now the breeding pair. So instead of the alpha male and female, it's the breeding male and the breeding females. So, and I think that they come to that dominance because they breed rather than because they're sort of more violent or kind of controlling than the other animals, which is sort of fascinating in itself. And I think it really flips that idea of what wolves are on its head and kind of says, Well, no, actually, the thing that they value most or the most powerful part of their society is nurturing and bringing pack into the foreground, raising pups.

Author Charlotte McConaghy lives in Sydney, Australia (Photo: Emma Daniels)

CURWOOD: Scientists who study wolves are careful not to name them. In fact, one of the most famous breeding pairs of wolves are just simply known by their numbers, Wolf 21. And Wolf 42. The Lamar Valley, they're at Yellowstone, the wolves who died not too far apart in time because they were so attached to each other. And almost all of your wolves don't have any names except for one. What, what prompted you to say, well, you know, what the heck I need to name this wolf?

MCCONAGHY: Well, yeah, I was, I found the same thing interesting about scientists not naming their wolves. And it makes sense. I mean, apart from, you know, the need to be scientifically accurate, I think there must also be some element of perhaps not wanting to get too close to these wolves, because what you're seeing as a wolf biologist is the upsetting reality that wolves don't live too long. You know, there's a lot of things that are dangerous for a wolf in the world, and a lot of ways for them to die. And so I think, I mean, at least for my characters, there's a sense that getting too close to them is making themselves too vulnerable to the loss of these wolves. And that's why they don't name them. But there's this one in particular, that Inti becomes quite enamored with. And I think she sees a little bit of herself in this wolf in some ways. And that's why I think even against her better judgment, and against her will, she starts thinking of this wolf with a name. And I think that was just my way to, I guess, indicate that Inti was getting too close. We're getting closer, than she knows she should.

CURWOOD: To what extent do you think wolves might actually be brought to the Scottish Highlands after all these centuries? I mean, the way you write this makes it sound like it just could happen the way it is in this book. Tell me more about that. How likely is that to happen?

MCCONAGHY: Oh, I would like to say it's more likely than it is. It's a big topic for discussion over there. It's a big debate that's going on, conservationists can see the benefits and the impact that it would have on the environment. And you know, Scotland is a very progressive country in terms of its rewilding efforts. So it's I don't think it's impossible. But there's also a very big pushback against it from the farming population, because it's very densely farmed. And there's a lot less land, you know, than there is in America, for example,

CURWOOD: It wasn't exactly easy to get wolves reintroduced in the lower 48, here. There was huge pushback in that effort. And yet, I guess today, it's safe to say that it's going reasonably well. Why do you think it worked in Yellowstone?

MCCONAGHY: I think it worked because wolves are meant to be there. They used to be there and they should have never left. Essentially, it worked because nature intended it.

CURWOOD: Charlotte McConaghy is the author of the novel Once There Were Wolves. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today.

MCCONAGHY: Thank you so much for having me back. It was lovely to chat.

Related links:

- More on the book, Once There Were Wolves (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Living on Earth’s interview with Charlotte McConaghy about her last book, Migrations

- Find other books featured on Living on Earth (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

[MUSIC: Paul Winter Consort, “Wolf Eyes” on Silver Solstice, by David Darling/Timber Wolf/Paul Winter, Living Music]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Bobby Bascomb, Paloma Beltran, Anna Canny, Jenni Doering, Jay Feinstein, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Joshua Siracusa, Tivara Tanudjaja and Jolanda Omari. Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth