December 3, 2021

Air Date: December 3, 2021

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Bad Air Polluting Our Brains

View the page for this story

Air pollution causes serious damage to our bodies, sometimes resulting in premature death, and it’s also messing with our minds. Kristina Marusic is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News, which published a 5-part series about how air, water, and climate pollution shape our mental health, and she joins Host Bobby Bascomb for the first part of our coverage of this series. (13:23)

Chemicals and the Obesity Epidemic

View the page for this story

With two out of three Americans overweight and a third considered obese, a new meta-study correlates the phthalates in plastics not only with bigger waistlines but also a wide variety of other disorders including male and female reproduction problems and mental health troubles. Phthalates are ubiquitous in the environment, including fast food hamburgers, medical tubing and personal care products. Biologist Maricel Maffini, the lead researcher in this study, joins Host Steve Curwood to discuss the urgent need for authorities better regulate phthalates. (15:37)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

This week on Beyond the Headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Steve Curwood to talk about how organized crime is fueling deforestation, a study that suggests potty-training cows could help curb their emissions, and a message to Congress by President “Teddy” Roosevelt back in 1907 warning about the limits of resource extraction. (04:59)

Fur-Thief Birds

View the page for this story

Dozens of YouTube videos show daring little birds pulling hair right out of sleeping dogs and other mammals, but only recently have scientists become interested in this phenomenon. They’ve coined a new word for it: “kleptotrichy”, from the Greek words meaning “to steal” and “hair”. Living on Earth’s Don Lyman reports on why scientists think titmice, crows, and starlings engage in this risky behavior. (02:13)

YouTubers Launch “Team Seas” To Clean Up The Oceans

View the page for this story

The world’s oceans are in trouble: an estimated 20 billion pounds of plastic trash are dumped in the ocean each year, wreaking havoc on the planet. Now a group of YouTube influencers calling themselves “Team Seas” are working together to stem the flow of trash. Mark Rober, a YouTuber, engineer, inventor and co-organizer of the campaign, joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about Team Seas’ $30 million goal to collect 30 million pounds of trash from the world’s oceans. (10:17)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

211203 Transcript

HOSTS: Bobby Bascomb, Steve Curwood

GUESTS: Maricel Maffini, Kristina Marusic, Mark Rober

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Don Lyman

[THEME]

CURWOOD: From PRX – this is Living On Earth.

[THEME]

CURWOOD: I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Researchers find chronic exposure to air pollution, even at levels considered safe by the EPA, is taking a toll on mental health.

MARUSIC: All the levels of air pollution exposure they looked at were below legal limits, so they didn't exceed, like the daily threshold for particulate matter pollution for on any of those days where they saw a corresponding spike in ER visits.

CURWOOD: Also, YouTube influencers raise money for ocean cleanup, starting with rivers.

ROBER: One percent of the rivers in the world contribute to 80 percent of the plastic flowing to the ocean from rivers. So, if you can put these trash eating robots at the mouths of these rivers then you can stop it at the source.

CURWOOD: That and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Bad Air Polluting Our Brains

Melanie Meade has become the face of clean air advocacy in her town of Clairton, Pennsylvania, which sees high levels of both air pollution and mental illness. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie)

CURWOOD: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley Studios at the University of Massachusetts Boston, this is Living on Earth. I’m Steve Curwood.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

Today we present a pair of new and disturbing reports that show some surprising and devastating health effects from pollution and synthetic chemicals. One of the recent studies reveals how a group of poorly regulated chemicals, often found in plastic, have strong links to chronic diseases including diabetes, obesity, and insulin resistance as well as behavioral disorders. We will have more on that later in the program. But first let’s consider the growing body of evidence linking air pollution to devastating effects on human health. In previous shows we’ve talked about scientists who have found a link between the tiny particulates from the exhaust of burning fossil fuels and roughly 300,000 excess deaths a year in the US, and millions more around the planet. Well, it also turns out that air pollution is literally messing with our minds. Investigative reporter Kristina Marusic has been digging into the connection between air pollution and mental health as part of a series on mental health and pollution for Environmental Health News. She focused her reporting on Western Pennsylvania, one of the worst regions in the country for air quality. Kristina Marusic, welcome back to Living on Earth!

MARUSIC: Hi, thanks so much for having me.

BASCOMB: Well, let's dig into some of the research that you were looking at for this article. Tell me about the 2019 study between the US and Denmark. What did they find?

MARUSIC: So, the 2019 study, you mentioned, looked at mental health data from 151 million people in the United States and 1.4 million people in Denmark. And they also looked at air pollution data, I spoke with one of the lead authors of that study and he mentioned that they had more detailed data for the Denmark group than they did for the American group. And the link between air pollution and mental illness for that group was even stronger. So, in just the people in Denmark, which again, was still a pretty big study, it was 1.4 million people across Denmark, they found that air pollution exposure was linked to a 31% increase in bipolar disorder, a 104% increase in schizophrenia, and a 210% increase in personality disorder and a 68% increase in major depression. So, the researcher I interviewed said he was personally really surprised by how strong the signal was, they did try to adjust for some of the other factors that could play a role in mental illness. So, things like parental education levels, employment status and income. So, they did try to you know, because the study didn't put people in a lab and expose them only to air pollution and then measure the results.

Children’s worsening mental health effects may be linked to small particulate matter air pollution, which comes from sources like the burning of diesel fuel. (Photo: Indiana Public Media, Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

BASCOMB: You can't do that.

MARUSIC: Right, you can't do that ethically. So, you know, more research is certainly needed. But this was a big red flag for researchers that it certainly appears that exposure to air pollution can have a pretty substantial impact on our mental health.

BASCOMB: The study out of Denmark is pretty alarming, but it's not alone. You talked about another study out of the Cincinnati Children's Hospital that found a very clear link between spikes in air pollution, in this case, PM 2.5, and emergency room visits for children with mental health problems, what was going on there?

MARUSIC: So that study came out of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center and they looked at five years of emergency room data for more than 6,800 children under the age of 18 who visited the ER for psychiatric distress, including anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, suicidality, personality disorders and schizophrenia. And they found that children who were exposed to high amounts of air pollution were significantly more likely to a few days later end up in the emergency room for a mental health problem than children with lower exposures were. Another thing that was really interesting about that study is that all the levels of air pollution exposure they looked at were below legal limits. So, they didn't exceed like the daily threshold for particulate matter pollution on any of those days where they saw a corresponding spike in ER visits. So that study is part of a growing body of research that indicates that air pollution exposures are harmful to human health at levels that are well below current legal limits.

BASCOMB: Wow. So, EPA says that this is our standard for air pollution and this is a safe level but that's not the case, at least when we're looking strictly at mental health problems associated with those exposures.

MARUSIC: Right, so EPA is currently considering lowering the threshold for particulate matter. They're expected to do that sometime in the next couple of years. And I would say in the last five years, scientists have started learning a lot more about these lower levels of pollution and how they're harmful so hopefully, regulations will start to catch up.

BASCOMB: And what do scientists think is the mechanism for air pollution to affect the mental health in this way?

MARUSIC: So, scientists are still trying to figure out exactly what happens in brains that are exposed to air pollution that affects mental health and cognition. But a lot of them think it's related to the inflammation that air pollution causes. So, we know that chronic inflammation in the brain can damage neurons that are involved in the brain and nervous systems, regulatory responses, which can impact mental health if you think about things like anxiety, that is you know, it's a lot more than just our brains that are involved in that process. Right, it's our whole body's ability to regulate and respond to challenging situations.

BASCOMB: Well, part of your article focuses on the work of an activist named Melanie Mead. Tell us a little bit about her story please.

MARUSIC: So, Melanie Mead lives in Clairton, which is a little bit south of Pittsburgh, still in Allegheny County, and Clairton really has some of the worst air pollution in the country. There's a huge industrial facility, there, it's US Steel's Clairton Coke Works and they convert coal into Coke for steelmaking. And that process involves heating coal to extremely high temperatures, which emits a lot of pollutants. The facility is regularly fined and regularly sued by both residents and environmental groups for violating clean air laws and sometimes failing to notify residents when there's a health hazard. Melanie has been a clean air advocate in Clairton for about eight years. She grew up there but moved away for a while and ended up moving back. And when she initially found out that kids in Clairton school districts have asthma rates that are more than double the national average, she was outraged, and she thought that everyone else would be too. Instead, she's really faced an uphill battle where she feels like, you know, a lot of her neighbors feel like it's just the way it's always been and we depend on jobs from the plants and, you know, there's kind of nothing we can do about it at this point. So, she has felt really disheartened, which, you know, is something that she said has negatively impacted her mental health. But she was also surprised to learn that air pollution can cause you know, physical changes in the brain that can impact mental health too. And she actually felt kind of validated learning that she said, you know, we have a lot of people in my community have mental health struggles. And then, you know, one thing that really struck me about her story was that when she was grieving the loss of both of her parents in a relatively short time period, she sought mental health services but she had to go across town to get them. And she said, you know, for a lot of people it's already hard enough to ask for help and then a lot of people here don't own cars, and public transportation is not reliable and so it's really just too many barriers to care. So, you know, she's really hopeful that areas that have high levels of pollution will also eventually get, you know, additional mental health resources.

BASCOMB: And to what degree is this an environmental justice issue? I mean, how likely is it that lower income and minority groups are disproportionately experiencing mental health challenges that can be traced back to this type of air pollution?

U.S. Steel Edgar Thompson Works in Braddock, PA. (Photo: Njaimeh Njie)

MARUSIC: So, air pollution travels, right. So, air pollution affects everybody who is in a geographic region that experiences high air pollution. So, in western Pennsylvania it certainly impacts all of us. But many of the communities that experienced the highest levels of pollution, and those frequent spikes of air pollution, like those ones that sent more kids to the emergency room, in the Cincinnati study, also experienced other community stressors like poverty, crime and racism. So, in the Cincinnati study that we talked about, they found that children from neighborhoods experiencing high levels of poverty were the most likely to experience a mental illness crisis following spikes in air pollution. And they hypothesize that this could be because poverty and living in a place with lots of crime also both cause stress, which also results in inflammation which can harm our brains and our immune systems, which could then worsen similar impacts from air pollution exposure. And there are examples of these kind of what some researchers call toxic zip codes across the US. And so those are regions where a combination of environmental injustice, racism and poverty creates substantial, overlapping negative mental health impacts. So, for example, the Monongahela Valley, which locally is referred to as the Mon Valley, is a collection of former steel towns bordering the Monongahela River between Pittsburgh and West Virginia and it's an area that regularly sees some extreme spikes in air pollution, leading to some of the dirtiest air in the country because it's a valley. So, pollutants tend to get trapped there, if there's a weather inversion, depending on wind patterns, that's where kind of all the pollutants in the region sink to and stay on a bad air day. And those municipalities in the Mon Valley, many of them are majority black and people of color communities and they also have poverty rates ranging from 16% to 40%, which is significantly higher than the national average of 13%. So historically, these communities ended up in these places they get stuck with higher pollution because of practices like redlining which restricted where people of color could live. And, you know, we know from general studies of environmental justice in the US that polluting facilities are much more likely to wind up in in low-income communities than they are in affluent communities. So, it really becomes an issue where all of these environmental exposures are kind of combining with other overlapping impacts to create a real impact on… on mental health in those areas.

BASCOMB: Now, what about other parts of the country? How common is it do you think that people might be suffering from mental health problems associated with air pollution and maybe not even aware of it?

Kristina Marusic is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News. (Photo: Courtey of Kristina Marusic)

MARUSIC: So, there are a lot of places across the US where federal air pollution thresholds are exceeded on a pretty regular basis. We've come a really long way since the passage of the Clean Air Act and we've seen really vast improvement in health that's directly tied to that, but it's certainly not a problem we have solved. So, I mentioned, you know, some of those toxic zip codes that are in this region. And those exist across the country, every state you look in, you can find a zip code where they have more exposure to land and contaminants in the drinking water, and they also are exposed to higher levels of air pollutants. And for anyone who lives in an urban area this is a relevant question, we get more air pollution from traffic and from industrial processes. One thing I think is important to keep in mind is that on an individual level, air pollution certainly matters and can increase the likelihood that if you're already disposed to mental illness, being exposed to air pollution might kind of tip you over the edge but really all of these studies, the implication is at a population or community level. If we were able to stop a specific community that's exposed to really high levels of air pollution from being exposed to that air pollution, we could prevent many emergency room visits for mental illness, we could save lots of money in health care costs, you know, we would have more resources to allocate to communities that really need mental health services, because we would decrease the need for them. So, this is definitely a question that's, that's relevant for all of us in the US and especially for people who live in cities or near industrial polluters.

BASCOMB: Kristina Marusic is an investigative reporter with Environmental Health News. Kristina, thank you so much for taking the time with me today.

MARUSIC: Thank you so much for taking time to talk with me.

Related links:

- Environmental Health News | “Air Pollution Can Alter Our Brains in Ways That Increase Mental Illness Risk”

- Click to see the full 5-part series from Environmental Health News

- Kristina Marusic’s website

[MUSIC: Joshua Messick, “Lo, How a Rose E’er Blooming” on Hammered Dulcimer Christmas Volume II, traditional, self-published]

CURWOOD: Coming up – how expanding waist-lines are linked to the poor regulation of chemicals. Keep listening to Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information at sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you!

That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Chandler Travis Philharmonic, “Cymbal 426” by J.Spampinato/J.Styklunas/R.Bates/B.Pilkington/M.M.Chenevert/Chandler Travis on Llama Rhymes, self-published]

Chemicals and the Obesity Epidemic

Phthalates get into our food through packaging and food handling equipment like paper, cellophane and plastic wrapping. (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

It turns out many health dangers of some plastic chemicals have been hidden in plain sight. Phthalates are a group of synthetic compounds often used to make plastics more flexible and they’re found in everything from personal care products to food packaging and even medical tubing. It’s been known for years that phthalates can pose health hazards to male development. And more recently phthalates found in fast foods were linked to deadly forms of heart disease among middle aged people. And now thanks to a new meta study, phthalates are correlated with a wide variety of chronic diseases in every demographic including women and children. Those health hazards include diabetes, obesity, and even mental and behavioral problems. The research team included an American, a biologist at University of Gothenburg in Sweden and three researchers in Switzerland. For more than two years they compiled more than three dozen studies of the health effects of phthalates to reveal this wide array of chronic diseases linked to the chemicals, links that until now have been largely ignored for risk assessment. And the US Food and Drug Administration, still considers phthalates safe in food and cosmetics. The research team was led by PhD biologist and independent consultant Maricel Maffini, who joins us now. Maricel welcome to Living on Earth!

MAFFINI: Thank you very much.

CURWOOD: Your study is a real eye opener. I mean, this compilation of a bunch of studies really points to the fact that metabolic disease, obesity, pancreatic issues might well be involved here. I mean, you consider the two thirds of US adults are considered overweight and one in three US adults is considered to be obese. What does your study or studies suggest about the relationship between these plasticizing chemicals and the fact that so many of us are well, on the heavy side?

MAFFINI: Well, I want to add that in addition to being plasticizers, phthalates are used in many other ways. They are used in inks, in printing inks, in fragrances to carry fragrances longer, in adhesives, so they are really everywhere in our house. So one of the things that we identified was that relationship with increased body weight. And it seems like they are involved in how we regulate our metabolism. So how much can we burn off the nutrients that we need to power our bodies and if we don't burn them all or as much, and they accumulate in the body that's how we get a little a little bit toward the heavy side. So in this case, what we saw is that there is an increase in a body mass index, there's an increase in the circumference of the waist, and phthalates may be related to that, because they increase the accumulation of fat in the adipose tissue, they also reduce the metabolism of the body by for instance, reducing or being associated with the reduction in the levels of thyroid hormones that we produce, in addition to the fact that they also appear to be working against how our muscles use energy and instead of using more of that energy, that energy is accumulated as fat tissue.

CURWOOD: And part of your research points to papers that show a connection between phthalates the insulin resistance in children and men and women. In other words, diabetes or diabetes like conditions that are so prevalent in our society now.

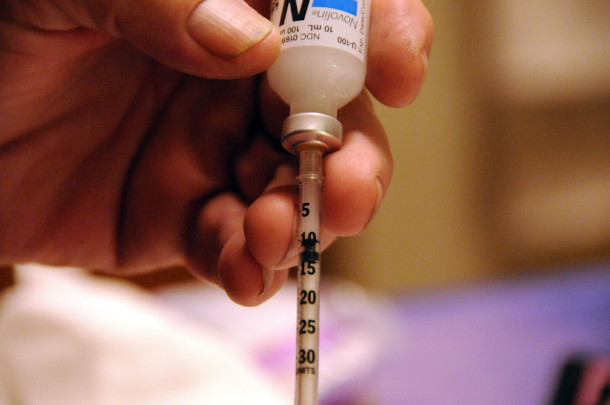

The meta-study of ortho-phthalates found that two of the five chemicals (DIBP and DEHP) were associated with insulin resistance in children, men and women. (Photo: momboleum, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

MAFFINI: That's correct, and those are two of the measurements or the health effects that we saw that are very, very prevalent as you mentioned. And they are not usually looked at when we studied chemicals in animals. So, we are looking at when we test chemicals in animals, we are really not looking at what is prevalent in the society in the human population. We are looking at the weight of organs, we take organs and put them on a scale, and we measure if they reduce the weight, or they increase their weight. But we are not studying things like are we getting these animals to be diabetic? Are we getting these animals to change their behavior when they are exposed to these chemicals? Do we get them fat? We don't really study much so there are things that we need to do better when it comes to risk assessment of chemicals.

CURWOOD: In fact, not part of your study but recently a group at New York University suggests that exposure to phthalates over a period of time is linked to higher cardiovascular events and mortality.

MAFFINI: That is correct. That was Dr. Trasande from NYU. Yes, he was part of that study.

CURWOOD: And of course, what you're referring to is that the regulations don't consider this, that when United States chemical regulators look at these chemicals, they don't consider the kinds of effects that you're finding but instead, they do this in animals, and I gather they focus a lot on male reproduction?

MAFFINI: That is correct because phthalates, mostly because of one of them that is called DEHP is a well-known chemical that interfere with the male hormones. And they're very known for disrupting the development of the male reproductive system. So, because of that, most of the studies done for many years on phthalates, were about whether or not they cause those problems. And other issues that may be happening were not really looked at. So, the regulators use those animal studies, and they looked at the male reproduction, and based on those effects then they established what is called a safe dose.

CURWOOD: But now how does phthalate exposure affect women and children?

MAFFINI: Well, that was one of the very, it was surprise to us to see how little phthalate exposure is needed to see effects in the ovaries, for example. Women were having fewer eggs in their ovaries and children born to mothers exposed to phthalates, to the higher levels of phthalates, were found to have behavioral problems, problems with learning, lower IQ, or decrease abilities to make decisions, or motor skills with their hands and their movements.

CURWOOD: Now, why can exposure to small doses be more troublesome than large ones? Why would such tiny doses have such a huge impact for women and children?

MAFFINI: That is usually associated with some hormonal effects. So, your natural hormones, your androgens, estrogens, thyroid hormones, insulin, they are incredibly effective information molecules, signaling molecules. So, when you have chemicals that are acting in similar ways or interfering with the function of hormones, you don't need much to see an effect. And some of those effects may look like something that we couldn't pay much attention to. But later in life could be triggered by other exposures, it could become a health problem.

CURWOOD: One of the remarkable findings that you have here also regards to mental illness, mental illnesses is at an all time high in the United States and Europe, at least measured, and it's documented that one in five US adults will live with mental illness. What do we know so far about the connection between phthalates and mental health mental development?

According to the CDC, medical costs related to obesity total more than $140 billion a year in the U.S. (Photo: Marco Verch, Flickr, CC BY-ND-ND 2.0)

MAFFINI: What we know is mostly related to children exposures and mostly children's exposed during development. So when your brain is developing, in general, when any organ is developing, it follows a sequence, it's like when you're writing a symphony, everything has to happen in an orderly way, at a particular time, for a particular duration, for things to your cells to develop, to proliferate, to differentiate into the different parts of the brain, to be located in specific areas of the brain and therefore those cells and connections to happen. So, when things don't go the correct way during brain development you cannot go back and rewire the brain. So, we are seeing issues with children when it comes to behavior, when it comes to learning disabilities, when it comes to delinquency that are associated with phthalates and mostly with the phthalates in the mom. When the mom was exposed depending on the trimester in which she was exposed, which organs were being developed at that particular time, then the children, we can see those effects. But I think again, phthalates are just our way to show the concerns and the problems with the way we do risk assessment and manage chemical exposures because these are just five of the large families of phthalates and of a much larger chemical soup in which we are all living. So, there could be what people call cocktail effects, that then there are other chemicals that are also affecting the brain and I can give you another list of those affecting brain development.

CURWOOD: So how are these chemicals regulated in the European Union compared to the United States?

MAFFINI: In the European Union, there are a few more limitations. And there are specific doses, reference doses or safe doses that some phthalates specifically these five that we'll look at should comply with. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration that regulates chemicals in food, do not have limits on how much phthalates could be in the food supply. So, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, they do have limits on phthalates, for children's toys and for other articles that are used for children uses, like the teethers when kids are teething, there are some soft plastic rings, rubber duckies all those were removed from phthalates. But here's the problem, all the agencies are doing a risk assessment for each particular chemical and these chemicals are all alike and they should be regulated as a class. Because they are similar, you remove one because there's a regulation and you are a new one, they will have the same function and you will be in compliance. So, until we start regulating chemicals that are similar and have similar health effects and they look alike as a class, as a group where we have a safe dose for all of them, not a safe dose for each individual. If we reduce the exposure levels, we will be better off, and it will be more efficient.

CURWOOD: So, I have to say that your, your study is simply shocking. I mean pointing to the relationship between obesity, mental health problems, child development problems, delinquency, diabetes, I mean, the list is so long pointing to this group of chemicals. Why didn't we know?

Maricel Maffini has a PhD in biological sciences from the National University of Litoral in Argentina and worked at Tufts University School of Medicine for more than 11 years; she now works as a scientist and independent consultant. (Photo: Courtesy of Maricel Maffini)

MAFFINI: I think, I think we didn't know because we don't communicate properly. We have and we call this in the paper the bookends, bookends of environmental health. On the one hand, at the beginning of when a chemical is going to get into commerce there are regulators looking at the information that companies provide to show that the chemical use is going to be safe. On the other end you have the healthcare providers, that they see people, they see their struggles, they see their health problems, they see dysfunctions of organs, they see behavioral problems and most of the things do not have a genetic component, as you mentioned at the beginning. So, they start to look at what is in their environment. What is in the house? What do they eat? Do they have lead paint in the houses? Those type of things, and they generate some of the information that then we use in our paper. But the healthcare professionals and the regulators don't talk to each other. So, until we understand that with so much human data should be informing the regulations, very little is going to change. And phthalates is just one group of chemicals that have been in commerce for decades. This is what we use just to make the case, we need to turn the system upside down.

CURWOOD: Maricel Maffini is a biological scientist. Thanks so much for taking time with us today.

MAFFINI: Thank you for having me, it's been a pleasure.

CURWOOD: So, Bobby, Maricel Maffini brought an interesting pedigree to this work.

BASCOMB: Oh, really what’s that?

CURWOOD: For more than a decade she worked with Ana Soto a researcher and investigator at Tufts University Medical School in Boston. Dr. Soto is famous for noting some thirty years ago that breast cancer cells grew faster in plastic tubes, as if the cells were in the presence of estrogen. This was some of the earliest work documenting that some chemicals in plastic can mimic hormones and cause health problems.

BASCOMB: Uncovering so many more diseases linked to phthalates is pretty shocking, Steve! And we know that phthalates are found in everyday products from our TV remote controls and hairbrushes to our food.

CURWOOD: Yeah, and big money is involved here. The US chemical industry has more than $750 billion in sales every year and it’s closely linked to fossil fuels, which are the feedstocks for most plastics. But the CDC says chronic health costs for just heart disease, diabetes, and obesity in the US add up to close to $650 billion each year. That doesn’t include the health care costs of many other associated diseases and you can’t put a price on human misery. Of course, removing phthalates from our everyday products would require major regulation and I think it’s safe to assume that would bring push back from industry.

BOBBY: I’m sure. Well, let’s hope studies like these spark much better regulation of phthalates and other environmental health risks.

Related links:

- Read the study: “Role of epidemiology in risk assessment: a case study of five ortho-phthalates”

- Check out the Living on Earth story on phthalates and cardiovascular disease

- CDC Fact Sheet on Phthalates

[MUSIC: Preservation Hall Jazz Band, “Kreyol” on A Tuba To Cuba, by Benjamin Jaffe, Sub Pop Records]

CURWOOD: Coming up – A moo loo to potty train cows and reduce nitrogen contamination from farms. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining a passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[CUTAWAY MUSIC: Preservation Hall Jazz Band, “Kreyol” on A Tuba To Cuba, by Benjamin Jaffe, Sub Pop Records]

Beyond the Headlines

Organized crime is fueling deforestation in tropical areas including in South America (Photo: A.Davey, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Bobby Bascomb

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood.

And joining me now on the line is Peter Dykstra. Peter's an editor with Environmental Health News that's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. And he's down there in Atlanta, Georgia, looking over what's beyond the headlines for us. Hey, Peter, how you doing? And what do you see today?

DYKSTRA: Doing all right, Steve, and we're looking at a study by a Texas State University professor, named Jennifer Devine, on what she's found is that organized crime is a driver in a lot of global deforestation. We often think of the products that the rainforest is sacrificed to be turned into beef cattle ranching, soybean production, palm oil plantations, and of course, timber products. But organized crime has its hand in a lot of the activity that is turning our tropical rain forests into open land or farming land.

CURWOOD: So, what's the inducement for crooks to get involved in this?

DYKSTRA: Well, a couple of things, in some areas they're directly involved in what replaces tropical rainforests when those replacements are coca farms to make cocaine. In other areas, it's a simple link between the illegal logging that goes on, and the illegal money laundering that enables much of organized crime and enables some of what's going on in the rainforest.

CURWOOD: So, I suppose it is easier for crooks to smuggle illegal timber than it is to smuggle cocaine, huh?

DYKSTRA: It is, it's easier to hide your cocaine in illegal timber shipments. But that money laundering is a big part of it again, not just in South and Central America, but throughout the tropical world, places like Malaysia and Indonesia, where much of the world's palm oil production is based.

CURWOOD: So, this is another way that cooks can well have a beef, huh?

DYKSTRA: They can have a beef. And speaking of beef, we've got another item to discuss there. You want to hear about it?

CURWOOD: Yeah. Okay.

DYKSTRA: It's called the MooLoo, based on a small study published in the journal, Current Biology, and the MooLoo, is a way, to get this, potty train dairy cattle in order to capture some of the polluting elements of their waste products.

Potty-training cows could offer a way to curb some of their harmful greenhouse gas emissions (Photo: Kabsik Park, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

CURWOOD: Okay, Peter. So, you're going to potty train a cow?

DYKSTRA: Well, it's easier if you potty train a calf. And those young cows are fed sweet treats, incentives, if they go into the right stall to pee. That pee is then captured so it doesn't become ammonia and nitrous oxide in the air, helping create air pollution, helping create more global warming. And instead, in the small study, 11 out of 16 calves were taught how to use the stall that helps stall their pollution. See what I did there.

CURWOOD: And actually, the urine is a big deal because there's a lot more nutrient dense stuff in urine then in the solid matter, what we generically call cow poop.

DYKSTRA: It does. And we're waiting for a PooLoo to come along to take care of the rest. But it's a potential step forward. Kind of a weird one. And it's a small study, but we'll see if this is a technique to reduce the amount of pollution that dairy cattle costs.

CURWOOD: Hey, Peter, it's that time in our chats where you usually look back in history. Give us an interesting nugget. What do you have for us today?

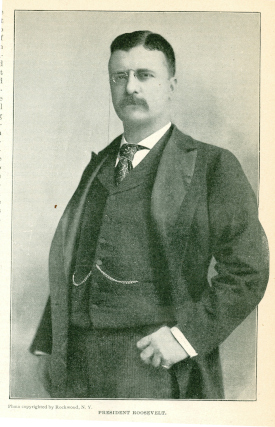

President Theodore Roosevelt is credited with many conservation efforts in the US (Photo: Political Graveyard, Flickr CC BY 2.0)

DYKSTRA: An item from December 3, 1907. In the annual message to Congress, that's the predecessor to what the President now does in the State of the Union address and that message to Congress in 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt considered to be one of the greatest conservationist presidents we've ever had, told this to Congress, and I quote, "We are prone to speak of the resources of this country as inexhaustible. This is not so."

CURWOOD: TR, Teddy Roosevelt, certainly had that one right, huh? I mean, even though he's said some fairly racist things he had quite a career otherwise, I mean, what he created the Forest Service and all those national parks that he stood behind.

DYKSTRA: He did and also the Fish and Wildlife Service. A lot of its impetus came from things like bird plumage. Back around the turn of the 20th century, bird plumage was sought after for women's hats. They were the fashion of the day, TR came around and helped create much of the foundation, the basis of the conservation ethic that many Americans live by today.

CURWOOD: So, thank you, TR. And thank you, Peter Dykstra for telling us these stories today. Peter is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's ehn.org and dailyclimate.org. We'll talk to you again real soon.

DYKSTRA: You're welcome, Steve, and will talk to you soon.

CURWOOD: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth webpage that's loe.org.

Related links:

- The Conversation | “Organized crime is a top driver of global deforestation – along with beef, soy, palm oil and wood products”

- Discover | “Toilet-Trained Cows Could Be a New Pollution Solution”

- Teddy Roosevelt’s 1907 message to Congress about the limits of resource extraction

[MUSIC: Merion Concert Band, “On the Trail” from Grand Canyon Suite, by Ferde Grofe, available on at the band’s channel on Youtube]

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

Fur-Thief Birds

A black-crested titmouse steals fur from a snoozing fox. (Photo: courtesy of Texas Backyard Wildlife)

BASCOMB: Just ahead, YouTube influencers raise money to clean up the oceans but first this Note on Emerging Science from Don Lyman.

LYMAN: Many birdwatchers, citizen scientists, and dog owners have observed birds stealing hair from mammals for some time. In fact, there are dozens of YouTube videos of daring birds pulling hair from sleeping dogs but only recently have scientists become interested in this phenomenon.

Ecologist Henry Pollock was counting birds in an Illinois state park when he and his colleagues saw a tufted titmouse plucking fur from a sleeping raccoon. That observation inspired him to dig deeper into the phenomenon, which researchers have named kleptotrichy, a term derived from the Greek words “to steal” and “hair”.

Searching through the scientific literature, researchers found only 11 anecdotes of birds stealing hair from live mammals. But a YouTube search revealed nearly 100 videos of tufted titmice, a mountain chickadee, and a black-crested titmouse plucking hair from mammals. The latter two bird species had not previously been identified as hair thieves in the scientific literature.

Titmice are the bird species most often seen engaging in kleptotrichy, stealing hair from dogs, foxes, and raccoons, but American crows, red-winged starlings in Africa, and three honeybird species in Australia have also been documented stealing hair from a variety of animals, including cows, antelope, and koalas.

Scientists assumed birds gathered hair for their nests in low-risk ways, perhaps from carcasses or shed hair. Collecting hair from live animals, some of them predators, like foxes, is an obvious risk to birds. So, researchers conclude, the hair must be critically important for them.

Species of birds that harvest hair often live in colder climates, so researchers speculate the birds might use it to insulate their nests. Another hypothesis is that birds might put mammal hair in their nests to confuse potential predators and parasites.

That’s this week’s note on emerging science. I’m Don Lyman.

Related links:

- Find the journal article in Ecology | “What The Pluck? The Theft Of Mammal Hair By Birds Is An Overlooked But Common Behavior With Fitness Implications”

- Science News | “Scientists Have A New Word For Birds Stealing Animal Hair”

- Watch: A snoozing fox meets a plucky little black-crested titmouse

- Watch: Bird plucking fur from sleeping Labrador

[SCIENCE NOTE THEME]

YouTubers Launch “Team Seas” To Clean Up The Oceans

Cofounders of #TeamSeas “Mr. Beast” (left) and Mark Rober (right). (Photo: Screenshot from YouTube video “This Robot Eats Trash #TeamSeas”)

BASCOMB: The world’s oceans are in trouble, and plastic is a huge part of it. It’s hard to know exactly but on the order of 20 billion pounds of plastic are dumped in the ocean each year, wreaking havoc on the planet. Now a group of YouTube influencers are working together to stem the flow of trash to the seas. They call themselves Team Seas and have set a goal to raise 30 million dollars to collect 30 million pounds of trash from the world’s oceans. For details I’m joined now by Mark Rober a YouTuber, engineer, inventor and co-organizer of the Team Seas campaign. Welcome to Living on Earth, Mark.

ROBER: Good to be here.

BASCOMB: So, what is the inspiration for Team Seas? And how did you get involved with the project?

ROBER: Yeah, I have a kind of a science and education YouTube channel that I've been doing for about a decade now. And another YouTuber friend of mine named Mr. Beast, he hit 20 million subscribers two years ago, and the internet said you should plant 20 million trees. And you should, you should have Mark Rober build you a robot to do it. Because that's kind of what I do I build ridiculous things, right. And it turns out, it's really hard to get a robot to plant 20 million trees. So, what we did is we launched a campaign called Team Trees, where $1 is one more tree in the ground. And that campaign went really well, we ended up raising $23 million by involving a bunch of other YouTube friends. And so fast forward two years later, which is now, we followed up Team Trees with Team Seas. And that's what's currently going on right now, where $1 is one less pound of plastic or trash in the ocean. And our goal of this time is to raise $30 million.

BASCOMB: So, it costs basically $1 a pound to remove trash from the ocean. How exactly will that work? And how will the money be spent?

ROBER: Sure, yeah. I mean, this is something we take painstaking efforts to, we realized, you know, the median donation is somewhere around I don't know, $5, which means you do get these big donors that come in. But like that's a lot of tooth fairy money. That's a lot of allowance money. And you know, especially because, you know, a lot of these folks are younger, and they feel passionate. So, we take that super seriously. So, every dollar literally goes towards doesn’t go toward mailings, doesn’t go towards like someone salary, goes towards removing plastic and trash from the ocean. So, we're working with two nonprofits. One is the Ocean Conservancy. They're focusing on the beaches, and the actual ocean going out and removing like ghost gear, which is like a fishing nets, which is a big threat to larger animals. And then the ocean cleanup has something called the river interceptor, which is like a trash eating river monster, which I did a video on. And you know, because at some point, you got to turn the tap off, right? It's one thing to take the trash out of the ocean. But you know, 1% of the rivers in the world contribute to 80% of the plastic flowing to the ocean from rivers. So, if you can put these trash eating robots at the mouths of these rivers, then you could stop it from going to the river at the source, right? So, we're focusing on the beaches, the rivers, and the ocean. And that's how the money will be spent and utilized.

#TeamSeas aims to raise $30 million to collect 30 million pounds of trash from the world’s oceans. (Photo: Team Seas, Wikimedia Commons)

BASCOMB: Yeah, you posted a video of yourself in the Dominican Republic on one of these trash eating river monster robots. Can you tell us more about how it works and what your experience was like down there?

ROBER: Yeah. So, I went out to the Dominican Republic to see one of these things working firsthand. On you know, one of those rivers, that's one of the 1% most offensive rivers. And it was just wild to see, you know, trash coming down the river in the form of like, a couch, a shoe, a tire, a basketball, a pile of trash, a lot of plastic bottles, and this, it runs into this barrier that's about goes a foot and a half deep in the water. So, the fish can swim freely under it all day long. But then the stuff the trash floats, so it gets it goes in, you know gets corralled by this trash robot. And then there's a conveyor belt, and then it goes into like a dumpster basically. And then every either day, depending if there's a lot of trash in the river, or every two weeks, those dumpsters get floated down the river and offloaded. And they get either what's recycled, gets recycled. Otherwise, it just goes to you know, whatever the local waste management is for that area. But importantly, none of it ends up back in the sea.

BASCOMB: I mean, that's an amazing statistic that 1% of rivers account for 80% of the trash coming from rivers, which is a major conduit of garbage.

ROBER: Yeah, that's exactly right. At some point, and look, I went there, and it was really frustrating at first, to see all this trash coming down the river. And it's just like, where's this coming from? Like, who would be this callus and just freakin throw all this trash into the ocean, right? And so, we went up river and we checked it out. And you know, it's coming a lot from like, some of these poor communities. And what you find out is it's like, no, we have this magical ability here in a rich country to, to put you know, our trash in a bin. And then magically, at the end of the day, the trash is gone. Right? Even in the Dominican Republic in the in the cities that are more developed, like of course, that's how it works. But in these remote communities, where they just, a trash truck can't make it up there, right? They don't have the infrastructure to actually do this. Like they are literally living on piles of trash in some cases, which we saw, it was like incredibly difficult even to go up there. And so, it's like, yeah, of course, part of that is going to overflow and they need to put it in the river because they don't have any other option. Right? So, the Dominican government recognizes this. They're one of the leaders in trying to find, you know, systemic solutions to this, you know, the UN is working with them. But the thing is, and the people in these poor communities also still want to be part of the solution, and they're eager to like, participate in this as well. But those things just take time, a lot of infrastructure needs to be set up to make that happen. So, in the meantime, you put these trashing robots on the river, eventually, we will not need them there. But until that day comes, like, this is a great solution to take care of mother, you know, a fist bump to Mother Earth by putting these on some of these rivers.

BASCOMB: I would think it'd be especially a problem in a place like the Dominican Republic, an island, which just, you know, has limited land for dealing with this stuff. I mean, how big can you make a landfill? Not that that's a good way of dealing with your trash. But in you know, you don't want to incinerate it if you don't have proper recycling infrastructure. I mean, what can you do? You know, it's a difficult situation.

Founder of #TeamSeas Mark Rober picks up trash in the waters off the Dominican Republic. (Photo: Screenshot from YouTube video “This Robot Eats Trash #TeamSeas”)

ROBER: Yeah, definitely. And it is interesting to being an island like, you know, some, they do get trash that washes up on their beaches from their own river, that puts it on the beaches, but it's also, you know, being an island, they do get, you know, even I think 3% of the trash on their beaches actually comes from the United States. So, it's like, yeah, being in the middle of the ocean, you, depending on whatever the currents are, some people bear the brunt of it more than others.

BASCOMB:

What do you think about a platform like YouTube or, or TikTok for doing this type of work?

ROBER: It's interesting, because it's like, you know, before to do something like this, you would need like a telethon. And ABC would have to host it, you know, the Jerry Lewis or something, you know, you have these things. And it was like, you had to be really connected to make something like this happen. But with the infrastructure of these tools, where people can like, publish themselves, like YouTube, you know, or Twitter or TikTok, it's cool to see it's a, it's a very interesting and different dynamic when just like someone, a group of people who feel passionate about a thing, can get that message out and to amplify it, and then things can happen. So, it's like a different way to fundraise that hasn't been typically available, I think, historically. And I think you'll start seeing it, you know, more and more, as some of these initiatives get success. And you can because it feels it's very grassroots, right? This wasn't put out by YouTube, this is some corporate thing, this a bunch of like actual people getting together and saying, let's do something cool. And I think that authenticity shines through. And it resonates with people, which is why we're able to raise as much money as we have so far.

BASCOMB: And you know, another thing I think is really encouraging about it is the median age is, you know, young people, it's $5 donations, this is tooth fairy money. So, this is really, you know, young people that care about these issues.

The Ocean Cleanup’s robot that can filter trash from the ocean. (Photo: Screenshot from YouTube video “This Robot Eats Trash #TeamSeas”)

ROBER: Well, that's a big part of it is like, look, we know 100%, we're always very clear about this, we know that $30 million, and 30 million pounds of plastic in trash out of the ocean does not solve the problem. Like that is never what our position has been. But you know, it's a.) 30 million less pounds, and it would have been in there otherwise, and b.) I think, almost more importantly, it's like if you donate even $3 like you are now part of Team Seas, you're on that team. And next time you go to the beach, and you see a water bottle, you know, on the on the sand, you're like, “Whoa, I'm part of team sees. That's not how I roll this, this can't happen.” Right? And so, it’s just, getting it in your psyche that like oh, maybe, you know, given two options at the store, I should choose the option that is a little bit more responsible in their packaging choices or something right? Or do I even really need that? Or can I recycle that, right? It's more of like, just getting us in this mind frame that we only have one earth and it's not an infinite resource.

BASCOMB: So, you guys have done Team Trees, now Team Seas, what's next for your, Team Bees? I mean, they're very charismatic and in decline.

ROBER: They are, yeah, that's been suggested Team Bees, Team Breeze you know, maybe something with climate? I don't know. We'll have to see, we'll have to see how this goes. But you know, it is just such a net positive thing. It's, it's one of like, got to be one of the highlights of my career on YouTube, you know, and even my career and I have like I worked at NASA for nine years. Then I worked at Apple for five years before I became a full time YouTuber. I helped put the Curiosity rover on Mars. I've had some cool moments but like this moment where everyone comes together about a thing there's like such positivity there's such hope there. It's something like we can all agree on right with every all the division in the world. We can all agree that trash and plastic just don't belong in our beautiful ocean to sort of be at the epicenter of that and to watch it happen around me and people get really stoked about a thing is just it's, it's really, really fulfilling.

BASCOMB: Mark Rober is an American YouTuber and co-founder of Team Seas. Mark, thanks so much for taking the time with me today.

ROBER: Sure. It's great to be here.

Related links:

- #TeamSeas Official Website

- Watch: “This Robot Eats Trash #TeamSeas”

- Watch: “I Cleaned The World’s Dirtiest Beach #TeamSeas”

- Watch: “Removing 30,000,000 Pounds of Trash Will Actually Have This Impact #TeamSeas”

[MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Ann Rabson, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, by Leadbetter, M.C. Records]

CURWOOD: The next meeting of the Living on Earth book club is coming up on December 9th at 6:30 pm eastern. We’ll be joined from South Africa by Craig Foster, the filmmaker whose remarkable friendship with an octopus was captured in the Academy Award-winning documentary My Octopus Teacher. His new book is called Underwater Wild. You can register for this free event on December 9th at loe.org/events. That’s loe.org/events. See you there!

[MUSIC: Pinetop Perkins with Ann Rabson, “Careless Love” on Ladies Man, by Leadbetter, M.C. Records]

CURWOOD: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation.

Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Jenni Doering, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Aynsley O’Neill, Jake Rego, Genevieve Santilli, Teresa Shi, Gabriell Urton, and Jolanda Omari.

BASCOMB: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. You can hear us anytime at loe.org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio. I’m Bobby Bascomb.

CURWOOD: And I’m Steve Curwood. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth