March 11, 2022

Air Date: March 11, 2022

FULL SHOW

SEGMENTS

Nations Vow to Curb Plastic Waste

View the page for this story

At a recent UN meeting in Nairobi, Kenya, delegates from over 170 countries committed to come up with an ambitious cradle-to-grave, legally binding agreement to tackle the international plastic pollution crisis. Maria Ivanova served as part of the Rwanda delegation to Nairobi that successfully advocated for this ambitious approach and joins Host Bobby Bascomb to discuss. (09:05)

Beyond the Headlines

/ Peter DykstraView the page for this story

In this week's trip beyond the headlines, Environmental Health News Editor Peter Dykstra joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about how the Biden administration declined to appeal a January court decision that invalidated oil and gas leases sold during 2021. Then they go over a pro-fossil fuels bill in Kentucky calling for a divestment of divestment efforts. And from the history books, they celebrate what would be the 143rd birthday of Albert Einstein. (04:32)

Deep Sea Corals Resilient to Impacts

View the page for this story

In Tahiti, researchers recently discovered one of the largest deep sea coral reefs in the world, spreading for roughly two miles at up to 230 feet deep. It’s in pristine condition, with no evidence of stress from pollution, ocean acidification, or warming water that has killed roughly half the world’s coral reefs in the last 70 years. Laetitia Hedouin made the discovery as a researcher at the Center for Island Research and Environmental Observatory and discusses her findings with Host Bobby (06:55)

Redwoods Returned to Tribes

View the page for this story

A consortium of ten tribal nations are now the permanent guardians of more than 500 acres of coast redwood forest in northern California. Buffie Schmidt with the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council joins Host Jenni Doering to talk about the relationship between this rugged stretch of California coast and the local Native cultures. (08:17)

The Impala Imperative

/ Mark Seth LenderView the page for this story

Living on Earth's Explorer-In-Residence Mark Seth Lender shares the secret of how impala antelope living on the African savanna confuse predators. (03:22)

Miseducation: How Climate Change is Taught in America

View the page for this story

Investigative journalist Katie Worth joins Host Bobby Bascomb to talk about her book Miseducation: How Climate Change Is Taught in America. It reveals the access fossil fuel companies have to American children and how that differs across red and blue states. (14:33)

Show Credits and Funders

Show Transcript

220311 Transcript

HOSTS: Jenni Doering, Bobby Bascomb

GUESTS: Maria Ivanova, Laetitia Hedouin, Buffie Schmidt

REPORTERS: Peter Dykstra, Mark Seth Lender

[THEME]

From PRX- this is Living On Earth

[THEME]

BASCOMB: I’m Bobby Bascomb

DOERING: And I’m Jenni Doering

At a recent United Nations meeting more than 170 nations committed to develop a legally binding agreement to address the plastic waste crisis.

IVANOVA: For me, success will be when we’re not looking at a race to the bottom but a race to the top. Which countries will have the most ambitious plans? Which countries will have the most inclusive participation in those and who will hit the targets first?

BASCOMB: Also, more than 500 acres of coast redwood trees in Northern California have been returned to the native Sinkyone people for safe keeping.

SHMIDT: Sometimes people have referred to it as the Lost Coast, and it's wild, it's the way the creator Yahkapate intended it to be, and a beautiful natural place where redwoods can thrive.

BASCOMB: Those stories and more this week on Living on Earth – Stick Around!

[NEWSBREAK MUSIC: Boards Of Canada “Zoetrope” from “In A Beautiful Place Out In The Country” (Warp Records 2000)]

[THEME]

Nations Vow to Curb Plastic Waste

Located outside of the venue that hosted the UNEA meeting, this sculpture by Benjamin Von Wong suggests that the world must turn off the “tap” on plastics. (Photo: UNEP/Cyril Villemain, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

DOERING: From PRX and the Jennifer and Ted Stanley studios at the University of Massachusetts, Boston this is Living on Earth. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB:And I’m Bobby Bascomb.

The United Nations Environment Program recently wrapped up five days of negotiations in Nairobi, Kenya. Representatives from over 170 countries committed to come up with an ambitious agreement to tackle the international plastic pollution crisis. The world currently produces roughly 300 million tons of plastic each year and just a tiny fraction of it gets recycled. In Nairobi delegates agreed to a cradle to grave, legally binding approach to stem the flow of plastic waste. The resolution has been lauded as the most important environmental multilateral agreement since the Paris Agreement. Maria Ivanova is an Associate Professor at University of Massachusetts Boston and she served as part of the Rwanda delegation to Nairobi that successfully advocated for this ambitious approach. Maria Ivanova, welcome to Living on Earth!

IVANOVA:Thank you.

BASCOMB: So going into this meeting, there were three different options on the table. One was to just tackle single use plastic, another would only address the waste problem in the oceans, and the third was a full lifecycle approach, which is ultimately what was agreed upon here. Briefly, can you remind us, what is a full lifecycle approach? What does that mean, exactly?

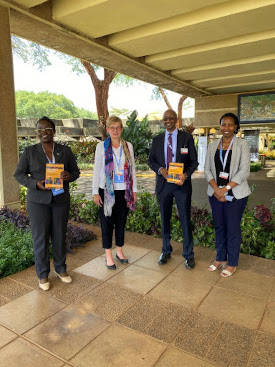

Rwanda and Peru’s ambitious resolution for an international legally binding treaty on plastic pollution was ultimately chosen by representatives at the UNEA meeting. The Rwanda delegation from left to right: Her Excellency Dr. Jeanne D’Arc Mujawamariya–Minister of the Environment, our guest Maria Ivanova–Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director of the Center for Governance and Sustainability at UMass Boston, His Excellency Dr. Richard Masozera–High Commissioner of Rwanda to Kenya, and Juliet Kabera, Director General of Rwanda Environment Management Authority. (Photo: Maria Ivanova)

IVANOVA: A full lifecycle approach is thinking, in a sense, from cradle to grave. It's thinking about a product, from the imagination of what that product will look like, its design, the extractions of the materials, and the production of the product, the use of that product, and the disposal. So the full lifecycle is a simple cradle to grave approach. And for plastics that is very important.

BASCOMB: So this is a resolution to begin negotiating a legally binding treaty. How might that actually be applied in this context? And why is it significant?

IVANOVA: A legally binding treaty is significant, because it provides for accountability measures. This was the most ambitious option on the table, championed by Peru and Rwanda. And so for all countries to agree on a legally binding treaty, meaning that they would be accountable for whatever they do, is very significant, because it will set a regulatory framework that will enable governments to put necessary regulations in place and legislation. But it would also provide a level playing field for businesses that can start innovating. There were a number of businesses represented in Nairobi, including Dow Chemicals, the American Chemistry Council, and others. There was no pushback against the treaty. Indeed, business welcomes an international legally binding treaty, because it will provide the predictability that business needs. This harkens back to the Montreal Protocol, that regulated substances that deplete the ozone layer. It's a very similar setting, that in the Montreal Protocol, governments agreed to regulate those industries. And that led to the development of substitutes. And DuPont was the company that emerged as the champion, because there was a predictable, consistent, constant regulatory framework. So we're seeing a similar dynamic here, even though plastics is a much more difficult problem to tackle, at least at this point.

Our guest Maria Ivanova was honored to be part of the Rwanda delegation, which saw tremendous success during the UNEA negotiations. (Photo: Maria Ivanova)

BASCOMB: So it makes sense, then that companies would want certainty, they want to know if I make a product, I can sell it just as easily in the United States as I can in France as I can in Argentina, because everybody has agreed that this is acceptable.

IVANOVA: Indeed. The issue with plastics is that there are so many ways to make plastics. And there are so many additives, so many chemicals, and so many ways to recycle or not recycle plastics. There are also various ways to substitute for plastics. And I think an international legally binding treaty would enable innovation in this space. And this is what we have seen in Rwanda already, which is a country that has banned plastics, first plastic bags in 2008, and then all single use plastics in 2019. And you've seen how various companies have entered that and come up with substitutes for the plastics.

BASCOMB:So the negotiations will take place over the next two years. And of course, the devil is in the details with these types of things. How confident are you that all of these countries will come together and act in good faith to really address the plastic problem? And not, you know, ultimately try to water it down for reasons that might serve their own self interest?

The president of the United Nations Environment Assembly brings down the gavel as the resolution for an international legally binding treaty is officially passed. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

IVANOVA: That's a difficult question. As you know, with every negotiation, there are a number of interests at play. And we want to see countries commit. And we want to see them deliver on these commitments. It was inspiring to see that happen in Nairobi. And I do want to see that happen over the next two years, and indeed over the next four years as this treaty is being developed. However, governments change. We are in a crisis of multilateralism at the current moment. And we don't know what these commitments will be. Therefore, I think this process opens the space not only to governments that have ambitions but also to civil society, and to businesses, and to academia.

BASCOMB: So nobody quite expected the United States especially to sign off on this, and a legally binding agreement. The US is of course, the largest user of plastic per capita in the world. My understanding is if they sign up on a legally binding treaty, they can be sued domestically for not living up to their agreement. And you are, of course, part of the Rwanda delegation that made this happen. What was in the secret sauce? How were you able to negotiate this and have such success here?

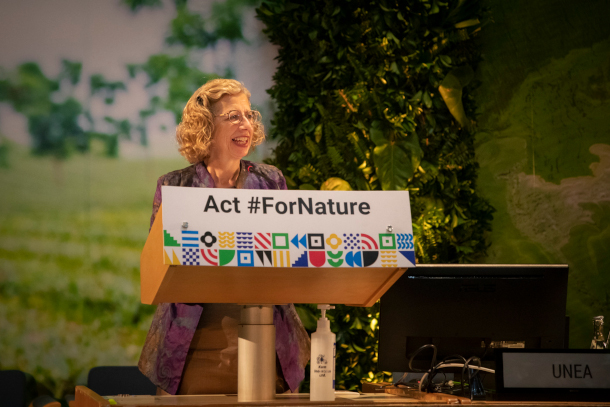

Inger Anderson, the Executive Director of the UN Environment Programme, called the resolution “the most important international multilateral environmental deal since Paris,” referring to the 2015 Paris Climate Accord. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

IVANOVA: I have to say that the US delegation came willing to resolve the problem. There was no reticence on behalf of the United States of saying no, we cannot do this. On the contrary, the United States sees the problem. It sees the incredible opportunity for innovation and was ready to negotiate along with all other countries. So the US delegation was outstanding in its negotiation skills, but it was not pushing for a lowest common denominator. It was not, which was a refreshing sight to see, because we have seen the United States within the past administration pull out of international agreements that the US had already signed, right? And this is to see the United States in a leading position in negotiating an international treaty alongside with two small states, Rwanda and Peru, was really inspirational.

BASCOMB: Well, that is wonderful to hear. And ultimately, what will success look like to you when two years have passed?

Negotiations for an international treaty focusing on the full life cycle of plastic will take place over the next two years. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

IVANOVA: So, success will have many phases. Success will be to have an international agreement, signed, sealed, delivered, but ultimately, success will be when that agreement is implemented. And that kind of implementation can start now with various voluntary approaches that are already taking place. Those should not cease just because we have a process for an international legally binding treaty, they will continue. And I think that they can set the ambitions even higher and higher. But the kind of treaty that we're looking at will allow countries to develop their own national plans of how to deal with plastics. And to me success will be when we're not looking at a race to the bottom, but a race to the top. Which countries will have the most ambitious plans, which countries will have the most inclusive participation in those, and who will hit the targets first? That to me will be the successful, I wouldn't even say conclusion, but implementation of this treaty, because we will not implement this once and for all, this is a big issue. We see plastics are everywhere, and they're necessary, but we have to find a way to deal with them in a way that does not harm human health and planetary health.

Delegates from over 170 countries came together to discuss global plastic pollution at the fifth session of the United Nation Environment Assembly meeting in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo: UNEP, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

BASCOMB: Maria Ivanova is an Associate Professor of Global Governance and Director of the Center for Governance and Sustainability at UMass Boston and a member of the Rwanda delegation. Maria, thank you so much for taking the time and for all of your hard work on this issue.

IVANOVA: Thank you.

Related links:

- UN Environment Programme | “Draft Resolution: End Plastic Pollution: Towards An Internationally Legally Binding Instrument”

- UN Environment Programme | “What You Need To Know About The Plastic Pollution Resolution”

- UN Environment Programme | “A Leap Forward For Environmental Action: Speech By Inger Anderson, Executive Director Of UNEP”

- The Standard | “Meet Wong, Artist Behind Plastic Sculpture at UN Office In Nairobi”

- UN Environment Programme | “Fifth Session of the UN Environment Assembly”

[Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited, “Pasi Hariguti” on Rise Up, by Thomas Mapfumo, Real World Records]

Beyond the Headlines

A development driller off the Gulf of Mexico. According to the U.S. Energy Information Agency offshore oil production in the Gulf of Mexico accounts for 15% of total U.S. crude oil production. (Photo: Petty Officer 3rd Class Barry Bena, U.S. Coast Guard, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

DOERING: And I'm Jenni Doering. It's time now for a look beyond the headlines with Peter Dykstra Peters, an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. And he's on the line now from Atlanta, Georgia. Hey Peter, how's it going?

DYKSTRA: It's going well, Jenni and I'm gonna try and confuse our dear listeners here a little bit because there's news out of Washington that the Biden administration's Justice Department told the federal court that they won't appeal a ruling revoking drilling leases in the Gulf of Mexico.

DOERING: So the Biden administration wanted to drill offshore?

DYKSTRA: The Biden administration didn't want to drill offshore, they were compelled to do so because the Trump administration's Interior Department had signed off on a huge lease sale of 1.7 million acres of the seafloor in the Gulf of Mexico. Which as we all know, remember is the home of the Deepwater Horizon disaster a dozen years ago.

DOERING: Yes. And as I recall, this federal court had said "hey, you didn't consider climate change when you actually decided to go forward with these leases". Is that right?

DYKSTRA: That's right. And the Interior Department under Donald Trump said climate schlimette, we're going to go ahead and do the lease sale anyway. The Biden administration has just decided to go in the opposite direction. Until the court acted they were compelled to pursue this lease by the subsequent court order they just found a way to quit as the Justice Department changed hands.

DOERING: So this is a chance for them to live up to that promise of no more federal oil and gas leasing, right, Peter?

DYKSTRA: That's right. But think about one other thing- there's a renewed push for US oil and gas leasing, because the price has gone so crazy and because Russia is a main source of natural gas for many countries around the world, particularly in Western Europe.

DOERING: So I guess we'll have to see how this plays out. Well, Peter, what else do you have for us this week?

DYKSTRA: Here's a really weird bill out of the Commonwealth of Kentucky. This is a bill that passed their Senate's Natural Resources Committee. It would require the divestment of financial companies, banks, and lenders and others that boycott fossil fuels. In other words, if you stay away from fossil fuels, you will have to stay away from doing business in Kentucky. If the bill passes both houses and the Kentucky governor signs it.

DOERING: So let me get this straight. This is a boycott of a boycott?

DYKSTRA: It's a boycott of a boycott. It's a red state coming to the aid of black gold. The bill sponsors in the Kentucky Senate have basically wrapped themselves up in knots trying to make this sound like a morality play. They say that fossil fuel companies in Europe and the US are among the most socially responsible companies on Earth. They've also described financial institutions that won't do business with fossil fuel companies as engaging in discrimination against fossil fuels.

DOERING: Well, we certainly would not want to deprive them of their civil rights to exploit the planet Peter.

DYKSTRA: Those poor, poor multinationals.

DOERING: Hey, what do you have for us from the history vaults this week?

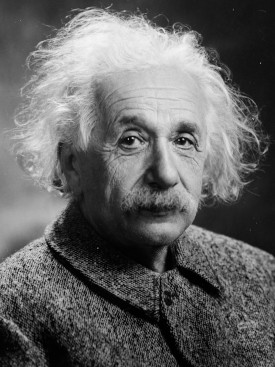

Albert Einstein was born March 14, 1879 in Ulm Germany. (Photo: Orren Jack Turner, Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain)

DYKSTRA: A momentous birthday, March 14, 1879. Albert Einstein is born in Ulm Germany. Of course, his work provided the basis for many of the breakthroughs in physics in the early 20th century. Llate in life after those breakthroughs led to the development of the atomic bomb, Einstein expressed regret for his role in paving the way for nuclear weapons development.

DOERING: Gosh, I wonder what he would think about this shadow of nuclear war that seems to have fallen upon the world again.

DYKSTRA: Well, here's something he said before he died in 1955: “The release of atom power has changed everything except our way of thinking. The solution to this problem lies in the heart of mankind. If I had only known, I should have become a watchmaker”.

DOERING: Well, a very happy birthday to Albert Einstein, and I think he would be what 143?

DYKSTRA: That's right.

DOERING: Well, thank you, Peter. Peter Dykstra is an editor with Environmental Health News. That's EHN.org and DailyClimate.org. Thanks again, Peter, and talk to you next time.

DYKSTRA: Okay, Jenni, thanks a lot, and we'll talk to you next time.

DOERING: And there's more on the stories on the Living on Earth website. That's LOE.org.

Related links:

- The Hill | “Biden Administration Won't Appeal Invalidation of Offshore Oil Leases”

- AP News | “Kentucky Senate Passes Bill Aimed at Energy Boycotts”

- Learn more about Albert Einstein

[Bastian Fiebig Quartet, “Happy Birthday” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mThqsLP3J2I]

BASCOMB: Coming up – A massive coral reef in pristine condition was recently discovered in one of the least explored parts of our planet. That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Support for Living on Earth comes from Sailors for the Sea and Oceana. Helping boaters race clean, sail green and protect the seas they love. More information @sailorsforthesea.org. Support also comes from Friends of Smeagull the Seagull and Smeagull’s Guide to Wildlife. It’s all about the wildlife right next door to you! That’s Smeagull, S - M - E - A - G - U - L - L, SmeagullGuide.org.

[Jeff Krolik Beyond the Sea https://open.spotify.com/artist/30QHFk38S68duJOmqft5ys?si=VqXQECjKTxuIV-aD_6TsQg]

Deep Sea Corals Resilient to Impacts

It is possible that the discovery of these deep-sea corals, which have been largely unaffected by warming oceans, could help in efforts to preserve reefs in more shallow water. (Photo: @alexis.rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO)

DOERING: It’s Living on Earth, I’m Jenni Doering

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Most of us probably think of coral reefs in shallow tropical waters, often easy to see with just a mask and snorkel. But around the world researchers are finding coral reefs in one of the least explored parts of our planet, the deep ocean. Corals can actually be found in water up to 10,000 feet deep, with no access to light. In Tahiti researchers recently discovered one of the largest deep sea coral reefs in the world, spreading for roughly two miles at up to 230 feet deep, in an area known as the twilight zone with very little sunlight. It’s in pristine condition, with no evidence of stress from pollution, ocean acidification, or warming water that has killed roughly half the world’s coral reefs in the last 70 years. Laetitia Hedouin made the discovery as a researcher at the Center for Island Research and Environmental Observatory and she joins me now for more. Laetitia, welcome to Living on Earth!

HEDOUIN: Thank you.

BASCOMB: So how did you first find these deep coral reefs near Tahiti?

The deep sea corals discovered in Tahiti are called “rose” corals for their intricate formations. (Photo: @alexis.rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO)

HEDOUIN: Well, the first time I heard about it, it was from some diving club. The people were diving there, and they mentioned, "Oh, Laetitia, you should go," like, "the spot looks amazing but we need to have your point of view as coral biologist." And when I arrived at this spot at 40 meter, it was like, Oh, my God, it's incredible! The corals were just gigantic, like they were everywhere, and they were this rose shape that is like, very beautiful. And it's common at depth, but like, not that much and not that size. So I was very impressed. So when we came back at the surface, I was like, oh, but we really need to do a scientific study. There is really something different about that spot, about that area. And I had, like, so many questions that I was like, Okay, we need to do something.

BASCOMB: So how big is the area and what is the depth you were diving in?

The enormous size of the corals indicates that they are at least two decades old, researchers report. (Photo: @alexis.rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO)

HEDOUIN: So I think one of the things very interesting about that reef, is that like there is one species that live from 30 to 40 meter that is called Porites rus. And it's a species that we used to know from the lagoon side, and they form branching colonies, and you can find them everywhere in the bay, in the lagoon and stuff like that. And when you go on the site, like at 30 meter, this coral looks like a plate, like and they form like the different plates arranged together to form this big roses shape that we call the rose coral. So it's very impressive in terms of biology to realize that you have this coral, the same species that could change its morphology with the depth and because the light is becoming limiting at depth, so they kind of change their shape to really be able to capture the few light that is arriving at that depth. So one thing that was very impressive for me. Something more in terms of biology is that at some point, when you go deeper, at 45 meter, 50 meter, you can find one rose that is made of two different species. One is Porites rus, and one is Pachyseris. So the two species kind of correlate together to form this big rose shaped colony that you can see. So it's very interesting, and I was really fascinated by discovering this coral and this landscape.

The corals are located in what is known as the twilight zone, an area of the ocean with very little sunlight. (Photo: @alexis.rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO)

BASCOMB: Of course, we know that worldwide, coral reefs are in serious decline from rising ocean temperatures and coral bleaching. Roughly half have actually died since the 1950s. And the future doesn't look good. But from what I understand this deep coral in Tahiti is actually quite healthy and in really good condition. To what degree do you think the depth is protecting it from climate change and warming water?

HEDOUIN: Yeah, that was one of the information that for me was very important is like, the size of the colony was very big, somewhere like two meter diameter. And we know that coral, when they live deeper, they'll grow smaller. So when you have that size of coral, they are approximately 20 years old, at least. So this means that we have been going for the last two decades without any insert from thermal stress, global warming, it didn't affect that. I believe that the main reason is like the light because like the bleaching is really a reaction to what we call oxidative stress. And that oxidative stress is due to the high temperature that is combined to a high light intensity, that generate like that oxidative stress. So if you reduce one part of the stress, that will be the high light, then they will be able to kind of face the heat stress that they will have. So because in the deep, they will just have the heat stress and normally, they can bleach but they can recover. And I believe that's the reason why today we don't find any sign of mortality on that reef. So the depth is kind of protecting them from like the bleaching event. And potentially it will not protect them forever, because it really, really depends of the intensity and the frequency of the future heat stress that will occur on Earth. But until now in French Polynesia it's really like a trend that we observe, that the deeper reefs have been protected from climate change.

While about half of the Earth’s coral reefs have died in the last 70 years, the corals discovered in Tahiti are thriving—a phenomenon that is intriguing scientists. (Photo: @alexis.rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO)

BASCOMB: What are some of the potential impacts of this discovery? I mean, how possible is it that deep sea corals like this can be helpful with coral restoration in more shallow water?

HEDOUIN: So, one of the theory and hypothesis is the reason that deeper corals is that because like they share like similar species as the shallow reefs and we have been watching spawning on the deeper reef for this species of Porites rus, so if they are spawning, you can have baby corals from like the deeper reef that will come and that will settle in the shallow reef that are really impacted or degraded. So they could be like a natural source of new baby coral that will help the resilience of the coral on the surface that has been degraded. So that's the first point. And also I think there is like a way to see also this part of the reef that we need to study because potentially they could serve our nursery for like some fish or some other organism that are key also for like the shallow water reef. Also what we think is that we put into the light this coral, this area of Tahiti, but we think that if we do more dive in Tahiti, we have the potential to discover more area like that. I think we just don't have at that time the knowledge of how diverse these deeper reef are and how abundant they are, and I think there is really a need to better identify where they are because they could be key target to help the resilience of other coral reefs.

Alexis Rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO, took these stunning underwater photographs. (Photo: @alexis.rosenfeld, supported by UNESCO)

BASCOMB: Laetitia Hedouin is a researcher at the Center for Island Research and Environmental Observatory in French Polynesia. Laetitia, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

HEDOUIN: Thank you, goodbye.

Related links:

- UNESCO | “Rare Coral Reef Discovered Near Tahiti by a UNESCO Mission”

- UNESCO | “Rare Coral Reef Discovered Near Tahiti by A UNESCO Mission (Video)”

- United Nations | “Rare Coral Reef Discovered Near Tahiti Is ‘Like A Work of Art,’ Says Diver”

- EcoWatch | “New Reef Discovered in Deep Waters off Tahiti is a Rare ‘Positive Story’ for Corals”

[Glen Velez, “Ramana,” from Seven Heaven, CMP Records. Start at :10 or wherever in that neighborhood it sounds right to you. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpZbzziMt7o]

Redwoods Returned to Tribes

Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ is a 523-acre property, now owned by the InterTribal Sinkyone. (Photo: Max Forster (@maxforsterphotography), courtesy of Save the Redwoods League)

DOERING: For thousands of years the Sinkyone people of northern California thrived among ancient coast redwoods, the tallest trees in the world. But the arrival of European settlers and logging brought genocide to the people and the trees they considered family, severing them from their sacred lands. Now, as part of a landback movement across North America, the Indigenous people of coastal northern California are restoring that relationship. A consortium of ten tribal nations called the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council are now the guardians of a 523-acre property called Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ that contains 200 acres of old-growth coast redwoods. The nonprofit Save the Redwoods League was able to purchase the property with $3.5 million in conservation funding from Pacific Gas and Electric and has transferred ownership of the forest to the Sinkyone Council for permanent protection. Buffie Schmidt is a Northern Pomo Language Teacher and Treasurer of the Intertribal Sinkyone Wilderness Council and joins me now to discuss. Welcome to Living on Earth!

SCHMIDT: Thank you, Jenni.

DOERING: So first Could you tell us who you are? And do you have a Pomo name in addition to Buffie Schmidt that you would like to share?

Fungus growing on a log in Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ. (Photo: Max Forster (@maxforsterphotography), courtesy of Save the Redwoods League)

SCHMIDT: It would be my honor to introduce myself and my northern Pomo language. [Tsin t̪a ma naʔ Maːt̪a Mit̪a' ʔa: na. Shibal dano pʰoʔo maʔ, Noyo naː Ukia kʰe ʔa: na. Amiˈe Thomas Campell Sr. Shibal dano pʰoʔo maʔ naː Noyo kʰe moːw na. Amiˈtʰe Christine Hamilton. Ukia kʰe maːn na.]. My name is Buffie Schmidt. I come from Sherwood Valley Noyo and Rancheria. My father Thomas Campbell comes from Sherwood Valley and Noyo reservation. And my mother Christine Hamilton comes from Rancheria. I'm proud to say that I am a traditional Pomo basket weaver I was taught by my mother, Christine Hamilton. And she was taught by Elsie Allen and Elsie Allen and was taught by her mother, and so on and so forth. These teachings shared culture have been passed down from generation to generation, just like our language not learned in schools or textbooks, but by oral physical hands on teachings.

DOERING: So could you tell me about the name of this place? We're talking about today? Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ. So what is the meaning of that phrase?

SCHMIDT: Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ means fish run place. And it's Sinkyone. It's a indigenous language of the area. And there are coho salmon that are running in the streams in the wild there.

DOERING: And so where along the California coast, are these 523 acres called Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ and what is it like to spend time there?

Red elderberry in Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ. (Photo: Paul Robert Wolf Wilson, courtesy of Save the Redwoods League)

SHMIDT: The property, the 523 acres that was donated back to the Sinkyone member tribes is located in Northern California, specifically in the Mendocino County area. Sometimes people have referred to it as the last coast. It's wild. It's the way the Creator YaKaPede intended it to be: a beautiful, natural place where redwoods can thrive. And because of our land back acquisition, all ecosystems can feel safe that they will prosper and live out their lives without having to worry about overdevelopment, logging.

DOERING: Right, because there was a long history of logging in this area, I understand. And there is still some old growth there of the coast redwoods. Could you tell me a bit about that backstory of what's happened to the land and to the people on the land going back centuries?

SCHMIDT: Surprising to me and the member tribes, some people don't know the history of the area, don't realize that they're standing on indigenous First Nation people grounds. We come from a long time of atrocities bestowed on the native people in this area and our relatives [Katˈil xale], our redwoods have been there for hundreds of years, there are many old growth redwoods in that area. And they're still in danger of being logged by timber companies. And the reservation that I spoke of that I come from Noyo reservation is in the city of Fort Bragg. And my people 100 years ago, lived on the beach there in the Noyo Harbor. And when the milling company came in, they moved our people up to the cliff, because they were going to use that harbor as logging to move ships, boats logging in and out in and out. And so my people were in the way there. So they moved us up above the coasts there. We still have that land.

DOERING: Could you describe looking back to the time of these ancestors? What kind of relationship would they have had with the fish, the coho salmon, you mentioned with other species and with the trees themselves of this region.

Western swordfern at the base of a coast redwood tree in Tc’ih-Léh-Dûñ. (Photo: Max Forster (@maxforsterphotography), courtesy of Save the Redwoods League)

SCHMIDT: My ancestors as well as Sinkyone Board have a reciprocal relationship with the land that the Creator YaKaPede has provided for us. We take what we need and not any more. We try to tend to land so that it'll grow better the next season, and that will always be there. And there's a balance. There's a cycle there. That's how our ancestors lived. And that's what our people today are trying to get back to. There was a disconnect during the Gold Rush movement. When settlers first came in first contact. It was shameful to be an indigenous person to be [hilthin]. So that generation was trying to assimilate to the the new world and lost a lot of their traditions, their gathering spots, their hunting and their fishing grounds and their way of life. And the next generation, again, assimilation and colonization, lost even more. So my generation and the generation next to me are trying to catch up to that. We're trying to remember and to learn our cultural ways to be like our ancestors were, to honor the lands, the sky, the water.

DOERING: How do you think the land back movement can help indigenous people reconnect with their traditional values? And how does it help provide some healing and reconciliation after the cultural genocide that's taking place here in North America?

SCHMIDT: To have land acknowledgement and land physically back means that we are being seen as a native people, not just that we are people that were part of a genocide in discovering these Americas. People can see that we're still here. It brings awareness to our tribes and our cultures and stops the erasure of our cultural traditions and stops genocide.

DOERING: Buffie Schmidt is a northern Pomo language teacher and is treasurer of the intertribal Sinkyone wilderness Council. Thank you so much, Buffie.

SCHMIDT: Thank you, Jenni. I appreciate this opportunity to speak on behalf of the Sinkyone board. Our sacred ceremonies and our prayers were done on these places that we hold so dear. And now we can feel triumphant to receive land back not only in our hearts, but on paper too. [YahWi! K’edi wadim! ] Thank you walk well.

Related link:

The New York Times | “Redwood Forest in California Is Returned to Native Tribes”

[Extreme Pomo by Dave Smith And The ----- daNCERS https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZldBMTCMhwA]

DOERING: And by the way this is a Pomo song led by tribal elder and dance captain David Smith.

The Impala Imperative

Two impala face each other in tall grass. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

DOERING: Prey animals have evolved many ways to confuse their predators, from a zebra’s stripes to an impala’s back side. Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence, Mark Seth Lender explains.

The Impala Imperative

© 2022 Mark Seth Lender

All Rights Reserved

They are magnificent. Common they may be but it is impossible not to feel overawed watching them now on a slope of the rounded hill where they stand in high relief, five in number, their name an onomatopoeia:

Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!! Immm-PaLa!!

You can see them, in that name, bounding across the veldt in sure-footed certainty and grace. In their grass-colored coats even as they graze walking slow their muscles, tight and masculine beneath the skin imply –

Immm-PaLa!!

Impala standing near each other create a camouflage effect. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

The females were in that very same place not an hour before. All in a herd of their own. Not like the males who are only near the crest but right on top. Rather to be seen. Than take a chance on hiding low on one side or the other and miss an otherwise apparent danger. With a clear view they see very well. Their legs are very long. No doubt they feel they can outrun anything that comes after them. In aspect, except for a subtle difference in proportion and a hidden capacity for speed, they could be white-tailed deer.

You would never make that mistake with the males. They are what they are. Their horns are nearly half the length of them and ribbed and strong, they curve and curl like an ancient casting made of bronze, the maker and his art lost in history. They stand tall when they stand, their eyes bright as windows; they call to each other mouths open wide.

Unassailable.

As if they have a talisman.

As if they have a secret.

And they do:

The dark black markings on their buttocks are shaped to the same color and curve as those brazen horns. But upside down! When they bow, to nibble grass, head turning one side to the other to graze, from the perspective of some predator lying in wait, lying low, those horns and these hindmost markings cross.

A herd of impala walk the savanna. (Photo: © Mark Seth Lender)

Confusion!

All the more so when two or three impala are together. Horns high horns low horns crossed and crossing and turning.

“Impa – La? Impa – Low? Impa – LUNGE? No… I don’t think so.”

Early morning and just barely light there they are again, all five, ambling at leisure, chewing the grasses wet with mist close along the trees, in all their confidence and strength. Or is it acceptance? No magic is perfect.

DOERING: That’s Living on Earth’s Explorer in Residence Mark Seth Lender.

Related links:

- Read Mark's field note for this essay

- Thanks to Donald Young Safaris

- Mark Seth Lender’s website

[Peter Bence, “Africa” on The Awesome Piano, by David Paich and Jeff Porcaro, Steinway & Sons Musichttps://video.search.yahoo.com/search/video;_ylt=AwrEwhHOC69gc08AsElXNyoA;_ylu=Y29sbwNiZj EEcG9zAzEEdnRpZAMEc2VjA3Nj?p=peter+bence+africa+youtube&fr=mcafee#id=8&vid=f02afef559 861a5673706a6fcb906be6&action=view]

BASCOMB: Coming up – Red states, blue states and the state of science education in the US

That’s just ahead on Living on Earth.

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and United Technologies, combining passion for science with engineering to create solutions designed for sustainability in aerospace, building industries, and food refrigeration.

[King Sunny Ade, “Samba E Falaba Lewe” on JuJu Music, originally on Island Records (Now on Mango) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q8MkBkYh-JE]

Miseducation: How Climate Change is Taught in America

In the United States education is primarily a state and local responsibility: curricula and the requirements for enrollment are developed by communities as well as private organizations. (Photo: Nenaj Stojkovic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. The science of climate change has been highly politicized in the United States. And that political fight extends even into our classrooms. In her book Miseducation: How Climate Change is Taught in America, journalist Katie Worth explores the access fossil fuel interests have to American children and the red state blue state divide on climate science education.

Katie Worth, welcome back to Living on Earth!

WORTH: Thanks so much. I'm really glad to be here.

BASCOMB: So what inspired you to write this book about miseducation and climate change in American schools?

WORTH: Well, years ago, I was on this show and talking to you about my trip to the Marshall Islands, where I was, at the time a reporter of PBS Series Frontline. And a colleague and I were assigned a story about climate change in the Marshall Islands. And for those who don't know, it's a Pacific Island nation and it's extremely vulnerable to climate change because its highest point is something like 12 feet above sea level on these islands. And so the entire nation, you know, you can imagine just a foot or two of sea level rise could be a big problem in an island that low and so the entire nation could kind of be existentially threatened by climate change. And so we were there, and we were talking to kids and we were really struck by how fluently they could talk about climate change. Its cause, what it might mean for their lives. And one of the kids Izermen, he was nine years old, he had first learned about climate change at age six, and he'd learned about it in school every year since then. And his family was considering moving to Oklahoma, where they had some extended family. And so, you know, the question arose- okay, well if Izerman moves to Oklahoma, what will he and his siblings learn about climate change there. So that was one of the origin stories of this book. I also, right around that time, I was doing some reporting on climate denialism. And I went to a conference hosted by the climate denial organization, Heartland Institute. And they told me while I was there, that they were starting to send out packets to every science teacher in the nation, they claimed to send out more than 200,000 of these packets. That included a book called Why Scientists Disagree About Climate Change. Which we know they don't. And a DVD about solar cycles and how the recent warming can be explained by solar cycles, which, you know, scientists say that it can't. So the kind of confluence of those two events made me realize, oh, there's some really rich reporting territory here and this is worth digging into.

BASCOMB: You have in the front of your book, this US map that shows me just open the page here. It shows a map of the United States and it has Republican controlled legislative states and Democratic states. And overlaid with that is a grade for each of the states and how they're teaching climate science. Can you tell us about that map and what it shows?

According to the World Bank, sea level rise is projected to endanger 40 percent of existing buildings in Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands. (Photo: Keith Polia, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

W0RTH: Yeah, sure. Um, so an organization called the National Center for Science Education teamed up with another organization called Texas Freedom Network, and they hired a panel of educators to look at each state's academic standards, science standards, and how they treat climate change. So I just said a lot of words there, so academic standards are just a state's expectations of what a kid's going to learn any given, you know, year, basically, or subject. And they sound really mundane and arcane and they are, but they're actually really powerful, because teachers absolutely look to them to decide what they're gonna teach in a year. And we don't have a national curriculum so it comes down to what the states say. And so this panel looked at each state's science standards and how they treated climate change on the basis of four different criteria: whether a kid would learn that climate change is happening, that it's caused by humans a little bit about what the effects might be, and then that a little bit about what the solutions might be, that there's some hope. And then rated them and then those ratings were turned into letter grades. So what I did was then I mapped it onto this red, blue, purple map of the states based on who controls the state legislatures. And then what we saw is kind of what you would expect. There was no blue state that got worse than a B+. And there were red states that did great. Actually, there were, you know, I think Wyoming gotten A, Alaska got an A or A-. So there were a handful of red states that actually do this very well. But the majority of the red states did considerably worse. There were many states that got C's, D's and F's on this question. And so what that means is you can kind of roughly guess what a kid might learn about climate change in their education by knowing what political party runs their state legislature. Not based on what the science says. And you know, that's problematic because of course, the climate crisis doesn't stop to check who's running the state legislature before striking a community you know, it's like equal opportunity. No matter where you live it's gonna affect your life. And kids in every state have a lot at stake in this question.

BASCOMB: So what do we have in the way of national standards for how to teach climate change? And how is that actually interpreted by the states?

WORTH: There is actually no national standards. But there was a group of educators from all over the country that came together and tried to create kind of a model set of standards that they thought was better than what most of us had growing up and kind of using the latest kind of pedagogy, how kids actually learn science. And they created what's called the Next Generation Science Standards. But it's not like a federal effort that is then being laid down on the states, every state has to approve it. To the contrary, the people who wrote the standards who were from all 50 states then went back to their states and asked the legislatures to adopt these next generation standards. And some of them did, and some of them really rejected it. And some of them amended it. So like Oklahoma, for example, adopted Next Generation Standards, mostly, but then they erased all the standards that had anything to do with climate change in 2014. So like, they didn't even propose it to their legislatures. They also, as it happens, erased the word evolution from the standards, and they instead swapped it out with the words like kind of euphemisms like development or change over time, because the E word, evolution is still kind of, it's kind of a hot button topic in Oklahoma. And so there's a lot of states that kind of did that tweaking that watered down the standards. And then there's states that just absolutely rejected the next generation standards and stuck with their own processes. Texas is one of them who has really adamantly stuck with its own standards. And that's a problem because Texas is one of the largest purchasers of textbooks in the nation, right? So textbook publishers pay attention to what Texas is approving. And then that then becomes the next generation of textbooks that is then sold to districts around the country. So it's like, these things do tend to have, you know, what happens in Texas does have a national effect. And so it does wind up affecting kids and even in blue states, sometimes what is happening in red states.

In #Miseducation, investigative journalist Katie Worth reveals big inequities in #climate education and a gap that mirrors state politics. @Revelator_News https://t.co/xY5mnRn2ct

— Daily Climate (@TheDailyClimate) November 17, 2021

BASCOMB: Well, let's talk a bit more about the fossil fuel industry. You write here in your book that they actually have a long history of taking their message directly to schools. Can you tell us more about that?

WORTH: So the fossil fuel industry has really greened, their image, worked to, you know, they no longer publicly deny climate change, they say that they care about it. There's all of these, you know, ads that you can see from Chevron from Exxon saying that they're working on the climate issue, that we all need to work on the climate issue. But I was sitting in a classroom in Arkansas, reporting on what was being taught there. A representative of the Arkansas State oil and gas industry association, and she was there with a PowerPoint presentation for the seventh graders. And she, it's her whole job to go classroom to classroom and give this PowerPoint presentation. And, you know, it included some good information about the geology of Arkansas, where you can find oil and where you can find gas and the technology used to extract it stuff that we should know that students should learn. But then there was a whole section about climate change effectively. And she said that, you know, basically told students that it wasn't something that they needed to worry about. You know, China and India were the ones causing it. And even if you shut down every fossil fuel emitted by the United States tomorrow, you would just have a 0.0001% impact on the climate, which is blatantly false. You know, and she's like, and windmills kill birds, so every source of fuel has a problem. You know, equating windmills killing birds with this crisis that will change all of the planet. So it's just like, it was very much the talking points of the industry, and it was directly being fed to seventh graders. And the teacher was deferential to her and so were the seventh graders. They didn't ask any critical questions.

BASCOMB: So to what degree are you seeing this climate denial being taught in schools actually taking effect and children, you know, pushing back on the science of climate change?

WORTH: I grew up in a town that's only about 15 miles away from Paradise, California. And you might remember that that's the town that burned to the ground in 2018, due to a mega fire.

BASCOMB: Yeah.

WORTH: And the fire was sparked by, you know, poorly maintained utility lines, but it was really fed by climate change. The five hottest summers all had occurred in the last five years before the fire and it had rained less than a fifth of an inch in the last six months. So it was just bone dry. And then you know, the fire caught, the winds blew it very swiftly and it burned down 90% of the buildings in Paradise. So I went back there a few months later, and attended a seventh grade science class at Paradise Intermediate School. And the school had been displaced from Paradise into a shuttered hardware store and in Chico. So it was basically like a Lowe's like they were setting up a school in a Lowe's and all the students, the classes were in the aisles and students were getting lunch off of the checkout counters and playing freeze tag in the lumber center. You know, it was just very, very weird and surreal.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental education as “a process that allows individuals to explore environmental issues, engage in problem-solving, and take action to improve the environment.” (Photo: Nenaj Stojkovic, Flickr, CC BY 2.0)

BASCOMB: Oh gosh.

WORTH: And so this teacher, he teaches climate science every single year and this year he was teaching it to children who were arguably climate refugees, right? So I watched, I was there for a couple of weeks and watched him teach it and at one point one of the kids raised his hand and said- "Hey, I'm really confused because my parents say this isn't real. Like, there's no such thing as climate change. And, you know, I don't know who to believe". And I thought that the teacher Mr. Kessler handled it really thoughtfully. He said, you know, it can be really confusing when you get different information from different people in your life. But I'm not here to tell you what to think. I'm here to just provide you with the very best evidence that I can. And that's what science is, is looking at evidence and making an analysis and discovering what is happening and you get to do that you get to make your own analysis, you get to look at this NASA Data, and NOAA data and think about what is happening. And I thought that was really like a beautiful way to sidestep the, you know, like what your parents are wrong, which they are but empower the student to think for himself, which he may not in that moment. Iif the most important people in his life believe something, he's likely to believe it too. But, you know, the more messages he gets like that, as when he becomes a decision making adult, he may have a different perspective. And in fact, a couple days later, Mr. Kessler gave the class a writing prompt: Do you think that climate change has affected your life? And do you think it will affect your life in the next 50 years? And the little boy said, I don't think climate change has affected my life at all yet. And I don't know if it will affect my life in 50 years, because I don't know if I believe it yet.

BASCOMB: Gosh, what does it take? I mean, home, you know, literally burned down and, you know, learning in a school in the aisle of a hardware store. Well, what can parents do, if you're concerned maybe about how your children are being taught climate science in school?

WORTH: So I mean, I think just paying attention to what's happening in your kids' school is important. And it's hard to imagine a top down kind of federal effort working, because it hasn't been a good record of the federal government getting involved in state education. But you know, these fights over what exactly is going on. Paying attention to what's going on in your state standards. The Texas state standards, you know, the fossil fuel industry was at every one of these meetings, and sometimes they were the only ones, or not necessarily the only ones but there wasn't a big counterweight of teachers and parents saying- “No, this is an important issue, we want our kids to know what the solutions may be. And they need to know that that's important”. And so you know, had there been kind of a bigger voice in that direction. Maybe it would have played out differently.

BASCOMB: Katie Worth is a journalist and author of Miseducation: How climate change is taught in America. Katie, thank you so much for taking this time with me today.

WORTH: I'm really glad to be here. Thanks for having me.

Related links:

- Find the book Miseducation here (Affiliate link helps donate to LOE and local indie bookstores)

- Miseducation is published by Columbia Global Reports

- Learn more about the National Center for Science Education

- Connect with Katie Worth via Twitter

- Learn more about Katie Worth

- Watch a live interview from the Paleontological Research Institution with Katie Worth

- EPA | “Climate Change Resources for Educators and Students”

[Eric Tingstad, “South To Carolina” on Electric Spirit, by Eric Tingstad, Cheshire Records From the top.]

BASCOMB: Living on Earth is produced by the World Media Foundation. Our crew includes Naomi Arenberg, Paloma Beltran, Chloe Chen, Iris Chen, Josh Croom, Gabriella Diplan, Mark Kausch, Mark Seth Lender, Don Lyman, Louis Mallison, Aynsley O’Neill, Sophia Pandelidis, Jake Rego, Teresa Shi, and Jolanda Omari.

DOERING: Tom Tiger engineered our show. Alison Lirish Dean composed our themes. Special thanks this week to Destination Wildlife.

*Correction* Special thanks this week to Newland Tarlton Safaris

You can hear us anytime at L-O-E dot org, Apple Podcasts and Google Podcasts, and like us, please, on our Facebook page - Living on Earth. We tweet from @livingonearth. And find us on Instagram at livingonearthradio.

Steve Curwood is our Executive Producer. I’m Jenni Doering.

BASCOMB: And I’m Bobby Bascomb. Thanks for listening!

ANNOUNCER: Funding for Living on Earth comes from you, our listeners, and from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, in association with its School for the Environment, developing the next generation of environmental leaders. And from the Grantham Foundation for the protection of the environment, supporting strategic communications and collaboration in solving the world’s most pressing environmental problems.

ANNOUNCER 2: PRX.

Living on Earth wants to hear from you!

Living on Earth

62 Calef Highway, Suite 212

Lee, NH 03861

Telephone: 617-287-4121

E-mail: comments@loe.org

Newsletter [Click here]

Donate to Living on Earth!

Living on Earth is an independent media program and relies entirely on contributions from listeners and institutions supporting public service. Please donate now to preserve an independent environmental voice.

NewsletterLiving on Earth offers a weekly delivery of the show's rundown to your mailbox. Sign up for our newsletter today!

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

Sailors For The Sea: Be the change you want to sea.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

The Grantham Foundation for the Protection of the Environment: Committed to protecting and improving the health of the global environment.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Contribute to Living on Earth and receive, as our gift to you, an archival print of one of Mark Seth Lender's extraordinary wildlife photographs. Follow the link to see Mark's current collection of photographs.

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth

Buy a signed copy of Mark Seth Lender's book Smeagull the Seagull & support Living on Earth