November 26, 2021

Air Date: November 26, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Plant and Planet-Centered Eating

View the page for this story

Our global food system feeds environmental crises like global warming and water pollution even as it fails to adequately feed billions of people worldwide. So in the 50th anniversary edition of “Diet for a Small Planet,” author Frances Moore Lappé renews her calls for a plant- and planet-centered food revolution. As Americans gathered to give thanks over a feast, Ms. Lappé joined Host Steve Curwood to discuss how embracing the plant world in our diets connects to climate, health, and democracy. (11:13)

LOE Gives Thanks

View the page for this story

To celebrate Thanksgiving, the cast and crew of Living on Earth shares some of the things in life that we’re truly grateful for. (03:15)

Celebrating the "Seven Sisters" Native Crops

View the page for this story

In some Native cultures four more crops join the “Three Sisters” of corn, beans, and squash. Host Bobby Bascomb talks with Amyrose Foll, the founder of the Virginia Free Farm and member of the Abenaki tribe, about the Native American tradition of the Seven Sisters crops and the importance of saving Native seeds. (08:48)

The Season for Sunchokes

/ Bobby Bascomb & Steve CurwoodView the page for this story

Hosts Steve Curwood and Bobby Bascomb meet up in Bobby’s garden to harvest sunchokes, one of the foods that make up the "Seven Sisters" of Abenaki traditional agriculture. Then, the two discuss some recipes that use the tasty tubers, and roast a few to make some sunchoke chips. (07:45)

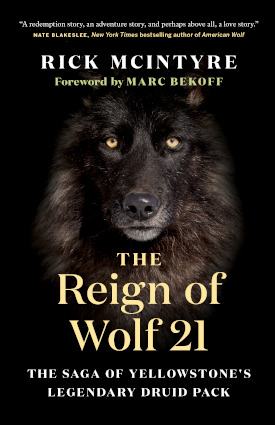

The Reign of Wolf 21

/ Jenni DoeringView the page for this story

Wolf expert Rick McIntyre’s 2020 book "The Reign of Wolf 21" is the true love story of an alpha pair who lead their Yellowstone pack with grace, courage, and an unbreakable bond. Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering has the story of these remarkable wolves’ lives and what they can teach us about love, loyalty, and leadership. (16:46)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

211126 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Amyrose Foll, Frances Moore Lappé, Rick McIntyre

REPORTERS: Jenni Doering

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

The 7 sisters of Native American agriculture and the importance of saving their seeds.

FOLL: The seed is power when you think about it and distill it to its most basic idea. If you control your food source you're a lot harder to manipulate and influence when you're healthy and well fed and your mind is clear.

CURWOOD: Also, the remarkable life and love of a wolf and his mate who led one of the most powerful packs in Yellowstone.

MCINTYRE: He was, um… I think many people would agree that he was probably the greatest wolf that has ever been known by a human being. So just to be able to see him every day for year after year was just a huge privilege on my part.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Plant and Planet-Centered Eating

Amber waves of grain (Photo: Andrew Gustar, Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

BASCOMB: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. This is Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

When American families gather to give thanks, many of the foods on our tables don’t express gratitude to the Earth, as much of our present food system is polluting and wasteful. For starters about a third is thrown away, tossed from kitchens and plates in rich places and spoiled where people can’t afford to refrigerate. And many industrial growing systems pollute and waste as well, using too much water, land and chemicals in ways that also add to climate disaster. Yet around the world more than 2 billion people are food insecure. Fifty years ago Frances Moore Lappé wrote the bestselling “Diet for a Small Planet” in a bid to address the hunger crisis, and along the way she seeded a plant-centered food revolution in the kitchens of America. Now there’s a new anniversary edition of her book in which Frances Moore Lappé writes how pathways to sustainable food and democracy also lead to a healthier planet. She joins me now from Belmont, Massachusetts. Welcome back to Living on Earth, Frankie!

MOORE: Thank you so much, Steve, delighted.

CURWOOD: Frankie, just to be clear, what is a plant centered diet?

According to the UN's Food and Agricultural Organization, the meat and dairy industry contributes to about 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Alex Promios, Flickr, CC BY NC 2.0)

MOORE: Well, it's embracing the plant world. When I moved from meat, you know I grew up in Texas cow town, right. So people said oh you're giving up so much and I said, no, no, no, it's the plant world that has all the taste differences, the color, the shapes, the textures, you know, it's where all the yummy stuff is. And so for me being plant centered is I don't follow recipes a lot but going into the kitchen and looking, you know, seeing what's there and finding out spices and herbs I love and for example, I turned a basic beans and rice dish into an Italian dish by just changing the herbs that are used in it. It's called Roman Rice and Beans in Diet for a Small Planet.

CURWOOD: So what you add a bit of oregano, and some thyme to make a more of an italiano type of rice and beans, huh?

MOORE: Yeah, probably there's basil in there, too. But you got the idea? Yeah.

CURWOOD: Okay, some basil, all right. So what's changed in the last 50 years since you wrote Diet for a Small Planet?

MOORE: Well, one thing for sure that what I thought was a good choice of way back when is now an absolute necessity to save life on our planet. So, yeah, that's a huge change. And I'd like to say that we're sort of moving in two directions at once because we've got it now we know what to do and all over the world, people are aligning with nature to grow our food but still the dominant extractive approach that is so dangerous and so unnecessary is still going strong. So we really are moving in two directions at once.

CURWOOD: So Frankie, what's the climate cost of the way we produce and consume food today?

Francis Moore Lappé has been a longtime advocate for helping communities regain democratic control over the food system, enabling its sustainable transformation. (Photo: Christopher Chan, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MOORE: Well, our food system globally contributes about 37% of greenhouse gas emissions and about 40% of that is from the livestock sector. So that's a huge contribution. And now I'm calling it a plant and planet centered diet because if we really addressed this crisis and grew a healthy plant centered diet, that would cut the agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by about two thirds. A professor at the University of Minnesota calculated that it would be the equivalent to removing basically all the vehicles off the planet.

CURWOOD: Now, people listening to us need to be reassured that you're, you're not saying you can never eat meat, you're just telling us that make it a rare occasion.

MOORE: Yes, and to recognize especially in this country because we are one of the largest meat consumers, so what we do makes a huge difference. I mean, that's one thing about being especially on the wrong path, it means that if we turn that has an outsized impact for the good. So I call myself plant centered eating and I haven't eaten a hamburger since 50 years ago but I'm not I'm not a vegan. On a daily basis I don't eat a lot of dairy but Steve, I have to admit the half and half in my coffee. [LAUGH] You know, I really want to be big tent and to welcome people if they are eager to align with their body because there's a lot of evidence that this plant centered stuff is really good for us and with the earth thriving. So I think any step we can take I celebrate.

According to reports by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation a poor diet with heavy red meat intake and sugary beverages is one of the greatest contributors to early death worldwide. (Photo: 1flatworld, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

CURWOOD: Now, the meat production industry has gone to great lengths to concentrate operations. They say it cuts costs and improves efficiency but I think from purely a biological standpoint, no matter how efficient the meat industry might say that it has become, it could never be plant based diets in terms of the resources required to produce the calories and nutrients that people need. Why is that? And how do they compare?

MOORE: This is what woke me up at age 26, that I saw meat production as a protein factory in reverse. Consider this, we use about 80% of our agricultural land to produce livestock but they get to us only 18% of our calories. So right there that is pretty darn inefficient and for beef, one estimate says that of the grains fed to livestock we get about 3 to 5% of the calories and protein that we eat from all of that grain that gets fed to livestock in this country. So it's really hard to imagine anything less efficient. That is for beef, everything gets a little more efficient as you go and especially poultry are significantly more efficient. So beef is the worst and unfortunately we still eat a lot of beef. And I also want to add here, that it's not only the environmental costs, but definitely the human health costs.

CURWOOD: Well, tell me a little bit more about the the health risk of red meat.

MOORE: Well, I was actually shocked to learn recently that the WHO, the World Health Organization has deemed red meat a probable carcinogen. And when I looked into it a bit that has to do with heme iron in red meat and that could be a facilitator in some way of a process of disease and that high temp cooking, high temperature cooking could be a factor in making it not good for us. That is a red flag for me that the WHO has given us and then on processed meat the WHO has deemed processed meat a carcinogen. So that would include salami and hotdogs and all of those, and we eat a lot of it, about 20% of our meat is in that processed form. They add that it's on the level of tobacco, alcohol, that sort of thing. So it's not a small concern.

CURWOOD: Oh, boy. So food is clearly linked to ecological health and our own, of course. But why do you think that the food we eat is also linked to the health of our democracy in your view?

According to the nonprofit organization ReFed, food waste has a footprint equivalent to 4% of total US greenhouse gas emissions. (Photo: Carribb, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MOORE: Well, everything is linked with the health of our democracy, Steve. You know I think of our democracy as the taproot crisis and we also have a living planet crisis and we also have an economic crisis to have concentration of wealth, but the taproot is democracy, because that is the way that we make decisions together to solve problems. So if we're going to solve the problem of hunger, amid plenty of our diet being so hazardous to our health, which is so ironic and sad, if we're going to solve these huge problems of our environment, and the impact of farming on climate change, which is quite significant, we have to have democracy. And what we have now I think of as a very corrupted form because private interests those who are benefiting very much from fossil fuels and from the meat production industry and all that we have in place now they have tremendous power in Washington. There are now 20 corporate lobbyists in Washington for every single person that you and I elect to represent us in Washington. That is problematic, that is what I call a corrupted system and that's why I think it's so important Steve, we've got to solve these problems and we've got to have democracy to solve them.

CURWOOD: Frankie, you write about a worldwide revolution in agro ecology, that Jules Pretty at the University of Essex in the UK and colleagues have documented. What's the significance of this bottom up revolution in how people are growing food? And what do you think that might mean for democracy?

MOORE: Well, I think it is a form of what I call living democracy because it's an everyday practice of working together, making decisions together on the land, what we grow, how we grow it. And one of the most exciting things in writing the 50th anniversary opening chapter was really being in touch with Dr. Pretty who you mentioned because he's devoted his life to tracking the emergence of such forms of self governance on the land, growing food healthfully, and he was able to track from the year 2000 to 2020, this enormous change. When we started in 2000, there were about half a million of such groups around the world and during those 20 years, 8 million more such groups, he was able to identify.

CURWOOD: The fault lines in our democracy and the problems with our food systems seem bigger than ever these days. Yet in order to fix them, people have to believe that things can change that in fact, we can make a difference. So what's your advice for practicing hope without well, you know, singing the songs of Pollyanna?

Frances Moore Lappé is author of Diet for a Small Planet. She founded The Small Planet Institute, which focuses on social solutions to the environment, hunger and politics through living democracy. (Photo: Michael Piazza)

MOORE: Well, I have decided that I am not an optimist Steve, because I think optimism means that you have some certainty of outcome. And I think a lot of human beings we don't need certainty of outcome. All we need is the sense that it is possible that our actions can matter and we humans will jump inn because we want to matter that's part of our essence, we want to count. And that's why I think starting with food is so beautiful because every day we make choices of what we put into our mouth. That connects us to the people who grow the food are they being poisoned by pesticides? Well if we're eating their food that keeps that going on and on to the climate impact and so I really think that this theme of optimism is not the way to go. I call myself a possiblilist not an optimist because I believe that there is still a chance that our actions can make a huge difference in turning our planet toward life.

CURWOOD: Francis Moore Lappé is a co-founder of the Small Planet Institute and has authored 20 books including Diet for a Small Planet. Thanks so much for taking the time with us today Frankie.

MOORE: Thank you so much, Steve what a pleasure.

Related links:

- The New York Times “The Godmother of Plant Based Living”

- Learn more about Frances Moore Lappé

- Find the 50th anniversary edition of "Diet for a Small Planet" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn more about the WHO's finding that processed meat is carcinogenic and red meat is probably carcinogenic

[MUSIC: Cyrus Chestnut, “Blessed Assurance” on Spirit, by Cyrus Chestnut, Jazz Legacy Productions]

LOE Gives Thanks

The LOE staff wishes all our listeners a happy Thanksgiving season! (Credit: Priscilla Du Preez, Unsplash)

BASCOMB: So, Steve, you know one of my favorite things about Thanksgiving, other than the pumpkin pie, is the tradition of going around the table and everyone says what they are thankful for.

CURWOOD: Oh, me too. It’s such a great time to reflect on our blessings, really. So, Bobby, what are you thankful for this year?

BASCOMB: So many things, I mean my health, my family but I’ve really been thinking a lot lately about how grateful I am for the things I get to grow, both my children and my garden. How about you Steve?

CURWOOD: First of all, let me speak right to the microphone: I’m thankful for you our listeners, since you help make it possible to keep telling the story of Living on Earth. And I am grateful for my family and health too, and the possibility enough of us will wake up and stop the planetary stampede toward the cliff of climate disaster in time to save us all.

BASCOMB: Nice! I couldn’t agree more! So, we also asked our crew here at the show what they’re grateful for, and here they are.

[MUSIC: Bill Evans Trio, “Autumn Leaves – Album Version – (Take 1)” on Portrait In Jazz, Fantasy, Inc.]

DOERING: I'm producer Jenni Doering and I am thankful for the highlight of this year, which was finally being able to safely hug my sister and my parents for the first time in so many months.

KAUSCH: I'm Mark Kausch when I'm not working on programming strategy for Living on Earth, I teach young people how to play the string bass and I'm thankful for my students, their wit, their passion, their energy. They remind me of how great life can be when we all find ways to deeply connect with each other.

SANTILLI: I'm Genevieve Santilli, I'm an intern here at Living on Earth, and I'm thankful for my healthy friends and family.

BELTRAN: I'm Paloma Beltran an associate producer here at Living on Earth, and I'm thankful for my beautiful baby nephew, Emilio, and for his parents who managed to fill his days with boundless love and care. Thanks for making me the cool auntie.

REGO: I'm Jake Rego, technical director at Living on Earth. This year, I am thankful for all of my friends and family, their good health, and all of their help with renovating my new home.

URTON: I'm Gabriell Urton, an intern for Living on Earth. I'm thankful for having the opportunity to go to college. And I'm also thankful for finally graduating in December.

SETH LENDER: I'm Mark Seth Lender explorer in residence. Where I live on Long Island Sound, we've had hundreds of thousands of menhaden passing through. And because of them, we now have a breeding pair of bald eagles. I'm thankful for the fish, and the people who work for their conservation.

O'NEILL: My name is Aynsley O'Neill, I'm a producer with Living on Earth. I'm thankful for the technology that allows me to see my family virtually over the pandemic, even when we're really far apart.

SHI: I'm Teresa who's an intern here and this year I'm thankful to my girlfriend, Marissa who helped me to connect with nature, and myself again. And for all the walks we took together.

DYKSTRA: This is Peter Dykstra. For the past six years, I've recorded the Beyond the Headlines segment. And I'm grateful for public radio and particularly for Living on Earth for covering heavier news like fossil fuels with my fellow fossil Steve Curwood, more than 30 years of quality coverage on the environment.

CURWOOD: Peter always has a joke, doesn’t he Bobby?

BOBBY: Oh he does. After the break Steve, you’re going to come to my house and dig up a native food that few people have probably heard of.

CURWOOD: That’s right, sunchokes! Or should I say Jerusalem Artichokes? Anyway, Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you!

That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chet Baker “Autumn Leaves” on Jazz Moods – Cool, Sony BMG Music Entertainment]

Celebrating the "Seven Sisters" Native Crops

Sunflowers, also known as Gizos kogan in Abenaki, is just one of the Seven Sisters crops. (Photo: fionaandneil, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

CURWOOD: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb

So, Steve last week you had a story about the 3 sisters that are traditionally part of many Native American gardens.

CURWOOD: That’s right corn, beans and squash. They are grown together for their mutual benefit and can make for a variety of tasty stews.

BASCOMB: Yes, I have to try some! But I learned recently that there are actually seven sisters in some native food cultures. You know me, I’m pretty big gardener and I wanted to learn more so I called up Amyrose Foll. She is Penobscot Abenaki and founder of the Virginia Free Farm in Virginia. Their mission is to provide free native seeds to gardeners and training for how to grow them. Hi there Amyrose!

FOLL: Hi, thank you for having me.

BASCOMB: So, some of our listeners may be familiar with the Native American tradition of the Three Sisters, that is planting corn, beans, and squash in the same plot of land to mutually benefit each of the plants. But you say that they're actually seven sisters in some native food traditions. What are they?

FOLL: Yeah, so we're so different across the continent. I mean, there's 600 different tribes. And so, we have a base of seven sisters that's skamon, which is corn, adebakwal, which is beans wassawa, which is squash, gizos kogan, which is sunflower Jerusalem artichokes, which actually don't even have a word. We call them Ojibwe potatoes. The Ojibwe are far west the Anishinaabe. They're west on the other side of the Mohawk. And sister ground cherry, which is kiiadebimen and odamo or wodam, which is tobacco.

BASCOMB: Our listeners are probably familiar with some of those, you know, like sunflowers and corn, and beans, but maybe haven't heard of ground cherries. They're sort of like a tomatillo, a little fruit inside of a papery husk. I think they taste like a cross between a tomato and a pineapple, but in the most delicious way you can imagine. Can you tell our listeners more about those?

FOLL: Yes, they do have this kind of amorphous taste. I don't know some people describe it as tomato crossed with strawberry. Some people describe it just as you said tomato crossed with pineapple. I love them. They're so good. You can use them pretty adaptively, for sweet and savory applications and cooking. They're so good. They're really great to add to hot sauce.

Squash, known as wassawa to the Abenaki people, is another one of the Seven Sisters and is quite common on a lot of Thanksgiving plates. (Photo: John Cudworth, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: Well, you know, most of our listeners are going to be familiar with corn, of course, I mean we think of sweet corn that we get in the summertime, corn on the cob. But there are actually 1000s of varieties, from what I understand. Can you please tell us about one or two of your favorites, and why is corn so important in your native culture?

FOLL: So corn, it's I mean, it's so adaptable, there's so many different kinds. So we have calais and Tom Thumb, and we've got gaspe, and then there's other corns that are quick maturing as well. And when you think of like hemo white, it's adapted specifically to not really need to be watered. And then the rest of the country have longer ears, sometimes different colors, different sugar contents, for particular things, you can make parched corn, which I think your listeners probably would be more familiar with corn nuts that you can get at every convenience store across the country. They're actually a traditional Native food and they're parched for longevity. But then there is all sorts of different corns that you can make flour out of, popcorns, and they were basically specifically engineered naturally by farming mothers of the past many generations back. And they're kind of like a little gift to us today, especially that any of some of these varieties are very scarce.

BASCOMB: It's really a reminder to me of just how much diversity, how much richness there is in food and how much we've lost by not, you know, growing these things and having access to them, and, you know, by proxy, maybe losing a bit of our culture.

FOLL: Yeah, and it's sad, because when you think about native foods, really what do you think of besides corn? Probably not much. And it's surprising to really think about because 75% of the food that's in an average Americans diet on a day to day basis, or actually New World cultivars or crops. I mean, green beans that everyone has for Thanksgiving, they are native cultivars, there is no green beans, lima beans. They are native to the new world.

BASCOMB: Now, why do you suppose it's called the Seven Sisters? And not the seven brothers or the seven cousins? Why do these plants have a femininity associated with them?

FOLL: Well, there's actually two answers to that question. So they do take care of you. In the springtime, there's a saying the earth is pregnant, so we must tread lightly. And then as it progresses into summer, and things are more vigorous, the garden matures, and then in the fall when the garden is ready to be harvested, it's like a grandmother that cares for you and nourishes you and provides everything you need from the seeds for next year to the sustenance that your body needs in the present time and in the moment. And also farming was traditionally done by women, the women were in charge of making sure that all of the food was grown properly harvested and distributed throughout the families.

BASCOMB: Now a big part of your work is to advocate for saving seeds as a way to preserve native cultures. Can you tell us more about that, please? What is that relationship?

Corn is one of the most common and one of the most important crops for many Native American tribes. (Photo: lancehayden, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

FOLL: The seed is power when you think about it and distill it to the most basic idea. If you control your food source, you're a lot harder to manipulate and influence when you're healthy and well fed and your mind is clear. And you know, food was actually used as a means of extermination and a weapon of war against my ancestors. And it was fairly effective. But food was used as a manipulator and a means by which to control people. So when I advocate for seed sovereignty and food sovereignty, not just for Native people, but for all people in my community, because if we work together, and we have a method to control our food source, because nobody can argue with the fact that a lot of the American offerings of food are not healthy, that we have on a regular basis, and that might be purposeful the food system was built the way it is for a reason. But if you can provide your own food and take care of yourself, you are less controllable, you're sovereign, you can feed yourself, you don't need anyone else to provide it for you. And that's important.

BASCOMB: And if we don't keep these native seeds, these rare seeds and grow them out as plants, how real is the possibility that some of these varieties could actually go extinct?

FOLL: Very real. Last year, I believe it was one of only two growers in North America for Abenaki rose corn, and this year, I think I was the only US grower of Penobscot pumpkins. A lot of these are so scarce that even if you Google them, you'll be hard pressed to find much information on them. One of the ones that I grew this year was Winnebago corn. It's Winnebago spotted corn, and it's so scarce, even tiny boutique seed companies don't offer that in their catalogs.

BASCOMB: You know, the country seems so divided right now in so many different ways. But you know, Thanksgiving and this, this season of the harvest always feels like a time that people can come together. Everybody can agree on food, right? Everybody can agree what's good, what tastes good, you know? How do you see these native seeds and native plants as a potential way of unifying people? If at all?

FOLL: Yeah, food culture is the great unifier. It bridges cultural gaps, I guess you could say. I mean, okay, so when I think of culture, I always think of food. I think of Italian food, or Thai food or Ethiopian food. And I think food can be a great unifier, especially when you're trying something new. I mean, when you're sitting around your Thanksgiving table, you're basically eating the continent. The green bean casserole, the turkey, the potatoes, the pumpkin pie. And it's funny, because not a lot of that is seen as native food anymore. It's just kind of generic American food. And when you think about Thanksgiving in particular, it was a manufactured holiday after the Civil War to bring two sides of a divided country together. So I think that there's a lesson to be learned from that, you know, and if we can just set our differences aside and sit down around a good meal and enjoy it and savor it. There's huge power in sharing food with someone. I mean, the first thing I do and everybody when it comes over, especially if they're new guests, or I haven't met them before, or they're brought by a friend of mine over is trying to feed them. Maybe I'm turning into my grandmother, but I think that's great. It disarms you. It makes you feel welcome and comfortable. I think that that's a beautiful thing.

BASCOMB: I do too. I think you know, the way to anyone's heart really can be through food. Amyrose Foll is founder of the Virginia Free Farm in Kents Store, Virginia. Amyrose, thank you so much for sharing these stories about food with us today.

FOLL: Wliwni, thank you for having me.

Related links:

- Learn more about the Virginia Free Farm

- Learn more about the Seven Sisters crops

The Season for Sunchokes

A basket of sunchokes harvested from Bobby Bascomb’s garden. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

[STREET SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: So It’s a beautiful fall day today here in NH, and I’m waiting for Steve to arrive any minute now to help me dig up some sunchokes.

CURWOOD: Hey Bobby,

BASCOMB: Hey Steve! How’s it going?

CURWOOD: such a wonderful fall day,

BASCOMB: Oh my gosh, we really lucked out with this weather, it’s so beautiful today.

CURWOOD: So here we are in the harvest season. In your garden, Bobby.

BASCOMB: Yes, yeah, you know me you know I'm a pretty big gardener and we just heard this story from Amyrose Foll about the seven sisters and I have to say I never knew there were seven sisters I grow the three sisters corn, beans and squash but then I read this article she wrote and I realized I actually grow six out of the seven. I don't grow tobacco, it never occurred to me to do so. But this is actually right now the season to dig up sunchokes everything else My garden is dead or dying looking pretty sad. But right now is the season for sunchokes.

CURWOOD: Alright, well I’ll grab one of these shovels.

BASCOMB: Yeah, maybe I'll grab a pitchfork. You grab a shovel, we'll see what works best.

BASCOMB: So it's just right here in front of us. And you would probably have no idea that there's food growing in this patch of dead looking dried up weeds but…

CURWOOD: Yeah. As a matter of fact, it don't look like much of nothing going on here.

BASCOMB: It doesn't. But had you been here like end of September beginning of October. That's when sunchokes are blooming. And it's great because it's just when all of the other blooming flowers are done, that sunchokes come out. And they're this beautiful yellow flower and they're in the sunflower family. And they're a wonderful late season food for pollinators. You know, I've seen them covered in bees and even some straggling butterflies that are still hanging around. Love the sunchokes.

CURWOOD: Yeah, these guys are really tall.

BASCOMB: Yeah, they must be what, eight feet tall or so.

CURWOOD: Yeah, those are big. And there's Oh, I see the remnant of the flower on the top there. Yeah, it's all kind of dark and shriveled. And the leaves are shriveled.

BASCOMB: Yeah, they don't look like much right now. But this is actually the time to harvest them. I was thinking maybe we could start along the edges. Because the other thing about sunchokes is that they just spread and they'll take over this whole little field Here I have some horseradish growing. So I’d sort of like to, you know, maybe get on that side of it.

CURWOOD: Alright, so we'll come on the other side of the horseradish. Okay.

[DIGGING SFX]

CURWOOD: oh, your soil is so dark and rich Bobby.

BASCOMB: Yeah, it's good stuff.

[DIGGING SFX]

CURWOOD: wow look at these Bobby you grew some big ones. Hmm.

BASCOMB: Steve, I did so little to grow these but yeah, they do look good. They're white sort of like a potato but with all these little funky knobs all over them.

CURWOOD: So what do they want? Where do they need to be in the bright sun?

Steve Curwood holding up a clump of sunchokes. (Photo: Bobby Bascomb)

BASCOMB: Yeah, they like sun not too wet. And honestly, if you leave any one or two behind, they'll just take off the next year. So growing sunchokes is sort of a commitment. You're almost never really going to be rid of them. Which is okay, I like them.

CURWOOD: And this comes from the Native American tradition, people grew this in North America long before people came from Europe and Africa here.

BASCOMB: Yeah, yeah, it's very, very much a Native American food. And Amy Rose Foll told us it was one of the Seven Sisters one of the most important foods that that the Native Americans grew really important part of their food culture.

CURWOOD: Well, I can see why especially in terms of timing, here it is November, and you're getting a nice harvest.

BASCOMB: Yeah, exactly. And honestly, you can harvest these pretty much year round. I mean, once the ground is frozen, it would be a pretty arduous task, but you could

All right. Well, should we go cook up some sunchokes?

CURWOOD: Yeah, let's do that

[WALKING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: All right. So we're in the kitchen. Make some room here. I already popped the oven on. So it's preheating for us. And first thing we need to do obviously is wash them they're pretty dirty.

CURWOOD: They’re covered in a bit of dirt.

[WATER RUNNING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: So, I think part of the reason that maybe they're not so popular as a food anymore is that they do have a reputation as sort of giving you some intestinal problems, sort of like beans. But if you don’t overdo it, if you just have a few it should be ok. Also, they're not like potatoes in that they don’t last very long. Just less than a week of so in the fridge and they’ll start to shrivel up on you.

[WATER RUNNING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: OK, wash these. Put the clean ones in the bowl. That should be good enough to start, huh?

CURWOOD: Alright

BASCOMB: We can slice some up, olive oil salt sort of chip style.

CURWOOD: Yeah, sounds pretty good.

[CHOPPING SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: Alright, so we patted them dry we cleaned them we'll put some olive oil, salt and pepper and then in the oven.

[GRINDING SOUNDS]

CURWOOD: Alright.

[ OVEN SOUNDS]

BASCOMB: So this is set at about 375 I guess it might take 15 minutes or maybe something like that.

CURWOOD: These are better for you than than potatoes, right?

Bobby Bascomb shows off sunchokes grown in her garden. (Photo: Steve Curwood)

BASCOMB: Oh my gosh, yeah, so they're really good for you. They they are really high in iron. One little sunchoke has as much iron as three ounces of red meat. And they're supposed to be really good at stabilizing blood sugar. So for diabetics, this would be a superfood I think they're also high in protein all sorts of nutrients they're really really good for you.

BASCOMB: So I think these are about done, Steve let's check it out.

BASCOMB: So these you just want to cook them until they're pretty soft. All right. Let me grab a special and a couple forks and plates

CURWOOD: Okay. Okay, here we go.

BASCOMB: Buen provecho.

CURWOOD: Alright, you're the cook. You tell me what you think.

BASCOMB: Okay. It’s really hot. They’re so good. They're so good. They're such an underrated food. Really. They're like, kind of sweet. Not in a sweet potato sweet way, but just kind of sweet, nutty. They're just really delicious, in my opinion, but this is your first time so you you give me your honest assessment.

CURWOOD: Okay, mmm… A little towards the parsnip end of things.

BASCOMB: The texture is a little parsnipy, I could see that. They're not. I don't know. What's the word powdery like a potato.

BASCOMB: Some of the edges have a little bit of crunch to them. The middle is super super soft. And the edges just a tiny bit crunchy.

CURWOOD: What I bet these would be great in a soup.

BASCOMB: Yeah, yeah, I think you could probably treat them anyway you treat any root vegetable in a soup and a stew. You could pan and fry them if you slice them, you know pretty small. You can shred them. You can eat them raw. You know, what what can’t a sunchoke do they are just the gifts that keep on giving. You can harvest them all year. They're super easy to grow.

CURWOOD: I know I've learned something today, Bobby. Thank you.

BASCOMB: Oh, thanks for coming. I'm glad you like them. And Steve, you're going to take some home right? Because we have about 20 pounds of sunchokes over here.

CURWOOD: Okay. Yeah, but I have to cook them up in the next couple of days.

BASCOMB: You do.

CURWOOD: But they're really good.

BASCOMB: Yeah.

CURWOOD: I’m going to have another bite here. Well there’s another piece here, I don’t think I should let it go to waste.

BACOMB: No, no certainly not.

Related links:

- Vermont Community Garden Network | “The Seven Sisters of Abenaki Indigenous Agriculture”

- Learn more about sunchokes from Lakewinds Food Co-Op

[MUSIC: Wilsen “Garden” on I Go Missing in My Sleep, Secret City Records Inc.]

CURWOOD: Coming up –life and love in the Druid wolf pack of Yellowstone National Park. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Network Music Ensemble, “We Gather Together” on Jazz Hymns, by Adriaen Valerius/Eduard Kremser, Network Music]

The Reign of Wolf 21

Wolf 21 and Wolf 42 on their last day together. They were nearly nine years old, twice the average life-span of Yellowstone wolves. (Photo: Kim Kaiser)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood

One of the most endearing aspects of dogs as pets is they can respond to each other and us humans with what seems to be unconditional love. So we really shouldn’t be surprised by a love story about two wolves, given that wolves and dogs have almost identical DNA. Living on Earth producer Jenni Doering learned the wolf love story you are about to hear from Rick McIntyre who logged more than 100,000 wolf sightings in Yellowstone National Park as a biological technician with the Yellowstone Wolf Project. Rick’s longest continuous streak of watching the wolves started in June of the year 2000 and was an amazing six thousand, one hundred and seventy-five days. Wolves are most active at dusk and dawn, so Rick had lot of early mornings and late nights. And cold, sometimes the temperature got as low as 33 below! Rick McIntyre is retired now but he still gets out into the field almost every morning to watch the wolves, before coming home to write about them. He’s written three books about the Yellowstone wolves and spoke with Jenni about his 2020 book “The Reign of Wolf 21.” It’s the heartfelt account of 21 and his mate 42, and the Druid wolf pack they led for a decade in Yellowstone National Park.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: When Rick McIntyre is out tracking wolves, he peers down a powerful spotting scope to see them as far as a mile away. And shares the view with visitors.

MCINTYRE: A lot of folks visit Yellowstone; they all want to see wolves, so folks like myself, we get to help people have an experience with that. I’ve shown famous people wolves, movie stars; politicians; I’ve shown regular people, I’ve shown schoolkids…

DOERING: And he does a lot of his wolf watching in the Lamar Valley as its wide, flat meadows attract large herds of elk, pronghorn, and bison.

The Reign of Wolf 21 is part of Rick McIntyre’s “Alpha Wolves of Yellowstone” series. (Image: courtesy of Greystone Books)

[SOUNDS OF BISON GRAZING IN LAMAR VALLEY]

DOERING: Several creeks feed the Lamar River braiding its way beneath the snow-capped Absarokas. It’s a big, open landscape where humans can feel like there’s so much beyond us.

MCINTYRE: I think we understand now that we’re just part of a very big world and many other species are out there, including primates, and wolves, dolphins, whales, etc that have emotions and intelligence that are very very similar to us. Anyone that watches wolves in the wild, there’s just no way around it that they have very strong emotional aspects of their lives; they’re rational thinkers; they make decisions, whether good or bad.

DOERING: And they’re highly social animals who live together in packs of five to ten members. And Rick says packs can briefly grow to 30 or more members before some strike out on their own, living life as a lone wolf before finding another home.

[WOLF CALLS]

DOERING: And he told me he had to write a book about the alpha male that researchers called Wolf 21.

MCINTYRE: Well, there’s so much to say about him, it's almost like if Superman was a real person, how could you describe him?

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: This hero had mostly grey fur, with a cape of black along his back. He not only survived in the harsh Yellowstone climate… As the alpha male of the powerful Druid Peak Pack, Wolf 21 thrived.

MCINTYRE: So from his biological father who he never knew, 21 was gifted with extremely superior genetics. So he grew up into a very large, a very strong wolf.

DOERING: Which matters a lot when it’s your responsibility to bring down elk and even bison. And to protect your family from rival packs. The Yellowstone ecosystem supports about 8 to 10 packs with names like Leopold, Chief Joseph and Mollie’s, which each patrol their own territory. They often overlap, and conflicts are common. In fact, wolves in Yellowstone are most likely to die from wounds inflicted by other wolves. But Wolf 21 didn’t have to worry too much about that.

Rick McIntyre with his powerful spotting scope, which he uses to help him see wolves as far as a mile away. (Photo: Julie Argyle)

MCINTYRE: As far as we know, he never lost a fight in his life, including times where he had to fight several other males at the same time, so he was the undisputed undefeated heavyweight champion of Yellowstone.

DOERING: And, despite the fact that wolf fights can be brutal…

MCINTYRE: He never killed a defeated opponent.

DOERING: He’d beat up rival wolves, sure. Fearlessly defend his kin. He let rival packs know whose land they were on, the mighty Druids. But then he’d step back and let them go.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

MCINTYRE: He was, um… I think many people would agree that he was probably the greatest wolf that has ever been known by a human being, so just to be able to see him every day for year after year was just a huge privilege on my part. I saw him deal with all sorts of problems and crises, and he just had this very smooth way of mainly using nonviolence when he could, or minimum violence and force when necessary. Oftentimes I would compare him to people who had very special dogs in their life, that were so loyal and devoted and had such good characters, and I think you know that all modern dogs in the world come directly from wolf ancestors, so everything we admire in our pet dogs, their courage, their bravery, their loyalty, their devotion, their playfulness, all that, that comes exactly from ancestors like Wolf 21.

Wolf 21 confronts a grizzly bear eyeing an elk the alpha wolf had just killed. (Photo: Betsy Downey)

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: Alongside the alpha female, he led one of the largest packs in Yellowstone history, with 37 wolves at its height. The Druid Pack drew the fervent attention of the wolf watching public. They’d flock in the hundreds to the Lamar Valley where they reigned. Rick would help them find the pack, and if they were lucky and patient, these adoring Yellowstone visitors would get to see the alphas leading a hunt or chowing down on a carcass… or playing with their pups.

[SOUNDS OF WOLF PUPS PLAYING AND ADULT GROWLING]

MCINTYRE: You would see this gigantic male wolf start a wrestling match with a little tiny pup, let’s say, maybe a month or two old.

[WOLF PUP PLAYING SFX]

MCINTYRE: And it seemed like 21 would wait for the pup to grab one of 21’s legs or maybe a piece of fur on his belly or something like that. And with the most gentle tug that probably the pup was making, 21 would flop over on his back, pretending that the little pup had just defeated him in battle. It was just another aspect of his personality that was so fascinating to watch.

DOERING: The alpha male Wolf 21 was beloved by the public and it’s no surprise he’s the focus of Rick’s book. But Rick says the alpha female plays just as important of a role, if not more so, in leading the pack. And at one point in the Druid Peak Pack, the alpha female known as Wolf 40 had a leadership style that, well let’s just say it was very different from Wolf 21’s peaceful demeanor.

[SOUNDS OF WOLF SNARLS, GROWLS, YELPS]

DOERING: Competition within packs is normal; after all – the alphas have the best chance of passing on their genes, and there can only be one alpha male, and one alpha female. And sometimes, she’ll do anything to gain power.

Wolf 21 at 5 months old. His pack was relocated to an acclimation pen after the alpha male, 21’s father, was shot and killed just outside of the Yellowstone National Park boundary. (Photo: NPS / Barry O’Neill)

MCINTYRE: We don't know exactly what 40’s problem was, but she had a very violent and aggressive personality. She drove her own mother out of the pack, and then one of her two sisters, so that she was now the alpha female.

DOERING: For years, she relentlessly bullied and abused her remaining sister, who didn’t seem to be able to fight back.

[SOUNDS OF WOLF SNARLS, GROWLS, YELPS]

DOERING: She’d bite and beat up “Cinderella”, which is what the Wolf Project researchers nicknamed the underdog. There were signs that the old alpha even killed her sister’s pups two years in a row, in 1998 and ‘99. A wolf pack can only feed so many hungry mouths, so this kind of behavior isn’t unusual, though it sounds cruel. And the big, powerful Wolf 21?...

MCINTYRE: Male wolves in the wild seem to have a compunction against doing anything that will harm a female.

DOERING: … He could only stand helplessly aside as the aggressive female attacked their pack. Then, in 2000, something happened that changed his destiny and the fate of the Druid Peak Pack. The wolves ended up having four litters that spring. That meant a lot of hungry mouths to feed. And “Cinderella” had her pups in a den a few miles away from her abusive sister. One night in May, the alpha female, Wolf 40, decided she didn’t want to put up with competition from her sister 42’s young pups.

[SOUNDS OF WOLF SNARLS, GROWLS, YELPS]

The Druid Peak Pack chasing bull elk in Yellowstone. (Photo: Doug Dance)

MCINTYRE: As far as we can tell, for the first time in her life, 42 actually stood up to her sister. She had to, to protect her pups, and in a fight with her sister 42 could not win, she just did not have the killer instinct.

DOERING: But some younger females in the pack had been bullied too, and they came to her aid.

MCINTYRE: So when I came out early the next morning, I found wolf 40 lying next to the road just drenched in blood, covered with wolf bites. And she died of blood loss just a short time after that. So all those years of abuse that 42 had suffered from her sister, it culminated that night.

[SOUNDS OF GROUP HOWLS]

DOERING: And “Cinderella” became the new alpha female of the Druid Peak Pack.

[GROUP HOWLS]

DOERING: Now she and Wolf 21 reigned over the grand Lamar Valley.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

A Druid pup scratches its back by rolling on the snow. (Photo: Bob Weselmann)

DOERING: They had a strong pair bond and seemed meant for each other, Rick says.

MCINTYRE: It really was a special thing. They spent at least two thirds of their life together. They were devoted to each other.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: It was a bond that knit them tighter together with time.

MCINTYRE: They were both born with jet-black fur, and as sometimes happens with married couples that are together for decades and decades, as they grew old they looked even more and more like each other, so they started to turn grey about the same pattern.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: Every morning, Rick rose at 3:30 or so to get out in the field and watch their lives unfold. To see what he could learn from the behavior of the alpha male and the many litters he raised with 42.

Wolf 21 at age eight with a lot of gray on his black coat. (Photo: Doug Dance)

MCINTYRE: He was so dedicated to his family, to his friends, he would do anything for them. Certainly, risk his life constantly for them.

DOERING: Even provide emotional support.

MCINTYRE: Especially with the younger wolves in his family. There was a time where he noticed that one of his young sons was being bullied by the other yearlings, and 21 went out of his way to go to that one particular yearling and give him special attention in front of the other young males.

DOERING: And if you’re a young wolf in a pack and the alpha male comes over to you –

MCINTYRE: -- and gives you special attention like he approves of you, that’s a pretty big deal.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: Rick says this kindness and empathy made Wolf 21 stand out.

MCINTYRE: He certainly was an ideal role model for me, and for everyone else that knew him. If all of us could be more like 21, or like 42, the world would be a lot better place.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

Alpha female Wolf 42, longtime mate to 21, when she was eight years old. (Photo: Steven Hargreaves)

MCINTYRE: So this one particular day in late January I saw the two of them come together, it was just the start of the mating season, and they were very affectionate with each other and from a distance of about a mile or two away, I saw them have a mating.

It was very touching, because they laid down as they were still mating, and he put one of his paws around her shoulder in a very affectionate way.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: The next morning Rick got up as usual hours before sunrise and soon spotted the family. He could see the patriarch. But where was his mate?

He couldn’t get a signal from her radio collar.

“Cinderella” was missing.

Rick and his colleagues started searching for her.

MCINTYRE: We found out what happened to her that night.

DOERING: The wolf project tracking plane circled over where it looked like there had been a big fight. The alpha female lay still in the snow, the latest victim of a wolf battle, with the rival Mollie’s Pack.

MCINTYRE: But 21 did not know.

[SOUNDS OF MOURNFUL WOLF HOWL]

The Druid pack (Photo: Steven Hargreaves)

DOERING: He spent the next two months going in a search pattern throughout his territory, as far as I could tell, acting like he was trying to find her. And he never did.

[SOUNDS OF HOWLS AND WIND]

MCINTYRE: And I could see that he was rapidly experiencing a physical decline. He was turning gray at a much faster rate than he had just a short time before that. He seemed to be listless. He just wasn't the same as he had been prior to that time.

DOERING: Before long, 4 months had passed since she had gone missing. It was June now, nearly the longest day of the year. Rick was up early as usual, watching the pack.

MCINTYRE: And some of the younger adults in the family had a few elk come into their meadow.

DOERING: The young Druids eagerly gave chase, but…

MCINTYRE: I looked over at 21, and he just was lying there, he just had no energy left to join in that hunt. And that was the moment that I realized that this was really about it for 21, that this was so unlike him. And that was the last time I saw him.

DOERING: A month passed with no sign of what had happened to the old alpha male. Then, in mid-July, a grim discovery. An outfitter found wolf remains with a radio collar that had long since stopped working. Rick and a pack of other Wolf Project and park employees rode on horseback up to the meadow where he had been found.

DOERING: It had been a special rendezvous site for the Druid Alphas, a place to meet up.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

Wolf 21 and 42 on the move, on their last day together (Photo: Kim Kaiser))

MCINTYRE: He decided to go one last place, way up in the mountains. One last place where there might be a chance of finding 42.

DOERING: She wasn’t there, but a tree they’d marked together many times might have held a trace of her scent. He’d curled up and gone to sleep one last time in the shade of that tree, maybe dreaming of his long-lost love.

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

DOERING: Rick McIntyre’s 2020 book is called The Reign of Wolf 21.

CURWOOD: That’s Living on Earth’s Jenni Doering.

Related links:

- Find the book "The Reign of Wolf 21" (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Learn more about the Yellowstone Wolf Project

- Learn about wolf restoration in Yellowstone

- Listen to "Wolf Eyes" by Paul Winter

[Paul Winter, “Wolf Eyes” on Common Ground, A&M Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Teresa Shi, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth